Abstract

Green tea is commonly consumed in China, Japan, and Korea and certain parts of North Africa and is gaining popularity in other parts of the world. The aim of this review was to objectively evaluate the existing evidence related to green tea consumption and various health outcomes, especially cancer, cardiovascular disease and diabetes. This review captured evidence from meta-analyses as well as expert reports and recent individual studies. For certain individual cancer sites: endometrial, lung, oral and ovarian cancer, and non-Hodgkins lymphoma the majority of meta-analyses observed an inverse association with green tea. Mixed findings were observed for breast, esophageal, gastric, liver and a mostly null association for colorectal, pancreatic, and prostate cancer. No studies reported adverse effects from green tea related to cancer although consuming hot tea has been found to possibly increase the risk of esophageal cancer and concerns of hepatotoxity were raised as a result of high doses of green tea. The literature overall supports an inverse association between green tea and cardiovascular disease-related health outcomes. The evidence for diabetes-related health outcomes is less convincing, while the included meta-analyses generally suggested an inverse association between green tea and BMI-related and blood pressure outcomes. Fewer studies investigated the association between green tea and other health outcomes such as cognitive outcomes, dental health, injuries and respiratory disease. This review concludes that green tea consumption overall may be considered beneficial for human health.

Subject terms: Cardiovascular diseases, Cancer, Risk factors

Introduction

Green tea is commonly consumed in East Asian countries such as China and Japan, as well as some parts of North Africa and the Middle East [1]. Green tea’s popularity is increasing globally. Green tea is made from leaves that are steamed (Japan) or roasted (China) shortly after harvesting to inactivate enzymes, preventing oxidative fermentation, then pressed and finally dried [2, 3]. A 2014 review includes a useful overview of catechin’s composition of brewed green tea based on the USDA Database for the Flavonoid Content [4]. Various potential health benefits of green tea have been reviewed [5] including anti-inflammatory [6], antibacterial [7], neuroprotective [8], and cholesterol-lowering effects [9], which may have an impact on cancer and cardiometabolic risk.

The World Cancer Research Fund Third Expert Report and Continuous Update Project (CUP) [2, 10] includes a discussion on green tea consumption and site-specific cancers, however, evidence was too limited to draw a conclusion [2]. The International Agency for Research on Cancer Monographs Volume 51 published in 1991 also includes an evaluation of green tea carcinogenic risks to humans [3]. Numerous meta-analyses and individual studies exist on the association between green tea and various health outcomes particularly individual cancers [11–14].

Evidence on the health effects of green tea and various health outcomes is accruing, 2020 is an opportune time to review the evidence. Compared to coffee [15] and black tea [16] fewer meta-analyses are available on individual health outcomes and therefore a strict umbrella review, exclusively including meta-analyses, was not deemed the most appropriate design to capture the breadth of evidence for this study. Previous green tea reviews emphasized general health benefits in vitro or specific outcomes. In this review, we aim to deliver an objective overview of the current evidence from meta-analyses, individual studies and reports on green tea and health outcomes with a focus on individual cancer sites, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes.

Methods

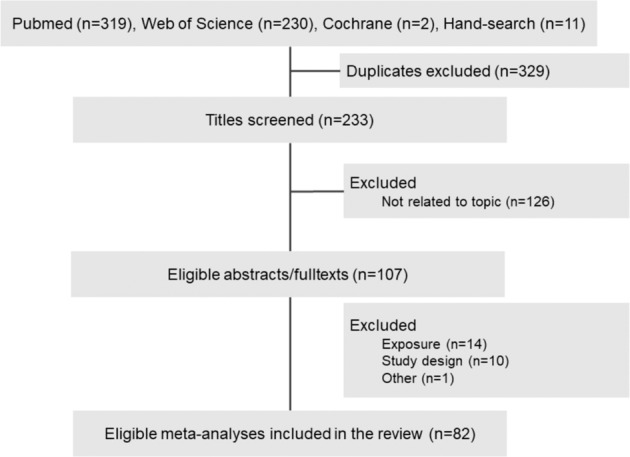

We searched Pubmed, Web of Science and Cochrane (between 1980 and 2020) with no language restrictions for papers on “green tea” and “meta-analysis” on February 6, 2020 resulting in 551 papers. We hand-searched the references of included papers to identify and include additional possibly relevant studies (n = 11). After excluding duplicates, 233 titles remained for screening (Fig. 1). Titles not related to the topic were excluded leaving 107 eligible abstracts. Articles were screened and grouped using Endnote and Rayyan QCRI [17]. After fulltext screening 82 meta-analyses were included in the review. Additionally we consulted the World Cancer Research Fund CUP and IARC Monographs for available expert evidence on cancer-related outcomes as well as major original recently published peer-reviewed papers.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of search strategy and selection of meta-analyses.

Cancer

The association between green tea consumption and total cancer risk is inconclusive [18–20]. A decreased risk of total cancer mortality was reported among Japanese women HR = 0.91 (0.85–0.98), but not men HR = 1.02 (0.89–1.10) [21].

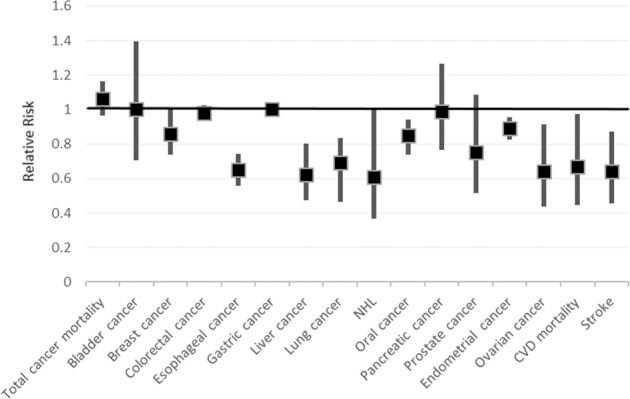

Figure 2 provides overall risk from most comprehensive and recent meta-analyses for each cancer site. Table 1 provides an overview of meta-analyses on green tea consumption and site-specific cancer risk [13, 21–78]. A 2020 meta-analysis on green tea and breast cancer including 16 studies reported a pooled relative risks of 0.86 (95% CI: 0.75–0.99) [34]. Among reproductive organ-related cancers, meta-analyses on endometrial cancer [78] and ovarian cancer reported inverse associations RR = 0.89 (95% CI 0.84–0.94) and RR = 0.64 (95% CI 0.45–0.90), respectively [76]. An inverse association was also found for lung cancer OR = 0.69 (95% CI 0.48–0.82) [58], non-Hodgkins lymphoma RR = 0.61 (95% CI 0.38–0.99) [62] and oral cancer RR = 0.85 (95% CI 0.75–0.93) [64].

Fig. 2. Green tea consumption and overall risk of cancer and cardiovascular disease from recent meta-analyses.

References of meta-analyses included in Fig. 2 [13, 14, 22, 26, 34, 40, 45, 54, 58, 62, 64, 65, 69, 76, 78]. Note: Colorectal, lung and pancreatic cancer risk reported as Odds Ratios.

Table 1.

Green tea consumption and summary risk of cancer from meta-analyses.

| Cancer site | Meta | Effect | Size | (95% CI) | Studies | Study design | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cancer mortality | 2 | HR | 1.02 | (0.89–1.10) men | 8 | Cohort | [21] |

| HR | 0.91 | (0.85–0.98) women | |||||

| RR | 1.06 | (0.98–1.15) | 6 | Cohort | [22] | ||

| Bladder cancer | 7 | OR | 0.81 | (0.68–0.98) | NA | Cohort | [23] |

| Case-control | |||||||

| OR | 0.95 | (0.73–1.24) | 3 | Cohort | [25] | ||

| 4 | Case-control | ||||||

| RR | 1.03 | (0.82–1.31) | 3 | Case-control | [28] | ||

| 2 | 2 Cohort | ||||||

| RR | 1 | (0.72–1.38) | 6 | NA | [26] | ||

| OR | 0.76 | (0.66–0.95) | 5 | NA | [24] | ||

| OR | 0.97 | (0.73–1.21) | 3 | Cohort | [27] | ||

| 2 | HCC | ||||||

| RR | 1.02 | (0.95–1.11) | 3 | Cohort | [13] | ||

| Breast cancer | 12 | OR | 0.85 | (0.80–0.92) | 5 | Case-control | [30] |

| 7 | Cohort | ||||||

| 2 | Follow-up | ||||||

| OR | 0.81 | (0.66–0.98) | 9 | Case-control | [35] | ||

| OR | 0.99 | (0.81–1.14) | 4 | Cohort | |||

| RR | 0.85 | (0.75–1.12) | 2 | Cohort | [31] | ||

| OR | 0.81 | (0.81–0.88) | 5 | Case-control | |||

| RR | 0.89 | (0.71–1.10) | 3 | Cohort | [36] | ||

| OR | 0.44 | (0.14–1.31) | 2 | Case-control | |||

| RR | 0.85 | (0.66–1.09) | 3 | Cohort | [32] | ||

| OR | 0.47 | (0.26–0.85) | 1 | Case-control | |||

| RR | 0.82 | (0.64–1.04) | 4 | Cohort | [37] | ||

| 5 | Case-control | ||||||

| OR | 0.9 | (0.75–1.10) | 7 | Case-control | [38] | ||

| RR | 1.03 | (0.96–1.10) | 4 | Cohort | |||

| OR | 0.79 | (0.65–0.95) | 3 | Cohort | [33] | ||

| 13 | Case-control | ||||||

| RR | 0.86 | (0.75–0.99) | 9 | Case-control | [34] | ||

| 7 | Cohort | ||||||

| RR | 0.97 | (0.90–1.06) | 4 | Cohort | [39] | ||

| OR | 0.83 | (0.72–0.96) | 14 | Case-control | [29] | ||

| RR | 0.99 | (0.96–1.02) | 4 | Cohort | [13] | ||

| Colorectal cancer | 6 | OR | 0.98 | (0.96–1.01) | 10 | Cohort/Case-control | [40] |

| RR | 0.97 | (0.97–1.16) | 4 | Cohort | [44] | ||

| OR | 0.74 | (0.63–0.86) | 4 | Case-control | |||

| OR | 0.95 | (0.81–1.11) | 13 | Case-control | [41] | ||

| RR | 0.9 | (0.72–1.08) | 6 | Cohort | [42] | ||

| RR | 1 | (0.94–1.07) | 5 | Cohort | [39] | ||

| RR | 0.98 | (0.95–1.02) colon | 5 | Cohort | [13] | ||

| RR | 1.01 | (0.98–1.05) rectum | |||||

| Esophageal cancer | 4 | RR | 1.09 | (0.76–1.55) total | 4 | PCC | [46] |

| 2 | HCC | ||||||

| 1 | Cohort | ||||||

| 5 | NCC | ||||||

| RR | 0.65 | (0.57–0.73) | 17 | Case-control | [12] | ||

| 3 | Cohort | ||||||

| RR/OR | 0.76 | (0.49–1.02) | 6 | PCC | [48] | ||

| 2 | Cohort | ||||||

| 2 | HCC | ||||||

| OR | 0.77 | (0.57–1.04) | 14 | Case-control | [47] | ||

| 2 | Cohort | ||||||

| Gastric cancer | 6 | OR | 1.05 | (0.90–1.21) | 5 | Cohort | [50] |

| OR | 0.84 | (0.74–0.95) | 8 | Case-control | |||

| RR | 1.56 | (0.93–2.60) | 4 | Cohort | [49] | ||

| OR | 1.12 | (0.70–1.77) | 4 | HCC | |||

| OR | 0.67 | (0.49–0.92) | 6 | PCC | |||

| RR | 1.00 | (0.98–1.02) | 8 | Cohort | [13] | ||

| RR | 1.04 | (0.93–1.17) | 5 | Cohort | [51] | ||

| OR | 0.73 | (0.64–0.83) | 8 | Case-control | |||

| RR | 0.99 | (0.94–1.05) | 4 | Cohort | [39] | ||

| RR | 1.03 | (0.92–1.16) | 7 | Cohort | [52] | ||

| OR | 0.74 | (0.63–0.86) | 11 | Case-control | |||

| Liver cancer | 6 | RR | 0.88 | (0.81–0.97) | 9 | Cohort | [53] |

| RR | 0.77 | (0.57–1.03) | 5 | Cohort | [56] | ||

| 3 | HCC | ||||||

| RR | 0.62 | (0.49–0.79) | 6 | Cohort | [54] | ||

| 4 | Case-control | ||||||

| RR | 0.93 | (0.75–1.17) | 3 | Cohort | [39] | ||

| RR | 0.99 | (0.97–1.01) | 6 | Cohort | [57] | ||

| 1 | Case-control | ||||||

| RR | 0.68 | (0.56–0.82) | 9 | Cohort | [55] | ||

| 3 | Retrospective | ||||||

| 1 | Cross-sectional | ||||||

| Lung cancer | 5 | OR | 0.69 | (0.48–0.82) | 7 | PCC | [58] |

| 3 | HCC | ||||||

| 4 | Cohort | ||||||

| NCC | |||||||

| RR | 0.75 | (0.62–0.91) | 4 | Cohort | [61] | ||

| 11 | Case-control | ||||||

| RR | 1.19 | (0.86–1.65) | 2 | Prospective | [13] | ||

| Observational | |||||||

| RR | 0.67 | (0.48–0.79) | 6 | NA | [60] | ||

| RR | 0.78 | (0.61–1.00) | 5 | Prospective | [59] | ||

| 7 | Case-control | ||||||

| NHL | 1 | RR | 0.61 | (0.38–0.99) | 2 | Cohort | [62] |

| 1 | Case-control | ||||||

| Oral cancer | 2 | RR | 0.85 | (0.75–0.93) | 12 | Case-control | [64] |

| 3 | Cohort | ||||||

| RR | 0.8 | (0.67–0.94) | 4 | Case-control | [63] | ||

| 1 | Cohort | ||||||

| Pancreatic cancer | 5 | OR | 1.15 | (0.89–1.48) | 4 | Cohort | [66] |

| RR | 1.01 | (0.84–1.20) | 11 | Cohort/case-control | [68] | ||

| OR | 0.96 | (0.79–1.16) | 4 | Cohort | [67] | ||

| 2 | PCC | ||||||

| 1 | HCC | ||||||

| OR | 0.99 | (0.78–1.25) | 5 | Cohort | [65] | ||

| 3 | Case-control | ||||||

| RR | 1.01 | (0.98–1.04) | 5 | Cohort | [13] | ||

| Prostate cancer | 6 | RR | 0.98 | (0.80–1.19) | 4 | Cohort | [69] |

| 0.45 | (0.25–0.82) | 3 | Case-control | ||||

| OR | 0.73 | (0.52–1.02) | 5 | Cohort | [72] | ||

| 4 | HCC | ||||||

| OR | 0.79 | (0.43–1.14) | 4 | Cohort | [70] | ||

| 1 | HCC | ||||||

| 4 | PCC | ||||||

| OR | 0.43 | (0.25–0.73) | 3 | Case-control | [71] | ||

| RR | 1 | (0.66–1.53) | 4 | Cohort | |||

| RR | 0.99 | (0.88–1.11) | 4 | Cohort | [39] | ||

| RR | 1.01 | (0.97–1.05) | 4 | Cohort | [13] | ||

| Endometrial cancer | 3 | OR | 0.78 | (0.62–0.98) | 5 | Case-control | [73] |

| 1 | Cohort | ||||||

| RR | 0.85 | (0.77–0.94) | 4 | NA | [77] | ||

| RR | 0.89 | (0.84–0.94) | 5 | Case-control | [78] | ||

| 1 | Cohort | ||||||

| Ovarian cancer | 4 | OR | 0.66 | (0.54–0.80) | 4 | Case-control | [73] |

| OR | 0.81 | (0.73–0.89) | 6 | Case-control | [74] | ||

| OR | 0.58 | (0.33–1.01) | 3 | Case-control | [75] | ||

| RR | 0.64 | (0.45–0.90) | 5 | Case-control | [76] |

Meta: number of meta-analyses; studies: number of original studies included; study design: study design of included original studies.

HCC hospital-based case-control study, NA not available, NCC nested-based case-control study, NHL non-Hodgkins lymphoma, PCC population based case-control.

A recent review of green tea and esophageal suggests an inverse association of RR = 0.65 (95% CI: 0.57–0.73) [45] contrary to previous reviews reporting null associations [46, 47]. Some individual studies suggest an increased risk of esophageal cancer among those consuming hot tea [79]. A 2017 review reports a null association with gastric cancer in cohort studies with an inverse association only among case-control studies OR = 0.84 (95% CI 0.74–0.95) [50]. This association may have possible gender differences [80]. An inverse association between green tea and liver cancer risk is supported by recent meta-analyses [53–55]. Some liver-related safety concerns have been raised such as, hepatotoxicity partially induced by green tea, however, a 2016 systematic review concluded that liver-related adverse events are rare [81]. A single original study reported that high doses of green tea may be associated with hepatoxicity due to raised alanine aminotransferase and bilirubin levels in humans [82].

Associations between green tea consumption and cancers of the bladder [26], colorectum [40], pancreas [65] and prostate [69] are not supported by recent meta-analyses. From a previous review, individual studies reported a 30–40% reduced risk of colon cancer conducted in Chinese and Japanese populations where a wider range of green tea intake exists [83].

Cardiovascular disease

Table 2 reports results from meta-analyses on green tea and cardiovascular-related outcomes [14, 21, 22, 84–87]. Three meta-analyses on green tea consumption and cardiovascular disease mortality support a reduced risk ranging between 18% and 33% [21, 22, 84] (Table 2). The findings from four other meta-analyses were similar for stroke incidence with a reduced risk of 17% to 36% [14, 84, 85]. While one meta-analysis on tea and coronary artery disease (CAD) including five studies on green tea reported a summary relative risk of 0.72 (95% CI 0.58–0.89) [87], a meta-analysis including a single original study reported a null association of RR = 1.02 (95% CI 0.92–1.13) for coronary heart disease (CHD) [84] (Table 2). The two terms are often used interchangeably however CHD is actually a result of CAD [88]. Another meta-analysis including nine studies reported an inverse association with myocardial infarction both in the 1–3 cup/day consumption group and greater than or equal to four cups but not for intracerebral hemorrhage, CVD and cerebral infarction [14] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Green tea consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease from meta-analyses.

| Category | Meta | Green tea | Effect | Size | (95% CI) | Studies | Study design | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular disease mortality | 3 | Highest vs lowest | RR | 0.67 | (0.46–0.96) | 6 | Cohort | [22] |

| ≥5 Cups per day | HR |

0.82 0.75 |

(0.75-0.90) men (0.68–0.84) women |

8 | Cohort | [21] | ||

| 3 Cups per day | RR | 0.81 | (0.68–0.97) | 6 | Prospective | [84] | ||

| Stroke | 4 | 3 Cups/day | RR | 0.78 | (0.69–0.88) | 3 | Mixed | [85] |

| 3 Cups Per day | RR | 0.83 | (0.72–0.96) | 5 | Cohort | [86] | ||

| 1–3 Cups vs <1 | OR | 0.64 | (0.47–0.86) | 3 | Cohort | [14] | ||

| 3 Cups per day | RR | 0.66 | (0.46–0.93) | 4 | Prospective | [84] | ||

| Coronary artery disease | 1 | Highest | RR | 0.72 | (0.58–0.89) |

2 3 |

Cohort case-control |

[87] |

| Coronary heart disease | 1 | 3 Cups per day | RR | 1.02 | (0.92–1.13) | 1 | Prospective | [84] |

| Myocardial infarction | 1 | 1–3 Cups vs <1 | OR | 0.81 | (0.67–0.98) | 2 | Cohort | [14] |

Meta: number of meta-analyses; studies: number of original studies included; study design, study design of included original studies.

Metabolic-related diseases

Table 3 shows the findings for type 2 diabetes-related markers, BMI-related outcomes, and blood pressure (systolic and diastolic) [89–106]. Three meta-analyses including randomized control trials (RCTs) [89–91] and one including cohort studies (2) [92] reported type 2 diabetes-related outcomes such as hemoglobin A1C(HbA1c), homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), fasting insulin and fasting glucose found no associations with green tea (Table 3). Other meta-analyses including RCTs reported an inverse association between green tea and fasting blood glucose (FBG) [93, 94] and HbA1c [94] specifically. A meta-analysis on alternative medicine for treatment of type 2 diabetes found one of three small trials reduced FBG, while three open label trials did not report a change in HbA1c values [95] (Table 3). In a 2009 review which included two original studies on green tea and type 2 diabetes mellitus [107], the Singapore Chinese Health Study reported a null association RR = 1.12(95% CI 0.98–1.29) for daily vs non [108] while the Japan Collaborative Cohort Study for Evaluation of Cancer Risk found a RR of 0.49 (95% CI 0.30–0.79) in women but not men RR = 0.91 (95%CI 0.55 to 1.52) in the ≥6 cups/day consumption category [109].

Table 3.

Green tea consumption and metabolic health outcomes from meta-analyses.

| Outcome | Meta | Green tea | Results | Studies | Study design | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes-related outcomes | 7 | 6 vs <1 cup/day | RR = 0.99 (0.97–1.24) | 2 | Cohort | [92] |

| Green tea/extract vs. placebo | Fasting plasma glucose: SMD = 0.04 (−0.15 to 0.24) | 7 | RCTs | [90] | ||

| Fasting serum insulin: SMD = −0.09 (0.30–0.11) | ||||||

| 2-h plasma glucose in the oral glucose tolerance test: SMD −0.14 (−0.63 to 0.34) | ||||||

| HbA1c: SMD = 0.10 (−0.13 to 0.33) | ||||||

| HOMA-IR: SMD = −0.06 (−0.35 to 0.23) | ||||||

| Green tea or green tea extract vs. placebo | HbA1c: SMD = −0.32 (−0.86 to 0.23) | 6 | RCTs | [89] | ||

| Insulin resistance SMD = −0.10 (−0.17 to 0.38) | ||||||

| Fasting insulin SMD = −0.25 (−0.64 to 0.15) | ||||||

| Fasting glucose SMD = −0.10 (−0.50 to 0.30) | ||||||

| Gtea vs. placebo/water | FBG: mean difference = −2.10 mg/dL (−3.93 to −0.27) | 11 | RCTs | [93] | ||

| Green tea | FBG: weighted mean difference: −0.09 mmol/L (−0.15, −0.03 mmol/L) | 17 | RCTs | [94] | ||

| HbA1c: weighted mean difference −0.30% (95% CI: −0.37, −0.22%) | ||||||

| Green tea | FBG: reduced levels in 1 of 3 small trials. | 3 | Human clinical trials | [95] | ||

| HbA1c: no change | ||||||

| Green tea or green tea extract | FBG: −0.07 (−0.60 to 0.47) | 8 | RCTs | [91] | ||

| FSI: 1.51 (0.05–2.97) | 6 | |||||

| HbA1c: −0.28 (−0.61 to 0.04) | 6 | |||||

| HOMA-IR: −0.00 (−0.68 to 0.68) | 5 | |||||

| BMI and fat | 7 | Green tea catechins | BMI: −0.55 (−0.65 to −0.40) | 15 | RCTs | [96] |

| Weight −1.38 kg (−1.70 to −1.06) | ||||||

| Daily green tea (EGCG 100 to 460 mg/day) | Body fat and body weight reduction periods of ≥12 weeks. caffeine doses between 80 and 300 mg/day has been shown to be an important factor | 15 | [97] | |||

| Catechins | Microcirc = −1.31 kg | 11 | Mixed | [99] | ||

| Green tea | No improvement in weight loss or maintenance | 2 | RCTs | [102] | ||

| Green tea preparations vs. control | Mean difference in weight loss of −0.04 kg (95% CI −0.5 to 0.4) non-Japanese | 14 | RCTs | [100] | ||

| Mean difference range −0.2 kg to −3.5 kg in Japanese | ||||||

| Green tea | Reduced weight −0.65 kg (−1.10 to −0.20) | 20 | RCTs | [101] | ||

| BMI −0.26 kg/m(2) (−0.43 to −0.10) | ||||||

| waist circumference −1.11 cm (−1.99 to −0.23) | ||||||

| Percent of body fat (PBF) (−1.42%, 95% CI: −3.02 to 0.18, P = 0.08) | ||||||

| Green tea catechin | Reduced total fat area: −17.7 cm2 (−20.9 to −14.4) | 6 | Human trials | [98] | ||

| Visceral fat area (−7.5 cm2, 95% CI: −9.3 to −5.7) | ||||||

| Subcutaneous fat area (−10.2 cm2, 95% CI: −12.5 to −7.8) | ||||||

| Blood pressure | 4 | Green tea | SBP: −2.08 mmHg (−3.06 to −1.05) | 13 | RCTs | [103] |

| DBP: −1.71 mmHg (−2.86, −0.56) | ||||||

| Green tea | SBP: 2.1 (− 2.9 to − 1.2) mmHg | 15 | RCTs | [104] | ||

| DBP: 1.7 (− 2.9 to − 0.5) | ||||||

| Green tea | SBP: MD: −1.94 mmHg (−2.95 to −0.93) | 20 | RCTs | [105] | ||

| Green tea vs control | SBP: −1.98 mmHg (−2.94 to −1.01 mmHg) | 13 | RCTs | [106] | ||

| DBP: −1.92 mmHg (−3.17 to −0.68 mmHg) |

BMI body mass index, DBP diastolic blood pressure, FBG fasting blood glucose, HbA1c glycosylated hemoglobin, HOMA-IR Homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance, meta number of meta-analyses, RCTs randomized control trial, SBP systolic blood pressure, SMD standardized mean difference.

Four meta-analysis on green tea reported a decrease in weight or BMI [96–98, 101] (Table 3). One meta-analysis found catechins had a small effect on weight loss [99] and a Cochrane systematic review found a small insignificant weight loss in overweight and obese adults [100]. Green tea (extract/capsule) did not show effect on prevention of weight regain [102] (Table 3). All four meta-analyses on the association between green tea and blood pressure reported reductions both in systolic and diastolic blood pressure [103–106]. One of these meta-analyses reported possible adverse events such as rash, elevated blood pressure and abdominal discomfort [105].

Other

Some evidence is available on green tea and dental or oral health. For example, a 2019 meta-analysis evaluating sanitization of toothbrushes including natural agents found garlic, green tea, and tea-tree oil sterilized toothbrushes with a mean difference of −483.34, CI (−914.79, −51.88) [110]. Only a few studies examined the association between green tea and respiratory diseases as well as external health outcomes [21, 111]. There is a dearth of studies on green tea consumption and cognitive-related outcomes, a 2017 meta-analysis suggests an inverse association, OR = 0.64 (95% CI 0.53–0.77) [112].

Discussion

This review concentrates on green tea consumption and major health outcomes such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, BMI, blood pressure, and others. Compared to the 2019 umbrella review [12] on tea and health outcomes, the current study includes type 2 diabetes-related outcomes, narrative reports, recent 2019 meta-analyses, published subsequent to the umbrella review and some recent individual studies. The overall risk sourced from the most comprehensive and recent meta-analysis on each health outcome is presented in Fig. 2.

Green tea was inversely associated with several site-specific cancers such as endometrial, lung, non-Hodgkins lymphoma, oral, and ovarian cancer, ranging from 19% to 42% reduced risk (Table 1). Mixed findings were observed for breast, esophageal, gastric, liver and mostly null association for colorectal, pancreatic, and prostate cancer (Table 1). This may also be due to the limited number of meta-analyses for some cancer sites. No studies reported cancer-related adverse effects specific to green tea consumption. Several mechanisms have been proposed by which green tea may affect cancer risk: polyphenol may inhibit cell proliferation and stimulate antioxidant activity [113, 114] leading to a decreased risk. Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) with other catechins could start apoptosis [20].

All included meta-analyses reporting cardiovascular disease-related outcomes reported inverse associations (Table 2) except for coronary heart disease. A 2013 narrative review supports these findings [115]. Mechanisms by which green tea may reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease are: polyphenols may exert antioxidant effects on the cardiovascular system [116], highest concentration of (−) EGCG [117], regulation of intermediary outcomes such as blood pressure, body fat [118], lipids [119], and improve glycemic control [120] which may improve cardiovascular health. Caffeine may contribute to regulating blood vessel homeostasis [121, 122].

Most studies on green tea and type 2 diabetes-related outcomes are RCTs. Previous reviews including meta-analyses on tea and diabetes did not always report results separately for green compared to other teas partially due to limited original papers [123]. The findings for green tea and diabetes-related health outcomes in this review were inconclusive with some studies suggesting reduced fasting blood glucose though this may largely vary depending on varies factors related to the exposure such as dose and duration as well as individual characteristics such as age, BMI and physical activity as well as other known risk factors of type 2 diabetes.

The findings of this review suggest a weak association between green tea and BMI and weight loss, though further studies are needed to confirm green’s potential therapeutic use for obesity [124]. BMI-related studies emphasize weight loss through via the following mechanisms. First, catechins inhibiting catechol-O-methyltransferase which stimulate the lipolytic route; second, modulation of gut microbiota, and third act on white adipose tissue, elevated in obesity, stores fatty acids [124, 125] (Fig. 1).

The current review provides a broad scope of integrated evidence from meta-analyses including original studies using various study designs such as cohort, case-controls studies and RCTs and reports. The main limitation is the lack of quantitative summary effects due to the large variety of data informing the study: study design, health outcomes, and exposure categories. In addition, data were scarce on certain health outcomes of interest such as cognitive and oral health.

The evidence on green tea consumption and health outcomes presented in this review suggests green tea may be favorable for cardiovascular disease, particularly stroke, and certain cancers such as endometrial, esophageal, lung, non-Hodgkins lymphoma, oral, and ovarian cancer. More evidence is needed to assess the impact of green tea on breast, gastric, and liver cancer risk. Additional studies could also help clarify the suggested null association with certain cancer sites: colorectal, pancreatic, and prostate cancer. Possible minor adverse events on health from green tea consumption were reported in one study, however these must be interpreted cautiously within the study context and possible finer dose-response implications. The findings for green tea and diabetes risk were inconclusive. For BMI the current evidence suggests a possible weak association, while the evidence is stronger supporting a decrease in blood pressure from green tea. More studies investigating a possible association between green tea consumption and other health outcomes such as cognition, injuries, respiratory disease would be informative to more completely assess the impact of green tea on human health.

In conclusion, our review suggests green tea may have health benefits especially for cardiovascular disease and certain cancer sites.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was supported by the National Cancer Center Research and Development Funds (30-A-15).

Author contributions

SKA designed the research, compiled the findings and drafted the manuscript. MI checked the manuscript for intellectual content.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Graham HN. Green tea composition, consumption, and polyphenol chemistry. Prev Med. 1992;21:334–50. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(92)90041-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Non-alcoholic drinks and the risk of cancer. In: Continuous Update Project Expert Report 2018; 2018. Available at dietandcancerreport.org. https://www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Non-alcoholic-drinks.pdf.

- 3.International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans, volume 51. Coffee, tea, mate, methylxanthines and methylglyoxal. Lyon: IARC; 1991. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Huang J, Wang Y, Xie Z, Zhou Y, Zhang Y, Wan X. The anti-obesity effects of green tea in human intervention and basic molecular studies. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2014;68:1075–87. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2014.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xing L, Zhang H, Qi R, Tsao R, Mine Y. Recent advances in the understanding of the health benefits and molecular mechanisms associated with green tea polyphenols. J Agric Food Chem. 2019;67:1029–43. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b06146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dona M, Dell’Aica I, Calabrese F, Benelli R, Morini M, Albini A, et al. Neutrophil restraint by green tea: inhibition of inflammation, associated angiogenesis, and pulmonary fibrosis. J Immunol. 2003;170:4335–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.4335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sudano Roccaro A, Blanco AR, Giuliano F, Rusciano D, Enea V. Epigallocatechin-gallate enhances the activity of tetracycline in staphylococci by inhibiting its efflux from bacterial cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1968–73. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.6.1968-1973.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinreb O, Mandel S, Amit T, Youdim MB. Neurological mechanisms of green tea polyphenols in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. J Nutr Biochem. 2004;15:506–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raederstorff DG, Schlachter MF, Elste V, Weber P. Effect of EGCG on lipid absorption and plasma lipid levels in rats. J Nutr Biochem. 2003;14:326–32. doi: 10.1016/s0955-2863(03)00054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and cancer: a global persepective. Continuous Update Project Expert Report 2018; 2018. Available at dietandcancerreport.org.

- 11.Chacko SM, Thambi PT, Kuttan R, Nishigaki I. Beneficial effects of green tea: a literature review. Chin Med. 2010;5:13.. doi: 10.1186/1749-8546-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yi M, Wu X, Zhuang W, Xia L, Chen Y, Zhao R, et al. Tea consumption and health outcomes: umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies in humans. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2019;63:e1900389.. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201900389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang YF, Xu Q, Lu J, Wang P, Zhang HW, Zhou L, et al. Tea consumption and the incidence of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2015;24:353–62. doi: 10.1097/cej.0000000000000094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pang J, Zhang Z, Zheng TZ, Bassig BA, Mao C, Liu X, et al. Green tea consumption and risk of cardiovascular and ischemic related diseases: a meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2016;202:967–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.12.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poole R, Kennedy OJ, Roderick P, Fallowfield JA, Hayes PC, Parkes J. Coffee consumption and health: umbrella review of meta-analyses of multiple health outcomes. BMJ. 2017;359:j5024.. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j5024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gardner EJ, Ruxton CH, Leeds AR. Black tea–helpful or harmful? A review of the evidence. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2007;61:3–18. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ouzzani MHH, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5:210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boehm K, Borrelli F, Ernst E, Habacher G, Hung SK, Milazzo S, et al. Green tea (Camellia sinensis) for the prevention of cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009; CD005004. 10.1002/14651858.CD005004.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Johnson R, Bryant S, Huntley AL. Green tea and green tea catechin extracts: an overview of the clinical evidence. Maturitas. 2012;73:280–7. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eisenstein M. Tea’s value as a cancer therapy is steeped in uncertainty. Nature. 2019;566:S6. doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-00397-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abe SK, Saito E, Sawada N, Tsugane S, Ito H, Lin Y, et al. Green tea consumption and mortality in Japanese men and women: a pooled analysis of eight population-based cohort studies in Japan. Eur J Epidemiol. 2019. 10.1007/s10654-019-00545-y. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Tang J, Zheng JS, Fang L, Jin Y, Cai W, Li D. Tea consumption and mortality of all cancers, CVD and all causes: a meta-analysis of eighteen prospective cohort studies. Br J Nutr. 2015;114:673–83. doi: 10.1017/S0007114515002329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang X, Lin YW, Wang S, Wu J, Mao QQ, Zheng XY, et al. A meta-analysis of tea consumption and the risk of bladder cancer. Urol Int. 2013;90:10–16. doi: 10.1159/000342804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bai Y, Yuan H, Li J, Tang Y, Pu C, Han P. Relationship between bladder cancer and total fluid intake: a meta-analysis of epidemiological evidence. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:223. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-12-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weng H, Zeng XT, Li S, Kwong JS, Liu TZ, Wang XH. Tea consumption and risk of bladder cancer: a dose-response meta-analysis. Front Physiol. 2016;7:693.. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hong X, Xu Q, Lan K, Huang H, Zhang Y, Chen S, et al. The effect of daily fluid management and beverages consumption on the risk of bladder cancer: a meta-analysis of observational study. Nutr Cancer. 2018;70:1217–27. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2018.1512636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qin J, Xie B, Mao Q, Kong D, Lin Y, Zheng X. Tea consumption and risk of bladder cancer: a meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:172.. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-10-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu S, Li F, Huang X, Hua Q, Huang T, Liu Z, et al. The association of tea consumption with bladder cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2013;22:128–37. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.2013.22.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu S, Zhu L, Wang K, Yan Y, He J, Ren Y. Green tea consumption and risk of breast cancer: a systematic review and updated meta-analysis of case-control studies. Medicine. 2019;98:e16147.. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000016147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gianfredi V, Nucci D, Abalsamo A, Acito M, Villarini M, Moretti M, et al. Green tea consumption and risk of breast cancer and recurrence—a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutrients. 2018; 10. 10.3390/nu10121886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Ogunleye AA, Xue F, Michels KB. Green tea consumption and breast cancer risk or recurrence: a meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;119:477–84. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0415-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun CL, Yuan JM, Koh WP, Yu MC. Green tea, black tea and breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:1310–5. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao Y, Huang YB, Liu XO, Chen C, Dai HJ, Song FJ, et al. Tea consumption, alcohol drinking and physical activity associations with breast cancer risk among Chinese females: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:7543–50. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.12.7543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Y, Zhao Y, Chong F, Song M, Sun Q, Li T, et al. A dose-response meta-analysis of green tea consumption and breast cancer risk. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2020:1–12. 10.1080/09637486.2020.1715353. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Najaf Najafi M, Salehi M, Ghazanfarpour M, Hoseini ZS, Khadem-Rezaiyan M. The association between green tea consumption and breast cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Phytother Res. 2018;32:1855–64. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seely D, Mills EJ, Wu P, Verma S, Guyatt GH. The effects of green tea consumption on incidence of breast cancer and recurrence of breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Integr Cancer Ther. 2005;4:144–55. doi: 10.1177/1534735405276420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu Y, Zhang D, Kang S. Black tea, green tea and risk of breast cancer: an update. Springerplus. 2013;2:240.. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-2-240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang SK, Xiao HM, Xia H, Sun GJ. Tea consumption and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pharm Ther. 2018;56:617–9. doi: 10.5414/cp203303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu F, Jin Z, Jiang H, Xiang C, Tang J, Li T, et al. Tea consumption and the risk of five major cancers: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:197.. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen Y, Wu Y, Du M, Chu H, Zhu L, Tong N, et al. An inverse association between tea consumption and colorectal cancer risk. Oncotarget. 2017;8:37367–76. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang XJ, Zeng XT, Duan XL, Zeng HC, Shen R, Zhou P. Association between green tea and colorectal cancer risk: a meta-analysis of 13 case-control studies. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:3123–7. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.7.3123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang ZH, Gao QY, Fang JY. Green tea and incidence of colorectal cancer: evidence from prospective cohort studies. Nutr Cancer. 2012;64:1143–52. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2012.718031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Wu X, Xiang M, Ma Y. Tea consumption reduces the incidence of gallbladder cancer based on a meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. Sci China Life Sci. 2015;58:922–4. doi: 10.1007/s11427-015-4896-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun CL, Yuan JM, Koh WP, Yu MC. Green tea, black tea and colorectal cancer risk: a meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:1301–9. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yi Y, Liang H, Jing H, Jian Z, Guang Y, Jun Z, et al. Green tea consumption and esophageal cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Nutr Cancer. 2019:1–9. 10.1080/01635581.2019.1636101. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Sang LX, Chang B, Li XH, Jiang M. Green tea consumption and risk of esophageal cancer: a meta-analysis of published epidemiological studies. Nutr Cancer. 2013;65:802–12. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2013.805423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zheng JS, Yang J, Fu YQ, Huang T, Huang YJ, Li D. Effects of green tea, black tea, and coffee consumption on the risk of esophageal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Cancer. 2013;65:1–16. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2013.741762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zheng P, Zheng HM, Deng XM, Zhang YD. Green tea consumption and risk of esophageal cancer: a meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:165.. doi: 10.1186/1471-230x-12-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou Y, Li N, Zhuang W, Liu G, Wu T, Yao X, et al. Green tea and gastric cancer risk: meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2008;17:159–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang Y, Chen H, Zhou L, Li G, Yi D, Zhang Y, et al. Association between green tea intake and risk of gastric cancer: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20:3183–92. doi: 10.1017/s1368980017002208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Myung SK, Bae WK, Oh SM, Kim Y, Ju W, Sung J, et al. Green tea consumption and risk of stomach cancer: a meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:670–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kang H, Rha SY, Oh KW, Nam CM. Green tea consumption and stomach cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Epidemiol Health. 2010;32:e2010001.. doi: 10.4178/epih/e2010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang YQ, Lu X, Min H, Wu QQ, Shi XT, Bian KQ, et al. Green tea and liver cancer risk: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies in Asian populations. Nutrition. 2016;32:3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2015.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ni CX, Gong H, Liu Y, Qi Y, Jiang CL, Zhang JP. Green tea consumption and the risk of liver cancer: a meta-analysis. Nutr Cancer. 2017;69:211–20. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2017.1263754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yin X, Yang J, Li T, Song L, Han T, Yang M, et al. The effect of green tea intake on risk of liver disease: a meta analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:8339–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fon Sing M, Yang WS, Gao S, Gao J, Xiang YB. Epidemiological studies of the association between tea drinking and primary liver cancer: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2011;20:157–65. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e3283447497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tanaka K, Tamakoshi A, Sugawara Y, Mizoue T, Inoue M, Sawada N, et al. Coffee, green tea and liver cancer risk: an evaluation based on a systematic review of epidemiologic evidence among the Japanese population. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2019;49:972–84. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyz097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guo Z, Jiang M, Luo W, Zheng P, Huang H, Sun B. Association of lung cancer and tea-drinking habits of different subgroup populations: meta-analysis of case-control studies and cohort studies. Iran J Public Health. 2019;48:1566–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tang N, Wu Y, Zhou B, Wang B, Yu R. Green tea, black tea consumption and risk of lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Lung Cancer. 2009;65:274–83. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang Y, Yu X, Wu Y, Zhang D. Coffee and tea consumption and risk of lung cancer: a dose-response analysis of observational studies. Lung Cancer. 2012;78:169–70. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang L, Zhang X, Liu J, Shen L, Li Z. Tea consumption and lung cancer risk: a meta-analysis of case-control and cohort studies. Nutrition. 2014;30:1122–7. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2014.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mirtavoos-Mahyari H, Salehipour P, Parohan M, Sadeghi A. Effects of coffee, black tea and green tea consumption on the risk of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Cancer. 2019;71:887–97. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2019.1595055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang W, Yang Y, Zhang W, Wu W. Association of tea consumption and the risk of oral cancer: a meta-analysis. Oral Oncol. 2014;50:276–81. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu Q, Jiao Y, Zhao Y, Wang YR, Li J, Ma S, et al. Tea consumption reduces the risk of oral cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2016;9:2688–97. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zeng JL, Li ZH, Wang ZC, Zhang HL. Green tea consumption and risk of pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2014;6:4640–50. doi: 10.3390/nu6114640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wei J, Chen L, Zhu X. Tea drinking and risk of pancreatic cancer. Chin Med J. 2014;127:3638–44. doi: 10.1097/00029330-201409200-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chang B, Sang L, Wang Y, Tong J, Wang BY. Consumption of tea and risk for pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis of published epidemiological studies. Nutr Cancer. 2014;66:1109–23. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2014.951730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen K, Zhang Q, Peng M, Shen Y, Wan P, Xie G. Relationship between tea consumption and pancreatic cancer risk: a meta-analysis based on prospective cohort studies and case-control studies. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2014;23:353–60. doi: 10.1097/cej.0000000000000033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Guo Y, Zhi F, Chen P, Zhao K, Xiang H, Mao Q, et al. Green tea and the risk of prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2017;96:e6426.. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000006426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lin YW, Hu ZH, Wang X, Mao QQ, Qin J, Zheng XY, et al. Tea consumption and prostate cancer: an updated meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:38.. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-12-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zheng J, Yang B, Huang T, Yu Y, Yang J, Li D. Green tea and black tea consumption and prostate cancer risk: an exploratory meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Cancer. 2011;63:663–72. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2011.570895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fei X, Shen Y, Li X, Guo H. The association of tea consumption and the risk and progression of prostate cancer: a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:3881–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Butler LM, Wu AH. Green and black tea in relation to gynecologic cancers. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2011;55:931–40. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201100058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gao M, Ma W, Chen XB, Chang ZW, Zhang XD, Zhang MZ. Meta-analysis of green tea drinking and the prevalence of gynecological tumors in women. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2013;25(Suppl 4):43s–48s. doi: 10.1177/1010539513493313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nagle CM, Olsen CM, Bain CJ, Whiteman DC, Green AC, Webb PM. Tea consumption and risk of ovarian cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21:1485–91. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9577-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang D, Kaushiva A, Xi Y, Wang T, Li N. Non-herbal tea consumption and ovarian cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational epidemiologic studies with indirect comparison and dose-response analysis. Carcinogenesis. 2018;39:808–18. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgy048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tang NP, Li H, Qiu YL, Zhou GM, Ma J. Tea consumption and risk of endometrial cancer: a metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201:605.e601–608. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhou Q, Li H, Zhou JG, Ma Y, Wu T, Ma H. Green tea, black tea consumption and risk of endometrial cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;293:143–55. doi: 10.1007/s00404-015-3811-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Islami F, Poustchi H, Pourshams A, Khoshnia M, Gharavi A, Kamangar F, et al. A prospective study of tea drinking temperature and risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2019. 10.1002/ijc.32220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 80.Inoue M, Sasazuki S, Wakai K, Suzuki T, Matsuo K, Shimazu T, et al. Green tea consumption and gastric cancer in Japanese: a pooled analysis of six cohort studies. Gut. 2009;58:1323–32. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.166710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Isomura T, Suzuki S, Origasa H, Hosono A, Suzuki M, Sawada T, et al. Liver-related safety assessment of green tea extracts in humans: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70:1221–9. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2016.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mazzanti G, Menniti-Ippolito F, Moro PA, Cassetti F, Raschetti R, Santuccio C, et al. Hepatotoxicity from green tea: a review of the literature and two unpublished cases. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65:331–41. doi: 10.1007/s00228-008-0610-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhang X, Albanes D, Beeson WL, van den Brandt PA, Buring JE, Flood A, et al. Risk of colon cancer and coffee, tea, and sugar-sweetened soft drink intake: pooled analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:771–83. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhang C, Qin YY, Wei X, Yu FF, Zhou YH, He J. Tea consumption and risk of cardiovascular outcomes and total mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Eur J Epidemiol. 2015;30:103–13. doi: 10.1007/s10654-014-9960-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Arab L, Liu W, Elashoff D. Green and black tea consumption and risk of stroke: a meta-analysis. Stroke. 2009;40:1786–92. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.108.538470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shen L, Song LG, Ma H, Jin CN, Wang JA, Xiang MX. Tea consumption and risk of stroke: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2012;13:652–62. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1201001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wang ZM, Zhou B, Wang YS, Gong QY, Wang QM, Yan JJ, et al. Black and green tea consumption and the risk of coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:506–15. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.005363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.American Heart Association. Coronary artery disease - coronary heart disease. (American Heart Association, 2015). https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/consumer-healthcare/what-is-cardiovascular-disease/coronaryartery-disease.

- 89.Yu J, Song P, Perry R, Penfold C, Cooper AR. The effectiveness of green tea or green tea extract on insulin resistance and glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab J. 2017;41:2510–262. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2017.41.4.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang X, Tian J, Jiang J, Li L, Ying X, Tian H, et al. Effects of green tea or green tea extract on insulin sensitivity and glycaemic control in populations at risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2014;27:501–12. doi: 10.1111/jhn.12181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Li Y, Wang C, Huai Q, Guo F, Liu L, Feng R, et al. Effects of tea or tea extract on metabolic profiles in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of ten randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2016;32:2–10. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yang WS, Wang WY, Fan WY, Deng Q, Wang X. Tea consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes: a dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. Br J Nutr. 2014;111:1329–39. doi: 10.1017/s0007114513003887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kondo Y, Goto A, Noma H, Iso H, Hayashi K, Noda M. Effects of coffee and tea consumption on glucose metabolism: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2018;11. 10.3390/nu11010048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 94.Liu K, Zhou R, Wang B, Chen K, Shi LY, Zhu JD, et al. Effect of green tea on glucose control and insulin sensitivity: a meta-analysis of 17 randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98:340–8. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.052746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Nahas R, Moher M. Complementary and alternative medicine for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:591–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Phung OJ, Baker WL, Matthews LJ, Lanosa M, Thorne A, Coleman CI. Effect of green tea catechins with or without caffeine on anthropometric measures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:73–81. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Vazquez Cisneros LC, Lopez-Uriarte P, Lopez-Espinoza A, Navarro Meza M, Espinoza-Gallardo AC, Guzman Aburto MB. Effects of green tea and its epigallocatechin (EGCG) content on body weight and fat mass in humans: a systematic review. Nutr Hosp. 2017;34:731–7. doi: 10.20960/nh.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hibi M, Takase H, Iwasaki M, Osaki N, Katsuragi Y. Efficacy of tea catechin-rich beverages to reduce abdominal adiposity and metabolic syndrome risks in obese and overweight subjects: a pooled analysis of 6 human trials. Nutr Res. 2018;55:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2018.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hursel R, Viechtbauer W, Westerterp-Plantenga MS. The effects of green tea on weight loss and weight maintenance: a meta-analysis. Int J Obes. 2009;33:956–61. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Jurgens TM, Whelan AM, Killian L, Doucette S, Kirk S, Foy E. Green tea for weight loss and weight maintenance in overweight or obese adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:Cd008650.. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008650.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Golzarand M, Toolabi K, Aghasi M. Effect of green tea, caffeine and capsaicin supplements on the anthropometric indices: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Funct Food. 2018;46:320–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2018.04.002.. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.van Baak MA, Mariman ECM. Dietary strategies for weight loss maintenance. Nutrients. 2019;11. 10.3390/nu11081916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 103.Khalesi S, Sun J, Buys N, Jamshidi A, Nikbakht-Nasrabadi E, Khosravi-Boroujeni H. Green tea catechins and blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Eur J Nutr. 2014;53:1299–311. doi: 10.1007/s00394-014-0720-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Liu G, Mi XN, Zheng XX, Xu YL, Lu J, Huang XH. Effects of tea intake on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Nutr. 2014;112:1043–54. doi: 10.1017/s0007114514001731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Onakpoya I, Spencer E, Heneghan C, Thompson M. The effect of green tea on blood pressure and lipid profile: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;24:823–36. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2014.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Peng X, Zhou R, Wang B, Yu X, Yang X, Liu K, et al. Effect of green tea consumption on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials. Sci Rep. 2014;4:6251.. doi: 10.1038/srep06251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Huxley R, Lee CM, Barzi F, Timmermeister L, Czernichow S, Perkovic V, et al. Coffee, decaffeinated coffee, and tea consumption in relation to incident type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:2053–63. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Odegaard AO, Pereira MA, Koh WP, Arakawa K, Lee HP, Yu MC. Coffee, tea, and incident type 2 diabetes: the Singapore Chinese Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:979–85. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.4.979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Iso H, Date C, Wakai K, Fukui M, Tamakoshi A, Group JS. The relationship between green tea and total caffeine intake and risk for self-reported type 2 diabetes among Japanese adults. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:554–62. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-8-200604180-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Agrawal SK, Dahal S, Bhumika TV, Nair NS. Evaluating sanitization of toothbrushes using various decontamination methods: a meta-analysis. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2019;16:364–71. doi: 10.33314/jnhrc.v16i41.1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Oh CM, Oh IH, Choe BK, Yoon TY, Choi JM, Hwang J. Consuming green tea at least twice each day is associated with reduced odds of chronic obstructive lung disease in middle-aged and older korean adults. J Nutr. 2018;148:70–76. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxx016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Liu X, Du X, Han G, Gao W. Association between tea consumption and risk of cognitive disorders: a dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies. Oncotarget. 2017;8:43306–21. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Yang CS, Lee MJ, Chen L, Yang GY. Polyphenols as inhibitors of carcinogenesis. Environ Health Perspect. 1997;105(Suppl 4):971–6. doi: 10.1289/ehp.97105s4971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yang CS, Wang X, Lu G, Picinich SC. Cancer prevention by tea: animal studies, molecular mechanisms and human relevance. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:429–39. doi: 10.1038/nrc2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.van Dam RM, Naidoo N, Landberg R. Dietary flavonoids and the development of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases: review of recent findings. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2013;24:25–33. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e32835bcdff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wang H, Provan G, Helliwell K. The functional benefits of flavonoids: the case of tea. In: Johnson I, Williamson G, editors. Phytochemical funtional foods. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Schneider C, Segre T. Green tea: potential health benefits. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79:591–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Nagao T, Hase T, Tokimitsu I. A green tea extract high in catechins reduces body fat and cardiovascular risks in humans. Obesity. 2007;15:1473–83. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Zheng XX, Xu YL, Li SH, Liu XX, Hui R, Huang XH. Green tea intake lowers fasting serum total and LDL cholesterol in adults: a meta-analysis of 14 randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94:601–10. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.010926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Zheng XX, Xu YL, Li SH, Hui R, Wu YJ, Huang XH. Effects of green tea catechins with or without caffeine on glycemic control in adults: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97:750–62. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.032573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Zucchi R, Ronca-Testoni S. The sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ channel/ryanodine receptor: modulation by endogenous effectors, drugs and disease states. Pharmacol Rev. 1997;49:1–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Spyridopoulos I, Fichtlscherer S, Popp R, Toennes SW, Fisslthaler B, Trepels T, et al. Caffeine enhances endothelial repair by an AMPK-dependent mechanism. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1967–74. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.174060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Yang J, Mao QX, Xu HX, Ma X, Zeng CY. Tea consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis update. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e005632.. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Ferreira MA, Silva DM, de Morais AC, Jr., Mota JF, Botelho PB. Therapeutic potential of green tea on risk factors for type 2 diabetes in obese adults—a review. Obes Rev. 2016;17:1316–28. doi: 10.1111/obr.12452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ali AT, Hochfeld WE, Myburgh R, Pepper MS. Adipocyte and adipogenesis. Eur J Cell Biol. 2013;92:229–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]