ABSTRACT

Healthcare providers (HCPs) are at the frontline to curb the spread of vaccine hesitancy in the community. However, HCPs themselves may delay or refuse vaccines. In light of the emerging vaccine hesitancy in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), we aimed to explore HCPs doubts and concerns regarding vaccination. We conducted face-to-face interviews with 33 HCPs from 7 ambulatory healthcare services in the Al Ain region, UAE. An interview guide was developed based on the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control guide for vaccine hesitancy among HCPs. An inductive thematic framework was employed to explore the main and emerging themes conceptualizing the predisposing, reinforcing, and enabling factors that influence HCPs’ hesitancy regarding vaccinations for themselves and while recommending, prescribing, or discussing vaccines with their patients. The sample included general practitioners, family physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and other administrative staff. The major themes included positive predisposing factors such as trust in the system and the government, previous education, and social responsibility. Positive enabling factors included affordability and availability of vaccination services. Many participants were hesitant to receive the mandatory influenza vaccination. Misinformation regarding vaccines on social media was a major concern. However, HCPs showed little interest in being active on social media. Most participants reported never receiving any training on how to address vaccine hesitancy among patients. Because HCPs play an important role in influencing patients’ decisions regarding undergoing vaccination, their confidence in addressing vaccine hesitancy must be improved.

KEYWORDS: Healthcare workers, vaccine hesitancy, United Arab Emirates, social media, influenza vaccine

Introduction

Vaccine hesitancy is an emerging healthcare challenge in the 21st century and has been declared one of the most important threats to global health by the World Health Organization.1 Healthcare providers (HCPs) work at the frontline to curb the spread of vaccine hesitancy in the community. Opel et al. (2013) described a robust association between parental vaccine acceptance and how HCPs initiate and pursue vaccine recommendations.2 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has established guidelines for HCPs regarding communication with parents about vaccination; these guidelines also stress the importance of the roles of HCPs in vaccination acceptance.3 Nevertheless, many studies worldwide have revealed a pattern of reluctance to immunization among HCPs. A qualitative study conducted by the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) that investigated vaccine hesitancy among HCPs in Croatia, France, Greece, and Romania confirmed the presence of vaccine hesitancy among HCPs. The most common concerns included vaccine efficacy, side effects of certain vaccines, and issues of trust and mistrust. Most HCPs reported being influenced by their healthcare departments, pharmaceutical representatives, and medical journals.4 A cross-sectional survey conducted in France that investigated vaccination practices and attitudes among general practitioners (GPs) found that most GPs who were interviewed disagreed with statements regarding the safety of vaccines, and their behavior recommendations were tailored by their beliefs regarding vaccinations.5 Another study in Hungary that explored vaccine hesitancy among HCPs reported findings similar to those of the ECDC study; they noted that Bacillus Calmette–Guérin was the least supported vaccine and that the highest hesitancy rates were reported for MMR.6

Few studies have addressed this issue in the Arab region. A cross-sectional study conducted in Dubai, United Arab Emirates (UAE), identified some hesitancy toward the influenza vaccine for reasons associated with its safety, efficacy, and side effects among primary HCPs practicing in facilities under the Dubai Health Authority.7 Despite having vaccine coverage estimates above 95% for most childhood vaccines, the Department of Health in Abu Dhabi, UAE, was notified of 4290 cases of chickenpox, 1244 cases of hepatitis B, 57 cases of measles, and 227 cases of mumps in 2018.8,9 Moreover, we recently reported that 12% of parents in the Al Ain region, UAE are vaccine-hesitant according to an Arabic version of the Parent Attitudes about Childhood Vaccines survey.10 Most surveyed parents indicated almost complete trust in their child’s doctor. In light of the emerging vaccine hesitancy in the UAE, exploring the factors that influence vaccine hesitancy among HCPs is essential. Furthermore, understanding how HCPs communicate with vaccine-hesitant individuals and communities will inform decision makers about the best strategies for addressing vaccine hesitancy.

The ECDC has addressed vaccine hesitancy among HCPs using a qualitative approach.4,11,12 They have attempted to understand HCPs’ concerns regarding vaccinations and the reasons for vaccine hesitancy in Europe. Using a similar approach, this study aims to explore the doubts and concerns of HCPs regarding vaccination (vaccine hesitancy), identify the reasons for vaccine hesitancy among HCPs in the UAE, and investigate how HCPs respond to vaccine-hesitant individuals and communities.

Materials and Methods

Study design

A qualitative study utilizing semi-structured face-to-face interviews was selected because of its appropriateness for exploring beliefs about vaccination and understanding the role of HCPs in the fight against vaccine hesitancy in the community. This study adheres to the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research guidelines.12

Research team and reflexivity

Interviews were conducted by the first author (I.E., female/PhD/senior researcher). I.E had received training in qualitative studies and was experienced in conducting face-to-face interviews with members of the community and healthcare sector. All authors were aware of their positions and reflected on how these could affect the study design, conduct, and analysis of the results. The corresponding author (A.R.A.) leads the UAE National Immunization Technical Advisory Group and as such could be considered an advocate for vaccination. Thus, biases may have influenced how the data were interpreted.

Study setting

This study investigated HCPs working in the ambulatory healthcare services (AHS) in the Al Ain region of the Emirate of Abu Dhabi, UAE. The Al Ain region is a large inland oasis located in the eastern part of Abu Dhabi along the border of Oman. It had an estimated population of 766,936 in 2020.13 The AHS are government primary healthcare clinics that operate under Abu Dhabi Health Services Company (SEHA), UAE. All HCPs receive mandatory vaccinations for employment and for contract renewals in addition to an annual dose of the influenza vaccine. The HCP immunization policy includes three doses of the hepatitis B (HB) vaccine for HCPs who have anti-HB titers less than 10 IU/mL; two doses of MMR if they have no serologic evidence of immunity or prior vaccination; two doses of the varicella vaccine for HCPs who have no serologic proof of immunity, prior vaccination, or history of varicella disease; and one dose of Tdap for HCPs who have not received Tdap previously (Preventive Medicine Department, Ministry of Health and Prevention, UAE).

Selection of participants

Purposive and convenience sampling was used to recruit 35 participants. The research participants were defined as HCPs who are involved in recommending, scheduling, or administering vaccines to any population including children and adults and who were working at the seven selected AHS clinics during the study period (October to December 2019). AHS clinics that provided vaccination services and included both urban and rural areas in the Al Ain region were selected. HCPs who agreed to participate and provided consent were included in the study. All participants were interviewed in a private room after consenting to participate. AHS managers facilitated our study by providing us with rooms and necessary support. Explanations regarding this study were given to the participants verbally and in written format. We aimed to recruit five participants from each clinic. Our sample size was 33 participants at the end of the data collection period.

Interview topic guide

The topic list for the interviews was developed and structured using the ECDC interview guide for vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers after adapting it to the UAE context. The ECDC interview guide includes questions that explore HCPs’ attitudes toward vaccination, their concerns, and their decisions to vaccinate or advise their patients and how to communicate with hesitant individuals.4,11 For the purpose of this study, the interview guide was translated into Arabic when interviewing Arabic-speaking HCPs. Additionally, we included a question about nationality, and if the participant was non-Emirati, we recorded the number of years that they had been practicing in the UAE (Supplementary Material).

Data collection

The interviews lasted 25–35 min. All the interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. The transcripts and field notes were reviewed and analyzed by the leading researchers. The interviewer was aware that both pro- and anti-vaccination beliefs were likely to be raised by the participants, and as such, she encouraged the participants to discuss their views freely.

Data analysis

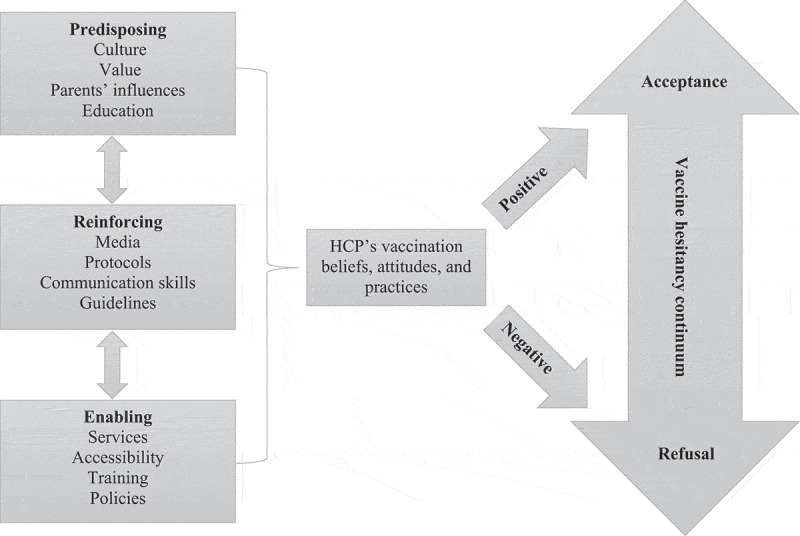

An inductive thematic framework was employed to explore the main themes and emerging themes across all interviews by conceptualizing the predisposing, reinforcing and enabling factors (PREs) of behavior shaping. The PRE constructs of the evaluation section of the PRECEDE-PROCEED model of designing health promotion programs were adapted as our guide and framework for coding the themes (Figure 1).14 This model has previously been used in vaccination research to study vaccination beliefs and behaviors and identify barriers to and facilitators of immunizations among various populations, including HCPs.15,16 All interviews were transcribed, translated into English (if conducted in Arabic), and then analyzed thematically by categories based on recurring themes in the interviews and based on our interview guide questions and study aims. All themes were coded separately and entered as free text in the codebook with quotes from participants. We categorized all themes in the codebook under the main three factors (PRE). Predisposing factors include knowledge, beliefs, values, attitudes, and self-efficacy; these factors can be considered motives for certain behaviors. Reinforcing factors include peer pressure, media, and social pressure; these factors serve as incentives that increase people’s probability of adopting a behavior. Enabling factors include skills, resources (e.g., training), and access, which serve as facilitators for a particular behavior.16 The codes were then classified as negative and positive to imply their effect on behavior. The themes were revised multiple times until the research team reached a consensus. The identified themes present factors that influence HCPs’ vaccine practices and how these practices may impact their communication with vaccine-hesitant patients and families.

Figure 1.

Adapted version of the predisposing, reinforcing and enabling factors of behavior shaping in the evaluation section of PRECEDE-PROCEED Model; adapted from Green LW, Kreuter MW, Deeds SG, Partridge KB, Bartlett E. Health education planning: a diagnostic approach. Palo Alto, California, Mayfield Publishing, 1980.; n.d

Ethical considerations

Ethics approval was obtained from the AHS Human Research Ethics Committee at SEHA.

Results

Interviews with 33 participants were completed. We aimed to interview HCPs from different parts of Al Ain region; thus, we continued recruitment to reach our target of five HCPs from each clinic even though saturation was reached by recruiting almost half the sample.

Some HCPs from the clinics refused to participate because of the workload and time commitment. The researchers had to visit the clinics many times to reach the target number from each clinic. Two HCPs refused to participate because of their anti-vaccination beliefs, which they explicitly declared. The final sample of 33 HCPs included GPs, family physicians, residents, interns, nurses, pharmacists, a physiotherapist, a radiographer, a dietitian, and other administrative staff (Table 1). In the UAE, physicians and nurses are actively involved in providing vaccination services in well-baby clinics, during school health visits, and at premarital screening programs. Although other allied HCPs such as dieticians and physiotherapists are not directly involved in vaccine administration, they are usually in contact with patients and may engage in vaccine discussion and recommendations. Furthermore, clinic administrators such as clerks and patient relation officers are usually involved in scheduling immunization appointments, sending reminder calls, and resolving social and administrative problems of patients and families. This type of communication may result in discussions regarding vaccination. Because this is an exploratory study, we decided not to exclude this group from our analysis. Moreover, allied HCPs working at the selected AHS centers are obliged to receive the influenza vaccine. One-third of the participants were Emirati nationals, primarily doctors, and the remaining two-thirds were expatriates from the Philippines, India, Pakistan, and other Arab countries (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics (n [%] or as stated otherwise) *

| Sex (female) | 26 (78.7) |

| Age (range) | 24–58 years |

| Duration of practice (range) | 1–25 years |

| Profession | |

| Nurse | 14 (42) |

| Physician (including one intern and two residents) | 11 (33) |

| Administrative | 3 (9) |

| Pharmacist | 2 (6) |

| Dietitian | 1 (3) |

| Lab technician | 1 (3) |

| Radiographer | 1 (3) |

| Nationality | |

| Emirati | 12 (36.36) |

| Non-Emirati Philippines India Jordan Egypt Sudan Oman Somalia Pakistan Syria |

21 (63.64) 5 5 3 2 2 1 1 1 1 |

| Practicing alternative medicine | 0 (0) |

| Alternative medicine for personal use | 2 (6) |

*Thirty-three healthcare providers from seven ambulatory healthcare services in Al-Ain region, UAE were assessed; Clinic A (4), Clinic B (4), Clinic C (5), Clinic D (5), Clinic E (4), Clinic F (6), Clinic G (4), and Clinic H (5).

The themes extracted from the interviews were categorized as major themes, subthemes, and emerging themes. Although most of the studied HCPs indicated compliance with vaccination recommendations for their children, patients, and themselves (e.g., influenza vaccine), some participants had negative views on vaccination, raising concerns about the existence of some degree of vaccine hesitancy. For instance, nearly all participants voiced concerns regarding the requirement to undergo mandatory influenza vaccination and the potential side effects. Most participants declared that if given the choice, they would not receive the influenza vaccine. Furthermore, one participant voiced concerns regarding pharmaceutical companies and the propagation of unnecessary vaccines despite complying with the recommended vaccination schedule for her child.

One nurse (HCP-MU-51) stated that “if time goes back, I will not vaccinate my child.” She also discussed how she has changed her lifestyle by using alternative medicine and following a vegan diet. She claimed that she is very comfortable with this lifestyle and feels that her health has improved.

A family physician (HCP-JA-52) mentioned some concerns about a few vaccines being unnecessary. She also stated, “I follow a healthy lifestyle; avoid dairy products, and I am more careful about diet and lifestyle.”

Almost all participants agreed that they had not received sufficient training on how to address vaccine hesitancy among patients even though most participants indicated that they have access to information about vaccination from the SEHA and the Department of Health in Abu Dhabi. However, most mentioned the lack of sufficient training and efforts to educate people about vaccination in clinics.

Table 2 summarizes the major themes based on PRE factors that shape HCP attitudes toward vaccination and their practices with their patients. We classified the themes as positive and negative influencers.

Table 2.

Major themes and subthemes influencing HCPs’ perceptions and attitudes toward vaccines and vaccination communication

| Predisposing factors | Culture Value Education System |

Positive |

Negative |

| Medical education Trust in the system Parents’ prior experience Religious and cultural beliefs Social responsibility |

Lack of sufficient information and background Lack of trust in HCPs’ vaccination competency Misinformation Traditions: arranged and family marriages Fear of side effects |

||

| Reinforcing factors | Protocols Guidelines Communication skills Media |

HCPs as role models Trustworthy sources of information are available Paternalistic approach Trust and acceptance of physicians’ instructions in the UAE |

Social media HCPs are not very active on social media themselves as educators and influencers. Lack of engagement in vaccine hesitancy issues HCPs do not believe that there are any issues with vaccination in the UAE. |

| Enabling factors | Services Policy Accessibility Training |

Affordability and availability of the vaccination services Immunization policies Management of side effects Follow-up of defaulters Premarital examination and well-baby clinics Job requirements |

Own hesitancy (influenza vaccine) Lack of training Insufficient information for HCPs in Arabic |

Predisposing factors

Major positive themes

Predisposing factors include knowledge gained from formal education and social interactions, including knowledge from parents, grandparents, society, and from their education as HCPs.

Many HCPs agreed that social and local demographics are crucial indicators of the importance of immunization; this is highlighted when comparing the life expectancy of their ancestors and the current life expectancy and health of people in the UAE. For example, one HCP (HCP-JA-54) stated “My mother followed all the recommendations long time ago in terms of my own immunization and for my sibling’s immunization; definitely, I will do what my mother did.” This belief was prevalent among most participants, except for a few, who doubted the importance of all vaccinations, such as that for rotavirus; similarly, nearly 50% of the participants believed that the influenza vaccine is given to them unnecessarily.

Another important predisposing factor positively affecting vaccination practice and advice was “social responsibility”. Many participants indicated that adherence to vaccination falls under social responsibility and building a better future for their children.

A predisposing theme that was also very common among most participants (no difference among nationalities) was trust in the country’s leaders and policymakers. This includes trust in local and western healthcare systems, doctors, the government, and the vaccination program in the UAE.

Another positive influence on HCPs’ adherence to vaccination was the participants’ cultural and religious beliefs, which usually promote people’s responsibility for their health. One of the participants indicated how her faith recommends taking necessary precautions to prevent diseases. Most participants noted their religious beliefs when discussing the importance of protecting lives through vaccination.

Major negative themes

The HCPs perceived the presence of negative influence and pressure from parents and grandparents on the patient population. For example, some grandparents might try to encourage their children and grandchildren to not be vaccinated by using themselves as examples and indicating that nothing happened to them even though they were not vaccinated. Another cultural factor is the common occurrence of arranged and family marriages in the Al Ain area, which might affect the vaccination procedure. A nurse who worked in a premarital screening program explained that they must postpone administering MMR shot if a woman’s wedding is imminent to avoid any possibility of the woman becoming pregnant quickly after marriage. In such cases, they advise the woman to return after the birth of her first child to receive the MMR booster. This nurse indicated that she had to counsel couples and families about the importance of vaccination, particularly for MMR.

Another negative factor mentioned by some participants was the lack of trust in the abilities of some HCPs to administer vaccines. A nurse from outside Al Ain city (HCP-HL-51) stated “I am late with my daughter’s vaccination because I want to bring her to my clinic and give her the vaccine myself. I don’t trust giving her the vaccine in my own city … ”.

Another important theme identified was the fear of side effects and presence of certain health problems. One participant indicated that she received many questions from people about the side effects of MMR, particularly if they have young children. Other HCPs indicated that they were late in terms of many vaccinations for their children because their children had certain medical conditions and the fear of causing side effects. When asked if any vaccines were unnecessary, some participants indicated that the rotavirus vaccine is unnecessary and that children are already receiving many vaccines. Another HCP indicated that it is sometimes better to not give the vaccines all at once to avoid side effects and fever.

The last negative theme was misinformation and wrong messages sent through social media, which negatively influences beliefs and attitudes toward vaccination in general.

Reinforcing factors

Major positive themes

Major positive reinforcing themes included positive influence from other HCPs and colleagues as role models. However, when we asked the participants whether they knew if any of their colleagues were vaccine-hesitant, most replied negatively. This indicates a high level of professionalism and a separation between beliefs and practices. HCPs might influence one another and serve as role models in terms of vaccination. Another important theme was the availability of appropriate sources of information through their employer and through government departments. In the UAE, people are raised on the paternalistic approach of trusting and accepting physicians’ instructions with no discussion. This approach has been very helpful in people’s adherence to vaccination because HCPs are the first source of trust for them. This also indicates that medical professionals’ circles of family and friends are usually influenced by their beliefs and advice. This theme was reinforced by most participants, who stated that their advice and education have greatly influenced other people’s acceptance of vaccination, although some remained doubtful.

One of the nurses (HCW-HL-51) stated, “I had so many patients who were challenging me that MMR can cause autism. Almost all were convinced to give the vaccine to their children after I educated them”.

Major negative themes

Negative reinforcing factors included the influence of social media and influencers, which is growing in the UAE and affects a large proportion of the population. Unfortunately, the HCPs indicated that they are not active on social media themselves for many reasons, including lack of time, job restrictions, and lack of trust in their self-efficacy as good communicators. One participant (HCP-HL-52) stated, “On my child parents’ WhatsApp group, I found out a lady who was providing misinformation about vaccination and specifically on MMR and autism. I tried to explain to her that this is wrong and discussed it with her on the group. She was not convinced. Until today, she did not vaccinate her children. I could not convince her, and she is influencing other parents.” However, some participants were not aware that people may have concerns about a relationship between MMR and autism indicating the lack of engagement in vaccine hesitancy issues.

Enabling factors

Major positive themes

We identified several enabling factors, including affordability, availability, and accessibility to vaccination; immunization laws (e.g., mandatory influenza vaccination and preschool immunization certificate); side effects management and education; available information for HCPs on the SEHA website, CDC, and other reliable sources; follow-up of defaulters; premarital screening clinics; well-baby clinics; and fear of losing a job. Almost all participants agreed that people in the UAE are lucky because childhood vaccination is provided to everyone, is available and affordable, and that defaulters are always followed up and encouraged to adhere to vaccination protocols. Nearly all participants agreed that the policies in the UAE are very supportive of vaccination. One participant provided an example and stated that the new policies do not allow children to enroll in school without a certificate of complete immunization.

Some participants also pointed out the available intensive education that is provided by premarital clinics, obstetrics clinics, well-baby clinics, and pediatric clinics. Some participants indicated that they undergo health education sessions on a periodic basis and that vaccination is always discussed. Most of the participants indicated that receiving the influenza vaccine annually is one of their key performance indicators. If they do not receive it, they risk losing their jobs. Although most participants noted that they would not take the influenza vaccine if given the choice because they do not view it as highly protective, many noted that they give the influenza vaccine to their family members, particularly the older and younger members. Finally, there was almost universal agreement among the participants that the appropriate management of side effects and available education and proper measures are highly encouraging for people to adhere to vaccination.

Major negative themes

The negative enabling themes included the “safety of vaccines”, particularly for certain vaccinations (influenza vaccine); the “lack of resources” and available information on vaccination in Arabic; and the “lack of training” for HCPs on how to address vaccine hesitancy and on the proper communication styles.

A pharmacist (HCW-SU-53) discussed how they educate their patients: “We seek our information from scientific journals … and we give information about vaccination in clinic, … I teach every patient about the vaccination they receive; side effects and we ask them to wait for a while to ensure no immediate side effects … ”. The participant then mentioned that additional seminars should be conducted, and education should be provided to upgrade the information provided to pharmacists and nurses about vaccinations and how to discuss vaccinations with clients.

One nurse (HCW-SW-54) discussed the role of schools as an important organization in providing education about vaccination and helping decrease vaccine hesitancy. He suggested that education and resources should be provided in different languages to ensure that all UAE residents receive the correct information.

Emerging themes

As shown in Table 3, the interviews also identified some emerging themes, including the HCP’s role, trust, and self-efficacy; importance of education and communication skills; and their belief and attitude that there is no vaccine hesitancy in the UAE. The interviews identified an important sub-theme regarding the role of HCPs; a feeling of powerlessness from perceiving their role as existing only in the clinic and within their job description was noted.

Table 3.

Emerging themes influencing HCPs’ perceptions and attitudes toward vaccines and vaccination communication

| Trust and self-efficacy | Trust in their abilities to educate and communicate |

| Job requirement | No time to educate |

| Communication | No communication training and skills to educate vaccine hesitant patients |

| Lifestyle and vaccine hesitancy | HCPs who adhered to a vegan diet exhibited some hesitancy regarding vaccines |

| Role Powerlessness |

The role of HCPs in improving vaccination in the UAE is not clear for most HCPs; they believe that it is the role of the policymakers |

For example, one nurse (HCP-YA-51) stated that “If we have a problem … we have to go to our in-charge, she will encourage us and then we build a plan regarding that … ”. The same nurse recommended that the Department of Health should establish a plan to improve vaccination and train HCPs to educate the community and patients.

It was evident that many HCPs were concerned that social media might have a strong influence on people’s attitudes; however, they believed that policymakers are responsible for addressing this issue. Furthermore, there were concerns about a lack of training for HCPs to adequately address vaccine hesitancy among patients and the community. Based on the interviews, we can conclude that most interviewed HCPs did not believe that vaccine hesitancy is an issue in the UAE, which likely indicates their lack of interest in reading and looking for more information on the issue. Most indicated that they are involved in educating and promoting vaccination in their clinics, but they clearly did not consider themselves responsible for educating the public and their communities.

Discussion

This study is the first to explore HCPs’ views, beliefs, and understanding of vaccine hesitancy using a qualitative approach in the UAE. Many studies worldwide have recognized the important role of HCPs in improving vaccine uptake among community and patients.2,17,18 Moreover, previous studies have identified different factors that may affect vaccine hesitancy among different community groups including the beliefs of HCPs, which may affect their practices and the advice they provide to patients and the community.4,19

Consistent with our earlier findings among parents in the UAE,10 we noted that many HCPs have encountered patients and parents who refused or delayed MMR vaccination claiming links to autism, which they learned about from social media and through social media influencers. Moreover, this study indicated that HCPs’ confidence in their abilities and their self-efficacy to discuss vaccine hesitancy among clients is not strong. HCP communication skills were identified as a highly important factor for improving vaccine uptake when discussing vaccine hesitancy issues with parents.2 Self-efficacy is another factor that was identified by Henrikson et al. that can be improved in physicians when providing training on communication skills to reduce vaccine hesitancy.20,21 McRee et al. also argued that improving self-efficacy among HCPs will improve vaccination uptake.22

We identified different factors that may influence vaccine hesitancy and vaccine uptake in the UAE. The PRE factors that were used in this study’s analysis have identified factors that may be used by policy makers to plan intervention programs to address vaccine hesitancy in the country. Positive factors such as availability, accessibility, and affordability of vaccination were identified as enabling factors for people to receive vaccinations or provide vaccinations to their children. Predisposing factors of values, culture, religion, and previous knowledge and education were also identified to be positively predisposing for vaccine uptake and for the enhancement of vaccination practices in the country. While some grandparents might play a negative role in terms of discouraging their children and grandchildren from receiving vaccinations, many HCPs identified the positive role of family education, knowledge, and practices to improve vaccination in the UAE. Kestenbaum and Feemster discussed different factors such as religion, trust, the role of health professionals, and the public health system in addressing vaccine hesitancy.23 In a study by Elbarazi et al. (2017), religious and cultural beliefs were singled out as strong influencers on Emiratis’ perceptions and health value beliefs. These beliefs may strongly affect HCPs’ advice regarding vaccination.24 The reinforcing factors identified in this study include social media influencers and health care policies and guidelines that may affect vaccination uptake. In this study, similar concepts and factors emerged, showing that trust in the health care system and other factors such as social norms, parenting and values, and religious beliefs have important roles in addressing vaccine hesitancy in the UAE. The interviewed HCPs displayed powerlessness in terms of their self-ability to address vaccine hesitancy in the country. The HCPs’ powerlessness was mainly based on their limited knowledge on communication and their beliefs that vaccine hesitancy is not an issue in the UAE. Additionally, their powerlessness resulted from their overall dependence on the health system, which is a significant enabler for vaccination uptake. However, it was clear that their role in promoting vaccine hesitancy was not well identified, and their overall role in health care was limited to their job description in the sector where they work. For example, when some of them were asked if they are active on social media or if they promote vaccination within their social circle and community, many denied such involvement in community awareness, particularly for promoting vaccination.

Media platforms (including social media) have been enormously influential in the spread of vaccine hesitancy. According to an editorial by the Lancet, the main reason for vaccine hesitancy is misinformation.25 In their reviews, Dubé et al. stressed the importance of social media for improving public health because it is a very important platform for anti-vaxxers. They also stressed the importance of tailoring public health interventions to meet specific concerns and needs.26,27 Our study indicates that the role of HCPs should extend beyond being in the clinic to address the issue of vaccine hesitancy as equally important to other public health interventions. Improving the communication skills and abilities of HCPs to address vaccine hesitancy in the clinic and in the community is essential to address this public health threat.

Another important finding of this study is the attitude of HCPs toward the influenza vaccine. It was obvious from most participants that there was a strong hesitancy/reluctance toward influenza vaccination. Most of the participants indicated their unwillingness to take the vaccine if it was not mandatory. This finding indicates that HCPs are not immune to vaccine hesitancy, particularly when describing their reasons for wanting to reject the influenza vaccine. Some of these reasons are their beliefs that it is not protective and that it might be pushed by pharmaceutical companies. Notably, two HCPs who showed some degree of vaccine hesitancy indicated personal use of alternative medicine such as herbs and dietary restrictions. This finding is consistent with the ECDC report on vaccine hesitancy among HCPs in Europe in which four healthcare workers preferred natural alternatives such as nutrition, rest, and homeopathy to vaccines.11 Further exploration of this relationship is necessary, particularly with the increasing trend in adopting veganism among people around the globe and in the region.

In this study, HCPs who were involved in vaccination were more knowledgeable about the system and were even involved in calling people who delayed their children’s vaccination for any reason (referred to as defaulters). Some of the interviewed HCPs indicated that they know when to refer such delayers or defaulters to nurses or clinic managers to track them down and encourage them to receive the recommended vaccinations. Others who were not directly involved in the vaccination were not clear about this process, indicating that there was a gap in knowledge in terms of vaccine hesitancy practices in their clinics. This again indicates the gap in the understanding of the roles of HCPs in primary care centers in improving vaccination practices and addressing vaccine hesitancy. Most of the HCPs indicated their full trust in the system regarding childhood vaccination and in the available information for HCPs on vaccination and the support provided by the system to improve vaccination uptake. Kestenbaum & Feemster have indicated the importance of improving HCPs’ knowledge and trust in the public health system to create more successful interventions to address vaccine hesitancy.24

This study has some limitations. First, qualitative research might include the researchers’ biases, and the findings cannot be generalized beyond the study population. Second, most of the HCPs in our study and in the UAE are from different nationalities. Depending on their origin, they may exhibit different perceptions and attitudes toward vaccines. This may ultimately influence their communication with patients on vaccination issues. We also faced difficulties in recruiting HCPs who are directly involved in vaccine administration, education, or advocacy. Owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, we were forced to complete the study and stop recruitment before we reached our target of 35 HCPs. This also prevented us from conducting proofreading of the transcripts, which ensures better reflexivity in qualitative research.

In conclusion, the study suggests that HCPs in the UAE are willing to follow regulations and policies and believe that they are sufficient for mandating and implementing vaccination in the UAE. However, almost all HCPs showed interest in receiving more education and training on skills for addressing vaccine hesitancy among patients and the public. There is a concern that social media affects people’s practices toward vaccination and that should be carefully addressed. HCPs must receive more education on identifying vaccine hesitancy issues and effective communication. Social media should be used more effectively as a platform to address vaccine hesitancy issues and to improve awareness and education. Finally, improving HCP self-efficacy and empowering them to understand and use their role efficiently within their practice and in the community are crucial to address any potential threats of vaccine hesitancy in the country.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the participating healthcare providers at the ambulatory healthcare service clinics for their support of this study.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the United Arab Emirates University under Grant [number 1132]. The funding source did not participate in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Authors’ contributions

IE: participated in the study design, performed the data collection and analysis, and drafted the manuscript. SAH, SA, and RA: participated in the acquisition of data. ED: critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. ARA: conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated data collection and analysis, and drafted the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website.

References

- 1.Ten health issues WHO will tackle this year n.d. [accessed 2020 October28]. https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019

- 2.Opel DJ, Heritage J, Taylor JA, Mangione-Smith R, Salas HS, Devere V, Zhou C, Robinson JD.. The architecture of provider-parent vaccine discussions at health supervision visits. Pediatrics. 2013;132(6):1037–46. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Provider’s Role in Importance of Vaccine Administration and Storage | CDC 2019 . [accessed 2020. October 28]. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/admin/storage/providers-role-vacc-admin-storage.html

- 4.Karafillakis E, Dinca I, Apfel F, Cecconi S, Wűrz A, Takacs J, Suk J, Celentano LP, Kramarz P, Larson HJ, et al. Vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers in Europe: A qualitative study. Vaccine. 2016;34(41):5013–20. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verger P, Fressard L, Collange F, Gautier A, Jestin C, Launay O, Raude J, Pulcini C, Peretti-Watel P. Vaccine hesitancy among general practitioners and its determinants during controversies: a national cross-sectional survey in France. EBioMedicine. 2015;2(8):891–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kun E, Benedek A, Mészner Z. Vaccine hesitancy among primary healthcare professionals in Hungary. Orv Hetil. 2019;160:1904–14. doi: 10.1556/650.2019.31538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.AlMarzooqi LM, AlMajidi AA, AlHammadi AA, AlAli N, Khansaheb HH. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of influenza vaccine immunization among primary healthcare providers in Dubai health authority, 2016-2017. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14:2999–3004. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.1507667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization . WHO vaccine-preventable diseases: monitoring system. 2020 global summary coverage time series for United Arab Emirates (ARE). n.d.. [accessed 2020 October28]. https://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/globalsummary/coverages?c=ARE

- 9.Department of Health - Abu Dhabi. Communicable Diseases Bulletin n.d . [accessed 2019 December21]. https://doh.gov.ae/en/search?q=bulletin

- 10.Alsuwaidi AR, Elbarazi I, Al-Hamad S, Aldhaheri R, Sheek-Hussein M, Narchi H. Vaccine hesitancy and its determinants among Arab parents: a cross-sectional survey in the United Arab Emirates. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1753439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larson H, Karafillakis E, Antoniadou E, Baka A, Baban A, Pereti-Watel P, Verger P, Visěkruna Vučina F, Visěkruna Vučina V, Apfel F, et al. Vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers and their patients in Europe: a qualitative study. [Internet]. Stockholm, Sweden: ECDC; 2015. [cited 2020. Oct 26]. Available from: http://dx.publications.europa.eu/10.2900/425780

- 12.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Statistics Centre - Abu Dhabi . Statistical yearbook of Abu Dhabi 2020. n.d.. [accessed 28October 2020]. https://www.scad.gov.ae/Release%20Documents/Statistical%20Yearbook%20of%20Abu%20Dhabi_2020_Annual_Yearly_en.pdf

- 14.Green LW, Kreuter MW, Deeds SG, Partridge KB, Bartlett E. Health education planning: a diagnostic approach. Palo Alto (California): Mayfield Publishing; 1980. n.d. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zimmerman RK, Silverman M, Janosky JE, Mieczkowski TA, Wilson SA, Bardella IJ, Medsger AR, Terry MA, Ball JA, Nowalk MP. A comprehensive investigation of barriers to adult immunization: a methods paper. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zimmerman RK, Nowalk MP, Bardella IJ, Fine MJ, Janosky JE, Santibanez TA, Wilson SA, Raymund M. Physician and practice factors related to influenza vaccination among the elderly. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kegler MC, Miner K. Environmental health promotion interventions: considerations for preparation and practice. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31:510–25. doi: 10.1177/1090198104265602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siddiqui M, Salmon DA, Omer SB. Epidemiology of vaccine hesitancy in the United States. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9:2643–48. doi: 10.4161/hv.27243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paterson P, Meurice F, Stanberry LR, Glismann S, Rosenthal SL, Larson HJ. Vaccine hesitancy and healthcare providers. Vaccine. 2016;34:6700–06. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacDonald NE, Dubé E. Unpacking vaccine hesitancy among healthcare providers. EBioMedicine. 2015;2:792–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henrikson NB, Opel DJ, Grothaus L, Nelson J, Scrol A, Dunn J, Faubion T, Roberts M, Marcuse EK, Grossman DC, et al. Physician communication training and parental vaccine hesitancy: A randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2015;136:70–79. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McRee A-L, Gilkey MB, Dempsey AF. HPV vaccine hesitancy: findings from a statewide survey of health care providers. J Pediatr Health Care. 2014;28:541–49. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elbarazi I, Devlin NJ, Katsaiti M-S, Papadimitropoulos EA, Shah KK, Blair I. The effect of religion on the perception of health states among adults in the United Arab Emirates: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e016969. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kestenbaum LA, Feemster KA. Identifying and addressing vaccine hesitancy. Pediatr Ann. 2015;44:e71–75. doi: 10.3928/00904481-20150410-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The lancet child adolescent health null. Vaccine hesitancy: a generation at risk. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2019 May;3(5):281. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30092-6. PMID: 30981382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dubé E, Gagnon D, MacDonald N, Bocquier A, Peretti-Watel P, Verger P. Underlying factors impacting vaccine hesitancy in high income countries: a review of qualitative studies. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2018;17:989–1004. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2018.1541406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dubé E, Vivion M, MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy, vaccine refusal and the anti-vaccine movement: influence, impact and implications. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2015;14:99–117. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2015.964212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.