Abstract

Introduction:

Cancer clinical trial accruals have been historically low and are affected by several factors. Multidisciplinary Tumor Board Meetings (MTBM) are conducted regularly and immensely help to devise a comprehensive care plan including discussions about clinical trial availability and eligibility.

Objectives:

To evaluate whether patient discussion at MTBM was associated with a higher consent rate for clinical trials at a single tertiary care center.

Methods:

Institutional electronic medical records (EMR) and clinical trials management system (OnCore) were queried to identify all new patient visits in oncology clinics, consents to clinical trials, and MTBM notes between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2015. The association between MTBM discussion and subsequent clinical trial enrollment within 16 weeks of the new patient visit was evaluated using a chi-squared test.

Results:

Between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2015, 11,794 new patients were seen in oncology clinics, and 2,225 patients (18.9 percent) were discussed at MTBMs. MTBM discussion conferred a higher rate of subsequent clinical trial consent within 16 weeks following the patient’s first consultation in an oncology clinic: 4.1 percent for those who were discussed at a MTBM compared 2.8 percent for those not discussed (p<0.01).

Conclusions:

This study provides evidence that MTBMs may be effective in identifying patients eligible for available clinical trials by reviewing eligibility criteria during MTBM discussions. We recommend discussion of all new patients in MTBM for to improve the quality of care provided to those with cancer and enhanced clinical trial accrual.

Keywords: tumor board, multidisciplinary, clinical trial, barriers

Introduction

The National Cancer Institute (NCI) defines tumor board review as “a treatment planning approach in which a number of doctors who are experts in different specialties (or disciplines) review and discuss the medical condition and treatment options of a patient.”1 These multidisciplinary meetings bring together providers from medical oncology, surgical oncology, radiology, radiation-oncology, pathology, and other specialities.1 Tumor board reviews provide a formal structure of communication across various providers involved in a patient’s care, while also benefiting the education of those providers.2 Internally to the University of Iowa Health Care (UIHC), the Multidisciplinary Tumor Board Meeting (MTBM) is the tumor board review, as defined by the NCI. MTBMs can serve multiple purposes; for example, discussion surrounding the best approach to management of a patient’s disease and identification of patients that may be potentially eligible for enrollment into a clinical trial.3

Recommendations from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) state that the best management for any patient with cancer is a clinical trial if one is available.4 Clinical trials are essential to the advancement of comprehensive management of treatment and new drug development; however, it is estimated that less than five percent of adults participate in clinical trials and few studies have shown that MTBMs increase clinical trial enrollment.5–8 There is not a “target” enrollment rate for clinical trials; rather, the goal is to efficiently and effectively conduct research to generate actionable findings that are generalizable to an appropriate population.9 In order to reach this goal, structural, clinical, and attitudinal barriers to clinical trial enrollment must be addressed. Some of these barriers may be addressed through efficient and effective MTBMs, which incorporate clinical trial discussion regarding availability, eligibility, and appropriateness of a clinical trial for the patient.

We conducted a retrospective, descriptive study to understand the role of MTBMs at a National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center serving a large rural population. Additionally, the reasons for non-enrollment were assessed to help identify potential barriers associated with clinical trial accrual.

Methods

The primary objective of the study was to evaluate whether discussion at MTBM was associated with a higher consent rate for clinical trials relative to those not discussed at MTBM. Institutional electronic medical records (EMR) and clinical trials management system (OnCore) were queried to identify all new patient visits in oncology clinics, consents to clinical trials, and tumor board notes between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2015. Applying a 16-week window, new patient consultations between January 1, 2011 and September 10, 2015 were selected for inclusion in the sample to ensure adequate time for a MTBM or consent to a clinical trial to occur. The study ended in 2015 because exogenous changes were made to many of the tumor board meetings, including the addition of new tumor boards. The 16-week window was selected based on knowledge of institutional practices, including obtaining updated medical records from referring providers, schedule of discussion at MTBM (some of which occur biweekly), and completion of additional testing or workup procedures. An assumption was made that MTBM discussion should occur within one month after the initial new patient consult (due to select MTBMs that occur biweekly); therefore, subsequent clinical trial consent would need to occur within 90 days of that discussion. Some specialties either did not conduct MTBMs or initiated MTBMs during the study time period. MTBMs were identified using the standardized tumor board note documentation processes in the EMR. The cohort of new patient consultations was reduced to those seeing providers who participated MTBMs at the time of the visit. Data from OnCore was then queried to identify whether each patient in the final new patient visit cohort had been consented to a clinical trial or discussed at a MTBM within a 16-week window from the date of new patient visit. If a patient was consented for a clinical trial but did not have an “on study” date, the reason for ineligibility was examined. Rural-Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) codes were merged with the primary dataset by the patient’s zip code at the time of their consultation to capture a measure of rurality using publicly available data.10 RUCA codes are based on the Bureau of Census Urbanized Area and Urban Cluster definitions, incorporating commuting information.10

The association between tumor board discussion and subsequent clinical trial enrollment was evaluated using a chi-squared test. To determine whether the association varied by whether the patient was from a rural area or by insurance type, a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test was performed. All tests were two-sided and assessed for significance at the 0.05 level using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

A total of 11,794 new patients were seen at UIHC oncology clinics between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2015 (table 1). Of those, 2,225 patients (18.9 percent) were discussed at MTBMs and 401 patients (3.4 percent) consented to a clinical trial within the 16 weeks following their initial visit. Overall, the majority of patients were covered by public insurance (44.2 percent) and almost 20 percent of patients were uninsured or had unknown insurance coverage at the time of their consultation. As might be expected in a Midwestern comprehensive cancer center, almost 45 percent of patients were from rural areas. Most patients were female (62.9 percent), white (90.7 percent), and non-Hispanic (95.6 percent). Of the 2,225 patients discussed at MTBMs, 92 consented to participate in a clinical trial (figure 1). There were 9,569 new patients in the sample that were never discussed at a MTBM, of which, 265 consented to participate in a clinical trial.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients seen at the University of Iowa Health Care, 2011–2015 (N = 11,794)

| Variable | Level | N | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discussed at Tumor Board Meeting | No | 9569 | 81.1% |

| Yes | 2225 | 18.9% | |

| Consented to Clinical Trial | No | 11393 | 96.6% |

| Yes | 401 | 3.4% | |

| Insurance Coverage | Public | 5209 | 44.2% |

| Private | 4284 | 36.3% | |

| Unknown or uninsured | 2301 | 19.5% | |

| Rural Urban Commuting Area Code | Urban | 6483 | 55.0% |

| Rural | 5290 | 44.9% | |

| Unknown | 21 | 0.2% | |

| Sex | Female | 7413 | 62.9% |

| Male | 4381 | 37.1% | |

| Race | White | 10701 | 90.7% |

| Non-White | 889 | 7.5% | |

| Unknown | 204 | 1.7% | |

| Ethnicity | Non-Hispanic | 11275 | 95.6% |

| Hispanic | 228 | 1.9% | |

| Unknown | 291 | 2.5% | |

Figure 1.

Flowchart of tumor board discussion and subsequent clinical trial consent for patients seen at the University of Iowa Health Care, 2011–2015

MTBM discussion conferred a higher rate of subsequent clinical trial consent within 16 weeks following the patient’s first consultation in an oncology clinic (table 2): 4.1 percent for those who were discussed at a MTBM compared 2.8 percent for those not discussed (p<0.01). The likelihood of clinical trial consent following MTBM discussion did not vary by insurance coverage (public, private, or unknown/uninsured; p=0.28) or RUCA code (rural or urban; p=0.13) at the time of the patient’s consultation in an oncology clinic.

Table 2.

Association between tumor board discussion and subsequent clinical trial consent

| Clinical Trial Consent | P-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor Board Discussion | No (N = 11,437) |

Yes (N = 357) |

|||

|

No (N = 9,569) |

9,304 | (97.2%) | 265 | (2.8%) | <0.01 |

|

Yes (N = 2,225) |

2,133 | (95.9%) | 92 | (4.1%) | |

Row percentages shown

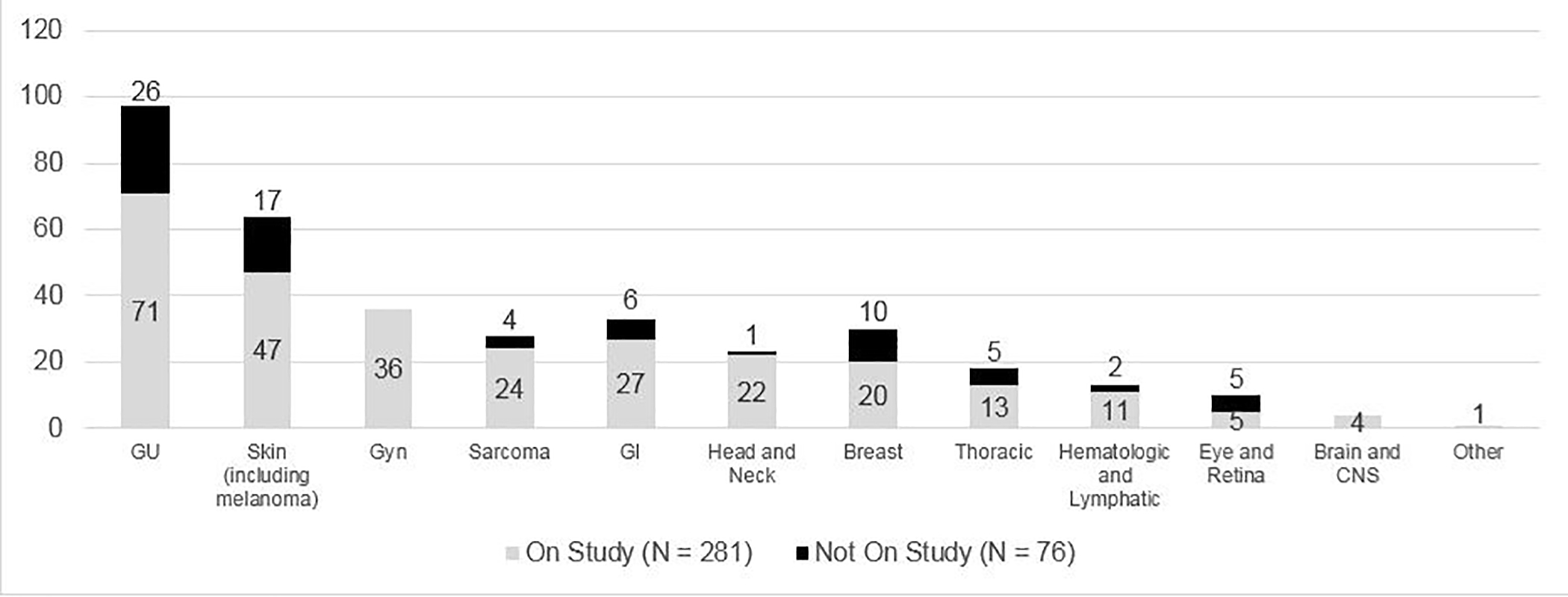

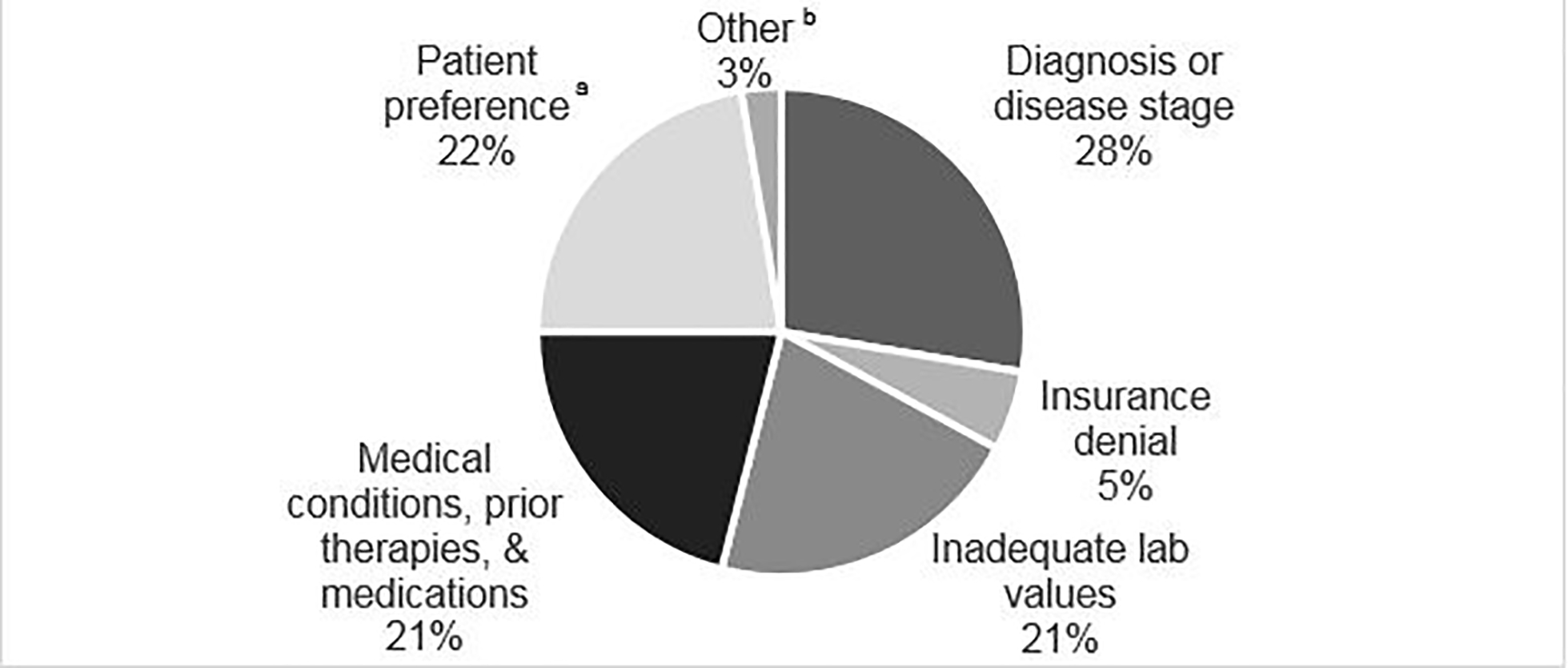

Patients were consented to participate in a clinical trial after meeting the basic criteria for the study; however, additional workup may be needed to determine if the patient meets all inclusion criteria and begins the investigational treatment. During this intermediate time period, it may be realized that some patients do not meet all inclusion criteria of the study. Whether patients continue on the study (defined as starting investigational treatment) following consent were examined by disease site (figure 2). Of the 357 patients who consented to participate in a clinical trial, 92 patients were discussed at a MTBM and 265 were not. Irrespective of MTBM discussion, the summary statistics by disease site (N=76) showed that a substantial proportion of patients who consented with ophthalmic (50 percent), breast (33 percent), thoracic (28 percent), genitourinary (27 percent), and skin (including melanoma; 27 percent) malignancies did not begin their investigational treatment. The most common reasons among these 76 patients who did not start investigational treatment after consenting (figure 3) were change in diagnosis or disease stage (28 percent), patient preference (22 percent), lab value(s) inadequate (21 percent), and medical condition(s) or concurrent medication(s) (18 percent).

Figure 2. Patient investigational study status following consent by disease site (N=357).

aGU: Genitourinary; Gyn: Gynecologic; GI: Gastrointestinal; CNS: Central Nervous System

Figure 3. Reason for non-enrollment in a clinical trial after consent (N=76).

aPatient preference included: travel, sought treatment elsewhere, concerns of toxicity, unsure insurance would cover treatment, and decided not to pursue any treatment.

bOther included: unknown and failed test dose of investigational drug.

Discussion

This descriptive study provides evidence that MTBMs may be effective in attaining patient consent to participate in a clinical trial. However, significant barriers still remain for a patient to start the trial, most notably exclusion criteria of the trial and patient preferences. MTBMs have been part of cancer care for more than fifty years.11 Benefits of MTBM discussion include discussion of complex patients with a wide variety of specialists and expertise represented; diversity in the type of staff present that are aware of inclusion and exclusion criteria for trials and discussion of those criteria in real time; allow for an opportunity to provide the best high-quality, multidisciplinary patient care; opportunity for staff education; and MTBMs provide evidence of increased trial enrollment.2,12 However, the robustness of MTBM discussion, whether pertaining to clinical trial options or not, is highly dependent upon the clinical, research, and administrative staff in attendance and their consistent availability during MTBMs for truly multidisciplinary collaboration and documentation.12–14 Consistency in documentation of patient-specific discussion and consensus across MTBMs present another opportunity for future research and could be due to variation in staff supporting and leading MTBMs.15 Additional research is needed to understand how we can effectively and efficiently overcome these and other administrative obstacles in facilitating high-quality MTBMs.

Clinical barriers pertaining to eligibility criteria for clinical trials, especially in the cancer setting, require a careful balance between opposing dynamics: a narrowly defined sample that allows for an accurate and reliable treatment effect to be measured, coupled with participation that represents the real population of cancer patients that may benefit from the intervention.16 As a result, eligibility criteria for clinical trial participation are often criticized because of a lack of generalizability.16 Our results show that among those did not start their protocol treatment, 70% (53 out of 76 patients) did not start due to exclusion criteria (defined as diagnosis or disease stage; inadequate lab values; or medical conditions, medications, or prior therapies similar to Unger, et. al).5

Multiple reasons including patient preferences such as fears of randomization, the unknown nature of trial participation, cost barriers, and logistics play a significant role in decisions regarding clinical trial participation.5,17 In our study we did not observe a significant impact of insurance coverage or level of rurality in relation to trial consent following MTBM discussion; however, this is likely due to issues related to power as clinical trial consent was low overall. Notably, among patients who did not proceed with protocol therapy after consenting, the reasons included barriers related to travel requirements, concerns related to toxicity, financial distress pertaining to unknown insurance coverage, seeking treatment elsewhere, or deciding to not pursue any treatment, some of which are modifiable. For example, concerns related to additional financial requirements on top of standard care due to indirect costs (e.g., time off work, time away from family or friends) or visit frequency could be discussed with the patient and their family to alleviate concerns and provide additional financial resources. These types of resources may also help improve patient compliance. Additionally, MTBMs provide an opportunity for social limitations or challenges to be discussed by the multidisciplinary team caring for a patient, knowing that the patient or caregiver may not convey the same information to all of their providers.

There are many challenges to receiving high-quality cancer care, and these challenges could disproportionately affect rural residents as compared to urban residents due to distance from treatment facility, transportation barriers, financial issues and restricted access to health care providers.18–20 Additionally, rural residents tend to experience similar or more comorbid conditions than their urban counterparts; therefore, rural residents with cancer may be disproportionately impacted by barriers to clinical trial participation (e.g., frequency and duration of appointments, length of investigational treatment).20 Taken together, the barriers facing rural Americans with cancer to participating in clinical trials may be more difficult to surmount for both the patient and their provider in supporting treatment decisions, whether or not that includes a clinical trial.21

This study is not without limitations. First, we do not know if a clinical trial was available (internally or externally to the institution) when the patient needed to enroll. Second, we do not definitively know that all patients in the sample had a cancer diagnosis as the diagnosis list for the visit was frequently missing, despite the study team’s best effort to gather a representative sample from applicable cancer departments. Third, for those that consented but did not have an on study date, the reason for ineligibility was not consistently documented. However, for patients who did not have a clear reason for ineligibility, a physician member of the research team reviewed the patient medical records to determine the reason. Fourth, the analyses do not take into consideration the patient or provider perspective regarding individual patient appropriateness for clinical trial participation, and we do not know if the MTBM discussion was geared towards clinical trial options. This has been addressed prospectively by the addition of a clinical trial question in the tumor board notes at our institution which may prompt discussion.

Conclusion

This study showed that MTBM discussion was associated with a higher rate of subsequent clinical trial consent within 16 weeks following the patient’s first consultation in an oncology clinic as compared to patients who were not discussed. The consent likelihood was not affected by insurance coverage or RUCA code. We recommend discussion of all new patients in MTBM for to improve the quality of care provided to those with cancer and enhanced clinical trial accrual.

Acknowledgement:

The authors would like to sincerely thank Inez Mattke, Jenni Hunnicutt, Sarah Kelley, and Carmen Tillman for their support of this study.

Funding:

Iowa Cancer Consortium, Iowa Department of Public Health, as well as P30 CA086862 for the Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Statement of Ethics:

Intitutional review board approval was sought prior to starting the study. Informed consent of subjects was not necessary.

Disclosures:

Erin Mobley, Sarah Mott, and Umang Swami have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Mohammed Milhem has the following disclosures: Research funding from Amgen,Novartis,Merck,Pfizer, ER Squibb & Sons, Prometheus. Honoraria from Blueprint Medicine, Immunocore, Amgen, Trieza. Consulting or advisory role Blueprint Medicine, Amgen, Immunocore, Trieza. Varun Monga has the following disclosures: Research funding and travel expenses from Deciphera. Research funding from Orbus Therapeutics, Immuno cellular. Consulting or advisory role from Forma Therapeutics.

References

- 1.NCI. NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms. National Cancer Institute; https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms?cdrid=322893. Accessed July 6, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gross GE. The role of the tumor board in a community hospital. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 1987;37(2):88–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang JH, Vines E, Bertsch H, et al. The impact of a multidisciplinary breast cancer center on recommendations for patient management: the University of Pennsylvania experience. Cancer. 2001;91(7):1231–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NCCN. NCCN Guidelines & Clinical Resources. National Comprehensive Care Network 2014; https://www.nccn.org/about/permissions/reference.aspx. Accessed August 3, 2018.

- 5.Unger JM, Hershman DL, Fleury ME, Vaidya R. Association of patient comorbid conditions with cancer clinical trial participation. JAMA Oncology. 2019;5(3):326–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tejeda HA, Green SB, Trimble EL, et al. Representation of African-Americans, Hispanics, and Whites in National Cancer Institute Cancer Treatment Trials. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1996;88(12):812–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lara PN Jr., Higdon R, Lim N, et al. Prospective evaluation of cancer clinical trial accrual patterns: identifying potential barriers to enrollment. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(6):1728–1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Denicoff AM, McCaskill-Stevens W, Grubbs SS, et al. The National Cancer Institute-American Society of Clinical Oncology Cancer Trial Accrual Symposium: summary and recommendations. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9(6):267–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ACS CAN. Barriers to Patient Enrollment in Therapeutic Clinical Trials for Cancer - A Landscape Report. Washington, D.C.2018. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larson E, Skillman S. Rural Urban Commuting Area code. In. Seattle, WA: WWAMI Rural Health Research Center, University of Washington; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henson DE, Frelick RW, Ford LG, et al. Results of a national survey of characteristics of hospital tumor conferences. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1990;170(1):1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuroki L, Stuckey A, Hirway P, et al. Addressing clinical trials: Can the multidisciplinary tumor board improve participation? A study from an academic women’s cancer program. Gynecologic Oncology. 2010;116(3):295–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scott BL, Srivastava D, Nijhawan RI. The multidisciplinary tumor board for the management of cutaneous neoplasms: A national survey of academic medical centers. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2018;78(6):1216–1218.e1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grunfeld E, Zitzelsberger L, Coristine M, Aspelund F. Barriers and facilitators to enrollment in cancer clinical trials. Cancer. 2002;95(7):1577–1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El Saghir N, Keating N, Carlson R, Khoury K, Fallowfield L. Tumor boards: Optimizing the structure and improving efficiency of multidisciplinary management of patients with cancer worldwide. ASCO Educational Book. 2014:e461–e466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Unger JM, Cook E, Tai E, Bleyer A. Role of clinical trial participation in cancer research: barriers, evidence, and strategies. American Society of Clinical Oncology Education Book. 2016;35:185–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Unger JM, Moseley A, Symington B, Chavez-MacGregor M, Ramsey SD, Hershman DL. Geographic distribution and survival outcomes for rural patients with cancer treated in clinical trials. JAMA Network Open. 2018;1(4):e181235–e181235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wheeler SB, Davis Melinda M. “Taking the bull by the horns”: Four principles to align public health, primary care, and community efforts to improve rural cancer control. Journal of Rural Health. 2017:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mobley EM, Foster KJ, Terry WW. Identifying and understanding the gaps in care experienced by adolescent and young adult cancer patients at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology. 2018;7(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charlton M, Schlichting J, Chioreso C, Ward M, Vikas P. Challenges of rural cancer care in the US. Oncology Journal, Practice & Policy. 2015;29(9). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mobley EM, Charlton ME, Ward MM, Lynch CF. Nonmetropolitan residence and other factors affecting clinical trial enrollment for adolescents and young adults with cancer in a US population–based study. Cancer. 2019;epub, ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]