Abstract

Introduction:

Microbiome differences have been found in adults who smoke cigarettes compared to non-smoking adults, but the impact of thirdhand smoke (THS; postcombustion tobacco residue) on hospitalized infants’ rapidly developing gut microbiomes is unexplored. Our aim was to explore gut microbiome differences in infants admitted to a neonatal ICU (NICU) with varying THS-related exposure.

Methods:

Forty-three mother-infant dyads (household members] smoke cigarettes, n=32; no household smoking, n=11) consented to a carbon monoxide-breath sample, bedside furniture nicotine wipes, infant-urine samples (for cotinine [nicotine’s primary metabolite] assays), and stool collection (for 16S rRNA V4 gene sequencing). Negative binomial regression modelled relative abundances of 8 bacterial genera with THS exposure-related variables (i.e., household cigarette use, surface nicotine, and infant urine cotinine), controlling for gestational age, postnatal age, antibiotic use, and breastmilk feeding. Microbiome-diversity outcomes were modelled similarly. Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP) ≥75.0% were considered meaningful.

Results:

A majority of infants (78%) were born pre-term. Infants from non-smoking homes and/or with lower NICU-furniture surface nicotine had greater microbiome alpha-diversity compared to infants from smoking households (PP≥75.0%). Associations (with PP≥75.0%) of selected bacterial genera with urine cotinine, surface nicotine, and/or household cigarette use were evidenced for 7 (of 8) modelled genera. For example, lower Bifidobacterium relative abundance associated with greater furniture nicotine (IRR<0.01 [<0.01, 64.02]; PP=87.1%), urine cotinine (IRR=0.08 [<0.01,2.84]; PP=86.9%), and household smoking (IRR<0.01 [<0.01, 7.38]; PP=96.0%; FDR p<0.05).

Conclusions:

THS-related exposure was associated with microbiome differences in NICU-admitted infants. Additional research on effects of tobacco-related exposures on healthy infant gut-microbiome development is warranted.

Keywords: thirdhand smoke, THS, gut microbiome, neonatal ICU, NICU, breastmilk, tobacco toxicants, tobacco carcinogens

1. Introduction

The gut microbiome consists of all the bacteria, fungi, and viruses inside the gastrointestinal tract, which begins development at birth and undergoes rapid changes during infancy (i.e., the first 12 months of age). A diverse and well-regulated gut microbiome modulates immune responses and is important for healthy development.1 For example, recent work found that 14 taxa located in the intestinal (duodenal) microbiota may contribute to pro-inflammatory processes that inhibit growth in undernourished children.2

Many environmental factors affect the microbiome’s developmental course. It is well-established that infant delivery route (i.e., vaginal or caesarean section) has an impact on infant microbiome development,3 with caesarean-delivered infants initially having microbiomes containing microbes found in the environment.4,5 During early postnatal development in the hospital, environmental factors immediately begin to influence gut-microbiome colonization. For example, feeding decisions (e.g., breastmilk vs. formula) shape microbiome development. Infants born preterm (i.e., <37 weeks gestational age) or with complications may spend weeks or months in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and often receive one or more courses of antibiotics,6 which influences the gut microbiota of preterm infants.7-9 The NICU environment also influences infant microbiome colonization and development1,10 (e.g., the NICU harbors a high diversity of human-associated bacteria on hospital surfaces)11.

Recent work has documented thirdhand smoke (THS) contamination (e.g., residual surface nicotine) on NICU furniture, which is transported and deposited by medical staff12 and non-staff visitors, and demonstrated infant exposure to THS while infants are hospitalized in the NICU.13,14 This raises the possibility that THS may affect infants’ early postnatal microbiome development, as nicotine has antibacterial and antifungal properties,15 and research on the associations between tobacco smoke exposure and impacts on children’s microbial flora are growing.16 Indeed, THS exposure has recently been linked to microbiome changes in the built (indoor home) environment (e.g., floor, table) and human microbiome (e.g., nose, ear) for children under 5 years of age.17 Specifically, Kelley et al.17 reported differences in 10 separate taxa present in children’s microbiome (e.g., Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Veillonella), across those exposed to THS and those not exposed. A study with an adult population found that individuals who smoked cigarettes had significantly different alpha (α) diversity and taxonomic differences (i.e., higher Prevotella and lower Bacteroides relative abundance) in their gut microbiomes, compared to adults who vape (electronic nicotine) and adults who do not smoke. Individuals who vape were not different from controls who did not smoke or vape.18

Our primary aim was to explore THS-exposure associations with gut-microbiome diversity and taxa in a sample of infants admitted to a NICU. Specifically, we assessed infant THS-related exposure via mothers’ self-reported household cigarette smoking (i.e., ≥1 individual in the home smokes), bedside NICU-furniture surface nicotine, and urine cotinine (i.e., the primary metabolite of nicotine). Post-hoc hypotheses were that infants with less THS-related exposure would have higher levels of α-diversity and relative abundances of several taxa present in the gut would vary based on THS-related exposure. Secondary and exploratory aims were to demonstrate feasibility of stool and breastmilk collection, with infants and their mothers, respectively, and quantify tobacco contaminants in breastmilk.19 For example, the tobacco-specific, N-nitrosamines, 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) and its metabolite, 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol (NNAL), are carcinogenic,20 and the presence of each has been reported in the breastmilk of lactating rats,21 but not yet reported in human milk, which we examined.

2. Methods

This exploratory protocol was added to an ongoing study of THS exposure in a NICU and full details on the parent study are published.12,14. Briefly, the current study recruited a cross-sectional sample of 43 mother-infant dyads from a metropolitan NICU. All mothers with an infant admitted to the NICU were eligible when infants reached 5 (postnatal) days of age. Data collection began in March, 2018 and concluded in October, 2018. Research staff screened bedside NICU visitors several times/week. By parent study design, participants from homes with one or more individual who smokes cigarettes (“smoking households”; n=32) were over recruited (approximately 3:1) compared to homes were zero individuals who smoked cigarettes live in the home (“non-smoking households”; n=11;).14 Participants (N=43) consented to an interview (assessing infant feeding, visitation, and holding, and household cigarette/tobacco/nicotine use and exposure), a carbon monoxide (CO)-breath sample, one bedside (NICU) furniture surface-nicotine wipe, one infant-urine collection (for cotinine [primary metabolite of nicotine] assays), and one stool collection (for 16S rRNA V4 gene sequencing18). Mothers currently breastfeeding/pumping also consented to provide a breastmilk sample. All interviews and infant sample collection occurred in the NICU while infants were hospitalized. All mothers were discharged from the hospital at the time of study participation. Some infants were discharged prior to stool (n=3) or urine collection (n=1), and 23 mothers did not provide a breastmilk sample (most often due to no longer breastfeeding or pumping). Individuals unable to complete assessments in English were excluded. All participants gave consent and received $10.

We chose to explore the gut microbiome for two primary reasons: bacterial abundance and non-invasive-collection methods. Following participant consent, nurses or research staff harvested stool from soiled diapers with a sterile plastic spoon into a sterile collection pot during the next diaper change. Samples were labelled and stored in a −30-degree (F) freezer until study completion when samples were transported in a cooler to an adjacent building for sequencing..

Infant stool was analyzed by sequencing 0.25 grams of stool using 16S rRNA gene sequencing of the variable 4 (V4) region.22,23 Methods for DNA extraction, sequencing, and bioinformatics were as described previously;24 see Supplement 1 for additional details. All samples were rarefied to 5803 reads. Bedside NICU furniture (surface) nicotine was measured by wetting a screened cotton pad with an ascorbic-acid solution,13,14,25-28 was corrected for ambient nicotine in the wipe without wiping (by subtracting field blank nicotine levels),14,28 was quantified per published protocols (limit-of-quantification [LOQ]=0.3 ng/wipe),29 and was reported in micrograms per meter squared (μg/m2). To measure cotinine, cotton pads were placed in infants’ diapers and expressed when saturated. Published methods were employed to quantify cotinine (LOQ=0.05 nanogram [ng]/mL).30 Participants were given written instructions on breastmilk collection (see Supplement 1). Cotinine in breastmilk was analyzed using a modified version of a previously developed LC-MS/MS method for urinary cotinine analysis;31 see Supplement 1 for additional details.The LOQ was 0.026 ng/mL for cotinine in breastmilk. We imputed ½ the LOQ (i.e., 0.013 ng/ml) for breastmilk cotinine non-detects. NNAL concentrations in breastmilk were determined by LC-MS/MS using a published method.32 One mL aliquots of breastmilk were extracted and analyzed. The LOQ was 1 picogram (pg) per mL.

3. Data Analyses

Overall taxonomic profiles were analyzed at the level of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) for α-diversity (i.e., number of observed OTUs and Shannon diversity) and β-diversity based on the weighted and unweighted UniFrac distance.18,33 The number of observed OTUs characterized the richness of the community, whereas the Shannon diversity index characterized the richness and how evenly distributed the taxa were.18 Of the 164 bacteria genera detected in the 40 infant stool samples, we selected 8 taxa and 2 α-diversity indices to regress on 3 THS-related exposure variables. We also examined 2 beta (β) diversity indices by household smoking status.

The 8 genera were selected post-hoc based on investigative team consultations, significant findings reported in the literature for the NICU environment and preterm infants,1,34 and significant findings with adults18 and children17 examining microbiome associations with cigarette/tobacco/nicotine use and exposure. Specifically, we analyzed Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides, Enterococcus, Enterobacter, Escherichia/Shigella, Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, and Veillonella. For preterm infants, 4 phases of gut microbiome development have been demonstrated—characterized by dominance of Staphylococcus, Enterococcus, Enterobacter, and Bifidobacterium.34 Bifidobacterium is widely studied and especially important for healthy infant gut microbiome development.35,36 Enterococcus and Staphylococcus were each shown in a microbiome cluster-based analysis to be associated with 2-year non-optimal outcomes (i.e., death or developmental delay) in a cohort of 577 infants born before 32 weeks gestational age.1 Enterobacter, as well as Escherichia/Shigella, have been found in NICUs and both are known to contribute to nosocomial infections.37 A recent study in children ≤5 years old found differences in 3 taxonomic areas (Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Veillonella) based on degree of THS, across several human microbiomes (i.e., finger, ear, nose, and mouth).17 Adults who smoke had lower Shannon diversity and lower Bacteroides levels in their gut microbiomes compared to electronic nicotine devices (ENDS) users and controls.18

Forty infants contributed data to the microbiome analyses. We used the ATIMA (Agile Toolkit for Incisive Microbial Analyses) software to generate visual depictions of α-diversity, β-diversity, and taxa-abundance outcomes, as well as Mann-Whitney tests.22 Bayesian data analyses were conducted with R version 4.0.238 via rstan39 and brms.40,41 The 2 α-diversity indices (number of OTUs and Shannon diversity) were modeled as lognormal and skew-normal processes, respectively. Differences in β-diversity were assessed using weighted and unweighted Unifrac principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) and significance determined by Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA).33 Negative binomial regression was used to model the relative abundances of 8 gut microbiome bacteria. All 11 univariate outcomes were modelled as functions of three measures related to THS exposure: household smoking status, infant urine cotinine, and bedside-furniture surface nicotine, and included 4 covariates associated with microbiome colonization (i.e., gestational age, postnatal age at sample collection, antibiotic use [prior to stool sampling; yes/no], and receipt of breastmilk [prior to stool sampling; yes/no]).7,34

Bayesian statistical inference42,43 directly provided probabilities for associations of each THS variable with model outcomes. Models used vague, neutral priors (b= ~Normal [μ=0, σ2=105], sigma= ~Student-t [μ=0, σ2=105]) to maximize the influence of the data on posterior probabilities.44 From the Bayesian perspective, outcomes will be evaluated via posterior probability (PP) threshold guidelines in the literature,45,46 suggesting that PP from 75% to 90% denotes “moderate” evidence, PP from 91% to 96% indicates “strong” evidence, and 97% or above indicates “very strong” to “extreme” evidence. The threshold PP ≥ 75% will be a minimum value to denote a meaningful probability in favor of the alternative hypothesis (i.e., that regression coefficients were either negative [b<0] or positive [b>0]).

Consistent with prior research on pre-term infants first 60 postnatal days of microbiome development,34 we conducted sensitivity analyses excluding 5 infants sampled after this age, as infants over 60 days postnatal age may have significantly different gut microbiomes. Also, Mann-Whitney tests were performed for the α-diversity and β-diversity indices and for the 8 taxa analyzed (with false discovery rate [FDR]-adjusted p values reported), consistent with studies reporting dual frequentist and Bayesian outcomes.42,43 Descriptive statistics of cotinine levels are reported for the 20 samples collected from mothers who were still breastfeeding or pumping, and NNAL values are reported for a subset of mothers (n=12) who provided breastmilk samples for this exploratory analysis.

4. Results

4.1. Analytical cohort

Mothers predominantly were racial/ethnic minorities (n=35; 81.4%) and had a mean age of 30 years. A majority of mothers from smoking households did not smoke but lived with individuals who smoked (n=26; 81.3%).

Of the 40 matched infants with analyzed stool, a majority were Caesarian deliveries, were born preterm (<37 weeks gestational age), received ≥1 antibiotic(s), and received some breastmilk, with a median age of 18.5 days at the time of stool and breastmilk collection—87.5% (n=35) gave a stool sample prior to postnatal day 60. Differences across participant, infant, and household variables were common across smoking (n=32) and non-smoking households (n=11; see Table 1). For example, infants from smoking households received a mean of 1.7 antibiotics compared to 1.0 antibiotics for infants from non-smoking homes.

Table 1.

Participant, Infant, and Household Characteristics by Household Smoking Status

| Characteristic | Non-Smoking Homes | Smoking Homes |

|---|---|---|

| Sample size, n (%) | 11 | 32 |

| Available Data, n (%) | ||

| Stool and Breastmilk | 7 (63.6%) | 10 (31.3%) |

| Stool only | 3 (27.3%) | 20 (62.5%) |

| Breastmilk only | 1 (9.1%) | 2 (6.3%) |

| Household type, n (%) | ||

| Completely cigarette/tobacco/nicotine free | 7 (63.6%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Participant lives with individual(s) who smoke | 0 (0.0%) | 26 (81.3%) |

| Participant lives with individual who uses ENDS | 3 (27.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Participant smokes, others do not | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (15.6%) |

| Participant and others smoke | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (3.1%) |

| Participant uses smokeless tobacco, others do not | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Participant lives with smokeless tobacco user(s) | 1 (9.1%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Participant Characteristics | ||

| Female (participant), n (%) | 11 (100%) | 32 (100%) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| American Indian/Alaskan Native/Asian/Other | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (6.3%) |

| Black/African-American | 1 (9.1%) | 17 (53.1%) |

| Hispanic | 5 (45.5%) | 10 (31.3%) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 5 (45.5%) | 3 (9.4%) |

| Participant age (years), M(SD) | 30.8 (4.8) | 29.9 (6.7) |

| Highest education (years), M(SD) | 14.1 (1.5) | 13.3 (2.1) |

| Married or living with partner, n (%) | 11 (100%) | 19 (59.4%) |

| Infant Characteristics | ||

| Female (infant), n (%) | 5 (45.5%) | 14 (43.8%) |

| Vaginal delivery, n (%) | 3 (30.0%) | 7 (23.3%) |

| Birthweight (kilograms [kg]), M(SD) | 2.1 (1.0) | 2.2 (1.1) |

| Gestational age (weeks), M(SD) | 33.2 (4.4) | 32.8 (4.5) |

| Pre-term (<37 weeks gestational age) delivery, n (%) | 8 (72.7%) | 26 (83.5%) |

| Received any breastmilk, n (%) | 10 (90.1%) | 25 (78.1%) |

| Postnatal age at assessment (days), Median (IQR) | 18.0 (12.0-38.0) | 14.5 (9.5-32.0) |

| Received any antibiotics, n (%) | 5 (50.0%) | 22 (73.3%) |

| Number of antibiotics (if any received), M(SD) | 2.0 (1.4) | 1.6 (0.9) |

| Hypoglycemic after delivery, n(%) | 5 (55.6%) | 19 (63.3%) |

| Visitation and Infant Holding | ||

| Days participant visited (out of past 7), M(SD) | 6.1 (1.6) | 6.0 (1.6) |

| Visitation length (hours/day), M(SD) | 6.9 (1.6) | 8.3 (7.4) |

| Infant held (minutes/day), M(SD) | 186.4 (107.2) | 168.4 (137.0) |

| Skin-to-skin holding (minutes/day)A, M(SD) | 83.6 (69.0) | 37.5 (54.8) |

| Participant and Household Cigarette/Tobacco Use and Tobacco Exposure | ||

| Smoking status (participant), n (%) | ||

| Current smoker | 0 (0.0%) | 6 (18.8%) |

| Former smoker | 6 (54.5%) | 10 (31.2%) |

| Never smoker/fewer than 100 cigs/lifetime | 5 (45.5%) | 16 (50%) |

| Typical cigarettes/day (participant)B, M(SD) | 0 (0.0) | 3.8 (3.0) |

| Maternal smoking during pregnancyC, n (%) | ||

| Quit before pregnancy | 5 (83.3%) | 7 (43.8%) |

| Quit during pregnancy (after finding out) | 1 (16.7%) | 6 (37.5%) |

| Cut down or smoked regularly | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (28.8%) |

| Cigarettes/day by all household membersD, n (%) | ||

| <10 cigarettes/day | Not applicable | 19 (59.4%) |

| ≥10 cigarettes/day | Not applicable | 13 (40.6%) |

| Ban smoking in the home and carE, n (%) | 11 (100%) | 14 (43.8%) |

| Ban ENDS use in the home and carE, n (%) | 10 (90.1%) | 27 (84.4%) |

| CO (ppm), M(SD) | 0.9 (0.9) | 3.3 (6.7) |

| Furniture, Urine, and Breastmilk Data | ||

| Furniture nicotine, measured in NICU (μg/m2) | ||

| M(SD) | 0.97 (1.56) | 0.98 (1.29) |

| Median (IQR) | 0.33 (0.15-1.34) | 0.56 (0.14-1.04) |

| Geometric Mean | 0.55 | 0.55 |

| Urine cotinine, measured in NICU (ng/ml) | ||

| M(SD) | 1.87 (5.74) | 1.55 (7.51) |

| Median (IQR) | 0.04 (0.01-0.07) | 0.06 (0.03-0.20) |

| Geometric Mean | 0.07 | 0.10 |

| Breastmilk cotinine, full cohort (n=20; ng/ml) | [n=8] | [n=12] |

| M(SD) | 0.03 (0.03) | 21.1 (72.5) |

| Median (IQR) | 0.01 (0.01-0.05) | 0.16 (0.05-0.41) |

| Geometric Mean | 0.02 | 0.21 |

| Breastmilk cotinine, smokers removed (n=18; ng/ml) | [n=8] | [n=10] |

| M(SD) | 0.03 (0.03) | 0.23 (0.25) |

| Median (IQR) | 0.01 (0.01-0.05) | 0.16 (0.05-0.27) |

| Geometric Mean | 0.02 | 0.11 |

Note. Data collection began in March, 2018 and concluded in October, 2018. Where categories do not add up to the total sample size, the remainder represent missing data. For breastmilk cotinine non-detects (<limit-of-detection; LOD), ½ the LOD (1/2 LOD=0.013 ng+/ml) was imputed and used in central tendency indices calculations.

Some infants were not yet medically cleared for skin-to-skin (“kangaroo”) care at the time of assessment; only responses >0 minutes were used for this calculation.

If the participant was a current smoker.

This question was only asked of mothers who reported any smoking in the previous 12 months.

Smoking households were collapsed into light (<10 cigarettes/day) and heavy smoking households (≥10 cigarettes/day), based on the total number of cigarettes reported for all household members.

Smoking/ENDS bans were dichotomized so that only total bans on smoking or vaping in the home and car, with no exceptions, were treated as bans.

Among infants, 12 infants were an appropriate weight for gestational age and 1 was receiving treatment for neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome. Two infants were treated (successfully) with antibiotics for 7 to 10 days for “medical” necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC; i.e., no surgical intervention was required)—both infants received no food by mouth (NPO) during the antibiotic course but restarted enteral feeds for ≥7 days by the time of stool collection.. Two infants (born to separate mothers who were HIV seropositive [HIV+]) were on ≥4 weeks of antiretroviral medications to prevent HIV infection. One infant had jejunal atresia and 2 infants had gastroschisis, all three of whom had surgery shortly after birth and each of whom had started or restarted enteral feeds for ≥5 days prior to stool collection. Supplement 2 presents α- and β-diversity (weighted and unweighted) indices and a stacked-bar plot for taxonomic abundance for the infants treated for possible NEC and to prevent HIV infection, as well as infants with gastroschisis and jejunal atresia.

Urine-cotinine and furniture-nicotine data (treated as outcomes) are fully characterized in the primary outcome manuscript from the parent study (with a larger sample; N=80)14 and are treated only as predictors herein (see Table 1).

4.2. Microbiome Analyses

Over 6.5 months of data collection, feasibility of stool collection was demonstrated by recruiting 6.2 participants/month. Fewer than 10% (n=3) of mothers refused infant stool collection.

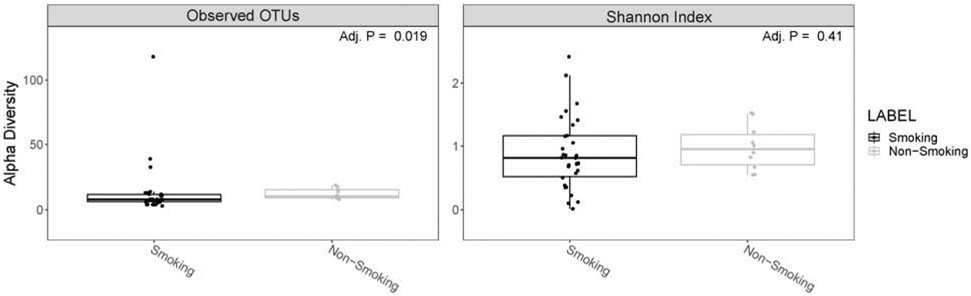

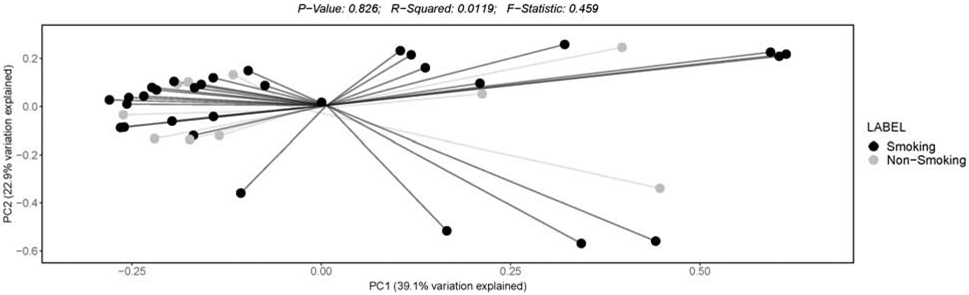

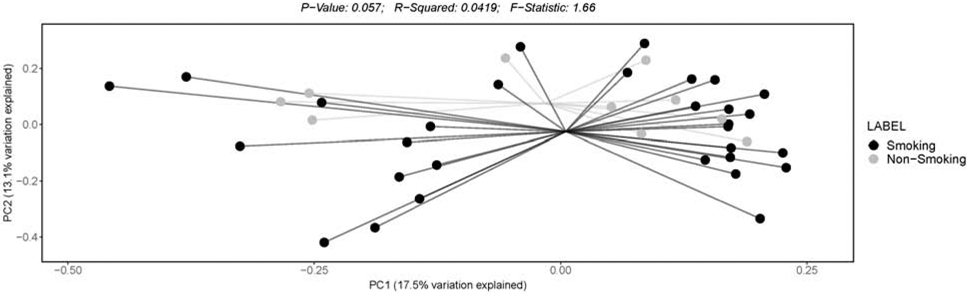

Infants from smoking households (compared to infants from non-smoking households) had less microbiome α-diversity (PP≥75.0%), as demonstrated by both number of OTUs and Shannon diversity indices (see Table 2 and Figure 1). Furthermore, the Mann-Whitney test for observed OTUs was significant (FDR-p=0.02), demonstrating that infants from smoking households (Mdn [IQR]: 8.0 [6.3-11.8]) had lower observed OTUs compared to infants from non-smoking households (Mdn [IQR] 10.5 [9.3-15.5]; see Figure 1). The Shannon Index Mann-Whitney test was not significantly different by household smoking status. Beta diversity (based on weighted and unweighted Unifrac distance PCoA) was not significantly different (p=0.849 [weighted] and p=0.057 [unweighted]) across smoking and non-smoking homes (see Figures 2 and 3, respectively). Infants with higher NICU bedside-furniture surface nicotine had a lower number of OTUs (PP≥75.0%) and higher Shannon diversity indices. The number of OTUs were 25% lower (PP=86.9%) for infants from smoking household and 7% lower for each 1 μg/m2 increase in surface nicotine. The Shannon diversity index models are interpreted as ordinary regression (b) weights, with smoking households homes having b=−0.14 (PP=77.9%) lower index values (compared to non-smoking households) and the index demonstrating a b=0.06 (PP=77.5%) increase in the index per 1 μg/m2 increase in surface nicotine. See Supplement 3 for a scatterplot of α-diversity indices by urine cotinine and surface nicotine values.

Table 2.

Univariate Generalized Linear Models of Bacterial Genera and Alpha Diversity by Surface Nicotine, Infant Urine Cotinine, and Household Smoking Status

| Incidence Rate Ratio [95% CI]; Posterior Probability | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Surface Nicotine | Urine Cotinine | Household Smoking Status (Ref=Non-Smoking Household) |

| Bacterial Genera | |||

| Bacteroides | 0.86 [<0.01, >99.99]; 54.5% | 1.71 [0.67, 13.54]; 76.8% | 20.05 [<0.01, >99.99]; 71.5% |

| Bifidobacterium | 0.01 [<0.01, 64.02]; 87.1% | 0.08 [<0.01, 2.84]; 86.9% | <0.01 [<0.01, 7.38]; 96.0% |

| Enterobacter | 1.00 [0.56, 2.12]; 53.1% | 1.06 [0.93, 1.35]; 71.9% | 1.41 [0.21, 8.06]; 66.0% |

| Enterococcus | 1.17 [0.65, 2.74]; 64.6% | 1.01 [0.88, 1.28]; 50.6% | 4.21 [0.59, 24.78]; 93.4% |

| Escherichia/Shigella | 0.94 [0.37, 4.01]; 60.8% | 0.91 [0.75, 1.28]; 80.7% | 0.86 [0.04, 11.08]; 52.3% |

| Staphylococcus | 1.76 [0.34, 9.391; 72.0%* | 0.94 [0.78, 1.27]; 76.5% | 1.86 [0.13, 16.791; 72.1% |

| Streptococcus | 1.58 [0.71, 4.62]; 83.9% | 0.88 [0.66, 1.18]; 84.3% | 1.13 [0.12, 7.581; 57.5%* |

| Veillonella | 0.48 [0.07, 4.88]; 76.7%† | 1.12 [0.64, 2.00]; 66.7% | 0.41 [0.01, 6.14]; 70.7% |

| Alpha Diversity Indices | |||

| % Change [95% CI]; Posterior Probability | |||

| OTUs | 0.93 [0.76, 1.14]; 76.5%† | 1.01 [0.97, 1.05]; 69.6% | 0.75 [0.45, 1.26]; 86.9% |

| Regression Coefficient (b) [95% CI]; Posterior Probability | |||

| Shannon Index | 0.06 [−0.11, 0.20]; 77.5% | −0.01 [−0.04, 0.021; 73.6% | −0.14 [−0.50, 0.25]; 77.9%† |

Note. Predictors with ≥75.0% posterior probabilities are boldfaced. Bacterial genera outcomes were modeled via the negative binomial distribution. Number of OTUs and the Shannon Diversity Index were modeled as lognormal and skew-normal processes, respectively. Data collection began in March, 2018 and concluded in October, 2018. Incidence rate ratios may be interpreted similarly to odds ratios (e.g., a rate ratio of 1.28 is equivalent to a 28% increase in the bacteria relative abundance per unit increase in the predictor). The lognormal outcome is presented in terms of the % change of OTUs per unit increase in the predictor. The skew normal outcome is interpreted as the change in raw Shannon index value for a one unit increase in the predictor. All models statistically controlled for four covariates, which were: gestational age (week), postnatal day-of-life, whether the infant had received any antibiotics before stool sample collection (yes/no), and whether the infant had received any breastmilk before stool sample collection (yes/no). “OTUs”=“operational taxonomic unit”.

In models that excluded n=5 infants whose stool samples were collected >60 postnatal day-of-life, this predictor’s association with the outcome had a posterior probability ≥75.0%

In models that excluded n=5 infants whose stool samples were collected >60 postnatal day-of-life, this predictor’s association with the outcome had a posterior probability <75.0%.

Figure 1: Boxplots of alpha diversity.

Data are stratified by smoking household status. Smoking households (“Smoking”; black); non-smoking households (“Non-Smoking; gray). Number of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) is depicted on the left side and shannon diversity is depicted on the right side.

Figure 2: Beta diversity assessed by weighted uniFrac principal coordinate analysis (PCoA).

Data are stratified by smoking household status. Smoking households (“Smoking”; black); non-smoking households (“Non-Smoking; gray).

Figure 3: Beta diversity assessed by unweighted uniFrac principal coordinate analysis (PCoA).

Data are stratified by smoking household status. Smoking households (“Smoking”; black); non-smoking households (“Non-Smoking; gray).

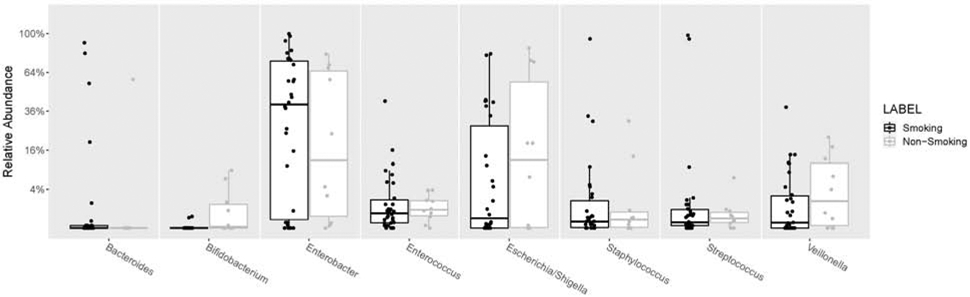

The bacterial genera models demonstrated associations with urine cotinine, surface nicotine, and/or household cigarette use for 7 (out of 8) genera tested. See Supplement 4 for a stacked bar plot of the top-13 taxa’s relative abundances by household smoking status. Relationships between individual bacteria and household smoking status are displayed in Figure 4. Specifically, only the Enterobacter model did not have a meaningful relationship to any of the three THS exposure-related variables. Urine cotinine demonstrated meaningful associations for five bacteria, surface nicotine demonstrated associations with three bacteria, and household smoking status demonstrated relationships for two bacteria (all with PP≥75.0%; see Table 2). See Supplement 5 for scatterplots of the 8 taxa we examined by urine cotinine and surface nicotine values.

Figure 4: Boxplot of bacterial genera relative abundance in stool per household smoking status.

Percentages on the y-axis show the relative abundance for each genera present within individual stool samples. Genera are ordered alphabetically. All 8 analyzed genera were included. Boxes represent interquartile ranges, with lines denoting the median. Smoking households (“Smoking”; black); non-smoking households (“Non-Smoking; gray).

All three THS exposure-related variables were related to lower relative abundance of Bifidobacterium (i.e., >90% reduction in relative abundance per unit increase of each measure). Specifically, higher furniture nicotine was associated with a 99% reduction in Bifidobacterium relative abundance for each 1 μg/m2 increase in surface nicotine (PP=87.1%). Similarly, higher urine cotinine was associated with a 92% lower Bifidobacterium relative abundance for each 1 ng/ml increase in urine cotinine (PP=86.9%). In addition, infants from smoking households had >99% lower Bifidobacterium relative abundance compared to infants from non-smoking homes (PP=96.0%). Furthermore, the Mann-Whitney test of the association between household smoking status and Bifidobacterium was significant (p<0.01; FDR-adjusted p<0.05). Mann-Whitney results were not significant for the other 7 taxa we analyzed by household smoking status.

Streptococcus relative abundance was associated with two (of the three) THS exposure-related variables and in differing directions. Each 1 μg/m2 increase in surface nicotine correlated with a 58% increase in Streptococcus relative abundance (PP=83.9%). A 12% relative abundance reduction was demonstrated for each 1 ng/ml increase in cotinine (PP=84.3%).

Other models found that only one of the THS exposure-related variables was related to the selected bacterial genera relative abundance. Higher levels of urine cotinine were associated with greater Bacteroides abundance (+71% per ng/ml; PP=76.8%) and household smoking was associated with greater Enterococcus abundance (+321% for smoking households compared to non-smoking households; PP=93.4%), respectively. Higher urine cotinine levels were related to lower relative abundance of Escherichia/Shigella (−9% per ng/ml; PP=80.7%) and Staphylococcus (−6% per ng/ml; PP=76.5%). Veillonella relative abundance was 52% lower (PP=76.7%) for each 1 μg/m2 increase in surface nicotine.

We conducted a sensitivity analysis by excluding infants whose data were collected after 60 days postnatal age (see Table 2). Three bacterial genera outcomes associations with THS exposure-related variables changed posterior probabilities (i.e., moved above or below a PP of 0.75) and 2 microbiome diversity indices’ relationships with the THS-related variables changed posterior probabilities. None of these changes involved a change in the direction of the outcomes relationship to the THS-related variable. We also examined α-diversity and β-diversity indices with Mann-Whitney tests and visually inspected stacked bar plots of taxa for 2 covariates (antibiotic exposure [yes/no] and received breastmilk [yes/no]) by household smoking status, as well as for delivery mode (vaginal/Caesarian section [C-section]) by household smoking status (please see Supplements 6 [antibiotics], 7 [breastmilk], and 8 [delivery mode]). Only the unweighted β-diversity was significantly different across smoking and non-smoking homes (i.e., for infants who did not receive antibiotics; p<0.01; see Supplement 6).

4.3. Breastmilk THS Contamination

Feasibility of breastmilk collection was demonstrated among mothers still pumping breastmilk or breastfeeding, as only 16.7% (n=4) refused to provide a sample. Breastmilk sample collection averaged 3.1 breastmilk samples/month. A smaller proportion of mothers from smoking households (n=12, 37.6%), compared to mothers from non-smoking households (n=8, 72.7%), provided breastmilk samples.

Table 1 presents breastmilk cotinine by household smoking status for the “full cohort” (n=20) and with two mothers (who each reported current smoking) excluded (n=18). The 10 mothers who did not smoke and lived in smoking households had a median breastmilk cotinine of 0.16 (IQR: 0.05-0.27), which was approximately fifteen times greater than median breastmilk cotinine observed in mothers from non-smoking homes (median=0.01 [IQR: 0.01-0.05]). The two mothers who reported current smoking had breastmilk-cotinine values of 0.07 (non-daily smoker; reported <1 cigarette/day on average; 0 cigarettes on day-of-assessment) and 251.32 ng/ml (reported 8 cigarettes/day on average; 3 cigarettes on day-of-assessment).

NNAL assays were conducted on 12 breastmilk samples (n=5 mothers lived in completely tobacco/nicotine-free homes [for quality assurance testing/control samples]; n=4 mothers lived with an individual who smoked; n=2 mothers who reported current smoking; n=1 mother lived with an ENDS user). For the two mothers who reported current smoking, we detected 2.4 picograms (pg) of NNAL per mL in the breastmilk sample from the mother who reported non-daily smoking and 13.1 pg/mL in the breastmilk sample of the mother who reported daily smoking and smoking 3 cigarettes on the day of the assessment. NNAL was below the limit-of-quantification in the other 10 samples.

5. Discussion

This exploratory work suggests that infants exposed to higher levels of THS tend to have lower gut microbiome α-diversity, and that THS-related exposure was associated with differences in relative abundance for a majority of the bacterial genera examined. Breastmilk assays suggest that women who live with individuals who smoke (but do not report current smoking themselves) had significantly greater levels of breastmilk cotinine than women who do not smoke and do not live with individuals who smoke. Furthermore, we were the first to detect carcinogenic NNAL in human breastmilk from mothers who report current smoking.

Of the 8 bacterial genera modeled, higher urine cotinine was associated with more taxa (5 out of 8) than was higher surface nicotine (3 out of 8), and higher urine cotinine was associated with higher Bacteroides relative abundance and lower relative abundance of Escherichia/Shigella, Staphylococcus, and Streptococcus. A majority of the statistical associations we reported (based on Bayesian posterior probabilities)45,46 were in the “moderate” range of support that a non-zero relationship existed between THS-related predictors and gut microbiome outcomes. Notably Bifidobacterium and Enterococcus each associated “strongly” with household smoking status.

Regarding relationship magnitudes, Bifidobacterium and Enterococcus each associated to the strongest degree with THS exposure-related variables. Bifidobacterium relative abundance was 90% lower (per unit increase for all three THS exposure-related variables) and Enterococcus relative abundance was 321% higher for infants from smoking households. Household smoking status had the strongest association with these two bacterial genera and with each α-diversity index. This may indicate that THS exposure begins influencing gut-microbiome colonization early in neonatal development. Surface nicotine was related in an opposite direction with Streptococcus (compared to urine-cotinine), as relative abundance increased 58% for each 1 μg/m2 increase in surface nicotine. Surface nicotine was the only variable found to be associated with Veillonella, as greater surface nicotine was related to a 52% decreased relative abundance per 1 μg/m2.

At this early stage of research, Bayesian analysis offers the advantage of avoiding a type-II error common to frequentist approaches, especially when the sample size is small.47 Indeed, many clinical trials are now incorporating Bayesian analytics to evaluate the strength of evidence in favor of a treatment.42,43 Notably, frequentist statistical approaches further bolstered 2 of our Bayesian analytical findings. Specifically, the FDR-adjusted p value supported that Bifidobacterium relative abundances were meaningfully and clinically different based on household smoking status, as did the observed OTUs significance testing.

Statistical differences with gut microbiome outcomes across all 3 THS-related predictors deserves further consideration. Some differences in direction and magnitude may relate to the timeframe over which each variable measures THS-related exposure and how each variable relates to the gut-microbiome outcomes. Household smoking status serves as a proxy for chronic exposure to THS, beginning in utero (as nicotine and other tobacco toxicants have been shown to cross the placenta)48-50 and likely enduring up until the stool sample was collected. When examined as outcomes in our other work,14 finger-nicotine levels and NICU-based furniture surface nicotine contamination were greater in parents who smoke or live with individuals who smoke. Correspondingly, infants from smoking/tobacco-using homes have higher urine cotinine levels, as shown in our parent study primary outcome manuscript from which the current secondary study derived data.14 A majority of infants (>93%) in the NICU, regardless of household smoking status, had quantifiable nicotine on their bedside NICU furniture and quantifiable cotinine in the infants’ urine samples14—making the original household exposure designation (i.e., smoking vs. non-smoking) insufficient by itself for a complete understanding of all sources of infant THS-related exposure.

NICU-based furniture (surface) nicotine is a marker of THS pollution and may serve as a proxy for THS-exposure potential (i.e., a sensitive marker of families’ THS contributions) while infants are hospitalized in the NICU. Compared to surface nicotine, cotinine serves as a gold standard for direct infant exposure to THS over the previous few days.48,51 Cotinine exposure may better demonstrate acute effects of THS on specific bacteria, as cotinine levels were associated with more taxa variations than surface nicotine or household smoking status. Whereas, surface nicotine exposure and household smoking status may be more important for understanding the impact of THS on overall gut microbiome diversity. Relative to surface nicotine and urine cotinine measurements, exposure to other products of tobacco combustion may be measured by assessing household smoking status, as household smoking status related strongly to Enterococcus in a way that the other 2 THS-related variables did not. Also, household smoking status had greater posterior probabilities than surface nicotine and urine cotinine for OTU abundance counts, the Shannon index, and for Bifidobacterium models. Future research may be able to understand the influence of nicotine exposure on gut microbiome development relative to other products of tobacco combustion.

It is important to note that infants who received human breastmilk may also have received nicotine, cotinine, and other tobacco contaminants through breastmilk. In this study, most infants were sampled well after 5 days postpartum—making carryover effects of in utero exposure to nicotine and cotinine unlikely.14,51 Our exploratory breastmilk analyses examined the presence of the tobacco-specific toxicant NNAL and the extent to which cotinine was present in the breastmilk of non-smoking mothers, who live with individuals who smoke. The degree of THS contaminants transmitted through breastmilk is clearly related to microbiome research and under investigated, given the adverse impact of tobacco on protective (immune) properties of breastmilk.19 It is well-established that mothers who smoke cigarettes transmit nicotine and cotinine (i.e., nicotine’s metabolite) through breastmilk. Furthermore, our data add to a growing literature52,53 that cotinine is also transmitted by the breastmilk of non-tobacco users who live with individuals who use tobacco. Our finding of NNAL in the two mothers who reported current smoking and gave breastmilk samples confirmed that NNAL transmits through breastmilk. NNAL is the metabolite of its parent compound, the tobacco-specific nitrosamine NNK, and both are carcinogenic,20 each resulting in 87-90% lung tumors in male F344 rats fed 5.0 parts-per-million (in drinking water) for their lifetime.21 This exposure is potentially concerning for medically vulnerable preterm infants hospitalized in the NICU. Indeed, neonatal exposures to carcinogens may predict development of tobacco-related cancers and other health risks.49

Design and sample limitations affected our ability to model cotinine (in breastmilk) with gut-microbiome outcomes. Our data underscore previous findings that mothers who smoke or live with smokers may stop breastfeeding/pumping earlier than mothers who do not smoke or live with individuals who smoke,54,55 as fewer than 40% of mothers from smoking households provided breastmilk samples, necessitating oversampling of mothers who smoke or live with individuals who smoke to obtain adequate breastmilk samples. Moreover, tobacco-toxicant transmission via breastmilk should be measured on repeated occasions and analyzed with daily NICU feeding data (e.g., specific feeding times and the proportion of breastmilk received by infants, as a proportion of overall feeds), which was a limitation of our electronic health record at the time of data collection.

Transmission of THS (e.g., nicotine) through infant formula and all sources of infant food is necessary, as parents14 and medical staff have been shown to carry nicotine on their hands.12 Supplementation of pre-term infant diets with Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus can effectively modify the gut microbiota and metabolome to more closely resemble full-term infants development,56 and a maternal fecal transplant in Caesarean-delivered infants was recently shown to prevent gut microbiome deviations from vaginally delivered infants.57 A potential concern is whether THS exposure may interfere with such dietary interventions and other natural development. Studying larger cohorts, with repeated samples across the first year of life (particularly when infants are discharged from the NICU to their homes), will allow richer analysis of how THS and tobacco toxicant transmission from caregivers, the surrounding NICU environment, and/or breastmilk may influence the development of the pre-term microbiome.

Implicit in NICU-based research is the heterogeneity of infant morbidity, which can be partially overcome with larger samples, controlling for the influence of co-morbid conditions, and other omitted variables (e.g., delivery method: vaginal/C-section, infant sex), that may also affect gut-microbiome colonization. However, studies with preterm infants often find little or no influence of birth mode on delivery, particularly for studies conducted while infants are hospitalized in the NICU.34,58 In our sample we had 7 infants treated for medical conditions for which the condition (e.g., medical NEC) and/or treatment (e.g., antiretroviral medications) could have an outsized impact on the gut microbiome development. We chose to retain these infants in our analyses, who had all started or restarted enteral feeds for 5 days or longer (e.g., post-delivery, post-surgery or post-NPO status), allowing some colonization or recolonization of the gut microbiome while hospitalized in the NICU.

Due to heterogeneity across relative abundances of genera we examined, and infant characteristics in our sample, we urge caution to avoid overgeneralizing from these findings. Our sample sizes, particularly the sample of infants from non-smoking homes, were small. This contributes to the possibility of capitalization on chance variation from a few infants’ samples with relatively high or low diversity or proportions of an individual taxa (i.e., relative abundance). While our statistical approaches (i.e., Bayesian posterior probabilities, confidence interval reporting, and FDR-adjusted p values) partially guard against capitalization on chance variation, this study needs replication.

Future work will improve on study limitations. For example, several taxa shown elsewhere to be associated with nicotine/tobacco use or exposure18 were not present at sufficient levels (i.e., <10% of samples) for analysis with our sample of infants. Also, we grouped infants from homes where individuals who vape or use smokeless tobacco reside with infants from homes where no vaping or tobacco use (cigarette or smokeless) occurred. However, Stewart and colleagues examined adults who smoked cigarettes, adults who vaped, and non-tobacco/non-nicotine users separately and found minimal microbiome differences between adults who vaped and abstained entirely from nicotine/tobacco,18 supporting our decision to combine these groups at this preliminary stage. Nevertheless, follow-on work with larger samples may choose to separate vaping/smokeless tobacco-using homes from homes where no tobacco use occurs. While a majority of the infants were <60 days of postnatal age, and we controlled for postnatal age, follow-on work should assess infants over a longer period of time, providing better understanding of how the gut microbiome changes and is affected by nicotine/tobacco as infants develop. For example, data suggest there may be 4 distinct phases of microbiome development (i.e., characterized by relative abundance of bacterial genera) in the first 60 days postpartum among infants receiving breastmilk and depending on infants’ gestational age, postmenstrual age, and antibiotic use.34 The latter finding was supported whether infants were born extremely pre-term, moderately or very pre-term.34

This study is the first to demonstrate that THS-related exposure may influence microbiome development during the neonatal period. Our data are consistent with recent work in children ≤5 years of age that children’s microbiomes are potentially affected by THS exposure at levels well below those observed in active and passive smokers.17 THS-related exposure was associated with gut microbiome differences in infants admitted to a NICU, highlighting the need to continue research in this area to promote healthy human development during infancy and into childhood.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Urine cotinine, surface nicotine, and home smoking measured THS-related exposure

NICU infants’ gut microbiome differences were associated with THS-related exposure

Higher THS-related exposure was associated with less alpha diversity

Higher THS-related exposure was associated with 7 of 8 bacterial genera variations

A tobacco-specific carcinogen was detected in human breastmilk

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Mackenzie Spellman, Keyishi Peters, Oreoluwa Oshinowo, Olugbenga Akinwande, Heather Garza, Idorenyin Udoh-Bradford, Dr. Jillian Pottkotter, Christina Maxey, Sylvia Adu-Gyamfi, and Dr. Brian Hite for their help conducting the study. The authors wish to thank Dr. Nathan Dodder and Linda Chu for conducting the analyses of nicotine wipes and for the breastmilk-cotinine assays. The authors also wish to thank Lawrence Chan, Kristina Bello, and Lisa Yu, for adapting the method for NNAL analysis of breastmilk and carrying out the analyses. In addition, the authors would like to thank the staff of the Children’s Memorial Hermann Hospital.

This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (1R03HD088847; PI: T.F. Northrup) at the US National Institutes of Health and Department of Health and Human Services. This work was supported in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01 HL107404, PI: A.L. Stotts) at the U.S. National Institutes of Health and Department of Health and Human Services. Laboratory resources for the analytical chemistry at UCSF were supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (P30 DA012393, PI: P. Jacob, 3rd). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Rozé J-C, Ancel P-Y, Marchand-Martin L, et al. Assessment of Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Practices and Preterm Newborn Gut Microbiota and 2-Year Neurodevelopmental Outcomes. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(9):e2018119–e2018119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen RY, Kung VL, Das S, et al. Duodenal Microbiota in Stunted Undernourished Children with Enteropathy. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(4):321–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shao Y, Forster SC, Tsaliki E, et al. Stunted microbiota and opportunistic pathogen colonization in caesarean-section birth. Nature. 2019;574(7776):117–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biasucci G, Rubini M, Riboni S, Morelli L, Bessi E, Retetangos C. Mode of delivery affects the bacterial community in the newborn gut. Early Hum Dev. 2010;86(1): 13–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marques TM, Wall R, Ross RP, Fitzgerald GF, Ryan CA, Stanton C. Programming infant gut microbiota: influence of dietary and environmental factors. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2010;21(2):149–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holzmann-Pazgal G, Khan AM, Northrup TF, Domonoske C, Eichenwald EC. Decreasing vancomycin utilization in a neonatal intensive care unit. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43(11):1255–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Korpela K, Salonen A, Saxen H, et al. Antibiotics in early life associate with specific gut microbiota signatures in a prospective longitudinal infant cohort. Pediatr Res. 2020:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eck A, Rutten NB, Singendonk MM, et al. Neonatal microbiota development and the effect of early life antibiotics are determined by two distinct settler types. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(2):e0228133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zou Z-H, Liu D, Li H-D, et al. Prenatal and postnatal antibiotic exposure influences the gut microbiota of preterm infants in neonatal intensive care units. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2018;17(1):9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartz LE, Bradshaw W, Brandon DH. Potential NICU environmental influences on the neonate’s microbiome: a systematic review. Advances in neonatal care: official journal of the National Association of Neonatal Nurses. 2015;15(5):324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hewitt KM, Mannino FL, Gonzalez A, et al. Bacterial diversity in two neonatal intensive care units (NICUs). PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e54703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Northrup TF, Stotts AL, Suchting R, et al. Medical staff contributions to thirdhand smoke contamination in a neonatal intensive care unit. Tob Induc Dis. 2019;17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Northrup TF, Khan AM, Jacob P, et al. Thirdhand smoke contamination in hospital settings: Assessing exposure risk for vulnerable paediatric patients. Tob Control. 2016;25(6):619–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Northrup TF, Stotts AL, Suchting R, et al. Thirdhand smoke contamination and infant nicotine exposure in a neonatal intensive care unit: An observational study Nicotine Tob Res. 2021;23(2):373–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pavia CS, Pierre A, Nowakowski J. Antimicrobial activity of nicotine against a spectrum of bacterial and fungal pathogens. J Med Microbiol. 2000;49(7):675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brook I Effects of exposure to smoking on the microbial flora of children and their parents. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74(5):447–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelley ST, Liu W, Quintana PJ, et al. Thirdhand smoke residue is associated with altered microbiomes of preschool-age children and their homes. Pediatr Res. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stewart CJ, Auchtung TA, Ajami NJ, et al. Effects of tobacco smoke and electronic cigarette vapor exposure on the oral and gut microbiota in humans: A pilot study. Peer J. 2018;6:e4693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmed F, Jean-Baptiste F, Thompson A. Effects of maternal tobacco smoking on breast milk composition and infant development: a literature review. J Bacteriol Mycol Open Access. 2019;7(5):107–110. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rivenson A, Hoffmann D, Prokopczyk B, Amin S, Hecht SS. Induction of lung and exocrine pancreas tumors in F344 rats by tobacco-specific and Areca-derived N-nitrosamines. Cancer Res. 1988;48(23):6912–6917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LaVoie EJ, Stern SL, Choi C-I, Reinhardt J, Adams JD. Transfer of the tobacco-specific carcinogens N′-nitrosonornicotine and 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone and benzo [a] into the milk of lactating rats. Carcinogenesis. 1987;8(3):433–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gurwara S, Ajami NJ, Jang A, et al. Dietary nutrients involved in one-carbon metabolism and colonic mucosa-associated gut microbiome in individuals with an endoscopically normal colon. Nutrients. 2019;11 (3):613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galloway-Peña JR, Peterson CB, Malik F, et al. Fecal Microbiome, Metabolites, and Stem Cell Transplant Outcomes: A Single-Center Pilot Study. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2019;6(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stewart CJ, Ajami NJ, O’Brien JL, et al. Temporal development of the gut microbiome in early childhood from the TEDDY study. Nature. 2018;562(7728):583–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matt GE, Quintana PJ, Zakarian JM, et al. When smokers move out and non-smokers move in: Residential thirdhand smoke pollution and exposure. Tob Control. 2011;20(1):e1–e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matt GE, Quintana PJ, Fortmann AL, et al. Thirdhand smoke and exposure in California hotels: Non-smoking rooms fail to protect non-smoking hotel guests from tobacco smoke exposure. Tob Control. 2013;23(3):264–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matt GE, Quintana PJ, Hovell MF, et al. Households contaminated by environmental tobacco smoke: Sources of infant exposures. Tob Control. 2004;13(1):29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quintana PJ, Matt GE, Chatfield D, Zakarian JM, Fortmann AL, Hoh E. Wipe sampling for nicotine as a marker of thirdhand tobacco smoke contamination on surfaces in homes, cars, and hotels. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(9):1555–1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matt GE, Quintana PJ, Hoh E, et al. A Casino goes smoke free: a longitudinal study of secondhand and thirdhand smoke pollution and exposure. Tob Control. 2018;27:643–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacob P, Yu L, Duan M, Ramos L, Yturralde O, Benowitz NL. Determination of the nicotine metabolites cotinine and trans-3′-hydroxycotinine in biologic fluids of smokers and non-smokers using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry: Biomarkers for tobacco smoke exposure and for phenotyping cytochrome P450 2A6 activity. J Chromatogr B. 2011;879(3):267–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quintana PJ, Hoh E, Dodder NG, et al. Nicotine levels in silicone wristband samplers worn by children exposed to secondhand smoke and electronic cigarette vapor are highly correlated with child’s urinary cotinine. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2019;29:733–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jacob P III, Havel C, Lee D-H, Yu L, Eisner MD, Benowitz NL. Subpicogram per milliliter determination of the tobacco-specific carcinogen metabolite 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol in human urine using liquid chromatography– tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2008;80(21):8115–8121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lozupone C, Hamady M, Knight R. UniFrac – An online tool for comparing microbial community diversity in a phylogenetic context. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7(1):371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Korpela K, Blakstad EW, Moltu SJ, et al. Intestinal microbiota development and gestational age in preterm neonates. Scientific reports. 2018;8(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Granger CL, Embleton ND, Palmer JM, Lamb CA, Berrington JE, Stewart CJ. Maternal breastmilk, infant gut microbiome and the impact on preterm infant health. Acta Paediatr. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Masi AC, Stewart CJ. The role of the preterm intestinal microbiome in sepsis and necrotising enterocolitis. Early Hum Dev. 2019;138:104854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bokulich NA, Mills DA, Underwood MA. Surface microbes in the neonatal intensive care unit: changes with routine cleaning and over time. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51(8):2617–2624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.RCoreTeam. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. . 2020; https://www.R-project.org. Accessed October 29, 2018, 2018.

- 39.Stan Development Team. RStan, the R interface to Stan. R package version 2.19.3. 2020; http://mc-stan.org/. Accessed December 11, 2019.

- 40.Bürkner PC. Advanced Bayesian Multilevel Modeling with the R Package brms The R Journal. 2018;10(1):395–411. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bürkner PC. brms: An R package for Bayesian multilevel models using Stan. Journal of Statistical Software. 2017;80(1):1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gelman A, Carlin JB, Stern HS, Dunson DB, Vehtari A, Rubin DB. Bayesian data analysis. Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 43.McElreath R Statistical rethinking: A Bayesian course with examples in R and Stan. Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suchting R, Yoon JH, San Miguel GG, et al. Preliminary examination of the orexin system on relapse-related factors in cocaine use disorder. Brain Res. 2019:146359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jeffreys H Theory of probability, Clarendon. Oxford; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee MD, Wagenmakers EJ. Bayesian cognitive modeling: A practical course. Cambridge university press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wijeysundera DN, Austin PC, Hux JE, Beattie WS, Laupacis A. Bayesian statistical inference enhances the interpretation of contemporary randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(1):13–21 e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Benowitz NL, Hukkanen J, Jacob P III. Nicotine chemistry, metabolism, kinetics and biomarkers. Nicotine Psychopharmacology. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer; 2009:29–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Benowitz NL, Flanagan CA, Thomas TK, et al. Urine 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3) pyridyl-1-butanol and cotinine in Alaska native postpartum women and neonates comparing smokers and smokeless tobacco users. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2018;77(1):1528125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Correa E, Joshi PA, Castonguay A, Schüller HM. The Tobacco-specific Nitrosamine 4-(Methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone Is an Active Transplancental Carcinogen in Syrian Golden Hamsters. Cancer Res. 1990;50(11):3435–3438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dempsey D, Jacob P, Benowitz NL. Nicotine metabolism and elimination kinetics in newborns*. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2000;67(5):458–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schwartz-Bickenbach D, Schulte-Hobein B, Abt S, Plum C, Nau H. Smoking and passive smoking during pregnancy and early infancy: effects on birth weight, lactation period, and cotinine concentrations in mother's milk and infant's urine. Toxicol Lett. 1987;35(1):73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Szukalska M, Merritt TA, Lorenc W, et al. Toxic metals in human milk in relation to tobacco smoke exposure. Environ Res. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Northrup TF, Wootton SH, Evans PW, Stotts AL. Breastfeeding practices in mothers of high-respiratory-risk NICU infants: Impact of depressive symptoms and smoking. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 2013;26(18):1838–1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Northrup TF, Suchting R, Green C, Khan AM, Klawans MR, Stotts AL. Duration of breastmilk feeding of NICU graduates who live with individuals who smoke. Pediatr Res. In Press:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alcon-Giner C, Dalby MJ, Caim S, et al. Microbiota supplementation with Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus modifies the preterm infant gut microbiota and metabolome: an observational study. Cell Reports Medicine. 2020;1(5):100077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Korpela K, Helve O, Kolho K-L, et al. Maternal Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Cesarean-Born Infants Rapidly Restores Normal Gut Microbial Development: A Proof-of-Concept Study. Cell. 2020;183(2):324–334.e325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stewart CJ, Embleton ND, Clements E, et al. Cesarean or Vaginal Birth Does Not Impact the Longitudinal Development of the Gut Microbiome in a Cohort of Exclusively Preterm Infants. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2017;8(1008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.