Introduction

Pregnancy presents a vulnerable period for depressive episodes before, during and after childbirth. As early as 700 BC, Hippocrates described women having emotional difficulties after giving birth, a problem that came to be termed, “the baby blues” and eventually, “postpartum depression.” Symptoms include depressed mood, lack of interest, weight changes, feelings of guilt and worthlessness, difficulty in concentration and suicidal thoughts. Although the concept became increasingly recognized over the centuries, it was not until 1994 that the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: 4th Edition (DSM-IV) included the postpartum onset of depression as a formally, medically defined concept in the United States.1 Today it is recognized that pregnancy and perinatal depression (PPD) may be a more accurate term as the phenomenon can occur at any time surrounding pregnancy and delivery, not just postpartum. The new PPD definition in the 5th edition of the DSM specifies the phenomenon as depression, “with perinatal onset” if the onset of mood symptoms occurs during the pregnancy or in the four weeks following delivery.2 Still, the definition may fail to capture appropriate cases, because women can experience perinatal depression up to 12 months after giving birth. Generalizing the phenomenon into one category may ignore distinct needs of women who experience depression in the antepartum versus postpartum periods.3

Childbirth experiences can affect risk for PPD. As part of the childbirth experience, labor analgesia and anesthesia can influence childbirth experiences of pain and suffering. Childbirth is one of the most painful experiences a woman will encounter in her lifetime. There is a growing body of research on the influence of analgesia on PPD risk during this vulnerable period, as it may have protective, neutral, or harmful effects on individuals. This review will summarize the epidemiology of PPD, its natural history, comorbidities, and treatments, and will appraise existing knowledge on the relative contributions of pain, suffering, and analgesia to overall PPD risk.

Natural Progression & Potential Etiologies

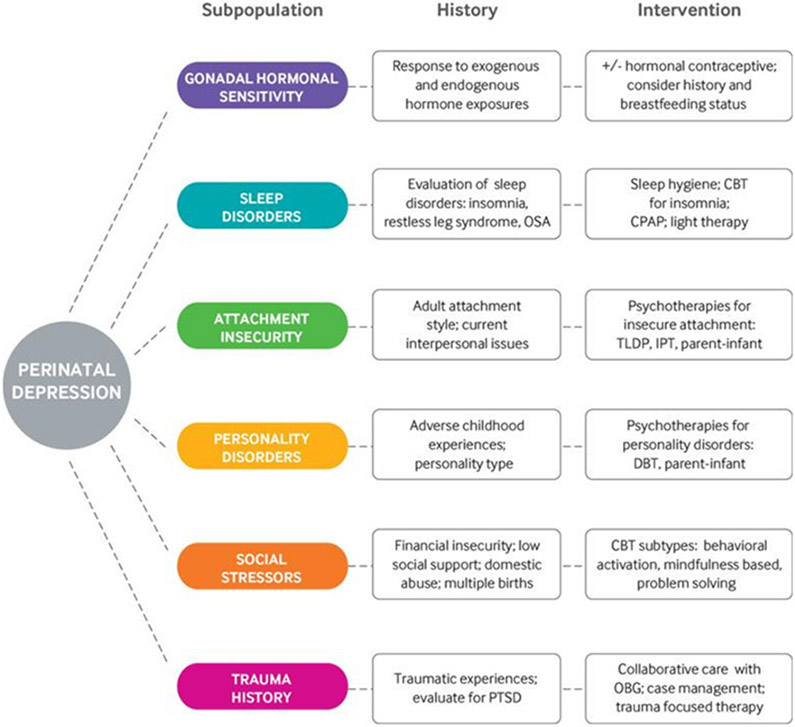

Subpopulations of women who experience PPD exhibit distinct clinical characteristics and include gonadal hormonal sensitivity, sleep disorders, attachment insecurity, personality disorders, social stressors, and trauma history (Figure 1). After childbirth, an abrupt and profound gonadal steroid withdrawal accompanies placental separation. These significant hormonal fluctuations most likely play a significant role in peripartum mood disorders for certain sub-populations.4 It is considered normal in the immediate post-birth period to feel low mood, emotional lability, irritability, and anxiety. These symptoms typically peak two to five days and resolve by two weeks postpartum. This period became known as the “baby blues” and is distinct from PPD in that it does not impact global functioning and self-remits. The incidence of “baby blues” is extremely high and 45-85% of postpartum mothers experience it.5 Pregnant women should be aware that it is common and normal in the short-term, but that it is not normal for these feelings to persist or to be so intense that it impacts their daily function or ability to care for their newborn. When symptoms fail to resolve after two weeks, have psychotic features, or significantly impacts daily function, PPD may be manifesting. The highest rates of postpartum depressive episodes occur in the first few months after delivery.6 The rate of recurrence of postpartum depression in subsequent pregnancies is approximately 50%.7

Figure 1.

Personalized non-drug treatment recommendations for sub-populations of patients with perinatal depression based on clinical characteristics.

CBT=cognitive behavioral therapy; CPAP=continuous positive airway pressure; DBT=dialectical behavioral therapy; IPT=interpersonal psychotherapy; OBG=obstetrics/gynecology; OSA=obstructive sleep apnea; PTSD=post-traumatic stress disorder; TLDP=time limited dynamic psychotherapy.

Although “perinatal onset of depression” functions as a specifier in the DSM-V rather than a unique disorder, there are many who believe that the etiology of PPD may be distinct from other forms of depression. Sex hormones play an important role in the body regulating both biological systems and mediating neuro-cognitive processes such as emotions, affect regulation, and cognition. The hormonal hypothesis suggests that the extensive hormonal changes after birth may be responsible and this has been confirmed with animal studies that demonstrated depression like behavior in animals subjected to progesterone and estradiol withdrawal.8 Not every postpartum woman exhibits PPD and it appears that subsets of women are especially vulnerable to hormonal fluctuations and suffer a “hormone-sensitive” PPD phenotype that is distinct.4 This idea is supported by studies showing that hormonal therapy is effective in treatment of PPD.9 Still the evidence is inconclusive: other studies have failed to find an association between sex hormone levels and PPD symptoms.

PPD is likely heterogeneous and it is plausible that different etiologies of PPD co-exist. For example, a woman genetically vulnerable due to the hormone withdrawal following delivery also may be vulnerable due to social factors such as inadequate social and marital support. Alternative biologic explanations for PPD exist; alterations in thyroid function, pregnancy related immune system changes, breastfeeding and related oxytocin secretion, and sleep aberrations have been implicated in pathogenesis.4 A single, clear explanation for PPD has not arisen and a multi-factorial interaction of multiple etiologies may be more likely.

Epidemiology

PPD is common worldwide. A 2018 meta-analysis of 291 studies estimated the pooled risk of PPD is 17.7%, or 1 in 6 new mothers.10 Any woman can develop PPD, including women with no prior history of depression who give birth to healthy full term infants.11 Low-resource countries find similar rates of PPD (11-21%) as high-resourced nations.12 The perinatal period is a time of vulnerability to develop a mood disorder, because mothers endure significant physical and hormonal changes while simultaneously being challenged by sleep deprivation, breastfeeding demands, postpartum pain and the daily struggles that accompany learning to care for a neonate.

The most significant risk factor for PPD is history of depression, whether it be prior perinatal depression or other depressive order. Other psychiatric diagnoses such as bipolar disorder and other mental illnesses increase the risk for PPD. Suboptimal pregnancy conditions such as stressful life events during the pregnancy and postpartum period, complications during childbirth, neonatal medical conditions, lack of positive feelings about the pregnancy, lack of emotional or social support, and substance abuse problems also increase one’s risk.10

The ramifications of PPD are not limited to the new mother. Infants and children may also be adversely impacted. Mothers who suffer from PPD may exhibit emotional detachment and may have problems breastfeeding;13 emotional detachment can negatively impact brain development and hinder cognitive and motor milestones in their children.14 Prompt recognition and treatment are important to mitigate these potential public health problems.

PPD severity can progress to the point of suicide. However, measuring the impact of maternal self-harm and mortality is challenging. Maternal deaths from suicide and overdose are often omitted from published rates of maternal mortality, despite growing attention to their prevalence.15 Omissions may stem from the fact that suicide is often considered incidental or indirectly related to pregnancy, compared with other direct pregnancy causes of death such as infections or hemorrhage. One study investigating causes of maternal death found that 10.2% of maternal deaths were due to such “indirect” causes such as suicide, amounting to just over 31,000 maternal deaths worldwide in the year 2013.16 A Finnish study examined peripartum suicide and found the mortality rate to be 3.3/100,00. This rate was notably higher at 21.8/100,000 after termination of a pregnancy.17 A major risk factor for peripartum suicide is history of prior suicide attempt, and in contrast, living with a partner and perceived social support are protective.18

Interactions with Psychiatric Comorbidities

Anxiety

Compared with other forms of depression, PPD has a high frequency of co-existing anxiety and anxious symptoms but is distinct from the diagnosis of postpartum anxiety (PPA).19,20 However, anxiety if often missed during screening: only 1 in 3 women with PPA is identified when the screening is for PPD alone.21 Similar to depression, anxiety can occur at any time during the perinatal period, and patients suffering from anxiety disorders during pregnancy are at increased risk for PPD.22 Unlike depressive symptoms that have peak incidence in the postpartum period, multiple anxiety symptoms have the highest incidence during pregnancy and often decreases after birth.23,24

Major Depressive Disorder

One of the primary risk factors for developing PPD is a history of major depressive disorder (MDD). Many women with a history of MDD are euthymic when starting pregnancy. The rate of PPD in women with a history of depression is around 25-40%, significantly higher than the rate in the general population.25 In one study, women with higher depression scores on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale in the third trimester progressed to significantly higher rates of persistent depression in the postpartum period, compared to women who were euthymic in the third trimester.26 As such, women with a history of MDD should be proactively counseled about their risks for PPD and followed closely to monitor symptoms and to initiate treatment early in the course should depression develop. Counseling and treatment should begin prior to childbirth as the symptoms of MDD may begin during pregnancy.

Bipolar Disorder & Bipolar PPD

Childbirth is a common period for bipolar disorder to arise or become exacerbated.27 Two thirds of mothers with bipolar disorder experienced an affective episode in the postpartum period, and episodes are often depressive in nature.28,29 Because bipolar disorder has very distinct characteristics and treatment, the diagnosis must be carefully considered in any differential for perinatal depression especially prior to starting treatment. There is potential for harm if a mother suffering from bipolar disorder is misdiagnosed as PPD alone, because the treatments are different. Traditional antidepressants used for PPD but applied to a patient with bipolar disorder, risk of inducing a manic episode. Appropriate treatments for bipolar PPD would include antidepressants in combination with a mood stabilizer such as lithium, quetiapine, and lamotrigine. Risk factors for bipolar depression in the postpartum period include younger age, first onset of depression after childbirth, atypical depressive symptoms, and a history of bipolar disorder in a first-degree family member.30 When postpartum depression is bipolar rather than unipolar, there is a significantly higher risk of postpartum psychosis.31

Postpartum Psychosis

One of the most serious mental health conditions arising in the postpartum period is psychosis. Postpartum psychosis is considered a psychiatric emergency. It is rare with a global prevalence between 0.89 to 2.6 in 1000 women32 Symptoms can include hallucinations, delusions, mood swings, insomnia, and severe agitation. Risks are higher in women with a previous diagnosis of bipolar disorder, but many women with postpartum psychosis have not had previous episodes of psychosis, depression, or other serious mental illness. Almost 1 in 20 women may try to harm themselves or their child.33 Prompt treatment may include a combination of inpatient hospitalization, therapy, and anti-psychotic medication.

Trauma and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

Traumatic experiences that can potentially lead to Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and depression are common during childbirth. A cross sectional multi-center study in Iran showed that the prevalence of traumatic birth experience was as high as 37%. In that study, one of the significant risk factors for traumatic experience was the absence of analgesia during labor (OR 4.24, CI 2.12-8.50, P<.001).34 A meta-analysis estimated the prevalence of PTSD following childbirth to be 3.1% overall, and 15.7% in high-risk groups.35 Women requiring an emergency team response during their labor and delivery may have higher postpartum PTSD scores.36 Interventions for secondary prevention of PTSD after a traumatic birth include debriefing, encouragement of early skin-to-skin contact, expressive writing, and more formal structured psychological interventions. However, the evidence for these interventions remains inconclusive; no interventions have been found to be effective in preventing PTSD in these women, and in some subgroups, effectiveness is inconsistent.36

Labor Pain & Analgesia: How Anesthesia May Affect PPD

Evidence Neuraxial Techniques are Protective Against PPD

Pain, analgesia, and depression are complex phenotypes, and so the relationships between obstetric pain, labor analgesia and PPD are also complex: some studies have suggested labor analgesia benefits by reducing PPD, while others have not found these relationships or have found more nuanced links. A few studies have suggested that epidural labor analgesia decreases risk for PPD. A prospective cohort study of 214 parturients found that receiving ELA was associated with a significant decrease in the rate of PPD with an odds ratio of 0.31 (95% CI 0.12 to 0.82). The PPD rate at 6 weeks after delivery was lower in the ELA group (14%) compared to the non-ELA group (34.6%).37 Similarly, another study found a lower incidence of PPD in women who received ELA (10%) versus those who did not (19.3%).38 In a longitudinal, 3-year cohort investigation using Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) scores of 508 women with 72.4% ELA rate, at 2 years after delivery there were decreased depression scores in the group who received neuraxial anesthesia with an odds ratio of 0.45 (95% CI 0.23 to 0.89).39 Cortisol levels may potentially explain the relationship between pain/stress reduction and PPD risk: women who received ELA were found to have reduced serum cortisol levels as well as lower PPD rates at 6 weeks postpartum.40

However, other studies have found more complex relationships between birth expectations, ELA use, and PPD. A prospective observational study measured ELA use and whether pre-delivery ELA plans for were achieved. In the group who planned to receive ELA and did in fact end up receiving ELA, there was a protective effect against PPD with an OR of 0.92 (95% CI 0.86 to 0.99; P=0.022). However, women who planned to forgo ELA but ended up receiving ELA had increased PPD risk. A potential explanation for this finding is that a more difficult labor and delivery may necessitate an altered plan for ELA, and those obstetric characteristics alone may have been associated with increased PPD risk independent of ELA use or non-use. Another possible explanation for this finding is that unmet expectations or a sense of personal failure after unplanned ELA may result in PPD.41 Altogether, expectations management for labor and delivery may be a potential benefit for all women experiencing childbirth.

Evidence Neuraxial Techniques Have No Impact on PPD

Some studies have found ELA to have no influence on PPD rates.42 For example, in low resource areas with low ELA utilization, PPD rates appear to be similar to those in areas with higher ELA utilization.12,43 A larger longitudinal cohort study of 1503 women in Sweden found that ELA was not associated with PPD scores at 6 weeks postpartum. This study attempted to isolate the “direct” effect of ELA on PPD through directed acyclic graphs and found no correlation between ELA and PPD, but an indirect relationship between ELA and PPD through an effect on childbirth experience.44,45 A limitation of examining these relationships from a population level – be that by a large data set, or by comparing PPD rates in low- and high-resource countries with differing labor analgesia utilization rates – is that it misses the opportunity to detect individual-level influences in these relationships. In other words, these kinds of large data studies will not be able to speak to an individual patient’s susceptibility, resilience, or neutrality to pain-associated PPD.

Evidence Good Labor Pain Control is Protective Against PPD

Rather than a decision to use or not use ELA -- which can be affected by factors other than pain including fetal complications or birth circumstances -- some investigations have instead investigated the quality of labor analgesia as a primary predictor for PPD. One study found that between greater improvements in labor pain control was associated with lower PPD scores at six weeks postpartum.46 This study was important because it focused on the treatment effect itself – effective pain control – rather than use or non-use of a certain treatment (e.g., ELA) in protecting against PPD. Although higher-quality analgesia did seem to be protective, it was less contributory than other factors known to increase risk for PPD, such as a history of depression or anxiety.

Studies on Peripartum Pain as a Risk Factor for PPD

A well-established connection between chronic pain and depression supports bidirectional relationships: chronic pain begets depression and depression begets chronic pain. Because of these known connections between depression and pain in chronic settings, investigators have questioned whether these relationships are also true in acute settings. For example, studies have queried whether acute pain, such as pain after delivery, is associated with PPD. In one multi-center study of 1288 women, the severity of acute pain within 36 hours of childbirth was significantly correlated with PPD.47 Women experiencing severe postpartum pain had a 2.5 fold increase in risk of developing persistent pain and a 3.0 fold increase in risk of developing PPD.47 However, some studies have found that persistent postpartum pain is uncommon 6 and 12 months after birth,47,48 and that this low frequency may raise questions about the plausibility of a relationship between postpartum pain and PPD. The inconsistency in these relationships within the published literature has led to several follow-up investigations.

To assess these potential relationships between acute perinatal pain, and PPD, a prospective observational study was conducted and found that pain at all perinatal time points (i.e., prenatal, labor and postpartum) were independently linked to PPD at 6 weeks postpartum.49 In this study, subjects were recruited during the third trimester, completed a baseline inventory on pain assessments, recorded pain scores, satisfaction, and expectations questions at hourly intervals during labor, and were followed in the postpartum period for pain and depression screening. The emotional burden of acute labor pain was associated with higher six-week EPDS scores (P=0.002). The relationship was not affected by labor satisfaction or expectations. In the pre- and postnatal periods, higher pain scores also independently predicted higher depression scores at 6 weeks postpartum. Notably, this association between pain and PPD was even stronger among African American women and women planning to receive ELA.

Although a clear biological explanation for the observed relationship between labor pain and depression is unknown, one study offers a genetic explanation. A prospective study collected saliva samples of laboring women who provided prospective pain and depression scores throughout labor until 6 weeks postpartum. Fifty-nine single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) known to be highly correlative with depressive diagnoses were investigated for their relationships with perinatal pain ratings. Results found one SNP (rs4633, a synonymous single-nucleotide polymorphism in COMT) to be associated with higher “pain right now” ratings (“what is your pain right now) at 6 weeks postpartum and two other SNPs (rs1135349, a SNP within a small noncoding RNA that has many prior associations for depression; and rs7548151, intronic in ASTN1) to be associated with a higher score for emotional valence of labor pain.50 Ongoing research will continue to identify the molecular basis of both acute pain and PPD.

Summary: Pain, Analgesia, and PPD

Perinatal pain and PPD appear to be related; however, individual susceptibility or resilience requires clarification. Underlying biological mechanisms common to both pain and depression may be explanatory in these relationships and may point to potential avenues for novel treatment discovery. Further, existing studies have used screening tools and speak to PPD symptomatology but not necessarily a clinical diagnosis of PPD; nevertheless, high depression scores detected in some of these studies is still evidence of poor maternal adjustment or recovery and should be cause for pause. Future investigations should focus less on ELA use or non-use and more on the role of perinatal pain and stress on PPD risk, or the risk of poor postpartum adjustment and recovery overall.

Response and Treatments

ACOG Response

In the United States and other high-resource settings, new mothers are frequently subjected to short postpartum hospital stays, isolating maternity leaves, and lack of formal or informal maternal support. Typically, a single follow up visit at 6 weeks is the only maternal medical visit in the postpartum period. Conversely, numerous cultures around the world encompass social traditions emphasizing an initial prolonged period of rest and recovery after childbirth while the local community supports the new mothers.51 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has raised a focus on maternal mental and physical well-being in the postpartum period and recognizes that the current approaches are often insufficient to meet maternal needs. Consequently, ACOG has proposed a “fourth trimester” encompassing the first 100 days after delivery and recommending that postpartum care be an ongoing process.52 Successful implementation of “fourth trimester” bundles may help provide the structural support needed to improve maternal mental health that is so desperately needed.

Psychotherapy

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is common for treatment of PPD, either alone or in combination with pharmacotherapy.53 The primary principle of CBT is that depression often include unhelpful patterns of thought and behavior, and that individuals can learn better ways of coping and thereby improve daily functioning in their lives. Trained mental health professionals help patients with depression gain strategies like stress management, goal setting and problem solving. Several trials have shown that CBT increases likelihood of PPD remission.53 The therapy appears successful regardless of timepoint of initiation: during pregnancy or in the postpartum period.53 Limitations of CBT are that women must have access to the therapy and need to participate. To the latter point, emotional detachment symptoms in severe cases of PPD may limit the utility of CBT alone, and psychotherapy may need to be combined with pharmacotherapy. The US Preventative Services Task Force recommends use of CBT in treatment of PPD.53

Interpersonal therapy has also been utilized in the treatment of PPD.54 It focuses on interpersonal relationships. It identifies deficits like social isolation or unhelpful relationships, assists in processing relationships related to grief, and helps the patient move through difficult life transitions. In Interpersonal therapy, the focus is on the current situation rather than on past events. It has been shown to shorten the time to recovery and prolong remission in PPD.55

A third method of therapy is mother-infant therapy. For some mothers, to adequately treat PPD the focus may be better spent on the mother-infant dyad rather than on the mother alone.56 Many hospitals have set up therapy structures where women struggling with PPD bring their infants. The therapy may be individual or done as a group with other new mothers and babies. A meta-analysis of 13 trials has shown this approach to be effective in reducing standardized mean depressive scores particularly in the short term.57

Pharmacotherapy

Treatment of maternal depression during pregnancy can include medications, talk therapy, light therapy and rarely, electroconvulsive therapy or repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. Although there are concerns about effects of selective serotonergic reuptake inhibitors on the developing human brain, current recommendations for management of depression during pregnancy include continuation of pharmacotherapy and even titration to symptom exacerbation, to reduce the risk of harm associated with untreated maternal depression.58

Many non-pregnancy specific depression medications are also used in the treatment of perinatal depression. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (e.g. escitalopram, sertraline), selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (e.g. desvenlafaxine, venlafaxine), adjunctive antipsychotics (e.g. aripirazole) and others (e.g. buproprion) are effective for PPD.59 Sertraline is a medication with a long history of use during lactation, and is often used as a first-line agent for PPD in a lactating mother.58 Although these antidepressants are not specifically FDA approved for PPD, their effectiveness in treating major depressive disorder is well established, and women have exhibited good response with decreased symptoms. The medications can be used on their own or in combination with psychotherapy depending on feasibility and the specific depression subtype.

Hormonal Treatments

Beyond traditional antidepressant medications, hormonal therapy may be helpful medication to combat PPD. Brexanolone is a formulation of allopregnanolone which is a steroid acting in the central nervous system to modulate GABA-A receptor activity.58,59 It is unique in that of all medications used to treat PPD, brexanolone is the only one that is FDA approved specifically for the treatment of PPD. It is a high-cost medication that has to be administered intravenously which impairs universal access and can present logistical challenges. Due to risk of sedation and loss of consciousness, there are significant restrictions, and its use must be under close monitoring.59 The drug has an unusually quick onset of response for PPD compared with other medications, and there is a significant reduction in both depressive and anxiety symptoms over the first 84 hours of therapy.9,58

Brexanolone is not the only hormonal therapy available for PPD. In an open label study, estradiol (3-8mg/day) had a good treatment response rate in women with PPD who had low serum estradiol levels and safety in breastfeeding was also established.60 A randomized controlled trial also showed that transdermal estrogen had superiority over placebo and 80% of treated women achieved an EPDS score <14 after 1 month.61 Ongoing research on other hormonal therapy such as oxytocin, estradiol, and allopregnanolone, will evaluate the effects of specific treatments on specific PPD symptoms.

Other Modalities

All women receiving treatment for PPD must be monitored closely for response, remission, and for symptoms that are severe and persistent. When a woman has incomplete response to psychotherapy and/or pharmacotherapy, other treatment modalities may need to be explored. Electroconvulsive therapy is safe both in pregnancy and the postpartum period and has demonstrated effectiveness in treating some treatment-refractory depression. Ketamine infusions have also been used to treat and prevent PPD with some women claiming significant improvements; however, results of studies on ketamine have been inconclusive.62,63

Alternative and Complimentary Therapies

Modalities such as acupuncture, yoga, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) and phototherapy have been investigated. A meta-analysis of acupuncture studies showed that acupuncture may significantly reduce Hamilton Depression Rating Scale scores.64 The quality of evidence for these interventions may be low; for example a review of rTMS evidence showed that despite positive published trials, well-executed studies were lacking.65 These interventions may offer a low potential for harm, and patients are often encouraged to seek any modality they may find helpful, particularly when used in combination with traditional therapy and medication-based approaches.

Dietary supplements have been investigated for depression treatment. Selenium, docosahexanoic acid, and eicosapentaenoic acid have been included in clinical trials, but currently there is insufficient evidence to routinely recommend these supplements.66 Saint John’s Wort is another medication commonly employed in the treatment of PPD and its use is especially prevalent in Europe. Its components are poorly excreted in breastmilk and no major adverse effects have been noted in breastfeeding infants although one study found a small increase in colic and lethargy.67 A major limitation in the United States is that such supplements do not require pre-marketing approval, and inconsistencies between concentrations in the supplement and those listed on the label do exist.67

Perinatal Depression: Conclusions

PPD is a problem that can arise at any time surrounding childbirth and symptoms mirror those of other depressive disorders. Depressed mood, lack of interest in pleasurable activities, guilt and hopelessness, sleep difficulties, weight changes and alterations in the mother-infant relationship can all occur. The DSM-V does not recognize it as a distinct depressive disorder but rather includes “with peripartum onset” as a specifier, although this approach has been criticized for its lack of recognizing distinctive features and subtypes of PPD. Treatment may include various forms of psychotherapy, antidepressants, hormonal therapies, or adjunctive and complimentary modalities. Pain, rather than use or non-use of labor analgesia, may be predictive of PPD, and maternal health will benefit from ongoing research that is focused on identifying which specific patients are more vulnerable to the ramifications of pain on adverse postpartum outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Dr. Lim is supported in part by the Department of Anesthesiology & Perioperative Medicine, and by the NIH Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health (K12HD043441)

References

- 1.Association AP: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-4, 4th edition. Washington, D.C., American Psychiatric Publishing, 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Association AP: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5, 5th edition. Washington, D.C., American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brummelte S, Galea LA: Postpartum depression: Etiology, treatment and consequences for maternal care. Horm Behav 2016; 77: 153–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schiller CE, Meltzer-Brody S, Rubinow DR: The role of reproductive hormones in postpartum depression. CNS Spectr 2015; 20: 48–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stewart DE, Vigod S: Postpartum Depression. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 2177–2186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Hara MW, McCabe JE: Postpartum depression: current status and future directions. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2013; 9: 379–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen LS, Wang B, Nonacs R, Viguera AC, Lemon EL, Freeman MP: Treatment of mood disorders during pregnancy and postpartum. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2010; 33: 273–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suda S, Segi-Nishida E, Newton SS, Duman RS: A postpartum model in rat: behavioral and gene expression changes induced by ovarian steroid deprivation. Biol Psychiatry 2008; 64: 311–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanes SJ, Colquhoun H, Doherty J, Raines S, Hoffmann E, Rubinow DR, Meltzer-Brody S: Open-label, proof-of-concept study of brexanolone in the treatment of severe postpartum depression. Hum Psychopharmacol 2017; 32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hahn-Holbrook J, Cornwell-Hinrichs T, Anaya I: Economic and Health Predictors of National Postpartum Depression Prevalence: A Systematic Review, Meta-analysis, and Meta-Regression of 291 Studies from 56 Countries. Front Psychiatry 2017; 8: 248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shorey S, Chee CYI, Ng ED, Chan YH, Tam WWS, Chong YS: Prevalence and incidence of postpartum depression among healthy mothers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res 2018; 104: 235–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohammad KI, Gamble J, Creedy DK: Prevalence and factors associated with the development of antenatal and postnatal depression among Jordanian women. Midwifery 2011; 27: e238–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dias CC, Figueiredo B: Breastfeeding and depression: a systematic review of the literature. J Affect Disord 2015; 171: 142–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van den Bergh BRH, van den Heuvel MI, Lahti M, Braeken M, de Rooij SR, Entringer S, Hoyer D, Roseboom T, Räikkönen K, King S, Schwab M: Prenatal developmental origins of behavior and mental health: The influence of maternal stress in pregnancy. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2020; 117: 26–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mangla K, Hoffman MC, Trumpff C, O'Grady S, Monk C: Maternal self-harm deaths: an unrecognized and preventable outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019; 221: 295–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kassebaum NJ, Bertozzi-Villa A, Coggeshall MS, Shackelford KA, Steiner C, Heuton KR, Gonzalez-Medina D, Barber R, Huynh C, Dicker D, Templin T, Wolock TM, Ozgoren AA, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, Abubakar I, Achoki T, Adelekan A, Ademi Z, Adou AK, Adsuar JC, Agardh EE, Akena D, Alasfoor D, Alemu ZA, Alfonso-Cristancho R, Alhabib S, Ali R, Al Kahbouri MJ, Alla F, Allen PJ, AlMazroa MA, Alsharif U, Alvarez E, Alvis-Guzmán N, Amankwaa AA, Amare AT, Amini H, Ammar W, Antonio CA, Anwari P, Arnlöv J, Arsenijevic VS, Artaman A, Asad MM, Asghar RJ, Assadi R, Atkins LS, Badawi A, Balakrishnan K, Basu A, Basu S, Beardsley J, Bedi N, Bekele T, Bell ML, Bernabe E, Beyene TJ, Bhutta Z, Bin Abdulhak A, Blore JD, Basara BB, Bose D, Breitborde N, Cárdenas R, Castañeda-Orjuela CA, Castro RE, Catalá-López F, Cavlin A, Chang JC, Che X, Christophi CA, Chugh SS, Cirillo M, Colquhoun SM, Cooper LT, Cooper C, da Costa Leite I, Dandona L, Dandona R, Davis A, Dayama A, Degenhardt L, De Leo D, del Pozo-Cruz B, Deribe K, Dessalegn M, deVeber GA, Dharmaratne SD, Dilmen U, Ding EL, Dorrington RE, Driscoll TR, Ermakov SP, Esteghamati A, Faraon EJ, Farzadfar F, Felicio MM, Fereshtehnejad SM, de Lima GM, Forouzanfar MH, França EB, Gaffikin L, Gambashidze K, Gankpé FG, Garcia AC, Geleijnse JM, Gibney KB, Giroud M, Glaser EL, Goginashvili K, Gona P, González-Castell D, Goto A, Gouda HN, Gugnani HC, Gupta R, Gupta R, Hafezi-Nejad N, Hamadeh RR, Hammami M, Hankey GJ, Harb HL, Havmoeller R, Hay SI, Pi IB, Hoek HW, Hosgood HD, Hoy DG, Husseini A, Idrisov BT, Innos K, Inoue M, Jacobsen KH, Jahangir E, Jee SH, Jensen PN, Jha V, Jiang G, Jonas JB, Juel K, Kabagambe EK, Kan H, Karam NE, Karch A, Karema CK, Kaul A, Kawakami N, Kazanjan K, Kazi DS, Kemp AH, Kengne AP, Kereselidze M, Khader YS, Khalifa SE, Khan EA, Khang YH, Knibbs L, Kokubo Y, Kosen S, Defo BK, Kulkarni C, Kulkarni VS, Kumar GA, Kumar K, Kumar RB, Kwan G, Lai T, Lalloo R, Lam H, Lansingh VC, Larsson A, Lee JT, Leigh J, Leinsalu M, Leung R, Li X, Li Y, Li Y, Liang J, Liang X, Lim SS, Lin HH, Lipshultz SE, Liu S, Liu Y, Lloyd BK, London SJ, Lotufo PA, Ma J, Ma S, Machado VM, Mainoo NK, Majdan M, Mapoma CC, Marcenes W, Marzan MB, Mason-Jones AJ, Mehndiratta MM, Mejia-Rodriguez F, Memish ZA, Mendoza W, Miller TR, Mills EJ, Mokdad AH, Mola GL, Monasta L, de la Cruz Monis J, Hernandez JC, Moore AR, Moradi-Lakeh M, Mori R, Mueller UO, Mukaigawara M, Naheed A, Naidoo KS, Nand D, Nangia V, Nash D, Nejjari C, Nelson RG, Neupane SP, Newton CR, Ng M, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, Nisar MI, Nolte S, Norheim OF, Nyakarahuka L, Oh IH, Ohkubo T, Olusanya BO, Omer SB, Opio JN, Orisakwe OE, Pandian JD, Papachristou C, Park JH, Caicedo AJ, Patten SB, Paul VK, Pavlin BI, Pearce N, Pereira DM, Pesudovs K, Petzold M, Poenaru D, Polanczyk GV, Polinder S, Pope D, Pourmalek F, Qato D, Quistberg DA, Rafay A, Rahimi K, Rahimi-Movaghar V, ur Rahman S, Raju M, Rana SM, Refaat A, Ronfani L, Roy N, Pimienta TG, Sahraian MA, Salomon JA, Sampson U, Santos IS, Sawhney M, Sayinzoga F, Schneider IJ, Schumacher A, Schwebel DC, Seedat S, Sepanlou SG, Servan-Mori EE, Shakh-Nazarova M, Sheikhbahaei S, Shibuya K, Shin HH, Shiue I, Sigfusdottir ID, Silberberg DH, Silva AP, Singh JA, Skirbekk V, Sliwa K, Soshnikov SS, Sposato LA, Sreeramareddy CT, Stroumpoulis K, Sturua L, Sykes BL, Tabb KM, Talongwa RT, Tan F, Teixeira CM, Tenkorang EY, Terkawi AS, Thorne-Lyman AL, Tirschwell DL, Towbin JA, Tran BX, Tsilimbaris M, Uchendu US, Ukwaja KN, Undurraga EA, Uzun SB, Vallely AJ, van Gool CH, Vasankari TJ, Vavilala MS, Venketasubramanian N, Villalpando S, Violante FS, Vlassov VV, Vos T, Waller S, Wang H, Wang L, Wang X, Wang Y, Weichenthal S, Weiderpass E, Weintraub RG, Westerman R, Wilkinson JD, Woldeyohannes SM, Wong JQ, Wordofa MA, Xu G, Yang YC, Yano Y, Yentur GK, Yip P, Yonemoto N, Yoon SJ, Younis MZ, Yu C, Jin KY, El Sayed Zaki M, Zhao Y, Zheng Y, Zhou M, Zhu J, Zou XN, Lopez AD, Naghavi M, Murray CJ, Lozano R: Global, regional, and national levels and causes of maternal mortality during 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014; 384: 980–1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karalis E, Ulander VM, Tapper AM, Gissler M: Decreasing mortality during pregnancy and for a year after while mortality after termination of pregnancy remains high: a population-based register study of pregnancy-associated deaths in Finland 2001-2012. Bjog 2017; 124: 1115–1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martini J, Bauer M, Lewitzka U, Voss C, Pfennig A, Ritter D, Wittchen HU: Predictors and outcomes of suicidal ideation during peripartum period. J Affect Disord 2019; 257: 518–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hendrick V, Altshuler L, Strouse T, Grosser S: Postpartum and nonpostpartum depression: differences in presentation and response to pharmacologic treatment. Depress Anxiety 2000; 11: 66–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jolley SN, Betrus P: Comparing postpartum depression and major depressive disorder: issues in assessment. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2007; 28: 765–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller RL, Pallant JF, Negri LM: Anxiety and stress in the postpartum: is there more to postnatal distress than depression? BMC Psychiatry 2006; 6: 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sutter-Dallay AL, Giaconne-Marcesche V, Glatigny-Dallay E, Verdoux H: Women with anxiety disorders during pregnancy are at increased risk of intense postnatal depressive symptoms: a prospective survey of the MATQUID cohort. Eur Psychiatry 2004; 19: 459–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heron J, O'Connor TG, Evans J, Golding J, Glover V: The course of anxiety and depression through pregnancy and the postpartum in a community sample. J Affect Disord 2004; 80: 65–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakić Radoš S, Tadinac M, Herman R: Anxiety During Pregnancy and Postpartum: Course, Predictors and Comorbidity with Postpartum Depression. Acta Clin Croat 2018; 57: 39–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Di Florio A, Forty L, Gordon-Smith K, Heron J, Jones L, Craddock N, Jones I: Perinatal episodes across the mood disorder spectrum. JAMA Psychiatry 2013; 70: 168–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suri R, Stowe ZN, Cohen LS, Newport DJ, Burt VK, Aquino-Elias AR, Knight BT, Mintz J, Altshuler LL: Prospective Longitudinal Study of Predictors of Postpartum-Onset Depression in Women With a History of Major Depressive Disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2017; 78: 1110–1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meltzer-Brody S, Howard LM, Bergink V, Vigod S, Jones I, Munk-Olsen T, Honikman S, Milgrom J: Postpartum psychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2018; 4: 18022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freeman MP, Smith KW, Freeman SA, McElroy SL, Kmetz GE, Wright R, Keck PE Jr.: The impact of reproductive events on the course of bipolar disorder in women. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63: 284–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Payne JL, Roy PS, Murphy-Eberenz K, Weismann MM, Swartz KL, McInnis MG, Nwulia E, Mondimore FM, MacKinnon DF, Miller EB, Nurnberger JI, Levinson DF, DePaulo JR Jr., Potash JB: Reproductive cycle-associated mood symptoms in women with major depression and bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 2007; 99: 221–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharma V, Doobay M, Baczynski C: Bipolar postpartum depression: An update and recommendations. J Affect Disord 2017; 219: 105–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones I, Craddock N: Bipolar disorder and childbirth: the importance of recognising risk. Br J Psychiatry 2005; 186: 453–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.VanderKruik R, Barreix M, Chou D, Allen T, Say L, Cohen LS: The global prevalence of postpartum psychosis: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2017; 17: 272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brockington I: Suicide and filicide in postpartum psychosis. Arch Womens Ment Health 2017; 20: 63–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghanbari-Homayi S, Fardiazar Z, Meedya S, Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi S, Asghari-Jafarabadi M, Mohammadi E, Mirghafourvand M: Predictors of traumatic birth experience among a group of Iranian primipara women: a cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019; 19: 182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grekin R, O'Hara MW: Prevalence and risk factors of postpartum posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2014; 34: 389–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Graaff LF, Honig A, van Pampus MG, Stramrood CAI: Preventing post-traumatic stress disorder following childbirth and traumatic birth experiences: a systematic review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2018; 97: 648–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ding T, Wang DX, Qu Y, Chen Q, Zhu SN: Epidural labor analgesia is associated with a decreased risk of postpartum depression: a prospective cohort study. Anesth Analg 2014; 119: 383–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suhitharan T, Pham TP, Chen H, Assam PN, Sultana R, Han NL, Tan EC, Sng BL: Investigating analgesic and psychological factors associated with risk of postpartum depression development: a case-control study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2016; 12: 1333–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu ZH, He ST, Deng CM, Ding T, Xu MJ, Wang L, Li XY, Wang DX: Neuraxial labour analgesia is associated with a reduced risk of maternal depression at 2 years after childbirth: A multicentre, prospective, longitudinal study. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2019; 36: 745–754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Riazanova OV, Alexandrovich YS, Ioscovich AM: The relationship between labor pain management, cortisol level and risk of postpartum depression development: a prospective nonrandomized observational monocentric trial. Rom J Anaesth Intensive Care 2018; 25: 123–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Orbach-Zinger S, Landau R, Harousch AB, Ovad O, Caspi L, Kornilov E, Ioscovich A, Bracco D, Davis A, Fireman S, Hoshen M, Eidelman LA: The Relationship Between Women's Intention to Request a Labor Epidural Analgesia, Actually Delivering With Labor Epidural Analgesia, and Postpartum Depression at 6 Weeks: A Prospective Observational Study. Anesth Analg 2018; 126: 1590–1597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nahirney M, Metcalfe A, Chaput KH: Administration of epidural labor analgesia is not associated with a decreased risk of postpartum depression in an urban Canadian population of mothers: a secondary analysis of prospective cohort data. Local Reg Anesth 2017; 10: 99–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ezeonu PO, Anozie OB, Onu FA, Esike CU, Mamah JE, Lawani LO, Onoh RC, Ndukwe EO, Ewah RL, Anozie RO: Perceptions and practice of epidural analgesia among women attending antenatal clinic in FETHA. Int J Womens Health 2017; 9: 905–911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eckerdal P, Kollia N, Karlsson L, Skoog-Svanberg A, Wikström AK, Högberg U, Skalkidou A: Epidural Analgesia During Childbirth and Postpartum Depressive Symptoms: A Population-Based Longitudinal Cohort Study. Anesth Analg 2020; 130: 615–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lim G, Levine MD, Mascha EJ, Wasan AD: Labor Pain, Analgesia, and Postpartum Depression: Are We Asking the Right Questions? Anesth Analg 2020; 130: 610–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lim G, Farrell LM, Facco FL, Gold MS, Wasan AD: Labor Analgesia as a Predictor for Reduced Postpartum Depression Scores: A Retrospective Observational Study. Anesth Analg 2018; 126: 1598–1605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eisenach JC, Pan PH, Smiley R, Lavand'homme P, Landau R, Houle TT: Severity of acute pain after childbirth, but not type of delivery, predicts persistent pain and postpartum depression. Pain 2008; 140: 87–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eisenach JC, Pan P, Smiley RM, Lavand'homme P, Landau R, Houle TT: Resolution of pain after childbirth. Anesthesiology 2013; 118: 143–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lim G, LaSorda KR, Farrell LM, McCarthy AM, Facco F, Wasan AD: Obstetric pain correlates with postpartum depression symptoms: a pilot prospective observational study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020; 20: 240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McClain L, Farrell L, LaSorda K, Pan LA, Peters D, Lim G: Genetic associations of perinatal pain and depression. Mol Pain 2019; 15: 1744806919882139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eberhard-Gran M, Garthus-Niegel S, Garthus-Niegel K, Eskild A: Postnatal care: a cross-cultural and historical perspective. Arch Womens Ment Health 2010; 13: 459–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.ACOG Committee Opinion No. 736: Optimizing Postpartum Care. Obstet Gynecol 2018; 131: e140–e150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.O'Connor E, Rossom RC, Henninger M, Groom HC, Burda BU: Primary Care Screening for and Treatment of Depression in Pregnant and Postpartum Women: Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Jama 2016; 315: 388–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.O'Hara MW, Pearlstein T, Stuart S, Long JD, Mills JA, Zlotnick C: A placebo controlled treatment trial of sertraline and interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression. J Affect Disord 2019; 245: 524–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miniati M, Callari A, Calugi S, Rucci P, Savino M, Mauri M, Dell'Osso L: Interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression: a systematic review. Arch Womens Ment Health 2014; 17: 257–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Werner EA, Gustafsson HC, Lee S, Feng T, Jiang N, Desai P, Monk C: PREPP: postpartum depression prevention through the mother-infant dyad. Arch Womens Ment Health 2016; 19: 229–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang R, Yang D, Lei B, Yan C, Tian Y, Huang X, Lei J: The short- and long-term effectiveness of mother-infant psychotherapy on postpartum depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2020; 260: 670–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Amodeo G, Laurenzi PF, Santucci A, Cuomo A, Bolognesi S, Goracci A, Rossi R, Beccarini Crescenzi B, Neal SM, Fagiolini A: Advances in treatment for postpartum major depressive disorder. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2020; 21: 1685–1698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Azhar Y, Din AU: Brexanolone, StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL), StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2021, StatPearls Publishing LLC., 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ahokas A, Kaukoranta J, Wahlbeck K, Aito M: Estrogen deficiency in severe postpartum depression: successful treatment with sublingual physiologic 17beta-estradiol: a preliminary study. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62: 332–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gregoire AJ, Kumar R, Everitt B, Henderson AF, Studd JW: Transdermal oestrogen for treatment of severe postnatal depression. Lancet 1996; 347: 930–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ma JH, Wang SY, Yu HY, Li DY, Luo SC, Zheng SS, Wan LF, Duan KM: Prophylactic use of ketamine reduces postpartum depression in Chinese women undergoing cesarean section(✰). Psychiatry Res 2019; 279: 252–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu Y, Li Y, Huang X, Chen D, She B, Ma D: Single bolus low-dose of ketamine does not prevent postpartum depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, prospective clinical trial. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2017; 295: 1167–1174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li W, Yin P, Lao L, Xu S: Effectiveness of Acupuncture Used for the Management of Postpartum Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biomed Res Int 2019; 2019: 6597503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ganho-Ávila A, Poleszczyk A, Mohamed MMA, Osório A: Efficacy of rTMS in decreasing postnatal depression symptoms: A systematic review. Psychiatry Res 2019; 279: 315–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miller BJ, Murray L, Beckmann MM, Kent T, Macfarlane B: Dietary supplements for preventing postnatal depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013: Cd009104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.John's Wort, Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed). Bethesda (MD), National Library of Medicine (US), 2006 [Google Scholar]