Abstract

Background:

Adverse psychological effect of pandemic includes not only increased levels of stress, anxiety, and depression but also cyberchondria - the problematic online health research behavior. It is thought that the distress and uncertainty of pandemic clubbed with information overload and its ambiguity have paved the way for cyberchondria. Students being the vulnerable population, the present study was an effort at understanding cyberchondria in students.

Aim:

The aim of the study is to assess cyberchondria and its association with depression, anxiety, stress, and quality of life (QOL) in dental students during the pandemic.

Materials and Methods:

An online questionnaire-based survey was carried out on dental students. The survey tool comprised a semi-structured pro forma, General Health Questionnaire-12, Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale 21, Cyberchondria Severity Scale 15, and European Health Interview Survey QOL 8.

Results:

The study revealed that 98.7% of the students were affected by one of the constructs of cyberchondria, viz., “excessiveness” (93.7%), followed by “distress” (84.3%) and “reassurance”-seeking behavior (83.7%). Cyberchondria affected girls more than boys and shared robust positive correlation with depression, anxiety, and stress but not QOL. Factors such as stress, anxiety, QOL, and changes in appetite were associated with higher severity of depression. Family financial losses, preexisting psychiatric illness, and media adverse effect shared robust positive associations with severity of depression, anxiety, and stress and an inverse association with QOL. 76.0% of the students expressed excessive worries regarding missing out on clinical exposure, and nearly half of the students were dissatisfied with eLearning. 78.3% of the students experienced changes in sleep; 68.7% had changes in appetite; and 89.0% reported reduction in the level of physical activity.

Conclusion:

Cyberchondria is affecting the large majority of students. Educational institutions must put efforts to sensitize students about cyberchondria.

Keywords: Anxiety, coronavirus, COVID-19, cyberchondria, dental students, depression, eLearning, pandemic, physical activity, psychiatric morbidity, quality of life, stress

With the COVID-19 outbreak, dental colleges had to limit their functionality to emergency management by faculty and suspend student clinics. This reformulation of clinical activities was crucial, as dentistry is one of the very high-risk professions for contracting the virus, due to their scope of practice with aerosol-generating procedures and closeness of contact required for treatment access.[1] The biggest challenge was to strike the balance keeping in view the task of safeguarding the health of students, faculty, staff, and patients; ensuring the continuity and quality of dental education; and keeping up with government guidelines.[2] Hence, a total transition to virtual dental curriculum was an inevitability.[3]

Talking about the plight of students, currently, school closure has confined them to home. Loss of routine has laid the road to adverse lifestyle habits such as sedentary behavior, excessive screen usage, and irregular sleeping and eating practices.[4,5] Pandemic's effect on social connectedness, academics, and family finances have been overwhelming to most students.[6,7] Emerging literature on emotional impact of COVID-19 pandemic has categorically established higher rates of depression, anxiety, and stress among students across the globe.[6,7,8,9,10,11]

The all new and acutely uncertain COVID-19 pandemic has stirred up a massive “infodemic,”[12,13,14,15] the rapid spread and amplification of vast amounts of information and misinformation through communication technologies.[16] The virtual flood of data has made it hard for people in all walks of life to find simple, clear, and reliable piece of information and practical guidance from authentic sources when needed.[17] It has been suggested that, when distressed, peoples' usage patterns and perceptions of social media alter significantly and they seek information until overloaded and fatigued.[18,19,20] Sadly, the social media have facilitated the faster and farther spread of misinformation alongside the information as rapid and large-scale sharing is allowed without quality check and “gate-keeping.” Spread of misinformation may induce commotion, amplify perception of risk,[21] or result in nonrecommended behaviors. The perniciousness of misinformation can range from being merely confusing to actively harmful to life.[22]

Taking up and making sense of the available information is an active cognitive process. A variety of systematic errors in thinking that occur while processing and interpreting information is collectively described as cognitive bias. To gather information, people chose sources, and within these sources, they again selectively pick some of the information, sometimes in a contradictory manner. Such selections are usually influenced by context, selective attention, and emotions, thus making “selection bias,” the tendency to pay more attention to some information than to other, almost unavoidable. Likewise, the tendency to seek information that confirms the beliefs already held and discard information that contradicts these beliefs is “confirmation bias.” Once the information is gathered, it is filtered, classified, and assimilated to make connections with already available knowledge. During this process, a series of biases can arise. The “negative information bias” is the tendency to attach more importance to negative than to positive information and dwell on it. It can result in catastrophic thinking. The “positive information bias” is the tendency to consider oneself as at low-risk for negative consequence, causing unrealistic optimism. The “familiarity or recency bias” is considering familiar or recent things which are easily retrieved from memory as “true.” Unconscious operation of these cognitive biases colors ones' information gathering and processing, thus weakens decision-making.[16,23]

The ever-increasing number of visits to health websites indicates that internet has become the most popular source of health-related information.[24] A survey of 12,262 people in 12 countries across the world including India found that around 46% of people search internet for self-diagnosis.[25] These searches can sometimes be problematic. Cyberchondria denotes such problematic heath research and can be defined as an excessive or repeated search for health-related information on the internet, driven by distress or anxiety about health, which only amplifies such distress or anxiety.[25] Since cyberchondria or problematic online health research is a time-consuming activity over which there is little/nil-perceived control, the affected ones tend to neglect/deprioritize their duties and activities at home, work, or school. Social life and interpersonal relationships also get adversely affected.[26] Past evidence has confirmed associations of cyberchondria with functional impairment, undue anxiety, and altered healthcare utilization.[26,27] Health anxiety, intolerance to uncertainty, and information overload share a robust positive relation with cyberchondria.[28] The superabundance of information on the internet kindles cyberchondria by giving a hope that ultimately perfect explanation will be found for concerned symptoms. Hence, one gets absorbed in research despite all the anxiety generated in the process. Ambiguity and uncertainty of the health-related information also may reinforce cyberchondria as one indulges in long online searches as an attempt to resolve the same.[29] In the present scenario, prevailing health anxiety, unpredictability of the pandemic, clubbed with the information excess, and its ambiguity have paved the way for cyberchondria. Thus, cyberchondria has emerged as one of the pressing mental health issues of today.[27] A study has shown that cyberchondria shares a significant positive correlation with psychological distress and uncertainty of the present pandemic.[30] Another study reported a positive correlation between cyberchondria and current virus anxiety and also that the relationship was additionally moderated by trait health anxiety.[31] However, the literature in this context is sparse. The present study is an effort at understanding cyberchondria and its association with stress, anxiety, depression, and quality of life (QOL) in dental students amid the turmoil caused by the pandemic and the accompanying infodemic.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This cross-sectional study of online survey format was conducted in a dental college of Bengaluru. Institutional Ethics Committee clearance was obtained (EC-2020/F/FT/RP/045 –July 15, 2020). The purpose, nature, and implications of the study were intimated to all the dental students through an official mail along with survey questionnaire developed through Google forms with an appended consent form. The consenting dental undergraduates, interns, and postgraduate students of the institute constituted the study sample. All the questions were made mandatory to eliminate the chance of incomplete responses. Response form per student was limited to one to prevent multiple submissions by a single participant. Survey link was active for the duration of 1 week. Two gentle reminders were sent to all the students within this period. The class teachers of each term of Bachelor of Dental Surgery, faculties in charge of interns, and students pursuing Master of Dental Surgery were contacted by the investigators to explain the study objectives and implications. They were then requested to convey the same to the students to encourage maximum participation. Participants of the survey could fill the details anonymously. Only investigators had the access to view/analyze the responses which ensured confidentiality of the data.

Tools

General Health Questionnaire

General Health Questionnaire-12 (GHQ-12) is a screening tool assessing current mental health and early detection of people at risk of mental illness. Each item has four different responses. The Cronbach's alpha of the GHQ-12 is 0.9.[32,33]

Cyberchondria Severity Scale-15

Derived from the original 33-item scale, the Cyberchondria Severity Scale-15 (CSS-15) comprises five subscales: (1) compulsion (questions 3, 4, and 7) – assesses the extent to which excessive online medical research impedes both online and offline activities; (2) distress (questions 6, 9, and 14) – assesses symptoms of panic attack, anxiety, and disturbed sleep associated with researching health information online; (3) excessiveness (questions 1, 2, and 13) – measures the extent of repetitiveness of research for medical information and the time spent; (4) reassurance (questions 8, 10, and 11) – indicated by the resulting increased anxiety and need to consult with a medical professional about the information acquired from the internet; (5) mistrust of medical professionals (question 5, 12 and 15) – reflecting greater confidence in medical information from the internet than from the doctor. The Cronbach's alpha for the CSS-15 is 0.82 and for its subscales is between 0.67 and 0.86. CSS-15 is more useful for clinical and research application.[34,35]

Depression Anxiety and Stress Scales 21 Items

The Depression Anxiety and Stress Scales 21 Items (DASS-21) is a measure of depression, anxiety, and stress. Each item has four responses. The 21-item version has a cleaner factor structure and smaller inter-factor correlations. The Cronbach's alpha of the depression, anxiety, and stress subscales is 0.94, 0.87, and 0.91, respectively. The Cronbach's alpha of the total scale is 0.93.[36,37]

European Health Interview Survey quality of life 8 items

Derived from the World Health Organization QOL Instrument-Abbreviated Version, the European Health Interview Survey QOL 8 items (EUROHIS-QOL-8) comprises four domains of QOL, namely physical, psychological, social, and environmental, represented by two items each. The overall score is the sum of scores on the eight items divided by the total number of items. Higher scores imply better QOL. The Cronbach's alpha for the scale is 0.78.[38,39,40]

The Survey Questionnaire

The Survey Questionnaire had eight sections. Section 1 comprised a brief about the background and the need for the survey. Section 2 consisted of informed written consent. Section 3 had questions about demography, past medical and psychiatric disorders, and family financial state. Section 4 comprised questions on sleep, appetite, physical activity, screen usage, and substance abuse. Section 5, 6, 7, and 8 had GHQ-12, CSS-15, DASS-21, and EUROHIS-QOL-8, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Ordinal data were expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR) and compared with the Mann–Whitney U-test; categorical variables were expressed as number (%) and compared by χ2 -test. Spearman's rank-order correlation was used for correlation. Multiple regression analyses were performed for predictors of cyberchondria and depression. The analysis was performed using SPSS 18 (IBM, Chicago, USA).

RESULTS

Three hundred out of the total 404 dental students of the college took part in the survey yielding a response rate of 74.2%. Among 300 participants, 246 (82.0%) were girls and 54 (18.0%) were boys with the age range of 18–37 years. Mean (± standard deviation [SD]) age of the students was 22.63 ± 2.88 years. 180 (60.0%) students were pursuing under-graduation, 47 (15.7%) were interns, and 73 (24.3%) were pursuing masters in dental sciences. During the pandemic, 245 (81.7%) students were living with their family and 55 (18.3%) students were living away from their family.

General Health Questionnaire

The median (IQR) score of GHQ of the students was 4.0 (1.0–8.0). One hundred and seventeen (39.0%) students scored ≤2 (cutoff score), indicating that they were free from psychological distress. One hundred and eighty-three (61.0%) students had a score of >2, implying the presence of psychological distress and needed further evaluation.

Cyberchondria

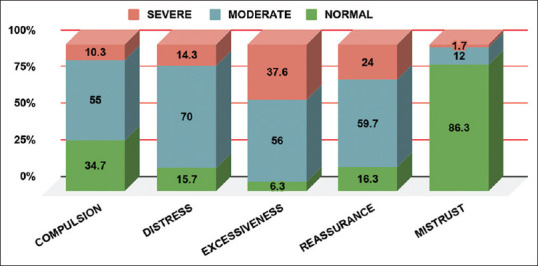

Median (IQR) total score of the CSS-15 was 26.00 (18.25–32.00). Median scores of individual constructs of cyberchondria are mentioned in Table 1. 55.0% of the students were moderately affected and 10.3% of the students were severely affected by compulsion. 70.0% of the students were moderately distressed while 14.3% were severely distressed. 56.0% of the students were moderately affected and 37.7% were severely affected by the excessive health-related search. 59.7% of the students were moderately affected while 24.0% of the students were severely affected by the reassurance-seeking behavior. 12.0% of the students were moderately affected and 1.7% were severely affected by mistrust on medical profession [Table 1 and Figure 1]. Cyberchondria was relatively severe among girls than boys (P = 0.01). Among the five constructs of cyberchondria, girls suffered relatively severe compulsion (P = 0.03) and distress (P = 0.04) compared to boys. Excessiveness, reassurance, and mistrust did not vary with gender [Table 2].

Table 1.

Percentage distribution of students based on construct-wise scores of cyberchondria

| Construct | Compulsion, n (%) | Distress, n (%) | Excessiveness, n (%) | Reassurance, n (%) | Mistrust, n (%) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | Girls | Total | Boys | Girls | Total | Boys | Girls | Total | Boys | Girls | Total | Boys | Girls | Total | |

| Normal | 21 (38.9) | 83 (33.7) | 104 (34.7) | 12 (22.2) | 35 (14.2) | 47 (15.7) | 8 (14.8) | 11 (4.5) | 19 (6.3) | 10 (18.5) | 39 (15.9) | 49 (16.3) | 43 (79.6) | 216 (87.8) | 259 (86.3) |

| Moderate | 30 (55.6) | 135 (54.9) | 165 (55.0) | 37 (68.3) | 173 (70.3) | 210 (70.0) | 30 (55.6) | 138 (56.1) | 168 (56.0) | 33 (61.1) | 146 (59.3) | 179 (59.7) | 10 (18.5) | 26 (10.6) | 36 (12.0) |

| Severe | 3 (5.6) | 28 (11.4) | 31 (10.3) | 5 (9.3) | 38 (15.4) | 43 (14.3) | 16 (29.6) | 97 (39.4) | 113 (37.7) | 11 (20.4) | 61 (24.8) | 72 (24.0) | 1 (1.9) | 4 (1.6) | 5 (1.7) |

| Total | 54 (100) | 246 (100) | 300 (100) | 54 (100) | 246 (100) | 300 (100) | 54 (100) | 246 (100) | 300 (100) | 54 (100) | 246 (100) | 300 (100) | 54 (100) | 246 (100) | 300 (100) |

Figure 1.

Percentage distribution of students among the constructs of cyberchondria

Table 2.

Correlations between individual constructs of cyberchondria and gender

| Scores of individual constructs of cyberchondria | Total score | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compulsion | Distress | Excessiveness | Reassurance | Mistrust | ||||||||

| Median (IQR) | P | Median (IQR) | P | Median (IQR) | P | Median (IQR) | P | Median (IQR) | P | Median (IQR) | P | |

| Boys | 1.00 (0.00-3.00) | 0.03* | 2.00 (1.00-4.00) | 0.04* | 4.00 (3.00-7.00) | 0.07 | 3.50 (1.00-6.00) | 0.41 | 9.00 (8.00-12.00) | 0.13 | 23.00 (15.75-29.25) | 0.01* |

| Girls | 3.00 (0.00-5.00) | 3.00 (1.75-5.00) | 5.00 (3.00-8.00) | 4.00 (2.00-6.25) | 10.00 (8.00-12.00) | 26.00 (19.00-33.00) | ||||||

| Total | 2.00 (0.00-4.75) | 3.00 (1.00-5.00) | 5.00 (3.00-8.00) | 4.00 (2.00-6.00) | 10.00 (8.00-12.00) | 26.00 (18.25-32.00) | ||||||

IQR – Interquartile range

Depression, anxiety, stress, and associated factors

The median (IQR) score of depression, anxiety, and stress subscales of the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale was 4.0 (1.0–8.0), 3.0 (1.0–6.0), and 4.0 (2.0–8.0), respectively. 12.3% of the students were found to have mild depression. 5.7% of the students had moderate depression, and 2.0% had severe depression. 5.0% of the students had mild anxiety, 8.0% had moderate anxiety, 4.3% had severe anxiety, and 0.3% had extremely severe anxiety. Mild stress was reported by 6.3% of the students, and 1.7% of the students had moderate stress [Table 3].

Table 3.

Depression, anxiety, and stress among dental students

| Depression, n (%) | Anxiety, n (%) | Stress, n (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys (n=54) | Girls (n=246) | Total (n=300) | Boys (n=54) | Girls (n=246) | Total (n=300) | Boys (n=54) | Girls (n=246) | Total (n=300) | |

| Normal | 47 (87.0) | 193 (78.5) | 240 (80.0) | 47 (87.0) | 200 (81.3) | 247 (82.3) | 52 (96.3) | 224 (91.1) | 276 (92) |

| Mild | 6 (11.1) | 31 (12.6) | 37 (12.3) | 3 (5.6) | 12 (4.9) | 15 (5.0) | 2 (3.7) | 17 (6.9) | 19 (6.3) |

| Moderate | 1 (1.9) | 16 (6.5) | 17 (5.7) | 3 (5.6) | 21 (8.5) | 24 (8.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (2.0) | 5 (1.7) |

| Severe | 0 (0.0) | 6 (2.4) | 6 (2.0) | 1 (1.9) | 12 (4.9) | 13 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Extremely severe | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

Depression was relatively severe in students who were living away from the family during the pandemic than the students who lived with their family (P = 0.05). Severity of anxiety and stress did not seem to differ among students based on their living arrangement during pandemic (P = 0.15 and P = 0.11, respectively). Students whose families incurred financial crisis had relatively higher severity of depression (P < 0.001), anxiety (P = 0.001), and stress (P < 0.001) compared to the rest. Students with preexisting psychiatric illness suffered relatively severe degrees of depression (P < 0.001), anxiety (P = 0.001), and stress (P < 0.001) compared to their counterparts. Students who reported to have experienced the adversity of media had relatively severe degrees of depression (P < 0.001), anxiety (P = 0.001), and stress (P < 0.001) compared to others. Academic stressor did not share a significant association with depression (P = 0.36), anxiety (P = 0.74), and stress (P = 0.66) in students [Table 4].

Table 4.

Association between various factors and depression, anxiety, stress, and quality of life

| Factors | N (%) | Depression, median (IQR) | P | Anxiety, median (IQR) | P | Stress, median (IQR) | P | QOL, median (IQR) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||||||

| Boys | 54 (12.0%) | 4.00 (1.00-6.00) | 0.24 | 2.00 (0.00-5.00) | 0.34 | 4.00 (1.00-7.25) | 0.22 | 3.63 (3.00-4.00) | 0.99 |

| Girls | 246 (82.0%) | 4.00 (1.00-9.00) | 3.00 (1.00-6.00) | 5.00 (2.00-9.00) | 3.75 (3.13-4.00) | ||||

| Living arrangement during pandemic | |||||||||

| With family | 254 (84.67%) | 4.00 (1.00-8.00) | 0.05* | 3.00 (1.00-6.00) | 0.15 | 4.00 (1.50-8.00) | 0.11 | 3.75 (3.13-4.00) | 0.006* |

| Away from family | 55 (18.33%) | 5.00 (3.00-10.00) | 3.00 (1.00-9.00) | 6.00 (2.00-10.00) | 3.25 (2.88-3.88) | ||||

| Family financial loss | |||||||||

| No | 220 (73.3%) | 3.00 (1.00-7.00) | <0.001** | 2.00 (1.00-5.00) | 0.001** | 4.00 (1.00-7.00) | <0.001** | 3.75 (3.25-4.13) | <0.001** |

| Yes | 80 (26.7%) | 6.00 (3.25-10.00) | 4.00 (2.00-7.75) | 6.00 (4.00-10.00) | 3.13 (2.88-3.84) | ||||

| Preexisting psychiatric condition | |||||||||

| No | 289 (96.3%) | 4.00 (1.00-8.00) | <0.001** | 2.00 (1.00-6.00) | <0.001** | 4.00 (1.50-8.00) | <0.001** | 3.75 (3.13-4.00) | 0.002* |

| Yes | 11 (3.7%) | 13.00 (6.00-21.00) | 14.00 (9.00-15.00) | 14.00 (10.00-20.00) | 2.88 (2.25-3.25) | ||||

| Media adversity | |||||||||

| No | 153 (51.0%) | 3.00 (1.00-6.00) | <0.001** | 2.00 (0.00-5.00) | <0.001** | 3.00 (1.00-7.00) | <0.001** | 3.75 (3.25-4.13) | <0.001** |

| Yes | 147 (49.0%) | 6.00 (3.00-10.00) | 4.00 (1.00-7.00) | 6.00 (3.00-10.00) | 3.50 (3.0-3.88) | ||||

| Academic stressor | |||||||||

| No | 72 (24.0%) | 4.00 (1.00-6.75) | 0.36 | 2.00 (1.00-6.00) | 0.74 | 4.00 (1.25-8.75) | 0.66 | 3.69 (3.00-4.00) | 0.98 |

| Yes | 228 (76.0%) | 4.00 (1.00-8.75) | 3.00 (1.00-6.00) | 4.00 (2.00-8.00) | 3.75 (3.13-4.00) |

IQR – Interquartile range; QOL – Quality of life. *Significant; **Highly Significant

Quality of life and associated factors

The median (IQR) score of EUROHIS-QOL-8 scale was 3.75 (3.13–4.00). Factors such as living away from the family during the pandemic (P = 0.006), financial loss of families (P < 0.001), and preexisting psychiatric conditions (P < 0.002) significantly lowered the QOL in students. Gender (P = 0.99) and academic stressor (P = 0.98) did not share significant relation with QOL. Depression (r = −0.60, P < 0.001), anxiety (r = −0.57, P < 0.001), and stress (r = −0.61, P < 0.001) shared an inverse correlation with the QOL [Table 4].

Cyberchondria and its association with depression, anxiety, and quality of life

Cyberchondria shared a highly significant direct correlation with depression (r = 0.26, P < 0.001), anxiety (r = 0.32, P < 0.001**), and stress (r = 0.31, P < 0.001**). However, the study did not find an association between cyberchondria and QOL (r = −0.09, P < 0.08) [Table 5].

Table 5.

Cyberchondria and its correlation with General Health Questionnaire, depression, anxiety, stress, and quality of life

| Spearman’s rho | GHQ | Stress | Anxiety | Depression | CSS | QOL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GHQ | ||||||

| Correlation coefficient | 1.000 | 0.697** | 0.646** | 0.735** | 0.227** | −0.579** |

| Significant (two-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Stress | ||||||

| Correlation coefficient | 0.697** | 1.000 | 0.832** | 0.792** | 0.305** | −0.607** |

| Significant (two-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Anxiety | ||||||

| Correlation coefficient | 0.646** | 0.832** | 1.000 | 0.727** | 0.320** | −0.566** |

| Significant (two-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Depression | ||||||

| Correlation coefficient | 0.735** | 0.792** | 0.727** | 1.000 | 0.260** | −0.604** |

| Significant (two-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| CSS | ||||||

| Correlation coefficient | 0.227** | 0.305** | 0.320** | 0.260** | 1.000 | −0.099 |

| Significant (two-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.086 | |

| QOL | ||||||

| Correlation coefficient | −0.579** | −0.607** | −0.566** | −0.604** | -0.099 | 1.000 |

| Significant (two-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.086 |

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed). GHQ – General Health Questionnaire; CSS – Cyberchondria Severity Scale; QOL – Quality of life

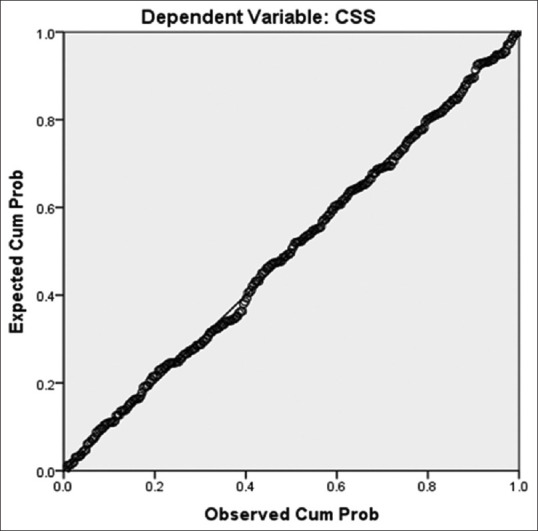

Multiple regression analyses for predictors of cyberchondria

We performed a multiple linear regression with cyberchondria as dependent variable and anxiety, constant fear of getting infected, QOL, always occupied with fear of contamination, changes in appetite as predictor variables by stepwise method. These variables statistically significantly predicted depression, F (6, 293) = 16.278, P < 0.000, R2 = 0.250 [Tables 6 and 7]. The Durbin–Watson d = 2.136 is between the two critical values of 1.5 < d < 2.5 [Table 6]. Anxiety, constant fear of getting infected, QOL, always occupied with fear of contamination, changes in appetite, and living conditions added statistically significant to the prediction (P < 0.05). The standardized beta-coefficients imply that anxiety, QOL, fear of contamination, and fear of getting infected had more impact than appetite and living conditions on cyberchondria [Table 8]. Multicollinearity in our multiple linear regression model can be checked from [Table 8]. Tolerance is within permissible limits >0.1 (or VIF < 10) for all variables. Normality of residuals can be checked with a normal P-P plot which shows that the points follow the normal (diagonal) line with no strong deviations, indicating that the residuals are normally distributed [Figure 2].

Table 6.

Multiple regressions analysis for predictors of cyberchondria: Model summaryg

| Model | R | R2 | Adjusted R2 | Standard error of the estimate | Durbin-Watson |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 0.500f | 0.250 | 0.235 | 9.03644 | 1.936 |

fPredictors: (Constant), anxiety, fear, QOL, always occupied with fear of contamination, changes in appetite, living conditions; gDependent variable: CSS. CSS – Cyberchondria Severity Scale; QOL – Quality of life

Table 7.

Multiple regressions analysis for predictors of cyberchondria: ANOVAa

| Model6 | Sum of squares | df | Mean square | F | Significant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 7975.190 | 6 | 1329.198 | 16.278 | 0.000g |

| Residual | 23925.597 | 293 | 81.657 | ||

| Total | 31900.787 | 299 |

aDependent variable: CSS; gPredictors: (Constant), anxiety, fear, QOL, Ocd, appetite, living. CSS – Cyberchondria Severity Scale; QOL – Quality of life

Table 8.

Multiple regressions analysis for predictors of cyberchondria: Coefficientsa

| Model 6 | Unstandardized coefficients | Standardized coefficients β | t | Significant | 95.0% CI for B | Collinearity statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | Lower bound | Upper bound | Tolerance | VIF | ||||

| Constant | 4.683 | 4.386 | 1.068 | 0.286 | −3.948 | 13.315 | |||

| Anxiety | 0.967 | 0.149 | 0.411 | 6.474 | 0.000 | 0.673 | 1.261 | 0.636 | 1.572 |

| Constant fear of getting infected | 2.219 | 0.875 | 0.154 | 2.535 | 0.012 | 0.497 | 3.942 | 0.692 | 1.444 |

| QOL | 0.506 | 0.117 | 0.277 | 4.323 | 0.000 | 0.275 | 0.736 | 0.623 | 1.605 |

| Always occupied with fear of contamination | 3.730 | 1.193 | 0.180 | 3.128 | 0.002 | 1.383 | 6.077 | 0.771 | 1.296 |

| Changes in Appetite | 1.047 | 0.390 | 0.142 | 2.685 | 0.008 | 0.280 | 1.815 | 0.914 | 1.094 |

| Living conditions | −2.741 | 1.365 | −0.103 | −2.007 | 0.046 | −5.428 | −0.053 | 0.975 | 1.026 |

aDependent variable: CSS. CSS – Cyberchondria Severity Scale; SE – Standard error; CI – Confidence interval; QOL – Quality of life; VIF – Variance inflation factor

Figure 2.

Normal P-P plot of Regression Standardized Residual

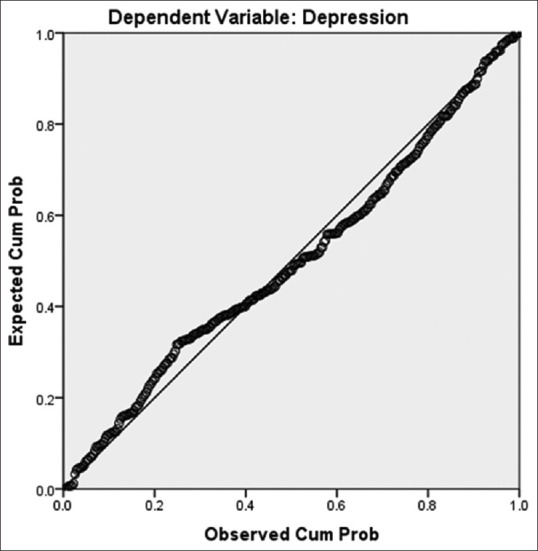

Multiple regression analyses for predictors of depression

To summarize, a multiple regression was run to predict depression from residence, appetite, sleep, GHQ, anxiety stress, and QOL. These variables statistically significantly predicted depression, F (5, 294) =190.725, P < 0.000, R2 = 0.764. The Dubin–Watson is 2.240 [Tables 9 and 10]. Stress, GHQ, QOL, anxiety, and changes in appetite added statistically significantly to the prediction (P < 0.05). The standardized beta-coefficients show that stress, GHQ, and anxiety had more impact than changes in appetite on depression [Table 11]. QOL had a negative impact on depression. A normal P-P plot shows that the points follow the normal (diagonal) line with no strong deviations, indicating that the residuals are normally distributed [Figure 3].

Table 9.

Multiple regressions analysis for the factors associated with depression: Model summaryf

| Model | R | R2 | Adjusted R2 | Standard error of the estimate | Durbin-Watson |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 0.874e | 0.764 | 0.760 | 2.54532 | 2.240 |

ePredictors: (Constant), stress, GHQ, QOL, anxiety, changes in appetite; fDependent variable: Depression. GHQ – General Health Questionnaire; QOL – Quality of life

Table 10.

Multiple regressions analysis for predictors of depression: ANOVAa

| Model 5 | Sum of squares | df | Mean square | F | Significant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | 6178.198 | 5 | 1235.640 | 190.725 | 0.000f |

| Residual | 1904.718 | 294 | 6.479 | ||

| Total | 8082.917 | 299 |

aDependent variable: Depression; fPredictors: (Constant), Stress, GHQ, QOL, Anxiety, Changes in appetite. GHQ – General Health Questionnaire; QOL – Quality of life

Table 11.

Multiple regressions analysis for predictors of depression: Coefficientsa

| Model 5 | Unstandardized coefficients | Standardized coefficients β | t | Significant | 95.0% CI for B | Collinearity statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | Lower bound | Upper bound | Tolerance | VIF | ||||

| Anxiety | 0.171 | 0.069 | 00.144 | 2.482 | 0.014 | 0.035 | 0.306 | 0.242 | 4.129 |

| Constant | 3.194 | 1.190 | 2.683 | 0.008 | 0.851 | 5.537 | |||

| Stress | 0.470 | 0.068 | 0.448 | 6.948 | 0.000 | 0.337 | 0.603 | 0.193 | 5.186 |

| GHQ | 0.311 | 0.056 | 0.230 | 5.504 | 0.000 | 0.199 | 0.422 | 0.457 | 2.188 |

| QOL | −0.105 | 0.035 | −0.115 | −3.007 | 0.003 | −0.174 | −0.036 | 0.552 | 1.811 |

| Anxiety | 0.187 | 0.069 | 0.157 | 2.724 | 0.007 | 0.052 | 0.321 | 0.240 | 4.170 |

| Changes in appetite | 0.259 | 0.110 | 0.070 | 2.353 | 0.019 | 0.042 | 0.476 | 0.911 | 1.097 |

aDependent variable: Depression. GHQ – General Health Questionnaire; SE – Standard error; CI – Confidence interval; QOL – Quality of life; VIF – Variance inflation factor

Figure 3.

Normal P-P plot of Regression Standardized Residual

Concerns about modified academic curriculum and eLearning

76.0% of the students reported excessive worries about missing the cleaning exposure, practical classes, and classroom teaching. 5.0% of the students found online teaching to be as good as classroom teaching. 44.0% of the students were comfortable with online classes. 35.7% of the students reported interruption in learning due to network/electricity/other miscellaneous issues. 15.3% of the students expressed extreme dissatisfaction with online teaching as they faced issues with concentration which impaired learning.

Changes in appetite, sleep, and physical activity

Overall, 68.7% of the students reported to have experienced changes in appetite in one or the other form. 27.7% of the students reported increased appetite. 18.3% of the students experienced diminished appetite. 7.0% of the students admitted frequent eating without adequate appetite, and 15.7% of the students reported craving for high calorie food and sugars. 78.3% of the students had change in sleep. 27.3% of the students experienced increased sleep. 12.3% of the students reported reduced sleep. 24.7% of the students reported reversal of sleep-wake cycle and 14.0% of the students had issues with quality of sleep. 89.0% of the students reported reduction in the level of physical activity, of which 25.3% of the students admitted major reduction, 39% experienced moderate reduction, and 24.7% reported mild reduction in the level of physical activity during pandemic.

DISCUSSION

Cyberchondria and its associations

Only 1.3% of the total students were found to have scored within normal range in all the five constructs of CSS-15. Remaining 98.7% of the students were either moderately or severely affected by one or the other constructs of cyberchondria. Median (IQR) of total score of cyberchondria scale was 26.00 (18.25–32.00), which is in line with a study in Oman wherein the mean (SD) score was 30.7 (9.8) in a sample of the general population (n = 393) during the COVID-19 pandemic.[30] Our study finding about the various constructs of cyberchondria is similar to a recent Indian study wherein it was found that all the students of the study were affected by excessiveness and reassurance construct, 92% by distress, 75% by compulsion, and 19% by mistrust on medical professional.[30] However, our findings are strikingly higher than a previous Indian study which reported 55.6% prevalence of cyberchondria in graduate employees.[41] We believe that the distress, uncertainty associated with the pandemic, and over availability of health data would explain the higher proportion of people getting affected by cyberchondria in our study. We found that cyberchondria was relatively more severe among girls than boys. Girls suffered greater severity of distress and compulsion than boys in our study. However, the excessiveness, reassurance, and mistrust did not vary with gender. Our findings are similar to a study done by Jungmann et al.[31] in terms of association between gender and distress and mistrust, but not in terms of the association of gender with compulsion, excessiveness, and reassurance. Our study established a highly significant positive correlation between cyberchondria and mental health issues such as depression, anxiety, and stress, which is similar to the finding by Markala et al.[41] Although the present study implicated a negative correlation between cyberchondria and QOL of students, it was not statistically significant. This is similar to the study by Mathes et al.[42] wherein, on accounting for the overlap between both health anxiety and cyberchondria, health anxiety was moderately associated with poorer QOL and cyberchondria was strongly associated with greater functional impairment. However, when accounting for health anxiety, cyberchondria was not associated with poor QOL.

Depression, anxiety, stress, and quality of life

The study found that 20% of the students had depression, 17.7% had anxiety, and 8% had reported to be under stress. Overall findings of depression, anxiety, and stress levels in our study were much lesser than a study on mixed student population.[9] Better understanding of the situation by dental students may explain the lower rates. Our findings of anxiety among students was similar to studies by Cao et al.[7] and Shailaja et al.[11] on medical students. Findings of depression and anxiety among students were similar to study by Chang et al.[8] Mean score of QOL of the students in our study was in par with reference values of the QOL of few European countries,[38,40] indicative of good QOL. Depression, anxiety, and stress shared inverse relation with the QOL. Factors such as living away from the family during pandemic were associated with higher severity of depression. Family financial losses, preexisting psychiatric illness, and media adverse effect shared robust positive associations with severity of depression, anxiety, and stress and a highly significant negative association with QOL. Gender and academic stressor did not seem to share any relationship with mental health issues or QOL in our study. In a study by Chang et al.,[8] factors such as residence in rural areas, pursuing nonmedical majors, and excessive negative information concerning the pandemic increased the likelihood of anxiety. The female gender, residence in suburbs, alcohol abuse, and excessive negative information on pandemic had direct relation with depression. Factors such as greater awareness about pandemic and higher changes in future health behaviors were associated with less anxiety and depression. In a study by Son et al.,[6] fear and worry about their own health or of their loved ones, problems in concentration, disturbed sleep, social isolation, and academic concerns were identified as stressors precipitating the negative emotional state in students.

Academic concerns

In times like this, though eLearning has emerged as a successful adjunct, this cannot be applied in its pure form to all disciplines. For instance, in medicine where patient care is a primary goal, students need to attend clinics to observe and provide patient care while acquiring skills and competencies. Live patient contact is an irreplaceable tenet of clinical learning, and no virtual session can match this learning experience.[4,43,44] Furthermore, rush for the transition from classroom teaching to virtual teaching did not allow sufficient preparation time to learn and adapt to the new normal form of learning. Virtual learning is subjected to issues such as connectivity, technicality issues, and electricity. Adding to this, internet-based learning takes place at relaxed ambience of home without the vigilance of instructor. Students may be detracted by mobile phones and web browsing which may further dilute its effectiveness compared to face-to-face teaching.[45] In our study, 76.0% of the students reported excessive worries about missing out on the clinical exposure and classroom teaching. 51.0% of the students reported dissatisfaction with eLearning. Our study findings are in line with the study by Hattar et al.,[4] in which more than half of dental students felt less motivated by eLearning and 87% of the students reported that their clinical training was negatively affected.

Changes in appetite, sleep, and physical activities

In our study, 68.7% of the students reported to have experienced changes in appetite and 78.3% reported changes in sleep. 89.0% of the students reported reduction in the level of physical activity. Our findings of sleep and appetite disturbances is similar to the study by Shailaja et al.,[11] wherein 75.1% of the medical students reported sleep disturbances and 53.6% of the students had changes in appetite post closure of medical schools due to pandemic.

Limitations

Study population was limited to the consenting students of a single dental college; inclusion of students from various dental colleges across India would have yielded better results and interpretations. The present study was cross-sectional, prospective study design that would have been better.

CONCLUSION

Availability of large amount of information about the current crisis has raised serious concerns over people's excessive information consuming. In cyberchondria, individuals search for a great deal of information, inconsistent information, and uncertainty about its validity keep one hooked to the internet. This results in information obesity and evokes undue stress and anxiety. Adhering to the information diet, i.e., taking responsibility for the type of information consumed can curtail cyberchondria and its negative consequences. It falls upon the governments and concerned bodies to regulate the infodemic, raise awareness about cyberchondria, and equip the general public with health information literacy. The relevant educational bodies and institutes must aid in sensitizing the students about cyberchondria. A multidimensional approach involving stakeholders, patients, doctors, mental health professionals, and technologies is crucial to address the same.[29,46]

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Doughty F, Moshkun C. The impact of COVID-19 on dental education and training. Dent Update. 2020;47:527–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iyer P, Aziz K, Ojcius DM. Impact of COVID-19 on dental education in the United States. J Dent Educ. 2020;84:718–22. doi: 10.1002/jdd.12163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hattar S, AlHadidi A, Sawair FA, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on dental academia. Students' experience in online education and expectations for a predictable practice. Research Square. 2020 DOI: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-54480/v1. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang G, Zhang Y, Zhao J, Zhang J, Jiang F. Mitigate the effects of home confinement on children during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet. 2020;395:945–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30547-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xiang M, Zhang Z, Kuwahara K. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents' lifestyle behavior larger than expected. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;63:531–2. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Son C, Hegde S, Smith A, Wang X, Sasangohar F. Effects of COVID-19 on College Students' Mental Health in the United States: Interview Survey Study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e21279. doi: 10.2196/21279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao W, Fang Z, Hou G, Han M, Xu X, Dong J, et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020;287:112934. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang J, Yuan Y, Wang D. Mental health status and its influencing factors among college students during the epidemic of COVID-19. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2020;40:171–6. doi: 10.12122/j.issn.1673-4254.2020.02.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Odriozola-González P, Planchuelo-Gómez Á, Irurtia MJ, de Luis-García R. Psychological effects of the COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown among students and workers of a Spanish university. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113108. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Essadek A, Rabeyron T. Mental health of French students during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:392–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shailaja B, Singh H, Chaudhury S, Thyloth M. COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath: Knowledge, attitude, behavior, and mental healthcare needs of medical undergraduates. Ind Psychiatry J. 2020;29:51–60. doi: 10.4103/ipj.ipj_117_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zarocostas J. How to fight an infodemic. Lancet. 2020;395:676. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30461-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larson HJ. A call to arms: Helping family, friends and communities navigate the COVID-19 infodemic. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:449–50. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0380-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hua J, Shaw R. Corona virus (COVID-19) “Infodemic” and emerging issues through a data lens: The case of China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:2309. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17072309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Datta R, Yadav AK, Singh A, Datta K, Bansal A. The infodemics of COVID-19 amongst healthcare professionals in India. Med J Armed Forces India. 2020;76:276–83. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2020.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okan O, Bollweg TM, Berens EM, Hurrelmann K, Bauer U, Schaeffer D. Coronavirus-related health literacy: A cross-sectional study in adults during the COVID-19 infodemic in Germany. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:5503. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17155503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.An ad hoc WHO Technical Consultation Managing the COVID-19 Infodemic: Call for Action. [Last accessed on 2020 Oct 09]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240010314 .

- 18.Maier C, Laumer S, Eckhardt A, Weitzel T. Giving too much social support: Social overload on social networking sites. Eur J Inf Syst. 2015;24:447–64. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whelan E, Islam AN, Brooks S. Is boredom proneness related to social media overload and fatigue? A stress–strain–outcome approach. Internet Res. 2020;30:869–87. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laato S, Islam AN, Islam MN, Whelan E. What drives unverified information sharing and cyberchondria during the COVID-19 pandemic? Eur J Inf Syst. 2020;29:288–305. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chao M, Xue D, Liu T, Yang H, Hall BJ. Media use and acute psychological outcomes during COVID-19 outbreak in China. J Anxiety Disord. 2020;74:102248. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pulido CM, Villarejo-Carballido B, Redondo-Sama G, Gómez A. COVID-19 infodemic: More retweets for science-based information on coronavirus than for false information. Int Soc. 2020;35:377–92. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van den Broucke S. Why health promotion matters to the COVID-19 pandemic, and vice versa. Health Promot Int. 2020;35:181–6. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daaa042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Starcevic V, Berle D. Cyberchondria: An old phenomenon in a new guise? In: Aboujaoude E, Starcevic V, editors. Mental Health in the Digital Age: Grave Dangers, Great Promise. New York: Oxford University Press; 2015. pp. 106–17. [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDaid D, Park AL. Bupa Health Pulse 2010. Online Health: Untangling the Web. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Starcevic V, Berle D, Arnáez S. Recent insights into cyberchondria. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020;22:56. doi: 10.1007/s11920-020-01179-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doherty-Torstrick ER, Walton KE, Fallon BA. Cyberchondria: Parsing health anxiety from online behavior. Psychosomatics. 2016;57:390–400. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norr AM, Albanese BJ, Oglesby ME, Allan NP, Schmidt NB. Anxiety sensitivity and intolerance of uncertainty as potential risk factors for cyberchondria. J Affect Disord. 2015;174:64–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Starcevic V, Berle D. Cyberchondria: Towards a better understanding of excessive health-related internet use. Expert Rev Neurother. 2013;13:205–13. doi: 10.1586/ern.12.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Al Dameery K, Quteshat M, Al Harthy I, Khalaf A. Cyberchondria, uncertainty, and psychological distress among Omanis during COVID-19: An online cross-sectional survey. Research Square. 2020. [Accessed 2021 Feb 08]. PREPRINT (Version 1) Doi: 10.21203/rs. 3.rs-84556/v1. Available from: https://assets.researchsquare.com/files/rs-84556/v1/ea134835-5b93-4c91-837f-af5b18c5bbac.pdf .

- 31.Jungmann SM, Witthöft M. Health anxiety, cyberchondria, and coping in the current COVID-19 pandemic: Which factors are related to coronavirus anxiety? J Anxiety Disord. 2020;73:102239. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qin M, Vlachantoni A, Evandrou M, Falkingham J. General Health Questionnaire-12 reliability, factor structure, and external validity among older adults in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2018;60:56–9. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_112_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liang Y, Wang L, Yin X. The factor structure of the 12-item general health questionnaire (GHQ-12) in young Chinese civil servants. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14:136. doi: 10.1186/s12955-016-0539-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Starcevic V, Berle D, Arnáez S, Vismara M, Fineberg NA. The assessment of cyberchondria: Instruments for assessing problematic online health-related research. Curr Addict Rep. 2020;30:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dagar D, Kakodkar P, Shetiya SH. Evaluating the cyberchondria construct among computer engineering students in Pune (India) using Cyberchondria Severity Scale (CSS-15) Indian J Occup Environ Med. 2019;23:117–20. doi: 10.4103/ijoem.IJOEM_217_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Antony MM, Bieling PJ, Cox BJ, Enns MW, Swinson RP. Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales in clinical groups and a community sample. Psychol Assess. 1998;10:176–81. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Henry JD, Crawford JR. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol. 2005;44:227–39. doi: 10.1348/014466505X29657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmidt S, Mühlan H, Power M. The EUROHIS-QOL 8-item index: Psychometric results of a cross-cultural field study. Eur J Public Health. 2006;16:420–8. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.da Rocha NS, Power MJ, Bushnell DM, Fleck MP. The EUROHIS-QOL 8-item index: Comparative psychometric properties to its parent WHOQOL-BREF. Value Health. 2012;15:449–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bergman E, Löyttyniemi E, Rautava P, Veromaa V, Korhonen PE. Ideal cardiovascular health and quality of life among Finnish municipal employees. Prev Med Rep. 2019;15:100922. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2019.100922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Makarla S, Gopichandran V, Tondare D. Prevalence and correlates of cyberchondria among professionals working in the information technology sector in Chennai, India: A cross-sectional study. J Postgrad Med. 2019;65:87–92. doi: 10.4103/jpgm.JPGM_293_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mathes BM, Norr AM, Allan NP, Albanese BJ, Schmidt NB. Cyberchondria: Overlap with health anxiety and unique relations with impairment, quality of life, and service utilization. Psychiatry Res. 2018;261:204–11. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sahu P. Closure of universities due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Impact on education and mental health of students and academic staff. Cureus. 2020;12:e7541. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sahi PK, Mishra D, Singh T. Medical education amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Indian Pediatr. 2020;57:652–7. doi: 10.1007/s13312-020-1894-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haley CM, Brown B. Adapting Problem-based learning curricula to a virtual environment. J Dent Educ. 2020. pp. 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1002/jdd.12189 . [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Ashrafi-Rizi H, Kazempour Z. Information diet in COVID-19 crisis; a commentary. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2020;8:e30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]