Abstract

Background

Clostridioides (Clostridium) difficile infection (CDI) has become an increasingly significant disease not only as healthcare-associated infection, but also as community-acquired (CA) infection worldwide. CDI caused by the NAP1/BI/027 strain is reported to be more severe, difficult to cure, and frequently associated with recurrences in North America and Europe.

Case presentation

A 68-year-old woman was referred to our hospital for continuous lower abdominal pain 4 weeks after eradication therapy against Helicobacter pylori. While she was treated with fasting on the suspicion of ischemic colitis, she experienced septic shock. Emergent subtotal proctocolectomy revealed fulminant pseudomembranous C. difficile colitis. The C. difficile isolate recovered from the patient was identified as ribotype 027, which has been reported to be uncommon in Japan.

Conclusion

We report a rare case of CA fulminant pseudomembranous colitis caused by ribotype 027 C. difficile after H. pylori eradication therapy.

Keywords: Clostridioides (Clostridium) difficile infection, Fulminant colitis, Proctocolectomy, PCR-ribotype 027, Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy, Community-acquired CDI

Background

Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) is the leading cause of healthcare-associated infectious diarrhea and, therefore, there has been continued expanding interest in the epidemiology, prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of CDI [1]. Furthermore, in recent years, community-acquired CDI have been reported [2]. National surveillance has already been carried out abroad, and there are guidelines for the prevention of CDI. On the other hands, in Japan the actual state of CDI remains unknown since there is no national data. Kato et al. reported a high CDI incidence in Japanese hospitals because of the presence of a large population with numerous risk factors for CDI, such as advanced age, widespread use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, severe comorbidities, and long hospital stays and suggested a high CDI incidence as healthcare-associated infection in Japan [3]. However, to our knowledge, there are few reports on details of community-acquired (CA) CDI in Japan.

The symptoms of CDI are highly variable from asymptomatic carriage to severe diarrhea that can progress to toxic megacolon, fulminant colitis, and septic shock. Pseudomembranous colitis is one of the manifestations of severe CDI. Severe CDI occasionally requires surgical intervention, including hemicolectomy or subtotal colectomy, in cases of fulminant diseases [4]. The severity of CDI has been reported to increase with increasing incidence during outbreaks and emergence of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) ribotype 027 epidemic strain (also known as the North American pulsed-field type 1 [NAP1] or restriction endonuclease analysis pattern “BI”) [5]. Although the ribotype 027 strain, known as a virulent strain, has caused outbreaks across North America, England, and parts of continental Europe, it has not been dominant in Asia [6]. We here report a rare case with ribotype 027 in Japan. She suffered from CA fulminant C. difficile colitis after Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication therapy and eventually required subtotal proctocolectomy.

Case presentation

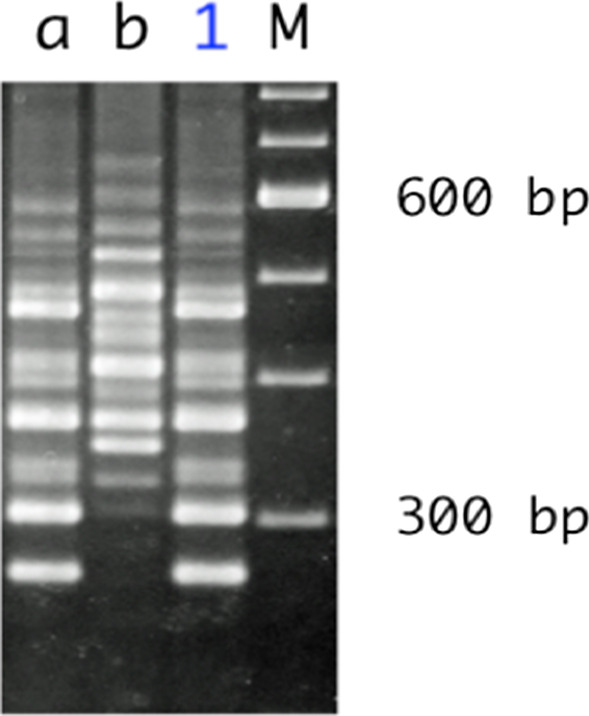

A 68-year-old woman received H. pylori eradication therapy in 2017 at a nearby medical clinic, with a potassium-competitive acid blocker (vonoprazan), amoxicillin, and clarithromycin. She had no history of other comorbidities or prior hospital admission. Four weeks after eradication therapy, she developed lower abdominal pain and revisited the clinic. A single dose of ceftriaxone was administered, but her symptoms did not improve.

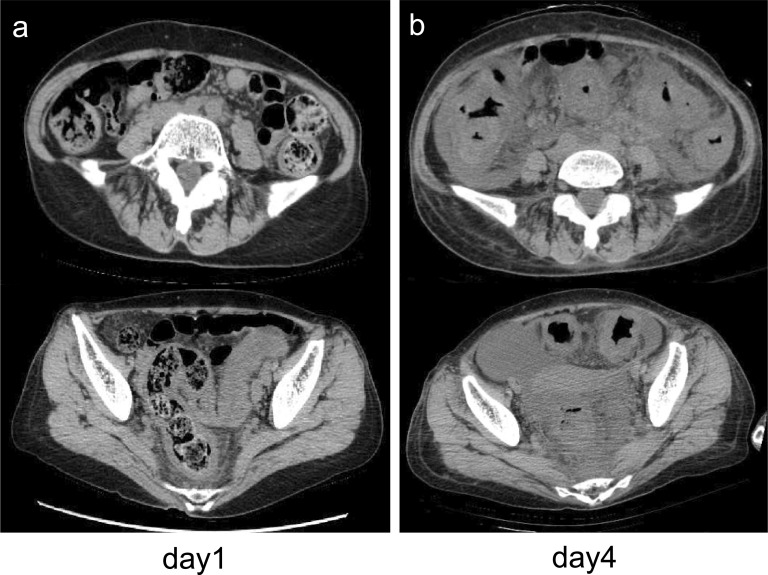

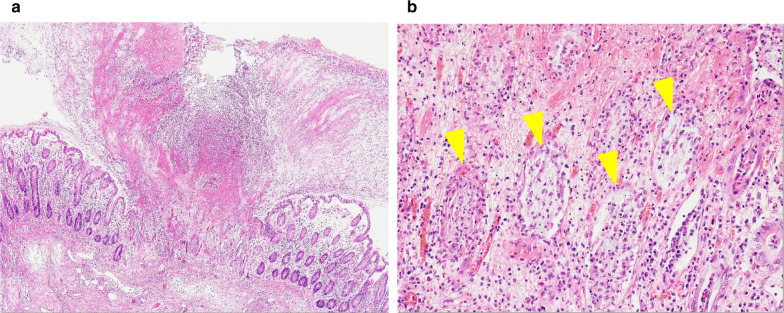

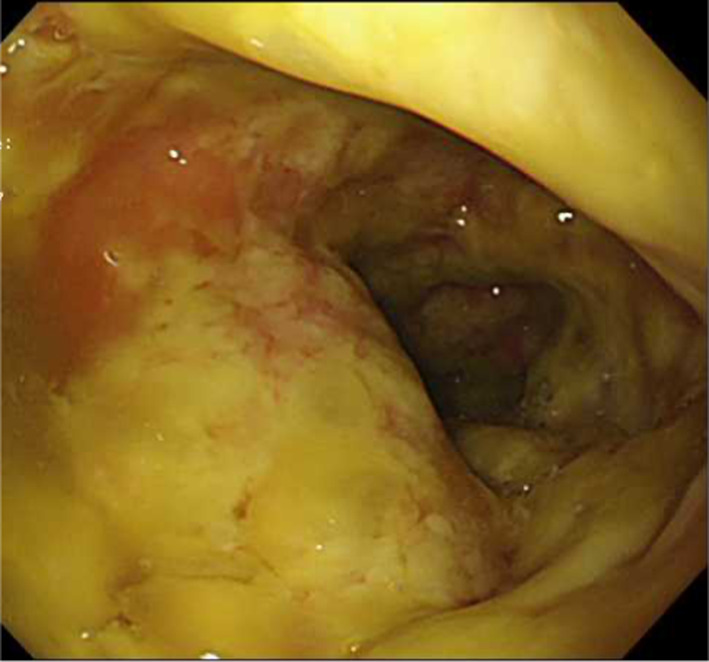

She was referred to our hospital 3 days after the administration of ceftriaxone. Her blood pressure, temperature, and heart rate were 127/65 mmHg, 37.5 °C, and 88 beats/min, respectively. She had abdominal tenderness in the left lower quadrant without muscular defense and no diarrhea. Computed tomography (CT) showed edematous thickening of the intestinal wall from the descending colon to the rectum, with increased densities of the surrounding fat tissues (Fig. 1a). Moreover, the laboratory results were as follows: white blood cell (WBC) count, 12,200/μL; hemoglobin, 11.2 g/dL; platelet (PLT) count, 18.3 × 104/μL; C-reactive protein (CRP), 2.32 mg/dL; T-bil, 0.77 IU/L; AST, 17 IU/L; ALT, 11 IU/L; BUN, 10.6 mg/dL; creatinine, 0.49 mg/dL; albumin, 3.3 g/dL; FDP, 4.0 μg/dL; and prothrombin time (PT), 13.4 s (PT-INR, 1.13). She began to have light pink mucous stool immediately after the visit and was admitted to our hospital on the suspicion of ischemic colitis. She was followed conservatively with fasting, but the abdominal pain persisted with watery diarrhea. On the third day of hospitalization, she experienced septic shock with a systolic blood pressure of 60 mmHg and temperature of 38.6 °C. The WBC count and hemoglobin and CRP levels were 26,800/μL, 11.0 g/dL, and 19.3 mg/dL, respectively. She was transferred to the intensive care unit and administered meropenem on the suspicion of bacterial enteritis. On the fourth day, the inflammatory response further worsened with a WBC count of 34,400/μL and CRP of 22.8 mg/dL. Other laboratory results were as follows: hemoglobin, 11.2 g/dL; PLT count, 20.3 × 104/μL; T-bil, 0.29 IU/L; AST, 13 IU/L; ALT, 9 IU/L; BUN, 9.7 mg/dL; creatinine, 0.51 mg/dL; albumin, 1.5 g/dL; FDP, 6.6 μg/dL; fibrinogen quantity, 389 mg/dL; and PT, 15.5 s (PT-INR, 1.31). Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) score was 2 according to criterion of the Scientific Subcommittee on DIC of the International Society for Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH). CT was repeated and demonstrated the extended wall thickening throughout the entire colon and increased ascites (Fig. 1b). Vancomycin was additionally administered intravenously as empirical treatment on the suspicion of severe enteritis. Moreover, metronidazole was intravenously administered considering the possibility of CD colitis. At this point, the physician consulted with the surgeon about the treatment strategy. Emergent sigmoidoscopy showed yellow-white purulent plaques on the mucosal surfaces of the rectum (Fig. 2). Soon after the endoscopic examination, she was intubated due to exacerbated circulatory and respiratory conditions. As colitis was judged to be severe, we decided to perform an emergency surgery. Surgical findings showed that much ascites was found in the abdomen and that the entire colon was markedly edematous and dilated with no obvious necrotic changes. Subtotal proctocolectomy from the cecum to the lower rectum was performed with ileostomy formation. After a drain tube was inserted at the pelvic bottom, the abdomen was closed. Perioperative outcomes were as follows: operation time, 250 min; loss of bleeding, 200 mL; complications, none; and length of hospital stay after surgery, 22 days. Severe pseudomembranous changes were observed on the mucosal surface of the entire colon and rectum in the resected specimen (Fig. 3). The diagnosis of pseudomembranous colitis was also supported by the typical microscopic appearances (Fig. 4). She was additionally treated with intravenous metronidazole administration (1500 mg/day) until 10 days after surgery and discharged 22 days after surgery. The enzyme immunoassay tests of the stool specimen obtained on the third day were negative for toxin A/B but positive for C. difficile glutamate dehydrogenase. It indicated that C. difficile was present but CD toxin was not detected. There were two possibilities: a non-CD toxin-producing strain or a false-negative strain due to the low sensitivity of the CD toxin test, which is actually a CD toxin-producing. Culture on the specimen with high sensitivity and specificity yielded C. difficile, which was toxin A-positive, toxin B-positive, and binary toxin-positive. The isolate was further identified as ribotype 027 (Fig. 5).

Fig. 1.

CT shows progressively worsening edematous changes in the intestinal wall and increased ascites from the first (a) to the fourth (b) hospital day

Fig. 2.

Urgent sigmoidoscopy shows widespread yellow-white purulent plaques on the surfaces of the sigmoid–rectal mucosa

Fig. 3.

The resected specimen has the highly edematous mucosa. A yellowish-white pseudomembrane is widely formed in a patchy or cohesive form on the mucosa of the entire colon and rectum

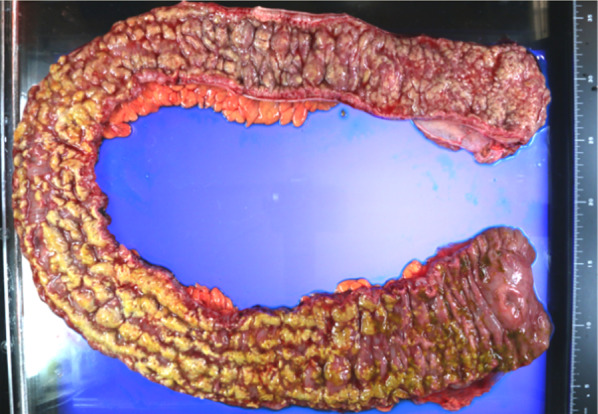

Fig. 4.

The microscopic findings. a There is a volcanic eruption image, in which the pseudomembrane component is ejected into the intestinal lumen at the mucosal defect. The pseudomembrane histologically consists of fibrin, mucus, neutrophils, and nuclear debris. b The expanded frame of the crypt remains on the mucosa of the pseudomembrane attachment site, and the dropped-out epithelial cells are seen in the lumen

Fig. 5.

PCR-ribotype pattern of the isolate recovered from the present case. Lane M, 100-bp ladder as a DNA size marker; lane 1, the isolate from our case; lane a, ribotype 027; lane b, ribotype 078

Discussion

CDIs are the leading cause of healthcare-associated diarrhea worldwide and surpass all other healthcare-associated infections in some countries [5, 6]. The incidence rates of CDI dramatically increased early in the 2000s with the emergence of the epidemic ribotype 027 strain of C. difficile. In the United States, the CDI incidence increased from 4.5/1000 adult discharges in 2001 to 8.2/1000 discharges in 2010 [7]. The death numbers per million population in the United States also increased from 8.2 in 2001 to 23.7 in 2004 [8]. After the peak of CDI before 2010, the rates of CDI have declined remarkably in England and other parts of Europe, and those in the United States have plateaued [1].

In contrast to the prevalence of ribotype 027 in North America and Europe, there have been fewer reports of CDI by ribotype 027 in Asia, where ribotypes 001, 002, 014, 017, and 018 are prevalent [9]. In Japan, the first academic reports of ribotype 027 CDI were described in 2007 [10, 11], which were followed by a few sporadic reports [12]. There have been no reports on its outbreak in Japan. The actual prevalence of ribotype 027 in Japan is difficult to determine, as ribotyping has rarely been performed clinically. Mori et al. investigated 975 stool culture samples from inpatients in a university hospital in Japan, in which 177 C. difficile isolates were recovered and 127 isolates were toxigenic and 12 were positive for the binary toxin gene. However, clinically important ribotypes such as 027 and 078 were not identified [13]. Ribotyping is very crucial for understanding the epidemiology in Japan. However, it remains unknown whether there are clinical benefits in the treatment of each case since there have been few reports of ribotype 027.

Our case may be quite rare in terms of CA infection as well as disease severity and clinical settings. Severe complications of CDI, such as megacolon, perforation, colectomy, shock requiring vasopressor therapy, and death, were reported to be associated with an age of at least 65 years, nosocomial infection, high peripheral leukocyte count, high creatinine level, initial antibiotic treatment, immunosuppression, and tube feeding [14]. Reported colectomy rates in hospitalized patients with CDI range from 0.3 to 1.3% during endemic periods and 1.8% to 6.2% during epidemic periods [15]. It is uncertain whether C. difficile ribotype 027 in Asia has similar virulence to that in North America or Europe. In the whole genomic analysis, two ribotype 027 strains isolated from two Chinese patients with CDI were outside of two distinct epidemic lineages of C. difficile ribotype 027 that emerged in North America, suggesting different features among those strains [16]. Cheng et al. summarized 19 cases of ribotype 027 in Asia, which included only two cases of fulminant CDI [17].

Although CDI is classically considered a hospital-acquired infection, CA CDI has become an increasing public health threat. Previous reports suggested that substantial fractions of CDI cases were acquired in the community [5, 18, 19]. It was reported that 40% of patients with CA CDI required hospitalization, 20% had severe infection, 4.4% had severe complications, 20% ended up with treatment failure, and 28% had recurrent CDI [20]. The sources of and risk factors for CA CDI have not been well defined [1]. An analysis of 984 patients with CA CDI during 2009–2011 showed that a substantial proportion of patients did not have possible risk factors such as antibiotic exposure (18%) and proton pump inhibitors (31%) [21]. Moreover, related academic societies have reported that H. pylori triple-therapy is associated with CDI with an incidence of approximately 1% [22]. Our case had the risk of antibiotic exposure, the most important modifiable risk factor for CDI development [1, 22] 4 weeks before onset. The duration between drug administration and CDI onset seems to be reasonable, as the highest risk of CDI (seven- to tenfold increase) was observed during antibiotic therapy and in the first month after cessation of the therapy [23]. Another possible risk factor in our case was the use of stomach-acid suppressants although its role in CDI remains controversial [1, 19].

Emergency surgery is often required for fulminant CD colitis. The reasons are refractory cases, massive bleeding, paralytic ileus, sepsis, multiple organ failure, toxic megacolon and intestinal perforation [24]. Early surgical intervention is required in treatment-refractory cases because these complications increase the fatality rate. Lee et al. examined predictors of mortality after emergency colectomy for CD colitis and listed age > 80, preoperative septic shock, preoperative severe COPD, preoperative dialysis dependence, postoperative cardiac arrest, intraoperative wound infection, PLT count (× 103/mm3) < 150, INR > 2, and BUN (mg/dL) > 40 as risk factors [25]. Therefore, our case was at high risk of mortality because she was in septic shock before surgery. According to the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines, the first-line treatment for fulminant CD enteritis is vancomycin administered orally. Moreover, if the patients become severe, subtotal colectomy with preservation of the rectum is strongly recommended [26]. Indeed, it is very important to diagnose and treat CD enteritis at an early stage, but If the condition becomes severe, immediate surgical intervention should not be hesitated.

Conclusions

We unexpectedly had a fulminant CA CDI by ribotype 027. Although there have been few reports on the epidemiology of ribotype 027 in Japan, binary toxin-positive subtype, including ribotype 027 strain, may be associated with aggravation.

Since antibiotic drugs are frequently prescribed for various medical situations including H. pylori eradication therapy, we should be aware of the risk of CDI which could lead to a severe condition even in outpatient settings.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the timely help given by Mitsutoshi Senoh, and Haru Kato (Department of Bacteriology II, National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Tokyo, Japan) in analyzing C. difficile isolates.

Abbreviations

- CDI

Clostridioides difficile infection

- H. pylori

Helicobacter pylori

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- CA

Community-acquired

- CT

Computed tomography

- WBC

White blood cell

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- PLT

Platelet

- PT

Prothrombin time

- DIC

Disseminated intravascular coagulation

Authors’ contributions

MH drafted the manuscript. RS, NT, and HF participated in treating the patients. YK, HK, and SM revised the manuscript. HK investigated this case pathologically. MH, ST, and SM were responsible for this study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for this case.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication and any accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.McDonald LC, Gerding DN, Johnson S, Bakken JS, Carroll KC, Coffin SE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:e1–e48. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jen MH, Saxena S, Bottle A, Pollok R, Holmes A, Aylin P. Assessment of administrative data for evaluating the shifting acquisition of Clostridium difficile infection in England. J Hosp Infect. 2012;80:229–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kato H, Senoh M, Honda H, Fukuda T, Tagashira Y, Horiuchi H, et al. Clostridioides (Clostridium) difficile infection burden in Japan: a multicenter prospective study. Anaerobe. 2019;60:102011. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2019.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farooq PD, Urrunaga NH, Tang DM, von Rosenvinge EC. Pseudomembranous colitis. Dis Mon. 2015;61:181–206. doi: 10.1016/j.disamonth.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freeman J, Bauer MP, Baines SD, Corver J, Fawley WN, Goorhuis B, et al. The changing epidemiology of Clostridium difficile infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:529–549. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00082-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauer MP, Notermans DW, van Benthem BH, Brazier JS, Wilcox MH, Rupnik M, ECDIS Study Group et al. Clostridium difficile infection in Europe: a hospital-based survey. Lancet. 2011;377:63–73. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61266-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zimlichman E, Henderson D, Tamir O, Franz C, Song P, Yamin CK, et al. Health care-associated infections: a meta-analysis of costs and financial impact on the US health care system. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:2039–2046. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Connor JR, Johnson S, Gerding DN. Clostridium difficile infection caused by the epidemic BI/NAP1/027 strain. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1913–1924. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fatima R, Aziz M. The hypervirulent strain of Clostridiumdifficile: NAP1/B1/027—a brief overview. Cureus. 2019;11:e3977. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kato H, Ito Y, van den Berg RJ, Kuijper EJ, Arakawa Y. First isolation of Clostridium difficile 027 in Japan. Euro Surveill. 2007;12:E070111.3. doi: 10.2807/esw.12.02.03110-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sawabe E, Kato H, Osawa K, Chida T, Tojo N, Arakawa Y, et al. Molecular analysis of Clostridium difficile at a university teaching hospital in Japan: a shift in the predominant type over a five-year period. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;26:695–703. doi: 10.1007/s10096-007-0355-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nishimura S, Kou T, Kato H, Watanabe M, Uno S, Senoh M, et al. Fulminant pseudomembranous colitis caused by Clostridium difficile PCR ribotype 027 in a healthy young woman in Japan. J Infect Chemother. 2014;20:729–731. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mori N, Yoshizawa S, Saga T, Ishii Y, Murakami H, Iwata M, et al. Incorrect diagnosis of Clostridium difficile infection in a university hospital in Japan. J Infect Chemother. 2015;21:718–722. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pépin J, Valiquette L, Alary ME, Villemure P, Pelletier A, Forget K, et al. Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in a region of Quebec from 1991 to 2003: a changing pattern of disease severity. CMAJ. 2004;171:466–472. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1041104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwon JH, Olsen MA, Dubberke ER. The morbidity, mortality, and costs associated with Clostridium difficile infection. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 2015;29:123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lv T, Chen Y, Guo L, Xu Q, Gu S, Shen P, et al. Whole genome analysis reveals new insights into the molecular characteristics of Clostridioides difficile NAP1/BI/027/ST1 clinical isolates in the People's Republic of China. Infect Drug Resist. 2019;12:1783–1794. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S203238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng JW, Xiao M, Kudinha T, Xu ZP, Hou X, Sun LY, et al. The first two Clostridium difficile ribotype 027/ST1 isolates identified in Beijing, China-an emerging problem or a neglected threat? Sci Rep. 2016;6:18834. doi: 10.1038/srep18834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khanna S, Pardi DS, Aronson SL, Kammer PP, Orenstein R, St Sauver JL, et al. The epidemiology of community-acquired Clostridium difficile infection: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:89–95. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta A, Khanna S. Community-acquired Clostridium difficile infection: an increasing public health threat. Infect Drug Resist. 2014;7:63–72. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S46780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khanna S, Pardi DS, Aronson SL, Kammer PP, Baddour LM. Outcomes in community-acquired Clostridium difficile infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:613–618. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04984.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chitnis AS, Holzbauer SM, Belflower RM, Winston LG, Bamberg WM, Lyons C, et al. Epidemiology of community-associated Clostridium difficile infection, 2009 through 2011. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1359–1367. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.7056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nei T, Hagiwara J, Takiguchi T, Yokobori S, Shiei K, Yokota H, et al. Fatal fulminant Clostridioides difficile colitis caused by Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy; a case report. J Infect Chemother. 2020;26:305–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2019.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hensgens MP, Goorhuis A, Dekkers OM, Kuijper EJ. Time interval of increased risk for Clostridium difficile infection after exposure to antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:742–748. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dallal RM, Harbercht BG, Boujoukas AJ, Sirio CA, Farkas LM, Lee KK, et al. Fulminant Clostridium difficile: an underappreciated and increasing cause of death and complication. Ann Surg. 2002;235:363–372. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200203000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee DY, Chung EL, Guend H, Whelan RL, Wedderburn RV, Rose KM. Predictors of mortality after emergency colectomy for Clostridium difficile colitis: an analysis of ACS-NSQIP. Ann Surg. 2014;259:148–156. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31828a8eba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDonald LC, Gerding DN, Johnson S, Bakken JS, Carroll KC, Coffin SE, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults and children: 2017 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:987–994. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]