Abstract

Veterinary Professions Advising Center (VetPAC) is a unique undergraduate advising center that combines Career Center services with preprofessional advising for preveterinary students at North Carolina State University (NCSU). During the past 10 years, VetPAC has created five distinct internships, three annual study abroad courses, and a competitive annual high school summer camp, provided holistic advising, and hosted large-scale advising events that consistently provide resources to more than 800 students annually. The VetPAC provided outreach to an average of 13 local high schools per academic year and educated over 300 visiting students about VetPAC and preveterinary life at NCSU since 2015. NCSU College of Veterinary Medicine has had a minimum of 26% and a maximum of 45% DVM students in the incoming classes who accessed VetPAC resources and advising. This article presents the impact VetPAC has had on preveterinary student success at NCSU and provides an outline of VetPAC’s first 10 years of development as a model of combined career services and preprofessional advising for peer institutions.

Keywords: animal science advising, Career Center, experiential learning, holistic advising program, preprofessional advising, preveterinary program development

INTRODUCTION

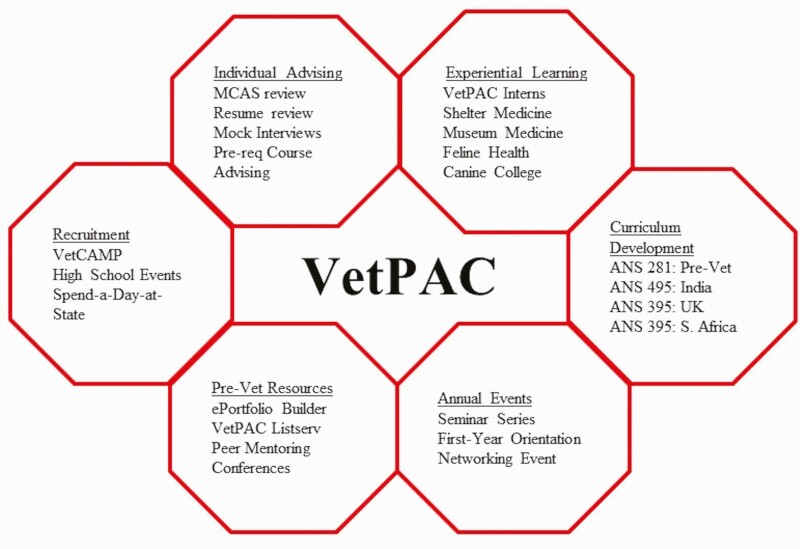

Based on the admissions records from 2015 to 2020, the Animal Science Department at North Carolina State University’s (NCSU) average first-year class consists of 127 (77%) preveterinary track students enrolled in the Veterinary BioScience concentration, compared with the Science or Industry concentrations in the Animal Science major. The majority of preveterinary students choose to attend NCSU with the expectation that it will increase their chances of attending the College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM) at NCSU. Increased enrollment of students in the Animal Science Department whose primary interest is in preveterinary medicine is consistent with and a continuation of previously reported demographics (Taylor and Kauffman, 1983; Buchannan, 2008). Buchannan (2008) proposed that Department of Animal Science should establish recruitment programs that reach out to new populations of students from urban backgrounds with interest in companion and exotic animals, adapt curriculum for differing career aspirations, and provide students more opportunities for international experience. To recruit, mentor, and provide hands-on opportunities for the Department of Animal Science students and students from any major at the university, the Veterinary Professions Advising Center (VetPAC) was founded in the department 10 years ago. It remains the only exclusive preveterinary advising center at a Land-Grant Institution. It is led by a faculty member serving as the Program Director who created a strategic multifaceted approach to provide advising, experiential, educational, and networking opportunities as outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

VetPAC Beehive. VetPAC: a multifaceted approach to Pre-Veterinary Advising in Animal Science.

The Center strives to provide holistic advising through (a) individual appointments with the Director; (b) large-scale group advising through first-year orientation, annual networking, and career exploration events; (c) experiential learning activities through community partnerships; (d) curriculum development that focusses on skill acquisition as well as career planning; and (e) local and national outreach to provide an early start to preveterinary students. The objective of this paper is to provide an outline of VetPAC’s development as a model for peer institutions and to review the impact VetPAC has had on preveterinary student success at NCSU. The authors define success as a combination of preveterinary student engagement with Center resources and by the number of VetPAC advisees that achieve admission into a veterinary program.

It is important to note that while the term “preveterinary” is used to describe students in this paper, it is not an official term, major, minor, or concentration recognized by NCSU. VetPAC services are available to all students interested in pursuing a career in veterinary medicine regardless of major. For this study, the authors utilize the numbers available through the student engagement in a variety of programs, events, and academic courses.

Literature Review

According to Garis (2014), the hallmark of an effective Career Center is a mix of both centralized and decentralized career experiences that effectively assist students in exploring and making career decisions. Career Centers are intended to help students address professional identity, distinguish next steps for their careers, offer opportunities to explore multiple paths within occupations, aid in resume and interview skill building, and assist in discerning whether a career path suits the individual student (Lehker and Furlong, 2006; Schaub, 2012; Garis, 2014). Preprofessional advising provides students specialized knowledge related to pursuing careers within a narrower field of study such as law or medicine and focusses on preparing students to become competitive applicants for postsecondary programs (Richardson, 2013; Knotts and Wofford, 2017). Integrating career exploration with preprofessional advising assists students with searching for experiential opportunities, relevant course planning, and preparing for the admissions application process (Knotts and Wofford, 2017; Lynch and Lungrin, 2018). However, preprofessional advising does not always encourage students to ask whether the intended career path fits their individual needs causing first-year graduate students to investigate career fit during their postsecondary program (Lehker and Furlong, 2006).

The eligibility criterion for gaining admission into a Doctor of Veterinary Medicine (DVM) program is broadly based on acquiring substantial experiential hours, maintaining high academic performance, and engaging in activities relevant to various fields within veterinary medicine (Kogan and McConnell, 2001; Hudson et al., 2009; Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges, 2020). In addition to these general criteria, there is diversity between each of the CVM in the United States for course requirements and the number of experience hours required (Pelzer, 2018). These distinct criteria for a DVM program require preveterinary advising to be a combination of both career counseling and preprofessional advising.

PROGRAM OVERVIEW AND STRUCTURE

Program Management

To establish and lead VetPAC, a faculty member, veterinarian and PhD in Immunology, provides an active role in the administration and programmatic development. In addition to her roles as VetPAC Director, teaching faculty, and academic advisor, she also provides mentorship to several graduate research assistants, graduate and undergraduate teaching assistants, honors students, and all preveterinary students who seek the Director’s expertise. The Director offers appointments for one-on-one advising, review of student applications for the online DVM application system, personal statement revision, DVM admissions interview practice, and career mapping consultation. In a study completed at CVM Ohio State University in 2013, Lord and co-workers identified DVM students’ requested needs for improving soft skills such as interviewing, communication skills, tutoring, and general wellness. Therefore, the VetPAC Director strives to ensure consistent year-round programming, amenable appointment hours, need-based course development, and strategic yet sustainable internship program development.

The Center is also staffed with a Program Associate, a staff member with an MA in Clinical Mental Health Counseling and a background in Student Affairs, who aids the Director in overseeing the business aspects of VetPAC. The Program Associate’s main duties include supervising the VetPAC interns and work-study students, managing the office tasks, updating and maintaining the program website, communicating with prospective NCSU families, and the coordination of all annual events and high school summer camp. Funding for VetPAC is provided by the university through the Department of Animal Science, private donors, and invested stakeholders. Additional funding is attained through camp revenue and fundraising done by the VetPAC interns for the annual veterinary summer camp and conference attendance, respectively.

VetPAC Interns

Each academic year, VetPAC selects 12–16 preveterinary students through a competitive application process for a leadership internship that focusses on building communication skills, teamwork, administrative skills, and establishing new networks for the Center. Criteria for selection of the interns include having a GPA of 3.3 or above, a minimum academic standing of second-year undergraduate student, and consistent demonstration of animal and veterinary shadowing and leadership experiences. Interns participate in a one-day orientation to the internship prior to the start of classes and then spend their first month training under two former VetPAC interns who serve as mentors to teach the day-to-day operations of the Center. The interns assist with planning events for NCSU preveterinary students such as the Fall Seminar Series, First-Year Preveterinary Orientation, and VetPAC’s Annual Networking Event. In addition to hosting these events for other students, interns have the opportunity to attend one state and one national conference with financial assistance from VetPAC. The interns build their communication skills by staffing the advising center during the academic year along with hosting two peer mentor hours each week. This responsibility encourages interns to become up-to-date with the admissions procedures, criteria, and CVM options presented to their preveterinary peers. Research shows that the opportunity to practice leadership skills and the cultivation of professional connections serve to develop students’ confidence in their career choice and that the development of soft skills cultivated during a leadership internship contributes to an increased likelihood of employment and postsecondary admissions acceptance (Foli et al., 2014; Pohl and Butler, 1994). In addition, research supports that undergraduate preprofessional students engaged in leadership positions are more likely to attain higher occupational outcomes than peers who do not (Jones et al., 2014). Specific to the veterinary profession, early building of communication and leadership skills are important aspects of preveterinary professional development as these skills are necessary to improve the profession and to improve client–provider satisfaction (McDermott et al., 2015; Grevemeyer et al., 2016).

Student Advising

Since 2010, the VetPAC Director has hosted more than 3,300 individual advising appointments to address student concerns including internship and research recommendations, academic course planning, evaluating career fit, reviewing resumes, critiquing Veterinary Medical College Application Service (VMCAS) applications, and offering mock DVM interviews. To maintain privacy and the confidentiality of each applicant’s VMCAS application, current VMCAS applicants seeking to review their application drafts are required to bring their personal laptops to use to log in during individual advising appointments with the VetPAC Director. The Center utilizes an electronic calendar to allow students the ability to make advising appointments, which has encountered steady growth with an overall average of 85 users per year who attend an average of 124 preveterinary focussed advising appointments per year.

The VetPAC website (https://cals.ncsu.edu/vetpac/) offers an electronic portfolio builder to assist students with categorizing and documenting their animal, veterinary, research, extra-curricular, and work experiences for the VMCAS. This is important as students are able to catalog hours from as early as their high school experiences. The online VetPAC portfolio builder allows students a secure platform to record their information for efficient transfer of all of their accomplishments from high school onwards into their VMCAS application at the time of application. Furthermore, VetPAC’s website maintains an extensive listing of local and global opportunities for shadowing and internships so students can search for the type of experience for diversifying their portfolio. In 2020, VetPAC’s website received an average of 149 hits per day.

Students, university staff, and alumni also have the opportunity to subscribe to an email listserv through the VetPAC website. This listserv provides updates on VetPAC events, preveterinary resources, and relevant experiential opportunities. Since 2013, the center has averaged 793 subscribers to listserv per year.

Annual Events

Three annual events were created to assist with the dissemination of general advising information for incoming students (the First Year Preveterinary Student Orientation), discussing hot topics in veterinary medicine (the Fall Seminar Series), and connecting students with local shadowing opportunities (the Annual Networking Event). The purpose of the annual Preveterinary First-Year Orientation is to introduce incoming first-year students to preveterinary specific resources available within the first month of their Fall academic term. The event includes an orientation lecture by the Director, smaller workshops by career professionals, and a meet and greet with current VMCAS applicants and current DVM students. This program is designed to introduce a variety of preveterinary resources available to students at NCSU.

The Center hosts a series of 5–6 seminars that is open to NCSU preveterinary students each Fall. The seminar series explores a themed topic relevant to the field of veterinary medicine including veterinary specialties, internship opportunities, study abroad courses, career options, and paraprofessional career choices that are available. Past themes of the Fall Seminar Series have included “Where do Veterinarians Work?” which invited veterinarians from a variety of fields including a veterinary diagnostician, a forensic veterinarian, a mixed-practice veterinarian, a military veterinarian, and a small animal practice owner. Other themes have included a “How-to” series that provided students with the skills to find research experiences, interview at veterinary clinics, promote themselves through social media, and attain scholarships within the university. Session topics for replica Seminar Series should include local community partners, internship opportunities, and current topics related to veterinary medicine. This approach offers seminar series participants the opportunity to network and learn more about opportunities available to them and continues to expand VetPAC’s connections with the local community (Schaub, 2012; Garis, 2014). Over 50 different community partners participate as speakers with a growing annual attendance that has averaged 120 students at these seminars in person or virtually through Zoom, Inc. software.

The Center hosts the Annual Networking Event in the Spring semester to provide students the opportunity to interact with CVM faculty, small animal, food animal, exotic animal and industry veterinarians, staff from USDA and NIH, admission representatives from several Colleges of Veterinary Medicine, NCSU Animal Education Units, and GRE preparatory representatives. These speakers volunteer 2 h of their evening to host a booth at the Networking Event where speakers are separated into one of the three areas based on their affiliation (university, private practice, or industrial/institutional). A fourth area is set up for students to attend scheduled Q&A sessions with speakers such as current DVM students, and VMCAS representatives. Since its creation in 2010, the Networking Event has seen an increase in attendance from 74 students to over 220 students in 2020. The Networking Event creates opportunities for NCSU preveterinary students annually to develop their networking skills and to establish critical connections in the veterinary community. Feedback surveys report that the majority of students feel more confident in their ability to network with professionals in the field, in addition to becoming more knowledgeable about the shadowing and employment opportunities available. Students often report leaving the Annual Networking Event with offers for job or internship interviews.

More students are engaging in VetPAC services since the Center’s creation in 2011, and an increase in awareness of VetPAC services has established a consistent need for its event programming and advising services (Table 1).

Table 1.

Total number of participants in VetPAC events per year

| Year | Event | Total participants per event |

|---|---|---|

| 2012 | Annual Networking Event | 74 |

| 2013 | Annual Networking Event | 78 |

| 2014 | Fall Seminar Series | 55 |

| Annual Networking Event | 109 | |

| 2015 | Fall Seminar Series | 208 |

| Annual Networking Event | 135 | |

| 2016 | Fall Seminar Series | 169 |

| Annual Networking Event | 160 | |

| 2017 | Fall Seminar Series | 367 |

| Annual Networking Event | 135 | |

| 2018 | Fall Seminar Series | 219 |

| Pre-Vet First Year Orientation | 58 | |

| Annual Networking Event | 171 | |

| 2019 | Fall Seminar Series | 139 |

| Pre-Vet First Year Orientation | 84 | |

| Annual Networking Event | 207 | |

| 2020 | Fall Seminar Series | 88 |

| Pre-Vet First Year Orientation | 150 | |

| Annual Networking Event | 209 |

CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT

A one-credit course, ANS 281 Professional Development of Pre-Veterinary Track Students, was created to meet the prerequisite for a professional development course for one CVM requirements. The course objectives include:

Identify and critique current issues facing the veterinary profession;

Create a career map for successful admission into veterinary school;

Select internships to diversify animal and veterinary experiences for a competitive application;

Create a VMCAS application;

Draft a personal statement and DVM interview questions for a successful application;

Create a list of career options available to a veterinarian;

Compare and contrast the role of a Dairy and Equine veterinarian to identify personal career goals;

Compare the diversity in the skill set of an Exotic animal veterinarian to identify personal career goals

Identify and assess the role of a Swine veterinarian to select personal career goals;

Identify and reflect on the role of a Lab animal veterinarian to select personal career goals;

Analyze paraprofessional career paths in veterinary medicine;

Plan and manage financial goals for veterinary school loan payment.

This course offers concrete career mapping options that aid students in becoming a competitive VMCAS applicant. A study completed on professional veterinarians’ mental health in 2018 reported that the primary and secondary reasons for mental health concerns in the average professional veterinarian were student debt and financial stress (Volk et al., 2018, 2020). While some veterinary colleges are aware of this concern and offer financial planning to DVM students, it is increasingly important to ensure that undergraduate preveterinary students understand how to realistically address the financial burden that a DVM can become (Lord et al., 2013). To proactively address these concerns, ANS 281 incorporates financial planning into the curriculum. The course requires students to review the cost of tuition and living expenses at their desired CVM, to consider how students will pay for their tuition through loans or time away from school, and to calculate the cost of applying to multiple veterinary colleges. Currently, ANS 281 offers enrollment to 100 students, and teaching assistants are current DVM applicants who serve as role models for the course participants. The students are also required to attend VetPAC’s Annual Networking Event and CVM NCSU Open House to facilitate effective network building.

Research indicates that study abroad experiences provide many benefits for students including increased cultural awareness, global empathy, improved adaptability, patience, flexibility, and self-determined intellectual and personal growth (Cisneros-Donahue et al., 2012; Bretag and van der Veen, 2017; Maharaja, 2018). The Program Director has developed three hands-on experiential short-term study abroad courses that are 15 days in length, excluding travel, during the winter and summer breaks. These courses cultivate global curiosity and interpersonal growth and provide much-needed global veterinary experiences. The VetPAC Director, whom accompanies the students during activities and excursions, coordinates and co-teaches each study abroad course. The winter wild-life conservation and management course in India (2010–14) had 83 participants, whereas the summer course in South Africa (2016–19) had 67 participants. Students were engaged in the hands-on opportunity to work with endangered wild-life including tigers, zebras, giraffes, kudus, wild dogs, cheetahs, rhinos, and cape buffaloes. Students also practiced preventive wild-life veterinary care, dart assembly, tranquilization practice, radio-telemetry, and other wild-life techniques utilized in species conservation. A third study abroad course on Introduction to Animal Behavior and Veterinary Physiotherapy in the United Kingdom has taught 38 students assessment of companion and farm animal behavior as well as massage therapy, electrotherapy, and hydrotherapy as a part of the physiotherapy module at Harper Adams University. The format of the study abroad courses offers both large group experiences such as lectures and excursions and smaller group experiences such as hands-on labs and veterinary work. Through these courses, students are not only able to gain experiential veterinary hours in exotics as well as animal behavior, but also become unique veterinary college applicants. Feedback from study abroad course surveys is overwhelmingly positive with students citing the veterinary experiences and cultural excursions as the most influential aspects of their experience.

EXPERIENTIAL OPPORTUNITIES

Internships

Developed by the VetPAC Director, the main tenets of VetPAC advising are the “three D’s” for successful admission into veterinary colleges: diversity, duration, and depth of experiences. To address the need for consistent yet unique opportunities, VetPAC has created five distinct internships that offer options to work in a variety of veterinary disciplines from shelter medicine to museum medicine. The internships are available throughout the year through established voluntary partnerships with local organizations including the Wake County Animal Shelter (WCAC), Museum of Natural Sciences, and College of Veterinary Medicine. These partnerships, created with alumni and faculty of CVM NCSU who were veterinarians on-site, did not involve the creation of a contract. The internships serve to fill temporary worker roles on-site while recruiting, retaining, and mentoring preveterinary students through internship contracts that VetPAC oversees. Each internship involves formal learning objectives that students must meet to complete the internship and provides students with veterinary experience hours for their VMCAS along with a certificate of completion.

Research shows that students who engage with mentors and internships within their field are more likely to continue in that career path after graduation (Willoughby, 2004) and that students who engage in their field through internships or work-integrated learning activities are more likely to build stronger professional identities. It is critical for preprofessional students to not only shadow the people who work in their fields, but also perform the work that is being done, so that students see themselves in that career rather than just as an aspiring student (Jackson, 2017). Over the past 10 years, VetPAC’s internships have grown to offer many opportunities for clinical skill-building, career exploration, and professional identity development.

Shelter Medicine Internship

Since 2010, the Shelter Medicine Internship has provided 73 undergraduate students the opportunity to engage in all aspects of shelter animal care including shelter husbandry, animal behavior, and providing veterinary care for all abandoned animals at WCAC including cats, dogs, and pocket pets. Interns gain the opportunity to practice practical skills including venipuncture, FIV testing, preparing animals and rooms for surgery, and providing medication. In addition to the veterinary skills listed, interns also assist with shelter tasks including walking dogs, cleaning kennels, providing feed/water for kennel occupants, and photographing animals for adoption. Through these experiences, students learn about the non-clinical responsibilities of shelter veterinarians and engage in all aspects of shelter animal care.

Museum Medicine Internship

Established in 2011, the Museum Medicine internship has offered hands-on experience to 56 interns in a variety of aspects of care for exotic species including reptiles, amphibians, mammals, birds, fish, and invertebrates in the Veterinary Services Unit of the Living Collections Section of the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences. Through this hands-on experience, interns not only build their clinical skills, but also improve their ability to interact with and educate the public on exotic wild-life. An important and distinctive opportunity through this internship is the responsibility of interns to work within the Window on Animal Health—a glass window exhibit that allows visitors a full view of both the veterinary medicine procedure room and the clinical veterinary medicine laboratory. Interns educate the public on the care of the animals within the museum and allow visitors a glimpse into the world of veterinary medicine. Through this internship, students build their clinical, communication, and public-speaking skills.

Feline Health Internship

As a second collaboration with the WCAC in 2018, the Feline Health internship focusses on both clinical and research hours while also providing WCAC with much needed assistance during kitten season. Interns have the opportunity to work in the shelter alongside Animal Health Care Technicians, Veterinary Technicians, and a Foster Coordinator to gain practical experience on neonatal shelter intake, feline husbandry, surgery preparations, and foster parent training. Participants also have the opportunity to work on feline neonatal mortality research projects with the shelter veterinarians and CVM researchers to obtain research experience for the VMCAS.

Canine College Internship

The newest internship was created in 2019 and is a collaborative partnership with the CVM’s Canine College to provide interns with experiences offering enrichment and socialization for a stock colony of laboratory dogs. Interns obtain an introduction to lab animal basics and canine handling experience while utilizing positive reinforcement training to socialize the dogs and acclimate them to activities such as being handled for examinations. As part of the partnership, interns are assigned to a DVM student mentor and work with the CVM staff. This internship provides students with strong connections to the CVM and a unique opportunity to explore animal behavior.

Jones et al. (2014) found that the number of opportunities available as extracurricular experiences significantly contributes to a student’s likelihood to engage in a specific subfield. By providing distinct internships that students can use to explore the variety of options within the field of veterinary medicine, students gain valuable opportunities for career exploration.

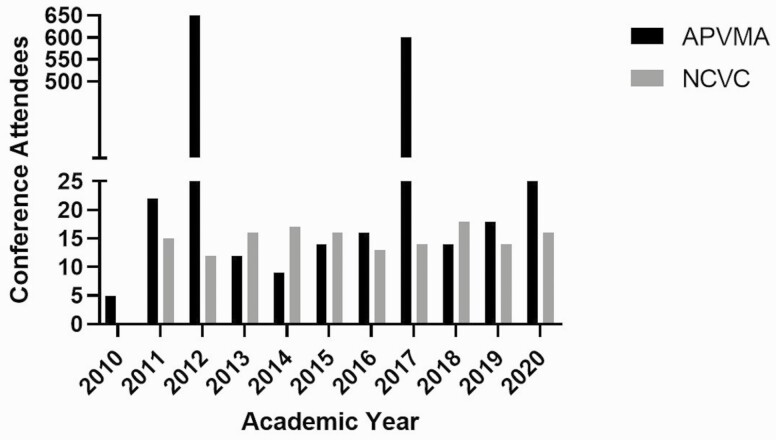

Annual Conference Involvement

To assist students in gaining professional development and building their networking skills, VetPAC annually takes student delegates to both the North Carolina Veterinary Conference (NCVC) and the American Pre-Veterinary Medical Association (APVMA) Annual Symposium. Since 2010, VetPAC has taken over 255 students to these conferences and hosted the APVMA Annual Symposium twice (2012 and 2017) (Figure 2), thus allowing students the opportunity to network with professionals nationally, take on national leadership positions, and learn about current topics in veterinary medicine.

Figure 2.

Annual Conference Attendance. Total student representation at state veterinary and national preveterinary conferences.

By attending lectures and workshops, sharing meals with professionals, and exploring the different booths at conferences, students have the ability to make impressions that generally lead to potential interview or career opportunities. Students who attend APVMA can explore a CVM that they might otherwise not have visited without financial assistance. The VetPAC Director encourages and prepares students to compete for national executive positions as well as to bid for hosting the annual conferences. With VetPAC assistance, nine students within the past 10 years have attained national positions on the APVMA national executive board including two APVMA presidents, three vice presidents, two secretaries, and two treasurers. Pohl and Butler (1994) assert that membership in preprofessional organizations improves students’ critical thinking and cooperative learning skills through their duties as executive members. They also speculate that this opportunity for involvement and development contributes to students’ desirability to future employers.

In addition to the APVMA Annual Symposium, VetPAC provides financial assistance for its interns to attend the NCVC. During the NCVC, VetPAC interns are required to host one shift at the VetPAC booth in the exhibitor hall to interact with participating veterinarians, veterinary technicians, and other paraprofessionals. Through these connections built during conferences, many students gain a job or a summer internship offer and invite veterinarians to VetPAC events.

RECRUITMENT AND OUTREACH

VetCAMP

A summer camp called VetCAMP was created in 2011 as an opportunity for high school students to gain hands-on preveterinary experience prior to college, and it has since served as a recruitment platform for the major, college, and the preveterinary advising center. Due to the consistent interest in VetCAMP, the camp’s capacity has increased from 1 week of 40 students to 3 weeks of lectures, labs, clinical simulations at animal education units, anatomy labs, and CVM for 120 students. The camp is coordinated and staffed by the VetPAC Director, Program Associate, and a team of undergraduate student counselors from a variety of majors including Animal Science, Zoology, Biology, etc. Campers gain valuable veterinary hours including small, large, food and exotic animal experiences that can be added to both undergraduate and DVM admissions applications. Research shows that high school students who engage in summer camps in a field of interest exhibit an increased desire to attend the university where the camp is held and increased desire to continue in that field of study (Jogan et al., 2009; Bhattacharyya et al., 2011; Weisman et al., 2011; Myers et al., 2012). This is especially important due to the lack of representation of diverse identities such as males, students of color, and students from rural and economically depressed state counties within veterinary medicine (Sprecher, 2004; Weisman et al., 2011). The VetCAMP serves as an outreach event that provides career exploration and career planning information to high school students of all backgrounds, including underrepresented ethnic minority (URM) identities. The VetPAC has been intentional in its annual application review process to consider diversity in participants by inviting a minimum of 20% of campers from underserved state counties and URM applicants.

VetCAMP provides a consistent source of revenue that supports VetPAC programs like conference travel, program materials, event planning, and resource attainment. Garis (2014) proposed that a model Career Center is one that has the support of its university as well as its community partners and VetPAC has been able to establish that model effectively. VetCAMP programming uses a combination of volunteer and paid partners including NCSU Animal Education Units, CVM NCSU staff, community partners, and undergraduate student assistance. The VetCAMP application and camp fees cover the cost of advertising, camp materials, camp counselor fees, speaker fees, housing, transportation, and meals. Any remaining revenue assists with VetPAC programming.

High School Outreach

A high school outreach program was also established in which interns and the VetPAC Director participate in information sessions, attend career fairs, and hold meetings for students visiting campus. Generally, VetPAC interns visit an average of 13 high schools per academic year to provide information about preveterinary student life, show diversity within the veterinary career path, and proactively inform high school students about the requirements for veterinary admissions. In addition to traveling to events, VetPAC hosts scheduled meetings with prospective students and their families through the Spend a Day at State program. This meeting offers prospective students the chance to visit the center and receive a packet of information compiled for families including a VetCAMP flyer, a VetPAC brochure, and information on DVM admissions. The Center has interacted with over 300 students as part of the Spend a Day at State program in the past 5 years.

USDA Multicultural Scholars Program Grant

In 2013, the VetPAC Director successfully competed for the Multicultural Scholars Program grant for increasing the recruitment, mentoring, and retention of multi-cultural preveterinary scholars. This grant supported six URM students from 2014 to 2019 by providing a strategic plan to introduce career exploration and growth through yearly internships, teaching assistantships, and focussed advising sessions with the VetPAC Director. The program achieved a 100% success rate as all six students were successfully admitted to CVM within the United States (five students) and United Kingdom (one student).

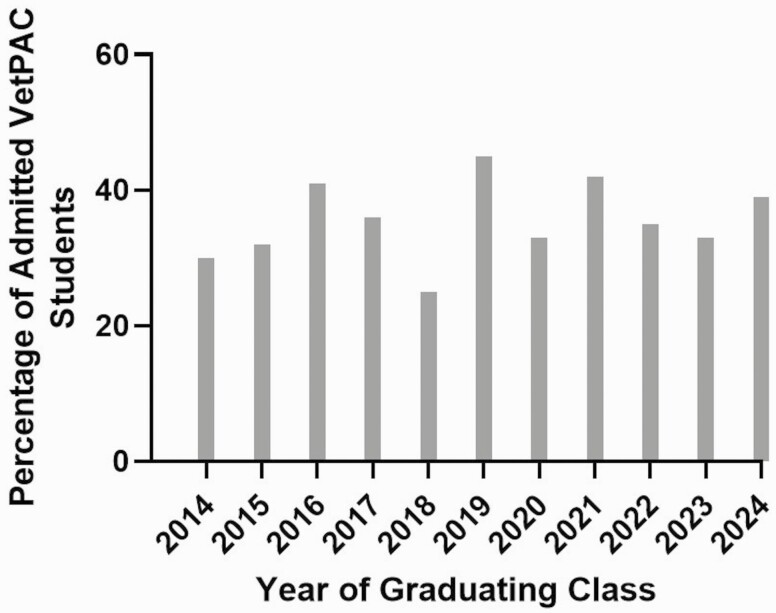

MATRICULATION

Since 2010, VetPAC has assisted 386 students in achieving admissions in-state to CVM NCSU (Figure 3) and a total of 436 with out-of-state CVM placements included. The incoming CVM NCSU class annually consists of 100 students, of which 26–45% of the past 10 years classes have been undergraduates who utilized VetPAC services. Due to the inaccessibility of out-of-state admissions data and it being largely self-reported, only CVM NCSU admissions data are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

CVM Matriculation. The percentage of VetPAC students admitted to CVM NCSU in each graduating class.

Additionally, the Center is unable to provide data on the total number of NCSU undergraduate students admitted to CVM NCSU prior to the establishing VetPAC as the comparison data are not available for the 10-year span prior to represent acceptance to CVM NCSU accurately.

In the end of the Fall and Spring semesters, the Program Director hosts a VMCAS overview session for current applicants to review the latest updates to each application cycle, review the four sections of the VMCAS, provide tips to clearly and concisely describe experiences, and recommend available opportunities for strengthening the application. Once students start receiving interview invitations, the VetPAC Director meets with the applicants to assist them in doing extensive research on veterinary colleges’ programmatic strengths, DVM curriculum, caseload in clinics, unique opportunities on-campus and off-campus and reviews the interview process for the traditional as well as multiple mini interview format. Mock interviews preparation is conducted by the director via group advising and on an individual student practice session. The multidimensional approach of consistent yearly advising, hosting VMCAS overview sessions, performing intensive VMCAS review, and enhancing DVM interview skills has assisted in the distinctive success of VetPAC student placements in veterinary colleges in the United States and abroad.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Since inception 10 years ago, VetPAC continues to be unique as a preveterinary advising center within an Animal Science Department at a Land-Grant University. By presenting the program structure, programmatic development, and curricular enhancements, it is hoped that other departments will strongly consider development of a preveterinary advising program beneficial to the success of their students. Moving forward, VetPAC will continue to maintain its current partnerships while creating additional programs to help sustain its efforts in holistic advising. Currently, the VetPAC YouTube channel is being launched to highlight the multitude of internships, unique study abroad courses, preveterinary spotlight series, and annual events. In addition, VetPAC hopes to utilize its current social media platforms such as Instagram (https://www.instagram.com/ncstate_vetcamp/), Twitter (https://twitter.com/ncstatevetpac), and Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/vetpac.ncsu) to disseminate programmatic information to a wider variety of stakeholders. With the awareness that most veterinarians are experiencing high levels of stress and their student debt is affecting their quality of life (Drake et al., 2017; Volk et al., 2018, 2020), VetPAC has set out to proactively address these concerns by collaborating with mental health professionals to create a series of mental health workshops with the University Counseling Center. Additional research shows that veterinary students are experiencing increased and prolonged levels of stress, depression, and anxiety (Drake et al., 2017; Killinger et al., 2017). The VetPAC mental wellness workshops are aimed at proactively teaching students effective stress management skills, time management skills, and general anxiety coping skills. It is a first step to introduce students early in their careers to healthy coping mechanisms and to destigmatize seeking help.

CONCLUSION

Since its inception, VetPAC has increasingly built multifaceted yet sustainable programming to support preveterinary students within the Animal Science major and others. The programmatic logistic and institutional support is outlined with the hope that it serves as a framework for similar programs to develop in other animal science programs across the nation. With 24 out of the 32 veterinary colleges doing a holistic review of their veterinary program applicants, it is critical that a variety of opportunities be available to students for mindful exploration of the feasibility of veterinary medicine as a career option. Along with the experiential opportunities, non-cognitive or non-academic skills like leadership, teamwork, communication, and emotional maturity should be the focus of additional programming offered through the center.

The lessons learned in the past 11 years of VetPAC are numerous.

I. Enhancing the visibility of the program is essential as stakeholders from within and outside of the institution show greater investment in supporting student success. A detailed interactive website of the program, social media presence, attendance of local events and national conferences, and finally pedagogy in the form of manuscripts are key to advancing the mission of the center.

II. The development and management of internships is a gradual yet continuous partnership effort that can be sustained when the partner institutions also have stakes such as a need for temporary manpower or equipment or purchase of supplies. Identifying mentors in a partner institution who will provide a robust on-site training and education is critical.

III. Curriculum development for student engagement and mentoring should be diversified such that it meets students’ academic goals (capstones, honors, certificates, etc.) as well as guides them toward a competitive veterinary school application. Team-taught career exploration courses, study abroad program development, and introduction of research methods courses are helpful in diversifying curricular advancements.

IV. Continuous adaptation of the advising programming to meet the changes in veterinary admissions trends helps reduce redundancy and makes students aware of their options. The VMCAS has changed several times in the last 7 years. From having a new application platform to requiring a three-prompt essay then reverting back to single essay to changing character limits on duty descriptions, the changes have been multiple in nature.

V. Establishing a financial sustainability model along with the administrators of the department and college is critical to robust programming. Annual summer camps and workshop fees along with consistent fundraising around specific student programs and demonstrating their impact to the donors assist in gaining long-term financial support.

It is aspired that the reflections on the evolution of this advising center and its contributions will assist the animal science academic community in the planning and execution of their own respective centers.

LITERATURE CITED

- Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges . 2020. Summary of Course Prerequisites: For All AAVMC Member Institutions for 2021 Matriculation.AAVMC. Available fromhttps://www.aavmc.org/assets/Site_18/files/VMCAS/VMCASprereqchart.pdf. Retrieved March 3, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya, S., Mead T., and Rajkumar N.. . 2011. The influence of science summer camp on African-American high school sudents’ career choices. School Sci. Math. 111(7):345–353. [Google Scholar]

- Bretag, T., and van der Veen R.. . 2017. “Pushing the boundaries”: participant motivation and self-reported benefits of short-term international study tours. Innov. Educ. Teaching Int. 54(3):175–183. doi: 10.1080/14703297.2015.1118397 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buchannan, D. 2008. ASAS Centennial Paper: Animal science teaching: A century of excellence. J. Anim. Sci. 86:3640–3646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cisneros-Donahue, T., Krentler K., Reinig B., and Sabol K.. . 2012. Assessing the academic benefit of study abroad. J. Edu. Learning 1(2). doi: 10.5539/jel.v1n2p169 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drake, A. A., Hafen M. Jr, and Rush B. R.. . 2017. A decade of counseling services in one college of veterinary medicine: veterinary medical students’ psychological distress and help-seeking trends. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 44:157–165. doi: 10.3138/jvme.0216-045R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foli, K. J., Braswell M., Kirkpatrick J., and Lim E.. . 2014. Development of leadership behaviors in undergraduate nursing students: a service-learning approach. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 35:76–82. doi: 10.5480/11-578.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garis, J. 2014. Value-added career services: creating college/university-wide systems. New Direct. Student Serv. 2014:19–34. doi: 10.1002/22.20106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grevemeyer, B., Betance L., and Artemiou E.. . 2016. A telephone communication skills exercise for veterinary students: experiences, challenges, and opportunities. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 43:126–134. doi: 10.3138/jvme.0315-049R1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, N. P., Rhind S. M., Moore L. J., Dawson S., Kilyon M., Braithwaite K., Wason J., and Mellanby R. J.. . 2009. Admissions processes at the seven United Kingdom veterinary schools: a review. Vet. Rec. 164:583–587. doi: 10.1136/vr.164.19.583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, D. 2017. Developing pre-professional identity in undergraduates through work-integrated learning. Higher Educ. 74:833–853. doi: 10.1007/s10734-016-0080-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jogan, K., Jack N., Herring D., and Caldwel J.. . 2009. University horse camp for children as recruiting tool for animal science. NACTA; Twin Falls 53:32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M., Rush B., Elmore R., and White B.. . 2014. Level of and motivation for extracurricular activity are associated with academic performance in the veterinary curriculum. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 41(3):275–283. doi: 10.3138/jvme.1213-163R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killinger, S. L., Flanagan S., Castine E., and Howard K. A.. . 2017. Stress and depression among veterinary medical students. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 44:3–8. doi: 10.3138/jvme.0116-018R1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knotts, G., and Wofford C.. . 2017. Perceptions of effectiveness and job satisfaction of pre-law advisors. NACADA 37(2):76–87. doi: 10.12930/NACADA-16-006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan, L., and McConnell S.. . 2001. Gaining acceptance into veterinary school: a review of medical and veterinary admissions policies and practices. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 28(3):101–110. doi: 10.3138/jvme.28.3101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehker, T., and Furlong J.. . 2006. Career services for graduate and professional students. New Direct. Student Serv. 115:73–83. doi: 10.1002/ss.217 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lord, L. K., Brandt J. C., and Newhart D. W.. . 2013. Identifying the needs of veterinary students and recent alumni in establishing a student service center. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 40:192–198. doi: 10.3138/jvme.1212-106R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, J., and Lungrin T.. . 2018. Integrating academic and career advising toward student success. New Direct. Higher Educ. 184:69–77. doi: 10.1002/he.20304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maharaja, G. 2018. The impact of study abroad on college students’ intercultural competence and personal development. Int. Res. Rev.: J. Phi Beta Delta Honor Soc. Int. Scholars 7(2):18–40. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott, M. P., Tischler V. A., Cobb M. A., Robbé I. J., and Dean R. S.. . 2015. Veterinarian-client communication skills: current state, relevance, and opportunities for improvement. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 42:305–314. doi: 10.3138/jvme.0115-006R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers, T. L., DeHart R. M., Dunn E. B., and Gardner S. F.. . 2012. A summer pharmacy camp for high school students as a pharmacy student recruitment tool. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 76:60. doi: 10.5688/ajpe76460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelzer, J. 2018. Advising pre-veterinary students: What you need to know. The Advisor: J. Natl Assoc. Advisors Health Prof. 38(4):19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Pohl, G., and Butler J.. . 1994. Public relations in action: a view of the benefits of student membership in pre-professional organizations. Experiential Learning Division of the Speech Communication Association at the National Convention. New Orleans, LA, November 19–22, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, T. 2013. Advising pre-professional students: encouraging an optimistic yet realistic perspective. Acad. Advising Today 36(2). Available from: https://nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Academic-Advising-Today/View-Articles/Advising-Pre-Professional-Students-Encouraging-an-Optimistic-yet-Realistic-Perspective.apsx. Retrieved November 12, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schaub, M. 2012. The profession of college career services delivery: what college counselors should know about career centers. J. College Student Psychother. 26:201–215. doi: 10.1080/87568225.2012.685854 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher, D. 2004. Insights into the future generation of veterinarians: perspectives gained from the 13- and 14-year-olds who attended Michigan State University’s Veterinary Camp, and conclusions about our obligations. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 31(3):199–202. doi: 10.3138/jvme.31.3.199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, R. E., and Kauffman R. G.. . 1983. Teaching animal science: changes and challenges. J. Anim. Sci. 57(2):171–196. Available from: 10.2527/animalsci1983.57Supplement_2171x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Volk, J., Schimmack U., Strand E., Lord K., and Siren C.. . 2018. Merck Animal Health Veterinarian Well-being Study 2017. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 252(10):P1231–P 1238. doi: 10.2460/javma.252.10.1231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk, J., Schimmack U., Strand E., Vasconcelos J., and Siren C.. . 2020. Merck Animal Health Veterinarian Well-being Study 2020.Institution: Merck Animal Health. Available from: https://www.merck-animal-health-usa.com/offload-downloads/veterinary-wellbeing-study. Retrieved March 1, 2021 [Google Scholar]

- Weisman, J. L., Amass S. F., and Warren J. D.. . 2011. Impact of the Purdue University School of Veterinary Medicine’s Boiler Vet Camp on participants’ knowledge of veterinary medicine. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 238:878–882. doi: 10.2460/javma.238.7.878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby, D. A. 2004. Using Professional industry partnerships for advising students at a two-year technical college. NACTA Dec. 2004:1–5. [Google Scholar]