ABSTRACT

During 2018–2019 Israel saw some 4300 measles cases in a country-wide epidemic. Increased measles incidence rates and considerable disease burden have been observed in under-vaccinated communities, predominantly Jewish ultraorthodox. The measles epidemic, despite proper public health handling, revealed susceptible population subgroups as well as gaps and lacking resources in the Israeli public health systems. In the COVID-19 pandemic in Israel, as of December 2020, the number of COVID-19 cases reported nationally was over 300,000 with approximately 3000 fatalities. Notably, minority groups such as the ultraorthodox Jewish community and the Arab community in Israel has been profoundly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. We believe it is still possible to implement the key lessons from the measles outbreak in Israel that could aid in the COVID-19 response in Israel and elsewhere. These conceptions should include a social-based approach, investment in public health human resources and infrastructure, tackling root causes of inequalities, emphasis on trust and solidarity, proactive communication, need for political will, and proper use of epidemiological data as a basis for decision-making. In parallel to proper use of COVID-19 vaccines, when available, a ‘social vaccine’ is crucial as well as preparedness and response according to public health principles.

KEYWORDS: Measles, COVID-19, epidemiology, social medicine, social vaccine, health disparities

Measles epidemiology in the last decade

In 2010, the World Health Assembly (WHA) set a goal of achieving measles control goals by 2015 including a decline in measles incidence and mortality and an increase in vaccination coverage. The global annual incidence of measles cases reported during the years 2000–2017, declined from 145 to 25 cases per million population (about 83% decline).1,2 However, in 2018, many measles outbreaks emerged, in all regions of the world, with over 350,000 confirmed measles cases reported. In 2019, more than 537,000 measles cases were notified in 180 countries, many cases were from large measles outbreaks.1,2 In 2020, a sharp decline in measles incidence has been observed worldwide, with about 79,000 measles cases reported during January to July 2020, with about 67,000 cases during the months January to March 2020 compared to only some 12,000 during the following months April to July 2020.1 In the European Union/European Economic Area countries and the United Kingdom the number of the reported measles cases declined from 710 to 54 between the months January and May 2020. This remarkable decline in measles incidence may be attributed to social distancing recommendations and to various other infection control measures, including lockdowns, aimed at containing the COVID-19 pandemic.3

Israel saw some 4300 measles cases in a country-wide epidemic that spread during 2018–2019. Increased measles incidence rates and considerable disease burden have been observed in under-vaccinated (predominantly Jewish ultraorthodox) communities.4–6 The measles outbreak containment measures necessitated the application of a culture-sensitive approach with community-based campaigns aimed to rapidly increase the measles vaccination coverage.5 The communities affected by 2018–2019 measles outbreak have shown recurrent Vaccine-Preventable Disease outbreaks previously (e.g. measles, mumps), with international transmission occurring between similar communities worldwide (mainly orthodox communities in Europe, UK, and the US).7–9 Studies on assessment of vaccination status among children in Israel, based on the national immunization registry data, showed that the overall average routine vaccination coverage among children is adequate. Overall, the Arab population displays higher routine vaccination coverage rates compared to the Jewish population. However, studies on vaccination timeliness showed that childhood vaccination delays are common in all the population groups, while under-vaccination prevails mainly among children in the Jewish ultraorthodox communities in Israel.7,10

As the measles virus is highly transmissible, measles incidence and outbreaks reflect the combination of inappropriate herd immunity, the impact of vaccine hesitancy, and virus spread owing to the effects of globalization.11 Measles is a Vaccine-Preventable Disease for decades with specific goals set for control and elimination. Since 1960’s, the live attenuated measles vaccines have been available globally. The measles vaccine has been included in the routine immunization schedule in Israel in 1967. Assessment of performance of vaccination programs and estimating gaps in population immunity necessitates determination of the population’s seroprevalence rates against Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. Performing seroprevalence surveys necessitate considerable costs and logistics; moreover, a noticeable variation exists in the definitions and methods of these surveys.12 An age-stratified seroprevalence study in 17 European countries and Australia (published in 2008) estimated measles susceptibility as compared to the WHO European Region targets including: <15% susceptibility among children aged 2–4 years, <10% among 5–9-year-olds, and <5% in the older age groups. Seven countries in the survey were near the targets, four countries (including Israel) had susceptibility levels above the targets, indicating possible gaps and another seven countries showed considerable susceptibility with the risk of epidemics.13 Several studies evaluating young adults' susceptibility (mainly military recruits) in Israel have also shown decreased measles seroprevalence. In a systematic sample of military recruits, only 85.7% were seropositive in 2007, compared to 95.6% in 1996, reflecting suboptimal measles population immunity, after 20 years of a universal two-dose Measles-Mumps-Rubella vaccination schedule in Israel.14 A recent study combined serological and contact data to derive target immunity levels for achieving and maintaining measles elimination. The study findings indicated that a high, 95% immunity level, would have to be achieved among children by the age of 5 years and maintained across older age groups to guarantee elimination.15 Another recent study evaluated the WHO goals for herd immunity against measles and proposed that the desired two-dose measles vaccination coverage should be 97% and levels among children aged 1–9 years should be 95% aiming to achieve measles elimination in Europe.16 Aiming to achieve such high and sustainable immunization coverage targets necessitate considerable investment in public health infrastructure worldwide. In 2015, the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) were adopted by all United Nations member states, toward a vision for a world free from poverty, hunger, and disease by the year 2030. SDG 3 concern health “Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.” Attainment of the other goals is also expected to improve health and promote equity. Universal availability and accessibility to public immunization services are fundamental to achieving the SDGs.17

COVID-19 and measles

According to the World Health Organization data, as of 5th December 2020, COVID-19 cases have been reported from all the regions globally (235 countries, areas, or territories) with over 65 million detected cases and over 1.5 million fatalities.18 The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic has generated a significant socio-economic impact affecting high, middle, and low countries.19 While many high-income countries were profoundly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, the disease spread and consequences may vary between population subgroups. A time-series analysis of cross-national differences in COVID-19 mortality evaluating 84 countries, in the pandemic early phase, has shown that COVID-19 mortality is associated with the country's income inequality and social capital. Social trust and belonging to groups were factors associated with mortality, possibly due to infection spread and inappropriate social distancing.20

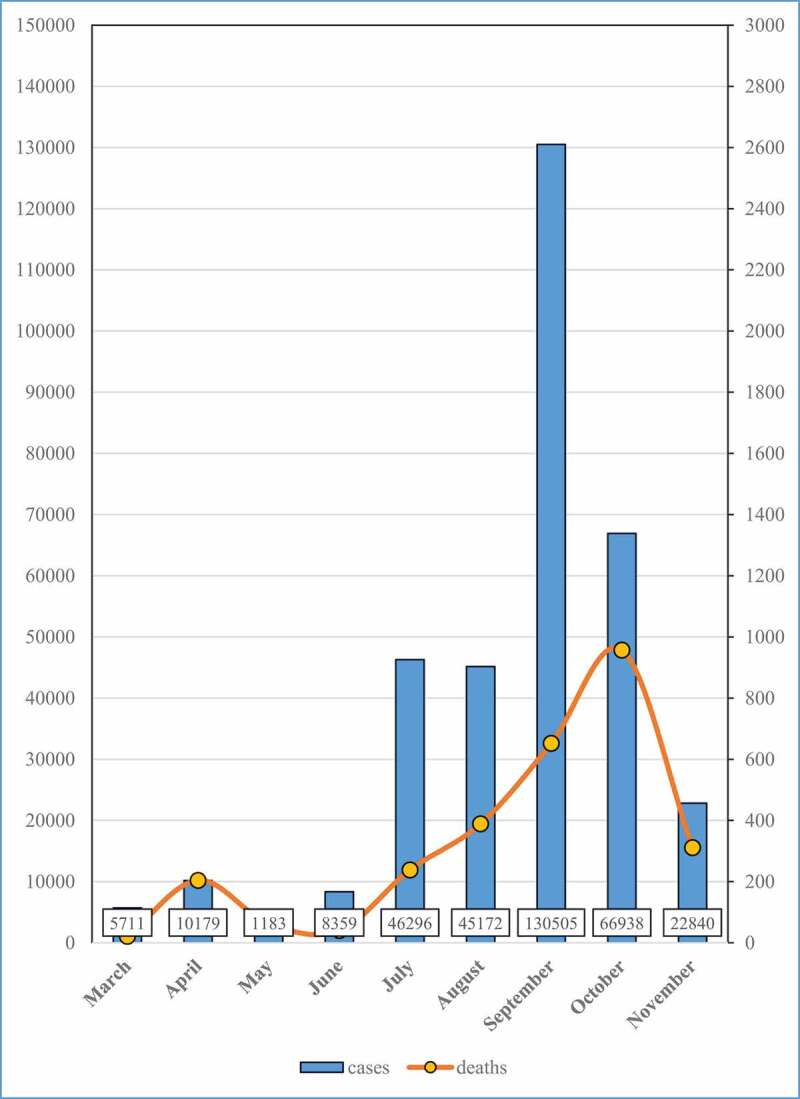

As of 5th December 2020, the number of COVID-19 cases reported in Israel was over 340,000 with 2900 fatalities. Figure 1 exhibits the number of COVID-19 cases and fatalities by month in Israel in 2020; notably, the national number of cases doubled during September 2020 and declined after a second national lockdown in October 2020. In Israel, 9.2 million inhabitants’ country, the main minority groups are the ultraorthodox Jewish community (about 11%) and the Arab population (about 21%). Israel is regarded as a high-income country with a universal health insurance law and advanced health services. The national health policy should consider structural and cultural disparities including the lifestyles and requirements of all population groups.21 In the COVID-19 pandemic in Israel, the ultraorthodox Jewish community has been profoundly affected both in the first (March – April 2020) and the second (July 2020 and ongoing) pandemic “waves” while the Arab community has been under-represented in the first wave with increasing incidence in the second pandemic wave.22–24 The Arab communities showed a marked rise during the second wave mainly due to large social gatherings. Overall, in March – December 2020, the ultraorthodox Jewish community comprised about 28% and the Arab community about 20% of the COVID-19 cases nationally.

Figure 1.

COVID-19 cases (columns) and mortality (line) by month, Israel, March-November 2020

Notably, ultraorthodox Jewish communities affected by the 2018–2019 measles outbreak have been also heavily affected by the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. Possible attributing factors are high population density, low socio-economic level, and large households, increasing the probability of communicable disease transmission.5,7,25 As to households’ size, the total fertility rate in Israel was the highest among Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries in 2016 (3.1), and exceptionally high among ultraorthodox Jews (7.1).26 Neighborhoods and cities with sizable ultraorthodox Jewish population showed a disproportionately increased fraction of the COVID-19 cases.22,24 In the second wave localities, neighborhoods with large Arab populations showed an increased incidence of COVID-19.

The susceptibility of specific communities to communicable disease outbreaks might stem from social determinants of health. These aspects call for a broad, systemic approach enabling better COVID-19 response and better public health protection.27 Regarding underlining disorders that increase the risk for severe COVID-19 disease, disparities as to noncommunicable diseases, with higher rates in low socio-economic groups, have been reported in Israel; sustainable health intervention programs are required to address these social inequalities.28

Another public health feature is the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis on the health system which can interrupt the efforts of routine vaccination campaigns against measles in many countries.29 In that context, the ultraorthodox Jewish population in Israel has previously shown lower childhood vaccination coverage rates, vaccination delay, and increased risk for outbreaks as compared to other population groups.4–7,10,25,30 The role of the community-based child health services and particularly that of the public health nurses are indeed vital in promoting sustainable measles immunization coverage.31 Therefore, the preventive child health services should be given substantial support and proper budgeting in order to assure coping with the increase in the population of children and the requirements of special population groups.32,33Similarly, Jewish ultraorthodox communities in the US have been previously affected by vaccine-preventable diseases such as measles and mumps.8,9 Neighborhoods with large orthodox Jewish communities have been also heavily affected by the COVID-19 pandemic in NY.34 A paper reflecting on measles as a metaphor and the meaning of resurgence for the future of immunization include recommendations to use data, not outbreaks, to identify vulnerable communities.35

The lesson is that in parallel with the quest for a vaccine against COVID-19 and immunization campaigns with a special focus on the most vulnerable populations, we need to use ‘social vaccine,’ meaning to encourage action on the distal social and economic determinants of health with a focus on the needs of the people.36 Against this background, we propose seven key lessons from the measles outbreak in Israel, which could aid in proper COVID-19 response, including in a successful immunization campaign (Table 1). Implementing these lessons would aid in tackling better the pandemic and in the prevention of pandemic fatigue.37 Unfortunately, even during an ongoing pandemic, we are still facing the ‘prevention paradox,’ and too often fail to focus on population-based interventions, primary prevention, and controlling distal risks to health.38 In that sense, we have to verify that technology does not eclipse public health, as technology is only a tool, while there is no public health without the public.

Table 1.

Key lessons from the measles outbreak in Israel for the COVID-19 pandemic response and vaccination program

| 1. Health promotion, social-based approach together with communities, tailored to population needs. |

| 2. Proper ongoing investment in public health human resources, according to population needs. |

| 3. Tackling the root causes of inequalities: education, employment, access to health care. |

| 4. Emphasis on trust and solidarity, rather than a biological notion -’ Social vaccine’ |

| 5. Transparent communication, culturally appropriate, with the people, by the people |

| 6. Political will and leadership for the protection of public health is essential, against competing interests. |

| 7. Decision-making based on surveillance and epidemiology at the local, regional, and national levels. |

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No, potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Measles and rubella surveillance data. [accessed 2020 Dec 5]. https://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/burden/vpd/surveillance_type/active/measles_monthlydata/en/

- 2.Strebel PM, Orenstein WA.. Measles. N Engl J Med. 2019. July 25;381(4):349–57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1905181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicolay N, Mirinaviciute G, Mollet T, Celentano LP, Bacci S. Epidemiology of measles during the COVID-19 pandemic, a description of the surveillance data, 29 EU/EEA countries and the United Kingdom, January to May 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020. August;25:31. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.31.2001390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stein-Zamir C, Abramson N, Shoob H. Notes from the field: large measles outbreak in orthodox Jewish communities - Jerusalem District, Israel, 2018-2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020. May 8;69(18):562–63. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6918a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stein-Zamir C, Abramson N, Edelstein N, Shoob H, Zentner G, Zimmerman DR. Community-oriented epidemic preparedness and response to the Jerusalem 2018-2019 measles epidemic. Am J Public Health. 2019. December;109(12):1714–16. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ben-Chetrit E, Oster Y, Jarjou’i A, Megged O, Lachish T, Cohen MJ, Stein-Zamir C, Ivgi H, Rivkin M, Milgrom Y, et al. Measles-related hospitalizations and associated complications in Jerusalem, 2018-2019. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020. May;26(5):637–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stein-Zamir C, Israeli A. Timeliness and completeness of routine childhood vaccinations in young children residing in a district with recurrent vaccine-preventable disease outbreaks, Jerusalem, Israel. Euro Surveill. 2019. February;24(6):1800004. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.6.1800004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zucker JR, Rosen JB, Iwamoto M, Arciuolo RJ, Langdon-Embry M, Vora NM, Rakeman JL, Isaac BM, Jean A, Asfaw M, et al. Consequences of under vaccination - measles outbreak, New York City, 2018-2019. N Engl J Med. 2020. March 12;382(11):1009–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1912514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barskey AE, Schulte C, Rosen JB, Handschur EF, Rausch-Phung E, Doll MK, Cummings KP, Alleyne EO, High P, Lawler J, et al. Mumps outbreak in orthodox Jewish communities in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2012. November 1;367(18):1704–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stein-Zamir C, Israeli A. Age-appropriate versus up-to-date coverage of routine childhood vaccinations among young children in Israel. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017. September 2;13(9):2102–10. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2017.1341028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feemster KA, Szipszky C. Resurgence of measles in the United States: how did we get here? Curr Opin Pediatr. 2020. February;32(1):139–44. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dimech W, Mulders MN. A 16-year review of seroprevalence studies on measles and rubella. Vaccine. 2016. July 29;34(35):4110–18. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andrews N, Tischer A, Siedler A, Pebody RG, Barbara C, Cotter S, Duks A, Gacheva N, Bohumir K, Johansen K, et al. Towards elimination: measles susceptibility in Australia and 17 European countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2008. March;86(3):197–204. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.041129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levine H, Zarka S, Ankol OE, Rozhavski V, Davidovitch N, Aboudy Y, Balicer RD. Seroprevalence of measles, mumps and rubella among young adults, after 20 years of universal two-dose MMR vaccination in Israel. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2015;11(6):1400–05. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1032489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Funk S, Knapp JK, Lebo E, Reef SE, Dabbagh AJ, Kretsinger K, Jit M, Edmunds WJ, Strebel PM. Combining serological and contact data to derive target immunity levels for achieving and maintaining measles elimination. BMC Med. 2019. September 25;17(1):180. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1413-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plans-Rubió P. Are the objectives proposed by the WHO for routine measles vaccination coverage and population measles immunity sufficient to achieve measles elimination from Europe?. Vaccines (Basel). 2020. May 13;8(2):218. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8020218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan M, Elias C, Fauci A, Lake A, Berkley S. Reaching everyone, everywhere with life-saving vaccines. Lancet. 2017. February 25;389(10071):777–79. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30554-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization . Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. [accessed 2020 Dec 5]. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus–2019

- 19.Keni R, Alexander A, Nayak PG, Mudgal J, Nandakumar KCOVID. 19: emergence, spread, possible treatments, and global burden. Front Public Health. 2020. May 28;8:216. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elgar FJ, Stefaniak A, Wohl MJA. The trouble with trust: time-series analysis of social capital, income inequality, and COVID-19 deaths in 84 countries. Soc Sci Med. 2020. September;16:113365. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waitzberg R, Davidovitch N, Leibner G, Penn N, Brammli-Greenberg S. Israel’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic: tailoring measures for vulnerable cultural minority populations. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19:71. doi: 10.1186/s12939-020-01191-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Birenbaum-Carmeli D, Chassida J. Covid-19 in Israel: socio-demographic characteristics of first wave morbidity in Jewish and Arab communities. Int J Equity Health. 2020. September 9;19(1):153. doi: 10.1186/s12939-020-01269-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saban M, Myers V, Wilf-Miron R. Coping with the COVID-19 pandemic - the role of leadership in the Arab ethnic minority in Israel. Int J Equity Health. 2020. September 9;19(1):154. doi: 10.1186/s12939-020-01257-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schattner A, Klepfish A. Orthodox Judaism as a risk factor of covid-19 in Israel. Am J Med Sci. 2020. September;360(3):304. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2020.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salama M, Indenbaum V, Nuss N, Savion M, Mor Z, Amitai Z, Yoabob I, Sheffer RA. Measles outbreak in the Tel Aviv District, Israel, 2018–2019. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. July 3:ciaa931. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ben David D, Overpopulation and demography in Israel: directions, perceptions, illusions and solutions. Shoresh Institute Policy Report; 2018. November. https://shoresh.institute/publications.html

- 27.Offline HR. COVID-19 is not a pandemic. Lancet. 2020. September 26;396(10255):874. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32000-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muhsen K, Green MS, Soskolne V, Neumark Y. Inequalities in non-communicable diseases between the major population groups in Israel: achievements and challenges. Lancet. 2017. June 24;389(10088):2531–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30574-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guha-Sapir D, Moitinho de Almeida M, Keita M, Greenough G, Bendavid E. COVID-19 policies: remember measles. Science. 2020. July 17;369(6501):261. doi: 10.1126/science.abc8637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stein Zamir C, Knowledge IA. Attitudes and perceptions about routine childhood vaccinations among Jewish ultra-orthodox mothers residing in communities with low vaccination coverage in the Jerusalem District. Matern Child Health J. 2017. May;21(5):1010–17. doi: 10.1007/s10995-017-2272-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elran B, Yaari S, Glazer Y, Honovich M, Grotto I, Anis E. Parents’ perceptions of childhood immunization in Israel: information and concerns. Vaccine. 2018. December 18;36(52):8062–68. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.10.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rubin L, Belmaker I, Somekh E, Urkin J, Rudolf M, Honovich M, Bilenko N, Grossman Z. Maternal and child health in Israel: building lives. Lancet. 2017. June 24;389(10088):2514–30. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30929-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zimmerman DR, Verbov G, Edelstein N, Stein-Zamir C. Preventive health services for young children in Israel: historical development and current challenges. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2019. February 7;8(1):23. https://coronavirus.health.ny.gov/home [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koh HK, Gellin BG. Measles as metaphor—what resurgence means for the future of immunization. JAMA. 2020;323(10):914–15. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baum F, Narayan R, Sanders D, Patel V, Quizhpe A. Social vaccines to resist and change unhealthy social and economic structures: a useful metaphor for health promotion. Health Promot Int. 2009. December;24(4):428–33. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dap026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.[accessed 2020 Dec 5]. https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/publications-and-technical-guidance/2020/pandemic-fatigue-reinvigorating-the-public-to-prevent-covid-19,-september-2020-produced-by-whoeurope.https://www.who.int/whr/2002/chapter6/en/index1.html