Abstract

The chemistry of metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), a new class of emerging crystalline porous solids with three-dimensional (3D) networks composed of metals and multidentate organic molecules, was introduced by using three differently-shaped crystals. We reported new and mild MOF synthesis methods that are simple and devised to be performed in high school or primarily undergraduate school settings. MOF applications were demonstrated by use of our synthesized MOFs in the capture of iodine as a potentially hazardous molecule from solution and as a drug delivery system. These applications can be visually confirmed in minutes. Students can gain knowledge on advanced topics, such as drug delivery systems, through these easy-to-prepare MOFs. Furthermore, students can gain an understanding of powder X-ray analysis and ultraviolet-visible near-infrared spectroscopy. This laboratory experience is practical, including synthesis and application of MOFs. The entire experiment has also been recorded as an educational video posted on YouTube as a free public medium for students to watch and learn. In this article we first report the steps we took to synthesize and analyze the MOFs, followed by a description of a simple demonstration that we verified to effectively exhibit adsorption by MOFs. We conclude with a description of how the laboratory activity and demonstration was implemented in an undergraduate chemistry laboratory.

Keywords: High School / Introductory Chemistry, First-Year Undergraduate / General, Second-Year Undergraduate, Upper-Division Undergraduate, Inorganic Chemistry, Hands-On Learning / Manipulatives, Applications of Chemistry, Crystals / Crystallography, Nanotechnology, Separation Science

Graphical Abstract:

Introduction

Nanoporous materials, such as metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), have novel properties that are becoming of increasing scientific and technological importance as we continue to discover new nanoporous materials with new applications.1 MOFs possess a wide variety of applications due to their large internal surface area, porous nature, and strong bonds between metal and linkers.2 These characteristics allow them to be suitable materials for applications such as catalysis, gas storage, drug delivery, gas vapor separation, luminescence, lithium-ion batteries, water treatment, and carbon dioxide capture, as well as photo and electrocatalysis.1, 3 MOFs ability to encapsulate drugs and other substrates makes them novel new drug delivery systems and pollution control agents.4–7 With MOFs’ increasing importance in a variety of chemical fields, it is important that we educate younger generations, specifically high school and undergraduate students, in the function and preparation of MOFs. The synthesis of these compounds typically requires access to university- level laboratory resources, without which these compounds can be very difficult to prepare. This project aims to show that the synthesis and testing process of MOFs can be simplified to the point that high school and undergraduate students can do it without the use of highly specific equipment, therefore enriching their educational experience as they interact with cutting edge chemistry.

Educational approaches using MOF have been reported. Smith et al. reported gas adsorption using CD-MOF (cyclodextrin-metal-organic framework), and Jones et al. reported removal of methylene blue using CD-MOF.8, 9 Rood et al. approaches α-Mg3(O2CH)6 synthesis and NMR understanding, and Wriedt et al. introduces PCN-200 (porphyrinic metal-organic framework) synthesis and gas adsorption.10, 11 Sumida, K and Arnold, J also reported preparation and characterization of MOFs for undergraduate students.12

The purpose of our pedagogical approach using MOFs is to introduce a new synthetic approach to MOF tailored to high school facilities and various applied experiments using three types of MOF. Using three easily synthesized MOFs, students can learn the difference in adsorption capacity depending on the kinds of MOF visually or using UV-Vis spectroscopy. In addition, we can learn how to encapsulate curcumin, a familiar drug, by encapsulation after MOF synthesis and encapsulation by de novo synthesis. We report for the first time a new synthesis method of MIL101 and de novo synthesis of ZIF-8 with curcumin.

For this project, we used three different metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), each with different geometries and pore sizes: MOF-5, ZIF-8 (ZIF = Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks), and MIL-101(Fe) (MIL = Materials of Institute Lavoisier).13–17 (Figure 1) These MOFs do not require strong acid and harsh condition to be synthesized, which were required for the synthesis of some MOFs. In addition, we can perform the syntheses for two of these MOFs, MOF-5 and ZIF-8, at room temperature under normal pressure. We tested several reported procedures and conditions in order to determine the most ideal conditions to produce larger and clearer crystals, as these crystals allow further analysis using scanning electron microscope (SEM) and tunneling electron microscopy (TEM). Most high schools may not have access to TEM and SEM, but the obtained crystals shapes can be identified using a common optical microscope if the crystals are large enough. The synthesis of MIL-101(Fe) has been reported in a vessel at 110 °C in an oven.16 We successfully modified the condition to be milder for this project so that high school students would be able to successfully perform this experiment without the use of specific instruments. To show an application of MOFs, we demonstrated the adsorption of iodine (I2) and encapsulation of curcumin. Curcumin, a biologically active component of turmeric, was chosen as a drug candidate for student safety, simple extraction from the spice, and easily identifiable color change when absorbed by the MOF. On the other hand, if radioactive iodine is released into the environment by nuclear plant accidents it could be very hazardous and poses a serious health risk for humans. Therefore, the development of a nanoporous material capable of I2 adsorption is of high importance.

Fig. 1.

Three kinds of MOFs (MIL-101 (Fe), MOF-5 and ZIF-8) prepared in this study and their structural representations.

We have also prepared an educational video in which we explain the concept of nanoporous materials in particular MOFs and also demonstrate the laboratory techniques and experiments described in this article.18 We uploaded this video to YouTube and made it publicly available so that teachers, professors, TAs, and both undergraduate and graduate students could easily access it. For students to be able to better understand the applications and preparation of MOFs, a lecture by the instructor prior to class should be implemented. The basic concepts of the characterization techniques used in the experiments should also be taught. (Table 1) Through this instruction and activity, students would learn how to analyze chemical substances through powder x-ray diffraction (PXRD) and UV-Vis spectroscopy, along with how to identify structural differences between molecules using TEM, SEM, and basic microscopes. The utilization of PXRD would teach students how to calculate cellular dimensions and decipher between amorphous and crystalline materials. Through UV-Vis Spectroscopy, students would learn about using light absorption to determine a substrate such as I2. Moreover, these techniques can be used to enable students to better understand MOF mechanisms, structures, and applications.

Table 1.

Topics addressed and learning outcomes associated with the activity.

| Topic Addressed | Learning Outcomes |

|---|---|

| MOFs: Application, Importance, and Synthesis | Students will be able to understand what MOFs are, their applications and uses, how to make them, and their importance to the scientific field. |

| Powder X-Ray Diffraction (PXRD) Analysis | Students will be able to decipher between amorphous and crystalline materials and calculate cellular dimensions of MOFs. Students will also analyze PXRD data. |

| TEM, SEM, and Basic Microscope use | Students will be able to apply basic microscopy skills, while also being able to recognize and identify MOFs structure via TEM and SEM images |

| UV-Visible Spectroscopy Analysis | Students will be able to identify the different light absorptions in order to characterize different substrates. |

| Coordination and Geometry | Students will be able to explain how different metals and linkers can change the geometry of MOFs. |

Synthesis

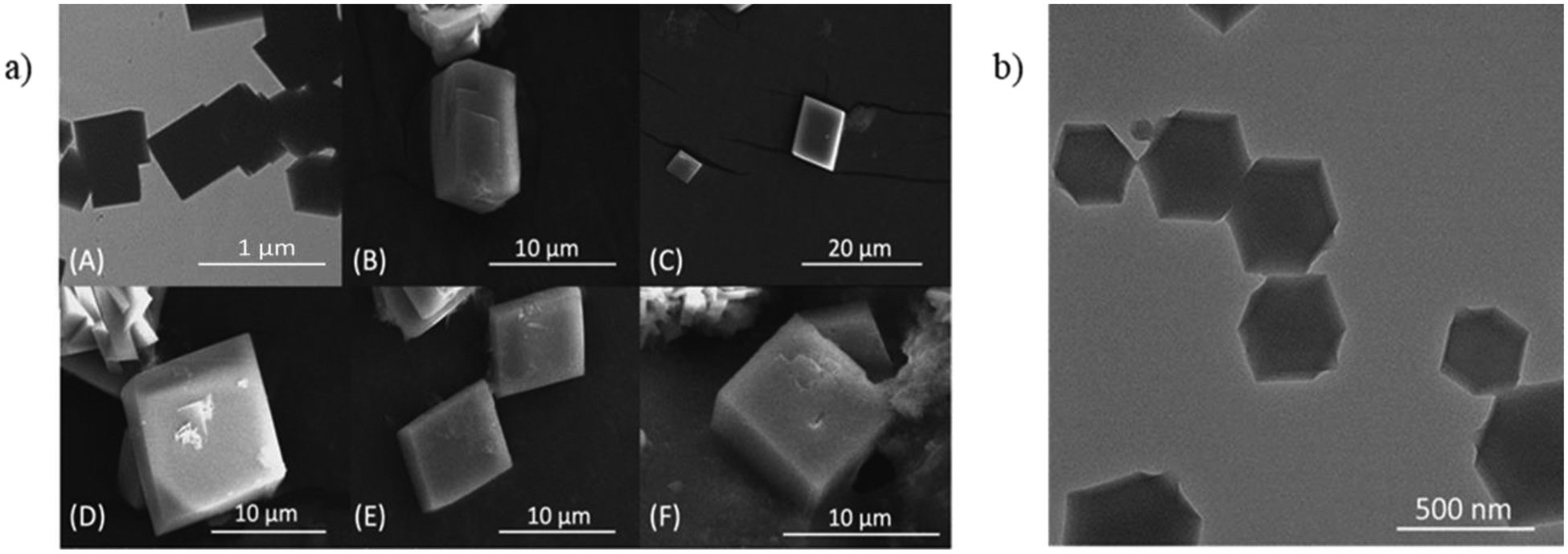

Synthesis for MOF-5, ZIF-8, and MIL-101 are in the Supporting Information (SI). Large crystals of MOF-5 were made at room temperature with stirring for 2.5 hours. The TEM and SEM images of MOF-5 clearly showed cubic crystals (Figure 2a). The MOF-5 was also analyzed by powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD)13 (Fig. S1a). Bigger crystals of ZIF-8 were also synthesized at room temperature, static state for 24 hours. Condition 1 did not produce the expected standard crystalline shape, but it did produce the same XRD pattern19, 20 (Fig. S1b). Therefore, we synthesized the ZIF-8 using the standard methods. The TEM image of ZIF-8 showed hexagonal crystals as shown in Figure 2b. MIL-101 were prepared with modified mild conditions so that it could be performed with experimental equipment more likely to be found in the high school science laboratory. The standard preparation method for MIL-101 was reported. Conditions 1, 2, 3, and 4 were modified from the standard which is the originally reported way16 to be able to prepare them in the high school and undergraduate laboratory setting. For Condition 1, MIL-101 was synthesized at 110 °C for 17 hours in oil bath. Because high school labs typically do not have access to oil baths, we attempted to decrease the heat and get rid of the oil bath so that the synthesis would be feasible for high school students. Thus, in Condition 2, the capped vial was placed in direct contact with the hot plate at 60 °C for 17 hours. The PXRD for Condition 2 revealed the correct hexagonal crystalline shape, which differs from standard MIL-101 crystalline shape. Additionally, the PXRD of Condition 2 matched that of the standard MIL-101 condition, so we surmised that the crystal was still forming the familiar crystal-like standard MIL-101. To make the standard shape of MIL-101, we increased the heating time for Condition 3 and 4 by using a salt bath. Figure 3 shows the TEM and SEM images of each MIL-101 condition and Figure S2 shows their PXRD spectra.

Fig. 2.

a) TEM (A) and SEM (B-F) images of MOF-5. b) TEM image of ZIF-8

Fig. 3.

TEM and SEM images of MIL-101 and their synthesis conditions.

MOF Applications

I2 Adsorption

Iodine solutions (0.1 mM, 0.2 mM, and 0.3 mM) were prepared in methanol. Students then added 5 mg of the synthesized MOFs, MIL-101, ZIF-8, and MOF-5, to 10 mL of the solution respectively while being stirred at 300 rpm at room temperature. Pictures of the MOF solutions were taken at the following timestamps: 30 minutes, 1 hour, 2 hours, 3 hours, 4 hours, 24 hours, and 48 hours. (Figures 4–6) After 48 hours these solutions were centrifuged, separating the MOFs from the iodine solution. As the MOFs were exposed to the iodine solution, they began adsorbing the iodine, resulting in the opaque orange color. Theoretically, if the MOFs have successfully adsorbed all of the iodine, the solution should be completely clear following centrifugation. Of the three MOFs tested, MOF-5 had the most successful results, as the solutions visually had lost all pigment after being centrifuged. Since laboratory periods typically do not last more than a couple hours in the undergraduate setting and often even less in a high school setting, it is recommended that the instructor initiates the experiment before the class starts for students to see the final results, as the MOF would not likely fully adsorb the iodine before the end of the laboratory period.

Fig. 4.

I2 Adsorption with MIL-101 standard. The first, second, and third rows are 0.1mM, 0.2mM, and 0.3mM of I2 in methanol, respectively. MIL-101 itself has pink to orange color.

Fig. 6.

I2 adsorption with MOF-5. The first, second, and third rows are 0.1 mM, 0.2 mM, and 0. 3mM of I2 solution in methanol, respectively.

In order to be analyzed, all MOFs were dried in a vacuum oven at 60 °C for 5 hours. In cases where vacuum oven or oven is not available, longer air exposure time (2–3 days) would be sufficient to dry the MOFs. The dried MOFs were analyzed by PXRD to check their crystallinity before and after I2 adsorption. (Figures S3–5). The PXRDs of both MIL-101 and MOF-5 changed upon exposure to methanol. To ensure that iodine or stirring was not responsible for the structural degradation, control experiments were carried out. First the standard MOFs were stirred for 48 hours in methanol and then dried, and subsequent PXRD analysis revealed structural degradation as indicated by a loss of diffraction peaks. (Figures S10 and S11) The results confirmed that the changes in the PXRD spectra were indeed caused by methanol or stirring exposure rather than adsorption of I2. Afterwards, the MOFs were stirred in DMF for 48 hours and no loss of diffraction peaks were observed in PXRD, this result indicates that methanol is reason for the MOF degradation. (Figure S12)

The adsorption of the iodine by MIL-101, MOF-5, and ZIF-8 were all analyzed by UV-Vis spectroscopy. As conveyed in Figure S6, all the standard peaks of iodine that were dissolved in methanol solvent were detected when adsorbed by the MOFs. MOF5 in particular shows an exceptional capacity for iodine adsorption because it has the most drastic change from standard iodine.

Figures 4–6 show the progression of iodine adsorption for each MOF with different concentrations of iodine solution. The more transparent and colorless the solution, the better the ability of the MOF to encapsulate the iodine. Thus, of the MOFs tested, MOF-5 most effectively adsorbed the iodine at all three concentrations. The superior iodine capture of MOF-5 when compared to MIL-101 and ZIF-8 showcases the effect of high internal surface area on the ability of a MOF to absorb contaminates. MOF-5 has a reported surface area of 3800 m2g−1 which is considerably higher than the reported surface areas of MIL-101 (3054 m2g−1) and ZIF-8 (2800 m2g−1).21–23 The enhancement of iodine capture in MOF-5 compared to the other MOFs tested is a result of a higher internal surface area.

Curcumin Encapsulation

One spatula scoop of turmeric was dissolved in acetone and filtered on filter paper before it was dried. A yellow substance that was collected on the walls of the glassware was curcumin.24, 25 The curcumin was dissolved in methanol and used for the encapsulation. 10 mL of the curcumin solution (2.8μM) was poured into each sample container, and 20 mg of MIL-101, MOF-5, and ZIF-8 was added to each solution, and the solutions were stirred. The reported extinction coefficient of curcumin (ε = 55,000 L·mol−1·cm−1) was used for calculation.26 The color changes were observed for 48 hours (0, 30 minutes, 1 hour, 2 hours, 3 hours, 4 hours, 24 hours, 48 hours) (Figure 7c). Again, a more transparent and colorless mixture indicates a more effective encapsulation by the MOF. All three MOFs appeared to encapsulate the curcumin rather well. The encapsulation of the curcumin in MIL-101, MOF-5, and ZIF-8 were all analyzed by UV-Vis spectroscopy (Figure 7a). The UV spectra of extracted curcumin solution was compared to known spectra.27 As conveyed in Figure 7a, we first prepared a standard ethanol solution of curcumin which was used for three encapsulation experiments using MOFs. All three MOFs show their capacity for curcumin encapsulation. Percentages of curcumin encapsulation were 78% for ZIF-8, 67% for MOF-5, and 98% for MIL-101.

Fig. 7.

a) UV-Vis spectra of curcumin in ethanol encapsulation with MIL101, MOF-5, and ZIF-8. b) PXRD comparison of standard ZIF-8 and curcumin@ZIF-8. c) Curcumin encapsulation with MIL-101, MOF-5, and ZIF-8.

The dried MOFs were analyzed via PXRD to check their crystallinity before and after curcumin encapsulation. (Figures 7b, S7, and S8) The PXRD spectra showed changes following the addition of curcumin, but once again these changes can be attributed to the stability of MOFs in methanol. For the encapsulation of curcumin, we report here the new de novo synthesis of ZIF-8 with curcumin. The extracted curcumin and chemicals for the de novo synthesis of ZIF-8 were mixed for one hour at room temperature. We obtained the yellow ZIF-8 powder, which encapsulated curcumin while ZIF-8 was forming (Figure S9a). The PXRD comparison of parent ZIF-8 with its de novo counterpart confirmed the successful formation of de novo synthesized ZIF-8 as shown in Figure S9b.

Results from an Undergraduate School

In order to examine the practicality of the work presented in this article, undergraduate chemistry students at the University of Arkansas - Fort Smith (UAFS) successfully performed the experiments and demonstrated the adsorption by MOFs by following the procedures described in this article as supplemented by the video we have uploaded to YouTube.18

As a group example, the students at UAFS were able to successfully synthesize MOF-5 and test its application. Due to lab time restraints it is recommended that the instructor have the compound already synthesized prior to class. This enables students to set up synthesis but not have to wait the 7.5–24 hours for the experiment to finish, which makes the lab period more time efficient. These experiments are simple and relatively easy to follow so that students should not need significant assistance.

In order to ascertain the applicability of MOF synthesis at a primarily undergraduate institution with fairly limited instrumentation, students at UAFS took part in a sample study encompassing two lab periods where MOF-5 was first synthesized and then assayed for iodine adsorption following the protocol described in this article. Student feedback on learning objectives was then collected and compiled via lab report and completion of the survey provided in Section 5 of the Supplemental Information (SI). Prior to this process, all students had completed at least one semester of organic chemistry; however, as determined by the survey, students had no prior knowledge of metal-organic frameworks, their versatility, or their synthesis.

For the first lab period, a brief lecture describing the synthesis was presented by the instructor which was followed by playing our YouTube video that highlights the scientific value and versatility of MOFs. Subsequently, MOF-5 synthesis at room temperature with a 7:3 ratio of DMF:EtOH was successful for all groups over a three-hour reaction timeframe, as noted by the formation of white precipitate in solution. It is noteworthy to include that this occurred despite the variances introduced by different sized round bottom flasks, stir bars, and uncalibrated and dissimilar stir plates commonly found in teaching labs. This clearly showed the reproducibility of our MOF simplified procedure. Two washes (first with DMF followed by EtOH) were conducted in 1.5mL Eppendorf tubes at 2000 rpm for 2 minutes with a small tabletop microcentrifuge. Samples were then placed in a vacuum oven to dry overnight in at 60 ˚C.

In lieu of electron microscopy (which students did view in the YouTube video) for direct confirmation of MOF-5 assembly, students tested their MOF-5 samples to assay for iodine adsorption in order to visually confirm the removal of toxic iodine from solution and thus confirm successful MOF-5 synthesis via iodine sequestration. Dried MOF-5 samples stored at room temperature from the previous week were resuspended in 2.0 mL of 0.1 mM iodine in ethanol and incubated for total of one hour. Particles were centrifuged every 30 minutes and 0.5 mL aliquots were removed for time elapse visualization. After 30 minutes and centrifugation, the once distinctly yellow solutions of iodine were visibly transparent and free of color. Additionally, due to the relatively dilute iodine concentrations involved and availability of instrumentation, samples were analyzed via UV/Vis spectroscopy at 360 nm to confirm >98% iodine removal after just 30 minutes as corroborated independently in Figure 6.

Students then prepared lab reports to confer their newfound knowledge on the learning objectives presented in this paper. Upon examination of the lab reports, students were, without exception, able to relate learning about the overall significance of MOFs, their synthesis, and their immense applicative value. Students were able to relate gained knowledge of the mechanistic coordination geometry involved in the assembly process. Though electron microscopy was prohibitive for UAFS, students were able to derive important details about MOF characterization from the video. Additionally, UV/Vis was available for this sample study and, as such, students were able to learn and apply this important analytical technique to confirm MOF-5 assembly via iodine adsorption.

Based on these experiments, performed under relatively low-cost conditions with basic equipment commonly found in undergraduate chemistry laboratories, it is proposed that incorporation of MOF synthesis and analysis should be considered for addition to modern chemical education curricula. Students quickly developed and appreciated a sense of how varying the length and identity of linker systems involved could be employed to create materials of variable pore size using common d-metal coordination geometry. Of the nineteen respondents surveyed, fourteen (73.7%) related that this same technology could be tuned to adapt for different hazardous molecules and/or drugs. Ten students (52.6%) noted that these frameworks could be further functionalized at free carboxylic acid positions on the surface to bind proteins such as antibodies, in turn serving as highly selective filters for separation and purification for antigen counterparts. Respondent students were universally excited to see how modern chemical techniques like MOF synthesis may be potentially employed to selectively remove toxic components from contaminated water and air systems to improve the way of life on our planet. It is important to note that the employment of media in relaying instruction and importance regarding MOF synthesis, analysis, and application in the undergraduate laboratory setting cannot be overstated. The video format instilled a palpable excitement that proved instrumental in creating a positive, instructional laboratory experiment.

We still believe that the content and methods used in this paper are comprehensible to advanced high school chemistry students. We base this on our use of a video showcasing the demonstration with a high school student audience and their informed questions related to our work. We recognize that limitations such as class size, time, and resources exist in a high school classroom when compared to an undergraduate laboratory and that as such implementation of this sort of work in a high school setting is challenging to say the least. We continue to explore ways that we can make this sort of experience available to high school students including, but not limited to providing opportunities for high school students to volunteer in our lab as we perform MOF research.

Conclusion

MOFs as emerging porous nanomaterials have a large internal surface area with a porous nature which make them novel drug delivery systems and pollution control agents due to their ability to encapsulate drugs and toxic materials. MOFs ability to encapsulate compounds, such as curcumin, is demonstrated through an easily identifiable color change that can be seen by the students. As new MOF applications continue to be discovered, it is important that younger generations are taught about new nanoscience in their undergraduate and high school chemistry courses. Most prior reports of MOF syntheses mandate the use of high pressure solvothermal reactions, which are not safely feasible in the high school setting. Our simplified approach to MOF synthesis has set the groundwork for MOF-5, ZIF-8, and MIL-101 to be instituted into high school and undergraduate chemistry education. This work includes a synthesis for MOFs in a simple round bottom flask at ambient pressure making it possible to include MOFs in the curriculum of high school chemistry labs. The use of non-toxic curcumin derived from store bought turmeric lowers the cost of repeating this experiment. Students repeating this experiment can characterize MOFs with an optical microscope. Students ability to learn about and simply prepare these advanced drug carriers will enrich high school and undergraduate chemistry courses and allow them to better understand real world concepts such as drug delivery systems and pollution control. Selected new methods and applications developed in this paper were successfully reproduced by students at The University of Arkansas - Fort Smith (UAFS) which illustrated that advanced chemistry research can be performed in the high school and undergraduate settings.

Supplementary Material

Fig. 5.

I2 adsorption with ZIF-8. The first, second, and third rows are 0.1 mM, 0.2 mM, and 0.3mM solutions of I2 in methanol, respectively.

Acknowledgment

M.H.B. gratefully acknowledges the financial support through the startup funds from the University of Arkansas and the NIH-NIGMS (GM132906).We acknowledge Jarod Meredith and Nicholas Barnett at UAFS who assisted with aspects of this project.

Footnotes

Supporting information

The Supporting Information is available online. It contains information about reagents, hazards, instrumentation and the syntheses of MOFs and PXRD analyses.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Kuppler RJ; Timmons DJ; Fang Q-R; Li J-R; Makal TA; Young MD; Yuan D; Zhao D; Zhuang W; Zhou H-C, Potential applications of metal-organic frameworks. Coord. Chem 2009, 253, 3042–3066. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yap MH; Fow KL; Chen GZ, Synthesis and applications of MOF-derived porous nanostructures. Green Energy & Environment 2017, 2, 218–245. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sakamaki Y; Ozdemir J; Heidrick Z; Watson O; Shahsavari HR; Fereidoonnezhad M; Khosropour AR; Beyzavi MH, Metal–Organic Frameworks and Covalent Organic Frameworks as Platforms for Photodynamic Therapy. Comment Inorg Chem. 2018, 38, 238–293. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ibrahim M; Sabouni R; Husseine GA, Anti-cancer Drug Delivery Using Metal Organic Frameworks (MOFs). Curr. Med. Chem 2017, 24, 193–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wyszogrodzka G; Dorozynski P; Gil B; Roth WJ; Strzempek M; Marszalek B; Weglarz WP; Menaszek E; Strzempek W; Kulinowski P, Iron-Based Metal-Organic Frameworks as a Theranostic Carrier for Local Tuberculosis Therapy. Pharm. Res 2018, 35, 144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Almáši M; Zeleňák V; Palotai P; Beňová E; Zeleňáková A, Metal-organic framework MIL-101(Fe)-NH2 functionalized with different long-chain polyamines as drug delivery system. Inorg. Chem. Commun 2018, 93, 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Della Rocca J; Liu D; Lin W, Nanoscale Metal Organic Frameworks for Biomedical Imaging and Drug Delivery. Acc. Chem. Res 2011, 44, 957–968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith MK; Angle SR; Northrop BH, Preparation and Analysis of Cyclodextrin-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks: Laboratory Experiments Adaptable for High School through Advanced Undergraduate Students. J. Chem. Educ 2015, 92, 368–372. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones DR; DiScenza DJ; Mako TL; Levine M, Environmental Application of Cyclodextrin Metal–Organic Frameworks in an Undergraduate Teaching Laboratory. J. Chem. Educ 2018, 95, 1636–1641. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rood JA; Henderson KW, Synthesis and Small Molecule Exchange Studies of a Magnesium Bisformate Metal–Organic Framework: An Experiment in Host–Guest Chemistry for the Undergraduate Laboratory. J. Chem. Educ 2013, 90, 379–382. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wriedt M; Sculley JP; Aulakh D; Zhou H-C, Using Modern Solid-State Analytical Tools for Investigations of an Advanced Carbon Capture Material: Experiments for the Inorganic Chemistry Laboratory. J. Chem. Educ 2016, 93, 2068–2073. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sumida K; Arnold J, Preparation, Characterization, and Postsynthetic Modification of Metal–Organic Frameworks: Synthetic Experiments for an Undergraduate Laboratory Course in Inorganic Chemistry. J. Chem. Educ 2011, 88, 92–94. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang J-M; Liu Q; Sun W-Y, Shape and size control and gas adsorption of Ni(II)-doped MOF-5 nano/microcrystals. Micropor. Mesopor. Mat 2014, 190, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jian M; Liu B; Liu R; Qu J; Wang H; Zhang X, Water-based synthesis of zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 with high morphology level at room temperature. RSC Adv. 2015; 5, 48433–48441. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor-Pashow KML; Della Rocca J; Xie Z; Tran S; Lin W, Postsynthetic Modifications of Iron-Carboxylate Nanoscale Metal–Organic Frameworks for Imaging and Drug Delivery. J. Am. Chem 2009, 131, 14261–14263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cui F; Deng Q; Sun L, Prussian blue modified metal–organic framework MIL-101(Fe) with intrinsic peroxidase-like catalytic activity as a colorimetric biosensing platform. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 98215–98221. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xie Q; Li Y; Lv Z; Zhou H; Yang X; Chen J; Guo H, Effective Adsorption and Removal of Phosphate from Aqueous Solutions and Eutrophic Water by Fe-based MOFs of MIL-101. Sci. Rep 2017, 7, 3316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lqTQfnK9DEU.

- 19.Jian M; Liu B; Liu R; Qu J; Wang H; Zhang X, Water-based synthesis of zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 with high morphology level at room temperature. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 48433–48441. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Y; Quan X, Adsorption of Sulfamethoxazole on Nanoporous Carbon Derived from Metal-Organic Frameworks. J. Geosci Environ Protect 2017, 5, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaye SS; Dailly A; Yaghi OM; Long JR, Impact of Preparation and Handling on the Hydrogen Storage Properties of Zn4O(1,4-benzenedicarboxylate)3 (MOF-5). J. Am. Chem 2007, 129, 14176–14177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mao P; Qi B; Liu Y; Zhao L; Jiao Y; Zhang Y; Jiang Z; Li Q; Wang J; Chen S; Yang Y, AgII doped MIL-101 and its adsorption of iodine with high speed in solution. J. Solid State Chem 2016, 237, 274–283. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chin M; Cisneros C; Araiza Stephanie M.; Vargas KM; Ishihara KM; Tian F, Rhodamine B degradation by nanosized zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 (ZIF-8). RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 26987–26997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson AM; Mitchell MS; Mohan RS, Isolation of Curcumin from Turmeric. J. Chem. Educ 2000, 77, 359. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pawar HA, A Novel and Simple Approach for Extraction and Isolation of Curcuminoids from Turmeric Rhizomes. Nat Prod Chem Res. 2018, 6, 300. (no next number) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Priyadarsini KI, The chemistry of curcumin: from extraction to therapeutic agent. Molecules 2014, 19, 20091–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Călinescu M; Fiastru M; Bala D; Mihailciuc C; Negreanu-Pîrjol T; Jurcă B, Synthesis, characterization, electrochemical behavior and antioxidant activity of new copper(II) coordination compounds with curcumin derivatives. J. Saudi Chem. Soc 2019, 23, 817–827. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.