Abstract

Aging-associated fall-risk assessment is crucial for fall prevention. Thus, this study aimed to develop a prognostic model to predict fall-risk following an unexpected over-ground slip perturbation based on normal gait pattern in healthy older adults. 112 healthy older adults who experienced a novel slip in a safe laboratory environment were included. Their slip trial and natural walking trial immediately prior to it were analyzed. To identify the best fall-risk predictive model, gait related variables including step length, segment angles, center of mass state, and ground reaction force (GRF) were determined and inputted into a stepwise logistic regression. The optimal slip-induced fall prediction model was based on the right thigh angle at slipping foot touchdown (TD), the maximum GRF of the slipping limb after TD, and the momentum change from TD to recovery foot liftoff (LO), with an overall prediction accuracy of 75.9%, predicting 74.5% of falls (sensitivity) and 77.2% of recoveries (specificity). Conversely, a model based on clinical and demographic measures predicted 78.2% of falls and 47.4% of recoveries, resulting in a much lower overall accuracy of 62.5%. The fall-risk model based on normal gait pattern which was developed for slip-induced perturbations in healthy older adults was able to provide a high predictive accuracy. This information could provide insight about the ideal normal gait measures which could be used to contribute towards development of therapeutic strategies related to dynamic balance and fall prevention to enhance preventive interventions in populations with high-risk for slip-induced falls.

Keywords: Fall-risk, Slip, Fall prediction model, Gait pattern

1. Introduction

Falls are a serious and growing health concern, affecting nearly 30% of older adults in the US (Burns et al., 2016). The consequences of falls can range from fractures, to serious disability, and even death (Stel et al., 2004; Stevens and Sogolow, 2005), with an annual cost of approximately $31 billion (Burns et al., 2016). Despite many being able to partake in independent community ambulation, older adults continue to be at a high risk for falls (Timsina et al., 2017) with about 70% of overall falls being due to external perturbations (Heijnen and Rietdyk, 2016) and around 40% being slip-induced (Boyé et al., 2013). Thus, it is crucial to develop accurate predictive techniques to identify older adults vulnerable to falls and design effective preventive interventions for these at-risk individuals.

Previous evidence indicates that falls result from a combination of intrinsic (age, mobility impairments, and neurological disorders) and extrinsic (slippery surfaces, improper footwear, and clutter) factors which has made the development of fall-risk models challenging (Hoang et al., 2017; Lannering et al., 2016). Most of the previous fall-risk prediction models that were based on clinical scales or gait parameters have demonstrated limited predictive capacity (overall accuracy < 70%) (Gates et al., 2008; Greene et al., 2010; Paterson et al., 2011; Sterke et al., 2012; van Schooten et al., 2015). For example, clinical balance measures such as the Berg Balance scale (BBS) and the Timed Up-and-Go (TUG) test showed prediction accuracies less than 65% for healthy older adults (Bhatt et al., 2011; Greene et al., 2010). Such limited prediction power of these clinical assessments could possibly be related to their inability to detect age-related neuromuscular and musculoskeletal declines due to ceiling effects (Voermans et al., 2007).

Conversely, spatio-temporal gait parameters, which have been widely used for fall-risk evaluations (Espy et al., 2010a; Scott et al., 2007; van Schooten et al., 2015), demonstrated either equivalent or better fall prediction accuracy compared to clinical balance tests (Viccaro et al., 2011). Among the gait parameters, step length, step time, step time asymmetry, and stride regularity demonstrated a fall prediction capability (area under curve (AUC) < 0.66) comparable to the aforementioned balance tests (Bautmans et al., 2011; Rispens et al., 2015; Sterke et al., 2012). While gait speed previously showed a better fall-risk predictive ability (AUC = ~0.7 or accuracy = ~70%) and has been recommended for fall prediction (Maki, 1997; Viccaro et al., 2011), opposing findings from several other studies indicated no relationship between gait speed and fall-risk (Brach et al., 2005; Rispens et al., 2015; van Schooten et al., 2015). Similarly, studies indicated conflicting findings on how step length could affect fall-risk, with some reporting fallers showed a much smaller step length than non-fallers (Mbourou et al., 2003; Taylor et al., 2013) while others found longer steps were associated with a greater fall probability (Espy et al., 2010a; Moyer et al., 2006). Such heterogeneity amongst results decreases the value of these evaluations and further limits their clinical application.

A plausible cause of heterogeneity in the results might be the lack of consideration of fall-specific variables, such as fall type (slip- or trip-induced fall), as spatio-temporal gait parameters differ between fall types (Kangas et al., 2012; Smeesters et al., 2001, 2007). Most of the developed models included all fall types without differentiating between the mechanisms of falls which could result in heterogeneity between results and poor prediction accuracy. Further, the falls data used in previously developed models was mostly in the form of participant-reported retrospective history of falls or prospective falls in real-life over 6 months or a year (Gates et al., 2008; Murphy et al., 2003; van Schooten et al., 2015). With self-reporting of falls, both fall frequency and fall specifics (type or cause) may likely not be accurate, making the reliability of such fall prediction models questionable.

In light of the drawbacks of previous models, it is necessary to design a fall-risk model based on laboratory-induced falls to predict falls among older adults using a multifactorial approach (van Schooten et al., 2015). Previously, a laboratory trip-induced fall-risk model based on gait characteristics classified trip-related fall outcomes with 89.8% accuracy (Pavol et al., 1999). However, no slip-induced fall-risk model has been successfully developed.

Using a direct, prospective, and experimental approach, the aim of this study was to develop a model based on healthy older adults’ normal gait pattern to accurately predict fall-risk following an unexpected over-ground slip in a safe laboratory environment. We hypothesized that this model would be able to predict older adults’ slip-related fall-risk with greater accuracy than previous models. Additionally, a model based on clinical and demographic measures was developed to compare its predictive capacity with that of the model based on gait parameters. In a clinical setting, the development of such a specific fall prediction model could help identify vulnerable individuals with high slip-related fall-risk and potentially facilitate development of appropriate preventive therapeutic strategies for older adults.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

112 community-dwelling older adults (≥ 65 years) were included in this study (Table 1). All participants were screened via questionnaires before their training session to exclude those with neurological, musculoskeletal, cardiopulmonary, or any other systemic disorders. All participants provided written informed consent, approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Table 1.

Predictive validity of demographic and clinical measures using univariate logistic regression (n = 112).

| Variables | Mean ± SD | p value | SE | Spe | Sen | Acc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | 74.9 ± 15.0 | 0.033* | 0.013 | 63.2 | 58.2 | 60.7 |

| Height (m) | 1.67 ± 0.1 | 0.934 | 1.877 | 100 | 1.8 | 51.8 |

| Age (yrs) | 67.7 ± 5.9 | 0.119 | 0.033 | 50.8 | 54.6 | 52.7 |

| Gender | Male: 54 | 0.342 | 0.380 | 52.6 | 56.4 | 54.5 |

| BBS | 53.8 ± 2.5 | 0.713 | 0.076 | 75.4 | 32.7 | 54.5 |

| TUG (s) | 8.2 ± 1.5 | 0.552 | 0.148 | 25.5 | 76.4 | 51.9 |

| Fall history | Yes: 48 | 0.092 | 0.387 | 64.9 | 50.9 | 58.0 |

denotes p value < 0.05.

BBS: Berg Balance Scale; TUG: Timed Up-and-Go test; SE: standard error; Spe: specificity in percentage; Sen: sensitivity in percentage; and Acc: overall accuracy in percentage. Specificity denotes recovery prediction and sensitivity denotes fall prediction.

2.2. Experimental setup

All participants experienced a forward slip. The slip was induced by releasing low-friction (coefficient of friction < 0.05), movable platforms embedded near the middle of a 7-meter walkway. The platforms were firmly locked during the first eight walking trials. During the slip trial, these platforms could freely slide forward in the anteroposterior (AP) direction for up to 60 cm. Once a participant’s right (slipping) foot was detected by the force plates (AMTI, Newton, MA) installed beneath the right platform (Pai et al., 2014b), a computer-controlled triggering mechanism released the right platform. Participants were instructed to walk with their preferred (self-selected) speed and manner, and they were informed that a slip may or may not occur during any of the trials. They were told that upon experiencing a slip they should try their best to recover their balance and continue walking. All participants experienced at least one slip perturbation. The first slip trial and the natural walking trial right before were then analyzed in this study. On the first slip trial, preliminary analysis indicated that all participants experienced a slip with similar intensity (peak displacement: 56.7 ± 8.3 cm).

A full-body safety harness connected by shock-absorbing ropes to a loadcell was used (Transcell Technology Inc., Buffalo Grove, IL). The load cell was mounted to an overhead trolley on a track over the walkway. The harness enabled participants to walk freely while providing protection against body impact with the floor. Kinematics from a full body marker set (30 retro-reflective markers) were recorded by an eight-camera motion capture system (Motion Analysis Corporation, Santa Rosa, CA). Kinematic data was sampled at 120 Hz and synchronized with the force plate and loadcell data, which was collected at 600 Hz.

2.3. Outcome variables

A fall was identified when the peak load cell force during a slip exceeded 30% of the participant’s body weight (BW) (Yang and Pai, 2011), otherwise the trial was a non-fall (recovery). In this study, 55 of the 112 participants were fallers, while the other 57 were non-fallers. The crucial time events included slipping (always right) foot touchdown (TD) on the slider and the following foot liftoff (LO), which were detected from force plate data during the natural walking trial immediately prior to the first slip.

2.4. Fall-risk factors

In line with previous studies (Bhatt et al., 2011; Espy et al., 2010a; Paterson et al., 2011; van Schooten et al., 2015), descriptive characteristics, clinical balance scales, and gait spatio-temporal parameters were included in our slip-induced fall predictive model. Descriptive characteristics including age, body weight, and body height were obtained. Fall history was obtained by participants’ self-reported number of falls experienced in the last 12 months. Data collection for clinical balance scales such as BBS and TUG were performed just before the experiment.

Gait spatio-temporal parameters were calculated from motion and force data of the regular walking trial. Step length and step width were calculated as the heel distance between both feet at TD in the AP and mediolateral (ML) directions, respectively. Gait speed was determined as the mean value of the center of mass (COM) speed, which was approximated using the sacral marker (Yang and Pai, 2014). COM relative position and velocity at TD were calculated relative to the heel marker of the slipping foot (Yang et al., 2008). Segment (trunk, thigh, shank, and foot) angles in the sagittal plane were calculated based on motion-capture-derived body segment coordinates. Segment velocity was derived from the corresponding segment angle. Segment kinematics at TD were included in this study. As the push off force reaches its peak at around 100 ms prior to LO (Winter, 1989), maximum accelerations and GRFs for the left foot at LO in the AP and vertical directions were calculated in pre-LO (LO – 80 ms to LO – 120 ms), while maximum GRFs on the right foot in the AP and vertical directions were calculated in post-TD (TD + 80 ms to TD + 120 ms). This 80 ms represents the time taken for the landing foot to come to rest (deceleration = 0 m/s2) (Cham and Redfern, 2002), and the 120 ms represents the time at which the slider was in motion (with slip distance > 5 cm) during the actual slip trial. Hence, slip intensity was mainly affected by this post-TD duration. Linear momentum was measured as a product of body mass and COM velocity in the AP direction, and the momentums at TD and LO were included in this study.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Univariate logistic regression was performed to identify variables predictive of slip-induced falls versus recovery outcomes. Predictive accuracy were performed for each variable between fallers and non-fallers at a cutoff score of 0.5 (Bhatt et al., 2011). Subsequently, backward stepwise multivariate logistic regression was performed to predict slip-induced fall based on gait parameters in the previous walking trial. To avoid omitting any potential variables, all gait parameters were considered and entered in the predictive model (Ashburn et al., 2001; Patil et al., 2014). Any parameters whose p value exceeded the significance criterion (> 0.05) were removed from the multivariate model until all parameters satisfied the criterion. Meanwhile, the variance inflation factor was checked to quantify the severity of multicollinearity in the model, and any variable with variance inflation factor > 5 was excluded. The AUC of the final prediction model with the highest receiver operating curve (ROC) was calculated. Next, to compare the predictive capacity between gait parameters and clinical measures, descriptive characteristics and clinical balance scales were added in another prediction model using the same method. Additionally, to verify whether or not clinical and demographic measures could further enhance predictive capacity of the gait parameters model, descriptive characteristics and clinical balance scales were also added to the first model. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

3. Results

All 112 participants experienced a loss of balance upon experiencing an unexpected slip, and 55 (49.1%) failed to recover their balance and fell, while the remaining 57 (50.9%) successfully recovered. As shown in Table 1, weight was the only demographic variable with a significant effect on fall incidence (p < .05), demonstrating a prediction accuracy of 60.7%. Although fall history provided a similar predictive ability (58%), it exceeded the univariate significance criterion (p = .09).

For gait characteristics, step length, COM relative position at TD, right thigh angle at TD, right shank angular velocity at TD, right foot angular velocity at TD, maximum vertical GRF in pre-LO, momentum at TD, and momentum change from TD to LO all achieved significance based on univariate logistic regression (p < .05 for all, Table 2). Among these variables, momentum change from TD to LO was the best predictor of slip outcome with the highest predictive capability of 68.8% (p = .002) followed by right shank angular velocity at TD with a predictive capability of 65.2% (p = .006).

Table 2.

Predictive validity of gait characteristics using univariate logistic regression (n = 112).

| Independent variables | Mean ± SD | p value | SE | Spe | Sen | Acc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step length at TD/BH | 0.33 ±0.10 | 0.036* | 3.55 | 68.4 | 54.5 | 61.6 |

| Step width at TD/BH | 0.10 ±0.03 | 0.642 | 7.26 | 63.2 | 32.7 | 48.2 |

| Gait speed (m/s) | 1.13 ±0.18 | 0.291 | 1.08 | 64.9 | 45.5 | 55.4 |

| COM relative position at TD/BH | 0.19 ±0.06 | 0.003* | 7.12 | 63.2 | 63.6 | 63.4 |

| COM relative velocity at TD (m/s) | 1.17 ±0.20 | 0.313 | 0.99 | 66.7 | 47.3 | 57.1 |

| Trunk angle at TD (rad) | 1.53 ±0.08 | 0.562 | 2.51 | 66.7 | 36.4 | 51.8 |

| R thigh angle at TD (rad) | 1.94 ±0.12 | 0.006* | 2.17 | 66.7 | 63.6 | 65.2 |

| R shank angle at TD (rad) | 1.79 ±0.15 | 0.128 | 1.47 | 50.9 | 52.7 | 51.8 |

| R foot angle at TD (rad) | 0.18 ±0.12 | 0.130 | 1.57 | 64.9 | 49.1 | 57.1 |

| Trunk velocity at TD (rad/s) | 0.31 ±0.22 | 0.939 | 0.88 | 100 | 0 | 50.9 |

| R thigh velocity at TD (rad/s) | 0.36 ± 0.52 | 0.171 | 6.7 | 66.7 | 47.3 | 57.1 |

| R shank velocity at TD (rad/s) | −2.02 ± 0.65 | 0.025* | 0.32 | 66.7 | 60.0 | 63.4 |

| R foot velocity at TD (rad/s) | −3.62 ±1.56 | 0.019* | 0.13 | 59.6 | 56.4 | 58.0 |

| L foot AP acc in pre-LO (m/s2) | 16.1 ±5.3 | 0.886 | 0.04 | 100 | 0 | 50.9 |

| L foot VT acc in pre-LO (m/s2) | 9.0 ± 3.4 | 0.317 | 0.06 | 54.4 | 47.3 | 50.9 |

| R AP GRF in post-TD/BM | −1.33 ±0.57 | 0.105 | 0.34 | 61.4 | 52.7 | 57.1 |

| R VT GRF in post-TD/BM | 7.07 ±2.19 | 0.829 | 0.09 | 75.4 | 32.7 | 54.5 |

| L AP GRF in pre-LO/BM | 1.48 ±0.48 | 0.382 | 0.39 | 58.6 | 41.8 | 50.9 |

| L VT GRF in pre-LO/BM | 8.69 ±1.71 | 0.031* | 0.11 | 68.4 | 47.3 | 58.0 |

| MMT at TD (kg·m/s) | 87.8 ±19.9 | 0.023* | 0.01 | 68.4 | 52.7 | 60.7 |

| MMT at LO (kg·m/s) | 71.5 ±15.5 | 0.121 | 0.01 | 68.4 | 43.6 | 56.3 |

| MMT from TD to LO (kg·m/s) | −16.3 ±10.7 | 0.002* | 0.03 | 73.7 | 63.6 | 68.8 |

Denotes p value < 0.05.

TD: Right foot touchdown; LO: Left foot lift off; BH: body height; BM: body mass; AP: anteroposterior; VT: vertical; MMT: momentum; SE: standard error; Spe: specificity in percentage; Sen: sensitivity in percentage; and Acc: overall accuracy in percentage. Specificity denotes recovery prediction and sensitivity denotes fall prediction.

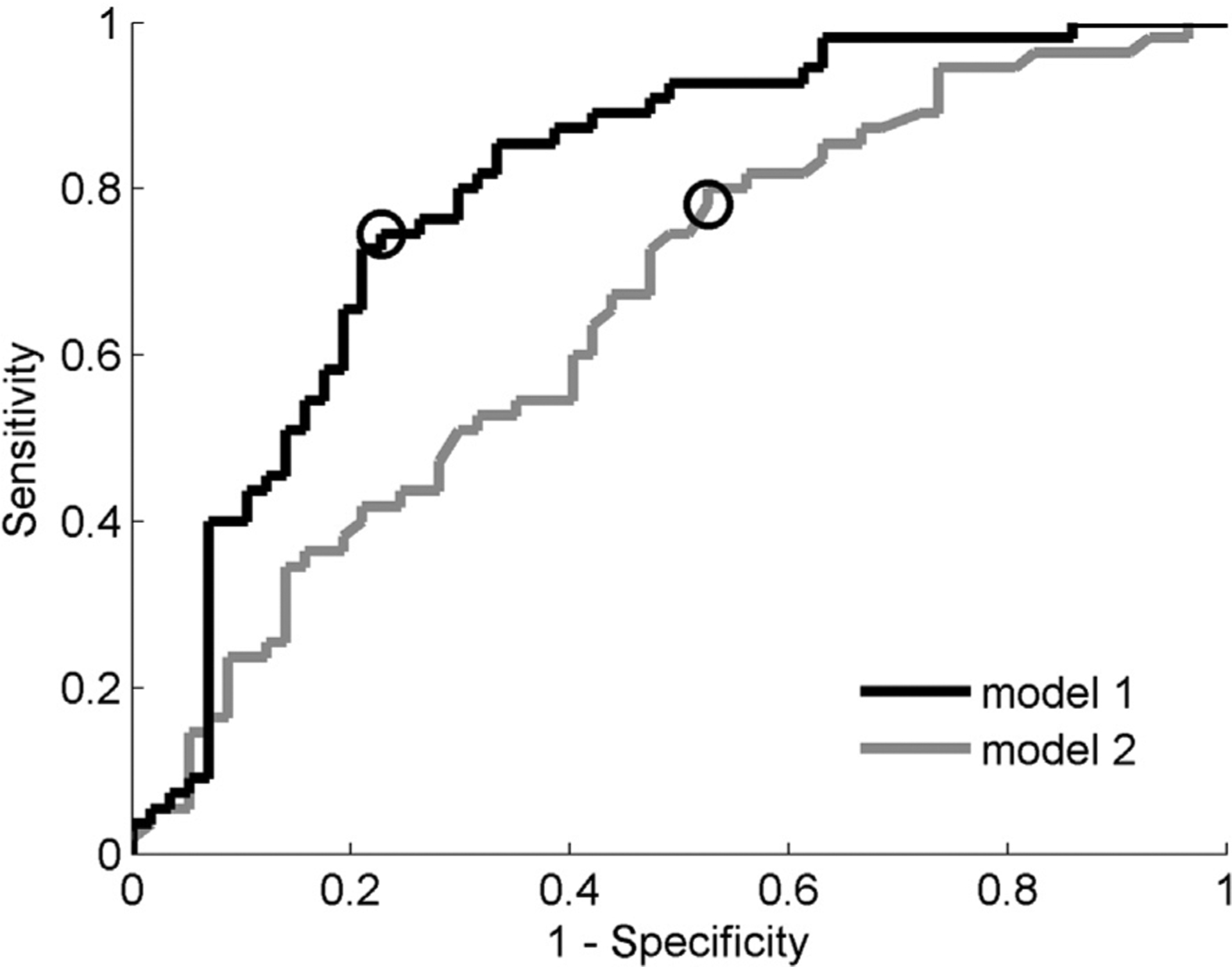

The best slip-induced fall prediction model was based on the right thigh angle at TD, the right limb maximum GRF in the AP and vertical directions in post-TD, and the momentum change from TD to LO (p < .05 for all, model 1 in Table 3). The AUC was 0.802 (Fig. 1) and the highest predictive ability was 75.9% (specificity: 77.2%, sensitivity: 74.5%, Table 4) at the optimal cutoff of 49.2%.

Table 3.

The components of predictive models using multivariate logistic regression (backward stepwise method). Model 1 only contains gait characteristics with p < .05, while model 2 only contains clinical and demographic measures with p < .05. The odds ratio indicates the factor by which the fall probability increases with a decrease of 1SD in the variable across all subjects.

| Model | Independent variables | p value | SE | Odds Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1* | R thigh angle at TD | 0.016 | 2.218 | 1.9 |

| R AP GRF after TD | 0.007 | 0.993 | 4.56 | |

| R VT GRF after TD | 0.005 | 0.266 | 0.19 | |

| MMT from TD to LO | 0.004 | 0.033 | 0.37 | |

| 2 | Weight | 0.028 | 0.014 | 1.57 |

| Fall history | 0.047 | 0.402 | 1.48 |

The equation for this model is: p(fall) = 1/(1 + exp(6.44 + 5.36 × R-thigh-angle + 2.66 × R-AP-GRF − 0.75 × R-VT-GRF − 0.09 × MMT)).

TD: Right touchdown; LO: Left lift off; AP: anteroposterior; VT: vertical; and SE: standard error.

Fig. 1.

Receiver operating curves (ROC) for the two fall prediction models. The areas under the curves (AUC) for these models are 80.2 and 60.5, respectively. The circle marker denotes the optimal cutoff for each model, the optimal cutoff for model 1 is 49.2% (specificity: 77.2%, sensitivity: 74.5%), and the optimal cutoff for model 2 is 56.9% (specificity: 47.4%, sensitivity: 78.2%). Specificity denotes recovery prediction and sensitivity denotes fall prediction.

Table 4.

Specificity, sensitivity, overall accuracy, and likelihood ratio of slip outcome for the models in Table 3. The specificity and sensitivity was calculated at optimal cutoff (shown in Fig. 1), specificity denotes recovery prediction and sensitivity denotes fall prediction.

| Model | Spe | 95%CI | Sen | 95%CI | Ace | Likelihood Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 77.2 | 66–88 | 74.5 | 63–86 | 75.9 | 3.27 |

| 2 | 47.4 | 34–60 | 78.2 | 67–89 | 62.5 | 1.49 |

Spe: specificity in percentage; Sen: sensitivity in percentage; Acc: overall accuracy in percentage.

Among the clinical and demographic measures, only body weight and fall history contributed to fall prediction, and the overall prediction accuracy was 62.5% (model 2 in Table 4). Although sensitivity (fall prediction) of this model increased by ~3.7% compared to model 1, its specificity (47.4%) was much lower than model 1. A combined model including variables from model 1 and model 2 yielded identical results to model 1 and, hence, was not presented in Table 4.

4. Discussion

In this study, the reproduction of actual falls from an unexpected overground slip was used to determine the association between slip-induced falls and demographic characteristics, clinical balance scales, and gait parameters in natural walking. Our results indicated that, of the descriptive characteristics and clinical balance scales, body weight was the only measure which could predict slip outcome with greater than 60% accuracy. While for gait parameters, step length, COM relative position at TD, momentum change from TD to LO, right thigh angle and angular velocity at TD, all demonstrated greater than 60% prediction accuracy. The best slip-induced fall prediction model comprised of the right thigh angle at TD, the right limb GRF in both AP and ML directions, and the momentum change from TD to LO, and it predicted 74.5% of falls and 77.2% of recoveries. Conversely, the model based on clinical and demographic measures could only predict 78.2% of falls and 47.4% of recoveries.

4.1. Fall prediction based on a single predictor

Contrary to previous results (Viccaro et al., 2011; Zakaria et al., 2015), we found neither gait speed, TUG, nor fall history were associated with slip-induced fall-risk. One of the major factors leading to this distinction might be the difference in fall types included in our study compared to previous studies. Although a slow gait could lead to instability upon encountering a slip, such instability might be offset by an associated decrease in step length, suggesting gait speed might not be related to slip-induced fall-risk (Espy et al., 2010a). Conversely, gait speed is a key determinant for prediction of trip-induced falls, with a faster (+0.161 m/s) gait speed found to increase likelihood of falls by 256% following a trip (Pavol et al., 1999). Therefore, results of studies which included all fall types might be affected by the rate of each fall type. For example, a study might demonstrate a significant effect of gait speed on fall-risk when participants experienced more trip-induced falls compared to those experiencing more slip-induced falls, leading to disparities in the literature. This may explain findings from several studies which suggested no relationship between gait speed and fall-risk (Brach et al., 2005; Rispens et al., 2015).

According to our results, fall history alone could not predict risk of slip-induced falls, although previous studies described fall history as a strong predictor of future falls (Edwards et al., 2011; Toebes et al., 2012). This could be due to the fact that retrospective fall incidence data collection was not fall-specific. However, after combining participants’ fall history with body weight, fall history became statistically significant for fall prediction, indicating that, as a predictor, fall history might only be suitable for specific individuals with higher or lower body weight.

Besides fall type differences, differences in functional mobility status of participants could also contribute to these distinctions. Previous studies proposed TUG score could identify individuals at risk of falling with a threshold of ~15 s (Gietzelt et al., 2009; Zakaria et al., 2015). However, none of our participants were beyond this 15 s threshold (Table 1), yet ~50% of them failed to recover their balance upon an unexpected slip, indicating that TUG might have a ceiling effect with the test failing to identify fallers among elderly individuals with normal mobility. Additionally, one of the principal variables influencing TUG results is walking speed, which, according to our results, is not a factor significantly impacting slip-induced fall-risk. Moreover, it can be argued that normal functional mobility shown by performance of volitional tasks (self-generated perturbation) might not necessarily indicate effective reactive balance control, which is required for successful recovery from an unannounced slip. In line with our results, Beauchet et al proposed that predictive ability of the TUG test for future falls was limited and TUG performance was only associated with fall history (Beauchet et al., 2011).

Fall prediction analysis showed COM relative position at TD could predict 63.4% of slip outcomes (Table 2), while COM relative velocity at TD was not related to slip outcomes. Both of these variables are constituents of a dynamic gait stability measure which could predict slip outcomes with a certainty of 62% (Bhatt et al., 2011). However, it has been shown that COM relative position at TD has a significantly greater correlation with dynamic stability than COM relative velocity (Yang and Pai, 2013). This could explain why COM relative velocity was not a significant predictor. Further, COM velocity is closely related to gait speed (Espy et al., 2010b) which was also not a significant predictor. Other variables such as step length, thigh angle, and shank angular velocity also individually demonstrated only moderate overall accuracy, which is consistent with previous studies (Espy et al., 2010a; Verghese et al., 2009). These findings could be attributed to the biomechanical association of these variables with dynamic stability, thereby influencing fall-risk. For example, shorter step length and smaller right thigh angle (more vertical), could all shorten the distance from the COM to the slipping foot, hence lowering the likelihood of a fall upon slipping. Moreover, a smaller right shank swing velocity results from a larger knee flexor moment (to decelerate the knee extension), which could decrease slip intensity, resulting in a greater possibility of recovery (Yang and Pai, 2010).

Of these parameters, linear momentum change from TD to LO demonstrated the best prediction accuracy for slip outcomes (Tables 2), as a sufficient momentum could displace the COM forward from its current position to catch up with the forward moving base-of-support during a slip (Bhatt et al., 2005). To maintain that forward momentum, sufficient and timely counterbalancing joint moments need to be generated (Liu and Lockhart, 2009). A larger decrease in linear momentum from TD to LO might reflect an age-related decline in voluntary muscle strength or the rate of muscle force production, thereby increasing the likelihood of slip-induced falls (Doherty, 2001).

4.2. Fall prediction based on multiple predictors

The best fall prediction model based on gait parameters involved right thigh angle at TD, right GRF in both AP and vertical directions, and the momentum change from TD to LO (model 1). The AUC (0.802) and the overall prediction accuracy (75.9%) of this model were significantly higher than those seen in other fall-risk prediction studies (Bhatt et al., 2011; Paterson et al., 2011; Sterke et al., 2012; van Schooten et al., 2015). As previously mentioned, the thigh angle was related to dynamic stability, and momentum change was related to the necessary joint moments. While the vertical GRF was related to the limb support against gravity, which is also a key factor affecting slip outcomes (Yang et al., 2011), the GRF in AP direction was actually the braking force which directly determined slipping intensity and fall-risk (Bhatt et al., 2006). Consistent with previous studies, the best model based on demographic characteristics and clinical balance scales only predicted slip outcomes with an overall accuracy of 62.5%, and these variables could not further improve predictive ability when added to the gait parameter model. Thus, these results indicate that gait parameters could significantly increase fall-prediction compared to the gold-standard clinical balance measures (Bhatt et al., 2011; Greene et al., 2010) and known demographic fall-risk predictors (body weight and fall history) (Edwards et al., 2011; Toebes et al., 2012).

Our findings could have significant clinical implications with regards to fall prevention. Besides providing a higher prediction accuracy of slip-induced fall-risk, a specific fall-risk model could also provide information about the type of future fall one is susceptible to with regards to impact location and/or the potential fracture type they could experience (Nevitt et al., 1993; Smeesters et al., 2001). Using this kind of model, at-risk individuals could wear a precautionary protective device (i.e. wrist guide and wearable airbag) to prevent specific injury or fracture (Kim et al., 2006; Tamura et al., 2009). Furthermore, a targeted fall prevention protocol could be more effective for training individuals at high-risk for a specific fall type (Healey et al., 2004). For example, slip training could be used for individuals at risk of slip-induced fall (Pai and Bhatt, 2007), while for individuals at risk of trip-induced fall, trip training could be helpful (Rosenblatt et al., 2013).

In contrast to previous models (Hausdorff et al., 2001; Liu et al., 2012), model 1 in this study was based on easily alterable gait kinetic and kinematic parameters, thus, it is reasonable to postulate that older adults could decrease their risk for slip-induced falls by adjusting their regular gait pattern. For example, individuals could maintain their forward momentum and also increase their chances for execution of an effective recovery step by controlling their thigh angle at TD to shorten the distance between COM and leading foot. Such a strategy would help shif their COM immediately towards the leading foot to weaken the braking force and enhance the vertical support force on the leading limb after TD, and hence generating a larger push-off force with the trailing limb (Pijnappels et al., 2005). Our results suggest that, during an unexpected slip, proper placement of the leading foot could reduce slip intensity, and proper placement of the trailing foot could rebuild the base-of-support as well as enhance limb support, resulting in a lower fall-risk. Therefore, protocols for improving control of foot placement, such as Tai-Chi, step training, and perturbation training (Nnodim et al., 2006; Pai et al., 2014a; Park et al., 2016), could be helpful for at-risk individuals.

The current study successfully developed a slip-induced fall prediction model based on healthy older adults’ normal gait pattern and compared its predictive capacity with the one based on clinical and demographic measures. The results could potentially be limited by slips delivered always on the right leg as the dominant leg could be different between participants which could modify some outcome variables. However, given that within the large sample size included, there were only four left-dominant participants, it is reasonable to conclude that our results can be generalized to older adult population. Furthermore, individuals might have possibly adjusted their gait pattern in preparation for the upcoming slip, hence future studies should collect electromyography data to examine any proactive changes occurring prior to slip onset (Mueller et al., 2018). Finally, the cost of implementation of our model would be higher than the traditional clinical and demographic models, however, the variables included in our model could be easily measured using wearable sensors (Liu et al., 2010; O’Donovan et al., 2007; Tanaka et al., 2004; Yeoh et al., 2008). For example, an inertial sensor system could provide joint angle and velocity data during gait, while the force data could be collected by GRF sensors using specialized footwear. Moreover, there is an increasing use of wearable motion systems in clinical practice and research due to its portability and user-friendliness. Further it is expected that commercially available wearable systems would become more cost-efficient in the future (Fletcher et al., 2010; Soh et al., 2015).

In conclusion, we found the gait parameter model was able to provide a higher predictive accuracy than previous slip-induced fall-risk models. The findings of this study are significant as they have the potential to enhance preventive interventions for individuals at high-risk for slip-induced falls and contribute towards development of specific therapeutic strategies for fall prevention.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH R01 AG050672-02 (awarded to Tanvi Bhatt). We thank Ms. Alison Schenone for her help editing this manuscript.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest with the work presented.

References

- Ashburn A, Stack E, Pickering RM, Ward CD, 2001. Predicting fallers in a community-based sample of people with Parkinson’s disease. Gerontology 47, 277–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautmans I, Jansen B, Van Keymolen B, Mets T, 2011. Reliability and clinical correlates of 3D-accelerometry based gait analysis outcomes according to age and fall-risk. Gait Posture 33, 366–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchet O, Fantino B, Allali G, Muir SW, Montero-Odasso M, Annweiler C, 2011. Timed up and go test and risk of falls in older adults: a systematic review. J. Nutr. Health Aging 15, 933–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt T, Espy D, Yang F, Pai YC, 2011. Dynamic gait stability, clinical correlates, and prognosis of falls among community-dwelling older adults. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehab 92, 799–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt T, Wening JD, Pai YC, 2005. Influence of gait speed on stability: recovery from anterior slips and compensatory stepping. Gait Posture 21, 146–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt T, Wening JD, Pai YC, 2006. Adaptive control of gait stability in reducing slip-related backward loss of balance. Exp. Brain Res 170, 61–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyé ND, Van Lieshout EM, Van Beeck EF, Hartholt KA, Van der Cammen TJ, Patka P, 2013. The impact of falls in the elderly. Trauma 15, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Brach JS, Berlin J, VanSwearingen J, Newman A, Studenski S, 2005. Too much or too little step width variability is associated with a fall history only in older persons who walk at or near normal gait speed. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc 53, S133–S134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns ER, Stevens JA, Lee R, 2016. The direct costs of fatal and non-fatal falls among older adults – United States. J. Safety Res 58, 99–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cham R, Redfern MS, 2002. Heel contact dynamics during slip events on level and inclined surfaces. Safety Sci. 40, 559–576. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty TJ, 2001. The influence of aging and sex on skeletal muscle mass and strength. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr 4, 503–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards MH, Jameson K, Denison H, Sayer AA, Cooper C, Dennison E, 2011. Clinical risk factors, bone mineral density and fall history in the prediction of incident fracture among men and women. Rheumatology 50. 73–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espy DD, Yang F, Bhatt T, Pai YC, 2010a. Independent influence of gait speed and step length on stability and fall risk. Gait Posture 32, 378–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espy DD, Yang F, Pai YC, 2010b. Control of center of mass motion state through cuing and decoupling of spontaneous gait parameters in level walking. J. Biomech 43, 2548–2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher RR, Poh MZ, Eydgahi H, 2010. Wearable sensors: opportunities and challenges for low-cost health care. Conf. Proc. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc 2010, 1763–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates S, Smith LA, Fisher JD, Lamb SE, 2008. Systematic review of accuracy of screening instruments for predicting fall risk among independently living older adults. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev 45, 1105–1116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gietzelt M, Nemitz G, Wolf KH, Schwabedissen HMZ, Haux R, Marschollek M, 2009. A clinical study to assess fall risk using a single waist accelerometer. Inform. Health Soc. Ca 34, 181–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene BR, O’Donovan A, Romero-Ortuno R, Cogan L, Scanaill CN, Kenny RA, 2010. Quantitative falls risk assessment using the timed up and go test. IEEE Trans. Bio-Med. Eng 57, 2918–2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausdorff JM, Rios DA, Edelberg HK, 2001. Gait variability and fall risk in community-living older adults: A 1-year prospective study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehab 82, 1050–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healey F, Monro A, Cockram A, Adams V, Heseltine D, 2004. Using targeted risk factor reduction to prevent falls in older in-patients: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing 33, 390–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heijnen MJH, Rietdyk S, 2016. Falls in young adults: perceived causes and environmental factors assessed with a daily online survey. Hum. Movement Sci 46, 86–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoang OTT, Jullamate P, Piphatvanitcha N, Rosenberg E, 2017. Factors related to fear of falling among community-dwelling older adults. J. Clin. Nurs 26, 68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kangas M, Vikman I, Nyberg L, Korpelainen R, Lindblom J, Jamsa T, 2012. Comparison of real-life accidental falls in older people with experimental falls in middle-aged test subjects. Gait Posture 35, 500–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KJ, Alian AM, Morris WS, Lee YH, 2006. Shock attenuation of various protective devices for prevention of fall-related injuries of the forearm/hand complex. Am. J. Sport Med 34, 637–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lannering C, Bravell ME, Midlov P, Ostgren CJ, Molstad S, 2016. Factors related to falls, weight-loss and pressure ulcers - more insight in risk assessment among nursing home residents. J. Clin. Nurs 25, 940–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Lockhart TE, 2009. Age-related joint moment characteristics during normal gait and successful reactive-recovery from unexpected slip perturbations. Gait Posture 30, 276–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Zhang X, Lockhart TE, 2012. Fall risk assessments based on postural and dynamic stability using inertial measurement unit. Safety Health Work 3, 192–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T, Inoue Y, Shibata K, 2010. A wearable ground reaction force sensor system and its application to the measurement of extrinsic gait variability. Sensors-Basel 10, 10240–10255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki BE, 1997. Gait changes in older adults: Predictors of falls or indicators of fear? J. Am. Geriatr. Soc 45, 313–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbourou GA, Lajoie Y, Teasdale N, 2003. Step length variability at gait initiation in elderly fallers and non-fallers, and young adults. Gerontology 49, 21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer BE, Chambers AJ, Redfern MS, Cham R, 2006. Gait parameters as predictors of slip severity in younger and older adults. Ergonomics 49, 329–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller J, Martinez-Valdes E, Stoll J, Mueller S, Engel T, Mayer F, 2018. Differences in neuromuscular activity of ankle stabilizing muscles during postural disturbances: a gender-specific analysis. Gait Posture 61, 226–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy MA, Olson SL, Protas EJ, Overby AR, 2003. Screening for falls in community-dwelling elderly. J. Aging Phys. Activ 11, 66–80. [Google Scholar]

- Nevitt MC, Cummings SR, Black D, Genant HK, Arnaud C, Browner W, Faulker K, Fox C, Gluer C, Harvey S, Hulley SB, Palermo L, Seeley D, Steiger P, Jergas M, Sherwin R, Scott J, Fox K, Lewis J, Bahr M, Trusty S, Hohman B, Emerson L, Rebar D, Oliner E, Ensrud K, Grimm R, Bell C, Thomas D, Jacobson K, Jackson S, Mitson E, Stocke L, Frank P, Cauley JA, Kuller LH, Harper L, Nasim M, Bashada C, Buck L, Githens A, Medve D, Rudovsky S, Vogt TM, Vollmer VM, Glauber H, Orwoll E, Blank J, Mastelsmith B, Bright R, Downing J, 1993. Type of fall and risk of hip and wrist fractures – the study of osteoporotic fractures. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc 41, 1226–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nnodim JO, Strasburg D, Nabozny M, Nyquist L, Galecki A, Chen S, Alexander NB, 2006. Dynamic balance and stepping versus tai chi training to improve balance and stepping in at-risk older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc 54, 1825–1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donovan KJ, Kamnik R, O’Keeffe DT, Lyons GM, 2007. An inertial and magnetic sensor based technique for joint angle measurement. J. Biomech 40, 2604–2611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai YC, Bhatt T, Yang F, Wang E, 2014a. Perturbation training can reduce community-dwelling older adults’ annual fall risk: a randomized controlled trial. J. Gerontol. A – Biol 69, 1586–1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai YC, Bhatt TS, 2007. Repeated-slip training: An emerging paradigm for prevention of slip-related falls among older adults. Phys. Ther 87, 1478–1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai YC, Yang F, Bhatt T, Wang E, 2014b. Learning from laboratory-induced falling: long-term motor retention among older adults. Age 36, 1367–1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park GD, Choi JU, Kim YM, 2016. The effects of multidirectional stepping training on balance, gait ability, and falls efficacy following stroke. J. Phys. Ther. Sci 28, 82–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson K, Hill K, Lythgo N, 2011. Stride dynamics, gait variability and prospective falls risk in active community dwelling older women. Gait Posture 33, 251–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil R, Uusi-Rasi K, Kannus P, Karinkanta S, Sievanen H, 2014. Concern about falling in older women with a history of falls: associations with health, functional ability, physical activity and quality of life. Gerontology 60, 22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavol MJ, Owings TM, Foley KT, Grabiner MD, 1999. Gait characteristics as risk factors for falling from trips induced in older adults. J. Gerontol. A – Biol 54, M583–M590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pijnappels M, Bobbert MF, van Dieen JH, 2005. Push-off reactions in recovery after tripping discriminate young subjects, older non-falters and older fallers. Gait Posture 21, 388–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rispens SM, van Schooten KS, Pijnappels M, Daffertshofer A, Beek PJ, van Dieen JH, 2015. Identification of fall risk predictors in daily life measurements: gait characteristics’ reliability and association with self-reported fall history. Neurorehab. Neural Re 29, 54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt NJ, Marone J, Grabiner MD, 2013. Preventing trip-related falls by community-dwelling adults: a prospective study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc 61, 1629–1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott V, Votova K, Scanlan A, Close J, 2007. Multifactorial and functional mobility assessment tools for fall risk among older adults in community, home-support, long-term and acute care settings. Age Ageing 36, 130–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeesters C, Hayes WC, McMahon TA, 2001. Disturbance type and gait speed affect fall direction and impact location. J. Biomech 34, 309–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeesters C, Hayes WC, McMahon TA, 2007. Determining fall direction and impact location for various disturbances and gait speeds using the articulated total body model. J. Biomech. Eng. – Trans. Asme 129, 393–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soh PJ, Vandenbosch GAE, Mercuri M, Schreurs DMMP, 2015. Wearable wireless health monitoring. IEEE Microw. Mag 16, 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Stel VS, Smit JH, Pluijm SMF, Lips P, 2004. Consequences of falling in older men and women and risk factors for health service use and functional decline. Age Ageing 33, 58–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterke CS, van Beeck EF, Looman CWN, Kressig RW, van der Cammen TJM, 2012. An electronic walkway can predict short-term fall risk in nursing home residents with dementia. Gait Posture 36, 95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens JA, Sogolow ED, 2005. Gender differences for non-fatal unintentional fall related injuries among older adults. Injury Prev. 11, 115–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura T, Yoshimura T, Sekine M, Uchida M, Tanaka O, 2009. A wearable airbag to prevent fall injuries. IEEE Trans. Inf. Technol. B 13, 910–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka S, Motoi K, Nogawa M, Yamakoshi K, 2004. A new portable device for ambulatory monitoring of human posture and walking velocity using miniature accelerometers and gyroscope. Conf. Proc. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc 3, 2283–2286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor ME, Delbaere K, Mikolaizak AS, Lord SR, Close JCT, 2013. Gait parameter risk factors for falls under simple and dual task conditions in cognitively impaired older people. Gait Posture 37, 126–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timsina LR, Willetts JL, Brennan MJ, Marucci-Wellman H, Lombardi DA, Courtney TK, Verma SK, 2017. Circumstances of fall-related injuries by age and gender among community-dwelling adults in the United States. PLoS One 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toebes MJP, Hoozemans MJM, Furrer R, Dekker J, van Dieen JH, 2012. Local dynamic stability and variability of gait are associated with fall history in elderly subjects. Gait Posture 36, 527–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Schooten KS, Pijnappels M, Rispens SM, Elders PJM, Lips P, van Dieen JH, 2015. Ambulatory fall-risk assessment: amount and quality of daily-life gait predict falls in older adults. J. Gerontol. A – Biol 70, 608–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verghese J, Holtzer R, Lipton RB, Wang CL, 2009. Quantitative gait markers and incident fall risk in older adults. J. Gerontol. A – Biol 64, 896–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viccaro LJ, Perera S, Studenski SA, 2011. Is timed up and go better than gait speed in predicting health, function, and falls in older adults? J. Am. Geriatr. Soc 59, 887–892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voermans N, Snijders A, Schoon Y, Bloem B, 2007. Why old people fall (and how to stop them). Pract. Neurol 7, 158–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter DA, 1989. CNS strategies in human gait: implication for FES control. Automedica 11, 163–174. [Google Scholar]

- Yang F, Anderson FC, Pai YC, 2008. Predicted threshold against backward balance loss following a slip in gait. J. Biomech 41, 1823–1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F, Bhatt T, Pai YC, 2011. Limits of recovery against slip-induced falls while walking. J. Biomech 44, 2607–2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F, Pai C, 2013. Alteration in community-dwelling older adults level walking following perturbation training. J. Biomech 46, 2463–2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F, Pai YC, 2011. Automatic recognition of falls in gait-slip training: harness load cell based criteria. Journal of Biomechanics 44 (12), 2243–2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F, Pai YC, 2010. Role of individual lower limb joints in reactive stability control following a novel slip in gait. J. Biomech 43, 397–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F, Pai YC, 2014. Can sacral marker approximate center of mass during gait and slip-fall recovery among community-dwelling older adults? J. Biomech 47, 3807–3812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeoh WS, Pek I, Yong YH, Chen X, Waluyo AB, 2008. Ambulatory monitoring of human posture and walking speed using wearable accelerometer sensors. Conf. Proc. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc 2008, 5184–5187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakaria NA, Kuwae Y, Tamura T, Minato K, Kanaya S, 2015. Quantitative analysis of fall risk using TUG test. Comput. Method Biomec 18, 426–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]