Abstract

Attaining the recommended level of adequacy of the infants' diet remains a serious challenge in developing countries. On the other hand, the incidence of growth faltering and morbidity increases significantly at 6 months of age when complementary foods are being introduced. This trial aimed to evaluate the effect of complementary feeding behaviour change communication delivered through community‐level actors on infant growth and morbidity. We conducted a cluster‐randomized controlled trial in rural communities of Ethiopia. Trial participants in the intervention clusters (eight clusters) received complementary feeding behaviour change communication for 9 months, whereas those in the control clusters (eight clusters) received only the usual care. A pre‐tested, structured interviewer‐administered questionnaire was used for data collection. Generalized estimating equations regression analyses adjusted for baseline covariates and clustering were used to test the effects of the intervention on infant growth and morbidity. Infants in the intervention group had significantly higher weight gain (MD: 0.46 kg; 95% CI: 0.36–0.56) and length gain (MD: 0.96 cm; 95% CI: 0.56–1.36) as compared with those in the control group. The intervention also significantly reduced the rate of infant stunting by 7.5 percentage points (26.5% vs. 34%, RR = 0.68; 95% CI: 0.47–0.98) and underweight by 8.2 percentage points (17% vs. 25.2%; RR = 0.55; 95% CI: 0.35–0.87). Complementary feeding behaviour change communication delivered through community‐level actors significantly improved infant weight and length gains and reduced the rate of stunting and underweight.

Keywords: behaviour change communication, complementary feeding, infant growth, morbidity

Key messages.

Promotion of the optimal complementary feeding practices is a global health priority to improve infant growth and health.

Interventions that provide the appropriate information about complementary feeding are needed to improve caregivers' feeding behaviours, thereby enhancing infant growth and reducing morbidity.

Complementary feeding behaviour change communication delivered through community‐level actors improved infant weight and length gains and reduced the rate of stunting and underweight.

Complementary feeding behaviour change interventions that engaged not only mothers of infants but also their family members could be an effective approach in improving infant growth and health.

1. INTRODUCTION

The first 2 years of life are a critical period for optimal growth and development of children. Most events of malnutrition happen in this period because there is a high demand for adequate diets (Yamauchi, 2008). Malnutrition in the first 2 years of life will result in an irreversible impairment in physical growth and brain development. Hence, enhancing feeding practice during this period is critical to improve health and nutrition in children (World Health Organization [WHO], 2007).

From all established health and nutrition intervention approaches, appropriate infant and young child feeding (IYCF) has the highest degree of impact on child growth and survival (Ruel et al., 2008). Suboptimal child feeding practices account for more than half of the deaths of under five children worldwide. Greater than two‐thirds of the deaths are related to inappropriate child feeding practices during the first 2 years of life. On the opposite hand, studies indicated that optimum complementary feeding practices might stop 6% of deaths in under five children (WHO, 2001).

The complementary feeding period is a critical time of transition in infants' life characterized by a gradual shift from breast milk to family food (Victoria, De Onis, Hallal, Blössner, & Shrimpton, 2010). Infant growth faltering and the incidence of morbidity increases significantly at 6 months of age when complementary foods are being introduced (WHO Guideline, 2020). Improving the adequacy of food in this critical window of period is among the most cost‐effective strategies to improve overall infant health and ensure their nutritional wellbeing (Martorell, 2017). WHO recommends initiation of nutritionally adequate, safe and age‐appropriate complementary foods in addition to breast feeding at the age of 6 months (WHO, 2017a).

Attaining the recommended level of the adequacy of infant's diet remains a major public health concern in developing countries (Pelletier, Frongillo, & Habicht, 1993). The complementary feeding practices are much lower than the WHO recommendation. Complementary foods are initiated untimely, prepared in an unhygienic way and lack the desired quality and quantity that could have adverse health and nutrition consequences on the growth, development and survival of infants (Pelletier, Frongillo, & Habicht, 1993).

Promotion of the optimal complementary feeding practices is a global health priority to improve infants' feeding practices, health and growth (Caulfield, Huffman, & Piwoz, 1999). The Ethiopian government carried out several efforts to enhance complementary feeding practices through the implementation of IYCF guidelines across the country. However, these efforts failed to improve feeding practices at the expected level. The optimal complementary feeding practice was only 5%. As a result, infant malnutrition, morbidity and mortality have remained pervasively high in the country (Federal Ministry of Health Ethiopia, 2004).

Inappropriate complementary feeding practice is not only caused by lack of food but also associated with caregivers' poor knowledge on optimal infant feeding, lack of awareness and harmful cultural beliefs (Ogbo, Ogeleka, & Awosemo, 2018). Interventions that provide the appropriate information are needed to improve caregivers' feeding behaviours, thereby enhancing infant growth and reducing morbidity especially in rural areas (Guldan et al., 2000). However, such interventions could be effective if they are appropriately contextualized, affordable and sustainable (Panjwani & Heidkamp, 2017; Shi & Zhang, 2011). The interventions must also address the key proximal factors that influence infant growth and morbidity. Both the adequacy and safety of complementary diets can influence infant growth and morbidity (Aboud, Moore, & Akhter, 2008).

Community‐based complementary feeding behaviour change interventions have been employed in different parts of the world on an individual or group basis, through health facilities or home visiting programs. Educational interventions, for example, were delivered for caregivers' by health and nutrition officers in Indonesia (Inayati et al., 2012), by primary health care providers in rural China (Zhang, Shi, Chen, Wang, & Wang, 2013), through the health services in Peru (Penny et al., 2005). However, only few randomized‐controlled trials evaluated the effect of such interventions delivered through community‐level actors on infant growth and morbidity. Moreover, the interventions targeted only caregivers of infants and studies that engaged their family members are limited worldwide.

A systematic review of studies conducted in developing countries showed that complementary feeding education significantly improved some growth parameters (height‐for‐age [HAZ] score and weight‐for‐age [WAZ] score) and reduced the rates of stunting. However, no significant impacts were observed for height gain, weight gain and underweight (Lassi, Das, Zahid, Imdad, & Bhutta, 2013).

In Ethiopia, there is no rigorously designed study that evaluated the impact of complementary feeding behaviour change interventions on infant growth and morbidity. Few of the behaviour change interventions conducted by non‐governmental organizations (NGOs) projects (Kim et al., 2015; Negash et al., 2014; U.S. Agency for International Development [USAID], 2011) are non‐randomized, aimed at only improving the IYCF practices. The reports of these projects focus either on implementation fidelity (Kim et al., 2015) or are implementation research (USAID, 2011) and large scale in scope (Kang, Suh, Debele, Juon, & Christian, 2016).

This trial aimed to evaluate the effect of complementary feeding behaviour change communication delivered through community‐level actors on infant growth and morbidity. We hypothesized that the intervention would improve growth of infants and reduce morbidity in the intervention clusters.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study setting

This trial was conducted in rural communities of West Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia, from February 2017 to March 2018. West Gojjam Zone is one of the 13 administrative zones of the Amhara regional state. It has 13 rural districts, and each district is divided into kebeles, the lowest administrative units in Ethiopia. According to the population projection of Ethiopia for all regions at the district level from 2014 to 2017, which is based on the 2007 national census, the zone has a total population of 2,560,131 in 2016; of whom 1,262,144 were male and 1,297,987 were female. The rural part accounts for 92% of the total population. A total of 480,255 households were counted in this Zone, which results in an average of 4.39 persons to a household, and 466,491 housing units. From the total population mentioned, 315,228 were children of under 5 years of age of whom 160,214 were under 2 years of age (Amhara Regional State, 2016).

2.2. The context

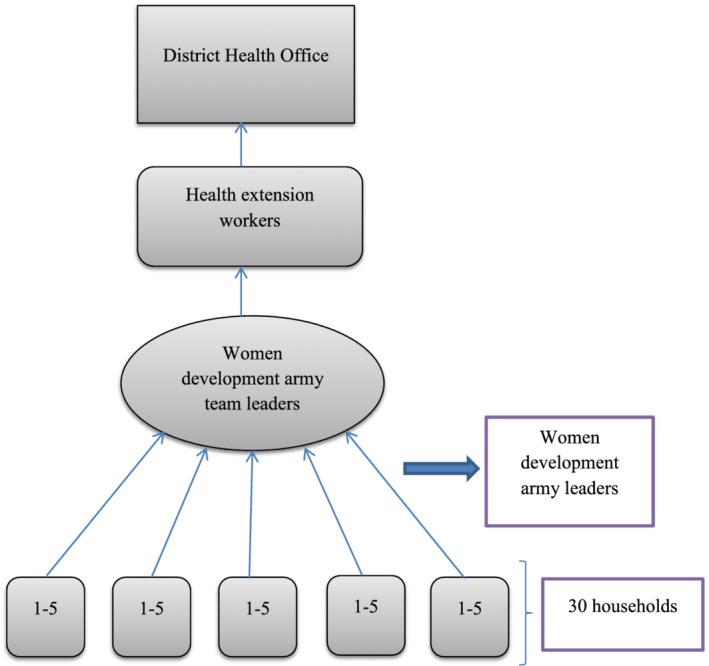

In the Amhara region, a total of 117,428 women development army (WDA) groups and 532,259 one‐to‐five networks were established in 2011 (FDRE, 2015). The one‐to‐five networks are women volunteers who are empowered as WDA to transform their society. They are trained to focus more intensively on sparking local behaviour change making regular rounds to check on neighbours and encourage healthy lifestyles. They are from ‘model families’ and serve as living examples that the health extension workers (HEW) messages are being heard (Maes & Tesfaye, 2015a). The proportion of women of childbearing age is 24% (MOH, 2013).

WDAs are selected from the model families. A household that implemented all of the government's 16 priority health interventions, from vaccinating their children and sleeping under mosquito bed‐nets to building separate latrines and using family planning, is recognized as a model family (Damtew et al., 2018). ‘Model families’ are selected by HEW in collaboration with the kebele administration. They get certificates, are celebrated at kebele ceremonies and asked to support five other households in adopting the priority interventions (Maes & Tesfaye, 2015b). WDAs leaders are unpaid health volunteers that undertake various preventive and promotive health services supported and supervised by HEWs (Linnander et al., 2016).

Once the WDA groups are formed through participatory community involvement, the WDA leaders provided an intensive 7 to 10 days training (MOH, 2014/15), whose primary objective is to educate and mobilize the communities to utilize the maternal, neonatal and child health services delivered by the health post and health centres (Summary & Bissau, 2013). On average, there are approximately 30 WDA team leaders and 200 WDA network leaders in each kebele (MOH, 2013).

Each WDA group is composed of 25–30 households (women), which are further organized into the ‘1 to 5’ network of women where a model woman leads five other women within her neighbourhood (Assefa, Gelaw, Hill, Taye, & Van Damme, 2019). The one‐to‐five network functions as a forum for the exchange of concerns, priorities, problems and decisions related to the health status of women. While being supported by the HEW, the networks are responsible for the preparation of plans and ensuring their completion, for the collection of health information and also for conducting a weekly meeting to review progress and submitting monthly reports (Teklehaimanot & Teklehaimanot, 2013). The WDA groups thus support the implementation of the HEP.

The one‐to‐five networks meet every week, whereas the larger women development team meets once every 2 weeks. Moreover, they review their performance against their plan and evaluate each other monthly and give grades based on their performances. A performance report including the grades is organized at the health development team level and sent to the HEW (MOH, 2014/15).

In our study context, community‐level actors are those people living in the community who have influence change in harmful traditional feeding behaviours and provide a supportive environment for the adoption of the recommended feeding practices. These include WDA leaders and the family members of trial participants (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Hierarchy of women development army and reporting

2.3. Study design and population

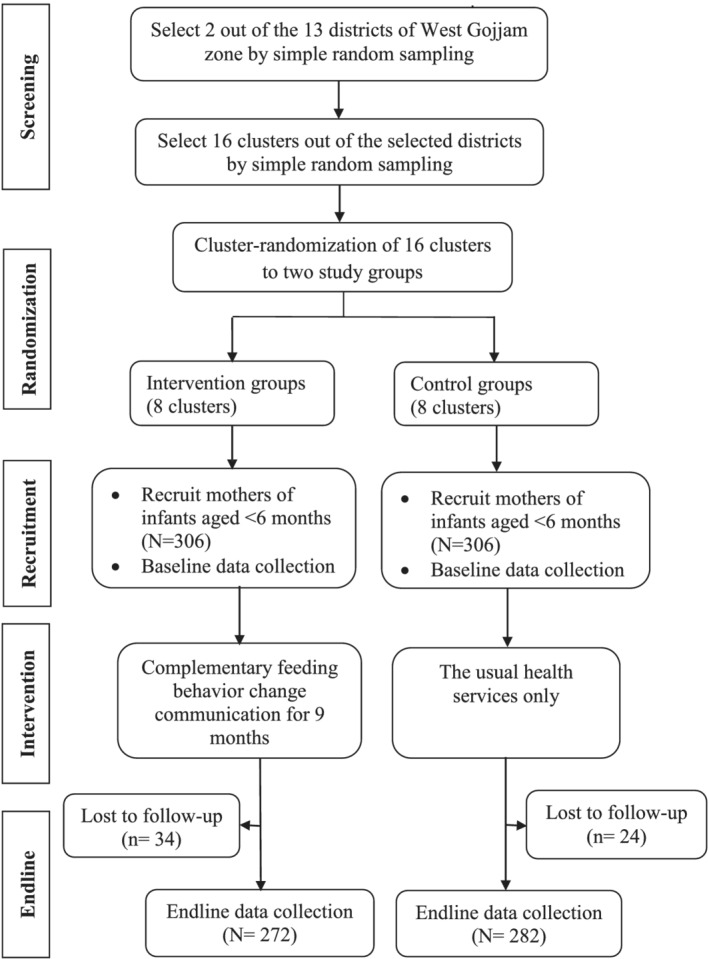

A cluster‐randomized controlled trial single‐blind parallel‐group, two‐arms trial was carried out among mothers of infants aged <6 months of age at the time of enrolment. The trial was reported in line with the CONSORT recommendations for cluster‐randomized trials (Campbell, Piaggio, Elbourne, & Altman, 2012). The intervention was delivered in community settings that encourage collective participation. Hence, the unit of randomization was clusters (kebeles) to minimize intervention contamination and facilitate logistical convenience. Consented mothers who were residents in the study area for at least 6 months before the commencement of the study were recruited and those who were ill and unable to communicate during the study were excluded (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Trial profile

2.4. Sample size determination

This study was part of a larger study entitled ‘effectiveness of complementary feeding behavior change communication delivered through community‐level actors in improving feeding practices, health, and growth of infants in West Gojjam Zone, Northwest Ethiopia’. The sample size was calculated using G‐power based on the following assumptions. Tail (s): One; effect size (d): 0.3; α error probability = 0.05; power (1‐β error probability) = 0.8, and allocation ratio (N1/N2) = 1. This gave a sample size of 278. Then, it was multiplied by the design effect of 2 and allowing for a 10% loss to follow up, the total sample size was 612 (N1 = 306 and N2 = 306). N1 and N2 were sample sizes in the control and intervention group, respectively. The effect size of the intervention on infant linear growth (length gain) was considered; the variable which gave the maximum sample size. Effect size of 0.3 is an anticipated mean difference in linear growth based on a systematic review of complementary feeding education interventions in developing countries that found a mean effect size of 0.21 cm (range 0.01–0.41 cm) for length gain (Lassi, Das, Zahid, Imdad, & Bhutta, 2013).

2.5. Sampling and randomization

A two‐stage cluster sampling technique was applied. First, two out of the 13 districts in West Gojjam Zone were selected by simple random sampling. Second, the lists of all kebeles (clusters) in the selected districts were compiled from the district administrative offices. The number of study subjects in each cluster was obtained from the records of births prepared by HEWs. Each cluster in the selected districts forms the sampling frame, whereas the mother–infant pairs within the cluster formed the final sampling units of observation. Simple randomization with a 1:1 allocation was used to assign clusters to either control or intervention groups. First, 16 nonadjacent clusters (that did not share geographic areas) were selected by simple random sampling. Then, the 16 clusters were listed alphabetically. A list of random numbers was generated in MS Excel 2010, and the generated values were fixed by copying them as ‘values’ next to the alphabetic list of the clusters. These were arranged in ascending order according to the generated random number. Finally, the first eight clusters were selected as intervention clusters and the last eight as control clusters. A statistician that was blinded to study groups and not participated in the trial did the generation of the allocation sequence and the randomization of clusters.

2.6. The intervention

Caregivers' of infants and their family members in the intervention clusters received complementary feeding behaviour change communication for 9 months, whereas those in the control clusters received only the usual health and nutrition care. The language of communication during the intervention period was Amharic (the local language). The intervention had three parts.

Part 1: Training of women development army (WDA) leaders

A total of 24 WDA leaders, who are influential members of their community, were recruited by HEWs in the intervention clusters (three in each cluster) and centrally trained by the researcher. The training sessions focused on the key messages on optimal complementary feeding practices followed by cooking demonstrations on how to prepare and integrate a variety of locally available foods into home‐made complementary foods. The first training session was conducted at the beginning of the intervention whereas the second session with similar content was repeated at the middle (4 months) of the intervention period and each session lasted for 3 days. After training sessions, every participant received a copy of the visual materials (posters) containing the key messages for complementary feeding practices to be used as a reference.

The training contents were adopted from the Alive and Thrive programme in Ethiopia. Key messages were compiled into visual material (posters) used to deliver training (Piwoz, Baker, & Frongillo, 2013). Direct, interactive and participatory learner and activity‐oriented instructional strategies were delivered. Talks, group discussions, group work exercises, demonstrations, role plays, storytelling, simulation, case studies and problem‐solving were used to enhance knowledge, attitude and behaviour change. The intervention key messages were focused on the right time to introduce complementary foods; specific foods to be offered or avoided and how to offer them; meal frequencies; amounts of foods to be fed to infants at different ages while continuing breastfeeding; offering a variety of foods from different food groups; practice responsive feeding; practice good hygiene; and continue to feed the child during and after an illness (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Complementary feeding practices key messages in the intervention clusters

| No. | Key messages |

|---|---|

| 1 | Start feeding your baby soft and thick porridge made from a combination of cereal flours at 6 months. Continue breastfeeding up to 2 years and beyond. |

| 2 | Enrich baby's porridge by adding one or more ingredients from animal‐source foods (milk, egg and dried meat powder), finely chopped vegetables (kale, carrot, cabbage, tomato and potato) and mashed fruits (avocado, papaya, mango, banana and pumpkin) in each meal. |

| 3 | Cook and feed animal‐source foods (e.g. eggs, beef, pork, chicken, liver and fish) at least three times per week. Feed your child fruits (e.g. ripe banana, mango, orange, papaya and avocado) after a meal at least once per day. |

| 4 |

Increase variety, amount and frequency of feeding with age for the baby. Amount of food per meal: Begin with one to three tablespoons at 6 months of age and increase gradually to half a cup (125 ml) between the ages of 6 and 12 months. Between the ages of 12 and 24 months, increase the amount of food to three quarters of a cup (188 ml). Frequency of feeding per day: two to three times at 6–8 months, three to four times at 9–23 months. Feed one to two snacks (e.g. sliced bread and fruits) between two major meals. |

| 5 | Encourage your baby to eat with patience and love. Do not force your baby to eat. Provide extra food during and after an illness. |

| 6 | Feed your baby using a clean cup and spoon; and avoid bottle feeding. Wash your hands with soap and water before preparing food, and before feeding young children. |

| 7 |

Enriched baby's porridge preparation: • Prepare a germinated flour made up of 3/4 staples (one or more ingredients from maize, wheat, rice, millet, sorghum and oat) and 1/4 legumes (one or more ingredients from beans, lentils, chickpeas and groundnuts). • Use milk instead of water for preparing porridge. • Add butter/oil which will make the thick porridge easier to eat. • Add finely chopped meat, fish or eggs. • Add one or more ingredients from finely chopped vegetables and mashed fruits. • Increase the consistency and thickness of the porridge with child age. • Do not forget to use iodized salt. |

Part 2: Group training of mothers by WDA leaders

Each member of the trained WDA leaders was assigned to 10–15 mothers of infants aged younger than 6 months residing in their cluster/village. WDA leaders delivered a total of nine group training sessions including cooking demonstrations (once per month, for 3 days duration each) for the mothers they are assigned with the same training procedures provided by the researcher in Part 1. WDA leaders, as nutrition counsellors, applied a learner‐centred and discussion‐oriented counselling approach. They have delivered the key messages through talks, discussions, storytelling, experience‐sharing, negotiation, simulation, demonstrations and problem‐solving techniques to motivate and reinforce mothers for behaviour change and build confidence on their abilities to practice the recommended feeding practices. WDA leaders applied language and culturally appropriate training sessions with mothers using posters.

Part 3: Home visits

Each WDA leaders conducted a total of nine home visits (once per month, for 2 days duration each) in the intervention clusters that aimed to bring behaviour change at maternal and family level. During each home visit, individual counselling and support were offered for each mother to reinforce the adoption of feeding practices she had been taught during the group training sessions, to observe feeding practices, to demonstrate cooking procedures, to correct the harmful practices and to provide appropriated feedback focusing on the key complementary feeding recommendations. A participatory discussion was held with family members (fathers and grandmothers of the recruited infant) regarding optimal complementary feeding practice, its impact on infant's health, growth and survival; and how can they support the mother in feeding the baby. Each mother provided a poster for the family containing the key messages at the end of each home visit. All the activities of WDA leaders were supervised and monitored by HEWs, and the overall supervision and monitoring were done by the researcher.

All the activities done during the study period are presented in Table 2. Recruitment of study participants and baseline data collection was conducted between February and March 2017. Following the baseline survey, the intervention was delivered for the intervention clusters from April 2017 to December 2017. The endline data collection was carried out between January and February 2018.

TABLE 2.

Schedule of activities during the study period

| Activities | Time points in months | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

| Enrolment and baseline data collection | xI + C | xI + C | |||||||||||

| Training of WDA leaders | x I | x I | |||||||||||

| Group training of mothers | x I | x I | x I | x I | x I | x I | x I | x I | x I | ||||

| Home visits | x I | x I | x I | x I | x I | x I | x I | x I | x I | ||||

| Process evaluation | x I | x I | x I | x I | x I | x I | x I | x I | x I | ||||

| Endline data collection | xI + C | xI + C | |||||||||||

| Supervision | xI + C | xI + C | x I | x I | x I | x I | x I | x I | x I | x I | x I | xI + C | xI + C |

Note: Superscript ‘I’ means intervention groups; superscript ‘C’ means control groups; superscript ‘I + C’ means activities both in intervention and control groups.

2.7. Blinding

Data collectors were not informed of the allocation clusters and were not residents in any of the clusters. However, trial participants knew the intervention allocation due to the nature of the intervention, even if its specific purpose was not disclosed.

2.8. Process evaluation

Process evaluation was conducted to document the intervention implementation process and assess whether the intervention activities were implemented as planned, evaluate the performance of WDA leaders and the extent to which the intervention reached the intended mothers and family members (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Process evaluation

| Data sources | Process indicators | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Assess whether the intervention activities are implemented as planned | ||

| Activity logs |

• Number of training sessions including cooking demonstrations held with WDA leaders • Number of visual materials distributed to WDA leaders • Number of training sessions including cooking demonstration held with mothers • Number of visual materials distributed to mothers |

Fidelity |

| 2. Evaluate the performance of WDA leaders | ||

| Attendance records |

• Number of recruited WDA leaders • Number of WDA leaders trained • Number of home visits conducted by WDA leaders |

Dose delivered (exposure) |

| 3. Evaluate the extent to which the intervention reached the intended mothers and family members | ||

| Attendance records |

• Number of recruited mother‐infant pairs • Number of mothers trained • Number of mothers attended home visits • Number of family members attended home visits |

Dose delivered (exposure) |

2.9. Data collection methods

Data collections were conducted using a pre‐tested structured interviewer‐administered questionnaire adopted from WHO (2017b) and Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) (Central Statistical Agency [Ethiopia] and ICF International, 2012). The questionnaire was prepared in English and translated to the local language Amharic and then back to English by experts of the language to keep its consistency. Trainings on data collection tools and anthropometry were given to data collectors and supervisors by the researcher. A pre‐test was done on 5% of the sample to assess the applicability of the instrument and was ratified accordingly.

Data on infant, maternal and household characteristics that may confound intervention outcomes were collected at baseline in both study groups at the same time. Recruited infants were aged 1–6 months at baseline and as the intervention period was for 9 months; infants achieved 10–15 months at the time of endline data collection in both study groups. Data on infant's anthropometry and morbidity were collected both at baseline and endline (the end of the intervention period) in both study groups at the same time. Infants were weighed with light clothing to the nearest 10 g using Salter scale. Infant's recumbent length was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a portable wooden infant length board with a fixed head and sliding foot piece. All anthropometric measurements were performed in duplicate.

Standardization exercises for interobserver and intraobserver variability in weight and length measurements were performed in which each infant was measured twice (10 sets of 10 infants). The data collections were commenced when all field workers obtained identical readings in both their measurements and were in perfect agreement with the supervisor. All measurement instruments were calibrated before each measurement session (Ulijaszek & Kerr, 1999). To enhance blinding, objectives of the study and cluster allocation to the trial were masked to data collectors, and the data collection schedule was randomized. WDA leaders were not involved in data collection. Daily supervision was conducted by the supervisors and researcher.

2.10. Data processing and analyses

Data were double entered into the EPI‐Info, exported to SPSS version 22 for cleaning and statistical analysis. The outcomes of the trial were infant's growth measured by weight gain, length gain, stunting, underweight and wasting, and infant morbidity.

Weight gain was calculated by subtracting the weight of each infant at baseline from the endline and taken as an outcome variable for weight. Difference in mean weight gain (difference‐in‐difference) between in the study groups was used as a measure of intervention effect. Similar technique was applied for the length gain.

Stunting, underweight and wasting were calculated after generating z‐scores for HAZ, weight‐for‐height (WHZ) and WAZ by using WHO 2006 child growth standards in the ANTHRO software, respectively. Infants with a HAZ below −2 of the reference population were considered stunted, those with a WAZ below −2 were considered underweight, and those with WHZ below −2 were considered wasted (WHO Child Growth Standards, 2006).

Infant morbidity was examined through maternal recall of the prevalent illness symptoms (diarrhoea, fever and cough), in the past 2 weeks from the date of the interview. The presence of each illness symptom was coded as ‘1’ and its absences as ‘0’. Diarrhoea (3 or more loss of liquid stools during a 24‐h period), fever (an abnormally high body temperature) and cough (as rapid expulsion of air from the lungs) were determined by the mother's report (WHO, 2017c).

Baseline infant, caregiver and household characteristics were assessed for comparability between the study groups using chi‐square for categorical variables and t test for continuous variables. Linear generalized estimating equations (GEE) regression analyses were used to test the effects of the intervention on weight and height gains. Binary GEE regression analyses were used to test effects of the intervention on stunting, underweight, wasting and morbidity. All the GEE analyses were adjusted for baseline covariates and clustering. MD (mean differences) and relative risks (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) were computed as a measure of intervention effects for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. The adjusted effect measures were considered as the main results. All analyses were conducted according to the intention to treat (ITT) principle. All the analyses were conducted using SPSS version 22, and p‐values <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

2.11. Ethical considerations

All procedures involving the research were approved by Jimma University College of Health sciences institutional and review board. Permission to undertake the study was obtained from the regional, zonal and district administration and health offices of the study area. After the identification of eligible mothers, the nature and purpose of the study were explained along with their right to refuse. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The right of the participant to withdraw from the study at any time was respected. The data were not accessed by a third person, except the researchers, and were kept confidential.

3. RESULTS

At baseline, a total of 612 mother–child pairs (306 in the control and 306 in the intervention group) were recruited yielding a response rate of 100%. Of these, 34 (11%) in the intervention group and 24 (7.8%) in the control group were excluded in the study because they moved away from the study area, decided not to continue in the study or were lost to follow‐up during the endline data collection. Overall, endline data were completed for 554 (90.5%) of the study participants in both study groups.

3.1. Baseline characteristics

Baseline infant, maternal and household characteristics were comparable between the intervention and control clusters (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Baseline characteristics of the study participants

| Variable | Control group (N = 282) | Intervention group (N = 272) |

|---|---|---|

| Infant | ||

| Sex (%) | ||

| Male | 55.3 | 54.6 |

| Female | 44.7 | 45.6 |

| Age (months), mean + SD | 3.22 + 1.4 | 3.21 + 1.48 |

| Anthropometry | ||

| Weight (kg), mean ± SD | 5.50 ± 1.06 | 5.47 ± 1.05 |

| Length (cm), mean ± SD | 59.56 ± 3.77 | 59.22 ± 4.04 |

| Malnutrition | ||

| Wasting (%) | 27 (9.6) | 24 (8.8) |

| Stunting (%) | 64 (24) | 69 (25.4) |

| Underweight (%) | 54 (19) | 50 (18.4) |

| Morbidity | ||

| Fever | 45 (14.7) | 54 (17.6) |

| Diarrhoea | 44 (14.4) | 39 (12.7) |

| Cough | 34 (12) | 30 (11) |

| Maternal | ||

| Age (months), mean ± SD | 27.2 ± 5 | 28.05 ± 4.8 |

| Educational status (%) | ||

| Attended formal education | 23.8 | 19.4 |

| No formal education | 76.2 | 80.6 |

| Occupation (%) | ||

| Farmer | 12.1 | 10.8 |

| Housewife | 87.9 | 89.2 |

| Marital status (%) | ||

| Married | 93.6 | 94.6 |

| Others | 6.4 | 5.4 |

| Parity (%) | ||

| Primiparous | 16.7 | 19.8 |

| Multiparous | 83.3 | 80.2 |

| ANC visit (%) | ||

| Yes | 73.4 | 71.4 |

| No | 26.6 | 28.6 |

| Place of delivery (%) | ||

| Home | 63.5 | 64.8 |

| Health facility | 36.5 | 35.2 |

| PNC (%) | ||

| Yes | 27 | 22.7 |

| No | 73 | 77.3 |

| IYCF counselling (%) | ||

| Yes | 33 | 30.4 |

| No | 67 | 69.6 |

| Household | ||

| Family size, mean ± SD | 5.5 ± 1.8 | 5.3 ± 1.9 |

| Possession of radio (%) | ||

| Yes | 19.5 | 22 |

| No | 80.5 | 78 |

3.2. Effects of the intervention

3.2.1. Effects on infant weight and length gains

Table 5 presents the effects of the intervention on infant weight and length gains. Infants in the intervention group had a higher weight gain (2.50 ± 0.68 kg) as compared with those in the control group (2.04 ± 0.61 kg) and the difference was statistically significant (DiD = 0.46 kg; 95% CI: 0.36–0.56). There was also a statistically significant difference in length gain between the study groups; 9.20 ± 2.80 cm in the intervention groups, and 8.22 ± 2.59 cm in the control groups (DiD: 0.96 cm; 95% CI: 0.56–1.36).

TABLE 5.

Effects of the intervention on infant weight and length gains

| Variable | Groups | Baseline | Endline | Gain | Adjusted effect (DiD) (95% CI) a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | CG | 5.50 ± 1.06 | 7.54 ± 0.84 | 2.04 ± 0.61 | 0 |

| IG | 5.47 ± 1.05 | 7.97 ± 0.83 | 2.50 ± 0.68 | 0.46 (036–0.56)* | |

| Length (cm) | CG | 59.47 ± 3.74 | 67.69 ± 2.49 | 8.22 ± 2.59 | 0 |

| IG | 59.22 ± 4.04 | 68.42 ± 2.51 | 9.20 ± 2.80 | 0.96 (0.56–1.36)* |

Note: Data present means + SD unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: CG, control group; CI, confidence interval; DiD, difference‐in‐differences; IG, intervention group.

Adjusted for baseline infant (age, sex, stunting, underweight, wasting, fever, diarrhoea and cough), maternal (age, educational status, marital status, parity, ANC, place of delivery, PNC and IYCF counselling), household characteristics (family size and possession of radio), and clustering.

p‐value: <0.001.

3.2.2. Effects on infant stunting, underweight and wasting

Table 6 presents the effects of the intervention on the rates of stunting, underweight and wasting at endline. The rates of stunting (26.5% vs. 34%; RR = 0.68; 95% CI: 0.47–0.98) and underweight (17% vs. 25.2%; RR = 0.55; 95% CI: 0.35–0.87) were significantly lower in the intervention as compared with control groups, respectively. However, there was no statistically significant difference in the rate of wasting between the intervention, 8.8%, and control groups, 9.9% (RR = 0.91; 95% CI: 0.49–1.67).

TABLE 6.

Effects of the intervention on infant stunting, underweight and wasting

| Study groups | N (%) | RR (95% CI) a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stunting | CG | 96 (34) | 1 |

| IG | 72 (26.5) | 0.68 (0.465–0.988) 0.043* | |

| Underweight | CG | 71 (25.2) | 1 |

| IG | 46 (17) | 0.55 (0.345–0.873) 0.011* | |

| Wasting | CG | 28 (9.9) | 1 |

| IG | 24 (8.8) | 0.91 (0.493–1.667) 0.752 |

Abbreviations: CG, control group; CI, confidence interval; IG, intervention group; RR, relative risk.

Adjusted for baseline infant (age, sex, stunting, underweight, wasting, fever, diarrhoea and cough), maternal (age, educational status, marital status, parity, ANC visit, place of delivery, PNC and IYCF counselling), household characteristics (family size and possession of radio), and clustering.

p‐value: <0.05.

3.2.3. Effect on infant morbidity

Table 7 presents the effect of the intervention on infant morbidity at endline. No statistically significant differences were found in the prevalence of fever (16.9% vs. 17.7%; RR = 0.90; 95% CI: 0.57–1.43), diarrhoea (23% vs. 19.5%; RR = 0.82; 95% CI: 0.54–1.25) and cough (8.5% vs. 10%; RR = 0.82; 95% CI: 0.45–1.51) between the intervention and control groups, respectively.

TABLE 7.

Effect of the intervention on infant morbidity

| Morbidity | Groups | N (%) | RR (95% CI) a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fever | CG | 50 (17.7) | 1 |

| IG | 46 (16.9) | 0.90 (0.57–1.43) | |

| Diarrhoea | CG | 65 (23) | 1 |

| IG | 53 (19.5) | 0.82 (0.54–1.25) | |

| Cough | CG | 28 (10) | 1 |

| IG | 23 (8.5) | 0.82 (0.45–1.51) |

Abbreviations: CG, control group; CI, confidence interval; IG, intervention group; RR, relative risk.

Adjusted for baseline infant (age, sex, stunting, underweight, wasting, fever, diarrhoea and cough), maternal (age, educational status, marital status, parity, ANC visit, place of delivery, PNC and IYCF counselling), household characteristics (family size and possession of radio), and clustering.

4. DISCUSSION

We implemented a community‐based cluster‐randomized controlled trial to investigate the effectiveness of complementary feeding behaviour change communication delivered through community‐level actors on infant growth and morbidity. In this trial, infants in the intervention group had significantly higher weight gain (MD: 0.46 kg; 95% CI: 036–0.56) and length gain (MD: 0.96 cm; 95% CI: 0.56–1.36) as compared with those in the control group. The intervention also significantly reduced the rate of stunting by 7.5 percentage points (RR = 0.68; 95% CI: 0.47–0.98) and underweight by 8.2 percentage points (RR = 0.55; 95% CI: 0.35–0.87). However, the intervention did not significantly affect the rate of wasting and morbidity.

The incidence of growth faltering and morbidity increases significantly at 6 months of age when complementary foods are being introduced. In order to sustain the gains made by promoting exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life, interventions need to extend into the second half of infancy and beyond (WHO, 2020). Improving the quantity and quality of food in this critical window of period is among the most cost‐effective strategies to improve overall infant health and ensure nutritional wellbeing (Martorell, 2017). This could be ensured by enabling caregivers to appropriately feed their children with safe and adequate complementary foods while maintaining frequent breastfeeding (WHO, 2017c).

The results of this trial are consistent with the findings of complementary feeding behaviour change interventions conducted in different parts of the world. A cluster‐randomized controlled trial was conducted in Pakistan to evaluate the impact of maternal educational messages regarding appropriate complementary feeding on the growth and nutritional status of their infants after 30 weeks of educational interventions delivered by trained community health workers. At the end of the study, infants in the intervention group had significantly higher weight gain (MD: 0.35 kg) and length gain (MD: 0.66 cm) as compared with the controls. The intervention was also significantly reduced the rate of stunting by 10 percentage points, but no significant differences were found on the rate of underweight and wasting between the study groups (Saleem, Mahmud, Baig‐ansari, & Zaidi, ).

A similar result was found by a behaviour change intervention conducted in the Philippines. In this study, caregivers of young children and their family members in the intervention group received counselling sessions on the appropriate complementary feeding though home visits for 8 months, whereas those in the control group received the usual care. Children in the intervention group had significantly higher weight gain (MD: 0.25 kg) and length gain (MD: 1.2 cm) as compared with those in the control group (Dumaguing, Hurtada, & Yee, 2015).

In another cluster‐randomized controlled trial conducted in rural China, infants were enrolled at age 2–4 months and followed up until 1 year of age. In the intervention group, complementary feeding educational messages and enhanced home‐prepared recipes were disseminated to caregivers through group trainings and home visits. Infants in the intervention group gained 0.22 kg more weight and gained 0.66 cm more length than did controls over the study period, and the differences were statistically significant (Shi, Zhang, Wang, Caulfield, & Guyer, 2009). A cluster‐randomized controlled trial of an educational intervention delivered though health services in Peru also found a significantly higher length gain (MD = 0.71 cm), and 11 percentage points reduction in the rate of stunting for infants in the intervention as compared with those in the control group. However, no significant difference was found on weight gain (MD = 0.12 kg) between the study groups (Penny et al., 2005).

A community based behaviour change intervention on optimal complementary feeding was conducted in rural India. This cluster‐randomized trial tested the hypothesis that teaching caregivers appropriate complementary feeding and strategies for how to feed and play responsively through home‐visits would increase children's growth and morbidity compared with home‐visit‐complementary feeding education alone or routine care. The intervention resulted in improved dietary intake, but there were no statistically significant in mean differences for weight and length, the rate of stunting and morbidity among the groups. The possible reason is the number of messages given to include complementary feeding, responsive feeding and play together at the home visits, combined with constraints on available time at their disposal, could have limited the mothers'/caregivers' ability to implement all the messages recommended (Vazir et al., 2012).

In the present study, the effects of the intervention on infant weight and length gains were relatively higher than those found in the studies discussed above. This could be due to different reasons. First, in this study, the intervention was delivered through community‐level actors who would have influence change in harmful feeding behaviours and encourage the adoption of the recommended complementary feeding practices that could lead to better physical growth of infants. Second, the intervention targeted not only mothers of infants but also engaged their family members that would provide a supportive environment for behaviour change. Third, the mothers were trained how to incorporate locally available and affordable nutritious foods into the existing home‐made complementary foods during cooking demonstrations that can be well accepted by mothers.

The strengths of this study are the use of the randomized controlled design and inclusion of a fairly large sample size, and the intervention effect could be sustainable because it was delivered in a community supportive environment. Our study has limitations to be mentioned. First, due to the nature of the study, it was not possible to conduct a double‐blind trial. Trial participants knew of the existence training on complementary feeding in their village, even if they did not know its specific purpose. Second, data on infant morbidity were collected based on maternal report of the prevalence illness, which was not a validated method, and a recall bias cannot also be excluded. Third, our study had only two data collection sessions (at baseline and endline). Hence, we recommend that similar studies in the future be accompanied with longer intervention period, more follow‐up visits and measurements to investigate long‐term impacts of the intervention. Lastly, the study was not supported with a qualitative data to explore the perceptions and experience of the study participants about the intervention delivered.

In conclusion, this study showed the potential effectiveness of complementary feeding behaviour change intervention conducted in a community supportive environment in improving infant growth and reducing the rate of stunting and underweight. Significant changes in infant growth can be achieved through the promotion of a variety of locally available and affordable complementary foods that can be well accepted by the community. The result also suggests that a well‐designed behaviour change intervention without food supplements can improve infant growth and reduce the rate of undernutrition. The findings of our study have significant implications for designing community‐based interventions for improving infant growth and prevention of undernutrition with similar settings in other countries.

Sustainable and replicable interventions to reduce malnutrition and improve infant growth are urgently needed in developing countries. In our study, the intervention is delivered through community‐level actors and in a community supportive environment. This sheds light on the intervention's potential to be sustained because even in a context of changeable government policies, community‐level actors continue to influence change in the harmful traditional feeding practices, promote the recommended feeding behaviours and thereby improve infant growth. In addition, this intervention strategy can and will be integrated into the existing community health system, as a means of ensuring its sustainability. To test the replicability of the results observed, we recommend the strategies employed in this study to be adapted by future nutrition intervention studies with similar setting.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

CONTRIBUTIONS

CAA conceived, designed the study, performed the analysis and interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. TB participated in the analysis and drafting of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the study participants for providing valuable information. We are also grateful to express our gratitude to data collectors and supervisors for their commitment. This work was supported by Jimma University.

Ayalew CA, Belachew T. Effect of complementary feeding behaviour change communication delivered through community‐level actors on infant growth and morbidity in rural communities of West Gojjam Zone, Northwest Ethiopia: A cluster‐randomized controlled trial. Matern Child Nutr. 2021;17:e13136. 10.1111/mcn.13136

Trial registration: The trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov as NCT03488680.

Funding information Jimma University

REFERENCES

- Aboud, F. E. , Moore, A. C. , & Akhter, S. (2008). Effectiveness of a community‐based responsive feeding programme in rural Bangladesh: A cluster randomized field trial. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 4, 275–286. 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2008.00146.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amhara Regional State . (2016). Budget brief Amhara regional state 2007/08–2015/16. UNICEF.

- Assefa, Y. , Gelaw, Y. A. , Hill, P. S. , Taye, B. W. , & Van Damme, W. (2019). Community health extension program of Ethiopia, 2003–2018: Successes and challenges toward universal coverage for primary healthcare services. Globalization and Health, 15, 24. 10.1186/s12992-019-0470-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, M. K. , Piaggio, G. , Elbourne, D. R. , & Altman, D. G. (2012). Consort 2010 statement: Extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ, 345(7881), 1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield, L. E. , Huffman, S. L. , & Piwoz, E. G. (1999). Interventions to improve intake of complementary foods by infants 6 to 12 months of age in developing countries: Impact on growth and on the prevalence of malnutrition and potential contribution to child survival. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 20(2), 183–200. 10.1177/156482659902000203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Central Statistical Agency [Ethiopia] and ICF International . (2012). Ethiopia demographic and health survey 2011. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland, USA: Central Statistical Agency and ICF International. [Google Scholar]

- Damtew, Z. A. , Karim, A. M. , Chekagn, C. T. , Fesseha Zemichael, N. , Yihun, B. , Willey, B. A. , & Betemariam, W. (2018). Correlates of the Women's Development Army strategy implementation strength with household reproductive, maternal, newborn and child healthcare practices: A cross‐sectional study in four regions of Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 18(Suppl 1), 373. 10.1186/s12884-018-1975-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumaguing, N. V. , Hurtada, W. A. , & Yee, M. G. (2015). Complementary feeding counselling promotes physical growth of infant and young children in rural villages in Leyte, Philippines. Journal of Society and Technology, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia . (2015). Policy and practice. Quarterly Health Bulletin., 5(1), 49–50. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Ministry of Health . (2004). Family Health and Nutrition Department. National Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding Ethiopia. https://motherchildnutrition.org/nutrition-protection-promotion/pdf/mcn-national‐startegy‐for‐inafnt‐and‐young‐child‐feedign‐ethiopia.pdf. Accessed on: 10 Apr 2020.

- Guldan, G. S. , Fan, H.‐C. , Ma, X. , Ni, Z. Z. , Xiang, X. , & Tang, M. Z. (2000). Culturally appropriate nutrition education improves infant feeding and growth in rural Sichuan, China. The Journal of Nutrition, 130(5), 1204–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inayati, D. A. , Scherbaum, V. , Purwestri, R. C. , Wirawan, N. N. , Suryantan, J. , Hartono, S. , … Bellows, A. C. (2012). Improved nutrition knowledge and practice through intensive nutrition education: A study among caregivers of mildly wasted children on Nias Island, Indonesia. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 33(2), 117–127. 10.1177/156482651203300205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Y. , Suh, Y. K. , Debele, L. , Juon, H. S. , & Christian, P. (2016). Effects of a community‐based nutrition promotion programme on child feeding and hygiene practices among caregivers in rural Eastern Ethiopia. Public Health Nutrition, 20(8), 1461–1472. 10.1017/S1368980016003347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. S. , Ali, D. , Kennedy, A. , Tesfaye, R. , Tadesse, A. W. , Abrha, T. H. , … Menon, P. (2015). Assessing implementation fidelity of a community‐ based infant and young child feeding intervention in Ethiopia identifies delivery challenges that limit reach to communities: A mixed‐method process evaluation study. BMC Public Health, 15, 316. 10.1186/s12889-015-1650-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassi, Z. S. , Das, J. K. , Zahid, G. , Imdad, A. , & Bhutta, Z. A. (2013). Impact of education and provision of complementary feeding on growth and morbidity in children less than 2 years of age in developing countries: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 3, S13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnander, E. , Fekadu, B. , Alemu, H. , Omer, H. , Canavan, M. , Smith, J. , … Bradley, E. (2016). The Ethiopian health extension program and variation in health systems performance: What matters? PLoS ONE, 11(5), e0156438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes, K. C. , & Tesfaye, Y. A. (2015a). A women's development army: Narratives of community health worker investment and empowerment in rural Ethiopia. Studies in Comparative International Development, 50(4), 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- Maes, K. C. , & Tesfaye, Y. A. (2015b). Using community health workers: Discipline and hierarchy in Ethiopia's women's development army. Annals of Anthropological Practice., 39, 42–57. 10.1111/napa.12060 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martorell, R. (2017). Improved nutrition in the first 1000 days and adult human capital and health. American Journal of Human Biology, 29(2), e22952. 10.1002/ajhb.22952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health . (2013). The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. Health Sector Development Programme IV. https://www.ccghr.ca/wp‐content/uploads/2013/11/healthsectordevelopmentprogram.pdf. Accessed 08 Jan 2020.

- Negash, C. , Belachew, T. , Henry, C. J. , Kebebu, A. , Abegaz, K. , & Whiting, S. J. (2014). Nutrition education and introduction of broad bean‐based complementary food improves knowledge and dietary practices of caregivers and nutritional status of their young children in Hula, Ethiopia. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 35(4), 480–486. 10.1177/156482651403500409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogbo, F. A. , Ogeleka, P. , & Awosemo, A. O. (2018). Trends and determinants of complementary feeding practices in Tanzania. Tropical Medicine and Health, 46, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panjwani, A. , & Heidkamp, R. (2017). Complementary feeding interventions have a small but significant impact on linear and ponderal growth of children in low‐ and middle‐income countries: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. The Journal of Nutrition, 147(Suppl), 2169S–2178S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier, D. L. , Frongillo, E. A. , & Habicht, J. P. (1993). Epidemiologic evidence for a potentiating effect of malnutrition on child mortality. American Journal of Public Health, 83(8), 1130–1133. 10.2105/AJPH.83.8.1130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penny, M. E. , Creed‐Kanashiro, H. M. , Robert, R. C. , Narro, M. R. , Caulfield, L. E. , & Black, R. E. (2005). Effectiveness of an educational intervention delivered through the health services to improve nutrition in young children: A cluster‐randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 365(9474), 1863–1872. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66426-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piwoz, E. , Baker, J. , & Frongillo, E. A. (2013). Documenting large‐scale programs to improve infant and young child feeding is key to facilitating progress in child nutrition. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 34(3), S143–S145. 10.1177/15648265130343S201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruel, M. T. , Menon, P. , Habicht, J.‐P , Loechl, C. , Bergeron, G. , Pelto, G. , … Hankebo, B. (2008). Age‐based preventive targeting of food assistance and behaviour change and communication for reduction of childhood undernutrition in Haiti: A cluster randomised trial. Lancet, 371(9612), 588–595. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60271-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleem, A. F. , Mahmud, S. , Baig‐Ansari, N. , & Zaidi, A. K. (2014). Impact of maternal education about complementary feeding on their infants' nutritional outcomes in low‐ and middle‐income households: A community‐based randomized interventional study in Karachi, Pakistan. Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition, 32(4), 623–633. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L. , & Zhang, J. (2011). Recent evidence of the effectiveness of educational interventions for improving complementary feeding practices in developing countries. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics, 57(2), 91–98. 10.1093/tropej/fmq053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L. , Zhang, J. , Wang, Y. , Caulfield, L. E. , & Guyer, B. (2009). Effectiveness of an educational intervention on complementary feeding practices and growth in rural China: A cluster randomised controlled trial. Public Health Nutrition, 13(4), 556–565. 10.1017/S1368980009991364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summary, E. , & Bissau, G. (2013). Ethiopia UNICEF annual report 2013‐Ethiopia. 1–62. https://www.unicef.orp/about/report/files/Ethiopia_COAR_2013.pdf. Accessed on: 14 May 2020.

- Teklehaimanot, H. D. , & Teklehaimanot, A. (2013). Human resource development for a community‐based health extension program: A case study from Ethiopia. Human Resources for Health, 11(1), 39. 10.1186/1478-4491-11-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulijaszek, S. J. , & Kerr, D. A. (1999). Review article Anthropometric measurement error and the assessment of nutritional status. British Journal of Nutrition, 44, 165–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Agency for International Development . (2011). Ethiopia‐TIPS‐report. Available from: http://www.manoffgroup.com/6IYCN‐Ethiopia‐TIPS‐report‐120111.pdf

- Vazir, S. , Engle, P. , Balakrishna, N. , Griffiths, P. L. , Johnson, S. L. , Creed‐Kanashiro, H. , … Bentley, M. E. (2012). Cluster‐randomized trial on complementary and responsive feeding education to caregivers found improved dietary intake, growth and development among rural Indian toddlers. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 9(1), 99–117. 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2012.00413.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victora, C. G. , De Onis, M. , Hallal, P. C. , Blössner, M. , & Shrimpton, R. (2010). Worldwide timing of growth faltering: Revisiting implications for interventions. Pediatrics, 125(3), e473–e480. 10.1542/peds.2009-1519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2001). Global strategy for infant and young child feeding. Fifty‐fourth world Heal Assem. (1):5. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42590/1/9241562218.pdf. Accessed on 20 Mar 2020.

- World Health Organization . (2007). Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices. World Heal Organ. 1–19. http://scholar.google.com/scholar/Indicators‐for‐assessing‐infant‐and‐young‐child‐feeding‐practices. Accessed 17 Jan 2020.

- World Health Organization . (2017a). Guidance on ending the inappropriate promotion of foods for infants and young children: implementation manual. Geneva. https://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/manual‐ending‐inapptoptiate‐promotion‐food. Accssed on: 15 May 2020.

- World Health Organization . (2017b). Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices. World Heal Organ. 1–19. http://scholar.google.com/scholar=intitle: Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices.

- World Health Organization . (2017c). Integrated management of childhood illness global survey report. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by‐nc‐sa/3.0/igo. Accessed on: 24 Feb 2020.

- World Health Organization Child Growth Standards . (2006). Length/height‐for‐age, weight‐for‐age, weight‐for‐length, weight‐forheight and body mass index‐for‐age: methods and development. https://www.who.int/childgrowth/en. Accessed on: 12 Apr 2020.

- World Health Organization Guideline . (2020). Improving childhood development‐summary. https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/child/summary_guideline_improving_early_childhood_development.pdf. Accessed 02 Jan 2020.

- Yamauchi, F. (2008). Early childhood nutrition. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 56(3), 657–682. 10.1086/533542 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. , Shi, L. , Chen, D. F. , Wang, J. , & Wang, Y. (2013). Effectiveness of an educational intervention to improve child feeding practices and growth in rural China: Updated results at 18 months of age. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 9(1), 118–129. 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2012.00447.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]