Abstract

Objective:

Using the unit-level data of women aged 15–49 years from National Family Health Survey-IV (2015–2016), the article maps the prevalence of hysterectomy across districts in India and examines its determinants.

Methods:

Descriptive statistics, multivariate techniques, Moran’s Index and Local indicators of Spatial Association were used to understand the objectives. The data were analysed in STATA 14.2, Geo-Da and Arc-GIS.

Results:

In India, the prevalence of hysterectomy operation was 3.2%, the highest in Andhra Pradesh (8.9%) and the lowest in Assam (0.9%). Rural India had higher a prevalence than urban India. The majority of women underwent the operation in private hospitals. Hysterectomy prevalence ranged between 3% and 5% in 126 districts, 5% and 7% in 47 districts and more than 7% in 26 districts. Moran’s Index (0.58) indicated the positive autocorrelation for the prevalence of hysterectomy among districts; a total of 202 districts had significant neighbourhood association. Variation in the prevalence of hysterectomy was attributed to the factors at the primary sampling unit, district and state level. Age, parity, wealth and insurance were positively associated with the prevalence of hysterectomy, whereas education and sterilization was negatively associated.

Conclusion:

Hysterectomy operation in India presented the geographical, socio-economic, demographic and medical phenomenon. The high prevalence of hysterectomy in many parts of the country suggested conducting in-depth studies, considering the life cycle approach and providing counselling and education to women about their reproductive rights and informed choice. Surveillance and medical audits and promoting the judicial use of health insurance can be of great help.

Keywords: hysterectomy, determinants, spatial, district, India

Introduction

Hysterectomy is one of the most frequently performed surgical procedures during reproductive ages in many countries worldwide after caesarean section. 1 It involves removal of the uterine corpus with (total hysterectomy) or without the cervix (subtotal or supracervical hysterectomy) to cure a number of gynaecological complaints. The hysterectomy route can be via laparotomy, vaginally, by applying minimally invasive techniques (laparoscopy, robotic surgery) or a combination of the latter two. 2 Medical reasons for hysterectomy include uterine cancer and other non-cancerous uterine conditions such as fibroids, endometriosis, prolapse and other uterine disorders. 3 Several times, many of these conditions are benign in nature. For instance, Germany had 81.4% of hysterectomies performed for treating benign diseases of female genital organs. 4

Hysterectomy artificially ends the reproductive function and has several positive and negative effects on women’s physical and psychosocial health. It may provide immediate relief from dysfunctional uterine bleeding and pelvic pain or discomfort. The operation rates the highest in satisfaction scores compared with other treatments as it improves the quality of life, 5 and reduces anxiety and depression.6,7 On the contrary, hysterectomy’s adverse effects include urinary tract infections, urinary incontinence, 8 sexual dysfunctions, depression, increased fatigue,9,10 obesity, 11 osteoporosis, 12 coronary heart disease 13 and loss of feminity. 14

Around the globe, the incidence of hysterectomy operation differs significantly between and within countries. The available research on the occurrence of hysterectomy varies within the setting, sample population and methodologies; it makes the global comparison challenging. Nevertheless, these studies reported that the hysterectomy rate is much higher in the developed world than in the developing world. 15 Recently, studies showed a decline in hysterectomy rates in many developed countries. The availability of less invasive alternatives such as second-generation endometrial ablative devices, levonorgestrel intrauterine systems and uterine arterial embolization are possible reasons. 5 In addition, variations in the incidence of hysterectomy are associated with several other characteristics such as race, education, socio-economic and insurance status, change in uterine pathology, gender, training of healthcare providers,16–18 age at menarche and parity. 19

Research on the issue from a population setting is limited in developing countries, especially India, and is primarily based on small or area-specific samples. The country’s hysterectomy prevalence varies between 1.7% and 9.8%,15,20,21 and numerous are conducted in the early years of life. 22 Unnecessary hysterectomies are being conducted among rural and poor women owing to factors such as fear instigated by medical professionals, solution for menstrual problems and related taboos, failure of appropriate gynaecological care, practical difficulties in living with reproductive health problems, belief that hysterectomy is the best treatment, inappropriate use of insurance22–24 and fading employment opportunities. 25 A study from Maharashtra, India, revealed that the problem is much deep-rooted, as hysterectomies have become the norm in a district, where cane-cutting contractors are unwilling to hire menstruating women, leading to wombless villages. 25 The issue highlights the fact that women are compelled to ‘earn and care for their families’; hence, they balance their medical options with social responsibility. 26

Recently, a series of media reports highlighted an unusual surge in the number of hysterectomy operations across several parts of the country. These operations were performed as a routine treatment of gynaecological ailments, particularly among young and pre-menopausal women.23,27,28 These reports raised suspicions about deceitful practices by healthcare providers in the private sector for profit reasons. 21 A study from Andhra Pradesh highlights that nearly 60% of hysterectomies were conducted on women aged under 30, and 95% of them were performed in private hospitals. 29 The discharge summaries of these operations were incomplete and with no information of the procedure and follow-up advice. 29 In this way, mediation for the use of medicine was enacted in the sphere of self-convenience, family, family values, work and health problems, along with doctor–patient interactions.

Although these findings were significant in nature, comprehensive assessment of hysterectomy prevalence and its correlation were missing at the national level. The concerns mentioned earlier and a dearth of data, in the recent past, hysterectomy has gained attention in Indian health policy debates, which triggered the focus on the issue.27,28 This emphasis forced the government to include a set of questions on hysterectomy operation in the National Family Health Survey (NFHS).23,28 Given the availability of nationally representative data on hysterectomy in India, this article aims to map the prevalence of hysterectomy across Indian states and districts, and identify its geospatial correlation. It also wants to examine the socio-economic and demographic determinants of hysterectomy using the fourth round of the NFHS (NFHS-IV).

Methods

Data and sample

The NFHS, popularly known as the ‘Demographic Health Survey’ (DHS) globally, is a large-scale, cross-sectional and multi-round survey. It is executed regularly to obtain population-based estimates of significant health concerns, risk behaviours and nutrition. The International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai with technical assistance of ICF International, USA conducted the NFHS-IV in India during 2015–2016. NFHS-IV, the fourth in the NFHS series, was designed to provide estimates on majority indicators at the national, state/union territory and district levels. The information on selected variables such as sexual behaviour, occupation and domestic violence is available at the state level (state module) only. For the first time, round four of the survey provided information on hysterectomy operations across the country, especially at the district level.

The NFHS-IV sample was selected via a stratified two-stage sampling design in rural and urban areas across 36 states/union territories in India. The 2011 Census served as the sampling frame for the selection of primary sampling units (PSUs). PSUs were the villages in rural areas, while in urban areas, they were Census Enumeration Blocks (CEBs). The first stage involved the selection of PSUs with probability proportional to size (PPS) sampling. In every selected rural and urban PSU, a complete household mapping and listing operation were carried out, followed by PSU segmentation, in case, selected PSU had at least 300 households. Hence, an NFHS-IV cluster is either a PSU or a segment of a PSU. The second stage involved a systematic selection of 22 households in each PSU. The separate estimates for slum and non-slum areas in eight cities (Chennai, Delhi, Hyderabad, Indore, Kolkata, Meerut, Mumbai and Nagpur) can be calculated from the NFHS-IV sample. In the survey, sampling weights were derived from sampling probabilities separately for each sampling stage and each cluster; for more details, please refer to NFHS report. The survey covered 601,509 sampled households and 699,686 women (ever-married or never-married) aged 15–49 years with a 97% response rate. We used a weighted sample of 699,405 women and 517,030 ever-married women for the analysis after removing missing information/discrepancies.

Outcome variable

The survey asked four questions related to hysterectomy to women aged 15–49 years: (1) whether the woman has undergone operation related to the removal of the uterus; (2) how many years ago this operation (hysterectomy) was performed; (3) place of operation and (4) reasons for the operation. The article used hysterectomy operation as an outcome variable (0 = no operation, 1 = yes). The analysis also used the information such as the place of hysterectomy operation and reasons for the operation.

Covariates

Several socio-economic, demographic characteristics of the respondents were used as covariates; all of them were categorical. The selected variables are the prominent determinates of women’s reproductive health in India. Sterilization 21 and insurance 30 were chosen based on a literature review. We included the following variables as covariates in the statistical models: level of education (no education, primary, secondary and higher education), place of residence (rural and urban), religion (Hindu, Muslim and others), caste (scheduled caste – SC /scheduled tribe – ST, other backward caste – OBC and others) and wealth index (poorest, poorer, middle, richer and richest). The respondents’ age was divided into three 10-year intervals starting with age 20. As some younger women also underwent hysterectomy before the age of 20, the age group 15–19 years was clubbed in the first 10-year age interval. Finally, the age groups were 15–29, 30–39 and 40–49 years. The other variables considered in the statistical models include age at marriage (< 20 years, 20–30 years, >30 years), parity (no children, first, second and three or more), use of sterilization (no, yes) and insurance coverage (no, yes). Occupation of the respondent (not working, working as professional and in the clerical job, sales, agriculture, service and production) was also considered in the bivariate analysis because of its emerging association with hysterectomy. 23

Statistical models

The article used descriptive statistics, multivariate logistic regression, multilevel regression and geospatial analysis to assess the objectives. For spatial and bivariate analysis, the sample included both never-married women (not yet married) and ever-married women (currently married, divorced, widowed and no longer living together/separated; N = 699,405); however, for multivariate and multilevel regression analyses, only ever-married sample was considered because of inclusion of covariates that is, parity and age at marriage (N = 517,030). As the data on occupation are available only for subsample at the state level, we did not consider it in multilevel analysis.

District level georeferenced map of India, obtained from Census of India, was used to present the prevalence of hysterectomy. To inspect the spatial dependency and clustering of hysterectomy across districts, Moran’s I, LISA (Univariate Local indicators of Spatial Association) cluster maps and significance maps were prepared. The spatial weight matrix (w) of order 1 was created using the Queen’s contiguity method. It measured the spatial proximity between each potential pair of observational entities in the dataset. We generated cluster and significant maps using the LISA functions in the Geo-Da environment. The map identified those locations with a significant local Moran’s I statistic classified by the type of spatial autocorrelation. The red colour in the map represents the hot-spots, deep blue represents the cold-spots and the light blue and light red colour represent the spatial outliers. The following four types of spatial autocorrelation were generated based on the LISA cluster:

Hot-spots: (high-to-high) regions with high value, with the similar neighbourhood.

Cold-spots: (low-to-low) regions with low values, with the similar neighbourhood.

Spatial outliers: (high-to-low) regions with high value but the low value in neighbourhood.

Spatial outliers: (low-to-high) regions with low value but the high value in neighbourhood.

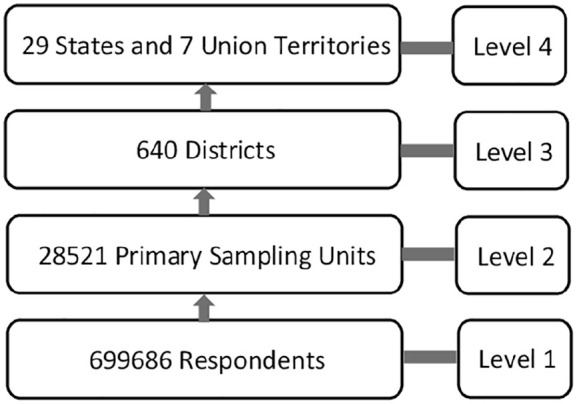

Furthermore, multilevel modelling was used for portioning the variation in the prevalence of hysterectomy at different geographical levels. Our data had four levels of hierarchical structure with individuals at level 1, PSUs at level 2, districts at level 3 and states/union territories at level 4 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Levels in multilevel analysis.

To decompose the variation in the prevalence of hysterectomy, we specified a series of four-level random intercept logistic models for the probability of an individual ‘i’ in PSU ‘j’, district ‘k’ and state ‘l’ to have a hysterectomy (Yijkl = 1) as

This model estimated the log-odds (πijkl) adjusted for a vector ( ) of the above-mentioned independent variables measured at the individual level. The parameter β0 represented the log-odds of having a hysterectomy for individuals belonging to the categorical variables’ reference category. The random effect inside the brackets was interpreted as a residual differential for the state l (f0l), district k (v0kl) and PSU j (u0jkl). All three residuals were assumed to be independent and normally distributed with mean 0 and variance σ2f0, σ2v0, and σ2u0. This variance quantified between states (σ2f0), between district (σ2v0) and between PSU (σ2u0), respectively, in the log-odds of women undergoing a hysterectomy for all background characteristics. For binary outcome, the variance at the lowest level could not be obtained directly from the model. The remaining variance was assumed to simplify the function of the binomial distribution. Based on the variance estimate of random effects, the proportion of variation in the log-odds of having a hysterectomy attributable to each level, also known as variance partition coefficient (VPC), was calculated. For example, the proportion of total variation in having a hysterectomy (in log-odds scale) attributable to an individual level could be obtained by dividing the between-individual variation by the total variation. Total variation was calculated using the latent variable method approach and treated the between-individual variation as having a standard logistic distribution variance approximated as π2/3 = 3.29. Hence, VPC for any level z could be calculated using the following formula

It allowed evaluating the changes in variance estimate and proportion of variation attributable to the higher levels when only one geographical level was considered at a time.

The dependent variable and the covariates were tested for possible multi-collinearity using the variance inflation factor (VIF) before considering in the statistical models. The VIF values obtained in this article ranged between 1.03 and 1.78, which were much lower than the permissible limits suggested by statisticians; 31 hence, multi-collinearity does not exist among variables.

Data had been analysed and presented using three software, that is, STATA 14.2 (analysis), Arc-GIS (prevalence maps) and Geo-Da (spatial and cluster maps).

Ethical approval

This study utilized the NFHS 2015–2016 (NFHS-IV), a publicly available dataset with no identifiable information on the survey participants. The dataset can be downloaded from the Demographic and Health Surveys website. Ethical approval for the original study NFHS-IV was obtained from the IIPS Ethical Review Board (No. IRB/NFHS-4/01_1/2015) and informed consent was taken from respondents before the interview.

As this study uses anonymized records and datasets that already exist in the public domain, additional ethical approval and informed consent were not sought.

Results

Distribution of hysterectomy in India, states and districts

Table 1 presents the prevalence of hysterectomy by states and regions of India for women aged 15–49 years. The prevalence of hysterectomy operation in India was 3.2%. Rural India had a higher prevalence of hysterectomy operation (3.4%) than urban India (2.7%). Around 5% of women from southern parts of India reported having hysterectomy, followed by 3.3% from eastern India, 3.1% from western India, 2.4% in central India and 2.1% in northern India. All regions except the northeast followed the similar rural–urban pattern as the country. The rural parts of northeast India had low hysterectomy prevalence than urban regions. The difference between rural and urban hysterectomy rates was the widest in western India (4.1% point). The state of Andhra Pradesh had the highest prevalence of hysterectomy cases (8.9%), followed by Telangana (7.7%), Bihar (5.4%), Gujarat (4.2%) and Dadra & Nagar Haveli (3.6%). The prevalence of hysterectomy was the lowest in the states/union territories of Lakshadweep (0.9%), Assam (0.9%), Mizoram (1%), Delhi (1.1%) and Meghalaya (1.1%). Approximately two-thirds of hysterectomies were conducted in private hospitals; all states/union territories followed the same pattern except northeast states, Himachal Pradesh, Odisha, Chandigarh and Puducherry, where the use of the public facility was more. The causes of hysterectomy in the country were excessive menstrual bleeding (45.8%), fibroids/cysts (17.6%), uterine disorders (12.7%), uterine prolapse (7.6%) and other causes (16.2%) (table not provided).

Table 1.

Prevalence of hysterectomy by place of residence and percentage distribution of women aged 15–49 years by place of hysterectomy (healthcare facility), India and states, NFHS-IV (2015–2016).

| State/Union Territory | Prevalence of hysterectomy | Percentage distribution of women by place of hysterectomy | Number of women | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Place of residence | ||||||

| Rural | Urban | Public | Private | NGOs | |||

| India | 3.2 | 3.4 | 2.7 | 32.3 | 66.8 | 0.9 | 699,686 |

| North | 2.1 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 38.6 | 60.5 | 0.9 | 95,012 |

| Chandigarh | 1.5 | 0.0 | 1.6 | 54.3 | 45.7 | 0.0 | 573 |

| Delhi | 1.1 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 41.3 | 57.7 | 1.0 | 10,536 |

| Haryana | 1.9 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 45.9 | 52.0 | 2.1 | 15,583 |

| Himachal Pradesh | 2.2 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 62.5 | 37.2 | 0.3 | 3842 |

| Jammu & Kashmir | 2.6 | 1.9 | 1.1 | 35.8 | 62.6 | 1.5 | 6809 |

| Punjab | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 35.2 | 63.2 | 1.6 | 15,212 |

| Rajasthan | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 33.8 | 65.8 | 0.4 | 36,529 |

| Uttarakhand | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 38.8 | 60.5 | 0.7 | 5928 |

| Central | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 30.9 | 68.4 | 0.6 | 165,322 |

| Chhattisgarh | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 35.0 | 64.5 | 0.5 | 16,502 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 3.0 | 3.1 | 2.8 | 44.2 | 55.2 | 0.6 | 43,729 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 2.2 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 23.0 | 76.4 | 0.7 | 105,092 |

| East | 3.3 | 3.5 | 2.8 | 31.1 | 67.4 | 1.4 | 154,503 |

| Bihar | 5.4 | 5.4 | 5.2 | 17.8 | 80.8 | 1.4 | 56,254 |

| Jharkhand | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.6 | 27.1 | 71.6 | 1.4 | 17,596 |

| Odisha | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 71.4 | 28.4 | 0.2 | 24,929 |

| West Bengal | 2.0 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 49.2 | 48.6 | 2.2 | 55,723 |

| Northeast | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 61.7 | 36.8 | 1.6 | 24,583 |

| Arunachal Pradesh | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 70.4 | 28.1 | 1.5 | 599 |

| Assam | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 65.7 | 33.3 | 1.0 | 17,303 |

| Manipur | 1.6 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 52.3 | 46.0 | 1.8 | 1222 |

| Meghalaya | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 71.4 | 28.6 | 0.0 | 1587 |

| Mizoram | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 62.9 | 36.0 | 1.2 | 584 |

| Nagaland | 1.6 | 1.2 | 2.1 | 49.0 | 50.3 | 0.8 | 798 |

| Sikkim | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.6 | 55.0 | 45.0 | 0.0 | 319 |

| Tripura | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 41.5 | 52.5 | 6.1 | 2172 |

| West | 3.1 | 6.7 | 2.6 | 30.8 | 67.7 | 1.4 | 100,433 |

| Dadra and Nagar Haveli | 3.6 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 61.0 | 39.0 | 0.0 | 171 |

| Daman and Diu | 3.0 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 25.6 | 74.4 | 0.0 | 91 |

| Goa | 2.6 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 44.3 | 55.7 | 0.0 | 861 |

| Gujarat | 4.2 | 4.4 | 4.0 | 30.6 | 66.9 | 2.6 | 32,670 |

| Maharashtra | 2.6 | 3.2 | 2.0 | 30.8 | 68.7 | 0.6 | 66,639 |

| South | 4.8 | 7.3 | 3.7 | 31.7 | 67.8 | 0.6 | 159,553 |

| Andaman and Nicobar Islands | 1.8 | 1.3 | 2.5 | 24.1 | 75.9 | 0.0 | 231 |

| Andhra Pradesh | 8.9 | 9.7 | 7.3 | 16.7 | 82.8 | 0.5 | 30,410 |

| Karnataka | 3.0 | 3.7 | 2.1 | 52.8 | 46.9 | 0.3 | 34,867 |

| Kerala | 1.8 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 41.6 | 58.1 | 0.2 | 19,267 |

| Lakshadweep | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 20.7 | 79.3 | 0.0 | 43 |

| Puducherry | 1.7 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 68.2 | 31.8 | 0.0 | 793 |

| Tamil Nadu | 3.4 | 3.5 | 3.4 | 52.4 | 46.6 | 1.0 | 51,570 |

| Telangana | 7.7 | 10.3 | 5.0 | 18.8 | 80.8 | 0.5 | 22,371 |

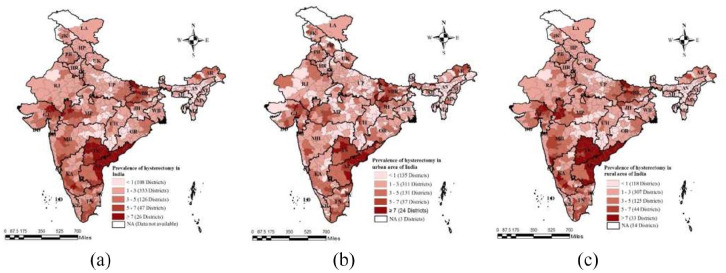

Figure 2(a)–(c) depict the district-wise prevalence of hysterectomy in India (total, urban and rural). The darker shade represents high while the light shade presents low hysterectomy prevalence in India’s districts. One hundred and eight districts had less than 1% prevalence of hysterectomy and 333 districts had 1%–3% prevalence. Hysterectomy prevalence ranged between 3% and 5% in 126 districts, 5% and 7% in 47 districts and more than 7% in 26 districts (Figure 2(a)). Warangal district of Telangana (15.9%) had the highest prevalence of hysterectomy operations followed by Guntur district of Andhra Pradesh (15.7%), Nizamabad district of Telangana (14.4%), Krishna (13.5%) and West Godavari (12.8%) districts of Andhra Pradesh, East Champaran from Bihar (12%) and Karimnagar of Telangana (11.4%); this information is based on the data plotted in Figure 2(a). The prevalence of hysterectomy was the highest in both rural and urban areas of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana states. Few districts of Bihar, Gujarat and rural Karnataka also had a high rate of hysterectomy. The higher number of districts marked in a darker shade in the map of rural India (Figure 2(c)) than urban India (Figure 2(b)) indicated that many rural districts in India had a high prevalence of hysterectomy operations than urban India.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of hysterectomy among women aged 15–49 years in the districts of India, NFHS-IV (2015–2016): (a) total, (b) urban and (c) rural.

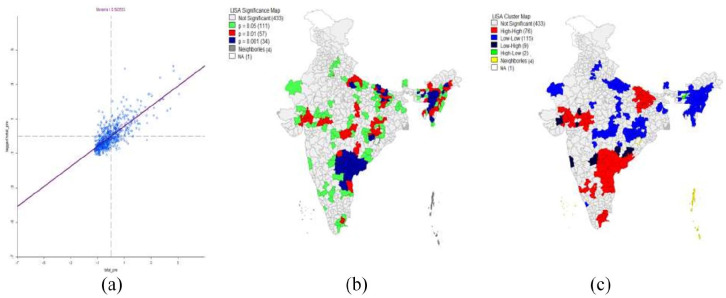

A spatial analysis was carried out to see the clustering of hysterectomy operations across the country. Figure 3(a)–(c) present the Moran’s I (concentration graph) and LISA (a local indicators of spatial association) significance and cluster maps of hysterectomy at the district level. The value of Moran’s I, that is, 0.58, suggested the measure of spatial dependence and correlation of the prevalence of hysterectomy among districts (Figure 3(a)). Spatial analysis through Moran’s I informed about the geographical autocorrelation in hysterectomy prevalence among districts. The hot-spots (high to high) presented in red colour indicated that similar neighbouring districts surrounded the districts with high hysterectomy prevalence. Contrarily, cold-spots (low to low), given in blue colour, were districts with a lower hysterectomy level and had the same neighbourhood. The significance of LISA map (Figure 3(b)) indicates that 433 districts of India had no significant neighbourhood association, whereas 111, 57 and 34 districts were associated with 95%, 99% and 99.9% significance level respectively. The cluster LISA map (Figure 3(c)) portrays that the spatial association among 76 districts was high to high; these districts were highlighted as hot-spot districts of India for hysterectomy operation. Whereas 115 districts had low to low, nine districts had low to high and two districts had high to low spatial association.

Figure 3.

Moran’s I (concentration graph), LISA (local indicators of spatial association) significance and cluster map for prevalence of hysterectomy among women aged 15–49 years in districts of India, NFHS-IV (2015–2016): (a) concentration graph, (b) significance map and (c) cluster map.

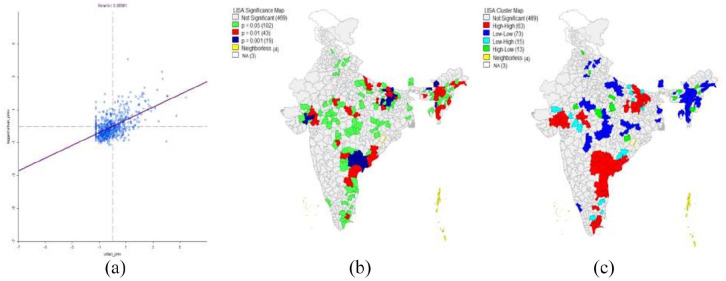

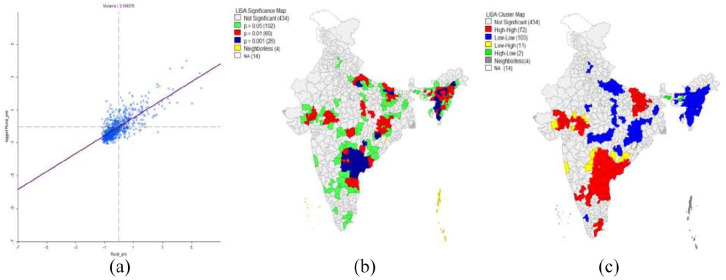

In urban India, the value of Moran’s I was 39% (Figure 4(a)); 469 districts had no significant neighbourhood association, 102 districts had an association with 95% significance level, 43 districts at 99% and 19 districts at 99.9% (Figure 4(b)). High to high association (hot-spots) was established in 63 districts, 73 had low to low association (cold-spots), 15 had low to high association and 13 had high to low association (Figure 4(c)). The value of Moran’s I for the rural area was 55% (Figure 5(a)), which shows that the rural areas had higher neighbourhood association compared to urban areas. In rural areas, 102, 60 and 60 districts had a neighbourhood association with 95%, 99% and 99.9% significance level, respectively (Figure 5(b)). A high to high (hot-spots) correlation existed among 72 districts of rural India, 103 districts had low to low association (cold-spots), 11 had low to high and 2 districts had high to low neighbourhood association on the prevalence of hysterectomy (Figure 5(c)).

Figure 4.

Moran’s I (concentration graph), LISA (local indicators of spatial association) significance and cluster map for prevalence of hysterectomy among women aged 15–49 years in urban areas of districts, India, NFHS-IV (2015–2016): (a) concentration graph, (b) significance map and (c) cluster map.

Figure 5.

Moran’s I (concentration graph), LISA (local indicators of spatial association) significance and cluster map for prevalence of hysterectomy among women aged 15–49 years in rural areas of districts, India, NFHS-IV (2015–2016): (a) concentration graph, (b) significance map and (c) cluster map.

Determinants of hysterectomy

Percentage of women with hysterectomy by selected background characteristics is presented in Table 2. Women aged 40–49 years had a high prevalence of hysterectomy (9.3%) than women in age groups 30–39 years (3.6%) and 15–29 years (0.4%). With the increase in education, the prevalence of hysterectomy decreased. Nearly 6% of women with no education had hysterectomy than 1% women with higher education. The prevalence of hysterectomy varied according to caste and religion groups. A higher proportion of Hindu women (3.4%) underwent hysterectomy than women from Muslim religion (2.2%). In addition, 3.6% of women from OBC, 3.1% women from other caste and 2.7% from SC/ST underwent a hysterectomy. Women who were engaged in any wage-related work had a higher prevalence of hysterectomy than women who were not working (2.8%). The prevalence of hysterectomy was higher among women who were engaged in the sales job, agriculture and service sector than women working in other areas. Nearly 4% of women from the middle wealth index (the highest among all) had hysterectomy than women from richer (3.5%) and the richest (3.1%) quintile. The prevalence of hysterectomy was high among women who got married before 20 years of age (4.5%) compared to women who married later. Results showed that with the increase in the number of pregnancies, the prevalence of hysterectomy increased. Prevalence among sterilized women was higher (5.2%) than non-sterilized women (3.4%). Insured women had approximately two times higher prevalence compared to non-insured women.

Table 2.

Percentage of women aged 15–49 years with hysterectomy by selected socio-economic and demographic characteristics, India, NFHS-IV (2015–2016).

| Characteristics | Prevalence | Number of women | Characteristics | Prevalence | Number of women |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residence | Occupation | ||||

| Urban | 2.7 | 242,296 | Not working | 2.8 | 85,322 |

| Rural | 3.4 | 457,390 | Professional and clerical | 2.5 | 4083 |

| Education | Sales | 5.9 | 1772 | ||

| No education | 5.8 | 192,156 | Agriculture | 5.4 | 17,916 |

| Primary | 4.3 | 87,215 | Service | 4.7 | 4174 |

| Secondary | 2.0 | 331,019 | Production | 3.1 | 7676 |

| Higher | 1.0 | 89,296 | Age at marriage (years) | ||

| Religion | Never-married | 0.0 | 159,015 | ||

| Hindu | 3.4 | 563,760 | <20 | 4.5 | 377,081 |

| Muslim | 2.2 | 96,450 | 20–30 | 2.4 | 138,087 |

| Other | 2.7 | 39,476 | >30 | 2.5 | 3654 |

| Caste/Tribe | Parity | ||||

| SC/ST | 2.7 | 205,976 | No children | 0.2 | 213,058 |

| OBC | 3.6 | 302,784 | First | 1.6 | 99,093 |

| Other | 3.1 | 161,624 | Second | 4.2 | 175,475 |

| Wealth index | Third or more | 6.0 | 212,059 | ||

| Poorest | 2.5 | 123,992 | Sterilization | ||

| Poorer | 3.1 | 136,880 | No | 3.4 | 342,773 |

| Middle | 3.6 | 143,841 | Yes | 5.2 | 190,657 |

| Richer | 3.5 | 148,020 | Insurance | ||

| Richest | 3.1 | 146,954 | No | 2.7 | 557,049 |

| Age (years) | Yes | 4.9 | 142,637 | ||

| 15–29 | 0.4 | 359,554 | |||

| 30–39 | 3.6 | 187,661 | |||

| 40–49 | 9.3 | 152,471 |

SC: scheduled caste; ST: scheduled tribe; OBC: other backward caste.

The multilevel modelling results portrayed that the variation partition coefficient for the hysterectomy attributed at four levels, that is, states, districts, PSUs and individuals (Table 3). After adjusting all individual-level socio-economic and demographic characteristics, PSUs accounted for the highest variation (0.12) in the hysterectomy, followed by states (0.07) and districts (0.06). The remaining variation had been attributed to socio-economic and demographic characteristics.

Table 3.

Multilevel analysis of ever-married women aged 15–49 years with hysterectomy by selected background characteristics, India, NFHS-IV (2015–2016).

| Background characteristics | Reference category | AOR of hysterectomy |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 30–39 | 15–29® | 5.51*** (5.13, 5.93) |

| 40–49 | 14.71*** (13.68, 15.81) | |

| Residence | ||

| Rural | Urban® | 1.22*** (1.16, 1.28) |

| Education completed | ||

| Primary | No education® | 0.98 (0.93, 1.03) |

| Secondary | 0.72*** (0.69, 0.75) | |

| Higher | 0.45*** (0.41, 0.49) | |

| Religion | ||

| Muslim | Hindu® | 0.71*** (0.66, 0.75) |

| Other | 0.92* (0.84, 1) | |

| Caste/Tribe | ||

| OBC | SC/ST® | 1.24*** (1.18, 1.29) |

| Other | 1.23*** (1.17, 1.29) | |

| Wealth Index | ||

| Poorer | Poorest® | 1.45*** (1.37, 1.54) |

| Middle | 1.83*** (1.72, 1.94) | |

| Richer | 2.22*** (2.08, 2.38) | |

| Richest | 2.67*** (2.47, 2.88) | |

| Parity | ||

| First | No Child® | 1.76***(1.54, 2.01) |

| Second | 2.74***(2.41, 3.1) | |

| Three or more | 2.74***(2.42, 3.11) | |

| Age at marriage (years) | ||

| 20–30 | <20 years® | 0.62***(0.59, 0.64) |

| >30 | 0.50***(0.41, 0.61) | |

| Sterilization | ||

| Yes | No® | 0.65***(0.63, 0.68) |

| Insurance | ||

| Yes | No® | 1.16***(1.11, 1.22) |

| Number of women | 517,030 | |

| Number of PSU | 28,521 | |

| Number of districts | 640 | |

| Number of states | 36 | |

| Variance PSU level | 0.43 | |

| VPC PSU level | 0.12 | |

| Variance district level | 0.24 | |

| VPC district level | 0.06 | |

| State-level variance | 0.28 | |

| VPC state level | 0.07 | |

| Dependent variable | Hysterectomy (0 ‘No’) (1 ‘Yes’) | |

AOR: adjusted odds ratio; OBC: other backward caste; SC: scheduled caste; ST: scheduled tribe; PSU: primary sampling unit; VPC: variance partition coefficient.

p < 0.1, ***p < 0.01.

Table 3 also presents the adjusted odds ratios (AORs) for each selected background characteristic. The chances of hysterectomy operation increased manifold with the increase in age after controlling all the characteristics. Women aged 40–49 years had nearly 15 times higher chances to undergo a hysterectomy than women in the age group 15–29 years. The odds for having a hysterectomy were 22% higher in rural areas than urban. Level of education was negatively associated with hysterectomy. Women with no education had 55% higher chances of having a hysterectomy than women with higher education. Women from the Muslim religion and SC/ST were less likely to undergo a hysterectomy than their counterparts. Compared to the poorest women, poorer, middle, richer and the richest women had AOR of 1.45, 1.83, 2.22 and 2.67, respectively, for hysterectomy. The ORs indicated that with an increase in wealth index, the chances of having hysterectomy increased. Age at marriage was negatively associated with hysterectomy. The odds of having a hysterectomy were high among parous women than nulliparous ones. Women who opted for sterilization had 35% lower chances to undergo hysterectomy than their counterparts. Insured women were 1.16 times more likely to have hysterectomy compared to non-insured women.

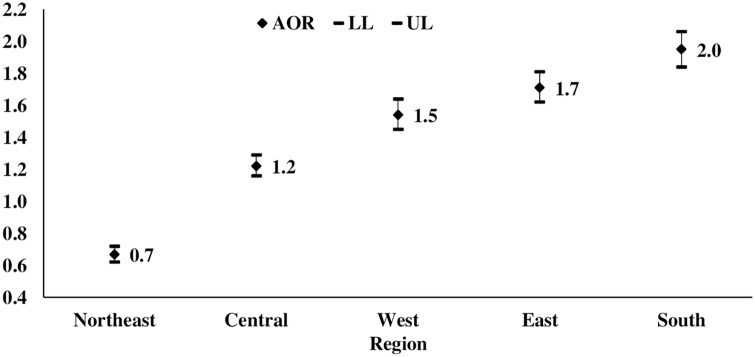

Furthermore, a logistic regression was executed to see geographical regions’ effect on hysterectomy (Figure 6). After adjusting all background characteristics, except India’s northeast region, women from all other regions had a higher probability of undergoing hysterectomy than the northern region. The OR was the highest in southern India (AOR: 1.8) followed by the eastern region (AOR: 1.7), western region (AOR: 1.5) and central region (AOR: 1.3) compared to the northern region of India.

Figure 6.

Adjusted odds ratio of women aged 15–49 years, who had a hysterectomy by regions of India, NFHS-IV (2015–2016).

Note: adjusted for age, place of residence, education, religion, caste/tribe, wealth index, parity, age at marriage, sterilization and insurance.

Discussion

According to studies, hysterectomy operations are primarily performed for benign indications such as excessive menstrual bleeding, fibroids/cysts, uterine disorder and uterine prolapse in India.20,32 L reported that some of these operations were lifesaving, some were only meant for treating nonfatal but severe conditions and some are unnecessary. 33 It indicated that many of these causes were considered to be treatable and surgery could be avoided. The studies conducted on hysterectomy operation in India are primarily micron in nature, and many of them have been undertaken in hospital-based settings. NFHS-IV, for the first time, provided data on hysterectomy across the country. Hence, this article aimed to understand the spread of hysterectomy prevalence among India’s district, spatial correlation and factors associated with its prevalence.

The findings of this article revealed that the prevalence of hysterectomy operations in India was 3.2% among women aged 15–49 years. This was considerably lower than high-income countries such as the United States (26.4%), 34 Australia (22%) 35 and Singapore (7.5%). 36 This wide variation may be the result of methodological differences and selection of age groups. The prevalence in the states ranged from 9 to 89 per 1000 women. The southern states like Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, Bihar and Gujarat were the hot-spots of hysterectomy, while the northeast states had the least prevalence. There were around 47 districts across India, where hysterectomy prevalence ranged between 5% and 7%. Other 26 districts were the most affected ones, having a prevalence of more than 7%. For example, Warangal district of Telangana had the highest prevalence of hysterectomy operations, followed by Guntur district of Andhra Pradesh, Nizamabad district of Telangana, Krishna and West Godavari districts of Andhra Pradesh. Media reports and community-based studies had highlighted that Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Gujarat and Bihar performed the highest level of hysterectomy operations21,27,29 and also, the prevalence was increasing day by day.27,28

This article established a clear spatial pattern of hysterectomy operation among the districts of India. Although the presence of hysterectomy was universal across India, however, as expected, the clustering was higher in the districts of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Bihar and Gujarat. Nearly 202 districts showed significant nearest-neighbourhood association for hysterectomy operation; such clustering was found to be more prominent in rural India than urban. The variation partition coefficient attributed the prevalence of hysterectomy at four levels, that is, state, district, PSU and individual. After adjusting all individual-level characteristics, PSUs had the highest contextual effect on the hysterectomy prevalence, followed by states and districts, respectively. This suggested that the factors at micro political units, rather than states and districts, might contribute significantly to the prevalence of hysterectomy in various parts of the country.

There had been an intense debate on the occurrence of coerced hysterectomies in India, as many of these operations seemed to be unnecessary and unwarranted. 26 Most of the hysterectomy operations were done at private hospitals. 29 Some argued that the medical community itself promoted the surgery to earn profit in private sectors or skill-building in public sector doctors. 26 The result of this article too found that most of the hysterectomy operations were conducted in private hospitals compared to government hospitals in most states/union territories. Interestingly, rural India was having a higher prevalence of hysterectomy operations in the private sector than urban India. The finding highlighted that women may be pushed for hysterectomy operation by the private sector to earn more money, especially in the villages. A study from Andhra Pradesh revealed that poor rural women even as young as 20 years were advised to have hysterectomy even for routine gynaecological issues, such as abdominal pain and white discharge by healthcare providers often to gain profit without offering any alternatives. 37 A national daily termed such service providers as ‘the uterus snatchers of Andhra Pradesh’. 37

The prevalence of unwarranted hysterectomy operation may further seem to be correlated with profit incentives under the national health insurance scheme and unregulated private healthcare.26,30 The findings from our analysis affirmed that the chance of undergoing a hysterectomy increased significantly if a woman was enrolled under insurance. Therefore, insurance coverage might have played a decisive role in increasing the prevalence of hysterectomy.21,26,37 In Andhra Pradesh (Telangana included), Bihar, Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan, primarily the poor people were forced to avail free surgeries supported by insurance schemes, which led to the intervention of police and court. 37 In response to such findings, few states in India restricted publicly funded insurance coverage for hysterectomy in private facilities.26,38

A study conducted in the state of Gujarat in India found that removal of uterus and ovaries was generally beneficial and protected women from various health problems. 39 Women, their family members and medical providers treated hysterectomy as an everyday event. 2 Among rural Indian women with completed family size, chances of hysterectomy were high, 39 indicating that hysterectomy might be also used as a family planning method. In our article, though the prevalence of hysterectomy was high among sterilized women, multilevel analysis results indicated that sterilized women had less probability of having a hysterectomy. This finding may support the view that women, who were not using sterilization, may use hysterectomy as a contraceptive method. However, other studies showed positive association between hysterectomy and sterilization, as tubal ligation has been associated with higher risk of menstrual disorders and gynaecological problems. 21

Hysterectomy had border socio-economic, demographic and medical phenomenon. It was found to be associated with a woman’s life circumstances, family, power relationship, economic inequalities and health status. 21 Our study indicated the wide variation in the hysterectomy operation by various socio-economic and demographic characteristics such as place of residence, occupation, education, wealth index, age, parity and age at marriage. Notably, women with no education or less education and from rural areas had higher chances of hysterectomy. Many other research studies supported this finding.19,37 On the contrary, wealth index had a positive association with hysterectomy prevalence after controlling various background characteristics in our study. In contrast, many other studies indicated that the increase in income reduced the chance of hysterectomy.22,39 Several other studies found age, 40 parity 19 and empowerment 20 to affected hysterectomy positively.

The article’s significant contribution was the spatial analysis that approved the geographical clustering of the hysterectomy operation at the district level and a significant neighbourhood association. It also highlighted the high prevalence of hysterectomy in some of the states and districts and significant determinants.

In India, though Draft National Policy for Women recognized the shortage of services for menopausal women, health policies primarily target the women who are either procreating or in their old age. 41 Understanding that the uterus requires care beyond childbirth and has a function within the human body that is not limited to mere reproduction, seems to be lacking among women too, 22 especially less educated. This emphasizes a need to take the holistic and the life cycle approach to address health concerns and improve women’s health status. Need also exists to provide counselling and educate women about their reproductive rights and informed choice and promote access to sexual and reproductive health services. To eliminate unwarranted hysterectomies, surveillance and medical audits can be of great help.

In addition, to serve the cause, the government can design better health protection plans and promote the health insurance schemes’ judicial use. The results from this article support the fact that the chances of hysterectomy increase many-fold if women are enrolled in health insurance. Finally, to understand the interplay of factors at various levels, there is a need to conduct in-depth studies on the epidemiology of hysterectomy in general and specifically in the states/districts with a high prevalence of operation.

Limitation of the study

Self-reported information on hysterectomy may not be sufficient to understand the actual prevalence of hysterectomy. In addition, data on oophorectomy, total hysterectomy or partial hysterectomy had not been collected. The only question asked to women was ‘Some women undergo an operation to remove the uterus, have you undergone such operation?’ apart from questions on place, reason and age at hysterectomy. The data had been collected only for reproductive age group 15–49 years.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Dipti Govil  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0599-0045

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0599-0045

References

- 1. Hammer A, Rositch AF, Kahlert J, et al. Global epidemiology of hysterectomy: possible impact on gynecological cancer rates. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015; 213(1): 23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Parker WH. Bilateral oophorectomy versus ovarian conservation: effects on long-term women's health. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2010; 17(2): 161–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gor HB. Hysterectomy: background, history of the procedure, problem, https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/267273-overview (2018, accessed 13 August 2019).

- 4. Stang A, Merrill RM, Kuss O. Hysterectomy in Germany: a DRG-based nationwide analysis, 2005–2006. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2011; 108(30): 508–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gupta S, Manyonda I. Hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Current Obstetric Gynaecol 2006; 16(3): 147–153. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carlson KJ. Outcomes of hysterectomy. Clin Obstetric Gynecol 1997; 40(4): 939–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Uzun R, Savaş A, Ertunç D, et al. The effect of abdominal hysterectomy performed for uterine leiomyoma on quality of life. Turkiye Klinikleri J Gynecol Obstetric 2009; 19(1): 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Link CL, Pulliam SJ, McKinlay JB. Hysterectomies and urologic symptoms: results from the Boston area community health (BACH) survey. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 2010; 16(1): 37–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Goktas SB, Gun I, Yildiz T, et al. The effect of total hysterectomy on sexual function and depression. Pak J Med Sci 2015; 31(3): 700–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Richards DH. A post-hysterectomy syndrome. Lancet 1974; 304(7887): 983–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kirchengast S, Gruber D, Sator M, et al. Hysterectomy is associated with postmenopausal body composition characteristics. J Biosoc Sci 2000; 32(1): 37–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Choi HG, Jung YJ, Lee SW. Increased risk of osteoporosis with hysterectomy: a longitudinal follow-up study using a national sample cohort. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019; 220(6): 573.e1–573.e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ding DC, Tsai IJ, Hsu CY, et al. Hysterectomy is associated with higher risk of coronary artery disease: a nationwide retrospective cohort study in Taiwan. Medicine 2018; 97(16): e0421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Silva Cde M, Vargens OM. Woman experiencing gynecologic surgery: coping with the changes imposed by surgery. Revista Latino-americana De Enfermagem 2016; 24: e2780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Desai S, Campbell OM, Sinha T, et al. Incidence and determinants of hysterectomy in a low-income setting in Gujarat, India. Health Policy Plan 2017; 32(1): 68–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brummitt K, Harmanli OH, Gaughan J, et al. Gynecologists’ attitudes toward hysterectomy: is the sex of the clinician a factor. J Reprod Med 2006; 51(1): 21–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Materia E, Rossi L, Spadea T, et al. Hysterectomy and socioeconomic position in Rome, Italy. J Epidemiol Commun Health 2002; 56(6): 461–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Einarsson JI, Matteson KA, Schulkin J, et al. Minimally invasive hysterectomies—a survey on attitudes and barriers among practicing gynecologists. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2010; 17(2): 167–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cooper R, Hardy R, Kuh D. Timing of menarche, childbearing and hysterectomy risk. Maturitas 2008; 61(4): 317–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shekhar C, Paswan B, Singh A. Prevalence, sociodemographic determinants and self-reported reasons for hysterectomy in India. Reproduct Health 2019; 16(1): 118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Prusty RK, Choithani C, Gupta SD. Predictors of hysterectomy among married women 15–49 years in India. Reproduct Health 2018; J15(1): 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kameswari S, Vinjamuri P. Medical ethics in the Health Sector: a case study of hysterectomy in Andhra Pradesh. Hyderabad: National Institute of Nutrition. Life HRG. https://signalsinthefog.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/hysterectomy-ethics-in-s-t-for-setdev-final-1.pdf. (2010, accessed 10 October 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 23. Prayas. Understanding the reason for rising number of hysterectomies in India: national consultation. Jaipur: Prayas, http://www.prayaschittor.org/pdf/Hysterectomy-report.pdf. (2013, accessed 25 October 2019).

- 24. Sardeshpande N. Why do young women accept hysterectomy? Findings from a study in Maharashtra, India. Int J Innov Appl Stud 2014; 8(2): 579. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jadhav R. Why many women in Maharashtra’s Beed district have no wombs. The Hindu Business Line, 8 April 2019. https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/economy/agri-business/why-half-the-women-inmaharashtras-beed-district-have-no-wombs/article26773974.ece. (2019, accessed 13 October 2019).

- 26. Desai S. Pragmatic prevention, permanent solution: Women's experiences with hysterectomy in rural India. Soc Sci Med 2016; 151: 11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McGivering J. The Indian women pushed into hysterectomies. The British Broadcasting Corporation, https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-21297606 (2013, accessed 5 September 2016).

- 28. Dar A. Demand to include hysterectomies in National Family Health Survey. The Hindu, August 19, https://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tpnational/demand-to-include-hysterectomies-in-national-family-healthsurvey/article5036626.ece (2013, accessed 13 October 2019).

- 29. Kameswari S, Vinjamuri P. Case study on unindicated hysterectomies in Andhra Pradesh. Life-Health Reinforcement group. National Consultation on Understanding the Reasons for Rising Hysterectomies in India. 12 August, http://www.prayaschittor.org/pdf/Hysterectomy-report.pdf (2013, accessed 22 February 2021).

- 30. Singh S. 16,000 ‘illegal’ hysterectomies done in Bihar for insurance benefit. Indian Express, 27 August, https://indianexpress.com/article/news-archive/web/16-000-illegal-hysterectomies-done-in-bihar-for-insurance-benefit/ (2012, accessed 16 September 2019).

- 31. Hair JF, Anderson RE, Babin BJ, et al. Multivariate data analysis: a global perspective. Vol. 7. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Radha K, Devi GP, Chandrasekharan PA, et al. Epidemiology of hysterectomy-a cross sectional study among Piligrims of Tirumala. IOSR J Dent Med Sci 2015; 1(14): 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Llamas M. Hysterectomy: removal of the uterus. drugwatch, 21 April, https://www.drugwatch.com/transvaginal-mesh/hysterectomy/ (2021, accessed 27 May 2021).

- 34. Erekson EA, Weitzen S, Sung VW, et al. Socioeconomic indicators and hysterectomy status in the United States, 2004. J Reprod Med 2009; 54(9): 553–558. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Byles JE, Mishra G, Schofield M. Factors associated with hysterectomy among women in Australia. Health Place 2000; 6(4): 301–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lam JS, Tay WT, Aung T, et al. Female reproductive factors and major eye diseases in Asian women–the Singapore Malay Eye study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2014; 21(2): 92–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mamidi BB, Pulla V. Hysterectomies and violation of human rights: case study from India. Int J Social Work Human Serv Pract 2013; 1(1): 64–75. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Devulapalli R. Secret behind rash of hysterectomies out. Times of India, 28 September, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/hyderabad/Secret-behind-rash-ofhysterectomies-out/articleshow/16580758.cms (2012, accessed 5 November 2016).

- 39. Desai S. The effect of health education on women’s treatment-seeking behaviour: findings from a cluster randomised trial and an in-depth investigation of hysterectomy in Gujarat, India (Doctoral dissertation, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine), https://researchonline.lshtm.ac.uk/id/eprint/2228561/ (accessed 15 November 2019).

- 40. Desai S, Shukla A, Nambiar D, et al. Patterns of hysterectomy in India: a national and state-level analysis of the fourth national family health survey (2015–2016). BJOG 2019; 126(Suppl. 4): 72–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Government of India. National Policy for Women 2016: articulating a vision for empowering women (draft), Ministry of Women and Child Development (MoWCD), https://wcd.nic.in/sites/default/files/draft%20national%20policy%20for%20women%202016_0.pdf (2016, accessed 26 October 2019).