Abstract

The purpose of this study was to identify changes in family conflict and abuse dynamics during COVID-19 stay-at-home orders from the perspectives of youth calling a national child abuse hotline. We analyzed text and chat transcripts from Childhelp’s National Child Abuse Hotline from May–June 2020 that were flagged as coming from a child with a COVID-19-related concern (N = 105). Thematic analysis was used to identify COVID-19 related influences of family conflict as well as how COVID-19 constraints influenced coping and survival for youth reporting distress or maltreatment to the hotline. Family conflict most commonly disclosed stemmed from parental or child mental health concerns, often manifesting in escalated child risk taking behaviors, parental substance use, and violence in the home. Conflict was also mentioned surrounding caregiver issues with child productivity while sheltering-in-place, commonly related to school or chores. Youth often voiced feeling unable to find relief from family conflict, exacerbated from physical distance from alternative social supports, technological isolation, and limited contact with typical safe places or supportive adults. To cope and survive, youth and crisis counselors found creative home-based coping skills and alternative reporting mechanisms. Understanding the unique impact of COVID-19 on youth in homes with family conflict and abuse can point to areas for intervention to ensure we are protecting the most vulnerable as many continue to shelter-in-place. In particular, this study revealed the importance of online hotlines and reporting mechanisms to allow more youth to seek out the help and professional support they need.

Keywords: COVID-19, Child maltreatment, Child abuse, Family conflict, Reporting

Introduction

As the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic spread throughout the United States, several federal and state protective measures were implemented, including mandatory stay-at-home orders that have forced children and families to shelter in place for several months. Under epidemic conditions, quarantine-related stressors including fear of infection, chronic physical and mental health needs, increased financial insecurity, and general uncertainty are shown to have significant impacts on mental health outcomes and family dynamics (Park et al., 2020 and Brooks et al., 2020), and recent research highlights increased caregiver burden and increased child-parent relationship conflict during the COVID-19 pandemic (Russell et al., 2020 and Spinelli et al., 2020). Concern regarding increased exposure to intimate partner violence, prolonged isolation from schools and other support systems, and changes in daily routines are all thought to increase the risk of family conflict, increasing risk for child maltreatment and family violence (Humphreys et al., 2020).

In addition, closures of schools and other support services have led to decreased visibility and identification of child abuse and neglect. School workers including teachers, guidance counselors, and school psychologists are mandated reporters of suspected child maltreatment, and submit over 20 percent of child maltreatment reports nationwide (Health & Human Services, 2020 and Fitzpatrick et al., 2020). In a time when increased financial, mental, and physical stress would be expected to result in an increased risk and incidence of child maltreatment (Becker-Blease et al., 2010; Griffith, 2020; Lawson et al., 2020; and Schneider et al., 2017), rates of child maltreatment reporting during spring of 2020 actually decreased, likely representing unreported allegations while schools were closed (Baron et al., 2020; Bullinger et al., 2020; and Rodriguez et al., 2020).

While recent studies have examined the effects of COVID-19 shelter-in-place orders on caregiver stress (Brooks et al., 2020; Fitzpatrick, 2020; and Patrick et al., 2020), child-parent relationships (Griffith, 2020), and risk and reporting of child abuse (Baron et al., 2020; Bullinger et al., 2020; Lawson et al., 2020; and Rodriguez et al., 2020), little is known regarding youth’s perceptions and experiences of family dynamic changes during stay-at-home orders, particularly as they relate to family conflict and violence. This study, therefore, seeks to examine real-time effects on youth experiencing distress and abuse, using a unique dataset comprised of child-initiated text and chat inquiries to a national child abuse hotline to describe the impacts of COVID-19 on family conflict and abuse dynamics. Specific aims of this study are to: 1) identify sources of family conflict during stay-at-home orders from the perspectives of youth calling a national child abuse hotline and 2) describe the impact of this conflict on youth. By understanding the family conflict and violence crises youth are seeking help for, we can better articulate gaps in care and how to improve virtual infrastructure to support those most vulnerable adverse outcomes.

Methods

The Data Source

The present study analyzed text and chat inquiries from May–June 2020 made from children and adolescents to The Childhelp National Child Abuse Hotline. This confidential hotline serves the U.S. and Canada, and is staffed 24 h a day, 7 days a week with professional crisis counselors who offer crisis intervention, information, and referrals to emergency, social service, and support resources (Childhelp, n.d.). Users access the hotline by phone, text, or online live chat. While hotline calls are not transcribed, text and chat encounter transcripts are retained for up to 60 days before auto-deletion, serving as the primary data source for this analysis.

Childhelp hotline services can be used by youth, caretakers, or other concerned adults to receive confidential information or support. Before getting connected to a professional crisis counselor, the user provides non-identifying demographic information. Upon completion of their session, counselors complete a post-interaction survey, where they classify the user based on the concerns raised (e.g., physical abuse, sexual abuse, abandonment, discipline/behavioral issues, domestic violence etc.). As of March 2020, “COVID-19” was added to this list. During the pandemic, the majority of non-phonecall modality users were children (Ortiz et al., 2021). Therefore, for the purpose of this study, given our interest in youth perspectives of changes in conflict and abuse dynamics during stay-at-home orders, we used all text and chat transcripts between May 1st and June 30th that were classified as coming from users under the age of 18, with a co-occurring COVID-19 concern, as signified by the counselor classification (n = 105). These transcripts were then transferred to a secure data system for analysis. This study was deemed exempt by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

Analysis

We used thematic analysis to identify COVID-19 related changes in family conflict and abuse dynamics from the perspectives of youth. Transcripts were initially read and re-read by the first and second author to identify central concepts and develop a preliminary code list. Codes were developed based on user references to family conflict or abuse changes and escalations attributed to COVID-19, COVID-19 related stressors, or sheltering-in-place. A threshold of 5 was set prior to the coding process to distinguish the minimum frequency of users for each code needed to contribute to generated themes. Codes were defined and discussed by the first and second author, prior to being applied to the entirety of the sample by the first author. An audit trail using personal, theoretical and analytic memos was maintained and reviewed every other week by the second author, with new coding concepts being discussed at length prior to applying them to the whole sample. As a way to verify coding accuracy and ensure a “continuous dialogue between researchers to maintain consistency of the coding” (Walther et al., 2013; p. 650), the third author used the defined codelist to double code every 10th transcript. We used the formula described in Miles and Huberman (1994) (reliability = number of agreements/ number of agreements + disagreements) to determine the percent agreement between the first and third author (Interrater Reliability = 0.825). Reconciliation meetings were mediated by the second author to clarify coding discrepancies and codelist definitions prior to thematic generation. Two codes were dropped due to low frequency (n < 5). Thematic generation using the remaining codes occurred through systematic identification of grounded and axial codes in line-by-line constant comparison (Strauss & Corbin, 1997). Data management was conducted in NVivo (QSR International Pty Ltd., 2020). Quotations are reported in the results section by de-identified user number. See Table 1 for code definitions in order of user frequency.

Table 1.

Code definitions in order of user frequency

| Code | Definition | Frequency (# of users that had each code) |

|---|---|---|

| Sources of family conflict during stay-at-home-orders from the perspectives of youth | ||

| Caregiver not properly addressing child mental health needs | Any reference to one’s caregiver not allowing child to get the help they need for their mental health concerns or not taking their mental health symptoms seriously | 25 |

| Escalating abuse of children during lockdown | Any reference to abuse of children initiating or escalating due to stay at home orders | 24 |

| Conflict around leisure time activities | Any reference to conflict in the home due to how the child spends time outside of virtual school | 20 |

| Heightened tensions due to close proximity | Any reference to sheltering-in-place or lockdown procedures increasing time spent with individuals inside of the home, causing tension or conflict | 15 |

| Increased exposure to substance use in the home | Any reference to caregiver or sibling substance use creating conflict or harm during lockdown | 14 |

| School expectations and enforcement | Any reference to abuse or conflict initiation or escalation as punishment for school-related “failures” or enforcement | 13 |

| Conflict related to caregiver mental health concerns | Any reference to conflict stemming from caregiver mental health issues or symptoms | 12 |

| Conflict related to youth externalizing behaviors | Any reference to family conflict rt behaviors caregivers may deem as “acting out” (i.e. child substance use, emotional outbursts, sneaking out, sexual endeavors) | 10 |

| Witnessing violence in the home | Any reference to abuse of other family members initiating or escalating due to stay at home orders | 9 |

| Chores and household obligations | Any reference to conflict in the home occuring related to chores or the child not fulfilling household obligations | 7 |

| Impact of family conflict during stay-at-home orders on youth | ||

| The need to find new ways to cope at home | Any reference to needing to learn new coping strategies or skills to deal with conflict in the home | 37 |

| Difficulties finding escape | Any reference to it being difficult to find mental or physical escapes from abuse or conflict due to the lockdown | 23 |

| Lack of access to technology to communicate | Any reference to a child being unable to communicate with people outside of the home due to lack of access to a computer, phone, or other means of virtual communication | 21 |

| Challenges with telephone reporting | Any reference to challenges reporting abuse via trrereewtelephone | 20 |

| Inability to see people outside of the home | Any reference to being unable to see people outside the home that would typically intervene or provide support in in abuse/ conflict situations | 19 |

| Decline of child mental health | Any time a child references their mental health has declined since COVID started | 18 |

| Fears of abuse or violence escalation | Any reference to a child feeling scared, fearful, or afraid of abuse or violence escalation | 18 |

| Technological isolation as an abuse tactic | Any reference to a parent restricting or limiting a child’s technology use to either isolate the individual or keep the conflict within the home | 17 |

| Inability to have candid discussions at home | Any reference to difficulties having private conversations with family members or professional supports due to close proximity to others in the home | 17 |

| Lack of availability of professional supports | Any reference to typical mental health or violence supports being unavailable or difficult to access due to COVID | 16 |

| Inability to access safe places | Any reference to previously safe places being no longer available to turn to due to the pandemic | 12 |

| Separation from typical support people | Any reference to a loved one or responsible adult being unable to be near children due to risk of infection or sheltering-in-place | 10 |

Results

Study Sample

In the timeframe of this study (May–June 2020), Childhelp received 21,778 user inquiries, with 13% identifying as under 18 years old. Among this group, over three-quarters (76.2%) accessed services via text or chat, with 58.3% of text and chat inquiries being from users age 18 and younger (see Ortiz et al., 2021 for Child help user reporting trends). To be included in our sample, inquiries needed to be coming from a user under the age of 18 and have a “COVID-19 concern” classification, as signified by the responding Childhelp counselor. Of 146 text and chat transcripts extracted during the study period, 105 (71.9%) met inclusion criteria. Youth in the study ranged from 10 to 18 years old, with an average age of 15.1 years. Most users communicated by chat (74%) and average active communication time was 51.7 min. This sample includes transcripts from female (63.5%), male (25.0%), non-binary (6.7%), transgender (1.9%), and intersex (1.0%) youth. Inquiries came from across all regions of the United States. See Table 2 for additional demographic information.

Table 2.

Sample characteristics

| Mean (SD) | Range | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 15.1 years (1.8 years) | [10–18 years] | |

| Length of Communication | 51.7 min (24.1 min) | [14–135 min] | |

| Individuals | Percentage | ||

| Communication Type | Chat | 78 | 74% |

| Text | 27 | 26% | |

| Gender* | Female | 66 | 63.5% |

| Male | 26 | 25.0% | |

| Non-Binary | 7 | 6.7% | |

| Transgender Male | 2 | 1.9% | |

| Intersex | 1 | 1.0% | |

| Other | 2 | 1.9% | |

| Region* | Midwest | 14 | 24.1% |

| Northeast | 11 | 19.0% | |

| South | 16 | 28.0% | |

| West | 17 | 29.3% | |

*Total number of individuals not equal to 105 as not all users indicated gender or region. Percentages are calculated for those who did respond

Aim 1: Sources of Family Conflict During Stay-at-home Orders

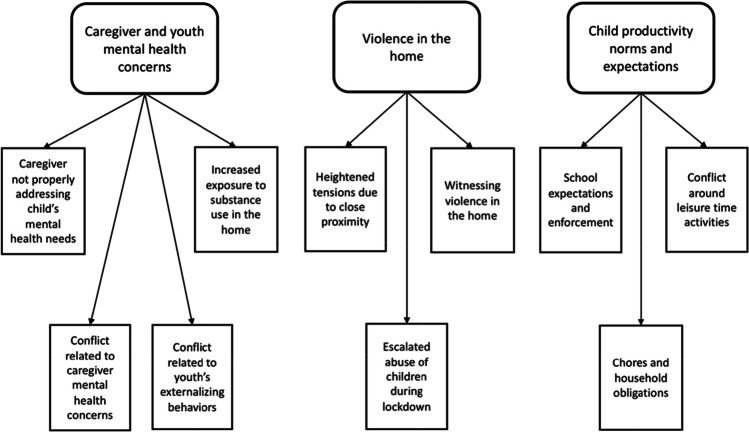

Youth sought help from the hotline related to diverse sources of family conflict. Most conflicts, however, stemmed from exacerbated child or caregiver mental health concerns, violence in the home, or issues transitioning child productivity norms and expectations while sheltering-in-place (see Fig. 1 for codes associated with each theme).

Fig. 1.

Sources of family conflict during stay-at-home-orders from the perspectives of youth

Child Productivity Norms and Expectations

Transitions to remote learning and the halting of many afterschool activities due to infection risk seemed to perpetuate conflict in the home surrounding how youth spent their time both during and after virtual school. With caregivers primarily being in charge of the enforcement of virtual school, users voiced increased school-related conflict, sometimes even manifesting in abuse. For example, one 15 year old girl shared, “My mom just very recently threatened to hurt me, as in giving me a spanking for each missing assignment I have, which is a lot because I haven't been able to do well with the online schooling” (User 806). Outside of school, conflict arose in the home relating to how children were spending their leisure time and how they were contributing to the house via chores or other obligations. A 16 year old girl shared, “I rarely feel like I'm getting to spend time with [my mom]. That is, except when she decides it's time to do chores. She expects me to drop whatever I'm doing (regardless of how important it might be) and work. If I don't, she becomes really angry. She yells and sometimes threatens to spank me with her hairbrush” (User 626). Often, users voiced feeling that their parents put them down as being “lazy” when tasks were not completed, rather than recognizing the drivers as to why they were unable to do the tasks requested. For example a 15 year old girl shared, “I tried telling [my mom] my concern of having ADHD [Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder] or autism and she pushed it aside with, ‘you're not a moron, you're just lazy.’ I find it hard to communicate with my mom on anything like this because of the way she reacts” (User 806). A 14 year old boy additionally shared, “another reason i get into trouble is because of how little I ‘contribute to the family’ and how I’m not a ‘good member of the family’ but I at the same time don’t feel like part of their family’” (User 550). Discrepancies in expectations of how youth spent their time at home, whether they seemed reasonable or not on the surface, seemed to perpetuate family discord and create tension within household environments.

Caregiver and Youth Mental Health Concerns

The fear, uncertainty, and lack of access to typical supports outside the home due to the COVID-19 lockdown seemed to exacerbate both caregiver and youth mental health concerns, contributing to conflict within the home. In terms of caregiver mental health, youth often noticed when parents’ mental health concerns went unaddressed, typically leading to verbal or physical arguments. For example, one 17 year old intersex person shared, “[My mom] just started yelling at me about my attitude, which makes no sense, because I hadn't said literally anything…She called me a bunch of names, and told me to shut up. She's always been this way, but she's also under extra stress. The pandemic seems to really be toying with her head” (User 597). A 16 year old girl reflected on her mother’s mental health concerns and the conflict and abuse associated saying, “[My mom] is very emotionally abusive to all of us. My father has told me before about his thoughts of suicide. I'm honestly pretty scared” (User 676). Being in the home more than usual often exposed youth to caregiver mental health symptomology more than they had previously, often leading to feelings of responsibility to take care of their parent. One 13 year old girl shared, “My dad has NPD [narcissistic personality disorder] and is on the spectrum…that's just who he is and I can't change that and I’m stuck with him because he's just trying his best but he is abusive and doesn't even realize it” (User 768). Being home also exposed youth to caregiver and sibling substance use more than before, often leading them to witness subsequent violence more than pre-pandemic times, illustrated by a 15 year old girl saying, “I have a mother who drinks over the top and when she does, she takes it to the extreme calling me a ‘bitch.’ threatening to drag me and beat me…I don’t know what to do, I feel like I wake up everyday constantly going through this with a drunk mom and I feel stuck and constantly down or not good enough” (User 107). Ultimately, many children mentioned desires for their parents to engage in mental health counseling to attempt to alleviate conflict in the home. One 16 year old boy even opened his chat session by asking the counselor “I’m curious to know how to convince a parent to seek counseling” (User 462). Not all parents, however, were willing to seek help for their mental health problems as highlighted by a user statement saying, “[My parents] are not the type of parents who believe in counseling…they just place all the blame on my sister and I” (User 133).

Youth also faced unique pandemic-exacerbated mental health symptoms, causing conflict in the home due to both their resulting externalizing behaviors as well as their frustration at their caretakers for not appropriately addressing their mental health needs. A 17 year old girl shared an experience when her mom found out that she snuck out, saying “My mom came in screaming because she went through my phone and found out I snuck out. I was yelling back too- I just don't remember anything I was saying. I struggle with mental health issues and threatened to kill myself and she said she’d 'help me shove them down my throat'” (User 012). Despite the high symptom burden of the youth contacting the hotline, some users voiced frustration that their parents “would not let them” seek counseling (n = 15) or did not take their concerns seriously. A 15 year old non-binary user shared, “she doesn’t even want to get me help for my problems. my doctor told us that i might have mild to severe depression and anxiety, and she acts like it never happened. if i try to bring it up she'll just shrug it off (User 707). A 15 year old girl explained, “My parents won't do anything with a counselor because they don't want us kids saying things that could get them in trouble” (User 193).

Violence in the Home

Around a quarter of our sample (n = 25) explicitly contacted the hotline for physical violence they either experienced or witnessed in their home during the first few months of the pandemic. While many children mentioned that they experienced either emotional or physical abuse in the past, most shared that these situations “have been worse due to quarantine” (User 641). One 16 year old boy shared, “It started off as petty disputes a few years ago but now is erupting into full on heated arguments with cursing and physical actions” (User 462). The abuse shared with the counselors was often graphic and detailed. Without having school as an escape, many felt violence was never-ending, causing many to feel “stuck” and a strong desire to be placed outside of their home. A 15 year old girl shared, “It has just been building up and I don't think I can handle it anymore, I need someone to help me” (User 108). Another 15 year old girl shared similar sentiments saying, “I either want to get out of my house or get my dad out of it” (User 721). Children also voiced witnessing violence perpetrated against other family members in their home. One 11 year old girl shared, “My mom and dad are fighting a lot and its starting to scare me. My dad threw a pot at her yesterday and it almost hit me” (User 992). Many children feared involving police or calling child protective services, however, due to lack of trust of a beneficial outcome or fear of parental retaliation. For those that did want to report the violence they were experiencing or witnessing, many experienced barriers surrounding limited reporting options (most states only had phone reporting options for non-mandated reporters).

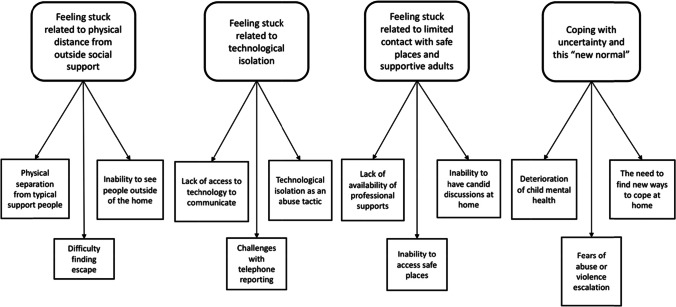

Aim 2: Impact of Family Conflict on Youth

Youth commonly voiced feeling unable to get relief from family conflict in the home due to pandemic constraints, exacerbated from their 1) physical distance from social supports outside the home, 2) technological isolation making it difficult to reach out to others and report their experiences, and 3) limited contact with typical safe places or supportive adults. To cope and survive, youth and crisis counselors needed to get creative to find home-based coping skills to manage uncertainty and help children cope with this “new normal.” See Fig. 2 for codes associated with each theme.

Fig. 2.

Impact of family conflict during stay-at-home orders on youth

Lack of Relief Related to Physical Distance from Outside Social Support

Due to the pandemic, many users voiced feeling stuck because they were unable to see people outside the home who have supported them through times of family conflict in the past. For example, one 13 year old female mentioned how she would typically escape to their aunt and uncle’s home during times of family conflict, but “since covid is happening [she doesn’t] know if theyll let [her] live with them” (User 257). Other children mentioned a lack of access to professional supports (e.g. school counselors, doctors, coaches). One 15 year old male shared, “I spoke to my doctor about mental stuff before the shelter in place happened. However I didn't say much about the [abusive] relationship between me and my brother. He recommended me to go to a psychiatrist the week after but then the lockdown occurred so I haven't been able to tell an adult who could help” (User 540). Another reflected on being unable to engage in school counseling services virtually, saying “There aren’t any adults that I trust enough to talk to besides my school counselor. I can’t talk to her anymore though because of the whole corona thing though” (User 666). Users also mentioned the absence of members of their household who typically buffered conflict, making it easier for abuse and verbal altercations to escalate. For example, one user said, “But ever since quarantine started (especially since my mom had to leave the country and can't return until June), there have been more occurrences of him shouting and yelling at us at small things” (User 641). By being unable to be physically present with these support people, users often felt unable to find physical comfort from stressors inside the home.

Lack of Relief Related to Technological Isolation

About a quarter of our sample (n = 25) mentioned some form of technological access issues, impacting their ability to connect with others outside the home and report their abuse experiences. Some did not have access to technology before the pandemic and the shift to socialization primarily being online caused them to feel unable to reach out to seek support. For example, one 11 year old female reached out to the chatline via her father’s computer, but was unable to get ahold of her aunt to let her know what was going on because she didn’t have a phone to call her (User 992). Another user stated that he was only able to contact the chatline because he was on the family computer for “school work” (User 907). 17 of the 25 users with technological access issues attributed it to their caregivers taking their electronics away, either as punishment or to keep them from contacting those outside the home. For example, when a counselor told a 13 year old female to call CPS she explained “I will try but my parents broke my phone and put it in water” (User 068). Another shared, “I feel really isolated and lonely because my dad took me and my sisters phones and he wants to destroy our contact with our friends and relatives” (User 974). Some users kept secret phones “for purposes like this” (User 707) (i.e. situations they would need help). While others hid phones given to them by friends or family because they “wanted to make sure [the user] was safe” (User 134). Ultimately, the ability for parents to control phone use made reporting to child abuse hotlines particularly difficult, as many states did not have any alternative reporting options. Twenty users were unable to call Child Protective Services (CPS) for these reasons, giving them limited options for professional intervention.

Lack of Relief Related to Limited Contact with Safe Places and Supportive Adults

For many users school, sports, and other afterschool activities were perceived as safe places to escape homes with conflict. Additionally, the adults who users came in contact with there often supported them during times of family conflict, and the ceasing of many school-related and extracurricular activities limited users access to these individuals. For example, one user shared “Most of the time in the past, I would go on my bike and ride to the library to get away, and I would work on homework. I would also browse the internet and blast on loud music on my earbuds just to distract myself” (User 641). Another user shared “I miss school a lot. I felt safe there. Like another home” (User 642). The limited access to sports and those on the team also seemed to impact users with one sharing “obviously we're on lockdown… so there's no where I can go without it being suspicious. I play a sport every season to get away from home as much as I possibly can” (User 544). Another user voiced a similar experience sharing, “I'm lucky enough to be a athlete and I play sports every season so that I can get out of my house, but we're on lock down and I don't know what to do. I normally lock me and my dog in my room for the day” (User 907).

Coping with Uncertainty and this “New Normal.”

With limited access to typical supports outside the home, users were forced to get creative with crisis counseling staff to brainstorm how to survive and cope with family conflict under these unprecedented conditions. Some home-based coping skills that seemed to resonate with users included things that occupied or distracted the mind (User 544), promoted healthy communication habits (i.e. “I” statements; User 554), mindfulness (User 107), and journaling (User 482). One counselor even taught a user how to make a stress ball to use when they were feeling angry or frustrated (User 544). In homes with violence or neglect, however, counselors aimed to create safety plans with users and attempted to find creative solutions to get users connected to phones to report their experiences if they did not have access to them. For example, one counselor told a 17 year old user,

I think it might help to spend some time really processing that and reflecting. Thinking back on the last 3–5 times things have gotten really heated and what the issue was (what was the small thing) and what you might have noticed about your mom (or dad's) facial expressions, words, body positioning. Learning the warning signs is the first step to creating a safety plan (User 653).

Discussion

This study sought to understand how COVID-19 has impacted family conflict and abuse dynamics from the perspectives of youth who accessed a national child abuse hotline. Findings indicated that most commonly disclosed family conflict stemmed from parental or child mental health concerns, violence in the home, or caregiver issues with child productivity while sheltering-in-place, commonly related to school. Many youth voiced feeling unable to get relief from their situation, exacerbated from physical distance from social supports outside the home, technological isolation making it difficult to reach out to others and report their experiences, and limited contact with typical safe places or supportive adults. To cope and survive, youth, with the help of the crisis counselors, often discussed home-based coping skills to help them process their experiences as well as mechanisms to report their abuse experiences to ensure continued safety. These findings are important, as they analyze the crises youth experienced during the early stages of the pandemic in real time, pointing to potential solutions to protect those most vulnerable to abuse and neglect.

Family conflict amid the COVID-19 pandemic may originate through changes in family dynamics. We observe parental and child mental health as a common source of family conflict. Disruption to social networks, family routines, proximity and crowding may impact family well-being and resilience to usual stressors laying the foundation for increased conflict and violence (Prime et al., 2020). In one study that surveyed over 300 adolescents related to their wellbeing amid the pandemic, many reported difficulties staying at home such as social isolation, while nearly a third reported quarrels with caregivers at home (Pigaiani et al., 2020). Our research suggests that, not only can youth recognize these stressors and mental health issues in their caregivers and family members, but they also can come to feel responsible for maintaining parental wellness. Mental health concerns, specifically, may leave some families more vulnerable to the consequences of the pandemic than others (Prime et al., 2020), particularly for those who are experiencing financial hardship, sickness or loss, or who are living with homes with high conflict and violence at baseline. In recent years there has been increasing recognition of the importance of screening for maternal mental health as part of the well-child checks, however state led policies and programs have mostly focused on the female parent in the first year of a child’s life. (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 2016; National Academy for State Health Policy 2021). This is certainly a high-risk time for the development of material depression; however, our findings point to a need to consider screening throughout childhood. Given the frequency with which youth mentioned caregiver mental health as a specific source of distress during COVID-19, policies might be adapted to promote and reimburse for multi-generational screenings during times of national, regional, or local societal disruptions.

Well before the pandemic, the impacts of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) including abuse and neglect across the life course was well established. ACEs have been linked to both poor mental and physical health outcomes.(Felitti et al., 1998) Loneliness itself, as may be conferred by social distancing, has been linked with depression, anxiety, impaired sleep quality, eating disorders, and an increased risk of substance abuse (Rome et al., 2020). Therefore, as demonstrated in our findings, the enhanced family conflict of COVID-19, in addition to youth feelings of isolation at home, may particularly precipitate increased risk of child maltreatment, ACEs, and their sequalae if not addressed. It is known that social support, including outside of the home, can best mitigate these consequences (Yule et al., 2019), however, as we observed, children are feeling particularly isolated from in-person school and extracurricular support systems. In addition to emotional support, this limits children’s access to mandated reporters who may typically intervene in maltreatment risk, making cutting off the ability to communicate with those people particularly dangerous in times of COVID. This has been substantiated by a number of COVID-19 related studies indicating a decrease in child abuse reports, despite experts agreeing that COVID-related stress may increase instances of family conflict and abuse (Thomas et al., 2020). Finally, as evidenced by our observation of caregiver stress related to child productivity and schooling, the abrupt transition to remote learning may confer additional risks of conflict or abuse. Thus, supporting healthy parenting practices particularly around expectation setting for stay-at-home learning may best facilitate families toward posttraumatic growth and fill the gap created by social and economic impacts of the pandemic (Schneider et al., 2017).

Importantly, around 20% of our sample were unable to report their abuse experiences because they did not have access to a phone or experienced challenges making safe phone calls. This is particularly concerning given isolation can become a powerful control and abuse tactic (Mega et al., 2000; Walker et al., 2017; Winters et al., 2020). This highlights the need for additional online child abuse reporting options, which is now only available in nine states (Health and Human Services, 2020). While many youth did not have access to a phone, most did have access to a computer at some point during the day for virtual school. Even those who did have access to a phone voiced a text or chat preference, a fact that was confirmed in a recent study on adolescents text vs. call decisions, particularly surrounding content that is emotional and uncomfortable (Blair et al., 2015). Given this apparent generational preference for text-based services, as well as the safety and access concerns of verbal telephone-based modalities identified in our research, youth facing initiatives, including state run CPS reporting, should consider incorporating or adopting multi-modal access strategies which include a text or chat option.

Our study revealed that users expressed difficulty connecting to mental health professionals either due to lack of access or parental interference. While some investigators are exploring online mental health support for youth (e.g. Ye, 2020) synchronous, online platforms may enable youth (particularly those at highest risk for abuse—e.g. lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning youth; Fish et al., 2020) to feel safe while they seek support from home. Practitioners therefore should familiarize themselves with youth-appropriate mental health resources that can be accessed without parental approval, to allow for continued support for those most vulnerable (Cohen & Bosk, 2020).

Limitations of this study include the limited demographic information collected and the ability to only see transcripts from May–June 2020. In addition, we only analyzed text and chat transcripts, as voice calls are not transcribed per Childhelp confidentiality policy. In addition, this was a secondary analysis of crisis calls, and some themes may be missing if users were directly asked about conflict and abuse in the home. Despite these limitations, this study was the first, to our knowledge, to amplify the real-time concerns of youth experiencing family conflict during COVID-19.

Conclusion

As we reflect on the difficulties of this past year, and the uncertainties of the future, incorporating the perspectives of those most vulnerable for child abuse and neglect is important to ensure we can improve current systems and feel better prepared to support children in the future. Without this particular dataset, these situations and crises might go unrecognized, as the youth users noted little contact with people outside their physical home during the early COVID-19 pandemic. For many, the hotline was the only resource they felt able to seek out easily, due to its confidential nature and easy access via one’s phone or desktop.

Insights and perspectives presented in this study can be used to inform approaches to helping the youth and families most as risk for conflict and maltreatment. Promoting mental health screening and resourcing for both youth and their caregivers seems to be a critical component to improving youth wellness, especially in times of social disruption. Families often had trouble adapting quickly to changes in schooling. Public-health education campaigns on expectation setting and parenting practices could help to normalize these challenges while also introducing coping skills that would benefit the whole family unit. Finally, phone call-based modalities were difficult for some to access and did not align with the preferred communication modalities used by youth. Projects and interventions targeted to this demographic should consider these factors as they introduce or improve service delivery methods.

Collaborations and partnerships between confidential hotlines, researchers, and other organizations are uniquely situation to amplify and aggregate the experiences of children seeking help to uncover patterns, understand trends, and suggest new interventions. Future research should seek to understand how family conflict and abuse dynamics change when stay-at-home orders are lifted as well as the lasting impact of COVID-19 related trauma on child development. By highlighting sources of family conflict and it’s resulting impact on youth, this study hopes to provide a foundation for future exploration into interventions to best support children and their families during times of uncertainty that prioritize safety, health, and wellbeing.

Acknowledgements

The Childhelp National Child Abuse Hotline would like to thank In-N-Out Burger, Walmart Foundation: Community Grants, IRONMAN Foundation, and the Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services for their support. We would also like to thank the National Clinician Scholars Program for funding the research time of the first four authors as well as the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, The Ortner Center on Violence and Abuse, and the Alice Paul Center for Research on Gender, Sexuality, & Women.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Badawy SM, Radovic A. Digital approaches to remote pediatric health care delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic: Existing evidence and a call for further research. JMIR Pediatrics and Parenting. 2020;3(1):e20049. doi: 10.2196/20049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron EJ, Goldstein EG, Wallace CT. Suffering in Silence: How COVID-19 School Closures Inhibit the Reporting of Child Maltreatment. Journal of Public Economics. 2020;190:104258. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker-Blease KA, Turner HA, Finkelhor D. Disasters, Victimization, and Children’s Mental Health: Disasters, Victimization, and Mental Health. Child Development. 2010;81(4):1040–1052. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair BL, Fletcher AC, Gaskin ER. Cell phone decision making: Adolescents’ perceptions of how and why they make the choice to text or call. Youth & Society. 2015;47(3):395–411. doi: 10.1177/0044118X13499594. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SL, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullinger L, Raissian K, Feely M, Schneider W. The Neglected Ones: Time at Home During COVID-19 and Child Maltreatment. SSRN Electronic Journal. 2020 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3674064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). (2016). Maternal Depression Screening and Treatment: A Critical Role for Medicaid in the Care of Mothers and Children. Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services Informational Bulletin.

- Childhelp (2020). Childhelp National Child Abuse Hotline. https://www.childhelp.org/hotline/. Accessed January 26, 2020.

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Marks JS. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;14(4):245–258. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish JN, McInroy LB, Paceley MS, Williams ND, Henderson S, Levine DS, Edsall RN. “I'm Kinda Stuck at Home With Unsupportive Parents Right Now”: LGBTQ Youths' Experiences With COVID-19 and the Importance of Online Support. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2020;67(3):450–452. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick, M., Benson, C., & Bondurant, S. (2020). Beyond Reading, Writing, and Arithmetic: The Role of Teachers and Schools in Reporting Child Maltreatment (No. w27033; p. w27033). National Bureau of Economic Research. 10.3386/w27033.

- Fitzpatrick, O., Carson, A., & Weisz, J. R. (2020). Using mixed methods to identify the primary mental health problems and needs of children, adolescents, and their caregivers during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. 10.1007/s10578-020-01089-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Griffith AK. Parental Burnout and Child Maltreatment During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Family Violence. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10896-020-00172-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health and Human Services. (2020). Child welfare information gateway: state child abuse and neglect reporting numbers. https://www.childwelfare.gov/organizations/?CWIGFunctionsaction=rols:main.dspList&rolType=Custom&RS_ID=%205. Accessed 12 Jan 2020.

- Humphreys KL, Myint MT, Zeanah CH. Increased Risk for Family Violence During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pediatrics. 2020;146(1):e20200982. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, M., Piel, M. H., & Simon, M. (2020). Child Maltreatment during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Consequences of Parental Job Loss on Psychological and Physical Abuse Towards Children. Child Abuse & Neglect, 104709. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Liu JJ, Bao Y, Huang X, Shi J, Lu L. Mental health considerations for children quarantined because of COVID-19. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. 2020;4(5):347–349. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30096-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mega LT, Mega JL, Mega BT, Harris BM. Brainwashing and battering fatigue. Psychological abuse in domestic violence. North Carolina Medical Journal. 2000;61(5):260–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (Second Edi) Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- National Academy for State Health Policy (NASHP). (2021). Maternal depressionscreening. https://healthychild.nashp.org/maternal-depression-screening-2/#toggle-id-1. Accessed 4 Feb 2021.

- Ortiz R, Kishton R, Sinko L, Fingerman M, Moreland D, Wood J, Venkatamarani A (2021). Answering the call: Assessing Trends in Child Abuse Hotline Inquiries in the Wake of COVID-19. JAMA Pediatrics. e210525. Advance online publication. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.0525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Park CL, Russell BS, Fendrich M, Finkelstein-Fox L, Hutchison M, Becker J. Americans’ COVID-19 Stress, Coping, and Adherence to CDC Guidelines. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2020;35(8):2296–2303. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05898-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick SW, Henkhaus LE, Zickafoose JS, Lovell K, Halvorson A, Loch S, Letterie M, Davis MM. Well-being of Parents and Children During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A National Survey. Pediatrics. 2020;146(4):e2020016824. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-016824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigaiani, Y., Zoccante, L., Zocca, A., Arzenton, A., Menegolli, M., Fadel, S., Ruggeri, M., & Colizzi, M. (2020). Adolescent lifestyle behaviors, coping strategies and subjective wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic: an online student survey. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland), 8(4), 472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Prime, H., Wade, M., & Browne, D. T. (2020). Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. The American Pychologist, 75(5), 631–643.10.1037/amp0000660. [DOI] [PubMed]

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2020) NVivo (released in March 2020). https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home. Accessed 19 Jan 2021.

- Rodriguez, C. M., Lee, S. J., Ward, K. P., & Pu, D. F. (2020). The Perfect Storm: Hidden Risk of Child Maltreatment During the Covid-19 Pandemic. Child Maltreatment, 107755952098206. 10.1177/1077559520982066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rome ES, Dinardo PB, Issac VE. Promoting resiliency in adolescents during a pandemic: A guide for clinicians and parents. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 2020;87(10):613–618. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.87a.20055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell BS, Hutchison M, Tambling R, Tomkunas AJ, Horton AL. Initial Challenges of Caregiving During COVID-19: Caregiver Burden, Mental Health, and the Parent-Child Relationship. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. 2020;51:671–682. doi: 10.1007/s10578-020-01037-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider W, Waldfogel J, Brooks-Gunn J. The Great Recession and risk for child abuse and neglect. Children and Youth Services Review. 2017;72:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silliman Cohen, R. I., & Bosk, E. A. (2020). Vulnerable youth and the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatrics, 146(1), e20201306. 10.1542/peds.2020-1306. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Spinelli M, Lionetti F, Pastore M, Fasolo M. Parents’ Stress and Children’s Psychological Problems in Families Facing the COVID-19 Outbreak in Italy. Frontiers in Psychology. 2020;11:1713. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin JM. Grounded theory in practice. Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas EY, Anurudran A, Robb K, Burke TF. Spotlight on child abuse and neglect response in the time of COVID-19. The Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(7):e371. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30143-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther J, Sochacka NW, Kellam NN. Quality in interpretive engineering education research: Reflections on an example study. Journal of Engineering Education. 2013;102(4):626–659. doi: 10.1002/jee.20029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walker, K., Sleath, E., & Tramontano, C. (2017). The prevalence and typologies of controlling behaviors in a general population sample. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 0886260517731785. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Winters GM, Jeglic EL, Kaylor LE. Validation of the sexual grooming model of child sexual abusers. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2020;29(7):855–875. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2020.1801935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J. Pediatric mental and behavioral health in the period of quarantine and social distancing with COVID-19. JMIR Pediatrics and Parenting. 2020;3(2):e19867. doi: 10.2196/19867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yule K, Houston J, Grych J. Resilience in children exposed to violence: A meta-analysis of protective factors across ecological contexts. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2019;22(3):406–431. doi: 10.1007/s10567-019-00293-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]