Highlights

The toxicity issue of lead-based halide perovskites hinders theirs large-scale commercial applications in solar cells.

A variety of non- or low-toxic perovskite materials have been used for development of environmentally friendly lead-free perovskite solar cells, some of which show excellent optoelectronic properties and device performances.

At present, more new lead-free perovskite materials with tunable optical and electrical properties are urgently required to design highly efficient and stable lead-free perovskite solar cells.

Keywords: Solar cells, Perovskite, Lead-free, First-principles calculation, Photovoltaic

Abstract

The toxicity issue of lead hinders large-scale commercial production and photovoltaic field application of lead halide perovskites. Some novel non- or low-toxic perovskite materials have been explored for development of environmentally friendly lead-free perovskite solar cells (PSCs). This review studies the substitution of equivalent/heterovalent metals for Pb based on first-principles calculation, summarizes the theoretical basis of lead-free perovskites, and screens out some promising lead-free candidates with suitable bandgap, optical, and electrical properties. Then, it reports notable achievements for the experimental studies of lead-free perovskites to date, including the crystal structure and material bandgap for all of lead-free materials and photovoltaic performance and stability for corresponding devices. The review finally discusses challenges facing the successful development and commercialization of lead-free PSCs and predicts the prospect of lead-free PSCs in the future.

Introduction

As a major driving force of the world today, traditional fossil fuels have been essential from the first industrial revolution. Although previous industrial revolutions have brought human society into an unprecedented boom era, they have simultaneously caused tremendous energy and resource consumption and aggravated the contradiction between human and nature, making us have to pay a huge environmental price and ecological cost. With the fast development of world’s economy and social productive forces, the requirement of energy has also been growing rapidly and the traditional fossil energy has been incapable of meeting our demands. So entering the twenty-first century, humanity has been facing unprecedented challenges of global crises of energy and resource, environment, ecology, and climate change. All of these issues have initiated the fourth industrial revolution, namely the green industrial revolution. At this time, solar energy as the initial source of all energy inevitably becomes new support for human and social development due to its advantages of pollution-free, renewability, huge energy, and so on. Optoelectronic conversion as one of the major utilizations of solar energy has been widely researched in the past several decades, and solar cells belong to the most important type of optoelectronic converters. The development of low-cost, high-efficiency solar cells has become a central issue in recent years. And perovskite solar cells (PSCs), as a promising class of solar cells family, have attracted intensive attention in the past decade due to high absorption coefficient, excellent bipolar charge mobility, long carrier diffusion length, low exciton binding energy, low trap state density, and tunable bandgap.

The power conversion efficiency (PCE) of PSCs based on lead (Pb) perovskites has been dramatically improved from the initial 3.8% to recently certified value of 25.2% [1–24]. However, there exist unavoidable shortcomings in these Pb-based high-efficiency PSCs (e.g., MAPbI3, FAPbI3, Cs0.05FA0.85MA0.10Pb(I0.97Br0.03)3), that is, the element lead is toxic to the environment and organisms and difficult to discharge from the body. Research indicates that the contamination of lead ions to soil and water sources is permanent and generates a very serious negative impact on human, animal, and plant survival [25–34]. The human’s nervous, digestive and blood systems eventually show functional disorders in the case of lead poisoning since lead can enter human’s body, bind with enzyme and finally store in soft tissues and bones such as spleen, kidney, liver, and brain through blood circulation. Generally, most people show lead toxic symptoms when lead intake reaches about 0.5 mg/day [25–27]. Therefore, to guarantee human’s safe and pollution-free natural environment it is necessary to develop some non- or low-toxic metal ions to replace lead as perovskite absorbers of PSCs [28–34].

Generally, metal halide perovskites have a universal chemical formula of ABX3, where A is an organic cation, B is a metal cation and X is a halogen anion [35–55]. Here, the organic cation usually includes methylammonium (MA), formamidinium (FA), Cs, or their mixture, and the halogen anion consists of Cl, Br, I or their mixture. For B, previous work has showed that less toxic ions like Sn2+, Bi3+, Ge2+, Sb3+, Mn2+, and Cu2+ could be used as an alternative ion to Pb2+ in perovskites to constitute a new lead-free perovskite structure [56–63]. The introduction of these metal cations not only increases the diversity of perovskite species, but also enhances environmentally friendly features of PSCs.

This review mainly focuses on various lead-free perovskite materials and related solar cell applications by summarizing recent work about theoretical bases and experimental studies of those lead-free perovskites. Specifically, it summarizes the replacement of Pb with other possible isovalent and heterovalent elements proposed recently. Herein, the isovalent elements consisting of Sn (II), Ge (II) and divalent transition metals (e.g., Cu, Fe, Zn), and the heterovalent elements containing Bi(III), Sb (III), Sn (IV), Ti (IV) and double cations of Ag(I)Bi(III) are summarized. The crystal structure and bandgap for all of lead-free materials and their corresponding photovoltaic performance and stability are included. And by comparing various types of lead-free perovskite materials, we finally predict development prospects of lead-free perovskite materials in the future.

Theoretical Bases of Lead-Free Hybrid Perovskites

First-principles calculation based on density functional theory (DFT) is a modeling method for simulating the electronic structures of many-body systems from atomic-scale quantum mechanics. This method has been used as an important tool for the study of lead-free perovskites [64, 65]. Electronic structures of various lead-free perovskites were calculated by researchers to simulate their electron/hole effective masses, theoretical absorption spectra, carrier mobilities, bandgaps, and other properties related to their potential solar cell applications by first-principles calculations in order to find the optimal MAPbI3 substitute [67–70]. Generally speaking, there exist a variety of options of exchange–correlation functions in DFT calculations, which will qualitatively affect the result of DFT calculations. In the past research work, researchers often chose local density approximation (LDA) and generalized gradient approximation (GGA) functionals. Although their functions are relatively simple, the calculation results are generally more reliable. But this does not mean that there are no problems. LDA and GGA exhibit serendipitous cancellations between their exchange–correlation parts, which lead to unphysical electron self-interactions. This result further causes the local (LDA) and semilocal (GGA) functions to essentially underestimate the bandgaps of solids by 30–100% [67, 68]. To solve such problems, methods/functions including the many-body perturbation (GW) approximation [65], time-dependent DFT (TDDFT) [66], PBE0, HSE03, and HSE06 hybrid functionals [64–70], and more recent delta self-consistent-field method have been developed and applied to recent theoretical calculations of lead-free perovskites. It is worth emphasizing that in the presence of heavy atoms, spin–orbit coupling (SOC) must be included in the calculation to achieve a more accurate prediction of the electronic structure.

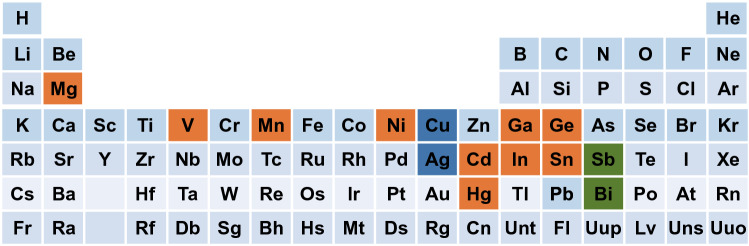

So far, researchers have already had a certain understanding of the lead-free perovskite system after several years of targeted research. The core of research on lead-free perovskite materials is the replacement of Pb element. Researchers have screened out a series of elements that could replace Pb through theoretical calculations (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Potential elements to substitute Pb. The orange shading on the periodic table marks the screened elements by Filip et al. that can replace Pb. The green shading of the VA group heterovalent elements and the blue shading of transition metal elements have also been calculated or proved to substitute Pb. (Color figure online)

Filip et al. considered stability and desired bandgap as two concurrent prerequisites for suitable candidates of lead-free perovskites [66]. They used randomly displaced structures (atom positions and lattice parameters) to investigate the stability of possible lead-free perovskites. Making the stability and desired calculated bandgap as two concurrent conditions, the crystal structure retains the perovskite geometry after relaxation of the shaken configurations, and the relativistic bandgap is smaller than 2.0 eV. Finally, they identified 10 compounds out of 248 candidates for possible solar cell applications with high-throughput screening, as shown in Fig. 1. After calculation, AMgI3 exhibited as a promising candidate with tunable bandgap between 0.9 and 1.7 eV (1.7 eV for CsMgI3, 1.5 eV for CH3NH3MgI3 and 0.9 eV for CH(NH2)2MgI3) and low electron effective mass, which is caused by exceptionally dispersive conduction bands [66]. Therefore, Filip et al. deduced that the substitution of Pb by Mg was theoretically feasible to reduce the toxicity of metal halide perovskites without losing solar cell efficiency substantially. In subsequent research work, the researchers have also proved that Cu, Ag, Bi and Sb can also replace Pb to form perovskites (Fig. 1) [62–66].

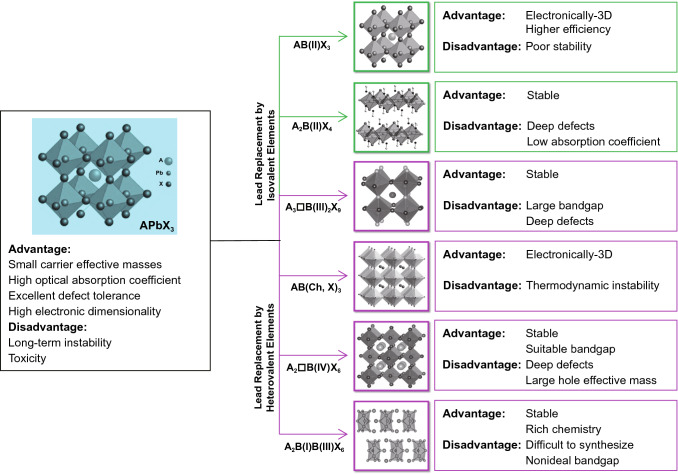

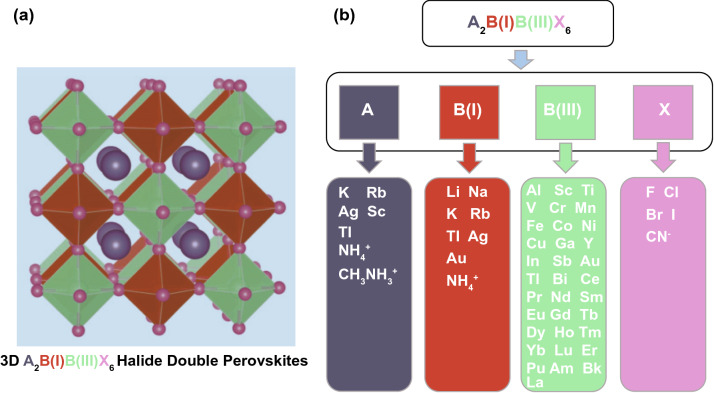

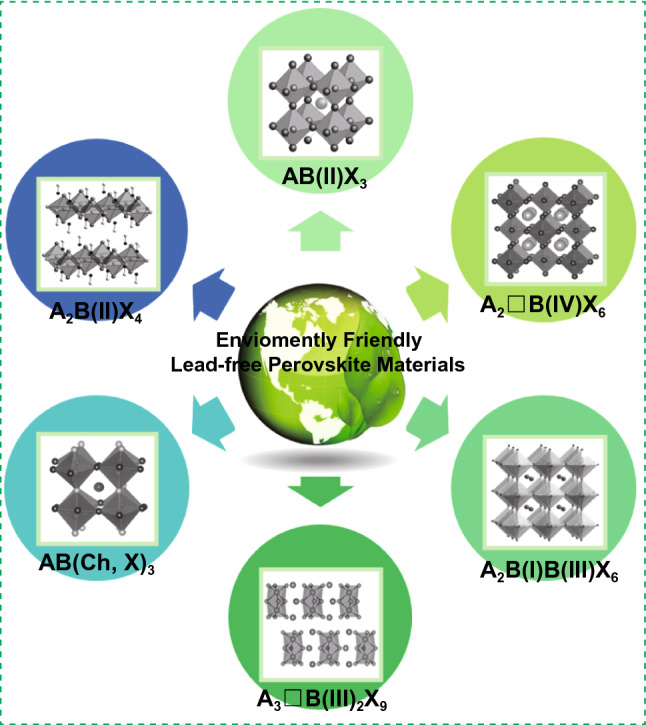

In addition, it is possible to use valence state replacement to select suitable non-toxic elements by using the first-principles calculation [59, 64–75]. Usually, as shown in Fig. 2, we can replace the Pb element with either homovalent elements such as Sn, Ge, and Cu, or heterovalent elements such as Sb and Bi. To maintain the charge neutrality, the heterovalent replacement can be divided into three subcategories: cation splitting, mixed valence anion and ordered vacancy. Cation splitting is to form a double perovskite structure with a chemical formula of A2B(I)B(III)X3 by splitting Pb into a combination of monovalent and trivalent cations. Introducing mixed valence anions is the case with a single valence cation but two valence anions, whose general chemical formula is AB(Ch, X)3, where Ch represents a chalcogen element and X represents a halogen element. The perovskite can maintain electrical neutrality via forming ordered vacancies. Such substitutions can also be divided into two types: the B(III) compounds with a formula of A3□B(III)X9 and the B(IV) compounds with a formula of A2□B(IV)X6. Here, the sign of □ indicates vacancies. However, the formation of vacancies cuts the original 3D perovskite structure into a low dimension crystal structure, thereby reducing the electronic dimension and then affecting the optoelectronic performance [67].

Fig. 2.

Schematic illustration of the approaches and consequences of potential Pb replacement

Researchers have conducted a lot of theoretical studies on the Pb replacement with various elements, e.g., Sn, Ge, and Bi [57–62]. These theoretical studies reveal the advantages and disadvantages of different lead-free perovskite materials. In the substitution of homovalent elements, take Sn-based perovskite MASnI3 as an example. In the process of studying the optoelectronic properties of MASnI3 using the GW + SOC method, the researchers found that compared with MAPbI3, MASnI3 showed a stronger s-p antibond coupling near the maximum value of the valence band (VBM) [68]. This phenomenon is due to the fact that the Sn 5s lone pair is shallower and more active than the Pb 6s lone pair. In addition, because of much weaker SOC, the Sn 5p orbital is shallower and less dispersive than the Pb 6p orbitals. As a result, compared to MAPbI3, the bandgap of MASnI3 is reduced. Unfortunately, defect calculations indicated that the high-energy Sn 5s2 state makes the Sn-I bond easy to break, forming high-density Sn vacancies, resulting in an excessively high defect density (> 1017 cm−3) in the Sn-based perovskite [68]. Similar to Sn-based perovskite, theoretical calculations by Ming et al. indicated that the Ge vacancy in Ge-based perovskite is the dominant defect with shallow transition levels and rather low formation enthalpy, which yields high-density holes, particularly at Ge-poor synthesis conditions [33]. At the same time, Sun et al. pointed out that the stability of MAGeI3 is better than that of MASnI3 based on the calculation of the formation energy of the compound. In addition, they calculated the electronic structure and improved bandgap results through the hybrid function HSE06 and the spin–orbit coupling [36]. The calculated band structure showed that the bottom of the conduction band and the top of the valence band are very dispersed, which corresponds to low electron/hole effective masses. These results mean that the replacement of Pb in perovskite by Ge is possible.

In the theoretical study of heterovalent replacement, using Cs3Bi2I9 as an example, the calculations using hybrid Heyd–Scuseria–Ernzerhof (HSE) functional with SOC indicated that Cs3Bi2I9 exhibits an indirect bandgap of 2.10 eV from the Γ point to the K point [40, 51]. Moreover, the defect calculations by Ghosh et al. indicated that most of the defects in Cs3Bi2I9 that have low formation energies generate deep level states in the bandgap, which act as recombination centers [51]. Fortunately, this type of perovskite material has been calculated to own excellent thermodynamic stability.

In addition, the chalcogen–halogen hybrid perovskite AB(Ch, X)3 was systematically studied by Sun et al. with Ab initio molecular dynamics, GGA functions and DFT-D3 van der Waals scheme [52]. According to relevant calculations, they predicted that MABiSI2 and MABiSeI2 have the best bandgap (1.3–1.4 eV) for solar energy collection materials. However, in later studies, Hong et al. combined DFT calculations and solid-state reactions to prove that all proposed AB(Ch, X)3 perovskites are thermodynamically unstable [34]. Although this result is disappointing, it also reminds us that stability analysis is equally important in the theoretical calculation of the discovery of new lead-free perovskites.

Recently, the theoretical calculation has proved the 0D electronic dimension and larger bandgap of double perovskite A2B(I)B(III)X6 with the use of alkali metal B(I) cation [28, 29]. Actually, transition metal B(III) cations with multiple oxidation states and/or partially occupying d or f orbitals are not ideal for the design of photovoltaic absorbers because they may introduce deeper defect states and localized bandedges. Finally, regarding the screening of X anions, it is known that iodides and bromides have the potential of obtaining narrower bandgaps, but they are thermodynamically unstable, while fluorides and chlorides are relatively stable but usually have larger bandgaps [75–78]. The above theoretical research work undoubtedly played a guiding role in the application of new-type lead-free perovskite materials in perovskite solar cells, resulting in a rapid development of this field.

Experimental Investigation of Various Types of Lead-Free Hybrid Perovskites

Lead Replacement by Isovalent Elements

Sn-based Perovskite

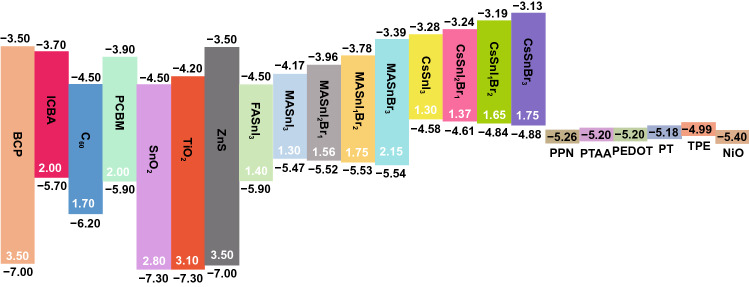

As a chemical element of Pb’s family (IVA group), Sn2+ possesses a homologous lone-pair s orbital and similar radius (1.35 Å) to Pb2+ (1.49 Å); therefore, Sn-based perovskites show superior optoelectronic properties similar with Pb [68, 69]. In addition, they also exhibit narrower optical bandgaps (1.2–1.4 eV) and higher carrier mobilities than the Pb-based counterparts. Moreover, due to intrinsic low toxicity of Sn, the Sn-based perovskite absorbers have become the important candidate for lead-free perovskites and gradually turned into the research hotspot in high-performance lead-free PSCs [68–70]. As a result, the Sn-based perovskites are more suitable for efficient single-junction solar cell applications. However, Sn2+ is unstable and easily oxidized to Sn4+. The formation of Sn4+ leads to p-type self-doping in Sn-based perovskites, which will generate numerous Sn vacancies with large background carrier density and rapid recombination of charge carriers [14], leading to serious performance degradation and poor reproducibility of PSCs using Sn-based perovskites as absorbers [26–30].

3D Sn-based Perovskite

MASn(I,Br)3

The first MASnIBr2 perovskite solar cell was realized with a PCE of 5.7% in 2014 [70], whose PCE was then quickly refreshed to 6.4% by Zhao in the same year [71]. In 2015, Umari et al. investigated the optoelectronic properties of MASnI3 with a more advanced many-body perturbation theory involved with SOC [68]. They found MASnI3 exhibited a higher charge mobility of 102–103 cm2 V−1 s−1 [68, 69], a smaller direct bandgap of 1.1 eV at the Γ point and a higher absorption coefficient of 1.82 × 104 cm−1 in the visible region than MAPbI3, whose mobility, bandgap and absorption coefficient of the latter are 10–102 cm2 V−1 s−1, 1.5 eV and 1.80 × 104 cm−1, respectively [56, 70]. These pretty results encouraged researchers to pay more attention to Sn-based perovskites. Interestingly, Sn-based perovskite materials exhibit n-type semiconductor characteristics when the internal Sn2+ content ratio is high, and p-type semiconductor characteristics when the Sn4+ content ratio is high. Until now plenty of efforts have been dedicated to development of high-performance and air-stable Sn-based perovskite solar cells [33, 34]. Poor homogeneity and low coverage are critical issues to be solved in Sn-based perovskites, which usually lead to direct contact between the hole-transporting layer (HTL) and the electron-transporting layer (ETL), thus generating low PCEs [70, 72]. Here, film formation methods suitable for Pb-based perovskites tend to become inefficient for Sn-based cases due to a faster crystallization rate of Sn-based perovskites [73, 74]; for instance, one-step method with common solvent of N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) or γ-butyrolactone (GBL) hardly realized smooth Sn-based perovskite films on flat substrates. Hao et al. studied the effect of solvent on the crystallization of MASnI3 perovskite film and found that adding dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) retarded the perovskite crystallization via the formation of a stable intermediate adduct SnI2·3DMSO (Fig. 3a), the film formation speed of which was eventually controlled by the evaporation rate of DMSO. As the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images shown in Fig. 3a–d, the morphologies of MASnI3 films with DMSO showed the highest coverage and pinhole–free property on mesoporous TiO2 [74]. Moreover, N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) was also investigated as a solvent to further understand the effect of the intermediate phase on the tin perovskite formation process. As a result, a high-quality, pinhole-free CH3NH3SnI3 films are achieved using NMP as solvents [73, 74].

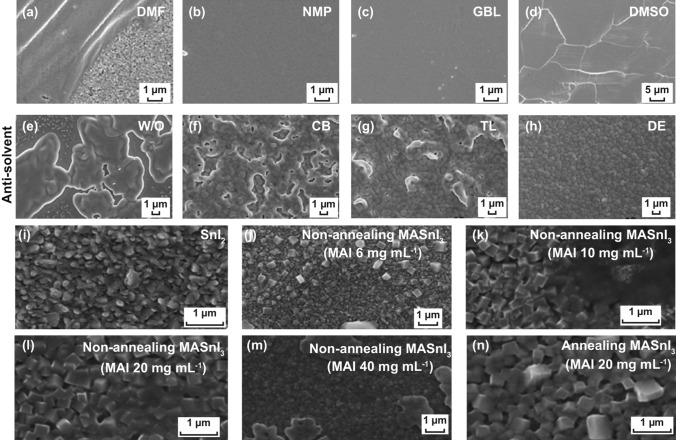

Fig. 3.

SEM images for MASnI3 layer on mesoporous TiO2 layer by using a DMF, b NMP, c GBL, and d DMSO solvents. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [74]. SEM images for FASnI3 films obtained from different antisolvent processes: e No dripping, f CB, g TL and h DE. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [96]. SEM images of i vapor deposited 100 nm SnI2, non-annealing MASnI3 films with j 6, k 10, l 20 and m 40 mg mL−1 MAI precursor solution spin coated and n MASnI3 films with 20 mg mL−1 MAI precursor solution spin coated followed by annealing at 80 °C for 10 min. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [75]

Multi-step film formation method was another efficient approach to achieve high-quality Sn-based perovskite films [19, 56, 75, 76]. Schlettwein et al. reported an approach combined thermal evaporation with solution process to fabricate MASnI3 perovskite films [56, 76]. The SnI2 layers prepared by vapor thermal deposition could be converted to MASnI3 by sequentially spin coating MAI solution. The as-acquired sizes of MASnI3 grains were over 200 nm (Fig. 3i–n) [75]. Moreover, the film morphologies were highly dependent on MAI concentrations. With the increasing concentration of MAI, larger and more uniform MASnI3 crystals were obtained (Fig. 3i–n). After 10-min thermal annealing, high-quality and dense films were achieved with significantly improved stability. The films remained stable after exposure to air for 90 min under both dark and light conditions.

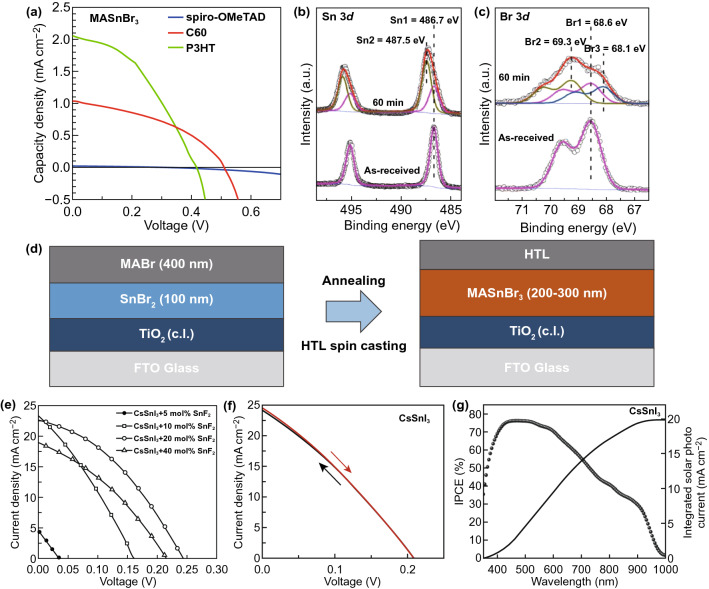

In addition to the above approaches, Qi et al. invented a method to improve the quality of MASn(I, Br)3-based perovskite film. They used co-evaporation and sequential evaporation methods to fabricate MASnBr3 perovskite films with SnBr2 and MABr as precursors [77]. For co-evaporation, they used a 4:1 MABr/SnBr2 deposition ratio (0.4:0.1 Å s−1) to simultaneously evaporate the two materials, and finally produced a perovskite film with a thickness of about 400 nm. However, solar cells based on this film only showed a low PCE of 0.35% (Fig. 4a). Such a low PCE was resulted from the oxidation of Sn2+ which restrained the generation of excitons, the carriers diffusion, and the final charge extraction. As a melioration, Qi et al. then employed sequential deposition method to decrease oxidation (Fig. 4b, c) and realized a relatively high PCE of 1.12% because oxidation can be significantly avoided by the top MABr layer [77]. The specific operation is first to deposit a 100-nm film of SnBr2, and then to precipitate a following 400-nm film of MABr (Fig. 4d). The as-deposited sample was transferred from the vacuum system to a N2 glovebox for post-annealing so as to convert the two-layer sample to MASnBr3 perovskite. Therefore, sequential evaporation approach could be an efficient approach for fabricating high-quality Sn-based perovskites.

-

(2)

CsSn(I,Br)3

In 1974, Fisher et al. first synthesized and characterized all-inorganic CsSnX3 compounds [78]. It was not until 2012, Shum et al. reported the application of CsSnI3 in perovskite solar cell [79]. A black thin film of CsSnI3 with a bandgap of 1.3 eV was fabricated by alternate depositions of SnCl2 and CsI on a glass substrate followed by a thermal annealing process. The CsSnI3 perovskite solar cell exhibited a PCE of 0.9%. Then in 2014, Mathews et al. reported a CsSnI3 PSC incorporated with SnF2 to reduce Sn vacancies and obtain a high photocurrent output [71]. The best PCE of 2.02% as well as a short-circuit current density (Jsc) of 22.70 mA cm−2, an open-circuit voltage (Voc) of 0.24 V and a fill factor (FF) of 0.37 was achieved with 20 mol % SnF2 (Fig. 4e). Moreover, the devices displayed less hysteresis than those counterparts without SnF2 (Fig. 4f). The incident photon-to-current conversion efficiency (IPCE) data clearly indicated that the onset was extended to 950 nm, which corresponded to 1.3 eV of bandgap (Fig. 4g). In 2015, a detailed study on CsSnX3 was done by Sabba et al. [80]. Their studies revealed that the CsSnX3 materials were semiconductors with a strong tendency to self-doping because the oxidation of Sn2+ to Sn4+ would generate hole carriers.

Fig. 4.

a J–V curves of co-evaporated MASnBr3 films with different hole transport materials. b Sn 3d and c Br 3d XPS results of MASnBr3 films as-deposited and after 1 h stored in air. d Fabrication of sequential method for MASnBr3 films. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [77]. e J–V curves of CsSnI3-based PSCs incorporated with different ratios of SnF2. f J–V curves of 20 mol % SnF2-doped CsSnI3 devices showing no hysteresis. g IPCE spectrum for 20 mol % SnF2-doped CsSnI3 devices. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [71]

It is worth mentioning that CsSnI3 as a 3D p-type orthorhombic perovskite possesses a bandgap of 1.3 eV [81], a low exciton binding energy of 18 × 10−3 eV [82], and a high optical absorption coefficient of 104 cm−1 (comparable to MAPbI3) [83]. Therefore, it has the potential to be as a light absorber for lead-free PSCs. The biggest obstacle that hinders rapid development of CsSnI3 perovskite solar cell is the instability of CsSnI3 and the black phase CsSnI3 could be easily converted to yellow phase CsSnI3 in atmosphere due to its oxidization [69, 84]. It was reported that the excessive SnI2 contributed to the improvements of efficiency and stability of CsSnI3-based PSCs [85]. The CsSnI3 films with low defect density and high surface coverage were prepared in a Sn-rich environment or at high temperature. The PCE of the device with a configuration of ITO/CuI/CsSnI3/fullerene/bathocuproine (BCP)/Al increased from 0.75 to 1.5% in the condition of 10 mol % excessive SnI2, and Voc and FF remained good within 20 min under light stability. Although Jsc quickly deteriorated by 10% in the first 50 min, Jsc’s decline rate slowed significantly. The excess of SnI2 located at the CsSnI3/CuI interface formed an interfacial dipole which acted as a hole-transporting layer from CsSnI3 to CuI owing to a favorable vacuum level shift.

After that, some additives have been introduced into precursors to further improve film quality of CsSn(I,Br)3 perovskites, which have significantly promoted the performances of CsSn(I,Br)3 perovskite solar cells [86–90]. Marshall et al. systematically investigated CsSnI3 perovskite films with different Sn halide additives, such as SnF2, SnCl2, SnI2, and SnBr2 [90]. The films adding SnCl2 additive had the highest pinhole density and the HTL-free devices with 10 mol % SnCl2 achieved the highest FF and PCE. Such results were mainly attributed to the formation of ultrathin hole-selective layer of SnCl2 at the ITO/CsSnI3 interface.

On this basis, doping Br into CsSnI3 was also proposed. It is noteworthy that the Br-doped CsSnI3−xBrx perovskites showed a much higher FF compared to CsSnI3 due to the appearance of the negligible overlayer of CsSnI3−xBrx [80]. The crystal structure was thus changed from orthorhombic (CsSnI3) to cubic (CsSnBr3) with the increase in Br component. The onset of optical bandgap edge was also altered from 1.27 eV (CsSnI3) to 1.37, 1.65, and 1.75 eV for CsSnI2Br, CsSnIBr2 and CsSnBr3, respectively (Fig. 5). Notably, CsSnI2Br, CsSnIBr2 and CsSnBr3 were suitable for solar cell applications due to their excellent thermal and air stabilities (Table 1) [80].

-

(3)

FASn(I,Br)3

Compared to MA+ and Cs+, FA+ is another extensively investigated organic cation with a relatively larger ionic radius. FASnI3 is a 3D perovskite with a bandgap of 1.41 eV, which is slightly wider than MASnI3 (1.30 eV) and CsSnI3 (1.30 eV) [37] but narrower than Pb-based perovskites (~ 1.5 eV) [69]. Moreover, the bandgaps of FASnX3 can be tuned with different halides, e.g., 1.68 and 2.4 eV for FASnI2Br and FASnBr3 [78, 91]. The FASnI3 material exhibits a threshold charge-carrier density of 8 × 1017 cm−3 and a charge-carrier mobility of 22 cm2 V−1 s−1 [92]. In addition, FASnI3 has a similar thermal stability but a lower conductivity with respect to MASnI3 [93].

Fig. 5.

Energy diagram of common Sn-based perovskites, ETLs and HTLs. Unit: eV

Table 1.

Photovoltaic parameters of PSCs based on various Sn-based perovskite absorbers. In the table, c-TiO2 and m-TiO2 represent compact and mesoporous TiO2 layer, respectively

| Preparation process | Absorber | Device architecture | Voc (V) | Jsc (mA cm−2) | FF (%) | PCE (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-step | MASnI3 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/spiro-MeOTAD/Au | 0.68 | 16.30 | 48 | 5.23 | [70] |

| One-step | MASnI2Br | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/spiro-MeOTAD/Au | 0.77 | 14.38 | 50 | 5.48 | [70] |

| One-step | MASnIBr2 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/spiro-MeOTAD/Au | 0.82 | 12.30 | 57 | 5.73 | [70] |

| One-step | MASnBr3 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/spiro-MeOTAD/Au | 0.88 | 8.26 | 59 | 4.27 | [70] |

| One-step | MASnI3 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/spiro-MeOTAD/Au | 0.716 | 15.18 | 50.07 | 5.44 | [135] |

| One-step | MASnI3 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/spiro-MeOTAD/Au | 0.88 | 16.8 | 42 | 6.4 | [82] |

| One-step | MASnI3 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/spiro-MeOTAD/Au | 0.79 | 13.40 | 52 | 5.49 | [124] |

| One-step | CsSnI3 + 20% SnF2 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/spiro-MeOTAD/Au | 0.201 | 27.67 | 29 | 1.66 | [91] |

| One-step | CsSnI2Br + 20% SnF2 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/spiro-MeOTAD/Au | 0.289 | 15.06 | 38 | 1.67 | [91] |

| One-step | CsSnIBr2 + 20% SnF2 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/spiro-MeOTAD/Au | 0.311 | 11.57 | 43 | 1.56 | [91] |

| One-step | CsSnI2.9Br0.1 + 20% SnF2 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/spiro-MeOTAD/Au | 0.222 | 24.16 | 33 | 1.76 | [91] |

| One-step | FASnI3 + 20% SnF2 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/spiro-MeOTAD/Au | 0.238 | 24.45 | 36 | 2.10 | [99] |

| One-step | CsSnBr3 + 20% SnF2 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/spiro-MeOTAD/Au | 0.42 | 9.1 | 57 | 2.17 | [89] |

| One-step | MASnIBr2 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/spiro-MeOTAD/Au | 0.69 | 15.9 | 49 | 5.36 | [134] |

| One-step | MASnI3 + 20% SnF2 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/PTAA/Au | 0.25 | 26.1 | 30 | 1.94 | [137] |

| One-step | {en}FASnI3 + 15% SnF2 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/PTAA/Au | 0.48 | 22.54 | 65.96 | 7.14 | [81] |

| One-step | {en}FASnI3 + 15% SnF2 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/PTAA/Au | 0.46 | 22.54 | 69.74 | 7.23 | [138] |

| One-step | {PN}FASnI3 + 15% SnF2 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/TPE/Au | 0.44 | 22.15 | 60.67 | 5.85 | [109] |

| One-step | {TN}FASnI3 + 15% SnF2 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/PTAA/Au | 0.40 | 22.72 | 61.04 | 5.53 | [109] |

| One-step | {en}MASnI3 + 15% SnF2 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/PTAA/Au | 0.43 | 24.28 | 63.72 | 6.63 | [108] |

| One-step | MASnBr3 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/PTAA/Au | 0.307 | 1.22 | 36.8 | 0.14 | [139] |

| One-step | CsSnI3 + 20% SnF2 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/m-MTDATA/Au | 0.24 | 22.70 | 37 | 2.02 | [88] |

| One-step | MASnCl3 | c-TiO2/perovskite/CuSCN/Ag | 0.576 | 12.89 | 55 | 3.41 | [140] |

| One-step | CsSnI3 | NiO/perovskite/PCBM/Al | 0.52 | 10.21 | 62.5 | 3.31 | [141] |

| One-step | CsSnI3 | c-TiO2/perovskite/spiro-MeOTAD/Au | 0.48 | 8.11 | 19.8 | 0.77 | [141] |

| One-step | HEA0.4FA0.6SnI3 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/Al2O3/C | 0.37 | 18.52 | 56.2 | 3.9 | [118] |

| One-step | GA0.2FA0.78SnI3 + 1% EDAI2 | PEDOT:PSS/perovskite/C60/BCP/Ag | 0.61 | 21.2 | 72 | 9.6 | [119] |

| One-step | FASnI3 | PEDOT:PSS/perovskite/PCBM/BCP/Ag | 0.49 | 22.24 | 65.19 | 7.15 | [101] |

| One-step | FASnI3 | SnO2/perovskite/PCBM/BCP/Ag | 0.55 | 19.39 | 68.82 | 7.34 | [102] |

| One-step | FASnI3 | PEDOT:PSS/perovskite/C60/BCP/Ag | 0.63 | 21.6 | 74.7 | 10.17 | [103] |

| One-step | FASnI3 | PEDOT:PSS/perovskite/C60/BCP/Ag | 0.628 | 22.25 | 74.2 | 10.37 | [104] |

| One-step | PEAxFA1−xSnI3 + NH4SCN | PEDOT:PSS/perovskite/ICBA/BCP/Ag | 0.94 | 17.4 | 75 | 12.4 | [135] |

| One-step | FASnI3 + 5% PHCl | PEDOT:PSS/perovskite/C60/BCP/Ag | 0.76 | 23.5 | 64 | 11.4 | [136] |

| Hot-casting | BA2MA3Sn4I13 + 100% SnF2 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/PTAA/Au | 0.229 | 24.1 | 45.7 | 2.53 | [120] |

| Hot-casting | MASnI3 + 20% SnF2/hydrazine | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/PTAA/Au | 0.378 | 19.92 | 51.73 | 3.89 | [142] |

| Hot-casting | CsSnI3 + 20% SnF2/hydrazine | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/PTAA/Au | 0.170 | 30.75 | 34.88 | 1.83 | [142] |

| Hot-casting | CsSnBr3 + 20% SnF2 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/PTAA/Au | 0.367 | 13.96 | 59.36 | 3.04 | [142] |

| Hot-casting | MASnI3 | PEDOT/perovskite/PCBM/Al | 0.595 | 17.8 | 29.8 | 3.2 | [143] |

| Vapor-assisted | MASnI3 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/PTAA/Au | 0.273 | 17.36 | 39.1 | 1.86 | [143] |

| Vapor-assisted | MASnI3−xBrx | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/PTAA/Au | 0.452 | 5.02 | 48.3 | 1.10 | [139] |

| Solvent-engineering | FASnI3 + 10% SnF2 + pyrazine | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/spiro-MeOTAD/Au | 0.32 | 23.7 | 63 | 4.8 | [71] |

| Solvent-engineering | FASnI3 + 20% SnF2 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/spiro-MeOTAD/Au | 0.38 | 23.09 | 60.01 | 5.27 | [97] |

| Solvent-engineering | MASnI3 + 20% SnF2 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/spiro-MeOTAD/Au | 0.232 | 26.0 | 38.6 | 2.33 | [134] |

| Solvent-engineering | FASnI3 + 10% SnF2 | PEDOT:PSS/perovskite/C60/BCP/Ag | 0.47 | 22.07 | 60.67 | 6.22 | [96] |

| Solvent-engineering | FASnI3 + 20% PEAI + 10% SnF2 | NiO/perovskite/PCBM/Al | 0.59 | 14.44 | 69 | 5.94 | [127] |

| Solvent-engineering | (FA)0.75(MA)0.25SnI3 + 10% SnF2 | PEDOT:PSS/perovskite/C60/BCP/Ag | 0.61 | 21.2 | 62.7 | 8.12 | [80] |

| Solvent-engineering | (FA)0.5(MA)0.5SnI3 + 10% SnF2 | PEDOT:PSS/perovskite/C60/BCP/Ag | 0.53 | 21.3 | 52.4 | 5.92 | [80] |

| Solvent-engineering | (FA)0.25(MA)0.75SnI3 + 10% SnF2 | PEDOT:PSS/perovskite/C60/BCP/Ag | 0.48 | 20.7 | 45.2 | 4.49 | [80] |

| Solvent-engineering | FASnI3 + 10% SnF2 | PEDOT:PSS/perovskite/C60/BCP/Ag | 0.48 | 21.3 | 64.6 | 6.60 | [80] |

| Solvent-engineering | MASnI3 + 10% SnF2 | PEDOT:PSS/perovskite/C60/BCP/Ag | 0.46 | 21.4 | 42.7 | 4.29 | [80] |

| Solvent-engineering | 0.92FASnI3 + 0.08PEAI + 10% SnF2 | PEDOT:PSS/perovskite/C60/BCP/Ag | 0.525 | 24.1 | 71 | 9.0 | [144] |

| Solvent-engineering | FASnI2Br | PEDOT:PSS/perovskite/C60/Ca/Al | 0.467 | 6.82 | 54 | 1.72 | [89] |

| Solvent-engineering | MA0.9Cs0.1SnI3 | PEDOT:PSS/perovskite/PCBM/Bis-C60/Ag | 0.20 | 4.53 | 36.4 | 0.33 | [114] |

| Solvent-engineering | FA0.8Cs0.2SnI3 | PEDOT:PSS/perovskite/PCBM/Bis-C60/Ag | 0.24 | 16.05 | 35.8 | 1.38 | [114] |

| Solvent-engineering | FASnI3 | PEDOT:PSS/perovskite/PCBM/Bis-C60/Ag | 0.04 | 11.73 | 23.4 | 0.11 | [114] |

| Solvent-engineering | PEA2SnI4 | NiOx/perovskite/PCBM/BCP/Ag | 0.61 | 22.0 | 70.1 | 9.41 | [123] |

| Solvent-engineering | (BA0.5PEA0.5)2FA3Sn4I13 | PEDOT:PSS/perovskite/C60/LiF/Al | 0.60 | 21.82 | 66.73 | 8.82 | [126] |

| Solvent-engineering | AVA2FAn−1SnnI3n+1 | PEDOT:PSS/perovskite/PCBM/BCP/Ag | 0.61 | 21.0 | 68 | 8.71 | [128] |

| Solvent-engineering | (4AMP)(FA)3Sn4I13 | c-TiO2/ZrO2/perovskite/C | 0.64 | 14.9 | 44.3 | 4.42 | [131] |

| Quantum rods | CsSnI3 | c-TiO2/perovskite/spiro-MeOTAD/Au | 0.86 | 23.2 | 65 | 12.96 | [145] |

| Quantum rods | CsSnBr3 | c-TiO2/perovskite/spiro-MeOTAD/Au | 0.85 | 21.23 | 58 | 10.46 | [145] |

| Quantum rods | CsSnCl3 | c-TiO2/perovskite/spiro-MeOTAD/Au | 0.87 | 19.82 | 56 | 9.66 | [145] |

| Sequential deposition | FASnI3 + 10% SnF2 + TMA | SnO2/C60/perovskite/spiro-MeOTAD/Ag | 0.31 | 21.65 | 64.7 | 4.34 | [83] |

| Sequential deposition | FASnI3 + 10% SnF2 + TMA | PEDOT:PSS/perovskite/C60/Bis-C60/Ag | 0.47 | 22.45 | 0.68 | 7.09 | [83] |

| Sequential deposition | FASnI3 | PEDOT:PSS/perovskite/C60/BCP/Ag | 0.33 | 17.78 | 67.9 | 3.98 | [146] |

| Thermal evaporation | MASnBr3 | c-TiO2/perovskite/P3HT/Au | 0.498 | 4.27 | 49.1 | 1.12 | [77] |

| Thermal evaporation | CsSnBr3 + 2.5% SnF2 | MoO3/perovskite/C60/BCP/Ag | 0.40 | 2.4 | 55 | 0.55 | [147] |

| Thermal evaporation | (PEA, FA) SnI3 | LiF/PEDOT:PSS/perovskite/C60/BCP/Ag | 0.47 | 20.07 | 74 | 6.98 | [148] |

| Thermal evaporation | MASnI3 | PEDOT:PSS/TPD/perovskite/C60/BCP/Ag | 0.377 | 12.1 | 36.6 | 1.7 | [149] |

| Thermal evaporation | CsSnI3 | ITO/perovskite/Au/Ti | 0.42 | 4.80 | 22 | 0.88 | [87] |

| Direct dropping | MASnIBr1.8Cl0.2 + 20% SnF2 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/m-Al2O3/perovskite/C | 0.38 | 13.99 | 57.3 | 3.11 | [150] |

| Hot-dropping | CsSnIBr2 + 60% SnF2 + H3PO2 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/m-Al2O3/perovskite/C | 0.31 | 17.4 | 56 | 3.2 | [151] |

| Solvent-engineering | FASnI3 + PEABr + 10% SnF2 | PEDOT:PSS/perovskite/C60/BCP/Cu | 0.45 | 24.87 | 63 | 7.05 | [152] |

| Solvent-engineering | FASnI3 + 2.5% N2H5Cl + 10% SnF2 | PEDOT:PSS/perovskite/PCBM/BCP/Ag | 0.455 | 17.64 | 67.3 | 5.40 | [153] |

| Solvent-engineering | FASnI3 + 12% SnF2 | PEDOT:PSS(PEG)/perovskite/PCBM/BCP/Ag | 0.455 | 17.64 | 67.3 | 5.40 | [153] |

| Solvent-engineering | MASnI3 + 20% SnF2 | PEDOT:PSS/perovskite/C60/BCP/Ag | 0.45 | 11.82 | 40 | 2.14 | [154] |

| Solvent-engineering | FASnI3 + 1% EDAI2 | PEDOT:PSS/perovskite/C60/BCP/Ag | 0.583 | 21.3 | 0.72 | 8.9 | [155] |

| Solvent-engineering | FASnI3 | PEDOT:PSS/perovskite/C60/BCP/Ag | 0.638 | 21.95 | 0.725 | 10.16 | [156] |

Synthesis and characterization of cubic FASnI3 perovskite were first investigated in 1997 [94]. Until now, most high-performance Sn-based PSCs are mainly based on FASnI3 materials [95–97] because of their better air stability. This is because the trap density of FASnI3 (n-type semiconductor) is as low as ~ 1011 cm−3, preventing water and oxygen from entering into the FASnI3 crystal, which has been experimentally proved by Wang et al. [98]. Therefore, the air stability of the FASnI3 crystal is higher than MASnI3 one.

After the first successful incorporation of SnF2 into CsSnI3, Mathews group further verified similar effect of SnF2 additive on performance enhancements of FASnI3-based solar cells. SnF2 additive played a similar role in preventing oxidation of Sn2+ to Sn4+ and reducing background carrier density, and the FASnI3 PSC with 20% SnF2 finally achieved a PCE of 2.1% [99].

However, it has been proven that a higher amount of SnF2 induced severe phase separation in the FASnI3 perovskites films and thus led to performance degradation of solar cells. To solve this issue, Seok et al. introduced pyrazine into DMF/DMSO mixed precursor solution to fabricate high-quality FASnI3 films with high coverage and smooth surface [87]. Since the N atoms in pyrazine can accept lone pairs electrons, pyrazine doping can remarkably restrict the phase separation and effectively reduce Sn vacancies [84], with which a dense, smooth, and pinhole-free FASnI3 perovskite layer and a pretty good PCE of 4.8% were achieved with high reproducibility. Furthermore, the encapsulated solar cells exhibited good long-term stability, remaining 98% of the initial PCE for over 10-day storage under ambient condition. It is worth mentioning that, in addition to SnF2 and pyrazine, hydrazine vapor, hydrazine iodide [69], and Sn powder [100] have also been used as antioxidants in Sn-based perovskites in later work. The application of these antioxidants has a similar effect with SnF2, that is, to improve the stability and efficiency of Sn-based PSCs by reducing Sn vacancies and background carriers in Sn perovskites.

In addition, some other special materials have also been served as additives to improve the film quality of perovskites and hinder the oxidation of Sn2+. For instance, Chen et al. used the bidentate ligand 8-hydroxyquinoline (8HQ) as an additive in the perovskite [101]. The N and O atoms in the 8HQ can simultaneously coordinate with Sn2+ and greatly inhibit the oxidation of Sn2+. Meantime, the formation of complex also improved the quality of FASnI3 film and reduced defect state-induced non-radiative recombination. Recently, ammonium hypophosphite was introduced into the FASnI3 perovskite precursor by Yan et al. to suppress the oxidation of Sn2+ and assist the growth of perovskite grains, resulting in improved perovskite film quality and reduced defect density, and the final device showed a PCE of 7.3% [102]. More importantly, about 50% of their original PCE was maintained after the 500 h storage in air. Soon after, Han et al. employed a π-conjugated Lewis base molecule 2-cyano-3-[5-[4-(diphenylamino)phenyl]-2-thienyl]-propenoic acid (CDTA) with high electron density to systematically control the crystallization rate of FASnI3 perovskite [103]. They obtained a compact and uniform perovskite film with greatly increased carrier lifetime via forming stable intermediate phase with the Sn-I frameworks. Meanwhile, the introduction of the π-conjugated system also retarded the permeation of moisture into perovskite crystal, which significantly suppressed the film degradation in air [103]. The perovskite solar cell prepared on this basis achieved a PCE of 10.1% and maintained over 90% of its initial value after 1000 h light soaking in air. Another work is Han et al. introduced a liquid formic acid as a reducing solvent in the FASnI3 perovskite precursor solution to product the FASnI3 perovskite film with high crystallinity, low Sn4+ content, reduced background doping, and low electronic trap density. As a result, the lead-free tin halide PSC achieved 10.37% efficiency [104].

In addition to additives, the use of antisolvents also greatly promoted the film quality of FASnI3 perovskites. Typical antisolvents include chlorobenzene (CB) [105], toluene (TL) [106], diethyl ether (DE) [107], and other aprotic nonpolar solvents. Here, it is noteworthy that the antisolvents should be miscible with DMSO solvent, but insoluble for perovskites. Liao et al. used such a solvent-engineering method to fabricate FASnI3 perovskites and tuned the film morphologies with different antisolvents (Fig. 3e–h) [96]. They obtained high-quality, uniform and fully covered FASnI3 perovskite thin films. Among these antisolvents, dripping with diethyl ether onto FASnI3 produced the best FASnI3 thin films with high uniformity and full coverage. With improved film quality and proper structure design, the champion FASnI3 device achieved a PCE of 6.22% with Voc of 0.465 V, Jsc of 22.07 mA cm−2, and FF of 60.67%. Furthermore, such device exhibited a weak J–V hysteresis behavior [96].

Recently, a new type of “hollow” perovskites has been prepared. Chen et al. reported a successful incorporation of medium size cations ethylenediammonium (en) into the 3D FASnI3 perovskite structure and they denoted it as {en}FASnI3 [91, 108]. Typically, change of A-site cation only results in a small bandgap alteration due to structural distortion, but for {en}FASnI3, its bandgap can be tuned in a wide range of 1.3–1.9 eV via simply increasing the en amount [108]. Actually, adding en could improve film morphology, reduce background carrier density and increase carrier lifetime, all of which contribute to the resultant PCE and stability of Sn-based solar cells [70]. Based on this viewpoint, the {en}FASnI3 device achieved a 7.14% PCE with higher Voc and FF. Similar results were also observed in MASnI3 and CsSnI3 solar cells [108]. Recently, Kanatzidis et al. also reported two other diammonium cations of propylenediammonium (PN) and trimethylenediammonium (TN) forming new hollow perovskites of {TN}FASnI3 and {PN}FASnI3 [109]. TN and PN with slightly larger size than en also improved device performances. The FASnI3 absorbers mixed with 10% PN and 10% TN achieved enhanced PCEs of 5.85% and 5.53%, respectively [109].

-

(4)

Mixed A Cations Sn-Based Perovskites

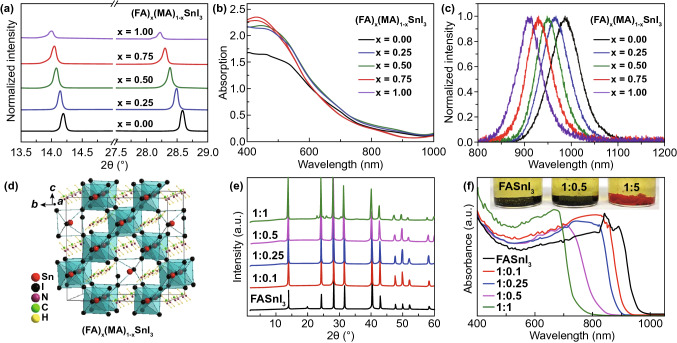

Metal halide perovskites with mixed cations have been widely used in Pb-based PSCs, part of which achieved record efficiencies and good stability due to cation mixture-triggered film morphology improvement and water and oxygen resistance increase as well as inhibition of carrier recombination within devices [20, 22, 110–113]. In this case, it is also a powerful strategy to develop highly efficient, stable Sn-based PSCs with mixed A cations perovskites. Liu et al. first synthesized Sn-based perovskites with mixed cations of MA and Cs and applied MA0.9Cs0.1SnI3 to PSCs [114]. The PCE was low (0.33%) since the device was fabricated without any optimization. Later, Zhao et al. reported 3D Sn-based perovskites with mixed cations of MA and FA (Fig. 6d). Notably, the optical property exhibited an obvious alteration with the ratio of mixed cations (Fig. 6a–c, e–f). Among them, (FA)0.75(MA)0.25SnI3 perovskite solar cell with 10 mol % SnF2 generated a maximum PCE of 8.12% and an average value of 7.48% ± 0.52% [88].

Fig. 6.

a XRD patterns of one-step deposited (FA)x(MA)1−xSnI3 (x = 0.00, 0.25, 0.50, 0.75, and 1.00) films on ITO/poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)-poly(styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS) substrates. b Absorption spectra and c normalized PL spectra of the different perovskite films on quartz substrates. d A 2 × 2 × 2 supercell of (FA)2Sn2I6 depicting a model of the hollow perovskite with two SnI2 vacancies [(FA)16Sn14I44]. e XRD patterns and f optical absorption of the {en}FASnI3 perovskite crystals with various molar ratios of FA to {en}. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [88]

Low-Dimensional Sn-Based Perovskite

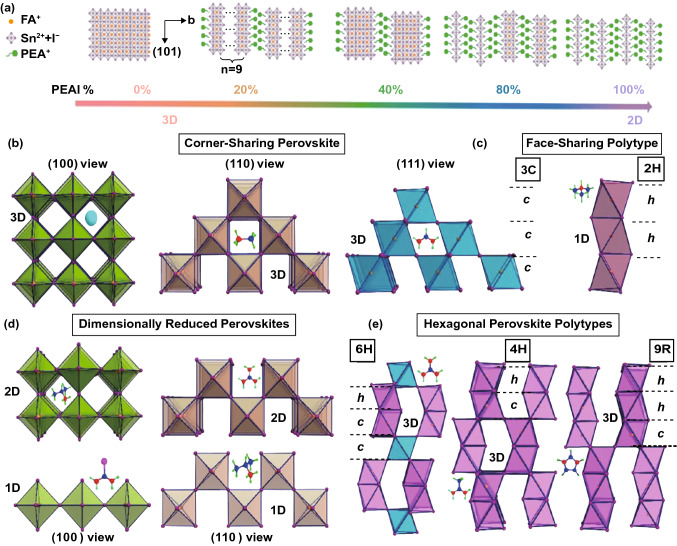

As an alternative, reduced-dimensional (quasi-2D) perovskites have been widely investigated recently since they have showed superior enduring stability outperforming their 3D counterparts [115–117]. The existence of insulating organic spacer cations, e.g., PN [89], 2-hydroxyethylammonium (HEA) [118], guanidinium (GA) [119], butylammonium (BA) [120], polyethylenimine cation [121], cyclopropylammonium [122], and phenylethylammonium (PEA) on quasi-2D perovskites, restrains self-doping effect and suppresses ion migration [115, 121], thus contributing to ameliorated moisture, oxygen, and thermal stability. However, the emergence of these insulating long-chain organic cations also leads to the anisotropy characteristics of the crystal, which significantly reduces device performance. That means the resulting quasi-2D PSCs with enhanced stability are at the expense of declining performance due to blocked charge transportation of these insulating organic spacers along vertical direction [95, 120, 123]. The highly vertically oriented perovskite films are considered as a prerequisite to address the low-efficiency issue in quasi-2D PSCs since in this situation these inorganic slabs are aligned in perpendicular to the substrates [124, 125]. Various methods of forming highly vertically oriented films have been developed in Pb-based quasi-2D perovskites, but unfortunately, most of which are unsuitable for Sn-based counterparts due to different properties between Pb- and Sn-based perovskites [123, 124]. In the published cases of Sn-based PSCs, Kanatzidis et al. reported 2D Ruddlesden–Popper (RP) perovskites (CH3(CH2)3NH3)2(CH3NH3)n−1SnnI3n+1 with perpendicular orientation by using N,N-dimethylformamide as solvent [120]. For n = 4, perpendicularly oriented 2D perovskites were fabricated whether the substrates were heated or not, while for n = 3, only hot substrates of 120 centigrade were able to intensify perpendicular growth of 2D films. Huang et al. introduced mixed n-butylamine and PEA organic cations into 2D RP Sn perovskite to control the crystallization process and formed highly vertically oriented [(BA0.5PEA0.5)2FA3Sn4I13] 2D RP perovskites [126]. Benefitting from it, the PCE of the 2D Sn-based PSC was improved to 8.82%. Liao et al. reported low-dimensional Sn-based perovskites by using FA and PEA mixed cations (Fig. 7a), and they adjusted the orientation of the perovskite domains by altering the PEA/FA ratios [127]. A highly oriented perovskite film perpendicular to the substrate was realized by adding 20% PEA. As a result, the FASnI3 perovskite solar cells with 20% PEA achieved a maximum PCE of 5.94% with enhanced stability [127]. Recently, Yuan et al. used the bifunctional cation 5-ammoniumvaleric acid (5-AVA) as the spacer to fabricate AVA2FAn−1SnnI3n+1 (〈n〉 = 5) quasi-2D Sn-based perovskite, and by introducing appropriate amount of ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) additive, they obtained highly vertically oriented quasi-2D perovskite films which eventually enhanced the transportation of charge carriers between electrodes [128]. Actually, the Cl doping can also improve the electrical conductivity of perovskite film, as demonstrated by Li et al. [129].

Fig. 7.

a Schematic structures of mixed FA/PEA Sn perovskites with PEAI/FAI doping ratios of 0, 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100%. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [127]. b Three alternative views of the archetypal 3D perovskite structure viewed along the (100), (110), and (111) cleavage planes. c “Perovskitoid” face-sharing building block of the 1D structures obtained for t > 1 representing the archetypal hexagonal polytype. d Perovskite structures obtained through dimensional reduction featuring corner-sharing 2D sheets and 1D chains through the (100) and (110) cleavage planes, respectively. e Hexagonal perovskite polytypes obtained from a linear combination of the corner-sharing 3D perovskite along the (111) cleavage plane and the 1D face-sharing polytype. The “h” and “c” symbols indicate hexagonal and cubic layers, respectively, and serve in identifying the layer sequence that characterizes the polytype. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [135]

In recent work, Padture et al. first reported the synthesis and photovoltaic performance of low-dimensional Dion–Jacobson Sn(II)-based halide perovskites (4AMP)(FA)n−1SnnI3n+1, but the PSC based on this perovskite only achieved an efficiency of 2.15% [130]. Compared with the Sn-based perovskite of the RP layered with a van der Waals gap between the adjacent unit cells, the unique structure of DJ layered Sn-based perovskites allows the inorganic stacks to be more uniform and closer, rendering better alignment and less displacement of perovskites [131]. Moreover, the shortened interlayer distance might reduce the barrier of charge transfer, which will benefit the charge transport of derived quasi-2D perovskite devices. It is particularly worth mentioning that the growth of the DJ phase perovskite layer can be controlled by selecting different diammonium organic cations as the intermediate spacer layer so that the growth direction is perpendicular to the substrate, which facilitates the transfer and collection of charge through the electrode [124, 132]. These characteristics will make DJ Sn-based perovskites to be a promising class of materials for photovoltaic applications.

Kanatzidis et al. reported some hexagonal polytypes and low-dimensional structures of hybrid Sn iodide perovskites, which employed various small cations such as trimethylammonium (TMA+), imidazolium (IM+), guanidinium (GA+), ethylammonium (EA+), acetamidinium (ACA+), and isopropylamine (IPA+) (Fig. 7b–e) [133]. Due to the moderate size of these cations, a variety of new ASnX3 polytypes were formed by combinations of corner-sharing octahedra (perovskite) and face-sharing octahedra (perovskitoid), which have the potential for lead-free solar cells [134]. Finally, we summarize the current research results of Sn-based perovskite solar cells in Table 1 [70, 71, 80–83, 87–89, 96, 97, 101–104, 118–120, 124, 133–156].

To further improve the efficiency of tin-based perovskite, device structure manipulation was also conducted by Ning et al., who used indene-C60 bisadduct as the ETL to fabricate solar cells based on PEAxFA1−xSnI3 perovskite, yielding a high efficiency of 12.4% [135]. In addition to efficiency, the stability issue of tin-based PSCs also restrained their applications. Mathews et al. encapsulated FASnI3 PSCs and realized more stable PSCs with over 80% of its initial PCE being maintained after 1-month storage in a N2 environment, which is much better than the unencapsulated counterparts that fully decomposed within two weeks [71]. In addition, Kanatzidis et al. studied the encapsulated 2D (BA)2(MA)3Sn4I13 PSCs and their test results showed that the encapsulated device retained more than 90% of its initial performance after 1 month and dropped only to ~ 50% after 4 months in a glove box full of N2 [120]. This encouraging stability is closely related to the intrinsically stable 2D perovskite structure as well as the encapsulation that sufficiently blocked the invasion of water and oxygen. Other researchers have also proposed in their respective work that it is possible to package Sn-based solar cells to improve stability [71, 103, 104, 120, 136, 155, 156].

In summary, there is still a large room for efficiency and stability enhancements of Sn-based perovskites. Future works should focus on optimization of perovskite composition and selection of effective additives to fabricate stable and high-quality perovskite film with less Sn2+ oxidation. Besides, reasonable choice of hole/electron transport materials is very critical for enhancing device performance and stability of the Sn-based PSCs. Protecting of solar cells with industrial encapsulation techniques will also be a viable approach to improve the long-term stability of the Sn-based PSCs and push it to the commercial market.

Ge-based Perovskite

Previous reports have shown that metal ions owning external ns2 electronic structure with low ionization energy can enhance light absorption efficiency and carrier diffusion length of ABX3 structure. Ge2+ has similar outer ns2 electronic structure (4s2) to Sn2+ (5s2) and Pb2+ (6s2), but smaller ionic radii than Sn2+ and Pb2+ [64]. Ge-based perovskites containing MAGeI3, CsGeI3 and FAGeI3 have also been demonstrated to be stable at temperature of up to 150 °C. According to these data, Mathews et al. considered that Ge could replace Pb as a new type of lead-free perovskite material [64]. Actually, the bandgaps of the Ge-based perovskites can be adjusted close to the conventional lead halide perovskite of 1.5 eV via altering A-site cations.

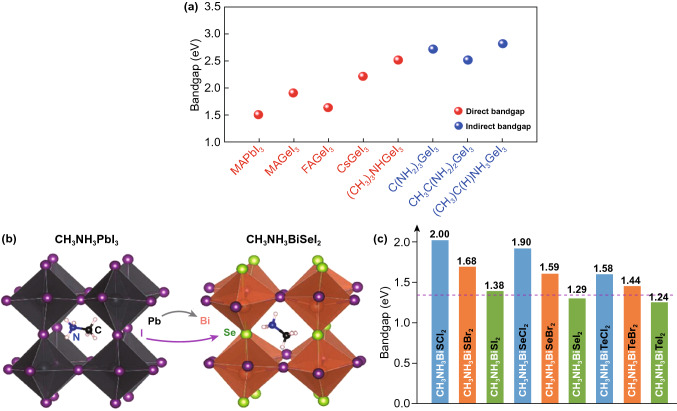

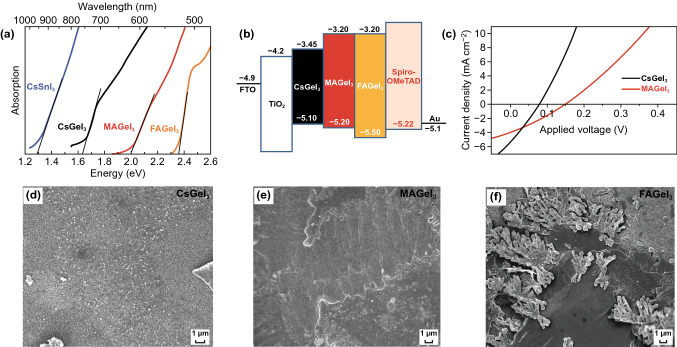

Kanatzidis et al. synthesized a series of AGeI3 perovskite compounds and characterized their structural, electronic and optical properties in 2015 [61]. The bandgaps of the Ge-based perovskites increase with the increased radius of the A cation. For instance, CsGeI3 has an optical bandgap of 1.63 eV, whereas other AGeI3 perovskites universally exhibit wide bandgap values of ≥ 2.0 eV. These AGeI3 perovskites are rhombohedral crystal structures at room temperature [60]. Kanatzidis et al. [61] used the pyramidal [GeI3]− building block to synthesize a series of Ge-based perovskites and adjusted their A-site cations. The experimental results showed that CsGeI3, MAGeI3, FAGeI3 and CH3C(NH2)2GeI3 were 3D perovskite structures with direct bandgaps of 1.6, 1.9, 2.2, and 2.5 eV, respectively, while C(NH2)3GeI3, (CH3)2C(H)NH3GeI3, and (CH3)3NHGeI3 were 1D infinite chain structures separately with indirect bandgaps of 2.7, 2.5, and 2.8 eV, among which CsGeI3 exhibited the highest optical absorption coefficient (Fig. 8a) and showed much more application potential in photovoltaic field.

Fig. 8.

a Bandgaps of various Ge-based perovskite materials compared with MAPbI3. b Atomic structures of MAPbI3 and MABiSeI2. c Calculated bandgaps of CH3NH3BiXY2 compounds (with X = S, Se, Te and Y = Cl, Br, or I) using the Heyd–Scuseria–Ernzerhof functional with spin–orbit coupling. The dashed line marks the optimal bandgap for single-junction solar cell according to the Shockley–Queisser theory. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [52]

The photoluminescence (PL) measurements of CsGeI3 single crystals exhibited two peaks at 0.82 μm (1.51 eV) and 1.15 μm (1.08 eV), which were respectively assigned to the interband transition at α. k = (π/a) (111) and the energy band change (Fig. 9a). The energy bands of the Ge-based perovskites with different A cations are shown in Fig. 9b. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy showed that the transparent range of CsGeI3 can be extended from ~ 2 to > 12 μm. The short-wave cutoff is mainly limited by the energy band, and the longest infrared transparency wavelength may originate from the phonon absorption of crystal lattice, and a specific rhombohedral crystal structure can be generated at room temperature [157]. Mathews et al. used hypophosphorous acid to improve the solubility of Ge perovskite precursor in organic solvent and prepared Ge-based perovskite films [60]. According to the SEM images (Fig. 9d–f), the films of MAGeI3 and CsGeI3 exhibited nearly full-coverage morphology, but the FAGeI3 film showed a poor quality. Based on these films, they then fabricated devices on mesoporous TiO2 structures. MAGeI3 and CsGeI3 solar cells showed Jscs of 4.0 and 5.7 mA cm−2 and PCEs of 0.11 and 0.2%, respectively, as shown in Fig. 9c. In contrast, FAGeI3 solar cell with poor film morphology displayed no photocurrent.

Fig. 9.

a Tauc plot for CsSnI3, CsGeI3, MAGeI3, and FAGeI3 showing optical bandgaps of 1.29, 1.63, 2.0, and 2.35 eV, respectively. b Energy level pattern for the PSCs with CsGeI3, MAGeI3, and FAGeI3 absorbers. c Comparison of J–V curves of CsGeI3 and MAGeI3 solar cells. d-f SEM images for CsGeI3, MAGeI3, and FAGeI3 films both deposited on the compact TiO2/mesoporous TiO2 substrates. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [60]

Kopacic et al. [158] demonstrated that chemical composition engineering of MAGeI3 significantly improved performances of solar cells and simultaneously enhanced their stability. By introducing bromide anion to partially replace idiode, the PCE based on MAGeI2.7Br0.3 was increased up to 0.57%.

Generally, Ge-based perovskites exhibit obviously different energy structures from the Pb-based ones and thus suitable ETL and HTL should be optimized to improve charge extraction efficiency in the device. More importantly, stabilization of Ge2+ in Ge-based perovskite is also a pretty challenging task to be solved. Otherwise, the stability issue and extremely low PCE will limit broader photovoltaic applications of this kind of perovskites.

Transition Metal Halide Perovskite

Divalent transition metal cations (e.g., Cu2+, Fe2+, Zn2+) have also been considered as the candidates of Pb-free perovskites, which can be synthesized via a variety of routes to tune photovoltaic properties [63, 159]. Because of small ionic radii for transition metal ions (e.g., 0.73 nm for Cu(II) and 0.78 nm for Fe(II)) that far deviated from tolerance factor of 1, 3D structure (e.g., K2NiF4) cannot be maintained and it turns into stable 2D layered structure along < 100 > , < 110 > and < 111 > orientations [160].

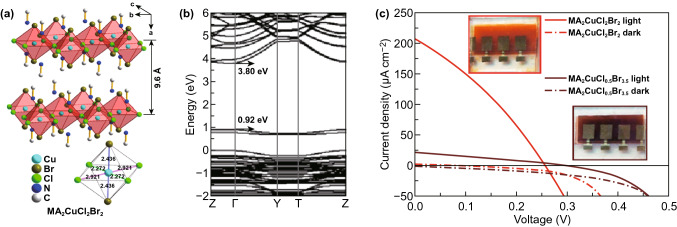

Cu2+ is a promising Pb-free perovskite in consideration of its good stability, earth abundance, low-cost and sufficient absorption in near-infrared region. Currently, some Cu-based perovskites have been developed for solar cell applications [63, 161, 162]. Cortecchia et al. first used the 2D crystal structure of MA2CuClxBr4−x (Fig. 10a) as a light absorbing layer to fabricate solar cell [63]. They mixed MABr, MACl, CuCl2 and CuBr2 in DMSO as the precursor solution and tuned the bandgaps of MA2CuClxBr4−x from 2.48 to 1.80 eV via changing the Br content (Fig. 10b). Cu-based perovskites exhibited a narrow bandgap with low conduction band compared to other non-transition metal perovskite compounds, whose conduction band is derived from the unoccupied Cu 3d orbitals hybridized with Br/Cl p orbitals. The MA2CuClxBr4−x layer was fabricated on the FTO/mesoporous TiO2 substrate by spin coating process. A PCE of 0.017% was obtained with extremely low Jsc of 216 µA cm−2 and Voc of 0.256 V (Fig. 10c). In addition, they also prepared planar heterojunction cells based on MA2CuClxBr4−x, but the PCE was far less than 0.017%. The higher PCE for mesoporous structure solar cell arises from improved charge extraction and vertical charge transport along with the destruction of the 2D structure of MA2CuClxBr4−x perovskite by mesoporous TiO2. The solar cells with MA2CuClxBr4−x as the light absorber showed better stability due to the essential role of Cl−, but unfortunately, the low absorption coefficient and heavy-mass hole limited their device performances. Subsequent works showed that (C6H5CH2NH3)2CuBr4, (ρ-FC6H5C2H4-NH3)2CuBr4 and (CH3(CH2)3NH3)2CuBr4 based solar cells had slightly higher PCEs of 0.2%, 0.51%, and 0.63% [161, 162].

Fig. 10.

a Crystal structure of MA2CuCl2Br2, showing the alternation of organic and inorganic layers and the Cu-X bond lengths in the inorganic framework. b Electronic band structure of MA2CuClBr3 investigated by DFT simulation. c J–V curve of solar cells sensitized with MA2CuCl2Br2 (red) and MA2CuCl0.5Br3.5 (brown) under 1 sun of light illumination. The red and brown dashed lines represent dark current. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [63]

On the whole, Cu-based perovskites are relatively stable compared to other transition metal perovskite materials despite of the universially low conversion efficiency. How to reduce their wide optical bandgap and improve their charge transfer rate is the bottleneck problems limiting the further development of this type of perovskites. We believe that Cu-based perovskites will be an important part of lead-free perovskite solar cells once overcoming these problems.

Lead Replacement by Heterovalent Elements

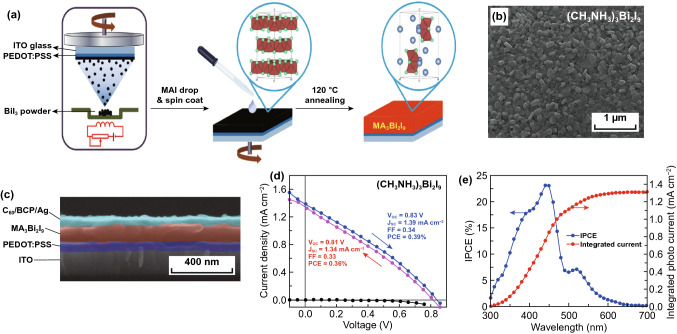

A3B2X9 Perovskite

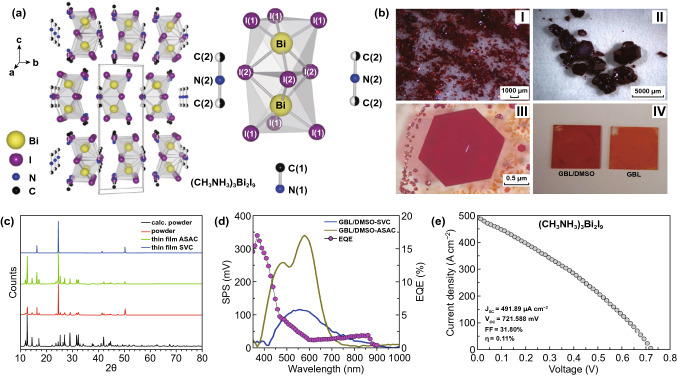

Bi-based perovskites represent a successful example in lead-free perovskite materials family with low toxicity, air stability, and a fair degree of tunability. Abulikemu et al. successfully fabricated (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9 powders, millimeter-scale single crystals and thin films with solvent-based crystallization methods (Fig. 11a, b) [163]. Compared with Pb-based counterpart, (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9 perovskite has better stability. In response to the rapid crystallization of perovskites during film formation, the researchers proposed two thin film annealing methods to improve the film-forming quality. One was an antisolvent assisted crystallization route, which dropped antisolvent of chlorobenzene during the spin coating process of precursors and then annealed at 70 °C for 10 min to form perovskite film. The other method was denominated saturated vapor crystallization. The perovskite film was fabricated without dropping chlorobenzene during the spin coating process, and then annealed in a closed Petri dish at 60 °C overnight to slow the solvent evaporation, which generated a highly oriented single-crystal film (Fig. 11b, c). Solar cell devices were fabricated based on these thin films, achieving an efficiency of 0.11%, an FF of 31.80%, an average Jsc of 491.89 μA cm−2 and a Voc of 0.7216 V (Fig. 11d, e). However, the external quantum efficiency (EQE) spectrum demonstrated that the device produced photocurrent merely at a short wavelength, with most part of the visible spectrum missed (e.g., above 500 nm) [163]. The explanation given by the researchers was that the depletion of EQE in the (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9 film was attributed to its inhomogeneity and discontinuity between crystallites in terms of high recombination of photogenerated charges, so the high-quality perovskite film is a prerequisite to achieve a high efficiency.

Fig. 11.

a A representation of the layered structure of (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9, characterized by isolated [Bi2I9]3− anions and two crystallographic inequivalent CH3NH3+ cations. b Small single-crystal powder grown from Bi2O3 and CH3NH3I in concentrated HI (I–III). And (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9 thin films deposited by the antisolvent assisted crystallization method (ASAC) using GBL/DMSO and GBL as solvents and chlorobenzene as antisolvent (IV). c Diffraction patterns of (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9 thin films, powder and simulated powder from single-crystal XRD measurements. d EQE of a typical FTO/TiO2/(CH3NH3)3Bi2I9/spiro-MeOTAD/Au device. e J–V scanning of the best-forming device. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [163]

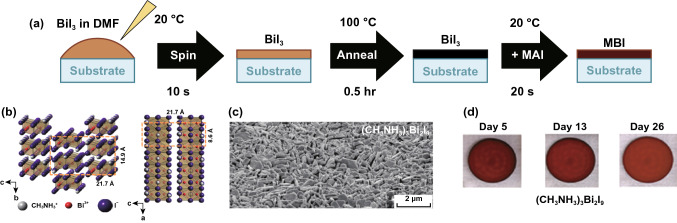

Buonassisi et al. used solution-processing and vapor-assisted techniques to synthesize pure phase (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9 perovskite (Fig. 12a) [164]. They found that the crystal structure of the pure phase (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9 was composed of alternate MA+ and Bi2I93− groups (Fig. 13b). The perovskite films prepared by this method were densely packed with high coverage and also showed excellent stability (Fig. 12c, d). The vapor processed films also got a longer PL decay time [164].

Fig. 12.

a Schematic diagram of (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9 solution-assisted process. b Crystal structure and (001) view of (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9. c SEM image of (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9 thin film. d Stability measurement of (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9 in air. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [164]

Fig. 13.

a Fabrication procedure and b SEM image of (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9 film. c Cross-sectional SEM image of (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9-based solar cells. d Forward and backward scanning and e IPCE spectra of the best-forming device. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [166]

Very recently, Zhang et al. made a breakthrough in experimental method of fabricating high-quality (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9 film [165]. They employed a novel solvent-free high–low vacuum deposition (HLVD) procedure to obtain smooth, compact and pinhole-free polygonal crystal (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9 film and then fabricated heterojunction solar cells. The HLVD approach proposed here is a two-step alternate vacuum deposition of BiI3 and MAI under high- and low-vacuum, which can be further transformed to the resultant (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9 perovskite. With the approximate 300 nm (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9 film as the light absorption layer to construct the planar heterojunction PSCs, they not only achieved a high PCE of 1.64% and a high EQE close to 60%, but also obtained a good stability during the measurement of 15 weeks, demonstrating the potential of (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9 for highly efficient and stable solar cells.

In subsequent research, Ran et al. synthesized a smooth, uniform and pinhole-free (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9 thin film with a novel two-step evaporation spin coating film fabrication strategy (Fig. 13a, b) [166]. They further optimized film formation conditions by comparing the integrated current from the IPCE measurements and formed compact (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9 thin films. By taking advantage of the optimized compact thin film, they manufactured inverted planar heterojunction photovoltaic device with a PCE of 0.39% and a high Voc of 0.83 V, which exhibited the lowest loss-in-potential to date in (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9-based solar cells (Fig. 13c–e). However, there still existed a slight hysteresis effect in the J–V curves [166]. This work certificates that the film morphology engineering is crucial for improving the optoelectronic performance of Bi-based hybrid perovskites solar cells.

Additionally, Park et al. confirmed more efficient solar cells with MA cations replaced by Cs cations in Bi-based perovskite [59]. On the basis of that research, Johansson et al. introduced a bismuth halide as the light absorber with the chemical composition of Cs3Bi2I9 in their solar cells [167]. The morphology of the Cs3Bi2I9 sample showed hexagonal flakes with size up to 2 μm, which were vertically organized and penetrated into TiO2. The TiO2 can be seen in the gaps between the large flakes due to the unique perovskite morphology and stacking mode. The best-performing device based on Cs3Bi2I9 showed a Jsc 2.2 mA cm−2, but lower Voc and FF values generated a PCE of 0.4% [167].

Although researchers have got some successful examples of Bi-based perovskites, the performances of their perovskite solar cells are still universally low due to the intrinsic large bandgaps, large carrier effective masses, large exciton binding energies, more internal defects and defect intolerance. Design of new Bi-based lead-free perovskite materials avoiding above issues on the basis of theoretical calculation is critical for further development of high-performance solar cells. In addition, accurate control of formation rate with facile process technologies (e.g., moisture assisted growth, vacuum deposition, hot spin coating, and so forth) to improve the film quality of Bi-based perovskite allows for an improved performance of Bi-based lead-free perovskite devices. Here, we summarize the current research results of Bi-based PSCs in Table 2 [59, 161, 163–170].

Table 2.

Photovoltaic parameters of PSCs based on various Bi-based perovskite absorbers

| Preparation process | Absorber | Device architecture | Voc (V) | Jsc (mA cm−2) | FF (%) | PCE (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-step spin coating | Cs3Bi2I9 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/P3HT/Ag | 0.31 | 0.34 | 38 | 0.40 | [165] |

| One-step spin coating | (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9 | c-TiO2/perovskite/spiro/Au | 0.72 | 0.49 | 31.8 | 0.11 | [161] |

| One-step spin coating | (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/spiro-MeOTAD/Au | 0.68 | 0.38 | 88 | 0.22 | [166] |

| One-step spin coating | (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/spiro-MeOTAD/Ag | 0.68 | 0.52 | 33 | 0.12 | [59] |

| One-step spin coating | Cs3Bi2I9 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/spiro-MeOTAD/Ag | 0.85 | 2.15 | 60 | 1.09 | [59] |

| One-step spin coating | (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9Clx | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/spiro-MeOTAD/Ag | 0.04 | 0.18 | 38 | 0.03 | [59] |

| One-step spin coating | (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/P3HT/Au | 0.35 | 1.157 | 46.4 | 0.19 | [167] |

| One-step spin coating | (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/PIF8-TAA/Au | 0.85 | 1.22 | 73 | 0.71 | [168] |

| Two-step evaporation spin coating | (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9 | PEDOT:PSS/perovskite/C60/BCP/Ag | 0.83 | 1.39 | 37 | 0.39 | [164] |

| Two-step thermal evaporation | (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/spiro-MeOTAD/Au | 0.83 | 3.00 | 79 | 1.64 | [163] |

| Vapor-assisted solution process | (CH3NH3)3Bi2I9 | c-TiO2/m-TiO2/perovskite/P3HT/Au | 1.01 | 4.02 | 78 | 3.17 | [169] |

| One-step spin coating | Cs3Bi2I9 | c-TiO2/perovskite/spiro-MeOTAD/Au | 0.79 | 4.45 | 50.34 | 1.77 | [170] |

| One-step spin coating | Cs3Bi2I9 | c-TiO2/perovskite/CuI/Au | 0.86 | 5.78 | 64.38 | 3.20 | [170] |

| One-step spin coating | Cs3Bi2I9 | c-TiO2/perovskite/PTAA/Au | 0.83 | 4.82 | 57.49 | 2.30 | [170] |

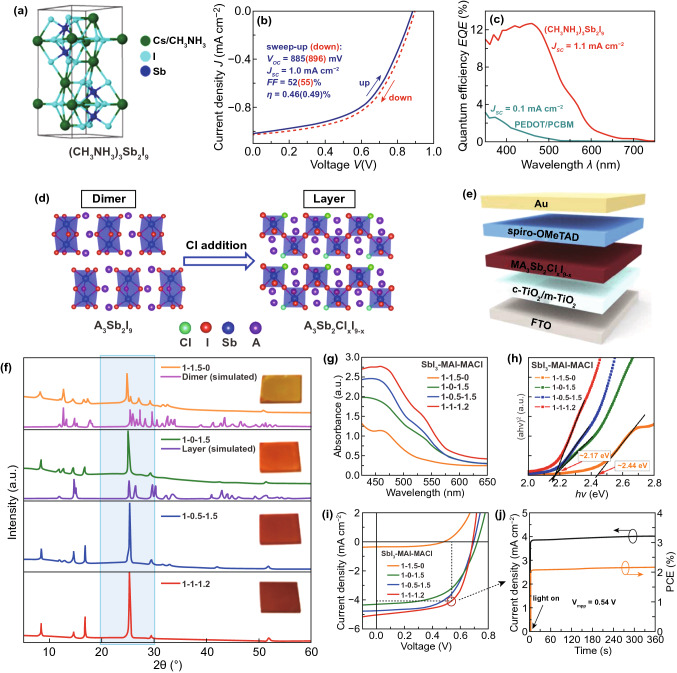

Sb is in the same element group as Bi with low toxicity although it is a heavy metal [171, 172]. Halide perovskites based on group-VA cations of Sb3+ are promising candidates due to the same lone-pair ns2 state as Pb2+. Through a joint experimental and theoretical study, researchers found that a 0D structure was formed in Sb-based perovskite, which was similar to Bi, but with lower exciton binding energies. Mitzi et al. reported a highly oriented Sb-based perovskite thin film by a two-step deposition approach. Large grain (> 1 μm) and continuous thin films of the lead-free perovskite Cs3Sb2I9 were achieved by annealing the evaporated CsI in SbI3 vapor at 300 °C for 10 min, and the 〈111〉-stacked layered perovskite structure was convinced by the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns [62]. The layered inorganic Cs3Sb2I9 has a bandgap of 2.05 eV, measured by ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy, inverse photoemission spectroscopy and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), which showed similar absorption as high as CH3NH3PbI3. The DFT calculations indicated Cs3Sb2I9 has a nearly direct bandgap in consideration of less than 0.02 eV difference between the direct and indirect bandgaps. Then Mitzi et al. prepared PSCs with the Cs3Sb2I9 material, which produced a low PCE of less than < 1%, a significant hysteresis effect, and an enhanced air stability compared to CH3NH3PbI3 counterpart [62].

Kirchartz et al. presented solution-treated trivalent antimony perovskite (CH3NH3)3Sb2I9 and fabricated a planar heterojunction solar cell with this compound (Fig. 14a–c), yielding a PCE of ~ 0.5%, a decent FF of 55%, a Voc of 0.89 V and a low photocurrent density of 1.0 mA cm−2 [173]. They determined a peak absorption coefficient (α) of ~ 105 cm−1 and an optical bandgap of 2.14 eV for amorphous (CH3NH3)3Sb2I9 films by photothermal deflection spectroscopy. The PL was observed at 1.58 eV, and the Urbach tail energy of this amorphous composite was 62 × 10−3 eV, demonstrating a substantial amount of energetic disorder [173]. The wide optical bandgap and energetic disorder may be the source of low photocurrent densities. In a word, this type of 0D dimer-phase trivalent antimony perovskite suffers from intrinsic problems including a low-symmetry induced indirect bandgap, strong quantum-confinement effect caused oversized gap values, and inferior hopping-like carrier transport, thus it is unfavorable for photovoltaic applications with extremely low PCEs of less than 0.5% obtained [62, 173].

Fig. 14.

a Crystal structure of (CH3NH3)3Sb2I9 (space group P63/mmc). b Illuminated J–V curves of (CH3NH3)3Sb2I9 solar cell measured with forward and backward scanning with a rate of 0.1 V s−1. c EQE measurement of the (CH3NH3)3Sb2I9 solar cell compared to the reference device of ITO/PEDOT/PCBM/ZnO-NP/Al. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [173] d Schematic plot of the Cl doping-induced transformation from the 0D dimer phase of A3Sb2I9 to the 2D layered phase of A3Sb2ClXI9−X. e Schematic structure of the as-fabricated PSC. f XRD patterns of the films deposited from precursors containing SbI3, MAI, and MACl with molar ratios of 1:1.5:0, 1:0:1.5, 1:0.5:1.5, and 1:1:1.2. g Measured UV–vis absorbance spectra of the four types of films. h Tauc plots of the absorption coefficients for evaluating the bandgap values of the pure-iodine perovskites MA3Sb2I9 and Cl-containing mixed-halide perovskites MA3Sb2ClXI9−X. i J–V curves for the devices fabricated with the four kinds of perovskite films. j Steady-state photocurrent output for the device based on 1-1-1.2 film at the maximum power point (red circle). Maximum power point voltage Vmpp is equal to 0.54 V. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [176]

The 2D layered phase can partially circumvent the above-mentioned problems and is expected to show a direct bandgap, smaller optical bandgap and good in-layer carrier transport properties. Recently, with the introduction of small-size Rb+ and NH4+ as the A-site cations, 2D layered phases of Rb3Sb2I9 [174] and (NH4)3Sb2I9 [175] have been realized using low-temperature solution processing. Zhou et al. performed comprehensive chemical composition engineering of the precursor solutions by incorporating MACl into the mixture of SbI3 and MAI, and successfully realized a phase transformation from the 0D dimer phase to the 2D layered one [176]. As displayed in Fig. 14d–j, the presence of the 2D layered phase was demonstrated by X-ray diffraction measurements, optical absorbance spectroscopy, and direct comparison of the experimental data with theoretical calculations. With high-quality films of the 2D layered MA3Sb2ClXI9−X perovskites as light absorbers, they fabricated solar cells with PCEs of over 2% [176].

So far, the Sb-based perovskites, similar to bismuth ones, still show a limited efficiency. But they own a bright application prospect once their nearly direct bandgap can be adjusted to a suitable value (e.g., doping) that matches with solar spectra. In addition, Sb-based perovskites can form a more stable 2D layered phase, which are better for carrier transport and display improved optoelectronic properties compared with the 0D Bi-based counterparts.

Chalcogen–Halogen Hybrid Perovskite

In 2015, Sun et al. proposed the anion-split approach based on first-principles calculation, where dual anions (e.g., halogen and chalcogen anions) were introduced while Pb was replaced by heterovalent non-toxic elements in order to keep the 3D perovskite structure and the charge neutrality (Fig. 8b, c) [52]. Figure 8b shows the atomic structure of MABiSeI2, which maintained the MAPbI3 tetragonal structure with a freely rotating MA+ ion according to ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations.

Taking Bi as the core element of the B position, Shockley et al. examined a series of MABiChX2 (Ch = S, Se, Te; X = I, Br, Cl) compounds and found that CH3NH3BiSeI2 and CH3NH3BiSI2 exhibited improved optical absorption and reduced bandgaps (1.3–1.4 eV) over CH3NH3PbI3, which were proved to be the optimal value for solar cell absorbers according to the Shockley–Queisser theory (Fig. 8c) [177]. These results suggested that the 3D AB(Ch, X)3 perovskites represented by MABiSI2 could be promising candidates of photovoltaic absorbers once they were successfully synthesized. Unfortunately, the subsequent feasibility assessment of the proposed 3D AB(Ch, X)3 perovskites by Hong et al. via DFT calculations and solid-state reactions indicated that all of the as-proposed AB(Ch, X)3 perovskites are thermodynamically unstable [34], and they tend to decompose into ternary and/or binary phases or form nonperovskite phases. Recently, the work of Li et al. has proved the instability of chalcogen–halogen hybrid perovskite through experimental and computational analysis, and they found that AB(Ch, X)3 would be decomposed into a mixture of binary and ternary compounds (Sb2S3 and MA3Sb2I9) soon after being synthesized [178]. Upon inspection, the target perovskites are impossible to be successfully synthesized as designed. Finally, the researcher had to draw a conclusion that it may be a huge challenge to synthesize the proposed AB(Ch, X)3 perovskites due to their thermodynamic instability, which means there is still a long way for AB(Ch, X)3 perovskites to go for further applications in perovskite photovoltaic devices.

0D Perovskite Derivative A2BX6

Previous analysis indicated that it is feasible to replace Pb of lead halide perovskites with tetravalent B(IV) substitutes. To accommodate the heterovalent substitute, the chemical formula needs to turn into A2BX6, which is derived from its ABX3 perovskite structure by removing half of B-site cations. Because of the large charge difference between them, the A2BX6 perovskite variant is sometimes referred to as the A2B□X6-type vacant ordered double perovskite [86, 179–181]. The B-site vacancies (denoted as □) and the remaining B-site cations generally adopt a rock salt arrangement in the A2BX6 perovskite structure. Due to the absence of connectivity between the [BX6] octahedra, the A2BX6 perovskite variants are actually 0D nonperovskites despite researchers still would like to call them perovskites. The optoelectronic properties of the A2BX6-type perovskite materials are rather different from those of 3D ABX3 (B = Pb, Sn, and Ge) perovskites due to the isolated [BX6] octahedra in A2BX6 compounds. Among the A2BX6 compounds [182–185], A2SnI6 (A = Cs, MA) [182, 183] and Cs2TiBr6 [181, 182] have been investigated for photovoltaic applications. These A2BX6 compounds show intrinsic n-type conductivity. Compared to 3D CsSnI3 with better defect tolerance, the A2BX6-type materials with I vacancies and Sn interstitial defects have deeper levels in their bandgaps owing to the strong covalent nature of the [SnI6] octahedron, seriously impacting optoelectronic performances of devices.

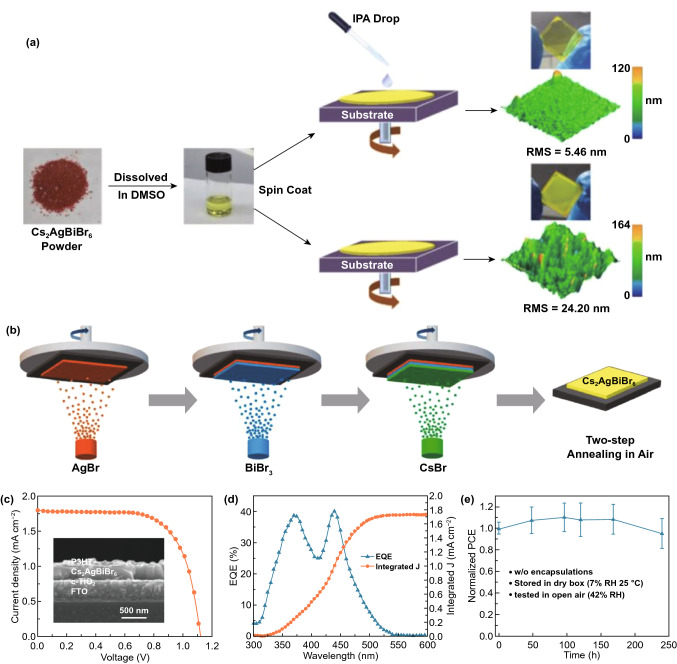

The vacancy-ordered A2M(IV)X6 double perovskites was found to have suitable direct bandgaps. In 2016, Cao et al. found the spontaneous oxidative conversion of unstable CsSnI3 to air-stable Cs2SnI6 in air [183]. The Cs2SnI6 perovskite was adopted as the light absorber layer of lead-free perovskite solar cell for the first time due to its small bandgap of 1.48 eV and high absorption coefficient, showing a PCE of about 1% with a Voc of 0.51 V and a Jsc of 5.41 mA cm−2 after optimizing the perovskite film thickness.