Abstract

Objective:

To examine childhood abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as predictors and moderators of binge-eating disorder (BED) treatment outcomes in a randomized controlled trial comparing Integrative Cognitive-Affective Therapy with cognitive-behavioral therapy administered using guided self-help.

Method:

In 112 adults with BED, childhood abuse was defined as any moderate/severe abuse as assessed by the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, lifetime PTSD was assessed via the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, and outcomes were assessed via the Eating Disorder Examination (EDE). Covariate-adjusted regression models predicting binge-eating frequency and EDE global scores at end of treatment and six-month follow-up were conducted.

Results:

Lifetime PTSD predicted greater binge-eating frequency at end of treatment (B=1.32, p=.009) and childhood abuse predicted greater binge-eating frequency at follow-up (B=1.00, p=.001). Lifetime PTSD moderated the association between childhood abuse and binge-eating frequency at follow-up (B=2.98, p=.009), such that childhood abuse predicted greater binge-eating frequency among participants with a history of PTSD (B=3.30, p=.001) but not among those without a PTSD history (B=0.31, p=.42). No associations with EDE global scores or interactions with treatment group were observed.

Conclusions:

Results suggest that a traumatic event history may hinder treatment success and that PTSD may be more influential than the trauma exposure itself.

Keywords: Eating Disorders, Binge-Eating Disorder, Psychotherapy, Childhood Abuse, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Introduction

Binge-eating disorder (BED) is characterized by recurrent episodes of binge eating without regular compensatory behaviors (e.g., vomiting, laxative abuse, excessive exercise), as well as significant distress regarding these episodes (American Psychiatric Association, 2013a). Globally, lifetime prevalence estimates of BED range from 0.6–5.8% among women and 0.3–2.0% among men (Galmiche, Déchelotte, Lambert, & Tavolacci, 2019), and BED is associated with substantial psychiatric and medical morbidity (Hudson, Hiripi, Pope, & Kessler, 2007; Mitchell, 2016; Olguin et al., 2017). While psychotherapies for BED have demonstrated efficacy, over half of patients with BED still report binge-eating episodes after treatment (Linardon, 2018), indicating a need to identify predictors of suboptimal treatment response and adapt treatment approaches accordingly.

Patients with a history of childhood trauma (e.g., abuse, neglect) represent an important subgroup that may be less likely to respond to treatment. A history of childhood trauma is common in patients with BED (Afifi et al., 2017; Caslini et al., 2016; Molendijk, Hoek, Brewerton, & Elzinga, 2017), with results from a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults suggesting that nearly three-quarters of individuals with BED had experienced maltreatment in childhood (Afifi et al., 2017). Across eating disorder diagnoses, evidence also suggests that patients with a history of trauma exhibit greater psychiatric comorbidity (Brewerton, 2007; Castellini et al., 2018; Wonderlich, Brewerton, Jocic, Dansky, & Abbott, 1997), are more likely to drop out of treatment (Castellini et al., 2018; Mahon, Bradley, Harvey, Winston, & Palmer, 2001; Mahon, Winston, Palmer, & Harvey, 2001; Rodríguez, Pérez, & García, 2005), and may be less likely to respond to treatment relative to those without a history of trauma (Anderson, LaPorte, Brandt, & Crawford, 1997; Castellini et al., 2018; Rodríguez et al., 2005; Strangio & Janiri, 2017).

To our knowledge, only one study to date has examined whether treatment outcomes in a BED sample differ according to trauma history (Serra et al., 2020). The perceived impact of trauma, but not the number of traumatic experiences, was found to predict poorer treatment response to group cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT; Serra et al., 2020), aligning with the idea put forth by Trottier and colleagues (2016) that posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may act as a more prominent maintenance factor for eating disorders than trauma exposure itself. More work is needed in this area to better understand the relative roles of trauma exposure and PTSD in treatment for BED, as it is important not only to identify which patients experience suboptimal outcomes from existing treatments so that more effective approaches can be developed for those patients, but also to identify which existing treatment might yield the most benefit for those patients.

While CBT (Fairburn, Marcus, & Wilson, 1993) is the most extensively studied psychotherapeutic treatment for BED and has been recommended as first-line treatment (Linardon, 2018; Vocks et al., 2010), Integrative Cognitive-Affective Therapy (Wonderlich, Peterson, & Smith, 2015) for BED (ICAT-BED) may confer unique benefits for patients with a history of childhood trauma. In contrast with CBT, which indirectly addresses emotions but focuses on cognitions and behaviors, ICAT-BED directly addresses the role of emotion. The ICAT model posits that interpersonal experiences (e.g., childhood trauma) may be important in predicting the onset of binge eating and that self-discrepancy (i.e., discordance between one’s perceptions of who they actually are and who they would ideally like to be or who they should or must be; Higgins, 1987), self-directed style (i.e., how one thinks, feels, and acts toward oneself; Benjamin, 1974), and emotion dysregulation (i.e., using maladaptive strategies to manage negative affect; Gratz & Roemer, 2004) may serve as key maintenance mechanisms (S. A. Wonderlich et al., 2008). Considering that individuals with a history of childhood trauma demonstrate increased levels of self-discrepancy (Brewin & Vallance, 1997), greater tendency toward negative self-directed styles such as self-blame (Swannell et al., 2012), and emotion dysregulation (Lavi, Katz, Ozer, & Gross, 2019), the key hypothesized maintenance mechanisms targeted by ICAT may be especially relevant for patients with a history of childhood trauma. Therefore, ICAT-BED may be particularly beneficial for patients who experienced childhood trauma.

Using data from a randomized controlled trial comparing ICAT-BED with CBT delivered using guided self-help (CBTgsh; Fairburn, 2013) for the treatment of BED (Peterson et al., 2020), the present study examined the roles of childhood abuse and PTSD history in relation to BED treatment response, as measured by objective binge-eating episode frequency and global eating disorder psychopathology. Specifically, the objectives of this study were (1) to examine childhood abuse, PTSD history, and the combination of childhood abuse and PTSD history as potential predictors of BED treatment outcomes, (2) to investigate childhood abuse, PTSD history, and the combination of childhood abuse and PTSD history as potential moderators of treatment outcomes in ICAT-BED versus CBTgsh treatment groups. We hypothesized that relative to patients without a history of childhood abuse, those with a history of childhood abuse would experience poorer treatment outcomes overall and respond better to ICAT-BED than CBTgsh. Similarly, we hypothesized that relative to patients without a history of PTSD, those with a history of PTSD would experience poorer treatment outcomes overall and respond better to ICAT-BED than CBTgsh. Additionally, we hypothesized that treatment outcomes associated with childhood abuse would be poorer among those with a history of PTSD than among those without a history of PTSD and that patients with a history of both childhood abuse and PTSD might experience greater relative benefit from ICAT-BED than CBTgsh compared to patients with a history of childhood trauma without PTSD.

Methods

Data for the present study come from baseline, end of treatment, and six-month follow up assessments in a 17-week, two-site randomized controlled trial comparing the efficacy of two psychotherapies for BED (Peterson et al., 2020). Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at each site, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Participants

Participants were recruited from two locations in the Midwestern region of the United States between 2014–2017 through eating disorder clinics, community advertisements, and social media postings. Participants aged 18–65 years and meeting full criteria for DSM-5 BED (American Psychiatric Association, 2013a) as determined by the 16th edition of the Eating Disorder Examination (EDE; Fairburn, Cooper, & O’Connor, 2008) were eligible. Exclusion criteria were: 1) inability to read English, 2) body mass index <21 kg/m2, 3) lifetime history of psychotic symptoms or bipolar disorder, 4) substance use disorder within six months of enrollment, 5) medical or psychiatric instability (e.g., acute suicidality), 6) purging behavior (i.e., self-induced vomiting, misuse of laxatives or diuretics) more than once per month for the previous three months, 7) current diagnosis of bulimia nervosa, 8) medical condition impacting eating or weight (e.g., thyroid condition), 9) history of gastric bypass surgery, 10) current pregnancy or lactation, 11) current participation in weight loss or ED treatment, 12) current use of medication impacting eating or weight (e.g., stimulants), or 13) psychotropic medication changes in the six weeks prior to enrollment. The sample included in the trial was comprised of 112 adults aged 18-64 years (M = 39.7, SD = 13.4). Most participants were cisgender women (n = 92; 82.1%), Caucasian (n = 102, 91.1%), and had earned a college degree (n = 77, 68.8%). Over a quarter of participants (n = 32, 28.6%) reported having participated in psychotherapy for any reason during the six months prior to beginning this study, and 7.1% (n = 8) indicated having participated in psychotherapy specifically focused on eating during the six months prior to beginning this study.

Protocol

As reported with the main treatment outcome results (Peterson et al., 2020), participants were randomized to either ICAT-BED (n = 56) or CBTgsh (n = 56). A total of 89 participants (79.4%) completed treatment, including 49 (87.5%) in ICAT-BED and 40 (71.4%) in CBTgsh. There were 21 sessions in ICAT-BED and 10 sessions in CBTgsh, with session frequency differing by treatment group to result in 17 weeks total of treatment duration for each group. All participants completed baseline assessments. Assessments were obtained at end-of-treatment for 84 (75.0%) participants and at six-month follow-up for 92 (82.1%) participants (participants were asked to complete a six-month follow-up assessment even if they did not complete treatment).

Interventions

Integrative Cognitive-Affective Therapy.

ICAT-BED is an intervention that was modified from ICAT for bulimia nervosa (i.e., by eliminating content related to purging and increasing behavioral opportunities for positive reinforcement, such as exercise; Wonderlich et al., 2015). ICAT-BED includes the following four phases emphasizing different goals: (1) treatment engagement, psychoeducation, and self-monitoring, (2) meal planning and adaptive coping methods, (3) precipitants of negative emotion including interpersonal difficulties, self-directed style, and self-discrepancy, and (4) relapse prevention and healthy lifestyle planning. In each phase, ICAT-BED focuses on awareness of emotions, development of skills, and understanding the function of binge-eating in the context of emotional states. Doctoral-level clinicians and graduate students who received one day-long didactic training and weekly group supervision served as therapists for ICAT-BED.

Guided self-help cognitive-behavioral therapy.

CBTgsh utilized the self-help book Overcoming Binge Eating (Fairburn, 2013) along with ten individual sessions with a non-specialist therapist. The role of the therapist was to explain the treatment rationale, assist in developing feasible treatment goals, and promote treatment adherence while allowing participants to progress through the self-help interventions at their own pace. The main goal in CBTgsh for BED is to establish a regular pattern of moderate eating using self-monitoring, self-control strategies, and problem-solving (Striegel-Moore et al., 2010). Psychoeducation and relapse prevention are also incorporated into CBTgsh, as they were in ICAT-BED. Master’s-level clinicians without specialized training in EDs who received a two-hour didactic training and weekly to bi-weekly group supervision served as therapists for CBTgsh.

Measures

Childhood abuse.

History of childhood abuse was assessed at baseline with the three abuse subscales from the 28-item version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ), a self-report measure of maltreatment experienced during childhood (Bernstein et al., 2003). Participants indicated the frequency of specific traumatic experiences on a Likert-type scale with response options ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The current study utilized the Emotional Abuse, Physical Abuse, and Sexual Abuse CTQ subscales, each comprising five items. Responses were summed to yield possible scores ranging from 5–25 for each subscale, with higher subscale scores indicating greater levels of abuse. CTQ scores have demonstrated good reliability and validity in previous studies (Bernstein et al., 2003; Liebschutz et al., 2018; Spinhoven et al., 2014). In the current sample, internal consistency was good for each of the CTQ abuse subscales (Emotional Abuse: α = .89; Physical Abuse: α = .80; Sexual Abuse: α = .90). Using the moderate/severe cut-off scores outlined in the CTQ manual for Emotional Abuse (≥ 13), Physical Abuse (≥ 10), and Sexual Abuse (≥ 8; Bernstein & Fink, 1998), a dichotomous variable was created representing moderate or severe abuse of any type during childhood versus no/low abuse during childhood.

Posttraumatic stress disorder.

Lifetime PTSD diagnosis was assessed at baseline with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-IV; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002), administered by trained master’s-level assessment interviewers. The SCID has demonstrated good reliability and validity in prior research (Lobbestael, Leurgans, & Arntz, 2011; Ventura, Liberman, Green, Shaner, & Mintz, 1998).

Treatment outcomes.

The 16th edition of the EDE (Fairburn et al., 2008) was used to assess past 28-day frequency of objective binge-eating episodes and global eating disorder psychopathology at baseline, end of treatment, and six-month follow-up. Global eating disorder psychopathology was calculated as the average of the following four subscales: Restraint, Eating Concern, Shape Concern, and Weight Concern. Higher global scores on the EDE indicate more severe eating disorder psychopathology. The EDE has demonstrated good reliability and validity in previous studies (Berg, Peterson, Frazier, & Crow, 2012). Clinical interviewers received didactic training, were supervised by a licensed psychologist, and met regularly for consensus discussions regarding scoring. Inter-rater reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient) based on a subsample of 20% of study participants selected at random (n = 22) was .94 for the global score, and internal consistency of the global scale was good in the present sample (α = .80).

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted with SPSS version 25. Consistent with the method used in the main treatment outcome report (Peterson et al., 2020), missing data were multiply imputed using the fully conditional Markov chain Monte Carlo method, with results based upon pooled estimates from 20 imputed datasets. While results of Little’s missing completely at random (MCAR) test indicated that data were consistent with a MCAR pattern of missingness (χ2 = 33.11, df = 29, p = .27), multiple imputation was used to adhere to the intention-to-treat principle. Descriptive statistics were calculated, and regression models predicting objective binge-eating episode frequency and EDE global scores at end of treatment and six-month follow-up were conducted. Negative binomial regression models were used to predict objective binge-eating episode frequency, and linear regression models were used to predict EDE global scores. Three sets of predictor models were conducted, examining the following as predictors of each treatment outcome at end of treatment and six-month follow-up in separate models: (1) childhood abuse, (2) PTSD, and (3) an interaction between childhood abuse and PTSD (including the respective lower-order terms in the models). All models were adjusted for baseline level of treatment outcome, participant age, gender, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, study site, and treatment group. Treatment moderator models were then conducted by adding a treatment group x predictor interaction term (e.g., treatment group x childhood abuse) to each of the predictor models. Significance thresholds were corrected for multiple comparisons across regression results using False Discovery Rate (FDR) procedures (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995) with an FDR of Q = .10.

Results

Descriptives

Just over one-third of the sample (34.4%) had experienced moderate or severe abuse of any type during childhood, and 16.6% of the sample met criteria for a lifetime PTSD diagnosis. As indicated in Table 1, participants who had experienced any moderate or severe abuse during childhood were more likely than those who had not to meet criteria for a lifetime PTSD diagnosis (28.5% versus 10.3%). Compared with participants classified as having experienced no or low levels of childhood abuse, those classified as having experienced any moderate or severe childhood abuse demonstrated higher scores on each of the three CTQ abuse subscales but did not exhibit differences in objective binge-eating episode frequency or global eating disorder psychopathology at baseline.

Table 1.

Baseline descriptives, overall and by childhood abuse history (N = 112)

| Full Sample | No/Low Childhood Abuse |

Moderate/Severe Childhood Abuse |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifetime PTSD, % | 16.6 | 10.3 | 28.5 | .02 |

| Childhood abuse, M (SD) | ||||

| Emotional abuse CTQ score | 9.82 (4.81) | 7.05 (2.07) | 15.08 (4.10) | < .001 |

| Physical abuse CTQ score | 6.37 (2.55) | 5.56 (0.92) | 7.92 (3.72) | < .001 |

| Sexual abuse CTQ score | 6.16 (2.58) | 5.22 (0.61) | 7.96 (3.72) | < .001 |

| ED severity, M (SD) | ||||

| Objective binge-eating episode frequency | 15.75 (10.73) | 15.92 (10.34) | 15.42 (11.56) | .81 |

| Global ED psychopathology | 2.68 (0.84) | 2.68 (0.81) | 2.69 (0.90) | .96 |

Note. PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder; CTQ = Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; M = mean; SD = standard deviation; ED = eating disorder. Moderate/severe childhood abuse was reported by 34.4% of the sample. Possible range for each childhood abuse variable is 5–25; possible range for global ED psychopathology is 0–6.

Predictor Models

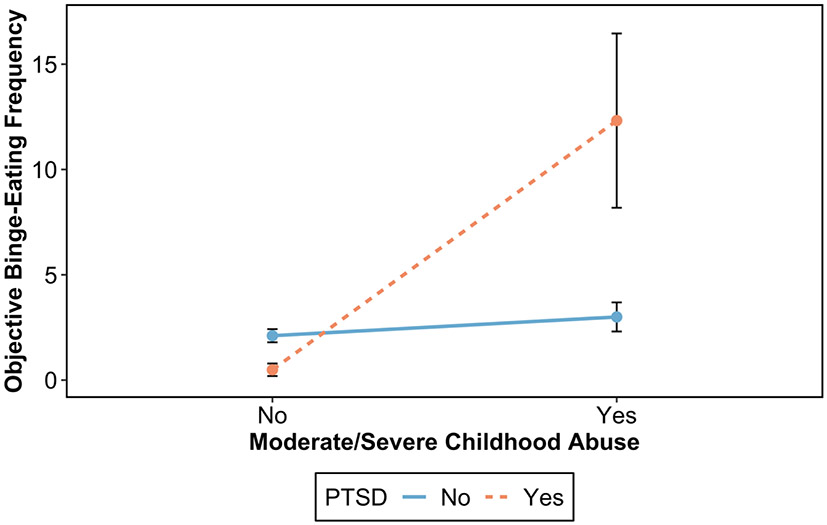

Adjusted estimates of childhood abuse, PTSD history, and the combination of childhood abuse and PTSD history predicting treatment outcomes are reported in Table 2, and full multivariable regression results with estimates for each covariate are reported in Tables S1-S3 (available online). After adjusting for baseline level of objective binge-eating episode frequency, participant age, gender, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, study site and treatment group, PTSD predicted greater objective binge-eating episode frequency at end of treatment (B = 1.32, p = .009) and moderate/severe childhood abuse predicted greater objective binge-eating episode frequency at six-month follow-up (B = 1.00, p = .001). As demonstrated in Figure 1, lifetime PTSD moderated the association between moderate/severe childhood abuse and objective binge-eating episode frequency at six-month follow-up (B = 2.98, p = .009), such that moderate/severe childhood abuse predicted greater objective binge-eating episode frequency among participants with lifetime PTSD (B = 3.30, p = .001) but not among those without lifetime PTSD (B = 0.31, p = .42). Global eating disorder psychopathology outcomes were not predicted by childhood abuse, PTSD, or their interaction.

Table 2.

Examining moderate/severe childhood abuse and lifetime post-traumatic stress disorder as predictors and moderators of treatment outcomes (N = 112)

| Objective Binge-Eating Episode Frequency | Global Eating Disorder Psychopathology | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| End of Treatment | Six-Month Follow-Up | End of Treatment | Six-Month Follow-Up | |

| B (95% CI) | ||||

| Predictor models | ||||

| Childhood abuse | 0.66 (−0.03, 1.36) | 1.00 (0.41, 1.58)** | 0.17 (−0.33, 0.67) | 0.37 (−0.17, 0.91) |

| PTSD | 1.32 (0.35, 2.30)** | 1.07 (0.18, 1.96)* | 0.24 (−0.43, 0.91) | 0.24 (−0.35, 0.82) |

| Childhood abuse x PTSD | 1.58 (−0.58, 3.74) | 2.98 (0.76, 5.20)** | −0.14 (−1.45, 1.17) | 0.59 (−0.65, 1.83) |

| Treatment moderator models | ||||

| Childhood abuse x Treatment group | −0.96 (−2.46, 0.54) | −0.01 (−1.17, 1.14) | −0.18 (−1.09, 0.73) | 0.32 (−0.54, 1.18) |

| PTSD x Treatment group | −1.87 (−4.00, 0.25) | −0.54 (−2.01, 0.93) | 0.39 (−0.67, 1.45) | 0.58 (−0.52, 1.69) |

| Childhood abuse x PTSD x Treatment group | 1.41 (−14.68, 17.49) | 2.43 (−1.60, 6.46) | 1.24 (−3.08, 5.55) | 2.30 (−0.26, 4.87) |

Note. CI = confidence interval; PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder. Treatment group represents ICAT-BED versus CBTgsh. Separate models were conducted for each predictor and moderator term. All models were adjusted for baseline level of treatment outcome, participant age, gender, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, study site, and treatment group.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001; bold indicates significance after applying Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate procedures.

Figure 1.

Predicted objective binge-eating episode frequency at six-month follow-up by childhood abuse history and lifetime post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), adjusted for baseline binge-eating episode frequency, participant demographics, study site, and treatment group. Error bars represent standard errors.

Treatment Moderator Models

Adjusted estimates of childhood abuse, PTSD history, and the combination of childhood abuse and PTSD history moderating treatment outcomes are reported in Table 2, and full multivariable regression results with estimates for each covariate are reported in Tables S4-S6 (available online). No evidence of moderation by treatment group was found for childhood abuse, PTSD, or their interaction in relation to either objective binge-eating episode frequency or global eating disorder psychopathology.

Discussion

The present study examined the roles of childhood abuse and PTSD in relation to BED treatment outcomes in a randomized controlled trial. Results partially supported our hypotheses, in that histories of childhood abuse and PTSD each predicted poorer binge-eating treatment outcome and the association between childhood abuse history and binge-eating treatment outcome differed by PTSD history, such that the association was only observed among participants with a history of PTSD. However, our hypothesis that participants with a trauma history would respond better to ICAT-BED than CBTgsh was not supported; participants with trauma histories responded similarly to ICAT-BED and CBTgsh. Overall, results suggest that a traumatic event history may hinder BED treatment success and that PTSD may be more influential than the trauma exposure itself. These findings suggest a potential need to develop more effective BED treatment approaches or incorporate adjunct trauma-focused treatments — such as eye-movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), cognitive processing therapy (CPT), or prolonged exposure (Brewerton, 2019; Brewerton, Trottier, Trim, Meyers, & Wonderlich, 2020) — for patients with trauma histories and/or PTSD.

Our results are generally consistent with evidence that a history of trauma predicts poorer treatment response across eating disorder diagnoses (i.e., including anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa; Anderson et al., 1997; Castellini et al., 2018; Rodríguez et al., 2005; Strangio & Janiri, 2017), although this was observed only for objective binge-eating episode frequency in our study, and not for global eating disorder psychopathology. Given that dissociation may occur as a way of coping with trauma (Schimmenti & Caretti, 2016), the observed relevance of a trauma history specifically for objective binge-eating episode frequency, but not global eating disorder psychopathology, may be explained, in part, by the dissociative function that binge eating, in particular, appears to serve (La Mela, Maglietta, Castellini, Amoroso, & Lucarelli, 2010; Mason et al., 2017; Palmisano et al., 2018). With regard to BED specifically, our findings build upon prior work conducted by Serra and colleagues which identified perceived traumatic impact, but not the number of traumatic experiences, as a predictor of poorer response at the end of treatment for BED (Serra et al., 2020). The results of our study are consistent with the findings of Serra and colleagues, as we found that PTSD history, but not childhood abuse history, to predict greater objective binge-eating episode frequency at the end of treatment. In support of the notion that dissociation may play a role in the relationship between trauma and binge eating, Serra and colleagues found dissociative symptoms to partially mediate the association between perceived traumatic impact and BED treatment response (Serra et al., 2020). Extending beyond the study by Serra and colleagues, we were able to additionally examine treatment outcomes at follow-up and found evidence to suggest that the predictive value of trauma endures beyond the end of treatment. More specifically, we found that childhood abuse history predicted greater binge-eating episode frequency at six-month follow-up, but only among those who also had a history of PTSD. Of note, trauma exposure assessment in the study by Serra and colleagues was not limited to childhood trauma as it was in the present study, but rather included trauma during adulthood as well. As childhood is a sensitive period during which trauma appears to be particularly harmful (Dunn, Nishimi, Gomez, Powers, & Bradley, 2018; Dunn, Nishimi, Powers, & Bradley, 2017), trauma may differentially impact treatment outcomes depending on the timing of the trauma.

Our finding that the association between childhood abuse history and treatment outcome was observed only among those with a history of PTSD provides support for the theory that PTSD may play a more influential maintenance role in eating disorders than the trauma exposure itself (Trottier et al., 2016). Only a subset of individuals who have been exposed to trauma end up developing PTSD (Breslau, 2009), but those who do may experience intrusive and distressing memories, thoughts, and feelings related to the trauma they sustained (American Psychiatric Association, 2013b). It has been proposed that binge eating and other eating disorder behaviors may serve an avoidance function in PTSD, such that they may provide a temporary escape from the intrusive and distressing memories, thoughts, and feelings (Brewerton, 2007, 2011; Trottier et al., 2016). Any level of successful avoidance achieved may reinforce, and therefore maintain, these behaviors (Trottier et al., 2016). If PTSD is indeed an important maintenance factor for binge eating, as the results from the present study suggest, then addressing PTSD may be crucial for improving BED treatment efficacy.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine the relationship between trauma and BED treatment outcomes in a randomized controlled trial. We hypothesized that patients with histories of childhood abuse or PTSD would respond better to ICAT-BED than CBTgsh because ICAT-BED targets self-discrepancy, self-directed styles, and emotion dysregulation, each of which may be particularly relevant for those with a trauma history (Brewin & Vallance, 1997; Lavi et al., 2019; Swannell et al., 2012). However, we found that patients with trauma histories responded similarly to ICAT-BED and CBTgsh. A possible explanation for the lack of differences by treatment group is that although ICAT-BED aims to influence certain constructs that may be valuable targets for patients with trauma histories — namely self-discrepancy, self-directed style, and emotion dysregulation — observed improvements in these targets over the course of treatment were similar across the ICAT-BED and CBTgsh treatment groups (Peterson et al., 2020). Moreover, ICAT-BED and its underlying theoretical model were not developed to explicitly address trauma (Peterson et al., 2020; Wonderlich et al., 2008). Eating disorder treatment approaches explicitly designed to address trauma-related symptoms are therefore warranted. One such treatment, an integrated CBT intervention for co-occurring eating disorders and PTSD, has been developed and demonstrated preliminary success in an initial uncontrolled study (Trottier, Monson, Wonderlich, & Olmsted, 2017). A more rigorous efficacy study of this intervention is in progress, which will provide important information on the value of an eating disorder treatment approach explicitly designed to address trauma-related symptoms.

Strengths of this study include its randomized, controlled study design, the rigorous assessments of treatment outcomes through follow-up, and the use of two treatment sites, which might improve generalizability of our findings. However, this study also had important limitations. Childhood abuse was assessed retrospectively, potentially resulting in some misclassification of trauma exposure history, although the CTQ has previously demonstrated reasonable correlations with prospectively reported childhood trauma (Liebschutz et al., 2018). Another limitation is that PTSD was assessed with the SCID rather than a continuous measure of PTSD symptoms, thus reducing statistical power and disregarding subthreshold levels of PTSD, which may be of relevance. Further, because we examined lifetime PTSD rather than current PTSD, it is not clear to what extent current PTSD symptoms may have played a role in symptom maintenance. Additionally, there is a possibility that exclusion criteria for the present study could have inadvertently resulted in exclusion of some potential participants with a history of PTSD. However, the prevalence observed in our sample is higher than the prevalence observed in treatment-seeking patients with BED in a study using national registry data (Welch et al., 2016), suggesting that the exclusion criteria in our study may have not substantially impacted the proportion of participants with PTSD in our sample. The sample composition represents another limitation of the present study, as, consistent with many other BED treatment samples (e.g., Karam, Eichen, Fitzsimmons-Craft, & Wilfley, 2020; Serra et al., 2020), participants were primarily Caucasian, female, and well educated, thereby limiting generalizability to other samples. Despite these limitations, however, this study provides valuable information on the role of trauma in relation to BED treatment outcomes.

In conclusion, results of the present study indicate that patients with trauma histories benefit less from existing psychotherapy approaches for BED than those without trauma histories, as well as suggest that PTSD may be more influential than the trauma exposure itself. These results emphasize the importance of screening for trauma — particularly PTSD symptoms — in patients with eating disorders and indicate a need for eating disorder treatments that explicitly address trauma-related symptoms.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Lifetime posttraumatic stress disorder predicted more frequent binge eating at end of treatment

History of childhood abuse predicted more frequent binge eating at follow-up, but only among those with lifetime posttraumatic stress disorder

Participants with trauma histories responded similarly to Integrative Cognitive-Affective Therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy administered using guided self-help

Acknowledgements:

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R34MH098995, R34MH099040, P30DK60456, T32MH082761) and the Neuropsychiatric Research Institute.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Afifi TO, Sareen J, Fortier J, Taillieu T, Turner S, Cheung K, & Henriksen CA (2017). Child maltreatment and eating disorders among men and women in adulthood: Results from a nationally representative United States sample. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 50(11), 1281–1296. 10.1002/eat.22783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013a). Feeding and Eating Disorders. In Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.dsm10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013b). Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders. In Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KP, LaPorte DJ, Brandt H, & Crawford S (1997). Sexual abuse and bulimia: Response to inpatient treatment and preliminary outcome. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 31(6), 621–633. 10.1016/S0022-3956(97)00026-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin LS (1974). Structural analysis of social behavior. Psychological Review, 81, 392–425. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, & Hochberg Y (1995). Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B (Methodological), 57(1), 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Berg KC, Peterson CB, Frazier P, & Crow SJ (2012). Psychometric evaluation of the Eating Disorder Examination and Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire: a systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 45(3), 428–438. 10.1002/eat.20931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, & Fink L (1998). Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: A Retrospective Self-Report. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, … Zule W (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse and Neglect, 27(2), 169–190. 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N (2009). The epidemiology of trauma, PTSD, and other posttrauma disorders. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 10(3), 198–210. 10.1177/1524838009334448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewerton TD (2007). Eating disorders, trauma, and comorbidity: Focus on PTSD. Eating Disorders, 15(4), 285–304. 10.1080/10640260701454311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewerton TD (2011). Posttraumatic stress disorder and disordered eating: Food addiction as self-medication. Journal of Women’s Health, 20(8), 1133–1134. 10.1089/jwh.2011.3050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewerton TD (2019). An overview of rrauma-informed care and practice for eating disorders. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment and Trauma, 28(4), 445–462. 10.1080/10926771.2018.1532940 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brewerton TD, Trottier K, Trim J, Meyers T, & Wonderlich S (2020). Integrating Evidence-Based Treatments for Eating Disorder Patients with Comorbid PTSD and Trauma-Related Disorders. In Tortolani CC, Goldschmidt AB, & Le Grange D (Eds.), Adapting Evidence-Based Eating Disorder Treatments for Novel Populations and Settings: A Practical Guide (pp. 216–237). New York, NY: Routledge. 10.4324/9780429031106-10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, & Vallance H (1997). Self-discrepancies in young adults and childhood violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 12(4), 600–606. 10.1177/088626097012004008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caslini M, Bartoli F, Crocamo C, Dakanalis A, Clerici M, & Carrà G (2016). Disentangling the association between child abuse and eating disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosomatic Medicine, 78(1), 79–90. 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellini G, Lelli L, Cassioli E, Ciampi E, Zamponi F, Campone B, … Ricca V (2018). Different outcomes, psychopathological features, and comorbidities in patients with eating disorders reporting childhood abuse: A 3-year follow-up study. European Eating Disorders Review, 26(3), 217–229. 10.1002/erv.2586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn EC, Nishimi K, Gomez SH, Powers A, & Bradley B (2018). Developmental timing of trauma exposure and emotion dysregulation in adulthood: Are there sensitive periods when trauma is most harmful? Journal of Affective Disorders, 227, 869–877. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.10.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn EC, Nishimi K, Powers A, & Bradley B (2017). Is developmental timing of trauma exposure associated with depressive and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in adulthood? Journal of Psychiatric Research, 84, 119–127. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG (2013). Overcoming Binge Eating. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, & O’Connor ME (2008). Eating Disorder Examination (Edition 16.0D). In Fairburn Christopher G. (Ed.), Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders (pp. 265–308). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Marcus MD, & Wilson GT (1993). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for binge eating and bulimia nervosa: A comprehensive treatment manual. In Fairburn CG & Wilson GT (Eds.), Binge Eating: Nature, Assessment, and Treatment (pp. 361–404). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, & Williams JB (2002). Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I disorders, research version, non-patient edition. New York, NY: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Galmiche M, Déchelotte P, Lambert G, & Tavolacci MP (2019). Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000–2018 period: A systematic literature review. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 109(5), 1402–1413. 10.1093/ajcn/nqy342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, & Roemer L (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41–54. 10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ET (1987). Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychological Review, 94(3), 319–340. 10.1037/0033-295X.94.3.319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, & Kessler RC (2007). The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological Psychiatry, 61(3), 348–358. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karam AM, Eichen DM, Fitzsimmons-Craft EE, & Wilfley DE (2020). An examination of the interpersonal model of binge eating over the course of treatment. European Eating Disorders Review, 28(1), 66–78. 10.1002/erv.2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Mela C, Maglietta M, Castellini G, Amoroso L, & Lucarelli S (2010). Dissociation in eating disorders: relationship between dissociative experiences and binge-eating episodes. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 51(4), 393–400. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2009.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavi I, Katz LF, Ozer EJ, & Gross JJ (2019). Emotion reactivity and regulation in maltreated children: A meta-analysis. Child Development, 90(5), 1503–1524. 10.1111/cdev.13272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebschutz JM, Buchanan-Howland K, Chen CA, Frank DA, Richardson MA, Heeren TC, … Rose-Jacobs R (2018). Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) correlations with prospective violence assessment in a longitudinal cohort. Psychological Assessment, 30(6), 841–845. 10.1037/pas0000549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linardon J (2018). Rates of abstinence following psychological or behavioral treatments for binge-eating disorder: Meta-analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 51(8), 785–797. 10.1002/eat.22897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobbestael J, Leurgans M, & Arntz A (2011). Inter-rater reliability of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID I) and Axis II Disorders (SCID II). Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 18(1), 75–79. 10.1002/cpp.693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahon J, Bradley SN, Harvey PK, Winston AP, & Palmer RL (2001). Childhood trauma has dose-effect relationship with dropping out from psychotherapeutic treatment for bulimia nervosa: A replication. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 30(2), 138–148. 10.1002/eat.1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahon J, Winston AP, Palmer RL, & Harvey PK (2001). Do broken relationships in childhood relate to bulimic women breaking off psychotherapy in adulthood? International Journal of Eating Disorders, 29(2), 139–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason TB, Lavender JM, Wonderlich SA, Steiger H, Cao L, Engel SG, … Crosby RD (2017). Comfortably numb: The role of momentary dissociation in the experience of negative affect around binge eating. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 205(5), 335–339. 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JE (2016). Medical comorbidity and medical complications associated with binge-eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 49(3), 319–323. 10.1002/eat.22452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molendijk ML, Hoek HW, Brewerton TD, & Elzinga BM (2017). Childhood maltreatment and eating disorder pathology: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 47(8), 1402–1416. 10.1017/S0033291716003561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olguin P, Fuentes M, Gabler G, Guerdjikova AI, Keck PE, & McElroy SL (2017). Medical comorbidity of binge eating disorder. Eating and Weight Disorders, 22(1), 13–26. 10.1007/s40519-016-0313-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmisano GL, Innamorati M, Susca G, Traetta D, Sarracino D, & Vanderlinden J (2018). Childhood traumatic experiences and dissociative phenomena in eating disorders: Level and association with the severity of binge eating symptoms. Journal of Trauma and Dissociation, 19(1), 88–107. 10.1080/15299732.2017.1304490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson CB, Engel SG, Crosby RD, Strauman T, Smith TL, Klein M, … Wonderlich SA (2020). Comparing integrative cognitive-affective therapy and guided self-help cognitive-behavioral therapy to treat binge-eating disorder using standard and naturalistic momentary outcome measures: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(9), 1418–1427. 10.1002/eat.23324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez M, Pérez V, & García Y (2005). Impact of traumatic experiences and violent acts upon response to treatment of a sample of Colombian women with eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 37(4), 299–306. 10.1002/eat.20091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimmenti A, & Caretti V (2016). Linking the overwhelming with the unbearable: Developmental trauma, dissociation, and the disconnected self. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 33(1), 106–128. 10.1037/a0038019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Serra R, Kiekens G, Tarsitani L, Vrieze E, Bruffaerts R, Loriedo C, … Vanderlinden J (2020). The effect of trauma and dissociation on the outcome of cognitive behavioural therapy for binge eating disorder: A 6-month prospective study. European Eating Disorders Review, 28(3), 309–317. 10.1002/erv.2722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinhoven P, Penninx BW, Hickendorff M, van Hemert AM, Bernstein DP, & Elzinga BM (2014). Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: factor structure, measurement invariance, and validity across emotional disorders. Psychological Assessment, 26(3), 717–729. 10.1037/pas0000002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strangio AM, & Janiri L (2017). The effect of abuse history on adolescent patients with feeding and eating disorders treated through psychodynamic therapy: comorbidities and outcome. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 8(March). 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striegel-Moore RH, Wilson GT, DeBar L, Perrin N, Lynch F, Rosselli F, & Kraemer HC (2010). Cognitive behavioral guided self-help for the treatment of recurrent binge eating. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(3), 312–321. 10.1037/a0018915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swannell S, Martin G, Page A, Hasking P, Hazell P, Taylor A, & Protani M (2012). Child maltreatment, subsequent non-suicidal self-injury and the mediating roles of dissociation, alexithymia and self-blame. Child Abuse and Neglect, 36(7–8), 572–584. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trottier K, Monson CM, Wonderlich SA, & Olmsted MP (2017). Initial findings from Project Recover: Overcoming co-occurring eating disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder through integrated treatment. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 30(2), 173–177. 10.1002/jts.22176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trottier K, Wonderlich SA, Monson CM, Crosby RD, & Olmsted MP (2016). Investigating posttraumatic stress disorder as a psychological maintaining factor of eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 49(5), 455–457. 10.1002/eat.22516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura J, Liberman RP, Green MF, Shaner A, & Mintz J (1998). Training and quality assurance with the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I/P). Psychiatry Research, 79(2), 163–173. 10.1016/S0165-1781(98)00038-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vocks S, Tuschen-Caffier B, Pietrowsky R, Rustenbach SJ, Kersting A, & Herpertz S (2010). Meta-analysis of the effectiveness of psychological and pharmacological treatments for binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 43(3), 205–217. 10.1002/eat.20696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch E, Jangmo A, Thornton LM, Norring C, von Hausswolff-Juhlin Y, Herman BK, … Bulik CM (2016). Treatment-seeking patients with binge-eating disorder in the Swedish national registers: Clinical course and psychiatric comorbidity. BMC Psychiatry, 16(1), 163. 10.1186/s12888-016-0840-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonderlich SA, Engel SG, Peterson CB, Robinson MD, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, … Simonich HK (2008). Examining the conceptual model of integrative cognitive-affective therapy for BN: Two assessment studies. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 41(8), 748–754. 10.1002/eat.20551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonderlich SA, Peterson CB, & Smith TL (2015). Integrative cognitive-affective therapy for bulimia nervosa: A treatment manual. New York, NY: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Wonderlich Stephen A., Brewerton TD, Jocic Z, Dansky BS, & Abbott DW (1997). Relationship of childhood sexual abuse and eating disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(8), 1107–1115. 10.1097/00004583-199708000-00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.