Abstract

Background

Kidney transplant services all over the world were severely impacted by the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. The optimum management of kidney transplant recipients with coronavirus disease 2019 remains uncertain.

Material/Methods

We conducted a multicenter cohort study of kidney transplant recipients with coronavirus disease 2019 infection in Saudi Arabia. Multivariable Cox regression analysis was used to study predictors of graft and patient outcomes at 28 days after coronavirus disease 2019 diagnosis.

Results

We included 130 kidney transplant recipients, with a mean age of 48.7(±14.4) years. Fifty-nine patients were managed at home with daily follow-up utilizing a dedicated clinic, while 71 (54.6%) required hospital admission. Acute kidney injury occurred in 35 (26.9%) patients. Secondary infections occurred in 38 (29.2%) patients. SARS-CoV-2 antibodies testing was carried out in 84 patients, of whom 70 tested positive for IgG and/or IgM. Fourteen patients died (10.8%). A multivariable Cox regression analysis showed that age, creatinine at presentation, acute kidney injury, and use of azithromycin were significantly associated with worse patient survival. Graft loss was associated with requiring renal replacement therapy and development of secondary infections.

Conclusions

Despite kidney transplant recipients with coronavirus disease 2019 infection having higher rate of hospital admission and mortality compared to the general population, a significant number of them can be managed using a telemedicine clinic. Most kidney transplant patients seem to mount an antibody response following coronavirus disease 2019 infection, and it remains to be seen if they will have a similar response to the incoming vaccines.

Keywords: Acute Kidney Injury, COVID-19, Kidney Transplantation, Saudi Arabia, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an emerging disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which was first discovered in China in late 2019. This viral infection has spread all over the globe and was declared a pandemic by WHO in March 2020. By April 2021, SARS-CoV-2 had infected almost 145 million persons, causing almost 3 million deaths worldwide. During the same period, Saudi Arabia (SA) reported a total of 409 038 cases, with a 1.8% fatality rate [1]. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, SA implemented lockdown of public and private services and established nationwide restrictions on population movement. As a result, most elective organ transplant activities were halted for several months.

Immunocompromised patients are more vulnerable to viral infections and their devastating consequences. Not infrequently, kidney transplant patients have other comorbidities, such as diabetes, advanced age, pulmonary diseases, ischemic heart disease, and obesity, which are additional risk factors for acquisition and progression of infection [2]. Telemedicine can help to screen and triage suspected or confirmed COVID-19 cases that need hospitalization while minimizing exposure to patients and health care providers.

Due to its novelty, several observations have emerged from cohort studies addressing the clinical presentation and outcomes of COVID-19 in kidney transplant recipients (KTRs). However, there remain uncertainties about the optimal strategies for use of antiviral and immune-modulating agents, and management of immunosuppression (IS) [3]. Similarly, limited data are available about the duration of SARS-CoV-2 viral shedding, period of isolation required, and the immune response in this population [4].

In this multicenter study of kidney transplant patients with COVID-19, we investigated the clinical outcomes, duration of viral shedding, and immune response to SARS-CoV-2. The aim of this study was to enhance the knowledge in the transplant community regarding this novel disease.

Material and Methods

This was a retrospective observational cohort study that was carried out in 5 transplant centers in SA. Inclusion criteria included all adult patient (age >16 years) KTRs with a positive SARS-CoV-2 test result by real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (rt-PCR) between March 1 and August 31, 2020. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of all participating centers.

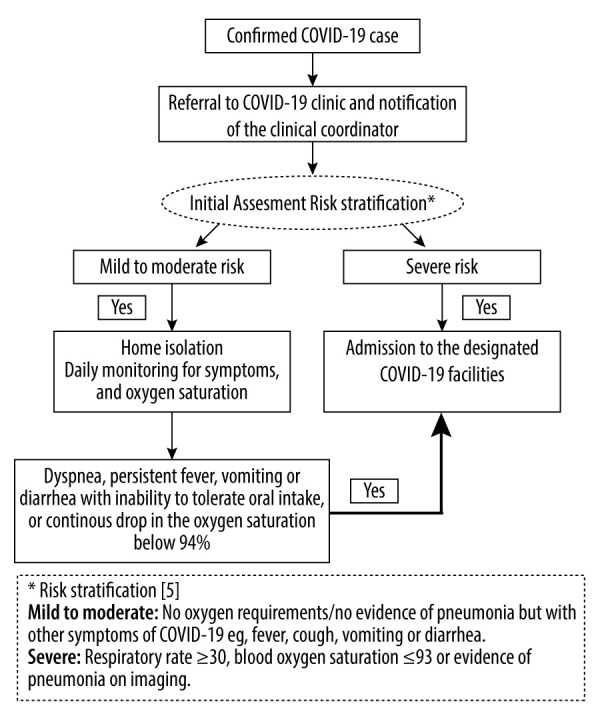

According to the national risk stratification for SARS-CoV-2 infection [5], patients with mild to moderate symptoms were managed as outpatients. We created a dedicated COVID-19 clinic which consisted of a transplant nephrologist and a clinical coordinator (Figure 1). Patients with confirmed infection that did not require hospital admission upon initial assessment were asked to self-isolate at home. A hotline for direct communication with the clinical coordinator was established, and patients were provided with pulse oximeters. Patients were asked to monitor their symptoms, temperature, and oxygen saturation. Symptoms like dyspnea, persistent fever, vomiting or diarrhea with inability to tolerate oral intake, as well as drop in the oxygen saturation below 94%, were an indication to visit the emergency department. Patients were contacted daily by the coordinators for updates. Laboratory and radiological investigations were done through a designated ambulatory clinic. A kidney transplant recipient with close contact with a COVID-19 case within the family or in the community, but with no symptoms, was instructed to self-isolate and monitor symptoms. Such patients were tested for SARS-CoV-2 at day 5 and day 14 from the last exposure to the index case.

Figure 1.

Workflow chart for kidney transplant recipients with confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 infection.

More severe cases were admitted to the hospital, where they were treated by a specific protocol that provided recommendations on IS management, in addition to the national guidelines for COVID-19 treatment, which included recommendations for antiviral and antibacterial therapies, anticoagulation, and other therapeutic interventions like the use of tocilizumab and convalescent plasma [5].

We collected data on baseline patient characteristics, symptoms, laboratory, radiological findings at presentation, concomitant infections, management of IS, other therapeutic interventions, and duration of viral shedding, as well as ICU admissions, respiratory support, AKI, requirement of renal replacement therapy, and 28-day graft and patient outcomes.

SARS-CoV-2 antibodies (IgG and IgM) were studied in 84 patients using rapid membrane-based lateral flow immunoassay (PRIMA lab SA, Switzerland). Data were extracted onto a unified data collection template from the electronic medical records.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive results are presented as mean±standard deviation for normally distributed data, or median with interquartile range for non-normally distributed data. Numbers and percentages are reported for all qualitative variables. Bivariate analysis was used to explore the correlation of clinical and laboratory characteristics with the overall patient and graft survival using the Cox proportional hazard model. All the statistically significant predictors in the bivariate analysis and clinically important variables were entered in a multiple Cox proportional hazard model. The final model was assessed using the goodness-of-fit test to see if the model fit the data. Adjusted hazard odds ratio and 95% confidence interval were reported for each independent factor. Two-sided P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 24.0.

Results

Patient Characteristics

During the study period, the participating centers identified 130 KTRs with a diagnosis of COVID-19 among their patients. Demographics, comorbidities, and baseline IS are listed in Table 1. Mean age was 48.7 (±14.4) years, and 78 (60%) were male. Diabetes mellitus was the most common cause of end-stage renal disease in 40 (30.8%) patients. There were 104 (80%) patients with a living kidney transplant, and most were on maintenance prednisone, tacrolimus, and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), while 83.8% of patients had been transplanted more than 1 year before the time of their COVID-19 diagnosis. Two patients were diagnosed with acute rejection within 90 days prior to SARS-CoV-2 infection, one of whom received anti-thymocyte globulin. The source of SARS-CoV-2 infection was mainly through family contact in 79 (60.8%).

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics.

| Factors | Results (n=130)* |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 78 (60%) |

| Female | 52 (40%) |

| Age in years | 48.7±14.4 |

| Body mass index (BMI) | 29.8±6.9 |

| Blood group | |

| A | 36 (27.6%) |

| AB | 6 (4.6%) |

| B | 29 (22.3%) |

| O | 59 (45.3%) |

| Type of transplant | |

| Deceased donor | 26 (20%) |

| Living | 104 (80%) |

| Cause of end-stage renal disease | |

| Diabetes | 40 (30.8%) |

| Glomerulonephritis | 24 (18.5%) |

| Hypertension | 14 (10.8%) |

| Others | 52 (40%) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Diabetes | 58 (44.6%) |

| Hypertension | 103 (79.2%) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 22 (16.9%) |

| Smoking | 37 (28.5%) |

| Other | 65 (50%) |

| Immunosuppression | |

| Steroid | 128 (98.5%) |

| Tacrolimus | 125 (96.2%) |

| Mycophenolate | 121 (93.1%) |

| Others | 6 (4.6%) |

| Time from transplant to first positive test | |

| ≤1 year | 21 (16.2%) |

| >1 year | 109 (83.8%) |

| Source of COVID-19 infection | |

| Family | 79 (60.8%) |

| Community | 29 (22.3%) |

| Unknown | 22 (16.9%) |

Results are expressed as mean±standard deviation, and number (percentage).

Clinical Presentation

Clinical features at presentation, including laboratory results and radiological findings, are summarized in Table 2. The most prevalent symptoms were fatigue, fever, and cough (62.3%, 60%, and 57.7%, respectively). Diarrhea was reported in 25.4% and nausea and vomiting in 22.3% of patients. Alteration in taste and smell was reported in 25 (19.2%) patients.

Table 2.

Clinical presentation and initial investigations.

| Factors | Results (n=130)* |

|---|---|

| Symptoms at presentation | |

| Fatigue | 81 (62.3%) |

| Fever | 78 (60%) |

| Cough | 75 (57.7%) |

| Shortness of breath | 38 (29.2%) |

| Diarrhea | 33 (25.4%) |

| Nausea/vomiting | 29 (22.3%) |

| Headache | 27 (20.8%) |

| Alteration in taste or smell | 25 (19.2%) |

| Initial radiological and laboratory findings | |

| Abnormal chest X-ray | 43 (33.1%) |

| White blood cell count ×109/La | 5.75±2.39 |

| Absolute lymphocyte count | 1.22±0.88 |

| Creatinine at presentation (μmol/L)**b | 99 (79–131.5) |

| Procalcitonin (ng/mL)c | 0.24 (0.13–0.79) |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L)d | 40.4 (15.4–80) |

| D-dimer (μg/L)e | 1.05 (0.59–1.4) |

Results are expressed as mean±standard deviation, median (25th–75th percentile) and number (percentage);

patients with graft failure were excluded.

White blood cell count (normal range 4.5–11×109/L);

creatinine (normal range 62–115 μmol/L);

procalcitonin (normal range 0–0.1 ng/mL);

C-reactive protein (normal range 0–5 mg/L);

D-dimer (normal range 0–0.55 μg/L).

Initial investigations showed mean white blood cell count (WBC) of 5.8 X109/L (±2.4), with absolute lymphocyte count of 1.2±0.9, and a median C-reactive protein (CRP) of 40.4 mg/L (IQR 15.4–80). At presentation, median creatinine was 99 μmol/L (IQR 79–131.5), and 43 (33.1%) patients had an abnormal chest X-ray result.

During a median follow-up of 35 days (IQR 29–44.25), 71 (54.6%) patients required hospital admission, and the remaining 59 (45.4%) were managed as outpatients.

Treatment and Outcomes

Prednisone and MMF doses were adjusted in 100 (76.9%) and 115 (88.5%) patients, respectively, while tacrolimus dose was adjusted in 45 (34.7%) patients. In terms of therapeutic interventions, azithromycin was used in 40 (30.8%) patients, favipiravir in 26 (20%) patients, and hydroxychloroquine in 15 (11.5%) patients. Seven patients (5.4%) received tocilizumab and convalescent plasma each (Table 3).

Table 3.

Treatment and clinical outcomes.

| Factors | Results (n=130) |

|---|---|

| Therapeutic interventions | |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 15 (11.5%) |

| Azithromycin | 40 (30.8%) |

| Tocilizumab | 7 (5.4%) |

| Favipiravir | 26 (20%) |

| Convalescent serum or plasma | 7 (5.4%) |

| Modification of immunosuppression | |

| Tacrolimus adjustment | 45 (34.6%) |

| Mycophenolate adjustment | 115 (88.5%) |

| Steroid adjustment | 100 (76.9%) |

| ICU admission | 28 (21.5%) |

| Length of ICU stay (days) | 11 (7.25–24) |

| Respiratory support modality | 43 (33.1%) |

| Nasal cannula | 16 (37.2%) |

| High-flow nasal cannula | 8 (18.6%) |

| Intubation/mechanical ventilation | 18 (41.9%) |

| Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation | 1 (2.3%) |

| Requirement of pressor support | 14 (10.8%) |

| Acute kidney injury | 35 (26.9%) |

| Requirement of renal replacement therapy | 8 (6.2%) |

| Secondary infections | 38 (29.2%) |

| Bacterial | 29 (76.3%) |

| Fungal | 3 (7.9%) |

| Cytomegalovirus | 6 (15.8%) |

| Mortality | 14 (10.8%) |

| Graft loss** | 1 (0.77%) |

| Length of follow-up (days) | 35 (29–44.25) |

Results are expressed as mean±standard deviation, median (25th–75th percentile) and number (percentage);

censored for death.

Among the hospitalized patients, 28 (21.5%) needed ICU admission, with a median stay of 11 days (IQR 7.25–24). Respiratory support was required in 43 (33%) patients, 18 (41.9%) of whom required intubation and mechanical ventilation. Fourteen patients (10.8%) needed vasopressor support.

AKI occurred in 35 (26.9%) patients, with 8 (6.2%) patients requiring dialysis. Secondary infections occurred in 38 (29.2%) patients; bacterial in 29 patients, cytomegalovirus (CMV) viremia in 6 patients, and fungal infection in 3 patients (Table 3).

There were 14 deaths (10.8%). All deaths were due to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), except for one patient who died suddenly at home. One patient lost his graft due to renal artery thrombosis.

Eighty-four patients had a SARS-CoV-2 PCR test first repeated at a mean of 17.2 (±7.6) days, when 59 (70.2%) were still positive. Mean time to testing SARS-CoV-2 PCR-negative was 31.5 (±16.2) days after the diagnosis. SARS-CoV-2 antibodies testing was carried out in 84 (64.6%) patients, with 70 (83%) testing positive for IgG and/or IgM, after a median of 30 days (IQR 20–40).

A multivariable Cox regression analysis using variables meeting significance in a bivariate analysis showed that age, creatinine level at presentation, development of AKI, and use of azithromycin were significantly associated with worse patient survival (Table 4). Graft loss was associated with requiring renal replacement therapy and development of secondary infections (Table 5).

Table 4.

Multivariable Cox regression analysis to identify significant factors associated with adverse patient survival.

| Factors | Adjusted Hazard ratio (AHR) | 95% confidence interval for AHR | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.06 | 1.013–1.109 | 0.012 |

| Creatinine at presentation | 1.002 | 1.00–1.004 | 0.016 |

| Use of azithromycin | 6.380 | 1.374–29.630 | 0.018 |

| Acute kidney injury | 18.11 | 2.244–146.21 | 0.007 |

Table 5.

Multivariable Cox regression analysis to identify significant factors associated with graft loss.

| Factors | Adjusted Hazard ratio (AHR) | 95% confidence interval for AHR | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Requirement of renal replacement therapy | 5.05 | 1.67–15.24 | 0.004 |

| Development of secondary infections | 13.38 | 2.69–66.343 | 0.001 |

Discussion

We report the clinical outcomes of 130 KTRs with COVID-19 in 5 transplant centers across SA. Our study showed a 10.8% mortality rate among kidney transplant patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection, with 0.77% graft loss.

The COVID-19 pandemic presents a major challenge to health care systems worldwide. Appropriate and timely provision of care is important when dealing with high-risk patients such as KTRs. Given the large number of infected people and with limited hospital resources, structured outpatient management of KTRs with COVOD-19 via telemedicine appears to be a reasonable approach [6,7]. Clinical presentation was similar to that in the general population [8–10]. In our study, 71 (54.6%) patients required hospital admission, whereas 59 (45.4%) patients were managed in outpatient settings. As with other infections, immune-compromised patients with COVID-19 infections can have delayed or bimodal patterns of presentation [11]. Of note, 14 patients (19.7%) out of the 71 patients who required hospitalization were initially managed though the telemedicine clinic. The median time from the initial positive test result for SARS-CoV-2 infection until hospital admission was 11 days (IQR 4–18). Careful monitoring and frequent assessment for symptoms and disease progression are crucial and help to decide about hospital admission and early therapeutic interventions.

KTRs with COVID-19 present a clinical challenge in the absence of evidence of effective interventions in this immune-suppressed group, often with multiple comorbidities [12]. The optimal management of immunosuppressive medication in KTRs with COVID-19 has not yet been established, and the decision to adjust immunosuppressive medications should consider patient’s age, time since transplant, and the severity of COVID-19 disease and associated comorbidities [3]. Generally, we opted to lower MMF, and to a lesser extent tacrolimus doses, and used corticosteroids as per the evidence that developed over time [13]. So far, there is no strong evidence to guide adjustment of immunosuppressive medication in COVID-19 patients and most of the practice is based on expert’s opinion and small studies [14,15]. We documented no biopsy-proven acute rejection after minimizing immunosuppressive medication in this cohort.

The small number of patients where other therapeutic interventions were used – favipiravir in 26 (20%), hydroxychloroquine in 15 (11.5%), and azithromycin in 40 (30.8%), and tocilizumab, and convalescent plasma in 14 (10.8%) – reflects the degree of uncertainty that prevailed at the start of the pandemic. However, therapeutic options for COVID-19 and its effect on survival have changed since the beginning of the pandemic. For example, azithromycin and hydroxychloroquine were not found to be associated with mortality benefit or other clinical outcomes [16,17]. Antivirals, which block replication, and anti-inflammatories like tocilizumab, are considered part of treatment in most of treatment protocols [5]. Recent reports from the RECOVERY and REMAP-CAP trials showed that treatment with tocilizumab led to lower mortality across patients with different disease severities [18,19]. Two studies using a hamster model of SARS-CoV-2 infection have shown a modest antiviral effect of favipiravir [20,21]. In a retrospective study from 2 hospitals in SA, use of favipiravir was associated with accelerated discharge rate and less progression to mechanical ventilation, but no overall mortality benefits [22].

The threshold to admit KTRs with COVID-19 to hospital or ICU changed as the experience in treating COVID-19 developed in the first few months. In our cohort, of the 71 patients admitted to hospital, 28 (21.5%) needed ICU admission, of whom 18 (13.8%) required intubation and mechanical ventilation. In another single-center study from SA included 44 KTRs; 70% required admission to hospital, with 16% needing ICU, and 1 patient required mechanical ventilation [23]. Another study of 53 kidney transplant patients with COVID-19 reported that 22% required ICU care and 90% of them required mechanical ventilation [24].

Several mechanisms have been postulated for development of AKI in COVID-19 patients, including multiorgan dysfunction syndrome, SARS-CoV-2 direct kidney infection [25], infection-related generalized mitochondrial failure, and cytokine storm syndrome. We used acute kidney injury network criteria to define AKI in our cohort. Thirty-five (26.9%) patients had AKI, and this was associated with poor patient survival. Eight (6.2%) patients required dialysis compared to 21% in the study by Akalin et al [26] and 31% in the TANGO study [27]. In our multivariable Cox regression analysis, requirement of renal replacement therapy was associated with poor graft survival.

Concomitant infections with COVID-19 disease are not uncommon in immunocompromised patients. In our study, bacterial infections occurred in 29 (22.3%) patients, cytomegalovirus (CMV) viremia in 6 (4.6%) patients, and invasive aspergillosis infection in 3 (2.3%) patients. A higher incidence (48%) of bacterial infections was reported by Lubetzky et al [6]. In a meta-analysis of 11 studies, the risk of invasive aspergillosis was greater in KTRs who had post-transplant bacterial infection, respiratory viral infection, and CMV infection or disease [28]. We found that 2 out the 6 patients who had CMV viremia were treated with tocilizumab. Reactivation of CMV with IL-6 antagonist therapy, like tocilizumab, is a potential concern. Khatib et al reported a case of life-threatening lower gastrointestinal bleeding secondary to CMV colitis in a patient with COVID 19 pneumonia who was treated with tocilizumab [29]. Development of secondary infections was significantly associated with poor graft survival in our study. A high index of suspicion for secondary infection with early diagnosis and administration of antimicrobial therapy should be considered when dealing with SARS-CoV 2 infection in kidney transplant patients.

Seventy out of 84 patients in our study tested positive when SARS-CoV-2 testing was repeated at mean of 17.2 days. The mean time to achieve negative PCR was 31.5 (±16.2) days. In a study of 40 KTRs hospitalized for COVID-19, one-quarter of their patients were shedding the virus at 30 days at a median follow-up of 53 days [30]. Another study, of 10 KTRs, found the mean duration of viral shedding was 28.4 (±9.3) days as compared to 12.2 (±4.6) days in their family members [31]. Previous studies involving renal transplant patients showed prolonged shedding of other respiratory viruses, which ranged from 6 to 44 days [32]. The duration of viral shedding does not necessarily correlate with infectivity. Current data indicates that risk of infection decreased to zero after 10 days of symptoms in mild to moderate cases and after about 15–20 days in immunocompromised or critically ill patients [33]. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommends 20 days of isolation from symptom onset for immunocompromised patients or those with critical illnesses [34]. This results in decreasing the quarantine period, particularly for asymptomatic patients and improves overall patient care.

The utility of measuring antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 remains uncertain, and its usefulness for epidemiological and infection control purposes is yet to be determined. Antibody tests were carried out in 84 of our patients, of whom 83% had evidence of humoral response. Similarly, a study of 40 KTRs by Benotmane and colleagues found that 90% had positive antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 [30]. Another study of 18 KTRs at Mount Sinai Hospitals, 16 patients showed positive anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgM or IgG titers [35]. Together, these initial results indicate that immunocompromised kidney transplant patients seem to have an excellent humoral response to SARS-CoV-2. It remains to be seen, however, if KTRs will show a similar response to any of the current COVID-19 vaccines.

Limitations of this work include its retrospective methodology, small number of patients in some of the participating centers, and short median follow-up time, in addition to the complexity incurred by the evolving clinical evidence at the time of the study.

Conclusions

Our study showed that SARS-CoV-2 infection remains a serious infection with significant mortality. A significant proportion of KTRs with SARS-CoV-2 infections do not require hospital admission and can be managed using a telemedicine clinic. Moving forward, transplant health care providers should focus on adopting telehealth technology and infrastructure to provide the best care for their high-risk patients. Most kidney transplant patients seem to mount an antibody response following SARS-CoV-2 infection, and it remains to be seen if they will have a similar response to the upcoming vaccines. Until results of further research on SARS-CoV-2 infection in transplant patients are available, lowering the burden of immunosuppression remains its cornerstone, with other lines of management continuing to extrapolate from that in the general population.

Abbreviations

- AKI

acute kidney injury

- COVID-19

coronavirus disease 19

- ICU

Intensive Care Unit

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

- IgM

immunoglobulin M

- IS

immunosuppression

- KTRs

kidney transplant recipients

- MMF

mycophenolate mofetil

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- SA

Saudi Arabia

- SARS-CoV-2

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None.

Source of support: Departmental sources

References

- 1.Center JHUCR. COVID-19 Dashboard. [Accessed April 22, 2021]. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html.

- 2.Caillard S, Anglicheau D, Matignon M, et al. An initial report from the French SOT COVID Registry suggests high mortality due to COVID-19 in recipients of kidney transplants. Kidney Int. 2020;98(6):1549–58. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar D. C4 article: Implications of COVID-19 in transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2021;5:1801–15. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rhee C, Kanjilal S, Baker M, Klompas M. Duration of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infectivity: When is it safe to discontinue isolation? Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(8):1467–74. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saudi MOH Coronavirus Diseases 19 (COVID-19) guidelines. [Accessed December 19, 2020]. https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/MediaCenter/Publications/Pages/covid19.aspx.

- 6.Lubetzky M, Aull MJ, Craig-Schapiro R, et al. Kidney allograft recipients, immunosuppression, and coronavirus disease-2019: A report of consecutive cases from a New York City transplant center. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35(7):1250–61. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfaa154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Concepcion BP, Forbes RC. The role of telemedicine in kidney transplantation: Opportunities and challenges. Kidney360. 2020;1(5):420–23. doi: 10.34067/KID.0000332020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China [published correction appears in Lancet. 2020 Jan 30;] Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arentz M, Yim E, Klaff L, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington State. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1612–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guan W-J, Ni Z-Y, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of Coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gleeson SE, Formica RN, Marin EP. Outpatient management of the kidney transplant recipient during the SARS-CoV-2 virus pandemic. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15(6):892–95. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04510420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.WHO Rapid Evidence Appraisal for COVID-19 Therapies (REACT) Working Group. Sterne JAC, Murthy S, et al. Association between administration of systemic corticosteroids and mortality among critically ill patients with COVID-19: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2020;324(13):1330–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phanish MK, Hull RP, Andrews PA, et al. Immunological risk stratification and tailored minimisation of immunosuppression in renal transplant recipients. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21(1):92. doi: 10.1186/s12882-020-01739-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhong Z, Zhang Q, Xia H, et al. Clinical characteristics and immunosuppressant management of coronavirus disease 2019 in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2020;20(7):1916–21. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Horby P, Mafham M, et al. Effect of hydroxychloroquine in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(21):2030–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2022926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Azithromycin in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): A randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet. 2021;397:605–12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00149-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Tocilizumab in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): Preliminary results of a randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet. 2021;397(10285):1637–45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00676-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The REMAP-CAP Investigators. Interleukin-6 receptor antagonists in critically ill patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1491–502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2100433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaptein SJ, Jacobs S, Langendries L, et al. Antiviral treatment of SARS-CoV-2-infected hamsters reveals a weak effect of favipiravir and a complete lack of effect for hydroxychloroquine. bioRxiv. 2020.06.19.159053. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Driouich J-S, Cochin M, Lingas G, et al. Favipiravir antiviral efficacy against SARS-CoV-2 in a hamster model. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):1735. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21992-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alamer A, Alrashed AA, Alfaifi M, et al. Effectiveness and safety of favipiravir compared to supportive care in moderately to critically ill COVID-19 patients: A retrospective study with propensity score matching sensitivity analysis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021 doi: 10.1080/03007995.2021.1920900. [Online ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ali T, Al-Ali A, Fajji L, et al. Coronavirus disease-19: Disease severity and outcomes of solid organ transplant recipients: Different spectrums of disease in different populations?: Disease severity and outcomes of solid organ transplant recipients different spectrum of disease in different populations? Transplantation. 2021;105(1):121–27. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000003433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bossini N, Alberici F, Delbarba E, et al. Kidney transplant patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection: The Brescia Renal COVID task force experience. Am J Transplant. 2020;20(11):3019–29. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang H, Penninger JM, Li Y, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as a SARS-CoV-2 receptor: Molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic target. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(4):586–90. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05985-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akalin E, Azzi Y, Bartash R, et al. COVID-19 and kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(25):2475–77. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2011117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cravedi P, Mothi SS, Azzi Y, et al. COVID-19 and kidney transplantation: Results from the TANGO International Transplant Consortium. Am J Transplant. 2020;20(11):3140–48. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pérez-Jacoiste Asín MA, López-Medrano F, Fernández-Ruiz M, et al. Risk factors for the development of invasive aspergillosis after kidney transplantation: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Transplant. 2021;21(2):703–16. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khatib MY, Shaik KS, Ahmed AA, et al. Tocilizumab-induced cytomegalovirus colitis in a patient with COVID-19. Clin Case Rep. 2021;9:148–52. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.3487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benotmane I, Gautier-Vargas G, Wendling M-J, et al. In-depth virological assessment of kidney transplant recipients with COVID-19. Am J Transplant. 2020;20:3162–72. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu L, Gong N, Liu B, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in immunosuppressed renal transplant recipients: A summary of 10 confirmed cases in Wuhan, China. Eur Urol. 2020;77(6):748–54. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Lima CRA, Mirandolli TB, Carneiro LC, et al. Prolonged respiratory viral shedding in transplant patients. Transpl Infect Dis. 2014;16(1):165–69. doi: 10.1111/tid.12167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singanayagam A, Patel M, Charlett A, et al. Duration of infectiousness and correlation with RT-PCR cycle threshold values in cases of COVID-19, England, January to May 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(32):2001483. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.32.2001483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duration of Isolation and Precautions for Adults with COVID-19. [Accessed December 24, 2020]. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/strategy-discontinue-isolation.html.

- 35.Hartzell S, Bin S, Benedetti C, et al. Evidence of potent humoral immune activity in COVID-19-infected kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2020;20(11):3149–61. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]