Abstract

Background:

The public’s view of palliative care often involves its potential to improve of quality-of-life as well as its use as a last resource prior to death.

Objective:

To obtain an idea of the image of palliative care held by the public in the German-speaking part of Switzerland, the authors sought to understand (1) the perceptions of palliative care and the (2) elements important when thinking about their own end of life.

Methods and Sample:

A qualitative design with an inductive reasoning approach based on Mayring (2014) was chosen. Visitors at an exhibition about palliative care in six locations provided hand-written answers on provided cards to two statements: (1) if I hear the term ‘Palliative Care’ I think of … and (2) when thinking about my own end of life, the following is important to me …

Results:

Answers of 199 visitors (mean age 52, mostly in a good/very good health status) were analysed. In response to hearing the term palliative care, six areas were categorized: (1) the main focus; (2) ways of providing palliative care; (3) the best timing; (4) places where palliative care is provided; (5) who is seen as provider and (6) outcomes of palliative care. Five categories to the statement about their own end-of-life were identified: (1) the ability to look back on a fulfilled life and being satisfied; (2) maintaining trusting relationships until the end; (3) organizing affairs and having everything settled; (4) having their family being cared for and (5) relief of suffering with the support of knowledgeable people.

Conclusion:

Palliative care was mostly associated with positive terms acknowledging an interprofessional approach. Maintaining one’s dignity as well as dying without suffering pointed at the persisting stigma that palliative care is mainly limited to end-of-life care. The results may help healthcare professionals to better understand how the public view palliative care.

Keywords: end-of-life, palliative care, public health, public perception, qualitative research

Introduction

The definition of palliative care by the World Health Organization embraces a holistic approach including the physical, psychological, social and spiritual health and well-being of patients with a life-threatening illness. 1 The public’s view and understanding of palliative care often involves a focus on pain relief and improvement of quality-of-life 2 as well as issues of dying and death.3,4 The public image of and knowledge about palliative care seem to depend strongly on personal experiences or on the attention that today’s media give to palliative care. 5

Whether initiated early or late in the disease trajectory of a life-limiting disease, palliative care challenges individuals with the prospect of their own death or that of a loved one. Patients and their families6,7 and the public,3,8,9 frequently misperceive that palliative care is mainly about care in the last days of life 10 and often associate it with cancer.3,11,12 A recent scoping review found that the public still equates palliative care to hospice or end-of-life care and that people often connect end-of-life care with ‘giving up’. 13 As a result, palliative care services are often offered and integrated only very late in the disease trajectory, and thus, it continues to be seen as the last resource prior to death. 7

Among healthcare providers, there also seems to be a heterogenous understanding of what palliative care entails14,15 and what palliative care services offer not only to those imminently dying. Some providers have a lack of or unclear knowledge of how palliative care can contribute to the diagnosis-driven approach.14,15 Also, it is known that some physicians refrain from referring patients to palliative care services because they associate palliative care with care for the imminently dying,16–18 are unaware of disease-related triggers to refer patients to palliative care services 15 or lack strategies to speak with patients about palliative care. 14 Contrary to what patients and their families might need, late referrals to palliative care may lead to suboptimal care and access to less than ideal palliative care services.

The various misconceptions and stigmas around the term have led some authors debate or argue for a name change to eliminate the word ‘palliative’ and replacing it with ‘supportive’.17,19–22 For example, two studies explored the effect of a name change from ‘Palliative Care’ to ‘Supportive Care’, and found that referral rates increased because supportive care is not connected to distress and the idea of taking hope away from patients.17,23 In a recent survey however, palliative care specialists expressed concerns about the term ‘palliative care’ but anticipated that a change of the term would eventually not solve the stigma. 22

For people with a life-limiting disease, it is important to be autonomous as long as possible including being engaged in everyday life and maintaining social relationships and also having the ability to prepare for dying and death while living life as normal as possible. This includes also the wish of not being left alone at the time of death24–28 which should be supported by the palliative care approach. Unless correct information about what palliative care entails is provided to the public, the current misperception may not change.

To understand the views of palliative care held by the Swiss public, in particular of visitors at a travelling exhibition about palliative care, the authors sought to understand (1) the perceptions about palliative care and (2) elements that the public finds important when thinking about their own end of life.

Methods

In this study, visitors at an exhibition about palliative care were asked about their perspectives on palliative care and end of life. The two statements that they were asked to share their thoughts on were:

If I hear the term ‘Palliative Care’ I think of . . .

When thinking about my end of life, the following is important to me . . .

Design and setting

A qualitative research approach was chosen to explore visitors’ personal perceptions of palliative care and to analyse responses. Answer cards to the aforementioned statements were available at the exhibition site in which visitors were asked to write words, phrases or sentences or they also could use other forms of answers such as drawings.

This study was linked to an exhibition organized in 2016 by the Bernese section of the Swiss Association for Palliative Care (palliative bern). The Canton of Bern is culturally mainly part of German-speaking Switzerland with 86% of people speaking German and 11% speaking French. The exhibition rotated throughout various locations/communities over a period of 6 weeks (approx. one week per site): city of Bern, Interlaken, Thun, Biel, Burgdorf, Langnau, and Langenthal.

The exhibition was developed to enhance the knowledge of the public and sensitize them to what palliative care involves. The exhibition intended to provide answers to questions about palliative care by storytelling of individuals who were directly confronted with the finiteness of life. Answers were displayed to questions such as

How has death and dying changed in modern times?

How can palliative care support the final phase of life?

What does a palliative care team offer?

How can individuals deal with powerlessness and grief?

What does hope mean?

These stories and reflections were either exhibited on panels or could be heard as an audio file. They were intended to encourage visitors to engage in discussions about these topics within their own social environment or with professionals of the local palliative care teams who were present during exhibition hours.

Participants and data collection

Visitors at the exhibition had the opportunity to obtain a response card available in the exhibition area containing demographic questions and the two statements. Visitors were encouraged to voluntarily complete the card during their visit at their convenience or take the card home and send it back to the researchers via mail. Visitors were asked to answer the cards only once. Each exhibition site collected data until the end of rotation and sent it to the study centre. All cards were marked with a discrete number for each study site for analysis purposes.

A sample size was not pre-defined, since the study relied on the number of visitors who attended each exhibition site. Demographic data included: (1) participants’ age, (2) gender, (3) prior contact with palliative care services, (4) living situation, (5) general health condition, and (6) being in possession of an advance directive or not. In addition to German and French, the authors wanted to include visitors with another primary language. Therefore, the response cards were made available in Italian, English, Spanish, and Turkish.

During the travelling exhibition (6 weeks between October to December 2016), palliative care professionals and volunteers offered to serve as guardians and guides at each exhibition site. They all were informed by the study group about the purpose and process of the study including instructions on how to motivate visitors to participate. Additional information was given regarding psychological support that was available in case any visitors felt distressed by the exhibition or by the study statements.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used for demographic data. Qualitative content analysis as proposed by Mayring 29 was used with an inductive reasoning approach to analyse the answers to the open-ended statements. Answers that were not directly related to these statements were excluded from analysis. If answers were not in German, they were translated into German by native speakers within the research team. Data were analysed for all visitors who completed a card. Replies of visitors under the age of 18 were excluded from analysis because the ethical approval request did not include minors.

Two researchers (S.C.Z., a senior psychologist researcher and M.C.F., an Advanced Practice Nurse and a doctoral candidate) analysed the qualitative data. The two authors coded and analysed independently the answers to later compare the coding approach and make sure that the coding was intersubjectively understood. After reading and re-reading the responses and defining that written single words and whole phrases would be analysed, the following steps were taken: (1) paraphrasing of text passages and assigning codes to words or phrases with a similar meaning based on rules predetermined between the researchers; if words or phrases were applicable to more than one code, they were allocated to these different codes, (2) codes were reduced and categories as well as sub-categories were defined, (3) the categories and sub-categories were further developed and comprehensively refined until consensus was reached. Through multiple discussions, the two authors adapted and consolidated the final categories and sub-categories. MAXQDA (Version 18.2.0), a software for qualitative data analysis, supported the coding of the data.

Ethical considerations

The local ethics committee considered the application and decided that ethical approval was not necessary (KEK-BE: 2016-01624). To grant anonymity, a sealed box for depositing the answer cards was provided at all exhibition sites by the study team.

Findings

Participating visitors

Of the 2220 visitors to the exhibition, 230 visitors provided written answers (response rate 10.4%). Of these, answers of 31 participating visitors were excluded because they were under 18 years of age. Thus, 199 visitors’ responses were analysed (8.96%) (Table 1). The average age of the visitors was 52 years old. The majority of the participating visitors were female (82.4%).

Table 1.

Demographics of the participating visitors.

| N = 199 | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Men | 31 | 15.6 |

| Women | 164 | 82.4 | |

| Unknown | 4 | 2.0 | |

| Age (years) | Mean | 52 | |

| Median | 53 | ||

| Range | 18-92 | ||

| Living area | Urban | 74 | 37.2 |

| Rural | 125 | 62.8 | |

| Previous contact to palliative care service | Yes | 120 | 60.3 |

| Health status | Very good – good | 192 | 96.5 |

| Not so good | 4 | 2.0 | |

| Unknown | 3 | 1.5 | |

| In possession of an advance directive | Yes | 65 | 32.7 |

| No | 116 | 58.3 | |

| Unknown | 18 | 9.0 | |

| Housing situation | Living with someone | 140 | 70.4 |

| Living alone | 57 | 18.6 | |

| Unknown | 2 | 1.0 | |

| Language | German | 193 | 97.0 |

| French | 5 | 2.5 | |

| Spanish | 1 | 0.5 |

Findings for statement 1: ‘If I hear the term “Palliative Care” I think of …’

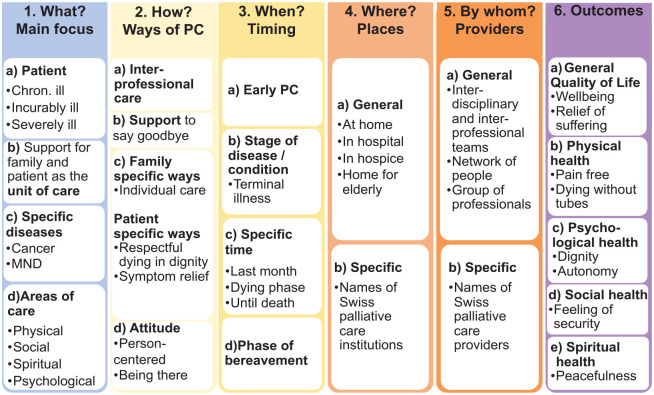

In response to this statement, visitors provided a variety of associations with the term palliative care. These were categorized under six main areas (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Associations with the term ‘palliative care’.

What? The main focus of palliative care was mentioned by about a fifth of the visitors.

How? Ways of providing palliative care were described by almost all visitors.

When? The best timing for palliative care was found in about half of the visitors’ responses.

Where? Places where palliative care is provided was only brought up by a few visitors.

By whom? Who is seen as provider of palliative care appeared only in a small portion of the responses.

Outcomes of palliative care were identified in about half of the responses.

Category 1: What? The main focus of palliative care (Figure 1).

Under this category, associations with the term ‘palliative care’ concerned (1) patient groups/populations by stage of disease, (2) the family and the patient as the unit of care, (3) specific disease entities, and (4) areas of care.

Patient groups requiring palliative care were found in about a quarter of visitors’ responses who specifically mentioned that palliative care was for those who were chronically, incurably or severely ill. For example, they described palliative care as being for ‘people who have a serious diagnosis and still want to have a good quality of life’ (Visitor (V) 21) or for ‘Incurable sick people’ (V76), or for ‘dying people who need specific attention (pain relief, care, . . .)’ (V40).

Some of these visitors also described palliative care as including support for the family, seeing them as another important target group of care. Visitor 61 stated that with palliative care ‘family members are included in the care’ (V61).

Patients with specific diseases such as ‘people with cancer’ (V143) or moto-neuron diseases (MND) such as ‘Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis’ (V 213) were mentioned only by a few visitors as potential target groups for palliative care.

Among the areas of care, several visitors conceptualized palliative care as having a holistic approach covering the physical, psychological, social and spiritual dimensions of human beings. Visitor 126 stated for example: ‘psychological and physical care’, or as another visitor (V145) phrased it: ‘. . . care on all levels: physical, psychological, social and spiritual’.

Category 2: How? Ways of providing palliative care (Figure 1).

Almost all visitors connected the term ‘palliative care’ with a variety of actions that are specific to the provision of palliative care: (1) interprofessional care, (2) general support, (3) individual (family/patient) ways of care delivery, and (4) stance/attitude.

Interprofessional care was mentioned by many visitors either via the term itself or by naming professions potentially involved in palliative care such as: ‘. . . home care nurses, the doctor, the spiritual carer, . . .’ (V149). Some visitors realized that different professions offer palliative care by working in close collaboration to meet all needs of the patient and family and stated: ‘. . . interconnected (palliative care) providers’ (V101).

General support was seen by a few visitors as the different aspects they could get support from palliative care teams, but especially in terms of saying goodbye. One visitor (V77) described this as: ‘. . .to die in peace with oneself and others and people who help me with that’.

Ways of care delivery for patients and families were described. That is, some visitors stated that care should be according to individual needs ‘individual care’ (V145) or ‘Family = patient and family taken serious’ (V68). In the case of patients, the description of delivery of care was in terms of symptom control such as ‘Symptom relief, maintaining quality of life’ (V97).

The attitude of palliative care staff was described by most as providing ‘empathic care’ (V169) or ‘professional care at the end of life’ (V31).

Category 3: When? The timing for palliative care (Figure 1).

The timing for palliative care ranged from early in the disease trajectory to a specific stage of a disease extending to the bereavement phase. Visitors’ responses were thus categorized under: (1) early stage of a disease, (2) at specific times in the disease trajectory, (3) at a certain stage of the disease, or (4) at the bereavement stage.

An early stage of a disease was mentioned only by a minority of visitors under statements such as: ‘. . . it would be nice to receive palliative care from the beginning of a serious diagnosis’ (V79).

Specific times in the disease trajectory were covered by some visitors. For example, one visitor stated that palliative care should commence ‘. . . as soon as a chronic disease is diagnosed’ (V74).

For a specific stage of the disease, comments of many visitors included: ‘last months before death’ (V127) or ‘being terminally ill’ (V216).

Palliative care was described by some visitors to be ideal for the bereavement phase. For example, visitor 197 described palliative care as having ‘. . . to do a lot during bereavement’ (V187).

Category 4: Where? Places where palliative care is provided (Figure 1).

Some visitors connected the term ‘palliative care’ to (1) general or (2) specific locations where palliative care is provided.

Reponses of those visitors who mentioned general places identified different settings where palliative care is practiced such as ‘. . . care in the hospital, nursing home or at home’ (V126) or ‘in a harmonic environment’ (V164).

Specific institutions within the Canton Berne were also stated by several visitors who included places such as ‘Diaconis’ in Bern (V183), a specialized palliative care unit in a private Hospital or ‘Centre Schönberg’ (V40), a centre specifically for people with dementia, both within the city of Bern.

Category 5: By whom? Who is seen as a provider of palliative care (Figure 1).

Only a few answers connected the term ‘palliative care’ with specific providers who deliver palliative care. These could be categorized as providers of palliative care services (1) in general or (2) in specific.

Most responses included general terms such as ‘professional care by community nurses, physicians, pastoral carers, . . .’ (V149) or more in general such as ‘. . . knowing that there are people (professionals, because I live alone) who are not afraid of caring for me’ (V216).

Only certain visitors mentioned specific names of palliative care experts such as: ‘Prof. (name anonymized). . .’ (V80) a Professor for Palliative Care in Switzerland.

Category 6: Outcomes? If palliative care is provided, what outcomes do people expect (Figure 1).

More than half of the visitors connected palliative care with specific outcomes that could be categorized under: (1) general quality of life, (2) physical health, (3) psychological health, (4) social health, or (5) spiritual health.

The general quality of life could be seen in responses describing palliative care as aiding to have ‘an end of life as pleasant as possible if that is possible’ (V168).

In terms of physical health and well-being, visitors referred to dying: ‘. . . if possible pain free’ (V132).

Visitors described the role of palliative care as also helping to maintain psychological health and well-being by providing support to ‘dying with dignity and without anxiety’ (V205) or supporting a ‘worthy and dignified life until the last breath’ (V206).

Social health and well-being outcomes were identified in statements referring to palliative care as ‘. . . to be taken seriously’ (V158).

Spiritual health and well-being were indicated in statements in which patients qualified palliative care support as facilitating ‘. . . peaceful dying’ (V213).

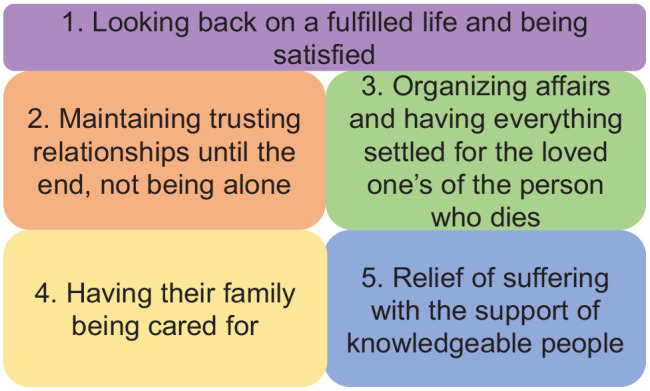

Findings for statement 2: ‘When thinking about my end of life, the following is important to me …’

The researchers identified five main categories from visitors’ responses to the second statement about what visitors found important when considering their own mortality. These five categories are listed below and appear in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Reflections on own end-of-life.

The ability to look back on a fulfilled life and being satisfied appeared in only a few visitors’ responses.

About a third of the visitors mentioned that maintaining trusting relationships until the end – not being alone was important to them.

Organizing affairs and having everything settled for loved ones of the person who dies appeared to be important to about a third of the visitors.

Having their family being cared for was only mentioned by some visitors.

Relief of suffering with the support of knowledgeable people was mentioned by the majority of the visitors.

Category 1: Looking back on a fulfilled life and being satisfied.

An important category for a few visitors when reflecting on their own end of life was the ability to look back onto a fulfilled life of happiness and being satisfied. Upon reflection, one visitor explained ‘… that I had a good and happy life’ (V25), while another stated ‘… that at the end my life is in balance’ (V40). When reflecting on their own life, visitors believed it was important to have had balance and meaning in their life as well as being pleased with what they had achieved in their life. As one visitor phrased it: Being in peace with my closest ‘[family members] and my environment’ (V210). Another visitor stated to ‘… be at peace with myself and my surrounding, family’ as a wish (V164).

Category 2: Maintaining trusting relationships until the end, not being alone.

End of life was associated with the wish of having family and close friends around until the end by a third of visitors. Included in this category are statements in which visitors highlighted the importance to feel cared for by people whom they trust. For example, one visitor phrased it as ‘That I am integrated within my personal surrounding (with open doors to everyday life) at home (despite the slow deterioration) and die pain free’ (V205). One visitor stated ‘That I … not be left alone if possible and in a familiar setting’ (V194) or another visitor wrote ‘good contact with my family’ (V78). Another visitor explained it as ‘[being supported by] people who provide hope for the soul without imposing their own attitude on me’ (V216). These trusted people could be healthcare professionals, family members of friends as one visitor stated ‘considerate care by loving family members, friends, and nurses’ (V76).

Category 3: Organizing affairs and having everything settled for the loved ones of the person who dies.

In the third category, a relevant part of the visitors focused on life completion activities and put as priorities the ability to take care of their own matters. They intended to avoid leaving any unfinished business to their loved ones. As one visitor phrased it: ‘… a settled situation for the ones [I] left behind’ (V67). One visitor explained what they believed they wanted to accomplish by stating ‘… that I was able to finish important topics and wishes’ (V154). Organizing their own affairs also meant that when reaching one’s end of life, knowing that the family knows what the dying person would want also provided inner peace as visitor 107 described: ‘… My children know how I want to die. My things are all in order. I can end my life in peace …’

Category 4: Having their family being cared for.

For some visitors, care for their family was central when thinking about what would matter when considering their own end of life. One visitor (V202) stated ‘good care also for my family’ is important, while another visitor (V11) explained ‘… pay not too much attention to myself but the attention should go to all [those] around me’. Visitor 91 mentioned ‘Advice and care for/with the family’.

Category 5: Relief of suffering with the support of knowledgeable people.

The relief of suffering from specific physical and non-physical symptoms by competent healthcare professionals was mentioned by the majority of the visitors. One visitor described it as ‘… competence within the professional care team’ (V155) or ‘… I want to be cared for by a priest’ (V143). Another visitor explained this as ‘… I could die confidently and free of fear / pain free’ (V154) which could imply confidence in knowledgeable people who know how to handle symptoms such as visitor 83 phrased it ‘… that I have carers on whom I can rely’.

Discussion

The study aimed to generate a better understanding of the public’s perspectives of palliative and end-of-life care in a predominantly German-speaking region of Switzerland. In this study, the term palliative care was mostly associated with positive terms such as relief of symptoms and end of life with dignity. This is similar to other findings which show that the public associates palliative care with positive aspects such as good communication by professionals, delivery of comfort and improvement of quality of life.2,30

Moreover and comparable to the findings by McIlfatrick and colleagues, 3 the participants in this study acknowledged palliative care as an interprofessional approach focusing on physical, psychological, social and spiritual areas and a way to support not only patients, but also families. These participants expected collaborative services as a core component of palliative care. This is unlike the results of Lane and colleagues 31 who found that the public was often unaware that palliative care also includes psychological and spiritual support.

Our study identified a strong focus on dying as a part of the visitors’ understanding of palliative care. In addition, a majority of the visitors perceived palliative care primarily as a medical intervention reserved for the last days of life. Unclear whether it is culturally influenced, this narrow view of palliative care is also mentioned in other studies.7,32,33 Interestingly, although visitors mentioned the focus on dying, they were less prone to want to mention their own end of life. This was demonstrated by the fact that visitors rarely acknowledged palliative care as related to their own end of life. What visitors found essential at their own end of life revealed that they were mainly focused on life completion of activities and finding satisfaction in life when considering their own finiteness. This might be because most visitors (96.5%) had a good to very good health status and because, like in other studies, 34 more than half of the visitors probably obtained their knowledge about palliative care through previous contact with these services. Palliative care therefore appeared to be implicitly rather than explicitly associated with the visitors’ own end of life.

Visitors’ frequent perception of palliative care as being equal to end-of-life care and having mainly a medical focus of care may hamper efforts to improve public health initiatives on palliative care. By modifying public misconceptions about what palliative care involves, 8 healthcare professionals may be able to shape and explain to the public what palliative care entails and help overcome the stigma that palliative care is only limited to end-of-life care. A broader understanding and perception of palliative care within the Swiss public, as recommended by the WHO, 35 may lead to increased political pressure. This might result in a need for a new culture and societal value of end-of-life preparation and provision of palliative care services that are comparable to the services available at the beginning of life.

A minority of the visitors recognized palliative care as an approach that should be implemented early in the disease trajectory. This recognition is in line with current guidelines in the medical field 36 and might be attributed to campaigns to raise awareness towards palliative care, advance care planning and efforts of early integration in Switzerland and specifically in the Canton of Bern over the past decade. Comparable to other studies,7,8,13,37 this study shows the need for further knowledge and understanding about palliative care with parts of the Swiss public. Visitors’ personal experiences with palliative care services suggest that their perception of palliative care could be comparable to that of patients with a life-limiting disease who had positively connotated prior contact with or knowledge about palliative care. 34

Limitations and strengths

Some visitors who attended the travelling exhibition may have already been interested in and have had knowledge about palliative care. Therefore, the results of this study may have been influenced by the positive attitude and curiosity of the visitors at the exhibition. The authors had no information about visitors’ knowledge and perception of palliative care prior to visiting the exhibition but many of them (60.3%) stated that they had previous contact with palliative care without describing it in detail. It can also be assumed that the answers of the participants were influenced by the themes presented at the exhibition.

Although the response rate of about 10% could be considered as low, similar studies also report low response rates of 17%, 5 26.2% 38 and up to 27.8%. 33 Since this was one of the first studies conducted in a public exhibition setting in Switzerland, we consider the response of 199 adult visitors as a good starting point for further research in this area. As far as the authors know this is one of the few studies to gather viewpoints from the public in a setting of an exhibition that offered information about palliative care. In addition, the exhibition was not connected to a specific healthcare institution which otherwise could have influenced the perception of the public.

Future research should be conducted with a larger number of members of the public including from different cultural backgrounds to replicate and possibly expand these findings. In addition, it would be beneficial to conduct a study that utilizes mixed methods to further evaluate the public’s perceptions of palliative care after an educational initiative such as an exhibition on palliative care.

Conclusion

Understanding public perceptions about palliative care provides important information to address any potential misconceptions of the meaning of palliative care in this population. Among others, maintaining one’s own dignity as well as dying without suffering was essential to the visitors at the exhibition. The insights from this study could be used to educate the public regarding the specifics of palliative care and to eliminate the stigma that palliative care is only intended for the last days of life. The results may also help healthcare professionals to better understand how the public view palliative care.

New strategies to engage the general population in palliative care initiatives need to be established. Therefore, it is essential that educational initiatives be developed for the public about the importance of an interprofessional and holistic palliative care approach early in the disease trajectory.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all visitors of the exhibition who were willing to share their perspective on what palliative care means to them. The authors also thank all staff members of the exhibition sites who made it possible that data were collected – especially the delegates from the different regions and Ms. Kathrin Sommer from palliative bern. The authors thank Dr. Cynthia King for her support in editing the article.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Monica C. Fliedner  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9018-7571

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9018-7571

Contributor Information

Monica C. Fliedner, University Center for Palliative Care, Department of Oncology, Inselspital, University Hospital Bern, SWAN C518, Freiburgstrasse, 3010 Bern, Switzerland; Department of Health Services Research, Care and Public Health Research Institute (CAPHRI), Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands.

Sofia C. Zambrano, University Center for Palliative Care, Department of Oncology, Inselspital, University Hospital Bern, Bern, Switzerland

Steffen Eychmueller, University Center for Palliative Care, Department of Oncology, Inselspital, University Hospital Bern, Bern, Switzerland.

References

- 1. World Health Organization (WHO). Definition palliative care world health organization, 2002, http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ (accessed 16 February 2014).

- 2. Benini F, Fabris M, Pace DS, et al. Awareness, understanding and attitudes of Italians regarding palliative care. Ann Ist Super Sanita 2011; 47: 253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McIlfatrick S, Noble H, McCorry NK, et al. Exploring public awareness and perceptions of palliative care: a qualitative study. Palliat Med 2014; 28: 273–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hirai K, Kudo T, Akiyama M, et al. Public awareness, knowledge of availability, and readiness for cancer palliative care services: a population-based survey across four regions in Japan. J Palliat Med 2011; 14: 918–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McIlfatrick S, Hasson F, McLaughlin D, et al. Public awareness and attitudes toward palliative care in Northern Ireland. BMC Palliat Care 2013; 12: 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Metzger M, Norton SA, Quinn JR, et al. Patient and family members’ perceptions of palliative care in heart failure. Heart Lung 2013; 42: 112–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Perceptions of palliative care among patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers. CMAJ 2016; 188: E217–E227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Patel P, Lyons L. Examining the knowledge, awareness, and perceptions of palliative care in the general public over time: a scoping literature review. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2020; 37: 481–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kozlov E, McDarby M, Reid MC, et al. Knowledge of palliative care among community-dwelling adults. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2018; 35: 647–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jarrett N, Payne S, Turner P, et al. ‘Someone to talk to’ and ‘pain control’: what people expect from a specialist palliative care team. Palliat Med 1999; 13: 139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wallace J. Public awareness of palliative care: report of the findings of the first national survey in Scotland into public knowledge and understanding of palliative care. Edinburg 2003, https://www.palliativecarescotland.org.uk/content/publications/PublicAwarenesso-PalliativeCare.pdf

- 12. Claxton-Oldfield S, Claxton-Oldfield J, Rishchynski G. Understanding of the term ‘palliative care’: a Canadian survey. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2004; 21: 105–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Grant MS, Back AL, Dettmar NS. Public perceptions of advance care planning, palliative care, and hospice: a scoping review. J Palliat Med 2020; 24: 46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wallerstedt B, Benzein E, Schildmeijer K, et al. What is palliative care? Perceptions of healthcare professionals. Scand J Caring Sci 2019; 33: 77–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kavalieratos D, Mitchell EM, Carey TS, et al. ‘Not the ‘grim reaper service’’: an assessment of provider knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions regarding palliative care referral barriers in heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc 2014; 3: e000544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Berry LL, Castellani R, Stuart B. The branding of palliative care. J Oncol Pract 2016; 12: 48–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hui D, Park M, Liu D, et al. Attitudes and beliefs toward supportive and palliative care referral among hematologic and solid tumor oncology specialists. Oncologist 2015; 20: 1326–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. LeBlanc TW, O’Donnell JD, Crowley-Matoka M, et al. Perceptions of palliative care among hematologic malignancy specialists: a mixed-methods study. J Oncol Pract 2015; 11: e230–e238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fadul N, Elsayem A, Palmer JL, et al. Supportive versus palliative care: what’s in a name? A survey of medical oncologists and midlevel providers at a comprehensive cancer center. Cancer 2009; 115: 2013–2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Maciasz RM, Arnold RM, Chu E, et al. Does it matter what you call it? A randomized trial of language used to describe palliative care services. Support Care Cancer 2013; 21: 3411–3419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rhondali W, Burt S, Wittenberg-Lyles E, et al. Medical oncologists’ perception of palliative care programs and the impact of name change to supportive care on communication with patients during the referral process. Palliat Support Care 2013; 11: 397–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zambrano SC, Centeno C, Larkin PJ, et al. Using the term ‘palliative care’: international survey of how palliative care researchers and academics perceive the term ‘palliative care’. J Palliat Med 2020; 23: 184–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Reyes-Gibby CC, Anderson KO, Shete S, et al. Early referral to supportive care specialists for symptom burden in lung cancer patients: a comparison of non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics, and non-Hispanic blacks. Cancer 2012; 118: 856–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Houska A, Loucka M. Patients’ autonomy at the end of life: a critical review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2019; 57: 835–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kuhl D, Stanbrook MB, Hebert PC. What people want at the end of life. CMAJ 2010; 182: 1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McCaffrey N, Bradley S, Ratcliffe J, et al. What aspects of quality of life are important from palliative care patients’ perspectives? A systematic review of qualitative research. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016; 52: 318.e5–328.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang B, Nilsson ME, Prigerson HG. Factors important to patients’ quality of life at the end of life. Arch Intern Med 2012; 172: 1133–1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lindqvist O, Tishelman C. Room for Death – International museum-visitors’ preferences regarding the end of their life. Soc Sci Med 2015; 139: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mayring P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken. 12th ed. Weinheim: Beltz, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30. McIlfatrick S, Hasson F, Noble H, et al. Exploring public awareness of palliative care – executive summary (ed. Institute of Nursing and Health Research/all Ireland Institute of Hospice and Palliative Care). Belfast: University of Ulster, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lane T, Ramadurai D, Simonetti J. Public awareness and perceptions of palliative and comfort care. Am J Med 2019; 132: 129–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sanjo M, Miyashita M, Morita T, et al. Perceptions of specialized inpatient palliative care: a population-based survey in Japan. J Pain Symptom Manage 2008; 35: 275–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shalev A, Phongtankuel V, Kozlov E, et al. Awareness and misperceptions of hospice and palliative care: a population-based survey study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2018; 35: 431–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Davison SN, Jhangri GS, Koffman J. Knowledge of and attitudes towards palliative care and hospice services among patients with advanced chronic kidney disease. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2016; 6: 66–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. World Health Organization (WHO). Strengthening of palliative care as a component of comprehensive care throughout the life course. World Health Assembly, 2014, http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s21454en/s21454en.pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ferrell BR, Twaddle ML, Melnick A, et al. National consensus project clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care guidelines, 4th edition. J Palliat Med 2018; 21: 1684–1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Slomka J, Prince-Paul M, Webel A, et al. Palliative care, hospice, and advance care planning: views of people living with HIV and other chronic conditions. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2016; 27: 476–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Westerlund C, Tishelman C, Benkel I, et al. Public awareness of palliative care in Sweden. Scand J Public Health 2018; 46: 478–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]