Abstract

Background

Combining the antibiotic azithromycin and hydroxychloroquine induces airway immunomodulatory effects, with the latter also having in vitro antiviral properties. This may improve outcomes in patients hospitalised for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Methods

Placebo-controlled double-blind randomised multicentre trial. Patients aged ≥18 years, admitted to hospital for ≤48 h (not intensive care) with a positive severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) reverse transcription PCR test were recruited. The intervention was 500 mg daily azithromycin for 3 days followed by 250 mg daily azithromycin for 12 days combined with 200 mg twice-daily hydroxychloroquine for all 15 days. The control group received placebo/placebo. The primary outcome was days alive and discharged from hospital within 14 days (DAOH14).

Results

After randomisation of 117 patients, at the first planned interim analysis, the data and safety monitoring board recommended stopping enrolment due to futility, based on pre-specified criteria. Consequently, the trial was terminated on 1 February 2021. 61 patients received the combined intervention and 56 patients received placebo. In the intervention group, patients had a median (interquartile range) 9.0 (3–11) DAOH14 versus 9.0 (7–10) DAOH14 in the placebo group (p=0.90). The primary safety outcome, death from all causes on day 30, occurred for one patient in the intervention group versus two patients receiving placebo (p=0.52), and readmittance or death within 30 days occurred for nine patients in the intervention group versus six patients receiving placebo (p=0.57).

Conclusions

The combination of azithromycin and hydroxychloroquine did not improve survival or length of hospitalisation in patients with COVID-19.

Short abstract

There are no beneficial or harmful effects from the combined intervention of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin for hospitalised patients with confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) https://bit.ly/3c0s6XG

Introduction

Early in the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, some evidence, mainly from laboratory studies, suggested that chloroquine and its less toxic derivative hydroxychloroquine, often used as an antirheumatic drug, had an antiviral effect on coronaviridae by inhibiting several pH-dependent steps in replication and endosomal viral uptake into human cells [1]. These findings have been confirmed in laboratory studies of primate cells infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS)-1 [2]. In addition, hydroxychloroquine may bind to host cell sialic acids and gangliosides with high affinity, thus protecting the cell against binding to SARS-coronavirus (CoV)-2 via its spike protein [3]. Administered at recommended doses, in most countries up to 400–500 mg daily, hydroxychloroquine seems to be safe, even when used for longer periods, and costs are low [4].

Azithromycin is a macrolide antibiotic, which has proven effective in reducing airway inflammation and consequent hospitalisation-requiring exacerbations of COPD, asthma and bronchiectasis [5–7]. Recently, a strong association was found in critically ill patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome between treatment with azithromycin and improved survival [8], as summarised with greater power in systematic meta-analyses [9, 10]. Furthermore, hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin may act synergistically to prevent the coronavirus from binding to ganglioside receptors on human cells [11].

Important trials show positive outcomes for agents such as remdesivir, anti-interleukin-6 and convalescent plasma in milder cases and early disease stages [12–14], but these interventions seem to be less effective in severely ill patients [15]. Conversely, in more severe cases, immunosuppressive pharmaceuticals such as corticosteroids do show some effect [16]. Thus, there appears to be a window of opportunity for antiviral treatment in the early and less-severe disease stages [17].

The present trial assessed whether a combination of azithromycin and hydroxychloroquine, both in moderate and approved (for rheumatic indications) dosing regimens, would increase the number of days alive and discharged from hospital among hospitalised patients with COVID-19.

Methods

The trial protocol and statistical analysis plan are available in the supplementary material (appendices 1 and 2) and have been published previously [18, 19]. The study was approved by the ethics committees of all participating sites (H-20022574), the Danish Medicines Agency (EudraCT no 2020-001198-55) and the Danish Data Protection Agency. It was monitored in accordance with good clinical practice (GCP) by the GCP units of the participating regions in Denmark. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki [20]. No financial incentive was provided to the investigators or participants. There was an independent data and safety monitoring board (DSMB), consisting of three clinicians and researchers who are experts in performing large randomised studies. Additionally, the DSMB had access to the trial statistician, Tobias Wirenfeldt Klausen, a highly skilled biostatistician, who also supervised the interim analyses. Tobias Wirenfeldt Klausen was available any time the DSMB wanted his input. He was blinded to treatment allocation, as only the trial pharmacist had the key to unblind.

This DSMB reviewed the trial's progress and performed safety, efficacy and data completeness evaluations during the trial. It was not possible (in the interest of timeliness) to involve patients or the public in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination of our research. This study is a primary analysis and is described in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting of Randomised Trials guidelines.

Study design and sites

The Proactive Protection with Azithromycin and hydroxyChloroquine in hospitalised patients with COVID-19 (ProPAC-COVID) study was a multicentre, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, randomised clinical trial investigating whether adding 15-day treatment with azithromycin and hydroxychloroquine to standard of care could decrease the period of hospitalisation and reduce the risks of noninvasive ventilation (NIV), admittance to an intensive care unit (ICU) and death. Patients were enrolled between 6 April 2020 and 21 December 2020 at six hospitals in Denmark within the COPD Trial Initiative (COP:TRIN) collaboration (www.coptrin.dk). The dosages selected were based on well-tolerated doses used to treat other diseases (e.g. rheumatological diseases), while lowering risk of cardiac side-effects. The durations were selected to ensure coverage of patients with prolonged admissions for a relatively large part of the admissions and to securely cover the entire observation period of the primary outcome. In addition, durations were chosen to protect against secondary infections from Gram-positive micro-organisms.

Participants

Eligible patients had to be 1) ≥18 years of age; 2) admitted to hospital with a confirmed positive reverse transcription (RT)-PCR test for SARS-CoV-2 infection; and 3) hospitalised for ≤48 h. Each patient provided signed informed consent to participate. Patients were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: 1) received >5 L oxygen supply; 2) known intolerance/allergy to the study drugs; 3) neurogenic hearing loss; 4) psoriasis; 5) retinopathy; 6) maculopathy; 7) visual field changes; 8) were breastfeeding/pregnant; 9) severe liver disease (international normalised ratio >1.5 spontaneously); 10) severe gastrointestinal disease (investigator-assessed liver disease, severe ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease, peptic ulcer disease or cancer); 11) neurological or haematological disorder; 12) estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <45 mL·min −1·1.73 m−2; 13) clinically significant cardiac conduction disorder/arrhythmia or a prolonged corrected QT interval (QTcF) (i.e. >480 ms for males or >470 ms for females); 14) myasthenia gravis; 15) receiving treatment with digoxin; 16) glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency; 17) porphyria; 18) hypoglycaemia (blood glucose <3.0 mmol·L–1); 19) unable to give informed consent; 20) severe linguistic problems that significantly hindered cooperation; or 21) were receiving treatment with ergot alkaloids. The investigators evaluated patient eligibility based on these criteria.

Randomisation and masking

The study pharmacist generated the randomisation sequence, which was then entered into the online platform REDCap electronic data-capture tools hosted by the participating Danish regions. Patients were randomised 1:1 to azithromycin plus hydroxychloroquine or matching placebo capsules. Randomisation was performed in blocks of unknown and varying size, and the final allocation was blinded and stratified for age (>70 years versus ≤70 years), site of recruitment and whether the patient had any of the following chronic lung diseases (yes versus no): COPD, asthma, bronchiectasis or interstitial lung disease. All patients and study staff were blinded to participant treatment assignments. This included outcome assessors, investigators and study nurses, as well as research and clinical staff. The DSMB remained blinded throughout and made all recommendations blinded to treatment allocations. Only the trial's chief pharmacist held the key for unblinding. Formal unblinding took place on 1 February 2021 after the DSMB recommendation had been received and acknowledged.

Intervention

Patients were randomised to one of two treatment arms: 1) 500 mg azithromycin once daily plus 200 mg hydroxychloroquine twice daily on days 1–3 and then 250 mg azithromycin once daily plus 200 mg hydroxychloroquine twice daily on days 4–15; 2) placebo instead of both types of intervention medication. Medication (both arms) was marked with neutral labels, e.g. “azithromycin group A” and “azithromycin group B”. An important safety consideration for both study drugs was QTc prolongation [21, 22]. Therefore, trial personnel measured the QTc at least twice during the period of hospitalisation.

Primary and secondary end-points

The primary end-point was the number of days alive and out of hospital (DAOH) within 14 days from randomisation. This outcome measure was developed by trialists to be both sensitive and clinically relevant, and it provides a method for counting days with sustained recovery without lead-time bias [23–25]. For the first secondary end-point, each patient was placed in one of the following eight categories on day 5 and day 15, as described in our previous research [12]: 1) discharged from hospital with no restrictions on activities; 2) discharged from hospital, but with restrictions on activities (may/may not be receiving long-term oxygen therapy at home); 3) hospitalised and under observation, but not receiving supplemental oxygen or any other treatment; 4) hospitalised and not receiving supplemental oxygen, but receiving other treatment (which may/may not be related to COVID-19); 5) hospitalised and receiving supplemental oxygen by a method other than those described in 2) or 3), such as from a nasal catheter; 6) hospitalised and receiving NIV or oxygen from a high-flow device; 7) hospitalised and receiving mechanical ventilation or extra corporeal membrane oxygenation; or 8) dead. The trial included eight other secondary outcomes: 1) number of days in an ICU (time frame 14 days); 2) number of days NIV was required during hospitalisation (time frame 14 days); 3) mortality rates (time frames 30, 90 and 365 days); 4) length of hospitalisation (time frame 14 days); 5) DAOH (time frame 30 days); 6) time to readmission for any reason (time frame 30 days); 7) change in patient's pH, arterial oxygen or carbon dioxide tension measurements (time frame 4 days); and 8) time until no supplementary oxygen was required or until the patient was given “long-term oxygen therapy” (time frame 14 days). Outcomes with follow-up >30 days will be reported later. All outcomes and analyses were conducted in strict concordance with the statistical analysis plan.

Sample size calculation

The sample size for the primary outcome (DAOH14) was calculated assuming a two-sided significance level of 5% and power (1 – β) of 80%. A group-sequential study design with one planned interim analysis at half-target recruitment was used. The standard deviation was set at 4 days [23] and the detection limit was set at 1.5 days (both directions). StudySize software (version 3.0; CreoStat HB, Gothenburg, Sweden) was used to calculate the sample size of 226 participants.

Statistical analysis

We compared outcomes using t-tests or Mann–Whitney U-tests for continuous variables (depending on distribution), Chi-squared tests or Fisher's exact test for nominal variables, and log-rank tests to compare Kaplan–Meier survival curves. Cumulative event estimates were generated using hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals in Cox proportional hazards models. Adjustment for continuous data was performed using multiple-effects models. The primary analysis was based on intention-to-treat (ITT), and a secondary per-protocol analysis was performed for both primary and secondary outcomes. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant and all analyses were two-sided. We originally planned to perform an interim analysis between the groups when the study had reached 50% of the total sample size. However, in response to a subsequently retracted article by Mehra et al. [26], the Danish Medicines Agency demanded that we performed an extraordinary acute interim analysis (without unmasking) on the first 75 patients who had been recruited. This was reviewed by the DSMB, who recommended continuing to accrue patients (May 2020). The first planned interim analysis was conducted at 117 patients (50% recruited), and the trial was stopped due to futility (February 2021). Sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome included 1) a modified ITT population of patients who received part or complete treatment with the intervention (all days); 2) a per-protocol population who received both interventional drugs for all planned days; and 3) a multiple-effects adjusted model for the primary outcome, in which adjustment was made for the following parameters: 1) age (per year increase), 2) sex (male versus female), 3) body mass index (per unit increase), 4) oxygen therapy at inclusion (yes versus no), 5) remdesivir (yes versus no), 6) any pre-existing lung disease (obstructive, interstitial or bronchiectasis: yes versus no), 7) diabetes mellitus (yes versus no) and 8) QTc across median (yes versus no). Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and R software (version 3.4.3; R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria).

Stopping the trial

On 1 February 2021, the trial was stopped for futility based on recommendations from the DSMB who met on 29 January 2021 and discussed the report from the first planned interim analysis. The maximum post-conditional power to cross any boundary in the O'Brien–Fleming plot [27] was 0.064, which was below the threshold of 0.2 communicated from the steering committee to the DSMB prior to the meeting. The interim analyses were performed in accordance with the trial monitoring guidelines. After reviewing the post-conditional power, the remaining data in the interim analysis and the available published data, the DSMB recommended stopping the trial on grounds of futility (the DSMB recommendation is included in the supplementary material (appendix 4)).

Results

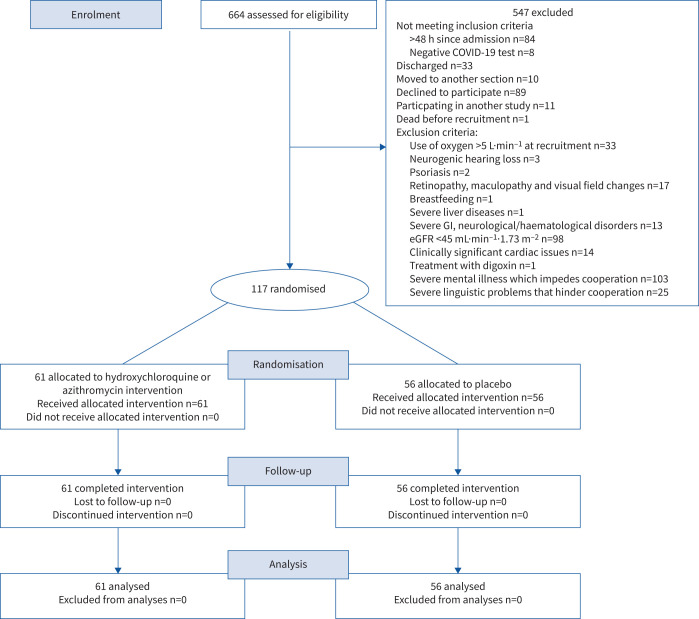

Out of the 664 patients screened, 117 were eligible for study inclusion (figure 1). Reasons for exclusion included inability to give informed consent (18.8% of exclusions); eGFR <45 mL·min−1·1.73 m−2 (17.9% of exclusions); and declined to participate (16.3% exclusions). Of the patients enrolled, 61 patients were randomised to the azithromycin plus hydroxychloroquine arm and 56 to the placebo arm. Participants had a median (interquartile range (IQR)) age of 65 (52–77) years and 65 (56%) of them were male. The median (IQR) time since symptom onset was 8 (4–10) days. Baseline characteristics of patients randomised to the intervention and placebo groups are presented in table 1, and in supplementary tables E1 and E2 (appendix 3).

FIGURE 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting of Randomised Trials diagram. COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019; GI: gastrointestinal; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate.

TABLE 1.

Baseline patient demographic and clinical characteristics

| All | Hydroxychloroquine plus azithromycin | Placebo | |

| Patients | 117 | 61 | 56 |

| Age, years | 65 (52–77) | 68 (52–80) | 63 (52–74) |

| Male | 65 (56) | 36 (59) | 29 (52) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 98 (84) | 53 (87) | 45 (80) |

| African (including Afro-American) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| Asian | 12 (10) | 6 (10) | 6 (11) |

| Unknown/other | 6 (5) | 2 (3) | 4 (7) |

| Body mass index, kg·m–2 | 27.2 (24.8–32.2) | 29.0 (24.9–33.3) | 26.8 (24.6–31) |

| Smoking characteristics | |||

| Current smoker | 6 (5) | 4 (7) | 2 (4) |

| Ex-smoker | 48 (41) | 29 (48) | 19 (34) |

| Never-smoker | 63 (54) | 28 (46) | 35 (62) |

| Pack-years (current and ex-smokers), years | 20 (8–35) | 20 (8–35) | 25 (10–35) |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Asthma | 26 (22) | 12 (20) | 14 (25) |

| COPD | 10 (9) | 8 (13) | 2 (4) |

| Bronchiectasis | 4 (3) | 3 (5) | 1 (2) |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 6 (5) | 3 (5) | 3 (5) |

| Heart failure | 8 (7) | 5 (8) | 3 (5) |

| Diabetes | 28 (24) | 17 (15) | 11 (9) |

| Chronic renal insufficiency | 8 (7) | 5 (8) | 3 (5) |

| Time since symptom onset, days | 8 (4–10) | 7 (4–10) | 8 (5–11) |

| Use of oxygen therapy | 69 (59) | 34 (56) | 35 (62) |

| Use of continuous positive airway pressure | 23 (20) | 12 (20) | 11 (20) |

| Use of noninvasive mechanical ventilation | 4 (3) | 3 (5) | 1 (2) |

| Infiltrate(s) on chest radiograph | 85 (73) | 43 (70) | 42 (75) |

| Oxygen use, L·min–1 | 1 (0–2) | 0 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) |

| Clinical findings | |||

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 125 (115–137) | 127 (118–141) | 122 (111–134) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 74 (65–82) | 76 (68–87) | 72 (63–79) |

| Heart rate, beats·min–1 | 77 (69–86) | 78 (71–89) | 74 (68–84) |

| Oxygen saturation with nasal oxygen, % | 95 (94–97) | 95 (94–97) | 95 (94–97) |

| Respiratory rate, breaths·min–1 | 19 (18–20) | 19 (18–20) | 18 (18–20) |

| Temperature, °C | 37.2 (36.8–37.8) | 37.2 (36.8–37.8) | 37.2 (36.9–37.7) |

| Laboratory measurements | |||

| Leukocyte count, ×109 cells·L–1 | 5.9 (4.6–8.0) | 5.8 (4.6–7.9) | 5.9 (4.5–9.0) |

| Blood eosinophil count, ×109 cells·L–1 | 0.01 (0.00–0.04) | 0.02 (0.01–0.05) | 0.01 (0.00–0.02) |

| C-reactive protein, mg·L–1 | 62 (36–130) | 58 (37–120) | 71 (34–132) |

| Fibrin D-dimer, mg·L–1 | 0.60 (0.37–1.20) | 0.55 (0.37–1.35) | 0.68 (0.36–1.10) |

| Ferritin, µg·L–1 | 458 (221–1100) | 410 (176–1060) | 504 (262–1102) |

| Lactate dehydrogenase, U·L–1 | 278 (218–346) | 270 (214–342) | 278 (233–351) |

| Arterial blood gas | |||

| PCO2 (baseline), mmHg | 35.0±6.8 | 35.9±8.3 | 34.1±4.9 |

| PO2 (baseline), mmHg | 72.8±22.5 | 72.5±26.0 | 73.2±18.5 |

| HCO3– (baseline), mmHg | 23.93±3.74 | 24.39±4.44 | 23.46±2.86 |

| pH (baseline) | 7.46±0.04 | 7.46±0.04 | 7.46±0.03 |

| QTc(F) | 417 (401–436) | 414 (400–436) | 420 (404–434) |

| Remdesivir use | 28 (25) | 13 (22) | 15 (28) |

| Dexamethasone use | 36 (32) | 17 (28) | 19 (35) |

Data are presented as n, median (interquartile range), n (%) or mean±sd. PCO2: carbon dioxide tension; PO2: oxygen tension; HCO3–: bicarbonate; QTc(F): corrected QT interval.

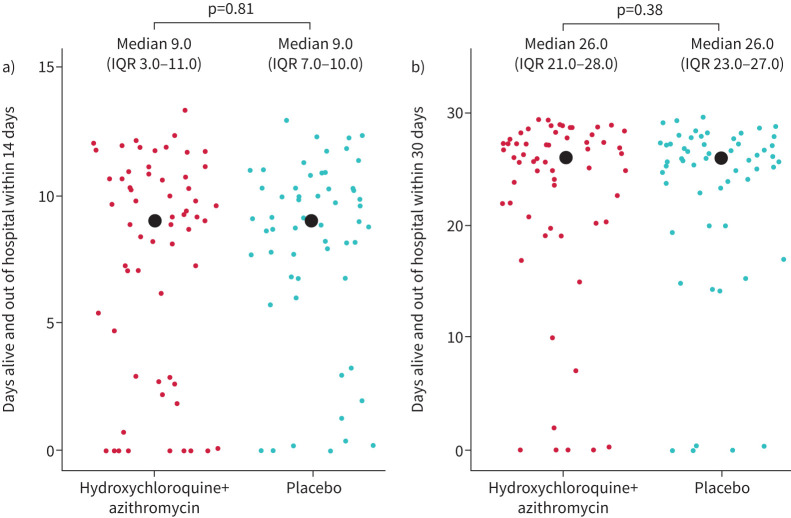

Primary outcome

Primary outcome assessment after randomisation was completed for 117 (100%) patients. We observed no significant difference between the two randomised groups for the primary outcome of DAOH14: median (IQR) 9.0 (3–11) DAOH14 in the hydroxychloroquine plus azithromycin group versus 9.0 (7–10) DAOH14 in the placebo group (p=0.91) (table 2, figure 2).

TABLE 2.

Primary and secondary outcomes

| Hydroxychloroquine plus azithromycin | Placebo | p-value | |

| Primary outcome | |||

| ITT | |||

| DAOH14 | 9.0 (3.0–11.0) | 9.0 (7.0–10.0) | 0.90 |

| Adjusted# DAOH14, estimated mean difference (95% CI) | −0.7 (−2.2–0.8) | Ref. | 0.36 |

| Modified ITT | |||

| DAOH14 | 9.0 (3.0–11.0) | 9.0 (7.0–10.0) | 0.94 |

| Per-protocol | |||

| DAOH14 | 10 (9.0–11.0) | 10 (7.0–10.0) | 0.11 |

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| Admitted to ICU | 4 (6.6) | 3 (5.4) | 0.78 |

| Days at ICU or dead within 14 days | 14 (9.5–14) | 11 (4–14) | 0.46 |

| NIV | 3 (4.9) | 1 (1.8) | 0.35 |

| Days on NIV or death <14 days, mean (95% CI), days | 6.7 (–9.1–22.4) | 9.0 (NA) | 0.78 |

| Mortality at 30 days | 1 (1.6) | 2 (3.6) | |

| Mortality at 30 days, unadjusted HR (95% CI) | 0.5 (0.0–5.0) | Ref. | 0.52 |

| Mortality at 30 days, adjusted# HR (95% CI) | 0.08 (0.001–11.7) | Ref. | 0.32 |

| Duration of hospitalisation, days | 4 (2–8) | 4 (3–6) | 0.73 |

| Days alive and out of hospital at 30 days | 26 (21–28) | 26 (23–27) | 0.88 |

| Readmission or death within 30 days | 9 (7.7) | 6 (5.1) | |

| Time to readmission or death <30 days, HR (95% CI) | 1.4 (0.5–3.8) | Ref. | 0.57 |

| Time to readmission or death <30 days, adjusted# HR (95% CI) | 1.2 (0.3–4.2) | Ref. | 0.76 |

| Change in pH (day 1–day 4), mean (95% CI) | 0.0 (–0.03–0.01) | 0.0 (–0.02–0.01) | 0.44 |

| Change in PO2 (day 1–day 4), mean (95% CI), mmHg | –3.0 (–9.8–3.9) | –0.2 (–8.3–7.8) | 0.70 |

| Change in PCO2 (day 1–day 4), mean (95% CI), mmHg | 1.7 (–0.7–4.0) | 1.4 (–0.4–3.3) | 0.86 |

| Time to no oxygen, unadjusted HR (95% CI) | 0.8 (0.5–1.5) | Ref. | 0.52 |

| Time to no oxygen, adjusted# HR (95% CI) | 0.4 (0.2–1.0) | Ref. | 0.04 |

| QTc (F) >500 ms | 0 (0) | 2 (4.0) | 0.23 |

Data are presented as median (interquartile range) or n (%), unless otherwise stated. ITT: intention to treat; DAOH14: days alive and out of hospital at 14 days; ICU: intensive care unit; NIV: noninvasive ventilation; HR: hazard ratio; PO2: oxygen tension; PCO2: carbon dioxide tension; QTc: corrected QT interval; NA: not applicable. #: adjusted for age (per year increase), sex, body mass index (per unit increase), oxygen supply at baseline (yes/no), pre-existing lung disease (yes/no), diabetes (yes/no), remdesivir (yes/no), QTc across median (yes/no).

FIGURE 2.

Days alive and out of hospital at a) 14 days and b) 30 days. IQR: interquartile range.

Secondary outcomes

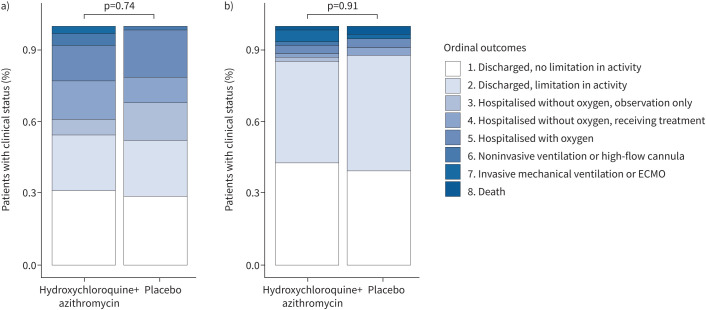

At 15 days after randomisation, there was no significant difference between the hydroxychloroquine plus azithromycin group and the placebo group in COVID outcomes scale score (OR 1.0, 95% CI 0.5–2.2; p=0.91; figure 3 and supplementary table E6 (appendix 3)). A post hoc analysis of the ordinal outcome at day 5 was requested by the steering committee after unblinding to provide a time-updated assessment of clinical status; this analysis also suggested that the two groups were similar (OR 0.9, 95% CI 0.4–1.8; figure 3 and supplementary table E7 (appendix 3)). In addition, we found no differences between the groups in the pre-specified subsidiary clinical outcomes (table 2, figure 2). We tested for an interaction between the trial intervention and symptom duration (<8 days versus ≥8 days) and found no interaction (p=0.79).

FIGURE 3.

Clinical status (coronavirus disease 2019 outcomes scale category) on a) day 5 and b) day 15. ECMO: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Adverse event data are presented in table 3 and supplementary table E8 (appendix 3). During follow-up, one (1.64%) out of 61 patients in the hydroxychloroquine plus azithromycin group and two (3.6%) out of 56 patients in the placebo group had a recorded QTc >500 ms (table 2). Adverse events involving diarrhoea (n=12 versus n=3), nausea (n=11 versus n=6) and dizziness (n=10 versus n=3) were more frequent in the hydroxychloroquine plus azithromycin patient group than in the placebo group. Conversely, adverse events involving a prolonged QTc (>470 ms for females and >480 ms for males) were more frequent in the placebo group (n=4 versus n=7). Only two serious adverse events were reported, both in the placebo group (supplementary table E8 (appendix 3)).

TABLE 3.

Adverse events

| All adverse events | Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin | Placebo | |

| Cardiac disorders | |||

| Prolonged QTc | 11 | 4 | 7 |

| Chest pain | 7 | 3 | 4 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | |||

| Diarrhoea | 15 | 12 | 3 |

| Vomiting | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Nausea | 17 | 11 | 6 |

| Abdominal pain | 14 | 7 | 7 |

| Nervous system and psychiatric disorders | |||

| Headache | 8 | 3 | 5 |

| Dizziness | 13 | 10 | 3 |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | |||

| Bronchospasm | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | |||

| Itching | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Rash | |||

| Vascular disorders | |||

| Bleeding | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Any serious adverse events | 2 | 0 | 2 |

Data are presented as n. QTc: corrected QT interval.

Discussion

The ProPAC-COVID trial was stopped at half recruitment based on pre-specified futility criteria after a recommendation from the DSMB, in agreement with monitoring guidelines. Compared to placebo, the combination of azithromycin and hydroxychloroquine did not seem to have any effect on the measured outcomes. The primary outcome, DAOH14, was similar in both arms, as was the ordinal outcome measure and the rates of death from all causes and readmissions.

Our trial is the first to report on this combination of hydroxychloroquine plus azithromycin administered in normal recommended doses for 15 days versus placebo. Other trials have reported either a mono-drug intervention versus placebo or higher doses of hydroxychloroquine plus azithromycin versus one of these drugs.

One previous trial has reported on a dosing regimen of hydroxychloroquine similar to ours [28], albeit for a period of 5 days and without azithromycin; that trial was also stopped for futility and reported neutral results. In our trial, the study participants were generally not severely ill, which was congruent with the intention and rationale of the trial: to reduce viral replication (hydroxychloroquine) and hyperinflammation (azithromycin) before organ failure was evident. Some of the reasons that this combination of drugs failed to benefit patients with COVID-19 may include inability of the drugs to penetrate into the airway epithelium, lower potency in vivo than in vitro and neutralisation of beneficial and harmful effects.

Although we are aware that the trial may have had insufficient power to analyse all the pre-specified outcome measures, the uniform neutrality of all the analysed outcomes strongly suggests that the intervention resulted in no benefit or harm. Of special interest, we used the recommended doses of the two drugs and respected the contraindications of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin when recruiting participants, and we did not observe changes in cardiac rhythm nor the QTc(F). Other trials investigating hydroxychloroquine/chloroquine have reported such changes, but in those trials, substantially higher doses than are recommended for other indications were used [29, 30].

Our results are consistent with those from other trials investigating the effects of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin separately. A possibility of “neutralising” harm from drug toxicity and potential benefits against COVID-19 exists, although this is not considered to be likely, since we did not observe a higher incidence of serious adverse effects in the intervention arm. A recent placebo-controlled trial by Self et al. [28], investigating the effects of a 5-day treatment course of hydroxychloroquine at a similar dose to our trial, was also stopped for futility (close to the target sample size) and was neutral with regards to all outcome measures. In the open-label RECOVERY trial [31], 500 mg of daily azithromycin for 10 days produced no benefit or harm, which was consistent with results from the COALITION II trial in which an identical azithromycin regimen was compared to placebo when added to high-dose hydroxychloroquine (800 mg·day–1). In the COALITION I trial [32], patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 were randomised to open-label treatment with 1) standard care; 2) high-dose hydroxychloroquine for 7 days; or 3) a combination of high-dose hydroxychloroquine (800 mg daily) and high-dose azithromycin (500 mg daily) for 7 days. The results were neutral on all outcomes, except for QTc, which was significantly longer in the two actively treated groups. Taken together, all the trials that tested hydroxychloroquine versus standard care, azithromycin versus standard care or azithromycin plus hydroxychloroquine have produced neutral results, except with regard to the QTc, which has been somewhat higher in patients who received high-dose hydroxychloroquine/chloroquine. Trial patients who received normal recommended doses of hydroxychloroquine/chloroquine did not exhibit prolonged QTc values.

One strength of the present study is that all enrolled patients had RT-PCR-confirmed COVID-19; in other trials exploring these drugs, patients with suspected but not necessarily confirmed COVID-19 were enrolled [29, 31, 32]. Additionally, the double-blind and placebo-controlled design is an important strength, especially when comparing outcomes such as the ordinal outcome and length of hospitalisation, which are heavily influenced by physician decisions. The discontinuation of the present study before full recruitment may be considered a limitation. However, we did use a relatively sensitive primary outcome. For the current study with admitted patients with lower respiratory tract infection, the standard deviation is 3.5–4.0 [23, 33]. Using this, and setting the detection limit at 1.5 days’ change (both ways) in DAOH, we reached the sample size, the trial was planned for. It can be discussed whether 1.5 days’ change is sensitive enough; however, the study group decided that if DAOH could not change by ≥1.5 days, we would consider the effect to be of limited clinical value. At the time of trial termination, the chance of crossing a boundary of efficacy or harm was very low and when considered in the context of the evidence currently available, it seems unlikely that further recruitment would have demonstrated any effect. As the median time from onset of symptoms was 8 days, the study intervention could potentially have an effect if administered earlier in the course of the disease. However, this has not been studied in other trials. Our trial cannot answer this question directly; however, such an effect in patients with a shorter duration of symptoms seems unlikely, as this had no effect on our results since there was no interaction between the study intervention and symptom duration regarding the primary outcome. Thus, we conclude that our trial results were neutral. The combination of azithromycin and hydroxychloroquine did not increase the likelihood of survival or discharge from hospital of patients with COVID-19. This conclusion is consistent with recent European Respiratory Society COVID-19 guidelines [34], which reported no clinical benefits associated with using hydroxychloroquine and/or azithromycin to treat patients hospitalised with COVID-19 (in the absence of bacterial infection).

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplement 1. Study protocol. ERJ-00752-2021.Appendix_1 (371.2KB, pdf)

Supplement 2. Statistical analysis plan. ERJ-00752-2021.Appendix_2 (338.3KB, pdf)

Supplement 3. ProPAC-COVID-trial group and additional results, including adverse events and supplementary tables and figures ERJ-00752-2021.Appendix_3 (436.8KB, pdf)

Supplement 4. a) Interim analysis (extraordinary), May 2020. b) Interim analysis (planned), 29 January 2021. c) DSMB recommendation(extraordinary IA), May 2020. d) DSMB recommendation (planned), 1 February 2021. ERJ-00752-2021.Appendix_4 (717KB, pdf)

Shareable PDF

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the relevant departments in Denmark for allowing us to recruit patients. We would also like to thank the COP:TRIN steering committee for their helpful advice. We also gratefully acknowledge the DSMB and chief pharmacist Kristian Østergaard Nielsen (Glostrup Pharmacy, Glostrup, Denmark) for their excellent work. In particular, we would like to thank the great team behind ProPAC COVID, especially Mohamad Isam Saeed, Jens-Kristian Bomholt-Riis, Anna Kjær Kristensen and Katja Bergenholtz (Respiratory Research Unit, Gentofte Hospital, Hellerup, Denmark). The ProPAC-COVID study is an initiative by the independent research network COP:TRIN (www.coptrin.dk).

Footnotes

This article has supplementary material available from erj.ersjournals.com

This article has an editorial commentary: https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.02002-2021

The members of the writing group of the ProPAC-COVID Study Group assume responsibility for the overall content and integrity of this article.

This study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov with identifier NCT04322396. It is the opinion of the COP:TRIN steering committee that knowledge sharing increases the quantity and quality of scientific results. Requests for trial information can be submitted to the project management team (J-U.S. Jensen, C.S. Ulrik and P. Sivapalan) who will consider the request. Any reasonable requests will then be discussed with the COP:TRIN Steering Committee.

Author contributions: Concept and design: P. Sivapalan, C.S. Ulrik and J-U.S. Jensen; acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data: P. Sivapalan, C.S. Ulrik, J. Eklöf, A. Jordan, T.S. Lapperre, R.D. Bojesen, A. Browatzki, J.T. Wilcke, V. Gottlieb, K.E.J. Håkansson, C. Tidemandsen, O. Tupper, H. Meteran, C. Bergsøe, U. Bødtger, D. Bech Rasmussen, S. Graff Jensen, L. Pedersen, H. Priemé, C. Søborg, I.E. Steffensen, D. Høgsberg, M.S. Frydland, P. Lange, A. Sverrild, M. Ghanizada and J-U.S. Jensen; drafting the manuscript: P. Sivapalan and J-U.S. Jensen; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all the authors; statistical analysis: P. Sivapalan, J-U.S. Jensen, A. Jordan, T.W. Klausen and J. Eklöf; obtaining funding: J-U.S. Jensen; administrative, technical and material support: J-U.S. Jensen, V. Gottlieb; supervision: J-U.S. Jensen, F.K. Knop, T. Biering-Sørensen and J.D. Lundgren. Role of the corresponding author: initiator and study director.

Conflict of interest: P. Sivapalan reports fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, outside the submitted work. C.S. Ulrik reports fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, AZ, GSK, TEVA, Novartis, ALK-Abello, Mundipharma, Sanofi Genzyme, Orion Pharma and Actelion, outside the submitted work. K.E.J. Håkansson reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, Chiesi and TEVA, outside the submitted work. T. Biering-Sørensen has received research grants from GE Healthcare and Sanofi Pasteur, as well as personal fees from Sanofi Pasteur, Novartis and Amgen, outside the submitted work. None of the other authors have any conflicts of interest.

Support statement: The study was funded by The Novo Nordisk Foundation (grant number: NNF20SA0062834). The research salary of P. Sivapalan was sponsored by Herlev and Gentofte Hospital, University Hospital of Copenhagen. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study, in the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. This trial was not supported in any form by the pharmaceutical industry. P. Sivapalan and J-U.S. Jensen had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analyses. Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

References

- 1.Savarino A, Boelaert JR, Cassone A, et al. . Effects of chloroquine on viral infections: an old drug against today's diseases? Lancet Infect Dis 2003; 3: 722–727. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00806-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vincent MJ, Bergeron E, Benjannet S, et al. . Chloroquine is a potent inhibitor of SARS coronavirus infection and spread. Virol J 2005; 2: 69. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-2-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fantini J, Di Scala C, Chahinian H, et al. . Structural and molecular modelling studies reveal a new mechanism of action of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2020; 55: 105960. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee SJ, Silverman E, Bargman JM. The role of antimalarial agents in the treatment of SLE and lupus nephritis. Nat Rev Nephrol 2011; 7: 718–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Albert RK, Connett J, Bailey WC, et al. . Azithromycin for prevention of exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 689–698. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibson PG, Yang IA, Upham JW, et al. . Effect of azithromycin on asthma exacerbations and quality of life in adults with persistent uncontrolled asthma (AMAZES): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2017; 390: 659–668. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31281-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Altenburg J, de Graaff CS, Stienstra Y, et al. . Effect of azithromycin maintenance treatment on infectious exacerbations among patients with non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis: the BAT randomised controlled trial. JAMA 2013; 309: 1251–1259. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.1937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawamura K, Ichikado K, Takaki M, et al. . Adjunctive therapy with azithromycin for moderate and severe acute respiratory distress syndrome: a retrospective, propensity score-matching analysis of prospectively collected data at a single center. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2018; 51: 918–924. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chalmers JD, Boersma W, Lonergan M, et al. . Long-term macrolide antibiotics for the treatment of bronchiectasis in adults: an individual participant data meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med 2019; 7: 845–854. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30191-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hiles SA, McDonald VM, Guilhermino M, et al. . Does maintenance azithromycin reduce asthma exacerbations? An individual participant data meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2019; 54: 1901381. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01381-2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fantini J, Chahinian H, Yahi N. Synergistic antiviral effect of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in combination against SARS-CoV-2: what molecular dynamics studies of virus-host interactions reveal. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2020; 56: 106020. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, et al. . Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19 – final report. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 1813–1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nugroho CW, Suryantoro SD, Yuliasih Y, et al. . Optimal use of tocilizumab for severe and critical COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. F1000Res 2021; 10: 73. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.45046.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Casadevall A, Dragotakes Q, Johnson PW, et al. . Convalescent plasma use in the United States was inversely correlated with COVID-19 mortality: did convalescent plasma hesitancy cost lives? medRxiv 2021; preprint [https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.07.21255089]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ACTIV-3/TICO LY-CoV555 Study Group , Lundgren JD, Grund B, et al. . A neutralizing monoclonal antibody for hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2021; 384: 905–914. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2033130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.RECOVERY Collaborative Group , Horby P, Lim WS, et al. . Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with covid-19. N Engl J Med 2021; 384: 693–704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cantini F, Goletti D, Petrone L, et al. . Immune therapy, or antiviral therapy, or both for COVID-19: a systematic review. Drugs 2020; 80: 1929–1946. doi: 10.1007/s40265-020-01421-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sivapalan P, Ulrik CS, Bojesen RD, et al. . Proactive prophylaxis with azithromycin and hydroxychloroquine in hospitalised patients with COVID-19 (ProPAC-COVID): a structured summary of a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2020; 21: 513. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-04409-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sivapalan P, Ulrik CS, Lappere TS, et al. . Proactive prophylaxis with azithromycin and hydroxychloroquine in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 (ProPAC-COVID): a statistical analysis plan. Trials 2020; 21: 867. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-04795-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013; 310: 2191–2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roden DM, Harrington RA, Poppas A, et al. . Considerations for drug interactions on QTc in exploratory COVID-19 treatment. Circulation 2020: 141: e906–e907. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mercuro NJ, Yen CF, Shim DJ, et al. . Risk of QT interval prolongation associated with use of hydroxychloroquine with or without concomitant azithromycin among hospitalized patients testing positive for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol 2020; 5: 1036–1041. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sivapalan P, Lapperre TS, Janner J, et al. . Eosinophil-guided corticosteroid therapy in patients admitted to hospital with COPD exacerbation (CORTICO-COP): a multicentre, randomised, controlled, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Respir Med 2019; 7: 699–709. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30176-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freund Y, Cachanado M, Delannoy Q, et al. . Effect of an emergency department care bundle on 30-day hospital discharge and survival among elderly patients with acute heart failure: the ELISABETH randomised clinical trial. JAMA 2020; 324: 1948–1956. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.19378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ariti CA, Cleland JG, Pocock SJ, et al. . Days alive and out of hospital and the patient journey in patients with heart failure: insights from the candesartan in heart failure: assessment of reduction in mortality and morbidity (CHARM) program. Am Heart J 2011; 162: 900–906. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehra MR, Desai SS, Ruschitzka F, et al. . Hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine with or without a macrolide for treatment of COVID-19: a multinational registry analysis. Lancet 2020; in press [retracted] [ 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31180-6]. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31180-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 27.O'Brien PC, Fleming TR. A multiple testing procedure for clinical trials. Biometrics 1979; 35: 549–556. doi: 10.2307/2530245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Self WH, Semler MW, Leither LM, et al. . Effect of hydroxychloroquine on clinical status at 14 days in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a randomised clinical trial. JAMA 2020; 324: 2165–2176. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.22240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.RECOVERY Collaborative Group , Horby P, Mafham M, et al. . Effect of hydroxychloroquine in hospitalized patients with covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 2030–2040. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2022926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borba MGS, Val FFA, Sampaio VS, et al. . Effect of high vs low doses of chloroquine diphosphate as adjunctive therapy for patients hospitalized with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3: e208857. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.RECOVERY Collaborative Group . Azithromycin in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): a randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet 2021; 397: 605–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cavalcanti AB, Zampieri FG, Rosa RG, et al. . Hydroxychloroquine with or without azithromycin in mild-to-moderate covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 2041–2052. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2019014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walters JA, Tan DJ, White CJ, et al. . Systemic corticosteroids for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 9: CD001288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chalmers JD, Crichton ML, Goeminne PC, et al. . Management of hospitalised adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a European Respiratory Society living guideline. Eur Respir J 2021; 57: 2100048. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00048-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplement 1. Study protocol. ERJ-00752-2021.Appendix_1 (371.2KB, pdf)

Supplement 2. Statistical analysis plan. ERJ-00752-2021.Appendix_2 (338.3KB, pdf)

Supplement 3. ProPAC-COVID-trial group and additional results, including adverse events and supplementary tables and figures ERJ-00752-2021.Appendix_3 (436.8KB, pdf)

Supplement 4. a) Interim analysis (extraordinary), May 2020. b) Interim analysis (planned), 29 January 2021. c) DSMB recommendation(extraordinary IA), May 2020. d) DSMB recommendation (planned), 1 February 2021. ERJ-00752-2021.Appendix_4 (717KB, pdf)

This one-page PDF can be shared freely online.

Shareable PDF ERJ-00752-2021.Shareable (692.3KB, pdf)