Abstract

The existence of Chandrasekhar’s limit has played various decisive roles in astronomical observations for many decades. However, various recent theoretical investigations suggest that gravitational collapse of white dwarfs is withheld for arbitrarily high masses beyond Chandrasekhar’s limit if the equation of state incorporates the effect of quantum gravity via the generalized uncertainty principle. There have been a few attempts to restore the Chandrasekhar limit but they are found to be inadequate. In this paper, we rigorously resolve this problem by analysing the dynamical instability in general relativity. We confirm the existence of Chandrasekhar’s limit as well as stable mass–radius curves that behave consistently with astronomical observations. Moreover, this stability analysis suggests gravitational collapse beyond the Chandrasekhar limit signifying the possibility of compact objects denser than white dwarfs.

Keywords: white dwarf, Chandrasekhar limit, generalized uncertainty principle, dynamical instability, gravitational collapse

1. Introduction

Chandrasekhar’s limit has played a crucial role in numerous astronomical findings for many decades. It is well known that the existence of Chandrasekhar’s limit results in Type Ia supernovae (SN Ia) from the explosion of carbon–oxygen (degenerate core) white dwarfs due to accretion from a companion star. Such supernovae have well-defined light-curves with nearly the same peak brightness and their maximum brightnesses have a definite correlation with their light curve decline rates. This property makes them standard candles in astronomy, facilitating measurements on high-redshift Type Ia supernovae, and revealing the accelerated expansion of the Universe [1,2]. Importantly, this ground-breaking finding is based on the existence of Chandrasekhar’s limit.

However, it has recently been argued that the generalized uncertainty principle (GUP) removes the Chandrasekhar limit [3–6]. This is due to the fact that the inclusion of GUP,

| 1.1 |

via the equation of state gives white dwarfs of excessively high masses, irrespective of the smallness of the parameter β. In other words, the mass is no longer bound from above, so that

| 1.2 |

in the high momentum limit. This implies that the GUP-enhanced equation of state prevents gravitational collapse and halts the formation of compact astrophysical objects denser than white dwarfs. This prediction contradicts astronomical observations that confirm the existence of pulsars [7–9] and black holes [10–12]. Moreover, it has been observed that the masses of white dwarfs fall well within the Chandrasekhar limit [13–15],

| 1.3 |

apart from the super-Chandrasekhar white dwarfs, that may well be double-degenerate mergers [16–18].

A solution to the problem was proposed by imposing a cutoff in the Fermi momentum at the neutronization threshold [19]. Since the process of neutronization is not built into the dynamical equations, and it is imposed by hand, this solution is not a dynamical consequence of the theory. A more satisfying solution ought to be based on a theory where a collapse happens as a dynamical consequence of the underlying equations of the theory.

It is important to note that excessive mass of white dwarfs results when the GUP parameter β is considered to be positive. Theories of quantum gravity suggest a grainy structure of the space–time which naturally implies a minimum uncertainty in position measurement [20–24]. The minimum uncertainty in length in one of the GUP scenarios is given by as shown by Kempf [25]. Although this implies that β is a positive quantity due to Δxmin being real valued, there have been various other scenarios [26–28] which suggest that β may also be a negative quantity.

For example, a comparison between GUP corrected black hole temperature with that following from a deformed Schwarzschild metric suggested a negative value of the GUP parameter β [26,27]. The same suggestion was made [28] by a comparison between the non-commutative space–time correction to the black hole temperature with the GUP corrected black hole temperature.

However, the sign ambiguity of the GUP parameter β is still an unresolved problem. For example, on the basis of horizon quantum mechanics [29], it was suggested that β should be negative. On the other hand a corpuscular scenario of gravity, where a black hole is pictured as a Bose–Einstein condensate of gravitons, led to a positive value of β [30]. It may also be noted that a lattice model with Planckian lattice constant resulted in a negative sign for the GUP parameter β [31]. This is in contrast with a stringy scenario that leads to a positive sign for β [32,33].

A positive GUP parameter β is apparent in the thought experiment of observing an electron through a Heisenberg microscope [34]. The additional uncertainty in position of the electron due to gravitational interaction with the photon turns out to be a positive quantity, of the order of [35], implying β is positive. Similarly, a string theoretic consideration with a length scale also leads to the same additional uncertainty in position with replacing ℓP [32,33]. In addition, measurement of the radius of an extremal black hole by dropping a photon into it and by observing the re-emitted photon gives a similar (positive) estimate for the uncertainty [36–38].

Moreover, it has been shown that a negative GUP parameter β gives rise to an unphysical mass–radius relation for white dwarfs [5]. Consequently, we include the effect of quantum gravity on white dwarfs via the GUP with a positive sign for β. However, this poses the well-known problem that the Chandrasekhar limit ceases to exist. It was in fact suggested in [5] that a consistent solution of the problem could be obtained within the framework of general relativity. Since white dwarfs respect the Chandrasekhar limit, it is extremely important to solve this problem posed by GUP. A satisfactory model of white dwarfs ought to be based on a rigorous treatment of the gravitational field so that the gravitational collapse for a sufficiently massive white dwarf is well represented.

In this paper, we present a complete and rigorous approach to resolve this problem. We take the framework of general relativity (GR) and calculate the stellar structure of white dwarfs for positive GUP parameter β. We carry out a dynamical stability analysis of the equilibrium configurations so that the maximal stable configuration is identified. In this framework, we rigorously confirm the existence of Chandrasekhar’s limit within the electroweak upper bound [39] of the GUP parameter β. More precisely, we find that the Chandrasekhar limit robustly exists even when the value of β is made four orders higher than the electroweak bound.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In §2, we present the Fermionic equation of state following from GUP. In §3, we give details of the mass–radius relation in the framework of general relativity. Section 4 presents the dynamical stability analysis confirming the Chandrasekhar limit. A discussion and conclusion is presented in §5.

2. Generalized uncertainty principle and Fermionic equation of state

A minimum uncertainty in length due to the granular structure of space, which is essentially a quantum gravitational effect, can be incorporated by generalizing the Heisenberg commutation relations [25] to

| 2.1 |

These generalized commutation relations incorporate a modified high momentum behaviour via the terms containing , where cm is the Planck length. Considering a classical Liouville’s equation, it was shown [40] that the invariant measure of the phase volume takes up a factor of (1 + βp2)−3. This imposes a severe restriction on the allowed quantum states and thus modifies the thermodynamic properties with respect to the ideal case.

The inclusion of quantum gravitational fluctuations via the generalized uncertainty principle in the equation of state of a degenerate electron gas was studied earlier in different contexts [19,41–44]. In this section, we present the number density n, pressure P and energy density ɛ of the electron degenerate gas. With the modified phase volume, we employ the standard method of statistical mechanics to the relativistic electron gas assuming T = 0, yielding

| 2.2 |

and

| 2.3 |

leading to

| 2.4 |

where

| 2.5 |

and

| 2.6 |

with ξ = pF/mec, pF being the Fermi momentum, () and .

The internal kinetic energy ɛint(ξ) of the electron gas (for T = 0) is given by

| 2.7 |

In the dimensionless quantities, the above equation becomes

| 2.8 |

leading to

| 2.9 |

The rest mass density ρ0(ξ) = muμe n(ξ) is related to the energy density as ɛ(ξ) = ρ0 (ξ)c2 + ɛint(ξ), where mu = 1.6605 × 10−24 g is the atomic mass unit and μe = A/Z, with A the mass number and Z the atomic number. Thus, the energy density

| 2.10 |

where q = me/μe mu and the dimensionless energy density is given by

| 2.11 |

in the high Fermi momentum limit, that is ξ → ∞,

| 2.12 |

| 2.13 |

| 2.14 |

with

| 2.15 |

where k1, k2 and κ are constants. These high momentum limits are drastically different from the ideal case due to the role of the generalized uncertainty principle.

Moreover, the relativistic adiabatic index γ for the degenerate electron gas is obtained as

| 2.16 |

so that γ → (π/16) α3 in the limit ξ → ∞, unlike the ideal case (γideal = 4/3).

3. Mass–radius relation

We study mass–radius relation of the equilibrium configurations in the framework of general relativity in this section. For the matter interior to the star, the equilibrium values of the pressure P(r) and energy density ɛ(r) are therefore determined by the Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff (TOV) equations [45,46]

| 3.1 |

with

| 3.2 |

It may be observed that the equation of state is in a parametric form where the Fermi momentum pF of the electron degenerate gas occurs in the expressions for pressure and energy density given by equations (2.4), (2.6), (2.10) and (2.11). We express the TOV equations (3.1) and (3.2) in terms of the dimensionless quantities ξ = pF/mec, v = m/m0 and η = r/r0, where and . Thus we obtain

| 3.3 |

and

| 3.4 |

3.1. Asymptotic solutions

For a preliminary idea about the mass–radius relation, we study the asymptotic solutions of the TOV equations in the low- and high-Fermi momentum limits.

3.1.1. Low momentum limit, ξ → 0

For low values of ξ, it can be shown that equations (3.3) and (3.4) reduce to

| 3.5 |

and

| 3.6 |

which can be combined to form a second-order differential equation, given by

| 3.7 |

Defining as θ(ζ), with ξc the central dimensionless Fermi momentum, and ζ a new dimensionless coordinate, , we reduce the above equation to

| 3.8 |

which is the Lane–Emden equation of index 3/2. The numerical solution for this differential equation is given in Weinberg [47]. For the boundary conditions θ(0) = 1 and θ′(0) = 0, one can immediately obtain the radius of the white dwarf as

| 3.9 |

where ζR = 3.65375 is the first zero of the Lane–Emden function θ(ζ) of index 3/2.

Similarly, the asymptotic behaviour of the mass of the white dwarf can be obtained from the integral expression of equation (3.2), namely,

| 3.10 |

We rewrite this equation in the new dimensionless variable ζ, yielding

| 3.11 |

thus obtaining the mass of the white dwarf as

| 3.12 |

The value of is 2.71406 [47].

Thus, the above asymptotic analysis predicts that and , giving the mass–radius relation R ∼ M−1/3, implying that the radius decreases as the mass increases.

It is important to note that these expressions of mass and radius are independent of the GUP parameter α (or, equivalently, β). Thus for low mass white dwarfs the GUP has an insignificant effect on the mass–radius relation and we expect that the mass–radius curve would coincide with that of Chandrasekhar’s for low values of central Fermi momentum ξc (or, equivalently, low central density ρc).

3.1.2. High momentum limit, ξ → ∞

For high values of ξ, the TOV equations reduce to

| 3.13 |

and

| 3.14 |

Since typically α ∼ 0.1, the ratio k2/k1 ∼ (4/πα); hence the last term in the second brackets can be ignored if αξ ≫ 8/3π. Since we are looking for the solutions with ξ → ∞, we shall ignore this term, obtaining

| 3.15 |

where we have used the fact that q ∼ 10−4. The solution of the above equation is given by

| 3.16 |

Using the boundary conditions, we can immediately obtain the integration constant and hence the radius of the star as

| 3.17 |

Since 6κ/k1 ≈ 2, we have

| 3.18 |

Thus from equation (3.14) the mass becomes

| 3.19 |

As the central Fermi momentum approaches larger and larger values, we see that the radius and mass approach maximum values, given by

| 3.20 |

3.2. Exact solutions

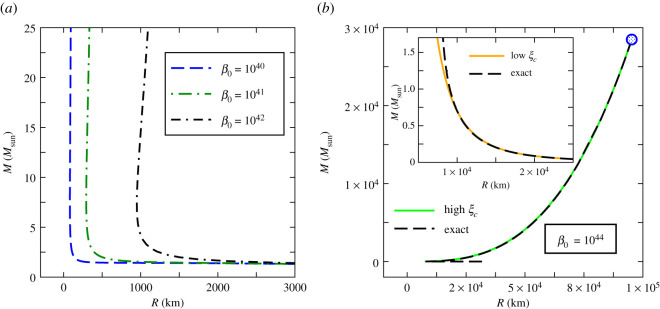

In this section, we obtain exact solutions of the TOV equations (3.3) and (3.4) employing the GUP equation of state expressed by equations (2.6) and (2.11) in parametric form. The numerical integrations are carried out with the boundary conditions ξ(0) = ξc, v(0) = 0 and ξ(ηR) = 0, where ηR denotes the dimensionless radius of the star. The resulting mass–radius relations for different strengths of the dimensionless GUP parameter β0 are shown in figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

(a) Exact mass–radius relations for white dwarfs with GUP equation of state for β0 = 1042, 1041 and 1040. (b) Exact mass–radius relations (dashed curves) for β0 = 1044 in comparison with the corresponding analytically obtained asymptotic solution (smooth curve) given by equations (3.9) and (3.12) in the high ξc limit. The open circle represents the maximum values of mass Mmax and radius Rmax. The lower left region of the exact mass–radius curve is blown up (dashed curve) in the inset where it is compared with the analytically obtained asymptotic solution in the low ξc limit (smooth curve).

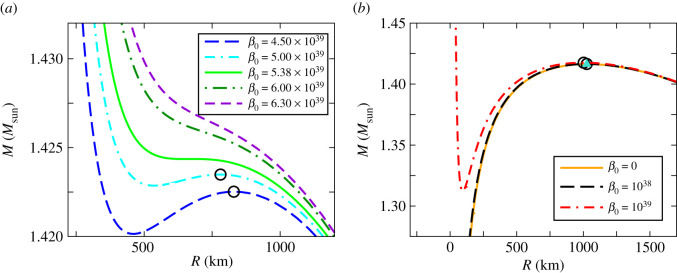

Figure 2.

(a) Exact mass–radius relations for β0 in the range 4.50 × 1039 ≤ β0 ≤ 6.30 × 1039. The mass–radius relation for demarcates these curves into two classes. For , there is no maximal point, whereas for maximal points (R*, M*) exist (shown by open circles). (b) Exact mass–radius relations for β0 = 1039 and 1038 in comparison with that of the ideal case, β0 = 0. Proximity of the maximal points (R*, M*) are shown by open circles (for β0 = 1039 and 1038) with that of the ideal case, shown as a solid triangle (β0 = 0).

It is apparent from figures 1 and 2 that, for large values of β0, the mass–radius relations given by the GUP equation of state deviate significantly from the ideal case, whereas for smaller values of β0, such deviations are smaller.

In figure 1a,b, we display the mass–radius curves for higher magnitudes of the GUP parameter such as β0 = 1044, 1042, 1041 and 1040. We see that the mass–radius curves coincide with Chandrasekhar’s curve only for low values of the central Fermi momentum ξc, as shown in the right-hand part of the inset in figure 1b. This is evident from the fact that the TOV equation reduces to Newtonian equation in the low density regime. Moreover, we see from the right-hand part of figure 1a that all curves nearly coincide irrespective of the strength of the GUP parameter β0. This is due to the fact that β0 disappears from the asymptotic equations in this regime as we have seen above in §3.1.1 in the low momentum limit.

For higher ξc values, the exact mass–radius curve reaches a point where the radius is minimum Rmin. The Rmin value is smaller for smaller β0 values as seen in figure 1a. On further increasing ξc, both the mass and radius increase reaching terminal values as shown in figure 1b denoted by an open circle. In this regime, we see that the analytically obtained high momentum solution (in §3.1.2) coincides with the exact mass–radius curve as shown in figure 1b. Moreover, the terminal values of radius Rmax and mass Mmax given by equation (3.20) are found to be nearly the same as given by the exact solutions. However, these terminal values are excessively high, as evident from figure 1b.

Exact mass–radius curves for intermediate strengths of the GUP parameter β0 (in the range 4.50 × 1039 ≤ β0 ≤ 6.30 × 1039) are shown in figure 2a. We see a cross-over in the behaviour of the curves around the value . For , the mass–radius curves do not have a maximal point, whereas for , there exist maximal points. Figure 2b compares the mass–radius relation for smaller values of β0 (=1039 and 1038) with the ideal case (β0 = 0). We see that the maxima of the mass–radius curves for these values of β0 nearly coincide with the maxima of the ideal case. It is also important to note that the maxima shifts slightly towards the right (figure 2a) as the value of β0 is decreased until the maxima coincide with the ideal value (figure 2b).

A more rigorous treatment is required to assert whether these maxima correspond to the onset of gravitational instability. Although Newtonian gravity gives the stellar structure of low-mass white dwarfs in the ideal case (with β = 0), the correct mass–radius curve and the dynamical instability for high-mass white dwarfs is determined by general relativity. Consequently, it is critical to analyse the role of the GUP parameter in determining the dynamical instability of white dwarfs. In the following section, we perform a rigorous stability analysis of the equilibrium configurations by investigating the dynamical instability in the framework of general relativity. It consists of studying the dynamics of time dependent infinitesimal radial perturbations about the equilibrium configuration at every point inside the star in a homologous manner [48]. The time evolution of these perturbations determined by the central Fermi momentum ξc and the GUP parameter β0 establishes whether the system is stable or otherwise.

4. Dynamical stability analysis

As we have already noted, dynamical stability analysis consists of the investigation of the time evolution of homologous infinitesimal perturbations about the equilibrium configuration [48–51]. The corresponding metric interior to the star is expressed as

| 4.1 |

where ν(r) and μ(r) are the equilibrium metric potentials and the perturbations δν(r, t) and δμ(r, t) are due to small radial Lagrangian displacements ζ(r, t). This induces perturbations δP(r, t) and δɛ(r, t) to the equilibrium pressure P(r) and energy density ɛ(r). The smallness of the perturbation allows one to consider sinusoidal displacements ζ(r, t) = r−2 eν/2ψ(r) eiωt. The corresponding equation for the radial oscillation can be obtained in the Strum–Liouville form [52]

| 4.2 |

satisfying the boundary conditions ψ = 0 at r = 0 and the Lagrangian change in pressure δP = −eν/2(γP/r2) dψ/dr = 0 at r = R. In the above equation,

| 4.3 |

| 4.4 |

| 4.5 |

with the adiabatic index γ, given by

| 4.6 |

Integrating equation (4.2) upon left-multiplying by ψ, one obtains the integral

| 4.7 |

where ψ′ = dψ/dr, and the boundary conditions eliminate the surface term. It can be shown that equation (4.2) is reproduced from the variational principle δJ[ψ] = 0. Thus, the lowest characteristic eigenfrequency of the normal mode is obtained from

| 4.8 |

The star remains in stable equilibrium so long as this equation yields positive values for . On the other hand, a negative signifies unstable equilibrium. A power series solution of equation (4.2) about r = 0 gives ψ(r) ∝ r3 in the leading order for which ζ(r) and ζ′(r) are finite. A good approximation for the trial function of the fundamental mode can be taken as the simple form ψ(r) = c0r3 [48,49,53]. With this choice, the onset of instability, hence the critical density for gravitational collapse, can be identified with a zero eigenfrequency solution of equation (4.8).

For the matter interior to the star, the equilibrium values of the pressure P(r) and energy density ɛ(r) are determined by the Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff (TOV) equations (3.1) and (3.2) and the interior Schwarzschild metric potentials satisfying Einstein’s field equations are given by [45,46]

| 4.9 |

and

| 4.10 |

4.1. Eigenfrequency of the fundamental mode

The interior Schwarzschild metric potentials can be written in the dimensionless variables as

| 4.11 |

and

| 4.12 |

where the expression for eν is obtained from the equation of state given by equations (2.6) and (2.11).

The solution of the TOV equations (3.3) and (3.4), and equations (4.11) and (4.12) give all quantities necessary for the evaluation of the functions U(r), V(r) and W(r) in equations (4.3)–(4.5). We may rewrite equation (4.8) in dimensionless form as

| 4.13 |

where

| 4.14 |

| 4.15 |

| 4.16 |

We thus numerically evaluate the integrals in equations (4.14)–(4.16) with the trial function ψ = c0η3, with c0 a disposable constant, for different choices of the GUP parameter β0. Consequently, we obtain the eigenfrequency of the fundamental mode from equation (4.13). As stated earlier, stable configurations correspond to positive values of , whereas a zero frequency solution indicates the onset of a dynamical instability signifying the onset of a gravitational collapse.

We display the results of the numerical integrations in figure 3, where the eigenfrequency is plotted with respect to the central density ρc (=ɛc/c2) for different values of β0. For low mass white dwarfs with central densities , we observe that the pulsation frequencies overlap signifying the irrelevance of the effect of GUP in this range of central densities. The pulsation frequencies start to deviate from each other in the higher density regime depending on the value of β0.

Figure 3.

Eigenfrequency of the fundamental mode against central density ρc for various values of the GUP parameter β0.

For , there exist zero eigenfrequency solutions at central densities , suggesting the onset of gravitational collapse. The existence of imaginary eigenfrequency solution corresponding to unstable configuration is possible only for . For , zero eigenfrequency solutions are not possible even for arbitrarily high central densities ρc, signifying stability of excessively massive white dwarfs. We also see that the curve for β0 = 1038 nearly coincides with that for the ideal case (β0 = 0). This means that all curves in the range 0 ≤ β0 ≤ 1038 overlap (to a good approximation) giving rise to approximately the same onset density for gravitational collapse. A legitimate upper bound is given by the electroweak limit β0 ∼ 1034 [39] which is well within the range 0 ≤ β0 ≤ 1038. Since this onset density is nearly 2.3588 × 1010 g cm−3, Chandrasekhar’s general relativistic mass ∼1.42 M is easily recovered in this range which extends four orders of magnitude beyond the electroweak bound.

The above discussions lead to parallel observations from figure 2a where demarcates a change in behaviour of the mass–radius curves. The non-existence of a maximal point in the mass–radius curve for is evident from the fact that there exists no critical density corresponding to a zero eigenfrequency solution. On the other hand, for , the existence of maximal points (R*, M*) in the mass–radius curves are consequences of the zero eigenfrequency solutions at . The branches towards the right of the maximal point (R*, M*) correspond to lower central densities and thus the stability of this branch is confirmed by the fact that is positive, as shown in figure 3. On the other hand, the branches towards the left of the maximal point (R*, M*) correspond to instability as becomes negative (not shown in figure 3) and they correspond to .

As β0 is deceased towards 1038, the maximal points (R*, M*) approach closer to each other and nearly coincide at β0 = 1038. The corresponding critical values are displayed in table 1 where it is evident that the critical mass approaches the limit 1.416 M and the radius 1024 km.

Table 1.

Critical values of the central density , mass M*, and radius R* for different values of the GUP parameter β0 at the onset of dynamical instability determined by the vanishing eigenfrequency of the fundamental mode.

| β0 | R* (km) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 5.38 × 1039 | 1.0105 × 1011 | 1.4244 | 655.5629 |

| 5.00 × 1039 | 5.8618 × 1010 | 1.4235 | 776.3669 |

| 1.00 × 1038 | 2.3801 × 1010 | 1.4165 | 1021.6162 |

| 1.00 × 1034 | 2.3588 × 1010 | 1.4164 | 1024.3821 |

Thus in addition to asserting the existence of the Chandrasekhar limit, the stability analysis confirms the fact that the radius decreases as the mass increases for stable configurations of white dwarfs.

5. Discussion and conclusion

There have been a few recent attempts to restore the Chandrasekhar limit when white dwarfs are described by GUP-enhanced equation of state. As we have discussed earlier, there are various scenarios [26–28] pointing to the possibility of β being negative. As shown in [5], a choice of a negative GUP parameter β gives rise to the mass–radius relation

| 5.1 |

in the relativistic limit, giving the Chandrasekhar mass MCh as an upper bound. However, this mass–radius relation has inconsistencies with observations, namely, (i) as the mass M increases, the radius R also increases, and (ii) the radius diverges as the mass approaches the Chandrasekhar limit, preventing the formation of more compact objects as the density would be infinitely diluted. In fact, observations indicate that the radius decreases with the increase in mass of white dwarfs. Moreover, we expect the formation of highly dense objects such as neutron stars or black holes when the mass exceeds the Chandrasekhar limit. These inconsistencies do not appear when we take β to be a positive quantity.

In an alternative approach to circumvent the problem of non-existence of the Chandrasekhar mass, an extended GUP [6] was suggested by incorporating the effect of cosmological constant , so that

| 5.2 |

with which is positive for de-Sitter expansion of the Universe (λ = +3). Although the observed value of is very small, namely m−2, they showed that this reformulation of GUP leads to a mass–radius relation whose physically acceptable solution is strongly dominated by the cosmological terms and the contribution from β is insignificant, making the sign of β irrelevant. This mass–radius relation clearly shows that the Chandrasekhar mass is the upper bound. However, this mass–radius relation also suffers from the same inconsistencies as described above.

Because of these inconsistencies, it is essential to resolve the issue of non-existence of Chandrasekhar’s limit in a cogent fashion so that all assumptions in the theory lead to results in agreement with observations. We therefore formulated the problem in a rigorous manner by adopting general relativity vis-à-vis GUP-enhanced equation of state with the assumption of a positive GUP parameter β. Importantly, we find that the Chandrasekhar mass is assured for β0 values below , due to the onset of gravitational collapse. We also note that the electroweak upper bound for β0 is much below so that physical existence of Chandrasekhar’s limit is guaranteed.

The above conclusion stems from a rigorous stability analysis of the equilibrium configurations as displayed in figure 3, where the eigenfrequency of the fundamental mode is plotted with respect to the central density ρc for different values of β0. We see that a vanishing eigenfrequency exists when , giving rise to a dynamical instability at critical central densities . However, for , no dynamical instability occurs because of the nonexistence of a zero eigenfrequency solution, implying that these configurations remain stable for arbitrarily high values of ρc leading to excessively massive white dwarfs. However, these solutions are physically unacceptable because the corresponding β0 values are well above the electroweak bound.

An important point to observe from figure 3 is that the eigenfrequencies for β0 = 1038 practically coincide with those of the ideal case, β0 = 0. Thus in the range 0 < β0 < 1038, the critical density for the onset of gravitational collapse (determined by the vanishing eigenfrequency) remains practically unaltered. We find g cm−3 for β0 = 1038, which is nearly the same as Chandrasekhar’s critical value of 2.3 × 1010 g cm−3 (for β0 = 0). It is thus evident that Chandrasekhar’s general relativistic critical mass of 1.42 M [50] remains practically unaffected. Moreover, since this critical density is much below nuclear matter density, approximately 1014 g cm−3, our consideration of a free fermionic equation of state remains valid throughout the stable regime of white dwarfs.

In the context of the stability analysis, we can analyse the mass–radius curve obtained in §3. Since the Chandrasekhar limit exists only below , all mass–radius plots in figure 1 above this value would not correspond to reality. This is also evident from the fact that is much higher than the electroweak bound β0 ∼ 1034. For , the mass–radius curves develop maximal points (figure 2a) at which the eigenfrequencies vanish as shown later in §4. These maximal points correspond to limiting Chandrasekhar mass lying below . It is important to note that the radius decreases as the mass increases in the part of a mass–radius curve towards the right of the maximal point that corresponds to the stable branch. The mass–radius behaviour in the stable branches is consistent with several astronomical observations of white dwarfs [13–15,54–58]. Moreover, our stability analysis suggests that upon reaching beyond the Chandrasekhar mass the star would collapse to form highly dense compact objects such as a neutron star or black hole.

The present scenario of describing white dwarfs in terms of general relativity and GUP-enhanced equation of state with a positive GUP parameter β rigorously leads to the existence of Chandrasekhar mass as well as the correct behaviour of the mass–radius relation consistent with astronomical observations. Moreover, it suggests the onset of gravitational collapse beyond the Chandrasekhar mass. It is now well-known that the degenerate core of a Type II supernova progenitor undergoes a gravitational collapse with a mass of about , leading to the formation of a neutron star or a black hole.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

A.M. is indebted to the Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati for extending various facilities of the Institute during his doctoral programme. M.K.N. thankfully acknowledges financial support from the Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati.

Data accessibility

Numerical code and data to replicate the findings of this study are available within Dryad (https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.dncjsxkzt) and published at Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4625488) DOI: 10.5061/dryad.dncjsxkzt [59].

Authors' contributions

A.M. carried out this work with the supervision of M.K.N.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Funding

This research article is supported by funding from the Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati, India.

References

- 1.Perlmutter S et al. 1999. Measurements of and from 42 high-redshift supernovae. Astrophys. J. 517, 565. ( 10.1086/307221) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riess AG et al. 1998. Observational evidence from supernovae for an accelerating universe and a cosmological constant. Astrophys. J. 116, 1009. ( 10.1086/300499) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rashidi R. 2016. Generalized uncertainty principle and the maximum mass of ideal white dwarfs. Ann. Phys. (N.Y.) 374, 434-443. ( 10.1016/j.aop.2016.09.005) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moussa M. 2015. Effect of generalized uncertainty principle on main-sequence stars and white dwarfs. Adv. High Energy Phys. 2015, 9. ( 10.1155/2015/343284) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ong YC. 2018. Generalized uncertainty principle, black holes, and white dwarfs: a tale of two infinities. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys 2018, 015. ( 10.1088/1475-7516/2018/09/015) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ong YC, Yao Y. 2018. Generalized uncertainty principle and white dwarfs redux: how the cosmological constant protects the Chandrasekhar limit. Phys. Rev. D 98, 126018. ( 10.1103/PhysRevD.98.126018) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hewish A, Bell SJ, Pilkington JDH, Scott PF, Collins RA. 1968. Observation of a rapidly pulsating radio source. Nature 217, 709-713. ( 10.1038/217709a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mignani RP, Zharikov S, Caraveo PA. 2007. The optical spectrum of the Vela pulsar. Astron. Astrophys. 473, 891-896. ( 10.1051/0004-6361:20077774) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cromartie HT et al. 2020. Relativistic Shapiro delay measurements of an extremely massive millisecond pulsar. Nat. Astron. 4, 72-76. ( 10.1038/s41550-019-0880-2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burke MJ et al. 2012. A transient sub-Eddington black Hole X-ray binary candidate in the dust lanes of centaurus A. Astrophys. J. 749, 112. ( 10.1088/0004-637X/749/2/112) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walsh JL, Barth AJ, Ho LC, Sarzi M. 2013. The M87 black hole mass from gas-dynamical models of space telescope imaging spectrograph observations. Astrophys. J. 770, 86. ( 10.1088/0004-637X/770/2/86) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu J et al. 2019. A wide star-black-hole binary system from radial-velocity measurements. Nature 575, 618-621. ( 10.1038/s41586-019-1766-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shipman HL. 1972. Masses and radii of white dwarfs. Astrophys. J. 177, 723. ( 10.1086/151752) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shipman HL. 1979. Masses and radii of white-dwarf stars. III - Results for 110 hydrogen-rich and 28 helium-rich stars. Astrophys. J. 228, 240. ( 10.1086/156841) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kilic M, Prieto CA, Brown WR, Koester D. 2007. The lowest mass white dwarf. Astrophys. J. 660, 1451. ( 10.1086/514327) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hicken M, Garnavich PM, Prieto JL, Blondin S, DePoy DL, Kirshner RP, Parrent J. 2007. The luminous and carbon-rich supernova 2006gz: a double degenerate merger? Astrophys. J. Lett. 669, L17. ( 10.1086/523301) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silverman JM, Ganeshalingam M, Li W, Filippenko AV, Miller AA, Poznanski D. 2011. Fourteen months of observations of the possible super-Chandrasekhar mass Type Ia Supernova 2009dc. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 410, 585-611. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2010.17474.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Kerkwijk MH. 2013. Merging white dwarfs and thermonuclear supernovae. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 371, 20120236. ( 10.1098/rsta.2012.0236) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mathew A, Nandy MK. 2018. Effect of minimal length uncertainty on the mass-radius relation of white dwarfs. Ann. Phys. (N.Y.) 393, 184-205. ( 10.1016/j.aop.2018.04.008) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Padmanabhan T. 1985. Planck length as the lower bound to all physical length scales. Gen. Rel. Gravit. 17, 215-221. ( 10.1007/BF00760244) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Padmanabhan T. 1985. Physical significance of Planck length. Annu. Phys. (N.Y.) 165, 38-58. ( 10.1016/S0003-4916(85)80004-X) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Padmanabhan T. 1986. The role of general relativity in the uncertainty principle. Class. Quantum Grav. 3, 911. ( 10.1088/0264-9381/3/5/020) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Padmanabhan T. 1987. Limitations on the operational definition of spacetime events and quantum gravity. Class. Quantum Grav. 4, L107. ( 10.1088/0264-9381/4/4/007) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greensite J. 1991. Is there a minimum length in D = 4 lattice quantum gravity? Phys. Lett. B 255, 375-380. ( 10.1016/0370-2693(91)90781-K) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kempf A, Mangano G, Mann RB. 1995. Hilbert space representation of the minimal length uncertainty relation. Phys. Rev. D 52, 1108-1118. ( 10.1103/PhysRevD.52.1108) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scardigli F, Casadio R. 2015. Gravitational tests of the generalized uncertainty principle. Eur. Phys. J. C 75, 425. ( 10.1140/epjc/s10052-015-3635-y) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scardigli F. 2019. The deformation parameter of the generalized uncertainty principle. J. Phys: Conf. Ser. 1275, 012004. ( 10.1088/1742-6596/1275/1/012004) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kanazawa T, Lambiase G, Vilasi G, Yoshioka A. 2019. Noncommutative Schwarzschild geometry and generalized uncertainty principle. Eur. Phys. J. C 79, 95. ( 10.1140/epjc/s10052-019-6610-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Casadio R, Giugno A, Giusti A. 2017. Global and local horizon quantum mechanics. Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 49, 32. ( 10.1007/s10714-017-2198-7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buoninfante L, Luciano GG, Petruzziello L. 2019. Generalized uncertainty principle and corpuscular gravity. Eur. Phys. J. C 79, 663. ( 10.1140/epjc/s10052-019-7164-y) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jizba P, Kleinert H, Scardigli F. 2010. Uncertainty relation on a world crystal and its applications to micro black holes. Phys. Rev. D 81, 084030. ( 10.1103/PhysRevD.81.084030) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amati D, Ciafaloni M, Veneziano G. 1989. Can spacetime be probed below the string size? Phys. Lett. B 216, 41-47. ( 10.1016/0370-2693(89)91366-X) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Konishi K, Paffuti G, Provero P. 1990. Minimum physical length and the generalized uncertainty principle in string theory. Phys. Lett. B 234, 276-284. ( 10.1016/0370-2693(90)91927-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mead CA. 1964. Possible connection between gravitation and fundamental length. Phys. Rev. B 135, 849-862. ( 10.1103/PhysRev.135.B849) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adler RJ, Santiago DI. 1999. On gravity and the uncertainty principle. Mod. Phys. Lett. A 14, 1371-1381. ( 10.1142/S0217732399001462) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maggiore M. 1993. A generalized uncertainty principle in quantum gravity. Phys. Lett. B 304, 65-69. ( 10.1016/0370-2693(93)91401-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maggiore M. 1994. Quantum groups, gravity, and the generalized uncertainty principle. Phys. Rev. D 49, 5182-5187. ( 10.1103/PhysRevD.49.5182) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garay LJ. 1995. Quantum gravity and minimum length. Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 10, 145-165. ( 10.1142/S0217751X95000085) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Das S, Vagenas EC. 2008. Universality of quantum gravity corrections. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 221301. ( 10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.221301) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chang LN, Minic D, Okamura N, Takeuchi T. 2002. Effect of the minimal length uncertainty relation on the density of states and the cosmological constant problem. Phys. Rev. D 65, 125028. ( 10.1103/PhysRevD.65.125028) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang P, Yang H, Zhang X. 2010. Quantum gravity effects on statistics and compact star configurations. J. High Energy Phys. 8, 43. ( 10.1007/JHEP08(2010)043) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang XM, Sun JX, Yang L. 2014. Effect of the minimal length on the thermodynamics of ultra-relativistic ideal fermi gas. Chin. Phys. Lett. 31, 047301. ( 10.1088/0256-307X/31/4/047301) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moussa M. 2014. Quantum gases and white dwarfs with quantum gravity. J. Stat. Mech: Theory Exp. 2014, P11034. ( 10.1088/1742-5468/2014/11/P11034) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nozari K, Fazlpour B. 2006. Generalized uncertainty principle, modified dispersion relations and the early universe thermodynamics. Gen. Rel. Grav. 38, 1661-1679. ( 10.1007/s10714-006-0331-0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tolman RC. 1939. Static solutions of Einstein’s field equations for spheres of fluid. Phys. Rev. 55, 364-373. ( 10.1103/PhysRev.55.364) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oppenheimer JR, Volkoff GM. 1939. On massive neutron cores. Phys. Rev. 55, 374-381. ( 10.1103/PhysRev.55.374) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weinberg S. 1972. Gravitation and cosmology: principles and applications of the general theory of relativity. New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chandrasekhar S. 1964. The dynamical instability of gaseous masses approaching the Schwarzschild limit in general relativity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 12, 114. ( 10.1103/PhysRevLett.12.114) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chandrasekhar S. 1964. The dynamical instability of gaseous masses approaching the Schwarzschild limit in general relativity. Astrophys. J. 140, 417. ( 10.1086/147938) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chandrasekhar S, Tooper RF. 1964. The dynamical instability of white-dwarf configurations approaching the limiting mass. Astrophys. J. 139, 1396. ( 10.1086/147883) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mathew A, Nandy MK. 2020. Prospect of Chandrasekhar’s limit against modified dispersion relation. Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 52, 38. ( 10.1007/s10714-020-02686-y) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bardeen JM, Thorne KS, Meltzer DW. 1966. A catalogue of methods for studying the normal modes of radial pulsation of general-relativistic stellar models. Astrophys. J. 145, 505. ( 10.1086/148791) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wheeler JC, Hansen CJ, Cox JP. 1968. General relativistic instability in white dwarfs. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2, 253. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vennes S, Thejll PA, Galvan RG, Dupuis J. 1997. Hot white dwarfs in the extreme ultraviolet explorer survey. II. Mass distribution, space density, and population age. Astrophys. J. 480, 714. ( 10.1086/303981) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vennes S. 1999. Properties of hot white dwarfs in extreme-ultraviolet/soft X-ray surveys. Astrophys. J. 525, 995. ( 10.1086/307949) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marsh MC, Barstow MA, Buckley DA, Burleigh MR, Holberg JB, Koester D, O’Donoghue D, Penny AJ, Sansom AE. 1997. An EUV-selected sample of DA white dwarfs from the ROSAT All-Sky Survey–I. Optically derived stellar parameters. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 286, 369-383. ( 10.1093/mnras/286.2.369) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kepler SO, Kleinman SJ, Nitta A, Koester D, Castanheira BG, Giovannini O, Costa AFM, Althaus L. 2007. White dwarf mass distribution in the SDSS. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 375, 1315-1324. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.11388.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shipman HL. 1977. Masses, radii, and model atmospheres for cool white-dwarf stars. Astrophys. J. 213, 138. ( 10.1086/155138) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mathew A, Nandy MK. 2021. Numerical code and data for the stellar structure and dynamical instability analysis of generalised uncertainty white dwarfs. Dryad, Dataset. ( 10.5061/dryad.dncjsxkzt) [DOI]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Mathew A, Nandy MK. 2021. Numerical code and data for the stellar structure and dynamical instability analysis of generalised uncertainty white dwarfs. Dryad, Dataset. ( 10.5061/dryad.dncjsxkzt) [DOI]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Numerical code and data to replicate the findings of this study are available within Dryad (https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.dncjsxkzt) and published at Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4625488) DOI: 10.5061/dryad.dncjsxkzt [59].