Abstract

Objective

Shared decision making (SDM) tools can help implement guideline recommendations for patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) considering stroke prevention strategies. We sought to characterize all available SDM tools for this purpose and examine their quality and clinical impact.

Methods

We searched through multiple bibliographic databases, social media, and an SDM tool repository from inception to May 2020 and contacted authors of identified SDM tools. Eligible tools had to offer information about warfarin and ≥1 direct oral anticoagulant. We extracted tool characteristics, assessed their adherence to the International Patient Decision Aids Standards, and obtained information about their efficacy in promoting SDM.

Results

We found 14 SDM tools. Most tools provided up-to-date information about the options, but very few included practical considerations (e.g., out-of-pocket cost). Five of these SDM tools, all used by patients prior to the encounter, were tested in trials at high risk of bias and were found to produce small improvements in patient knowledge and reductions in decisional conflict.

Conclusion

Several SDM tools for stroke prevention in AF are available, but whether they promote high-quality SDM is yet to be known. The implementation of guidelines for SDM in this context requires user-centered development and evaluation of SDM tools that can effectively promote high-quality SDM and improve stroke prevention in patients with AF.

Keywords: anticoagulation, atrial fibrillation, cardiovascular prevention, decision aids, shared decision making

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a heart arrhythmia associated with a 5-fold increase in the risk of stroke. It is estimated that 30% of people with AF develop at least 1 cerebrovascular event in their life time1–3; this event is more likely to be fatal in patients with AF (19%–35%) compared to patients without AF (5%–14%). 4 Stroke survivors live with physical and cognitive disabilities, and their families and caregivers often experience social, physical, emotional, and financial difficulties.5–7

Large randomized trials have demonstrated the benefits of anticoagulation in reducing the risk of AF-related strokes, 8 yet many at-risk patients do not receive these benefits9–11 as less than 50% of high-risk patients are treated with anticoagulation therapy 12 and more than 40% discontinue therapy within 12 months.13–18 There are multiple patient- and clinician-associated factors that may lead to underuse of anticoagulants within this population such as inadequate patient/caregiver resources, lack of understanding about risks and benefits, and difficulties with effective communication.19,20

In response to these challenges, and to realize the full benefits of anticoagulation, the 2014 and 2019 guidelines from the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and The Heart Rhythm Society for the management of patients with AF recommended that shared decision making (SDM) be used to individualize antithrombotic care.9,21 This call for SDM emphasizes its role as a patient-centered strategy in forming plans of care that respond well to the threat of stroke in each patient’s clinical and personal contexts.22,23

SDM tools could support the implementation of these guideline recommendations. Effective tools should be feasible to implement in busy clinical practices and could help 1) share tailored information about the available options, 2) clarify the different attributes of the options in patients’ lives and develop preferences about these, 3) support patient-clinician conversations in which these options are considered in the lives of patients, and 4) arrive at an implementable decision. A systematic search conducted in 2016 identified 6 SDM pertinent tools. 24 Since then, direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), included in only 1 of the 6 tools, have increased in use, and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) tied reimbursement to performance and documentation of SDM for patients with AF considering a left atrial appendage closure (LAAC) device. 25

These events have significantly affected SDM surrounding stroke prevention among AF patients. We, therefore, determined that an updated scan of the published record and online resources would be beneficial. The goal of this review was to identify available SDM tools designed to support SDM about stroke prevention for patients with AF and assess their quality and impact on SDM outcomes.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of academic databases and environmental scanning to collect SDM tools and associated literature about their development and efficacy. The current report follows the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA). 26 The protocol of this study can be accessed by request.

Eligibility Criteria

Eligible SDM tools were developed to support SDM about pharmacological and nonpharmacological strategies (e.g., LAAC device) for stroke prevention in patients with AF. These tools were either patient decision aids (supporting the preparation of patients for SDM) or encounter tools (supporting both patients and clinicians participating in SDM). They were required to include warfarin and ≥1 DOAC as stroke prevention options. We also included any study assessing the impact of any eligible SDM tool v. usual care or other active control on SDM.

Data Sources and Search Strategy

Literature search

An experienced librarian (L.P.) designed a search strategy that was carried out in Ovid MEDLINE and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, and Daily, Ovid EMBASE, Ovid PsycINFO, Ovid Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Ovid Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Web of Science, and Scopus. The search was conducted from each database’s inception to May 19, 2020 (Supplemental Material 1). There were no restrictions on study design, language, or date of publication.

Environmental scan

A systematic search of social media platforms Facebook and Twitter was conducted and updated as of July 10, 2020, by introducing different combinations of the words atrial fibrillation and shared decision making in their search bars (Supplementary Material 2). In addition, during the data extraction for the systematic review, we extracted all author names and emails. Each author was emailed up to 2 times and asked to verify the information collected about their SDM tool, to identify missed SDM tools, and to provide access to the content of their tools when not otherwise freely available (Supplementary Material 3). Finally, we conducted a search of the Ottawa Health Research Institute SDM tool inventory, 27 using the terms atrial fibrillation, anticoagulation, and stroke.

Study and SDM Tool Selection

Nine reviewers (V.T.R., O.J.P., N.E.S., T.B., F.B., A.D.T., P.W.O., F.B., and S.J.) working independently and in duplicate assessed each report for eligible SDM tools. To ensure quality and consistency, we performed multiple pilots and teaching rounds until we reached at least 90% of agreement before each phase. Disagreements resulting from full-text screening were resolved by a third author (J.P.B.). Three reviewers (V.T.R., O.J.P., and J.P.B.), working independently and in duplicate, assessed the eligibility of the SDM tools identified through the environmental scan.

Data Extraction

Five reviewers (V.T.R., M.U.-S., N.E.S., C.L.-S., and O.J.P.) extracted features of each SDM tool and each efficacy study. For risk-of-bias assessment, we used the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool 28 on randomized clinical trials and the Newcastle-Ottawa tool 29 on nonrandomized studies.

SDM Tool Features

Two reviewers (J.P.B. and V.T.R.) checked each SDM tool against the International Patient Decision Aids Standards instrument (IPDAS) version 4.0. 30 All conflicts were resolved by discussion. This 35-item tool (Supplementary Material 4) groups standards into 9 domains: information (8 items), outcome probabilities (6 items), values (2 items), decision guidance (2 items), development (6 items), evidence (6 items), disclosure (2 items), plain language (1 item), and evaluation (2 items).

The funding source had no role in the study conception, design, analysis, or interpretation.

Results

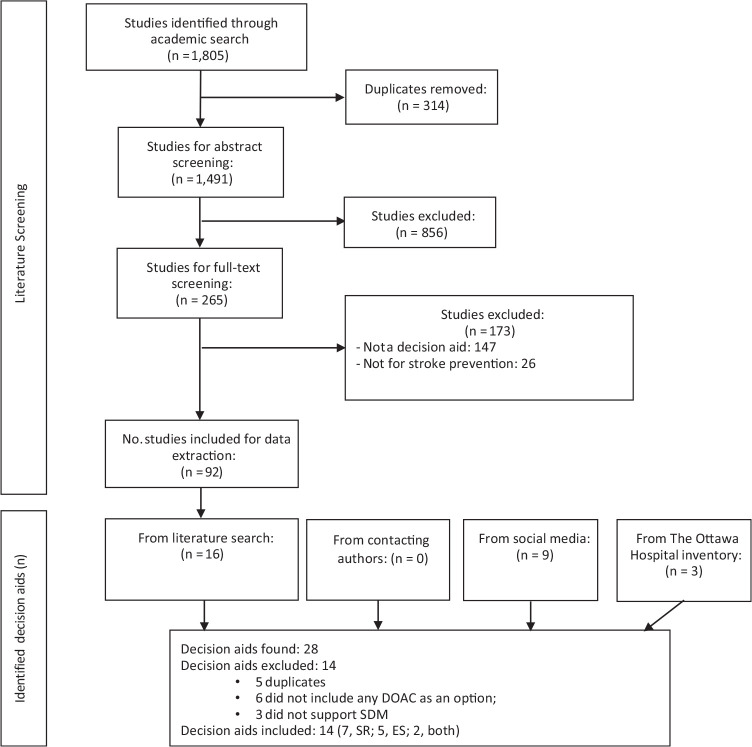

Figure 1 describes the results of our search. Table 1 and Supplementary Material 5 describe the 14 included SDM tools.31–55 All but 2 were in English; the mAF app 42 was in Chinese and MATCh AFib43,44 in Portuguese. When examining their intended use, 3 were patient decision aids, 5 were encounter tools, 4 had features of both, and 2 were not classifiable because of either lack of information or access to the tool itself. Most tools offered information about the available treatment options, mostly warfarin and DOACs, and the probabilities of specific outcomes. All the tools included tailorable risks of stroke and bleeding (mostly using CHA2DS2-VASc and HASBLED calculators) and compared different options of anticoagulation based on dosing, frequency of laboratory testing, drug side effects/interactions, and costs.

Figure 1.

Eligibility of decision aids.

Table 1.

List and Overall Characteristics of Decision Aids

| Decision Aid | Institution | Period of Development | Platform | Patient or Encounter Decision Aid | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AF Manager31,32 | European Society of Cardiology (ESC) | 2013 | Mobile application | Patient and encounter decision aid | Through “ESC pocket guidelines” app for apple and android devices |

| Afib: Which anticoagulant should I take to prevent stroke? 41 | Healthwise, Inc., Canada | 2017 | Web application | Patient decision aid | https://www.uwhealth.org/health/topic/decisionpoint/atrial-fibrillation-which-anticoagulant-should-i-take-to-prevent-stroke/abl2009.html |

| Anticoagulation Choice45–48 | Mayo Clinic, USA | 2016 | Web application | Encounter decision aid | https://anticoagulationdecisionaid.mayoclinic.org/ |

| Atrial Fibrillation Shared Decision Making (AFSDM) Tool33–35 | University of Cincinnati, USA | NA | Web application | Encounter decision aid | Not available |

| Blood Thinners for Atrial Fibrillation 36 | Healthwise, Inc., Canada | 2015 | Web application | Not sure | https://decision.healthwise.net/Decision-Aids/AFIB-Patient-View/ |

| CardioSmart 37 | American College of Cardiology, USA | 2017 | Web application and paper-based aid | Not sure | https://www.cardiosmart.org/SDM/Decision-Aids/Find-Decision-Aids/Atrial-Fibrillation |

| Don’t Wait to Anticoagulate (DWAC) 38 | West of England Academic Health Science Network, UK | 2016 | Web application and paper based aid | Patient and encounter decision aid | http://www.dontwaittoanticoagulate.com/ |

| Healthdecision39,40 | UW Health, USA and Dartmouth–Hitchcock Medical Center, USA | 2017 | Web application | Encounter decision aid | https://www.healthdecision.org/tool.html |

| mAF app42,a | Chinese PLA General Hospital, China | NA | Mobile application | Patient decision aid and encounter decision aid | Not available |

| Mhealth Application for Anticoagulation Care in Atrial Fibrillation (MATCh AFib)43,44,a | Instituto de Cardiologia—Fundação Universitária de Cardiologia (IC/FUC), Brazil | 2017 | Mobile application | Encounter decision aid | Not available |

| PtDA (Patient Decision Aids)51–53 | McMaster University | NA | Paper-based aid | Patient decision aid | https://rsjh.ca/holbrook/NOACs_warfarin_decision_aid_booklet_chart_May26_16.pdf |

| NICE Decision Aid49,50 | The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, UK | 2014 | Paper-based aid | Patient decision aid and encounter decision aid | https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg180/resources/patient-decision-aid-pdf-243734797 |

| WISDM for A FIB 54 | EBSCO health, USA | 2017 | Web application | Encounter decision aid | http://wisdmforafib.com/ |

| PDA 55 | The University of British Columbia | 2016–2017 | Web application | Patient decision aid | Contact the authors to request access |

NA, not available.

All but these 2 decision aids are available in English: the content of mAF app and MATCh AFib are in Chinese and Portuguese, respectively.

SDM Tool Quality Assessment

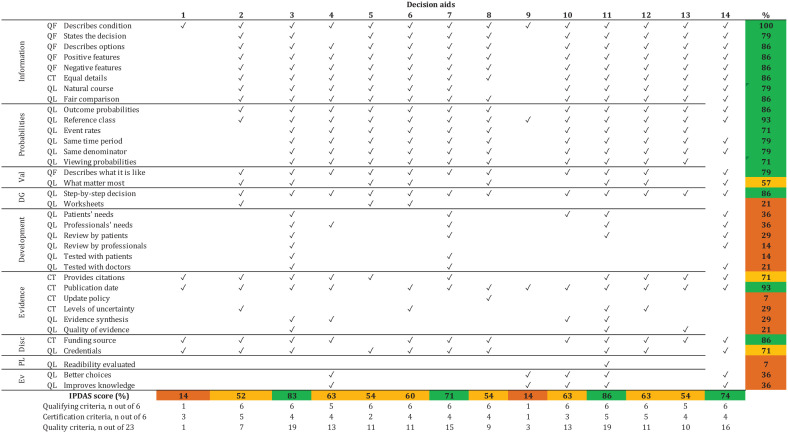

Twelve decision aids met more than 50% of the IPDAS items (Figure 2). The top-rated tools were PtDA,51–53 Anticoagulation Choice,45–48 Don’t Wait to Anticoagulate, 38 and PDA, 55 which met >70% of all IPDAS items. PtDA was the only tool that assessed for readability. Only 2 tools, Anticoagulation Choice and Don’t Wait to Anticoagulate, reported field testing with patients and clinicians.

Figure 2.

Quality of decision aids: IPDAS checklist.

SDM Tools’ Effectiveness and Risk-of-Bias Assessment

Six studies, including 2 randomized trials42,48 and 4 nonrandomized studies,34,43,53,55 at high risk of bias reported the effect of SDM tools on SDM outcomes (Table 2 and Supplementary Material 6).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Studies Evaluating Effectiveness

| Study, Year | No. of Participants | Participants | Design | Decision Aid | Setting | Mean Age, y | Female (%) | CHA2DS2-VASC Mean | HAS-BLED Mean | Prior Stroke (%) | Overall Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kunneman et al., 2020 48 | Adults with atrial fibrillation | Randomized controlled trial | Anticoagulation Choice | Outpatients and inpatients, USA | 71 | 39.2 | 3.46 | 2.08 | NA | High | |

| Loewen et al., 2019 55 | 37 | Adults with chronic atrial fibrillation | Nonrandomized study, single arm | PDA | Outpatient, Canada | 71 | 57 | 2.38 | 2.18 | 8 | High |

| Eckman et al., 2018 34 | 76 | Adults with atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter | Nonrandomized study, single arm | AFSDM | Outpatient, USA | 65.7 | 35 | 3 | 1.9 | 11 | High |

| Stephan et al., 2018 43 | 20 | Adults with atrial fibrillation | Nonrandomized study, single arm | MATCH-Afib | Outpatient, Brazil | 67.7 | 40 | 3 | 2 | 17 | High |

| Guo et al., 2017 42 | 209 | Adults with atrial fibrillation | Randomized controlled trial | mAF app | General hospital, China | 69 | 44 | 2.6 | 1.5 | 9 | High |

| Hong et al., 2013 53 | 35 | Adults aged >60 y | Nonrandomized study, single arm | PtDA | Inpatient and outpatient, Canada | 62.7 | 37 | NA | NA | 20 | High |

AFSDM, Atrial Fibrillation Shared Decision Making; NA, not available; PDA, patient decision aid.

The outcomes evaluated included knowledge, decisional conflict, quality of life, and medication adherence. These results are further described in Table 3. In summary, knowledge was evaluated and found significantly improved with the use of SDM tools in 5 studies. One of the trials 48 reported minimal change in knowledge probably due to nearly optimal levels at baseline. Five studies reported low decisional conflict immediately postintervention (9–19 out of 100 points).34,43,48,53,55 The only study that reported preintervention scores demonstrated a large effect associated with the intervention. 34 Quality of life was evaluated in only 1 randomized trial, which had substantial between-arm imbalance at baseline. 42 Two studies measured and reported statistically significant improvements in adherence to anticoagulants with the use of the SDM tool when compared to adherence at baseline and in the control group.34,42

Table 3.

Summary of Findings

| Study, Year | DCS | Knowledge | Quality of Life | Adherence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kunneman et al., 2020 48 | DCS (0–100). Low mean decisional conflict in both arms (SD): intervention, 16.6 (14.4), and control 17.9 (14.9); the effect size was nonsignificant: −1.2 (95% CI, −3.2 to 0.6) | Knowledge test (0.6). The number of patients achieving a perfect score was similar to intervention (31.0%) and control (28.6%) (effect size: 1.01; 95% CI, 1.0 to 1.02). | NA | NA |

| Loewen et al., 2019 55 | DCS (0–100). Significantly lower decisional conflict postintervention (mean, 13.7) compared to baseline (mean, 34.9). | AFKA (0–10) Significantly increased participants’ AF knowledge from baseline (mean, 7.93) compared to postintervention (mean, 8.61; P = 0.02). | NA | NA |

| Eckman et al., 2018 34 | DCS (0–100). Significant decrease postintervention (mean, 9.1) compared to baseline (mean, 31.4). | Knowledge test (0–10). Statistically significant increase after intervention (mean, 9.1; SD, 1.25) compared to baseline (mean, 8.4; SD, 1.5). | NA | The Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (0–7). Increase after intervention (mean, 6.4; SD, 0.87) compared to baseline (mean, 5.9; SD, 1.3). |

| Stephan et al., 2018 43 | DCS (0–100). Low decisional conflict after intervention (mean, 11; SD, 16). No baseline data. | Knowledge test (0–8). Statistically significant increase after decision aid (mean, 7.2) compared to baseline (mean, 4.7). | NA | NA |

| Guo et al., 2017 42 | NA | Knowledge test (0–11). Statistically significant increase after 3 months in the intervention arm compared to controls. However, magnitude was not reported. | EuroQol (0–100). Statistically significant difference between intervention (mean, 87.2) and control arms (mean, 69.9). Baseline QoL was very different among groups (86.5 v. 71.3, respectively). | Pharmacy Quality Alliance adherence measure (0–36). At 3 months, lower propensity to leave the medication was observed in the intervention (mean, 2) than controls (mean, 4). |

| Hong et al., 2013 53 | DCS (0–100). Low decisional conflict after intervention (mean, 18.9; SD, 10.8). However, no baseline data. | Knowledge test (0–7). Statistically significant increase after intervention (mean, 6.43; SD, 0.8) compared to baseline (mean, 4.6; SD, 1.5). | NA | NA |

AF, atrial fibrillation; AFKA, AF knowledge assessment; CI, confidence interval; DCS, decisional conflict score; NA, not avaialble; QoL, quality of life.

Discussion

We found 14 SDM tools for patients with AF considering stroke prevention strategies. Most were patient decision aids that offered information about the available treatment options, described probabilities of specific outcomes, included some type of value clarification activity, and included information about cost, required lab tests, dosing, potential changes in diet, and potential side effects; very few included information about other lifestyle changes and the burden of treatment (e.g., what it means to take a pill daily or what it takes to attend periodic clinic appointments). Patient decision aids improve patient knowledge and decisional conflict. Encounter SDM tools have not been evaluated. None of the 14 tools met all IPDAS certification criteria, 30 although most met 50% to 75% of them. Finally, in light of the CMS statement about the mandatory use of SDM when considering percutaneous LAAC, 25 we found only 1 SDM tool (CardioSmart) that included LAAC as an option.

One possible limitation of this study might have been not including government or nongovernmental organizations’ websites in our search strategy. We believe, however, that our search strategy ensured the inclusion of the SDM tools more available to clinicians and patients. In addition, the data on the development of the SDM tools were scarce. Most authors did not publish a article explaining the development process or included this information on their websites. Lack of reporting was considered as unmet IPDAS criteria by our group because we considered that the information of the development process should have been available to users in their published manuscripts, websites, or tools themselves. This decision could have led to lower IPDAS scores across all tools included in this analysis. The current study updates the database of existing SDM tools about anticoagulation for patients with AF. Compared to the review by O’Neill et al., 24 we found 5 additional tools, including the PtDA,51–53 which met the largest number of IPDAS standards. Our review also draws attention to the lack of participation of patients and clinicians in the content, design, and implementation of the tools and the lack of development of the tools within the context of their use. 56 If we expect tools to be applied within the clinical setting, they must be developed in a way that places the patient at the center of the development process. This can best be done through early and frequent testing of prototypes within actual clinical encounters of clinicians and AF patients facing the decision about whether and how to anticoagulate. Furthermore, for SDM tools to be ready for use and implementation, they should undergo rigorous efficacy testing. Yet, our review found that only a small subset of the tools underwent any type of testing. These studies, at high risk of bias, showed that the tools improve outcomes such as knowledge and decisional conflict, which may be useful to achieve SDM but at the same time might not be enough by themselves. None of studies directly tested whether the tools facilitated SDM. Some studies measured long-term, yet still indirect, consequences of SDM such as adherence and quality of life, but the results were inconclusive.

Conclusions

Several SDM tools are available, but their efficacy in promoting high-quality SDM is unknown. SDM tools should be rigorously evaluated in terms of their ability to support SDM and affect patient care.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-doc-1-mdm-10.1177_0272989X211005655 for Shared Decision Making Tools for People Facing Stroke Prevention Strategies in Atrial Fibrillation: A Systematic Review and Environmental Scan by Victor D. Torres Roldan, Sarah R. Brand-McCarthy, Oscar J. Ponce, Tereza Belluzzo, Meritxell Urtecho, Nataly R. Espinoza Suarez, Freddy J. K. Toloza, Anjali D. Thota, Paige W. Organick, Francisco Barrera, Carolina Liu-Sanchez, Soumya Jaladi, Larry Prokop, Elissa M. Ozanne, Angela Fagerlin, Ian G. Hargraves, Peter A. Noseworthy, Victor M. Montori and Juan P. Brito in Medical Decision Making

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-mdm-10.1177_0272989X211005655 for Shared Decision Making Tools for People Facing Stroke Prevention Strategies in Atrial Fibrillation: A Systematic Review and Environmental Scan by Victor D. Torres Roldan, Sarah R. Brand-McCarthy, Oscar J. Ponce, Tereza Belluzzo, Meritxell Urtecho, Nataly R. Espinoza Suarez, Freddy J. K. Toloza, Anjali D. Thota, Paige W. Organick, Francisco Barrera, Carolina Liu-Sanchez, Soumya Jaladi, Larry Prokop, Elissa M. Ozanne, Angela Fagerlin, Ian G. Hargraves, Peter A. Noseworthy, Victor M. Montori and Juan P. Brito in Medical Decision Making

Footnotes

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The investigators Juan P. Brito, Ian G. Hargraves, Victor M. Montori, and Peter A. Noseworthy participated in the development of the Anticoagulation Choice, which is one of the shared decision making tools included in this review. The rest of the authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding this work.

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Financial support for this study was provided entirely by a grant from American Heart Association and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. The funding agreement ensured the authors’ independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, writing, and publishing the report.

ORCID iDs: Victor D. Torres Roldan  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8683-4767

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8683-4767

Meritxell Urtecho  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9123-0922

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9123-0922

Nataly R. Espinoza Suarez  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4644-5809

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4644-5809

Elissa M. Ozanne  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5352-9459

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5352-9459

Victor M. Montori  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0595-2898

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0595-2898

Supplemental Material: Supplementary material for this article is available on the Medical Decision Making website at http://journals.sagepub.com/home/mdm.

Contributor Information

Victor D. Torres Roldan, Knowledge and Evaluation Research (KER) Unit, Department of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA

Sarah R. Brand-McCarthy, Knowledge and Evaluation Research (KER) Unit, Department of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA Department of Psychiatry and Psychology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA.

Oscar J. Ponce, Knowledge and Evaluation Research (KER) Unit, Department of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA

Tereza Belluzzo, General Medicine, Charles University in Prague, Medical Faculty of Hradec Králové, Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic.

Meritxell Urtecho, Knowledge and Evaluation Research (KER) Unit, Department of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA.

Nataly R. Espinoza Suarez, Knowledge and Evaluation Research (KER) Unit, Department of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA

Freddy J. K. Toloza, Knowledge and Evaluation Research (KER) Unit, Department of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA

Anjali D. Thota, Knowledge and Evaluation Research (KER) Unit, Department of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA

Paige W. Organick, Knowledge and Evaluation Research (KER) Unit, Department of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA

Francisco Barrera, Knowledge and Evaluation Research (KER) Unit, Department of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA; Plataforma INVEST Medicina UANL-KER Unit Mayo Clinic (KER Unit Mexico), School of Medicine, Universidad Autonoma de Nuevo Leon, Monterrey, Nuevo Leon, Mexico.

Carolina Liu-Sanchez, School of Medicine, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, Lima, Peru.

Soumya Jaladi, Knowledge and Evaluation Research (KER) Unit, Department of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA.

Larry Prokop, Department of Library-Public Services, Mayo Clinic, Rochester MN, USA.

Elissa M. Ozanne, Department of Population Health Sciences, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA

Angela Fagerlin, Department of Population Health Sciences, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA; Salt Lake City VA Informatics Decision-Enhancement and Analytic Sciences (IDEAS) Center for Innovation.

Ian G. Hargraves, Knowledge and Evaluation Research (KER) Unit, Department of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA

Peter A. Noseworthy, Knowledge and Evaluation Research (KER) Unit, Department of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA.

Victor M. Montori, Knowledge and Evaluation Research (KER) Unit, Department of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA

Juan P. Brito, Knowledge and Evaluation Research (KER) Unit, Department of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA.

References

- 1. Bjorck S, Palaszewski B, Friberg L, Bergfeldt L. Atrial fibrillation, stroke risk, and warfarin therapy revisited: a population-based study. Stroke. 2013;44(11):3103–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lip G, Lane D. Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. JAMA. 2015;313(19):1950–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lloyd-Jones D, Wang T, Leip E, et al. Lifetime risk for development of atrial fibrillation: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2004;110(9):1042–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Miller P, Andersson F, Kalra L. Are cost benefits of anticoagulation for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation underestimated? Stroke. 2005;36(2):360–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Feigin VL, Forouzanfar MH, Krishnamurthi R, et al. Global and regional burden of stroke during 1990–2010: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2014;383(9913):245–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McGrath ER, Kapral MK, Fang J, et al. Association of atrial fibrillation with mortality and disability after ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2013;81(9):825–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jaracz K, Grabowska-Fudala B, Górna K, Jaracz J, Moczko J, Kozubski W. Burden in caregivers of long-term stroke survivors: prevalence and determinants at 6 months and 5 years after stroke. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(8):1011–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reynolds MW, Fahrbach K, Hauch O, et al. Warfarin anticoagulation and outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Chest. 2004;126(6):1938–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. January C, Wann L, Alpert J, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(21):e1–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Keach JW, Bradley SM, Turakhia MP, Maddox TM. Early detection of occult atrial fibrillation and stroke prevention. Heart. 2015;101(14):1097–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Qin D, Leef G, Alam MB, et al. Patient outcomes according to adherence to treatment guidelines for rhythm control of atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(4):e001793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ogilvie I, Newton N, Welner S, Cowell W, Lip G, Lane D. Underuse of oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2010;123(7):638–45.e634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gallagher A, Rietbrock S, Plumb J, van Staa T. Initiation and persistence of warfarin or aspirin in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation in general practice: do the appropriate patients receive stroke prophylaxis? J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6(9):1500–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hylek E, Evans-Molina C, Shea C, Henault L, Regan S. Major hemorrhage and tolerability of warfarin in the first year of therapy among elderly patients with atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2007;115(21):2689–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mant J, Hobbs F, Fletcher K, et al. Warfarin versus aspirin for stroke prevention in an elderly community population with atrial fibrillation (the Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Treatment of the Aged Study, BAFTA): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370(9586):493–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rash A, Downes T, Portner R, Yeo W, Morgan N, Channer K. A randomised controlled trial of warfarin versus aspirin for stroke prevention in octogenarians with atrial fibrillation (WASPO). Age Ageing. 2007;36(2):151–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Parker C, Chen Z, Price M, et al. Adherence to warfarin assessed by electronic pill caps, clinician assessment, and patient reports: results from the IN-RANGE study. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(9):1254–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Casciano J, Dotiwala Z, Martin B, Kwong W. The costs of warfarin underuse and nonadherence in patients with atrial fibrillation: a commercial insurer perspective. J Manag Care Pharm. 2013;19(4):302–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gumbinger C, Holstein T, Stock C, Rizos T, Horstmann S, Veltkamp R. Reasons underlying nonadherence to and discontinuation of anticoagulation in secondary stroke prevention among patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur Neurol. 2015;73(3–4):184–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Steinberg B, Kim S, Thomas L, et al. Lack of concordance between empirical scores and physician assessments of stroke and bleeding risk in atrial fibrillation: results from the Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation (ORBIT-AF) registry. Circulation. 2014;129(20):2005–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H, et al. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(1):104–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Breslin M, Mullan RJ, Montori VM. The design of a decision aid about diabetes medications for use during the consultation with patients with type 2 diabetes. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73(3):465–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Montori VM, Breslin M, Maleska M, Weymiller AJ. Creating a conversation: insights from the development of a decision aid. PLoS Med. 2007;4(8):e233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. O’Neill ES, Grande SW, Sherman A, Elwyn G, Coylewright M. Availability of patient decision aids for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Am Heart J. 2017;191:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Decision memo for percutaneous left atrial appendage (LAA) closure therapy. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=281

- 26. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. The Ottawa Hospital. A to Z inventory of decision aids. Available from: https://decisionaid.ohri.ca

- 28. Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- 30. Joseph-Williams N, Newcombe R, Politi M, et al. Toward minimum standards for certifying patient decision aids: a modified Delphi consensus process. Med Decis Making. 2014;34(6):699–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kotecha D, Kirchhof P. ESC apps for atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(35):2643–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kotecha D, Chua WWL, Fabritz L, et al. European Society of Cardiology smartphone and tablet applications for patients with atrial fibrillation and their health care providers. Europace. 2018;20(2):225–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wess ML, Schauer DP, Johnston JA, et al. Application of a decision support tool for anticoagulation in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(4):411–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Eckman MH, Costea A, Attari M, et al. Shared decision-making tool for thromboprophylaxis in atrial fibrillation: a feasibility study. Am Heart J. 2018;199:13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wess ML, Saleem JJ, Tsevat J, et al. Usability of an atrial fibrillation anticoagulation decision-support tool. J Prim Care Community Health. 2011;2(2):100–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Healthwise. Blood thinners for atrial fibrillation. Available from: https://decision.healthwise.net/Decision-Aids/AFIB-Patient-View

- 37. American College of Cardiology. Atrial fibrillation: anticoagulants/left atrial appendage (LAA) closure. Available from: https://www.cardiosmart.org/SDM/Decision-Aids/Find-Decision-Aids/Atrial-Fibrillation

- 38. West of England Academic Health Science Network. Don’t wait to anticoagulate. Available from: http://www.dontwaittoanticoagulate.com

- 39. Healthdecision. Atrial fibrillation tool. Available from: https://www.healthdecision.org/tool.html#/

- 40. Coylewright M, Holmes D. Caution regarding government-mandated shared decision making for patients with atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2017;135(23):2211–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Healthwise Inc. Atrial fibrillation: which anticoagulant should I take to prevent stroke? Available from: https://www.uwhealth.org/health/topic/decisionpoint/atrial-fibrillation-which-anticoagulant-should-i-take-to-prevent-stroke/abl2009.html

- 42. Guo Y, Chen Y, Lane DA, Liu L, Wang Y, Lip GY. Mobile health technology for atrial fibrillation management integrating decision support, education, and patient involvement: mAF app trial. Am J Med. 2017;130(12):1388–96.e1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Stephan LS, Almeida ED, Guimarães RB, et al. Oral anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation: development and evaluation of a mobile health application to support shared decision-making. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2018;110(1):7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Stephan LS, Almeida E, Guimaraes RB, et al. Processes and recommendations for creating mHealth apps for low-income populations. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2017;5(4):e41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mayo Clinic. Anticoagulation choice decision aid. Available from: https://anticoagulationdecisionaid.mayoclinic.org

- 46. Zeballos-Palacios CL, Hargraves IG, Noseworthy PA, et al. Developing a conversation aid to support shared decision making: reflections on designing anticoagulation choice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(4):686–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kunneman M, Branda ME, Noseworthy PA, et al. Shared decision making for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2017;18(1):443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kunneman M, Branda ME, Hargraves IG, et al. Assessment of shared decision-making for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(9):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Atrial fibrillation: medicines to help reduce your risk of a stroke—what are the options? Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg180/resources/atrial-fibrillation-medicines-to-help-reduce-your-risk-of-a-stroke-what-are-the-options-patient-decision-aid-pdf-243734797

- 50. Baicus C, Delcea C, Dima A, Oprisan E, Jurcut C, Dan GA. Influence of decision aids on oral anticoagulant prescribing among physicians: a randomised trial. Eur J Clin Invest. 2017;47(9):649–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fatima S, Holbrook A, Schulman S, Park S, Troyan S, Curnew G. Development and validation of a decision aid for choosing among antithrombotic agents for atrial fibrillation. Thrombosis Res. 2016;145:143–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Holbrook A, Pullenayegum E, Troyan S, Nikitovic M, Crowther M. Personalized benefit-harm information influences patient decisions regarding warfarin. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol. 2013;20:e406–15. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hong C, Kim S, Curnew G, Schulman S, Pullenayegum E, Holbrook A. Validation of a patient decision aid for choosing between dabigatran and warfarin for atrial fibrillation. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol. 2013;20:e229–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dynamed. Wisdmforafib. EBSCO health. Available from: http://wisdmforafib.com/

- 55. Loewen PS, Bansback N, Hicklin J, et al. Evaluating the effect of a patient decision aid for atrial fibrillation stroke prevention therapy. Ann Pharmacother. 2019;53(7):665–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Witteman HO, Chipenda Dansokho S, Colquhoun H, et al. Twelve lessons learned for effective research partnerships between patients, caregivers, clinicians, academic researchers, and other stakeholders. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(4):558–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-doc-1-mdm-10.1177_0272989X211005655 for Shared Decision Making Tools for People Facing Stroke Prevention Strategies in Atrial Fibrillation: A Systematic Review and Environmental Scan by Victor D. Torres Roldan, Sarah R. Brand-McCarthy, Oscar J. Ponce, Tereza Belluzzo, Meritxell Urtecho, Nataly R. Espinoza Suarez, Freddy J. K. Toloza, Anjali D. Thota, Paige W. Organick, Francisco Barrera, Carolina Liu-Sanchez, Soumya Jaladi, Larry Prokop, Elissa M. Ozanne, Angela Fagerlin, Ian G. Hargraves, Peter A. Noseworthy, Victor M. Montori and Juan P. Brito in Medical Decision Making

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-mdm-10.1177_0272989X211005655 for Shared Decision Making Tools for People Facing Stroke Prevention Strategies in Atrial Fibrillation: A Systematic Review and Environmental Scan by Victor D. Torres Roldan, Sarah R. Brand-McCarthy, Oscar J. Ponce, Tereza Belluzzo, Meritxell Urtecho, Nataly R. Espinoza Suarez, Freddy J. K. Toloza, Anjali D. Thota, Paige W. Organick, Francisco Barrera, Carolina Liu-Sanchez, Soumya Jaladi, Larry Prokop, Elissa M. Ozanne, Angela Fagerlin, Ian G. Hargraves, Peter A. Noseworthy, Victor M. Montori and Juan P. Brito in Medical Decision Making