Abstract

Lessons Learned

The combination of trametinib and sorafenib has an acceptable safety profile, albeit at doses lower than approved for monotherapy.

Maximum tolerated dose is trametinib 1.5 mg daily and sorafenib 200 mg twice daily.

The limited anticancer activity observed in this unselected patient population does not support further exploration of trametinib plus sorafenib in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma.

Background

The RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK signaling pathway is associated with proliferation and progression of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Preclinical data suggest that paradoxical activation of the MAPK pathway may be one of the resistance mechanisms of sorafenib; therefore, we evaluated trametinib plus sorafenib in HCC.

Methods

This was a phase I study with a 3+3 design in patients with treatment‐naïve advanced HCC. The primary objective was safety and tolerability. The secondary objective was clinical efficacy.

Results

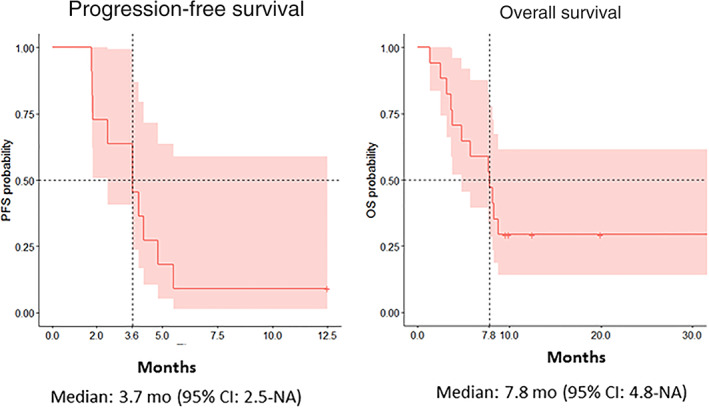

A total of 17 patients were treated with three different doses of trametinib and sorafenib. Two patients experienced dose‐limiting toxicity, including grade 4 hypertension and grade 3 elevation of aspartate aminotransferase (AST)/alanine aminotransferase (ALT)/bilirubin over 7 days. Maximum tolerated dose was trametinib 1.5 mg daily and sorafenib 200 mg twice a day. The most common grade 3/4 treatment‐related adverse events were elevated AST (37%) and hypertension (24%). Among 11 evaluable patients, 7 (63.6%) had stable disease with no objective response. The median progression‐free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were 3.7 and 7.8 months, respectively. Phosphorylated‐ERK was evaluated as a pharmacodynamic marker, and sorafenib plus trametinib inhibited phosphorylated‐ERK up to 98.1% (median: 81.2%) in peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

Conclusion

Trametinib and sorafenib can be safely administered up to trametinib 1.5 mg daily and sorafenib 200 mg twice a day with limited anticancer activity in advanced HCC.

Discussion

In this study, two dose‐limiting toxicities (DLTs), including grade 4 hypertension and grade 3 elevation of AST/ALT/bilirubin, were observed. These DLTs were attributed to both trametinib and sorafenib and were overlapping toxicities. The overlapping toxicities of trametinib and sorafenib were observed in our study and appear to be additive. This occurred despite the fact that most patients were being treated with subtherapeutic doses of sorafenib and trametinib. Diarrhea (82.4%), fatigue (70.6%), and nausea (64.7%) were the most common toxicities, and the prevalence of these toxicities was much less with sorafenib and trametinib monotherapy at therapeutic doses.

The safety profile of trametinib and sorafenib compared with other MEK inhibitors plus sorafenib in HCC seems to be comparable with regard to the hypertension and liver function test (LFT) elevation. Grade 3/4 hypertension was 23.5% with trametinib and sorafenib versus 14.3%–62.5% with the other MEK inhibitors plus sorafenib. Grade 3/4 LFT elevation was 35.3% with trametinib and sorafenib versus 17.1%–45.7% with the other MEK inhibitors plus sorafenib. However, the two reported DLTs attributed to both of these medications were grade 4 hypertension and grade 3 elevation of AST/ALT/bilirubin >7 days. The cardiac, ophthalmologic, and neurologic toxicities observed with refametinib and sorafenib were not seen with trametinib and sorafenib.

Direct comparison of these results should be interpreted cautiously given different study populations and primary objectives. However, the median OS of 7.9 months (Fig. 1) in this study was shorter than that in the refametinib and selumetinib plus sorafenib studies (9.7–14.4 months) or the SHARP trial (10.7 months). A possible reason for our lower median OS is that the recommended therapeutic dose of sorafenib was not reached for most patients in our study, owing to adverse events. Sorafenib demonstrates most efficacy at 400 mg b.i.d., whereas most patients received 200 mg b.i.d. in our study. Similarly, standard dosing for trametinib is 2 mg p.o. every day, whereas the safe dose in combination with sorafenib was 1.5 mg.

Figure 1.

Kaplan‐Meier analysis of progression‐free survival and overall survival.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; NA, not applicable; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression‐free survival.

Our study found that the combination of trametinib and sorafenib has an acceptable safety profile and that the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) is trametinib 1.5 mg daily and sorafenib 200 mg twice daily. However, the limited anticancer activity observed in this unselected patient population does not support further exploration of trametinib plus sorafenib in patients with HCC.

Trial Information

| Disease | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| Stage of Disease/Treatment | Metastatic/advanced |

| Prior Therapy | None |

| Type of Study | Phase I, 3+3 design |

| Primary Endpoints | Safety, maximum tolerated dose |

| Secondary Endpoint | Efficacy |

| Additional Details of Endpoints or Study Design | |

| This was a phase I study with standard 3+3 design. The primary endpoint was MTD of trametinib in combination with sorafenib. Secondary endpoints included safety profile, median OS, median PFS, and disease control rate. Toxicities were monitored according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events criteria, version 4.0. Tumor assessment was performed with computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging at baseline and every 8 weeks until disease progression or treatment discontinuation. Objective response rate was evaluated using RECIST 1.1 criteria. Survival was monitored every 12 weeks after discontinuation of the treatment. | |

| Investigator's Analysis | Drug tolerable, efficacy indeterminant |

Drug Information

| Drug 1 | |

| Generic/Working Name | Trametinib |

| Trade Name | Mekinist |

| Company Name | Novartis |

| Drug Type | Small molecule |

| Drug Class | MEK |

| Dose | 1 and 1.5 mg flat dose |

| Route | p.o. |

| Schedule of Administration | Daily |

| Drug 2 | |

| Generic/Working Name | Sorafenib |

| Trade Name | Nexavar |

| Company Name | Bayer |

| Drug Type | Small molecule |

| Drug Class | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor |

| Dose | 200 and 400 mg flat dose |

| Route | p.o. |

| Schedule of Administration | Twice daily |

Dose Escalation Table

| Dose level | Dose of drug: trametinib | Dose of drug: sorafenib | No. enrolled | No. evaluable for toxicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 mg daily | 200 mg twice daily | 3 | 3 |

| 2 | 1.5 mg daily | 200 mg twice daily | 8 | 8 |

| 3 | 1.5 mg daily | 400 mg twice daily | 6 | 6 |

Patient Characteristics

| Number of Patients, Male | 11 |

| Number of Patients, Female | 6 |

| Stage | Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage B: 2. Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage C: 15 |

| Age | Median (range): 65 (40–80) years |

| Number of Prior Systemic Therapies | Median: 0 |

| Performance Status: ECOG |

0 — 6 1 — 11 2 — 3 — Unknown — |

| Other |

Child‐Pugh score 5: 13 Child‐Pugh score 6: 4 HCV: 5 HBV: 1 AFP <400: 11 AFP >400: 6 Liver cirrhosis: 12 Previous surgery: 2 |

Primary Assessment Method

| Number of Patients Screened | 18 |

| Number of Patients Enrolled | 17 |

| Number of Patients Evaluable for Toxicity | 17 |

| Number of Patients Evaluated for Efficacy | 11 |

| Evaluation Method | RECIST 1.0 |

| Response Assessment CR | n = 0 (0%) |

| Response Assessment PR | n = 0 (0%) |

| Response Assessment SD | n = 7 (64%) |

| Response Assessment PD | n = 4 (36%) |

| Response Assessment OTHER | n = 0 (0%) |

| (Median) Duration Assessments PFS | 3.7 months, CI: 2.5–Not applicable |

| (Median) Duration Assessments OS | 7.8 months, CI: 4.8–Not applicable |

Adverse Events

| All Cycles | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | NC/NA | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | All grades |

| Diarrhea | 17% | 47% | 24% | 12% | 0% | 0% | 83% |

| Nausea | 24% | 76% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 76% |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 29% | 18% | 12% | 35% | 6% | 0% | 71% |

| Fatigue | 29% | 59% | 6% | 6% | 0% | 0% | 71% |

| Blood bilirubin increased | 41% | 24% | 29% | 0% | 6% | 0% | 59% |

| Rash maculo‐papular | 41% | 47% | 12% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 59% |

| Alkaline phosphatase increased | 52% | 18% | 12% | 18% | 0% | 0% | 48% |

| Lymphocyte count decreased | 58% | 12% | 24% | 6% | 0% | 0% | 42% |

| Platelet count decreased | 58% | 24% | 18% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 42% |

| Hypertension | 64% | 6% | 6% | 18% | 6% | 0% | 36% |

| Vomiting | 71% | 29% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 29% |

| Anemia | 82% | 0% | 12% | 6% | 0% | 0% | 18% |

| Neutrophil count decreased | 82% | 12% | 6% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 18% |

| Mucositis oral | 88% | 12% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 12% |

| Palmar‐plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome | 88% | 12% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 12% |

| White blood cell decreased | 88% | 6% | 6% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 12% |

Abbreviation: NC/NA, no change from baseline/no adverse event.

Dose‐Limiting Toxicities

| Dose level | No. enrolled | No. evaluable for toxicity | No. with a dose‐limiting toxicity | Dose‐limiting toxicity information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 6 | 6 | 2 | Grade 4 hypertension, grade 3 elevation of AST/ALT/bilirubin over 7 days |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase.

Assessment, Analysis, and Discussion

| Completion | Study completed |

| Investigator's Assessment | Drug tolerable, efficacy indeterminant |

Sorafenib is the first tyrosine kinase inhibitor approved for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) based on the significant improvement of overall survival compared with placebo controls in a phase III study [1]. However, a majority of patients treated with sorafenib develop disease progression within 6 months, and objective responses are rare, with only 2%–3% of patients achieving partial response [1, 2]. The resistance mechanism of sorafenib has been the subject of extensive studies to improve clinical outcome in HCC. It has been reported that the RAS/RAF/MAPK pathway is one of the critical signaling cascades in tumorigenesis and tumor progression of HCC [3], and RAF inhibition by sorafenib can lead to RAF dimerization and ERK activation in HCC [4], suggesting that the paradoxical ERK activation may be a potential resistance mechanism of sorafenib in HCC. Several preclinical studies demonstrated that the combination of sorafenib and a MEK inhibitor induced synergistic anticancer activity by prevention of paradoxical ERK activation and by potent inhibition of the MAPK pathway for a longer period of time as compared with monotherapy alone in murine HCC models [4, 5, 6]. Based on these data, we conducted a phase I study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of sorafenib combined with trametinib (a highly selective allosteric inhibitor of MEK1/MEK2) in patients with HCC.

The maximum tolerated dose (MTD) was determined to be trametinib 1.5 mg daily and sorafenib 200 mg twice daily. Two reported dose‐limiting toxicities (DLTs), grade 4 hypertension and grade 3 elevation of aspartate aminotransferase (AST)/alanine aminotransferase (ALT)/bilirubin >7 days, were attributed to both trametinib and sorafenib, considering that these are overlapping trametinib and sorafenib toxicities [1, 7]. The most common treatment‐related adverse events were diarrhea, nausea, elevated AST/ALT, and fatigue (Table 1). Ten of 17 patients experienced grade 3/4 adverse events, the most common being elevated AST, hypertension, and elevated alkaline phosphatase.

Table 1.

Drug‐related adverse events

| AE | Trametinib 1 mg + sorafenib 200 mg (n = 3), n (%) | Trametinib 1.5 mg + sorafenib 200 mg (n = 8), n (%) | Trametinib 1.5 mg + sorafenib 400 mg (n = 6), n (%) | Total (n = 17), n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All grades | Grades ≥3 | All grades | Grades ≥3 | All grades | Grades ≥3 | All grades | Grades ≥3 | |

| Diarrhea | 2 (66.7) | 0 | 6 (75) | 1 (12.5) | 5 (83.3) | 0 | 14 (82.4) | 1 (5.9%) |

| Fatigue | 2 (66.7) | 0 | 7 (87.5) | 0 | 3 (50) | 0 | 12 (70.6) | 0 |

| Nausea | 2 (66.7) | 0 | 5 (62.5) | 0 | 4 (66.7) | 0 | 11 (64.7) | 0 |

| Elevated AST | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (12.5) | 4 (50) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) | 10 (58.8) | 6 (35.3) |

| Elevated ALT | 1 (33.3) | 0 | 4 (50) | 0 | 4 (66.7) | 1 (16.7) | 10 (58.8) | 1 (5.9) |

| Rash | 2 (66.7) | 0 | 5 (62.5) | 0 | 3 (50) | 0 | 10 (58.8) | 0 |

| Elevated bilirubin | 1 (33.3) | 0 | 6 (75) | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | 9 (52.9) | 1 (5.9) |

| Elevated alkaline phosphatase | 1 (33.3) | 0 | 3 (37.5) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) | 8 (47.1) | 3 (17.6) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 1 (33.3) | 0 | 4 (50) | 0 | 2 (33.3) | 0 | 7 (41.1) | 0 |

| Hypertension | 0 | 0 | 1 (12.5) | 2 (25) | 1 (16.7) | 2 (33.3) | 6 (35.3) | 4 (23.5) |

| Decreased lymphocyte | 1 (33.3) | 0 | 3 (37.5) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 6 (35.3) | 1 (5.9) |

| Vomiting | 0 | 0 | 3 (37.5) | 0 | 2 (33.3) | 0 | 5 (29.4) | 0 |

| Decreased neutrophils | 1 (33.3) | 0 | 2 (25) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (17.6) | 0 |

| Anemia | 0 | 0 | 3 (37.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (17.6) | 0 |

| Mucositis | 1 (33.3) | 0 | 1 (12.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (11.8) | 0 |

| Hand‐foot syndrome | 0 | 0 | 1 (12.5) | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 2 (11.8) | 0 |

| Decreased WBC | 1 (33.3) | 0 | 1 (12.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (11.8) | 0 |

| Leukocytosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.9) | 1 (5.9) |

| Abdominal pain | 1 (33.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.9) | 0 |

| Alopecia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 1 (5.9) | 0 |

| Anorexia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 1 (5.9) | 0 |

| Bloating | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 1 (5.9) | 0 |

| Cheilitis | 0 | 0 | 1 (12.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.9) | 0 |

| Constipation | 0 | 0 | 1 (12.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.9) | 0 |

| Decreased ejection fraction | 0 | 0 | 1 (12.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.9) | 0 |

| Dysgeusia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 1 (5.9) | 0 |

| Epistaxis | 0 | 0 | 1 (12.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.9) | 0 |

| Flushing | 0 | 0 | 1 (12.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.9) | 0 |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 1 (5.9) | 0 |

| Hot flashes | 0 | 0 | 1 (12.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.9) | 0 |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 0 | 0 | 1 (12.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.9) | 0 |

| Insomnia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 1 (5.9) | |

| Oral dysesthesia | 0 | 0 | 1 (12.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.9) | |

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; ALT, aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; WBC, white blood cell count.

The overlapping toxicities of trametinib and sorafenib observed in our study appeared to be additive. This is despite the majority of patients being treated with subtherapeutic doses of sorafenib and trametinib. Diarrhea was the most common toxicity, seen in more than 80% of patients, compared with 39% with sorafenib monotherapy and 46% with trametinib monotherapy at therapeutic doses (sorafenib 400 mg b.i.d. and trametinib 2 mg) [1, 8]. Other adverse events that were augmented with the combination therapy include nausea (76.5%), fatigue (70.6%), and hand‐foot syndrome (11.8%). The prevalence of these toxicities is much less with sorafenib and trametinib monotherapy at therapeutic doses: nausea is reported at 3.7% with sorafenib and 26% with trametinib, fatigue at 7.4% with sorafenib and 30% with trametinib, and hand‐foot syndrome at 7.1% with sorafenib [1, 8]. Not commonly seen with either drug alone is AST/ALT elevation, seen in 70% of our patients with combination therapy; however, this toxicity is commonly seen with sorafenib combined with other MEK inhibitors [9, 10, 11].

Although the direct comparison of these studies should be interpreted cautiously, the safety profile of trametinib and sorafenib compared with other MEK inhibitors plus sorafenib in HCC (selumetinib and refametinib) seems to be comparable in regard to the hypertension and liver function test (LFT) elevation. Grade 3/4 hypertension was 23.5% with trametinib and sorafenib compared with 14.3%–62.5% with the other MEK inhibitors plus sorafenib; grade 3/4 LFT elevation was 35.3% with trametinib and sorafenib compared with 17.1%–45.7% with the other MEK inhibitors plus sorafenib [9, 10, 11]. However, the two reported DLTs attributed to both of these medications were grade 4 hypertension and grade 3 elevation of AST/ALT/bilirubin >7 days. Although alkaline phosphatase was one of our most common toxicities, this was not evaluated with the other MEK inhibitors. Additionally, the cardiac, ophthalmologic, and neurologic toxicities observed with refametinib and sorafenib were not seen with trametinib and sorafenib [9].

The disease control rate of 63.6% in this study was similar to/slightly better than that reported with sorafenib plus MEK inhibitors refametinib and selumetinib (44.8%–63.0%) [9, 10, 11, 12]. However, the median overall survival (OS) of 7.8 months in this study was shorter than that in the refametinib and selumetinib plus sorafenib studies (9.7–14.4 months) [9, 10, 11] or the SHARP trial (10.7 months) [1].

Of note, direct comparison of these results should be interpreted cautiously given different study populations and primary objectives. One reason lower median OS was demonstrated in our study could be that our population was not enriched for patients bearing tumors with specific mutations. Lim et al. noted that 75% of patients with HCC bearing RAS mutations treated with refametinib and sorafenib exhibited a partial response [9]. Additional upregulation of the RAS pathway may allow the combination of MEK inhibition with sorafenib to be more effective in this enriched population. However, the follow‐up phase II study selected for patients with RAS‐mutated HCC with refametinib and sorafenib demonstrated only 18% partial response and 0% complete response, with 43.8% disease control rate. Reasons this combination may not have been effective can be attributed to intratumoral heterogeneity and new acquired mutations conferring additional resistance mechanisms [10].

Another reason for our lower median OS is that the recommended therapeutic dose of sorafenib was not reached for most patients in our study, owing to adverse events. Sorafenib is most effective at 400 mg b.i.d., whereas most patients received 200 mg b.i.d. in our study [1, 9, 10, 11]. Similarly, at the MTD, the dose of trametinib in the combination was 1.5 mg daily, compared with the approved monotherapy dose of 2 mg daily.

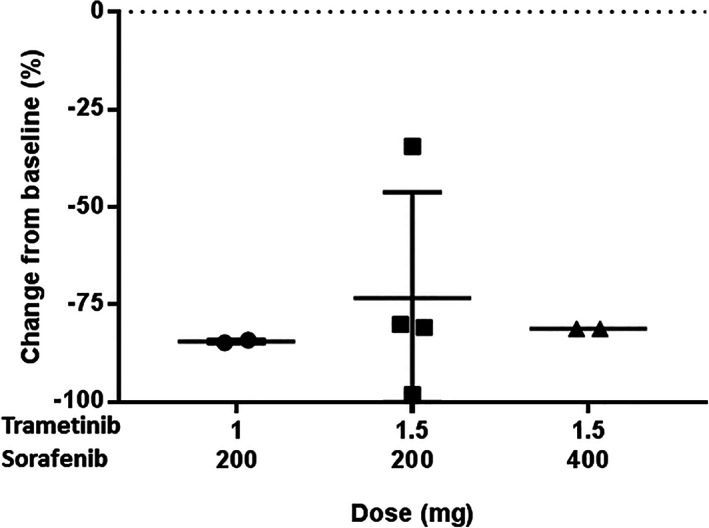

Phosphorylated ERK is a key downstream molecule of the RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK (MAPK) signaling pathway, and baseline phosphorylated ERK level has been suggested as a potential predictive biomarker of sorafenib or sorafenib plus a MEK inhibitor when treating HCC in several in vitro studies [13, 14, 15]. In our study, sorafenib plus trametinib inhibited phosphorylated ERK in peripheral blood mononuclear cells up to 98.1%, and the level of phosphorylated ERK inhibition was similar in each cohort (Fig. 2). In contrast to the previous studies, we did not observe any potential predictive or prognostic value of phosphorylated ERK, which may be attributed to the limited number of patients.

Figure 2.

Pharmacodynamic profile (phosphorylated ERK) for trametinib plus sorafenib using an enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay with cell extract from peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

Our study found that the combination of trametinib and sorafenib has an acceptable safety profile and that the MTD is trametinib 1.5 mg daily and sorafenib 200 mg twice daily. However, the limited anticancer activity observed in this unselected patient population does not support further exploration of the combination of trametinib and sorafenib in patients with HCC.

Disclosures

Richard Kim: Bristol‐Meyers Squibb, Bayer, Eisai (C/A), Eli Lilly & Co. (H). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

Table and Figure

No part of this article may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form or for any means without the prior permission in writing from the copyright holder. For information on purchasing reprints contact Commercialreprints@wiley.com. For permission information contact permissions@wiley.com.

Footnotes

- ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02292173

- Sponsor: GlaxoSmithKline

- Principal Investigator: Richard Kim

- IRB Approved: Yes

References

- 1. Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2008;359:378–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia‐Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A phase III randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schmidt CM, McKillop IH, Cahill PA et al. Increased MAPK expression and activity in primary human hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1997;236:54–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen Y, Liu YC, Sung YC et al. Overcoming sorafenib evasion in hepatocellular carcinoma using CXCR4‐targeted nanoparticles to co‐deliver MEK‐inhibitors. Sci Rep 2017;7:44123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Huynh H, Ngo VC, Koong HN et al. AZD6244 enhances the anti‐tumor activity of sorafenib in ectopic and orthotopic models of human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). J Hepatol 2010;52:79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schmieder R, Puehler F, Neuhaus R et al. Allosteric MEK1/2 inhibitor refametinib (BAY 86‐9766) in combination with sorafenib exhibits antitumor activity in preclinical murine and rat models of hepatocellular carcinoma. Neoplasia 2013;15:1161–1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Flaherty KT, Robert C, Hersey P et al. Improved survival with MEK inhibition in BRAF‐mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med 2012;367:107–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Infante JR, Fecher LA, Falchook GS et al. Safety, pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and efficacy data for the oral MEK inhibitor trametinib: A phase 1 dose‐escalation trial. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:773–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lim HY, Heo J, Choi HJ et al. A phase II study of the efficacy and safety of the combination therapy of the MEK inhibitor refametinib (BAY 86‐9766) plus sorafenib for Asian patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2014;20:5976–5985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lim HY, Merle P, Weiss KH et al. Phase II studies with refametinib or refametinib plus sorafenib in patients with RAS‐mutated hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24:4650–4661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tai WM, Yong WP, Lim C et al. A phase Ib study of selumetinib (AZD6244, ARRY‐142886) in combination with sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Ann Oncol 2016;27:2210–2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Adjei AA, Richards DA, El‐Khoueiry A et al. A phase I study of the safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of combination therapy with refametinib plus sorafenib in patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2016;22:2368–2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang C, Jin H, Gao D et al. Phospho‐ERK is a biomarker of response to a synthetic lethal drug combination of sorafenib and MEK inhibition in liver cancer. J Hepatol 2018;69:1057–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liang Y, Chen J, Yu Q et al. Phosphorylated ERK is a potential prognostic biomarker for sorafenib response in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Med 2017;6:2787–2795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang Z, Zhou X, Shen H et al. Phosphorylated ERK is a potential predictor of sensitivity to sorafenib when treating hepatocellular carcinoma: Evidence from an in vitro study. BMC Med 2009;7:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]