Abstract

Purpose

Consanguineous couples are at increased risk of being heterozygous for the same autosomal recessive (AR) disorder(s), with a 25% risk of affected offspring as a consequence. Until recently, comprehensive preconception carrier testing (PCT) for AR disorders was unavailable in routine diagnostics. Here we developed and implemented such a test in routine clinical care.

Methods

We performed exome sequencing (ES) for 100 consanguineous couples. For each couple, rare variants that could give rise to biallelic variants in offspring were selected. These variants were subsequently filtered against a gene panel consisting of ~2,000 genes associated with known AR disorders (OMIM-based). Remaining variants were classified according to American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics/Association for Molecular Pathology (ACMG/AMP) guidelines, after which only likely pathogenic and pathogenic (class IV/V) variants, present in both partners, were reported.

Results

In 28 of 100 tested consanguineous couples (28%), likely pathogenic and pathogenic variants not previously known in the couple or their family were reported conferring 25% risk of affected offspring.

Conclusion

ES-based PCT provides a powerful diagnostic tool to identify AR disease carrier status in consanguineous couples. Outcomes provided significant reproductive choices for a higher proportion of these couples than previous tests.

INTRODUCTION

Autosomal recessive (AR) disease, caused by biallelic pathogenic variants, is generally associated with severe phenotypes and although individually rare, collectively contributes significantly to morbidity and mortality, often in infants and children.1

Each individual is estimated to be heterozygous for up to seven AR pathogenic variants associated with severe disease.1 When both partners of a couple carry a pathogenic variant in the same gene, they have a 25% risk of having affected offspring.2 The risk in nonrelated outbred partners without a family history of disease depends mainly on variant population frequencies related to their ethnic and/or geographical origins. Consanguineous partners have an additional risk, as they share more genetic material than nonrelated partners, which correlates with the inbreeding coefficient Ϝ. For a first cousin relationship, Ϝ is 0.0625, corresponding with 12.5% regions of homozygosity (RoH) across the genome in offspring.3 Consanguinity thus is a reproductive risk for transferral of AR disease.3 In genetic counseling, empiric risk estimates of 2–2.5% additional risk of a congenital disorder in offspring are used for first-degree cousin couples compared with nonconsanguineous couples with a baseline risk of ~2.5% in Europe4,5 (eurocat). However, studies assessing these risks are mostly small, of varying design, and/or based on diagnoses in affected offspring (e.g., neonates with major congenital anomalies).6 To the best of our knowledge systematic studies are scarce, partly due to the lack of a comprehensive carrier test. A recent study using exome sequencing (ES) data to estimate the impact of consanguinity on the incidence of intellectual disability suggests that the additional genetic risk associated with consanguinity may be higher than previously thought.5

The percentage of consanguineous marriages in specific parts of the world, such as the Middle East, West and South Asia, Northern Africa, and parts of Southern Europe ranges from 20% to 50%.7 It reflects traditions in many communities worldwide offering social and economic advantages.8–10 Although such marital practices are less common in Western European societies, increasing migration has led to increased distribution of consanguinity and its recognition as a potential factor in disease incidence and risk assessment.11,12 Preconception risk assessment enables consanguineous couples to make informed reproductive decisions, including options to avoid disease transmission such as prenatal diagnosis (PND) or preimplantation genetic testing (PGT). Relevant for clinical practice is the fact that consanguineous couples who are actually at 25% risk of having affected offspring, but without a positive family history, thus far could not be distinguished from consanguineous couples not at risk, except for relatively frequent disorders. Existing preconception carrier screening (PCS) panels generally contain limited numbers of genes and thus are less effective for the detection of the often (extremely) rare AR disease consanguineous couples may be at risk of13 (personal communication with centers offering smaller panels). Routine diagnostic ES has proven to be a very effective technology to identify new or rare disease genes—among these, many AR genes in consanguineous families.14,15 In a previous study, we presented pilot data and proof of principle of an unbiased ES-based preconception carrier test (PCT) in a research setting,13 showing its feasibility for application in diagnostics. This test was further developed toward a diagnostic, more automated pipeline and implemented in our clinical practice. Here we present the results of diagnostic PCT in 100 consanguineous couples.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Consanguineous couples were included from January 2018 until December 2019. All degrees of relatedness were accepted. Pregnant couples were accepted on case-by-case basis. Early pregnancy, enabling potential reproductive options following the PCT result, was a requirement. Couples were referred by clinical geneticists. The couples’ obstetrical histories ranged from none at all to previous nonaffected or affected or deceased offspring with or without a genetic diagnosis (Suppl. Table S1). Couples were extensively counseled, including about varying severity of the disorders in the test and the fact that PND/PGT may neither be available nor desired for every disease. All couples signed informed consent.

Exome sequencing and PCT gene panel analysis

Routine diagnostic ES and variant calling were performed as described previously.16 ES data were filtered against genes reported in OMIM to be associated with AR disease (1,924–2,198 genes, depending on the gene panel version used at the time of inclusion (Suppl. Table S2 and PCT panel list; link includes previous versions). The panel was updated twice yearly by an expert panel of clinical geneticists and laboratory specialists. No stringent severity criteria were applied. Only genes with (in AR context) unclear or very mild phenotypes (e.g., woolly hair, OMIM 616760, KRT25) were excluded (see Suppl. Table S2 and Discussion for further elaboration). Variants with a dbSNP frequency >5% and homozygous variants in either individual of the couple were removed, after which both data sets were merged to select for genes in which both individuals share an identical or a nonidentical variant. As such, no information was available on individual carrier status results if the partner was not carrying a variant in the same gene. Consequently, the risk of detecting autosomal dominant (AD) disorders (associated with genes that can also cause AR disease) in the couple is very low. Variants were then classified by at least two laboratory specialists according to American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics/Association for Molecular Pathology (ACMG/AMP) guidelines, also including classified variants from our in-house database.16–18 Only variant combinations of class IV (likely pathogenic) and/or V (pathogenic) in the same gene were included in the final diagnostic couple report; variants of unknown significance were not reported. This means, for example, that previously unreported missense variants were not reported. For variants that were borderline based on the ACMG/AMP definitions for class IV/V variants, e.g., if only one reported case had been described, available evidence was assessed by the laboratory specialists for robustness (e.g., functional studies) and experts in the particular field were consulted if deemed appropriate. As the carrier frequency of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is generally high in all populations and in the majority of cases caused by the exon 7–8 deletion in the SMN1 gene, a multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) test was added using the MLPA P460 probe mix (©MRC Holland, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) to determine SMA carrier status.

Standard turnaround time was 100 days and expedited in pregnant cases.

RESULTS

PCT was performed in 100 consanguineous couples (Suppl. Table S1). The majority of couples (56) were first cousins and 6 couples were even more closely related, e.g., double first cousins (Suppl. Table S1/Suppl. Fig. S1). The degree of consanguinity in the remainder varied from second and third-degree cousins to more distant relatedness, and/or couples in whom consanguinity was suspected partly based on the presence of one or more RoH in affected offspring. Twenty-nine percent of couples were of Turkish origin, 18% of indigenous Dutch, 14% of Afghan, 12% of Moroccan, and 10% of Syrian origin. Nineteen couples were enrolled in a PGT procedure because of an earlier genetic diagnosis. Another 23 couples had a known AR genetic diagnosis in one or more previous offspring. One further couple was a known carrier couple of an AR disorder without affected offspring. Fourteen couples presented with one or more affected children without a genetic diagnosis. Forty-three couples presented without a known history of AR disease/carrier state and without offspring affected by an unknown disease. These include couples with children affected by a known nonrecessive genetic diagnosis (i.e., chromosomal). For 5 of these 43 couples, their history included one or more unexplained intrauterine death (IUD) and/or (multiple) miscarriages. Five couples were pregnant at inclusion, with gestational ages between 7 and 10 weeks.

Overall PCT diagnostic yield

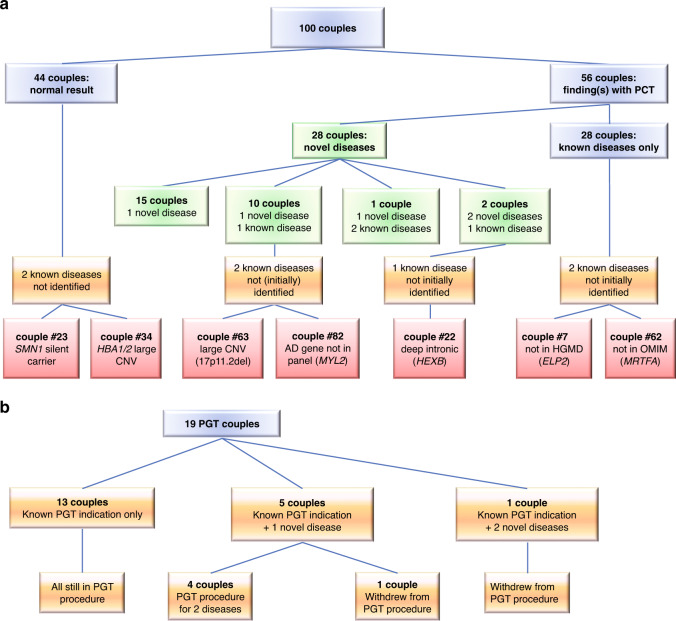

PCT identified 30 novel (i.e., not previously known in the couple or their offspring) carrier couple states in 28/100 couples, resulting in a diagnostic yield for novel findings of 28% (Fig. 1a). The disease categories of the carrier states identified are listed in Suppl. Table S3, the most frequent being metabolic (n = 6), neurologic (n = 5), skeletal (n = 3), congenital deafness (n = 3), hepatic (n = 2), and ocular (n = 2).

Fig. 1. Preconception carrier test (PCT) results.

(a) In the cohort of 100 consanguineous couples. Green boxes: novel detected variants, red boxes: variants not initially detected with the current PCT test design. (b) In the subgroup of couples undergoing preimplantation genetic testing (PGT). AD autosomal dominant, CNV copy-number variant, HGMD Human Gene Mutation Database.

In 13 cases, one (n = 11) or two (n = 2) novel additional carrier couple states were found in couples already known to be carrier couple of one, or two (couple 53), previously identified AR disease(s) (Fig. 1a).

In 6 of the 19 (32%) couples who were already enrolled in a PGT procedure, one (n = 5) or two (n = 1) additional carrier couple states were indeed identified by PCT (Fig. 1b).

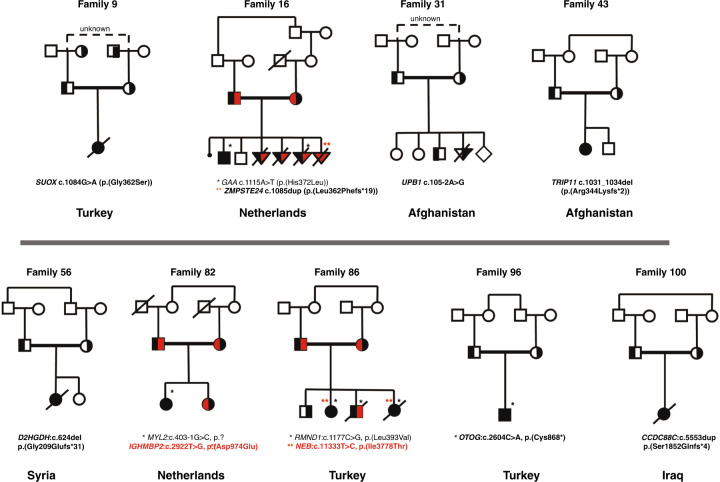

Four novel findings in retrospect provided a likely explanation for the clinical phenotype of undiagnosed affected previous offspring (couples 9, 43, 56, and 100, Table 1). The previous child of couple 9 died at age 10 months, with epilepsy and developmental delay. DNA of the child was not preserved. PCT showed a SUOX variant in both parents, causative for sulfite oxidase deficiency, a lethal metabolic disorder matching the deceased child’s phenotype. Couple 43 lost a child due to a skeletal dysplasia. PCT showed a TRIP11 variant in both parents, associated with achondrogenesis type 1a, matching the phenotype. The daughter of couple 56 died at 3 years of age, with a progressive disorder including epilepsy and deterioration of hearing and vision. PCT identified the couple as carriers of D-2-hydroxyglutaric aciduria (D2HGD2), a neurometabolic disorder matching the phenotype. In couple 100, whose daughter had died of hydrocephalus, PCT demonstrated a variant in the CCDC88C gene, causative for AR congenital hydrocephalus-1.

Table 1.

Clinical and molecular data of the couples with PCT findings (confirmed and newly identified carrier couple states).

| Couple number | Country of origin | Consanguinity | Family history | Number of shared pathogenic variants | Shared pathogenic variant (boldface: novel, detected by PCT) | Disease (for novel findings without previously affected child: most likely associated disease associated with identified variant, based on previous reports of identical or similar variant) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Turkey | Double 1st cousins | One healthy daughter | 1 | Chr5(GRCh37):g.149359991C>T, NM_000112.3(SLC26A2):c.835C>T, p.(Arg279Trp) | Multiple epiphyseal dysplasia, type 4 (OMIM 226900) |

| 2 | Turkey | Double 1st cousins | One daughter homozygous for ATP8A2 variant | 2 |

Chr13(GRCh37):g.26151250C>T, NM_016529.5(ATP8A2):c.1756C>T, p.(Arg586*) Chr13(GRCh37):g.20763452A>G, NM_004004.5(GJB2):c.269T>C, p.(Leu90Pro) |

Cerebellar ataxia, mental retardation, and dysequilibrium syndrome 4 (OMIM 615268) Autosomal recessive deafness type 1 A (OMIM 220290) |

| 4 | Turkey | 1st cousins | One daughter homozygous for HGSNAT variant, three healthy children | 2 |

Chr8(GRCh37):g.43002207G>A, NG_009552.1(HGSNAT):c.234 + 1G>A, p.? Chr1(GRCh37):g.94473807C>T, NM_000350.2(ABCA4):c.5882G>A, p.(Gly1961Glu) |

Mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIC, Sanfilippo C (OMIM 252930) Stargardt disease 1 (OMIM 248200) |

| 6 | Turkey | 1st cousins | One son homozygous for ACOX1 variant, died at age five years | 2 | Chr17(GRCh37):g.73956446G>A, NM_004035.6(ACOX1):c.280C>T, p.(Arg94*) | Peroxisomal acyl-CoA oxidase deficiency (OMIM 264470) |

| 7 | Turkey | 2nd cousins | One daughter homozygous for ELP2 variant, one healthy daughter | 1 | Chr18(GRCh37):g.33736538G>A, NM_001242875.2(ELP2):c.1580G>A, p.(Arg527Gln) | Mental retardation, autosomal recessive 58 (OMIM 616054) |

| 9 | Turkey | Distant | One daughter with epilepsy and intellectual disability, no diagnosis, died at age 10 months | 1 | Chr12(GRCh37):g.56398257G>A, NM_000456.2(SUOX):c.1084G>A, p.(Gly362Ser) | Sulfite oxidase deficiency (OMIM 272300) |

| 10 | Palestine | 1st cousins | One deceased daughter homozygous for SLC26A2 variant | 1 | Chr5(GRCh37):g.149360962_149360965del, NM_000112.3(SLC26A2):c.1806_1809del, p.(Thr603Serfs*5) | Achondrogenesis type 1B (OMIM 600972) |

| 11 | Netherlands | Distant | One son homozygous for SGSH variant | 1 | Chr17(GRCh37):g.78187614C>T, NM_000199.4(SGSH):c.734G>A, p.(Arg245His) | Mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIA (Sanfilippo type A) (OMIM 605270) |

| 14 | Pakistan | 1st cousins | One daughter homozygous for HBB variant | 1 | Chr11(GRCh37):g.5247976_5247979dup, NM_000518.4(HBB):c.143_146dup, p.(Thr51Valfs*4) | β-thalassemia (OMIM 613985) |

| 16 | Netherlands | Distant | One son homozygous for GAA variant; multiple miscarriages; 10 weeks pregnant at inclusion | 2 |

Chr17(GRCh37):g.78082327A>T, NM_000152.3(GAA):c.1115A>T, p.(His372Leu) Chr1(GRCh37):g.40756551dup, NM_005857.4(ZMPSTE24):c.1085dup, p.(Leu362Phefs*19) |

Glycogen storage disease II (Pompe disease) (OMIM 232300) Lethal restrictive dermopathy (OMIM 275210) |

| 21 | Netherlands | Distant | One deceased son homozygous for SFTPB variant; one healthy daughter, one miscarriage | 1 | Chr2(GRCh37):g.85893772delinsTTC, NM_000542.3(SFTPB):c.397delinsGAA, p.(Pro133Glufs*95) | Pulmonary surfactant metabolism dysfunction 1 (OMIM 265120) |

| 22 | Turkey | 1st cousins | One deceased son homozygous for HEXB variant, one healthy daughter | 3 |

Chr2(GRCh37):g.1507755del, NM_000547.5(TPO):c.2422del, p.(Cys808Alafs*24) Chr15(GRCh37):g.83328380_83328383del, NM_001278512.1(AP3B2):c.3235_3238del, p.(Thr1079Serfs*7) Chr5(GRCh37):g.74016587_74016590dup, NG_009770.2(HEXB):c.1613 + 15_1613 + 18dup |

Thyroid dyshormonogenesis 2A (OMIM 274500) Early infantile epileptic encephalopathy 48 (OMIM 617276) Sandhoff disease (OMIM 268800) |

| 28 | Morocco | Distant | One daughter homozygous for OBSL1 variant | 1 | Chr2(GRCh37):g.220432786dup, NM_015311.2(OBSL1):c.1273dup, p.(Thr425Asnfs*40) | 3M syndrome (OMIM 612921) |

| 31 | Afghanistan | 1st cousins | Three healthy children, one IUD at 18 weeks | 1 | Chr22(GRCh37):g.24896073A>G, NG_012858.2(UPB1):c.105-2A>G | β-ureidopropionase deficiency (OMIM 613161) |

| 32 | Turkey | 1st cousins | One son homozygous for ACADVL variant, one healthy son | 1 | Chr17(GRCh37):g.7127050G>A, NG_007975.1(ACADVL):c.1269 + 1G>A | VLCAD deficiency (OMIM 201475) |

| 33 | Syria | 1st cousins | Two sons homozygous for C12orf57 variant | 1 | Chr12(GRCh37):g.7053285A>G, NM_138425.3(C12orf57):c.1A>G | Temtamy syndrome (OMIM 218340) |

| 36 | Morocco | 1st cousins | One son homozygous for MBOAT7 variant, one healthy daughter | 1 | Chr12(GRCh37):g.7053285A>G, NM_024298.4(MBOAT7):c.458_459del, p.(Leu153Glnfs*142) | Mental retardation, autosomal recessive 57 (OMIM 617188) |

| 37 | Palestine | 1st cousins | One son with congenital deafness | 1 | Chr7(GRCh37):g.87041333C>T, NM_000443.3(ABCB4):c.2800G>A, p.(Ala934Thr) | Gallbladder disease 1 (LPAC) (OMIM 600803) |

| 38 | Netherlands | 2nd cousins | Son homozygous for BLM variant | 1 | Chr15(GRCh37):g.91328183C>T, NM_000057.3(BLM):c.2695C>T, p.(Arg899*) | Bloom syndrome (OMIM 210900) |

| 43 | Afghanistan | 1st cousins | One deceased daughter with a skeletal dysplasia, diagnosis unknown | 1 | Chr14(GRCh37):g.92480711_92480714del, NM_004239.4(TRIP11):c.1031_1034del, p.(Arg344Lysfs*2) | Achondrogenesis, type IA (OMIM 200600) |

| 44 | Netherlands | Distant | One daughter with homozygous MRPL44 variant | 1 | Chr2(GRCh37):g.224824538T>G, NM_022915.3(MRPL44):c.467T>G, p.(Leu156Arg) | Combined oxidative phosphorylation deficiency 16 (OMIM 615395) |

| 45 | Syria | 1st cousins | One son homozygous for SMN1 ex7–8 deletion | 1 | NM_000344.3(SMN1): ex7-8del | Spinal muscular atrophy 1 (OMIM 253300) |

| 47 | Morocco | 2nd cousins | One daughter homozygous for TGM1 variant | 1 | Chr14(GRCh37):g.24728366del, NM_000359.2(TGM1):c.1074del, p.(Ser358Argfs*26) | Ichthyosis, congenital, autosomal recessive 1 (OMIM 242300) |

| 51 | Turkey | Double 1st cousins | One daughter homozygous for SCAPER variant | 2 |

Chr15(GRCh37):g.77057949_77057952del, NM_020843.3(SCAPER):c.1447_1450del, p.(Phe483Valfs*30) Chr7(GRCh37):g.87041275G>T, NM_000443.3(ABCB4):c.2858C>A, p.(Ala953Asp) |

Intellectual developmental disorder and retinitis pigmentosa (OMIM 618195) Cholestasis, progressive familial intrahepatic 3 (OMIM 602347) |

| 52 | Turkey | 1st cousins | One son, one daughter homozygous for NEK9 variant, one healthy daughter | 1 | Chr14(GRCh37):g.75576537G>A, NM_033116.5(NEK9):c.1033C>T, p.(Arg345*) | Lethal congenital contracture syndrome 10 (OMIM 617022) |

| 53 | Yemen/Sudan | 2nd cousins | One deceased daughter homozygous for WDR73 and IGHMBP2 variants | 3 |

Chr11(GRCh37):g.68696686G>T, NM_002180.2(IGHMBP2):c.1096G>T, p.(Glu366*) Chr15(GRCh37):g.85186706del, NM_032856.3(WDR73):c.1132del, p.(Arg378Alafs*25) Chr11(GRCh37):g.102991434C>T, NM_001080463.1(DYNC2H1):c.1151C>T, p.(Ala384Val) |

Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease, axonal, type 2S (OMIM 616155) Galloway–Mowat syndrome 1 (OMIM 251300) Short-rib thoracic dysplasia 3 with or without polydactyly (OMIM 603297) |

| 54 | Pakistan | 3rd cousins | Two deceased sons homozygous for VIPAS39 variant | 1 | Chr14(GRCh37):g.77910630del, NM_001193314.1(VIPAS39):c.559del, p.(Glu187Argfs*3) | Arthrogryposis, renal dysfunction, and cholestasis 2 (ARCS2) (OMIM 613404) |

| 56 | Syria | 1st cousins | One deceased daughter, died at 3 years, progressive deterioration of hearing, seeing, epilepsy, no clinical diagnosis | 1 | Chr2(GRCh37):g.242683170del, NM_152783.4(D2HGDH):c.624del, p.(Gly209Glufs*31) | D-2-hydroxyglutaric aciduria (OMIM 600721) |

| 61 | Syria | 1st cousins | Son homozygous for HBB variant | 1 | Chr11(GRCh37):g.5248232T>A, NM_000518.4(HBB):c.20A>T, p.(Glu7Val) | Sickle cell anemia (OMIM 603903) |

| 62 | Turkey | 1st cousins | Son and daughter homozygous for MRTFA variant | 1 | Chr22(GRCh37):g.40815086dup, NM_020831.4(MRTFA):c.1356dup | Immunodeficiency 66 (OMIM 618847) |

| 63 | Syria | 1st/2nd cousins | Son with Sjogren–Larsson syndrome (arr 17p11.2(19,447,016-19,655,447)x0, one healthy daughter | 2ϯ |

Chr6(GRCh37):g.51609303A>G, NM_138694.3(PKHD1):c.10036T>C, p.(Cys3346Arg) maternal Chr6(GRCh37):g.51484077G>C, NM_138694.3(PKHD1):c.12027C>G, p.(Tyr4009*) paternal both carry (arr 17p11.2(19,447,016-19,655,447)x1 |

Polycystic kidney disease 4, with or without hepatic disease (OMIM 263200) Sjogren–Larsson syndrome |

| 65 | Afghanistan | 1st cousins | Two children homozygous for TCIRG1 variant | 1 | Chr11(GRCh37):g.67811762dup, NM_006019.3(TCIRG1):c.971dup, p.(Cys324Trpfs*166) | Osteopetrosis, autosomal recessive 1 (OMIM 259700) |

| 66 | Iraq | 1st cousins | 2ϯ |

Chr16(GRCh37):g.3293447C>G, NM_000243.2(MEFV):c.2040G>C, p.(Met680Ile), paternal Chr16(GRCh37):g.3293407T>C, NM_000243.2(MEFV):c.2080A>G, p.(Met694Val), maternal |

Familial Mediterranean fever, AR (OMIM 249100) | |

| 70 | Netherlands | 3rd cousins | One child homozygous for GJB2 variant | 1 | Chr13(GRCh37):g.20763686del, NM_004004.5(GJB2):c.35del, p.(Gly12Valfs*2) | Deafness, autosomal recessive 1A (OMIM 220290) |

| 71 | Turkey | 1st cousins | One son homozygous for PLA2G6 variant, one healthy daughter | 2 |

Chr22(GRCh37):g.38536033dup, NM_003560.3(PLA2G6):c.753dup, p.(Asn252Glnfs*130) Chr1(GRCh37):g.152281672del, NM_002016.1(FLG):c.5690del, p.(His1897Profs*198) |

Infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy 1 (OMIM 256600)/neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation 2B (OMIM 610217) Ichthyosis vulgaris (OMIM 146700) |

| 72 | Netherlands | 1st cousins | 1 | Chr3(GRCh37):g.171431702G>A, NM_002662.4(PLD1):c.892C>T, p.(Arg298*) | Cardiac valvular defect, developmental (OMIM 212093) | |

| 75 | Unknown | 1st cousins | Seven spontaneous abortions, one healthy son | 1 | Chr12(GRCh37):g.110029107G>A, NM_000431.3(MVK):c.830G>A, p.(Arg277His) | Hyper-IgD syndrome (OMIM 260920) |

| 76 | Netherlands | 1st cousins | Deceased daughter homozygous for CLPB variant, one IUD at 16 weeks, one miscarriage; 7 weeks pregnant at inclusion | 2 |

Chr11(GRCh37):g.72005169G>A, NM_030813.5(CLPB):c.1772C>T, p.(Ala591Val) Chr16(GRCh37):g.84203896C>T, NM_178452.5(DNAAF1):c.1462C>T, p.(Arg488*) |

3-methylglutaconic aciduria, type VII, with cataracts, neurologic involvement and neutropenia (OMIM 616271) Ciliary dyskinesia, primary, 13 (OMIM613193) |

| 77 | Morocco | 1st cousins | One healthy daughter | 1 | Chr11(GRCh37):g.93523799_93523800del, NM_004268.4(MED17):c.477_478del, p.(Leu160Ilefs*9) | Microcephaly, postnatal progressive, with seizures and brain atrophy (OMIM 613668) |

| 78 | Afghanistan | 1st cousins | One termination of pregnancy homozygous for WNT10B and PKP1 variants | 2 |

Chr12(GRCh37):g.49360307del, NM_003394.3(WNT10B):c.741del, p.(Cys247*) Chr1(GRCh37):g.201288984C>T, NM_000299.3(PKP1):c.1273C>T, p.(Gln425*) |

Split-hand/foot malformation 6 (OMIM 225300) Ectodermal dysplasia/skin fragility syndrome (OMIM 604536) |

| 80 | Morocco | Distant | One daughter with ID and epilepsy | 1 | Chr15(GRCh37):g.28171357_28171358del, NM_000275.2(OCA2):c.1994_1995del, p.(Ala665Glyfs*4) | Albinism, oculocutaneous, type II (OMIM 203200) |

| 81 | Morocco | 1st cousins | One healthy daughter, one son homozygous for SLC13A5 variant | 1 | Chr17(GRCh37):g.6597517C>T, NG_034220.1(SLC13A5):c.1056-1G>A, p.? | Epileptic encephalopathy, early infantile, 25 (OMIM 615905) |

| 82 | Netherlands | 1st cousins | One deceased daughter homozygous for MYL2 variant | 2 |

Chr12(GRCh37):g.111348980C>G, NG_007554.1(MYL2):c.403-1G>C, p.? Chr11(GRCh37):g.68707139T>G, NM_002180.2(IGHMBP2):c.2922T>G, p.(Asp974Glu) |

Cardiomyopathy, hypertrophic, 10 (OMIM 608758) Spinal muscular atrophy with respiratory distress (OMIM 604320) |

| 83 | Syria | 1st cousins | One son homozygous for GUCY2D variant | 1 | Chr17(GRCh37):g.7917237G>A, NM_000180.3(GUCY2D):c.2303G>A, p.(Arg768Gln) | Leber congenital amaurosis 1 (OMIM 204000) |

| 84 | Afghanistan | 1st cousins | Three healthy children, 2 deceased sons homozygous for CEP290 variant | 1 | Chr12(GRCh37):g.88513990_88513994del, NM_025114.3(CEP290):c.1419_1423del, p.(Ile474Argfs*5) | Leber congenital amaurosis 10 (OMIM 611755) |

| 85 | Turkey | 1st cousins | Two deceased children homozygous for RMND1 variant, one living daughter homozygous for RMND1 variant and one healthy son | 2 |

Chr6(GRCh37):g.151738437G>C, NM_017909.3(RMND1):c.1177C>G, p.(Leu393Val) Chr2(GRCh37):g.152471058A>G, NM_001164507.1(NEB):c.11333T>C, p.(Ile3778Thr) |

Combined oxidative phosphorylation deficiency 11 (OMIM 614922) Nemaline myopathy 2, autosomal recessive (OMIM 256030) |

| 86 | Afghanistan | 1st cousins | Two deceased daughters homozygous for ERCC6 variant | 3 |

Chr10(GRCh37):g.50691430G>A, NM_000124.3(ERCC6):c.1954C>T, p.(Arg652*) Chr3(GRCh37):g.48929490G>A, NM_000387.5(SLC25A20):c.121C>T, p.(Gln41*) Chr8(GRCh37):g.105441818C>T, NM_001385.2(DPYS):c.905G>A, p.(Arg302Gln) |

Cockayne syndrome, type B (OMIM 133540) Carnitine-acylcarnitine translocase deficiency (OMIM 212138) Dihydropyrimidinuria (OMIM 222748) |

| 88 | Turkey | 1st cousins | One healthy daughter, one son homozygous for HBB variant | 2 |

Chr11(GRCh37):g.5248178_5248184del, NM_000518.4(HBB):c.68_74del, p.(Glu23Valfs*37) Chr19(GRCh37):g.45856060G>A, NM_000400.3(ERCC2):c.1846C>T, p.(Arg616Trp) |

β-thalassemia (OMIM 613985) Xeroderma pigmentosum, group D (OMIM 278730) |

| 90 | Netherlands | 1st cousins | 1 | Chr14(GRCh37):g.88452941T>C, NM_000153.3(GALC):c.334A>G, p.(Thr112Ala) | Krabbe disease (OMIM 245200) | |

| 92 | Iraq | 1st cousins | One daughter homozygous for CTNS variant; 9 weeks pregnant at inclusion | 1 | Chr17(GRCh37):g.3563574G>A, NM_001031681.2(CTNS):c.1015G>A, p.(Gly339Arg) | Cystinosis, nephropathic (OMIM 219800) |

| 93 | Turkey | 1st cousins | One healthy daughter, one deceased son homozygous for ALPL variant | 1 | Chr1(GRCh37):g.21889687G>A, NM_000478.5(ALPL):c.382G>A, p.(Val128Met) | Hypophosphatasia, infantile (OMIM 241500) |

| 94 | Morocco | 1st cousins | Four sons, two healthy, two termination of pregnancy due to hydrops fetalis | 1 | Chr17(GRCh37):g.18023748C>T, NM_016239.3(MYO15A):c.1634C>T, p.(Ala545Val) | Deafness, autosomal recessive 3 (OMIM 600316) |

| 95 | Morocco | Distant | One son homozygous for CHKB variant | 1 | Chr22(GRCh37):g.51018188dup, NM_005198.4(CHKB):c.999dup, p.(Leu334Thrfs*95) | Muscular dystrophy, congenital, megaconial type (OMIM 602541) |

| 96 | Turkey | 1st cousins | 8 weeks pregnant at inclusion | 1 | Chr11(GRCh37):g.17598421C>A, NM_001277269.1(OTOG):c.2604C>A, p.(Cys868*) | Deafness, autosomal recessive 18B (OMIM 614945) |

| 97 | Afghanistan | 1st/3rd cousins | One daughter homozygous for TH variant | 1 | Chr11(GRCh37):g.2185575G>A, NM_199292.2(TH):c.1475C>T, p.(Pro492Leu) | Segawa syndrome, recessive (OMIM 605407) |

| 100 | Iraq | 1st cousins | One deceased daughter due to hydrocephalus, diagnosis unknown | 1 | Chr14(GRCh37):g.91739503dup, NM_001080414.3(CCDC88C):c.5553dup, p.(Ser1852Glnfs*4) | Hydrocephalus, congenital, 1 (OMIM 236600) |

In bold: newly identified (novel) variants, in red: variants not (initially) identified by the current bioinformatics pipeline. ϯ indicates detection of compound heterozygous variants in the couple.

AR autosomal recessive, ID intellectual disability, IUD intrauterine death.

Finally, two novel findings in our series of 100 consisted of nonidentical variant carrier states potentially resulting in compound heterozygous variants in offspring, not associated with the consanguineous background but nevertheless a clinically significant finding of PCT (couples 63 and 66, Table 1).

Overall, 58/100 (58%) couples in our series are proven carrier couples for AR disease (Suppl. Table S1), of which 56 could be identified by our PCT (Table 1, Fig. 1a, Suppl. Fig. S1).

PCT initially confirmed 38 of the 45 previously known carrier states in 43 couples: 7 known carrier states were not (primarily) detected by PCT (Fig. 1a, Suppl. Table S4). There were four different reasons for this: (1) copy-number variants (CNVs) are not detected by ES (couple 23, wherein one parent carries two SMN1 copies on one allele; couple 34, with a 3.4-kb deletion in the HBA1 and HBA2 genes; couple 63, with a 17p11.2 deletion), (2) delay in available literature not known at time of analysis (couples 7 and 62), (3) pipeline settings (couple 22 carries a deep intronic variant that is filtered out in the current ES analysis), and (4) exclusively registered with AD inheritance (couple 83).

Seven couples whose PCT results came back negative have offspring with a phenotype lacking a genetic diagnosis, such as rhabdomyolysis, congenital myopathy, or intellectual disability (Suppl. Table S1). Another three couples were shown to be carrier couples of diseases that did not explain their offspring’s phenotypes. The unidentified potential (genetic) causes of these phenotypes are diverse and do not necessarily derive from a failure of our analysis. At least some of the affected children underwent previous diagnostic ES that failed to identify any genetic cause.

Follow-up (Fig. 1b, Fig. 2)

Fig. 2. Family pedigrees described in more detail in the paper.

For all pedigrees, see Supplementary Figure S1. *● homozygous for black variant,  homozygous red variant, half filled symbols are heterozygous variants.

homozygous red variant, half filled symbols are heterozygous variants.

Couple 9 (SUOX) opted for PGT and are currently awaiting their first treatment. Couple 31 (UPB1) was pregnant at the moment the PCT result was available. PND showed the fetus to be unaffected by β-ureidopropionase deficiency. Previous offspring were tested and not affected.

For the six couples already enrolled in a PGT procedure where the PCT identified one or more additional disease carrier state, two (couples 4 and 22) decided to discontinue PGT, whereas four couples (2, 51, 82, 85) opted to add the additional disease risk to the PGT procedures. Couple 16 (GAA and ZMPSTE24) underwent PND for Pompe disease and lethal restrictive dermopathy. The fetus was affected by Pompe disease but not by restrictive dermopathy. The pregnancy ended spontaneously before a termination. In a subsequent pregnancy PND for both diseases showed that the fetus was affected by lethal dermopathy and the pregnancy was terminated. The couple is now opting for PGT for both disorders. Couple 82 (MYL2 and IGHMBP2) tested their deceased and their healthy daughter for the IGHMBP2 variant identified by PCT. Both were shown to be unaffected; the healthy daughter is heterozygous for the variant, the deceased daughter was not. Couple 85 (RMND1 and NEB) had their children, who were affected by combined oxidative phosphorylation deficiency 11, tested for nemaline myopathy, which one deceased and one living child were shown to have (had) as well (homozygous for the variant). Their healthy son (RMND1 heterozygote) does not carry the NEB variant. Couple 96 (OTOG) was pregnant when receiving the PCT result and did not opt for PND. The baby was tested postpartum and shown to be homozygous for the OTOG variant, and indeed deaf.

Correlation between degree of consanguinity and number of shared variants

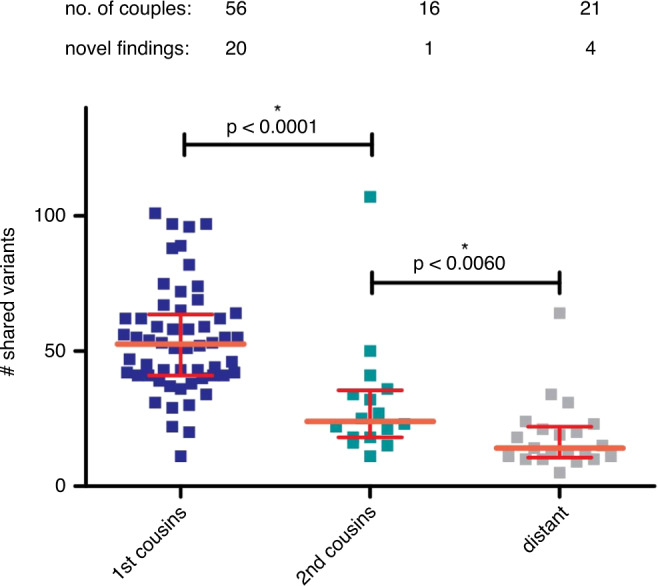

Unsurprisingly, we observed a correlation between an increasing degree of consanguinity and the number of identical variants shared between partners (Fig. 3). Of the 100 couples, 56 are first-degree relatives with an average of 54 shared identical variants. The 16 second cousin relationships shared on average 31 identical variants. Statistical testing (Mann–Whitney nonparametric) shows that the difference between these two groups is significant (p < 0.0001). The third grouping of 21 couples with a consanguineous relationship that is more distant than second cousins showed an average of 18 shared identical variants. This is statistically significant (p < 0.06) compared with the second cousin group. Novel variants were detected in 20 of the 56 first cousin couples (35.7%), in 1 of the 16 second cousin couples (6.3%), and in 4 of the 18 couples in the distant group (22.2%).

Fig. 3. Correlation between degree of consanguinity and the observed number of identical variants shared between partners.

Distant: all degrees of consanguinity farther removed than 2nd cousins. Novel findings: number of couples in which preconception carrier testing (PCT) detected at least one novel carriership. Crossbars: median with interquartile range. *Significant two-tailed p value (given) in Mann–Whitney t-test.

DISCUSSION

We present the results of a diagnostic ES-based PCT in 100 consanguineous couples, showing that this test provides a powerful diagnostic tool for identification of AR disease carrier couple status. Outcomes provide significant reproductive choices for a higher proportion of consanguineous couples than other diagnostic tests currently offer.

Not counting the 45 previously known carrier states, our PCT results in an overall diagnostic yield for 30 novel carrier states in 28 couples (28%). The high diagnostic yield confirms the feasibility of a broad, ES-based approach in consanguineous couples. To the best of our knowledge, to date, no comprehensive studies have been published that provide insight into the proportion of consanguineous couples carrying recessive disease. Our study demonstrates that a considerable proportion of consanguineous couples in our cohort are carrier couples. One may argue that the couples who had a child with an undiagnosed phenotype that in retrospect was explained by the PCT result should not be taken into account in this figure in order to reduce bias. Excluding these four couples results in 24 newly identified carrier couples (24%) in our series. Still this is a significant number, which we found even in a heterogeneous group with varying degrees of consanguinity. Stratifying the data set stringently, limited to couples meeting a more formal definition of consanguinity, i.e., relatedness of second cousins or closer,10 would have resulted in a higher yield/risk figure, as can be seen in Fig. 3. Our data suggest that the empiric consanguinity-related health risk numbers used in genetic counseling may be an underestimation. However, our study is not a prospective study and bias can therefore not be excluded.

In total, 58/100 consanguineous couples in our series are carrier couples of at least one AR disease, 19 of which had already been included for PGT procedures.

As expected, the degree of consanguinity correlates with the absolute number of shared identical variants detected between partners in a couple. A more distantly related consanguinity results in significantly fewer shared variants but does not exclude a significant chance of identifying pathogenic carrier state.

The identification of two couples (2%) carrying a compound heterozygote disease risk demonstrates the potential for PCT application in the broader nonconsanguineous population and reflects a detectable disease risk based on population frequencies. Although compound heterozygous carrier states do not match the indication of consanguinity, they are obviously relevant to report, having the same relevance to the couples in terms of recurrence risk and reproductive choices as do homozygous carrier states.

In four couples PCT provided a genetic likely diagnosis for an affected, sometimes deceased, previous child, illustrating the potential usefulness of PCT in diagnosing deceased children without diagnosis (usually due to lack of available DNA of these deceased children).

Seven carrier states were not (initially) identified, mainly for technical reasons or due to unpublished literature at the time. Our PCT design builds on our previously implemented routine ES diagnostics,19 which because of technical limitations cannot guarantee 100% coverage of all exons of all genes and has a degree of mapping and alignment issues. Custom analysis depends on variant filter design that, for instance, limits analysis to positions +8 and −8 at exon–intron boundaries, excluding detection of deep intronic pathogenic variation. Performance limitations applying to ES in general may cause carrier state to elude the test. This is the reason a separate MLPA test for SMA is performed until validation of the SMN1 exon 7–8 deletion detection in exome sequencing data can be completed (in progress). Such limitations are also the reason why, for example, HBA1 and HBA2 are excluded from our panel (couple 34), warranting separate ɑ-thalassemia testing in high-risk20 couples. Future developments will need to overcome these limitations.

Our panel design relies on well-defined genetic AR disease consensus as registered in OMIM and adequate and timely gene panel management. Any gene panel based approach requires continuous updating and curation, as is the case for our panel, but still has limitations. As illustrated in the series presented here, very recently discovered new causative disease genes that have not yet been registered in OMIM may be missed. The same applies to pathogenic variants that at the time of analysis are not yet reported in the literature or included in databases such as the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD).

The conceptual design of our test currently excludes CNV detection and AD and X-linked disease, although future directions in preconception health care may warrant inclusion.

Since we include virtually all known AR disease genes, the far higher diagnostic yield when compared with currently available PCS strategies (personal communication), working with small to medium-sized gene panels, is unsurprising.21–23 Our approach to include the highest possible number of disease-related genes was intentional, in order to maximize sensitivity in consanguineous couples who are at increased risk for any, including ultrarare, AR disorders.

In the context of PCS in general, focusing on severe diseases with childhood onset has been recommended in a statement of the European Society of Human Genetics (ESHG)24 and adopted by a national guideline, although the latter deliberately discourages categorical definitions of severe versus less severe. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) proposes the following criteria for disease inclusion in a PCT: carrier frequency of >1 in 100, well-defined phenotype, detrimental effect on quality of life, cognitive or physical impairment, requiring surgical or medical intervention, early onset in life and exclude late onset disease, availability of intervention opportunities that result in improved outcomes, and education of parents about special care needs after birth.25 For a recently published selection of 1,300 genes for an Australian PCS project (Mackenzie’s Mission) the following inclusion criteria were applied: a condition should be life-limiting or disabling, with childhood onset, such that couples would be likely to take steps to avoid having an affected child; and/or be one for which early diagnosis and intervention would substantially change outcome.26 Of note, criteria may be (partly) different for general population screening panels compared with a PCT limited to consanguineous couples, which we present here. For example, for the very rare diseases that are more likely to be identified in consanguineous couples, a well-defined phenotype often is not available, as in many examples only one or a few cases have been described. This may, at least partially, explain why several genes in which carrier states were identified in our couples are not included in the Mackenzie’s list although they meet their abovementioned criteria (e.g., carnitine-acylcarnitine translocase deficiency [SLC25A20, OMIM 212138] and lethal congenital contracture syndrome [NEK9, OMIM 617022]): an additional selection criterion in the Mackenzie’s list is strong evidence that variants in the gene are associated with the condition in question.26 MRPL44 (combined oxidative phosphorylation deficiency 16, OMIM 615395) and SCAPER (intellectual developmental disorder and retinitis pigmentosa, OMIM 618195) were not assessed by them and therefore not included, illustrating the difficulties in being as complete as possible despite an approach as thorough as theirs. Another potential challenge in testing consanguineous couples is that a pathogenic variant has been described in compound heterozygosity with another pathogenic variant, but never in a homozygous state. In such cases pathogenicity may be likely or evident but the phenotypic consequences less so. For our gene panel design, instead of making extensive choices based on interpretations of severity at the start, we opted to evaluate panel genes twice a year. In the first update we removed genes with unclear or very mild phenotypes, in later updates we mainly added novel AR genes described in literature (Suppl. Table S2).

The vast majority of carrier couple states we identified are indeed associated with serious disease, having impact on quality of life, causing impairment and/or requiring interventions, and with onset generally at infancy or early childhood (Table 1, Suppl. Table S3), thus meeting the ESHG criteria.

The classification of severity of disease has an inherent subjectivity27 and will remain controversial, particularly so in the context of PCT and reproductive (preventive) medicine. Local considerations rooted either in national law or cultural and social differences, are all codeterminants in the degree of severity definition, as is the actual availability of downstream preconception and/or prenatal diagnostic options in different parts of the world. Frequent gene panel updates based on expert consulting in our experience is an adequate tool for continuous re-evaluation and correction. For instance, the HFE gene (hemochromatosis type 1, OMIM 235200), initially included in the earliest version of the PCT gene panel, was reconsidered when actually encountered in an ongoing PCT analysis and, in a subsequent round of gene panel curation, was removed because of the adult onset and low penetrance characteristics of the associated pathology.

Other examples of the severity issue have been, e.g., congenital hearing loss or visual problems such as retinitis pigmentosa. Of note, AR congenital hearing loss caused by, for example, GJB2 variants (DFN1B, OMIM 220290) is often categorized as moderately severe and not meeting several of the criteria discussed above.28 Still, in our center for PGT, it is one of the most frequently requested PGT indications (PGDnederland), adding patient experiences into the mix on the matter of disease severity opinion. One of the “mildest” disorders identified in our cohort was probably familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) (couple 66, Table 1, Suppl. Tables S1/S3). Although often with childhood onset, and potentially serious health complications, reproductive options will generally not be offered for FMF mainly due to its treatability. Ichthyosis vulgaris (couple 71, Table 1, Suppl. Tables S1/S3) is another debatable disorder in terms of severity, although the associated recessive disease has a more severe phenotype than dominant disease and PGT for other type congenital ichthyosis has been performed in our center, taking the treatment burden into consideration.

Once a couple is aware of their genetic risk(s), they can opt for reproductive choices such as refraining from having (further) children, accepting the risk, using donor gametes, or considering PND and PGT to avoid the birth of an affected child. Finally, couples may use the information to optimally prepare themselves for the birth of a potentially affected child, including choices for pre- and postnatal interventions to optimize outcome where applicable. The diverse options are illustrated by our follow-up data so far. Many couples testing positive for recessive disease carrier state in PCT will not have experience with the disease in their families, complicating their informed decision-making regarding available reproductive options.29 PCT-specific genetic counseling is essential and we have instigated several lines of clinical follow-up to aid in the development and improvement of these approaches. The lack of availability of an affected individual, currently needed for the development of a PGT laboratory protocol,30 requires development of novel PGT approaches. We and others are developing methods to directly phase the parental genomes, circumventing this requirement. Recently, PGT has already moved to genome-wide methods,30–32 allowing embryo analysis for multiple genetic defects with a single test instead of requiring multiple workups and analyses. This is clearly relevant in the context of consanguineous couples. Obviously, performing PGT for multiple disorders will yield a lower number of transferable embryos, potentially resulting in clinical and ethical dilemmas.33

Naturally, couples’ opinions about the PCT and the quality of PCT-related counseling and (after-) care is of eminent importance. We are currently conducting an extensive clinical follow-up study including in-depth interviewing techniques to gain more insight in this matter and aid in the adaptation of counseling practices.

Conclusion

The results presented here show the clinical feasibility and utility of our ES-based comprehensive PCT approach for consanguineous couples. The high diagnostic yield emphasizes the benefit of including almost all AR disease genes, identifying the very rare carrier states consanguineous couples are particularly prone to. Recognizing their shared carrier status is of significant clinical importance for these couples, allowing them a well-informed reproductive choice. Our results open up avenues to future applications for this approach within the expert environment of clinical genetics. Extensive pretest counseling is essential.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank all the couples who consented to the use of their data for this study. We thank all the clinicians/clinical geneticists from clinical genetic centers in the Netherlands who referred the couples to our center.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: S.S., A.P.A.S., A.P. Formal analysis: C.V., A.S., M.v.E., A.P.A.S., A.P. Software: B.d.K., C.G. Writing—original draft: S.S., A.P.A.S., A.P. Writing—review & editing: S.S., A.P.A.S., B.d.K., C.V., A.S., M.v.E., P.L., H.Y., M Z.E., C.d.D.-S., C.G., A.v.d.W., H.B., A.P.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author (A.P.). The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Ethics declaration

We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations. The local Medical Ethical Committee (Maastricht University Medical Center+ [MUMC+]) provided guidelines for study procedures. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Suzanne C. E. H. Sallevelt, Alexander P. A. Stegmann.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41436-021-01116-x.

References

- 1.Bell CJ, et al. Carrier testing for severe childhood recessive diseases by next-generation sequencing. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011;3:65ra64. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gulani, A. & Weiler, T. Genetics, autosomal recessive. (Treasure Island, FL, StatPearls, 2020). [PubMed]

- 3.Fareed M, Afzal M. Genetics of consanguinity and inbreeding in health and disease. Ann. Hum. Biol. 2017;44:99–107. doi: 10.1080/03014460.2016.1265148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennett RL, et al. Genetic counseling and screening of consanguineous couples and their offspring: recommendations of the National Society of Genetic Counselors. J. Genet. Couns. 2002;11:97–119. doi: 10.1023/A:1014593404915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kahrizi K, et al. Effect of inbreeding on intellectual disability revisited by trio sequencing. Clin. Genet. 2019;95:151–159. doi: 10.1111/cge.13463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oniya O, Neves K, Ahmed B, Konje JC. A review of the reproductive consequences of consanguinity. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2019;232:87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamamy H. Consanguineous marriages: Preconception consultation in primary health care settings. J. Community Genet. 2012;3:185–192. doi: 10.1007/s12687-011-0072-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hussain R. Community perceptions of reasons for preference for consanguineous marriages in Pakistan. J. Biosoc. Sci. 1999;31:449–461. doi: 10.1017/S0021932099004496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaw A. Drivers of cousin marriage among British Pakistanis. Hum. Hered. 2014;77:26–36. doi: 10.1159/000358011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thain E, et al. Prenatal and preconception genetic counseling for consanguinity: consanguineous couples’ expectations, experiences, and perspectives. J. Genet. Couns. 2019;28:982–992. doi: 10.1002/jgc4.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Modell B, Darr A. Science and society: genetic counselling and customary consanguineous marriage. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2002;3:225–229. doi: 10.1038/nrg754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bittles A. Consanguinity and its relevance to clinical genetics. Clin. Genet. 2001;60:89–98. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2001.600201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sallevelt S, de Koning B, Szklarczyk R, Paulussen ADC, de Die-Smulders CEM, Smeets HJM. A comprehensive strategy for exome-based preconception carrier screening. Genet. Med. 2017;19:583–592. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boycott KM, et al. International cooperation to enable the diagnosis of all rare genetic diseases. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017;100:695–705. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eaton A, et al. When to think outside the autozygome: best practices for exome sequencing in “consanguineous” families. Clin. Genet. 2020;97:835–843. doi: 10.1111/cge.13736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Ligt J, et al. Diagnostic exome sequencing in persons with severe intellectual disability. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367:1921–1929. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1206524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilissen C, et al. Genome sequencing identifies major causes of severe intellectual disability. Nature. 2014;511:344–347. doi: 10.1038/nature13394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richards S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015;17:405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lelieveld SH, et al. Meta-analysis of 2,104 trios provides support for 10 new genes for intellectual disability. Nat. Neurosci. 2016;19:1194–1196. doi: 10.1038/nn.4352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piel FB, Weatherall DJ. The alpha-thalassemias. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:1908–1916. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1404415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beauchamp KA, Johansen Taber KA, Muzzey D. Clinical impact and cost-effectiveness of a 176-condition expanded carrier screen. Genet. Med. 2019;21:1948–1957. doi: 10.1038/s41436-019-0455-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoffman JD, et al. The Ashkenazi Jewish carrier screening panel: evolution, status quo, and disparities. Prenat. Diagn. 2014;34:1161–1167. doi: 10.1002/pd.4446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bristow SL, et al. Choosing an expanded carrier screening panel: comparing two panels at a single fertility centre. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 2019;38:225–232. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2018.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henneman L, et al. Responsible implementation of expanded carrier screening. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2016;24:e1–e12. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romero S, Rink B, Biggio JR, Saller DN. Carrier screening in the age of genomic medicine. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017;129:E35–E40. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirk EP, et al. Gene selection for the Australian Reproductive Genetic Carrier Screening Project (“Mackenzie’s Mission”) Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2020;29:79–87. doi: 10.1038/s41431-020-0685-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lazarin GA, Haque IS. Expanded carrier screening: a review of early implementation and literature. Semin Perinatol. 2016;40:29–34. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lazarin GA, Hawthorne F, Collins NS, Platt EA, Evans EA, Haque IS. Systematic classification of disease severity for evaluation of expanded carrier screening panels. PLoS One. 2014;9:e114391. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vaz-de-Macedo C, Harper J. A closer look at expanded carrier screening from a PGD perspective. Hum. Reprod. 2017;32:1951–1956. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drusedau M, et al. PGD for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer: the route to universal tests for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;21:1361–1368. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Masset H, et al. Multi-centre evaluation of a comprehensive preimplantation genetic test through haplotyping-by-sequencing. Hum. Reprod. 2019;34:1608–1619. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dez106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zamani Esteki M, et al. Concurrent whole-genome haplotyping and copy-number profiling of single cells. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2015;96:894–912. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van der Schoot V, et al. Preimplantation genetic testing for more than one genetic condition: clinical and ethical considerations and dilemmas. Hum. Reprod. 2019;34:1146–1154. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dez059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author (A.P.). The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.