Abstract

Background

The coral reef aorta (CRA) is a rare disease of extreme calcification in the juxtarenal aorta. These heavily calcified exophytic plaques grow into the lumen and can cause significant stenoses, leading to visceral ischaemia, renovascular hypertension, and claudication. Surgery or percutaneous intervention with stenting carries a high risk of complications and mortality.

Case summary

A 67-year-old female had presented with severe hypertension and exercise limiting claudication for 18 months. On evaluation, she was found to have severe bilateral renal artery stenoses with juxtarenal CRA causing subtotal occlusion. Both renal arteries were stented. For CRA, we used intravascular lithotripsy (IVL) assisted plain balloon angioplasty to minimize possibilities of major dissection and perforation and avoided chimney stent-grafts required to protect visceral and renal arteries. We used a double-balloon technique using a 6 × 60 mm IVL Shockwave M5 catheter and a 9 × 30 mm simple peripheral balloon catheter, inflated simultaneously at the site of CRA as parallel, hugging balloons to have an effective delivery of IVL. Shockwaves were given in juxta/infrarenal aorta to have satisfactory dilatation without any complication. The gradient across aortic narrowing reduced from 80 to 4 mmHg. She had an uneventful recovery and has remained asymptomatic at 6-month follow-up.

Discussion

When CRA is juxtarenal with no safe landing zones for stent-grafts, IVL may be a safe, less complex and effective alternative to the use of juxtarenal aortic stent-graft with multiple chimney or snorkel stent-grafts. This is the first report of a novel use of IVL to treat CRA.

Keywords: Case report, IVL: intravascular lithotripsy, CRA: coral reef aorta

Learning points

Coral reef aorta (CRA) is a rare disease involving juxtarenal aorta and can present with hypertension, visceral ischaemia, and claudication.

Surgery for CRA has high operative mortality and peri-procedure complications. The percutaneous approach carries a higher risk of perforation and dissection of the aorta, and involvement of visceral arteries may make the procedure more complex.

Intravascular lithotripsy (IVL) is a safe, effective, and simple modality for calcific peripheral and coronary lesions. This is the first report of a novel use of IVL to treat CRA.

Introduction

Coral reef aorta (CRA) is a rare disease of extreme calcification of supra, juxta, or infrarenal aorta where these heavily calcified exophytic plaques grow into the lumen and can cause significant stenosis of the abdominal aorta, which may lead to visceral ischaemia, renovascular hypertension, and claudication. The exact pathophysiological basis of such ingrowth is still an enigma. It is a difficult disease to treat: surgical bypass has very high postoperative complications and mortality. Percutaneous intervention with or without a stent of a heavily calcified aorta carries a high risk of dissection and perforation. The stent-graft will need measures to protect visceral and renal branches which will increase the complexity and the cost. We describe a novel use of intravascular lithotripsy (IVL) assisted plain balloon angioplasty to treat juxtarenal CRA.

Timeline

| Time | Event |

|---|---|

| −18 months | Severe hypertension and worsening claudication of both lower limbs. |

| −1 week | Renal duplex Doppler showing bilateral renal artery stenoses and severe, calcific narrowing of infrarenal aorta just distal to the origins of renal arteries. |

| Day 0 | Diagnostic angiography from the right radial route confirmed bilateral 90% ostial stenosis of renal arteries and coral reef aorta (CRA) with subtotal occlusion of the aorta just distal to the renal arteries. Coronary arteries were normal. |

| Day 1 | Non-contrast computed tomography scan of the abdomen to delineate the extent of calcification in CRA. |

| Day 14 | Percutaneous intervention through left radial and right femoral arterial routes: Bilateral renal artery stenting with intravascular lithotripsy assisted balloon angioplasty of CRA. |

| +6 months | Follow-up: asymptomatic with well-controlled blood pressure. |

Case presentation

A 67-year-old female patient presented with a history of hypertension for 4 years and exercise limiting claudication of both lower limbs for 18 months. She was taking chlorthalidone 12.5 mg, cilnidipine 20 mg, hydralazine 25 mg-three times, clonidine 0.2 mg-three times, bisoprolol 10 mg, atorvastatin 40 mg, and aspirin 75 mg per day. She has hypothyroidism for 10 years, well-controlled with thyroxine 100 µg/day. Her dyslipidaemia was controlled with atorvastatin and the present low-density lipoprotein was 60 mg/dL. She had no history of diabetes, smoking, adverse family history, previous radiotherapy, or any history suggesting connective tissue disorder.

On physical examination, she was obese (body mass index: 32.8 kg/m2). Femoral pulses were weak bilaterally. Blood pressure in the arm was 160/60 and in the leg was 80/50 mmHg.

There was a systolic bruit at the umbilical region. The rest of the physical examination was unremarkable.

She had a low haemoglobin (10.2 g/dL), a high serum creatinine (1.42 mg/dL), and a low estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) (42 mL/min/1.73 m2). Rest of haematological tests including erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein and biochemistry were normal.

Electrocardiogram and echocardiogram were normal.

Abdominal sonography showed normal kidneys with marked narrowing of both the renal artery origins with the turbulent high-velocity flow at the renal ostia on both sides (peak velocities at the right and the left renal artery origins were 500 cm/s, and 450 cm/s) (Figure 1A–D). The infrarenal aorta had significant calcification with narrowing and flow acceleration on Doppler.

Figure 1.

(A–D) Renal duplex Doppler of right and left renal artery origins showing high velocity turbulent flow.

Coronary angiography revealed an insignificant disease. Suprarenal aortogram and selective renal angiography revealed significant calcification of juxtarenal aorta and bilateral 90% ostial stenoses in both renal arteries with severe calcific narrowing of the infrarenal aorta (Figure 2A, Video 1).

Figure 2.

(A) Diagnostic suprarenal aortogram: bilateral, severe ostial renal artery stenosis (white arrows). Filling defects in juxtarenal aorta with severe, subtotal occlusion of infrarenal aorta (black arrow). (B) Infrarenal aortogram showing severe aortic narrowing (black arrow).

Non-contrast computed tomography scan of the abdomen revealed CRA involving the juxtarenal aorta (Figure 3A–E).

Figure 3.

(A and B) Non-contrast computed tomography of abdominal aorta: sagittal (A) and coronal (B), long axial view showing significant calcification of juxtarenal aorta (white arrow). (C–E) Non-contrast computed tomography of abdominal aorta: transverse, short axial view showing significant calcification with luminal encroachment and subtotal occlusion (white arrow) of juxtarenal aorta.

The patient was discussed among heart team members. Due to high morbidity and mortality after surgery for CRA in the published literature,1 and the patient’s preference for the non-surgical treatment, the operator decided to proceed with percutaneous intervention. Apart from bilateral renal artery stenting, options for CRA included balloon angioplasty with or without a bare or covered stent in the aorta with chimney and snorkel grafts for visceral and renal arteries. The latter approach would have increased the complexity and cost. We decided to use IVL-assisted balloon angioplasty using a peripheral IVL System (Shockwave Medical, Fremont, CA, USA) to treat CRA. IVL would create micro-fractures in the calcium which will make balloon angioplasty possible. Diameters of both the renal arteries and the infrarenal aorta were 6 mm and 12 mm, respectively. The largest IVL Shockwave M5 catheter has a 7 mm balloon diameter which was small for the aorta of 12 mm diameter. The basic principle of IVL is to use a 1:1 ratio of the balloon to the artery size to have apposition of the balloon to the arterial wall. We decided to use double (hugging) balloons using the formula for the effective balloon size = 0.82 (D1 + D2) where D1 and D2 were the diameters of the two hugging balloons.2 We used a 6 × 60 mm shockwave M5 balloon catheter along with a 9 × 30 mm plain balloon catheter for simultaneous hugging balloon inflation to achieve an effective diameter of 12 mm.

Under local anaesthesia, a 6 F JR4 guiding catheter was introduced through the left radial artery and a 7 F renal guide catheter was introduced through the right femoral artery. Supra and infrarenal aortic pressures were 179/69 mmHg and 99/68 mmHg, respectively (Figure 4A). A diagnostic aortogram, performed from above through the JR4 guiding catheter and from below through the renal guide, demonstrated severe infrarenal aortic narrowing (Figure 2B, Video 2). To allow better renal perfusion during the rest of the procedure in our patient with already reduced eGFR, left renal stenting was performed as the first intervention using a 6 × 15 mm stent. Next, the aortic lesion was crossed from below with a 0.014 inches BMW 300 cm guidewire (Abbott Vascular, USA). After pre-dilatation with a 3.5 × 20 mm balloon catheter, a 6 × 60 mm Shockwave M5 balloon catheter was positioned at the juxtarenal aorta, inflated at 4-atmosphere pressure, and 2 cycles of 30 pulses each were given (Figure 5A and B, Video 3). After initial dilatation with 6 mm IVL balloon, suprarenal and infrarenal segments of the aorta were subjected to shockwave lithotripsy with side-by-side hugging balloons: 6 × 60 mm M5 IVL catheter from the femoral route and 9 × 30 mm Mustang balloon catheter (Boston Scientific Corporation, USA) from the radial route. Six cycles of 30 pulses/cycle shockwaves were given in the juxtarenal aorta. There was adequate dilatation of the aorta with the disappearance of dents on both the balloons (Figure 5C and D, Supplementary material online, Video S1). During this, the ostial part of the left renal artery stent got deformed and was subsequently re-dilated with a 6 × 20 mm balloon catheter. As a last step, from the left radial approach, the right renal artery was stented using a 6 × 15 mm stent. The gradient across the stenotic aortic segment was reduced from 80 mmHg to 4 mmHg (Figure 4B). Check angiogram showed satisfactory dilatation of the abdominal aorta with non-flow limiting intimal flap without any perforation and good flow in both the renal arteries (Figure 5E, Supplementary material online, Video S2). We could not do any intravascular imaging due to non-availability of this modality at our institute. The patient had an uneventful course and was discharged after 2 days.

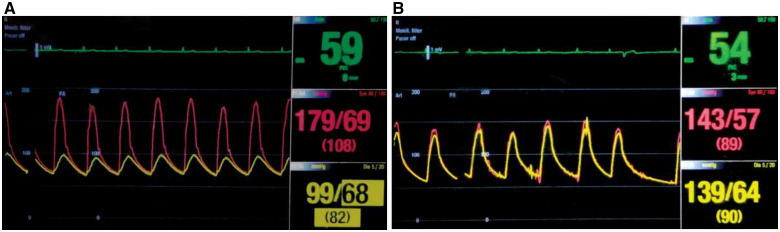

Figure 4.

(A) Simultaneous supra and infrarenal aortic pressures (pre-intervention). Peak gradient: 80 mmHg. (B) Simultaneous supra and infrarenal aortic pressures (post-intervention). Peak gradient reduced to 4 mmHg.

Figure 5.

(A) A 6 × 60 mm intravascular lithotripsy M5 catheter at 4 atmosphere pressure showing indentations in balloon before shockwaves (white arrows). (B) Disappearance of dents in intravascular lithotripsy balloon after shockwaves (white arrows). (C) Simultaneous hugging balloon inflations of a 6 × 60 mm intravascular lithotripsy balloon and a 9 × 30 mm plain balloon before shockwaves. Dent is seen (white arrow). (D) Simultaneous hugging balloon inflations at low pressures after shockwaves. Dent disappeared. (E) Post-intravascular lithotripsy aortogram: Satisfactory dilatation of aorta and both renal arteries.

At 6-month follow-up, she has remained asymptomatic with well-controlled blood pressure on reduced doses of antihypertensives. Her current medications include Cilnidipine 10 mg, Telmisartan 40 mg, Hydralazine 25 mg-twice, Clonidine 0.1 mg-twice, Bisoprolol 5 mg, Atorvastatin 40 mg, Aspirin 75 mg, and Thyroxine 75 mcg per day. Her present Ankle-Brachial Index is 0.95. Her serum creatinine has reduced to 0.83 mg/dL from initial 1.42 mg/dL pre-procedure and eGFR has improved to 71 mL/min/1.73 m2 from initial 42 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Discussion

The CRA was first described by Qvarfordt et al.3 in 1984. Few surgical case series and a very few case reports of the percutaneous approach of management have been described since then.3–9 The pathophysiological basis of CRA is still not completely understood. Positive vascular immunostaining and low serum levels of both fetuin-A and uncarboxylated Matrix Gla-Protein suggest a pathophysiologic role of these calcification inhibitors in the development of CRA.4 We could not measure the blood levels of these compounds because of the unavailability of the testing facility in our state. Calcifications displayed a fine-crystalline character, and elemental analysis revealed hydroxylapatite as the chemical compound.4

The conventional management of CRA is surgery such as thromboendarterectomy, interposition graft, or axillary to iliac artery bypass graft performed as per the localization of the lesion. The operative mortality was reported to be as high as 8.7–11.6%, and the rate of postoperative complications requiring corrective surgery was reported to be 13.9–15.9%.1,5,6

Endovascular intervention can be an alternative approach in selected patients of CRA who have a focal aortic disease. There are a few case reports of the use of bare stent or covered stent-grafts for CRA where the obstructions were in supra or infrarenal aorta with good landing zones and no involvement of visceral or renal arteries.7,8 There is only one case report of the use of covered endovascular repair of the paravisceral CRA where the chimney-tube-snorkel combination was successfully deployed to treat superior mesenteric artery, CRA, and left renal artery respectively.9 Our patient had juxtarenal CRA and bilateral renal artery involvement. The use of covered stent-graft would have needed additional covered stents for visceral and renal arteries and would have made the procedure more complex and costly.

IVL is a novel technique in which multiple lithotripsy emitters deliver a small electrical discharge which vaporizes the fluid and creates a rapidly expanding bubble within the balloon. This bubble generates a series of sonic pressure waves at nearly 50-atmosphere pressure that travel through the fluid-filled balloon and pass through soft vascular tissue, selectively cracking the hardened intimal and medial calcified plaque. These microfractures in calcified plaques make the vessel more compliant to yield to simple balloon dilatation. Feasibility, efficacy, and safety of IVL use for calcific peripheral arterial lesions have been well established in Disrupt PAD I and II studies with no reported major dissections, perforations, abrupt closure, or slow flow/no-reflow.10,11

The operator used two hugging balloons at low pressure to have an effective balloon size of 12 mm to allow apposition of both the balloons to the vessel wall and allow sonic waves to pass through both the balloons. The gradient across the CRA could be reduced from 80 mmHg to 4 mmHg without any major vessel wall injury. As a bailout procedure for the complication, we had standby covered stent-grafts and 12 mm size balloon catheter for aortic tamponade in case of need for emergency surgery.

In the future, the availability of larger size IVL balloons may simplify the procedure for highly calcific lesions of the aorta or its branches. To the best of the author’s knowledge, this is probably the first report of a novel use of IVL in CRA.

Conclusion

CRA is a rare and difficult disease to treat. This 67-year-old female patient with severe hypertension with CRA and bilateral renal artery stenoses was successfully treated with bilateral renal stenting and IVL assisted balloon angioplasty of CRA. When CRA is juxtarenal with no safe landing zones for stent-grafts, IVL may be a safe, less complex and effective alternative to the use of a juxtarenal aortic stent-graft with multiple chimney or snorkel stent-grafts.

Lead author biography

Dr Milan Chag, Interventional, Heart Failure and Heart Transplant Cardiologist and Managing Director of CIMS Hospital, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India. With 30 years of experience in Cardiology, he is appointed as a post-graduate teacher in Cardiology by National Board of Examination, New Delhi. He has more than 100 publications and research projects and is pioneer in establishing Pediatric Cardiology, Structural Heart Intervention Program including TAVR, Primary Angioplasty in STEMI Program and Heart Transplant Program in the State. He is recipient of Lifetime Achievement Award in Cardiovascular Science, Medicine and Surgery by International Academy of Cardiovascular Sciences, Winnipeg, Canada in February 2011.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal - Case Reports online.

Slide sets: A fully edited slide set detailing this case and suitable for local presentation is available online as Supplementary data.

Consent: The authors confirm that the written consent for submission and publication of this case report including images and associated text has been obtained from the patient in line with COPE guidance.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Funding: None declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Grotemeyer D, Pourhassan S, Rehbein H, Voiculescu A, Reinecke P, Sandmann W.. The coral reef aorta—a single centre experience in 70 patients. Int J Angiol 2007;16:98–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rao PS. Influence of balloon size on short-term and long-term results of balloon pulmonary valvuloplasty. Tex Heart Inst J 1987;14:57–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Qvarfordt PG, Reilly LM, Sedwitz MM, Ehrenfeld WK, Stoney RJ.. “Coral reef” atherosclerosis of the suprarenal aorta: a unique clinical entity. J Vasc Surg 1984;1:903–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schlieper G, Grotemeyer D, Aretz A, Schurgers LJ, Kruger T, Rehbein H. et al. Analysis of calcifications in patients with coral reef aorta. Ann Vasc Surg 2010;24:408–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ishigaki T, Matsuda H, Henmi S, Yoshida M, Mukohara N.. Severe obstructive calcification of the descending aorta: a case report of “coral reef aorta”. Ann Vasc Dis 2017;10: 155–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sagban AT, Grotemeyer D, Rehbein H, Sandmann W, Duran M, Balzer KM. et al. Occlusive aortic disease as coral reef aorta—experience in 80 cases. Zentralbl Chir 2010;135:438–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Holfeld J, Gottardi R, Zimpfer D, Dorfmeister M, Dumfarth J, Funovics M. et al. Treatment of symptomatic coral reef aorta by endovascular stent-graft placement. Ann Thorac Surg 2008;85:1817–1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vijayvergiya R, Mohammed S, Kanabar K, Behera A.. Treatment of symptomatic coral reef aorta by a nations self-expanding stent. BMJ Case Rep 2019;12:e229179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Plimon M, Falkensammer J, Taher F, Assadian A.. Covered endovascular repair of the paravisceral aorta. J Vasc Surg Cases Innov Tech 2017;3:188–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brodmann M, Werner M, Brinton TJ, Illindala U, Lansky A, Jaff MR. et al. Safety and performance of lithoplasty for treatment of calcified peripheral artery lesions. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:908–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brodmann M, Werner M, Holden A, Tepe G, Scheinert D, Schwindt A. et al. Primary outcomes and mechanism of action of intravascular lithotripsy in calcified, femoropopliteal lesions: results of Disrupt PAD II. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2019;93:335–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.