Abstract

Objectives:

The aim of this study was to comprehensively assess the association of multiple lipid measures with incident peripheral artery disease (PAD).

Approach and Results:

We used Cox proportional hazards models to characterize the associations of each of the fasting lipid measures (total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol [LDL-C], high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [HDL-C], triglycerides, remnant lipoprotein cholesterol [RLP-C], LDL-TG [low-density lipoprotein-triglycerides], small dense LDL-C [sdLDL-C], and Apo-E containing HDL-C [Apo-E-HDL]) with incident PAD identified by pertinent ICD-9-CM hospital discharge codes (e.g., 440.2) among 8,330 black and white ARIC participants (mean age 62.8 [SD 5.6] y) free of PAD at baseline (1996–98) through 2015. Since lipid traits are biologically correlated to each other, we also conducted principal component analysis to identify underlying components for PAD risk. There were 246 incident PAD cases with a median follow-up of 17 years. After accounting for potential confounders, the following lipid measures were significantly associated with PAD (hazard ratio per 1-SD increment [decrement for HDL-C and Apo-E-HDL]): triglycerides 1.21 (95%CI 1.08–1.36); RLP-C 1.18 (1.08–1.29); LDL-TG 1.18 (1.05–1.33); HDL-C 1.39 (1.16–1.67); and Apo-E-HDL 1.27 (1.07–1.51). The principal component analysis identified three components (1: mainly loaded by triglycerides, RLP-C, LDL-TG, and sdLDL-C; 2: by HDL-C and Apo-E-HDL; 3: by LDL-C, and RLP-C). Components 1 and 2 showed independent associations with incident PAD.

Conclusions:

Triglyceride-related and HDL-related lipids were independently associated with incident PAD, which has implications on preventive strategies for PAD. However, none of the novel lipid measures outperformed conventional ones.

Keywords: peripheral artery disease, lipids and lipoproteins, triglycerides, Peripheral Vascular Disease, Atherosclerosis, Lipids and Cholesterol

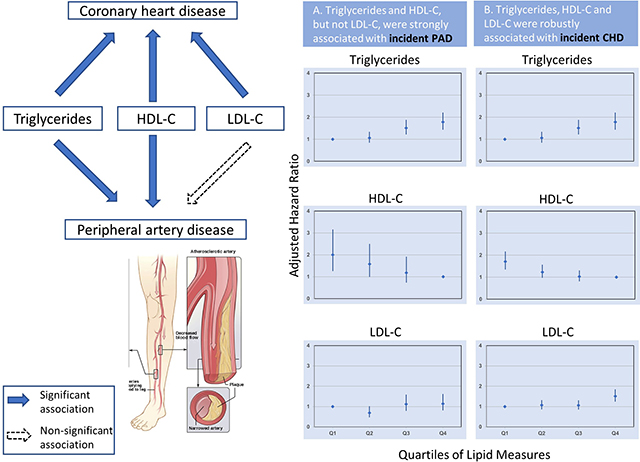

Graphical Abstract

(Left) Blue arrows represent the association of each lipid with the outcomes, respectively. Black dashed arrow represents non-significant association. (Right) The left column of the plot (A) shows the adjusted hazard ratio of peripheral artery disease by quartiles of each lipid. The right column of the plot (B) shows the adjusted hazard ratio of coronary heart disease by quartiles of each lipid. The model was adjusted for age, race, sex, BMI, smoking, alcohol use, hs-CRP, education level, systolic blood pressure, diabetes, prevalent coronary heart disease, prevalent stroke, antihypertensive drugs use, and lipid-lowering medication use. Triglycerides- and HDL-related lipids are similarly associated with incident peripheral artery disease whereas LDL-C is more strongly associated with coronary heart disease. HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C = low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Introduction

Lower-extremity peripheral artery disease (PAD) is estimated to affect ~237 million adults globally.1 PAD considerably increases the risk of other cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.2 PAD is also associated with adverse lower-extremity outcomes, including intermittent claudication, reduced leg function, and leg amputation.3 The first manifestation of PAD can be an ulcer or gangrene, conditions indicating an extremely high risk of limb loss.4, 5 Thus, insights into the risk factors of PAD and identification of individuals at high risk of PAD are important to enable preventive measures (e.g., smoking cessation). Although risk factors are often considered consistent across different atherosclerotic disease phenotypes,6 their contributions actually vary across vascular beds (e.g., smoking is an especially strong risk factor for PAD, whereas blood lipids are strongly related to coronary heart disease [CHD] 7, 8), warranting investigations specifically for PAD.

Dyslipidemia is considered a risk factor of PAD.9 However, our understanding of dyslipidemia in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular disease has changed considerably in the last several years. For example, genetic studies and randomized trials suggest that high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) may not be causally related to CHD risk.10 On the other hand, a triglyceride-lowering medication, icosapent ethyl, significantly reduces the risk of CHD and stroke among statin-treated participants.11 Genetic evidence also supports a causal role of triglycerides and triglyceride-rich lipoproteins in the progression of atherosclerosis.12 Nonetheless, to evaluate to what extent these new findings can be translated to PAD, we need a large comprehensive and representative study assessing multiple lipid measures for incident PAD.

Therefore, we investigated conventional (total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [HDL-C], low-density lipoprotein cholesterol [LDL-C], and triglycerides) and novel (small dense LDL-C [sdLDL-C], remnant lipoprotein cholesterol [RLP-C], LDL-triglyceride [LDL-TG], Apo-E containing HDL-C [Apo-E-HDL]) lipid measures and their associations with incident PAD in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study, a community-based mostly biracial cohort of middle-aged and older adults. To assess whether some lipid measures may differentially predict PAD, we also compared their relationships to CHD.

Material and methods

Although the study data will not be made available for the purposes of replication, investigators can request access to the ARIC Study data by contacting its coordinating center at the University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill. Data sharing policy of ARIC can be found at: https://sites.cscc.unc.edu/aric/distribution-agreements.

Study Design and Population

The ARIC Study is an ongoing prospective cohort of 15,792 predominantly white and black individuals aged between 45 and 64 years at visit 1 (between 1987–1989) from four US communities (Forsyth County, North Carolina; Jackson, Mississippi; suburban Minneapolis, Minnesota; and Washington County, Maryland). Of those, 11,656 participants attended visit 4 in 1996–98, which was the baseline of the present study, given the availability of conventional and novel blood lipid measures. We excluded participants whose race was other than white or black (n=31), and who had prevalent PAD at baseline, defined as ankle-brachial index ≤0.9, intermittent claudication, or self-reported history of leg revascularization at visit 1 or any hospitalization with PAD diagnosis prior to visit 4 (n=513). To get accurate blood lipid measures, we also excluded 997 participants without fasting for 12 hours. Additionally, 1,785 participants with missing data on lipid measures (including 150 participants with triglycerides >400 mg/dL precluding the use of the Friedewald formula noted below) or other covariates of interest were excluded, for a final analytic set of 8,330 individuals (Supplemental Figure I). Compared to 8,330 participants included in our analysis, the 1,785 individuals excluded due to missing data on lipid measures or covariates were more likely to be Black, male, current smokers and to have higher systolic blood pressure and higher prevalence of diabetes, while other factors were largely similar (e.g., age, body mass index [BMI], prevalent CHD and stroke, and lipid-lowering drug use) (Supplemental Table I).

Blood lipid measures

The widely used fasting blood total cholesterol, HDL-C, and triglycerides were measured using enzymatic measures during visit 4 following standardized procedures described elsewhere.13 LDL-C was calculated using the Friedewald formula 14: LDL-C=total cholesterol - (triglycerides/5 + HDL-C). RLP-C, LDL-TG, sdLDL-C, and Apo-E-HDL were measured using visit 4 blood samples stored at −70° C by fully automated detergent-based homogeneous methods (Denka Seiken, Tokyo, Japan).15–18

The biological properties of each of these novel lipid measures have been described elsewhere. Briefly, RLP-C quantifies the cholesterol content of RLP particles, one of the most atherogenic triglyceride-rich lipoproteins.19, 20 LDL-TG measures the triglycerides content of LDL, which is indicative of dysfunctional LDL metabolism and correlated with elevated small dense LDL levels.21, 22 sdLDL-C is the cholesterol content of small, dense LDL particles, which is highly correlated with plasma triglycerides level and considered more atherogenic than large, buoyant LDL particles.17 Based on these properties, we categorized triglycerides, RLP-C, LDL-TG, and sdLDL-C as triglycerides-related lipid measures. Apo-E-HDL is a subtype of HDL-C with the presence of apolipoprotein E.23

Covariates

Age, race, sex, smoking status, and alcohol use status at visit 4 were based on self-report. Smoking status and alcohol use status were each classified into three categories: current, former, and never user. Education level was evaluated at visit 1 and divided into less than high school education, high school to less than completed college, or at least a college degree. BMI was calculated as weight (kg) / height2 (m). Blood pressures were measured in duplicate after a 5-minute rest in a seated position, and the mean of the two measurements was recorded. Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg, a diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg, or use of antihypertensive medications. Diabetes was defined as a fasting glucose level of ≥126 mg/dL, self-reported physician diagnosis, or use of anti-diabetic medications. Medication use over the prior two weeks was verified by reviewing medication containers that participants brought to the visit. Lipid-lowering medications include statins, bile sequestrants, fibrates, niacin, and antihyperlipidemic medications. Plasma C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) was measured in 2008 on plasma frozen at −70°C from Visit 4 by the immunoturbidimetric assay using the Siemens (Dade Behring) BNII analyzer (Dade Behring, Deerfield, Ill), with a reliability coefficient of 0.99 24. History of CHD was defined by self-reported history of myocardial infarction or prior coronary revascularization and electrocardiogram evidence of myocardial infarction at visit 1, or subsequent adjudicated CHD events between visit 1 and visit 4. History of stroke was similarly defined as a self-reported history of stroke at visit 1 or adjudicated stroke events between visit 1 and visit 4.

Outcomes

Incident clinical PAD was defined as hospitalization with the following ICD-9-CM codes according to previous literature 25–27: atherosclerosis of native arteries of the extremities, unspecified (440.20); atherosclerosis of native arteries of the extremities with intermittent claudication (440.21); atherosclerosis of native arteries of the extremities with rest pain (440.22); atherosclerosis of native arteries of the extremities with ulceration (440.23); atherosclerosis of native arteries of the extremities with gangrene (440.24); other atherosclerosis of native arteries of the extremities (440.29); atherosclerosis of bypass graft of the extremities (440.3); atherosclerosis of other specified arteries (440.8); endarterectomy, lower limb arteries (38.18); aorta-iliac-femoral bypass (39.25); other (peripheral) vascular shunt or bypass (39.25); angioplasty or atherectomy of other non-coronary vessel(s) (39.50). Participants were followed until incident PAD, date of death, loss to follow-up, or September 30, 2015, whichever came first.

Incident CHD events were defined as definite or probable myocardial infarction or fatal CHD according to adjudication by a physician panel.28

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using Stata 15 software (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). A two-tailed p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We first summarized baseline characteristics by quartiles of each lipid measure and assessed the Pearson correlation coefficients between the eight lipid measures. We then evaluated the cumulative incidence of PAD using the Kaplan-Meier method according to quartiles of each lipid measure. Subsequently, we used Cox proportional hazards regression to quantify the associations of each lipid measures with incident PAD to account for potential confounders. We modeled each lipid measure continuously (per SD increment) and categorically (quartiles). Cox models were adjusted for age, race, sex, education level, BMI, smoking and alcohol status (current, former, and never), systolic blood pressure, baseline antihypertensive medication use, hs-CRP, diabetes, prevalent CHD, prevalent stroke, and baseline lipid-lowering medication use.

As a sensitivity analysis, we evaluated whether novel lipid measures demonstrated associations independent of conventional lipid measures. Specifically, when we analyzed novel lipid measures, we ran additional models including triglycerides or HDL-C as a covariate separately. We also repeated our analysis after excluding participants taking lipid-lowering medication.

We performed subgroup analyses by age and sex, respectively, modeling each lipid measure continuously with the same covariates and the interaction term of the subgroup variable and the lipid measure. The interaction was tested using the likelihood ratio test. We also conducted Cox proportional hazards regression with CHD as an outcome after restricting to participants without prevalent CHD at baseline (N=8,006). Covariates adjusted were the same as described above, except excluding prevalent CHD.

To assess the potential clustering effects of different blood lipids, we also conducted principal component analysis to identify uncorrelated components out of blood lipids and modeled them for PAD risk. We focused on components that together could explain more than 80% of total variance or those with eigenvalues > 1. In this analysis, we did not include total cholesterol since it is not a lipid component with specific biology.

Finally, we evaluated whether each of these lipid measures can improve risk prediction of PAD beyond established predictors. In the base Cox proportional hazards model, we included predictors in the PAD risk prediction model developed in the Framingham Heart Study (except for total cholesterol since it is one of our blood lipid measures of interest): age, sex, systolic blood pressure, smoking status, presence of diabetes, and presence of CHD.29 Each lipid measure was added to the base model as a continuous variable to predict the 10- and 20-year risk of PAD. In terms of prediction statistics, we calculated Harrell’s c-statistic as well as categorical net reclassification improvement (NRI). Since there are no established risk categories for PAD, we selected cutoffs of 5% and 10% for 10-year risk and 10% and 20% for 20-year risk, based on a previous study.30 We also evaluated calibration based on Hosmer-Lemeshow χ2 and calibration plots of observed and predicted risk of PAD.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Out of 8,330 participants (mean age 62.8 [SD 5.6]), 4,826 (57.9%) were female and 1,561 (18.7%) were African American (Table 1). When baseline characteristics were compared according to quartiles of triglycerides (as shown below, triglycerides was one of lipid measures most robustly associated with PAD in our study), those with higher triglycerides were more likely to have higher BMI, systolic blood pressure, and hs-CRP levels, but less likely to be African Americans and never smokers. They were also more likely to have hypertension, prevalent CHD and stroke, and diabetes. We observed similar patterns when baseline characteristics were compared by quartiles of RLP-C, LDL-TG, and sdLDL-C (Supplemental Tables II–IV). As anticipated, the opposite patterns were observed for HDL-C or Apo-E-HDL, with higher levels related to lower risk factor profile (Supplemental Table V and VI). For total cholesterol and LDL-C, higher levels were related to higher blood pressure but lower prevalence of CHD and the use of lipid-lowering medications (Supplemental Table VII and VIII). We observed several strong correlations (e.g., HDL-C and Apo-E-HDL, correlation coefficient = 0.85) (Supplemental Table IX).

Table1.

Baseline Characteristics by Quartile of Fasting Triglycerides (mg/dL)

| Total | Q1:30.0–88.0 | Q2:88.1–121.0 | Q3:121.1–170.0 | Q4:170.1–400.0 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=8,330 | N=2,108 | N=2,100 | N=2,066 | N=2,056 | ||

| Age, y | 62.8 (5.6) | 62.7 (5.7) | 62.8 (5.7) | 62.8 (5.6) | 63.1 (5.6) | 0.130 |

| Female | 4,826 (57.9%) | 1,186 (56.3%) | 1,252 (59.6%) | 1,169 (56.6%) | 1,219 (59.3%) | 0.047 |

| Black | 1,561 (18.7%) | 635 (30.1%) | 468 (22.3%) | 296 (14.3%) | 162 (7.9%) | <0.001 |

| Education level | <0.001 | |||||

| <High school (<12) | 1,447 (17.4%) | 374 (17.7%) | 361 (17.2%) | 364 (17.6%) | 348 (16.9%) | |

| <College (12–16) | 3,570 (42.9%) | 827 (39.2%) | 848 (40.4%) | 889 (43.0%) | 1,006 (48.9%) | |

| ≥College (>16) | 3,313 (39.8%) | 907 (43.0%) | 891 (42.4%) | 813 (39.4%) | 702 (34.1%) | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.6 (5.6) | 27.1 (5.5) | 28.5 (5.7) | 29.2 (5.6) | 29.8 (5.2) | <0.001 |

| SBP, mmHg | 126.8 (18.7) | 124.9 (19.4) | 126.1 (18.5) | 127.5 (18.0) | 128.8 (18.5) | <0.001 |

| DBP, mmHg | 70.8 (10.2) | 70.7 (10.4) | 70.8 (10.1) | 71.0 (10.0) | 70.5 (10.1) | 0.400 |

| Hypertension | 4,207 (50.5%) | 924 (43.8%) | 1,025 (48.8%) | 1,059 (51.3%) | 1,199 (58.3%) | <0.001 |

| Antihypertensive drugs use | 3,445 (41.4%) | 737 (35.0%) | 830 (39.5%) | 862 (41.7%) | 1,016 (49.4%) | <0.001 |

| C-Reactive Protein, mg/L | 2.3 (1.0–5.3) | 1.6 (0.8–4.1) | 2.2 (1.0–4.9) | 2.6 (1.2–5.6) | 3.1 (1.5–6.1) | <0.001 |

| Smoking status | 0.013 | |||||

| Never smoker | 3,579 (43.0%) | 911 (43.2%) | 926 (44.1%) | 884 (42.8%) | 858 (41.7%) | |

| Former smoker | 3,630 (43.6%) | 895 (42.5%) | 868 (41.3%) | 911 (44.1%) | 956 (46.5%) | |

| Current smoker | 1,121 (13.5%) | 302 (14.3%) | 306 (14.6%) | 271 (13.1%) | 242 (11.8%) | |

| Alcohol use status | 0.370 | |||||

| Never drinker | 1,697 (20.4%) | 436 (20.7%) | 432 (20.6%) | 394 (19.1%) | 435 (21.2%) | |

| Former drinker | 2,399 (28.8%) | 581 (27.6%) | 628 (29.9%) | 596 (28.8%) | 594 (28.9%) | |

| Current drinker | 4,234 (50.8%) | 1,091 (51.8%) | 1,040 (49.5%) | 1,076 (52.1%) | 1,027 (50.0%) | |

| Prevalent coronary heart disease | 634 (7.6%) | 117 (5.6%) | 140 (6.7%) | 185 (9.0%) | 192 (9.3%) | <0.001 |

| Incident coronary heart disease | 726 (8.7%) | 142 (6.7%) | 144 (6.9%) | 200 (9.7%) | 240 (11.7%) | <0.001 |

| Prevalent stroke | 166 (2.0%) | 36 (1.7%) | 41 (2.0%) | 40 (1.9%) | 49 (2.4%) | 0.470 |

| Diabetes | 1,085 (13.0%) | 177 (8.4%) | 212 (10.1%) | 257 (12.4%) | 439 (21.4%) | <0.001 |

| Lipid-lowering medication use | 1,168 (14.0%) | 141 (6.7%) | 251 (12.0%) | 318 (15.4%) | 458 (22.3%) | <0.001 |

| Incident PAD | 246 (3.0%) | 43 (2.0%) | 46 (2.2%) | 69 (3.3%) | 88 (4.3%) | <0.001 |

Values are mean (SD), or n (%).

Abbreviation: DBP, diastolic blood pressure; PAD, peripheral artery disease; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Association between Lipid Measures and PAD

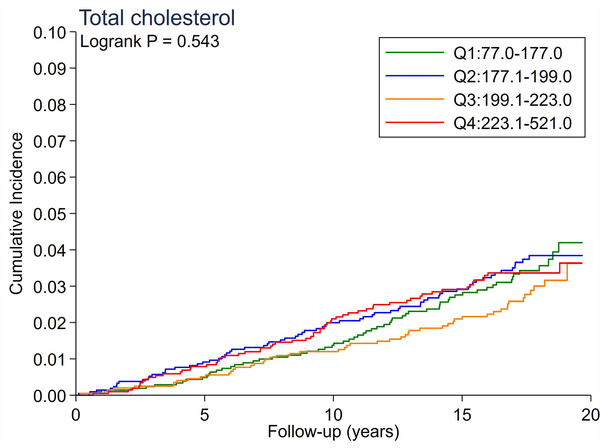

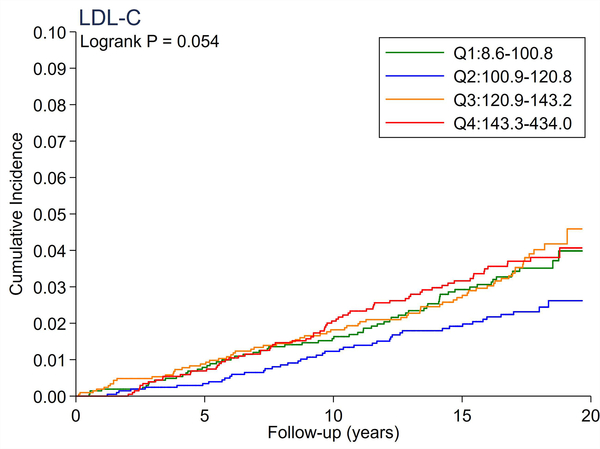

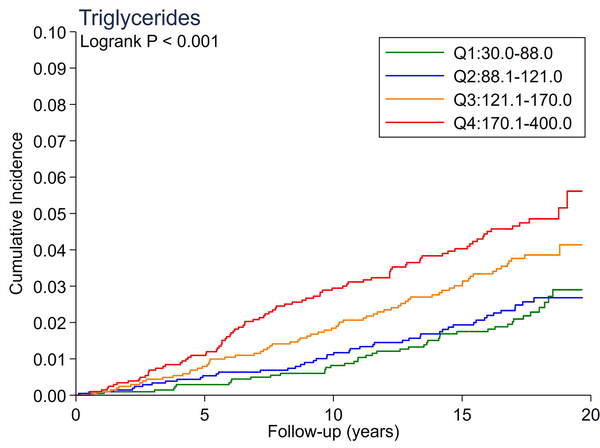

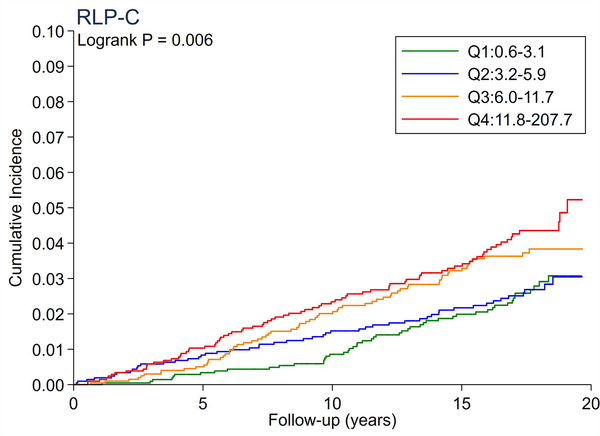

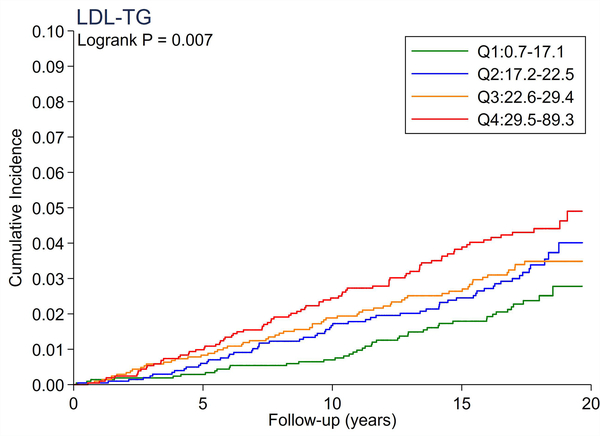

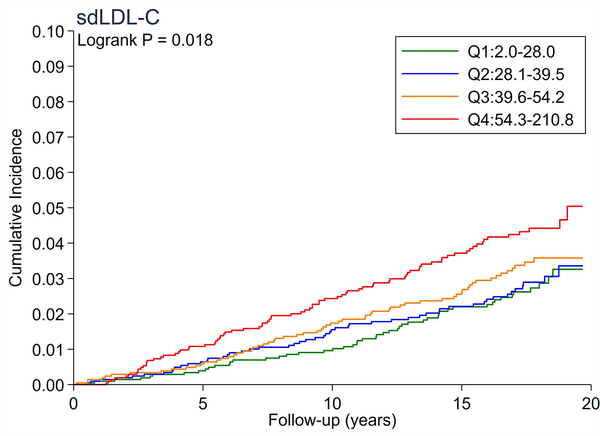

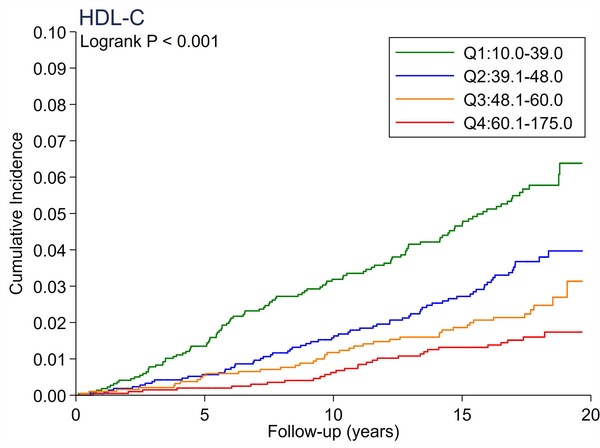

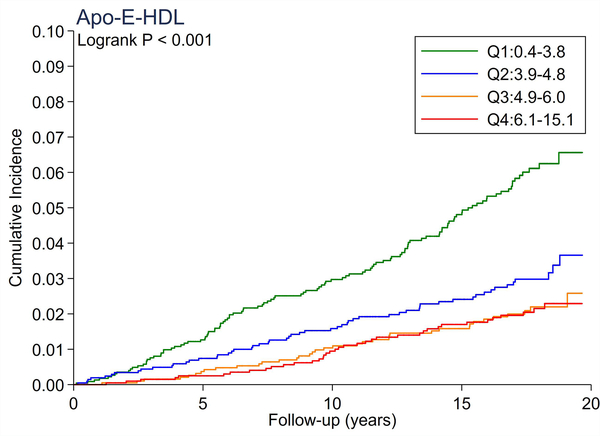

A total of 246 cases of incident PAD accrued over a median follow-up of 17.4 years. There were no significant differences in the cumulative incidence of PAD across quartiles of total cholesterol and LDL-C (Figure 1A and 1B). All triglyceride-related lipid measures generally showed a dose-response relationship (Figure 1C–1F), with triglycerides demonstrating the most evident separation across quartiles (Figure 1C). Of all lipid measures, HDL-C and Apo-E-HDL showed the largest risk gradient of PAD (i.e., 3–4-fold) across quartiles (Figure 1G and 1H).

Figure 1.

The cumulative incidence of PAD by Total Cholesterol (A), LDL-C (B), Triglycerides (C), RLP-C (D), LDL-TG (E), sdLDL-C (F), HDL-C (G), and Apo-E-HDL (H). The cumulative incidences of PAD were evaluated according to the quartiles of each lipid measure. Apo-E-HDL = apo E-containing high-density cholesterol; HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C = low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-TG = triglycerides in low-density lipoprotein; PAD = peripheral artery disease; RLP-C = remnant-like particle cholesterol; sdLDL-C = small dense LDL cholesterol.

Using Cox proportional hazards regression, we confirmed that total cholesterol and LDL-C were not significantly associated with incident PAD (Table 2). Per 1-SD increment, all triglyceride-related lipid measures except sdLDL-C demonstrated significant associations with incident PAD (e.g., hazard ratio [HR] 1.21 [1.08–1.36] for triglycerides). Among all lipid measures, the hazard ratio of PAD per 1-SD was highest for HDL-C (HR 1.39 [1.16–1.67]), followed by Apo-E-HDL (1.27 [1.07–1.51]). When we estimated the HR of PAD across quartiles of each lipid measure, we observed generally consistent results, with the highest (lowest for HDL-C and Apo-E-HDL) vs. referent quartile reaching statistical significance in triglycerides, RLP-C, LDL-TG, HDL-C, and Apo-E-HDL. The second highest quartile showed a significant association only in triglycerides. All associations between novel lipid measures and PAD became non-significant after further adjusting for HDL-C or triglycerides (Table 3).

Table 2:

Adjusted Hazard Ratio of Incident PAD by Quartile of Each Lipid Measure*

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | 1-SD† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Cholesterol | Range | 77.0–177.0 | 177.1–199.0 | 199.1–223.0 | 223.1–521.0 | |

| Ref | 1.20 (0.85–1.70) | 1.03 (0.71–1.50) | 1.30 (0.91–1.87) | 1.10 (0.97–1.25) | ||

| LDL-C | Range | 8.6–100.8 | 100.9–120.8 | 120.9–143.2 | 143.3–434.0 | |

| Ref | 0.69 (0.47–1.02) | 1.12 (0.79–1.59) | 1.14 (0.81–1.62) | 1.10 (0.97–1.25) | ||

| Triglycerides | Range | 30.0–88.0 | 88.1–121.0 | 121.1–170.0 | 170.1–400.0 | |

| Ref | 1.04 (0.68–1.58) | 1.58 (1.07–2.34) | 1.79 (1.21–2.65) | 1.21 (1.08–1.36) | ||

| RLP-C | Range | 0.6–3.1 | 3.2–5.9 | 6.0–11.7 | 11.8–207.7 | |

| Ref | 1.06 (0.71–1.58) | 1.44 (0.98–2.10) | 1.53 (1.05–2.23) | 1.18 (1.08–1.29) | ||

| LDL-TG | Range | 0.7–17.1 | 17.2–22.5 | 22.6–29.4 | 29.5–89.3 | |

| Ref | 1.27 (0.85–1.88) | 1.16 (0.78–1.72) | 1.55 (1.06–2.27) | 1.18 (1.05–1.33) | ||

| sdLDL-C | Range | 2.0–28.0 | 28.1–39.5 | 39.6–54.2 | 54.3–210.8 | |

| Ref | 0.97 (0.66–1.43) | 1.10 (0.75–1.61) | 1.36 (0.95–1.96) | 1.12 (0.99–1.27) | ||

| HDL-C | Range | 10.0–39.0 | 39.1–48.0 | 48.1–60.0 | 60.1–175.0 | |

| 2.00 (1.26–3.16) | 1.58 (0.99–2.50) | 1.18 (0.73–1.92) | Ref | 1.39 (1.16–1.67) | ||

| Apo-E-HDL | Range | 0.4–3.8 | 3.9–4.8 | 4.9–6.0 | 6.1–15.1 | |

| 1.71 (1.12–2.60) | 1.08 (0.70–1.66) | 0.82 (0.52–1.30) | Ref | 1.27 (1.07–1.51) |

Abbreviation: Apo-E-HDL = apo E-containing high-density cholesterol; HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C = low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-TG = triglycerides in low-density lipoprotein; PAD = peripheral artery disease; RLP-C = remnant-like particle cholesterol; sdLDL-C = small dense LDL cholesterol.

Model was adjusted for age, race, sex, BMI, smoking, alcohol use, hs-CRP, education level, systolic blood pressure, diabetes, prevalent coronary heart disease, prevalent stroke, antihypertensive drugs use, and lipid-lowering medication use.

Unit: mg/dL

HR for 1-SD decrement (HDL-C and Apo-E-HDL) or increment (other lipid measures).

Bold indicates statistical significance.

Table 3:

Adjusted Hazard Ratio of Incident PAD by Quartile of Novel Lipid Measures*

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | 1-SD† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RLP-C | Range | 0.6–3.1 | 3.2–5.9 | 6.0–11.7 | 11.8–207.7 | |

| All covariates + HDL-C | Ref | 0.98 (0.66–1.46) | 1.25 (0.85–1.86) | 1.23 (0.82–1.84) | 1.13 (1.02–1.25) | |

| All covariates + triglycerides | Ref | 0.97 (0.65–1.46) | 1.20 (0.79–1.81) | 1.01 (0.58–1.73) | 1.09 (0.93–1.28) | |

| LDL-TG | Range | 0.7–17.1 | 17.2–22.5 | 22.6–29.4 | 29.5–89.3 | |

| All covariates + HDL-C | Ref | 1.16 (0.78–1.73) | 1.00 (0.67–1.51) | 1.30 (0.87–1.93) | 1.13 (1.00–1.27) | |

| All covariates + triglycerides | Ref | 1.18 (0.79–1.75) | 1.00 (0.66–1.52) | 1.21 (0.79–1.86) | 1.09 (0.95–1.26) | |

| Apo-E-HDL | Range | 0.4–3.8 | 3.9–4.8 | 4.9–6.0 | 6.1–15.1 | |

| All covariates + HDL-C | 1.09 (0.61–1.94) | 0.77 (0.46–1.30) | 0.66 (0.40–1.09) | Ref | 1.00 (0.76–1.30) | |

| All covariates + triglycerides | 1.59 (1.04–2.43) | 1.01 (0.65–1.57) | 0.80 (0.50–1.26) | Ref | 1.23 (1.04–1.47) | |

| sdLDL-C | Range | 2.0–28.0 | 28.1–39.5 | 39.6–54.2 | 54.3–210.8 | |

| All covariates + HDL-C | Ref | 0.92 (0.62–1.36) | 0.98 (0.66–1.43) | 1.15 (0.79–1.68) | 1.07 (0.94–1.21) | |

| All covariates + triglycerides | Ref | 0.91 (0.61–1.35) | 0.94 (0.63–1.40) | 1.00 (0.64–1.55) | 0.99 (0.85–1.16) | |

Abbreviation: Apo-E-HDL = apo E-containing high-density cholesterol; LDL-TG = triglycerides in low-density lipoprotein; PAD = peripheral artery disease; RLP-C= remnant-like particle cholesterol; sdLDL-C = small dense LDL cholesterol.

Model was adjusted for age, race, sex, BMI, smoking, alcohol use, hs-CRP, education level, systolic blood pressure, diabetes, prevalent coronary heart disease, prevalent stroke, antihypertensive drugs use, and lipid-lowering medication use.

Unit: mg/dL.

HR for 1-SD decrement (Apo-E-HDL) or increment (other lipid measures).

Bold indicates statistical significance.

Supplemental Figure II displays the results for subgroup analysis by sex and race. A significantly stronger association in men than in women was seen in sdLDL-C, HDL-C, and Apo-E-HDL (e.g., HR 1.71 [1.32–2.21] vs. 1.12 [0.88–1.41], p-for-interaction = 0.008, respectively, for HDL-C). HDL-C and Apo-E-HDL also demonstrated significant interaction with race, with a stronger association in whites than in blacks (e.g., HR 1.63 [1.29–2.05] vs. 1.05 [0.78–1.43], p-for-interaction = 0.014, respectively, for HDL-C).

Association between Blood Lipid Measures and CHD

The total number of incident CHD cases was 774. After adjusting for all the covariates, 1-SD difference in all lipid measures except Apo-E-HDL was independently associated with a higher risk of incident CHD (Supplemental Table X). Unlike the associations with PAD, total cholesterol and LDL-C were both significantly associated with CHD (HR 1.20 [1.12–1.28] for total cholesterol and 1.20 [1.12–1.28] for LDL-C with 1-SD increment). Generally, similar results were seen when we modeled each lipid measure by quartiles.

Principal Component Analysis

We identified three components with eigenvalues > 1, which could simultaneously address 85% of variance among lipid measures (Supplemental Table XI). Component 1 was mainly loaded by triglyceride-related lipids and lipoproteins (triglycerides, RLP-C, LDL-TG, and sdLDL-C), Component 2 by HDL-related lipids (HDL-C and Apo-E-HDL), and Component 3 by LDL-C and RLP-C (Supplemental Table XII). In Cox models, Component 1 (1.19 [1.10–1.28]) and component 2 (0.88 [0.78–0.99) were independently associated with incident PAD (Table 4).

Table 4:

Adjusted Hazard Ratio of Incident PAD by Principal components

| Component 1 | Component 2 | Component 3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAD | # | 246 | 246 | 246 |

| 1.19 (1.10–1.28) | 0.88 (0.78–0.99) | 0.95 (0.84–1.07) |

Abbreviation: PAD = peripheral artery disease.

Model was adjusted for age, race, sex, BMI, smoking, alcohol use, hs-CRP, education level, systolic blood pressure, diabetes, prevalent coronary heart disease, prevalent stroke, antihypertensive drugs use, and lipid-lowering medication use.

Bold indicates statistical significance.

Sensitivity Analysis

Among 7,162 participants not taking lipid-lowering medications (198 incident PAD cases were noted), we generally observed similar results as our primary analysis (Supplemental Table XIII). A few exceptions were significant associations for sdLDL-C (1.19 [1.04–1.35]) and no significant associations for Apo-E-HDL.

Prediction of Incident PAD Risk

The base model (including age, sex, systolic blood pressure, smoking status, diabetes, and prevalent CHD) showed a high c-statistic of 0.818 (0.784–0.852) and 0.810 (0.785–0.834) for the 10-year and 20-year predicted risks of PAD, respectively. Triglycerides was the only lipid measure that statistically significantly improved c-statistic beyond established predictors in the base model for 10-year PAD risk (Δc = 0.006 [0.001–0.012]) (Table 5). As for categorical NRI, the lipid measures with exception of LDL-C and sdLDL-C, demonstrated significantly positive results for 20-year prediction, although none of them showed significantly positive NRI for the 10-year predictions. Although some comparisons demonstrated statistically significant Hosmer-Lemeshow χ2 tests, visually the calibration was generally good (Supplemental Figures III and IV).

Table 5:

Improvement in PAD Risk Reclassification and Discrimination with Addition of Lipid Measure to Base Model

| 10-year risk of PAD | C-statistic (95% CI) | Δc (95% CI) | NRI (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base+total cholesterol | 0.821 (0.787–0.854) | 0.003 (−0.001–0.006) | 0.007 (−0.019, 0.033) |

| Base+LDL-C | 0.821 (0.787–0.854) | 0.003 (−0.002–0.007) | −0.001 (−0.037, 0.036) |

| Base+triglycerides | 0.824 (0.791–0.858) | 0.006 (0.001–0.012) | 0.020 (−0.034, 0.074) |

| Base+RLP-C | 0.822 (0.788–0.856) | 0.004 (−0.002–0.010) | −0.000 (−0.052, 0.051) |

| Base+LDL-TG | 0.822 (0.788–0.856) | 0.004 (−0.002–0.010) | 0.029 (−0.018, 0.077) |

| Base+sdLDL-C | 0.820 (0.786–0.854) | 0.002 (−0.001–0.005) | 0.015 (−0.015, 0.045) |

| Base+HDL-C | 0.821 (0.785–0.856) | 0.003 (−0.008–0.013) | 0.036 (−0.018, 0.090) |

| Base+Apo-E-HDL | 0.816 (0.781–0.852) | −0.002 (−0.011–0.008) | 0.036 (−0.022, 0.094) |

| 20-year risk of PAD | |||

| Base+total cholesterol | 0.811 (0.786–0.835) | 0.001 (−0.002–0.004) | 0.022 (0.001, 0.043) |

| Base+LDL-C | 0.810 (0.786–0.835) | 0.001 (−0.003–0.004) | 0.013 (−0.014, 0.039) |

| Base+triglycerides | 0.812 (0.787–0.837) | 0.002 (−0.002–0.007) | 0.045 (0.010, 0.080) |

| Base+RLP-C | 0.812 (0.787–0.837) | 0.003 (−0.003–0.008) | 0.035 (0.005, 0.065) |

| Base+LDL-TG | 0.810 (0.785–0.835) | 0.001 (−0.004–0.005) | 0.044 (0.008, 0.081) |

| Base+sdLDL-C | 0.810 (0.785–0.835) | 0.000 (−0.002–0.002) | 0.017 (−0.005, 0.040) |

| Base+HDL-C | 0.807 (0.781–0.834) | −0.002 (−0.011–0.007) | 0.054 (0.013, 0.095) |

| Base+Apo-E-HDL | 0.805 (0.779–0.832) | −0.004 (−0.012–0.004) | 0.038 (0.002, 0.073) |

Abbreviation: Apo-E-HDL = apo E-containing high-density cholesterol; HDL-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C = low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-TG = triglycerides in low-density lipoprotein; RLP-C = remnant-like particle cholesterol; sdLDL-C = small dense LDL cholesterol; NRI = net reclassification improvement; IDI = integrated discrimination index

Base model adjusted for age, sex, systolic blood pressure, smoking status, diabetes, and prevalent CHD

Bold indicates statistical significance.

Discussion

In this community-based prospective cohort study with a median follow-up of 17 years, we observed that higher baseline levels of triglyceride-related blood lipids and lower levels of HDL-related lipids were independently and robustly associated with incident PAD. The principal component analysis supported this observation. We confirmed the well-established independent associations of total cholesterol and LDL-C with incident CHD, but their associations with PAD were not statistically significant. The associations of triglyceride-related lipids and HDL-related lipids were largely consistent by sex and race, although HDL-related lipids tended to be more strongly associated with PAD in men and whites compared to women and blacks. Of note, none of the novel lipid measures remained significant in the two models including either triglycerides or HDL-C in addition to potential confounders. Among all blood lipid parameters tested, only triglycerides significantly improved risk discrimination of PAD beyond established predictors.

The lack of association of total cholesterol and LDL-C with PAD may seem counterintuitive. Indeed, some studies reported their positive associations with PAD. For example, Joosten et al 9 observed that hypercholesterolemia was significantly associated with incident PAD in male healthcare professionals. Of note, hypercholesterolemia was less strongly associated with PAD than smoking, diabetes, and hypertension in that study. The factors behind the discrepancy between this previous report and our study are unclear but could reflect differences in study population, study design (e.g., hypercholesterolemia in that study was based on self-report while we explored blood lipid levels), and analytic approaches (e.g., our covariate adjustment was more extensive, including education and hs-CRP). Nonetheless, given the fact that LDL-C was significantly associated with CHD in our study, it seems reasonable to interpret that the contribution of LDL-C is smaller for PAD than CHD.

The stronger associations of triglyceride- and HDL-related lipid parameters with PAD than total cholesterol and LDL-C in our study are largely consistent with a recent report from the Women’s Health Study, an extension of a trial among predominantly non-Hispanic white female healthcare workers 31. However, there are several unique aspects of our study. First, our study is community-based and bi-racial, with broad generalizability. Second, incident PAD cases were identified through active surveillance of all hospitalizations, while the previous study was generally based on self-report of leg symptoms and hospitalizations. Third, we compared traditional and novel lipid measures in terms of their associations with PAD vs. CHD in a single study population. Finally, we formally assessed the risk prediction improvement of PAD with these lipid measures beyond established predictors.

The reasons behind different contributions of lipid measures to PAD and CHD in the present study are not fully clear. Of note, several studies26, 31 suggest differences in the pathogenesis of PAD and CHD. For example, differences in composition of atherosclerotic plaque and gene expression across different vascular beds have been reported.32, 33 Also, hemodynamic forces differ between peripheral arteries and coronary arteries,34 and medial artery calcification is common in lower extremity arteries but is not the coronary arteries.33 Nonetheless, additional research is needed on the pathogenesis of PAD and CHD, ideally in a single population.

The stronger associations of HDL-related lipids with PAD risk among whites and men compared to blacks and women deserve some discussion. We are not sure about potential mechanisms behind this observation, but it is well-known that both whites and men are known to have lower levels of HDL-C than their counterparts. Nonetheless, we need to carefully interpret our subgroups analysis since we conducted this analysis without a specific hypothesis. Thus, future studies are needed to confirm racial- and sex-difference in the association of HDL-related lipids with PAD risk.

Our study has several implications. First, different lipid profiles for PAD and CHD further highlight the different atherogenic mechanisms across vascular beds. Second, our results suggest triglyceride- and HDL-related lipids over LDL-C as therapeutic targets for preventing PAD. Although the FOURIER trial shows that medication PCSK9 inhibitor, evolocumab, significantly reduced the risk of adverse limb events, this trial is likely to explore different stages of disease process since it included patients with established PAD and defined limb events as acute limb ischemia, amputation, or urgent leg revascularization.35 Also, we need to acknowledge that several treatments increasing HDL-C levels did not decrease the risk of cardiovascular events thus far.36, 37 Regarding elevated triglycerides, the Reduction of Cardiovascular Events with Icosapent Ethyl–Intervention Trial showed that icosapent ethyl, reducing triglycerides, prevented major adverse cardiovascular events by ~25%.11 Other new therapies reducing triglycerides by targeting angiopoietin-like protein 3 and apolipoprotein C-III are also undergoing phase III trials.38 It would be of interest to see whether these medications can reduce the risk of ischemic leg outcomes. Third, in terms of risk prediction of PAD, given the incremental improvement in risk discrimination, the value of lipid parameters seems somewhat limited, but triglycerides is likely to be the most valuable one. Finally, none of the novel lipid measures clearly outperformed conventional lipid measures in terms of their associations with PAD risk.

Limitation

There are some limitations in our study. First, the ARIC study predominantly consists of white and black study participants, and thus, our findings may not be generalizable to other racial/ethnic groups. Second, our study was based on a single measurement of lipid parameters at baseline with a potential of misclassification and thus underestimation of true associations. Third, mild and asymptomatic PAD cases were likely missed since we relied on hospitalization records with PAD diagnosis or procedures as the outcome. Finally, as true in any observational studies, residual confounding may still exist despite our extensive adjustment for potential confounders.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our prospective study showed robust associations of triglyceride- and HDL-related blood lipids, but not LDL-C, with PAD, whereas LDL-C was independently associated with CHD, as anticipated. Among all lipid parameters tested, only triglycerides significantly improved PAD risk prediction beyond established predictors, albeit modestly. Our findings further highlight potential differences in the contributions of lipoprotein lipid families to the development of atherosclerosis across various vascular beds. They further suggest the importance of triglyceride- and HDL-related lipids for PAD development, with potential implications for preventive therapies and risk classification.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Among eight conventional and novel lipid measures tested in this study, higher levels of triglyceride-related lipids and lower levels of high-density lipoprotein-related lipids were particularly robustly associated with incident peripheral artery disease.

Total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol demonstrated stronger associations with coronary heart disease than peripheral artery disease.

None of the novel lipid measures outperformed conventional lipid measures in predicting peripheral artery disease risk.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions.

Sources of Funding

The ARIC study has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract nos. (HHSN268201700001I, HHSN268201700002I, HHSN268201700003I, HHSN268201700005I, HHSN268201700004I). Dr. Matsushita has been supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R21HL133694); and has received research funding and personal fees from Fukuda Denshi (outside of the work).

Abbreviations

- ARIC

Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities

- Apo-E-HDL

Apo-E containing high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- BMI

body mass index

- CHD

coronary heart disease

- HDL-C

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HR

hazard ratio

- LDL-C

low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDL-TG

low-density lipoprotein triglycerides

- PAD

peripheral artery disease

- RLP-C

remnant lipoprotein cholesterol

- sdLDL-C

small dense low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

Reference

- 1.Song P, Rudan D, Zhu Y, Fowkes FJI, Rahimi K, Fowkes FGR and Rudan I. Global, regional, and national prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2015: an updated systematic review and analysis. The Lancet Global Health. 2019;7:e1020–e1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sartipy F, Sigvant B, Lundin F and Wahlberg E. Ten Year Mortality in Different Peripheral Arterial Disease Stages: A Population Based Observational Study on Outcome. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2018;55:529–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McDermott MM. Lower extremity manifestations of peripheral artery disease: the pathophysiologic and functional implications of leg ischemia. Circ Res. 2015;116:1540–1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abu Dabrh AM, Steffen MW, Undavalli C, Asi N, Wang Z, Elamin MB, Conte MS and Murad MH. The natural history of untreated severe or critical limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2015;62:1642–1651.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norgren L, Hiatt WR, Dormandy JA, Nehler MR, Harris KA and Fowkes FGR. Inter-Society Consensus for the Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease (TASC II). J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:S5–S67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jang SY, Ju EY, Cho S-I, Lee SW and Kim D-K. Comparison of cardiovascular risk factors for peripheral artery disease and coronary artery disease in the korean population. Korean circulation journal. 2013;43:316–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu L, Mackay DF and Pell JP. Meta-analysis of the association between cigarette smoking and peripheral arterial disease. Heart. 2014;100:414–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tunstall-Pedoe H, Peters SAE, Woodward M, Struthers AD and Belch JJF. Twenty-Year Predictors of Peripheral Arterial Disease Compared With Coronary Heart Disease in the Scottish Heart Health Extended Cohort (SHHEC). J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e005967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joosten MM, Pai JK, Bertoia ML, Rimm EB, Spiegelman D, Mittleman MA and Mukamal KJ. Associations Between Conventional Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Risk of Peripheral Artery Disease in Men. JAMA. 2012;308:1660–1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nordestgaard BG and Varbo A. Triglycerides and cardiovascular disease. The Lancet. 2014;384:626–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, Brinton EA, Jacobson TA, Ketchum SB, Doyle RT, Juliano RA, Jiao L, Granowitz C, Tardif J-C and Ballantyne CM. Cardiovascular Risk Reduction with Icosapent Ethyl for Hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. 2018;380:11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toth PP. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins as a causal factor for cardiovascular disease. Vascular health and risk management. 2016;12:171–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: design and objectives. The ARIC investigators. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedewald WT, Levy RI and Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirao Y, Nakajima K, Machida T, Murakami M and Ito Y. Development of a Novel Homogeneous Assay for Remnant Lipoprotein Particle Cholesterol. The Journal of Applied Laboratory Medicine. 2018;3:26–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ito Y, Ohta M, Ikezaki H, Hirao Y, Machida A, Schaefer EJ and Furusyo N. Development and Population Results of a Fully Automated Homogeneous Assay for LDL Triglyceride. The Journal of Applied Laboratory Medicine. 2019;2:746–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albers JJ, Kennedy H and Marcovina SM. Evaluation of a new homogenous method for detection of small dense LDL cholesterol: Comparison with the LDL cholesterol profile obtained by density gradient ultracentrifugation. Clin Chim Acta. 2011;412:556–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takahashi Y, Ito Y, Wada N, Nagasaka A, Fujikawa M, Sakurai T, Shrestha R, Hui SP and Chiba H. Development of homogeneous assay for simultaneous measurement of apoE-deficient, apoE-containing, and total HDL-cholesterol. Clin Chim Acta. 2016;454:135–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohn JS, Marcoux C and Davignon J. Detection, quantification, and characterization of potentially atherogenic triglyceride-rich remnant lipoproteins. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:2474–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jialal I and Devaraj S. Remnant Lipoproteins: Measurement and Clinical Significance. Clin Chem. 2002;48:217–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saeed A, Feofanova EV, Yu B, Sun W, Virani SS, Nambi V, Coresh J, Guild CS, Boerwinkle E, Ballantyne CM and Hoogeveen RC. Remnant-Like Particle Cholesterol, Low-Density Lipoprotein Triglycerides, and Incident Cardiovascular Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:156–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.März W, Scharnagl H, Winkler K, Tiran A, Nauck M, Boehm BO and Winkelmann BR. Low-Density Lipoprotein Triglycerides Associated With Low-Grade Systemic Inflammation, Adhesion Molecules, and Angiographic Coronary Artery Disease. Circulation. 2004;110:3068–3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agarwala A, Sun W, Nambi V, Guild C, Coresh J, Ballantyne CM and Hoogeveen R. Abstract 12141: ApoE-HDL Cholesterol Predicts Incident Cardiovascular Events: Aric Study. Circulation. 2016;134:A12141–A12141. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Folsom AR, Lutsey PL, Astor BC and Cushman M. C-reactive protein and venous thromboembolism. A prospective investigation in the ARIC cohort. Thromb Haemost. 2009;102:615–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsushita K, Kwak L, Yang C, et al. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin and natriuretic peptide with risk of lower-extremity peripheral artery disease: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:2412–2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ding N, Sang Y, Chen J, Ballew SH, Kalbaugh CA, Salameh MJ, Blaha MJ, Allison M, Heiss G, Selvin E, Coresh J and Matsushita K. Cigarette Smoking, Smoking Cessation, and Long-Term Risk of 3 Major Atherosclerotic Diseases. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:498–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu Y, Ballew SH, Kwak L, Selvin E, Kalbaugh CA, Schrack JA, Matsushita K and Szklo M. Physical Activity and Subsequent Risk of Hospitalization With Peripheral Artery Disease and Critical Limb Ischemia in the ARIC Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e013534–e013534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.White AD, Folsom AR, Chambless LE, Sharret AR, Yang K, Conwill D, Higgins M, Williams OD, Tyroler HA and The AI. Community surveillance of coronary heart disease in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: Methods and initial two years’ experience. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:223–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murabito JM, D’Agostino RB, Silbershatz H and Wilson PWF. Intermittent Claudication. Circulation. 1997;96:44–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang C, Kwak L, Ballew SH, Jaar BG, Deal JA, Folsom AR, Heiss G, Sharrett AR, Selvin E, Sabanayagam C, Coresh J and Matsushita K. Retinal microvascular findings and risk of incident peripheral artery disease: An analysis from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Atherosclerosis. 2020;294:62–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aday AW, Lawler PR, Cook NR, Ridker PM, Mora S and Pradhan AD. Lipoprotein Particle Profiles, Standard Lipids, and Peripheral Artery Disease Incidence. Circulation. 2018;138:2330–2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dalager S, Paaske WP, Kristensen IB, Laurberg JM and Falk E. Artery-Related Differences in Atherosclerosis Expression. Stroke. 2007;38:2698–2705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steenman M, Espitia O, Maurel B, Guyomarch B, Heymann M-F, Pistorius M-A, Ory B, Heymann D, Houlgatte R, Gouëffic Y and Quillard T. Identification of genomic differences among peripheral arterial beds in atherosclerotic and healthy arteries. Sci Rep. 2018;8:3940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poredos P, Poredos P and Jezovnik MK. Structure of Atherosclerotic Plaques in Different Vascular Territories: Clinical Relevance. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2018;16:125–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bonaca MP, Nault P, Giugliano RP, et al. Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Lowering With Evolocumab and Outcomes in Patients With Peripheral Artery Disease: Insights From the FOURIER Trial (Further Cardiovascular Outcomes Research With PCSK9 Inhibition in Subjects With Elevated Risk). Circulation. 2018;137:338–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Abt M, et al. Effects of Dalcetrapib in Patients with a Recent Acute Coronary Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2089–2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jensen MK, Aroner SA, Mukamal KJ, Furtado JD, Post WS, Tsai MY, Tjønneland A, Polak JF, Rimm EB, Overvad K, McClelland RL and Sacks FM. High-Density Lipoprotein Subspecies Defined by Presence of Apolipoprotein C-III and Incident Coronary Heart Disease in Four Cohorts. Circulation. 2018;137:1364–1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olkkonen VM, Sinisalo J and Jauhiainen M. New medications targeting triglyceride-rich lipoproteins: Can inhibition of ANGPTL3 or apoC-III reduce the residual cardiovascular risk? Atherosclerosis. 2018;272:27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.