Abstract

Despite the success of anti-retroviral therapy (ART) in transforming HIV into manageable disease, it has become evident that long-term ART will not eliminate the HIV reservoir and cure the infection. Alternative strategies to eradicate HIV infection, or at least induce a state of viral control and drug-free remission are therefore needed. Therapeutic vaccination aims to induce or enhance immunity to alter the course of a disease. In this review we provide an overview of the current state of therapeutic HIV vaccine research and summarize the obstacles that the field faces while highlighting potential ways forward for a strategy to cure HIV infection.

Introduction

In 2018, approximately 38 million people were living with HIV globally. Despite the success of anti-retroviral therapy (ART) in limiting HIV replication, decreasing transmission rates, lowering AIDS-related morbidities and improving the quality of life for HIV-infected individuals, it has become evident that long-term ART will not eliminate the HIV reservoir to cure the infection. As a consequence, people living with HIV (PLWH) are forced to stay on life-long therapy with long-term side effects and high cost. Moreover, only an estimated 23.3 million PLWH have access to ART (1), and specifically in resource-constrained settings, access to ART is often limited. Alternative strategies to eradicate HIV infection, or at least induce a state of viral control and drug-free remission are therefore needed.

HIV-1 infection remains incurable as it integrates into the host genome of long-lived memory CD4+ T cell populations where replication-competent virus persists as integrated proviral DNA. From this latent state, viral reemergence and disease progression can rapidly develop if ART is interrupted and virus can disseminate (2–4). These latently infected cells also persist as they are invisible to the immune system due to the lack of active viral replication. The latent viral reservoir therefore presents one of the obstacles for cure approaches. During the natural course of infection, however, a small proportion of HIV-infected individuals are able to spontaneously control HIV replication to undetectable levels in the absence of ART, so called elite controllers (5). Some individuals even demonstrate none or very low-level plasma virus and no clinical disease progression for more than 25 years (6). These elite controllers have therefore been suggested as proof that a functional cure of HIV-1 infection is possible. The underlying mechanisms contributing to this control are likely heterogenous, and a variety of host and viral factors have been associated with the controller phenotype ((5, 7–11). A common feature within elite controllers is the robust T-cell response that can often been found in these individuals. Specifically, enrichment of polyfunctional T-cell populations with the ability to secrete multiple cytokines and/or suppress viral replication in-vitro have been described in the HIV controllers (12–16). It has therefore been suggested that induction of similar immunity in non-controllers, using the elite controllers as ‘blue-print’ for possible immune modulatory approaches, might be a possibility (reviewed in (17)).

One promising strategy for an immunological treatment against HIV infection, either to induce permanent viral control or to even eliminate the viral reservoir, is the development of therapeutic vaccines. Therapeutic vaccines aim to induce or enhance immunity to alter the course of a disease in patients. These vaccines could theoretically provide durable, non-invasive and cost-effective treatment solutions to a vast population of HIV-infected individuals. Indeed in other medical fields, specifically in cancer, therapeutic vaccines have been developed and are being utilized. Currently, there are three therapeutic vaccines approved by the FDA. Bacillus Calmette-Guélin (BCG), initially developed as a vaccine to prevent tuberculosis, proved suprisingly effective in reducing recurrence and progression of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) by increasing the antigen presentation in urothelial tumor cells and boosting local immune responses (18–20). Sipuleucel-T (trade name Provenge), was developed to treat men with prostate cancer by collecting and training their T cells ex-vivo to recognize and eradicate tumor cells after re-infusion (21). It was followed by talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC, trade name Imlygic), a genetically modified oncolytic viral therapy that enhances T-cell function to treat advanced melanoma (22). While the mechanisms of action for these cancer vaccines remain to be completed elucidated, all three vaccines improve specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses that contribute to the control of disease progression (23, 24).

Similar to therapeutic cancer vaccines, therapeutic HIV vaccines aim to boost the magnitude, breadth of antigen-specificities and functionality of anti-HIV T cell responses to eliminate infected cells and facilitate long-term viral control in the absence of ART. In this review we provide an overview of the current state of T-cell-based therapeutic HIV vaccine research and summarize the obstacles that the field faces while highlighting potential ways forward.

Challenges in developing a successful T cell based therapeutic HIV vaccine

One major challenge for the immune response against HIV-1 is the enormous viral sequence diversity, even within each infected individual, and the rapid evolution of the virus during active replication. This allows the virus to permanently escape the immune response (25) and as a consequence viral escape mutations accumulate early on and are achieved in the latent reservoir (26). As HIV primarily infects CD4+ T-cells, progressive CD4+ T cell depletion and subsequent immune dysfunction are a hallmark for this infection. Furthermore, in the presence of uncontrolled antigenemia, and with the increasing lack of T-helper cell help, immune exhaustion becomes a dominating characteristic of the anti-HIV immune response (27, 28). While ART can restore some of the immune dysfunction, it has been shown that the immune system never fully recovers, and that CD8+ T-cells often maintain an epigenetically engraved exhaustion program (29). Before this background, therapeutic HIV vaccine development has been ongoing for several decades. Initial studies used envelope-depleted, inactivated virus to boost immunity in HIV-infected individuals (30) or subunit vaccines with recombinant envelope glycoprotein (rgp160) of HIV-1 IIIB to immunize HIV-infected patients (31). Since then, multiple new vaccine concepts have been developed using DNA; viral vectors such as modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA), adenovirus (Ad), vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) and canary pox virus (ALVAC); RNA; lentiviral vectors and dendritic cells as vaccine vehicles. While all these vaccine candidates have been aimed at improving existing anti-HIV immune responses to improve viral control, the majority of vaccine candidates have specifically focused on the optimization of T cell responses. For example the pTHr.HIVA DNA prime, MVA.HIVA boost vaccine expressing consensus HIV-1 clade A Gag p24/p17 sequences and a string of CD8+ T-cell epitopes (HIVA) to induce and/or boost both HIV specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell response was extensively trialed in in several hundred healthy or HIV-1-infected volunteers in Europe and Africa (reviewed in (32)).

Although many of these therapeutic HIV vaccines resulted in an improvement of autologous HIV-specific T-cell responses, their effects on viral control, as defined by delayed time to viral rebound or reduced viral load set-point after stopping ART, have often been limited. For example, ALVAC-HIV (vCP1452), a modified recombinant canary pox virus vaccine encoding the HIV-1 genes Env, Gag, Pol and Nef, and recombinant gp160, administered to ART suppressed individuals increased HIV-specific CD8+ T cell responses in 11 of 14 study participants but resulted in no significant difference in HIV virus rebound compared to unvaccinated individuals when ART was interrupted suggesting that the vaccine was ineffective in eliciting immune responses sufficient for viral control (33, 34). Similarly, Kinloch-de Loes et al. evaluated in a randomized controlled trial in 78 individuals during acute HIV infection whether the addition of ALVAC-HIV (vCP1452) or ALVAC-HIV and Remune (inactivated envelope-depleted whole virus) to standard ART versus ART alone would result in enhanced viral control. Again, participants in the vaccine arms had significantly increased HIV-1-specific IFN-γ+ CD8+ and CD4+ T cell responses compared to the ART alone treated group however at the study endpoint, 24 weeks after discontinuation of ART, there was no difference in the frequency of study participants that had </=1000 HIV-1 RNA copies/mL between the vaccine or ART alone groups (35).

Additional studies using other vaccine concepts resulted in similar outcomes: Schooley et al. vaccinated 114 ART-treated individuals with a recombinant adenovirus serotype 5 (Ad5)-based vaccine expressing Gag followed by an analytical treatment interruption (ATI) for 16 weeks. The vaccine elicited modest Gag-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses, however, no differences in HIV-1 RNA level setpoint during ATI that met pre-defined levels of significance were observed (36). Moreover, Jacobson et al. used autologous dendritic cells from 54 ART suppressed individuals stimulated with RNA encoding for Gag, Rev, Vpr, and Nef from the study participant’s autologous virus. The vaccine induced multifunctional effector-memory CD8+ T-cell responses, able to express IFN-γ, IL-2, TNF-α, CD107a and granzyme B. Following the ATI, no difference in the end-of-ATI viral load (VL) between the two arms or the VL setpoints post-ATI compared to pre-ART was observed (37). More recently, Sneller et al. reported that a DNA vaccine containing genes encoding the clade B proteins Gag/Pol/Nef/Tat/Vif and Env, followed by a boost with a live attenuated recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus encoding clade B Gag did not prevent viral rebound following ATI in 31 participants in whom ART was initiated during the early stage of HIV infection (38). The vaccine regimen produced a modest increase in HIV specific CD4+ T-cells but did not augment HIV specific CD8+ T-cells.

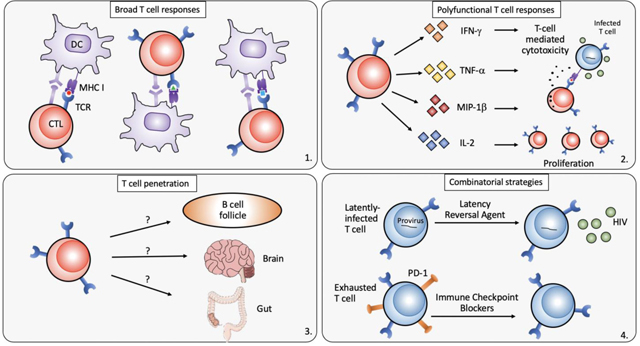

These examples suggest that therapeutic immunization and ART, compared with ART alone, generated HIV-1-specific cellular immunity but did not lead to better virological control of HIV-1 after discontinuation of ART. These data furthermore indicated that in addition to solely expanding the magnitude of HIV specific T-cell responses, other factors, including more defined T-cell characteristics might be critical for post-vaccine viral control. Several potential key requirements for vaccine-induced T-cell immunity have therefore been identified:

Specificity:

The HIV-specific T-cell response is often narrow and directed against HIV epitopes that are already escaped.

Broad T-cell responses targeting both dominant and subdominant epitopes are essential in the context of high viral diversity and fast-emerging viral escape (39, 40), specifically for archived viral resistance in the HIV reservoir (26). Thus, a therapeutic vaccine strategy will need to induce broad and ideally new epitope-specific responses that have not already experienced immune selection pressure.

Quantity:

The HIV specific T-cell compartment contracts in the absence of viral antigen during ART.

Maintaining sufficient frequencies of HIV specific CTLs in peripheral blood but also within tissues is a goal of any therapeutic vaccine concept.

Function:

Immunodominant T-cell responses elicited are often of poor quality.

Studies in HIV controllers suggest effective viral control may be rendered by polyfunctional cytotoxic T cells that have superior cytotoxic activity, are able to release multiple cytokines simultaneously and inhibit viral replication (12, 13, 41).

Location:

The HIV reservoir resides in tissues lacking CTL penetration.

It has been shown that HIV-infected cells are frequently found in B-cell follicles, where follicular CD4+ T-cells are more permissive to HIV infection. Due to the lack of follicular homing receptors, i.e. CXCR5, CTLs fail to accumulate in these “sanctuary” sites (42, 43), and therefore cannot execute their antiviral function. In general, as the HIV reservoir is likely ubiquitous in the host, the vaccine induced immune response needs to likely be present within all tissues and compartments at sufficient numbers to be able to rapidly respond to reactivating reservoir cells.

Durability:

T-cell response longevity is necessary for maintenance of viral control.

Due to HIV’s prolonged period of latency and the difficulty of eliminating all HIV reservoirs in vivo, it is important to maintain long-lived CTL responses that can suppress HIV revitalization over the remaining decades of a PLWH’s life. Otherwise, repeated revaccination will be necessary throughout a PLWH’s lifetime.

A therapeutic vaccine concept that succeeds in achieving a functional, if not sterilizing, cure must likely overcome each of these obstacles, and a number of approaches are being developed to conquer these challenges.

Inducing a broad repertoire of T-cell specificities

During primary infection, HIV-specific CTLs have a significant role in suppressing HIV-1 replication and control viremia (44, 45). Due to this strong selective pressure, HIV often quickly acquire mutations to escape from CTL recognition. These escaped viral strains not only circulate in plasma but also exist in latent reservoirs (16, 46, 47). Unless ART is initiated very early in infection, the latent reservoir becomes almost completely dominated by variants resistant to dominant CTL responses (26). To overcome viral escape to CTL responses, two strategies are generally considered: 1. Target a broad range of HIV epitopes simultaneously so that broad CTL responses can overcome reservoir escape mutations and eliminate virus reservoirs before new mutations arise; 2. Target only the most conserved regions of HIV genome, where CTL escape mutations may significantly lower viral fitness. Both strategies have been extensively explored and important progress has been made so far.

One way to elicit broad CTL response is to improve the presentation of antigens by antigen-presenting cells (APCs), particularly dendritic cells (DC). In HIV-infected individuals, DCs are greatly reduced in both quantity and function due to viral infection (48, 49). DC-based therapeutic vaccines aim to improve presentation of HIV antigens through in vitro DC priming with HIV antigens in order to elicit broad T cells responses, preferentially against previously untargeted epitopes. Indeed, treatment of ART suppressed individuals with ex vivo-generated IFNα dendritic cells loaded with LIPO-5 (HIV-1 Nef, Gag and Pol lipopeptides) induced and/or expanded HIV-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cells directed against dominant and subdominant epitopes across all vaccine regions (50). García et al. reported a clinical trial of a therapeutic DC-based vaccine, in which chronically infected, untreated individuals were given autologous monocyte-derived dendritic cells (MD-DCs) pulsed with heat-inactivated autologous virus. A decrease in plasma viral load setpoint of >/=1 log was observed in conjunction with increased HIV-1-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses against Gag, Nef and Env. The increase in HIV-specific T cell responses observed after vaccination tended to be correlated with the decrease in plasma viral load in vaccinated patients (51). Coelho et al. systematically reviewed twelve DC-based immunotherapies, 38% of which showed some immunogenicity that was associated with transient plasma viral load control (52). However, due to the natural advantage of immunodominant HIV-1 epitopes in endogenous processing and MHC presentation (53), it is difficult to specifically direct CTL responses towards e.g. subdominant epitopes. To this point, an ongoing clinical trial (NCT03758625) aims to test if autologous DCs loaded with a conserved HIV Gag and Pol peptide pool or inactivated autologous HIV will yield broader T-cell responses. Another vaccine aimed at eliciting broad CTL responses was HIVAX, a replication-defective HIV-1 strain pseudotyped with vesicular stomatitis virus G protein (VSV-G). VSV-G pseudotyped HIV have increased infectivity and can infect other immune cells including DC and Langerhans cells (54). Again, the idea was to improve the presentation of HIV epitopes from APC to T cells to elicit a broad range of T cell responses. Tung et al. conducted a clinical trial using HIVAX in HIV-1 infected individuals under active ART and found that HIVAX induced a higher magnitude of CD8+ T cell response than CD4+ T cell response when re-stimulated with Gag peptides and demonstrated that five of the seven participants had a significant reduction of viral load in comparison to their pre-HAART levels after ATI (55).

Along these lines, achieving simultaneous coverage of diverse viral strains and clades by a “global” vaccine has been pursued. Polyvalent ‘mosaic’ antigens have been designed to optimize cellular immunologic coverage of global HIV-1 sequence diversity (56). Compared with consensus or natural sequence HIV-1 antigens, mosaic HIV-1 Gag, Pol and Env antigens expressed by recombinant, replication-incompetent adenovirus serotype 26 (Ad26) vectors markedly improved both the breadth and depth of antigen-specific T cell responses in rhesus monkeys without compromising the response magnitude (57, 58). Phase I/IIa clinical trials of an Ad26-based mosaic vaccine conducted in 393 HIV-uninfected participants demonstrated its ability in eliciting broad T-cell responses. In this study, the mosaic Ad26 plus a high-dose gp140 boost vaccine induced cellular immune breadth covering a median of nine to ten epitopes which was substantially greater than that reported for other Ad5-based and Ad26-based vaccines expressing natural sequence antigens (median of one epitope) (59–61). A phase I/IIa clinical trial completed in 2018 to test the safety and efficacy of Ad26 prime and modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA) boost combination with mosaic inserts in a HIV-infected cohort in Thailand, that initiated ART during the acute infection (NCT02919306). Preliminary data from this trial demonstrated that 100% of the vaccinees responded with significant increase in CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell responses compared to the placebo group. Our group is currently conducting a similar clinical trial of Ad26 prime/MVA boost mosaic vaccine with and without gp140 protein boost (NCT03307915) on individuals who started ART during the chronic phase of the infection but with preserved immunity.

Other groups have focused their immunogen design on more conserved epitopes with the idea that these epitopes are constrained and cannot mutate without affecting viral fitness, thereby increasing antiviral effectiveness of T-cell responses that target such epitopes (62, 63). The first-generation conserved region T-cell immunogen HIVconsv was designed by assembling the 14 most conserved regions of HIV-1 proteome into one chimeric protein (63). In the HIV-CORE002 trial in HIV-negative adults, HIVconsv vaccine vectored in simian adenovirus and MVA induced high levels of effector CD8+ T cells that recognized virus-infected autologous CD4+ T cells and inhibited HIV-1 replication of several HIV-1 isolates by up to 5.79 log10 in vitro. The virus inhibition was mediated by both Gag- and Pol- specific effector CD8+ T cells targeting epitopes that are typically subdominant in natural infection (64). Another clinical trial HIV-CORE004 tested this pan-clade HIVconsv vaccine in HIV-1-negative adults in Nairobi and demonstrated efficacy in inducing high frequencies of broadly HIVconsv-specific plurifunctional T cells, which inhibited viruses from clades A, B, C, D in vitro (65). These results demonstrated the potency of HIVconsv in eliciting broad CTL responses, at least in healthy HIV negative individuals, and thus led to their clinical exploration in HIV-1-infected individuals for evaluation of therapeutic efficacy. The BCN01 trial was a phase I, non-randomized study in individuals of early HIV-1 infection to evaluate the safety and efficacy of HIVconsv vectored on ChAdV63 (chimpanzee adenovirus serotype 63) prime and MVA boost. In the vaccinated group, there was a marked shift in immunodominance profiles of HIV-1-specific CD8+ T cell responses towards conserved T-cell epitopes, along with high in vitro viral inhibition capacity without signs of immune exhaustion (66). However, the efficacy of HIVconsv vaccine in reduction of virus reservoirs or control of viral load after ATI remains to be evaluated in further studies.

Based on this first-generation conserved-region vaccine, Ondondo et al. developed a second-generation conserved vaccine expressing novel immunogens tHIVconsvX which combines regions of HIV-1 proteins functionally conserved across all M group viruses, bivalent complementary mosaic immunogens and epitopes associated with low viral load in HIV controllers. When vectored by a combination of DNA, simian adenovirus and MVA, tHIVconsvX elicited broad CTL responses, whose magnitude and breadth correlate with low viral load and high CD4+ T cell count in HIV-infected treatment-naïve individuals (67). As a result, an MVA-vectored vaccine expressing tHIVconsv3 and tHIVconsv4 immunogens (derived from tHIVconsvX) was initiated last year to evaluate its safety and efficacy in HIV-infected adults (NCT03844386). Other approaches that target HIV conserved regions are showing promises as well. For example, the PENNVAX-B vaccine, synthetic plasmids expressing multiclade HIV Gag and Pol as well as a consensus Clade B Env, elicited expanded CTL responses towards the multiclade Gag/Pol/Env antigens and improved CTL lytic granule loading activity in a small cohort of HIV-infected individuals (68). A larger-scale phase II trial is currently enrolling to further assess if PENNVAX could lead to a significant reduction of HIV reservoir size (NCT03606213). Another DNA vaccine that carried HIV-derived conserved element (CE) p24 Gag DNA was shown to redirect the cellular responses to subdominant Gag epitopes in rhesus macaques (69). A clinical trial to test its potency in eliciting novel CTL responses in PLWH is fully enrolled and results are pending (NCT03560258).

Overall, all strategies are still under active development and novel concepts are being proposed. As an example, Gaiha et al. suggested recently an alternative structure-based network analysis that combined protein structure data and network theory to quantify the topological importance of each amino acid residue and evaluate and rank HIV CTL epitopes. CTL epitope targets of high topological importance successfully distinguished HIV controllers from progressors irrespective of HLA alleles (70) suggesting that these key conserved epitopes could be targeted by a vaccine. The future will show if one or another or potentially even a combination of consensus, conserved, mosaic or networked epitope approaches will be most successful.

In addition, no vaccine strategy even if it elicited broad CTL responses, has proven efficacious in substantially reducing the HIV reservoirs or inducing sustained virus control in human clinical trials. It therefore seems that broad CTL responses are necessary but that vaccine regimens have to also focus on additional T-cell characteristic, e.g. functionality.

Quality of CTL responses including polyfunctionality, proliferation and cytotoxicity is crucial

As the size of the CTL response is important in cellular immunity, the quality of CTL responses has been shown to be crucial in controlling viral load. Studies in HIV controllers demonstrated that although the overall breadth and magnitude of CD8+ T-cell responses induced in elite controllers is comparable to HIV progressors (HIV-infected individuals with high-level viremia and progressive immune destruction), several qualitative differences in T-cell characteristics have been described (11): CD8+ T cells from elite controllers can effectively inhibit HIV-1 replication in ex vivo-infected autologous CD4+ T cells (12, 71), mediated by increased expression of cytotoxic granule components (13, 72); controller CD8+ T cells are more likely to be polyfunctional, that is, to simultaneously execute multiple effector functions (degranulation, secretion of IFN-γ, MIP-1β, TNF-α and IL-2, cytotoxicity etc.) (41); in some cases, within an HLA restricted epitope response, differences in T-cell receptor clonotypes between controllers and progressors lead to differences in effectiveness in inhibiting virus infection (73). These cumulative data suggest that high-quality cytotoxic T cells might be a correlate of protective immunity; however, inducing these responses, particularly in an immune environment that has often been damaged by persistent HIV infection, is challenging.

Several studies have shown that the quality of HIV-specific CTL responses can be enhanced by DC-based vaccines. Lu et al. conducted a clinical trial utilizing a vaccine consistent of autologous monocyte-derived DCs pulsed with autologous inactivated HIV-1 in patients with chronic HIV-1 infection. This vaccine induced HIV-1 Gag-specific CD8+ T cells by more than threefold at day 112, whereas the percentage of HIV-1 Gag-specific CD8+ T cells expressing perforin increased around twofold. While after 1 year the percentages of total Gag-specific CD8+ T cells did not correlate with plasma viral load decrease, HIV-1 Gag-specific CD8+ T cells expressing perforin were correlated with lower plasma viral loads (74). This study was consistent with previous reports about the importance of perforin expression in effector CD8+ T cells, and their enrichment in HIV non-progressors compared to individuals with progressive disease (72, 75). Another study using a DC-based vaccine also led to increased functionality in HIV-specific T-cell immunity: Lévy et al. administered autologous DC pulsed with HIV lipopeptides from Gag, Pol and Nef to patients on ART, and the vaccine regimen increased both the breadth of epitope specific immune responses and the frequency of functional CD8+ T cells producing at least two cytokines across IFN 2. In this study a correlation was found specifically between lower viral loads following ATI and the frequency of polyfunctional CD4+ T cells (76).

A number of other therapeutic vaccine candidates also demonstrated improved T cell qualities. Casazza et al. evaluated a vaccine regimen that combined an ad5 vector encoding clade B Gag and Pol, and clade A, B, and C Env with a DNA vaccine encoding the same antigens plus clade B Nef in 17 ART suppressed individuals. The vaccine improved the polyfunctionality of HIV-specific CD8+ T cells, the proportion of CTLs able to co-produce IFN-γ, Mip1b and TNF α increased, but these responses did not impact viral loads, at least at the single copy level (77). Harari et al. showed that a poxvirus-based vector, NYVAC, expressing Gag, Pol, Nef and Env, administered to 10 ART suppressed individuals, enhanced both polyfunctionality, as determined by co-production of IL-2, IFN-γ, or TNF-α and proliferative capacity of HIV-specific CD8+ T cells, but its efficacy in viral control was not measured in this study (78). Lind et al. demonstrated that Vacc-4x, a peptide vaccine derived from conserved domains of HIV-1 p24 Gag, given the 25 ART suppressed individuals, increased Vacc-4x-specific CD8+ T cell degranulation and IFN-γ production and proliferative capacity was even increased in 80% of vaccinated study participants (79).

Although these results suggest, that CTL qualities can be optimized by vaccines, it remains unclear how durable these CTL qualities are. Moreover, the underlying mechanism of CTL polyfunctionality, proliferation capacity and cytotoxicity remain to be fully understood and further research on CTL function may provide new directions for future HIV therapeutic vaccine design. For example, a mechanistic study led by Chiu et al. showed that HIV-specific T-cell polyfunctionality can be enhanced by inhibition of sprout-2, a negative regulator of the MAPK/ERK pathway, offering a new potential target for boosting polyfunctionality (80). Another study pointed out that therapeutic vaccination of HIV can increase the frequency of regulatory T cells that suppress the polyfunctionality of CD8+ T cells, suggesting that the role of Tregs should also be considered in HIV therapeutic vaccine trials (81).

In addition, functional avidity is also an important CTL quality proven to be associated with superior control of HIV-1 replication (82, 83). Functional avidity measures the sensitivity of T cells in recognizing cognate antigens and is determined by the ratio of recruited clones with high versus low avidity among a heterogenous oligoclonal T-cell population. It has been suggested that the lack of an immunodominant response to a specific epitope could be caused by competition between multiple CD8+ T cell clonotypes (84). How to selectively stimulate high-avidity HIV-specific T cells by vaccination remains unclear. Recently, Billeskov et al. showed that vaccination with low-dose antigen combined with a cationic liposomal adjuvant selectively primed CD4+ T cells of higher functional avidity, consequently improving CD8+ T-cell antiviral effects (85). Hu et al. reported that vaccination with vaccinia virus in mice significantly enhanced the functional avidity of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells through the intrinsic MyD88 pathway independent of TCR selection (86). Alternatively, gene therapy approaches that manually select and engineer TCR for high functional avidity are also being explored (87, 88).

Effective CTL penetration to HIV reservoirs in all locations

One of the most challenging barriers for HIV eradication is the prevalence of HIV reservoir cells in a wide variety of tissues and with distinct viral and cellular signatures (89). Even when effective CTL responses are stimulated and maintained, HIV can still evade being cleared given the poor accessibility of some tissue reservoirs and reduced CTL penetration into these compartments.

Because of the high susceptibility of follicular CD4+ T cells to HIV infection, poor follicular CTL penetration, and significant extracellular HIV virion accumulation on the surface of follicular dendritic cells (FDCs), B cell follicles are considered a critical sanctuary for HIV replication and persistence (90). HIV-specific CTL are abundant within lymphoid tissues, but fail to accumulate within lymphoid follicles where HIV-1 replication is concentrated (43). Recent work by Louis Picker validated that productive SIV infection in rhesus monkey elite controller is restricted to follicular CD4+ T helper cells (TFH)) (42) due to the physical exclusion of CD8+ T cells from B cell follicles (91). A study of peripheral blood from chronically HIV-infected individuals on ART also showed that within central memory CD4+ T cells, peripheral T follicular helper cells are the most significant HIV reservoirs (92). Follicular cytotoxic T cells, a group of cytotoxic T cells expressing CXCR5, were found to localize to B cell follicles and control viral infection of TFH cells (93). Thus, boosting cytotoxic CTLs with specific homing signatures like CXCR5 could be valuable in eliminating the viral reservoir in B cell follicles. An alternative strategy could be to chemically induce or genetically engineer CTL to express CXCR5 (94). Indeed, transduction with CXCR5 effectively localized CTL to B cell follicles in rhesus macaques, but if these cells were enough to clear the B-follicular HIV reservoir remains unknown (95, 96). Other strategies include treatment with IL-15, use of bispecific antibodies and disruption of the follicle by medication such as rituximab (97–100).

The central nervous system (CNS) is another compartment that might not be easily targetable for vaccine mediated HIV reservoir elimination approaches. While it is populated with macrophages and astrocytes that might be susceptible to HIV infection these cell types are potentially less responsive to CTL elimination (reviewed in (101)). Furthermore, the blood-brain barrier (BBB) by regulating the trafficking of cells might prevent the free influx of vaccine induced T-cell responses and If prior therapeutic vaccines have induced relevant HIV specific CD8+ T cell response in the CNS has not be examined. Finally it remains questionable if highly cytolytic CD8+ T cell response should be induced in the CNS via therapeutic vaccination, as massive infiltration by polyfunctional CD8+ T-cell could result in uncontrolled astrocytic and microglial activation with detrimental consequences for the vaccinees (102).

Other cell types than CD4+ T-cells, in particular macrophages, serve as harbor for latent HIV. Traditionally, macrophages are believed to have a moderate life span and lack self-renewing potential, but recent data suggested the role of these cells as long-lived HIV reservoirs even during active ART (103, 104). Moreover, Clayton et al. showed that macrophages were intrinsically more resistant to CTL mediated killing relative to CD4+ T cells (105). New strategies to enhance CTL activities towards HIV-infected macrophages remain to be investigated.

Combinatorial strategies to enhance the efficacy of CTL-based therapeutic vaccines

In light of HIV latency, durable viral remission will likely require the combined reactivation of the latent virus coupled with potent HIV reservoir elimination strategies. Latency reversal agents (LRA) can activate latently infected T cells and improve recognition by both CTLs and antibodies. The key to successful implementation of this so-called “shock and kill” method is to find an effective yet safe LRA. Many LRA candidates have been proposed and some have been tested in clinical trials (106, 107). Among them, histone deacetylase inhibitors have initially demonstrated some of the most promise. For example, Elliott et al. revealed that short-course vorinostat use in HIV-infected ART-suppressed patients could activate HIV transcription, demonstrated by increased level of HIV RNA in total CD4+ T-cells from blood (108). A combinatorial study called the RIVER (Research in Viral Eradication of HIV Reservoirs) was conducted with newly HIV-infected adults to assess the combinatorial effect of a therapeutic vaccine ChAdV63.HIVconsv prime with MVA.HIVconsv boost followed by vorinostat administration. As the first randomized human trial using the “shock and kill” cure strategy, the RIVER study regimen induced significantly higher HIV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses in the intervention group, but there was no difference between intervention group and control group for the primary endpoint, that of change in the viral reservoir as measured by total HIV DNA/million CD4+ T cells. Another histone deacetylase inhibitor romidepsin was also under clinical investigation together with HIV therapeutic vaccine candidates. BCN02-Romi enrolled 15 individuals from the aforementioned BCN01 trial to assess the clinical effects of MVA.HIVconsv vaccine combined with romidepsin. Preliminary results revealed that 4 out of 13 subjects (31%) controlled viral rebound beyond four weeks, the first report of viremic control in a large proportion of participants (109, 110).

Toll-like receptor agonists were also discovered to be effective latency reversing agents in vitro (111–113), and a number of them are in clinical trials to evaluate their safety and efficacy. The TLR7 agonist vesatolimod (GS-9620) was shown to reverse latency state and reduce viral reservoir size in simian-immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected rhesus macaques on ART (114), and has undergone multiple clinical trials to evaluate its therapeutic effects in HIV-infected individuals on ART and were overall well tolerated, with the expected immune activation, however, no direct effect on virological markers were observed (115). When combined with the Ad26/MVA mosaic vaccine (as described before), the TLR7 agonist GS-9620 improved virologic control and delayed viral rebound following ART discontinuation in SIV-infected rhesus monkey (116). Human clinical trials to test T-cell based therapeutic vaccines combined with TLR7 agonists have started. For example, the ongoing human clinical trial AELIX-003 (EudraCT 2018–002125-30) is aimed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of vesatolimod with AELIX therapeutic’ HTI vaccine that contains conserved HIV antigenic regions against which T-cell responses are enriched in HIV controllers (117, 118). Overall, the combinatorial strategy of a potent CTL-based vaccine with an effective LRA is currently under extensive exploration.

Cytokines can support the expansion of stimulated virus-specific T-cells, when administered as a vaccine adjuvant. A number of cytokines have been combined with T-cell vaccines in clinical trials to boost T-cell expansion and function, including IL-2, IL-7, IL-12, IL-15 and IL-21. IL-2 has been considered as T-cell survival signal, but it also promotes Treg expansion. The ANRS 093 study combined the ALVAC-HIV and Lipo-6T vaccine with IL-2 administration to induce sustained and broad HIV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses in chronically HIV infected individuals on ART (119) and the T-cell responses correlated with the reduction of the time off antiviral therapy. Direct administration of IL-7 to ART-treated HIV-infected individuals induced a sustained expansion of naïve and central memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (120). This effect could be advantageous in the context of therapeutic immunization by potentially increasing the number of vaccine-elicited HIV-specific T cells, but it could also pose a risk due to an expansion in the absolute number of circulating CD4+ T cells harboring integrated HIV DNA (121). IL-15 might also be a promising tool for HIV immunotherapy given its role in enhancing the survival of HIV specific CD8+ T cells (122): co-immunization with a chimeric Simian-Human Immunodeficiency Virus (SHIV) antigen and IL-15 plasmid elicited protection against SHIV in macaques (123); however, in a different study, IL-15 abrogated a vaccine-induced decrease in virus level in SIV-infected macaques (124), again indicating both pathogenic and therapeutic potentials of immune cytokines (reviewed in (125)). More interestingly, heterodimeric interleukin-15 (hetIL-15) or an IL-15 superagonist were shown to activate and redirect SIV-specific CD8+ T cells from peripheral blood to B-cell follicles by upregulating their CXCR5 level (126, 127). IL-21 produced by CD4+ T cells is considered necessary for the maintenance of CD8+ T cell function, especially in HIV controllers (128); a clinical trial combining IL-21 with ART helped to restore intestinal immune cells and reduced viral reservoirs in SIV-infected macaques (129).

It has been demonstrated that immune exhaustion is under the active control of inhibitory immune checkpoints such as programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein (CTLA-4), whose selective blockade can reinvigorate antigen-specific CD8+ T cell function (130–132). Therefore, when combined with HIV-specific T-cell vaccines, immune checkpoint blockers (ICB) could help reverse exhaustion and unchain cytotoxic T cells to target and kill infected cells to decrease the virus reservoir. To test this strategy, studies with SIV-infected rhesus macaques have revealed that anti-PD-1 antibody can expand functional virus-specific CD8+ T cells and lower SIV RNA levels in plasma (133). The first clinical trial of an anti-PD-L1 antibody in HIV-infected individuals was conducted in 2017 by Bristol-Myers Squibb, but resulted only in a modest increase in Gag-specific CD8+ T cells expressing interferon-γ in a subset of study participants (134). More studies are needed to validate this strategy.

Conclusion

The past 30 years of HIV research have witnessed huge progress in our understanding of HIV immunology. As the field continues to explore a wide range of approaches for curing HIV/AIDS, therapeutic vaccination remains one of the most cost-effective, non-invasive and promising cure strategies. From studies in HIV controllers, we have observed that potent, polyfunctional T-cell responses can effectively suppress viral load in the absence of ART. However, eliciting polyfunctional T-cell responses in all HIV-infected individuals independent of HLA background, disease state etc. remains a challenge.

Here we have laid out the potential cornerstones for a successful therapeutic vaccine: a vaccine that induces broad, high-quality, follicle-penetrating HIV-specific T-cell responses, that are durable and rapidly responsive to clear reactivating reservoir cells. Together with the help of ICB, LRA and/or other immunomodulatory support, to recover immune exhaustion and reverse viral latency, future studies will show if the concept of therapeutic vaccination will ultimately be successful.

Acknowledgment:

All authors have read the journal’s policy on disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. Z.C. has no conflict of interest to declare. B.J. is co-investigator on a research grant from Gilead Sciences.

All authors have read the journal’s authorship agreement. Z.C. and B.J. have prepared, reviewed and approved the manuscript. We thank Emily Sundquist for proofreading the manuscript. No other editorial support has been used for the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference:

- 1.UNAIDS. 2019. Global HIV & AIDS statistics - 2019 fact sheet. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finzi D, Blankson J, Siliciano JD, Margolick JB, Chadwick K, Pierson T, Smith K, Lisziewicz J, Lori F, Flexner C, Quinn TC, Chaisson RE, Rosenberg E, Walker B, Gange S, Gallant J, Siliciano RF. 1999. Latent infection of CD4+ T cells provides a mechanism for lifelong persistence of HIV-1, even in patients on effective combination therapy. Nat Med 5:512–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finzi D, Hermankova M, Pierson T, Carruth LM, Buck C, Chaisson RE, Quinn TC, Chadwick K, Margolick J, Brookmeyer R, Gallant J, Markowitz M, Ho DD, Richman DD, Siliciano RF. 1997. Identification of a reservoir for HIV-1 in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Science 278:1295–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chun TW, Davey RT Jr., Engel D, Lane HC, Fauci AS. 1999. Re-emergence of HIV after stopping therapy. Nature 401:874–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deeks SG, Walker BD. 2007. Human immunodeficiency virus controllers: mechanisms of durable virus control in the absence of antiretroviral therapy. Immunity 27:406–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casado C, Galvez C, Pernas M, Tarancon-Diez L, Rodriguez C, Sanchez-Merino V, Vera M, Olivares I, De Pablo-Bernal R, Merino-Mansilla A, Del Romero J, Lorenzo-Redondo R, Ruiz-Mateos E, Salgado M, Martinez-Picado J, Lopez-Galindez C. 2020. Permanent control of HIV-1 pathogenesis in exceptional elite controllers: a model of spontaneous cure. Sci Rep 10:1902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pereyra F, Addo MM, Kaufmann DE, Liu Y, Miura T, Rathod A, Baker B, Trocha A, Rosenberg R, Mackey E, Ueda P, Lu Z, Cohen D, Wrin T, Petropoulos CJ, Rosenberg ES, Walker BD. 2008. Genetic and immunologic heterogeneity among persons who control HIV infection in the absence of therapy. J Infect Dis 197:563–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lambotte O, Ferrari G, Moog C, Yates NL, Liao HX, Parks RJ, Hicks CB, Owzar K, Tomaras GD, Montefiori DC, Haynes BF, Delfraissy JF. 2009. Heterogeneous neutralizing antibody and antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity responses in HIV-1 elite controllers. AIDS 23:897–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.International HIVCS, Pereyra F, Jia X, McLaren PJ, Telenti A, de Bakker PI, Walker BD, Ripke S, Brumme CJ, Pulit SL, Carrington M, Kadie CM, Carlson JM, Heckerman D, Graham RR, Plenge RM, Deeks SG, Gianniny L, Crawford G, Sullivan J, Gonzalez E, Davies L, Camargo A, Moore JM, Beattie N, Gupta S, Crenshaw A, Burtt NP, Guiducci C, Gupta N, Gao X, Qi Y, Yuki Y, Piechocka-Trocha A, Cutrell E, Rosenberg R, Moss KL, Lemay P, O’Leary J, Schaefer T, Verma P, Toth I, Block B, Baker B, Rothchild A, Lian J, Proudfoot J, Alvino DM, Vine S, Addo MM, et al. 2010. The major genetic determinants of HIV-1 control affect HLA class I peptide presentation. Science 330:1551–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ackerman ME, Mikhailova A, Brown EP, Dowell KG, Walker BD, Bailey-Kellogg C, Suscovich TJ, Alter G. 2016. Polyfunctional HIV-Specific Antibody Responses Are Associated with Spontaneous HIV Control. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walker BD, Yu XG. 2013. Unravelling the mechanisms of durable control of HIV-1. Nat Rev Immunol 13:487–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saez-Cirion A, Lacabaratz C, Lambotte O, Versmisse P, Urrutia A, Boufassa F, Barre-Sinoussi F, Delfraissy JF, Sinet M, Pancino G, Venet A, Agence Nationale de Recherches sur le Sida EPHIVCSG. 2007. HIV controllers exhibit potent CD8 T cell capacity to suppress HIV infection ex vivo and peculiar cytotoxic T lymphocyte activation phenotype. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:6776–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Migueles SA, Osborne CM, Royce C, Compton AA, Joshi RP, Weeks KA, Rood JE, Berkley AM, Sacha JB, Cogliano-Shutta NA, Lloyd M, Roby G, Kwan R, McLaughlin M, Stallings S, Rehm C, O’Shea MA, Mican J, Packard BZ, Komoriya A, Palmer S, Wiegand AP, Maldarelli F, Coffin JM, Mellors JW, Hallahan CW, Follman DA, Connors M. 2008. Lytic granule loading of CD8+ T cells is required for HIV-infected cell elimination associated with immune control. Immunity 29:1009–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hersperger AR, Pereyra F, Nason M, Demers K, Sheth P, Shin LY, Kovacs CM, Rodriguez B, Sieg SF, Teixeira-Johnson L, Gudonis D, Goepfert PA, Lederman MM, Frank I, Makedonas G, Kaul R, Walker BD, Betts MR. 2010. Perforin expression directly ex vivo by HIV-specific CD8 T-cells is a correlate of HIV elite control. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pereyra F, Palmer S, Miura T, Block BL, Wiegand A, Rothchild AC, Baker B, Rosenberg R, Cutrell E, Seaman MS, Coffin JM, Walker BD. 2009. Persistent low-level viremia in HIV-1 elite controllers and relationship to immunologic parameters. J Infect Dis 200:984–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shan L, Deng K, Shroff NS, Durand CM, Rabi SA, Yang HC, Zhang H, Margolick JB, Blankson JN, Siliciano RF. 2012. Stimulation of HIV-1-specific cytolytic T lymphocytes facilitates elimination of latent viral reservoir after virus reactivation. Immunity 36:491–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collins DR, Gaiha GD, Walker BD. 2020. CD8(+) T cells in HIV control, cure and prevention. Nat Rev Immunol doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0274-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morales A, Eidinger D, Bruce AW. 1976. Intracavitary Bacillus Calmette-Guerin in the treatment of superficial bladder tumors. J Urol 116:180–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green J, Fuge O, Allchorne P, Vasdev N. 2015. Immunotherapy for bladder cancer. Research and Reports in Urology doi: 10.2147/rru.s63447:65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeMaria PJ, Bilusic M. 2019. Cancer Vaccines. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 33:199–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheever MA, Higano CS. 2011. PROVENGE (Sipuleucel-T) in Prostate Cancer: The First FDA-Approved Therapeutic Cancer Vaccine. Clinical Cancer Research 17:3520–3526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conry RM, Westbrook B, McKee S, Norwood TG. 2018. Talimogene laherparepvec: First in class oncolytic virotherapy. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 14:839–846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Antonarakis ES, Small EJ, Petrylak DP, Quinn DI, Kibel AS, Chang NN, Dearstyne E, Harmon M, Campogan D, Haynes H, Vu T, Sheikh NA, Drake CG. 2018. Antigen-Specific CD8 Lytic Phenotype Induced by Sipuleucel-T in Hormone-Sensitive or Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer and Association with Overall Survival. Clin Cancer Res 24:4662–4671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaufman HL, Kim DW, DeRaffele G, Mitcham J, Coffin RS, Kim-Schulze S. 2010. Local and distant immunity induced by intralesional vaccination with an oncolytic herpes virus encoding GM-CSF in patients with stage IIIc and IV melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol 17:718–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Salazar MG, Keele BF, Learn GH, Giorgi EE, Li H, Decker JM, Wang S, Baalwa J, Kraus MH, Parrish NF, Shaw KS, Guffey MB, Bar KJ, Davis KL, Ochsenbauer-Jambor C, Kappes JC, Saag MS, Cohen MS, Mulenga J, Derdeyn CA, Allen S, Hunter E, Markowitz M, Hraber P, Perelson AS, Bhattacharya T, Haynes BF, Korber BT, Hahn BH, Shaw GM. 2009. Genetic identity, biological phenotype, and evolutionary pathways of transmitted/founder viruses in acute and early HIV-1 infection. J Exp Med 206:1273–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deng K, Pertea M, Rongvaux A, Wang L, Durand CM, Ghiaur G, Lai J, McHugh HL, Hao H, Zhang H, Margolick JB, Gurer C, Murphy AJ, Valenzuela DM, Yancopoulos GD, Deeks SG, Strowig T, Kumar P, Siliciano JD, Salzberg SL, Flavell RA, Shan L, Siliciano RF. 2015. Broad CTL response is required to clear latent HIV-1 due to dominance of escape mutations. Nature 517:381–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Day CL, Kaufmann DE, Kiepiela P, Brown JA, Moodley ES, Reddy S, Mackey EW, Miller JD, Leslie AJ, DePierres C, Mncube Z, Duraiswamy J, Zhu B, Eichbaum Q, Altfeld M, Wherry EJ, Coovadia HM, Goulder PJ, Klenerman P, Ahmed R, Freeman GJ, Walker BD. 2006. PD-1 expression on HIV-specific T cells is associated with T-cell exhaustion and disease progression. Nature 443:350–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trautmann L, Janbazian L, Chomont N, Said EA, Gimmig S, Bessette B, Boulassel MR, Delwart E, Sepulveda H, Balderas RS, Routy JP, Haddad EK, Sekaly RP. 2006. Upregulation of PD-1 expression on HIV-specific CD8+ T cells leads to reversible immune dysfunction. Nat Med 12:1198–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Youngblood B, Noto A, Porichis F, Akondy RS, Ndhlovu ZM, Austin JW, Bordi R, Procopio FA, Miura T, Allen TM, Sidney J, Sette A, Walker BD, Ahmed R, Boss JM, Sekaly RP, Kaufmann DE. 2013. Cutting edge: Prolonged exposure to HIV reinforces a poised epigenetic program for PD-1 expression in virus-specific CD8 T cells. J Immunol 191:540–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Churdboonchart V, Moss RB, Sirawaraporn W, Smutharaks B, Sutthent R, Jensen FC, Vacharak P, Grimes J, Theofan G, Carlo DJ. 1998. Effect of HIV-specific immune-based therapy in subjects infected with HIV-1 subtype E in Thailand. AIDS 12:1521–1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsoukas CM, Raboud J, Bernard NF, Montaner JSG, Gill MJ, Rachlis A, Fong IW, Schlech W, Djurdjev O, Freedman J, Thomas R, LafreniÈRe R, Wainberg MA, Cassol S, O’Shaughnessy M, Todd J, Volvovitz F, Smith GE. 1998. Active Immunization of Patients with HIV Infection: A Study of the Effect of VaxSyn, a Recombinant HIV Envelope Subunit Vaccine, on Progression of Immunodeficiency. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses 14:483–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanke T, Goonetilleke N, McMichael AJ, Dorrell L. 2007. Clinical experience with plasmid DNA- and modified vaccinia virus Ankara-vectored human immunodeficiency virus type 1 clade A vaccine focusing on T-cell induction. J Gen Virol 88:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jin X, Ramanathan J, Murugappan, Barsoum S, Deschenes GR, Ba L, Binley J, Schiller D, Bauer DE, Chen DC, Hurley A, Gebuhrer L, El Habib R, Caudrelier P, Klein M, Zhang L, Ho DD, Markowitz M. 2002. Safety and Immunogenicity of ALVAC vCP1452 and Recombinant gp160 in Newly Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1-Infected Patients Treated with Prolonged Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy. Journal of Virology 76:2206–2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Markowitz M, Jin X, Hurley A, Simon V, Ramratnam B, Louie M, Deschenes GR, Ramanathan M Jr., Barsoum S, Vanderhoeven J, He T, Chung C, Murray J, Perelson AS, Zhang L, Ho DD. 2002. Discontinuation of antiretroviral therapy commenced early during the course of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection, with or without adjunctive vaccination. J Infect Dis 186:634–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kinloch-de Loes S, Hoen B, Smith DE, Autran B, Lampe FC, Phillips AN, Goh LE, Andersson J, Tsoukas C, Sonnerborg A, Tambussi G, Girard PM, Bloch M, Battegay M, Carter N, El Habib R, Theofan G, Cooper DA, Perrin L, Group QS. 2005. Impact of therapeutic immunization on HIV-1 viremia after discontinuation of antiretroviral therapy initiated during acute infection. J Infect Dis 192:607–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schooley RT, Spritzler J, Wang H, Lederman MM, Havlir D, Kuritzkes DR, Pollard R, Battaglia C, Robertson M, Mehrotra D, Casimiro D, Cox K, Schock B, Team ACTGS. 2010. AIDS clinical trials group 5197: a placebo-controlled trial of immunization of HIV-1-infected persons with a replication-deficient adenovirus type 5 vaccine expressing the HIV-1 core protein. J Infect Dis 202:705–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jacobson JM, Routy JP, Welles S, DeBenedette M, Tcherepanova I, Angel JB, Asmuth DM, Stein DK, Baril JG, McKellar M, Margolis DM, Trottier B, Wood K, Nicolette C. 2016. Dendritic Cell Immunotherapy for HIV-1 Infection Using Autologous HIV-1 RNA: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 72:31–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sneller MC, Justement JS, Gittens KR, Petrone ME, Clarridge KE, Proschan MA, Kwan R, Shi V, Blazkova J, Refsland EW, Morris DE, Cohen KW, McElrath MJ, Xu R, Egan MA, Eldridge JH, Benko E, Kovacs C, Moir S, Chun TW, Fauci AS. 2017. A randomized controlled safety/efficacy trial of therapeutic vaccination in HIV-infected individuals who initiated antiretroviral therapy early in infection. Sci Transl Med 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Borrow P, Lewicki H, Wei X, Horwitz MS, Peffer N, Meyers H, Nelson JA, Gairin JE, Hahn BH, Oldstone MB, Shaw GM. 1997. Antiviral pressure exerted by HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) during primary infection demonstrated by rapid selection of CTL escape virus. Nat Med 3:205–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Price DA, Goulder PJ, Klenerman P, Sewell AK, Easterbrook PJ, Troop M, Bangham CR, Phillips RE. 1997. Positive selection of HIV-1 cytotoxic T lymphocyte escape variants during primary infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94:1890–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Betts MR, Nason MC, West SM, De Rosa SC, Migueles SA, Abraham J, Lederman MM, Benito JM, Goepfert PA, Connors M, Roederer M, Koup RA. 2006. HIV nonprogressors preferentially maintain highly functional HIV-specific CD8+ T cells. Blood 107:4781–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fukazawa Y, Lum R, Okoye AA, Park H, Matsuda K, Bae JY, Hagen SI, Shoemaker R, Deleage C, Lucero C, Morcock D, Swanson T, Legasse AW, Axthelm MK, Hesselgesser J, Geleziunas R, Hirsch VM, Edlefsen PT, Piatak M, Estes JD, Lifson JD, Picker LJ. 2015. B cell follicle sanctuary permits persistent productive simian immunodeficiency virus infection in elite controllers. Nature Medicine 21:132–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Connick E, Mattila T, Folkvord JM, Schlichtemeier R, Meditz AL, Ray MG, McCarter MD, MaWhinney S, Hage A, White C, Skinner PJ. 2007. CTL Fail to Accumulate at Sites of HIV-1 Replication in Lymphoid Tissue. The Journal of Immunology 178:6975–6983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walker BD, Chakrabarti S, Moss B, Paradis TJ, Flynn T, Durno AG, Blumberg RS, Kaplan JC, Hirsch MS, Schooley RT. 1987. HIV-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in seropositive individuals. Nature 328:345–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koup RA, Safrit JT, Cao Y, Andrews CA, McLeod G, Borkowsky W, Farthing C, Ho DD. 1994. Temporal association of cellular immune responses with the initial control of viremia in primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 syndrome. J Virol 68:4650–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goulder PJ, Phillips RE, Colbert RA, McAdam S, Ogg G, Nowak MA, Giangrande P, Luzzi G, Morgan B, Edwards A, McMichael AJ, Rowland-Jones S. 1997. Late escape from an immunodominant cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response associated with progression to AIDS. Nat Med 3:212–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Phillips RE, Rowland-Jones S, Nixon DF, Gotch FM, Edwards JP, Ogunlesi AO, Elvin JG, Rothbard JA, Bangham CR, Rizza CR, et al. 1991. Human immunodeficiency virus genetic variation that can escape cytotoxic T cell recognition. Nature 354:453–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Donaghy H, Gazzard B, Gotch F, Patterson S. 2003. Dysfunction and infection of freshly isolated blood myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells in patients infected with HIV-1. Blood 101:4505–4511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chehimi J, Campbell DE, Azzoni L, Bacheller D, Papasavvas E, Jerandi G, Mounzer K, Kostman J, Trinchieri G, Montaner LJ. 2002. Persistent Decreases in Blood Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Number and Function Despite Effective Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy and Increased Blood Myeloid Dendritic Cells in HIV-Infected Individuals. 168:4796–4801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Surenaud M, Montes M, Lindestam Arlehamn CS, Sette A, Banchereau J, Palucka K, Lelievre JD, Lacabaratz C, Levy Y. 2019. Anti-HIV potency of T-cell responses elicited by dendritic cell therapeutic vaccination. PLoS Pathog 15:e1008011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Garcia F, Climent N, Guardo AC, Gil C, Leon A, Autran B, Lifson JD, Martinez-Picado J, Dalmau J, Clotet B, Gatell JM, Plana M, Gallart T, Group DMOS. 2013. A dendritic cell-based vaccine elicits T cell responses associated with control of HIV-1 replication. Sci Transl Med 5:166ra2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coelho A, De Moura R, Kamada A, Da Silva R, Guimarães R, Brandão L, De Alencar L, Crovella S. 2016. Dendritic Cell-Based Immunotherapies to Fight HIV: How Far from a Success Story? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 17:1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Le Gall S, Stamegna P, Walker BD. 2007. Portable flanking sequences modulate CTL epitope processing. J Clin Invest 117:3563–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tung FY, Rinaldo CR Jr., Montelaro RC. 1998. Replication-defective HIV as a vaccine candidate. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 14:1247–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tung FY, Tung JK, Pallikkuth S, Pahwa S, Fischl MA. 2016. A therapeutic HIV-1 vaccine enhances anti-HIV-1 immune responses in patients under highly active antiretroviral therapy. Vaccine 34:2225–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fischer W, Perkins S, Theiler J, Bhattacharya T, Yusim K, Funkhouser R, Kuiken C, Haynes B, Letvin NL, Walker BD, Hahn BH, Korber BT. 2007. Polyvalent vaccines for optimal coverage of potential T-cell epitopes in global HIV-1 variants. Nature Medicine 13:100–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barouch DH, O’Brien KL, Simmons NL, King SL, Abbink P, Maxfield LF, Sun YH, La Porte A, Riggs AM, Lynch DM, Clark SL, Backus K, Perry JR, Seaman MS, Carville A, Mansfield KG, Szinger JJ, Fischer W, Muldoon M, Korber B. 2010. Mosaic HIV-1 vaccines expand the breadth and depth of cellular immune responses in rhesus monkeys. Nature Medicine 16:319–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dan Kathryn, Erica Smith K, Anna Stanley K,, Liu J, Abbink P, Lori Michael, Dugast A-S, Alter G, Ferguson M, Li W, Patricia Moss B, Elena James, Leigh Erik, Rao M, Tovanabutra S, Sanders-Buell E, Weijtens M, Maria, Schuitemaker H, Merlin Jerome, Bette Nelson. 2013. Protective Efficacy of a Global HIV-1 Mosaic Vaccine against Heterologous SHIV Challenges in Rhesus Monkeys. Cell 155:531–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Janes H, Friedrich DP, Krambrink A, Smith RJ, Kallas EG, Horton H, Casimiro DR, Carrington M, Geraghty DE, Gilbert PB, McElrath MJ, Frahm N. 2013. Vaccine-induced gag-specific T cells are associated with reduced viremia after HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis 208:1231–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barouch DH, Liu J, Peter L, Abbink P, Iampietro MJ, Cheung A, Alter G, Chung A, Dugast AS, Frahm N, McElrath MJ, Wenschuh H, Reimer U, Seaman MS, Pau MG, Weijtens M, Goudsmit J, Walsh SR, Dolin R, Baden LR. 2013. Characterization of humoral and cellular immune responses elicited by a recombinant adenovirus serotype 26 HIV-1 Env vaccine in healthy adults (IPCAVD 001). J Infect Dis 207:248–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Barouch DH, Tomaka FL, Wegmann F, Stieh DJ, Alter G, Robb ML, Michael NL, Peter L, Nkolola JP, Borducchi EN, Chandrashekar A, Jetton D, Stephenson KE, Li W, Korber B, Tomaras GD, Montefiori DC, Gray G, Frahm N, McElrath MJ, Baden L, Johnson J, Hutter J, Swann E, Karita E, Kibuuka H, Mpendo J, Garrett N, Mngadi K, Chinyenze K, Priddy F, Lazarus E, Laher F, Nitayapan S, Pitisuttithum P, Bart S, Campbell T, Feldman R, Lucksinger G, Borremans C, Callewaert K, Roten R, Sadoff J, Scheppler L, Weijtens M, Feddes-de Boer K, van Manen D, Vreugdenhil J, Zahn R, Lavreys L, et al. 2018. Evaluation of a mosaic HIV-1 vaccine in a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1/2a clinical trial (APPROACH) and in rhesus monkeys (NHP 13–19). Lancet (London, England) 392:232–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rolland M, Nickle DC, Mullins JI. 2007. HIV-1 group M conserved elements vaccine. PLoS Pathog 3:e157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Letourneau S, Im EJ, Mashishi T, Brereton C, Bridgeman A, Yang H, Dorrell L, Dong T, Korber B, McMichael AJ, Hanke T. 2007. Design and pre-clinical evaluation of a universal HIV-1 vaccine. PLoS One 2:e984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Borthwick N, Ahmed T, Ondondo B, Hayes P, Rose A, Ebrahimsa U, Hayton EJ, Black A, Bridgeman A, Rosario M, Hill AV, Berrie E, Moyle S, Frahm N, Cox J, Colloca S, Nicosia A, Gilmour J, McMichael AJ, Dorrell L, Hanke T. 2014. Vaccine-elicited human T cells recognizing conserved protein regions inhibit HIV-1. Mol Ther 22:464–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mutua G, Farah B, Langat R, Indangasi J, Ogola S, Onsembe B, Kopycinski JT, Hayes P, Borthwick NJ, Ashraf A, Dally L, Barin B, Tillander A, Gilmour J, De Bont J, Crook A, Hannaman D, Cox JH, Anzala O, Fast PE, Reilly M, Chinyenze K, Jaoko W, Hanke T, Hiv-Core 004 Study Group T. 2016. Broad HIV-1 inhibition in vitro by vaccine-elicited CD8(+) T cells in African adults. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 3:16061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mothe B, Manzardo C, Sanchez-Bernabeu A, Coll P, Moron-Lopez S, Puertas MC, Rosas-Umbert M, Cobarsi P, Escrig R, Perez-Alvarez N, Ruiz I, Rovira C, Meulbroek M, Crook A, Borthwick N, Wee EG, Yang H, Miro JM, Dorrell L, Clotet B, Martinez-Picado J, Brander C, Hanke T. 2019. Therapeutic Vaccination Refocuses T-cell Responses Towards Conserved Regions of HIV-1 in Early Treated Individuals (BCN 01 study). EClinicalMedicine 11:65–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ondondo B, Murakoshi H, Clutton G, Abdul-Jawad S, Wee EGT, Gatanaga H, Oka S, McMichael AJ, Takiguchi M, Korber B, Hanke T. 2016. Novel Conserved-region T-cell Mosaic Vaccine With High Global HIV-1 Coverage Is Recognized by Protective Responses in Untreated Infection. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy 24:832–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morrow MP, Tebas P, Yan J, Ramirez L, Slager A, Kraynyak K, Diehl M, Shah D, Khan A, Lee J, Boyer J, Kim JJ, Sardesai NY, Weiner DB, Bagarazzi ML. 2015. Synthetic Consensus HIV-1 DNA Induces Potent Cellular Immune Responses and Synthesis of Granzyme B, Perforin in HIV Infected Individuals. Molecular Therapy 23:591–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hu X, Valentin A, Dayton F, Kulkarni V, Alicea C, Rosati M, Chowdhury B, Gautam R, Broderick KE, Sardesai NY, Martin MA, Mullins JI, Pavlakis GN, Felber BK. 2016. DNA Prime-Boost Vaccine Regimen To Increase Breadth, Magnitude, and Cytotoxicity of the Cellular Immune Responses to Subdominant Gag Epitopes of Simian Immunodeficiency Virus and HIV. J Immunol 197:3999–4013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gaiha GD, Rossin EJ, Urbach J, Landeros C, Collins DR, Nwonu C, Muzhingi I, Anahtar MN, Waring OM, Piechocka-Trocha A, Waring M, Worrall DP, Ghebremichael MS, Newman RM, Power KA, Allen TM, Chodosh J, Walker BD. 2019. Structural topology defines protective CD8 + T cell epitopes in the HIV proteome. Science. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sáez-Cirión A, Sinet M, Shin SY, Urrutia A, Versmisse P, Lacabaratz C, Boufassa F, Avettand-Fènoël V, Rouzioux C, Delfraissy J-F, Barré-Sinoussi F, Lambotte O, Venet A, Pancino G. 2009. Heterogeneity in HIV Suppression by CD8 T Cells from HIV Controllers: Association with Gag-Specific CD8 T Cell Responses. The Journal of Immunology 182:7828–7837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hersperger AR, Pereyra F, Nason M, Demers K, Sheth P, Shin LY, Kovacs CM, Rodriguez B, Sieg SF, Teixeira-Johnson L, Gudonis D, Goepfert PA, Lederman MM, Frank I, Makedonas G, Kaul R, Walker BD, Betts MR. 2010. Perforin expression directly ex vivo by HIV-specific CD8 T-cells is a correlate of HIV elite control. PLoS pathogens 6:e1000917-e1000917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chen H, Ndhlovu ZM, Liu D, Porter LC, Fang JW, Darko S, Brockman MA, Miura T, Brumme ZL, Schneidewind A, Piechocka-Trocha A, Cesa KT, Sela J, Cung TD, Toth I, Pereyra F, Yu XG, Douek DC, Kaufmann DE, Allen TM, Walker BD. 2012. TCR clonotypes modulate the protective effect of HLA class I molecules in HIV-1 infection. Nature Immunology 13:691–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lu W, Arraes LC, Ferreira WT, Andrieu J-M. 2004. Therapeutic dendritic-cell vaccine for chronic HIV-1 infection. Nature Medicine 10:1359–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hess C, Altfeld M, Thomas SY, Addo MM, Rosenberg ES, Allen TM, Draenert R, Eldrige RL, Van Lunzen J, Stellbrink H-J, Walker BD, Luster AD. 2004. HIV-1 specific CD8+ T cells with an effector phenotype and control of viral replication. The Lancet 363:863–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lévy Y, Thiébaut R, Montes M, Lacabaratz C, Sloan L, King B, Pérusat S, Harrod C, Cobb A, Roberts LK, Surenaud M, Boucherie C, Zurawski S, Delaugerre C, Richert L, Chêne G, Banchereau J, Palucka K. 2014. Dendritic cell-based therapeutic vaccine elicits polyfunctional HIV-specific T-cell immunity associated with control of viral load. European Journal of Immunology 44:2802–2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Casazza JP, Bowman KA, Adzaku S, Smith EC, Enama ME, Bailer RT, Price DA, Gostick E, Gordon IJ, Ambrozak DR, Nason MC, Roederer M, Andrews CA, Maldarelli FM, Wiegand A, Kearney MF, Persaud D, Ziemniak C, Gottardo R, Ledgerwood JE, Graham BS, Koup RA, Team VRCS. 2013. Therapeutic vaccination expands and improves the function of the HIV-specific memory T-cell repertoire. J Infect Dis 207:1829–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Harari A, Rozot V, Cavassini M, Enders FB, Vigano S, Tapia G, Castro E, Burnet S, Lange J, Moog C, Garin D, Costagliola D, Autran B, Pantaleo G, Bart P-A. 2012. NYVAC immunization induces polyfunctional HIV-specific T-cell responses in chronically-infected, ART-treated HIV patients. European Journal of Immunology 42:3038–3048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lind A, Brekke K, Sommerfelt M, Holmberg JO, Aass HCD, Baksaas I, Sørensen B, Dyrhol-Riise AM, Kvale D. 2013. Boosters of a therapeutic HIV-1 vaccine induce divergent T cell responses related to regulatory mechanisms. 31:4611–4618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chiu YL, Shan L, Huang H, Haupt C, Bessell C, Canaday DH, Zhang H, Ho YC, Powell JD, Oelke M, Margolick JB, Blankson JN, Griffin DE, Schneck JP. 2014. Sprouty-2 regulates HIV-specific T cell polyfunctionality. Journal of Clinical Investigation 124:198–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Macatangay BJC, Szajnik ME, Whiteside TL, Riddler SA, Rinaldo CR. 2010. Regulatory T Cell Suppression of Gag-Specific CD8+ T Cell Polyfunctional Response After Therapeutic Vaccination of HIV-1-Infected Patients on ART. 5:e9852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Almeida JR, Price DA, Papagno L, Arkoub ZA, Sauce D, Bornstein E, Asher TE, Samri A, Schnuriger A, Theodorou I, Costagliola D, Rouzioux C, Agut H, Marcelin AG, Douek D, Autran B, Appay V. 2007. Superior control of HIV-1 replication by CD8+ T cells is reflected by their avidity, polyfunctionality, and clonal turnover. Journal of Experimental Medicine 204:2473–2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Berger CT, Frahm N, Price DA, Mothe B, Ghebremichael M, Hartman KL, Henry LM, Brenchley JM, Ruff LE, Venturi V, Pereyra F, Sidney J, Sette A, Douek DC, Walker BD, Kaufmann DE, Brander C. 2011. High-functional-avidity cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses to HLA-B-restricted Gag-derived epitopes associated with relative HIV control. J Virol 85:9334–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schaubert KL, Price DA, Frahm N, Li J, Ng HL, Joseph A, Paul E, Majumder B, Ayyavoo V, Gostick E, Adams S, Marincola FM, Sewell AK, Altfeld M, Brenchley JM, Douek DC, Yang OO, Brander C, Goldstein H, Kan-Mitchell J. 2007. Availability of a diversely avid CD8+ T cell repertoire specific for the subdominant HLA-A2-restricted HIV-1 Gag p2419–27 epitope. J Immunol 178:7756–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Billeskov R, Wang Y, Solaymani-Mohammadi S, Frey B, Kulkarni S, Andersen P, Agger EM, Sui Y, Berzofsky JA. 2017. Low Antigen Dose in Adjuvant-Based Vaccination Selectively Induces CD4 T Cells with Enhanced Functional Avidity and Protective Efficacy. The Journal of Immunology 198:3494–3506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hu Z, Wang J, Wan Y, Zhu L, Ren X, Qiu S, Ren Y, Yuan S, Ding X, Chen J, Qiu C, Sun J, Zhang X, Xiang J, Qiu C, Xu J. 2014. Boosting functional avidity of CD8+ T cells by vaccinia virus vaccination depends on intrinsic T-cell MyD88 expression but not the inflammatory milieu. Journal of virology 88:5356–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bennett MS, Joseph A, Ng HL, Goldstein H, Yang OO. 2010. Fine-tuning of T-cell receptor avidity to increase HIV epitope variant recognition by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. AIDS 24:2619–2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kuball J, Hauptrock B, Malina V, Antunes E, Voss RH, Wolfl M, Strong R, Theobald M, Greenberg PD. 2009. Increasing functional avidity of TCR-redirected T cells by removing defined N-glycosylation sites in the TCR constant domain. J Exp Med 206:463–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chaillon A, Gianella S, Dellicour S, Rawlings SA, Schlub TE, Faria De Oliveira M, Ignacio C, Porrachia M, Vrancken B, Smith DM. 2020. HIV persists throughout deep tissues with repopulation from multiple anatomical sources. J Clin Invest doi: 10.1172/JCI134815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bronnimann MP, Skinner PJ, Connick E. 2018. The B-Cell Follicle in HIV Infection: Barrier to a Cure. Front Immunol 9:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Connick E, Folkvord JM, Lind KT, Rakasz EG, Miles B, Wilson NA, Santiago ML, Schmitt K, Stephens EB, Kim HO, Wagstaff R, Li S, Abdelaal HM, Kemp N, Watkins DI, MaWhinney S, Skinner PJ. 2014. Compartmentalization of Simian Immunodeficiency Virus Replication within Secondary Lymphoid Tissues of Rhesus Macaques Is Linked to Disease Stage and Inversely Related to Localization of Virus-Specific CTL. The Journal of Immunology 193:5613–5625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pallikkuth S, Sharkey M, Babic DZ, Gupta S, Stone GW, Fischl MA, Stevenson M, Pahwa S. 2016. Peripheral T Follicular Helper Cells Are the Major HIV Reservoir within Central Memory CD4 T Cells in Peripheral Blood from Chronically HIV-Infected Individuals on Combination Antiretroviral Therapy. Journal of Virology 90:2718–2728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Leong YA, Chen Y, Ong HS, Wu D, Man K, Deleage C, Minnich M, Meckiff BJ, Wei Y, Hou Z, Zotos D, Fenix KA, Atnerkar A, Preston S, Chipman JG, Beilman GJ, Allison CC, Sun L, Wang P, Xu J, Toe JG, Lu HK, Tao Y, Palendira U, Dent AL, Landay AL, Pellegrini M, Comerford I, McColl SR, Schacker TW, Long HM, Estes JD, Busslinger M, Belz GT, Lewin SR, Kallies A, Yu D. 2016. CXCR5+ follicular cytotoxic T cells control viral infection in B cell follicles. Nature Immunology 17:1187–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Schaerli P, Willimann K, Lang AB, Lipp M, Loetscher P, Moser B. 2000. CXC chemokine receptor 5 expression defines follicular homing T cells with B cell helper function. J Exp Med 192:1553–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ayala VI, Deleage C, Trivett MT, Jain S, Coren LV, Breed MW, Kramer JA, Thomas JA, Estes JD, Lifson JD, Ott DE. 2017. CXCR5-Dependent Entry of CD8 T Cells into Rhesus Macaque B-Cell Follicles Achieved through T-Cell Engineering. Journal of virology 91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mylvaganam GH, Rios D, Abdelaal HM, Iyer S, Tharp G, Mavigner M, Hicks S, Chahroudi A, Ahmed R, Bosinger SE, Williams IR, Skinner PJ, Velu V, Amara RR. 2017. Dynamics of SIV-specific CXCR5+ CD8 T cells during chronic SIV infection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 114:1976–1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Huot N, Jacquelin B, Garcia-Tellez T, Rascle P, Ploquin MJ, Madec Y, Reeves RK, Derreudre-Bosquet N, Müller-Trutwin M. 2017. Natural killer cells migrate into and control simian immunodeficiency virus replication in lymph node follicles in African green monkeys. Nature medicine 23:1277–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Petrovas C, Ferrando-Martinez S, Gerner MY, Casazza JP, Pegu A, Deleage C, Cooper A, Hataye J, Andrews S, Ambrozak D, Del Rio Estrada PM, Boritz E, Paris R, Moysi E, Boswell KL, Ruiz-Mateos E, Vagios I, Leal M, Ablanedo-Terrazas Y, Rivero A, Gonzalez-Hernandez LA, McDermott AB, Moir S, Reyes-Teran G, Docobo F, Pantaleo G, Douek DC, Betts MR, Estes JD, Germain RN, Mascola JR, Koup RA. 2017. Follicular CD8 T cells accumulate in HIV infection and can kill infected cells in vitro via bispecific antibodies. Sci Transl Med 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gaufin T, Gautam R, Kasheta M, Ribeiro R, Ribka E, Barnes M, Pattison M, Tatum C, MacFarland J, Montefiori D, Kaur A, Pandrea I, Apetrei C. 2009. Limited ability of humoral immune responses in control of viremia during infection with SIVsmmD215 strain. Blood 113:4250–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Serra-Peinado C, Grau-Exposito J, Luque-Ballesteros L, Astorga-Gamaza A, Navarro J, Gallego-Rodriguez J, Martin M, Curran A, Burgos J, Ribera E, Raventos B, Willekens R, Torrella A, Planas B, Badia R, Garcia F, Castellvi J, Genesca M, Falco V, Buzon MJ. 2019. Expression of CD20 after viral reactivation renders HIV-reservoir cells susceptible to Rituximab. Nat Commun 10:3705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Veenhuis RT, Clements JE, Gama L. 2019. HIV Eradication Strategies: Implications for the Central Nervous System. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 16:96–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lescure FX, Moulignier A, Savatovsky J, Amiel C, Carcelain G, Molina JM, Gallien S, Pacanovski J, Pialoux G, Adle-Biassette H, Gray F. 2013. CD8 encephalitis in HIV-infected patients receiving cART: a treatable entity. Clin Infect Dis 57:101–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Honeycutt JB, Thayer WO, Baker CE, Ribeiro RM, Lada SM, Cao Y, Cleary RA, Hudgens MG, Richman DD, Garcia JV. 2017. HIV persistence in tissue macrophages of humanized myeloid-only mice during antiretroviral therapy. Nat Med 23:638–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Avalos CR, Abreu CM, Queen SE, Li M, Price S, Shirk EN, Engle EL, Forsyth E, Bullock BT, Mac Gabhann F, Wietgrefe SW, Haase AT, Zink MC, Mankowski JL, Clements JE, Gama L. 2017. Brain Macrophages in Simian Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected, Antiretroviral-Suppressed Macaques: a Functional Latent Reservoir. mBio 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Clayton KL, Collins DR, Lengieza J, Ghebremichael M, Dotiwala F, Lieberman J, Walker BD. 2018. Resistance of HIV-infected macrophages to CD8(+) T lymphocyte-mediated killing drives activation of the immune system. Nature immunology 19:475–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Elliott JH, McMahon JH, Chang CC, Lee SA, Hartogensis W, Bumpus N, Savic R, Roney J, Hoh R, Solomon A, Piatak M, Gorelick RJ, Lifson J, Bacchetti P, Deeks SG, Lewin SR. 2015. Short-term administration of disulfiram for reversal of latent HIV infection: a phase 2 dose-escalation study. The Lancet HIV 2:e520–e529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]