Abstract

Background:

People who have attempted suicide display suboptimal decision-making in the lab. Yet, it remains unclear whether these difficulties tie in with other detrimental outcomes in their lives besides suicidal behavior. We hypothesize that this is more likely the case for individuals who first attempted suicide earlier than later in life.

Methods:

A cross-sectional case-control study of 310 adults aged ≥ 50 years (mean: 63.9), compared early- and late-onset attempters (first attempt < 55 vs. ≥ 55 years of age) to suicide ideators, non-suicidal depressed controls and non-psychiatric healthy controls. Participants reported potentially avoidable negative decision outcomes across their lifetime, using the Decision Outcome Inventory (DOI). We employed multi-level modeling to examine group differences overall, and in three factor-analytically derived domains labeled Acting Out, Lack of Future Planning, and Hassles.

Results:

Psychopathology predicted worse decision outcomes overall, and in the more serious Acting Out and Lack of Future Planning domains, but not in Hassles. Early-onset attempters experienced more negative outcomes than other groups overall, in Lack of Future Planning, and particularly in Acting Out. Late-onset attempters were similar to depressed controls and experienced fewer Acting out outcomes than ideators.

Limitations:

The cross-sectional design precluded prospective prediction of attempts. The assessment of negative outcomes may have lacked precision due to recall bias.

Conclusions:

Whereas early-onset suicidal behavior is likely the manifestation of long-lasting decision-making deficits in several serious aspects of life, late-onset cases appear to function similarly to non-suicidal depressed adults, suggesting that their attempt originates from a more isolated crisis.

Keywords: old age, suicidal behavior, suicidal ideation, life outcomes, decision-making, externalizing

Introduction

Suicide can be seen as an outcome of learning and decision-making deficits that can be captured experimentally, such as in tasks that involve escaping an aversive stimulus or choosing risky vs. safe options (Millner et al., 2019; Richard-Devantoy et al., 2013). This approach has improved our understanding of suicide in older adults, an age group with especially high suicide rates in Western countries (WHO Mental Health, 2016) and demonstrating substantial complexity in the characterization of at-risk individuals (Szanto et al., 2020, 2018). In the lab, older suicide attempters have been found to problem-solve in suboptimal ways when facing difficult or uncertain situations (Dombrovski et al., 2019; McGirr et al., 2012; Szanto et al., 2015). However, hypothetical decision-making tasks tend to present potentially unrealistic decisions that may not reliably capture decision-making deficits that occur in real life (Klein, 1999). Additionally, it remains unclear to what extent suicide in late life is only the last in a chain of poor decisions with potentially catastrophic consequences, or the product of one isolated crisis.

Younger suicide victims are more likely than older suicide victims to have maladaptive personality traits (May et al., 2012; Szücs et al., 2018) that have been linked to controllable negative life events (Heikkinen et al., 1997). In contrast, death by suicide in older adults tends to be preceded by interpersonal, financial, and health-related stressful life events up to two years before the suicide itself (Rubenowitz et al., 2001). Consistently, a case-control psychological autopsy study linked late-life suicide to isolated problems typical of old age, such as bereavement, retirement, and financial/housing issues (Harwood et al., 2006), suggesting that in older suicide victims, suicidal crises tend to arise in response to relatively recent negative life events, including controllable interpersonal problems and, for some, uncontrollable experiences such as bereavement. Moreover, late-onset attempters1 (i.e., older adults who first attempt suicide in late life and survived their attempt) possess less pathological personality traits and carry out more medically serious attempts than those who have made attempts prior to old age (Szücs et al., 2020).

Older adults whose first attempt occurred before old age and who are still suicidal into late life (early-onset attempters) resemble younger attempters by displaying the same maladaptive personality profile and having a higher number of lifetime suicide attempts (Szücs et al., 2020). This is consistent with the finding that younger suicide victims tend to make multiple attempts characterized by lower medical lethality (Conwell et al., 1998; De Leo et al., 2001; McHugh and Goodell, 1971). In contrast, older suicide attempters are more likely to die as a result of their first attempt (Paraschakis et al., 2012), which often occurs without displaying signs of increased mental suffering or contacting mental health services (Waern et al., 1999; Lawrence et al., 2000; Ho et al., 2014). Therefore, late-onset attempters can be considered the closest in-vivo proxy to older suicide victims, given older suicide victims’ tendency to be first-time attempters (Paraschakis et al., 2012).

This study seeks to investigate whether early-onset attempters are more likely to report controllable negative life events than late-onset attempters, and respectively, individuals who report suicidal ideation, depression, or the absence of any psychopathology. The first comparison is important to examine whether early-onset suicidal behavior is more strongly associated with controllable negative life events than late-onset suicidal behavior. The subsequent comparisons are needed to situate our findings in the general geriatric population, given the well-established correlates of mental illness, and in particular the association between depression on decision-making difficulties (Gibbs et al., 2009). To make these comparisons, we employed the Decision Outcome Inventory (DOI), a self-report questionnaire focusing on real-life problems shown to be associated with decision-making competence, even after accounting for socio-economic status (Bruine de Bruin et al., 2007). The DOI covers a wide range in severity, from serious problems (e.g., going to jail) to minor ones (e.g., getting blisters from sunburn), making it well-suited to assess the extent of consequences of poor decision-making in real life.

We further tested whether domains of negative decision outcomes would be specifically associated with early- and/or with late-onset suicidal behavior. Previous studies have analyzed total DOI scores or item scores (Bruine de Bruin et al., 2007, 2016; Dewberry et al., 2013; Geisler and Allwood, 2015; Juanchich et al., 2016; Parker et al., 2015) but have not yet examined the DOI’s latent factor structure. Further, since the scale was originally developed to sample negative decision outcomes across multiple domains, such as medical, legal, financial, and interpersonal (Bruine de Bruin et al., 2007; Parker et al., 2015), we chose to delineate outcome domains using exploratory factor analysis and test for domain-wise differences between study groups.

We hypothesized that: (H1) early-onset attempters would demonstrate more negative life events than late-onset attempters and non-suicidal groups overall, whereas late-onset attempters would remain similar to depressed controls with no suicidal history; (H2) higher levels of negative decision outcomes in early-onset attempters would be specifically driven by domains suggestive of serious decision-making deficits, with a stronger potential to lead to far-reaching and more severe real-life consequences.

Methods

Sample

Three hundred and ten participants completed the assessments of interest (see Measures) as part of a larger study with the Longitudinal Research Program for Late Life Suicide (Szanto et al., 2015). Study procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board (IRB0407166), and all participants provided written informed consent. Psychiatric patients were recruited from inpatient psychiatric units, outpatient clinics, and the community, while non-psychiatric controls were exclusively recruited from the community. All participants were at least 50 years old when entering our study (mean, SD: 63.9 +/− 8.5 years, range: 50 – 94 years). They underwent clinical diagnostic interviewing to assess current and lifetime history of psychiatric illness using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID; First et al., 1995). Diagnoses were verified by study psychiatrists at monthly consensus review meetings. Individuals with a history of neurological disorder, delirium, psychosis, mania, or dementia were excluded from participation in the study. Additional exclusion criteria included cognitive deficits as assessed by a score <24 on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein et al., 1975) or moderate to severe impairment on the Dementia Rating Scale (DRS; Mattis, 1988), as well as active withdrawal from alcohol or other substances, or ECT treatment within the past 6 months.

Participants were categorized into five groups: early-onset suicide attempters (N=51), late-onset suicide attempters (N=52), suicide ideators (N=69), non-suicidal depressed controls (N=76) and non-psychiatric healthy controls (N=66). See Table 1 for a summary of each groups’ selection criteria.

Table 1.

Study groups: inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Study groups | Current depression | Suicidal behavior | Suicidal ideation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Late-onset attempters | Yes | First suicide attempt at age 55 or later | Either severe suicidal ideation or suicidal behavior* within the past month |

| Early-onset attempters | Yes | At least one suicide attempt before the age of 55 | |

| Ideators | Yes | No lifetime history of suicidal behavior | Severe suicidal ideation* within the past month |

| Depressed controls | Yes | No lifetime history of suicidal ideation or behavior | None |

| Healthy controls | No life-time history of depression |

Note: Current depression reflected scores of ≥14 on the HRSD, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, as administered at the time of enrollment;

Severe suicidal ideation is defined as the desire and plan to make a suicide attempt. Attempters whose suicidal behavior took place earlier than during the last month had to meet current, severe suicidal ideation criteria (all of the attempters were in a current suicidal crisis).

Suicide attempters were included in the study if they had either carried out an attempt (a self-injurious act with an intent to die) within a month of study enrollment or if they reported an earlier attempt with current serious suicidal ideation (a desire and concrete plan to attempt suicide). Suicide attempters were dichotomized based on a median split of age at first attempt: early-onset attempters had their first lifetime suicide attempt occur before the age of 55, whereas late-onset attempters had their first attempt at the age of 55 or later. This dichotomization has been used previously (Kenneally et al., 2019; Szücs et al., 2020). When plotting age of onset against total DOI scores in a sensitivity analysis, we found that a change in negative outcome rates occurred around 55 years of age at first attempt (see Supplement SF1). Suicide ideators had no lifetime history of suicide attempts but did endorse active suicidal ideation on the Beck Scale of Suicidal Ideation (Beck et al., 1979) currently or within a month of study enrollment. The ideation had to be severe enough to necessitate either psychiatric hospitalization or outpatient treatment. Non-suicidal depressed controls had no lifetime history of self-injurious behavior, suicidal ideation, or suicide attempts. All of the groups had a diagnosis of unipolar depression without psychosis as rated on the SCID or by a score of 14 or higher on the 17-Item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD; Hamilton, 1960). Non-psychiatric healthy controls had no lifetime history of psychiatric or substance use disorders, as determined by the SCID, as well as no lifetime history of suicidal ideation or behavior.

Measures

Decision outcome inventory (DOI; Bruine de Bruin et al., 2007; Parker et al., 2015)—

The DOI is a self-report measure which assesses negative life outcomes that are presumed to be controllable because they are correlated with decision-making competence, even after accounting for socio-economic status (Bruine de Bruin et al., 2007). Scoring followed the scale’s original guidelines: for each negative outcome, participants are first asked whether they have ever had a certain life experience that provided the opportunity for a decision (“A” item; e.g., Have you been responsible for a mortgage or loan?), then asked to report whether or not they ever encountered specific negative outcomes related to that decision (“B to F” items; e.g., Have you had a mortgage or loan foreclosed?). Among participants who reported ever having had the opportunity to make a specific decision, a code of “1” was assigned if they had a negative outcome, and “0” if they had no negative outcome. If participants have never encountered the initial situation, all follow-up questions testing related negative outcomes were marked as “not applicable” (NA). Thus, the total DOI score reflects the number of negative outcomes that participants ever experienced, among all of the negative outcomes they had the opportunity to experience2.

To make the decision outcomes more appropriate to our older sample spanning a wide age range (50 – 94 years), five “outcome” items (e.g., dropping out of school, experiencing unplanned pregnancy), were removed. They were replaced with five new “outcome” items relevant to later life: one financial and three medical problems tailored to later life (Cooper et al., 1982; Lue et al., 2010; Nakanishi et al., 1995), and one item reflecting careless sexual behavior unrelated to the accessibility/efficiency of birth control at the time (Watkins, 1998). Our final measure consisted of 41 items, including 36 original items and 5 new items. See Table 2 for added and excluded items and Supplemental Table ST1 for a full list of items on the final scale.

Table 2.

Added and removed items in the adapted DOI scale

| Items | Rationale | |

|---|---|---|

| Items added | ||

| 23C | Had sex with someone you met that day? | Replacement of former item 25C measuring careless sexual behavior |

| 31 | Drawn on your retirement savings before the age of 59 ½? | Replacement of former item 20B measuring suboptimal management of finances |

| 32 | Stopped taking your prescribed medication without talking to your doctor? | Replacements of former items 33 and 34 measuring suboptimal management of own health |

| 33 | Skipped medical appointments without rescheduling? | |

| 34 | Were admitted to a hospital? | |

| Items removed | ||

| 5A | Been enrolled in any kind of school | Too distant outcome in time |

| 5B | Been suspended from school for at least one day for any reason | |

| 20A | Invested in the stock market | Change in the value of money over the decades |

| 20B | Lost more than $1000 on a stock-market investment | |

| 25C | Had an unplanned pregnancy (or got someone pregnant, unplanned) | Change in the accessibility and efficiency of birth control over the decades |

| 33 | Been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes | More frequent in older age and often unrelated to health management |

| 34 | Broke a bone because you fell, slipped, or misstepped | |

Other clinical and cognitive characterization:

Suicide attempt history was assessed by trained clinicians and verified using participants’ self-reports, medical records, and corroboration from family and friends when available. Unverifiable or discrepant information led to exclusion from the main study (1.7%).

Beck Lethality Scale (BLS; Beck et al., 1975)—

Each attempter’s most recent and most lethal suicide attempts were characterized with the BLS, which measured potential lethality of an attempt based on the severity of its medical consequences, ranging from 0 (none or minimal) to 8 (attempt resulting in death). For example, a rating of 4 is associated with any suicide attempt that resulted in injury sufficient for hospitalization. If a participant had multiple suicide attempts, the attempt with the highest lethality rating was used in our analysis.

Scale of Suicidal Intent (SIS; Beck et al., 1974)—

Attempts were additionally assessed with the SIS, which measured participants’ intent to complete the suicidal act as well as seriousness and degree of planning of the attempt. For instance, the degree of premeditation was characterized as follows: suicide contemplated not at all, or for more or less than 3 hours prior to acting. The maximum possible suicide intent score is 30.

Scale of Suicidal Ideation (SSI; Beck et al., 1979)—

The worst lifetime and current suicidal ideation severity were separately measured with the SSI. This scale assessed frequency and duration of suicidal thoughts, as well as deterrents to attempting suicide. Participants can receive a rating of 0 to 2 on 19 individual items, for a possible score range of 0 to 38 total points.

Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression - 17 Item (HRSD; Hamilton, 1960)—

The HRSD was used to measure depression severity, with higher scores indicating increased depression severity. Scores in the range of 8–16 indicate mild depression, scores in the range of 17–23 indicate moderate depression, and scores ≥24 indicate severe depression (Zimmerman et al., 2013). The suicidal ideation item on the HRSD was excluded from analysis to avoid overinflating suicidal participants’ total scores.

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders IV (SCID; First et al., 1995)—

Participants were assessed for current or lifetime presence of Axis I diagnoses including mood, substance use, and anxiety disorders, all coded as binary variables.

Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein et al., 1975) and Dementia Rating Scale (DRS; Mattis, 1988) —

Cognitive ability was characterized using the MMSE and the DRS. On the MMSE, the maximum possible score is 30, and a minimum score of 24 was required for study enrollment. The DRS has a maximum possible score of 144, and a rating of 116 or lower is suggestive of dementia (Mattis, 1988).

Personality Assessment Inventory - Borderline subscale (PAI-BOR; Morey, 2014)—

We used the PAI-BOR, a self-report questionnaire, to evaluate borderline personality traits. It includes 24 questions about negative relationships, engagement in self-harm, affective instability and identity problems and assesses traits continuously, as items are scored on a four-point scale from 0 to 3. Possible scores range from 0 to 72. This self-report was only collected in 210 participants (68% of the total sample), as the scale was introduced later than the DOI in the assessment pool of the larger study.

Analytic Strategy

All analyses were performed in R, version 3.6.1. DOI Item 1 (returning a movie without having watched it) was removed prior to all analyses due to a low rate of experiencing the initial situation of ever renting a movie (8.60%). We tested (H1) group differences on the overall DOI, and (H2) in specific domains.

(H1) To determine overall group differences on DOI scores, we ran a negative binomial mixed-effects model predicting item scores (lme4 package, Bates et al., 2007), entering participant as a random effect, study group as the independent variable and gender and education as control variables (Supplemental Table ST4). In case of a significant main effect of study group, post-hoc pairwise comparisons were performed (emmeans package, Lenth, 2020; Supplemental Table ST5). As a first sensitivity analysis (Supplemental Table ST6), we tested group differences in a simple linear model predicting weighted total scores, using the weights indicated in the initial publication on the DOI (Bruine de Bruin et al., 2007). Since no weights were available for the added items, they had to be excluded from this analysis. As additional sensitivity analyses (Supplemental Tables ST7 to ST10), we tested our main results’ robustness in a binomial mixed-effects model without covariates, and in models with one additional covariate (in addition to gender and education) to augment the main analysis; namely household income, cognitive ability measured with DRS total scores, and lifetime history of drug or alcohol addiction measured with the SCID (healthy controls were excluded from this last analysis). We did not control for age because of the age-dependence of our dependent variable.

(H2) To examine the latent structure of the DOI, we performed an iterative exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with weighted least squares factoring and direct oblimin rotation (psych package, Revelle & Revelle, 2015) applied to the 42 DOI items (after exclusion of Item 1). We followed Velicer’s MAP test (Velicer, 1976), which suggested a three-factor structure. To reduce scale collinearity and improve specificity, items with a primary loading < |.30| or a cross-loading difference < |.10| on any secondary factor were removed, and the EFA was rerun. We repeated this procedure until all items met the established thresholds, at which point they were retained for each factor (Supplemental Table ST2). Note that when the factor analysis was run on the items from the original DOI only, the same factors were obtained (Supplemental Table ST3). The final three-factor solution comprised 28 items, including 24 of the original items and 4 of the new items (Supplemental Table ST2). Based on their content, we labeled the factors Acting Out, Lack of Future Planning and Hassles (Supplemental Table ST2). The Acting Out domain mostly encompassed potentially severe legal or interpersonal negative outcomes that may be (but are not necessarily) the consequence of externalizing behavior (e.g., “Been in a jail cell overnight for any reason”). The Lack of Future Planning domain contained negative outcomes mostly related to finances and health that could result from poor planning and management of one’s assets (e.g., “Skipped medical appointments”). The Hassles domain grouped trivial negative outcomes reflecting minor everyday problems (e.g., “Locked keys in car”). See Supplemental Table ST2 for full list of items in each factor.

In order to test domain-specific group differences in early and late-onset attempters (H2), we added domain as an interaction term to the binomial multilevel model predicting DOI item scores used for H1, but this time, predicting only the DOI items retained in the factor analysis (Supplemental Table ST11). In case of a significant study group*domain interaction, post-hoc pairwise comparisons (emmeans package; Lenth, 2020) were tested between study groups on each domain (Supplemental Table ST12). We performed the same sensitivity analyses, as with our main model testing H1 (Supplemental Tables ST15 to ST18). We additionally verified our findings’ robustness in an alternative model where DOI items excluded by the factor analysis were added back in, based on each item’s meaning (Supplemental Tables ST13 to ST14).

Results

Sample characteristics

Sample characteristics are presented in Table 3. Participants’ mean age was 63.9 years, with early-onset attempters being younger than the other groups. Groups further differed on female:male ratio and lifetime substance abuse, with no significant pairwise differences between any groups. Healthy controls had higher levels of education than late-onset attempters, as well as higher household income and higher scores on the DRS than all clinical groups. Depression severity was lower in non-suicidal depressed controls than in the three suicidal groups. All depressed groups had more borderline traits than healthy controls. Additionally, depressed controls had less borderline traits than early-onset attempters, and late-onset attempters had less borderline traits than both ideators and early-onset attempters. Current suicidal ideation scores were lower in suicide ideators than in the attempter groups, and lower in early-onset attempters than late-onset attempters. Further, both attempter groups displayed more severe lifetime suicidal ideation than the ideator group. Higher levels of intent and planning characterized the suicidal behavior of late-onset attempters compared to their early-onset counterparts, and early-onset attempters made more lifetime suicide attempts than the late-onset attempters.

Table 3.

Demographic Characteristics by Group

| Healthy Control (N=66) | Depressed Control (N=74) | Ideator (N=69) | Early Onset Attempter (N=49) | Late Onset Attempter (N=52) | p-value | post-hocs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGE | 65.80 (9.92) | 65.47 (8.26) | 62.41 (8.12) | 59.10 (5.61) | 65.90 (7.67) | <0.001 | EA<HC,DC, LA |

| SEX (% MALE) | 26 (39.4) | 37 (50.0) | 40 (58.0) | 17 (34.7) | 32 (61.5) | 0.018 | No pairwise differences |

| RACE (%) | 0.570 | ||||||

| AFRICAN AMERICAN | 9 (13.6) | 15 (20.3) | 11 (15.9) | 9 (18.4) | 3 (5.8) | ||

| ASIAN | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.9) | ||

| MORE THAN ONE RACE | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.9) | ||

| WHITE | 57 (86.4) | 58 (78.4) | 56 (81.2) | 40 (81.6) | 47 (90.4) | ||

| EDUCATION | 15.65 (2.60) | 14.69 (2.53) | 14.90 (2.47) | 14.45 (3.17) | 13.62 (2.90) | 0.002 | HC>LA |

| HOUSEHOLD INCOME | 62138.46 (30923.86) | 37028.57 (28914.78) | 33909.09 (29324.70) | 33693.88 (30906.75) | 34088.24 (25859.76) | <0.001 | HC>DC,SI,EA,LA |

| BORDERLINE TRAITS1 | 8.22 (4.35) | 25.16(10.83) | 31.52 (12.72) | 33.39 (12.30) | 21.15 (13.30) | <0.001 | HC<DC,SI,EA,LA DC< EA LA<SI,EA |

| LIFETIME SUBSTANCE ABUSE (%) | - | 24 (32%) | 33 (49%) | 28 (57%) | 22 (43%) | 0.046 | No pairwise differences |

| DEMENTIA RATING SCALE TOTAL SCORE2 | 138.39 (3.10) | 135.28 (5.34) | 135.00 (6.86) | 135.21 (4.58) | 132.98 (6.38) | <0.001 | HC>DC,SI,EA,LA |

| DEPRESSION SEVERITY3 | - | 16.58 (3.80) | 19.80 (5.60) | 21.12 (5.54) | 20.62 (6.38) | <0.001 | DC<SI,EA,LA |

| CURRENT SUICIDAL IDEATION4 | - | - | 15.30 (6.47) | 19.90 (7.87) | 23.77 (7.52) | <0.001 | SI<EA,LA EA<LA |

| WORST LIFETIME SUICIDAL IDEATION4 | - | - | 18.72 (7.12) | 25.35 (6.03) | 25.92 (5.98) | <0.001 | SI<EA,LA |

| HIGHEST LETHALITY SUICIDE ATTEMPT5 | - | - | - | 3.27 (2.12) | 4.06 (2.05) | 0.059 | |

| WORST LIFETIME INTENT - PLANNING SUBSCORE6 | - | - | - | 7.35 (2.49) | 8.88 (3.47) | 0.014 | LA>EA |

| WORST LIFETIME INTENT TOTAL SCORE7 | - | - | - | 16.88 (5.21) | 20.40 (4.62) | 0.001 | LA>EA |

| AGE OF FIRST ATTEMPT | - | - | - | 32.57 (15.50) | 64.85 (8.24) | <0.001 | LA>EA |

| LIFETIME NUMBER OF SUICIDE ATTEMPTS | - | - | - | 3.47 (3.14) | 1.54 (0.96) | <0.001 | EA>LA |

HC, healthy controls; DC, depressed controls; SI, suicide ideators; EA, early-onset attempters; LA, late-onset attempters;

Personality Assessment Inventory – Borderline Subscale;

Mattis Dementia Rating Scale;

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale;

Beck Scale of Suicidal Ideation;

Beck Suicide Lethality Scale;

Beck Suicide Intent Scale – Planning Subscale;

Beck Suicide Intent Scale

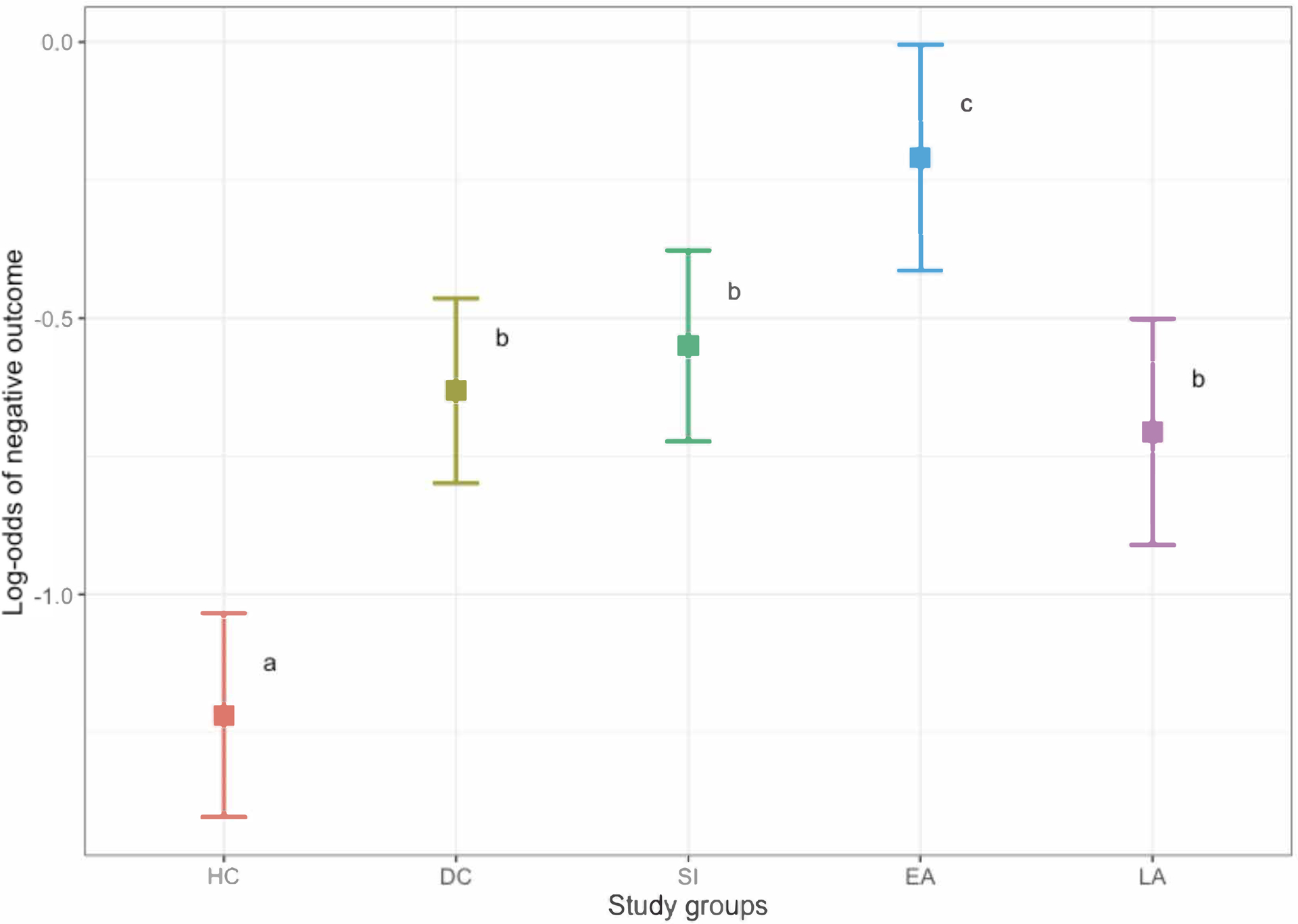

(H1) Effects of age of onset of suicidal behavior on decision outcomes

Our binomial multi-level model yielded a main effect of group (χ24 = 56.29, p < .001; Figure 1, Supplemental Tables ST4 and ST5). Consistent with H1, early-onset attempters experienced more negative decision outcomes than all other groups, whereas late-onset attempters were similar to other clinical groups. All clinical groups experienced more negative outcomes than healthy controls.

Figure 1. Negative decision outcomes across study groups.

Lower scores (least square means) indicate fewer negative outcomes. Legend: HC, healthy controls; DC, depressed controls; SI, ideators; EA, early-onset attempters; LA, late-onset attempters. Groups sharing a letter are not significantly different. All models controlled for sex and education. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

All of these findings remained in the sensitivity analysis with no covariates as well as in those covarying for cognitive ability, income and lifetime substance use disorders. See Supplemental Tables ST7 to ST10 for all sensitivity analyses.

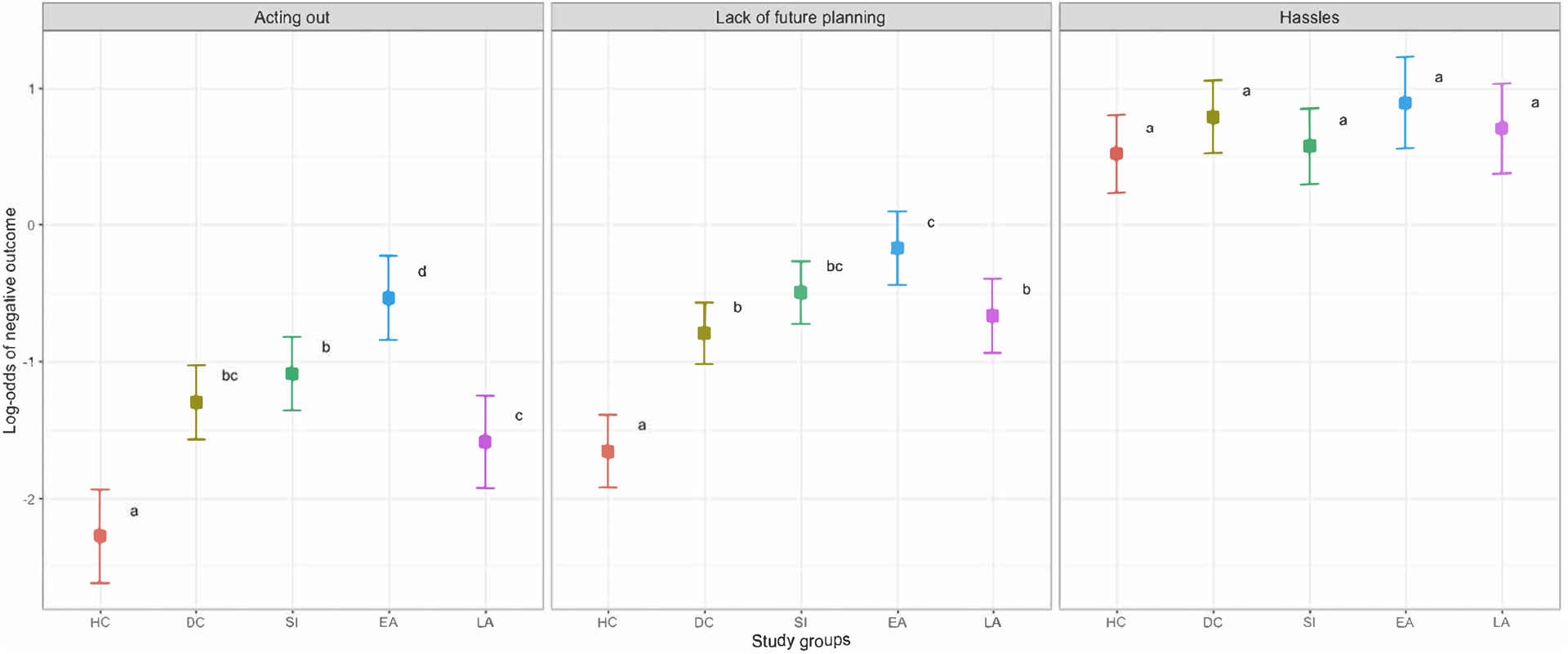

(H2) Effects of age of onset of suicidal behavior by decision outcome domain

A significant group*domain interaction (χ28 = 52.62, p < .001; Figure 2, Supplemental Tables ST11 and ST12) indicated that the group differences varied across domains.

Figure 2. Negative decision outcomes across domains and study groups.

Lower scores (least square means) indicate fewer negative outcomes. Legend: HC, healthy controls; DC, depressed controls; SI, ideators; EA, early-onset attempters; LA, late-onset attempters. Groups sharing a letter are not significantly different. All models controlled for sex and education. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Early-onset attempters reported more Acting Out outcomes than all other groups. Late-onset attempters reported less Acting Out outcomes than other suicidal groups, including ideators. Outcomes in the Acting Out domain were less frequently reported by healthy controls than by clinical groups. All findings on the Acting Out domain remained in sensitivity analyses (testing group differences respectively without covariates, and with household income, cognitive ability and substance use disorders; see Supplemental Tables ST15 to ST18).

In the Lack of Future Planning domain, early-onset attempters reported more negative outcomes than late-onset attempters and depressed controls. In addition, all clinical groups reported more negative outcomes than healthy controls. These findings remained in the model with no covariates and were robust to covarying for income and cognitive ability, but the early-onset vs. late-onset difference disappeared in the sensitivity analysis covarying for substance use disorders (see Supplemental Tables ST15 to ST18).

There were no group differences on the Hassles domain.

Discussion

Our study investigated real-life negative decision outcomes in older adults whose suicidal behavior first manifested in old age vs. earlier in life. We found that those who first attempted suicide early in life experienced significantly more negative decision outcomes than the comparison groups, and most importantly, than those whose first attempt occurred in late life (Figure 1). These group differences were prominent in the Acting Out and, to a lesser degree, in the Lack of Future Planning domains, but were not present in the Hassles domain (Figure 2).

Our findings add to the growing evidence of psychological heterogeneity in suicidal behavior across the life cycle. Those who first attempt suicide at a younger age have already been found to score higher on maladaptive personality trait measures (Szücs et al., 2020) and have been more frequently exposed to suicidal behavior in their families and friends than their late-onset counterparts (Kenneally et al., 2019). Our finding of more negative decision outcomes in early-onset suicidal behavior suggests that people who attempt suicide early on and are still suicidal into old age may have a pattern of suboptimal decision-making, which was expressed in the reporting of more adverse life events. In turn, these life events are likely related to both higher levels of psychological vulnerability and a more precarious social environment, possibly contributing to the early-onset suicidal behavior in these individuals.

Additionally, we found no significant difference in either overall or domain-specific DOI scores between late-onset attempters and depressed controls, suggesting that these groups have experienced similar controllable negative outcomes. These findings suggest that late-onset suicidal behavior may occur as the result of an isolated, often uncontrollable life crisis, perhaps not captured on the DOI, such as bereavement or retirement (Harwood et al., 2006), cognitive deficits (Gujral et al., 2016), or threats to autonomy or social status (Alessi et al., 2018). However, little is known about the underlying vulnerabilities of those who become suicidal versus those who do not, when facing a specific negative outcome late in life. Besides cognitive biases resulting from depression or cognitive decline, specific personality traits related to an increased need for control may have played a role (Conwell et al., 1998; Kjølseth et al., 2009; Szücs et al., 2020).

Several of our additional results corroborate that early-onset attempter’s suicide risk profile is similar to that of younger attempters. The same pattern of differences emerged between early- and late-onset attempters in both the Acting Out and Lack of Future Planning domains, suggesting that early-onset attempters experience relatively more difficulties controlling their behavior and planning ahead. These results are consistent with prior research suggesting that difficulties in conceiving and following long-term goals (i.e., low future orientation) undermines economic decision-making (Balliet et al., 2005; Howlett et al., 2008) and is linked to potentially detrimental problem behaviors and increased suicide risk in young adulthood (Chang et al., 2017; Chen and Vazsonyi, 2011). Similarly, prior research has linked suicidal behavior in young and middle age to the impulsivity facets Lack of Premeditation, i.e., difficulties comprehending the future consequences of one’s actions, and Urgency, i.e., the propensity to act rashly in response to strong emotions (Klonsky and May, 2010). Further, lack of future planning and acting out are core features of personality pathology, which was also more prominent in early- than in late-onset attempters in our sample when measured by borderline traits (Table 3).

Consistent with H2, the decision outcomes in the Hassles domain did not differentiate any of the groups, suggesting that trivial life problems are common to everyone. This finding aligns well with the original scale’s traditional scoring, which gave relatively less weight to the relatively less severe items (Bruine de Bruin et al., 2007). Prior research found that such minor decision-making failures could arise from a diverse set of causes, ranging from psychopathology and cognitive deficits to clumsiness, daytime sleepiness or even boredom (Wagle et al., 1999; Wallace et al., 2003, p. 200).

Strengths and Limitations

The use of several control groups, and the contrast between early- and late-onset suicidal behavior enabled a greater degree of psychological specificity than would have been possible with more simple designs. We adapted the DOI scale to a geriatric population and derived factor-analytic domains, demonstrating their convergent and divergent validity.

This study had several limitations. First, as the DOI is a self-report measure, it relies on the ability to recall events that have happened over the course of one’s life. While our clinical groups did not differ on cognitive measures, it is possible that negative decision outcomes have been over- or underreported due to memory deficits associated with normal aging and depression (Antikainen et al., 2001). Although less severe items were included in the DOI in part to mitigate the effects of social desirability bias, as with any self-report, participants may have still withheld the report of certain negative outcomes to avoid making a bad impression. Our analyses did not allow us to determine causality, therefore decision-making outcomes may both affect and be affected by group status. In the absence of prospective assessments, we cannot make inferences about a direct contribution of poor decision outcomes to a suicidal crisis. Finally, selection and/or survival biases may have affected the participation of those elderly with the worst decision outcomes.

Conclusions

Overall, our study helps parse the heterogeneity of suicidal behavior based on its age of onset. On the DOI, participants with early-onset suicidal behavior reported more negative outcomes relating to real-life decisions. This may relate to the tendency of early-onset or younger suicide attempters to act impulsively, without considering long-term consequences of their actions (Klonsky and May, 2010; McHugh et al., 2019). They are likely to benefit from dialectical behavioral therapy and mindfulness-based approaches designed specifically to treat suicidal behavior (Mark et al., 2004), as several of these techniques aim to improve decision-making competence by increasing future orientation (Yu et al., 2018).

At the same time, clinicians need to be aware of the other, late-onset group, capable of serious suicidal behavior in the absence of any global pattern of suboptimal decision-making, but which may emerge at times of change or crisis related to late-life, possibly by decreasing positive expectations of one’s future (Hirsch et al., 2007). Despite evidence of learning and choice process deficits in older attempters (Szanto et al., 2018), our understanding of both risk markers and mechanisms of late-life suicidal behavior remains inadequate, and more work is needed to understand how cognitive aging, individual decision styles, and the challenges of late life interact to give rise to these cases of suicidal behavior. Only by increasing our knowledge of the interplay of these factors will it be possible to devise impactful screening and treatment approaches.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Maria Alessi, Amanda Collier, Laura Kenneally, Melissa Milbert, and Kelley Wood for data collection, and Joshua Feldmiller for assistance in pulling the data.

Footnotes

We would here like to highlight an important distinction in the use of terms “attempter” and “ideator” found in this manuscript. Individuals who display suicidal thoughts or behavior should not be labeled as such, and we will be using these terms in reference to the clinical phenomena and its characteristics, as opposed to any one individual person.

In previous research, total DOI scores weighted negative outcomes by their relative seriousness (Bruine de Bruin et al., 2007). However, weighted and unweighted total DOI scores tend to be highly correlated and yield similar results (Bruine de Bruin et al., 2007). Because Bruine de Bruin et al.’s (Bruine de Bruin et al., 2007) previous weights were not available for all of our items after adapting the scale to our geriatric population, we used unweighted scores (see “Analytic Strategy”).

References

- Alessi M, Szanto K, Dombrovski A, 2018. Motivations for attempting suicide in mid-and late-life. Int. Psychogeriatr 1–13. 10.1017/S1041610218000571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antikainen R, Hänninen T, Honkalampi K, Hintikka J, Koivumaa-Honkanen H, Tanskanen A, Viinamäki H, 2001. Mood improvement reduces memory complaints in depressed patients. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci 251, 6–11. 10.1007/s004060170060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balliet DP, Joireman J, Sprott D, Spangenberg E, 2005. Ego Depletion, Future Orientation, and Preference for Certain Vs. Probabilistic Outcomes.

- Bates D, Sarkar D, Bates MD, Matrix L, 2007. The lme4 package. R Package Version 2.

- Beck AT, Beck R, Kovacs M, 1975. Classification of suicidal behaviors: I. Quantifying intent and medical lethality. Am. J. Psychiatry 132, 285–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A, 1979. Assessment of suicidal intention: the Scale for Suicide Ideation. J Consult Clin Psychol 47, 343–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Shuyler D, Herman I, 1974. Development of suicidal intent scales, in: Beck AT, Resnik HLP, Lettieri DJ (Eds.), The Prediction of Suicide. Charles Press, Bowie, MD, pp. 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bruine de Bruin W, Dombrovski AY, Parker AM, Szanto K, 2016. Late-life Depression, Suicidal Ideation, and Attempted Suicide: The Role of Individual Differences in Maximizing, Regret, and Negative Decision Outcomes. J. Behav. Decis. Mak 29, 363–371. 10.1002/bdm.1882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruine de Bruin W, Parker AM, Fischhoff B, 2007. Individual differences in adult decision-making competence. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol 92, 938–956. 10.1037/0022-3514.92.5.938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang EC, Chang OD, Martos T, Sallay V, 2017. Future orientation and suicide risk in Hungarian college students: Burdensomeness and belongingness as mediators. Death Stud. 41, 284–290. 10.1080/07481187.2016.1270371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Vazsonyi AT, 2011. Future orientation, impulsivity, and problem behaviors: A longitudinal moderation model. Dev. Psychol 47, 1633–1645. 10.1037/a0025327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conwell Y, Duberstein PR, Cox C, Herrmann J, Forbes N, Caine ED, 1998. Age differences in behaviors leading to completed suicide. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 6, 122–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JK, Love DW, Raffoul PR, 1982. Intentional Prescription Nonadherence (Noncompliance) by the Elderly. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc 30, 329–333. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1982.tb05623.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Leo D, Padoani W, Scocco P, Billebrahe U, Arensman E, Hjelmeland H, Crepet P, Haring P, Hawton K, Lonnqvist J, Michel K, Pommereau X, Querejeta I, Phillipe J, Salander-Renberg E, Schmidtke A, Fricke S, Weinacker B, Tamesvary B, Wasserman D, Faria S, 2001. Attempted and completed suicide in older subjects: results from the WHO/EURO multicentre study of suicidal behavior. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 16, 300–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewberry C, Juanchich M, Narendran S, 2013. Decision-making competence in everyday life: The roles of general cognitive styles, decision-making styles and personality. Personal. Individ. Differ 55, 783–788. 10.1016/j.paid.2013.06.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dombrovski AY, Hallquist MN, Brown VM, Wilson J, Szanto K, 2019. Value-Based Choice, Contingency Learning, and Suicidal Behavior in Mid- and Late-Life Depression. Biol. Psychiatry, Revisiting the Neural Circuitry of Depression 85, 506–516. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M Sr., Gibbon M, Williams JBW, 1995. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders - Patient Edition (SCID-I/P). Version 2.0.

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR, 1975. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res 12, 189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler M, Allwood CM, 2015. Competence and Quality in Real-Life Decision Making. PLoS ONE 10. 10.1371/journal.pone.0142178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs LM, Dombrovski AY, Morse J, Siegle GJ, Houck PR, Szanto K, 2009. When the solution is part of the problem: problem solving in elderly suicide attempters. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 24, 1396–1404. 10.1002/gps.2276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gujral S, Ogbagaber S, Dombrovski AY, Butters MA, Karp JF, Szanto K, 2016. Course of cognitive impairment following attempted suicide in older adults. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 31, 592–600. 10.1002/gps.4365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M, 1960. A rating scale for depression. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 23, 56–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood D, Hawton K, Hope T, Harriss L, Jacoby R, 2006. Life problems and physical illness as risk factors for suicide in older people: a descriptive and case control study. Psychol. Med 36, 1265–1274. 10.1017/S0033291706007872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikkinen ME, Henriksson MM, Isometsä ET, Marttunen MJ, & Na HM, Lönnqvist JK, 1997. Recent Life Events and Suicide in Personality Disorders: J. Nerv. Amp Ment. Dis 185, 373–381. 10.1097/00005053-199706000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch JK, Duberstein PR, Conner KR, Heisel MJ, Beckman A, Franus N, Conwell Y, 2007. Future orientation moderates the relationship between functional status and suicide ideation in depressed adults. Depress. Anxiety 24, 196–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho RCM, Ho ECL, Tai BC, Ng WY, Chia BH, 2014. Elderly Suicide With and Without a History of Suicidal Behavior: Implications for Suicide Prevention and Management. Arch. Suicide Res 18, 363–375. 10.1080/13811118.2013.826153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlett E, Kees J, Kemp E, 2008. The role of self‐regulation, future orientation, and financial knowledge in long‐term financial decisions. J. Consum. Aff 42, 223–242. [Google Scholar]

- Juanchich M, Dewberry C, Sirota M, Narendran S, 2016. Cognitive Reflection Predicts Real-Life Decision Outcomes, but Not Over and Above Personality and Decision-Making Styles. 10.1002/bdm.1875 [DOI]

- Kenneally LB, Szűcs A, Szántó K, Dombrovski AY, 2019. Familial and social transmission of suicidal behavior in older adults. J. Affect. Disord 245, 589–596. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjølseth I, Ekeberg O, Steihaug S, 2009. “Why do they become vulnerable when faced with the challenges of old age?” Elderly people who committed suicide, described by those who knew them. Int. Psychogeriatr 21, 903–912. 10.1017/S1041610209990342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein G, 1999. Sources of Power. How People make decisions. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED, May A, 2010. Rethinking impulsivity in suicide. Suicide Life. Threat. Behav 40, 612–9. 10.1521/suli.2010.40.6.612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence D, Almeida OP, Hulse GK, Jablensky AV, Holman CD, 2000. Suicide and attempted suicide among older adults in Western Australia. Psychol. Med 30, 813–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenth R, 2020. emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means.

- Lue B-H, Chen L-J, Wu S-C, 2010. Health, financial stresses, and life satisfaction affecting late-life depression among older adults: a nationwide, longitudinal survey in Taiwan. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr., Supplement Geriatric Syndrome in Taiwan 50, S34–S38. 10.1016/S0167-4943(10)70010-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark J, Williams G, Swales M, 2004. The Use of Mindfulness-Based Approaches for Suicidal Patients. Arch. Suicide Res 8, 315–329. 10.1080/13811110490476671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattis S, 1988. Dementia Rating Scale (DRS): Professional Manual, in: Psychological Assessment Resources. Odessa, FL. [Google Scholar]

- May AM, Klonsky ED, Klein DN, 2012. Predicting Future Suicide Attempts among Depressed Suicide Ideators: A 10-year Longitudinal Study. J. Psychiatr. Res 46, 946–952. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGirr A, Dombrovski AY, Butters M, Clark L, Szanto K, 2012. Deterministic learning and attempted suicide among older depressed individuals: Cognitive assessment using the Wisconsin Card Sorting Task. J. Psychiatr. Res 46, 226–232. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh CM, Chun Lee RS, Hermens DF, Corderoy A, Large M, Hickie IB, 2019. Impulsivity in the self-harm and suicidal behavior of young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res 116, 51–60. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh PR, Goodell H, 1971. Suicidal Behavior: A Distinction in Patients With Sedative Poisoning Seen in a General Hospital. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 25, 456–464. 10.1001/archpsyc.1971.01750170072011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millner AJ, den Ouden HEM, Gershman SJ, Glenn CR, Kearns JC, Bornstein AM, Marx BP, Keane TM, Nock MK, 2019. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors are associated with an increased decision-making bias for active responses to escape aversive states. J. Abnorm. Psychol 128, 106–118. 10.1037/abn0000395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey LC, 2014. The Personality Assessment Inventory., in: Personality Assessment, 2nd Ed. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, New York, NY, US, pp. 181–228. [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi N, Tatara K, Takashima Y, Fujiwara H, Takamori Y, Takabayashi H, Scott R, 1995. The association of health management with the health of elderly people. Age Ageing 24, 334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paraschakis A, Douzenis A, Michopoulos I, Christodoulou C, Vassilopoulou K, Koutsaftis F, Lykouras L, 2012. Late onset suicide: Distinction between “young-old” vs. “old-old” suicide victims. How different populations are they? Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr 54, 136–139. 10.1016/j.archger.2011.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker AM, Bruine de Bruin W, Fischhoff B, 2015. Negative decision outcomes are more common among people with lower decision-making competence: an item-level analysis of the Decision Outcome Inventory (DOI). Front. Psychol 6, 363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revelle W, Revelle MW, 2015. Package ‘psych.’ Compr. R Arch. Netw

- Richard-Devantoy S, Berlim M, Jollant F, 2013. A meta-analysis of neuropsychological markers of vulnerability to suicidal behavior in mood disorders. Psychol. Med 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenowitz E, Waern M, Wilhelmson K, Allebeck P, 2001. Life events and psychosocial factors in elderly suicides--a case-control study. Psychol. Med 31, 1193–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szanto K, Bruine de Bruin W, Parker AM, Hallquist MN, Vanyukov PM, Dombrovski AY, 2015. Decision-making competence and attempted suicide. J. Clin. Psychiatry 76, 1590–1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szanto K, Galfalvy H, Kenneally L, Almasi R, Dombrovski AY, 2020. Predictors of serious suicidal behavior in late-life depression. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2020.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szanto K, Galfalvy H, Vanyukov PM, Keilp JG, Dombrovski AY, 2018. Pathways to Late-Life Suicidal Behavior: Cluster Analysis and Predictive Validation of Suicidal Behavior in a Sample of Older Adults With Major Depression. J. Clin. Psychiatry 79. 10.4088/JCP.17m11611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szücs A, Szanto K, Aubry J-M, Dombrovski AY, 2018. Personality and Suicidal Behavior in Old Age: A Systematic Literature Review. Front. Psychiatry 9, 128. 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szücs A, Szanto K, Wright AGC, Dombrovski AY, 2020. Personality of late‐ and early‐onset elderly suicide attempters. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 35, 384–395. 10.1002/gps.5254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velicer WF, 1976. Determining the number of components from the matrix of partial correlations. Psychometrika 41, 321–327. [Google Scholar]

- Waern M, Beskow J, Runeson B, Skoog I, 1999. Suicidal feelings in the last year of life in elderly people who commit suicide. Lancet 354, 917–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagle AC, Berrios GE, Ho L, 1999. The cognitive failures questionnaire in psychiatry. Compr. Psychiatry 40, 478–484. 10.1016/S0010-440X(99)90093-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JC, Vodanovich SJ, Restino BM, 2003. Predicting cognitive failures from boredom proneness and daytime sleepiness scores: an investigation within military and undergraduate samples. Personal. Individ. Differ 34, 635–644. 10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00050-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins ES, 1998. On the pill: A social history of oral contraceptives, 1950–1970. JHU Press. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Mental Health, 2016. WHO | Suicide data [WWW Document]. WHO. URL http://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/suicideprevent/en/ (accessed 4.15.20). [Google Scholar]

- Yu E, Cheavens J, Vilhauer J, van Beek W, 2018. Future-oriented treatments for suicide: an overview of three modern approaches, in: A Positive Psychological Approach to Suicide. Springer, pp. 183–208. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman M, Martinez JH, Young D, Chelminski I, Dalrymple K, 2013. Severity classification on the Hamilton depression rating scale. J. Affect. Disord 150, 384–388. 10.1016/j.jad.2013.04.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.