Abstract

The present study aimed to expand weight stigma theoretical models by accounting for central tenets of prominent eating disorder (ED) theories and increasing the generalizability of existing models for individuals across the weight spectrum. College students (Sample 1: N = 1,228; Sample 2: N = 1,368) completed online surveys assessing stigma and ED symptoms. In each sample, separately, multi-group path analyses tested whether body mass index (BMI) classification (underweight/average weight, overweight, obese) moderated a model wherein weight stigma experiences were sequentially associated with weight bias internalization, body dissatisfaction, and five ED symptoms: binge eating, purging, restricting, excessive exercise, muscle building behaviors. Results supported the assessed model overall and for individuals in each BMI class, separately. Although patterns of associations differed for individuals with different BMIs, these variations were limited. The present findings suggest that the adverse impact of weight stigma on distinct ED symptoms is not limited to individuals with elevated BMIs and that these associations are generally explained by the same mechanisms. Weight stigma interventions that focus on decreasing weight bias internalization and body dissatisfaction are recommended for individuals across the weight spectrum. Further examination of associations between weight stigma and multiple ED symptoms, beyond disinhibited eating, is supported.

Keywords: Eating Disorders, Weight Stigma, Weight Bias Internalization, Body Mass Index, Body Dissatisfaction

1. Introduction

Weight stigma, or the devaluation and denigration of individuals because of their body weights, has consistently been liked to adverse health outcomes across psychological (e.g., depressive symptoms), physiological (e.g., increased cortisol), and behavioral (e.g., disordered eating) domains of functioning (Alimoradi et al., 2019; Daly et al., 2019; Emmer et al., 2020; Puhl & Suh, 2015a,b; Pearl & Puhl, 2018; Vartanian & Porter, 2016). Associations between weight stigma and elevated eating disorder (ED) symptoms have particularly important theoretical and clinical implications, given the potential cyclical interconnectivity among weight stigma experiences, psychological and physiological markers of stress, ED symptoms, and weight changes that can collectively perpetuate poor mental and physical health (Tomiyama, 2014). Enhancing the understanding of how weight stigma maps onto various types of ED symptoms consequently serves as a valuable means of identifying treatment targets that can improve individuals’ holistic health.

1.1. Weight Stigma, Internalization, and Eating Disorder Symptoms

Most research that has examined associations between weight stigma and ED symptoms has focused on disinhibited eating outcomes among individuals with higher body weights. In general, research suggests that weight stigma experiences are associated with binge eating and other forms of disinhibited eating (e.g., emotional eating; Himmelstein et al., 2019; Puhl & Suh, 2015b; Vartanian & Porter, 2016; Wu & Berry, 2018). In addition, a small but growing body of evidence suggests that weight stigma experiences may also be associated with increased compensatory behaviors, dietary restriction, binge-purge symptoms, and decreased motivation to engage in health-promoting behaviors (Himmelstein et al., 2019; Pearl et al., 2015; Vartanian et al., 2018; Vartanian & Porter, 2016).

Individuals who experience weight stigma commonly internalize these experiences and subsequently endorse and apply negative weight-based attributes to themselves, a process known as weight bias internalization (Pearl & Puhl, 2014). Notably, compared to experienced weight stigma, weight bias internalization has been shown to uphold a particularly influential role in perpetuating ED and related forms of adverse mental health symptoms, likely due to its self-directed nature (Pearl & Puhl, 2018). For example, meta-analyses have found larger correlations between higher weight bias internalization and worse mental health than those found between experienced weight stigma and poor mental health (Alimoradi et al., 2019; Emmer et al., 2020). Likewise, evidence generally suggests that higher levels of weight bias internalization are positively associated with binge eating, global ED symptoms, depressive symptoms, body image concerns (Durso et al., 2012, 2016; Pearl & Puhl, 2014; Pearl & Puhl, 2018; Schvey & White, 2015) and, in some cases, dietary restraint and compensatory behaviors (Boswell & White, 2015; Himmelstein et al., 2019).

1.2. Explanatory Models

As a notable limitation of the evidence-base in this area, the mechanisms underlying associations between weight stigma and an array of ED behaviors remain understudied, and formal theoretical models seeking to explain these interrelations are in early stages of development. These recent theories have generally merged stigma and stress models from other non-weight and non-ED focused areas of study (e.g., sexual minority stress, neuroendocrinology) with the growing weight stigma evidence-base (Ratcliffe & Ellison, 2015; Sikorski et al., 2015; Tomiyama, 2014). For example, an adapted psychological mediation framework posits that weight stigma experiences serve as distal stressors that map onto proximal stressors such as weight bias internalization which, in turn, contribute to various affectively-based adverse mental health outcomes (Sikorski et al., 2015). Although formal weight stigma models of this nature are in their infancy, they stem from a larger body of evidence that suggests weight bias internalization mediates associations between weight stigma experiences and disinhibited ED symptoms among individuals with larger body weights (Sikorski et al., 2015) and, to a lesser degree, those across the weight spectrum (Himmelstein et al., 2019; O’Brien et al., 2016). For example, among college students with varied body mass indexes (BMIs), weight stigma experiences were previously associated with elevated weight bias internalization and, in turn, higher levels of three separate disinhibited eating outcomes: emotional, uncontrolled, and loss of controlled eating (O’Brien et al., 2016).

Existing theoretical models seeking to explain how weight stigma maps onto ED symptoms have not explicitly accounted for central tenets of prominent ED theories. In particular, despite the notion that body dissatisfaction is a well-established ED risk factor and has been consistently associated with both weight stigma experiences and, in particular, weight bias internalization (Durso et al., 2012, 2016; Pearl & Puhl, 2014; Pearl & Puhl, 2018; Puhl & Suh, 2015a), body dissatisfaction has only been peripherally accounted for in existing weight stigma models (e.g., Ratcliffe & Ellison, 2015; Sikorski et al., 2015; Tomiyama, 2014). Further, recent research has shown that the mediational role of weight bias internalization in associations between weight stigma experiences and ED behaviors is largely accounted for by components of body image and self-esteem, plausibly as a result of the self-directed nature of weight bias internalization and these two latter constructs (Meadows & Higgs, 2020). Yet, the directionality of associations between weight bias internalization and body dissatisfaction, in particular, as mediators of experienced weight stigma-ED behavior associations has not been assessed to date. Given that body dissatisfaction has been consistently supported as a robust proximal correlate of ED behaviors in prominent ED theories (Fairburn et al., 2003), and as experienced weight stigma has been supported as a proximal correlate of weight bias internalization in existing weight stigma theories (Sikorski et al., 2015; Tomiyama, 2014), it is plausible that a sequential mediational process (experienced weight stigma → weight bias internalization → body dissatisfaction → ED pathology) may help explain these interrelations and warrants assessment.

Existing theoretical models that have sought to explain associations among weight stigma and ED symptoms have also not accounted for evidence that ED pathology commonly exhibits transdiagnostic properties, such that individuals with clinical EDs and those with subclinical symptoms often engage in more than one ED behavior (Fairburn et al., 2003). The predominant focus on disinhibited eating outcomes (e.g., binge eating) in the existing weight stigma literature consequently provides a limited understanding of how weight stigma maps onto the full spectrum of ED behaviors that individuals may cope with. In addition, given the existing focus on associations between weight stigma and ED symptoms among individuals with higher body weights, less is known about how weight stigma impacts the ED behaviors of individuals across the weight spectrum. This limitation is noteworthy, as a growing literature suggests that the adverse consequences of both experienced weight stigma and weight bias internalization are not limited to individuals with higher BMIs (Schvey & White, 2015; Vartanian & Porter, 2016), and associations between weight stigma and ED symptoms have remained robust after controlling for BMI (Pearl & Puhl, 2018; Puhl & Suh, 2015a). This suggests that weight stigma-ED symptom associations exist independent of the influence of BMI and warrant further exploration.

1.3. Study Purpose

Despite a large body of evidence supporting associations among weight stigma experiences, weight bias internalization, and different types of ED symptoms, a theoretical model that collectively accounts for the intermediary role of weight bias internalization and body dissatisfaction in associations between weight stigma experiences and a variety of ED behaviors has not been assessed to date. Such evidence may be particularly important for augmenting the understanding of weight stigma-ED symptom associations for individuals across the full weight spectrum who may not invariably cope with weight stigma via disinhibited eating patterns. To address these research gaps, the present study aimed to: (1) test a path model wherein weight stigma experiences sequentially mapped onto weight bias internalization, body dissatisfaction, and five ED symptom outcomes (binge eating, purging, restricting, excessive exercise, muscle building behaviors); (2) determine whether these patterns of association differed for individuals based on BMI classification. In line with these aims, it was hypothesized that more weight stigma experiences would be successively associated with greater weight bias internalization, body dissatisfaction, and higher levels of all five ED symptom outcomes. Further, it was hypothesized that the assessed explanatory model would exhibit good model fit and yield meaningful effect sizes that would generally remain consistent across the BMI classes.

2. Method

2.1. Procedures

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from Old Dominion University and all procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. The present study included two independent samples of participants who participated in separate cross-sectional studies that used identical methodological procedures. Specifically, between March 2018 and April 2019 (Sample 1) and between January 2019 and July 2020 (Sample 2), college students aged 18 and older at a university in the Mid-Atlantic U.S. were recruited through a psychology department research pool. After electronically providing informed consent, interested participants in each study completed an online survey assessing stigma-related experiences and ED symptoms.

2.2. Participants

2.2.1. Sample 1

Participants in Sample 1 included 1,228 individuals who were, on average, 22.27 years old (SD = 5.83). Most respondents identified as female (n = 931, 75.8%) and heterosexual (n = 930, 75.7%). There was a relatively equal distribution of individuals who identified as White (n = 506, 41.2%) and Black or African American (n = 464, 37.8%), with the remaining respondents identifying as multiracial (n = 156, 12.7%), Asian, Asian American, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander (n = 62, 5.0%), an Other race (n = 33, 2.7%), and American Indian or Alaskan Native (n = 7, 0.6%). Also, 177 (14.4%) respondents identified as Hispanic/Latinx and 1,051 (85.6%) identified as non-Hispanic/Latinx. Based on self-reported height and weight, the mean BMI of the sample was 25.83 (SD = 6.15). There were 59 individuals classified within the underweight BMI range (<18.5 kg/m2; 4.8%), 593 in the average weight range (18.5–24.9 kg/m2; 48.3%), 337 in the overweight range (25–29.9 kg/m2; 27.4%), 236 in the obese range (≥30 kg/m2; 19.2%), and 3 respondents had insufficient data to calculate BMI (0.3%).

2.2.2. Sample 2

Participants in Sample 2 included 1,368 individuals who were, on average, 20.60 years old (SD = 3.47). Most respondents identified as female (n = 1,037, 75.80%) and heterosexual (n = 1,006, 73.54%). There was a relatively equal distribution of individuals who identified as White (n = 587, 42.91%) and Black or African American (n = 490, 35.82%), with the remaining respondents identifying as multiracial (n = 150, 10.96%), Asian, Asian American, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander (n = 80, 5.85%), an Other race (n = 55, 4.02%), and American Indian or Alaskan Native (n = 4, 0.29%). Also, 180 (13.16%) respondents identified as Hispanic/Latinx and 1,188 (86.84%) identified as non-Hispanic/Latinx. Based on self-reported height and weight, the mean BMI of the sample was 26.47 (SD = 6.57). There were 53 individuals classified within the underweight BMI range (<18.5 kg/m2; 3.87%), 637 in the average weight range (18.5–24.9 kg/m2; 46.56%), 370 in the overweight range (25–29.9 kg/m2; 27.05%), 304 in the obese range (≥30 kg/m2; 22.22%), and 4 respondents had insufficient data to calculate BMI (0.29%).

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Experienced Weight Stigma

2.3.1.1. The Everyday Discrimination Scale (EDDS).

Participants in Sample 1 completed the EDDS, a well-established measure that assesses how often individuals experience nine chronic and routine discriminatory experiences in their daily lives (Williams et al., 1997). This measure has exhibited good internal consistency and convergent validity with measures of perceived health, psychological distress, and well-being in racially diverse samples of adults (Williams et al., 1997). Response options range from 1 (never) to 6 (almost every day). When responding to the EDDS, participants are also asked to endorsed the main reason that they believe that have experienced the nine discriminatory experiences. In the present study, a dummy coded variable representing experienced weight stigma was created to identify participants who believed the main reason they have experienced discrimination is due to their body weights (1) vs. those who did not (0).

2.3.1.2. Stigmatizing Situations Inventory—Brief (SSI-B).

Participants in Sample 2 completed the SSI-B (Vartanian, 2015), a 10-item measure of the frequency with which individuals have experienced weight stigma throughout their lifetimes. The SSI-B has exhibited good internal consistency and convergent validity with measures of body dissatisfaction, disordered eating, and other measures of weight stigma experiences among college students and young adults from the community (Vartanian, 2015). Items are rated on a 10-point response scale ranging from 0 (never) to 9 (daily); higher mean scores reflect more frequent weight stigma experiences. In the present sample, internal consistency was good (α = .876).

2.3.2. The Modified Weight Bias Internalization Scale (WBIS-M)

Participants in Samples 1 and 2 completed the WBIS-M, an 11-item measure that assesses the extent to which individuals across the weight spectrum have internalized negative attitudes about body weight (Pearl & Puhl, 2014). This measure has exhibited good internal consistency and construct validity with measures of negative body image, ED symptoms, and affective concerns in a community-based sample of adults (Pearl & Puhl, 2014). Items are rated on a 7-point response scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), and higher scores reflect greater weight bias internalization. In the present sample, Cronbach’s α = .934.

2.3.3. The Eating Pathology Symptoms Inventory (EPSI)

Participants in Samples 1 and 2 completed the EPSI, a 45-item measure of the frequency with which individuals experience ED symptoms. In the present study, the following six of the EPSI’s eight subscales were used to provide a focused examination of body dissatisfaction and ED behaviors: Body Dissatisfaction, Binge Eating, Purging, Restricting, Excessive Exercise, and Muscle Building (Forbush et al., 2013). Example items include, “I ate a very large amount of food in a short period of time (e.g., within 2 hours)” (Binge Eating subscale) and “I made myself vomit in order to lose weight” (Purging subscale). This measure has exhibited excellent internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and convergent validity with other measures of ED symptoms, body image, and affect among college students and individuals with EDs and other mental health concerns (Forbush et al., 2013). Items are rated on a 5-point response scale (0 = never, 4 = very often), and higher summed composites reflect greater ED symptoms. In the present study, internal consistencies were good for the Body Dissatisfaction (α = .87), Binge Eating (α = .87), Excessive Exercise (α = .86), Restricting (α = .84), Purging (α = .84), and Muscle Building (α = .80) subscales.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

The present statistical analyses included two steps. First, a path model incorporating the direct and indirect effects specified in Figure 1 were run using data from all participants in Samples 1 and 2, separately, to examine whether weight bias internalization and, in turn, body dissatisfaction, mediated associations between experienced weight stigma and the five ED symptom outcomes. Second, two multiple group analyses (one per sample) that included a three level BMI classification grouping variable—underweight/average weight, overweight, obese BMIs—were run. Participants with underweight and average weight BMIs were combined into one category for each analysis due to small sample sizes for those who fell in the former (Sample 1: underweight n = 59; Sample 2: underweight n = 55). The multiple group analyses entailed comparing one model in which all direct effects were constrained to equality for individuals in each BMI class to a model in which all paths were freely estimated for the participants in the three classes. Significant differences between the models indicates that the model significantly differs between participants in the three BMI classes, and was determined via a chi-square difference test. To determine the nature of potential omnibus between-group model differences, a series of BMI group comparisons using the model test function in Mplus (Wald chi-square test of parameter constraints) were then run to determine whether the specific direct and indirect effects involved in the central mediational effects of interest (i.e., experienced weight stigma → weight bias internalization → body dissatisfaction → the five ED symptom outcomes) significantly differed between the three groups; paths that were shown to significantly differ across the BMI groups via these omnibus models were followed-up with post-hoc pairwise comparisons using Wald chi-square tests via the model test function to determine which of the three groups differed.

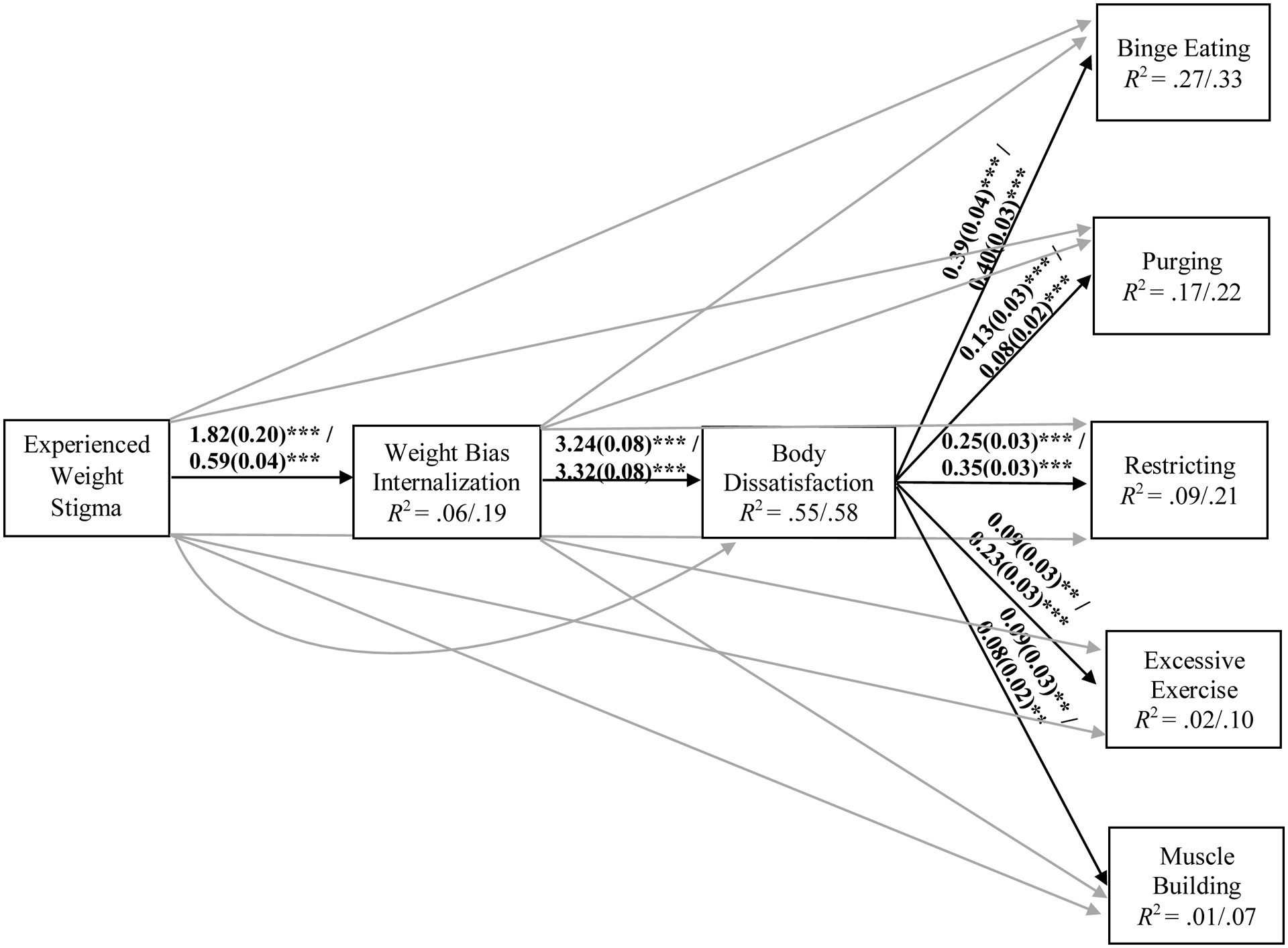

Figure 1.

Path models examining associations among weight stigma, weight bias internalization, body dissatisfaction, and eating disorder symptoms using data from Sample 1 and 2 participants, separately.

Note. Unstandardized effects are presented as Sample 1/Sample 2; correlated residuals among all eating disorder symptoms outcomes were modeled but are not depicted for simplicity; direct effects that were not directly involved in the central mediational paths of interest are presented in light gray.

***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05

Reasonable model fit was defined as comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) >.90, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) <.08, and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) <.08 (Kline, 2015). Further, the significance of the assessed indirect effects was determined via examination of 95% bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals for the parameter estimates using 5,000 draws and those that did not contain zero were considered significant. There were ≤0.3% missing data across all study variables of interest in Sample 1 and ≤0.95% in Sample 2. Missing data were addressed by using maximum likelihood estimation. Statistical significance was defined as α < .05.

3. Results

3.1. Structural Model

Tables 1 and 2 present descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations, respectively, for study variables of interest, and Table 3 and Figure 1 present the results of the structural models using data from Sample 1 and Sample 2 participants. The models for participants in Samples 1 and 2 exhibited good fit for the data; these models were both saturated, χ2[0] = 0, p < .001; RMSEA = 0 [90%CI = 0–0]; CFI = 1.0; TLI = 1.0; SRMR = 0, but all direct effects were retained to ensure that full mediation could be inferred (Darlington & Hayes, 2016). For both samples, there were significant associations between reporting weight stigma experiences and higher levels of weight bias internalization. Higher levels of weight bias internalization were also associated with elevated body dissatisfaction. In addition, elevated body dissatisfaction was directly associated with higher levels of all five ED symptom outcomes: binge eating, purging, restricting, excessive exercise, and muscle building behaviors. Similarly, as shown in Table 3, all five indirect effects linking weight stigma experiences to, in turn, elevated weight bias internalization, increased body dissatisfaction, and higher levels of each respective ED symptom outcome were significant.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics (M [SD] or n [%]) for Study Variables of Interest

| Sample 1 | Sample 2 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UW / Average Weight (n = 652) | Overweight (n = 337) | Obese (n = 236) | F(df = 2) | Differences | UW / Average Weight (n = 690) | Overweight (n = 370) | Obese (n = 304) | F(df = 2) | Differences | |

| Body Mass Index | 21.54 (2.07) | 27.19 (1.38) | 35.70 (5.55) | a1764.00*** | OB > OW, UW/AW; OW > UW/AW | 21.77 (2.13) | 27.04 (1.40) | 36.43 (5.61) | a642.48*** | OB > OW, UW/AW; OW > UW/AW |

| Experienced Weight Stigmac | 8 (1.23%) | 8 (2.37%) | 33 (13.98%) | b76.63*** | OB > OW, UW/AW | 0.61 (0.95) | 0.85 (1.14) | 1.36 (1.42) | a36.55*** | OB > OW, UW/AW; OW > UW/AW |

| Weight Bias Internalization | 2.59 (1.27) | 3.39 (1.48) | 4.07 (1.57) | a99.48*** | OB > OW, UW/AW; OW > UW/AW | 2.79 (1.39) | 3.48 (1.43) | 4.33 (1.55) | 124.29*** | OB > OW, UW/AW; OW > UW/AW |

| Body Dissatisfaction | 8.82 (6.13) | 11.66 (6.53) | 13.73 (6.31) | 60.13*** | OB > OW, UW/AW; OW > UW/AW | 8.73 (6.79) | 11.04 (6.77) | 14.22 (6.71) | 69.75*** | OB > OW, UW/AW; OW > UW/AW |

| Binge Eating | 7.86 (5.71) | 9.33 (6.19) | 10.26 (6.92) | a14.55*** | OB, OW > UW/AW | 7.37 (5.85) | 9.03 (6.57) | 10.33 (7.00) | a23.61*** | OB > OW, UW/AW; OW > UW/AW |

| Purging | 1.39 (3.07) | 2.24 (3.37) | 3.43 (4.49) | a23.93*** | OB > OW, UW/AW; OW > UW/AW | 1.35 (2.98) | 2.45 (4.07) | 3.11 (4.71) | a24.17*** | OB, OW > UW/AW |

| Restricting | 7.73 (5.47) | 6.81 (4.74) | 6.49 (4.42) | a7.14** | UW/AW > OB, OW | 7.07 (5.74) | 6.21 (5.44) | 6.92 (5.30) | a2.96 | - |

| Excessive Exercise | 5.58 (4.96) | 6.56 (5.02) | 5.69 (4.40) | a4.51* | OW > UW/AW | 5.06 (5.22) | 6.16 (5.26) | 5.63 (5.11) | 5.45** | OW > UW/AW |

| Muscle Building | 3.48 (3.92) | 3.63 (4.19) | 3.07 (3.97) | 1.43 | - | 3.19 (3.76) | 3.60 (4.32) | 2.72 (3.65) | a4.16* | OW > OB |

Note. OB = obese BMI; OW = overweight BMI; UW/AW = underweight or average weight BMI.

Welch’s ANOVAs with Games-Howell post-hoc tests were run owing to violations of the equality of variances assumption.

Chi square tests were run owing to the categorical nature of both variables.

Experienced weight stigma was a dichotomous variable in Sample 1 and a continuous variable in Sample 2.

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations for Participants in Samples 1 and 2

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Body Mass Index | - | .250*** | .372*** | .287*** | .165*** | .258*** | −.099** | .041 | −.034 |

| 2. Experienced Weight Stigma | .288*** | - | .236*** | .176*** | .112*** | .170*** | .005 | −.005 | .043 |

| 3. Weight Bias Internalization | .385*** | .440*** | - | .740*** | .439*** | .377*** | .206*** | .095** | .055 |

| 4. Body Dissatisfaction | .303*** | .382*** | .756*** | - | .515*** | .387*** | .299*** | .124*** | .104*** |

| 5. Binge Eating | .198*** | .365*** | .465*** | .550*** | - | .421*** | .190*** | .233*** | .293*** |

| 6. Purging | .180*** | .403*** | .373*** | .363*** | .394*** | - | .249*** | .278*** | .368*** |

| 7. Restricting | −.025 | .296*** | .296*** | .424*** | .246*** | .381*** | - | .180*** | .179*** |

| 8. Excessive Exercise | .068** | .172*** | .214*** | .300*** | .344*** | .367*** | .210*** | - | .576*** |

| 9. Muscle Building | −.047* | .242*** | .139*** | .176*** | .323*** | .452*** | .228*** | .543*** | - |

Note. Bivariate correlations for Sample 1 are reported above the diagonal and those for Sample 2 are reported below the diagonal.

Table 3.

Parameter Estimates for the Structural Model Using Data from All Participants in Sample 1 and Sample 2

| Sample 1 | Sample 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effects | b(SE) | P | β | b(SE) | P | β | ||

| Body Dissatisfaction → Binge Eating | 0.39 (0.04) | <.001 | .42 | 0.40 (0.03) | <.001 | .44 | ||

| WBI → Binge Eating | 0.52 (0.17) | .002 | .13 | 0.23 (0.16) | .158 | .06 | ||

| Weight Stigma → Binge Eating | 0.24 (1.00) | .811 | .01 | 0.95 (0.15) | <.001 | .17 | ||

| Body Dissatisfaction → Purging | 0.13 (0.03) | <.001 | .24 | 0.08 (0.02) | <.001 | .16 | ||

| WBI → Purging | 0.43 (0.12) | <.001 | .18 | 0.32 (0.10) | .002 | .13 | ||

| Weight Stigma → Purging | 1.53 (0.79) | .052 | .09 | 0.94 (0.15) | <.001 | .29 | ||

| Body Dissatisfaction → Restricting | 0.25 (0.03) | <.001 | .32 | 0.35 (0.03) | <.001 | .45 | ||

| WBI → Restricting | −0.07 (0.14) | .611 | −.02 | −0.44 (0.14) | .002 | −.12 | ||

| Weight Stigma → Restricting | −1.24 (0.80) | .120 | −.05 | 0.86 (0.13) | <.001 | .18 | ||

| Body Dissatisfaction → Excessive Exercise | 0.09 (0.03) | .007 | .12 | 0.23 (0.03) | <.001 | .31 | ||

| WBI → Excessive Exercise | 0.04 (0.14) | .760 | .01 | −0.19 (0.14) | .174 | −.06 | ||

| Weight Stigma → Excessive Exercise | −0.74 (0.64) | .243 | −.03 | 0.35 (0.14) | .010 | .08 | ||

| Body Dissatisfaction → Muscle Building | 0.09 (0.03) | .001 | .14 | 0.08 (0.02) | .001 | .14 | ||

| WBI → Muscle Building | −0.15 (0.12) | .200 | −.06 | −0.16 (0.11) | .147 | −.06 | ||

| Weight Stigma → Muscle Building | 0.67 (0.69) | .332 | .03 | 0.73 (0.12) | <.001 | .22 | ||

| WBI → Body Dissatisfaction | 3.24 (0.08) | <.001 | .74 | 3.32 (0.08) | <.001 | .73 | ||

| Weight Stigma → Body Dissatisfaction | −0.16 (0.83) | .852 | −.01 | 0.38 (0.13) | .005 | .06 | ||

| Weight Stigma → WBI | 1.82 (0.20) | <.001 | .24 | 0.59 (0.04) | <.001 | .44 | ||

| Indirect Effects | b(SE) | p | 95% CI | b(SE) | p | 95% CI | ||

| LL | UL | |||||||

| Weight Stigma → WBI → Body Dissatisfaction → | ||||||||

| Binge Eating | 2.32 (0.33) | <.001 | 1.71 | 3.02 | 0.79 (0.08) | <.001 | 0.65 | 0.97 |

| Purging | 0.76 (0.17) | <.001 | 0.46 | 1.12 | 0.16 (0.04) | <.001 | 0.09 | 0.26 |

| Restricting | 1.48 (0.25) | <.001 | 1.04 | 2.02 | 0.69 (0.07) | <.001 | 0.57 | 0.85 |

| Excessive Exercise | 0.52 (0.20) | .010 | 0.16 | 0.97 | 0.46 (0.06) | <.001 | 0.34 | 0.59 |

| Muscle Building | 0.50 (0.17) | .003 | 0.19 | 0.85 | 0.15 (0.05) | .001 | 0.07 | 0.24 |

| Weight Stigma → WBI → | ||||||||

| Binge Eating | 0.94 (0.33) | .004 | 0.34 | 1.65 | 0.14 (0.10) | .161 | −0.06 | 0.320 |

| Purging | 0.77 (0.24) | .001 | 0.34 | 1.30 | 0.19 (0.06) | .003 | 0.06 | 0.31 |

| Restricting | −0.13 (0.25) | .614 | −0.64 | 0.36 | −0.26 (0.09) | .003 | −0.44 | -0.10 |

| Excessive Exercise | 0.08 (0.26) | .762 | −0.42 | 0.60 | −0.11 (0.08) | .180 | −0.28 | 0.05 |

| Muscle Building | −0.27 (0.22) | .205 | −0.70 | 0.14 | −0.09 (0.07) | .152 | −0.22 | 0.03 |

| Weight Stigma → WBI → Body Dissatisfaction | 5.89 (0.68) | <.001 | 4.54 | 7.21 | 1.98 (0.12) | <.001 | 1.74 | 2.23 |

Note. Sample 1 N = 1,229; Sample 2 N = 1,368; WBI = weight bias internalization; Weight stigma = experienced weight stigma; BMI = body mass index; CI = bias-corrected bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

3.2. Differences Based on Weight Classification

3.2.1. Sample 1

Table 4 presents parameter estimates for the assessed model for Sample 1 participants in each BMI classification, separately, as well as the results of difference tests for specific direct and indirect effects directly involved in the central mediational paths of interest; Figure 2 provides a graphical representation of these results. First, the results of a chi-square difference test indicated that there was a significant difference between a model wherein all direct effects were fully constrained to equality and a model in which all direct effects were freely estimated across the three BMI classes, χ2diff [36] = 104.593, p < .001). That is, BMI class moderated the full model.

Table 4.

Parameter Estimates for Sample 1 Participants Within Each Body Mass Index Classification and Between-Group Differences

| Underweight/Average Weight (n = 652) | Overweight (n = 337) | Obese (n = 236) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI Class Differences | ||||||||||||

| Direct Effects | b(SE) | p | β | b(SE) | p | β | b(SE) | β | Wald χ2 (df = 2) | Wald χ2 (df = 1) | ||

| Body Dissatisfaction → Binge Eating | 0.39 (0.05) | <.001 | .42 | 0.40 (0.07) | <.001 | .42 | 0.41 (0.10) | <.001 | .37 | 0.03 | ||

| WBI → Binge Eating | 0.55 (0.25) | .028 | .12 | 0.34 (0.30) | .252 | .08 | 0.80 (0.41) | .052 | .18 | - | ||

| Weight Stigma → Binge Eating | 2.16 (2.67) | .417 | .04 | −2.75 (2.15) | .201 | −.07 | 0.49 (1.30) | .706 | .03 | - | ||

| Body Dissatisfaction → Purging | 0.14 (0.03) | <.001 | .28 | 0.07 (0.05) | .121 | .14 | 0.17 (0.07) | .011 | .24 | 2.89 | ||

| WBI → Purging | 0.36 (0.17) | .037 | .15 | 0.37 (0.25) | .130 | .16 | 0.44 (0.29) | .127 | .15 | - | ||

| Weight Stigma → Purging | −0.40 (1.53) | .796 | −.01 | 2.84 (1.91) | .137 | .13 | 1.13 (1.03) | .271 | .09 | - | ||

| Body Dissatisfaction → Restricting | 0.33 (0.05) | <.001 | .37 | 0.19 (0.06) | .001 | .26 | 0.11 (0.06) | .077 | .16 | 9.04* |

a4.04* b7.75** c0.74 |

UW/AW > OW, OB |

| WBI → Restricting | 0.627 (0.22) | .005 | .15 | −0.09 (0.26) | .741 | −.03 | −0.09 (0.26) | .718 | −.03 | - | ||

| Weight Stigma → Restricting | 0.29 (2.89) | .920 | .01 | −0.39 (2.12) | .854 | −.01 | 0.16 (0.87) | .856 | .01 | - | ||

| Body Dissatisfaction → Excessive Exercise | 0.08 (0.05) | .117 | .09 | 0.11 (0.06) | .058 | .15 | 0.05 (0.07) | .466 | .07 | 0.49 | ||

| WBI → Excessive Exercise | 0.36 (0.22) | .109 | .09 | −0.14 (0.27) | .598 | −.04 | −0.23 (0.27) | .394 | −.08 | - | ||

| Weight Stigma → Excessive Exercise | −1.76 (1.64) | .282 | −.04 | −1.66 (1.69) | .324 | −.05 | 0.59 (0.85) | .483 | .05 | - | ||

| Body Dissatisfaction → Muscle Building | 0.10 (0.04) | .005 | .16 | 0.06 (0.05) | .235 | .09 | 0.08 (0.06) | .238 | .12 | 0.60 | ||

| WBI → Muscle Building | 0.11 (0.18) | .553 | .04 | −0.37 (0.23) | .104 | −.13 | −0.08 (0.24) | .753 | −.03 | - | ||

| Weight Stigma → Muscle Building | 3.37 (1.73) | .051 | .10 | −0.29 (1.47) | .845 | −.01 | 0.85 (0.87) | .332 | .07 | - | ||

| WBI → Body Dissatisfaction | 3.41 (0.13) | <.001 | .71 | 3.21 (0.16) | <.001 | .73 | 2.84 (0.21) | <.001 | .71 | 5.98 | ||

| Weight Stigma → Body Dissatisfaction | −2.39 (2.00) | .232 | −.04 | 0.93 (2.13) | .661 | .02 | 0.45 (1.04) | .669 | .02 | - | ||

| Weight Stigma → WBI | 0.94 (0.57) | .096 | .08 | 1.57 (0.31) | <.001 | .16 | 1.25 (0.25) | <.001 | .28 | 0.84 | ||

| Underweight/Average Weight (n = 652) | Overweight (n = 337) | Obese (n = 236) | ||||||||||

| Indirect Effects | b(SE) | 95% CI | b(SE) | 95% CI | b(SE) | 95% CI | BMI Class Differences | |||||

| LL | UL | LL | UL | LL | UL | Wald χ2 (<df = 2) | ||||||

| Weight Stigma → WBI → Body Dissatisfaction → | ||||||||||||

| Binge Eating | 1.26 (0.78) | −0.11 | 2.97 | 2.01 (0.55) | 1.13 | 3.35 | 1.44 (0.45) | 0.72 | 2.54 | 0.63 | ||

| Purging | 0.46 (0.30) | −0.01 | 1.19 | 0.36 (0.25) | −0.07 | 0.95 | 0.61 (0.27) | 0.18 | 1.24 | 0.50 | ||

| Restricting | 1.06 (0.64) | −0.10 | 2.41 | 0.93 (0.37) | 0.32 | 1.81 | 0.40 (0.25) | 0.01 | 1.01 | 2.07 | ||

| Excessive Exercise | 0.24 (0.23) | −0.02 | 0.96 | 0.56 (0.34) | −0.01 | 1.34 | 0.18 (0.25) | −0.29 | 0.72 | 0.84 | ||

| Muscle Building | 0.34 (0.24) | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.29 (0.27) | −0.17 | 0.92 | 0.27 (0.23) | −0.16 | 0.77 | 0.06 | ||

| Weight Stigma → WBI → | ||||||||||||

| Binge Eating | 0.52 (0.41) | 0.00 | 1.70 | 0.54 (0.49) | −0.37 | 1.62 | 1.00 (0.57) | 0.06 | 2.35 | - | ||

| Purging | 0.34 (0.27) | −0.002 | 1.16 | 0.58 (0.41) | −0.08 | 1.57 | 0.54 (0.38) | −0.09 | 1.47 | - | ||

| Restricting | 0.59 (0.44) | 0.01 | 1.84 | −0.14 (0.42) | −0.99 | 0.71 | −0.12 (0.33) | −0.83 | 0.49 | - | ||

| Excessive Exercise | 0.34 (0.32) | −0.04 | 1.39 | −0.22 (0.44) | −1.15 | 0.58 | −0.30 (0.34) | −1.00 | 0.38 | - | ||

| Muscle Building | 0.10 (0.21) | −0.17 | 0.75 | −0.58 (0.39) | −1.46 | 0.08 | −0.10 (0.31) | −0.75 | 0.51 | - | ||

| Weight Stigma → WBI → Body Dissatisfaction | 3.22 (1.94) | −0.38 | 7.13 | 5.05 (1.05) | 3.11 | 7.21 | 3.54 (0.77) | 2.06 | 5.07 | - | ||

Note. WBI = weight bias internalization; Weight stigma = experienced weight stigma; BMI = body mass index; UW/AW = underweight/average weight; OW = overweight; OB = obese; CI = 95% bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit; - = effect not directly involved in the central mediational paths of interest, difference tests not run to avoid increasing Type I error; all Wald χ2 difference tests for assessed indirect effects were nonsignificant.

UW/AW vs. OW.

UW/AW vs. OB.

OW vs. OB.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

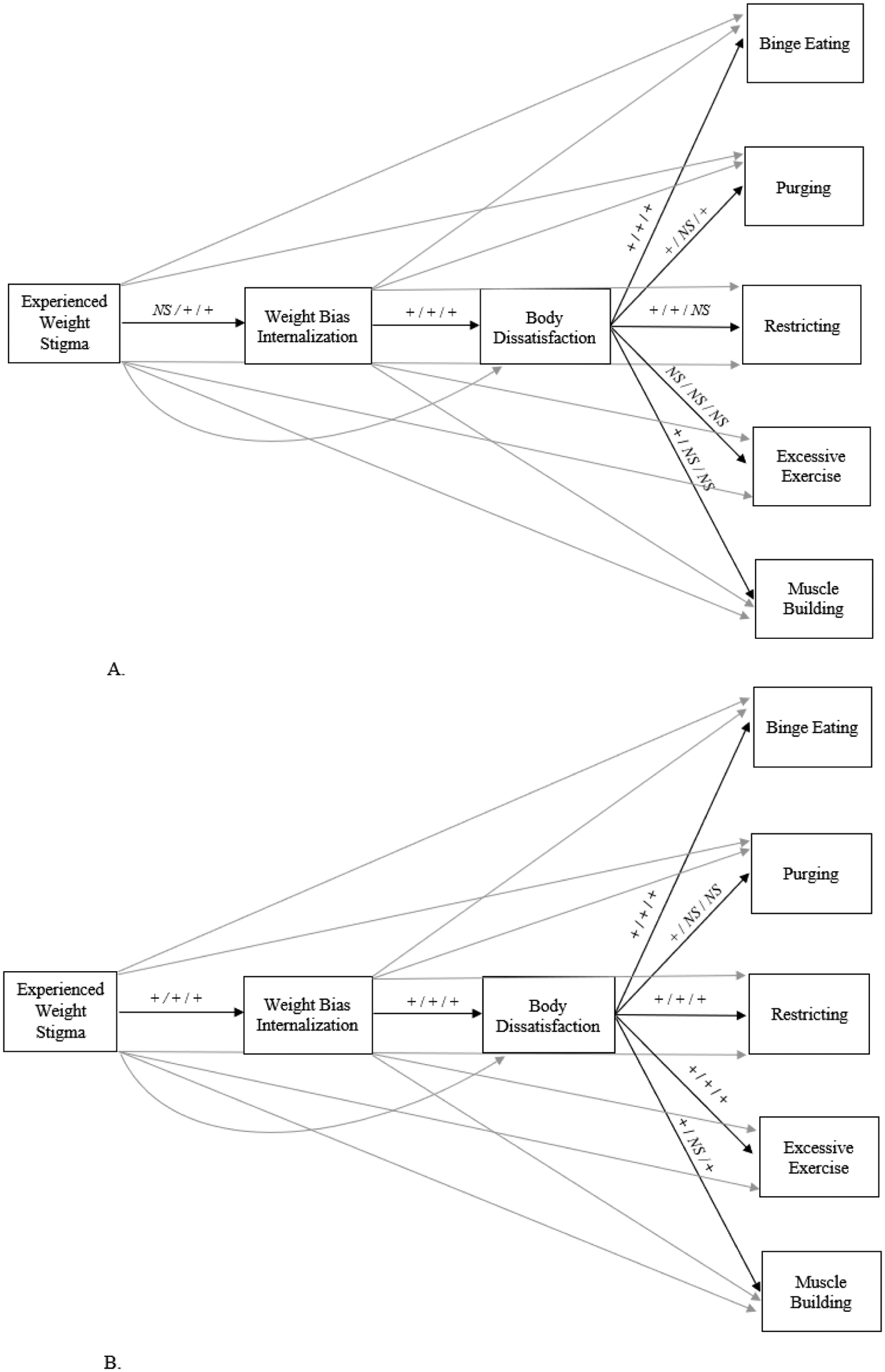

Figure 2.

Multiple group path models examining associations among weight stigma, weight bias internalization, body dissatisfaction, and eating disorder symptoms using data from Sample 1 (panel A) and Sample 2 (panel B) participants.

Note. The pattern of effects is presented as underweight or average weight BMI group / overweight BMI group / obese BMI group; + = positive effect, − = negative effect, NS = non-significant effect; correlated residuals among all eating disorder symptoms outcomes were modeled but are not depicted for simplicity; direct effects that were not directly involved in the central mediational paths of interest are presented in light gray.

The Wald chi-square test of parameter constraints was then used to identify specific direct and indirect effects that significantly differed between the three groups. Regarding the direct effects, as shown in Table 4, there was a significant difference between individuals in the three BMI classes for the path connecting body dissatisfaction to restricting ED behaviors (p = .011). Post-hoc analyses for the significant direct effect indicated that a positive association between body dissatisfaction and restricting was stronger for individuals in the underweight/average weight class (β = 0.37) compared to those in both the overweight (β = 0.26; Wald χ2[1] = 4.04, p = .044) and obese weight classes (β = 0.16; Wald χ2[1] = 7.75, p = .005); this path did not differ between participants in the overweight and obese classes, Wald χ2[1] = 0.74, p = .390). There were no significant differences between individuals in the three BMI classes for the remaining direct effects for any of the indirect effects connecting experienced weight stigma, weight bias internalization, and body dissatisfaction to binge eating, purging, restricting, excessive exercise, or muscle building. Given this, indirect effect post-hoc difference tests were not run.

3.2.2. Sample 2

Table 5 presents parameter estimates for the assessed model for Sample 2 participants who comprised each BMI classification, separately, as well as the results of difference tests for specific direct and indirect effects directly involved in the central mediational paths of interest; Figure 2 provides a graphical representation of these results. First, the results of a chi-square difference test indicated that there was a significant difference between a model wherein all direct effects were fully constrained to equality and a model in which all direct effects were freely estimated across the three BMI classes, χ2diff [36] = 65.254, p = .002. That is, BMI class moderated the full model. However, the Wald chi-square test of parameter constraints did not identify differences between the three groups for any of the specific direct and indirect effects that were involved in the central mediational paths of interest. Given this, the omnibus model difference likely stems from between-group differences for direct effects that were involved in other, non-focal paths; post-hoc tests were not run for these auxiliary paths to avoid increasing Type I error.

Table 5.

Parameter Estimates for Sample 2 Participants Within Each Body Mass Index Classification and Between-Group Differences

| Underweight/Average Weight (n = 690) | Overweight (n = 370) | obese (n = 304) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI Class Differences | |||||||||||

| Direct Effects | b(SE) | p | β | b(SE) | p | β | b(SE) | p | β | Wald χ2 (df = 2) | Wald χ2 (df = 1) |

| Body Dissatisfaction → Binge Eating | 0.44 (0.04) | <.001 | .51 | 0.35 (0.07) | <. 001 | .36 | 0.37 (0.09) | <.001 | .35 | 2.17 | |

| WBI → Binge Eating | −0.12 (0.20) | .566 | −.03 | 0.58 (0.32) | .071 | .13 | 0.58 (0.40) | .143 | .13 | - | |

| Weight Stigma → Binge Eating | 0.96 (0.20) | <.001 | .16 | 1.42 (0.24) | <.001 | .25 | 0.60 (0.29) | .039 | .12 | - | |

| Body Dissatisfaction → Purging | 0.08 (0.02) | .001 | .18 | 0.07 (0.04) | .093 | .12 | 0.13 (0.07) | .054 | .18 | 0.69 | |

| WBI → Purging | 0.28 (0.11) | .008 | .13 | 0.38 (0.19) | .050 | .13 | 0.12 (0.31) | .713 | .04 | - | |

| Weight Stigma → Purging | 1.06 (0.20) | <.001 | .34 | 1.34 (0.27) | <.001 | .38 | 0.50 (0.30) | .097 | .15 | - | |

| Body Dissatisfaction → Restricting | 0.39 (0.04) | <.001 | .46 | 0.32 (0.06) | <.001 | .40 | 0.32 (0.06) | <.001 | .41 | 1.31 | |

| WBI → Restricting | −0.14 (0.21) | .498 | −.03 | −0.15 (0.28) | .591 | −.04 | −0.42 (0.28) | .129 | −.12 | - | |

| Weight Stigma → Restricting | 0.98 (0.20) | <.001 | .16 | 1.05 (0.23) | <.001 | .22 | 0.85 (0.24) | <.001 | .23 | - | |

| Body Dissatisfaction → Excessive Exercise | 0.25 (0.04) | <.001 | .32 | 0.18 (0.06) | .002 | .23 | 0.26 (0.06) | <.001 | .34 | 1.33 | |

| WBI → Excessive Exercise | 0.08 (0.20) | .674 | .02 | −0.41 (0.27) | .123 | −.11 | −0.35 (0.29) | .237 | −.11 | - | |

| Weight Stigma → Excessive Exercise | 0.19 (0.20) | .360 | .03 | 1.01 (0.22) | <.001 | .22 | 0.11 (0.24) | .654 | .03 | - | |

| Body Dissatisfaction → Muscle Building | 0.10 (0.03) | .001 | .18 | 0.02 (0.05) | .667 | .03 | 0.11 (0.05) | .032 | .21 | 2.58 | |

| WBI → Muscle Building | −0.02 (0.15) | .884 | −.01 | −0.21 (0.21) | .330 | −.07 | −0.07 (0.26) | .785 | −.03 | - | |

| Weight Stigma → Muscle Building | 0.98 (0.19) | <.001 | .25 | 1.26 (0.20) | <.001 | .33 | 0.21 (0.19) | .260 | .08 | - | |

| WBI → Body Dissatisfaction | 3.41 (0.13) | <.001 | .70 | 3.30 (0.17) | <.001 | .70 | 3.18 (0.16) | <.001 | .73 | 1.07 | |

| Weight Stigma → Body Dissatisfaction | 0.23 (0.27) | .396 | .03 | 0.48 (0.21) | .025 | .08 | 0.46 (0.20) | .021 | .10 | - | |

| Weight Stigma → WBI | 0.57 (0.05) | <.001 | .39 | 0.48 (0.06) | <.001 | .38 | 0.42 (0.06) | <.001 | .39 | 3.92 | |

| Underweight/Average Weight (n = 690) | Overweight (n = 370) | Obese (n = 304) | |||||||||

| Indirect Effects | b(SE) | 95% CI | b(SE) | 95% CI | b(SE) | 95% CI | BMI Class Differences | ||||

| LL | UL | LL | UL | LL | UL | Wald χ2 (df = 2) | |||||

| Weight Stigma → WBI → Body Dissatisfaction → | |||||||||||

| Binge Eating | 0.86 (0.12) | 0.66 | 1.11 | 0.54 (0.13) | 0.32 | 0.82 | 0.49 (0.14) | 0.25 | 0.80 | 5.69 | |

| Purging | 0.15 (0.05) | 0.07 | 0.25 | 0.11 (0.07) | −0.01 | 0.26 | 0.17 (0.09) | 0.01 | 0.38 | 0.39 | |

| Restricting | 0.75 (0.10) | 0.58 | 0.99 | 0.51 (0.12) | 0.31 | 0.76 | 0.43 (0.11) | 0.25 | 0.68 | 4.92 | |

| Excessive Exercise | 0.48 (0.09) | 0.33 | 0.67 | 0.28 (0.10) | 0.10 | 0.50 | 0.35 (0.10) | 0.17 | 0.57 | 2.48 | |

| Muscle Building | 0.19 (0.06) | 0.08 | 0.31 | 0.03 (0.07) | −0.11 | 0.19 | 0.15 (0.08) | 0.01 | 0.32 | 3.10 | |

| Weight Stigma → WBI → | |||||||||||

| Binge Eating | −0.07 (0.12) | −0.29 | 0.16 | 0.28 (0.16) | −0.02 | 0.61 | 0.25 (0.17) | −0.08 | 0.60 | - | |

| Purging | 0.16 (0.06) | 0.04 | 0.29 | 0.18 (0.10) | −0.01 | 0.38 | 0.05(0.13) | −0.22 | 0.30 | - | |

| Restricting | −0.08 (0.12) | −0.32 | 0.15 | −0.07 (0.14) | −0.35 | 0.19 | −0.18 (0.13) | −0.46 | 0.03 | - | |

| Excessive Exercise | 0.05 (0.12) | −0.17 | 0.28 | −0.20 (0.13) | −0.47 | 0.05 | −0.15 (0.13) | −0.42 | 0.08 | - | |

| Muscle Building | −0.01 (0.09) | −0.18 | 0.16 | −0.10 (0.10) | −0.31 | 0.10 | −0.03 (0.11) | −0.27 | 0.18 | - | |

| Weight Stigma → WBI → Body Dissatisfaction | 1.95 (0.20) | 1.59 | 2.37 | 1.58 (0.22) | 1.22 | 2.06 | 1.34 (0.19) | 1.00 | 1.73 | - | |

Note. WBI = weight bias internalization; Weight stigma = experienced weight stigma; BMI = body mass index; UW/AW = underweight/average weight; OW = overweight; OB = obese; CI = 95% bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit; - = effect not directly involved in the central mediational paths of interest, difference tests not run to avoid increasing Type I error; all Wald χ2 difference tests for the assessed direct and indirect effects were non-significant.

UW/AW vs. OW.

UW/AW vs. OB.

OW vs. OB.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

4. Discussion

Weight stigma has consistently been associated with adverse physical and mental health outcomes, including ED symptoms (Alimoradi et al., 2019; Daly et al., 2019; Emmer et al., 2020; Puhl & Suh, 2015a,b; Pearl & Puhl, 2018; Vartanian & Porter, 2016). Notably, existing weight stigma theories used to explain these interrelations have not explicitly accounted for body dissatisfaction, a well-established correlate of both weight stigma and ED symptoms (Durso et al., 2012, 2016; Pearl & Puhl, 2014; Pearl & Puhl, 2018; Puhl & Suh, 2015a), and have largely been limited to explaining how weight stigma perpetuates disinhibited eating behaviors (e.g., binge eating) among individuals with elevated BMIs. In an effort to provide a more comprehensive understanding of associations between weight stigma and ED symptoms that are applicable to individuals across the weight spectrum, the present study tested a theoretical model in which weight stigma experiences sequentially mapped onto weight bias internalization, body dissatisfaction, and five ED symptoms: binge eating, purging, restricting, excessive exercise, and muscle building behaviors. Subsequently, whether these patterns of association differed for individuals based on BMI classification was assessed. The present results provide support for the assessed model overall and for individuals in each BMI class and suggest that, although there were differences in these patterns of association as a function of individuals’ BMIs, these differences were limited and somewhat circumscribed.

4.1. Explanatory Model

The present results provide initial support for the assessed weight stigma and ED symptoms model among all participants. Specifically, weight stigma experiences were sequentially associated with higher levels of weight bias internalization, body dissatisfaction, and all five ED symptoms outcomes (binge eating, purging, restricting, excessive exercise, muscle building). These results extend previous research that has supported weight bias internalization as an explanatory factor within associations between weight stigma experiences and singular ED behavior outcomes at a time (Himmelstein et al., 2019; O’Brien et al., 2016; Sikorski et al., 2015) by underscoring the importance of also accounting for body dissatisfaction within these associations. Of note, explicitly modeling body dissatisfaction aligns with prominent ED theories that support body dissatisfaction as an established ED risk factor, as well as evidence that weight stigma experiences and weight bias internalization exhibit robust positive associations with body dissatisfaction (Durso et al., 2012, 2016; Pearl & Puhl, 2014; Pearl & Puhl, 2018; Puhl & Suh, 2015a). These findings also build upon existing weight stigma theories that only peripherally account for the role of body dissatisfaction as a factor that impacts weight stigma-ED symptom associations (Ratcliffe & Ellison, 2015; Sikorski et al., 2015; Tomiyama, 2014). It will be important for future research to corroborate these initial findings via longitudinal research and also to determine whether they extend to the state-based level of analysis via ecological momentary assessment. This latter evidence will determine whether individuals’ experiences of weight stigma in their daily lives similarly map onto concurrent engagement in the assessed ED behaviors, and whether these patterns of association are explained by higher momentary levels of weight bias internalization and body dissatisfaction.

Accounting for a broad spectrum of ED behaviors within a single explanatory model in the present study also increases the generalizability of existing weight stigma theories that have generally focused on weight stigma and disinhibited eating associations among individuals with elevated BMIs (Ratcliffe & Ellison, 2015; Sikorski et al., 2015; Tomiyama, 2014). For example, the cyclic obesity/weight-based stigma (COBWEBS) model suggests that weight stigma experiences are associated with increases in stress which, in turn, propagates increased eating, cortisol levels, and weight gain, which then begets additional weight stigma experiences in a cyclical manner (Tomiyama, 2014). Notably, this focus on eating behaviors that result in weight gain does not account for established evidence that eating pathology has transdiagnostic properties that commonly result in individuals engaging in multiple ED behaviors, rather than disinhibited eating alone (Fairburn et al., 2003). It is important for weight stigma research to uphold this broader focus and continue to account for this central tenet of prominent ED theories to further the understanding of how weight stigma maps onto a variety of ED behaviors.

Including multiple ED behaviors in a single model also permits the determination of the relative contribution of measures of weight stigma, weight bias internalization, and body dissatisfaction to explaining each assessed ED behavior outcome. Specifically, in both samples, the largest amount of variance was accounted for by the path culminating in binge eating (large effect sizes), followed by purging, restricting (medium effects), excessive exercise, and muscle building behaviors (small to medium effects). Of note, although the latter three behaviors accounted for a small to medium amount of variance, these effects were not negligible and warrant additional exploration, particularly given the lack of evidence seeking to explain associations between weight stigma and restricting, excessive exercise, and muscle building behaviors. For example, the collective influence of weight stigma experiences, weight bias internalization, and body dissatisfaction on heightened excessive exercise and/or muscle building behaviors may be especially relevant for boys and men (Murray et al., 2017) and the moderating influence of gender identity should be assessed.

4.2. Differences by Weight Classification

The assessed theoretical model exhibited good fit when individuals within the underweight/average weight, overweight, and obese BMI classes were examined separately, in line with evidence that adverse associations between weight stigma and ED symptoms are not limited to individuals with elevated BMIs (Schvey & White, 2015; Pearl & Puhl, 2018; Puhl & Suh, 2015a; Vartanian & Porter, 2016). Further, although the assessed model at large differed between individuals in these three weight classes, it did so in a circumscribed manner. Specifically, when controlling for the influence of weight stigma and weight bias internalization, a stronger association between greater body dissatisfaction and greater restricting ED behaviors was identified for participants in Sample 1’s (but not Sample 2’s) underweight/average weight BMI class compared to those in the overweight and obese weight classes. No other direct or indirect effects involved in the mediational paths of interest differed among individuals based on BMI classification in either assessed sample. Given that these BMI class differences were limited, it appears as though there are more similarities than differences in associations among weight stigma, weight bias internalization, body dissatisfaction, and varied ED symptoms outcomes for individuals across the weight spectrum. As an important extension of the present study, future research should determine whether these findings extend to clinical populations, including those with clinical and/or subclinical EDs and individuals seeking weight management interventions. Such evidence may be particularly important, given evidence that a sizable proportion of practitioners who work with individuals with EDs have been shown to exhibit weight bias towards clients with elevated body weights (Puhl et al., 2014).

4.3. Clinical Implications

The present findings have various clinical implications that can inform weight stigma interventions. First, these results indicate that weight bias internalization and body dissatisfaction are important factors to target within these treatments, and initial evidence suggests that interventions that uphold a cognitive behavioral therapy (Pearl et al., 2018) or acceptance and commitment therapy (Griffiths et al., 2018) perspective may prove particularly helpful in decreasing the severity of these two factors. Second, the present findings suggest that screening efforts seeking to identify individuals susceptible to experiencing adverse consequences of weight stigma should not be limited to those with elevated BMIs. Wide-spread efforts to screen individuals across the weight spectrum are consequently needed and may include actions such as administering brief surveys (e.g., the SSI-B, the WBIS-M; Pearl & Puhl, 2014; Vartanian, 2015) to all individuals in doctors’ offices, college health centers, and community centers.

4.4. Limitations

Although the present study has various strengths, such as participants’ racial diversity and the implications of the present findings for furthering the understanding of mechanisms underlying weight stigma-eating pathology associations for individuals with varied BMIs, certain limitations warrant attention. First, most participants identified as female and heterosexual. Future research with a more gender and sexually diverse sample of participants is consequently needed to increase the generalizability of these findings. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the present study precludes the ability to determine whether the assessed associations manifest longitudinally. Future prospective research is therefore needed to determine whether weight stigma maps onto increases in weight bias internalization, body dissatisfaction and, in turn, different types of ED symptoms over time. Such evidence may be particularly important in enhancing the understanding of the directionality of associations between weight bias internalization and both experienced weight stigma and body dissatisfaction. For example, whereas the assessed path model examined experienced weight stigma as a predictor of weight bias internalization, in line with existing theories in this area, some data also suggests that a subset of individuals report elevated weight bias internalization in the absence of prior weight stigma experiences (Puhl et al., 2018). Thus, examining the temporality of these associations via future longitudinal research may enhance the understanding of the pathogenesis of weight stigma and its physical and mental health implications among those for whom current theoretical tenets do not aptly account for. Third, the low rate of endorsement for experienced weight stigma in Sample 1 using the dichotomous EDDS weight stigma measure serves as a limitation of the present study. However, this concern is limited by the notion that the overall pattern of results was replicated in Sample 2, which used a more robust experienced weight stigma measure (SSI-B).

4.5. Conclusions

The present study examined a novel theoretical model wherein weight stigma experiences were associated, in turn, with weight bias internalization, body dissatisfaction, and five ED symptoms outcomes: binge eating, purging, restricting, excessive exercise, and muscle building behaviors. Whether these patterns of association differed for individuals based on BMI classification was also assessed. The present results provide support for the assessed model overall and for individuals with underweight/average weight, overweight, and obese BMIs, separately. Further, although there were differences in these patterns of association as a function of individuals’ BMIs, these disparities were limited and circumscribed. Collectively, these findings suggest that the adverse impact of weight stigma on ED symptoms is not limited to individuals with elevated BMIs and that these associations can be explained by the same mechanisms.

Highlights.

A weight stigma model for people across the weight spectrum was assessed.

The assessed model was supported for individuals with different BMIs.

Internalization and body concerns mediated weight stigma-eating pathology paths.

These results extend existing weight stigma and disinhibited eating theories.

Weight stigma programs should target weight bias internalization and body concerns.

Funding acknowledgement

This work was completed in part with support from the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under award number F31MH120982 to Kelly A. Romano. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of interest

None.

References

- Alimoradi M, Abdolahi M, Aryan L, Vazirijavid R, & Ajami M (2016). Cognitive behavioral therapy for treatment of adult obesity. International Journal of Medical Reviews, 3, 371–379. [Google Scholar]

- Alimoradi Z, Golboni F, Griffiths MD, Broström A, Lin CY, & Pakpour AH (2019). Weight-related stigma and psychological distress: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Nutrition. 10.1016/j.clnu.2019.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boswell RG, & White MA (2015). Gender differences in weight bias internalisation and eating symptoms in overweight individuals. Advances in Eating Disorders, 3, 259–268. 10.1080/21662630.2015.1047881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly M, Sutin AR, & Robinson E (2019). Perceived weight discrimination mediates the prospective association between obesity and physiological dysregulation: Evidence from a population-based cohort. Psychological Science, 30, 1030–1039. 10.1177/0956797619849440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darlington RB, & Hayes AF (2016). Regression analysis and linear models: Concepts, applications, and implementation. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Durso LE, Latner JD, & Ciao AC (2016). Weight bias internalization in treatment-seeking overweight adults: Psychometric validation and associations with self-esteem, body image, and mood symptoms. Eating Behaviors, 21, 104–108. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durso LE, Latner JD, White MA, Masheb RM, Blomquist KK, Morgan PT, & Grilo CM (2012). Internalized weight bias in obese patients with binge eating disorder: Associations with eating disturbances and psychological functioning. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 45, 423–427. 10.1002/eat.20933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmer C, Bosnjak M, & Mata J (2020). The association between weight stigma and mental health: A meta- analysis. Obesity Reviews, 21, e12935. 10.1111/obr.12935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, & Shafran R (2003). Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: A “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41, 509–528. 10.1016/S0005-7967(02)00088-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbush KT, Wildes JE, Pollack LO, Dunbar D, Luo J, Patterson K, … & Bright A (2013). Development and validation of the Eating Pathology Symptoms Inventory (EPSI). Psychological Assessment, 25, 859–878. 10.1037/a0032639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths C, Williamson H, Zucchelli F, Paraskeva N, & Moss T (2018). A systematic review of the effectiveness of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) for body image dissatisfaction and weight self-stigma in adults. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 48(4), 189–204. 10.1007/s10879-018-9384-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himmelstein MS, Puhl RM, & Quinn DM (2019). Overlooked and understudied: health consequences of weight stigma in men. Obesity, 27, 1598–1605. 10.1002/oby.22599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York, NY: Guilford publications. [Google Scholar]

- Linardon J, Wade TD, de la Piedad Garcia X, & Brennan L (2017). The efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for eating disorders: A systematic review and meta- analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85, 1080–1094. 10.1037/ccp0000245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meadows A, & Higgs S (2020). A bifactor analysis of the Weight Bias Internalization Scale: What are we really measuring? Body Image, 33, 137–151. 10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SB, Nagata JM, Griffiths S, Calzo JP, Brown TA, Mitchison D, … & Mond JM (2017). The enigma of male eating disorders: A critical review and synthesis. Clinical Psychology Review, 57, 1–11. 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien KS, Latner JD, Puhl RM, Vartanian LR, Giles C, Griva K, & Carter A (2016). The relationship between weight stigma and eating behavior is explained by weight bias internalization and psychological distress. Appetite, 102, 70–76. 10.1016/j.appet.2016.02.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearl RL, & Puhl RM (2014). Measuring internalized weight attitudes across body weight categories: Validation of the modified weight bias internalization scale. Body Image, 11, 89–92. 10.1016/j.bodyim.2013.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearl RL, & Puhl RM (2018). Weight bias internalization and health: A systematic review. Obesity Reviews, 19, 1141–1163. 10.1111/obr.12701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearl RL, Hopkins CH, Berkowitz RI, & Wadden TA (2018). Group cognitive-behavioral treatment for internalized weight stigma: A pilot study. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 23, 357–362. 10.1007/s40519-016-0336-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearl RL, Puhl RM, & Dovidio JF (2015). Differential effects of weight bias experiences and internalization on exercise among women with overweight and obesity. Journal of Health Psychology, 20, 1626–1632. 10.1177/1359105313520338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhl RM, Himmelstein MS, & Quinn DM (2018). Internalizing weight stigma: Prevalence and sociodemographic considerations in US adults. Obesity, 26(1), 167–175. 10.1002/oby.22029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhl RM, Latner JD, King KM, & Luedicke J (2014). Weight bias among professionals treating eating disorders: attitudes about treatment and perceived patient outcomes. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47(1), 65–75. 10.1002/eat.22186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhl R, & Suh Y (2015a). Stigma and eating and weight disorders. Current Psychiatry Reports, 17, 10. 10.1007/s11920-015-0552-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhl R, & Suh Y (2015b). Health consequences of weight stigma: Implications for obesity prevention and treatment. Current Obesity Reports, 4, 182–190. 10.1007/s13679-015-0153-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe D, & Ellison N (2015). Obesity and internalized weight stigma: A formulation model for an emerging psychological problem. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 43, 239–252. 10.1017/S1352465813000763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schvey NA, & White MA (2015). The internalization of weight bias is associated with severe eating symptoms among lean individuals. Eating Behaviors, 17, 1–5. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski C, Luppa M, Luck T, & Riedel- Heller SG (2015). Weight stigma “gets under the skin”—evidence for an adapted psychological mediation framework—a systematic review. Obesity, 23, 266–276. 10.1002/oby.20952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomiyama AJ (2014). Weight stigma is stressful: A review of evidence for the Cyclic Obesity/Weight-Based Stigma model. Appetite, 82, 8–15. 10.1016/j.appet.2014.06.108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vartanian LR (2015). Development and validation of a brief version of the Stigmatizing Situations Inventory. Obesity Science & Practice, 1, 119–125. 10.1002/osp4.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vartanian LR, & Porter AM (2016). Weight stigma and eating behavior: A review of the literature. Appetite, 102, 3–14. 10.1016/j.appet.2016.01.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vartanian LR, Pinkus RT, & Smyth JM (2018). Experiences of weight stigma in everyday life: Implications for health motivation. Stigma and Health, 3, 85–92. 10.1037/sah0000077 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, & Anderson NB (1997). Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology, 2, 335–351. 10.1177/135910539700200305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YK, & Berry DC (2018). Impact of weight stigma on physiological and psychological health outcomes for overweight and obese adults: a systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 74, 1030–1042. 10.1111/jan.13511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]