Highlights

-

•

Impulsivity mediates the effect of childhood adversity on addictive behaviors.

-

•

Mediation part of impulsivity is higher with exposure to intra-familial violence.

-

•

Great mediation part of impulsivity (37.5%) for cyberaddiction.

-

•

Screening addictive behaviors among impulsive youth is needed.

Keywords: Impulsive behavior, Adverse childhood experiences, Health risk behaviors, Adolescent, Tunisia

Abstract

Adverse childhood experience (ACE) has become an alarming phenomenon exposing youth at a great risk of developing mental health issues. Several studies have examined the mechanism by which ACE affects adolescent’s engagement in risky behaviors. However, little is known about these associations in the Tunisian/African context. We investigated the role of impulsivity in the link between ACE and health risk behaviors among schooled adolescents in Tunisia.

We performed a cross sectional study among 1940 schooled adolescents in the city of Mahdia (Tunisia) from January to February 2020. To measure ACE, we used the validated Arabic version of the World Health Organization ACE questionnaire. The Barratt Impulsivity Scale and the Internet Addiction Test were used as screening tools for impulsivity and internet addiction.

A total of 2520 adolescents were recruited. Of those, 1940 returned the questionnaires with an overall response rate of 77%. The majority (97.5%) reported experiencing at least one ACE. Emotional neglect (83.2%) and witnessing community violence (73.5%) were the most reported intra-familial ACEs. Males had higher rates of exposure to social violence than females. The most common risky behavior was internet addiction (50%, 95%CI = [47.9–52.3%]). Our survey revealed that ACEs score predict problematic behaviors through impulsiveness (% mediated = 16.7%). Specifically, we found a major mediating role of impulsivity between the exposure to ACE and the risk of internet addiction (% mediated = 37.5%).

Our results indicate the role of impulsivity in translating the risk associated with ACE leading to engagement in high risk behaviors.

1. Introduction

Adverse childhood experiences (ACE) including exposure to physical, emotional or sexual abuse and social violence are linked to wide variety of harmful health effects in adolescence and later life (Witt et al., 2019). Adolescence is a critical period for engagement in chemical and behavioral addictions such as substance use and internet addiction, which hold a defining role in adulthood (Throuvala et al., 2019, Li et al., 2019). ACE exposure during this period may predispose individuals for risk taking behaviors. Research conducted in the US with 8667 adults revealed that increased number of childhood abuse categories was associated to a decreased mental health quality (Edwards et al., 2003). Numerous research focused on studying the relationship between ACEs and substance use revealing that as the number of adversities increase, the risk for drug use increase (Adverse Childhood Experiences, Hughes et al., 2017) with significant impact on the individuals and families (Kazdouh et al., 2019, Shore* H, 2015, Duke, 2018). However, few recent studies have explored ACE’s contribution in increasing online behavioral addictions (Wilke et al., 2020, Li et al., 2020). Internet addiction is a growing behavioral concern particularly among adolescents (Li et al., 2020), and this may increase risk for psychiatric disorders such as depression (Lam, 2014); physical problems and poor academic performance (Li et al., 2019).

The mechanism by which ACE affect adolescent’s behavioral problems have been well studied (Robles et al., 2019). Few mediators have been investigated in current literature. One of the mechanisms that have been evaluated is impulsivity, defined as actions without foresight that are poorly conceived, prematurely expressed, unnecessarily risky and inappropriate to the situation (Edition and Association, 2013). Research suggest that inclusion of impulsivity may explain effects of ACE on behavioral outcome later in life (Ziada et al., 2020). This may also apply to adolescents’ behaviors (Abdelraheem et al., 2019). Also, a recent study found an association between Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) symptoms and substance use mediated by impulsive personality traits (Morris et al., 2020). Yet this connection has not been studies outside of Western countries (Ziada et al., 2020). Most studies in Tunisia (Feki et al., 2016, Khemakhem et al., 2017) and worldwide (Brumley et al., 2017) have focused on impulsivity among youth with brain damage but not in a community sample. Studying this issue is needed in the Tunisian context in light of increased risk for exposure to violence (El Mhamdi et al., 2017).

Examining the role of impulsivity as a contributing factor connecting ACE to risk-taking behaviors among adolescents could enhance our knowledge about ways to address the impact of ACE. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in North Africa and Middle East world that aimed at investigating the link between ACE and risk behaviors (internet addiction and substance use) mediated by impulsivity among adolescents in the city of Mahdia, Tunisia.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population and sampling

We performed a cross sectional study from January to February 2020, among adolescents enrolled in all secondary schools of the city of Mahdia in Tunisia.

We randomly selected fours classes from each educational level. All students in selected classes who accepted to respond to the questionnaire were included.

The minimal sample size required for the study was 1068 adolescents based on 0.05 probability of type one error (α), an accuracy of 3% and frequency of experiencing childhood adversities of 49.7% according to literature (Adverse childhood experiences survey among university students in Turkey, 2014).

2.2. Data collection and study instruments

Trained doctors were present in classrooms to explain the purpose of the study and assist filling in the questionnaires. Incompletely filled-in questionnaires were eliminated from the study.

2.2.1. Measurement of childhood adversities

Data were collected using the Adverse childhood experiences-International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ) that was developed by the WHO. In 2012, it was translated and validated in Saudi Arabia (Almuneef et al., 2014). It was also adapted to the Tunisian adolescent context by modifying some words to make them consistent with the Tunisian dialect.

The ACE-IQ is about adversities related to the respondents’ first 18 years of life. It includes nine categories divided in two sections:

Intra-familial ACEs (Six categories): including emotional and physical neglect; household dysfunction; emotional and physical abuse; sexual abuse.

Social ACEs (three categories): including peer violence; witnessing community violence and exposure to war/collective violence.

For each adversity, if the participant answered in the affirmative (once, a few times or many times) this counts as a yes according to the ACE scoring provided by WHO (5). Binary scores are then used to compute the six intrafamilial ACEs and three social ACEs (ACE score range from 0 to 9).

2.2.2. Measurement of health risk behaviors

Internet addiction was evaluated via the validated Arabic version of the Internet Addiction Test (IAT) (Hawi, 2013).

Substance use: The Arabic version of the ACE-IQ tool included the CDC Health Appraisal Questionnaire (Al-Shawi and Lafta, 2015) which contains questions about tobacco use, alcohol consumption and illicit drug use (cannabis). Respondents report whether or not (yes/no) had ever been a smoker or used cannabis.

2.2.3. Measurement of impulsivity and common mental health disorders

2.2.3.1. Impulsivity

-Impulsiveness can be assessed by self-report questionnaires such as the Barratt Impulsivity Scale (BIS-11) showing high convergent validity and commonly used in both research and clinical settings (Patton et al., 1995). The BIS-11 is a 30 item questionnaire translated and validated in Tunisia (Ellouze et al., 2013).

-Responses were classified through a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 = Rarely/Never to 4 = Almost Always/Always. Total scores of 72 or higher signify high impulsivity. Although the measure has several subscales, the current study focused on participants' total impulsivity score.

Depression and anxiety were screened using the validated Arabic version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Terkawi et al., 2017). It consists of two scores for anxiety and depression, each containing seven items on a 4-point Likert scale (0–3). HADS is scored by summing up the ratings for the seven items of each subscale. The cut-off is 11 for participants who screened positive for anxiety/depression.

2.3. Statistical analyses

Data analyses were conducted using SPSS version 21. Qualitative variables were represented by absolute and relative frequencies and quantitative ones were represented by means and standard deviations (SD). Chi square and Student tests were used to compare percentages and means, respectively.

The rate of each category of ACEs was assessed by gender. The number of experiences was categorized into 0, 1–2, 3–4 and ≥ 5.

Health risk behaviors (internet addiction and substance use) were coded zero for people who did not experience any type of risky behavior and one if experienced at least one. Missing data were excluded from analyses.

A logistic regression analysis was used to estimate the crude likelihood of having health risk behaviors by the number of ACEs; then adjusted to demographic characteristics (age and gender) and to common mental disorders (anxiety and depression).

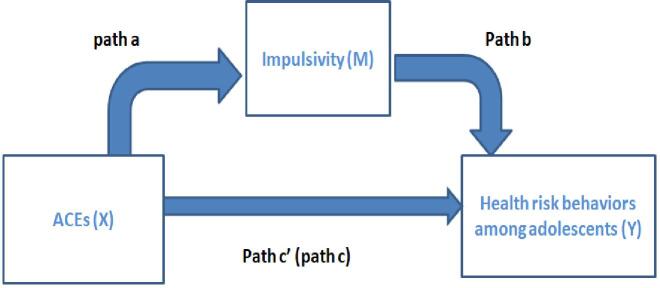

2.3.1. Mediation analysis (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1.

Diagram of the theoretical relationship between ACEs (cummulative number of Adverse Childhood Experiences) and health risk behaviours with impulsivity as mediator.

The mediation analysis is one of the more practical ways to investigate the indirect effect of an independent variable on a dependent variable through a mediator. Impulsivity (Barratt scale) as a continuous variable was explored as potential mediator in this analysis. Spearman correlations were used to assess the zero-order relationships among ACE, Impulsivity and health risk behaviors. Mediation modeling was performed to determine the presence of a significant mediation (or indirect effect) of impulsivity in the relationship between ACE and health risk behaviors. Impulsivity was considered as a potential mediating variable when its inclusion into the model resulted in a partial or total diminution of the relationship between ACE as the independent variable and risky health behaviors was the dependent variable (Baron and Kenny, 1986). Mediation analyses were conducted using SPSS version 21 and the PROCESS macro developed by Andrew F. Hayes (Hayes and Rockwood, 2017). Results were also adjusted to age, gender, and common mental health disorders. Verification of the indirect effect was assessed using the Sobel test (Dudley et al., 2004).

To apply the mediation model, some criteria must be satisfied. First, the relationship between the independent variable (ACE) and the dependent variable (risky health behaviors) must be significant in separate models (pathway c); second, the variable of mediation (impulsivity) must be significantly associated with risky health behaviors (pathway b); and finally, the relationship between ACE and impulsivity must be significant (pathway a). Significant mediation occurs when pathway c is reduced significantly (partial mediation) or no longer significant (full mediation) by the inclusion of the mediator into the assessment of pathway c (pathway c ′).

2.3.2. Ethical considerations

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee at the University Hospital of Mahdia (Tunisia). Approval number: P01 M.P.C-2020

Authorizations were requested from headmasters of the participating schools. Before data collection, the use of test results for research was sufficiently explained to adolescents and their parents. They were free to refuse participation.

The questionnaire was self-administered anonymously and supervised by trained doctors. No teacher or administrative agents were present during data collection. Data entry was conducted by a separate trained member.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the study sample and ACE:

A total of 2520 schooled adolescents in 22 public and three private secondary schools were recruited. Of those, 1940 returned the questionnaires (response rate = 77%). The respondents’ mean age was 17 ± 1.5 and ranged from 14 to 23 years. Females represented 66.3% (n = 1278) of the study sample.

The distribution of characteristics of the study sample is presented by gender in Table 1.

Table 1.

General characteristics of adolescents by gender.

| Characteristics | Total (n = 1940) | Male (n = 662) | Female (n = 1278) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 17 ± 1.5 | 17.2 ± 1.4 | 17.3 ± 1.3 | 0.09 |

| Secondary education level | 0.01 | |||

| First level, n (%) | 559 (29.1) | 206 (31.6) | 353 (27.6) | |

| Second level, n (%) | 458 (23.6) | 169 (26) | 289 (22.6) | |

| Third level, n (%) | 449 (23.3) | 142 (21.8) | 307 (24) | |

| Fourth level, n (%) | 463 (24) | 134 (20.6) | 329 (25.7) | |

| Parental marital status | 0.98 | |||

| Married, n (%) | 1748 (90.6) | 590 (90.6) | 1158 (90.6) | |

| Single parent family, n (%) | 181 (9.4) | 61 (9.4) | 120 (9.4) | |

| Risky behaviors among family members | ||||

| Tobacco use, n (%) | 1262 (65.5) | 430 (66.1) | 832 (65.3) | 0.72 |

| Alcohol consumption, n (%) | 578 (30.2) | 206 (31.8) | 372 (29.3) | 0.25 |

| Cannabis use, n (%) | 177 (9.2) | 67 (10.4) | 110 (8.7) | 0.22 |

| Mental health issues | ||||

| Impulsivity, n (%) | 827 (43.5) | 232 (36.3) | 595 (47.2) | <0.0001 |

| Anxiety, n (%) | 807 (42.3) | 183 (28.5) | 624 (49.3) | <0.0001 |

| Depression, n (%) | 316 (16.6) | 95 (14.8) | 221 (17.5) | 0.14 |

Impulsivity and anxiety were more prevalent in females than in males (47.2% vs 36.3%, P < 0.0001; 49.3% vs 28.5%, P < 0.0001, respectively) (Table 1).

The overall majority of adolescents (97.5%) reported experiencing at least one ACE. Table 2 summarizes the distribution of intra-familial and social ACEs. Emotional neglect was the most common intra-familial ACE category (83.2%) followed by household dysfunction (80.5%). Physical abuse was more prevalent in males than in females (61% vs 54.1%, P = 0.004) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of reported ACEs and risky behaviors by gender.

| Categories of ACEs, n (%) | Total (n = 1940) | Male (n = 662) | Female (n = 1278) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure to intra-familial ACEs | 1786 (94.5) | 608 (95.8) | 1178 (93.9) | 0.2 |

| Emotional neglect | 1601 (83.2) | 538 (83.8) | 1057 (83.1) | 0.6 |

| Household dysfunction | 1534 (80.5) | 499 (78.5) | 1030 (81.7) | 0.09 |

| Physical abuse | 1082 (56.3) | 391 (61) | 687 (54.1) | 0.004 |

| Emotional abuse | 594 (30.8) | 197 (30.6) | 394 (31) | 0.8 |

| Physical neglect | 469 (24.4) | 173 (26.9) | 293 (23.1) | 0.06 |

| Sexual abuse | 257 (13.4) | 93 (14.5) | 162 (12.8) | 0.2 |

| Exposure to social ACEs | 1648 (86.9) | 589 (92.5) | 1059 (84) | <0.0001 |

| Community violence | 1417 (73.5) | 541 (84) | 870 (68.3) | <0.0001 |

| Peer violence/ Bullying | 1224 (64.1) | 437 (68.5) | 784 (62.1) | 0.006 |

| Collective violence | 359 (18.6) | 188 (29.2) | 169 (13.3) | <0.0001 |

| Health risk behaviors | ||||

| Internet addiction | 962 (50) | 353 (54.4) | 609 (47.7) | 0.006 |

| Substance use | 318 (16.6) | 261 (40.4) | 57 (4.5) | <0.0001 |

| Current cigarette smoking | 239 (12.4) | 207 (31.8) | 32 (2.5) | <0.0001 |

| E-cigarette smoking | 316 (16.4) | 212 (32.6) | 104 (8.2) | <0.0001 |

| Alcohol consumption | 190 (9.9) | 158 (24.4) | 32 (2.5) | <0.0001 |

| Cannabis consumption | 131 (6.8) | 115 (17.8) | 16 (1.3) | <0.0001 |

ACEs: Adverse Childhood Experiences

Witnessing community violence was the most reported social ACEs among schooled adolescents (73.5%). Cyber bullying was the most frequent type of peer violence, reported by 647 students (33.4%). According to gender, males had higher rates of exposure to social violence than females in all types of social ACEs (Table 2).

3.2. Prevalence of health risk behaviors

Table 3 shows the prevalence of internet addiction and substance use in the sample by gender. The most common risky behavior was internet addiction (50%) followed by substance use (16.6%). Males were more likely to report all types of problematic behaviors (Table 2).

Table 3.

Crude (OR) and adjusted odds ratio (ORa) (95% confidence intervals (IC)) for the association of the number of ACEs with risky behaviors among adolescents.

| Crude OR (IC) | Adjusted for age and gender (A) | Adjusted for A + Anxiety/Depression | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health risk behaviors | |||

| 0 ACE | 1 | ||

| 1–2 ACEs | 1.51 (0.75–3.04) | 1.51 (0.74–3.05) | 1.41 (0.61–2.80) |

| 3–4 ACEs | 3.21 (1.64–6.24)c | 3.02 (1.54–5.93)c | 2.66 (1.34–5.26)b |

| ≥5ACEs | 7.18 (3.70–13.91)c | 6.59 (3.83–12.81)c | 5.32 (2.70–10.41)c |

| Internet addiction | |||

| 0 ACE | 1 | ||

| 1–2 ACEs | 1.38(0.68–2.77) | 1.39 (0.69–2.80) | 1.31 (0.64–2.64) |

| 3–4 ACEs | 2.62(1.34–5.11)b | 2.57 (1.32–5.07)b | 2.22 (1.13–4.37)a |

| ≥5 ACEs | 4.94(2.55–9.56)c | 4.81 (2.48–9.31)c | 3.79 (1.93–7.43)c |

ACEs: Adverse Childhood Experiences

a: P < 0.05b: P < 0.01c: P < 0.001

3.3. Regression analysis of ACEs and risky health behaviors among adolescents

Table 3 indicates that the crude odds of having risky behaviors increased when the number of ACEs increased. When demographic characteristics (age and gender) and common mental disorders (anxiety and depression) were taken in account in the adjusted model, we found that the risk of having risky health behaviors increased in case of exposure to three or four ACEs (ORa = 2.6, CI = [1.34–5.26]) and in case of experiencing at least five ACEs (ORa = 5.3, CI = [2.70–10.40]) (Table 3).

3.4. Mediation analysis

All variables included in the mediation analysis were correlated (Table 4). Results of the mediation model are displayed in Table 5. After adjustment for covariates (age, gender, and common mental disorders) and accounting for the indirect effect of impulsivity, partial mediation effect was observed for the cumulative number of total ACEs as the exposure variable and risky behaviors as the outcome variable (P < 0.001; % mediated = 16.7%).

Table 4.

Zero-order relationships between ACEs, impulsivity and health risk behaviors among adolescents.

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of total ACEs | 0.29c | 0.33c |

| (1) Impulsivity | – | 0.22c |

| (2) Risky health behaviours | – | – |

| Number of intrafamilial ACEs | 0.27c | 0.23c |

| Number of extrafamilial ACEs | 0.22c | 0.36c |

ACEs: Adverse Childhood Experiences

c: P < 0.001

Table 5.

Adjusted mediation model of the relationship of ACE’s types on risky behaviors with impulsivity as a mediator among adolescents (n = 1823).

| Coefficients* | Sobel test | % Mediated┼ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediator╪ | a | b | c | c’ | SE | ||

| (Standard error) | P | ||||||

| Type of ACEs: | |||||||

| Total ACEs | 1.22 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.02 | <0.001 | 16.7 |

| Intra-familial ACEs | 1.09 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.02 | <0.001 | 27.8 |

| Social ACEs | 1.46 | 0.01 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 10.5 |

For total Adverse childhood Experiences (ACEs): Model adjusted to age, gender and common mental disorders (Anxiety and depression). For intra-familial ACEs: Model adjusted to age, gender and common mental disorders (Anxiety and depression) and social ACEs. For social ACEs: Model adjusted to age, gender and common mental disorders (Anxiety and depression) and intra-familial ACESs.

Mediated = c – c’/c

Mediator: Impulsivity

Intra-familial ACEs (P < 0.001; % mediation = 27.8%) demonstrating the most mediation by impulsivity followed by exposure to extra-familial ACEs (P < 0.001; % mediation = 10.5%) (Table 5).

There were interactions between ACE and impulsivity in terms of their impact on internet addiction (P < 0.001; % mediation = 37.5%) and substance use (P = 0.03; % mediation = 4.7%) (Table 6).

Table 6.

The indirect effect of ACEs on different types of risky behaviors through impulsivity among adolescents (n = 1823).

| Coefficients* | Sobel test | % Mediated┼ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediator╪ | a | b | c | c’ | SE (Standard error) | P | |

| Internet Addiction: | |||||||

| Total ACEs | 1.22 | 0.07 | 0.24 | 0.15 | 0.01 | <0.001 | 37.5 |

| Substance Use: | |||||||

| Total ACEs | 1.21 | 0.01 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 4.7 |

ACEs: Adverse Childhood Experiences

Model adjusted to age, gender and common mental disorders (Anxiety and depression).

Mediated = c – c’/c

Mediator: Impulsivity

4. Discussion

This survey was conducted to examine the role of impulsivity in mediating the effects of early life adversity on behavioural risk factors, namely addictive behaviors. The survey not only reveals that ACE predict problematic behaviors indirectly through impulsiveness (% mediated = 16.7%) but also highlights the major contribution of impulsivity in mediating the effect of exposure to intra-familial violence on risk for internet addiction. To date, only few studies in the world have assessed the relationship between exposure to early life adversities and harmful behaviors through impulsivity.

Males were more prevalent than females in the first education level in our sample. However, Females were more prevalent in the fourth level. This can be explained by the notable female predominance (54.6% in 2018) in schooling in Tunisia (Statistics of Education). According to statistics of the Tunisian Ministry of Education, 15.2% of boys left schools in 2018 (vs 9.9% of girls) (Statistics of Education).

The prevalence of ACE in the current sample is relatively high (97.5% of participants reported at least one ACE). Nearly half (46.5%) of adolescents who consulted the National Addiction Treatment Center in Singapore and 69% of youth in Slovakia have been exposed to at least one ACE (Lackova Rebicova et al., 2019, Gomez et al., 2018). These recent studies showed that negative effects on health caused by ACE may already start in adolescence (Lackova Rebicova et al., 2019). However, we could not find any North African or Tunisian studies tackling ACE among adolescents. Our results are in agreement with those of few eastern studies also based on the ACE-IQ and conducted in Arabia Saudi (Almuneef et al., 2016) and Tunisia (El Mhamdi et al., 2017) among university adults which reported approximately similar rates (82%, 74.8% respectively).

The most common intra-familial violence category in our study was emotional neglect (83.2%), followed by household dysfunction (80.5%). These rates varied from those reported in Western studies. In the 2016 Minnesota school-based survey (N = 126 868), the most common abuse among youth was household dysfunction with lower rates ranging from 16.5% to 9.8% (Duke, 2018). A study including 2531 adults in Germany showed that 43.7% reported at least one intra-familial ACE and emotional neglect was reported in only 13.4% of cases (Witt et al., 2019). An alarming figure found when analysing our data is that 257 students (13.4%) reported being sexually abused with no gender differences. The finding prevalence is lower than the one reported by a national survey conducted among adults in Saudi Arabia (20.8%) and in the United States (28% for women and 16% for men) (Almuneef, 2019, Felitti et al., 1998). This huge difference across studies might be attributable to differences in measuring tools and cultures. These findings should alarm decision makers to investigate thoroughly child abuse, its characteristics and try to prevent it. Regarding extra-familial adversities, exposure to community violence was the most reported social ACE among adolescents (73.5%). This could be explained by the particular context related to the Tunisian revolution that released intensive street demonstrations and unrest since January 2011. Thus, it is important to highlight that the current sample of adolescents was aged between 5 and 14 years during the revolution period.

Based on our results, the most prevalent risk-taking behavior was internet addiction (50%). Males were more likely to be problematic users than females (54% vs 47.7%; P = 0.006). Our results are consistent with a recent Tunisian study (Ben Thabet et al., 2019) revealing 43.9% of internet addiction among adolescents with an increased risk for males. This reflects the high risk of cyber-addiction among Tunisian adolescent compared to others in Portugal and China (19% in 2017, 11.3% in 2018 respectively) (Ben Thabet et al., 2019). This high rate could be related to the liberalization and increased access to the internet access after the Tunisian revolution. Indeed, the internet and social platforms were instrumental in enhancing networks among the youth and facilitated the revolution, and has been since an instrument for promoting civic engagement in Tunisian social and political life.

The second addictive behavior we focused on in our sample was substance use which consisted of tobacco use (12.4%; 95% CI = [11–14%]), alcohol consumption (9.9%; 95% CI = [8.7–11.3%]) and cannabis use (6.8%; 95% CI = [5.7–8%]). Likewise, it was found in a Tunisian study that the most prevalent drug on initiation of substance addiction was cannabis (38.8%) and alcohol (32.9%) (Sellami et al., 2016). Males self-reported higher substance use. Tobacco consumption data of school-adolescents in Sfax (Tunisia) (Ayed et al., 2020) revealed nearly the same rate (13.9%). According to published reports between 2007 and 2018 in Saudi Arabia, the prevalence of smoking among youth ranged from 9.72% to 37% (Alasqah et al., 2019). Multiple factors may explain this rapidly growing epidemic of substance use in North African and Middle East countries yet to be scientifically identified, although there are indication that availability of drugs with an affordable price has increased (Elamouri et al., 2018).

We found out that impulsivity (43.5%) was mostly prevalent among students. Lower rate (29.6%) was found in a 2016-study (Charfi et al., 2019) among Tunisian adolescents, but the prevalence remains high. Females were more likely to be impulsive than males in our sample. Gender and culture analyses found no clear evidence of higher or lower impulsivity rates in Arabic samples compared to Western samples (Ziada et al., 2020). To have more robust and valid results, the inclusion of large representative samples from Arab-Muslim countries is required. It is believed that high levels of impulsivity are often associated with childhood maltreatment. This relationship was investigated in the United States (Shin et al., 2018) as well as Pakistan (Haaris Sheikh et al., 1978), showing that young adults exposed to multiple ACE reported increased levels of impulsive self-control. On the other hand, impulsivity is a vulnerability marker for addictive behaviors among youth such as substance use (Charfi et al., 2019) as well as internet addiction (Li et al., 2019).

Given that ACE appears to be related to higher levels of impulsivity, and impulsivity is a risk factor for many harmful behaviors, it follows that impulsivity could be a major mediator linking childhood adversities and problematic practices during adolescence (Wardell et al., 2016). However, much less attention has been paid to this specific meditational pathway among youth worldwide. The present study demonstrated significant mediation part of impulsiveness with exposure to intra-familial violence (% mediation = 27.8%) higher than extra-familial violence (% mediation = 10.5%). Due to the lack of literature reviews which only focusing on impulsivity as a mediator between intra-familial adversities and substance use, it may be hard to compare our results. Considering each type of risky behaviors, only few studies have examined the mediation role of impulsive behaviors on internet addiction among youth. It is evident that there are a variety of possible risk factors contributing to understand the etiological pathway of cyberaddiction (Lam, 2014). The Problem Behavior Theory is one recent possible explanation that suggests the presence of three systems in the conceptual structure of risky behaviors, especially among adolescents, namely the personality, environment and the behavioural systems (Lam, 2014). Thus, any involvement in problematic behavior such as internet addiction is determined by the balance among risk and protective factors in the three systems. A potential explanation suggested in a 2020-study conducted in the United States, is that people exposed to ACE may develop insecure attachment as well as impulsive behavior. Consequently, those individuals with higher impulsivity may have difficulties with face-to face interactions and prefer to interact in media settings (Wilke et al., 2020). The present survey extends these prior studies by showing a great partial mediation (% mediation = 37.5%) of the effect of ACE on cyberaddiction through impulsiveness. This detrimental association should be subjected to special concern by the Ministry of Education in Tunisia. More research is needed to further clarify this link.

Our study also provides initial evidence that childhood maltreatment has an indirect influence on substance use via impulsivity (% mediation = 4.7%). Despite differences of methodologies used, our results are consistent with previous international literature in Canada, United States and Korea. Current analyses of various facets of impulsivity as a mediator in simultaneous mediation models (Wardell et al., 2016, Shin et al., 2015) showed that intra-familial childhood maltreatment was a predictor of both alcohol problems and cannabis use through negative and positive urgency facets of impulsivity. Specifically, it was found that emotional abuse is indirectly related to alcohol use via urgency (Ramakrishnan et al., 2019, Oshri et al., 2018). This can be attributable to the fact that emotionally abused children, who later develop impulsive behaviors, are engaged in risky practices like substance use in order to avoid negative emotionality (Kim et al., 2018).

4.1. Study limitations and strengths

First, the cross-sectional nature of the data provided no insight into the temporal association among adverse experiences, impulsivity, and risky behaviors. Future studies should examine these variables in a longitudinal prospective design to elucidate the direction of this association. Second, it is known that self-reported ACE are subject to recall and social desirability bias. However, our population sample is nearly still in the range age of childhood adversities which leads to relatively less bias. Third, our target population consisted only of schooled youth who are generally at lower risk of harmful practices compared to out-of-school adolescents. Several recent research examined the relationship between adverse experiences and juvenile delinquency (Leban and Gibson, 2020, Pechorro et al., 2021, Jones and Pierce, 2020), which is an important fact to assess, considering the generality of early life adversity. Unfortunately, we were unable to measure delinquency because it was easier to screen students in schools since the out of school ones are generally not attainable. Furthermore, the present study was conducted in only one Tunisian governorate which limits the representativeness of our results. However, it is important to note that this survey is part of a national project and will be repeated among schooled youth in different regions in Tunisia. Finally, knowing that there are several impulsivity aspects, we only focused on total impulsivity score in mediation models. It is highly recommended that further research by child and adolescents psychiatrists extend on the current findings to explore the role of various impulsivity facets on the relationship between ACE and several risky practices amongst adolescents.

4.2. Conclusion

These dangerous impacts of ACE as well as impulsivity on youth well-being have both public health and societal implications. In view of this high prevalence of ACE and the lack of national program targeting adolescent’s mental health wellbeing, further work appears to be timely to identify appropriate ACE prevention strategies in Tunisia.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

Authors would like to thank Dr. Maha Almuneef for his valuable help. The authors wish also to thank the following individuals for their help in data collection: Houcem Elomma Mrabet, Nejla Rezg, Faouzia Chebbi, Sarra Nouira, Ines Daldoul, Fethi Aroui, Asma Sayadi. We take this opportunity to extend our gratitude to the team of the Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine at the University Hospital Taher Sfar Mahdia.

References

- Abdelraheem M., McAloon J., Shand F. Mediating and moderating variables in the prediction of self-harm in young people: a systematic review of prospective longitudinal studies. J. Affect Disord. 2019;246:14–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) and adolescent health [Internet]. [cited 29 July 2020]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/adolescent/second-decade/section/section_5/level5_3.php.

- Adverse childhood experiences survey among university students in Turkey (2014) [Internet]. [cited 29 July 2020]. Available from: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/violence-and-injuries/publications/2015/adverse-childhood-experiences-survey-among-university-students-in-turkey-2014.

- Alasqah I., Mahmud I., East L., Usher K. A systematic review of the prevalence and risk factors of smoking among Saudi adolescents. Saudi Med. J. 2019;40(9):867–878. doi: 10.15537/smj.2019.9.24477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almuneef M. Long term consequences of child sexual abuse in Saudi Arabia: a report from national study. Child Abuse Negl. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almuneef M., Hollinshead D., Saleheen H., AlMadani S., Derkash B., AlBuhairan F. Adverse childhood experiences and association with health, mental health, and risky behavior in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Child Abuse Negl. 2016;60:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almuneef M., Qayad M., Aleissa M., Albuhairan F. Adverse childhood experiences, chronic diseases, and risky health behaviors in Saudi Arabian adults: a pilot study. Child Abuse Negl. 2014;38(11):1787–1793. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shawi A.F., Lafta R.K. Effect of adverse childhood experiences on physical health in adulthood: results of a study conducted in Baghdad city. J. Family Community Med. 2015;22(2):78–84. doi: 10.4103/2230-8229.155374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayed HB, Yaich S, Hmida MB, Jemaa MB, Trigui M, Karray R, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with smoking among Tunisian secondary school-adolescents. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health [Internet]. 2020 [cited 28 July 2020];1(ahead-of-print). Available from: https://www.degruyter.com/view/journals/ijamh/ahead-of-print/article-10.1515-ijamh-2019-0088/article-10.1515-ijamh-2019-0088.xml. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Baron R.M., Kenny D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Thabet J., Ellouze A.S., Ghorbel N., Maalej M., Yaich S., Omri S. Factors associated with Internet addiction among Tunisian adolescents. Encephale. 2019;45(6):474–481. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2019.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumley L.D., Jaffee S.R., Brumley B.P. Pathways from childhood adversity to problem behaviors in young adulthood: the mediating role of adolescents’ future expectations. J. Youth Adolesc. 2017;46(1):1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0597-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charfi N., Smaoui N., Turki M., Maâlej Bouali M., Omri S., Ben Thabet J. Enquête sur la consommation d’alcool et sa relation avec la recherche de sensations et l’impulsivité chez l’adolescent de la région de Sfax, Tunisie. Rev. d’Épidémiologie de Santé Publ. 2019;67(1):13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.respe.2018.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley W.N., Benuzillo J.G., Carrico M.S. SPSS and SAS programming for the testing of mediation models. Nurs Res. 2004;53(1):59–62. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200401000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke N.N. Adolescent adversity and concurrent tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use. Am. J. Health Behav. 2018;42(5):85–99. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.42.5.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fifth Edition. American Psychiatric Association 2013 https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/book/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596. [cited 9 August 2020]. Available from:.

- Edwards V.J., Holden G.W., Felitti V.J., Anda R.F. Relationship between multiple forms of childhood maltreatment and adult mental health in community respondents: results from the adverse childhood experiences study. AJP. 2003;160(8):1453–1460. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Mhamdi S., Lemieux A., Bouanene I., Ben Salah A., Nakajima M., Ben Salem K. Gender differences in adverse childhood experiences, collective violence, and the risk for addictive behaviors among university students in Tunisia. Prev. Med. 2017;99:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elamouri F.M., Musumari P.M., Techasrivichien T., Farjallah A., Elfandi S., Alsharif O.F. « Now drugs in Libya are much cheaper than food »: a qualitative study on substance use among young Libyans in post-revolution Tripoli Libya. Int. J. Drug Policy. 2018;53:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellouze F., Ghaffari O., Zouari O., Zouari B., M’rad MF Validation of the dialectal Arabic version of Barratt’s impulsivity scale, the BIS-11. Encephale. 2013;39(1):13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2012.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feki I., Moalla M., Baati I., Trigui D., Sellami R., Masmoudi J. Impulsivity in bipolar disorders in a Tunisian sample. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2016;22:77–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2016.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti V.J., Anda R.F., Nordenberg D., Williamson D.F., Spitz A.M., Edwards V. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez B., Peh C.X., Cheok C., Guo S. J. Subst. Use. 2018;23(1):86–91. [Google Scholar]

- Haaris Sheikh M., Naveed S., Waqas A., Tahir Jaura I. Association of adverse childhood experiences with functional identity and impulsivity among adults: a cross-sectional study. F1000Res. 1978:6. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.13007.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawi N.S. Arabic validation of the Internet addiction test. Cyberpsychol. Behav.. Soc. Netw. 2013;16(3):200–204. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A.F., Rockwood N.J. Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behav Res Ther. 2017;98:39–57. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes K., Bellis M.A., Hardcastle K.A., Sethi D., Butchart A., Mikton C. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(8):e356–e366. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones M.S., Pierce H. Early exposure to adverse childhood experiences and youth delinquent behavior in fragile families. Youth Society. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Kazdouh H.E., El-Ammari A., Bouftini S., Fakir S.E., Achhab Y.E. Potential risk and protective factors of substance use among school adolescents in Morocco: a cross-sectional study. J. Subst. Use. 2019;24(2):176–183. [Google Scholar]

- Khemakhem K., Boudabous J., Cherif L., Ayadi H., Walha A., Moalla Y. Impulsivity in adolescents with major depressive disorder: a comparative tunisian study. Asian J. Psychiatry. 2017;28:183–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.T., Hwang S.S., Kim H.W., Hwang E.H., Cho J., Kang J.I. Multidimensional impulsivity as a mediator of early life stress and alcohol dependence. Sci. Rep. 2018;8(1):4104. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22474-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackova Rebicova M., Dankulincova Veselska Z., Husarova D., Madarasova Geckova A., van Dijk J.P., Reijneveld S.A. The number of adverse childhood experiences is associated with emotional and behavioral problems among adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019;16(13) doi: 10.3390/ijerph16132446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam L.T. Risk factors of Internet addiction and the health effect of internet addiction on adolescents: a systematic review of longitudinal and prospective studies. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16(11):508. doi: 10.1007/s11920-014-0508-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leban L., Gibson C.L. The role of gender in the relationship between adverse childhood experiences and delinquency and substance use in adolescence. J. Crim. Justice. 2020;66 [Google Scholar]

- Q. Li W. Dai Y. Zhong L. Wang B. Dai X. Liu The Mediating Role of Coping Styles on Impulsivity, Behavioral Inhibition/Approach System, and Internet Addiction in Adolescents From a Gender Perspective Front. Psychol. [Internet]. 2019 https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02402/full. [cited 28 July 2020];10. Available from:. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Li W, Zhang X, Chu M, Li G. The Impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences on Mobile Phone Addiction in Chinese College Students: A Serial Multiple Mediator Model. Front Psychol [Internet]. 13 mai 2020 [cited 2 August 2020];Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7237755/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- V.L. Morris L.G. Huffman K.R. Naish K. Holshausen A. Oshri M. McKinnon et al. Impulsivity as a mediating factor in the association between posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and substance use Psychological Trauma: Theory, Res. Practice Policy [Internet]. 2020 http://doi.apa.org/getdoi.cfm?doi=10.1037/tra0000588. [cited 28 July 2020]; Available from:. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Oshri A., Kogan S.M., Kwon J.A., Wickrama K., a. S, Vanderbroek L, Palmer AA Impulsivity as a mechanism linking child abuse and neglect with substance use in adolescence and adulthood. Dev Psychopathol. 2018;30(2):417–435. doi: 10.1017/S0954579417000943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton J.H., Stanford M.S., Barratt E.S. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J. Clin. Psychol. 1995;51(6):768–774. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6<768::aid-jclp2270510607>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pechorro P., DeLisi M., Abrunhosa Gonçalves R., Pedro Oliveira J. The role of low self-control as a mediator between trauma and antisociality/criminality in youth. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18(2) doi: 10.3390/ijerph18020567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan N., McPhee M., Sosnowski A., Rajasingaam V., Erb S. Positive urgency partially mediates the relationship between childhood adversity and problems associated with substance use in an undergraduate population. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2019;10 doi: 10.1016/j.abrep.2019.100230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles A., Gjelsvik A., Hirway P., Vivier P.M., High P. Adverse childhood experiences and protective factors with school engagement. Pediatrics. 2019;144(2) doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellami R., Feki I., Zahaf A., Masmoudi J. The profile of drug users in Tunisia: implications for prevention. Tunis Med. 2016;94(8–9):531–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin S.H., Lee S., Jeon S.-M., Wills T.A. Childhood emotional abuse, negative emotion-driven impulsivity, and alcohol use in young adulthood. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;50:94–103. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin S.H., McDonald S.E., Conley D. Profiles of adverse childhood experiences and impulsivity. Child Abuse Negl. 2018;85:118–126. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore H, 2015.Shore* H, Shunu A. Risky sexual behavior and associated factors among youth in Haramaya Secondary and Preparatory School, East Ethiopia, 2015. JPHE. 2017;9(4):84‑91.

- Statistics of Education – Ministry of Education Tunisia [Internet]. [cited 19 August 2020]. Available from: http://www.education.gov.tn/?p=688&lang=en.

- Terkawi A.S., Tsang S., AlKahtani G.J., Al-Mousa S.H., Al Musaed S., AlZoraigi U.S. development and validation of arabic version of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. Saudi J Anaesth. 2017;11(Suppl 1):S11–S18. doi: 10.4103/sja.SJA_43_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Throuvala M.A., Griffiths M.D., Rennoldson M., Kuss D.J. School-based prevention for adolescent internet addiction: prevention is the key. A systematic literature review. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2019;17(6):507–525. doi: 10.2174/1570159X16666180813153806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardell J.D., Strang N.M., Hendershot C.S. Negative urgency mediates the relationship between childhood maltreatment and problems with alcohol and cannabis in late adolescence. Addict. Behav. 2016;56:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO | Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ) [Internet]. WHO. [cited 21 August 2020]. Available from: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/activities/adverse_childhood_experiences/en/.

- Wilke N., Howard A.H., Morgan M., Hardin M. Adverse childhood experiences and problematic media use: the roles of attachment and impulsivity. Vuln. Child. Youth Stud. 2020;15(4):344–355. [Google Scholar]

- Witt A., Sachser C., Plener P.L., Brähler E., Fegert J.M. The Prevalence and Consequences of Adverse Childhood Experiences in the German Population. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2019;116(38):635–642. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2019.0635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziada K.E., Becker D., Bakhiet S.F., Dutton E., Essa Y.A.S. Impulsivity among young adults: Differences between and within Western and Arabian populations in the BIS-11. Curr Psychol. 2020;39(2):464–473. [Google Scholar]