Abstract

This paper proposes a model for understanding the effects of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) as dynamic and interrelated biobehavioral adaptations to early life stress that have predictable consequences on development and health. Drawing upon research from multiple theoretical and methodological approaches, the Intergenerational and Cumulative Adverse and Resilient Experiences (ICARE) model posits that the negative consequences of ACEs result from biological and behavioral adaptations to adversity that alter cognitive, social, and emotional development. These adaptations often have negative consequences in adulthood and may be transmitted to subsequent generations through epigenetic changes as well as behavioral and environmental pathways. The ICARE model also incorporates decades of resilience research documenting the power of protective relationships and contextual resources in mitigating the effects of ACEs. Examples of interventions are provided that illustrate the importance of targeting the dysregulated biobehavioral adaptations to ACEs and developmental impairments as well as resulting problem behaviors and health conditions.

Keywords: Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), Protective and Compensatory Experiences (PACEs), adversity, resilience, biobehavioral adaptations to stress

The robust effects of child maltreatment and family dysfunction on the health and behavior of thousands of adult patients who participated in the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) study generated renewed interest in the processes by which early life adversity exerts negative consequences many decades later (Anda et al., 2006; Felitti et al., 1998; Hillis et al., 2001; Rutter, 1979; Sameroff, Seifer, Baldwin & Baldwin, 1993). This pattern of results is remarkably consistent across continents and cultures (Bellis, Hughes, Ford, Rodrigues, Sethi, & Passmore, 2019). Research in animal models (Blaze & Roth, 2017) and in humans reliably reveals predictable neurobiological, epigenetic, and behavioral responses to early life stress and trauma (Danese & Lewis, 2017; Teicher & Samson, 2016). Neuroscience and epigenetic research has identified specific biological processes engaged during the struggle to survive and adapt to threatening, neglecting, and harmful environments. In addition, psychological and developmental research have identified a number of specific protective experiences that mitigate the effects of childhood adversity, promoting resilience and recovery throughout the lifespan (Luthar, Cicchetti & Becker, 2000; Masten, 2001). What has yet to emerge, however, is a compressive and integrative model that encompasses the short-term neurobiological and behavioral stress responses that promote immediate survival but impair developmental systems and threaten long-term positive adaptations. Such an integrative model is needed to develop and implement interventions that address and treat the often unobserved but meaningful neurobiological effects of ACEs as well as the observed behavioral and health effects of childhood maltreatment and family dysfunction.

Developmental psychology has a rich history of examining risk and resilience processes in an attempt to understand why and how children who experience adversity thrive despite their circumstances (Masten, 2015; Masten, Best, & Garmezy, 1990; Rutter, 1987). Indeed, it was more than four decades ago that Sameroff (1975) described development as a cycle of transactions between parents and infants. Transactions were affected by a caregiver’s beliefs and child characteristics, and subsequent transactions (i.e., social interactions) affected future transactions due to past behaviors and expectations. Ecological models of development (e.g., Bronfenbrenner, 1975) take into account the broader social environment (i.e., macrosystem, exosystem, and microsystem) in order to explain individual development that occurs within ecological systems. Researchers such as Cicchetti (e.g., Cicchetti, Toth, & Maughan, 2000) and Luthar (e.g., Luthar, Crossman, & Small 2015) have integrated ecological and individual models of development to describe adaptive and maladaptive pathways of maltreated and resilient children.

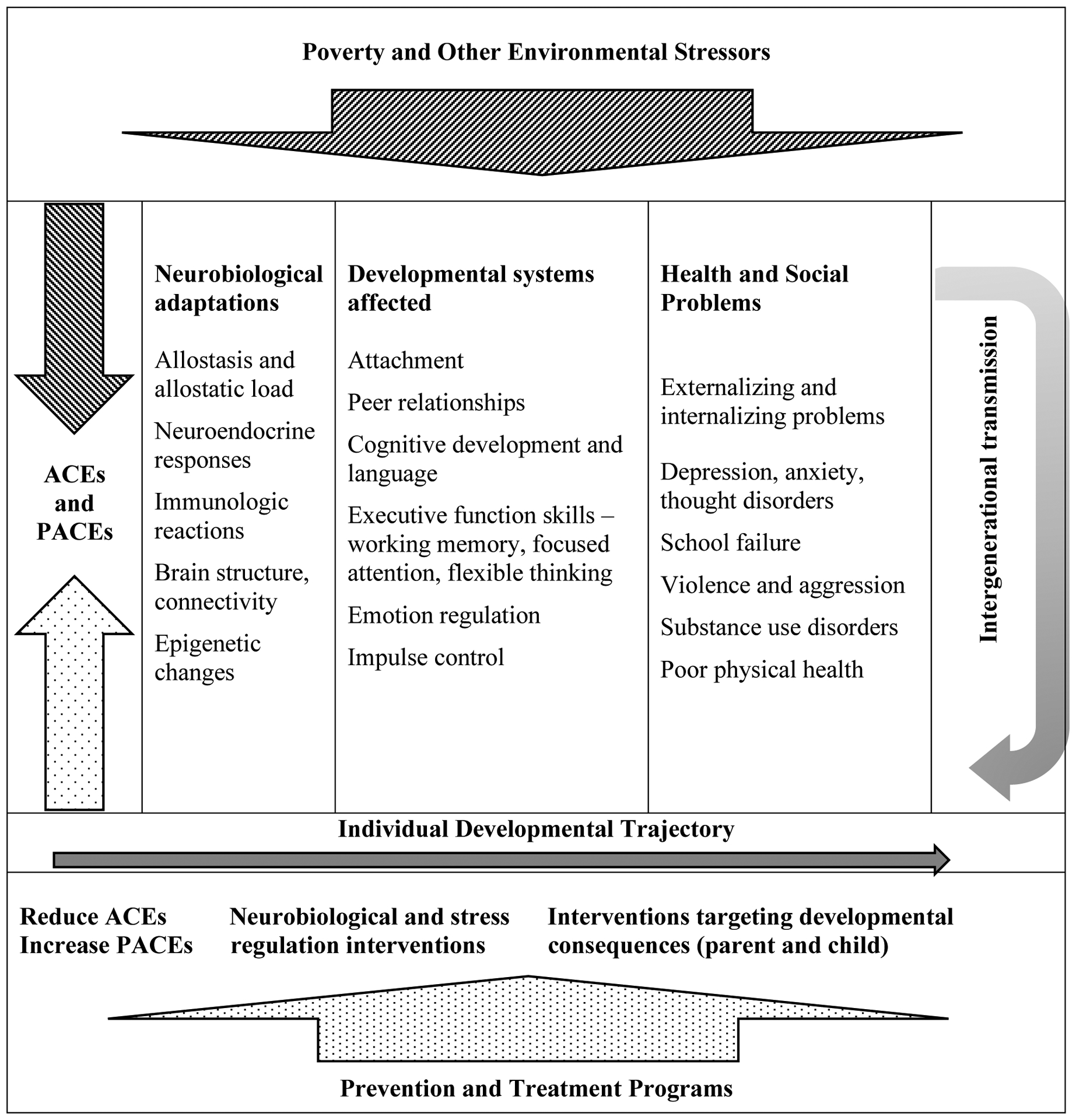

Since these seminal models were developed, studies from neuroscience, epigenetics, and immunology have provided more detailed evidence about the ways that social relationships and biological processes interact. In their recent review of research on adverse and protective childhood experiences, Hays-Grudo and Morris proposed an integrative model that accounts for the effects of ACEs on subsequent health and development via resulting neurobiological adaptations to adversity, cognitive, affective and social developmental consequences, resulting in increased likelihood of poor self-regulation and control, mental and physical health problems, and intergenerational transmission (see Figure 1; adapted from Hays-Grudo & Morris, 2020). The Intergenerational and Cumulative Adverse and Resilient Experiences (ICARE) model also accounts for the neurobiological effects of positive social relationships and resilience-promoting resources throughout developmental stages, suggesting appropriate neurobiological as well as behavioral targets for intervention and prevention. The ICARE model extends developmental models focused on adversity and resilience in three primary ways: 1) it is informed by research on the full range of ACEs, i.e., the primary types of child maltreatment as well as the major sources of family dysfunction as well as research on resilience; 2) it acknowledges the dynamic interplay between social context and development via neurobiological adaptations to stress and adversity as well as the neurobiology of love and attachment; and 3) it includes a focus on intergenerational transmission of adversity, grounded in epigenetic as well as behavioral research from both animal and human studies. The model provides a framework for understanding the biobehavioral adaptations linking ACEs to later maladaptive outcomes and for developing more effective treatment and prevention strategies.

Figure 1. Intergenerational and Cumulative Adverse and Resilient Experiences (ICARE).

Adapted from Hays-Grudo and Morris (2020).

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

ACEs were first identified as predictive of poor adult physical and mental health when researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention analyzed detailed health records from more than 17,000 enrollees in the Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program in southern California. The ten categories identified included measures of physical, emotional, and sexual abuse, physical and emotional neglect, and household dysfunction (divorce, domestic violence, and household mental illness, criminality, and substance abuse). Importantly, ACEs were defined as experiences occurring prior to age 18, so they include experiences throughout childhood and adolescence. The results initially surprised the medical community in that ACEs were common, with two-thirds of the largely middle-class and middle-aged sample reporting at least one ACE, tended to co-occur (Dong et al., 2004), and predicted later health and behavior problems in a cumulative, or dose-response manner (Anda et al., 2006; Hillis et al., 2001). Subsequent research has replicated the prevalence and predictive relationship between ACEs, health-harming behavior, and poor health outcomes in larger and more diverse U.S. samples (Merrick, Ford, Ports & Guinne, 2018) and in other countries (Bellis et al., 2013).

ACEs have even higher prevalence rates among populations with less education or income levels and in socially marginalized groups (Baglivio et al., 2014; Merrick, et al., 2018; Wade, Shea, Rubin, & Wood, 2014). Among U.S. children, it has been estimated that 20 to 48% have experienced multiple ACEs (Bethell, Newacheck, Hawes, & Halfon, 2014). As with adults, children living in poverty are more likely to be exposed to ACEs (McKelvey, Edge, Mesman, Whiteside-Mansell, & Bradley, 2018), as are children and youth in the child welfare (Clarkson Freeman, 2014) and juvenile justice systems (Baglivio et al., 2014). ACEs have also been associated with developmental, social, and behavioral delays in youth (Bethell et al., 2014) and very young children (McKelvey et al., 2018).

Neurobiological Adaptations to Adversity

Research on early life stress in both animals and humans provides evidence that ACEs result in neurobiological, developmental, and behavioral adaptations that have immediate and long-term consequences for individuals, society, and future generations. When adverse experiences are more prevalent or intense than can be mitigated by protective and compensatory experiences, evolutionary programming activates multiple stress response systems that maximize immediate survival. One of the models describing the negative effects of prolonged stress responses was first described as “allostatic load,” the cumulative “wear and tear on the body and brain resulting from prolonged activation of stress-response systems that are normally used in brief, crisis-response type situations (McEwen, 1998; 2003, p. 37). Allostatic load provides an explanatory model for the effects of repeated stress on neuroendocrine responses (Bruce, Gunnar, Pears, & Fisher, 2013), immune function and inflammation (Slopen, Kubzansky, McLaughlin, & Koenen, 2013), and metabolic functioning (Maniam, Antoniadis, & Morris, 2014). Sufficient evidence exists to state that childhood stress may become biologically embedded, the process by which adversity systematically alters biological and developmental states, resulting in stable or long-term differences affecting health, well-being, learning, or behavior (Hertzman, 2012; Miller, Chen & Parker, 2011).

While stress dysregulation describe one pathway by which ACEs influence health and development, other mechanisms are also at work, including brain connectivity and functioning (Pechtel & Pizzagalli, 2011). A recent extensive review of the literature on the neurobiological effects of childhood maltreatment concluded that childhood adversity has consistent, negative effects on both structural and functional brain development and that different types of abuse selectively target different neural pathways and sensory systems (Teicher & Samson; 2016). Brain regions most likely to be affected by childhood stress include the hippocampus, the amygdala, and the prefrontal cortex. Because the hippocampus is densely populated with glucocorticoid receptors, it is susceptible to damage from excess levels of such stress hormones as cortisol (Sapolsky, Krey, & McEwen, 1985; Teicher & Samson, 2016). The amygdala is also susceptible to early exposure to adversity, with a number of studies documenting an association between maltreatment and heightened amygdala responses to threat and diminished responses to reward (Fareri & Tottenham, 2016). Specific regions in the prefrontal cortex important in emotion regulation and decision-making are also negatively impacted by childhood adversity, including the inferior frontal gyrus, an important region in emotion regulation and impulse control which affects both internalizing and externalizing problems (Barch, Belden, Tillman, Whalen, & Luby; 2018; Luby, Barch, Whalen, Tillman, & Belden, 2017).

Developmental scientists have long considered the importance of critical or sensitive periods of development (Scott, 1962), and with advances in neurological development these concepts are increasing interest. Most research on children points to sensitive rather than critical periods of development because critical periods traditionally have been defined as abrupt periods where development will not occur if the window closes, whereas sensitive periods are more gradual with experiences having a greater impact on a developmental phenomena. Research indicates that the effects of adversity may be influenced by the timing of exposure during brain development (Anderson, 2003; Lupien, McEwen, Gunnar, & Heim, 2009). Normative brain development is thought to follow a process of “experience-expectant” development, whereby there are periods where particular brain structures may be more sensitive to environmental signals, both positive and negative, as a means of guiding development and adapting to environmental conditions (Anderson, 2003; Bick & Nelson, 2016).

Epigenetic responses to ACEs are another pathway through which childhood trauma has enduring biobehavioral effects throughout the lifespan and even into subsequent generations (Groger et al., 2016). Much of the research on epigenetic responses to trauma has focused on DNA methylation, a process that occurs when chemical compounds, such as methyl groups, are attached to parts of the DNA strands, making it more difficult to be read and transcribed into RNA (Lester, Conradt, & Marsit, 2016). Genes related to the production of glucocorticoid receptors (GR) and brain plasticity (BDNF) have been found to be highly sensitive to disruptions in maternal care in animal models (Blaze & Roth, 2017). In numerous animal studies, creating stressful conditions for the mother (e.g., having inadequate nesting materials) increases abusive or neglecting care of the young and results in epigenetic changes associated with dysregulated stress responses and maladaptive behavior in the adult offspring (Weaver et al., 2004). Other studies have documented epigenetic and corresponding behavioral responses in several generations of rodent offspring following adversity in the first generation (Franklin et al., 2010). In research with humans, prenatal exposure to maternal depression has been linked to DNA methylation of the GR gene (NR3C1) in newborns and cortisol reactivity at 3 months (Oberlander et al., 2008). Methylation of this gene has also been linked with impaired infant self-regulation (Conradt et al., 2015), with early childhood stress exposure in preschool-aged children (Tyrka et al., 2015), and with childhood maltreatment in adults (Perroud et al., 2011).

Developmental Systems Affected by ACEs

Neurobiological adaptations to stress and adversity lead to a series of developmental changes, or developmental cascades, that affect a host of social, emotional, and cognitive systems (Masten & Cicchetti, 2010). One of the most negatively affected systems in early development is the attachment system, the way in which individuals view their social world and relationships. Secure attachment develops during the first year of life when the infant’s needs are consistently met. A mental model begins to develop in which the world is experienced as a safe and predictable place and caregivers can be trusted (Bowlby, 2008). When abuse and neglect are experienced in early life, working models of attachment develop that are insecure, and the world is seen as an unpredictable place where caregivers are inconsistent and untrustworthy (Bowlby, 1969). This may result in subsequent behavioral and mental health problems and harsh parenting in adulthood (Lomanowska, Boivin, Hertzman, & Fleming, 2017).

Patterns of attachment can be carried into adolescence and adulthood. Insecure patterns of attachment and related behaviors are often evident in negative peer relationships and romantic relationships (Fraley & Shaver, 2000). Indeed, there is now biological evidence to support the premise that attachment in humans is biologically programmed through the influence of hormones such as dopamine and oxytocin on brain regions involved in reward and relationship experiences (Feldman, 2017). Human attachment can be characterized by the coupling of physiological and behavioral systems during social interaction, as evidenced by behavioral synchrony, physiological attunement of heart rate and hormones, and even brain synchrony. Such coupling promotes attachment and social interaction, and when these systems are disrupted due to ACEs, physiological and social systems are negatively affected resulting in social difficulties and increased risk for mental health problems and substance abuse disorders (Strathearn, et al, 2019; Toepfer et al., 2017).

Insecure attachment and impaired stress-response systems also result in emotion regulation difficulties (Young & Widom, 2014). Children and adolescents who experience the world as unsafe and unpredictable often have heightened distress reactions, or alternatively, may experience a blunted emotional response during stressful situations, and this response is likely to minimize social attention and interaction. Over time, these patterns of emotion dysregulation affect social and emotional development and can result in a number of mental health and social problems (Morris et al., 2013).

In addition to social and emotional systems, cognitive and executive function systems are also affected by early life stress. Specifically, executive function skills such as working memory, inhibitory control, and focused attention are affected by early life experiences and ACEs (Deater-Deckard, 2014). Difficulties in executive function may result from ACEs that occur during key developmental periods when the prefrontal cortex is developing higher order cognitive processes such as self-regulation, empathy, and attentional control. Such difficulties can result in school problems and other learning difficulties that impair adult workforce training and success (Pechtel & Pizzagalli, 2011).

Health and Social Problems and Intergenerational Transmission

As described previously, system-wide stress responses that are adaptive for situations requiring immediate reactions for survival can have negative long-term effects on stress regulation systems and brain development. These in turn may impair cognitive, social, and emotional development, setting the stage for subsequent learning difficulties, behavior problems, school failure, inadequate occupational preparation and earnings potential, poor adult relationships and parenting behaviors, and poor adult coping skills. They increase the risk of adopting health-harming behaviors in an attempt to regulate perceived stress, aggressive or avoidant responses to conflict, and lead to mental health problems such as depression and anxiety. Thus, parents with a history of adversity may unwittingly increase the risk of ACEs for their own children indirectly through the consequences of ACEs in their own lives and negative parenting, as well as directly through transgenerational epigenetic changes to genes involved in stress regulation and synapse repair (Conradt et al. 2016).

Stressors and Negative Environments

An important element of the ICARE model is the role of contextual and environmental stressors on children at risk for ACEs. Developmental scientists have relied upon models incorporating layers of environmental influences at least since Bronfenbrenner’s seminal work in the 1970s (Bronfenbrenner, 1977). Although ACEs are experienced by children in all income levels, they are more concentrated among those in poverty for a variety of reasons (Coulton, Crampton, Irwin, Spilsbury, & Korbin, 2007). Poverty limits access to resources such as healthcare, highlights discrimination and segregation in neighborhoods and schools, and is associated with decaying and dangerous physical environments. Individuals living in high-poverty neighborhoods have substantially higher levels of depression (Cutrona et al., 2006), obesity and health problems (Burdette & Hill, 2008), infant mortality, low birth weight, teen childbearing, low educational attainment, adolescent delinquency, homicide, and suicide (Sampson et al., 2002). Many of the adversities that shape developmental outcomes are more common in low-income neighborhoods where parents have less access to protective resources (Harris et al., 2011). Family poverty puts stress on parents, making it more difficult for parents to be responsive with their children (Evans et al., 2011) and are more likely to engage in harsher punishments (Evans & Kim, 2013).

Mitigating the Effects of ACEs in Children

Thus far, our discussion of the model has covered the adverse experiences and environments that induce neurobiological adaptations that hinder cognitive, social, and emotional development, increasing the risk of psychological maladjustment, health-harming behaviors, and poor physical health. However, not all children exposed to ACEs experience poor health and developmental outcomes, as evidenced by the results of decades of research on resilience (Masten, Best, & Garmezy, 1990; Rutter, 1987; Werner & Smith, 1992). Defining resilience as “the capacity to adapt successfully to disturbances that threaten function, viability, or development” (p. 10, Masten, 2014), two conditions must be met in order for resilience to occur: exposure to threat or severe adversity and positive adaptation (Luthar, Cicchetti & Becker, 2000). The ICARE model also encompasses the neurobiological and behavioral effects of protective experiences that promote resilience.

Protective and Compensatory Experiences (PACEs)

Based on an extensive review of the resilience literature, Morris and Hays-Grudo identified ten protective and compensatory experiences (PACEs) that mitigate the effects of ACEs (Morris et al., 2018) and are modifiable and amenable to intervention (Masten, 2014). PACEs consist of two types of protective factors, relationships and resources that, like ACEs, are experienced prior to age 18. Relationship factors include unconditional love from a caregiver, having a best friend, being part of a social group, having a mentor, and volunteering in the community. Resource factors include having a home that is safe and clean with enough food, going to a good school/quality education, having a hobby, getting regular physical activity alone or in organized sports, and having family routines and consistent rules. Designed to be administered with the 10-item ACEs questionnaire, the 10-item PACEs appears to be a reliable and valid assessment of protective experiences and reduce harsh parenting in adults with ACEs (Hays-Grudo & Morris, 2020)).

The first PACE is unconditional love from a parent or primary caregiver. Children who perceive that love is not provisional based on behavior and performance have less internalizing and externalizing problems (Barber, 2002). For children who have already experienced ACEs, responsive and sensitive caregiving can foster and promote healing (Dozier, Lindhiem, & Ackerman, 2005). Other social relationships, such as having a best friend or a trusted adult mentor, provide support and protection during times of stress (Lerner et al., 2014). Authoritative parenting, i.e., having high expectations and clear rules along with responsive and caring communication (Baumrind, 1971; Steinberg, Lamborn, Dornbusch, & Darling, 1992) is also associated with secure attachment and positive outcomes and reflects the PACE of having consistent and fair rules and family rituals and routines. Being part of a group, having a hobby (Zarobe & Bungay, 2017), and volunteering in the community (Eisenberg, Morris, McDaniel, & Spinrad, 2009) are experiences that promote identity and moral development. In addition to positive relationships and developmentally enriching experiences, children are protected from adversity when their environments meet their basic needs for safety, nutrition, physical activity, and sleep (Becker, McClelland, Loprinzi, & Trost, 2014). Opportunities for quality educational experiences are also key to successful development and can protect against early adversity (Pecora et al., 2017).

One consideration in studying PACEs is the relative importance of each of the items. Drawing from previous research, the primacy of unconditional love, secure attachment, and having warm, nurturing relationships during childhood and adolescence is well established as a primary protective factor (Ainsworth, 1989; Baumrind, 1971; Bowlby, 2008; Steinberg et al., 1992), but individual children may benefit from having a variety of supportive relationships and opportunities for development. Another consideration is that many elements of resilience-promoting experiences and environments are not under the direct control of individual behavioral scientists and psychologists. Communities vary in their capacity and willingness to provide for good schools, sports and recreation, and opportunities to cultivate skills and hobbies, and access is restricted to these resources for many of the children most at risk. Negative attitudes toward public investment in children have negative consequences for individual children as well as society at large (Morris, Hays-Grudo, Kerr, & Beasley, in press; Ziglar, 1975). Psychologists, individually and collectively, can be advocates for change by working with local, state, and national and policy makers to influence change based on emerging data on adversity and resilience science (Bellis, et al., 2019; Hays-Grudo, 2020) as well as established knowledge and recommendations from recognized experts (National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine, 2019). Other opportunities for psychologists to influence the quality of the relationships and resources available to children are suggested in the concluding section.

Prevention and Treatment Programs

There are a number of evidence-based interventions to mitigate the effects of adversity experienced by children and families. We propose that the ICARE model is useful in designing and evaluating interventions as it provides more specificity in identifying interrelated targets of change and potential outcomes. For example, reducing exposure to early adversity and increasing protective factors might include home visiting programs that provide social and parenting support for at-risk single mothers, decreasing her perceived stress and social isolation and increasing maternal self-regulation and parenting efficacy, and decreasing the likelihood of the infant’s exposure to harsh or neglecting parenting (e.g., Legacy for Children™). Interventions focused on the neurobiological and epigenetic adaptations to adversity would include programs that have mindfulness-based practices, which are expected to increase self-regulation and associated changes in the brain related to attention, introspection, and emotional processing (Hatchard et al., 2017). Interventions focused on promoting cognitive, social, and emotional development would increase access to high-quality early childhood care and education, and would provide opportunities for learning skills during adolescence. Each of these categories of intervention targets is discussed in the sections that follow.

Reducing Early Adversity and Increasing Protective Factors

Maximizing existing and potential protective factors is critical for promoting resilience among children exposed to significant adversity. Psychologists, school counselors, and other interventionists can use the PACEs questionnaire to identify with families the protective relationships and resources already in place or potentially accessible. When providers use the PACEs questionnaire along with the ACEs screening tool, they are able to bring family strengths into the conversation and help parents and caregivers create goals that build on strengths and target new skills (e.g., bedtime routines, finding opportunities to help others).

Recent research has focused on specific parenting PACEs that have a direct positive impact on families. For example, research using the National Survey of Children’s Health found that the presence of positive parenting practices (PPPs) acted as a buffer to the negative effects of ACES on social/emotional development and developmental delays in children 4 months to 6 years of age (Yamaoka & Bard, 2019). The six PPPs were based on how often in the previous week the caregiver and child (1) read stories, (2) told stories or sang together, (3) ate a meal together, (4) the child played with a peer, (5) went on a family outing, and (6) limited screen time to less than 2 hours per day. Further, the absence of these PPPs were as detrimental to development as were ACEs (Yamaoka & Bard, 2019).

An example of a successful system-wide effort to reduce the effects of adversity by increasing access to protective factors in adolescence is provided by a program conducted by the government of Iceland to reduce substance abuse in youth. In the 1990s, adolescents in Iceland had among the highest levels of alcohol and substance abuse in Europe. In response, the Youth in Iceland Program was designed to increase access to opportunities for sports, hobbies, and positive relationships, providing afterschool activities (i.e., Hip Hop classes, martial arts, rock-climbing), parenting support for caregivers, and policy changes such as curfews for minors and bans on alcohol advertising. After a decade of programming, rates of tobacco, alcohol and marijuana use plummeted, and adolescents reported spending more time with families and in sports. Programs such as these illustrate how policies and programming can come together to ensure greater access to protective experiences for youth and families.

Neurobiological and Stress Regulation Prevention and Intervention Programs

Efforts to improve dysregulated stress response systems begins with establishing safety through the timely reduction or elimination of stress exposure and the strengthening of the caregiver’s capacity to provide a nurturing relationship (Center on the Developing Child, 2017; Luthar & Ciciolla, 2015). The importance of providing support for caregivers was emphasized in a recent consensus study report of a committee on applying neurobiological and socio-behavioral sciences from prenatal through early childhood development convened by the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM; 2019). As highlighted in the report, “the single most important factor” for healthy development in all children is having a “strong, secure attachment to their primary caregivers (NASEM, 2019; p. 4–7). Further, because “effective parenting presupposes the caregivers’ own well-being” it is imperative that caregivers “have the necessary supports for maintaining good mental health and psychological well-being” (NASEM, 2019; p. 4–7). These recommendations reflect a growing consensus that interventions focused on strengthening self-regulation skills and attenuating dysregulated stress responses in parents are most likely to interrupt the intergenerational cycle of ACEs, and these interventions will benefit from attention to the neurobiological adaptations brought about by parents’ own ACEs (Hays-Grudo, Ratliff, & Morris, 2020). Stress attenuation is focused on reducing or countering sympathetic nervous system activation by eliciting the relaxation response and activating the parasympathetic nervous system to return the body to a state of calm. Physiological effects of the parasympathetic nervous system and the relaxation response include a reduction in heart rate, blood pressure, respiration, and oxygen consumption, and an increase in heart rate variability (Franke, 2014).

The relaxation response may be volitionally elicited through a variety of mindfulness-based mind-body (MBMB) approaches, including meditation, Zen, yoga, tai chi, or meditative prayer, diaphragmatic breathing (deep breathing with longer exhalations), mindful awareness, guided imagery, and biofeedback (Bethell, Gombojav, Solloway, & Wissow, 2016). Notably, these practices share a focus on purposeful moment-by-moment presence, awareness of the breath, body sensations, emotions, and thoughts in a nonjudgmental manner, passive disregard for distraction, relaxed positioning, and a quiet environment (Bethell et al., 2016; Franke, 2014). Regular practice of MBMB approaches has been associated with neurobiological changes in immune function, stress reactivity, and cortical function, reductions in stress-related physiological and psychological symptoms, and improvements in stress-related coping and resilience (for review, see Ortiz & Sibinga, 2017).

With regular practice, stress reactivity becomes better controlled and self-regulation in response to stress is enhanced. According to work conducted at the Duke Center for Child and Family Policy for the Administration for Children and Families (ACF) (Rosanbalm & Murray, 2017), self-regulation skills in children are best learned through a process of “co-regulation” with warm, responsive adults (e.g., caregivers, teachers, extended family) who structure the environment to be safe for exploration and learning. When caregivers are able to self-regulate, they can actively coach children in such self-regulation skills as calming down, taking turns, waiting, and solving problems through modeling, developmentally-appropriate instruction, supportive scaffolding, opportunities for practice, and reinforcement in the moment (Rosanbalm & Murray, 2017). Early intervention programs that promote parents’ and children’s self-regulation include Parents as Teachers, Triple P, Incredible Years, Circle of Security, and such home visiting programs as Nurse-Family Partnership and SafeCare.

Therapeutic Interventions Targeting Developmental Consequences of ACEs

A number of evidenced-based interventions have been developed to address more obvious symptoms of neurobiological adaptations to ACEs. These symptoms may include disturbances in sleep, aggression, hyperarousal, poor impulse control, diminished executive functioning (including attentional processes and memory), depressed mood and anxiety, somatic complaints, impaired social relationships, and developmental delay (Purewal et al., 2016). Often they incorporate MBMB approaches and regulatory skill development previously described. For example, trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) includes relaxation and affective modulation skills, in addition to parenting skills, to reduce symptoms of physiological, emotional, and behavioral dysregulation (Cohen & Mannarino, 2012). Integrated Treatment of Complex Trauma (ITCT) also includes components of distress reduction using MBMB approaches and affect regulation training. These interventions focus on the review and reappraisal of trauma memories, with therapeutic benefit stemming from repeated experiences of physiological, emotional, and behavioral regulation when engaging with distressing memories (Cloitre et al., 2012).

Other evidence-based approaches that focus on reducing developmental consequences of physiological, emotional, and behavioral dysregulation through attenuation of the stress response and self-regulation skills include Attachment, Regulation, & Competency (ARC; Blaustein & Kinniburgh, 2010), Trauma Affect Regulation: Guide for Education and Therapy (TARGET; Ford & Hawke, 2012), and Structured Psychotherapy for Adolescents Responding to Chronic Stress (SPARCS; DeRosa & Pelcovitz, 2006). It is important to note that for all therapeutic interventions for children, caregiver involvement in therapy is a key component of treatment that serves to enhance the caregiving relationship, build caregiver capacity for co-regulation, foster stability in the home, and support ongoing skill development and enhance coping.

Evidence-based interventions incorporate somatic elements that promote interoceptive awareness of, attunement to, and skills for shifting physiological arousal in order to build self-regulatory capacity (Perry, 2009; Van der Kolk, 2014). Interventions that use repetitive somatosensory activities to provide patterned neural activation helps to reorganize the “lower” neural systems responsible for self-regulation, attention, arousal, and impulsivity (Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics; Perry, 2009). Examples of somatic approaches include movement- or rhythm-based activities such as dance, drumming, music, repetitive exercises (e.g., yoga, tai chi, trampoline) and sports. More formalized somatic approaches with promising evidence for decreasing stress reactivity and increasing self-regulation include Trauma-Sensitive Yoga (Emerson & Hopper, 2011), Sensory Integration Occupational Therapy (SI-OT; Ayres, 2004), and Sensory Motor Arousal Regulation Treatment (SMART; Warner, Cook, Westcott, & Koomar, 2011), which uses therapeutic equipment (e.g., weighted blankets, fitness balls) and shared play to regulate physiological and emotional arousal, facilitate attachment, and allow for embodied processing of traumatic experiences (Warner et al., 2014).

Finally, there are a number of evidence-based therapies for infants and young children that use play-based activities (i.e., serve and return, imaginative play) to enhance children’s developing biobehavioral and regulatory capabilities through supported co-regulatory experiences. These include Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT; Eyeberg et al., 2001), Attachment & Biobehavioral Catchup (ABC; Dozier, Lindhiem, & Ackerman, 2005), and Child-Parent Psychotherapy (CPP; Lieberman, Ghosh Ippen, & Van Horn, 2015), the latter of which also includes a trauma narrative component. These therapeutic interventions support caregiver regulatory capacity and/or skill development as the primary mode of treatment delivery that aims to strengthen the caregiver-child relationship and foster co-regulated, adaptive behavior.

Knowledge to Action

As noted by other psychological researchers, there is sufficient evidence now to recommend well-defined processes that can be targeted for change at individual and systems levels by practitioners, pediatricians, educators, and policy makers (Luthar & Eisenberg, 2017; Sunstein, 2015). A recent special issue of Child Development on evidence-based interventions for at-risk youth and families highlighted a wide array of interventions that can be implemented to benefit children growing up in adverse environments (Luthar & Eisenberg, 2017). Two essential elements were consistently found among programs that increase children’s ability to survive and thrive in the face of adversity: support for the psychological, and emotional support for caregivers, and interventions to address specific dysfunctional parenting behaviors. These recommendations are consistent with the long-standing recommendations from researchers and practitioners in the field of infant mental health, with it s focus on nonjudgmental and emotionally warm support for new parents struggling to identify and lay to rest the “ghosts in the nursery” that hinder the development of secure attachments with their own infants and young children (Hays-Grudo, Ratliff, & Morris, 2020; Fitzgerald, Weatherston, & Mann, 2011; Fraiberg, Adelson, & Shapiro, 1975).

The NASEM (2019) consensus study also identified evidence-based programs across a number of service sectors to reduce inequities in children’s health and development For example, pediatricians are increasingly using modified versions of the CDC ACEs questionnaire to identify the role of adversity in stress-related somatic and behavioral issues in their patients (Burke, Hellman, Scott, Weems, & Carrion, 2011). Pediatricians can also help parents identify and implement PACEs that support both health and development (nutrition, sleep routines, referrals for appropriate therapists as needed). Other disciplines, including early childhood care, Pre-K to 12 education, social work, public health, and child welfare, are embracing the importance of addressing the underlying neurobiological adaptations to ACEs through the provision of trauma-informed programs (Leitch, 2017).

The ICARE model provides a framework for conceptualizing the various types of interventions needed to reduce the impact of ACEs on children, families, and communities, ensuring that the neurobiological and developmental systems, developmental deficits, and subsequent behavioral symptoms are adequately addressed. It suggests new opportunities to design and implement multi-level prevention and intervention programs across the various pathways by which adverse and protective experiences influence outcomes. Prevention strategies focused on PACEs gives treatment providers and policy makers information to strengthen families by supporting protective factors that are already in place and encouraging new behaviors, activities, and programs that can make the family and other systems of care stronger. This framework allows a treatment provider to go beyond interventions that decrease maladaptive behaviors so that dysregulated stress response systems may be reoriented, creating new neural pathways linking autonomic stress responses to higher cortical functions, and allowing more intentional and health-supporting behavior patterns to be acquired (Hatchard et al., 2017). Thus, the ICARE model serves as a comprehensive framework for understanding the impact of ACEs and PACEs on neurobiological, cognitive, social and emotional development, and suggests more comprehensive and coordinated targets for prevention and intervention programs to promote resilience within individuals, communities, and future generations.

Public Significance:

We propose that ACEs are best prevented and treated by recognizing and addressing the neurobiological and behavioral adaptations to childhood adversity. Short-term stress responses to ACEs have negative effects on development, increasing the risk for health-harming behavior, difficulties with adult relationships and parenting, and mental health problems. Interventions that address dysregulated stress, promote self-regulation, and provide support for parents have the greatest potential for interrupting the intergenerational transmission of ACEs and promoting resilience and recovery in adults and children.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P20GM109097. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Jennifer Hays-Grudo, Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences.

Amanda Sheffield Morris, Oklahoma State University – Tulsa.

Lana Beasley, Oklahoma State University.

Lucia Ciciolla, Oklahoma State University.

Karina Shreffler, Oklahoma State University – Tulsa.

Julie Croff, Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences.

References

- Ainsworth MS (1989). Attachments beyond infancy. American Psychologist, 44(4), 709–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, Walker JD, Whitfield C, Perry BD, … Giles WH (2006). The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 256(3), 174–186. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson LM, Shinn C, Fullilove MT, Scrimshaw SC, Fielding JE, Normand J, … & Task Force on Community Preventive Services. (2003). The effectiveness of early childhood development programs: A systematic review. American journal of preventive medicine, 24(3), 32–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baglivio MT, Epps N, Swartz K, Huq MS, Sheer A, & Hardt NS (2014). The prevalence of adverse childhood experiences (ACE) in the lives of juvenile offenders. Journal of Juvenile Justice, 3(2), 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK (2002). Intrusive parenting: How psychological control affects children and adolescents: Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Barch DM, Belden AC, Tillman R, Whalen D, & Luby JL (2018). Early childhood adverse experiences, inferior frontal gyrus connectivity, and the trajectory of externalizing psychopathology. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 57(3), 183–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D (1971). Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology, 4(1 Pt.2), 1–103. 10.1037/h0030372 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becker DR, McClelland MM, Loprinzi P, & Trost SG (2014). Physical activity, self-regulation, and early academic achievement in preschool children. Early Education & Development, 25(1), 56–70. [Google Scholar]

- Bellis MA, Hughes K, Ford K, Rodriguez GR, Sethi D, & Passmore J (2019). Life course health consequences and associated annual costs of adverse childhood experiences across Europe and North America: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 4(10), e517–e528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellis MA, Lowey H, Leckenby N, Hughes K, & Harrison D (2013). Adverse childhood experiences: Retrospective study to determine their impact on adult health behaviours and health outcomes in a UK population. Journal of Public Health, 36(1), 81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethell CD, Newacheck P, Hawes E, & Halfon N (2014). Adverse childhood experiences: Assessing the impact on health and school engagement and the mitigating role of resilience. Health Affairs, 33(12), 2106–2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethell C, Gombojav N, Solloway M, & Wissow LS (2016). Adverse childhood experiences, resilience and mindfulness-based approaches: Common denominator issues for children with emotional, mental, or behavioral problems. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 25(2), 139–156. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2015.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bick J, & Nelson CA (2016). Early adverse experiences and the developing brain. Neuropsychopharmacology, 41(1), 177–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaustein M, & Kinniburgh K (2010). Treating traumatic stress in children and adolescents: How to foster resilience through attachment, self-regulation, and competency. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blaze J, & Roth TL (2017). Caregiver maltreatment causes altered neuronal DNA methylation in female rodents. Development and psychopathology, 29(2), 477–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J (1969). Attachment (Vol. 1). New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J (2008). A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development (Reprint, 1988 ed.). New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32(7), 513. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce J, Gunnar MR, Pears KC, & Fisher PA (2013). Early adverse care, stress neurobiology, and prevention science: Lessons learned. Prevention Science, 14(3), 247–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdette AM, & Hill TD (2008). An examination of processes linking perceived neighborhood disorder and obesity. Social science & medicine, 67(1), 38–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke NJ, Hellman JL, Scott BG, Weems CF, & Carrion VG (2011). The impact of adverse childhood experiences on an urban pediatric population. Child Abuse & Neglect, 35(6), 408–413. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center on the Developing Child (2017). Three Principles to Improve Outcomes for Children and Families. Retrieved from https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/three-early-childhood-development-principles-improve-child-family-outcomes/

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL, & Maughan A (2000). An ecological–transactional model of child maltreatment. In Handbook of developmental psychopathology (pp. 689–722). Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson Freeman PA (2014). Prevalence and relationship between adverse childhood experiences and child behavior among young children. Infant Mental Health Journal, 35(6), 544–554. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Petkova E, Wang J, & Lu F (2012). An examination of the influence of a sequential treatment on the course and impact of dissociation among women with PTSD related to childhood abuse. Depression and Anxiety, 29(8), 709–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, & Deblinger E (Eds.). (2012). Trauma-focused CBT for children and adolescents: Treatment applications. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coulton CJ, Crampton DS, Irwin M, Spilsbury JC, & Korbin JE (2007). How neighborhoods influence child maltreatment: A review of the literature and alternative pathways. Child abuse & neglect, 31(11–12), 1117–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conradt E, Fei M, LaGasse L, Tronick E, Guerin D, Gorman D, … Lester BM (2015). Prenatal predictors of infant self-regulation: The contributions of placental DNA methylation of nr3c1 and neuroendocrine activity. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 9, 130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conradt E, Hawes K, Guerin D, Armstrong DA, Marsit CJ, Tronick E, & Lester BM (2016). The contributions of maternal sensitivity and maternal depressive symptoms to epigenetic processes and neuroendocrine functioning. Child Development, 87(1), 73–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Wallace G, & Wesner KA (2006). Neighborhood characteristics and depression: An examination of stress processes. Current directions in psychological science, 15(4), 188–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danese A, & Lewis SJ (2017). Psychoneuroimmunology of early-life stress: the hidden wounds of childhood trauma? Neuropsychopharmacology, 42(1), 99–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K (2014). Family matters: Intergenerational and interpersonal processes of executive function and attentive behavior. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(3), 230–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRosa R, & Pelcovitz D (2006). Treating traumatized adolescent mothers: A structured approach. In Webb N (Ed.), Working with traumatized youth in child welfare (pp. 219–245). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dong M, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Williamson DF, Thompson TJ, … Giles WH (2004). The interrelatedness of multiple forms of childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. Child Abuse & Neglect, 28(7), 771–784. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozier M, Lindhiem O, & Ackerman J (2005). Attachment and biobehavioral catch-up. In Berlin L, Ziv Y, Amaya-Jackson L, & Greenberg MT (Eds.), Enhancing early attachments. New York: Guilford; (pp. 178–194). [Google Scholar]

- Emerson D, & Hopper E (2011). Overcoming trauma through yoga. San Francisco: North Atlantic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Morris AS, McDaniel B, & Spinrad TL (2009). Moral cognitions and prosocial responding in adolescence. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology, 1, 229–265. [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, Brooks-Gunn J, & Klebanov PK (2011). Stressing out the poor. Pathways, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, & Kim P (2013). Childhood poverty, chronic stress, self-regulation, and coping. Child development perspectives, 7(1), 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Fareri DS, & Tottenham N (2016). Effects of early life stress on amygdala and striatal development. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 19, 233–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R (2017). The neurobiology of human attachments. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 21(2), 80–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Koss M, & Marks JS (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald HE, Weatherston D, & Mann TL (2011). Infant mental health: An interdisciplinary framework for early social and emotional development. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care, 41(7), 178–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke H (2014). Toxic stress: Effects, prevention, and treatment. Children, 1(3),390–402. doi: 10.3390/children [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, & Shaver PR (2000). Adult romantic attachment: Theoretical developments, emerging controversies, and unanswered questions. Review of General Psychology, 4(2), 132. [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, & Hawke J (2012). Trauma affect regulation psychoeducation group and milieu intervention outcomes in juvenile detention facilities. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 21(4), 365–384. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2012.673538. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin TB, Russig H, Weiss IC, Gräff J, Linder N, Michalon A, … Mansuy IM (2010). Epigenetic transmission of the impact of early stress across generations. Biological Psychiatry, 68(5), 408–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groger N, Matas E, Gos T, Lesse A, Poeggel G, Braun K, & Bock J (2016). The transgenerational transmission of childhood adversity: Behavioral, cellular, and epigenetic correlates. Journal of Neural Transmission (Vienna), 123(9), 1037–1052. doi: 10.1007/s00702-016-1570-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatchard T, Mioduszewski O, Zambrana A, O’Farrell E, Caluyong M, Poulin PA, & Smith AM (2017). Neural changes associated with mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR): Current knowledge, limitations, and future directions. Psychology & Neuroscience, 10(1), 41. [Google Scholar]

- Hays-Grudo J (2020). Inaugural editorial. Adversity and Resilience Science, 1, 1–4. 10.1007/s42844-020-00006-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays-Grudo J, Ratliff E, & Morris AM (2020). Adverse childhood experiences: A new framework for infant mental health. In Benson J (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Infant and Early Childhood Development (2nd Ed.), Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Hays-Grudo J & Morris AS (2020). Adverse and protective experiences: A developmental perspective. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Hertzman C (2012). Putting the concept of biological embedding in historical perspective. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(Supplement 2), 17160–17167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis SD, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, & Marchbanks PA (2001). Adverse childhood experiences and sexual risk behaviors in women: A retrospective cohort study. Family Planning Perspectives, 206–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitch L (2017). Action steps using ACEs and trauma-informed care: A resilience model. Health and Justice, 5, 5, DOI 10.1186/s40352-017-0050-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner RM, Wang J, Chase PA, Gutierrez AS, Harris EM, Rubin RO, & Yalin C (2014). Using relational developmental systems theory to link program goals, activities, and outcomes: The sample case of the 4-H study of positive youth development. New Directions for Youth Development, 2014(144), 17–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester BM, Conradt E, & Marsit C (2016). Introduction to the special section on epigenetics. Child Development, 87(1), 29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman AF, Ghosh Ippen C, & Van Horn P (2015). Don’t hit my mommy: A manual for child parent psychotherapy with young witnesses of family violence. Washington, D.C.: Zero to Three Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lomanowska A, Boivin M, Hertzman C, & Fleming AS (2017). Parenting begets parenting: A neurobiological perspective on early adversity and the transmission of parenting styles across generations. Neuroscience, 342, 120–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luby JL, Barch D, Whalen D, Tillman R, & Belden A (2017). Association between early life adversity and risk for poor emotional and physical health in adolescence: A putative mechanistic neurodevelopmental pathway. The Journal of the American Medical Association Pediatrics, 171(12), 1168–1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupien SJ, King S, Meaney MJ, & McEwen BS (2001). Can poverty get under your skin? Basal cortisol levels and cognitive function in children from low and high socioeconomic status. Development and Psychopathology, 13(3), 653–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, & Ciciolla L (2015). Who mothers mommy? Factors that contribute to mothers’ well-being. Developmental Psychology, 51(12), 1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, & Eisenberg N (2017). Resilient adaptation among at-risk children: Harnessing science toward maximizing salutary environments. Child development, 88(2), 337–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Cicchetti D & Becker B (2000). The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development, 71, 3, 543–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Crossman EJ, & Small PJ (2015). Resilience and adversity. Handbook of child psychology and developmental science, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Maniam J, Antoniadis C, & Morris MJ (2014). Early-life stress, HPA axis adaptation, and mechanisms contributing to later health outcomes. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 5, 73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Best KM, & Garmezy N (1990). Resilience and development: Contributions from the study of children who overcome adversity. Development and Psychopathology, 2(4), 425–444. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, & Cicchetti D (2010). Developmental cascades. Development and Psychopathology, 22(3), 491–495. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS (2014). Global perspectives on resilience in children and youth. Child Development, 85(1), 6–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56(3), 227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. (1998). Stress, adaptation, and disease. Allostasis and allostatic load. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 840, 33–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS (2003). Interacting mediators of allostasis and allostatic load: Towards an understanding of resilience in aging. Metabolism, 52, 10–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKelvey LM, Edge NC, Mesman GR, Whiteside-Mansell L, & Bradley RH (2018). Adverse experiences in infancy and toddlerhood: Relations to adaptive behavior and academic status in middle childhood. Child Abuse & Neglect, 82, 168–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrick MT, Ford DC, Ports KA, & Guinn AS (2018). Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences from the 2011–2014 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System in 23 states. Journal of the American Medical Association Pediatrics. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milkman HB (2016). Iceland succeeds at reversing teenage substance abuse. The World Post, Huffpost. [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Chen E, & Parker KJ (2011). Psychological stress in childhood and susceptibility to the chronic diseases of aging: Moving toward a model of behavioral and biological mechanisms. Psychological Bulletin, 137(6), 959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris AS, Hays-Grudo J, Kerr K, & Beasley L (In press). The heart of the matter: Developing the whole child through community resources and caregiver relationships. Development and Psychopathology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris AS, Treat A, Hays-Grudo J, Chesher T, Williamson AC, & Mendez J (2018). Integrating research and theory on early relationships to guide intervention and prevention. In Morris AS and Williamson A (Eds.), Building Early Social and Emotional Relationships with Infants and Toddlers (pp. 1–25). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2019). Vibrant and health kids: Aligning science, practice, and policy to advance health equity. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: 10.17226/25466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberlander TF, Weinberg J, Papsdorf M, Grunau R, Misri S, & Devlin AM (2008). Prenatal exposure to maternal depression, neonatal methylation of human glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) and infant cortisol stress responses. Epigenetics, 3(2), 97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz R, & Sibinga EM (2017). The role of mindfulness in reducing the adverse effects of childhood stress and trauma. Children, 4(3), 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pechtel P, & Pizzagalli DA (2011). Effects of early life stress on cognitive and affective function: An integrated review of human literature. Psychopharmacology, 214(1), 55–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecora P, Whittaker J, Barth R, Maluccio AN, DePanfilis D, & Plotnick RD (2017). The child welfare challenge: Policy, practice, and research: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Perry BD (2009). Examining child maltreatment through a neurodevelopmental lens: Clinical applications of the neurosequential model of therapeutics. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 14(4), 240–255. [Google Scholar]

- Perroud N, Paoloni-Giacobino A, Prada P, Olié E, Salzmann A, Nicastro R, … Dieben K (2011). Increased methylation of glucocorticoid receptor gene (nr3c1) in adults with a history of childhood maltreatment: A link with the severity and type of trauma. Translational Psychiatry, 1(12), e59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purewal SK, Bucci M, Wang LG, Koita K, Marques SS, Oh D, & Harris NB (2016). Screening for adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in an integrated pediatric care model. Zero to Three, 36(3), 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Rosanbalm KD, & Murray DW (2017). Promoting self-regulation in early childhood: A practice brief. OPRE Brief #2017–79. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, US. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M (1987). Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 57(3), 316–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M (1979). Fifteen thousand hours: Secondary schools and their effects on children. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff A (1975). Transactional models in early social relations. Human development, 18(1–2), 65–79. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, Seifer R, Baldwin A, & Baldwin C (1993). Stability of intelligence from preschool to adolescence: The influence of social and family risk factors. Child development, 64(1), 80–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, & Gannon-Rowley T (2002). Assessing “neighborhood effects”: Social processes and new directions in research. Annual Review of Sociology, 28(1), 443–478. [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky R, Krey L & McEwen BS (1986). The neurendocrinology of stress and aging: The glucocorticoid cascade hypothesis. Endocrinology, 7, 284–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slopen N, Kubzansky LD, McLaughlin KA, & Koenen KC (2013). Childhood adversity and inflammatory processes in youth: A prospective study. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 38(2), 188–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Lamborn SD, Dornbusch SM, & Darling N (1992). Impact of parenting practices on adolescent achievement: Authoritative parenting, school involvement, and encouragement to succeed. Child development, 63(5), 1266–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathearn L, Mertens CE, Mayes L, Rutherford H, Rajhans P, Xu G, Potenza MN, &. Kim S (2019). Pathways relating the neurobiology of attachment to drug addiction. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teicher MH, & Samson JA (2016). Annual research review: Enduring neurobiological effects of childhood abuse and neglect. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(3), 241–266. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toepfer P, Heim C, Entringer S, Binder E, Wadhwa P, & Buss C (2017). Oxytocin pathways in the intergenerational transmission of maternal early life stress. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 73, 293–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrka AR, Parade SH, Eslinger NM, Marsit CJ, Lesseur C, Armstrong DA, … Seifer R (2015). Methylation of exons 1d, 1f, and 1h of the glucocorticoid receptor gene promoter and exposure to adversity in preschool-aged children. Development and Psychopathology, 27(2), 577–585. doi: 10.1017/S0954579415000176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Kolk B (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind and body in the healing of trauma. NY: Viking. [Google Scholar]

- Wade R Jr., Shea JA, Rubin D, & Wood J (2014). Adverse childhood experiences of low-income urban youth. Pediatrics, 134(1), e13–20. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner E, Cook A, Westcott A, & Koomar J (2011). Sensory motor arousal regulation treatment (SMART), A manual for therapists working with children and adolescents: A “bottom up” approach to treatment of complex trauma. Boston: Trauma Center at JRI. [Google Scholar]

- Warner E, Spinazzola J, Westcott A, Gunn C, & Hodgdon H (2014). The body can change the score: Empirical support for somatic regulation in the treatment of traumatized adolescents. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 7, 237–246. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver IC, Cervoni N, Champagne FA, D’Alessio AC, Sharma S, Seckl JR, … Meaney MJ (2004). Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior. Nature Neuroscience, 7(8), 847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner EE, & Smith RS (1992). Overcoming the odds: High risk children from birth to adulthood: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaoka Y & Bard D (2019). Positive parenting matters in the face of early adversity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 56(4), 530–539, 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JC, & Widom CS (2014). Long-term effects of child abuse and neglect on emotion processing in adulthood. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(8), 1369–1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarobe L, & Bungay H (2017). The role of arts activities in developing resilience and mental wellbeing in children and young people a rapid review of the literature. Perspectives in Public Health, 137(6), 337–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziglar E (1976, April 26). Children – First or Last? New York Times. Retrieved from https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1976/04/25/issue.html [Google Scholar]