Abstract

Question

What were the experiences of physiotherapists and patients who consulted via videoconference during the COVID-19 pandemic and how was it implemented?

Design

Mixed methods study with cross-sectional national online surveys and qualitative analysis of free-text responses.

Participants

A total of 207 physiotherapists in private practice or community settings and 401 patients aged ≥ 18 years who consulted (individual and/or group) via videoconference from April to November 2020.

Methods

Separate customised online surveys were developed for physiotherapists and patients. Data were collected regarding the implementation of videoconferencing (cost, software used) and experience with videoconferencing (perceived effectiveness, safety, ease of use and comfort communicating, each scored on a 4-point ordinal scale). Qualitative content analysis was performed of physiotherapists’ free-text responses about perceived facilitators, barriers and safety issues.

Results

Physiotherapists gave moderate-to-high ratings for the effectiveness of and their satisfaction with videoconferencing. Most intended to continue to offer individual consultations (81%) and group classes (60%) via videoconferencing beyond the pandemic. For individual consultations and group classes, respectively, most patients had moderately or extremely positive perceptions about ease of technology use (94%, 91%), comfort communicating (96%, 86%), satisfaction with management (92%, 93%), satisfaction with privacy/security (98%, 95%), safety (99% both) and effectiveness (83%, 89%). Compared with 68% for group classes, 47% of patients indicated they were moderately or extremely likely to choose videoconferencing for individual consultations in the future. Technology was predominant as both a facilitator and barrier. Falls risk was the main safety factor.

Conclusion

Patients and physiotherapists had overall positive experiences using videoconferencing for individual consultations and group classes. The results suggest that videoconferencing is a viable option for the delivery of physiotherapy care in the future.

Key words: Telehealth, COVID-19, Video, Experiences, Patient, Physical therapy

Introduction

In the past decade, telehealth has emerged as a viable mode of service delivery that has the potential to increase healthcare accessibility. There is evidence that telehealth is an effective physiotherapy service delivery mode for some conditions, with outcomes similar to, or even better than, those achieved with in-person care in musculoskeletal conditions,1, 2, 3, 4 joint surgery,5 and cardiac6 and pulmonary7 rehabilitation. There is also some evidence that telehealth is perceived to be safe and effective by physiotherapists delivering the service8 and by patients with various conditions, including: osteoarthritis,8 chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,9 , 10 following knee replacement,11 heart failure,12 and older patients with disability.13 However, research on the effectiveness and acceptability of telehealth for other conditions and streams of physiotherapy is lacking. In addition, outside of cardiac and pulmonary conditions,9 , 12 , 14 , 15 there is very limited evidence examining the efficacy and acceptability of group physiotherapy classes via telehealth. With advances in technology and the availability of affordable videoconferencing software, telehealth has the potential to revolutionise the way in which healthcare is provided,16 and thus further research is warranted.

Although there is some evidence supporting telehealth’s effectiveness and acceptability for some conditions, uptake had previously been slow in Australia and around the world due to a range of factors, including: lack of reimbursement for services; inadequate physiotherapist knowledge, experience or confidence in telehealth; clinician resistance to changing clinical practice; and patient beliefs or preferences for in-person care.3 , 17 , 18 In addition, most research has examined physiotherapy via telehealth in the context of research settings, often as part of a clinical trial and often using sophisticated and potentially inaccessible or expensive telehealth technologies. As such, it is currently unclear whether the existing evidence reflects user experiences with telehealth in a ‘real-world’ setting.

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic had a dramatic impact on healthcare delivery worldwide,19 , 20 with many physiotherapy services rapidly transitioning to telehealth, often with limited preparation or staff training.21 This unprecedented uptake in telehealth provided a unique opportunity to evaluate the perceived effectiveness, acceptability and implementation of such services in the community and across a wide range of users and patient populations.22 , 23 Such information will help identify factors that facilitate or impede use of telehealth in ‘real-world’ settings, thus informing future development and implementation of such services, as well as physiotherapy telehealth training programs and funding sources.

As such, this study aimed to investigate the implementation of and experiences with individual consultations and group classes delivered via videoconferencing during the COVID-19 pandemic, from the perspective of patients who received and physiotherapists who delivered care.

Therefore, the research question for this mixed-methods study was:

What were the experiences of physiotherapists and patients who consulted via videoconference during the COVID-19 pandemic and how was it implemented?

Method

Design

A mixed-methods study was conducted with descriptive, cross-sectional national online surveys of samples of physiotherapists and patients in Australia, and qualitative analysis of free-text responses.

Participants

Physiotherapists

Assisted by the Australian Physiotherapy Association, we recruited physiotherapists using advertisements in social media (Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn), targeted emails, publications such as InMotion, and newsletters. To be eligible, physiotherapists had to: be registered with the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency; be working in private practice or community settings; and have provided one or more patient consultations (individual and/or group) via videoconference between April and October 2020.

Patients

We recruited people aged ≥ 18 years who had consulted with a physiotherapist via videoconferencing (individual and/or group) between April and October 2020 for any health problem/condition and who had an email address and access to the Internet. Participating physiotherapists were asked to email eligible patients on behalf of the researchers inviting them to participate. Additional patients were recruited through advertisements on social media (Facebook and LinkedIn).

Procedure

In order to capture information of relevance to key stakeholders and to ensure readability and clarity, customised separate surveys (Appendix 1 on the eAddenda) for physiotherapists and patients were designed with input from researchers, physiotherapists, staff members of the Australian Physiotherapy Association, health insurers, compensable bodies, and consumers. Selected items from the Telehealth Usability Questionnaire were also included.24 The questions mostly required check box answers, including use of 11-point numeric rating scales from 0 to 10 for satisfaction and effectiveness (ranging from 0 = not at all satisfied/effective to 10 = extremely satisfied/effective) and 4-point Likert scales for evaluating experiences with the ease, safety and privacy of telehealth (rated as ‘not at all’, ‘somewhat’, ‘moderately’ or ‘extremely’). Free-text responses were sought for some questions from physiotherapists. Surveys were administered via a secure online platforma.

Patients and physiotherapists first completed online screening and, if eligible, provided consent and proceeded to the corresponding survey. Both surveys ascertained respondent demographics and prior experience with technology and telehealth, as well as experiences with and perceptions about physiotherapy care via videoconference. In addition, the physiotherapist survey ascertained the respondents’ area of practice and the patient survey ascertained the respondents’ clinical condition. The surveys contained separate questions for individual consultations and for group sessions. The physiotherapist survey also contained free-text questions about facilitators and barriers to videoconferencing as well as any safety issues experienced. Physiotherapists and patients went into draws for $1,000 and $500 prizes, respectively, if they completed the survey.

Data analysis

Data were exported from the secure online platforma into a spreadsheetb for analysis. Descriptive statistics, including frequencies (percentages) and means and standard deviations, were used to summarise the data from those who completed the surveys. Geographic locations of respondents (residential location for patients and practice location for physiotherapists) were categorised by postcodes into: metropolitan, regional/rural and remote areas.25

Responses to free-text questions underwent qualitative content analysis.26 This involved three researchers (BJL, BM, DM) independently reading through all responses and coding the data to identify topics and initial patterns of ideas. Codes were organised into categories and combined with similar ideas to form larger themes. Themes with the highest number of individual data points were identified and reported.

Results

A total of 380 physiotherapists underwent online screening, with 162 excluded: 42 were ineligible (not currently providing care via videoconferencing (n = 22), not registered to practise in Australia (n = 11) and not in private practice, community health or outpatient centre (n = 9)) and 120 chose not to participate. The survey was commenced by 218 physiotherapists, of whom 207 (95%) completed the survey.

In total, 671 patients underwent online screening, with 251 excluded: 69 were ineligible (had not had physiotherapy by videoconferencing between April and October 2020 (n = 68), no email or internet access (n = 1)) and 182 chose not to participate. The survey was commenced by 420 eligible patients, with 308 (77%) recruited via email invitation from their treating physiotherapist, 82 (20%) from social media and 11 (3%) by word of mouth. Of the eligible patients, 401 (95%) completed the survey. At the time of survey completion, 315 (79%) patients had finished their episode of physiotherapy care via videoconference, 31 (8%) were still receiving care via videoconference, and this was unknown for 55 (14%). Collectively, patients had consulted with 172 different physiotherapists across 148 clinics in all eight states and territories of Australia.

Characteristics of participants

The characteristics of physiotherapists and patients are shown in Tables 1 and 2 , respectively. Participants mostly resided in major cities (77%) and identified as female (76%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of physiotherapists.

| Characteristics | Physiotherapists (n = 207) |

|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |

| male | 55 (27) |

| female | 152 (73) |

| State, n (%) | |

| Victoria | 80 (39) |

| New South Wales | 45 (22) |

| Queensland | 40 (19) |

| South Australia | 14 (7) |

| Tasmania | 7 (3) |

| Northern Territory | 1 (0) |

| Australian Capital Territory | 4 (2) |

| Western Australia | 16 (8) |

| Geographical location, n (%) | |

| major city | 158 (76) |

| regional | 45 (22) |

| remote | 4 (2) |

| Clinical experience (yr), mean (SD) | 19 (12) |

| Postgraduate qualifications, n (%) | |

| PhD | 16 (8) |

| Masters by research | 10 (5) |

| Masters by coursework | 52 (25) |

| Postgraduate diploma | 25 (12) |

| other | 14 (7) |

| none | 90 (43) |

| Prior training in telehealth, n (%) | |

| yes, online | 23 (11) |

| yes, in person | 8 (4) |

| no | 176 (85) |

| Clinical setting, n (%)a | |

| private practice | 177 (86) |

| community health centre | 20 (10) |

| outpatient clinic | 23 (11) |

| other | 8 (4) |

| Predominant clinical focus, n (%)a | |

| musculoskeletal | 130 (63) |

| sports and exercise | 71 (34) |

| paediatrics | 32 (15) |

| neurology | 29 (14) |

| cardiorespiratory | 4 (2) |

| gerontology | 14 (7) |

| occupational health | 5 (2) |

| aquatic | 3 (1) |

| women’s, men’s and pelvic health | 43 (21) |

| cancer, palliative care | 11 (5) |

| mental health | 2 (1) |

| Telehealth experience prior to COVID-19, n (%) | |

| provided individual videoconference care | 44 (21) |

| provided group videoconference care | 0 (0) |

Percentages total > 100 as respondents could chose more than one answer.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients.

| Characteristics | Patients (n = 401) |

|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |

| male | 95 (24) |

| female | 305 (76) |

| undisclosed | 1 (0) |

| State, n (%) | |

| Victoria | 188 (47) |

| New South Wales | 46 (11) |

| Queensland | 55 (14) |

| South Australia | 47 (12) |

| Tasmania | 29 (7) |

| Northern Territory | 0 (0) |

| Australian Capital Territory | 22 (5) |

| Western Australia | 14 (3) |

| Geographical location, n (%) | |

| major city | 307 (77) |

| regional | 91 (23) |

| remote | 3 (1) |

| Age (yr), n (%) | |

| 18 to 39 | 85 (21) |

| 40 to 49 | 60 (15) |

| 50 to 59 | 88 (22) |

| 60 to 69 | 87 (22) |

| 70 to 79 | 40 (10) |

| ≥ 80 | 8 (2) |

| Confidence using technology, n (%) | |

| not at all confident | 1 (0) |

| somewhat confident | 26 (6) |

| moderately confident | 158 (39) |

| extremely confident | 216 (54) |

| Predominant body part being treated, n (%) | |

| head or neck | 24 (6) |

| back/chest/abdomen | 47 (12) |

| hip/pelvis | 93 (23) |

| lower limb | 93 (23) |

| upper limb | 69 (17) |

| whole body | 66 (16) |

| other | 9 (2) |

| Main reasons for seeking treatment, n (%)a | |

| pain | 235 (59) |

| impaired function | 177 (44) |

| stiffness | 135 (34) |

| weakness | 100 (25) |

| difficulty walking | 73 (18) |

| rehabilitation following trauma/injury | 72 (18) |

| rehabilitation following surgery | 70 (17) |

| balance/falls problems | 43 (11) |

| bladder/bowel control or prolapse | 37 (9) |

| fatigue | 32 (8) |

| rehabilitation for a neurological condition | 28 (7) |

| deconditioning | 23 (6) |

| reduced cardiovascular fitness | 15 (4) |

| breathlessness | 10 (2) |

| frailty | 3 (1) |

| other | 52 (13) |

| Duration of problem, n (%) | |

| < 6 weeks | 38 (9) |

| 6 to 12 weeks | 52 (13) |

| 3 to 12 months | 97 (24) |

| > 12 months | 214 (53) |

Percentages total > 100 as respondents could chose more than one answer.

Physiotherapists had a mean of 19 years (SD 12) of clinical experience, with the majority having postgraduate qualifications. Their predominant clinical focus was musculoskeletal (63%), sports/exercise (34%), and women’s, men’s and pelvic health (21%); however, 11 different clinical areas were represented. Few reported prior training in telehealth (15%). Prior to the pandemic, physiotherapists had limited telehealth experience, with 21% having delivered individual care and none having delivered group classes via videoconference.

Patients were aged from 18 to > 80 years and most reported being moderately (39%) or extremely (54%) confident using technology. Patients sought treatment for a variety of reasons including pain (58%), impaired function (44%) and stiffness (34%), with most problems being chronic and longer than 12 months in duration (53%).

Physiotherapists’ implementation of and experiences with care via videoconferencing

Table 3 summarises physiotherapists’ implementation of and experiences with care delivered via videoconferencing. Individual care was provided by 204 (99%) physiotherapists, while 35 (17%) physiotherapists provided group classes. The mean (SD) duration of physiotherapist experience providing videoconferencing care was 11.9 (16.2) months for individual consultations and 6.8 (1.4) months for group classes. Physiotherapists generally rated their level of experience and confidence in providing such care as moderate to high (average > 7 out of 10). The most common videoconferencing platforms used for individual consultations were Physitrack (30%), Coviu (20%) and Zoom (16%). Zoom was used by the majority (94%) for group classes. A range of supporting patient resources was used, the most common being written instructions, diagrams or booklets (63%), educational material about the issue/condition (54%) and apps for smart phone or tablet (40%) for individual consultations, and text message reminders (66%) and follow-up phone calls (31%) for group classes.

Table 3.

Physiotherapist implementation of and experiences with care provided by videoconference.

| Survey items | Individual (n = 204) |

Group (n = 35) |

|---|---|---|

| Duration of providing VC consultations (mth), mean (SD) | 11.9 (16.2) | 6.8 (1.4) |

| Experience with VC consultations (0 to 10), mean (SD)a | 5.9 (2.3) | 6.9 (2.7) |

| Confidence providing VC consultations (0 to 10), mean (SD)a | 7.3 (1.8) | 8.1 (1.8) |

| Deemed some patients unsuitable for VC, n (%)b | 135 (66) | N/A |

| Main reasons patients deemed unsuitable, n (%)c | ||

| patient unable to access technology | 77 (38) | N/A |

| complexity of problem/condition | 70 (34) | N/A |

| patient required hands-on treatment | 75 (37) | N/A |

| unable to adequately diagnose/assess patient | 55 (27) | N/A |

| complexity of patient | 54 (26) | N/A |

| patient unable to use technology (eg, impairment) | 51 (25) | N/A |

| safety concerns | 32 (16) | N/A |

| other | 11 (5) | N/A |

| Received positive patient feedback, n (%)b | 167 (82) | 29 (85) |

| Patient resources used to support VC consultations, n (%)c | ||

| written instructions, diagrams or booklets | 129 (63) | 9 (26) |

| educational material about issue/condition | 110 (54) | 9 (26) |

| apps for smart phone or tablet | 81 (40) | 10 (29) |

| videos | 81 (40) | 10 (29) |

| websites for further information | 71 (35) | 6 (17) |

| follow-up phone calls | 67 (33) | 11 (31) |

| provision/purchase of equipment/devices | 66 (32) | 8 (23) |

| log books/diaries | 28 (14) | 2 (6) |

| text message reminders | 23 (11) | 23 (66) |

| Effectiveness of VC care (0 to 10), mean (SD)a | 7.0 (1.7) | 7.7 (1.4) |

| Satisfaction with VC care (0 to 10), mean (SD)a | 7.1 (1.6) | 7.5 (1.7) |

| VC platform used, n (%)c | ||

| Physitrack | 62 (30) | 0 (0) |

| Coviu | 40 (20) | 2 (6) |

| Zoom | 33 (16) | 33 (94) |

| Cliniko | 30 (15) | 0 (0) |

| Facetime | 19 (9) | 2 (6) |

| Health Direct | 13 (6) | 0 (0) |

| Microsoft Teams | 12 (6) | 2 (6) |

| other | 46 (23) | 5 (14) |

| Business costs of VC versus in-person consultations, n (%) | ||

| VC would cost the business more | 29 (14) | N/A |

| VC and in-person would cost the same amount | 68 (33) | N/A |

| in-person would cost the business more | 63 (31) | N/A |

| don’t know | 44 (22) | N/A |

| Intending to continue VC care after pandemic, n (%) | ||

| yes | 166 (81) | 21 (60) |

| no | 8 (4) | 5 (14) |

| unsure | 30 (15) | 9 (26) |

N/A = not assessed; VC = videoconference.

0 = not at all, 10 = extremely.

Number (%) of physiotherapists.

Percentages total ≥ 100 as respondents could chose more than one answer.

Physiotherapists charged fees for individual consultations that were slightly lower than those they usually charged for face-to face care: mean 89% (SD 24) of the cost of an equivalent in-person visit for initial consultation and 90% (SD 20) of the cost of an equivalent in-person visit for review. However, opinions differed as to whether the business costs of providing individual care via videoconference would be more than, less than, or the same as providing in-person care.

Over 24 different classes were reported, with the most common being Pilates (38%), Good Life with osteoArthritis:Denmark (GLA:D) (20%), low back pain (18%), post-natal (13%) and pre-natal (11%). Thirty-three (70%) physiotherapists reported setting a limit on group class size, with the average maximum per class being 7.9 patients (SD 5.4).

A total of 66% of physiotherapists deemed one or more patients unsuitable for individual treatment via videoconference, with a range of reasons given, including: patient unable to access the technology, complexity of the problem/patient, unable to adequately assess and requiring hands-on treatment. Physiotherapists gave moderate-to-high ratings (7 to 8 out of 10) for effectiveness and satisfaction with care for both individual treatment and group classes. Many physiotherapists intended to continue offering videoconferencing care individually (81%) or in groups (60%) after the pandemic ended, although a proportion were unsure (15% and 26%, respectively).

Table 4 summarises the main themes relating to physiotherapists’ perceived facilitators, barriers and safety issues of delivering care via videoconference. Technology was predominant as both a facilitator and barrier for individual and group care. Other facilitators included preparing ahead of appointments, having patient resources available (particularly exercise apps) and patients being willing and engaged. Other barriers included lack of physical touch, perceived inability to assess the patient properly and room setup. One of the key safety issues mentioned for both individual and group care was falls risk.

Table 4.

Main themes relating to physiotherapists’ perceived facilitators, barriers and safety issues with delivery of care via videoconference.

| Questions | Individual consultations | Group classes |

|---|---|---|

| What things helped you the most to deliver physiotherapy care via telehealth? |

|

|

| What barriers did you experience delivering physiotherapy care via telehealth? |

|

|

| What safety issues did you experience delivering care via telehealth? |

|

|

n = number of responses that contributed to each theme.

Patient experiences with physiotherapy care via videoconferencing

Patient experiences with physiotherapy care via videoconferencing are summarised in Table 5 . Of the patient respondents, 341 (85%) reported receiving individual physiotherapy care via videoconference, while 77 (19%) attended group classes. For the particular episode of care, the mean number of videoconferencing consultations was 3.9 (SD 5.5) for individual care and 17.9 (SD 26.4) for group sessions. Most patients had previously consulted the physiotherapist in-person for the same problem before switching to videoconferencing. Most patients either fully (41% for individual and 49% for group) or partially (30% for individual and 35% for group) paid for their care themselves. While the majority of patients considered videoconferencing care to be the same or better quality compared with in-person care, just under half (41% of patients receiving individual care and 43% receiving group care) rated it as lower quality. Patients valued individual videoconferencing care for a number of reasons, most commonly convenience (88%), access (54%), less waiting time (39%) and undivided physiotherapist attention (32%).

Table 5.

Patients’ experiences with physiotherapy care provided by videoconference.

| Survey questions | Individual (n = 341) |

Group (n = 77) |

|---|---|---|

| VC consultations for this problem (n), mean (SD) | 3.9 (5.5) | 17.9 (26.4) |

| Percentage of physiotherapy consultations delivered via VC (%), mean (SD) | 56 (34) | 53 (39) |

| Had prior in-person consultations with the same physiotherapist for the same problem, n (%)a | 292 (86) | 55 (71) |

| Payment for VC consultation, n (%) | ||

| patient paid entire fee | 140 (41) | 38 (49) |

| patient paid part fee | 104 (30) | 27 (35) |

| fee paid by other | 97 (28) | 12 (16) |

| Funding source for VC consultation, if part/all of fee paid by other, n (%)b | ||

| private health insurance | 100 (50) | 26 (67) |

| Medicare | 62 (31) | 7 (14) |

| workers compensation scheme | 11 (5) | 1 (3) |

| National Disability Insurance Scheme | 19 (9) | 6 (15) |

| Department of Veterans' Affairs | 6 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Transport Accident Commission | 8 (4) | 1 (3) |

| Expectations and experiences with VC, n (%) | ||

| less than what I expected | 20 (6) | 5 (6) |

| what I expected | 112 (33) | 22 (29) |

| exceeded my expectations | 209 (61) | 50 (65) |

| Quality compared to in-person, n (%)c | ||

| VC lower quality | 97 (42) | 19 (43) |

| VC same quality | 111 (48) | 16 (36) |

| VC better quality | 24 (10) | 9 (20) |

| Most valued about VC, n (%)d | ||

| convenience | 299 (88) | N/A |

| access | 183 (54) | N/A |

| less waiting time | 134 (39) | N/A |

| undivided attention of physio | 110 (32) | N/A |

| treatment effectiveness | 79 (23) | N/A |

| privacy | 71 (21) | N/A |

| cost savings | 67 (20) | N/A |

| COVID-19 safety/social distancing | 51 (15) | N/A |

| other | 18 (5) | N/A |

Numbers do not sum to the total for some items due to missing data.

N/A = not assessed, VC = videoconference.

Number (%) of patients.

Only includes patients who had part/all of fee paid by other: n = 201 for individual and n = 39 for group.

Only includes patients who had received previous in-person care: n = 232 for individual and n = 44 for group.

Percentages total > 100 as respondents could chose more than one answer.

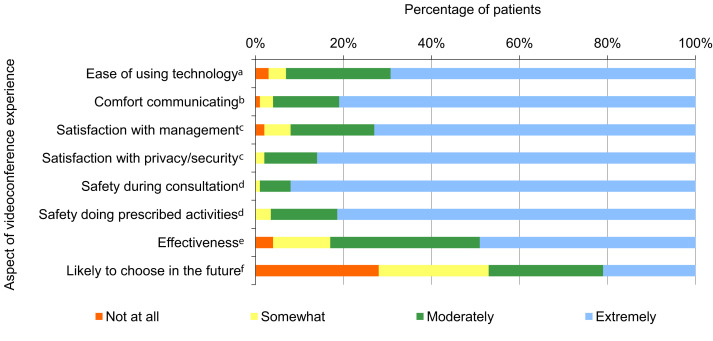

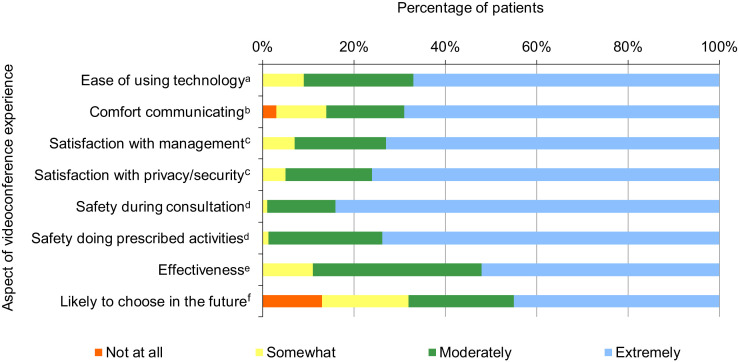

Patient ratings of their experiences are shown in Figure 1 for individual consultations and Figure 2 for group sessions. Most had moderately or extremely positive perceptions about the ease of using the technology (94% individual consultations versus 91% group classes), comfort communicating (96% versus 86%), satisfaction with management (92% versus 93%), satisfaction with privacy/security (98% versus 95%), safety during the consultation (99% versus 99%), safety doing prescribed activities (93% versus 99%), and effectiveness (83% versus 89%). Around half (47%) were moderately or extremely likely to choose to use videoconferencing for individual consultations beyond the pandemic, with 28% not at all likely to do so. For group classes, 68% were moderately or extremely likely to choose to do so via videoconferencing beyond the pandemic, with 13% not at all likely to do so. Full numerical data used to generate Figures 1 and 2 are available in Tables 6 and 7 on the eAddenda.

Figure 1.

Patient ratings of their experiences with individual consultations via videoconference with their physiotherapist (n = 341).

a Rated on a 4-point scale ranging from ‘not at all easy’ to ‘extremely easy’.

b Rated on 4-point scale ranging from ‘not at all comfortable’ to ‘extremely comfortable’.

c Rated on 4-point scale ranging from ‘not at all satisfied’ to ‘extremely satisfied’.

d Rated on 4-point scale ranging from ‘not at all safe’ to ‘extremely safe’.

e Rated on 4-point scale ranging from ‘not at all effective’ to ‘extremely effective’.

f Rated on 4-point scale ranging from ‘not at all likely’ to ‘extremely likely’.

Figure 2.

Patient ratings of their experiences with group classes via videoconference with their physiotherapist (n = 77).

a Rated on a 4-point scale ranging from ‘not at all easy’ to ‘extremely easy’.

b Rated on 4-point scale ranging from ‘not at all comfortable’ to ‘extremely comfortable’.

c Rated on 4-point scale ranging from ‘not at all satisfied’ to ‘extremely satisfied’.

d Rated on 4-point scale ranging from ‘not at all safe’ to ‘extremely safe’.

e Rated on 4-point scale ranging from ‘not at all effective’ to ‘extremely effective’.

f Rated on 4-point scale ranging from ‘not at all likely’ to ‘extremely likely’.

Discussion

This study found that patients and physiotherapists had overall positive experiences with care delivered via videoconferencing during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, although most patients and physiotherapists indicated willingness to use telehealth in the future, almost one-third of patients were unlikely to choose to do so. Barriers to telehealth delivery experienced by physiotherapists included technology issues, a lack of physical touch and poor room setup.

The findings broadly reflect those of other studies investigating physiotherapist’s experiences with telehealth during COVID-19 in other countries. Other surveys of allied healthcare clinicians in Australia, Europe and North America found that satisfaction with telehealth was high,27 physiotherapists believed that using telehealth was part of their professional role28 and they felt confident using telehealth to treat patients.28 However, those studies also found that physiotherapist training in telehealth was lacking28 and less than half of participating clinicians believed that telehealth was as effective as in-person care.28 The lack of physical contact during telehealth was also perceived to hamper accurate and effective diagnosis and management.28 Similar experiences were reported by our cohort of physiotherapists, who were moderately-to-highly satisfied with and confident using videoconferencing to provide care to patients. In addition, our cohort of physiotherapists was also mostly untrained in telehealth and reported that the lack of physical touch was a barrier and limited their ability to conduct a thorough assessment.

Our findings are also broadly similar to others investigating patient experiences using telehealth for physiotherapy during COVID-19. Patients in the US and Italy were found to have high overall satisfaction,27 , 29, 30, 31 being very satisfied with their communication via telehealth,29 the development and execution of their treatment plan,29 and the vast majority indicated that they would use telehealth in the future.29 , 31 Technology issues (including setup and camera angles) and elements of hands-on care (lack of tactile feedback, inability to perform soft tissue work, absence of ‘healing touch’) were identified as limitations of telehealth.29 These findings broadly reflect ours, where, overall, patients had a positive experience using the technology and communicating with the physiotherapist, and felt safe.

Our findings suggest that a much higher proportion of patients as opposed to physiotherapists would not be willing to use videoconferencing to do consultations in the future (28% versus 4%, respectively). This is somewhat surprising given that there is some suggestion in the literature of poor acceptability of and resistance to telehealth amongst physiotherapists.3 , 28 It is possible that first-hand experience with telehealth contributed to a shift in physiotherapists’ perceptions about such services.32 However, it is not immediately clear why patients appear to be less willing to use telehealth than physiotherapists, given that the majority reported positive experiences using the technology and communicating, and believed that the care they received via videoconferencing was effective. This difference may partly be explained by the fact that patients were rating telehealth for themselves and their individual situation/condition, whereas physiotherapists answered in relation to their entire caseload of patients, some of whom may not have been suitable for telehealth. In fact, 66% of physiotherapists deemed some patients as unsuitable for videoconferencing, suggesting that even though they indicated intentions to continue using telehealth, it appears unlikely that they would intend to use it with all of their patients.

We believe that no previous studies have examined patient or physiotherapist experiences with group classes via videoconferencing during COVID-19. Most existing research on group classes delivered via telehealth by a physiotherapist (before the COVID-19 pandemic) has been in cardiac and pulmonary conditions9 , 14 , 15 , 33 and in research settings, rather than a ‘real-world’ environment. Two of those studies included a mixed methods exploration of patient experiences with home-based group exercise classes via videoconferencing for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder34 and people with heart failure.33 Those studies reported high levels of patient satisfaction, with patients enjoying exercising with others, feeling safe and appreciating the accessibility of care (ie, reduced burden and costs of transportation). However, patients in both studies also experienced technical difficulties and needed help operating the system, and suggested that improvements to the audio and visual components of the software/hardware would be beneficial. Around three-quarters of their participants agreed or strongly agreed that they would continue to participate in group classes via telehealth.34 These findings appear to broadly reflect ours, in that our cohort had overall positive experiences, with 68% being moderately or extremely likely to choose to attend group classes via videoconferencing in the future. Although 91% of our cohort found the technology moderately or extremely easy to use, our physiotherapists reported technology issues as one of the main barriers to group classes. Interestingly, patients in our cohort appeared to be more willing to choose to use videoconferencing for group classes in the future (87%), compared with individual consultations (72%). It is unclear why this is, particularly given that satisfaction with other elements (including ease of use, safety and effectiveness) were similar between individual consultations and group classes. In addition, our results suggest that fewer physiotherapists intend to continue to offer group classes via videoconferencing beyond the pandemic (60%), compared with individual consultations (81%). Further research is required to determine why patients and physiotherapists may be more or less willing to attend or deliver group classes via telehealth, compared with individual consultations.

Physiotherapists identified numerous barriers and facilitators to delivering care via telehealth that have implications for the future design and delivery of such services. Technology setup and patient resources were the two most commonly mentioned facilitators, including having reliable hardware and software (on both the physiotherapist and patient end) and use of written/online information, videos and apps. Similar facilitators to telehealth were also reported by other studies investigating implementation of telehealth during COVID-19,23 , 28 , 35 suggesting that future telehealth services should consider these factors. Barriers to telehealth included technology issues (at the physiotherapist and patient end) and the lack of physical touch, which they perceived limited their ability to conduct a thorough assessment and rendered them unable to use hands-on techniques. Such barriers have also been reported in other studies.23 , 28 , 35 Cottrell and Russell3 suggest that telehealth may be most appropriate for observational assessments, but not those requiring physical contact. Blended models of service delivery, where a combination of in-person and telehealth consultations are offered, may be the most suitable approach, where patients and physiotherapists use either, depending on the patient preferences, circumstances and requirements. Technology and setup barriers may be overcome as telehealth services become more mainstream within the community, and also with appropriate training in telehealth. This is particularly relevant given that around one-third (31%) of physiotherapists used platforms that are not specifically designed for telehealth (eg, Zoom, FaceTime, Microsoft Teams). Both physiotherapists and patients in our cohort were relatively naïve with respect to telehealth and, given recent evidence that level of experience with telehealth was associated with more positive perceptions and greater physiotherapist satisfaction,27 it is likely that further experience by both users and providers will lead to higher quality and more acceptable services.

Another important consideration is that most physiotherapists in our surveyed cohort treated mostly chronic, rather than acute, conditions via telehealth. It is unclear whether this was because those with acute conditions were less likely to seek care during the pandemic, whether they were less suited for telehealth, or whether funding/reimbursement was unavailable for acute conditions. In addition, almost three-quarters of patients had already seen their physiotherapist in person for the same problem prior to using telehealth. Again, it is unclear whether this was because patients were less likely to see a physiotherapist for the first time via telehealth, or whether physiotherapists were less willing to see new patients via telehealth. Further research is required to develop guidelines and recommendations to help physiotherapists and service providers better determine which patients may be unsuitable for telehealth.

One of the most commonly reported barriers to the implementation of telehealth is lack of reimbursement by public or private health insurers, as well as the costs of implementing such services (such as obtaining necessary infrastructure).3 , 20 , 36 However, we found that more than one-third of patients paid the entire fee of their consultation via videoconferencing, and around half paid the entire fee for a group class via videoconferencing, suggesting that patients are willing to pay for telehealth. In addition, most physiotherapists believed that the business costs of delivering care via videoconferencing would be equal to or less than the costs of doing so in-person, suggesting that implementing telehealth would not have a detrimental financial impact on service providers. Collectively, these findings suggest that funding and cost barriers to the implementation of telehealth may not be as great as initially thought; further investigation into the long-term costs and funding of telehealth is required.

Only 15% of physiotherapists in our cohort reported that they had prior training in telehealth. This also reflects other studies, which found that only a minority of clinicians had been trained in telehealth.28 Cottrell and Russell3 argue that many barriers to telehealth delivery amongst physiotherapists (such as resistance to changing practice, poor technological self-efficacy, perceived de-personalisation of care, and privacy and safety concerns) reflect a lack of skills and confidence to safely and effectively deliver care via telehealth. As such, this, along with a number of previous publications,23 , 37 have highlighted the need for telehealth training programs. With the uptake of telehealth and the potential of services continuing beyond the pandemic, telehealth training programs may become more common in undergraduate and postgraduate physiotherapist training programs, helping clinicians overcome some of these barriers.

Some strengths of our study include relatively large numbers of physiotherapists and patients across all states and territories in Australia and across numerous practices. Patients were clearly informed that their results would not be shared with their physiotherapist, in order to facilitate more accurate responses. Our study also had limitations. The sampling approach contained an element of convenience sampling, which may have introduced bias. Physiotherapists and patients in tertiary/public hospital settings were not directly sampled and, as such, no information about the full range of settings in which physiotherapy care was provided was available. While the experiences of some physiotherapists whose predominant focus was paediatrics were captured, patient/carer experiences for patients aged < 18 years were not captured. There was also a limited number of respondents who had delivered or undertaken group sessions via videoconference. Our results may not necessarily generalise to other countries where healthcare contexts and physiotherapy practice may differ. A proportion of people chose not to participate (22 to 30%), which may have been because of the burdensome nature of participation. This investigation was also confined to care via videoconferencing; it would have been interesting to have examined and compared physiotherapy services provided by telephone, given that, anecdotally, this delivery mode was also frequently used.

In conclusion, this study found that patients and physiotherapists had overall positive experiences using videoconferencing for both individual consultations and group classes. The results suggest that videoconferencing is a viable option for the delivery of physiotherapy care in the future. Attention to perceived barriers, facilitators and potential safety issues may enhance the implementation of and experiences with telehealth.

What was already known on this topic: Telehealth is an effective physiotherapy service delivery mode, with outcomes similar to or even better than those achieved with in-person care in some clinical conditions. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many physiotherapy services are rapidly transitioning to telehealth.

What this study adds: Patients and physiotherapists had overall positive experiences using videoconferencing for individual consultations and group classes. The results suggest that videoconferencing is a viable option for the delivery of physiotherapy care in the future.

Acknowledgements

Participant survey data were collected and managed using the REDCap Survey Software hosted at the University of Melbourne.

Provenance : Not invited. Peer reviewed.

Footnotes

Footnotes:aREDCap, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, USA. bExcel, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, USA.

eAddenda: Tables 6 and 7, and Appendix 1 can be found online at DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphys.2021.06.009

Ethics approval: The University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee approved this study (Ethics ID: 2056784). All participants gave written informed consent before data collection began.

Competing interests: Karen Finnin owns a telehealth physiotherapy practice. Trevor Russell is involved in revenue-generating telehealth educational programs.

Source(s) ofsupport: This work was supported by funding from the Physiotherapy Research Foundation. Professor Bennell is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Investigator grant (#1174431). Professor Hinman is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Senior Research Fellowship (#1154217). The funders had input in the development of the study method, interpretation of the results and reporting as collaborative partners.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Grona S.L., Bath B., Busch A., Rotter T., Trask C., Harrison E. Use of videoconferencing for physical therapy in people with musculoskeletal conditions: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24:341–355. doi: 10.1177/1357633X17700781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cottrell M.A., Galea O.A., O'Leary S.P., Hill A.J., Russell T.G. Real-time telerehabilitation for the treatment of musculoskeletal conditions is effective and comparable to standard practice: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31:625–638. doi: 10.1177/0269215516645148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cottrell M.A., Russell T.G. Telehealth for musculoskeletal physiotherapy. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2020;48:102193. doi: 10.1016/j.msksp.2020.102193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dario A.B., Moreti Cabral A., Almeida L., Ferreira M.L., Refshauge K., Simic M. Effectiveness of telehealth-based interventions in the management of non-specific low back pain: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Spine J. 2017;17:1342–1351. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2017.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shukla H., Nair S.R., Thakker D. Role of telerehabilitation in patients following total knee arthroplasty: evidence from a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Telemed Telecare. 2017;23:339–346. doi: 10.1177/1357633X16628996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rawstorn J.C., Gant N., Direito A., Beckmann C., Maddison R. Telehealth exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart. 2016;102:1183–1192. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan C., Yamabayashi C., Syed N., Kirkham A., Camp P.G. Exercise telemonitoring and telerehabilitation compared with traditional cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiother Can. 2016;68:242–251. doi: 10.3138/ptc.2015-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hinman R.S., Nelligan R.K., Bennell K.L., Delany C. “Sounds a bit crazy, but it was almost more personal”: a qualitative study of patient and clinician experiences of physical therapist-prescribed exercise for knee osteoarthritis via Skype. Arthritis Care Res. 2017;69:1834–1844. doi: 10.1002/acr.23218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai L.L., McNamara R.J., Moddel C., Alison J.A., McKenzie D.K., McKeough Z.J. Home-based telerehabilitation via real-time videoconferencing improves endurance exercise capacity in patients with COPD: the randomized controlled TeleR Study. Respirology. 2017;22:699–707. doi: 10.1111/resp.12966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoaas H., Andreassen H.K., Lien L.A., Hjalmarsen A., Zanaboni P. Adherence and factors affecting satisfaction in long-term telerehabilitation for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a mixed methods study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16:26. doi: 10.1186/s12911-016-0264-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kairy D., Tousignant M., Leclerc N., Cote A.M., Levasseur M., Researchers T.T. The patient's perspective of in-home telerehabilitation physiotherapy services following total knee arthroplasty. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10:3998–4011. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10093998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hwang R., Bruning J., Morris N.R., Mandrusiak A., Russell T. Home-based telerehabilitation is not inferior to a centre-based program in patients with chronic heart failure: a randomised trial. J Physiother. 2017;63:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2017.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shulver W., Killington M., Morris C., Crotty M. ‘Well, if the kids can do it, I can do it': older rehabilitation patients' experiences of telerehabilitation. Health Expect. 2017;20:120–129. doi: 10.1111/hex.12443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ptomey L.T., Willis E.A., Lee J., Washburn R.A., Gibson C.A., Honas J.J. The feasibility of using pedometers for self-report of steps and accelerometers for measuring physical activity in adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities across an 18-month intervention. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2017;61:792–801. doi: 10.1111/jir.12392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burkow T.M., Vognild L.K., Johnsen E., Risberg M.J., Bratvold A., Breivik E. Comprehensive pulmonary rehabilitation in home-based online groups: a mixed method pilot study in COPD. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:766. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1713-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hinman R.S., Campbell P.K., Lawford B.J., Briggs A.M., Gale J., Bills C. Does telephone-delivered exercise advice and support by physiotherapists improve pain and/or function in people with knee osteoarthritis? Telecare randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54:790–797. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2019-101183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawford B.J., Bennell K.L., Kasza J., Hinman R.S. Physical therapists' perceptions of telephone- and internet video-mediated service models for exercise management of people with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2018;70:398–408. doi: 10.1002/acr.23260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hinman R., Lawford B.J., Bennell K. Harnessing technology to deliver care by physical therapists for people with persistent joint pain: telephone and video-conferencing service models. J Appl Biobehav Res. 2018;24:e12150. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monaghesh E., Hajizadeh A. The role of telehealth during COVID-19 outbreak: a systematic review based on current evidence. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1193. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09301-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duckett S. What should primary care look like after the COVID-19 pandemic? Aust J Prim Health. 2020;26:207–211. doi: 10.1071/PY20095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Physiotherapy Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on physiotherapy services globally. 2021. https://world.physio/sites/default/files/2021-03/Covid-Report_March2021_FINAL.pdf

- 22.Stanhope J., Weinstein P. Learning from COVID-19 to improve access to physiotherapy. Aust J Prim Health. 2020;26:271–272. doi: 10.1071/PY20141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Signal N., Martin T., Leys A., Maloney R., Bright F. Implementation of telerehabilitation in response to COVID-19: lessons learnt from neurorehabilitation clinical practice and education. NZ J Physiother. 2020;48:117–126. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parmanto B., Lewis A.N., Graham K.M., Bertolet M.H. Development of the Telehealth Usability Questionnaire (TUQ) Int J Telerehabil. 2016;8:3–10. doi: 10.5195/ijt.2016.6196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Department of Health . Australian Government Department of Health; 2015. Modified Monash Model.https://www.health.gov.au/health-workforce/health-workforce-classifications/modified-monash-model [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsieh H.F., Shannon S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Assenza C., Catania H., Antenore C., Gobbetti T., Gentili P., Paolucci S. Continuity of care during COVID-19 lockdown: a survey on stakeholders' experience with telerehabilitation. Front Neurol. 2020;11:617276. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.617276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malliaras P., Merolli M., Williams C.M., Caneiro J.P., Haines T., Barton C. ‘It's not hands-on therapy, so it's very limited': telehealth use and views among allied health clinicians during the coronavirus pandemic. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2021;52:102340. doi: 10.1016/j.msksp.2021.102340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tenforde A.S., Borgstrom H., Polich G., Steere H., Davis I.S., Cotton K. Outpatient physical, occupational, and speech therapy synchronous telemedicine: a survey study of patient satisfaction with virtual visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;99:977–981. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Negrini S., Donzelli S., Negrini A., Negrini A., Romano M., Zaina F. Feasibility and acceptability of telemedicine to substitute outpatient rehabilitation services in the COVID-19 emergency in Italy: an observational everyday clinical-life study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;101:2027–2032. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller M.J., Pak S.S., Keller D.R., Barnes D.E. Evaluation of pragmatic telehealth physical therapy implementation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Phys Ther. 2021;101:193. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzaa193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lawford B.J., Delany C., Bennell K.L., Hinman R.S. “I was really pleasantly surprised”: first-hand experience with telephone-delivered exercise therapy shifts physiotherapists' perceptions of such a service for knee osteoarthritis. A qualitative study. Arthritis Care Res. 2018;71:545–557. doi: 10.1002/acr.23618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hwang R., Mandrusiak A., Morris N.R., Peters R., Korczyk D., Bruning J. Exploring patient experiences and perspectives of a heart failure telerehabilitation program: a mixed methods approach. Heart Lung. 2017;46:320–327. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsai L.L.Y., McNamara R.J., Dennis S.M., Moddel C., Alison J.A., McKenzie D.K. Satisfaction and experience with a supervised home-based real-time videoconferencing telerehabilitation exercise program in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) Int J Telerehabil. 2016;8:27–38. doi: 10.5195/ijt.2016.6213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Turolla A., Rossettini G., Viceconti A., Palese A., Geri T. Musculoskeletal physical therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic: is telerehabilitation the answer? Phys Ther. 2020;100:1260–1264. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzaa093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin C.C., Dievler A., Robbins C., Sripipatana A., Quinn M., Nair S. Telehealth in health centers: key adoption factors, barriers, and opportunities. Health Aff. 2018;37:1967–1974. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edirippulige S., Armfield N.R. Education and training to support the use of clinical telehealth: a review of the literature. J Telemed Telecare. 2017;23:273–282. doi: 10.1177/1357633X16632968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.