Abstract

Endemic human coronaviruses (hCoVs) are common causative agents of respiratory tract infections, affecting especially children. However, in the ongoing SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, children are the least affected age-group. The objective of this study was to investigate the magnitude of endemic hCoVs antibodies in Finnish children and adults, and pre-pandemic antibody cross-reactivity with SARS-CoV-2. Antibody levels against endemic hCoVs start to rise at a very early age, reaching to overall 100% seroprevalence. No difference in the antibody levels was detected for OC43 but the magnitude of 229E-specific antibodies was significantly higher in the sera of children. OC43 and 229E hCoV antibody levels of children correlated significantly with each other and with the level of cross-reactive SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, whereas these correlations completely lacked in adults. Although none of the sera showed SARS-CoV-2 neutralization, the higher overall hCoV cross-reactivity observed in children might, at least partially, contribute in controlling SARS-CoV-2 infection in this population.

Keywords: Coronavirus, 229E, OC43, SARS-CoV-2, Serology, Cross-reactivity

1. Introduction

Coronaviruses (CoVs) are a large family of enveloped, positive-strand RNA viruses, classified into four genera, alpha, beta, gamma and delta, based on their phylogenetic and serological relationship [1]. Human CoVs (hCoVs), belonging to alpha and beta genera, cause a variety of symptoms ranging from common cold to potentially fatal respiratory conditions such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) [2]. A novel, highly contagious betavirus strain, SARS-CoV-2, was identified as an aetiologic agent of CoV associated disease (COVID-19) outbreak in Wuhan, China, causing significant amount of severe pneumonia and mortality especially among the elderly [3]. SARS-CoV-2 is a close relative to highly pathogenic SARS-CoV [4] that caused lethal outbreak in 2003, and Middle-East respiratory syndrome (MERS) CoV, which emerged in 2012 and has since caused repeated zoonotic outbreaks in Arabian Peninsula [5]. Newly emerged SARS-CoV-2 spread rapidly all over the word and in March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 as a pandemic [6].

There are four circulating endemic hCoVs, 229E, NL43, OC43 and HKU1, the two former are classified to alpha-, and the two latter to beta-CoVs [2]. These low-pathogenic hCoVs are causative agents in approximately 5% of respiratory tract infections globally [7], affecting especially children under 10 years of age [[7], [8], [9], [10]]. Although endemic hCoVs are randomly detected in the nasal swabs and stools of hospitalized children, they are considered to play a marginal role in severe pediatric respiratory infections [11,12]. It is estimated that adults are reinfected by endemic hCoVs every 2–3 years and about half of these infections are asymptomatic [13]. Seroconversion against circulating hCoVs occurs on average before the age of 3.5 years [8] and antibody prevalence rises rapidly with age [[8], [9], [10]]. Antibody concentrations start declining soon after hCoV infection, lasting from 5 months to two years and reinfections even with homotypic strains are common [14].

RNA-genome of CoVs encodes four structural proteins: the nucleocapsid (NP), the spike (S), the envelope (E), and the membrane (M) proteins [15]. Abundantly expressed RNA binding NP, and the outermost trimeric capsid protein S, are highly immunogenic and thus are often utilized as antigens in serological assays [16]. Protection from hCoV infection and/or disease is correlated with the level of neutralizing antibodies targeted to S protein [14] consisting of two subunits, the S1 responsible for cell attachment through a receptor-binding domain (RBD) and the S2 subunit mediating cell entry [17]. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)-based surrogate neutralization (sNe) assay, utilizing antibody ability to block RBD binding to a recombinant human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2) receptor, has been developed for SARS-CoV-2 as an alternative to a pseudovirus and live virus -based neutralization assays, requiring biosafety level 2 and 3 facilities, respectively [18].

Severe manifest of COVID-19 and mortality seems to be strongly associated with a higher age [19]. Children under 10 years of age have a low risk to experience severe outcomes of the disease and represent only 1–5% of all diagnosed COVID-19 cases [20]. It is still not fully understood why young children, who are repeatedly infected with endemic non-pathogenic hCoVs, are the least affected population in COVID-19 pandemic. The objective of this study was to investigate the pre-pandemic antibody levels to hCoV OC43 and 229E in Finnish children and adults, and to determine their serological cross-reactivity to SARS-CoV-2 proteins.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Subjects

Acute stage sera were collected from 6 months to 10-year-old children admitted in hospital as outpatients or inpatients with acute gastroenteritis during an epidemiological study (EPI) conducted in Tampere University Hospital and Kuopio University Hospital from August 2006 to September 2011 [12,21,22]. A total of 24 serum samples from children negative for endemic hCoVs detected by RT-PCR from nasal swab and/or stool samples [21], were randomly selected in this study from the EPI study cohort. Children sera were divided in three age-groups, 6 m – 2y; 2y – 5y; 5y – 10y, each age group containing 8 sera. The study protocol and the consent forms had been approved by the ethics committee in the hospital districts and the patients or the legal guardians volunteered for the study after having given an informed consent. A total of 22 pre-pandemic individual serum or plasma samples were collected from 11 adult volunteers (laboratory personnel, age range 26–56 years) during 2012–2019, previously used to study norovirus serology by our laboratory [23,24]. Six adult volunteers gave 2–4 longitudinally well-spaced serum/plasma samples (median time between serum collection was 18 months). An informed consent was obtained from each donor prior sample collection and all procedures were conducted in accordance of the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Cultivation of hCoV 229E and OC43 in cell culture

Tissue culture (TC)-adapted hCoV OC43 (VR-1558) and 229E (VR740), obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA), were propagated in MRC-5 and HCT-8 cell lines according to the ATCC instructions. Briefly, virus infection was performed on 80–90% confluent, 18–48 h old cellular monolayer. Cells were incubated 4–5 days in cell culture media (MEM for MRC-5 and RPMI for HTC-8 cells) supplied with 2% fetal bovine serum, 1% natrium pyruvate and 1% l-glutamine (all from Sigma-Aldrich) until cytopathic effect was detected. The viral supernatants were collected by centrifugation (1000 ×g, 10 min) and stored at −80 °C for later use as antigens in ELISA assay.

2.3. Detection of hCoV-specific binding antibodies by ELISA

hCoV OC43 and 229E cell culture supernatants were diluted 1:200 in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and used to coat (50 μl/well) 96-well half-area polystyrene plates (Corning, New York, NY). Alternatively, the plates were coated with recombinant SARS-CoV-2 S (active trimer) protein (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), SARS-CoV-2 RBD (SanyoBiopharmaceuticals Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) or NP (SanyoBiopharmaceuticals Co., Ltd) at 1 μg/ml. The optimal concentration or dilution of the coating antigens was determined in preliminary assays, prior to serum samples testing. After washing the unbound antigen (3 × 125 μl/well 0.05% Tween in PBS), the plates were blocked with 5% milk in PBS. All antibodies or sera samples were diluted in 1% milk in PBS and the plates were washed six times between each incubation step. The serum samples diluted serially two-fold from 1:100 (OC43 and 229E virus-coated plates) or diluted 1:100 (SARS-CoV-2 protein coated plates) were added at 50 μl/well and incubated for one hour at +37 °C. Known positive and negative serum samples (1:100 dilution) were used as positive and negative controls on virus-coated plates. Human anti-RBD mAb (SanyoBiopharmaceuticals Co., Ltd) diluted 1:1000 was used as a positive control on S and RBD coated plates. Horseradish-peroxidase (HRP) conjugated goat-anti human IgG (Novex, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) diluted 1:6000 was subsequently incubated on plates for 1 h at +37 °C. Substrate (Sigma FAST OPD, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was added (50 μl/well) and the color reaction was let to develop for 30 min in dark. Thereafter, the reaction was stopped with 2 M H2SO4 (25 μl/well) and the optical density (OD) was measured at 490 nm (Victor2 PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). The background signal from the blank wells (sample buffer only) was subtracted from all the OD readings on a plate. A sample was considered positive if the net OD value was above the cut-off OD calculated for each antigen as mean OD + 3 × SD of three negative sera and at least 0.1 OD. End-point antibody titers were defined as the reciprocal of the highest serum dilution giving an OD above the cut-off OD, determined for each dilution separately. If the starting dilution resulted in an OD-value below the set cut-off, the sample was given an arbitrary value half of the starting dilution for statistical purposes. A starting dilution 1:100 was considered as the limit of detection determined in preliminary optimization assays.

2.4. Surrogate neutralization (sNe) assay

The assay based on antibody-mediated blockage of CoV S or RBD binding to recombinant ACE-2, has been developed to measure neutralizing antibodies against SARS-COV-2 [18]. Ninety-six well plates (Corning) were coated overnight with human ACE-2 (hACE-2, aa18–740) Fc chimera recombinant protein (1 μg/ml in PBS, Invitrogen) and the plates were blocked with 5% milk in PBS for one hour at RT. The human sera at 1:10 or the positive control at 10 μg/ml (anti-RBD mAb, SanyoBiopharmaceuticals Co., Ltd) were preincubated with 0.5 μg/ml of S (R&D Systems) or 0.2 μg/ml of RBD (SanyoBiopharmaceuticals Co., Ltd) for one hour at +37 °C and subsequently the mixtures were added to ACE-2 coated plates (50 μl/well). Maximum binding control (S or RBD without serum) and blank (sample dilution buffer only) were also added and the plates were incubated 1.5 h at RT. The ACE-2 bound S or RBD were detected using 1:1000 diluted rabbit anti-S IgG (Invitrogen) and subsequently 1:10000 diluted anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (Abcam) that were incubated for 1 h at RT. The assay buffers, washing cycles and plate development were done following the same procedures as described for ELISA in Section 2.3. Binding inhibition percent (%) for each sample was calculated as 100% - (OD of ACE-2 binding in the presence of serum /OD of ACE-2 maximum binding × 100%).

2.5. Statistical analyses

Mann–Whitney U test and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to compare differences in the non-parametric observations (IgG titers) between two or more groups. Student's t-test or one-way ANOVA was used to assess the inter-group differences in the parametric observations (OD-values) between two or more groups. Pearson's chi-square test was performed to examine the differences in the antibody prevalence. Spearman rank correlation coefficient was used to assess degree of correlation between antibody levels. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05 and all hypothesis testing was two-tailed. Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism (San Diego, CA) version 8.3.0.

3. Results

3.1. Pre-existing immunity to endemic hCoVs in children and adults

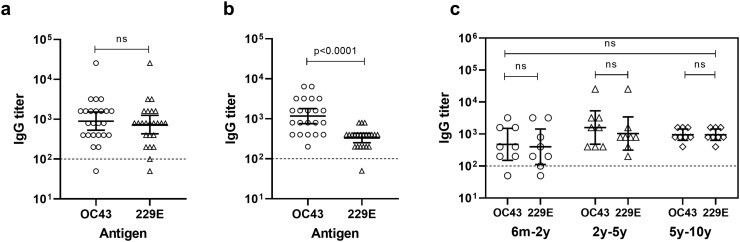

Twenty-four sera of children and 22 sera of adults were assayed in OC43 and 229E CoV -specific ELISAs to evaluate the seroprevalence and the level of pre-existing antibodies to endemic hCoVs. Overall, 96% (23/24) of children and 100% (22/22) of adult sera had antibodies to at least one of the hCoVs, indicating high overall seroprevalence to endemic hCoVs. As shown in Fig. 1 , children had equally high levels (p = 0.521) of serum IgG antibodies against OC43 (GMT = 898, 95% CI 533–1514) and 229E (GMT 734, 95% CI 430–1252) (Fig. 1a). In adults, the magnitude of OC43 antibodies (GMT = 1168, 95% CI 758–1798) was significantly (p < 0.0001) higher compared to 229E-specific antibodies (GMT = 331, 95% CI 252–434, Fig. 1b). Moreover, when virus-specific antibody levels were compared between children and adults, no difference was detected for OC43 (p = 0.406) but children had significantly higher level of 229E-specific antibodies (p = 0.003, data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Serum IgG responses against endemic OC43 and 229E human coronaviruses (hCoVs) in Finnish children and adults. Serially diluted sera of six months to 10 years old children (a) and adult volunteers (b) were tested against OC43 and 229E hCoV in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Level of virus-specific IgG in children sera stratified according to different age groups is shown in (c). Shown are the reciprocals of individual virus-specific end-point titers and the geometric mean titers (horizontal full lines) with 95% confidence intervals (error bars). The horizontal dashed line represents the limit of detection. Statistical significance was determined by Mann–Whitney U test and Kruskal-Wallis tests and a p-value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. ns, non-significant p-value.

To further evaluate hCoV-specific antibody generation in childhood, the antibody levels were studied in different age-groups (6 m – 2y; 2y – 5y; 5y – 10y, each age group containing 8 sera) (Fig. 1c). OC43- and 229E-specific IgG levels increased with age, being the lowest among 6 months – 2 years old children (GMT 476, 95% CI 151–1500, for OC43 and GMT 400, 95% CI 112–1435, for 229E), increasing to the highest level in 2–5 years age-group (GMT 1600, 95% CI 482–5310, for OC43 and GMT 1037, 95% CI 313–3435, for 229E) and settling to GMT 951 (95% CI 632–1433) for both viruses after the age of 5 years. However, the differences in the antibody levels across the age-groups or between OC43 and 229E were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Our data showed early seroconversion as 96% of 6 months to 2-year-old children were already positive to endemic hCoVs and all children over the age of 2 years were positive to both OC43 and 229E viruses.

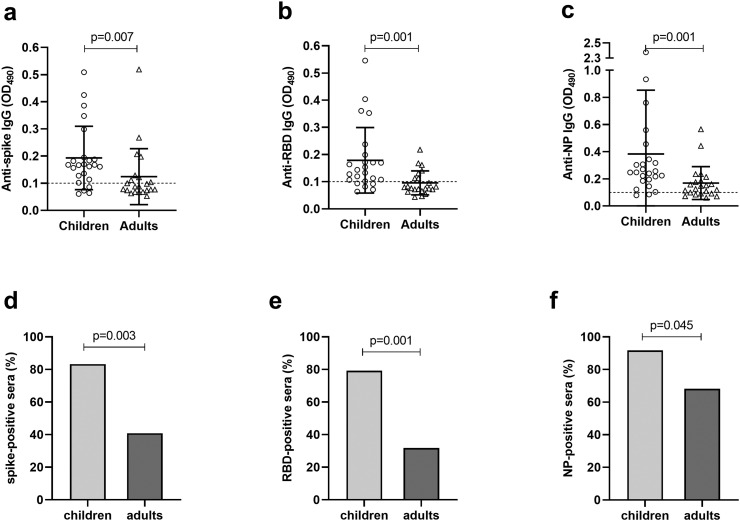

3.2. Cross-reactivity of endemic hCoV-specific antibodies to SARS-CoV-2

To investigate the serological cross-reactivity of pre-existing hCoV antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, all serum/plasma samples were assayed against SARS-CoV-2 S, RBD and NP proteins in ELISAs (Fig. 2 ). Overall, the levels of SARS-CoV-2 binding antibodies were low, but there were considerable differences in the magnitude and the prevalence of cross-reactive antibodies between children and adults. Children had significantly (p = 0.001–0.007) higher levels of cross-reactive antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 S (mean OD 0.179, Fig. 2a), RBD (mean OD 0.193, Fig. 2b) and NP (mean OD 0.383, Fig. 2c) in comparison to adults (mean OD 0.124 for S, 0.096 for RBD and 0.169 for NP, respectively). Consistent with the antibody levels, the seroprevalences against SARS-CoV-2 S (Fig. 2d), RBD (Fig. 2e) and NP (Fig. 2f) were significantly (p = 0.001–0.045) higher among children than adults. Of the three SARS-CoV-2 proteins tested, the highest prevalence of cross-reactive antibodies was observed against NP regardless of age. Furthermore, when children and adult data were combined as a single dataset, the highest magnitude of cross-reactive antibodies was targeted to NP (p = 0.007) over S and RBD (data not shown). The positive controls bound the coated SARS-CoV-2 proteins with high intensity in each assay (OD > 2.6, data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Cross-reactivity of pre-pandemic sera to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (S), receptor-binding domain (RBD) and nucleoprotein (NP). The sera of children and adult donors were tested against SARS-CoV-2 derived proteins in an ELISA and the individual IgG levels against S (a), RBD (b) and NP (c) are presented by optical density values (OD). The horizontal full lines illustrate the mean OD values with standard deviations (SD) of the mean (error bars). The dashed horizontal line represents the cut-off OD for the assay. The lower panels illustrate the prevalence (%) of spike (d), RBD (e) and NP (f) positive serum samples within children and adult groups. Statistical significance was determined by Pearson's chi-square test and a p-value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

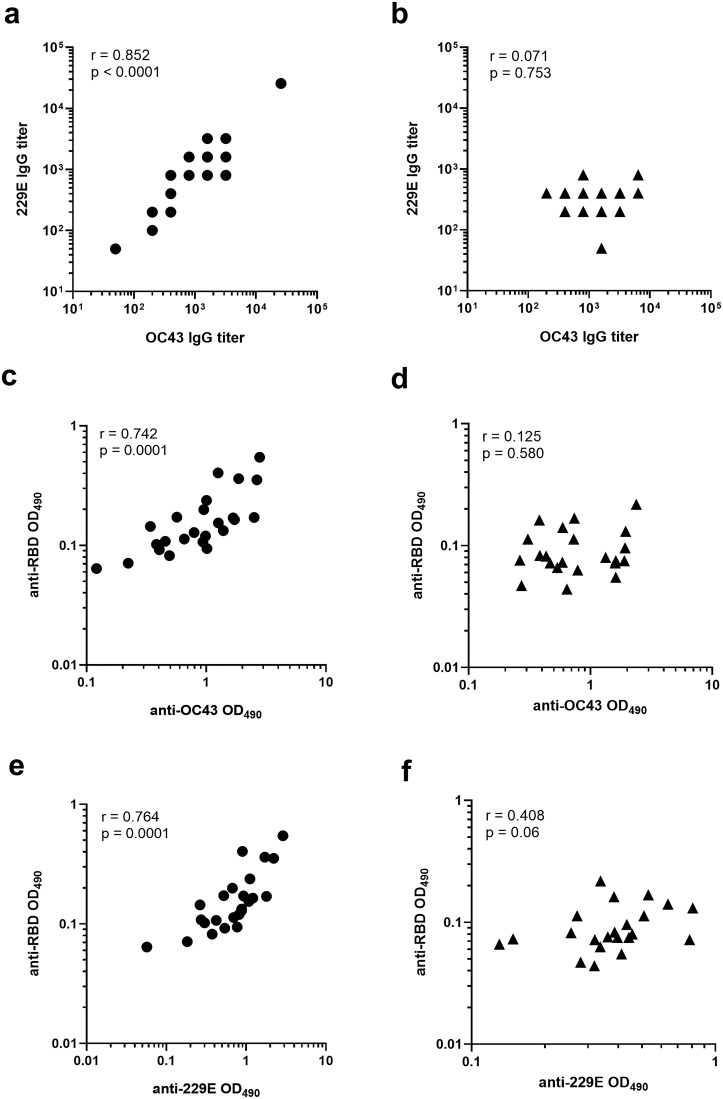

3.3. Correlation of pre-existing hCoV antibodies in children and adults

To evaluate the cross-reactive nature of pre-existing OC43 and 229E antibodies reciprocally or against SARS-CoV-2 proteins, the virus specific titers (Fig. 3a–b) or OD values (Fig. 3c–f) were subjected to Spearman correlation analysis. There were remarkable differences observed in the antibody correlations between children and adults. A strong positive correlation between OC43 and 229E antibody levels was detected in the sera of children (r = 0.852, p < 0.0001, Fig. 3a) while this correlation completely lacked in the sera of adults (r = 0.071, p = 0.753, Fig. 3b). Next, we investigated whether the pre-existing antibodies specific to OC43 and 229E correlate with the level of cross-reactive antibodies binding to SARS-2-CoV proteins. The levels of OC43 (Fig. 3c) and 229E (Fig. 3e) antibodies in the sera of children strongly and positively correlated (r = 0.742 and 0.764, p = 0.0001) with the level of cross-reactive SARS-CoV-2 RBD antibodies, whereas no significant correlation (r = 0.125 and 0.408, p > 0.05) was detected in the adult group (Fig. 3d and f). In children, OC43 and 229E antibody levels correlated positively also with anti-S (r = 0.693 and 0.725, p ≤ 0.0002) and anti-NP antibodies (r = 0.524 and 0.646, p ≤ 0.0085, data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Correlation of hCoV-specific serum IgG levels. The sera of children and adult donors were tested against endemic OC43 and 229E virus cultures and SARS-CoV-2 derived receptor binding domain (RBD) in an ELISA. Correlation was determined separately for children (left panels) and adults (right panels) groups between the IgG levels to OC43 and 229E (a and b), OC43 and RBD (c and d) and 229E and RBD (e and f). Shown are the individual end-point titers (a - b) or optical density (OD) values of sera diluted 1:100 (c - f). Spearman correlation coefficients (r) and associated p-values are shown in each plot. A p-value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

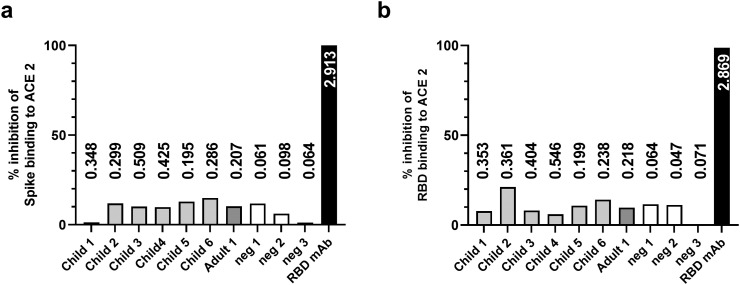

3.4. SARS-CoV-2 spike and RBD neutralization antibodies

sNe assay utilizing the ability of antibodies to block the binding of SARS-CoV-2 S or RBD proteins to immobilized ACE2, was used to assess the neutralization potency of the SARS-CoV-2 cross-reactive binding antibodies. The sera having an OD > 0.195 in a SARS-CoV-2 S- and/or RBD-specific ELISAs were selected to be tested for neutralization potency and three negative sera (OD < 0.1) were added as negative controls. As a result, none of the sera inhibited the binding of active trimeric S (Fig. 4a) or RBD (Fig. 4b) to hACE2, indicating the lack of SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing potential of the cross-reactive antibodies. On the contrary, SARS-CoV-2 RBD-specific mAb, used as positive control, completely blocked the binding of both proteins (Fig. 4a and b) confirming the functionality of the assay.

Fig. 4.

SARS-CoV-2 neutralization potency of the pre-pandemic hCoV antibodies. Individual sera (n = 10) positive (grey columns) or negative (white columns) for SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain (RBD) and/or spike-specific antibodies were used to block spike (a) or RBD (b) proteins binding to immobilized human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2) in a surrogate neutralization assay. RBD-specific monoclonal antibody (mAb) was used as positive blocking control (black columns). The columns represent the binding inhibition percent (%) for each sample was calculated as 100% - (optical density [OD] of ACE-2 binding in the presence of serum/OD of ACE-2 maximum binding × 100%). The numerical values above/inside columns illustrate the OD-values obtained from spike (a) or RBD (b) -specific IgG ELISAs.

4. Discussion

A high overall seroprevalence (nearly 100%) to endemic hCoVs detected in the present study corroborate earlier findings by others [[8], [9], [10],25]. We showed that the levels of hCoV-specific antibodies start to rise at an early age and all children over two years of age were seropositive to both OC43 and 229E viruses. The seroprevalence rate is in line, but somewhat higher, in comparison to the previous age-stratified studies [8,9], which reported the 229E seropositivity rate of ~45% in children 6 months to 2 years of age, rising to 60–90% after the age of 5 years. In the referred studies [8,9], the serum samples were analyzed against hCoV derived purified proteins whereas in the present study, OC43 and 229E virus cultures were utilized, which most likely increased the possibility to detect a wide range of homologous and cross-reactive hCoV antibodies. In addition, a limitation of our study was the relatively small sample size, possibly skewing the results. Serological cross-reactivity between hCoVs seems to exist more within than across genera, and previous studies have observed only minimal serological reactivity between endemic alpha- and beta-hCoVs [26,27]. On amino acid level, the sequence identity of NP and S proteins between endemic 229E and OC43 hCoVs, belonging in different genera, is around 30% (Clustal 2.1 pairwise sequence comparison, data not shown). SARS-CoV-2 identity rate within S and NP proteins is quite similar with 229E hCoVs (28.5–32.5%) and OC34 (30.5–34.8%), but when observing putative epitopes for B cells within S protein, the sequence identity rate rises to 37% with 229E and 44% with OC43 [28], suggesting higher antibody cross-reactivity with phylogenetically more related OC43.

We observed many striking differences in the pre-existing hCoV antibody responses between children and adults. The prevalence and the magnitude of OC43-specific antibodies were at the same level between children and adults, while 229E antibodies were significantly more prevalent and robust in children. Similar trend was also found by Shao et al. [9], who detected a sharp drop of 229E seropositive individuals after the age of 10 years. Another study discussed that OC43 has a greater clinical impact over 229E in adult population [29]. The low symptomatic 229E incidence among adults possibly reflected to the low-level 229E binding antibodies observed in adults also in the current study. The level of OC43 and 229E-specific antibodies in the sera of children strongly correlated not only with each other but also with the level of antibodies cross-reactive to SARS-CoV-2 proteins. The lack of correlation between different hCoV antibody levels observed in adult volunteers indicates that there might be a difference in the quality of the pre-existing pool of hCoV antibodies between adults and children. This difference may account for the better protection to SARS-CoV-2 infection seen in children compared to adults [20]. It is also possible that memory T cell responses to endemic hCoVs control the circulating hCoV infections in adults, whereas in children, the immune response might be more antibody dependent.

Recent studies have demonstrated the cross-reactivity of the endemic hCoVs induced pre-existing humoral and cellular immune responses with SARS-CoV-2 [[30], [31], [32]], but at what extent these responses influence the course of the infection or the severity of the disease, is not fully understood. We found significantly better SARS-CoV-2 cross-reactivity in the sera of children, with high endemic hCoV burden [7]. Interestingly, Tso et al. [30] found a correlation between pre-pandemic sera SARS-CoV-2 cross-recognition and low incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in sub-Saharan Africa, where the incidence of endemic hCoVs is high. It has been shown that SARS-CoV-2 has serological cross-reactivity at least with endemic beta-CoVs, OC43 and HKU1 [31]. Surprisingly, the comparable level of OC43-specific antibodies in children and adults we detected, did not result in comparable immunoreactivity to SARS-CoV-2 proteins, suggesting that the cross-reactivity is not solely dependent on the presence of OC43-reactive antibodies. Local, mild or asymptomatic endemic hCoV infections, manifesting typically in adults, tend to induce weak and rapidly waning humoral responses [33]. Children on the other hand, suffer more from endemic hCoV caused illness and hypothetically each new infection generates a wider pool of antibodies with higher affinity and thus better cross-reactivity to heterotypic strains [28,34] which might contribute, at least partially, to the lower incidence of severe SARS-CoV-2 infections observed in children [19,20]. Furthermore, the repeated infections throughout childhood shape the adaptive responses and when reaching to adulthood, a phenomenon called “original antigenic sin” [35] might skew the antibody responses and even cause immunopathogenesis through antibody-dependent enhancement as a response to highly-pathogenic hCoVs, such as SARS-CoV-2 [36].

The highest serological cross-reactivity of the pre-pandemic sera, was detected against SARS-CoV-2 NP, which was expected, as NP is the most conserved structural protein of CoVs [37]. The sera with the highest amount of SARS-CoV-2 S or RBD reactive antibodies were used subsequently in a sNe assay to investigate their neutralization potency. As expected, low magnitude SARS-CoV-2-specific cross-reactive antibodies were not able to block the binding of S or RBD to immobilized ACE2, which corroborates the results by others [38]. Based solely on the results from the sNe assay, it seems that the pre-existing antibodies generated to endemic hCoVs do not provide protection to SARS-CoV-2 through cross-neutralization. However, several other factors than the neutralizing antibodies, such as differences in the innate and adaptive immunity between children and adults, might contribute to protection from severe COVID-19 in children [39].

Although children have better protection to CoV-2 infection than adults, the mechanisms of the protection are not completely elucidated. Our study supports previous research [40] showing that children and adults have different preexisting antibody reactivity to SARS-CoV-2, resulting from the past infections with endemic hCoV. Vaccines currently used to immunize the adult human population, are the only effective measure so far to stop the COVID-19 pandemic [41]. It is possible that young children, due to the better preexisting immunity, might require less vaccine antigen in the vaccine formulation and/or fewer immunizations.

5. Conclusions

This study adds a general understanding to the humoral immune responses against endemic hCoVs, and pre-pandemic sera cross-reactivity to SARS-CoV-2, in different age-groups. The serological results obtained here indicate that children are exposed to circulating hCoVs at an early age and have higher cross-reactivity to SARS-CoV-2 than adults. Although the observations in this study do not give a direct answer to why children acquire clinically less severe COVID-19 than adults, the results suggest that higher serological cross-reactivity against SARS-CoV-2 could account for better protection from infection and severe disease.

Funding

Kirsi Tamminen received funding from Tampere Immunoexellence project under Profi4 program of Academy of Finland.

Declaration of competing interest

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The personnel of Vaccine Research Center, especially Eeva Jokela, are thanked for their valuable technical assistance during the study. We are grateful to Drs. Timo Vesikari, Sirpa Räsänen, Minna Paloniemi and Suvi Heinimäki for coordinating the epidemiological studies. We also thank the personnel of Tampere University Hospital and Kuopio University Hospital for collecting the serum samples, especially study nurse Marjo Salonen, for organizing serum collection. Finally, we would also like to thank the subjects and volunteers participating in the studies.

References

- 1.Cui J., Li F., Shi Z.L. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019;17(3):181–192. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li S.W., Lin C.W. Human coronaviruses: clinical features and phylogenetic analysis. Biomedicine (Taipei) 2013;3(1):43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.biomed.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Q., et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(13):1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drosten C., et al. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348(20):1967–1976. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Group, F.-O.-W.M.T.W MERS: Progress on the global response, remaining challenges and the way forward. Antivir. Res. 2018;159:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2018.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cucinotta D., Vanelli M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(1):157–160. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park S., et al. Global seasonality of human coronaviruses: a systematic review. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2020;7(11) doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa443. p. ofaa443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dijkman R., et al. Human coronavirus NL63 and 229E seroconversion in children. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008;46(7):2368–2373. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00533-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shao X., et al. Seroepidemiology of group I human coronaviruses in children. J. Clin. Virol. 2007;40(3):207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou W., et al. First infection by all four non-severe acute respiratory syndrome human coronaviruses takes place during childhood. BMC Infect. Dis. 2013;13:433. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Talbot H.K., et al. Coronavirus infection and hospitalizations for acute respiratory illness in young children. J. Med. Virol. 2009;81(5):853–856. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paloniemi M., Lappalainen S., Vesikari T. Commonly circulating human coronaviruses do not have a significant role in the etiology of gastrointestinal infections in hospitalized children. J. Clin. Virol. 2015;62:114–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2014.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Callow K.A., et al. The time course of the immune response to experimental coronavirus infection of man. Epidemiol. Infect. 1990;105(2):435–446. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800048019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang A.T., et al. A systematic review of antibody mediated immunity to coronaviruses: antibody kinetics, correlates of protection, and association of antibody responses with severity of disease. Nature Communications. 2020;11:4704. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18450-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masters P.S. The molecular biology of coronaviruses. Adv. Virus Res. 2006;66:193–292. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(06)66005-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyer B., Drosten C., Muller M.A. Serological assays for emerging coronaviruses: challenges and pitfalls. Virus Res. 2014;194:175–183. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li F. Structure, function, and evolution of coronavirus spike proteins. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2016;3(1):237–261. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-110615-042301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan C.W., et al. A SARS-CoV-2 surrogate virus neutralization test based on antibody-mediated blockage of ACE2-spike protein-protein interaction. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020;38(9):1073–1078. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0631-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Driscoll M., et al. Age-specific mortality and immunity patterns of SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2021;590(7844):140–145. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2918-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ludvigsson J.F. Systematic review of COVID-19 in children shows milder cases and a better prognosis than adults. Acta Paediatr. 2020;109(6):1088–1095. doi: 10.1111/apa.15270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Risku M., et al. Detection of human coronaviruses in children with acute gastroenteritis. J. Clin. Virol. 2010;48(1):27–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rasanen S., et al. Noroviruses in children seen in a hospital for acute gastroenteritis in Finland. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2011;170(11):1413. doi: 10.1007/s00431-011-1443-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malm M., et al. Norovirus-specific memory T cell responses in adult human donors. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:1570. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tamminen K., et al. Norovirus-specific mucosal antibodies correlate to systemic antibodies and block norovirus virus-like particles binding to histo-blood group antigens. Clin. Immunol. 2018;197:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2018.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Severance E.G., et al. Development of a nucleocapsid-based human coronavirus immunoassay and estimates of individuals exposed to coronavirus in a U.S. metropolitan population. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2008;15(12):1805–1810. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00124-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macnaughton M.R., Madge M.H., Reed S.E. Two antigenic groups of human coronaviruses detected by using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Infect. Immun. 1981;33(3):734–737. doi: 10.1128/iai.33.3.734-737.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trivedi S.U., et al. Development and evaluation of a multiplexed immunoassay for simultaneous detection of serum IgG antibodies to six human coronaviruses. Sci. Rep. 2019;9(1):1390. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-37747-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piccaluga P.P., et al. Cross-immunization against respiratory coronaviruses may protect children from SARS-CoV2: more than a simple hypothesis? Front. Pediatr. 2020;8:595539. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.595539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walsh E.E., Shin J.H., Falsey A.R. Clinical impact of human coronaviruses 229E and OC43 infection in diverse adult populations. J. Infect. Dis. 2013;208(10):1634–1642. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tso F.Y., et al. High prevalence of pre-existing serological cross-reactivity against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) in sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021;102:577–583. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.10.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hicks J., et al. Serologic cross-reactivity of SARS-CoV-2 with endemic and seasonal Betacoronaviruses. Journal of Clinical Immunology. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10875-021-00997-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grifoni A., et al. Targets of T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus in humans with COVID-19 disease and unexposed individuals. Cell. 2020;181(7):1489–1501. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.015. (e15) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kraaijeveld C.A., Reed S.E., Macnaughton M.R. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detection of antibody in volunteers experimentally infected with human coronavirus strain 229 E. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1980;12(4):493–497. doi: 10.1128/jcm.12.4.493-497.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doria-Rose N.A., Joyce M.G. Strategies to guide the antibody affinity maturation process. Curr. Opinion Virol. 2015;11:137. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas F., Jr. On the doctrine of original antigenic sin. 1960;104(6):572. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fierz W., Walz B. Antibody dependent enhancement due to original antigenic sin and the development of SARS. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:1120. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang J., et al. The structure analysis and antigenicity study of the N protein of SARS-CoV. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2003;1(2):145–154. doi: 10.1016/S1672-0229(03)01018-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poston D., et al. Absence of SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing activity in pre-pandemic sera from individuals with recent seasonal coronavirus infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zimmermann P., Curtis N. Why is COVID-19 less severe in children? A review of the proposed mechanisms underlying the age-related difference in severity of SARS-CoV-2 infections. Arch. Dis. Child. 2021;106:429–439. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-320338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ng K.W., et al. Preexisting and de novo humoral immunity to SARS-CoV-2 in humans. Science. 2020;370(6522):1339–1343. doi: 10.1126/science.abe1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koirala A., et al. Vaccines for COVID-19: the current state of play. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2020;35:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2020.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]