Abstract

Only few genes have been confidently identified to be involved in the Follicular (FO) and Marginal Zone (MZ) B cell differentiation, migration, and retention in the periphery. Our group previously observed that IKKα kinase inactive mutant mice IKKαK44A/K44A have significantly lower number of MZ B cells whereas FO B cell numbers appeared relatively normal. Because kinase dead IKKα can retain some of its biological functions that may interfere in revealing its actual role in the MZ and FO B cell differentiation. Therefore, in the current study, we genetically deleted IKKα from the pro-B cell lineage that revealed novel functions of IKKα in the MZ and FO B lymphocyte development. The loss of IKKα produces a significant decline in the percentage of immature B lymphocytes, mature marginal zone B cells, and follicular B cells along with a severe disruption of splenic architecture of marginal and follicular zones. IKKα deficiency affect the recirculation of mature B cells through bone marrow. A transplant of IKKα knockout fetal liver cells into Rag−/− mice shows a significant reduction compared to control in the B cells recirculating through bone marrow. To reveal the genes important in the B cell migration, a high throughput gene expression analysis was performed on the IKKα deficient recirculating mature B cells (B220+IgMhi). That revealed significant changes in the expression of genes involved in the B lymphocyte survival, homing and migration. And several among those genes identified belong to G protein family. Taken together, this study demonstrates that IKKα forms a vial axis controlling the genes involved in MZ and FO B cell differentiation and migration.

Introduction

Bone marrow derived B cell progenitors differentiate into mature B cells after passing through series of developmental checkpoints [1]. One important checkpoint is B cell antigen receptor (BCR) heavy and light chain gene rearrangements. After the successful gene rearrangement and receptor editing, cognate antigens react with BCR [2]. The BCR signaling allows differentiation of immature B cells into mature B2 B cell lineage through transient transitional (T1 and T2) B cell stages. B cells that react strongly with self-antigens are deleted through negative selection, while as cells that react with low affinity escape deletion and are positively selected to differentiate into mature B cells [3]. The immature/transitional B cells show a characteristic rapid turnover in vivo [4]. The mature B cells acquire the ability to recirculate through the secondary lymphoid organs and differentiate into follicular (FO) and Marginal zone (MZ) B cells [2]. The recirculating B cells homing to the B cell follicles in secondary lymphoid organs and to the bone marrow are termed as follicular (FO) B cells. FO B cells are, thus, appropriately positioned to perform T cell dependent immune functions in the secondary lymphoid organs, and to clear blood-borne bacterial pathogens from the bone marrow in a T cell independent but innate immune system dependent manner [5]. A relatively small percentage of mature B cells are sessile, anatomically resident around the white pulp of the spleen between the marginal sinus and the red pulp. These resident B cells are termed as Marginal zone (MZ) B cells. Marginal zone is harbored by metallophillic and marginal zone (MZ) macrophages [6]. The MZ B cells represent 10% of memory B cells in rodents and 40% of human memory B cells. The MZ B cells have potential to self-renew and can survive indefinitely [5, 7, 8]. MZ B cells generate rapid T cell independent and T cell dependent antibody responses against blood-borne bacterial antigens [9, 10]. Unlike FO B cells, MZ B cells express polyreactive B cell receptors (BCRs) and high densities of Toll like receptors (TLRs) [11]. Phenotypically, the cell surface markers, IgM, IgD, CD21, CD23, and CD1d distinguish FO and MZ B cells. FO B cells are IgMhi, IgDlo, CD21mid, CD23+, these are also referred to as Follicular type I B cells. While as IgMhi, IgDlo, CD21hi, CD23+ are referred to as Follicular type II. MZ B cells are phenotypically, IgMhi, IgDlo, CD21hi, CD1dhi, CD23− [7, 12]. The MZ B cells express high levels of CD1d, which is a non-classical MHC class I molecule that allows them to present lipid antigens to the invariant natural killer T cells (iNKT) [13].

The molecular mechanism underlying cell fate decisions in the newly formed (NF) immature/transitional B cells to differentiate into FO and MZ B cells is incompletely understood [5, 7]. Likewise, little is known about the molecular signals and transcriptional switches driving the retention of MZ B cells in the marginal zone of spleen, and the immigration of FO B cells from secondary lymphoid organs. Nevertheless, the B cell receptor signaling in the immature B cells is reported to play crucial role in the MZ and FO B cell fate choices. For example, Wen et al. [14] demonstrated that crosslinking of low dose self-antigen, Thy-1/CD90, with mice expressing monoclonal BCR promotes marginal zone B cell development. In addition, mice lacking serum IgM show imbalance in the MZ and FO B cell numbers, demonstrating the essential role of BCR signaling in the MZ and FO B cell development [15]. The mice lacking Aioles gene show enhanced maturation of FO B cells whereas MZ B cell development is severely disrupted [16]. Similar phenotype is observed in the mice lacking CD19, PYK-2 tyrosine kinase and NF-κBp50 [8, 17–19]. Likewise, Notch family receptors play major role in the MZ B cell development. In two independent studies, one by Saito et al. and other by Hozumi et al. [20, 21] demonstrated that Notch2 conditional knockout mice and Delta-like1 null mice failed to generate marginal zone B cells. The HLH protein Id2 has shown to be important for MZ B cell differentiation [22]. The MZ and FO B cell development is also perturbed by the conditional deletion of Interferon regulatory factor 8 (IRF8) from CD19+ B cells using a CD19-Cre [23]. In the absence of IRF8, both MZ and FO B cell populations expand indicating a lineage restrictive role of IRF8.

We recently uncovered the role of IKKα kinase in early B cell development [24]. By using novel IKKα kinase dead knockin mutant mice IKKαK44A/K44A in which lysine 44—an ATP binding site—is replaced with alanines [25], we showed that IKKα regulates early B cell development by targeting Pax5 gene through NF-κB transcription factor dimers composed of p65, RelB, p50, and p52. In IKKαK44A/K44A mice, due to the lack of B cell lineage commitment, an aberrant myeloid-erythroid lineage development was observed. Unlike to other IKKα knockin mutant mice, IKKαAA/AA shows near normal levels of IKKα protein expression comparable to wild type mice [26]. A reduced expression of IKKα messenger RNA and protein expression is observed in IKKαK44A/K44A mice. That imposes a complete block of IKKα kinase activity and p100 processing in B220+ B cells [24]. Therefore, unlike to IKKαK44A/K44A mice, IKKαAA/AA knockin mutant mice and IKKα−/− radiation chimeras produce defect only in the mature B cell development [26, 27]. However, these studies and others [28] did not evaluate specifically the role of IKKα in the MZ and FO B cell differentiation and migration. Interestingly, we had previously observed that IKKαK44A/K44A mice have significantly reduced number of MZ B cells whereas FO B cells appeared normal [25]. Therefore, to gain insights into the role of IKKα in the MZ and FO B cell differentiation, we generated a new mouse strain in which IKKα was conditionally deleted from CD19+ pro-B cell lineage. Our results demonstrated previously unknown role of IKKα in controlling the genes important for the differentiation, survival, and migration of recirculating mature B cells.

Results

IKKα deletion from the pro-B cell lineage disrupts the marginal and follicular B cell zones

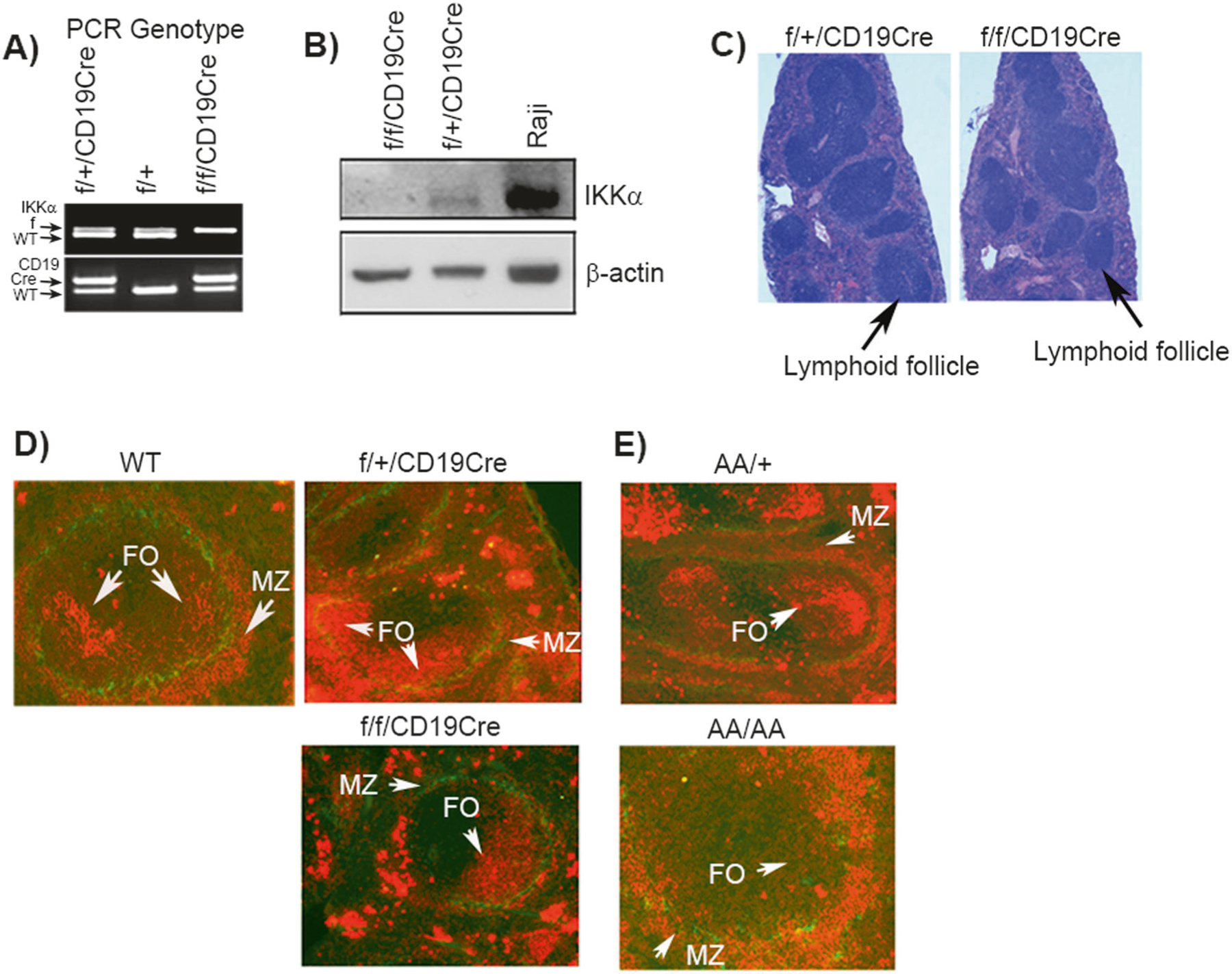

To study the role of IKKα in the MZ and FO B cell differentiation, we generated a mouse strain that have IKKα deleted from the committed B cell lineage. Crosses were performed between the CD19-Cre+/− and IKKαf/+ to generate the mice with genotypes, CD19Cre+/−IKKαf/f (hereafter IKKαcKO), littermate control CD19Cre+/−IKKαf/+ (hereafter IKKαhet) and wild type (WT). The mice with the genotypes presented in Fig. 1a were used in the entire study. In addition, we also used IKKα kinase inactive knockin mice, IKKαAA/AA. The IKKα hetrozygotes (IKKαhet) were phenotypically similar with the wild type mice.

Fig. 1.

IKKα deletion from pro-B cells disrupt Marginal and Follicular B cell zones. a The PCR showing the genotypes of IKKαf/fCD19-Cre (IKKαcKO) and control IKKαf/+CD19-Cre (IKKαhet) mice. The expression of wild type (wt), floxed (f) and Cre allele are indicated with arrows. b Western blot showing the expression of IKKα in bone marrow B220-enrich, column-purified B220+ cells; β-actin is the protein loading control. Raji cell line lysate was used as a positive control for IKKα expression. c Histopathology of hematoxylin and eosin-stained spleens from IKKαcKO and IKKαhet mice. Scale bar=50 μm. d, e Immunoflourescence analyses (IF) of spleen sections using MOMA-1 (green) and IgM (red) antibody. MOMA-1 stains anti-metallophilic macrophages localized at the marginal sinus. IgM stains B cells resident in splenic marginal and follicular zones. Data shown is representative of at least four experiments. Each group contained a minimum of three experimental and three control mice

The B cell specific deletion of IKKα was confirmed through western blotting performed on the bone marrow enriched B220+ B cell lysates. Results showed a complete knockout of IKKα protein expression in B220+ B cells (Fig. 1b). A flow cytometry analysis performed on the total bone marrow cells of IKKαcKO and IKKαhet littermates revealed no detectable changes in the CD3 T cells, memory T cells, NK cells and myelo-monocytes (data not shown). In addition, IKKαcKO spleens showed no indication of gross histological abnormalities in the lymphoid follicle formation except the number of total follicles counted were less and some follicles appeared constricted compared to IKKαhet control (Fig. 1c). To reveal the gross anatomical structures of MZ and FO B cell zones in the splenic sections, we used the dual immunoflourscence (IF) technique employing anti-MOMA-1/IgM antibodies. MOMA-1 reacts with anti-metallophilic macrophages that are localized at the marginal sinus forming a ring around the periarteriolar lymphocyte sheath and follicular areas at the inner side of marginal zones. The IgM antigen is found on a subpopulation of mature B cells forming splenic MZ and FO zones. The dual IF staining revealed severely reduced FO zones and marginal B cell zones in IKKαcKO. MZ zone is an IgM positive (red stained) cells forming outer rim around MOMA-1 green ring (Fig. 1d). The MZ and FO zones were normally formed in IKKαhet and wild type littermate control mice (Fig. 1d). We next examined if the MZ and FO B cells phenotype observed with total IKKα deficiency in B cells was related to the IKKα kinase inactivity in vivo. The IKKα kinase activity is essential for the p100 (NF-κB2) processing and generation of p52 subunit [29], which plays pivotal role in the NF-κB gene transcription program in B cells and controls B cell development in vivo [26, 27, 29]. Therefore, we used IKKα kinase inactive knockin mice, IKKαAA/AA. The IKKα kinase knockin mutant mice were generated by replacing Ser176 and Ser180 phosphorylation sites in the activation loop with the alanines [26, 30]. The dual IF results demonstrate reduced MZ and FO B cell zones in IKKαAA/AA. The MZ and FO B cell zones appear normally formed in the IKKαAA/+ littermate control (Fig. 1e). Taken together, these data confirm that total IKKα deficiency or the IKKα kinase inactivity in B cells disrupt the formation of MZ and FO B cell zones in vivo.

IKKα deficiency affects MZ and FO B cell growth and migration

Next, we examined the effect of IKKα deficiency on the FO and MZ B cell growth. The single cell suspensions were prepared from the splenocytes of 6–8 wk old mice and analyzed through flow cytometry. We first examined the splenic B cell population. The results revealed that splenic B cell population (B220+CD19+) were reduced on average by ~50% in IKKαcKO mice compared to IKKαhet littermate control (Fig. 2a, b). Next, we analyzed the MZ and FO B cell populations using CD23 and CD21 cell surface markers [17, 31]. Results confirmed a reduction-on average- ∿50% population of MZ B cells (CD21hiCD23lo) and FO B cells (CD21int CD23hi) in IKKαcKO compared to IKKαhet mice (Fig. 2c). The overall decrease of FO and MZ B cell population was calculated to be statistically significant (Fig. 2d). We further analyzed FO and MZ B cell population using B cell maturation markers, IgD and IgM. That allows fractionating splenic B cells into three subtypes, IgDhiIgMlo (FOI), IgDIntIgMInt (FOII) and IgMhiIgDlo (MZ). As expected, FO B cell subpopulations (FO I-II) showed a ~50% reduction in IKKαcKO compared to IKKαhet mice (Fig. 2e). The IgMhiIgDlo subpopulation represents the mature MZ B cell pool. We used CD21 marker to fractionate IgMhiIgDlo gated population into CD21lo (newly formed B cells, NF), CD21Int (follicular B cells) and CD21hi (marginal zone B cells) subpopulations [16, 31]. That revealed a ~50% reduction of CD21hi mature MZ B cell population (Fig. 2e, histograms). To understand what might be causing the reduction of FO and MZ B cell population in IKKαcKO, we analyzed recirculating mature splenic B cells (IgMhiB220+). That revealed a significant reduction of IgMhiB220+ population in IKKαcKO compared to IKKαhet (Fig. 2f).

Fig. 2.

IKKα deficiency affects MZ and FO B cell growth. a, b Flow cytometry analysis showing the percentage of splenic B cells in IKKαcKO and IKKαhet mice at 6 weeks of age. c, d Flow cytometry analysis showing the profile and percent population of MZ, marginal zone; FO, follicular B cells in the spleens of IKKαcKO and IKKαhet mice. Graph in (D) is the statistical calculation of splenic MZ and FO B cell population. Data in b, d is the mean ± S.E.M calculated from four independent experiments. Each group contained three experimental and three control mice. *p < 0.05. e Splenic B cells were prepared as in a and stained with combination of markers, IgM, IgD and CD21 to fractionate FO B cells into FO1 and FOII subpopulations, and MZ B cells. The MZ B cell population was further fractionated into CD21 high and intermediate (Int) MZ B cells populations (histogram) after gating on IgMhiIgDlo population. f Flow cytomtery profile of newly migrated B cells into spleen using IgM and B220 antibody staining. g Fetal liver cell transplant into irradiated Rag−/− mice. Flow cytometry analysis of bone marrow B cells of Rag−/− mice receiving a transplant of fetal liver cells derived from E12.5 IKKα-KO and wild type embryos. The B cells were fractionated into mature and Immature B cells after gating on CD43− cells using B220 and IgM antibody staining. The flow cytometry profile is representative of at least four experiments. Each group contained a minimum of three experimental and three control mice

To interrogate if the IKKα deletion could affect the migration of mature B cells into bone marrow follicles, we performed a fetal liver transplant into irradiated Rag−/− mice. Fetal liver cells were prepared of E13.5 total IKKα knock outs and wild type embryos and injected into Rag−/− mice. Eight weeks after the transplant, we analyzed the mature recirculating B cells in the bone marrow. Flow cytometry results confirmed a two-fold reduction in the recirculating B cells (Fig. 2g). This important piece of data allows a key conclusion: i.e., B220hi pre-B cells egress normally from bone marrow to receive maturation signals in the periphery but fail subsequently to recirculate through the bone marrow. This possibility appears much more plausible due to the normal pre-pro B to pro-B cell transition observed in Rag−/−/IKKαKO recipients comparable with the Rag−/−/IKKαWT recipient (not shown). Taken together, these data strongly support that the loss of IKKα causes significant reduction of IgDhiIgMloCD21intCD23hi follicular B cells; IgMhi IgDloCD21hiCD23lo nonrecirculating marginal zone B cells, and that the recirculation of IgMhiB220+ mature B cells through the bone marrow is severely disrupted.

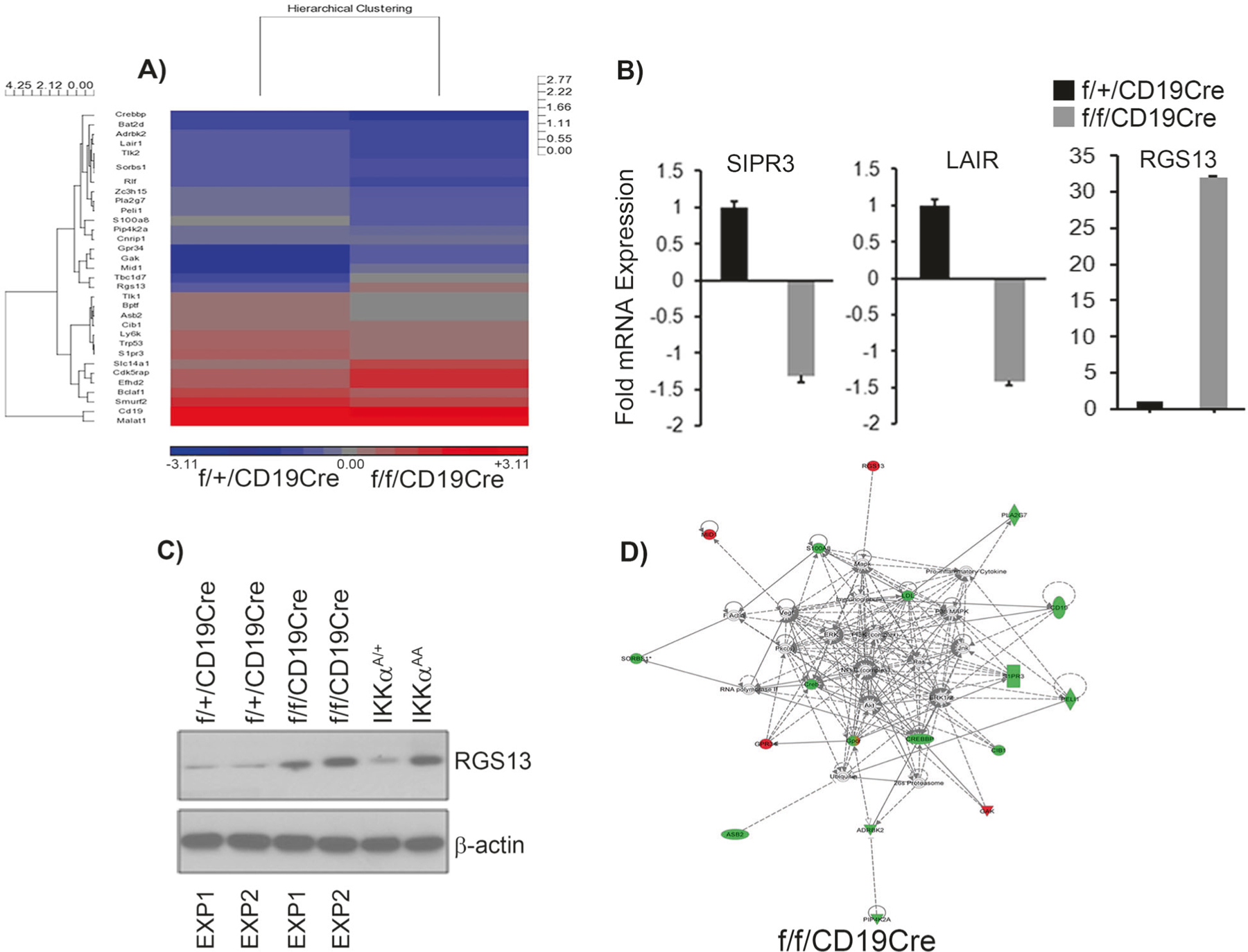

Gene expression profile of IKKαKO mature B cells in vivo

The FO and MZ B cell differentiation, migration, and retention in the periphery is tightly regulated transcriptional process, the role of several genes in these processes have already been elucidated [32]. To examine in-depth how IKKα deletion in B cells affect FO and MZ B cell differentiation and migration, we performed a cDNA microarray analysis on the splenic mature B cell pool, IgMhiB220+ (Fig. 2f). These B cells are new migrants to spleen [33]. And have the potential to recirculate through bone marrow (Fig. 2g).

RNA was prepared from the FACS-sorted B220+IgMhi B cells isolated from the spleens of 6–8 wk old IKKαcKO and IKKαhet mice and subjected to cDNA microarray analysis. A threshold of ≥1.8-fold in the differential gene expression was derived at from the one-way ANOVA analysis. Out of 105, we carefully selected 32 differentially regulated genes by an estimated 1.8-fold expression change and due to their role-based on the available literature- in B cell functions including MZ and FO B cell differentiation, maturation and migration. We selected these 32 genes for hierarchical clustering and heat map analysis (Fig. 3a). The CREB binding protein (CREBBP), which is downregulated in IKKαcKO mice, was identified to be a major gene cluster. The CREBBP is involved in transcriptional coactivation of many different transcription factors [34]. Other important members of this cluster include leukocyte-associated Ig-like receptor 1 (LAIR1) and adrenergic receptor kinase beta 2 (ADRBK2). The second most important gene cluster identified to be downregulated in IKKαcKO included among others the G-protein coupled receptors (GPCR), sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 3 (SIPR3) and proapoptotic, TP53. The gene cluster identified by the hierarchical clustering to be upregulated was represented by the G protein family members that included among others the G protein-coupled receptor 34; regulator of G-protein signaling 13 (RGS13) and cyclin G associated kinase (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

Gene expression profile of IKKαcKO B cells. The mature recirculating IgMhiB220+ B cells were sorted from splenic IKKαcKO and IKKαhet control mice and subjected to microarray analysis. We used three experimental replicates. a Shows the hierarchical clustering and heat map generated of the 32 genes that show 1.8-fold change in their expression after normalization. The red and blue indicate upregulated and downregulated genes, respectively. Standardized intensity is indicated. b The RNA was extracted from the sorted splenic IgMhiB220+ population and subjected to qRT-PCR analysis to validate the expression of LAIR1, SIPR3 and RGS13 expression. Fold values were normalized with GAPDH. Data in b is the ± S.E.M., calculated from a minimum of three independent experiments. Four technical replicates were made from each experimental group. Each experimental replicate contains pooled RNA of three mice. c Western for RGS13 expression. Protein lysate was prepared from sorted splenic IgMhiB220+ population and subjected to western analysis. Each experiment contains protein lysate made from a group of three mice. d Ingenuity pathway analysis. The 32 differentially regulated genes by at least 1.8-fold identified from the microarray analysis and after normalization of gene expression values were uploaded into the ingenuity knowledge database. The software predicts the networks based on the gene expression products and their functions reported in the literature. Green shapes represent the downregulated genes while the red color shapes represent the upregulated genes. NF-κB pathway among the others is shown to be a major node in the network to be deregulated with IKK alpha deletion

We selected three most important genes, SIPR3, LAIR, and RGS13 for validation of microarray data as their validation would implicate IKKα for the first in the B cell migration. We performed a qRT-PCR analysis on the FACS-sorted (B220 + IgMhi) B cells that confirmed the downregulated expression of SIPR3 and LAIR1 and upregulation of RGS13 in IKKαcKO compared to IKKαhet control (Fig. 3b). RGS13 enhances GTPase activity of G-protein α subunits thereby rendering them inactive and negatively control G-protein signaling [35], and may impedes B cell migration [36, 37]. Therefore, we performed a western to detect RGS13 protein using cell lysates obtained from the FACS-sorted (B220+IgMhi) cells. The RGS13 showed a consistent pattern of upregulated expression in IKKαcKO and in kinase inactive IKKαAA mice, where as its expression remain very low in IKKαhet littermate control mice (Fig. 3c). These data indicate that IKKα loss in mature B cells enhances aberrant RGS13 GTPase activity.

Next, we used ingenuity pathway analysis software program to analyze the gene regulatory networks perturbed in B cells lacking IKKα. We uploaded in the ingenuity pathway finder program the 32 genes identified to be differentially regulated in IKKαKO B220+IgMhi cells. These 32 genes were originally selected for hierarchical clustering and heat map analysis (Fig. 3a). Ingenuity pathway analysis predicted among the others the NF-κB signaling pathway to be most relevant in MZ and FO B cell phenotype and predictably perturbed due to IKKα deletion in vivo (Fig. 3d). The other genes predicted to be affected include the ones associated with the lymphocyte cellular movement, immune cell trafficking and cell to cell signaling. The shapes with green color and red color in the Fig. 3d represent the genes identified as downregulated and upregulated targets respectively.

Discussion

In the current study, we investigated the role of IKKα in the MZ and FO B cell differentiation by generating the mice in which IKKα was deleted from pro-B cell lineage. Utilizing the high throughput gene array analysis we revealed novel set of genes important for the MZ and FO B cell differentiation and migration. Furthermore, to explore the protein interactions networks that potentially perturbs with IKKα deletion, we performed an in-silico Ingenuity pathway analysis on the genes that showed significant changes in expression. That predicted prosurvival NF-κB pathway to be one of the major gene regulating networks to be associated with the MZ and FO B cell differentiation (Fig. 3d). The potential loss of prosurvival NF-κB functions due to absence of IKKα kinase activity and its other functions unrelated to its kinase activity in B cell lineage could explain the reduction of the MZ and FO B cells observed in vivo in IKKαcKO.

The conditional genetic deletion of various components of NF-κB signaling pathway, both classical and non-classical, produces variable defects in MZ and FO B cell zones some resembling closely with that of IKKαcKO phenotype. For example, the conditional deletion of Rel A, cRel and p50 subunits affect the differentiation of MZ B cells only [18]. Whereas, the components of non-canonical NF-κB pathway, BAFF-R, p100, and Rel B/p52 genetic deletion causes defect in the MZ and FO B cell development [38–42], which is similar to what we report here for IKKαcKO. Furthermore, the B cell activating factor (BAFF) deficient mice lack both MZ and FO B cells [33, 43]. The BAFF binds with BAFF-R and signals through NIK→IKKα→-p100→RelB/p52. Therefore, the genes implicated with MZ and FO B cell phenotype in IKKαKO B cells (Fig. 3a) may well be regulated through NIK→IKKα→p100→RelB/p52 pathway.

Another important finding in our gene array and pathway analysis was the B cell coreceptor CD19 molecule that showed downregulated expression in the splenic B cells of IKKαcKO (Fig. 3a, d). The IKKαcKO phenotype resembles with the CD19−/− mice in many respects including reduced number of peripheral B cells, MZ and FO B cell numbers, and perturbed splenic MZ and FO B cell architecture [44, 45]. A possible explanation for the similarities in phenotype could be that the downregulated expression of CD19 in IKKαcKO B cells dampens BCR signaling that might accentuate B cell survival signals enhancing the apoptosis of peripheral B cells leading to the reduced number of MZ and FO B cells. Interestingly, in the kinase dead knockin mice we did not observe significant apoptosis of B cells in the periphery indicating that total IKKα loss in B cells generates a distinct biological response.

Our investigation also demonstrated an unexpected role of IKKα in B cell homing and recirculation. The role of G protein family members and G protein-coupled receptor signaling has emerged as a prominent feature for MZ and FO B cell retention and recirculation. Our gene array analysis revealed several such genes changing expression with IKKα deletion. One such G protein family member which we validated to be significantly downregulated in IKKαcKO is sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 3 (SIPR3). Several reports have implicated sphingosine-1-phosphate (SIP) lipid signaling through G protein-coupled receptors (Gαi), SIPR1 and SIPR3, important for the positioning of MZ B cells [19, 46, 47]. Considering those reports, the loss of SIPR3 mediated signaling in IKKαcKO mice is expected to lead to the loss of MZ B cell retention. Likewise, GTPase activating proteins (GAPs) are essential for controlling G protein receptor signaling. One such GAP that we validated to be upregulated in IKKαcKO and IKKαAA mice is RGS13 (Fig. 3b, c). RGS13 enhances GTPase activity of G-protein α subunits thereby rendering them inactive and, thus, negatively control the G-protein signaling [35]. RGS13 has been reported to express in GC B cells and reduce the migration of B cells in response to chemokines [36, 37]. Therefore, a predicted role for RGS13 could be in B cell migration. Its upregulated expression in mature IKKαcKO B cells would indicate enhanced GTPase activity thereby impeding migration of mature B cells into BM follicles. How IKKα regulates RGS13 expression needs further investigation. Another link that establishes connection between IKKα role and G protein signaling is the cannabinoid receptor interacting protein 1 (Cnrip1). The Cnrip1 was identified to be a downregulated target in our gene array analysis (Fig. 3a). Cnrip1 interacts with G-protein coupled cannabinoid receptor (CB1) [48, 49]. How the lack of Cnrip1 and its interaction with CB1 alters B cell migration or retention needs further exploration. Another interesting gene that we validated to be downregulated in mature B cells with IKKα deletion was LAIR1 [50]. LAIR1 belongs to the leukocyte-associated inhibitory receptor family and its intracellular immunoreceptor tyrosine inhibitory motif (ITIM) serves docking site for tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 [51]. LAIR1 has been demonstrated to function as a negative regulator of BCR signaling [52]. Therefore, its lower expression in IKKαcKO B cells might have severely disturbed BCR-mediated signaling strength affecting naïve B cells B survival and differentiation into MZ and FO B cell lineage. How exactly IKKα regulate LAIR1 expression and its precise role in MZ and FO B cell lineage decision would need in depth investigation.

Methods

Mice

Mice carrying the IKKα floxed allele (IKKαf/f); a Cre driven by CD19 (CD19-Cre) and Rag1−/− were purchased from Jackson laboratories [53]. Mice strains, IKKαf/fCD19-Cre and littermate control IKKαf/+CD19-Cre were generated through crosses. We also used IKKαAA/AA mice, which is kinase inactive knockin mutant strain as described previously [26, 30]. All the mice used in this study were cared for in accordance with the guideline of our institution’s Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol: 08–074 and 08–075). All animals were housed and bred in a specific pathogen-free animal facility at National Cancer Institute at Frederick, Maryland, USA. The heterozygous CD19-Cre mice were used in all the experiments. Genotypes were determined by PCR using tail DNA.

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used for flow cytometry: PE-Cy7-, APC/Cy7-, PE, APC-, Alexa 450- and FITC- labeled antibodies against B220 (RA3–6B2), CD19 (MB19–1), CD43 (eBioR2/60), IgM (II/41), IgD (11–26c, 11–26), CD23 (B3B4), CD21/CD35 (4E3), CD93/AA4.1 (AA4.1) and PE-conjugated rat IgG2a (eBP2a). All these antibodies were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). For western blotting, we used the following antibodies, IKKα (cat. IMG-136A; Imgenex), RGS13 (cat. PA529842, Thermoscientific) and β-actin (cat. 4970S, Cell Signaling).

Flow cytometry analyses

The bone marrow was harvested from the tibias and femurs of 6 to 8-week-old mice. The red blood cells (RBCs) were lysed in ACK lysing buffer (A10492, Gibco). After thorough washings cells were suspended in MACS buffer and incubated in mouse CD45R (B220) micro beads (cat. 130–049-501, Milteny Biotec, San Diego, CA) for 30 min. B220+ cells were enriched through positive selection method using LS columns (130–042-401) on MACS separation unit (MACS). Likewise, spleens were harvested from 6 to 8-week-old mice and cleared of red blood cells. The single-cell suspensions were stained, and acquisitions were performed on multicolor BD LSR II cell analyzer (BD Biosciences). Flow cytometry analyses were performed with Flow Jo software using the lymphocyte gates.

qRT-PCR

Total RNA was prepared from sorted (B220+IgMhi) cells using the Trizol Reagent (Gibco-BRL, Life Technologies). Reverse transcription reactions were performed using M-MuLV reverse transcriptase (cat. M0253L, New England Biolabs) followed by qPCR amplification reactions using iTaq™ SYBR GREEN supermix with ROX (cat. 172–5121, Bio-Rad Laboratories). The following primers were used for the qPCR: sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 3 (S1PR3), forward-5′-TGGCCAGCAAAGAGATG-AGG-3′, reverse-5-′ TGCAGGAAGAAGTAGCCACG-3′; leukocyte-associated Ig-like receptor 1 (Lair1), forward-5′-AGGGGATTACCTGGTCCGAA-3′, reverse-5′- GCGGA-AAGACAAAGGAGGA-3′. RGS13, forward-5′-GGG-GCAGAATTTCTAGGGCA-3′, reverse-5′-TGAGTGGG-TTCACGAATGCT-3′. The gene amplification analysis was performed with StepOnePlus real time PCR (Applied Biosystems). The fold changes were calculated using the comparative delta ct (ΔΔct) method. We used the following formula: ΔΔct = Δct Target (Gene) – Δct Calibrator (GAPDH). The fold expression was calculated using the formula: Fold Change = 2− ΔΔct

Histopathology, immunofluorescence and western blotting

The histopathological examination of spleens of the experimental and control mice. Harvested organs were fixed with the 10% buffered formalin (cat. 23–245-685, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). Next day, the fixed organs were transferred into 70% ethanol. Organs were processed for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining at the NCI-Frederick Histotechnology core laboratory (http://web.ncifcrf.gov/rtp/lasp/phl/immuno/). Immunofluorescence (IF) was performed on the fresh frozen spleen tissues sectioned on cryostat (Leica) following standard protocol. Mounted sections were fixed with methanol at −20 °C for 5 min. Sections were permeabilized with 0.25% Triton-X-100 for 20 min, and then blocked with 2% normal horse serum in PBS for 20 min. Sections were incubated overnight for dual immunofluorescence to detect MZ and FO zones using a cocktail of primary antisera of MOMA-1 (cat. AB51814, abcam) and IgM (cat. NBP2–34253, Novus Biologicals). Subsequent detections were performed with a mixture of secondary antibodies consisting of Red fluorochrome Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-Rat IgG (Jackson Immunoresearch, 1:200) and green fluorochrome Alexa 488-conjugated donkey anti-Rabbit IgG (Jackson). Images were captured with a Carl Zeiss Axioskop fluorescence microscope (Axioskop 40; Carl Zeiss Inc.)

SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis. Protein lysates were prepared from sorted (B220+IgMhi) B cells using the RIPA lysis buffer supplemented with protein and phosphates inhibitor cocktails. A 40−50 µg of proteins was resolved on 8 or 10% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitro-cellulose or PVDF membranes (Millipore). Membranes were blocked for 1 h at RT in TBS-T buffer containing 5% non-fat dry skim milk powder and 0.1% Tween-20, followed by overnight incubation in primary antibody. Next day, membranes were incubated for 1 h at RT with HRP-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG antibody (cat. no. NA9310 and NA9340; GE Healthcare Biosciences). The HyBlot CL autoradiograpgy films (cat. E3018, Denville Scientific) were used for chemiluminescence detection. An enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagent, Western Lightning Plus was purchased from PerkinElmer (Cat. NEL103001EA). The PVDF membranes were stripped using a stripping solution (cat. no. 21059, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Fetal liver transplant

Fetal liver transplant was performed on two-month-old Rag−/− mice that were γ-irradiated (3 Gy). After irradiation mice were maintained on antibiotics by supplementing the water with amoxicillin according to standardized experimental protocol and as described previously [24, 54]. Fetal livers were harvested from 13.5-day old IKKα-KO and WT embryos. Single-cell suspensions were prepared, and 1 × 106 fetal liver cell were intravenously injected into Rag−/− mice. Bone marrow was harvested from the recipient Rag−/− mice 8 weeks post-transplant and analyzed through flow cytometry.

Microarray analyses

cDNA Microarray analysis was performed on the RNA extracted from the (B220+IgMhi) sorted population of B cells using the cell sorting core facility of Cancer and Inflammation Program in National Cancer Institute, Frederick. The (B220+IgMhi) cells were sorted from the single cell suspension prepared from the spleens of 6–8 week-old IKKαf/fCD19-Cre and littermate control mice. An Affymetrix mouse 430 2.0 array chip, containing 45,000 genes, was used to generate microarray data. The microarray data including ANOVA analysis for differential gene expression, heat map analysis, and hierarchical clustering were performed at the microarray and bioinformatics core facility of Laboratory of Molecular Technology, SAIC-Frederick. A total of 32 genes that show 1.8-fold expression changes in ANOVA analysis were used to generate heat map and the hierarchical clustering, and to generate the gene interaction network through Ingenuity Pathway analysis software (Qiagen).

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Allman D, Lindsley RC, DeMuth W, Rudd K, Shinton SA, Hardy RR. Resolution of three nonproliferative immature splenic B cell subsets reveals multiple selection points during peripheral B cell maturation. J Immunol. 2001;167:6834–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loder F, Mutschler B, Ray RJ, Paige CJ, Sideras P, Torres R, et al. B cell development in the spleen takes place in discrete steps and is determined by the quality of B cell receptor-derived signals. J Exp Med 1999;190:75–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tiegs SL, Russell DM, Nemazee D. Receptor editing in self-reactive bone marrow B cells. J Exp Med 1993;177:1009–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rolink AG, Andersson J, Melchers F. Characterization of immature B cells by a novel monoclonal antibody, by turnover and by mitogen reactivity. Eur J Immunol 1998;28:3738–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pillai S, Cariappa A. The follicular versus marginal zone B lymphocyte cell fate decision. Nat Rev Immunol 2009;9:767–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kraal G Cells in the marginal zone of the spleen. Int Rev Cytol 1992;132:31–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pillai S, Cariappa A, Moran ST. Marginal zone B cells. Annu Rev Immunol 2005;23:161–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin F, Kearney JF. Marginal-zone B cells. Nat Rev Immunol 2002;2:323–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balazs M, Martin F, Zhou T, Kearney J. Blood dendritic cells interact with splenic marginal zone B cells to initiate T-independent immune responses. Immunity 2002;17:341–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin F, Oliver AM, Kearney JF. Marginal zone and B1 B cells unite in the early response against T-independent blood-borne particulate antigens. Immunity 2001;14:617–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He B, Santamaria R, Xu W, Cols M, Chen K, Puga I, et al. The transmembrane activator TACI triggers immunoglobulin class switching by activating B cells through the adaptor MyD88. Nat Immunol 2010;11:836–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cariappa A, Boboila C, Moran ST, Liu H, Shi HN, Pillai S. The recirculating B cell pool contains two functionally distinct, long-lived, posttransitional, follicular B cell populations. J Immunol 2007;179:2270–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leadbetter EA, Brigl M, Illarionov P, Cohen N, Luteran MC, Pillai S, et al. NK T cells provide lipid antigen-specific cognate help for B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008;105:8339–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wen L, Brill-Dashoff J, Shinton SA, Asano M, Hardy RR, Hayakawa K. Evidence of marginal-zone B cell-positive selection in spleen. Immunity 2005;23:297–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baker N, Ehrenstein MR. Cutting edge: selection of B lymphocyte subsets is regulated by natural IgM. J Immunol 2002;169:6686–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cariappa A, Tang M, Parng C, Nebelitskiy E, Carroll M, Georgopoulos K, et al. The follicular versus marginal zone B lymphocyte cell fate decision is regulated by Aiolos, Btk, and CD21. Immunity 2001;14:603–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin F, Kearney JF. Positive selection from newly formed to marginal zone B cells depends on the rate of clonal production, CD19, and btk. Immunity 2000;12:39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cariappa A, Liou HC, Horwitz BH, Pillai S. Nuclear factor kappa B is required for the development of marginal zone B lymphcytes. J Exp Med 2000;192:1175–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guinamard R, Okigaki M, Schlessinger J, Ravetch JV. Absence of marginal zone B cells in Pyk-2-deficient mice defines their role in the humoral response. Nat Immunol 2000;1:31–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hozumi K, Negishi N, Suzuki D, Abe N, Sotomaru Y, Tamaoki N, et al. Delta-like 1 is necessary for the generation of marginal zone B cells but not T cells in vivo. Nat Immunol 2004;5:638–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saito T, Chiba S, Ichikawa M, Kunisato A, Asai T, Shimizu K, et al. Notch2 is preferentially expressed in mature B cells and indispensable for marginal zone B lineage development. Immunity 2003;18:675–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Becker-Herman S, Lantner F, Shachar I. Id2 negatively regulates B cell differentiation in the spleen. J Immunol 2002;168:5507–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feng J, Wang H, Shin DM, Masiuk M, Qi CF, Morse HC 3rd. IFN regulatory factor 8 restricts the size of the marginal zone and follicular B cell pools. J Immunol 2011;186:1458–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balkhi MY, Willette-Brown J, Zhu F, Chen Z, Liu S, Guttridge DC, et al. IKKalpha-mediated signaling circuitry regulates early B lymphopoiesis during hematopoiesis. Blood 2012;119:5467–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu F, Xia X, Liu B, Shen J, Hu Y, Person M. IKKalpha shields 14–3-3sigma, a G(2)/M cell cycle checkpoint gene, from hypermethylation, preventing its silencing. Mol Cell 2007;27:214–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Senftleben U, Cao Y, Xiao G, Greten FR, Krahn G, Bonizzi G, et al. Activation by IKKalpha of a second, evolutionary conserved, NF-kappa B signaling pathway. Science 2001;293:1495–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaisho T, Takeda K, Tsujimura T, Kawai T, Nomura F, Terada N, et al. IkappaB kinase alpha is essential for mature B cell development and function. J Exp Med 2001;193:417–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jellusova J, Miletic AV, Cato MH, Lin WW, Hu Y, Bishop GA, et al. Context-specific BAFF-R signaling by the NF-kappaB and PI3K pathways. Cell Rep 2013;5:1022–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghosh S, Karin M. Missing pieces in the NF-kappaB puzzle. Cell 2002;109:S81–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cao Y, Bonizzi G, Seagroves TN, Greten FR, Johnson R, Schmidt EV, et al. IKKalpha provides an essential link between RANK signaling and cyclin D1 expression during mammary gland development. Cell 2001;107:763–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oliver AM, Martin F, Gartland GL, Carter RH, Kearney JF. Marginal zone B cells exhibit unique activation, proliferative and immunoglobulin secretory responses. Eur J Immunol 1997;27:2366–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hardy RR, Hayakawa K. B cell development pathways. Annu Rev Immunol 2001;19:595–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schiemann B, Gommerman JL, Vora K, Cachero TG, Shulga-Morskaya S, Dobles M, et al. An essential role for BAFF in the normal development of B cells through a BCMA-independent pathway. Science 2001;293:2111–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chrivia JC, Kwok RP, Lamb N, Hagiwara M, Montminy MR, Goodman RH. Phosphorylated CREB binds specifically to the nuclear protein CBP. Nature 1993;365:855–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson EN, Druey KM. Functional characterization of the G protein regulator RGS13. J Biol Chem 2002;277:16768–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hwang IY, Hwang KS, Park C, Harrison KA, Kehrl JH. Rgs13 constrains early B cell responses and limits germinal center sizes. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e60139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shi GX, Harrison K, Wilson GL, Moratz C, Kehrl JH. RGS13 regulates germinal center B lymphocytes responsiveness to CXC chemokine ligand (CXCL)12 and CXCL13. J Immunol 2002;169:2507–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amanna IJ, Dingwall JP, Hayes CE. Enforced bcl-xL gene expression restored splenic B lymphocyte development in BAFF-R mutant mice. J Immunol 2003;170:4593–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weih DS, Yilmaz ZB, Weih F. Essential role of RelB in germinal center and marginal zone formation and proper expression of homing chemokines. J Immunol 2001;167:1909–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weih F, Caamano J. Regulation of secondary lymphoid organ development by the nuclear factor-kappaB signal transduction pathway. Immunol Rev 2003;195:91–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guo F, Weih D, Meier E, Weih F. Constitutive alternative NF-kappaB signaling promotes marginal zone B-cell development but disrupts the marginal sinus and induces HEV-like structures in the spleen. Blood 2007;110:2381–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guo F, Tanzer S, Busslinger M, Weih F. Lack of nuclear factor-kappa B2/p100 causes a RelB-dependent block in early B lymphopoiesis. Blood 2008;112:551–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gross JA, Dillon SR, Mudri S, Johnston J, Littau A, Roque R, et al. TACI-Ig neutralizes molecules critical for B cell development and autoimmune disease. Impaired B cell maturation in mice lacking BLyS. Immunity 2001;15:289–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Engel P, Zhou LJ, Ord DC, Sato S, Koller B, Tedder TF. Abnormal B lymphocyte development, activation, and differentiation in mice that lack or overexpress the CD19 signal transduction molecule. Immunity 1995;3:39–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Otero DC, Rickert RC. CD19 function in early and late B cell development. II. CD19 Facil pro-B/pre-B Transition. J Immunol 2003;171:5921–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cinamon G, Zachariah MA, Lam OM, Foss FW Jr., Cyster JG. Follicular shuttling of marginal zone B cells facilitates antigen transport. Nat Immunol 2008;9:54–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cinamon G, Matloubian M, Lesneski MJ, Xu Y, Low C, Lu T, et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 promotes B cell localization in the splenic marginal zone. Nat Immunol 2004;5:713–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Niehaus JL, Liu Y, Wallis KT, Egertova M, Bhartur SG, Mukhopadhyay S, et al. CB1 cannabinoid receptor activity is modulated by the cannabinoid receptor interacting protein CRIP 1a. Mol Pharmacol 2007;72:1557–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abood ME. Molecular biology of cannabinoid receptors. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2005;168:81–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meyaard L, Adema GJ, Chang C, Woollatt E, Sutherland GR, Lanier LL, et al. LAIR-1, a novel inhibitory receptor expressed on human mononuclear leukocytes. Immunity 1997;7:283–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu M, Zhao R, Zhao ZJ. Identification and characterization of leukocyte-associated Ig-like receptor-1 as a major anchor protein of tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 in hematopoietic cells. J Biol Chem 2000;275:17440–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van der Vuurst de Vries AR, Clevers H, Logtenberg T, Meyaard L. Leukocyte-associated immunoglobulin-like receptor-1 (LAIR-1) is differentially expressed during human B cell differentiation and inhibits B cell receptor-mediated signaling. Eur J Immunol 1999;29:3160–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rickert RC, Roes J, Rajewsky K. B lymphocyte-specific, Cre-mediated mutagenesis in mice. Nucleic Acids Res 1997;25:1317–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sanyal M, Fernandez R, Levy S. Enhanced B cell activation in the absence of CD81. Int Immunol 2009;21:1225–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]