Abstract

BACKGROUND

The dynamic monitoring of immune status is crucial to the precise and individualized treatment of sepsis. In this study, we aim to introduce a model to describe and monitor the immune status of sepsis and to explore its prognostic value.

METHODS

A prospective observational study was carried out in Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, enrolling septic patients admitted between July 2016 and December 2018. Blood samples were collected at days 1 and 3. Serum cytokine levels (e.g., tumor necrosis factor-α [TNF-α], interleukin-10 [IL-10]) and CD14+ monocyte human leukocyte antigen-D-related (HLA-DR) expression were measured to serve as immune markers. Classification of each immune status, namely systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), compensatory anti-inflammatory response syndrome (CARS), and mixed antagonistic response syndrome (MARS), was defined based on levels of immune markers. Changes of immune status were classified into four groups which were stabilization (SB), deterioration (DT), remission (RM), and non-remission (NR).

RESULTS

A total of 174 septic patients were enrolled including 50 non-survivors. Multivariate analysis discovered that IL-10 and HLA-DR expression levels at day 3 were independent prognostic factors. Patients with MARS had the highest mortality rate. Immune status of 46.1% patients changed from day 1 to day 3. Among four groups of immune status changes, DT had the highest mortality rate, followed by NR, RM, and SB with mortality rates of 64.7%, 42.9%, and 11.2%, respectively.

CONCLUSIONS

Severe immune disorder defined as MARS or deterioration of immune status defined as DT lead to the worst outcomes. The preliminary model of the classification and dynamic monitoring of immune status based on immune markers has prognostic values and is worthy of further investigation.

Keywords: Infectious disease, Immune dysfunction, Immune status classification, Cytokine

INTRODUCTION

Sepsis is defined as a dysregulated host response to infection or other injury factors.[1,2] The incidence and prevalence of sepsis have increased over recent years, so sepsis accounts for a considerable number of intensive care unit (ICU) admissions and mortality.[3] Notably, immune dysfunction and damage to organ function add to the difficulty of disease management and influence the prognosis.[4,5]

The inflammatory activities of sepsis involve interactions between various inflammatory mediators. The early phase of sepsis features an activated inflammatory process caused by the systemic release of proinflammatory mediators.[6] Sepsis can also lead to the apoptosis and autophagy of immune cells, endotoxin tolerance, and relevant central nervous system regulation, which consequently present as immunosuppression.[7] Immunosuppression is more often observed in severe patients as a result of an imbalance between pro- and anti-inflammatory activities.[6]

To describe the complex inflammatory process of sepsis, some definitions of immune status classifications have been introduced in recent years. The process of sepsis features an initial systemic inflammation process called systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). Anti-inflammatory activities may happen subsequently or concurrently, which is called compensatory anti-inflammatory response syndrome (CARS).[8] An excessive response with both pro- and anti-inflammatory reactions called mixed antagonistic response syndrome (MARS) is found in some patients with severely dysfunctional immunomodulation.[9-11] Immunomodulatory therapy has been a research focus for the treatment of sepsis, and the changing immune status and lack of specific clinical signs have held back the proper application of the therapy. It was suggested that the precise identification of the patient’s immune status would be the first step to provide appropriate immune therapies.[12,13]

Serum cytokine levels have often been measured by clinicians to monitor immune status. Proinflammatory cytokines (such as tumor necrosis factor-α [TNF-α], interleukin-2 receptor [IL-2R], interleukin-6 [IL-6], and interleukin-8 [IL-8]) and anti-inflammatory cytokines (such as interleukin-10 [IL-10]) are the ones most measured.[14] CD14+ monocyte human leukocyte antigen-D-related (HLA-DR) expression is another biomarker of immune status that has been proven to have high sensitivity and specificity. Monocytes with low HLA-DR expression have reduced cytokine secretion and antigen presentation ability. HLA-DR expression <30% is indicative of immunosuppression.[15,16] Although those biomarkers can reflect immune dysfunction, a single biomarker cannot precisely reflect immune status due to the complexity of immune reactions. Thus, an immune model based on the combination of multiple biomarkers is needed.

In this study, we aim to introduce a model of the immune status classification of sepsis based on immune markers and to explore the association between immune classification and prognosis.

METHODS

Study setting and population

We performed a prospective study in septic patients admitted to the ICU of the Department of Emergency Medicine, Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, China, between July 2016 and December 2018. The diagnosis of sepsis was made according to the Sepsis-3 definition.[2] The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) the patient fulfilled the Sepsis-3 definition; (2) patients or authorized family members signed informed consent; and (3) the patient was ≥18 years old. The exclusion criteria were: (1) pregnancy; (2) use of immunosuppressants/immunity enhancers for more than six months prior to admission; (3) an immunocompromised host, such as the recipient of chemotherapy or radiation therapy, the recipient of an organ transplant, and patients infected by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV); (4) severe organ dysfunction with poor short-term prognosis, such as chronic heart failure (New York Heart Assessment IV), liver failure (Child-Pugh C), or kidney failure (stage 5 chronic kidney disease); and (5) a history of mental illness.

Data and sample collection

The following data were collected: (1) baseline characteristics, such as age, sex, and comorbidities; (2) site of infection; (3) Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) score and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score on days 1 and 3 after admission; (4) peripheral white blood cell (WBC) counts, C-reactive protein (CRP), and procalcitonin (PCT) at days 1 and 3 after admission; (5) clinical interventions, such as the use of glucocorticoids (equivalent to prednisone >200 mg/d), mechanical ventilation, deep venous catheterization, and urinary catheterization; (6) adverse events during the hospital stay, such as septic shock, secondary infection, acute heart failure, acute kidney injury, acute liver injury, and acute respiratory failure; and (7) ICU length of stay (LOS) and outcome of hospital stay. Peripheral blood samples were collected at days 1 and 3 after admission to measure serum cytokine levels and HLA-DR expression. Because of the limitation of the real-world clinical conditions, blood samples were collected from part of patients at day 3.

Measurement of the levels of immune markers

In order to measure serum cytokine levels, blood samples were collected in BD Vacutainer® SSTTM II Advance tubes (BD Biosciences, USA). Plasma samples were preserved at −80 °C after centrifugation. The serum levels of TNF-α, IL-2R, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10 were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (R&D Systems, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To explore CD14+ HLA-DR+ monocyte expression, blood samples were collected into BD Vacutainer® K2 EDTA tubes and peripheral blood mononuclear cells were acquired. Antibodies used in flow cytometry were fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-anti-CD14 and allophycocyanin (APC)-HLA-DR (BD Biosciences, CA, USA). Appropriate isotype controls were run with healthy controls and used for compensation and gating blood samples. Cell stain samples were analyzed on LSRFortessa (BD Biosciences, CA, USA), and data were analyzed by FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc, OR, USA). HLA-DR was expressed as the percentage of CD14+ HLA-DR+ monocytes among all CD14+ monocytes. The gating strategy is shown in supplementary Figure 1.

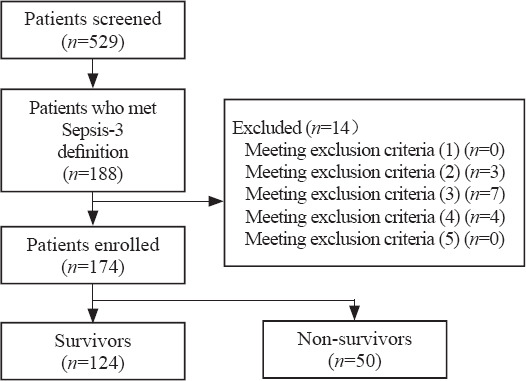

Figure 1.

Study flowchart.

Models of immune status classification and its dynamic changes

Immune markers were measured to define the immune status class. TNF-α, IL-2R, IL-6, and IL-8 were treated as proinflammatory markers, while IL-10 and HLA-DR were anti-inflammatory markers. Cutoff values were obtained from receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. Serum cytokine level higher than the cutoff point or HLA-DR expression lower than the cutoff point was defined as “positive (+)”; otherwise, they were defined as “negative (–)”. SIRS was defined as 0–4 proinflammatory markers (+) and 0 anti-inflammatory markers (+). CARS was defined as 0–2 proinflammatory markers (+) and 1–2 anti-inflammatory markers (+). MARS was defined as 3–4 proinflammatory markers (+) and 1–2 anti-inflammatory markers (+) (supplementary Table 1). The dynamic changes in immune status from days 1 to 3 were classified into the following four groups. Stabilization (SB) meant that SIRS or CARS remained unchanged through days 1 to 3. Deterioration (DT) meant a change from SIRS or CARS at day 1 to MARS at day 3. Remission (RM) meant a change from MARS at day 1 to SIRS or CARS at day 3. Nonremission (NR) meant that MARS remained unchanged through days 1 to 3 (supplementary Table 2).

Statistical analysis

Data normality was tested by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Normally distributed data were expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD) and were compared by Student’s t-test. Abnormally distributed continuous variables were expressed as median (25th and 75th quartiles) and were compared by the Mann-Whitney U-test. Categorical data were expressed as frequencies and percentages and were compared by Pearson’s Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate.

The risk factors for in-hospital mortality were firstly explored by univariate analysis. Immune marker levels were covariates together with age, sex, comorbidities, main site of infection, severity of disease, inflammatory marker levels, clinical interventions, adverse events, and ICU LOS. Covariates with statistical significance were tested in multivariate logistic regression analysis by the “enter” method to explore independent risk factors.

ROC curves were used to detect the cutoff value of each immune marker. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was conducted to compare the outcomes between patients with positive and negative marker levels, between patients with each immune status class, and between patients with different immune status changes over a 30-day follow-up. Dynamic changes in inflammatory markers and disease severity scores from days 1 to 3 were tested by the Wilcoxon signed rank test. The mortality rates of each immune status group and each immune status change group were compared by Pearson’s Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. All statistical analyses were two-sided, and the significance level was set to P<0.05. Model assumptions were tested before using statistical methods. Statistical analysis was conducted in SPSS 25.0 (SPSS Inc., IL, USA).

RESULTS

Characteristics of septic patients

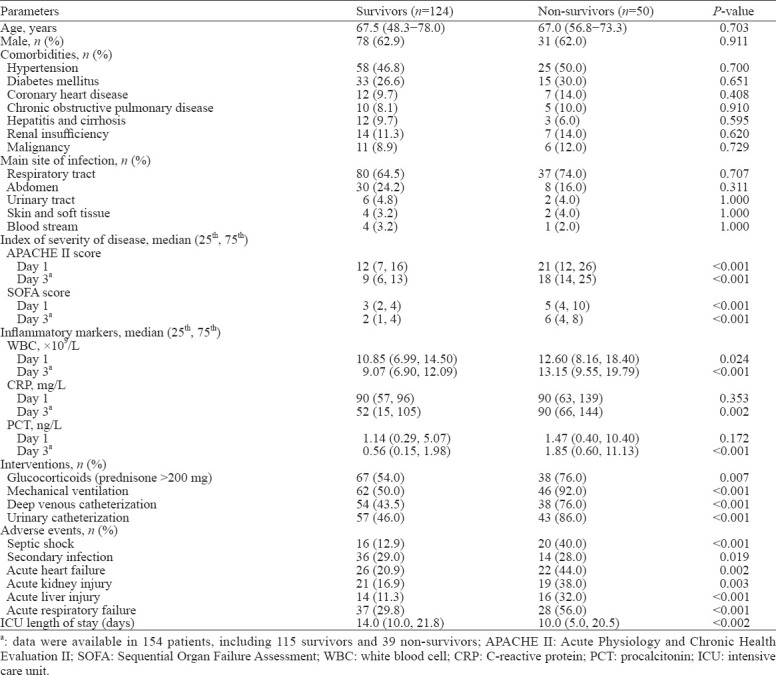

A total of 174 septic patients were enrolled, including 124 survivors and 50 non-survivors (Figure 1). Data of all patients were available at day 1. Six patients died before day 3, and one patient was discharged alive before day 3. Blood collections were not ordered for 13 patients by the treating clinicians due to practical clinical conditions. Thus, data from 154 patients were available at day 3, including 115 survivors and 39 non-survivors.

Among all enrolled patients, 109 were men, and the median age was 67 years. The respiratory tract was the most common site of primary infection (n=117, 67.2%). In total, 28.7% (50/174) of patients died in the hospital. The clinical characteristics of the enrolled patients are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of enrolled patients classified according to prognosis

Association between immune markers and in-hospital mortality of septic patients

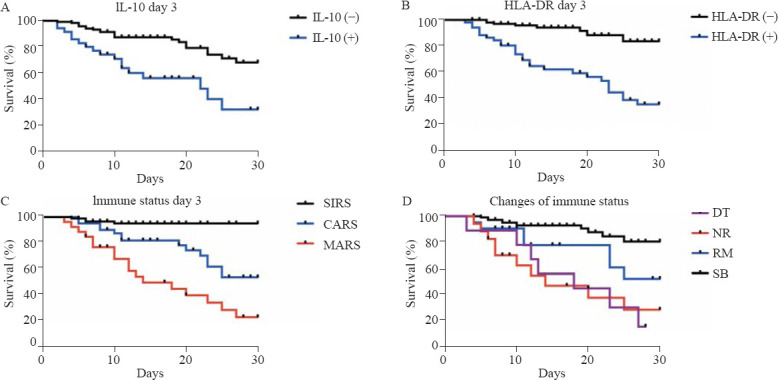

Serum levels of immune markers are shown in supplementary Table 3. The data revealed that serum levels of all cytokines were the highest at day 1 in both survivors and non-survivors. Univariate analysis revealed that non-survivors had higher levels of both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines and lower HLA-DR expression at day 1 (TNF-α [P=0.003], IL-2R [P=0.013], IL-6 [P<0.001], IL-8 [P<0.001], IL-10 [P<0.001], HLA-DR [P<0.001]) and day 3 (TNF-α [P<0.001], IL-2R [P=0.029], IL-6 [P<0.001], IL-8 [P<0.001], IL-10 [P<0.001], HLA-DR [P<0.001])(supplementary Table 3). Patients with positive markers (except IL-2R at day 1) showed worse 30-day survival, as revealed by the log-rank test after applying the cutoff values (day 1: TNF-α [P=0.035], IL-6 [P=0.002], IL-8 [P=0.02], IL-10 [P=0.001], HLA-DR [P<0.001]; day 3: TNF-α [P<0.001], IL-2R [P<0.001], IL-6 [P=0.013], IL-8 [P=0.003], IL-10 [P<0.001], HLA-DR [P<0.001]) (Figure 2 and supplementary Figure 2). Multivariate analysis revealed that MARS at day 3 and mechanical ventilation were independent risk factors for in-hospital mortality (supplementary Table 4). The areas under the ROC curves (AUCs) in the analysis of HLA-DR expression (P<0.001) and IL-10 (P<0.001) at day 3 were also higher than those of other markers (supplementary Table 3).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of septic patients. A: comparison between the group with positive IL-10 levels and that with negative levels at day 3 (P<0.001); B: comparison between the group with positive HLA-DR levels and that with negative levels at day 3 (P<0.001); C: comparison between different immune status classifications at day 3 (SIRS vs. CARS [P<0.001], SIRS vs. MARS [P<0.001], CARS vs. MARS [P=0.008]); D: comparison between different classifications of immune status changes (SB vs. RM [P=0.028], SB vs. NR [P<0.001], SB vs. DT [P<0.001]). The survival curve of DT intersected with that of RM and NR, in which case the log-rank test was not conducted; HLA-DR: human leukocyte antigen-D-related; SIRS: systemic inflammatory response syndrome; CARS: compensatory anti-inflammatory response syndrome; MARS: mixed antagonistic response syndrome; DT: deterioration; NR: nonremission; RM: remission; SB: stabilization.

Association between immune status classification and mortality in septic patients

Since TNF-α, IL-2R, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and HLA-DR all had prognostic value in univariate analysis, we combined these markers to classify patients into certain immune status groups and explored their prognosis. The immune status classifications were based on the best cutoff values of the serum levels of those immune markers, as introduced in supplementary Table 1.

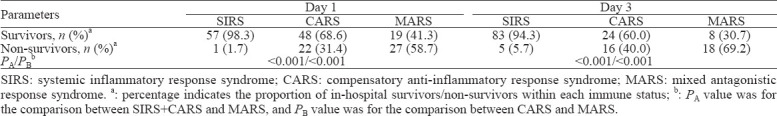

Based on the immune status at days 1 and 3, patients classified into MARS had balanced baseline characteristics compared with those classified into SIRS and CARS, but had higher disease severity scores (day 1: APACHE II score [P<0.001], SOFA score [P<0.001]; day 3: APACHE II score [P<0.001], SOFA score [P<0.001]), higher levels of inflammatory markers (day 1: WBC [P<0.001], CRP [P<0.001], PCT [P<0.001]; day 3: WBC [P=0.005], CRP [P=0.001], PCT [P<0.001]), and higher chances of developing adverse events such as septic shock (day 1: P<0.001; day 3: P<0.001), acute heart failure (day 1: P=0.005; day 3: P=0.043), acute kidney injury (day 1: P=0.009; day 3: P<0.001), acute liver injury (day 1: P=0.006; day 3: P<0.001), and acute respiratory failure (day 3: P=0.008) (supplementary Tables 5 and 6). MARS was associated with a higher mortality rate of septic patients than SIRS and CARS (day 1: odds ratio [OR] 6.487, 95% confidence interval [95% CI] 3.094 to 13.601, P<0.001; day 3: OR 11.464, 95% CI 4.411 to 29.798, P<0.001) (Table 2). In the survival analysis based on immune status at day 3, CARS and MARS both had worse prognoses than SIRS (P<0.001 and P<0.001, respectively). MARS brought a worse prognosis than CARS (P=0.008) (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Association between immune status classification and outcome of septic patients

The immune status of 71 (46.1%) patients changed from day 1 to day 3. To better describe the dynamic changes, four classifications were introduced. Totally 107 patients were classified into the SB group, with a mortality of 11.2%. Nine patients were classified into the DT group, with a mortality rate of 77.8%, which was the highest. Twenty-one patients were classified into the RM group, and 17 patients were classified into the NR group, with mortality rates of 42.9% and 64.7%, respectively. The APACHE II score (P<0.001), SOFA score (P<0.001), WBC (P=0.02), CRP (P<0.001) and PCT (P<0.001) decreased from day 1 to day 3 in the SB group (supplementary Table 7). However, no statistical significance was found in the other three groups with regard to the corresponding changes in disease severity scores and inflammatory markers. In the survival analysis, SB had a better prognosis than RM, NR, and DT (P=0.028, P<0.001, and P<0.001, respectively).

DISCUSSION

The immune mechanism of sepsis has been widely studied. Both innate and adaptive immune function are compromised in patients with sepsis.[6] The classic biphasic model presumes that sepsis features an initial proinflammatory phase and a subsequent anti-inflammatory phase.[17] However, more evidence has shown that sepsis-induced immune dysfunction is highly variable, so a competition model is introduced in which pro- and anti-inflammatory activities are in dynamic equilibrium and mutually interact.[18-22] The proper monitoring of immune status and reversal of immune disorders are crucial to the treatment of septic patients. Combining multiple immune markers to compensate for the low prediction efficiency of single markers, this study found a poor prognosis of patients with severe immune dysfunction, named MARS, and deterioration of immune status, named DT.

Immune status can be measured by many approaches.[23] We chose cytokines as biomarkers of immune dysfunction. Serum cytokine levels were higher in non-survivors, which was consistent with previous studies[14,24,25] that sepsis induced an intensive host immune reaction to pathogens, called the “cytokine storm” and could lead to poor prognosis. Additionally, HLA-DR expression could reflect the functions of both innate and adaptive immune systems, and its lower expression indicates immunosuppression.[6,15] In our study, non-survivors had lower HLA-DR expression. This confirmed that HLA-DR expression can best reflect immune function and predict prognosis after 48 hours of sepsis duration.[16] Our study also supported the competition model by demonstrating that pro- and anti-inflammatory activities in sepsis occurred concurrently, which were reflected by simultaneously elevated serum levels of both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines and lower HLA-DR expression.

Although the prognostic value of many immune markers has been widely studied, it has rarely been reported how to combine multiple immune markers to reach a more precise definition of immune status and a better prediction of mortality. A previous study showed that the combination model of anti- and proinflammatory cytokines had higher prognostic value for sepsis.[26] In this study, we combined HLA-DR expression and cytokine levels to define each immune status, namely, SIRS, CARS and MARS. A recent study on their mechanisms confirmed that CARS can arise at the beginning of the disease course but not following SIRS, and SIRS and CARS are both regulated by infiltrating macrophages and T cells and depend on the Nod-like receptor pyrin containing (NLRP) 3 inflammasome.[27] The concept of MARS was introduced as either the coexistence of overwhelming inflammation and suppression of innate and adaptive immunity or an intermediate phase between SIRS and CARS.[11] We defined MARS as an independent phase of severely imbalanced pro- and anti-inflammatory processes, and our data demonstrated that MARS was more frequent in non-survivors, while SIRS and CARS were more frequent in survivors. MARS at day 3 was also an independent risk factor for poor outcome, as revealed by our multivariate analysis. This confirmed that uncontrolled, excessive inflammatory activities could lead to poor prognosis.

A high proportion (46.1%) of changes in immune status from days 1 to 3 was revealed by our study. Many previous studies have shown that changes in immune status should not be underestimated,[4,12,13] so we introduced a model to dynamically monitor changes. DT had the highest mortality rate of 77.8%, while SB had the lowest mortality rate of 11.2%. These findings stress on the importance of maintaining a stable immune status for patients with SIRS or CARS on admission. The mortality rates of the RM and NR groups were both high, but the former was lower, which suggested that the proper management of immune disorders could bring survival benefits to patients with MARS. We also discovered a corresponding decrease in disease severity scores and inflammatory marker levels.

Our study had several limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small, as it was a single-center study. Second, we only collected the data at days 1 and 3. Thus, the immune status and its dynamic changes could not be traced later than day 3. Third, we calculated the cutoff value of each immune marker from the ROC curve to establish a model of immune dysfunction, but the rationale for this classification is worthy of further verification. Fourth, only six accessible biomarkers were chosen as elements of classification. More biomarkers with high sensitivity and specificity need to be discovered. The use of glucocorticoids might have influenced the process of immune reaction and the expression of immune markers, but this condition was more similar to the real clinical setting.

CONCLUSIONS

Serum cytokine levels and HLA-DR expression may be associated with the prognosis of septic patients. Patients with a severe immune disorder, defined as MARS, or deterioration of immune status, defined as DT, are more likely to have poor outcomes. Our study has provided a preliminary model for the monitoring of immune status, which might be beneficial to the individualized treatment of patients.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81471840, 81171837), the Shanghai Traditional Medicine Development Project (ZY3-CCCX3-3018, ZHYY-ZXYJH-201615), and the Key Project of Shanghai Municipal Health Bureau (2016ZB0202).

Ethical approval: The clinical study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University (Approval number: B2014-082), and registered at the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (Registration number: ChiCTR-OCC-14005202). All protocols were carried out according to relevant guidelines and regulations. Written informed consent was obtained from participants on admission.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Contributors: JY, YC, and JLH contributed equally to this work.

ZJS, CXB, JY, JLH, YC and CYT contributed to the conception and design of the work. JY, YC, ZSK, MMX, SS, HX, YYH and ZMD contributed to the data collection, statistical analysis and interpretation of the results. JLH, LY and ZSK performed the experimental measurements of HLA-DR expression and serum cytokine levels. YC, JY, CXB and ZJS contributed to the drafting and revision of the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

All the supplementary files in this paper are available at www.wjem.com.cn.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kempker JA, Martin GS. The changing epidemiology and definitions of Sepsis. Clin Chest Med. 2016;37(2):165–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315(8):801–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perner A, Gordon AC, De Backer D, Dimopoulos G, Russell JA, Lipman J, et al. Sepsis:frontiers in diagnosis, resuscitation and antibiotic therapy. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(12):1958–69. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4577-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hotchkiss RS, Monneret G, Payen D. Sepsis-induced immunosuppression:from cellular dysfunctions to immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(12):862–74. doi: 10.1038/nri3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang YM, Zheng YJ, Chen Y, Huang YC, Chen WW, Ji R, et al. Effects of fluid balance on prognosis of acute respiratory distress syndrome patients secondary to sepsis. World J Emerg Med. 2020;11(4):216–22. doi: 10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Venet F, Monneret G. Advances in the understanding and treatment of sepsis-induced immunosuppression. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017;14(2):121–37. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2017.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gurung P, Rai D, Condotta SA, Babcock JC, Badovinac VP, Griffith TS. Immune unresponsiveness to secondary heterologous bacterial infection after sepsis induction is TRAIL dependent. J Immunol. 2011;187(5):2148–54. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gomez HG, Gonzalez SM, Londoño JM, Hoyos NA, Niño CD, Leon AL, et al. Immunological characterization of compensatory anti-inflammatory response syndrome in patients with severe sepsis:a longitudinal study. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(4):771–80. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delano MJ, Ward PA. The immune system's role in sepsis progression, resolution, and long-term outcome. Immunol Rev. 2016;274(1):330–53. doi: 10.1111/imr.12499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hotchkiss RS, Monneret G, Payen D. Immunosuppression in sepsis:a novel understanding of the disorder and a new therapeutic approach. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(3):260–8. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70001-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Novotny AR, Reim D, Assfalg V, Altmayr F, Friess HM, Emmanuel K, et al. Mixed antagonist response and sepsis severity-dependent dysbalance of pro- and anti-inflammatory responses at the onset of postoperative sepsis. Immunobiology. 2012;217(6):616–21. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2011.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Venet F, Lepape A, Monneret G. Clinical review:flow cytometry perspectives in the ICU - from diagnosis of infection to monitoring of injury-induced immune dysfunctions. Crit Care. 2011;15(5):231. doi: 10.1186/cc10333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Venet F, Lukaszewicz AC, Payen D, Hotchkiss R, Monneret G. Monitoring the immune response in sepsis:a rational approach to administration of immunoadjuvant therapies. Curr Opin Immunol. 2013;25(4):477–83. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mera S, Tatulescu D, Cismaru C, Bondor C, Slavcovici A, Zanc V, et al. Multiplex cytokine profiling in patients with sepsis. APMIS. 2011;119(2):155–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2010.02705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhuang Y, Peng H, Chen Y, Zhou S, Chen Y. Dynamic monitoring of monocyte HLA-DR expression for the diagnosis, prognosis, and prediction of sepsis. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2017;22:1344–54. doi: 10.2741/4547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Y, Hu Y, Zhang J, Shen Y, Huang J, Yin J, et al. Clinical characteristics, risk factors, immune status and prognosis of secondary infection of sepsis:a retrospective observational study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2019;19(1):185. doi: 10.1186/s12871-019-0849-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muenzer JT, Davis CG, Chang K, Schmidt RE, Dunne WM, Coopersmith CM, et al. Characterization and modulation of the immunosuppressive phase of sepsis. Infect Immun. 2010;78(4):1582–92. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01213-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang BM, Huang SJ, McLean AS. Genome-wide transcription profiling of human sepsis:a systematic review. Crit Care. 2010;14(6):R237. doi: 10.1186/cc9392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yende S, Kellum JA, Talisa VB, Peck Palmer OM, Chang CCH, Filbin MR, et al. Long-term host immune response trajectories among hospitalized patients with sepsis. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(8):e198686. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mira JC, Gentile LF, Mathias BJ, Efron PA, Brakenridge SC, Mohr AM, et al. Sepsis pathophysiology, chronic critical illness, and persistent inflammation-immunosuppression and catabolism syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(2):253–62. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stearns-Kurosawa DJ, Osuchowski MF, Valentine C, Kurosawa S, Remick DG. The pathogenesis of sepsis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:19–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tamayo E, Fernández A, Almansa R, Carrasco E, Heredia M, Lajo C, et al. Pro- and anti- inflammatory responses are regulated simultaneously from the first moments of septic shock. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2011;22(2):82–7. doi: 10.1684/ecn.2011.0281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reinhart K, Bauer M, Riedemann NC, Hartog CS. New approaches to sepsis:molecular diagnostics and biomarkers. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25(4):609–34. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00016-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu LH, Chao CH, Yeh TM. Inhibition of autophagy protects against sepsis by concurrently attenuating the cytokine storm and vascular leakage. J Infect. 2019;78(3):178–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2018.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kang S, Tanaka T, Inoue H, Ono C, Hashimoto S, Kioi Y, et al. IL-6 trans-signaling induces plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 from vascular endothelial cells in cytokine release syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117(36):22351–56. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2010229117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andaluz-Ojeda D, Bobillo F, Iglesias V, Almansa R, Rico L, Gandía F, et al. A combined score of pro- and anti-inflammatory interleukins improves mortality prediction in severe sepsis. Cytokine. 2012;57(3):332–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sendler M, van den Brandt C, Glaubitz J, Wilden A, Golchert J, Weiss FU, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome regulates development of systemic inflammatory response and compensatory anti-inflammatory response syndromes in mice with acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(1):253–69. e14. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]