Abstract

Background:

Delirium is common in palliative care settings and is distressing for patients, their families and clinicians. To develop effective interventions, we need first to understand current delirium care in this setting.

Aim:

To understand patient, family, clinicians’ and volunteers’ experience of delirium and its care in palliative care contexts.

Design:

Qualitative systematic review and thematic synthesis (PROSPERO 2018 CRD42018102417).

Data sources:

The following databases were searched: CINAHL, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Embase, MEDLINE and PsycINFO (2000–2020) for qualitative studies exploring experiences of delirium or its care in specialist palliative care services. Study selection and quality appraisal were independently conducted by two reviewers.

Results:

A total of 21 papers describing 16 studies were included. In quality appraisal, trustworthiness (rigour of methods used) was assessed as high (n = 5), medium (n = 8) or low (n = 3). Three major themes were identified: interpretations of delirium and their influence on care; clinicians’ responses to the suffering of patients with delirium and the roles of the family in delirium care. Nursing staff and other clinicians had limited understanding of delirium as a medical condition with potentially modifiable causes. Practice focused on alleviating patient suffering through person-centred approaches, which could be challenging with delirious patients, and medication use. Treatment decisions were also influenced by the distress of family and clinicians and resource limitations. Family played vital roles in delirium care.

Conclusions:

Increased understanding of non-pharmacological approaches to delirium prevention and management, as well as support for clinicians and families, are important to enable patients’ multi-dimensional needs to be met.

Keywords: Delirium, palliative care, qualitative research, systematic review

What is already known about the topic?

Delirium is common in palliative care settings.

Delirium is distressing for patients, families and clinicians.

Palliative care specific interventions need to be developed.

What this paper adds?

The limited understanding of delirium of palliative care nurses and other clinicians contributes to a relatively dominant focus on symptom management, rather than prevention, early identification and modification of possible causes.

Person-centred care can help alleviate patient suffering but can be challenging to deliver for patients with delirium.

Use of medication is triggered not only by the aim to alleviate patient suffering, but also by family and clinicians’ distress and limited resources.

Implications for practice, theory or policy?

Opportunities for palliative care nurses and other clinicians to gain greater understanding of delirium, its prevention and management need to be developed.

Reflective learning opportunities and practical and emotional support for staff may support ethical treatment decision making and increased use of non-pharmacological interventions for delirium.

Family can play vital roles in delirium care and their support needs should be addressed.

Introduction

Delirium is a complex neurocognitive syndrome, with many underlying physiological causes. It presents with acute and fluctuating disturbances in attention, awareness and cognition 1 and includes hypoactive, hyperactive or mixed subtypes. 2 Delirium is common in palliative care inpatient settings,3,4 is associated with poor health outcomes 5 and is distressing for patients and their families.6,7

Despite its profound impact, there has been little research into non-pharmacological prevention and management of delirium in palliative care settings, and only a limited number of trials investigating its management with medication.8,9,10–13 Evidence and guidelines from other settings are useful, but the development of palliative care specific interventions to improve delirium care is needed. To inform clinical practice and the development of such interventions, a greater understanding of delirium experiences, care practices and the specific influences that shape them from the perspectives of all relevant stakeholders in the palliative care context is needed.

Current delirium best practice guidelines recommend: regular delirium screening; multicomponent interventions targeting modifiable delirium risk factors; assessment and treatment of underlying causes of delirium; non-pharmacological strategies to support patients and family involvement in care.14,15 There is strong evidence that multi-component interventions can prevent delirium in about a third of hospital inpatients. 16 Recent systematic reviews have found a lack of high quality evidence to support routine use of medication, including antipsychotics, for delirium.17,18 However, surveys of palliative care clinicians have identified that current practice is poorly aligned with current evidence and guidelines; there is a lack of routine screening for delirium19,20 and antipsychotics and benzodiazepines for delirium are more commonly used than by clinicians working in other specialties. 21

Qualitative studies with palliative care clinicians (doctors, nurses, health care assistants and allied health professionals) and volunteers can provide insights into their delirium care practice and how this aligns with, or differs from, practice in other settings, such as care of older people or general hospital settings. They also enable exploration of the influences that shape delirium care practices in the palliative care context. For example, interview studies with palliative care nurses identified limited recognition of delirium and variable understanding of its assessment and management.22,23 Wright et al.’s 24 qualitative review highlighted how delirium can challenge relationships between patients, families and clinicians and the central nature of these relationships with respect to end-of- life care. Understanding influences upon care is important in identifying practice strengths, what may need to change to improve delirium care and facilitators and barriers to this.

Learning about patients’ and their families’ experience of delirium is important to inform compassionate and supportive approaches to its care. Patients who have experienced delirium report fear, distress and difficulty communicating during the delirium episode. 6 Finucane et al.’s 7 review of families’ delirium experiences in palliative care highlighted the distress that it can cause as well as the important roles that family can play in identifying delirium, supporting and advocating for the patient.

The reviews conducted by Wright et al. 24 and Finucane et al. 7 provide valuable insights into aspects of delirium in palliative care settings, but no systematic review has yet been conducted that synthesises the qualitative evidence of the experiences of palliative care patients, their families, clinicians and volunteers. This is needed to inform clinical practice and the development of interventions to prevent and manage delirium. We conducted a qualitative systematic review and thematic synthesis in order to gain an understanding of patient, family, clinicians’ and volunteers’ experiences of delirium (all subtypes) and its care in palliative care contexts.

Methods

A qualitative systematic review and thematic synthesis was conducted. It is reported according to the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) guidelines (see Supplemental File 1). 25 The review protocol was registered in PROSPERO on 03.07.18 (CRD42018102417). 26

Search strategy and study selection

The search strategy was developed with a health sciences information specialist and used the framework: delirium AND [palliative care] AND [carers OR nurses/medical staff OR patients]OR delirium AND [palliative care] AND [qualitative]. The following databases were searched: CINAHL, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), Embase, MEDLINE and PsycINFO. Results were limited to English language papers from 2000 onwards. See supplemental File 2 for the complete database search strategy. The search was conducted on 27.03.17 and updated on 24.01.19 using the search and screening strategy fully outlined in this paper. A final update (05.05.20) was conducted using rapid methodology consistent with Datla et al. 27 (Single reviewer, one database (MEDLINE)).

Search results were screened in two stages: title and abstract and full text screening, using Covidence software. 28 Two reviewers independently screened each result (IF, AH, SB, JT, PG). Reviews identified by the database search were examined for relevant studies.

Eligible studies explored patients’, families’, clinicians’ or volunteers’ experience of delirium or its care in specialist palliative care services (hospices, hospital palliative care units, out-patient clinics, day services and liaison services). 29 Eligible study designs were peer-reviewed primary studies using qualitative data collection methods such as unstructured interviews, semi-structured interviews, focus groups, qualitative observation or questionnaires that included open-ended responses and qualitative analysis techniques e.g. thematic analysis, narrative analysis, grounded theory or content analysis.

Disagreements were resolved through discussion or by consulting a third reviewer. At full text stage, reviewers selected the reason for exclusion from a hierarchical list.

Quality appraisal

Quality of included studies was appraised using a systematic approach employed by Rees et al. 30 Two reviewers independently appraised each study and recorded their comments in relation to rigour in sampling, data collection and data analysis and the extent to which findings were supported by the data (IF appraised all studies and AH, JT and PG shared the role of second reviewer). They rated the trustworthiness of the findings as low, medium or high based upon these criteria. The usefulness of findings to the review was rated based upon the breadth and depth of study findings and the extent to which participants’ perspectives were privileged (i.e. explored and presented). Further details of the study quality appraisal criteria are available in Supplemental File 3. Consensus on ratings was reached by discussion and a third reviewer was consulted if agreement could not be reached. Any study involving a co-author of this review (AH, SB) was independently appraised. Papers were not excluded from the synthesis based on their quality, but study quality was taken into account in the synthesis and interpretation of findings.

Data extraction

Study characteristics (listed in Supplemental File 4) were extracted using a bespoke proforma.

Included full text papers were uploaded to NVivo software. 31 Results sections of the included papers and text describing study findings in the discussion sections were data for synthesis. This included both participant quotes and study authors’ interpretations.

Where several papers reported findings from the same study, they were treated as one study for study characteristics but text describing qualitative findings was extracted from each paper.

Synthesis

Study characteristics were summarised and presented in table form.

Thematic synthesis was used which draws upon the methods of thematic analysis. This can be situated as a critical realist approach: based on the assumption of a shared reality, our understanding of which is mediated by our perceptions and beliefs. Therefore, whilst the context of each study must be taken into account, transferable findings can be generated which can be used to inform practice 32 .

Findings were coded inductively (IF), line by line, using Nvivo software. 31 The process of synthesis was iterative. Codes were reviewed, merged and developed based on further data, resulting in 76 codes which were grouped and organised. Detailed summaries were written and descriptive themes and subthemes (listed in Supplemental File 5) were summarised in a report. This process and report were reviewed by AH.

In thematic synthesis, an external theoretical framework may be used to interrogate the descriptive themes and support the development of analytical themes. Analytical themes are interpretations that ‘go beyond’ the primary study findings and may include implications for practice drawn from the findings. 33 We used the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) definition of palliative care as an external theoretical framework to support the development of analytical themes, as several of its key concepts were central to our synthesis: the clinical pathway of prevention, early identification, impeccable assessment and treatment; the concept of ‘suffering’; a person-centred approach - addressing physical, psychological and spiritual issues; and the importance of family and relationships (See Box 1). 34 Initial analytical themes, developed by IF, were reviewed by the wider review team to produce the final three analytical themes.

Box 1.

World Health Organisation’s definition of Palliative Care. 34

| ‘Palliative care is an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychological and spiritual’. |

Results

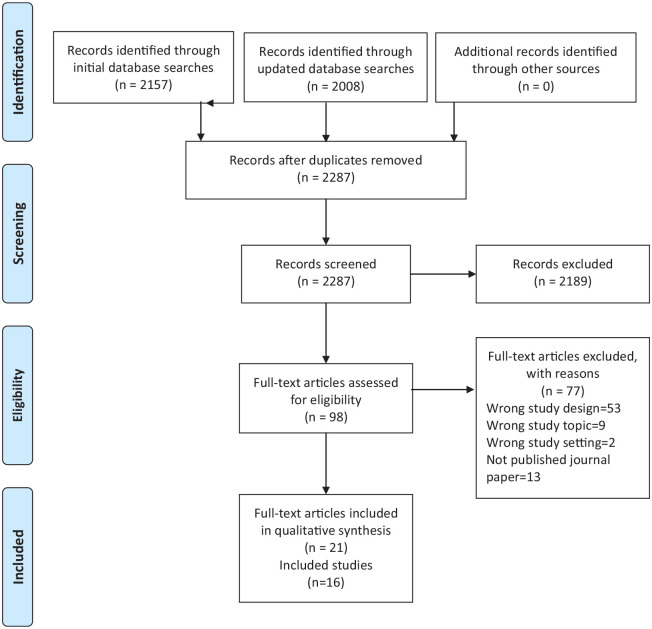

The study selection process is presented in Figure 1. 35 After de-duplication, 2287 titles and abstracts were screened and 98 full text papers were assessed for eligibility of which 21 papers reporting on 16 studies were included (see Supplemental File 6).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of study selection.

Study characteristics

The 16 studies were based in Australia (n = 4),22,23,36–39 Canada (n = 4),40–44 UK (n = 2),45,46 USA (n = 2),47,48 Japan (n = 2),49,50 Israel (n = 1)51–53 and New Zealand (n = 1). 54 Three of the studies were conducted by co-authors of this review.23,37–39,41 The majority of studies were conducted in palliative care inpatient settings, including seven based only in hospital inpatient units22,23,37–39,41,42,48,51–53 and six based only in hospice inpatient units.43–47,49,54 Two studies included hospital inpatient and homecare services40,50 and one study included a hospice inpatient and homecare service. 36 In total, 173 clinicians, 134 family members, 34 patients and 6 volunteers were included. In the studies including clinicians, the majority were nursing staff (qualified nurses, nursing assistants, health care assistants and patient care attendants) (n = 133). Other professional groups included doctors (n = 23), social workers (n = 3) and psychologists (n = 3) (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Study setting and participants.

| Study reference | Country | Palliative care setting | Participants |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Family | Volunteers | Clinicians | Nursing staff* | Doctors | Social workers | Psychologists | |||

| Agar et al. 22 | Australia | Hospital inpatient | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bolton et al. 54 | New Zealand | Hospice inpatient | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Brajtman51–53 | Israel | Hospital inpatient | 0 | 26 | 0 | 12 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Brajtman et al. 40 | Canada | Hospital inpatient; home care nursing team | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bush et al. 41 | Canada | Hospital inpatient | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 8 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Cohen et al. 48 | USA | Hospital inpatient | 34 | 37 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| De Vries et al. 45 | UK | Hospice inpatient | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gagnon et al. 42 | Canada | Hospital inpatient | 0 | 21 | ✔ | 11 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Greaves et al. 36 | Australia | Hospice inpatient; home palliative care service | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hosie et al.23,37,38** | Australia | Hospital inpatient | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hosie et al.38,39** | Australia | Hospital inpatient | 0 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Namba et al. 49 | Japan | Hospice inpatient | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Szarpa et al. 47 | USA | Hospice inpatient | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Uchida et al. 50 | Japan | Hospital inpatient; home care clinics | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 6 | 12 | 0 | 2 |

| Waterfield et al. 46 | UK | Hospice inpatient | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Wright et al43,44 | Canada | Hospice inpatient | 0 | 0 | 6 | 22 | 16 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Totals | 34 | 134 | 6 | 173 | 133 | 23 | 3 | 3 | ||

Includes nursing assistants, health care assistants, patient care attendants as well as qualified nurses.

Hosie et al. 38 reported data from two different studies.

Participants included but number not provided.

The studies used different methodologies including grounded theory22,47,50; phenomenological approaches45,46,48,51–53 and ethnography.43,44 The majority of studies employed semi-structured interviews.22,23,36–38,40,41,45–47,49–54 Other methods used were focus groups38,39,51–53; participant observation and document analysis43,44 (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Study aims, methods and findings.

| Study reference | Aims/objectives | Methodology | Data collection methods | Data analysis methods | Review themes contributed to by study | Subthemes contributed to by study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agar et al. 22 | To explore nurses’ assessment and management of delirium when caring for people with cancer, the elderly or older people requiring psychiatric care in the inpatient setting. | Grounded theory perspective | Semi-structured interviews | Thematic content analysis | 1. Interpretations of delirium and their influence on care | Limited understanding of delirium as a medical condition |

| 2. Palliative care clinicians’ responses to the suffering of patients with delirium | Decision-making regarding medication use | |||||

| Bolton et al. 54 | To explore carer experiences of inpatient unit hospice care for people with dementia, delirium and related cognitive impairment. | Not stated | Semi-structured interviews | Thematic analysis | 2. Palliative care clinicians’ responses to the suffering of patients with delirium | Person-centred care, communication and challenges |

| 3. The roles of family in delirium care | Beyond ‘person-centred’ care: responding to the needs of the family | |||||

| Family play vital roles in caregiving | ||||||

| Brajtman51–53 | To explore and describe the impact of terminal restlessness and its treatment upon the family members who were witness to the event. | Phenomenological approach | Focus groups, semi-structured interviews | Content analysis | 1. Interpretations of delirium and their influence on care | Delirium and multidimensional suffering |

| 2. Palliative care clinicians’ responses to the suffering of patients with delirium | Person-centred care, communication and challenges | |||||

| To explore an interdisciplinary team’s perceptions of families’ needs and experiences surrounding terminal restlessness. | Decision-making regarding medication use | |||||

| 3. The roles of family in delirium care | The distressing impact of delirium on the relationship between the patient and their family | |||||

| Beyond ‘person-centred’ care: responding to the needs of the family | ||||||

| Family play vital roles in caregiving | ||||||

| Brajtman et al. 40 | To explore palliative care unit and home care nurses’ experiences of caring for patients with terminal delirium. | Not stated | Semi-structured interviews | Thematic content analysis | 1. Interpretations of delirium and their influence on care | Limited understanding of delirium as a medical condition |

| Delirium and multidimensional suffering | ||||||

| 2. Palliative care clinicians’ responses to the suffering of patients with delirium | Decision-making regarding medication use | |||||

| 3. The roles of family in delirium care | Beyond ‘person-centred’ care: responding to the needs of the family | |||||

| Bush et al. 41 | To investigate the validity and feasibility of the RASS-PAL*, a version of the RASS** slightly modified for palliative care populations, in patients experiencing agitated delirium or receiving Palliative Sedation. | Mixed methods | Semi-structured interviews | Thematic content analysis | 1. Interpretations of delirium and their influence on care | Limited understanding of delirium as a medical condition |

| Cohen et al. 48 | To better understand the experiences of delirium of patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers | Hermeneutic phenomenological approach | Phenomenological interviews | Not stated | 1. Interpretations of delirium and their influence on care | Delirium and multidimensional suffering |

| 2. Palliative care clinicians’ responses to the suffering of patients with delirium | Decision-making regarding medication use | |||||

| 3. The roles of family in delirium care | The distressing impact of delirium on the relationship between the patient and their family | |||||

| Family play vital roles in caregiving | ||||||

| De Vries et al. 45 | To examine the experiences of hospice nurses when administering palliative sedation in an attempt to manage the terminal restlessness experienced by cancer patients. | Phenomenological approach | Semi-structured interviews | Colazzi’s stages of analysis | 1. Interpretations of delirium and their influence on care | Limited understanding of delirium as a medical condition |

| 2. Palliative care clinicians’ responses to the suffering of patients with delirium | Decision-making regarding medication use | |||||

| 3. The roles of family in delirium care | Beyond ‘person-centred’ care: responding to the needs of the family | |||||

| Gagnon et al. 42 | To develop the framework of an optimal psychoeducational intervention about delirium. | Not stated | Focus groups, semi-structured interviews | Not stated | 3. The roles of family in delirium care | Beyond ‘person-centred’ care: responding to the needs of the family |

| To develop a brochure to be used as part of the psychoeducational intervention. | Family play vital roles in caregiving | |||||

| To implement the psychoeducational intervention and assess its effect on family and professional caregivers. | ||||||

| Greaves et al. 36 | To better understand family caregivers’ perceptions and experiences of delirium in patients with advanced cancer | Not stated | Semi-structured interviews | Content analysis | 1. Interpretations of delirium and their influence on care | Delirium and multidimensional suffering |

| 2. Palliative care clinicians’ responses to the suffering of patients with delirium | Decision-making regarding medication use | |||||

| 3. The roles of family in delirium care | The distressing impact of delirium on the relationship between the patient and their family | |||||

| Family play vital roles in caregiving | ||||||

| Hosie et al.23,37,38 | To explore the experiences, views and practices of inpatient palliative care nurses in delirium recognition and assessment. | Critical incident technique | Semi-structured interviews | Thematic content analysis | 1. Interpretations of delirium and their influence on care | Limited understanding of delirium as a medical condition |

| Delirium seen as a normal part of dying | ||||||

| Delirium and multidimensional suffering | ||||||

| To identify nurses’ perceptions of barriers and enablers to recognition and assessment of delirium symptoms within palliative care inpatient settings | 2. Palliative care clinicians’ responses to the suffering of patients with delirium | Person-centred care, communication and challenges | ||||

| 3. The roles of family in delirium care | Family play vital roles in caregiving | |||||

| Hosie et al.38,39 | To explore nurse perceptions of the feasibility of integrating the Nu-DESC*** into practice within the inpatient palliative care setting. | Not stated | Focus groups | Thematic content analysis | 1. Interpretations of delirium and their influence on care | Limited understanding of delirium as a medical condition |

| Namba et al. 49 | To explore: (1) what the family members of terminally ill cancer patients with delirium actually experienced, (2) how they felt, (3) how they perceived delirium and (4) what support they desired from medical staff. | Not stated | Semi-structured interviews | Content analysis | 1. Interpretations of delirium and their influence on care | Delirium seen as a normal part of dying |

| 2. Palliative care clinicians’ responses to the suffering of patients with delirium | Person-centred care, communication and challenges | |||||

| Decision-making regarding medication use | ||||||

| 3. The roles of family in delirium care | The distressing impact of delirium on the relationship between the patient and their family | |||||

| Beyond ‘person-centred’ care: responding to the needs of the family | ||||||

| Family play vital roles in caregiving | ||||||

| Szarpa et al. 47 | To explore the development and progression of delirium experienced by hospice patients and to generate a theoretical model that describes the prodrome to delirium as observed by caregivers. | Grounded theory | Semi-structured interviews | Grounded theory | 1. Interpretations of delirium and their influence on care | Delirium and multidimensional suffering |

| 3. The roles of family in delirium care | Family play vital roles in caregiving | |||||

| Uchida et al. 50 | To identify goals of care and treatment in terminal delirium by interviewing healthcare professionals regarding their views on currently used approaches. | Grounded theory | Semi-structured interviews | Grounded theory | 2. Palliative care clinicians’ responses to the suffering of patients with delirium | Person-centred care, communication and challenges |

| 3. The roles of family in delirium care | Beyond ‘person-centred’ care: responding to the needs of the family | |||||

| Family play vital roles in caregiving | ||||||

| Waterfield et al. 46 | To explore the experiences of nurses and health care assistants caring for patients with delirium in the hospice environment. | Phenomenological approach | Semi-structured interviews | Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) | 1. Interpretations of delirium and their influence on care | Limited understanding of delirium as a medical condition |

| 2. Palliative care clinicians’ responses to the suffering of patients with delirium | Person-centred care, communication and challenges | |||||

| Decision-making regarding medication use | ||||||

| Wright et al.43,44 | To illustrate one of the ways in which hospice caregivers conceptualise end-of-life delirium and the significance of this conceptualisation for the relationships that they form with patients’ families in the hospice setting. | Ethnography | Participant observation, semi-structured interviews, document analysis | Not stated | 1. Interpretations of delirium and their influence on care | Delirium seen as a normal part of dying |

| Delirium and multidimensional suffering | ||||||

| 2. Palliative care clinicians’ responses to the suffering of patients with delirium | Person-centred care, communication and challenges | |||||

| Decision-making regarding medication use | ||||||

| To examine the relational engagement between hospice nurses and their patients in a context of end-of-life delirium. | 3. The roles of family in delirium care | The distressing impact of delirium on the relationship between the patient and their family | ||||

| Beyond ‘person-centred’ care: responding to the needs of the family |

Richmond agitation-sedation scale- palliative care.

Richmond agitation-sedation scale.

Nursing delirium screening scale.

Quality assessment

Trustworthiness of the study findings was assessed as high in five studies,22,23,36,37,39,41 medium in eight studies40,43–48,51–54 and low in three studies.42,49,50 Usefulness of the study findings was high for 2 studies,23,37,39 medium for 13 studies22,36,40,41,43–54 and low for 1 study 42 (see Table 3). Although data collection and analysis were rigorous in many of the studies, several did not provide a clear description of data analysis.42–44,49,50 In some studies, analysis was largely descriptive but provided valuable data on participants’ perspectives.36,46,48,49 Usefulness of some studies was limited by their use of the terms ‘terminal agitation’ or ‘terminal restlessness’ which overlap with, but are not identical to, delirium and were unlikely to include experiences of participants with hypoactive delirium.45,51–53

Table 3.

Quality assessment results.

| Study | Trustworthiness of findings | Usefulness of findings for this review |

|---|---|---|

| Agar et al. 22 | High | Medium |

| Bolton et al. 54 | Medium | Medium |

| Brajtman51–53 | Medium | Medium |

| Brajtman et al. 40 | Medium | Medium |

| Bush et al. 41 | High | Medium |

| Cohen et al. 48 | Medium | Medium |

| De Vries et al. 45 | Medium | Medium |

| Gagnon et al. 42 | Low | Low |

| Greaves et al. 36 | High | Medium |

| Hosie et al.23,37,38 | High | High |

| Hosie et al.38,39 | High | High |

| Namba et al. 49 | Low | Medium |

| Szarpa et al. 47 | Medium | Medium |

| Uchida et al. 50 | Low | Medium |

| Waterfield et al. 46 | Medium | Medium |

| Wright et al.43,44 | Medium | Medium |

Thematic synthesis

Through the iterative thematic synthesis approach, three main themes were identified: interpretations of delirium and their influence on care; palliative care clinicians’ responses to the suffering of patients with delirium and the roles of the family in delirium care. As most of the healthcare staff included in the studies were nursing staff, their perspectives are more strongly represented in the findings than those of other professional groups. The themes and their subthemes are presented below:

Interpretations of delirium and their influence on care

The understanding and interpretations that people had of delirium influenced their actions. This theme explores how limited understanding of delirium as a medical condition, the interpretation of delirium as a normal part of dying and the recognition of delirious patients’ suffering, influenced palliative care clinicians’ responses to delirium and the care provided.

Limited understanding of delirium as a medical condition

Palliative care nursing staff’s limited understanding of delirium as a medical condition influenced their ability to provide care according to the clinical pathway of prevention, early identification, assessment and treatment, outlined in the WHO definition of palliative care. 34

Palliative care nurses’22,23,37,46 understanding of delirium as a medical condition was variable and often very limited. A nurse commented,

“I really believe that we really don’t understand delirium at all.” 23 (Nurse, p.1359)

While hypoactive symptoms of delirium were rarely described, 22 nurses commonly described symptoms or behavioural changes related to hyperactive delirium, such as agitation, wandering, verbal aggression, calling out, climbing out of bed and pulling out intravenous cannulae or indwelling catheters.22,23,40 However, they often did not identify them as signs of delirium, or use the term ‘delirium’,22,23,46

“I don’t even ever use the term delirium actually. . .I would say that people were anxious or irritated or. . .I don’t know.” 46 (Nurse, p.528)

Nurses’ unclear understanding of delirium sometimes led them to interpret its symptoms as being attributable to other factors, such as the patient’s personality or old age. 37

In Agar et al.’s 22 study, many nurses had limited knowledge of possible causes of delirium and took a problem-solving approach to a small number of common problems, often bowel or urinary problems. Other nurses, particularly those in advanced practice roles, had wider knowledge and described more comprehensive assessment to address the modifiable causes of a patient’s delirium.22,23 Screening and assessment tools were rarely used in routine practice, although in feasibility studies staff were positive about their potential to aid early identification and inter-professional communication.23,37,39,41

There was no discussion of delirium prevention in the included studies.

Some nurses expressed feelings of uncertainty, anxiety and being out of their depth regarding how to manage delirium symptoms,23,37,45,46

“You are wondering is it by talking to the patients, sitting with them and asking them what they are seeing and stuff like that, is that going to help. . .Sometimes you feel. . .a bit helpless. . .like, ‘Oh God, what am I going to do here?’ “ 23 (Nurse, p.1358)

“I wasn’t getting anywhere with what I was giving her, I was, like I say, I was out of my depth at that time.” 45 (Nurse, p.154)

Palliative care nurses recognised their need to develop greater understanding of delirium, including its causes, recognition, assessment and management.22,37,40 Team reflective learning opportunities that used real patient scenarios were particularly valued.37,40

Delirium seen as a normal part of dying

Some clinicians perceived delirium as a normal part of dying. In two studies, clinicians normalised delirium as one of a series of predictable changes within a natural dying process to help family to adjust to their loved one’s impending death,43,49

“It’s the physical changes. . .and delirium’s another one that gets people moving toward. . .’Okay this person’s changing’. . .the little deaths that the person is having, um, are, the person is changing and leaving. You know, and in the big picture, that’s helpful to the family.” 43 (Psychologist, p.962)

Hosie et al. 23 found that characterising delirium symptoms as part of the dying process, through the use of terminology such as ‘terminal restlessness’ or ‘terminal agitation’, impeded nurses’ understanding of delirium and they were less likely to undertake assessment of modifiable causes,

“My (nursing colleague) was using the terminology (terminal restlessness). . . And I said, ‘‘Have we done a PR [rectal examination]? Have we done a bladder scan? Have we checked the urine? . . . The nursing staff got back to me – even though he’d been urinating he had a bladder of 1000 mls. So they’ve put a catheter in.’’ 23 (Nurse, p.1359)

If delirium is seen as a ‘normal’ part of dying, this may offer some reassurance to family but may act as a barrier to clinicians seeking potentially modifiable causes.

Delirium and multidimensional suffering

The suffering of patients with delirium was strongly emphasised in the included studies. Whether or not clinicians and family had knowledge of delirium, they recognised and responded to, the patient’s experience of suffering.

Patients, family and clinicians described this suffering and distress,47,48,53

“The whole thing was terrible, it was very stressful.” 48 (Patient, p.167)

“He was suffering, absolutely” 47 (Family member,p.335)

“It is seen as the ultimate in suffering.” 53 (Nurse, p.173)

The distress caused to patients by their delirium was intertwined with their experience of suffering close to the end of life. Some family and nursing staff saw the distressing experiences of patients with delirium as primarily expressions of psychological, spiritual or existential suffering.23,36,40,48,52 A wife worried that her husband’s agitation was,

“Because he was frightened about dying.” 36 (Family member, p.8)

A nurse explained that,

“To me, sometimes delirium is people’s personal devils are being released. What come out are their own devils at that point and it’s really important to try and understand that.” 40 (Nurse, p.152)

Hosie et al. 23 argued that when nurses perceived a spiritual reason for patients’ hallucinations or illusions, they were less likely to undertake further assessment of possible underlying physical causes.

Some family members and clinicians perceived the suffering of patients with delirium as multi-dimensional. Brajtman 53 described that the interdisciplinary team perceived patients experiencing delirium close to the end of life as, “suffering physically, emotionally and spiritually” (p.173). Some family members also described their loved ones suffering involving both physical and mental distress.

“There was that restlessness, that combination of pain and emotional stress. I don’t know what it was made up of.” 51 (Family member, p.456)

“I knew he was suffering, whether it was mentally or physically.” 47 (Family member, p.335)

Clinicians expressed a sense of emotional urgency to respond to the patient’s suffering,44,53

“It’s urgent to do something for that poor patient. . .a patient in delirium. . .inside is really in big distress.” 44 (Doctor, p.4)

“The patient is suffering terribly, is really suffering, why we don’t know, but it is a dramatic impression and we need to stop it.” 53 (Nurse, p.173)

Palliative care clinicians’ responses to the suffering of patients with delirium

Many of the included studies focused on managing the distressing symptoms and suffering related to delirium, rather than preventing it or modifying its underlying causes. Two linked subthemes were developed in relation to clinicians’ responses to the suffering of patients with delirium. The first explores a person-centred approach to patients’ suffering, and the challenges to this. The second explores the influences on clinicians’ decision-making about medication use to manage the distressing symptoms of delirium.

Person-centred care, communication and challenges

Clinicians described taking a person-centred approach to care for patients with delirium,23,43,44,46,50,54

“I love the whole approach and it is holistic in here - we look at the whole patient and everything that makes a difference.” 46 (Nurse, p.531)

Learning about the patient’s life and interests, from them or their family, helped clinicians to build relationships with them.49,50,54

“If we have heard about the patient’s whole life, we can view the situation as a continuation of the life.” 50 (Doctor, p.3)

“She loved playing Yahtzee. . .the staff member knew that she liked it so they would take it out and they would play with her.” 54 (Family member, p.399)

Family described nurses treating patients as individuals, with kindness and respect,

“The nurse always had patience and a smile. . .That human way of relating, that the patient isn’t a chart but a person, even if he is at the end of his life.” 52 (Family member, p.77)

In Wright et al.’s 44 study, nursing staff sought to engage in meaningful communication with patients, despite their delirium. For example, this exchange can be interpreted as the nursing assistant engaging with the patient’s psychological needs close to the end of life,

“He said to her, ‘We have to go’ and when she asked where, he said, ‘To the airport, we have to get to the funeral.’ She then asked him whose funeral and he replied, ‘Mine!’ . . .She asked him if he thinks it will be soon and he said, yes, he was ready.” 44 (Nursing assistant, p.5)

However, in interview studies, nursing staff described how providing person-centred care could be challenging when working with patients with delirium. The change in the patient and their behaviour was sometimes distressing for nurses and made it difficult to relate to them,

“He was screaming at the top of his lungs. . .he was holding the buzzer, and he was saying that, ‘That’s a bomb’ and he’s angry with the nurses. . .” 23 (Nurse, p.1358)

“The change in her was massive and it was really quite hard to relate to her.” 46 (Nurse, p.531)

Difficulties in communicating with patients with delirium made it difficult for nursing staff to get to know them, their preferences and goals of care,

“Our delirium patients don’t have a voice sometimes, they are just patients that we are caring for, but they don’t know who they are properly. . .We don’t know who they are properly, so what is to say that the care that we are giving is right for them?. . .I don’t know if I’m doing the right thing for my patient as I don’t know what they’re normally like, what their values are and what they believe.” 46 (Nurse, p.531).

Decision-making regarding medication use

Clinicians commonly described using medication to try to control delirium symptoms and to calm or sedate patients experiencing hyperactive symptoms.22,45,53 In several studies, clinicians’ use of sedating medication was described as being guided by values that are widely held in palliative care including the aims to alleviate patient suffering, achieve patient comfort and a ‘peaceful’ death.44,45,53

When patients with delirium were unable to communicate their preferences or goals of care, decision-making regarding the use of sedating medication could be ethically challenging,

“Not every patient. . .agrees that they should have been sedated. They feel that they should have been cared for and looked after, brought down by words.” 46 (Nurse, p.530)

“It would become an ethical dilemma if, if you really can’t discuss it with the patient properly, so you try to explain it to the family, and it depends where the family are at. We need to remember, we are treating the patient not the family.” 45 (Nurse, p.153)

Clinicians’ desire to alleviate the distress of family members, was found to be a strong influence on medication treatment decisions,45,53

“They were desperate for it. It wasn’t that they haven’t thought of (sedation) and we put it to them as an idea. . .They were so upset by seeing their loved one distressed . . . They were almost begging for us to do something.” (Nurse, p.153)

Examples were given of family gaining comfort from patients being ‘peaceful’ when they had been sedated close to the end of life.44,45

Other family members felt that less sedation should have been used so that they could still communicate with the patient,51,52 or felt conflicted between the desire to communicate and to alleviate suffering,

“My mother would say, ‘don’t sedate him, let him speak to us, be with us.’” 51 (Family member, p.457)

“I suppose I just wish that we had, he had wanted to say goodbye in some way. . .And I just wondered whether I should have done something to tell them that I didn’t want him sedated so much, but you really have to, you sort of feel like you have to do what, what they are suggesting, because you don’t want the person to be suffering.” 36 (Family member, p.8)

The decision to use sedation was sometimes influenced not only by the patient’s suffering or the family’s distress, but also in response to clinicians’ own difficulty and distress in working with patients with delirium,

“The sedation is for the family, but maybe the major reason we are so disturbed by terminal restlessness is because of us and not just because of the families.” 53 (Nurse, p.173)

“It’s just as difficult for me, you want a quick solution.” 53 (Doctor, p.173).

Lack of time and staffing levels also influenced the decision to use medication,22,53

“I think that sometimes because of lack of time the emphasis is on medication. If we had more time we could sit with the patient, give him a massage. . .It’s not realistic with only two nurses on in the evening.” 53 (Nurse, p.173)

Many family members described staying with patients to reassure and comfort them36,48,49 and this sometimes resulted in less sedation being used. 53 Volunteers could also help in this way,

“We have volunteers who are extraordinary and we. . .get them to go and sit and spend extra time with somebody.” 40 (Nurse, p.153)

The roles of the family in delirium care

Relationships between patients, their families and clinicians influenced care in complex ways. This included the distressing impact that delirium had on the relationships between patients and their families; how clinicians went beyond ‘person-centred care’ of the patient to respond to the needs of the family, and the vital roles that family played in caregiving.

The distressing impact of delirium on the relationship between the patient and their family

In many studies, family members vividly described how the experience of delirium had a distressing impact on their relationship with their loved one. They described sadness when delirium interfered with their ability to communicate and have significant conversations at the end of life,36,48,52

“It meant we didn’t have any sort of deep conversations.. . . there was no saying goodbye or what are we going to do or you know anything like that.” 36 (Family member, p.6)

This patient described the anger towards his family that he experienced whilst confused and hallucinating,

“I was really mad at my daughter and my sister because they wouldn’t let me up. They was keeping me tied down. I was riding the horse. I rode that horse probably about six hours. . .some kind of Indian award, cause we had tepees everywhere. . .really confusing. I was mad at them- probably as mad as I’ve ever been.” 48 (Patient, p.167)

Family were upset and sometimes fearful when faced with verbal or physical aggression,

“The hate and anger that was coming out of him. I’d be quite honest, I was scared stiff. I did not know what to expect next.” 36 (Family member,p.7)

Family members were distressed by witnessing the suffering of patients with delirium and felt helpless in the face of it,36,48,52

“I was sitting there and just crying and crying, and my feeling was there’s nothing more I can do for him to make him comfortable. It was just totally heart breaking to watch him those last nights.” 52 (Family member,p.75)

Some family members described feelings of extreme exhaustion and desperation.36,49

In a few cases where patients did not seem distressed by their delirium experience, family members felt their delirious beliefs and hallucinations were a source of comfort to the patient.48,49

Beyond ‘person-centred’ care: responding to the needs of the family

Clinicians went beyond the person-centred care of the patient to respond to the needs of the family. In several studies, clinicians recognised the distress that delirium can cause to family members and sought to alleviate it,40,43,45

“You don’t want. . .that episode, to be how the family will remember them. It’s part of a continuum, it may be almost the final part, and we don’t want people to have that memory, just that memory of the person’s life.” 40 (Nurse, p.152)

As previously discussed, clinicians’ desire to alleviate the distress of family members could be a strong influence on treatment decision-making, including medication use.

“The families cannot stand seeing it, they say, ‘do something.’” 53 (Social worker, p.173).

Clinicians also responded to the needs of the family for support and information. Family members expressed differing needs for support. Some felt supported when staff relieved their burden of care and enabled them to rest,45,49,50,54

“I knew he was safe and I knew I could go home and have a sleep and not worry.” 54 (Family member, p.401)

Others appreciated being reassured and supported in how to care for the patient.42,49

Family felt it would be useful to receive information related to delirium causes, symptoms, treatment, patient’s distress, how to approach the patient, prognosis and the dying process,49,52 and that it would be helpful to receive information in advance. 48

Family members in Gagnon’s 42 study who received written and verbal information said this improved their understanding and confidence in responding to symptoms, enabled them to spend more time with the patient and reduced their own distress.

Family play vital roles in caregiving

Family members played vital roles in caring for patients with delirium. Nurses highlighted the importance of engaging with family in identifying delirium, because they recognised behaviour changes that staff may miss, and because the patient may have told family members about distressing symptoms,

“She would lie in her bed really quietly. . . but she always had this frightened look on her face and when her family came to visit . . . they told us that . . . she felt really scared because she was seeing someone in the room with her.” 23 (Nurse, p.1360)

In interviews, family members gave vivid, detailed descriptions of many delirium symptoms, including memory loss, disorientation, hallucinations and delusions36,47,52 and described changes from the patient’s usual behaviour, particularly when they became verbally or physically aggressive,

“[My husband] was a fairly placid sort of person. So when he started swearing at me and getting agro I mean, you know we knew then that he was very confused himself. . .” 36 (Family member, p.6)

They not only described restlessness and agitation but also patients becoming withdrawn, losing interest in things and inattention (symptoms of hypoactive delirium),36,47 which were rarely talked about by staff who took part in the studies,

“(He) just shut off-he wasn’t talking or anything. So he just locked himself in his little cocoon.” 36 (Family member, p.5)

Family supported person-centred care by helping palliative care staff to learn about the patient’s life and interests,49,50,54 and by staying with patients to reassure and comfort them.36,48,49,53

Discussion

In this thematic synthesis of 16 studies we found that palliative care nursing staff had limited understanding of delirium as a medical condition with underlying potentially modifiable physical causes.22,23,37,46 While nurses commonly described behavioural changes related to hyperactive delirium, hypoactive symptoms were rarely described. Some clinicians perceived delirium as a normal part of dying.23,43,49 The suffering experienced by patients with delirium was emphasised, and responded to, by clinicians and family members.47,48,53 Clinicians often took a person-centred approach to address patients’ multidimensional needs.23,43,44,46,50,54 However, changes in the patient’s behaviour and difficulties in communication caused by delirium, posed challenges to this.23,45,46 Clinicians commonly described using medication to try to control delirium symptoms.22,45,53 This was influenced by the desire to alleviate patients’ suffering44,45,53 and also by the distress of the family45,53 and of clinicians themselves, as well as by the available time and staffing levels.22,45,53 Family were both recipients of palliative care and played vital roles in identifying and caring for patients with delirium.36,48,49,53

Opportunities to increase palliative care nursing staff’s understanding of delirium as a medical condition need to be developed, to enable them to use strategies to prevent, recognise and manage delirium in line with current evidence and guidelines: including targeting modifiable risk factors; screening; assessment and modification of underlying causes; and use of non-pharmacological strategies in preference to medication for symptom management.34,14–16,18 Increased recognition of hypoactive symptoms of delirium is particularly important, as it is the most common delirium subtype in palliative care settings 3 and can be as distressing for patients as hyperactive delirium.55,56 Family members in the included studies recognised behaviour changes such as the patient becoming inattentive or withdrawn, and clinicians could draw on this to increase their recognition of hypoactive delirium. If clinicians perceive delirium as part of the normal dying process, they may be less likely to seek modifiable causes. 23 The use of the term ‘delirium’ rather than ‘terminal agitation’ or ‘terminal restlessness’ may encourage clinicians to conceive of it as a medical condition with causes that may potentially be modified. When patients are close to the end of life, the benefits and burdens of assessment and modification of underlying causes should be carefully weighed, in accordance with the patient’s goals of care. 8 In the last hours or days of life, most patients will experience an episode of delirium that cannot be prevented or modified. However, it may be possible to modify some common contributing factors, such as medications, without intrusive intervention in order to reverse or reduce the severity of the delirium. 57

The suffering of palliative care patients with delirium, and the need to alleviate this, was emphasised by both clinicians and family.47,48,53 The distress caused to patients by their delirium was intertwined with their experience of suffering close to the end of life. Cassell 58 defined suffering as, ‘the state of severe distress associated with events that threaten the intactness of the person’.(p131). These threats to the integrity of a person can be experienced in relation to multiple dimensions, including, ‘physical, psychological, spiritual, social and cultural dimensions’ (Krikorian p804).34,59 A multi-dimensional approach is therefore needed, including assessing and modifying the physical causes of delirium whilst also responding to the person’s psychological, emotional or spiritual distress. Clinicians described building relationships with patients and taking a person-centred approach to address their multidimensional needs.23,43,44,46,50,54 However, it was often challenging to communicate and build relationships with patients with delirium, and to understand their preferences or goals of care.23,45,46

In this thematic synthesis, palliative care clinicians commonly reported the use of sedating medication when patients were experiencing hyperactive symptoms of delirium, with the aims of alleviating patient suffering, achieving patient comfort and a ‘peaceful’ death.44,45,53 Maltoni et al. 60 found that refractory delirium in the terminal stages of illness was the most common indication for palliative sedation. However, there is limited evidence as to the efficacy of palliative sedation for controlling refractory delirium symptoms at the end of life. 61 Some patients, but not all, may wish to be sedated to alleviate their suffering towards the end of life. Perspectives upon what constitutes a ‘good death’ are highly individual.62,63 Patient comfort and control have been reported as the attributes valued most highly by patients, physicians and nurses, but these may sometimes conflict with one another.62,63 When patients with delirium are unable to communicate their preferences and goals of care, treatment decision-making can be ethically challenging.45,46 Due to the high prevalence of delirium in palliative care settings, 4 enabling patients to make advance care plans could help to increase their control and support clinicians to provide person-centred care.

Decision making regarding the use of medication was also influenced by time, staffing levels, the desire to alleviate the distress of family members and clinicians’ own difficulty and distress in working with the patient with delirium.22,45,53 Therefore, in treatment decision making, a reflective approach is important, with consideration of whose needs are primarily being addressed. A relational ethics approach, which highlights that ethical decisions and actions are made within the context of relationships, could be valuable to support clinicians to work through these complex situations. 64 In order to support ethical decision making regarding medication use, clinicians also need an understanding of the evidence for its effectiveness. Nikooie et al.’s 17 systematic review found that current evidence does not support routine use of antipsychotics to treat delirium in hospitalised adults and Finucane et al.’s 18 Cochrane review of drug therapy in terminally ill adults found a lack of high quality evidence for the use of antipsychotics or benzodiazepines for delirium. In view of the lack of evidence to support the routine use of medication for delirium symptoms, an increased focus is needed on non-pharmacological approaches to care, including prevention. 10

The WHO definition identifies family as important recipients of palliative care, as well as the patient. 34 The included studies demonstrated that clinicians went beyond ‘person-centred’ care of the patient, in responding to the distress and needs of the family.42,45,49,50,54 Family members were both recipients of care and played vital caregiving roles within caregiving ‘triads’ between patients, families and formal caregivers. 65 Some family members valued staff relieving their burden of care, while others appreciated being supported in how to care for the patient.45,49,50,54 Due to their close relationships with patients, family could play important roles in the recognition of delirium, reassuring and comforting patients and advocating for them.36,48,49,53

Strengths/limitations of review

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and thematic synthesis to include the perspectives of patients, family, clinicians and volunteers on delirium and its care in palliative care settings. In this review, only one study included palliative care patients as participants. 48 However, the views of family caregivers were strongly represented.36,42,47–49,51,52,54 As most of the healthcare staff included in the studies were nursing staff, their perspectives are more strongly represented in the findings than those of non-nursing staff (doctors, allied health professionals etc.) and volunteers. The extent to which some of the findings are transferable to other palliative care clinicians may be limited.22,23,37–46,50–53 Most of the included studies are from high income, English-speaking countries (US/UK/AU/NZ/Canada) which may limit the transferability of the findings. Also, notably, no studies focused on delirium prevention.

As the clinicians in the included studies were not always clearly able to recognise delirium and may not always have been able to distinguish it from similar conditions such as depression or dementia, it is possible that in some cases, they may have been recalling patients’ behaviours or distress associated with these other conditions. Strengths of the review include its robust methods, including systematic database searching; screening and quality assessment by two independent reviewers; and the use of thematic synthesis, a rigorous method of synthesis that facilitates transparency of reporting. 33

The quality of the included studies was also a strength: the trustworthiness of their findings was assessed as high or medium in most. 30 A limitation was restriction of the review to English language papers.

What this review adds?

By synthesising the findings from qualitative studies of patients’, families’, clinicians’ and volunteers’ experiences of delirium and its care in palliative settings, this systematic review integrated the perspectives of different stakeholders. This is important to inform clinical practice and new interventions to prevent and manage delirium, and to better support affected patients, family and clinicians in palliative care. Clinical implications of the findings include:

- Opportunities to increase palliative care nursing staff’s recognition of delirium as a medical condition and understanding of its prevention and management need to be developed.

- The suffering caused by delirium may be reduced by an increased focus on preventing delirium, recognising it early and addressing modifiable causes. Routine structured processes and tools for prevention, screening and assessment of delirium may support this.

- Taking a person-centred approach may enable clinicians and volunteers to address the multiple dimensions of the suffering of patients with delirium, including assessing underlying physical causes and addressing psychological and spiritual needs.

- Patient involvement in treatment decision-making should be supported as far as possible, including advance planning. Opportunities for clinicians to reflect upon the influences on treatment decision-making, individually or as a team, should be developed, to enable them to take an ethical and evidence-based approach.

- Due to the challenges of communicating and building relationships with some patients with delirium, staff may need practical (time, staffing levels) and emotional support to enable increased use of non-pharmacological approaches to care.

- Families can play vital roles in identifying delirium, reassuring and caring for the patient and advocating for them. Their information and support needs should be addressed.

Conducting this systematic review also identified important gaps in research evidence. In hospital settings, delirium interventions with the most robust evidence of effectiveness aim to prevent delirium through targeting its modifiable risk factors, and yet none of the included studies focused on delirium prevention. 16 There is a need for further research into current practice regarding delirium prevention in palliative care.

It is important to understand and integrate the perspectives of all relevant stakeholders to work towards improving delirium care. Increased research into patients’ perspectives is needed. Although there are practical and ethical challenges to conducting formal interviews close to the end of life, interviews could be conducted with patients earlier in the illness trajectory or other research methods, such as participant observation and informal interviews may be used. As effective delirium care requires a multi-disciplinary team approach, there is a need for further qualitative research into the perspectives of doctors, allied health professionals and other non-nursing staff. In other settings, volunteers play a central role in effective delirium prevention interventions such as Inouye et al.’s 66 Hospital Elder Life Program for Prevention of Delirium (HELP) in US hospitals, so increased research to explore their potential role in preventing delirium and supporting delirious patients and their families in palliative care settings would be valuable.

Conclusions

The insights gained from this systematic review can be used both to inform delirium care and the development of interventions to support this in palliative care settings. Opportunities to increase understanding of delirium, and the role of non-pharmacological approaches in its prevention and management, need to be developed. The role of the family is often vital in delirium care and should be supported. Reflective learning opportunities and practical and emotional support may be needed to enable clinicians to meet the challenges of providing person-centred care to patients with delirium, to address the multidimensional needs of patients and their families, in order to improve their quality of life.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-pmj-10.1177_02692163211006313 for The experience of delirium in palliative care settings for patients, family, clinicians and volunteers: A qualitative systematic review and thematic synthesis by Imogen Featherstone, Annmarie Hosie, Najma Siddiqi, Pamela Grassau, Shirley H Bush, Johanna Taylor, Trevor Sheldon and Miriam J Johnson in Palliative Medicine

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-pmj-10.1177_02692163211006313 for The experience of delirium in palliative care settings for patients, family, clinicians and volunteers: A qualitative systematic review and thematic synthesis by Imogen Featherstone, Annmarie Hosie, Najma Siddiqi, Pamela Grassau, Shirley H Bush, Johanna Taylor, Trevor Sheldon and Miriam J Johnson in Palliative Medicine

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-pmj-10.1177_02692163211006313 for The experience of delirium in palliative care settings for patients, family, clinicians and volunteers: A qualitative systematic review and thematic synthesis by Imogen Featherstone, Annmarie Hosie, Najma Siddiqi, Pamela Grassau, Shirley H Bush, Johanna Taylor, Trevor Sheldon and Miriam J Johnson in Palliative Medicine

Supplemental material, sj-docx-4-pmj-10.1177_02692163211006313 for The experience of delirium in palliative care settings for patients, family, clinicians and volunteers: A qualitative systematic review and thematic synthesis by Imogen Featherstone, Annmarie Hosie, Najma Siddiqi, Pamela Grassau, Shirley H Bush, Johanna Taylor, Trevor Sheldon and Miriam J Johnson in Palliative Medicine

Supplemental material, sj-docx-5-pmj-10.1177_02692163211006313 for The experience of delirium in palliative care settings for patients, family, clinicians and volunteers: A qualitative systematic review and thematic synthesis by Imogen Featherstone, Annmarie Hosie, Najma Siddiqi, Pamela Grassau, Shirley H Bush, Johanna Taylor, Trevor Sheldon and Miriam J Johnson in Palliative Medicine

Supplemental material, sj-docx-6-pmj-10.1177_02692163211006313 for The experience of delirium in palliative care settings for patients, family, clinicians and volunteers: A qualitative systematic review and thematic synthesis by Imogen Featherstone, Annmarie Hosie, Najma Siddiqi, Pamela Grassau, Shirley H Bush, Johanna Taylor, Trevor Sheldon and Miriam J Johnson in Palliative Medicine

Supplemental material, sj-docx-7-pmj-10.1177_02692163211006313 for The experience of delirium in palliative care settings for patients, family, clinicians and volunteers: A qualitative systematic review and thematic synthesis by Imogen Featherstone, Annmarie Hosie, Najma Siddiqi, Pamela Grassau, Shirley H Bush, Johanna Taylor, Trevor Sheldon and Miriam J Johnson in Palliative Medicine

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kath Wright (Information Service Manager, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York) for her invaluable contribution to the electronic database search.

Footnotes

Author contributions: IF, AH, NS, PG, SB, JT, TS and MJ contributed to the concept and design of the work and the analysis or interpretation of data. IF, AH, PG, JT and SB screened papers for inclusion; IF, AH, PG and JT conducted quality assessment of included papers; IF drafted a report of themes and the article which were reviewed and critically revised for important intellectual content by AH, NS, PG, SB, JT, TS and MJ. All authors have approved the version to be published.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: As stated in the review, AH and SB authored papers that were included in this review. The quality of these papers was appraised independently by different reviewers. The author(s) declared no other potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: Imogen Featherstone is funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Doctoral Fellowship [DRF-2017-10-063]for this research. This paper presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Ethical approval: No ethical approval was required for this research, as the study was a review of existing published articles with no new primary data collected.

ORCID iDs: Imogen Featherstone  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9042-7600

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9042-7600

Annmarie Hosie  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1674-2124

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1674-2124

Johanna Taylor  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5898-0900

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5898-0900

Miriam J Johnson  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6204-9158

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6204-9158

Data management and sharing: All the papers included in this review are available through their respective journals.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington,VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Meagher D. Motor subtypes of delirium: past, present and future. Int Rev Psychiatry 2009; 21: 59–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Watt CL, Momoli F, Ansari MT, et al. The incidence and prevalence of delirium across palliative care settings: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2019; 33: 865–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hosie A, Davidson PM, Agar M, et al. Delirium prevalence, incidence, and implications for screening in specialist palliative care inpatient settings: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2013; 27: 486–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Salluh JI, Wang H, Schneider EB, et al. Outcome of delirium in critically ill patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2015; 350: h2538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. O’Malley G, Leonard M, Meagher D, et al. The delirium experience: a review. J Psychosom Res 2008; 65: 223–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Finucane AM, Lugton J, Kennedy C, et al. The experiences of caregivers of patients with delirium, and their role in its management in palliative care settings: an integrative literature review. Psychooncology 2017; 26: 291–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lawlor PG, Davis DH, Ansari M, et al. An analytical framework for delirium research in palliative care settings: integrated epidemiologic, clinician-researcher, and knowledge user perspectives. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014; 48:159–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gagnon P, Allard P, Gagnon B, et al. Delirium prevention in terminal cancer: assessment of a multicomponent intervention. Psychooncology 2012; 21: 187–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hosie A, Phillips J, Lam L, et al. A multicomponent nonpharmacological intervention to prevent delirium for hospitalized people with advanced cancer: a phase II cluster randomized waitlist controlled trial (The PRESERVE Pilot Study). J Palliat Med 2020; 23(10): 1314–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Agar MR, Lawlor PG, Quinn S, et al. Efficacy of oral risperidone, haloperidol, or placebo for symptoms of delirium among patients in palliative care: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Internal Medicine 2017; 177(1): 34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hui D, Frisbee-Hume S, Wilson A, et al. Effect of lorazepam with haloperidol vs haloperidol alone on agitated delirium in patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative care: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017; 318: 1047–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lin C-J, Sun F-J, Fang C-K, et al. An open trial comparing haloperidol with olanzapine for the treatment of delirium in palliative and hospice center cancer patients. J Intern Med Taiwan 2008; 19: 346–354. [Google Scholar]

- 14. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Delirium: prevention, diagnosis and management. CG103. Manchester, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). Risk reduction and management of delirium. Edinburgh, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Siddiqi N, Harrison JK, Clegg A, et al. Interventions for preventing delirium in hospitalised non-ICU patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; 3: CD005563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nikooie R, Neufeld KJ, Oh ES, et al. Antipsychotics for treating delirium in hospitalized adults. Ann Intern Med 2019; 171: 485–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Finucane AM, Jones L, Leurent B, et al. Drug therapy for delirium in terminally ill adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020; 1(1): CD004770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Woodhouse R, Siddiqi N, Boland JW, et al. Delirium screening practice in specialist palliative care units: a survey. BMJ Support Palliat Care. Epub ahead of print 15 May 2020. DOI: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Boland JW, Kabir M, Bush SH, et al. Delirium management by palliative medicine specialists: a survey from the association for palliative medicine of Great Britain and Ireland. BMJ Support Palliat Care. Epub ahead of print 4 March 2019. DOI: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2018-001586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hosie A, Agar M, Brown L, et al. Clinical practice and practice change in the treatment of delirium: an online survey of Australian doctors, nurses and pharmacists. In: European delirium association 2019 meeting. Edinburgh, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Agar M, Draper B, Phillips P, et al. Making decisions about delirium: a qualitative comparison of decision making between nurses working in palliative care, aged care, aged care psychiatry, and oncology. Palliat Med 2012; 26: 887–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hosie A, Agar M, Lobb E, et al. Palliative care nurses’ recognition and assessment of patients with delirium symptoms: a qualitative study using critical incident technique. Int J Nurs Stud 2014; 51: 1353–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wright DK, Brajtman S, Macdonald ME. A relational ethical approach to end-of-life delirium. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014; 48: 191–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, et al. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012; 12: 181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Featherstone I, Hosie A, Grassau P, et al. The experience of delirium in palliative care settings: a qualitative synthesis. PROSPERO: International prospective register of systematic reviews. Report no. CRD42018102417, 2018. Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=102417 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Datla S, Verberkt CA, Hoye A, et al. Multi-disciplinary palliative care is effective in people with symptomatic heart failure: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. Palliat Med 2019; 33: 1003–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence systematic review software. Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 29. NHS England. Specialist level palliative care: information for commissioners. England, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rees R, Oliver K, Woodman J, et al. The views of young children in the UK about obesity, body size, shape and weight: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2011; 11: 188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. QSR International. Nvivo 12 Pro, https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home (accessed 22 March 2021).

- 32. Barnett-Page E, Thomas J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Med Res Methodol 2009; 9: 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008; 8: 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. World Health Organisation. WHO definition of palliative care, https://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/(2004, accessed 8 October 2019).

- 35. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151: 264–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Greaves J, Vojkovic S, Nikoletti S, et al. Family caregivers’ perceptions and experiences of delirium in patients with advanced cancer. Aust J Cancer Nurs 2008; 9: 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hosie A, Lobb E, Agar M, et al. Identifying the barriers and enablers to palliative care nurses’ recognition and assessment of delirium symptoms: a qualitative study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014; 48: 815–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hosie A, Agar M, Lobb E, et al. Improving delirium recognition and assessment for people receiving inpatient palliative care: a mixed methods meta-synthesis. Int J Nurs Stud 2017; 75: 123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hosie A, Lobb E, Agar M, et al. Nurse perceptions of the nursing delirium screening scale in two palliative care inpatient units: a focus group study. J Clin Nurs 2015; 24:3276–3285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Brajtman S, Higuchi K, McPherson C. Caring for patients with terminal delirium: palliative care unit and home care nurses’ experiences. Int J Palliat Nurs 2006; 12(4): 150–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bush SH, Grassau PA, Yarmo MN, et al. The richmond agitation-sedation scale modified for palliative care inpatients (RASS-PAL): a pilot study exploring validity and feasibility in clinical practice. BMC Palliat Care 2014; 13: 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gagnon P, Charbonneau C, Allard P, et al. Delirium in advanced cancer: a psychoeducational intervention for family caregivers. J Palliat Care 2002; 18: 253–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wright DK, Brajtman S, Cragg B, et al. Delirium as letting go: an ethnographic analysis of hospice care and family moral experience. Palliat Med 2015; 29: 959–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wright DK, Brajtman S, Macdonald ME. Relational ethics of delirium care: findings from a hospice ethnography. Nurs Inq 2018; 25: e12234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. De Vries K, Plaskota M. Ethical dilemmas faced by hospice nurses when administering palliative sedation to patients with terminal cancer. Palliat Support Care 2017; 15: 148–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Waterfield K, Weiand D, Dewhurst F, et al. A qualitative study of nursing staff experiences of delirium in the hospice setting. Int J Palliat Nurs 2018; 24: 524–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Szarpa KL, Kerr CW, Wright ST, et al. The prodrome to delirium: a grounded theory study. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2013; 15: 332–337. [Google Scholar]