Abstract

Gold mining is one of the major problems of contamination of hydric resources in Colombia, this practice generates a high impact on water quality due to the accumulation of waste during its process. In this study water quality was evaluated in five natural stream beds corresponding to four streams with gold mining operations and one in the Cauca River, taking samples before the water inlet and after the outlet in each operation in the streams of Dios Te Dé, Tamboral, Piedra Imán, and Lorenzo affected by artisanal gold mining labor, which drain into the Salvajina Reservoir on the Cauca River in the municipality of Suárez Cauca, Colombia. Characterization of water bodies in the streams was carried out applying contamination indices of Colombia. The IDEAM protocol was used as guide to monitor the water currents. Samples were taken in 15 stations in the natural stream beds with operations and a sampling station on the Cauca River after the reservoir in these lotic ecosystems, during three periods; two from 2018 and one from 2019. The range of the contamination indices according to the environmental variables were considered. Results show that the contaminants associated with TSS, TUR, and Hg are high in the sampling stations in the output of the operations and the sampling stations of the streams with influence on the operations (T3, T4, I2, I3, D2, and D5). The water quality score according to the ICA IDEAM index varied between acceptable and regular in the different sampling stations. However the Hg concentration in sampling station C1 of the Cauca River is due to contributions from the operations in the amalgamation process. This requires strategic interventions by the communities, miners, operation owners, and control organisms as the Regional Autonomous Corporation of Cauca (CRC) and the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development (MADS) to minimize the negative impacts on the hydric resource and ecosystemic services associated with this resource.

Keywords: Water quality indices, Artisanal gold mining, Streams, Operations, Mercury, Physical-chemical variables

Water quality indice; Artisanal gold mining; Streams; Operations; Mercury; Physical-chemical variables

1. Introduction

1.1. Artisanal gold mining

Artisanal and small-scale mining continues growing in many rural communities rich in mineral resources. Recent estimations highlight this growth, thus: 40.5-million people participated directly in 2017; up to 30-million in 2014; 13-million in 1999; and 6-million in 1993 (IGF, 2017). In Colombia, participation in the artisanal gold mining activity has 200000 miners who produce officially 30 tons of Au (Cordy et al., 2011). It is considered that gold exploitation, according to recent estimations release up to 1600 tons of elemental mercury (Hg) per year onto the planet (Black et al., 2017; Rajaee et al., 2015), inducing the alteration and affectation of ecosystemic services associated with the supply, principally of the hydric resource and changes in soil use, removing the edaphic horizons and depositing the rocky material from mine openings; residual sludge and sand from the operations are thrown directly into hydric sources. This rocky and sandy material is formed by mineral compounds that contain metals, like iron (Fe) in form of (magnetite, pyrite, and siderite), Manganese (Mn) (pyrolusite, magnesite), chromium (Cr) (chromite), cadmium (Cd) (otavite), lead (Pb) (galena, litharge), and arsenic, (As) (arsenopyrite), among others (Ramanaidou et al., 2015; Scarpelli, and Horikava, 2018; Gutiérres-Mosquera et al., 2018).

1.2. Mercury and amalgamation

Mercury is found in natural (e.g., volcanoes, soil, and ocean), degassing, and anthropogenic sources (e.g., industry, fuel, and coal combustion). Globally, artisanal gold miners are the principal users of mercury, using and wasting nearly 1000 tons of metallic Hg per year, which corresponds to >30% of all the Hg used annually by different industrial applications (See Appendix A) (Swain et al., 2007). Among the anthropogenic activities, small-scale artisanal gold mining uses Hg for Au recovery, which has been identified as a source of Hg contamination, affecting the atmosphere, rivers, and people (PENUMA, 2018; Wade, 2013). For PENUMA (2018), the impact of Hg comes from a broad variety of sources propitiating due to its characteristics toxicity, mobility, and a tendency to biomagnification on land and aquatic ecosystems (Horvat, 2002). The artisanal gold mining sector can contribute with approximately 15% of the total global emissions of Hg (AMAP/UNEP, 2019). Numerous studies expose that transport of contaminants through the soil depends on the physical-chemical characteristics of the contaminant, site, type of soil, soil heterogeneity, geochemistry of the environment, and moisture content (Reis et al., 2014). Various studies in South America have reported dramatic Hg contamination of ecosystems in the proximities of the sites of artisanal gold mining, where Hg is used to process it (Roulet and Lucotte, 1995; Silva-Filho et al., 2006; Grimaldi et al., 2008; Balzino et al., 2015; Diringer et al., 2015).

Mercury contamination in Colombia due to artisanal gold extraction has been recognized by various researchers and local authorities for over a decade (INGEOMINAS, 1995; Veiga, 1997; Veiga, 2010; Olivero et al., 2002; Marrugo-Negrete et al., 2008). Estimates by Telmer and Veiga (2008) on annual Hg emissions due to artisanal gold mining in Colombia for 2007 were calculated between 50 and 100 tons; however, given the recent value and growing activity of artisanal gold mining, current Hg must be much higher than that reported by 2007. Colombia is probably the third country globally with highest source of Hg emissions due to artisanal gold mining after China (240–650 tons of Hg/year) and Indonesia (130–160 tons of Hg/year) (Telmer and Veiga, 2008). The World Gold Council, 2011 established (UPME, 2014; Díaz-Arriaga, 2014) that Colombia imports 101.3 tons/year and the volume used in gold mining is of 75 tons/year; based on customs import registries by DIAN reported by Legiscomex, between 2003 and 2013 the country imported 1020 tons of Hg (UPME, 2014), which represents an average of 102 tons of Hg/year; however, it is possible that the figures have been over-registered according to the requirement by the Delegate Superintendence of Ports and Transportation (Superintendencia Delegada de Puertos y Transportes) to Dirección Nacional de Impuestos y Aduanas Nacionales DIAN (2013). Mercury exists in various forms, with elemental (Hg0), inorganic (Hg2+) and organic species, probably constituting the chemical agent most potentially dangerous to man, given that it cannot be decomposed or degraded into inoffensive substances (PENUMA, 2002).

The presence of heavy metals in soils that are product of cyanidation and amalgamation tailings generated in gold exploitation, like pyrites (Sulphur and iron), galena (lead) cadmium and arsenopyrites (arsenic) are highly toxic. It has been established that inorganic as is a potent human carcinogen (IARC, 2004) for the bladder, lungs, and skin, with risks for the liver, kidneys, and prostate (Ardini et al., 2019). Its oral ingestion through water causes various diseases, such as peripheral vascular problems, hypertension, respiratory difficulties, neurological disorders, hepatic diseases, and diabetes mellitus (IARC, 2004; WHO/IPCS, 2001). The first effects of exposure to as by drinking contaminated water includes changes in pigmentation and hyperkeratosis which, according to reports, appear after 5–10 years of exposure (Rahaman et al., 2006a, 2006b), and in last instance causes health effects. It can cause death due to its capacity to coagulate proteins, form complexes with coenzymes, and inhibit production of adenosine triphosphate in essential metabolic processes (Fowler et al., 2015).

1.3. Physical-chemical variables and water quality in hydric sources

In the high basin of the Cauca River, the Salvajina Reservoir, constructed on the basin of the Cauca River in the municipality of Suárez, Cauca, is an important source of hydroelectric power generation with a capacity of 764,7 hm³; it is located at 1155 masl and its construction was completed in 1985, with hydroelectric generation of 270 Mw. The medium flow of the Cauca River in la Balsa station 27 km downstream from the reservoir is 176.7 m3 s−1, and this source is the principal water supply for the city of Cali with 2,5 million inhabitants. This condition makes relevant this study of small-scale gold mining exploitation carried out before the city of Cali on the eastern slope of the western cordillera of the Salvajina Dam due to the artisanal gold mining activities carried out in this area negatively affect the quality of the water.

Colombia is characterized for having a hydric potential greater than other countries in South America and, even so, has problems of good quality water availability in different regions of the country, especially those heavily populated (Gualdrón-Durán, 2016; González-Márquez et al., 2018). This is because production activities specially mining and industry cause residual waters generates negative effects in quality of surface water bodies (Chán-Santisteban and Peña, 2015), given that their residues are environmentally dangerous and can persist over time after the cessation of this activities (Johnson, 2003; Younger, 2004; Wright and Ryan, 2016).

The variety in data on physical, chemical, and biological variables of water quality permits using water quality indices that represent the general quality of surface or groundwater during a given time; it incorporates data from multiple physical, chemical, and biological parameters into a mathematical equation, through which quality state of a water body is evaluated (Yogendra and Puttaiah, 2008; Barakat et al., 2016; Ewaid and Abed, 2017; Zeinalzadeh and Rezaei, 2017; Tripathi and Singal, 2019) and permits determining the vulnerability of the body of water against potential threats (Soni and Thomas, 2014). Initially, such were proposed by Jacobs et al. (1965) and Brown et al. (1970); the latter developed the Water quality index by the National Sanitation Foundation (NSFWQI, or simply WQI (National Sanitation Foundation), which evaluates nine parameters that include saturation percentage of dissolved oxygen (DO), pH, total solids (TS), five-day biochemical oxygen demand (BOD5), turbidity (TUR), total phosphate (PT), nitrate (NO3), change of temperature (TEM), and fecal coliforms (FC); each has an individual weight proportional to the impact and importance in the model by the NSFWQI (Brown et al., 1970; Benouara et al., 2016; Noori et al., 2018). From this, diverse studies have been conducted using quality indices globally (Tripathi and Singal, 2019; Şener et al., 2017; Tomas et al., 2017; Grey et al., 2014; Sierra, 2015). In this respect, quality indices are instruments to transform large amounts of water-quality data into a number, range, verbal description, or symbols which describes the state of water quality (Torres et al., 2010; Sánchez et al., 2007; Bharti, 2011). Although specific contamination indices are also implemented to evaluate one or more variables that permit specifying environmental problems and delving into the contaminants that affect water (Ramírez et al., 1997). Their use generates technical and reliable information that contributes to managing hydric resources (Restrepo-Valencia, 2015; Mosquera-Chaverra, 2016; Chavarro and Gélvez-Bernal, 2016). The index that permits measuring contamination from gold mining is the ICOMINERO, the variables selected are turbidity, total suspended solids, and mercury. Mercury is a direct indicator of the impact of gold mining (Restrepo-Valencia, 2015).

In Colombia, the department of Cauca is of great hydric importance, given that it is part of the Colombian Massif; one of the principal sources is the Cauca River (Pérez-Valbuena et al., 2015), which feeds La Salvajina Reservoir constructed to produce hydroelectric power, control floods, transportation, recreation, and subsequently this water is used for irrigation and potable water. The department of Cauca also has various anthropic activities among which there is gold mining (Defensoría del Pueblo, 2015), an activity that contaminates the hydric resource through introduction of heavy metals, like mercury, lead, arsenic, cadmium, chromium and other chemical substances, like sodium cyanide, chlorhydric acid, calcium oxide, and cement among others. These activities associated with artisanal gold mining generate environmental disturbances due to the contaminants, which are spread in the environment and results in air, soil, and water contamination problems (Li et al., 2017). Mercury-based gold extraction processes that prevail in small-scale mining using rudimentary technology that, although ensuring relatively high gold recovery levels, cause environmental and health problems (Jønsson et al., 2009). Using Hg to improve gold (Au) and silver (Ag) recovery through amalgamation has resulted in generalized Hg contamination of aquatic systems in many parts of the world (See Appendix B) (Alpers et al., 2016). This study evaluated the water quality of the streams Dios Te Dé, Guayabilla, El Desquite, Tamboral, Piedra Imán, and Lorenzo, which are part of four microwatersheds where gold mining activities are conducted (pitheads and operations), where small townships are also associated that also drain into the streams, which then reach La Salvajina Reservoir.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study area

This work studied the microwatersheds of La Lorenzo (La Chorrera), Piedra Imán, Tamboral, and Dios Te Dé Streams, located in the submunicipalities (veredas) of La Turbina, Miravalles, El Tamboral, and Maravélez de Mindalá to the southeast of the municipality of Suárez, Cauca (Colombia). The study zones are at 2,186, 1,921, 1,659, and 1,794 m.a.s.l, respectively, and the terrain slopes range between 15° and 45°. The Cauca River was studied with a sampling station after La Salvajina Reservoir. The study area was defined for being the principals microwatersheds and geomorphological units in the sector influenced by artisanal gold mining activities (Figure 1), this activity is considered one of the most important in this zone of the municipality, exploitation of the mineral (vein gold) takes place underground in artisanal manner and with scarce technical level (CRC, 2006a).

Figure 1.

Location of sampling stations in the rural zone of the municipality of Suárez Cauca.

2.2. Selection criteria

Sampling station selection (Figure 1) was based on field observations, as well as the criteria of access and representation of the samples related with pressures of use. For the Lorenzo Stream (La Chorrera), two sampling stations were placed (L1 and L2); L1 was located on the construction of the water catchment infrastructure to supply the vereda of La Turbina and the municipality of Suárez, station L2 was located 50 m before the stream flows into La Salvajina Reservoir.

Three sampling stations were selected for the Piedra Imán Stream (I1, I2 and I3); sampling stations I1 and I2 were located at a distance of 2.0 km and 1.3 km from the river mouth to La Salvajina Reservoir, where station I3 was placed. The Tamboral Stream had four sampling stations (T1, T2, T3 and T4); station T1 was located on the intake of the aqueduct for the Tamboral vereda, downstream, at 1 km distance, T2 station was established; due to the confluence with El Canelo Stream, it was necessary to place station T3. Lastly, station T4 was located 50 m before the river mouth to the La Salvajina Reservoir. Finally, five sampling stations were defined for the Dios Te Dé Stream (D1, D2, D3, D4 and D5): D1 was placed on the source of the Dios Te Dé Stream, station D2 was placed 3.2 km downstream from station D1; D3 was placed on La Guayabilla Stream, D4 on the Desquite Stream, D5 where the three streams join to flow into to La Salvajina Reservoir and, lastly, a sampling station was placed on the Cauca River (C1) 200 m from the municipality's main bridge to compare the values of the physical-chemical variables. Five operations were also evaluated to know the pollutant load these contribute to the river system in gold extraction processes.

2.3. Sample collection and data analysis

Three samplings were carried out, one in the month of May 2018, October 2018 and May 2019, each in triplicate, these dates were selected to facilitate sampling in times of little rain. The geographic coordinates of the sampling locations are presented in Appendix D.

2.3.1. In-situ and laboratory analysis

The water samples were collected in triplicate and in sterilized polypropylene jars with 1-L volume capacity, according with the guide for collection of waste water samples of the Institute of Hydrology, Meteorology and Environmental Studies in Colombia (IDEAM, 2007). These were transported in thermoses with ice and brought to the GIQA laboratory at University of Cauca to be stored (5 °C) until their analysis (IDEAM, 2005; IDEAM, 2007). Parameters of dissolved oxygen (DO), temperature (TEM), pH, electrical conductivity (EC), and turbidity (TUR) were measured in situ with a previously calibrated multi-parametric probe (HQ40d). For TUR, a portable turbidimeter (HACH 2100P) was used. The Hg analysis was performed through atomic absorption spectrophotometry with the cold vapor technique for water in Thermo Scientific equipment, series ICE 3000, for Hg vaporization system, VP 100, at 253.7-nm wavelength. Sample treatment was conducted through digestion with nitric acid, sulphuric acid, and potassium permanganate. The methods used in this work are listed in Appendix C.

2.3.2. Calculation of quality indices and contamination indices

Data were compared individually and behavior patterns were observed through a principal components analysis (PCA), using First software V7.0. Additionally, these were integrated through the NSFWQI (National Sanitation Foundation Water Quality Index), adapted for Colombia (IDEAM, 2011). This consists in evaluating, through physical-chemical parameters, the water quality of a surface current by classifying quality into five categories, based on the measurements obtained for a set of five variables. The variables used were DO, chemical oxygen demand (COD), total suspended solids (TSS), electrical conductivity (EC), pH, and biological oxygen demand (BOD5) (Castro et al., 2014; IDEAM, 2011). The data presented by the indices can be summarized and not detailed information (Torres et al., 2010); hence, contamination indices are implemented for specific physical and chemical variables, which assign a value of quality (0–1), depending on the concentration of the variables (Ramírez et al., 1997); among these, there are the mineralization contamination index (ICOMI) expressed in conductivity, hardness (T HARD), and alkalinity variables (ALKAL) (Ramírez et al., 1997). The organic matter contamination index (ICOMO) included the parameters of biological oxygen demand (BOD5), chemical oxygen demand (COD), total coliforms (TC), and fecal coliforms (FC) (Ramírez et al., 1997). The suspended solids contamination index (ICOSUS) was determined through the concentration of suspended solids (Ramírez et al., 1997). The pH contamination index (ICOpH) was determined through the pH variable (Ramirez and Cardeñosa, 1999). Likewise, others have been adapted, depending on the type of contaminant; one of these, the gold mining contamination index (ICOMINERA), included the turbidity, total suspended solids, and mercury (Hg) parameters proposed by Restrepo-Valencia (2015) and used by several authors (Mosquera-Chaverra, 2016; Abadía and Ossa, 2018) (Table 1, Eqs. (1), (2), (3), (4), (5), and (6)).

Table 1.

Formula to calculate water quality indices and contamination indices.

| INDEX | FORMULA | REFERENCE |

|---|---|---|

| ICA IDEAM Eq. (1) | (IDEAM, 2011; Caho-Rodríguez and López-Barrera, 2017; Castro et al., 2014) | |

| ICOMO Eq. (2) | (Ramírez et al., 1997; Valverde-Solís et al., 2015; Chavarro and Gélvez-Bernal, 2016; Samboni et al., 2007; Martinez-Ortiz and Barrero-Arias, 2018; Mosquera-Chaverra, 2016) | |

| ICOSUS Eq. (3) | (Ramírez et al., 1997; Valverde-Solís et al., 2015; Chavarro and Gélvez-Bernal, 2016; Samboni et al., 2007; Mosquera-Chaverra, 2016) | |

| ICOMI Eq. (4) | (Ramírez et al., 1997; Valverde-Solís et al., 2015; Chavarro and Gélvez-Bernal, 2016; Samboni et al., 2007; Martinez-Ortiz and Barrero-Arias, 2018; Mosquera-Chaverra, 2016) | |

| ICOMINERA Eq. (5) | (Restrepo-Valencia, 2015; Mosquera-Chaverra, 2016) | |

| ICOpH Eq. (6) | (Ramirez and Cardeñosa, 1999; Samboni et al., 2007) |

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of physical-chemical variables

Table 2 presents the data obtained from the analysis of the physical-chemical variables and includes a station outside the reservoir downstream located 200 m before the bridge to Suárez on the Cauca River. This station was taken to have a reference of how water comes out of the reservoir. Water quality of the waterways studied (Figure 2) diminishes in terms of the TSS and TUR variables, as the water runs its course. Stations T3 and T4 obtained high TSS values (137.66 and 520.51 mg/L) and TUR values (224.22 and 416.34 NTU) respectively. Station D2 registered a TSS concentration of 188.88 mg/L. In general, the values obtained in the sampling stations L2, T4, I3, D5 are determined by the presence of crops, dwellings, and operations where the material is processed to obtain gold, which although not carrying out punctual dumping do reach the hydric source through surface runoff. Station C1 obtained values of 10.30 in TSS and 27.50 of TUR.

Table 2.

Average values (n = 3) of the physical-chemical variables evaluated in the 15 stations selected.

| Stream Variables | Stations | pH | TEM |

EC |

DO |

TUR |

CAUQ |

TSS |

BOD5 |

COD |

ALKAL |

T HARD |

TC |

FC |

Hg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (°C) | (μS cm−1) | (mg O2 L−1) | (NTU) | m3 s−1 | (mg L−1) | (mg O2 L−1) | (mg O2 L−1) | (mg CaCO3L−1) | (mg CaCO3 L−1) | NMP100 mL−1 | (μg L−1) | ||||

| Lorenzo | L1 | 7.67 | 22.03 | 67.79 | 7.36 | 11.50 | 0.13 | 3.93 | 1.36 | 27.39 | 8.65 | 18.05 | |||

| L2 | 7.68 | 23.37 | 72.15 | 7.37 | 16.60 | 0.12 | 6.40 | 4.07 | 41.64 | 8.61 | 21.56 | 37,860 | 617 | 0.155 | |

| T1 | 7.83 | 19.70 | 85.71 | 7.67 | 7.97 | 0.37 | 6.87 | 1.69 | 14.41 | 10.64 | 28.00 | ||||

| Tamboral | T2 | 8.36 | 19.59 | 102.10 | 7.52 | 9.12 | 0.48 | 7.40 | 2.50 | 43.44 | 11.77 | 36.64 | |||

| T3 | 8.10 | 21.02 | 123.36 | 7.59 | 224.22 | 0.22 | 137.66 | 2.72 | 65.66 | 11.31 | 40.99 | ||||

| T4 | 8.47 | 22.10 | 127.77 | 7.77 | 416.34 | 0.27 | 520.51 | 3.84 | 76.08 | 13.31 | 49.85 | 18,600 | 317 | 1.000 | |

| Piedra | I1 | 8.05 | 21.43 | 62.12 | 7.67 | 29.87 | 0.46 | 14.86 | 1.10 | 20.46 | 5.86 | 8.22 | |||

| Imán | I2 | 7.71 | 21.92 | 67.14 | 7.93 | 75.39 | 0.54 | 60.31 | 1.36 | 46.85 | 6.45 | 11.66 | |||

| I3 | 7.51 | 22.20 | 89.34 | 7.51 | 132.76 | 0.23 | 75.40 | 2.12 | 59.81 | 7.71 | 19.99 | 28,130 | 617 | 0.234 | |

| D1 | 8.21 | 22.50 | 99.24 | 6.16 | 47.04 | 0.03 | 7.67 | 4.80 | 7.20 | 5.19 | 14.15 | ||||

| Dios Te Dé | D2 | 8.36 | 22.46 | 358.67 | 7.52 | 62.16 | 0.06 | 188.88 | 4.73 | 13.09 | 17.00 | 146.19 | |||

| D3 | 7.77 | 21.93 | 75.26 | 7.82 | 18.00 | 0.15 | 9.48 | 3.90 | 6.53 | 6.92 | 20.89 | ||||

| D4 | 7.98 | 22.03 | 117.84 | 7.81 | 18.89 | 0.12 | 20.06 | 2.23 | 11.99 | 9.99 | 28.17 | ||||

| D5 | 8.36 | 21.90 | 194.53 | 7.54 | 53.81 | 0.18 | 61.06 | 1.52 | 13.06 | 11.23 | 47.36 | 18,000 | 317 | 0.094 | |

| Cauca River | C1 | 6.60 | 20.10 | 70.50 | 6.80 | 23.5 | 45.00 | 18.30 | 2.00 | 12.50 | 19.10 | 23.05 | 23,200 | 2,013 | 0.0025 |

Figure 2.

Classification of ICOs contamination index: (ICOpH, ICOSUS, ICOMO, ICOMI, ICOMINERA).

The pH value of the streams ranged between 7.51 for station (I3) and 8.47 units for station (T4) and for station C1 on the river it was 6.60 units, similar to the reported by Sierra (2015) and Adewumi and Ayodeji (2021) in streams affected by artisanal gold mining. Temperature values registered in the hydric sources varied from 19.59 (T2) to 23.37 °C (L2), the minimum values were obtained in sampling stations T1 and T2 on the Tamboral Stream, while the maximum values were obtained in stations D1 and D2 on the Dios Te Dé Stream. For station C1, temperature was at 20.10 °C similar to the reported by Martinez and Galera (2011); Chapman (1996) and Adewumi and Ayodeji (2021). With respect to conductivity, these vary between 62.12 μS cm−1 and 358.67 μS cm−1; the maximum value was registered in station D2, where mining-type discharges take place; in station C1, the value was 70.50 μS cm−1 similar to values reported by Roldán (2003); Sierra (2015); Ambarita et al. (2016) and Adewumi and Ayodeji (2021). The total hardness obtained in the streams was in a range from 8.22 mg CaCO3 L−1 (I1) to 146.19 mg CaCO3 L−1 (D2) and for the river, station C1 was at 23.05 mg CaCO3 L−1similar to the reported by Neira (2006) and Martinez-Ortiz and Barrero-Arias (2018).

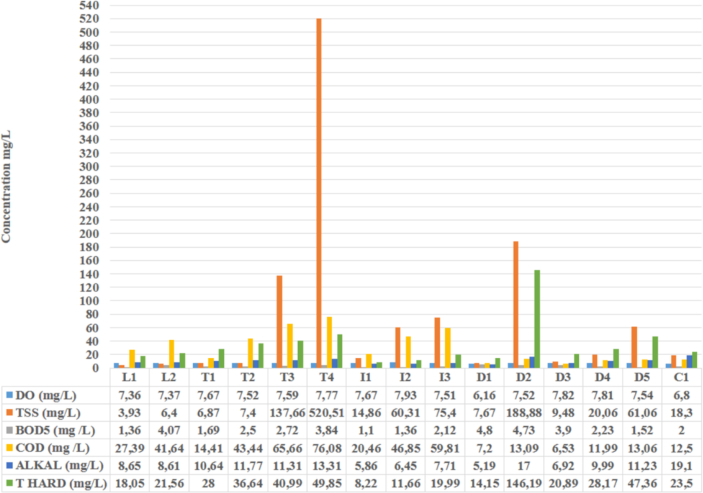

Some physical-chemical variables, like DO, BOD5, and COD behaved similarly in all the streams; the saturation percentage of DO was in all cases >100%, which indicates that these waters are oversaturated naturally, analogous to the reported by Effendi et al. (2015); Saksena et al. (2008) and Miyittah et al. (2020) also expressed in low BOD5 values in all the sampling points and only in L2, D1, and D2 exceed 4 mg L−1 of demand because, close to these stations, there is greater concentration of dwellings and higher number of gold mining workers (Chapman, 1996; Gualdrón-Durán, 2016). The COD evidenced a correlation with respect to BOD5, which indicates that the greatest part of the organic material is not biodegradable and is associated with the Tamboral and Piedra Imán microwatersheds (Mosquera-Chaverra, 2016; Barakat et al., 2016). The ALKAL values obtained in the streams varied between 5.19 mg CaCO3 L−1 (D1) and 17.00 mg CaCO3 L−1 (Cheremisinoff, 2002); the maximum value was reached in sampling station D2. The ALKAL values in the Piedra Imán (I1, I2, I3), Lorenzo (L1, L2), and Tamboral (T1, T2, T3, T4) streams showed a growing trend downstream toward the flow into the reservoir and the highest value was that in station C1 with 19.10 mg CaCO3 L−1. Figure 3 shows a consolidation of the concentrations of the DO, TSS, BOD5, COD, ALKAL, and T HARD variables, noting that in sampling stations T4, D2, and T3, the TSS contribution is high, as well as T HARD and COD due to the influence of the entables in these sampling stations where mud, sand from the rocky material with pyrite content, arsenopyrite, galena, chromite among others is generated; product of the milling and washing process in the barrels. This process generates a high turbidity when the discharge reaches the streams as observed in Figure 4 where in the station I3, T3 and T4 they exceed the values of 100, 200 and 400 (NTU) respectively (Sun et al., 2016; Zhen, 2010; Miyittah et al., 2020).

Figure 3.

Concentration consolidation of DO, BOD5, COD (mg O2 L −1) TSS (mg L −1) ALKAL, and T HARD (mg CaCO3 L−1) in streams and the Cauca River.

Figure 4.

Sampling stations of the operations.

Figure 5 displays the graphics of the variables: pH, temperature, turbidity, electrical conductivity, Hg concentration, fecal and total coliforms, and volumes of the streams and the Cauca River.

Figure 5.

Graphics showing values of the physical-chemical, microbiological, and volume variables of the sampling stations on the streams and Cauca River with presence of artisanal gold mining. (A) Turbidity values (NTU), (B) Temperature values (°C), (C) pH value, (D) electrical conductivity value (μS cm −1), (E) Hg concentration value (mg L−1), (F) TC and FC values (mg L−1), (G) Flows of the streams and Cauca River (m3 s−1).

The Hg concentration was monitored in stations L2, I3, T4, and D5, which are of closure of each microwatershed before entering La Salvajina Reservoir and which gathers the impacts of the gold processing plants that include Hg in their extraction process. The minimum value obtained was 0.094 μg L−1 in sampling station D5, while the maximum was 1,000 μg L−1 in sampling station T4 much higher than reported by Silva et al. (2020) and Gyamfi et al. (2021). In L2, no mining activities take place, however, cross-contamination has been observed by the miners who carry out personal cleaning of clothing and equipment. For station C1, Hg concentration was 0.0025 μg L−1 and this is located after the reservoir on the basin of the Cauca River. For TC and FC, the study followed the criterion of selecting closure stations of microwatershed, where it is observed that the FC concentration was low compared with TC in all the streams (Gualdrón-Durán, 2016). In station C1 there is a significant increase in the FC value of 2013 and the TC value was 23200, that according to WHO this values must be zero. The volumes of the streams are minimum compared with those of the Cauca River.

3.2. Principal components analysis

With respect to the PCA, Figure 6, Table 3 permits observing that the first component explains 40% of the variance, associated mainly with the mining activity of trituration and evacuation of SS that modify the ionic characteristics of the water column, expressed in changes of conductivity, alkalinity, and pH. These variables were more important in stations D2 and T4. Inversely, a group is noted forming stations L1 and L2 (Lorenzo microwatershed), which together with I1, T1, and D1, may be considered as control with respect to artisanal tailing activities. The second component explains 20.3% of the variance and relates the TUR variables of the water and COD, expressing aspects of contamination associated with the extraction process of rocky material, which is of inorganic nature with presence of metals (Bansah et al., 2016). Component 3 (17.9% of the variance) is associated with a variation in temperature, which is expressed by the differences in the altitude of the sampling stations; secondly, BOD5 appears as a relevant variable and which is possibly associated with the impacts on the populations generated around the mining activity and which have no treatment systems of the wastewaters that accumulated in the pond, once clogged, overflow to the fluvial systems.

Figure 6.

Principal components analysis.

Table 3.

Principal components analysis.

| PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variation (%) | 39.7 | 20.3 | 17.9 |

| Cumulative Variation (%) | 39.7 | 60.1 | 77.9 |

| pH | 0.43 | -0.21 | 0.13 |

| Temperature | 0.14 | 0.15 | -0.78 |

| Cnd | 0.51 | -0.32 | 0.02 |

| Turbidity | 0.40 | 0.54 | -0.06 |

| BOD5 | 0.32 | -0.17 | -0.45 |

| COD | 0.23 | 0.69 | 0.25 |

| Alkalinity | 0.47 | -0.20 | 0.32 |

3.3. Water contamination indices

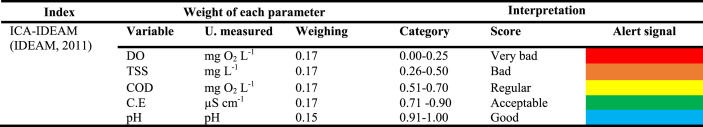

Regarding the water contamination indices, the results obtained by Noori et al. (2018); Chavarro and Gélvez-Bernal. (2016) and this study after applying the ICA IDEAM show their effect with diminished water quality in descending sense of the water course toward the reservoir. The lowest values occurred in stations T3, T4, I3 with regular values of (0,63), (0,55), and (0,69), respectively, for an average of 0,62 units. For the Lorenzo and Dios Te Dé streams, the value of the water quality index varied from 0.73 (D2) to 0,92 (D3) (acceptable and good), respectively. For station C1, the value was 0,77 acceptable (Figure 7). The categories and classification of the water quality of surface currents, according with the ICA IDEAM, are related with a color as alert signal and are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 7.

ICA IDEAM water quality index and ICOs contamination indices: (ICOpH, ICOSUS, ICOMO, ICOMI, ICOMINERA).

Figure 8.

Classification of ICA-IDEAM quality indices.

For the ICOSUS contamination index through TSS, the highest values were 1,00 (very high) and 0,64 (high) and occurred in stations T4 and D2, respectively. For station C1, it was 0,03 (none). The Organic Matter Contamination Index, ICOMO, was only evaluated in four stations of the streams and station C1 on the Cauca River and the values were medium class T4 (0,45), I3 (0,41), and L2 (0,45), while D5 (0,31) and C1 (0,39) had low contamination. The ICOMI Contamination Index (alkalinity, hardness, and conductivity) show, in general, low degree of contamination, except for station D2 (0,67) with (high) degree of contamination. With respect to the ICOMINERA, analogous to the reported by Ramírez et al. (1997) the results reflect, according to the scale (none) contamination in station C1 (0,12) due to the dilution factor because of the river's high volume. Station L2 (0,10) also had low mining activities; the same is observed for station D5 (0,18), where the mining processes take place in the highest part. Station I3 shows a medium degree of contamination with 0,43, while the highest degree of contamination was found in sampling station T4 (0,69), which reveals the effect of discharges from pitheads and operations in the zone (Table 2). The results obtained are interpreted according to Figure 2 and the results are shown in Figure 7.

3.4. Analysis of the physical-chemical variables of the operations

Table 4 shows the registries of the physical-chemical variables analyzed in two operations in the Maravélez vereda and three in El Tamboral vereda. Figure 4 shows the location of the sampling stations for the operations. The pH value of the stations for the operations ranged between 7,78 and 8,45 units in the inputs, Figure 9 (A), and 8,33 to 8,62 in the outputs, Figure 9 (B). The TEM values varied within a range from 20,4–22.1 °C in the inputs, Figure 9 (C) and 21,8 to 23,6 °C in the outputs, Figure 9 (D). This shows low variability of these variables among inputs and outputs. Nevertheless, clear differences are observed in the variables COND (76,1–127,9 μS cm−1 in the inputs, Figure 9 (E), and 128,1 – 337,4 μS cm−1 in the outputs, Figure 9 (F), DO (7,03–7,54 mg O2 L−1 in the inputs and 0,79–7,04 mg O2 L−1 for the outputs); TUR (12.7–51.2 NTU in the inputs and 122.67–29,216.3 in the outputs); TSS (7.3–72.3 mg L−1 for the inputs and 1,292.0–23,565.4 mg L−1 in the outputs); Figure 9 (G), (H) show the graphics corresponding to DO, TSS, and TUR of inputs and outputs of the operations, respectively. For Hg (0,054 to 0,325 μg L−1 for inputs and 0,508 μg L−1 to 10,265 μg L−1 in outputs, Figure 9 (I).

Table 4.

Physical-chemical parameters evaluated in the operations (input; o: output; average values for n = 3 T: Tamboral, M: Maravelez).

| STATIONS | Longitude | Latitude | masl |

pH | TEM |

EC |

DO |

TUR |

TSS |

Hg |

CAU |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m | (°C) | (μS cm−1) | (mg O2 L−1) | (NTU) | (mg L−1) | (μg L−1) | m3 s−1 | |||||

| Amargado (Input) | ET1input | 76°43′28,157″W | 2°55′22,822″N | 1180 | 8.45 | 21.5 | 108.7 | 7.54 | 51.2 | 67.8 | 0.305 | 1.327 |

| Cooperativa (Input) | ET2input | 76°43′24,68″W | 2°55′21,708″N | 1177 | 8.45 | 20.4 | 118.0 | 7.03 | 50.8 | 72.3 | 0.309 | 0.732 |

| Ronal (Input) | ET3input | 76°43′18,377″W | 2°55′19,498″N | 1040 | 8.23 | 20.7 | 127.9 | 7.34 | 50.4 | 71.0 | 0.325 | 1.152 |

| Arley (Input) | EM2input | 76°43′39,971″W | 2°54′54,205″N | 1492 | 7.90 | 22.1 | 126.3 | 7.39 | 15.8 | 7.3 | 0.060 | 1.255 |

| Hugo (Input) | EM3input | 76°43′27,682″W | 2°54′53,359″N | 1349 | 7.78 | 20.8 | 76.1 | 7.41 | 12.7 | 7.4 | 0.054 | 1.293 |

| Amargado (Output) | ET1output | 76°43′28,157″W | 2°55′22,822″N | 1180 | 8.44 | 21.8 | 128.1 | 6.94 | 5331.7 | 5145.0 | 4.338 | 1.480 |

| Cooperativa (Output) | ET2output | 76°43′24,68″W | 2°55′22,822″N | 1177 | 8.62 | 22.6 | 150.6 | 7.04 | 21591.7 | 6623.9 | 0.881 | 2.917 |

| Ronal (Output) | ET3output | 76°43′18,377″W | 2°55′21,708″N | 1040 | 8.54 | 22.4 | 156.2 | 4.99 | 29216.3 | 23565.4 | 10.265 | 1.882 |

| Arley (Output) | EM2output | 76°43′39,971″W | 2°55′19,498″N | 1492 | 8.33 | 22.0 | 337.4 | 0.94 | 122.0 | 1292.0 | 1.663 | 1.446 |

| Hugo (Output) | EM3output | 76°43′27,682″W | 2°54′54,205″N | 1349 | 8.52 | 23.6 | 191.4 | 0.79 | 168.9 | 2114.7 | 0.508 | 1.603 |

Figure 9.

Graphics showing values of physical-chemical variables of the wastewaters from operations where gold is obtained in inputs and outputs. (A) pH, (B) Temperature, (C) Hg concentration, (D) DO (mg O2 L−1), (E) EC, (F) TUR, (G) TSS.

4. Discussion

Water quality from the point of view of physical-chemical variables requires long-term monitoring that permits a vision of the annual and inter-annual seasonal behavior, nevertheless, a comparative vision with respect to sections or river sectors that are being impacted by some anthropic activity versus sectors not intervened can be a good tool to evaluate environmental effects as long as the reference zone is upriver from the focal point of contaminant emission. This study conducted a comparative approximation to assess the effects of artisanal gold mining, but which in functional terms have no differences in the gold extraction process, which includes the very mining activity; extraction, trituration, grinding, and amalgamation through mercury, washing of gold via gravimetry, while the sediments are evacuated to the streams and then onto the Cauca River.

The physical-chemical results show that sampling stations T1, T2, I1, and I2 were characterized for having acceptable water quality (Figure 7), are oxygenated and with pH close to neutral, except for station C1 on the basin of the Cauca River downstream after the reservoir, where pH is <7. Sampling stations T3, T4, and I3 were characterized as low quality waters (Figures 7 and 8) due to the influence of anthropic activities that contribute total suspended solids, turbidity, Hg, and other metals, which affect significantly the waters flowing into La Salvajina Reservoir.

pH is a measure of the hydrogen ion concentration in water; it is used to express the intensity of the acidic or alkaline condition of a solution, and is highly significant in all chemical reactions associated with the formation, alteration, and dissolution of minerals; with this being an essential characteristic, besides indicating total acidity or alkalinity. Variability of these values from one sector to another may have been influenced by different factors, like type of basin, order of the basin, the geological characteristics of the basing and mineral richness this has, which alters the hydrogen potential present in the water (Pérez, 2016). Biological activity, like photosynthesis and respiration and physical phenomena, like induced turbulence and concomitant aeration influence pH regulation through their respective abilities to decrease or increase dissolved carbon dioxide concentrations (Werner and James, 1981).

According with resolution 2115 of 2007 (MADS, 2007), by means of which characteristics, basic instruments and frequencies of the control and surveillance system for the quality of water for human consumption are indicated, the results obtained were within the recommended range from 6,5 to 9,0 units, acceptable for human consumption; likewise, water is considered suitable for the existence of aquatic life by being in the range from 5,0 to 9,0 units. Stability regarding this parameter in the system was due mainly to the good buffer capacity given by the alkalinity and a good recovery level of the system without drastic pH variations (Mamian and Zamora, 2016).

Temperature is one of the most significant variables in the bodies of water, it serves as indicator of the system's ecological stability. Variations in this parameter generate change in the development environment of fauna and flora present in the bodies of water, increasing the toxic potential of certain dissolved substances (Gualdrón-Durán, 2016). Electrical conductivity measures the total amount of ions present in water and, hence, is related with salinity. It indicates the water's capacity to transfer an electrical current, which increases principally with ion content (dissolved solids) and temperature (Roldán, 2003). Results in the study area showed that conductivity levels vary between 62.12 μS/cm −1 in station (I1) and 358.67 μS cm−1 in station (D2); the maximum value was registered in station D2 due to mining-type discharges product of grinding in the operations and amalgamation of the material that contribute large amounts of salts, total suspended solids, metals, and minerals. The maximum acceptable value for conductivity can be up to 1,000 μS cm−1, the values obtained in this study are below the value established (Ministry of Social Protection, Decree 1575 of 2007). Conductivity may be considered an estimation of the ionic force of a saline solution; the ionic composition of salt mixtures affects its toxicity (Mount et al., 1993). Thereby, a measurement like conductivity is necessary because the effects of the salts are the result of the magnitude of exposure and relative proportion of all the ions in the mix. The reference value of chronic aquatic life for conductivity derived from data in West Virginia is 300 μS cm−1 (EPA, 2011).

Some physical-chemical variables, like dissolved oxygen, BOD5, and COD behaved similarly in all the streams. Dissolved oxygen is one of the most important parameters in assessing water quality, its presence is essential to maintain aquatic life and its low availability limits the self-purifying capacity of the hydric sources (Saksena et al., 2008); the saturation percentage of dissolved oxygen was in all cases >100%, indicating that these waters are oversaturated due to rapid aeration of the large slopes of the streams that influence on the terrain's morphology, generating constant water falls that provoke turbulence and increase of this parameter. Likewise, its waters were characterized for being shallow, which facilitates contact with the atmosphere, temperature changes, and photosynthesis – factors that contribute to oversaturation (Fondriest, 2015).

The BOD5 is an indicator of the amount of oxygen required by bacteria during stabilization of organic matter susceptible to decomposition under aerobic conditions (Martínez et al., 2013). Sampling stations L2, D1, and D2 had the highest BOD5 values due to the location of some sources of moderate contamination in the study zone; however, the BOD5 values reported in all the sampling stations did not exceed 5 mg O2 L−1, which indicates that these are waters with low levels of contamination through biodegradable organic matter (Chapman, 1996).

The chemical oxygen demand (COD) determines the amount of oxygen required to oxidize organic matter in a water sample, low conditions specific of oxidizing agent, temperature, and time (IDEAM, 2007). The COD concentrations showed increasing trend and no evidence of a correlation with respect to BOD5, indicating that most of the organic material is not biodegradable, this is because many organic compounds oxidizable by dichromate are not biologically oxidizable (Barakat et al., 2016); likewise, certain inorganic compounds, like sulphurs, nitrites, ferrous iron, and thiosulfates are oxidized by dichromate, which could have introduced an inorganic COD in the result (Romero, 2004). It is indicated that the majority of COD is due to the matter present in the bodies of water and is not biodegradable, in certain cases, related with the region's geology with prevalence of rocks with diversity of metals from pyrite, arsenopyrite, and galena.

Alkalinity is defined as the capacity to neutralize acids; this parameter in most natural aquifers is caused by dissolved bicarbonate salts, formed by the CO action on base materials (Cheremisinoff, 2002). The Alkalinity values obtained in the streams varied between 5,19 mg CaCO3 L−1 and 17,00 mg CaCO3 L−1; the maximum value was reached in sampling station D2, given that this section is the recipient of mining discharges that contribute dissolved rock and runoff waters with contents of sulphurs, sulphates, carbonates, and salts (CRC, 2006b). The alkalinity values in the Piedra Imán, Lorenzo, and Dios Te Dé streams showed growing trend due to wear and dissolution of rocks that contribute cations (Mudd, 2007). According to (Kevern, 1989), the alkalinity in these waters is classified as low with values below 75,0 mg CaCO3 L−1. The values reported herein coincide with the observations made by Mamian and Zamora (2016), given that – in general – the total alkalinity present in the study area has good buffer capacity that avoids drastic variations in water pH.

The total hardness of the water in the streams corresponds to the sum of polyvalent cations expressed as the equivalent amount of calcium carbonate of which the most common are those of calcium and magnesium and is related with pH and alkalinity (Mosquera-Chaverra, 2016). The total hardness obtained in the streams ranged from 8,22 mg CaCO3 L−1 to 146,19 mg CaCO3 L−1. For station C1, the value was 23,05 mg CaCO3 L−1; the maximum value was obtained in sampling station D2 due to alkaline earth metals in water, fundamentally calcium and magnesium, from the dissolution of rocks and minerals from the material left over from the grinding process in the mines. In general, the concentrations registered in the other sampling stations indicate they were mostly product of the contact with geological formations (Neira, 2006). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), water from the streams and in this section of the Cauca River station C1, except for sampling station D2, is considered soft, given that they have concentrations below 60 mg CaCO3 L−1 (Martinez-Ortiz and Barrero-Arias, 2018); station D2 is reported as moderately hard water because it is within the range from 100 to 200 mg CaCO3 L−1.

Total coliforms are an indicator of possible changes in the water's biological location, indicating that the body of water has been contaminated with organic matter of fecal origin, both animal and human (Gualdrón-Durán, 2016). This parameter was monitored only in stations L2, I3, T4, D5, and C1. According with results obtained, the concentration of fecal coliforms was low compared with the total coliforms in all the streams. For station C1, the FC concentration was 2013, contribution due to household wastewaters from the municipality of Suárez. For the streams, it is inferred that the majority of coliforms is generated by vegetation and soil, but not by excrements from humans and warm-blooded animals (Tetzaguic, 2003).

According to Figures 5 and 7, it is established that mainly in the El Tamboral area, the parameters most affected are TSS and TUR, the high levels of TSS, TUR prevail; this is due to the fact that in these areas the rock crushing, milling and washing processes take place, which contain high contents of pyrite, chromite and galena, which increase the levels of these parameters, reducing the quality of the water, exceeding the permitted levels in surface water according to Colombian standards (<50 mg L−1) (MADS, 2015) (Vargas, 2012).

Mercury is an environmental contaminant of great concern globally; it is highly toxic to wildlife and humans, given that some of its organic forms, like methylmercury can biomagnify in trophic chains (Oliveira et al., 2018). The Hg concentration was monitored in stations L2, I3, T4, D5, and C1 due to the presence of gold beneficiation plants that incorporate Hg in their extraction process and discharge directly onto the hydric sources. The minimum value obtained was 0,094 μg L−1 in sampling station D5; the maximum value was 1,000 μg L−1 in sampling station T4. The Hg concentration in these streams was expected higher due to the presence of gold beneficiation plants that use the metal for gold recovery; nevertheless, it must be considered that it is an element that adheres easily to the soil's humus layer in the sediments (López, 2006). According to García-Gómez (2013), concentrations in the water medium tend to be lower than those found in sediments, or in species of fauna and flora present in the bodies of water. The Hg concentration in station C1 of the Cauca River was 0,003 μg L−1, a value above the Colombian standard of 0,002 μg L−1. If this is related with the volumes contributed by the Cauca River (Figure 5 (G)), the dilution factor is high compared with stream volumes. It can be observed that Hg is detected after the reservoir. Mercury concentrations are high in the outputs of the bodies of water of the operations, with values ranging between EM3 0,508 and ET3 10,265 μg L−1. These Hg concentrations are spilled onto the streams and then reach the reservoir.

Due to the high concentrations of mercury present in the stations analyzed in this study, the quality of the water is negatively affected, therefore it is necessary to make certain recommendations in order to reduce or completely eliminate the use of this metal during the performance of mining activities. According to the WHO, it is recommended to suspend practices such as mineral amalgamation, heating amalgam without a system that traps mercury vapors or a crucible, and cyanide treatment of mercury-contaminated slag. In order to reduce mercury emissions and exposure, alternatives such as the gravity method, direct smelting, and chemical filtration can be used without risk (UNEP, 2008; 2012).

Regarding the general quality of the water, the ICOMO indicators express regular and good values in the study area, however, according to Eq. (2), these values depend on three parameters, which are, the% of oxygen, the demand biochemistry of oxygen and total coliform content; Despite having a high content of total coliforms, the low oxygen saturation due to the slope of the study area causes the results of this indicator to be shown as good or fair.

A more precise measure to demonstrate the negative effect caused by artisanal mining in the study area, are the ICOSUS and ICOMINERA indicators, these indicators show the negative effect caused by the number of establishments near the study areas T4 and D2, where high TSS levels are the main factor in poor water quality.

5. Conclusions

Through quality and contamination indices, it was possible to identify that the principal contributor to contamination in the Lorenzo Stream comes from household wastewaters; additionally, Hg presence was identified, although in the stream's area of influence there is no gold mining. For the Dios Te Dé Stream, the principal affection is due to the contribution of wastewaters by gold mining activities that introduce high loads of solids, metals; besides, household wastewaters also impact upon the quality obtained.

The physical-chemical results show that sampling stations T1, T2, I1, and I2 were characterized for having good water quality, with oxygenated waters and pH close to neutral; while sampling stations T3, T4, and I3 were characterized as low quality waters due to the influence of anthropic activities that provide total suspended solids and turbidity, which affect significantly the waters that flow into La Salvajina Reservoir.

It was determined that the most-developed anthropic activities in the study zones (Piedra Imán Stream) were agriculture and gold mining, while in the Tamboral and Dios Te Dé streams the gold mining activity prevailed, exerting strong pressure on the quality of the hydric resource, especially in the middle and low parts of the streams.

The contamination contribution into the Cauca River due to Hg is generated by operations in the amalgamation process to obtain gold, as well as the TSS, TUR, and conductivity in the grinding processes (Table 4).

The sources of contamination found in the streams studied and through field observation, occur as a consequence of artisanal gold mining activities, mainly in the operations and rocky material extracted from the pitheads and spilled into the streams. This requires strategic interventions by the communities, miners, operation owners, and control organisms to minimize the negative impacts on the hydric resource and ecosystemic services associated with this resource, where it was possible to observe:

-

1.

Inadequate manipulation of cyanide (for its use and elimination or deactivation).

-

2.

The amalgamation process of all the mineral in the barrels and washing generates increased loss of Hg in the tailings which go to the hydric sources.

-

3.

Cyanide is used to extract residual gold from tails contaminated with Hg in some operations.

-

4.

Elimination of tailings with Hg, other heavy metals (Cr, Cd, As, Pb), and cyanide in the receptor environment (water, soil, and air).

-

5.

Decomposition of Hg amalgams takes place with no recovery method or filtering systems. In most cases, it is done with direct incineration.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

José Antonio Gallo Corredor: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Edier Humberto Pérez: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Ricardo Figueroa: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Apolinar Figueroa Casas: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Department of Chemistry, the Research Group on Analytic Chemistry (GIQA), Universidad del Cauca, the Formation Network of Human Talent for Social and Productive Innovation in the Department of Cauca (InnovAction Cauca) (BPIN 2012000100187), funded by the General Royalty System and executed by Universidad del Cauca (501100005682) (Colombia), Corporación Autónoma Regional del Cauca CRC, SENA, the Community Action Boards of La Turbina, El Tamboral, Miravalles, Maravélez veredas (sub-municipalities), the Board of Directors of the Township of Mindalá, the communities in these veredas, the Cooperative of vein gold miners from the municipality of Suárez Cauca, the owners of pitheads and operations for the support provided to this research.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- Abadía L., Ossa M. Universidad de Manizales; 2018. Análisis de las afectaciones sociales e hídricas a la comunidad del municipio de Ginebra, por la explotación de minería aurífera sobre la cuenca del Río Guabas, Valle del Cauca (Maestría) [Google Scholar]

- Adewumi A., Ayodeji T. Ecological and human health risks associated with metals in water from Anka artisanal gold mining area, Nigeria human and ecological risk assessment. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 2021;27:307–326. [Google Scholar]

- Alpers C.N., Yee J.L., Ackerman J.T., Orlando J.L., Slotton D.G., Marvin-DiPasquale M.C. Prediction of fish and sediment mercury in streams using landscape variables and historical mining. Sci. Total Environ. 2016;571:364–379. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.05.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambarita M., Lock K., Boets P., Everaert G., Thi H., Forio M., Musonge P., Semjonova N., Bennetsen E., Landuyt D., Dominguez-Granda L., Goethals P. Ecological water quality analysis of the Guayas river basin (Ecuador) based on macroinvertebrates indices. Limnologica. 2016;57:27–59. [Google Scholar]

- Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP)/United Nations (UN) Environment . Switzerland; Geneva: 2019. Technical Background Report for the Global Mercury Assessment 2018. Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme, Oslo, Norway/UN Environment Programme, Chemicals and Health Branch.https://web.unep.org/globalmercurypartnership/technical-background-report-global-mercury-assessment-2018 Retrieved from. Accesed (04 April 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Ardini F., Greta D., Grotti Marco. Arsenic speciation analysis of environmental samples. J. Anal. Atom. Spectrom. 2019;35:215–237. [Google Scholar]

- Balzino M., Seccatore J., Marin T., De Tomi G., Veiga M.M. Gold losses and mercury recovery in artisanal gold mining on the Madeira River, Brazil. J. Clean. Prod. 2015;102:370–377. [Google Scholar]

- Bansah K.J., Yalley A.B., Dumakor-Dupey N. The hazardous nature of small scale underground mining in Ghana. J. Sustain. Mining. 2016;15(1):8–25. [Google Scholar]

- Barakat A., El Baghdadi M., Rais J., Aghezzaf B., Slassi M. Assessment of spatial and seasonal water quality variation of Oum Er Rbia River (Morocco) using multivariate statistical techniques. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2016;4:284–292. [Google Scholar]

- Benouara N., Laraba A., Rachedi L.H. Assessment of groundwater quality in the Seraidi region (nort-east of Algeria) using NSF-WQI. Water Sci. Technol. Water Supply. 2016:1132–1137. [Google Scholar]

- Bharti K.D. Water quality indices used for surface water vulnerability assessment. Int. J. Environ. Sci. 2011;2:154–173. [Google Scholar]

- Black P., Richard M., Rossin R., Telmer K. Assessing occupational mercury exposures and behaviors of artisanal and small-scale gold miners in Burkina Faso using passive mercury vapour badges. Environ. Res. 2017;152:462–469. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2016.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R.M., McClelland N.I., Deininger R.A., Tozer R.G. A water quality index – do we dare? Water Sew. Works. 1970;117:339–343. [Google Scholar]

- Caho-Rodríguez C.A., López-Barrera E.A. Determinación del Índice de Calidad de Agua para el sector Occidental del humedal Torca-Guaymaral empleando las metodologías UWQI y CWQI. Produccion + Limpia. 2017;12:35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Castro M., Almeida J., Ferrer J., Diaz D. Indicadores de la calidad del agua: evolución y tendencias a nivel global. Ingeniería Solidaria. 2014;10:111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Chán-Santisteban M.L., Peña W. Evaluación de la calidad del agua superficial con potential para consumo humano en la cuenca alta del Sis Icán, Guatemala. Cuadernos de Investigación UNED. 2015;7:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman D. 1996. Water Quality Assessments - A Guide to Use of Biota, Sediments and Water in Environmental Monitoring- Second Edition. Great Britain: UNESCO/WHO/UNEP.https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/41850 Retrieved from. Accesed (21 February 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Chavarro A.G., Gélvez-Bernal E.J. Caracterización de la calidad de las aguas de la quebrada Fucha utilizando los índices de contaminación ICO con respecto a la precipitación y usos del suelo. Mutis. 2016;6:19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Cheremisinoff N.P. Pollution Engineering. Oxford Auckland Johannesburg Melbourne New Delhi. 2002. Handbook of water and wastewater treatment and technologies. Boston. [Google Scholar]

- Cordy P., Veiga M.M., Salih I., Al-Saadi S., Console S., Garcia O., Mesa L.A., Velásquez-López P.C., Roeser M. Mercury contamination from artisanal gold mining in Antioquia, Colombia: the world's highest per capita mercury pollution. Sci. Total Environ. 2011;410:154–160. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corporación Autónoma Regional del Cauca CRC Apoyo a proyectos de producción más limpia en minería para los distritos mineros del Cauca: Distrito Minero de Suárez. 2006. http://crc.gov.co/files/ConocimientoAmbiental/mineria/MINERIA%20SUAREZ/MINERALIZACION%20Suarez.pdf Retrieved from. Accesed (28 May 2017)

- Corporación Autónoma Regional del Cauca . 2006. Diagnóstico Ambiental en el Municipio de Suárez, Área de influencia corregimiento de Mindalá y La Toma. Suárez, Cauca. [Google Scholar]

- Defensoría del Pueblo La minería sin control. Un enfoque desde la vulneración de los Derechos Humanos. 2015:41. Bogotá, D. C. Colombia. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Arriaga F.A. Mercurio en la minería Del oro: Impacto en las Fuentes hídricas destinadas para consumo humano. Rev. Salud Pública. 2014;16:947–957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirección Nacional de Impuestos y Aduanas Nacionales DIAN . 2013. Circular Externa 000009 del 29 de noviembre de 2013: Información sobre mercancías peligrosas. Bogotá. [Google Scholar]

- Diringer S.E., Feingold B.J., Ortiz E.J., Gallis J.A., Araujo-Flores J.M., Axel Berky A., Pan W.K., Hsu-Kim H. River transport of mercury from artisanal and small-scale gold mining and risks for dietary mercury exposure in Madre de Dios, Peru. Environ. Sci. Processes Impacts. 2015:478–487. doi: 10.1039/c4em00567h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effendi H., Romanto, Wardiatno Y. Water quality status of Ciambulawung River, Banten Province, based on pollution index and NSF-WQI. Procedial Environ. Sci. 2015;24:228–237. [Google Scholar]

- Environmental Protection Agency . Office of Research and Development, National Center for Environmental Assessment; Washington, DC: 2011. A Field-Based Aquatic Life Benchmark for Conductivity in central Appalachian Streams. EPA/600/R-10/023. United States. [Google Scholar]

- Ewaid S.H., Abed S.A. Water quality index for Al-Gharraf River, southern Iraq. Egypt. J. Aquat. Res. 2017;43(2):117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Fondriest Environmental Inc Dissolved oxygen fundamentals of environmental measurements. 2015. http://www.fondriest.com/environmental-measurements/parameters/water-quality/dissolved-oxigen/ Retrieved from: Accesed (23 November 2020)

- Fowler B., Chou S., Jones R., Sullivan D., Chen C. 2015. Handbook on the Toxicology of Metals 4E. El Sevier Cap 28. [Google Scholar]

- García-Gómez A.G. Evaluación de la contaminación por vertimiento de mercurio en la zona minera, Pacarní - San Luis departamento del Huila. Revista de Tecnología. J. Technol. 2013;12:91–98. [Google Scholar]

- González-Márquez L.C., Torres-Bejarano F.M., Torregroza-Espinosa A.C., Hansen-Rodríguez I.R., Rodríguez-Gallegos H.B. Use of LANDSAT 8 images for depth and water quality assessment of El Guájaro Reservoir, Colombia. J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 2018;82:231–238. [Google Scholar]

- Grey A., Domínguez V., Castillero M. Determinación de Indicadores Fisicoquímicos y Microbiológicos de calidad del agua superficial en la Bahía de Manzanillo. RIDTEC. 2014;10:16–27. https://revistas.utp.ac.pa/index.php/id-tecnologico/article/view/10 Retrieved from. Accesed (18 September 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi C., Grimaldi M., Guedron S. Mercury distribution in tropical soil profiles related to origin of mercury and soil processes. Sci. Total Environ. 2008;401:121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gualdrón-Durán L.E. Evaluación de la calidad de agua de ríos de Colombia usando parámetros fisicoquímicos y biológicos. Revista Dinámica Ambiental. 2016;1:83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Mosquera H., Shruti V.C., Jonathan M.P., Priyadarsi D.R., Rivera-Rivera D.M. Metal concentrations in the beach sediments of Bahia Solano and Nuquí along the Pacific coast of Chocó, Colombia: a baseline study. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018;135:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyamfi O., Borgen P., Darko G., Ansah E., Vorkamp K., Leth J. Contamination, exposure and risk assessment of mercury in the soils of an artisanal gold mining community in Ghana. Chemosphere. 2021;267:128910. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.128910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvat M. Mercury as a global pollutant. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2002;374:981–982. [Google Scholar]

- IARC Some drinking-water disinfectants and contaminants, including arsenic. IARC Monogr. Eval. Carcinog. Risks Hum. 2004;84 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IGF Global trends in artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM): a review of key numbers and issues. Intergov. Forum Mining Minerals Metals Sustain. Dev. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- INGEOMINAS . 1995. Inst. Investigaciones en Geociéncias, Mineria y Química. Colombia: Min. Mines and Energy; p. 25. a Gold Mine. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto de Hidrología, Meteorología y Estudios Ambientales . 2005. Programa de fisicoquímica ambiental. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto de Hidrología, Meteorología y Estudios Ambientales . 2007. Demanda Química de Oxígeno por reflujo cerrado y volumetría. Colombia. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto de Hidrología, Meteorología y Estudios Ambientales . Sistema de Indicadores Ambientales de Colombia - Indicadores de Calidad del agua superficial; Bogotá: 2011. Hoja metodológica del indicador Índice de calidad del agua (versión 1,00) [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs H.L., Gabrielson I.N., Horton R.K., Lyon W.A., Hubbard E.C., McCallum E.G. Water quality criteria-stream vs effluent standards. Water Environ. Fed. 1965;37:292–315. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D.B. Chemical and microbiological characteristics of mineral spoils and drainage waters at abandoned coal and metal mines. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2003;3:47–66. [Google Scholar]

- Jønsson J.B., Appel P.W., Chibunda R.T. A matter of approach: the retort’s potential to reduce mercury consumption within small-scale gold mining settlements in Tanzania. J. Clean. Prod. 2009;17:77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Kevern R.N. 1989. Alkalinity Water, Classification Systems. Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Li G., Lei Y., Ge J., Wu S. The empirical relationship between mining industry development and environmental pollution in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2017;14:1–20. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14030254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López P.E. 2006. Apoyo a proyectos de producción más limpia en minería para los distritos mineros del Cauca. Popayán. [Google Scholar]

- Mamian L.L., Zamora G.H. Estudio ecológico del cangrejo de río, Hypolobocera sp (Crustacea, decapoda) en la quebrada Mano de Oso, Jardín Botánico de Popayán, municipio de Timbío, Cauca – Colombia. Rev Colombiana Cienc Anim. 2016;8:142–150. [Google Scholar]

- Marrugo-Negrete J., Benitez L.N., Olivero-Verbel J. Distribution of mercury in several environmental compartments in an aquatic ecosystem impacted by gold mining in Northern Colombia. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2008;55:305–316. doi: 10.1007/s00244-007-9129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez F., Galera I. vol. 1. Academic Research International; 2011. Monitoring and Evaluation of the Water Quality of Taal lake, Talisay, Batangas, Philippines; pp. 229–236. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Ortiz S.S., Barrero-Arias I.J. Universidad Santo Tomás; Villavicencio: 2018. Evaluación de las condiciones de calidad de agua, para la formulación de estrategias de aprovechamiento y conservación de la microcuenca quebrada La Argentina, Villavicencio-Meta.https://repository.usta.edu.co/bitstream/handle/11634/12064/2018santiagomartinez.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y Tesis. Retrieved from. Accesed (15 February 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Martínez G., Fermín I., Brito F., Márquez A., De la Cruz R., Rodríguez G., Pinto F. Calidad de las Agua del Caño Mánamo, Delta del Río Orinoco, Venezuela. Boletín del Instituto Oceanográfico de Venezuela. 2013;52:17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible (MADS) 2015. Resolución número 0631 de 2015. Por la cual se establecen los parámetros y los valores límites máximos permisibles en los vertimientos puntuales a cuerpos de aguas superficiales y a los sistemas de alcantarillado público y se dictan otras disposiciones.https://www.aguasdemanizales.com.co/Portals/Aguas2016/NuestraEmpresa/Documentos/LeyesDecretos/R631de2015MADS.pdf?ver=2015-12-23-170225-850 17 Marzo 2015. Retrieved from. Accesed (04 April 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Ambiente, Vivienda y Desarrollo Territorial (MAVDT) 2007. Resolución Número 2115. Por medio de la cual se señalan características, instrumentos básicos y frecuencias del sistema de control y vigilancia para la calidad del agua para consumo humano (22 jun 2007)https://www.minambiente.gov.co/images/GestionIntegraldelRecursoHidrico/pdf/Legislaci%C3%B3n_del_agua/Resoluci%C3%B3n_2115.pdf Retrieved from. Accesed (10 April 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Miyittah M., Tulashie S., Tsyawo F., Sarfo J., Darko A. Assessment of surface water quality status of the Aby Lagoon System in the Western Region of Ghana. Heliyon. 2020;6 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosquera-Chaverra L. Universidad de Manizales; 2016. Evaluación exploratoria de la calidad del agua del Río San Juan en el municipio de Tadó, Chocó, por el impacto que causan los vertimientos mineros. Magister.https://ridum.umanizales.edu.co/jspui/bitstream/20.500.12746/2953/1/Lina_Mosquera_2016.pdf.pdf Retrieved from. Accesed (13 March 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Mount D.R., Gulley D.D., Evans J.M. Proceedings, 1st Society of Petroleum Engineers/U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Environmental Conference. San Antonio, TX, USA. 1993. Salinity/toxicity relationships to predict the acute toxicity of produced waters to freshwater organisms; pp. 605–614. [Google Scholar]

- Mudd G. Gold mining in Australia: linking historical trends and environmental and resource sustainability. Environ. Sci. Pol. 2007;10:629–644. [Google Scholar]

- Neira M.A. Universidad de Chile; Santiago de Chile: 2006. Dureza en agua de consumo humano y uso industrial, impactos y medidas de mitigación. Estudio de caso: Chile.http://repositorio.uchile.cl/tesis/uchile/2006/neira_m/sources/neira_m.pdf Retrieved from. Accesed (28 January 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Noori R., Berndtsson R., Hosseinzadeh M., Adamowski J.F., Abyaneh M.R. A critical review on the application of the national sanitation foundation water quality index. Environ. Pollut. 2018;244:575–587. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.10.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira P., Lírio A.V., Canhoto C., Guilhermino L. Toxicity of mercury and postexposure recovery in Corbicula fluminea: neurotoxicity, oxidative stress and oxygen consumption. Ecol. Indicat. 2018;91:503–510. [Google Scholar]

- Olivero J., Johnson B., Arguello E. Human exposure to mercury in san Jorge river basin, Colombia (South America) Sci. Total Environ. 2002;289:41–47. doi: 10.1016/s0048-9697(01)01018-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PENUMA . 2002. Evaluación Mundial sobre el Mercurio Productos Químicos, Ginebra, Suiza. [Google Scholar]

- PENUMA . 2018. Going for Gold: Can Small-Scale Mines Be Mercury Free?https://www.unenvironment.org/news-and-stories/story/going-gold-can-small-scale-mines-be-mercury-free Retrieved from. Accesed (24 October 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Pérez E. vol. 9. Revista Tecnología en marcha; 2016. Control de calidad en aguas para consumo humano en la región Occidental de Costa Rica. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Valbuena G., Arrieta-Arrieta A., Contreras-Anaya J. first ed. 2015. Río Cauca: la geografía económica de su área de influencia; p. 35. Cartagena. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M., Vahter M., Sohel N., Yunus M., Wahed M.A., Streatfield P.K., Ekstrom E.C., Persson L.A. Arsenic exposure and age and sex specific risk for skin lesions: a population-based case-referent study in Bangladesh. Environ. Health Perspect. 2006;114:1847–1852. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M., Vahter M., Wahed M.A., Sohel N., Yunus M., Streatfield P.K., Erifeen S.E., Bhuiya A., Zaman K., Chowdhury A.M., Ekstrom E.C., Persson L.A. Prevalence of arsenic exposure and skin lesions. A population based survey in Matlab, Bangladesh. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2006;60:242–248. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.040212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajaee M., Obiri S., Green A., Long R., Cobbina S.J., Nartey V., Buck D., Antwi E., Basu N. Integrated assessment of artisanal and small-scale gold mining in Ghana—Part 2: natural sciences review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2015;12:8971–9011. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120808971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanaidou E., Wells M., Lau I., Laukamp C. Characterization of iron ore by visible and infrared reflectance and, Raman spectroscopies. Iron Ore Mineral. Process. Environ. Sustain. 2015;6:191–228. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez A., Restrepo R., Viña G. Cuatro índices de contaminación para caracterización de aguas continentales. Formulaciones Y Aplicación. Ciencia, Tecnología y Futuro. 1997;1:135–153. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez R.R., Cardeñosa M. Índices de contaminación para caracterización de aguas continentales y vertimientos. Formulaciones. Ciencia, Tecnología y Futuro. 1999;5:89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Reis A.T., Lopes C.B., Davidson C.M., Duarte A.C., Pereira E. Extraction of mercury water-soluble fraction from soils: an optimization study. Geoderma. 2014;213:255–260. [Google Scholar]

- Restrepo-Valencia I. Universidad de Manizales; 2015. Evaluación de la calidad del recurso hídrico del río Cabí a través de la formulación de un índice de contaminación asociado a la actividad minera aurífera (Maestría) [Google Scholar]

- Roldán G. 2003. Bioindicación de la calidad de agua en Colombia: uso del método BMWP/Col. Editorial Universidad de Antioquia. Colección ciencia y tecnología. Medellín, Colombia. [Google Scholar]

- Romero J.A. Escuela Colombiana de Ingeniería; Bogotá: 2004. Tratamiento de Aguas Residuales. Teoría y principios de diseño. [Google Scholar]

- Roulet M., Lucotte M. Geochemistry of mercury in pristine and flooded ferralitic soil of a tropical rain forest in French Guiana. South America. Water, Air, Soil Pollut. 1995;80:1079–1088. [Google Scholar]

- Saksena D.N., Garg R.K., Rao R.J. Water quality and pollution status of Chambal River in national Chambal sanctuary, Madhya Pradesh. J. Environ. Biol. 2008;29:701–710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samboni N.E., Carvajal Y., Escobar J.C. Revisión de parámetros fisicoquímicos como indicadores de calidad y contaminación del agua. Revista ingeniería e investigación. 2007;27:172–181. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez E., Colmenarejo M.F., Vicente J., Rubio A., García M.G., Travieso L., Borja R. Use of the water quality index and dissolved oxygen deficit as simple indicators of watersheds pollution. Ecol. Indicat. 2007;7:315–328. [Google Scholar]

- Scarpelli W., Horikava E.H. Chromium, iron, gold and manganese in Amapá and northern Pará, Brazil. Braz. J. Genet. 2018;48:415–433. [Google Scholar]

- Şener Ş., Şener E., Davraz A. Evaluation of water quality using water quality index (WQI) method and GIS in Aksu River (SW-Turkey) Sci. Total Environ. 2017;584–585:131–144. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.01.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra L.F. Maestría en desarrollo sostenible y medio ambiente; 2015. Contribución al diagnóstico de calidad del agua en la quebrada las brujas en el municipio de la Vega – Cundinamarca. Tesis. [Google Scholar]

- Silva M., da Silva J., Carvalho C., dos Santos C., Hadlicha D., de Santana C., de Jesus T. Geochemical evaluation of potentially toxic elements determined in surface sediment collected in an area under the influence of gold mining. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020;158:111384. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Filho E.V., Machado W., Oliveira R.R., Sella S.M., Lacerda L.D. Mercury deposition through litterfall in an Atlantic forest at Ilha Grande, southeast Brazil. Chemosphere. 2006;65:2477–2484. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soni H.B., Thomas S. Assessment of surface water quality in relation to water quality index of tropical lentic environment, Central Gujarat, India. Int. J. Environ. 2014;3:168–176. [Google Scholar]

- Sun W., Xia C., Xu M., Guo J., Sun G. Application of modified water quality indices as indicators to assess the spatial and temporal trends of water quality in the Dongjiang River. Ecol. Indicat. 2016;66:306–312. [Google Scholar]

- Swain E.B., Jakus P.M., Rice G., Lupi F., Maxson P.A., Pacyna J.M., Penn A., Spiegel S.J., Veiga M.M. Socioeconomic consequences of mercury use and pollution. Ambio. 2007;36:45–61. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447(2007)36[45:scomua]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telmer K.H., Veiga M.M. World emissions of mercury from small scale artisanal gold mining and the knowledge gaps about them. In: Pirrone N., Mason R., editors. Mercury Fate and Transport in the Global Atmosphere: Measurements Models and Policy Implications. UNEP United Nations Environmental Program. 2008. pp. 96–129. [Google Scholar]

- Tetzaguic C. 2003. Sistematización de la información de calidad del agua del lago de Amatitlán con parámetros que determinan su contaminación secuencial. Guatemala. [Google Scholar]

- Tomas D., Čurlin M., Marić A.S. Assessing the surface water status in Pannonian ecoregion by the water quality index model. Ecol. Indicat. 2017;79:182–190. [Google Scholar]

- Torres P., Cruz C.H., Patiño P., Escobar J.C., Andrea Pérez A. Aplicación de índices de calidad de agua -ICA orientados al uso de la fuente para consumo humano. Ing. Invest. 2010;30:86–95. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi M., Singal S.K. Use of principal components analysis for parameter selection for development of a novel water quality index: a case study of river Ganga India. Ecol. Indicat. 2019;96:430–436. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) 2008. Module 3: Mercury Use in Artisanal and Small Scale Gold Mining.http://www.unep.org/hazardoussubstances/Portals/9/Mercury/AwarenessPack/English/UNEP_Mod3_UK_Web.pdf Retrieved from. Accesed (01April 2021) [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) 2012. Reducing Mercury Use in Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining: A Practical Guide.http://www.unep.org/hazardoussubstances/Portals/9/Mercury/Documents/ASGM/Techdoc/UNEP%20Tech%20Doc%20APRIL%202012_120608b_web.pdf Se puede consultar en. Accesed (01April 2021) [Google Scholar]

- UPME . Ministerio de Minas; 2014. Estudio de la cadena del mercurio en Colombia con énfasis en la actividad minera de oro. [Google Scholar]

- Valverde-Solís A., Moreno-Tamayo E., Ortiz-Palacios N.Y. Análisis de la calidad de varios cuerpos de aguas superficiales en Bahía Solano utilizando índices de contaminación. Investigación. Biodiversidad y Desarrollo. 2015;34:14–21. [Google Scholar]