Abstract

Background

Nursing education is an important part of the “9+3” vocational education program led by Sichuan Province. In the internship stage, nursing students of Tibetan ethnicity may have problems of intercultural adaptation in the process of getting along with patients, which may affect the effective nursing outcome. The purpose of this study was to clarify the current situation of transcultural adaptation of Tibetan trainee nurses and to provide more theoretical support and guidance.

Material/Methods

We collected 237 valid survey questionnaires, based on Ward’s acculturation process model, from a total of 363 Tibetan trainee nurses in the “9+3” free vocational education program in Chengdu, Luzhou, and Nanchong of Sichuan Province. The SPSSAU project (2020), an online application software retrieved from https://www.spssau.com, was used for data coding and archiving.

Results

The results of questionnaire and data analysis showed that the overall level of transcultural adaptation of Tibetan trainee nurses was that the number of people with poor adaptation was slightly higher than those with good adaptation, and most Tibetan trainee nurses were in the middle level. Meanwhile, sociocultural adaptation was better than psychological adaptation. There were no statistically significant differences among the 4 grouping variables: gender, student home region, the city where the internship hospital was located, and whether they were from a single-child family or not.

Conclusions

The results revealed that there was still transcultural maladjustment among Tibetan nurses in the internship stage, and the psychological maladjustment was more obvious than the sociocultural maladjustment. We provide countermeasures and suggestions to solve the problems of transcultural adaptation reflected in the research.

Keywords: Acculturation; Adaptation, Psychological; Transcultural Nursing; Ethnopsychology; Practice Patterns, Nurses’

Background

China is a multi-ethnic and multicultural country [1]. Tibetans are an ethnic minority peculiar to China [1]. The Tibetan areas have a special political and strategic position in China because of historical reasons [2]. Speeding up the economic and educational development of Tibetan areas, maintaining stability, and improving people’s livelihood in Tibetan areas are of far-reaching significance to safeguarding China’s national unity [2].

As the second largest Tibetan area in China, Sichuan has 32 Tibetan counties, covering an area of 0.25 million square kilometers, accounting for 52% of the province’s total area, with a population of 1.962 million, including 1.243 million Tibetans, accounting for 63.4% of the total population of the Tibetan area [3].

To improve the economic and educational development of Tibetan areas, Sichuan Province officially launched the “9+3” Tibetan free vocational education program in March 2009 [4]. It is one of the “major livelihood projects” implemented by the Sichuan Provincial government [5]. The “9+3” free vocational education program refers to organizing 10 000 graduates who have completed 9 years of vocational education (including primary and junior high school education) in Tibetan areas to receive 3 years of free vocational education in the developed hinterland cities, so as to train talents who combine high-quality skilled labor with higher scientific and technological quality [5]. The implementation of the “9+3” free education program, relying on the hinterland to rapidly promote the development of the quality of the Tibetan population, was not only related to people’s livelihood, stability, and development, but also highlighted the public welfare value of vocational education [6].

However, the cultural traditions and living habits of Tibetan and Han nationality are different [7]. Adolescence is an important turning point for individuals from childhood to maturity, and it is also the stage in which individuals are most prone to social maladjustment [8]. The social adaptation of teenagers is not only related to the healthy development of their own psychology, but also affects interpersonal harmony and social stability [9,10]. Various cultural contradictions and conflicts will have an unavoidable impact on the personality development and stereotyping of teenagers [11]. When Tibetan students leaved Tibet to study in the hinterland and enter a city with a different culture and life from their own, they may have conflicts with Han students because of their different living habits and hobbies, and may even lead them to commit crime because of their sense of loneliness and inferiority complex [12]. Therefore, it is necessary to study their psychological characteristics in this period, find the problems in time, and solve them in time. This is also a Han’s prerequisite for Tibetan students in Sichuan to adapt to society [13].

Nursing education is an important part of “9+3” free teaching. Nursing is an important, therapeutic, and interpersonal process. The nurse-patient relationship can be thought of as one that helps the person cared for [14]. Nurses need to understand the following factors through nurse-patient communication and experience exchange: the patient’s life experience and disease, the impact of the disease on the patient, and the patient’s health expectations [15]. Satisfactory patient-care outcomes result from the nurse’s understanding of the patient’s life experience and ability to provide care that meets the patient’s health expectations [16]. However, cultural differences may lead to ineffective nurse-patient communication [16]. Nurses may have difficulty understanding the feelings of patients, and have difficulty establishing a relationship of trust with patients, leading to low patient satisfaction and increased medical disputes, which in turn adversely affect nurses’ work and mental state [16]. Therefore, ensuring that nurses have effective interaction skills is critical to improving patient satisfaction and positive care outcomes.

“9+3” Tibetan trainee nurses come from areas where the Tibetan culture and the Tibetan language predominate. Regional and cultural differences give rise to the problem that interns have in transcultural adaptation.

Ward, a New Zealand psychologist, proposed that the problem of transcultural adaptation can be mainly examined from 2 dimensions: the social level and the individual level [17]. The influencing factors at the social level included birth society and guest society; the factors at the individual level included individual characteristics and emotional characteristics [18]. On the other hand, these influencing factors, which existed at the social and individual level, would be reflected in the emotional, behavioral, and cognitive aspects of the participants [18]. At present, Ward’s “acculturation process model” is recognized as a comprehensive and systematic theoretical model for the study of intercultural adaptation [19].

In the past few years, research on nursing students’ transcultural adaptation has mainly consisted of single-center studies and the conclusions were mostly that there was maladjustment [20,21]. In addition, the literature on Tibetan nurses as a specific research group was mainly concentrated 5 years ago, and the studies rarely involved nurses in the internship stage [22,23].

In order to clarify the current situation of transcultural adaptation of Tibetan nursing trainees, this study selected Tibetan nursing trainees in Chengdu, Luzhou, and Nanchong to investigate their cross-cultural adaptation. A questionnaire survey based on Ward’s acculturation process model was used to investigate the intercultural adaptation of Tibetan nursing trainees. After achieving an in-depth understanding of the current situation of intercultural adaptation of Tibetan students, it is hoped that this paper can provide more theoretical support and guidance for the cultivation of intercultural adaptation of Tibetan and other ethnic minority youth in China.

Material and Methods

Research Design

Based on Ward’s acculturation process model, transcultural adaptation was divided into 2 dimensions of adaptations (sociocultural and psychological) [24]. The questionnaire on transcultural adaptation of Tibetan nursing trainees in this study included 46 items and the following constructs: 1) Q1 to Q4 referred to basic information of the respondents, such as gender, student home region, whether they were the only child or not, and the administrative level of the city where the trainee internship hospital was located (Table 1, Supplementary Table 1); 2) Q5 to Q26 referred to sociocultural adaptation, according to Wang’s questionnaire on Sociocultural adaptation [25], which was divided into 3 levels: life adaptation (including Q5, Q6, and Q7), interpersonal adaptation (including Q8, Q9, Q10, Q11, Q12, Q13, Q14, and Q15)and work adaptation (including Q16, Q17, Q18, Q19, Q20, Q21, Q22, Q23, Q24, Q25, and Q26), using a 5-point Likert scale (Supplementary Table 1). “Strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” were counted as 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 points in sequence; 3) Q27 to Q46 referred to psychological adaptation, based on the SDS questionnaire scale, using a 4-point Likert scale, which reflected 4 groups of specific symptoms of depressive state: psychosomatic symptoms (including Q27 and Q29), somatic disorders (including Q28, Q30, Q31, Q32, Q33, Q34, Q35, and Q36), psychomotor disorders (including Q38 and Q39), and depressive psychological disorders (including Q37, Q40, Q41, Q42, Q43, Q44, Q45, and Q46) (Supplementary Table 1). A value of 1, 2, 3, and 4 was assigned to a response depending upon whether the item was worded positively or negatively.

Table 1.

Composition of the object.

| Gender | Student source region | One-child family | City administration level where the internship hospital was located | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Urban | Rural or grazing district | Urban rural fringe area | Yes | No | Provincial capital city | Prefecture level city | County level City | Rural area |

| 222 (93.67%) | 15 (6.33%) | 197 (83.12%) | 27 (11.39%) | 13 (5.49%) | 51 (21.52%) | 186 (78.48%) | 36 (15.19%) | 161 (67.93%) | 38 (16.03%) | 2 (0.84%) |

| N=237 | N=237 | N=237 | N=237 | |||||||

For items Q27, Q29, Q30, Q33, Q34, Q35, Q36, Q39, Q41, and Q45 the scoring was:

A little of the time=1

Some of the time=2

A good part of the time=3

Most of the time=4

Items Q28, Q31, Q32, Q37, Q38, Q40, Q42, Q43, Q44, and Q46 were reverse-scored as follows:

A little of the time=4

Some of the time=3

A good part of the time=2

Most of the time=1

Data Collection

The questionnaire was distributed online through “Questionnaire Star”, a small program of “WeChat”, completed by mobile phone input.

Questionnaire Star is a professional online questionnaire survey, evaluation, and voting platform, which has powerful functions and can provide a series of services such as online questionnaire design, data collection, custom reports, academic research, and survey result analysis.

The basic steps for generating electronic questionnaires from questionnaire stars were as follows [26]:

Register account and login. Open the “questionnaire Star” website (https://www.sojump.com/), click “Registration” on the home page and set the password to complete the registration as a member, and log in with the registered user name.

Online design questionnaire. Click “Create a new questionnaire”, enter the interface, select “B Import questionnaire text” to copy the finished Word electronic document into the edit box. Informed consents for inclusion were attached to the questionnaire to inform about the aim and the methodology of this study and privacy protection measures.

Confirm and release questionnaires. After confirming that the questionnaire was correct, to clicked “Finish Editing” – “Publish Questionnaire”. Then, the generated QR code was sent to invite others to fill in the questionnaire through “WeChat” (a social software app).

Recycled questionnaire and result analysis. Click “Statistics and Analysis” to view the answers to the questionnaire. Once the survey was complete, the report can be downloaded and put into further analysis.

Research Participants

The sample size was calculated according to a minimum of 5 times the number of scale items for questionnaire [16]. At least 230 valid questionnaires were required for total 46 items of the study to meet the requirement. Considering an unreturned rate of 20%, a stratified proportional random sampling technique was employed, with departments used as the strata for randomly selecting 290 Tibetan practice nurses (80% for each stratum) from total 363 Tibetan nurses in clinical practice stage of “9+3” free vocational education in Chengdu, Luzhou, and Nanchong of Sichuan Province. In the end, of the 290 questionnaires disseminated, 237 were returned valid (81.72%); thus, the requirements of sample size were met.

Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Affiliated Hospital of North Sichuan Medical College Ethics Committee [No.2020ER(A)030]. All participants gave their informed consent before they participated in the study.

Data Analysis

After the questionnaire data were collected, the SPSSAU project (2020), an online application software retrieved from https://www.spssau.com, was used to data coding and archiving. Descriptive statistical analyses were performed to analyze the demographic characteristics of the nursing students. There were 3 major steps for performing analysis of intercultural adaptation:

Reliability testing. The internal consistency was estimated with Cronbach’s alpha. A value of 0.70 or above means good factor consistency [27]. Corrected Item-Total Correlation (CITC) was used to test whether each of the items contributes to the measurement of implicit rationing as a whole, and values of 0.20 and lower were unexpected [28].

Validity testing. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used for testing the construct validity of the instrument [29]. Bartlett’s sphericity test and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin index (KMO) were implemented before the factor analysis. The principal component analysis (PCA) method combined with varimax rotation technique was then used to explore the interrelationship of variables. Kaiser criteria for the extraction of factors and scree plot criterion based on eigenvalues were used to determine the number of emerging factors. It was considered practically significant to use the criterion of eigenvalue ≥1 and factor loadings ≥0.45.

Statistical analysis of the overall level and classification of intercultural adaptation. In the study on the overall level of intercultural adaptation, the Z-score was used for data statistics, with 0 as the cut-off point. Those with a Z-score below 0 were considered poor adaptation, while those with a Z-score above 0 were considered good adaptation. The t test or F test was used for statistical analysis for classification of intercultural adaptation. The P value was set as <.05, which indicates statistical significance.

Results

Composition of the Object

The sample composition of the questionnaire is shown in Table 1. The baseline data of the respondents were classified and counted according to gender, student home region, whether they were the only child, and the city administration level where the internship hospital was located. Among them, there were 15 males, accounting for 6.33%; 222 women, accounting for 93.67%; 27 people from rural or pastoral areas, accounting for 11.39%; 197 people from urban areas, accounting for 83.12%; and 13 people from the urban-rural junction, accounting for 5.49%. There were 51 only children, accounting for 21.52%; 186 non-only children, accounting for 78.48%; 36 people from provincial capitals, accounting for 15.19%; 161 people in prefecture-level cities, accounting for 67.93%; 38 people in county-level cities, accounting for 16.03%; and 2 people in rural towns and cities, accounting for 0.84%.

Reliability Analysis of the Questionnaire

In this study, the researchers designed 22 items (Q5 to Q26) to indirectly measure sociocultural adaptation and 20 items (Q27 to Q46) to measure psychological adaptation. These 2 types of items used different points scales; therefore, reliability and validity of sociocultural adaptation and psychological adaptation needed to be tested separately.

The Cronbach Alpha value of sociocultural adaptation was 0.951 >0.7, which shows that the reliability quality of the research data was very high (Table 2A). In view of “coefficient Alpha if Item deleted”, if items of Q5 and Q6 were deleted, the reliability coefficient will increase significantly (Table 2B). To sum up, the questionnaire data on sociocultural adaptation could be used for further analysis.

The Cronbach Alpha value of psychological adaptation was 0.789 >0.7, which shows that the reliability quality of the research data was very high and questionnaire data of sociocultural adaptation could be used for further analysis (Table 2A). Items of Q30, Q32, Q33, Q34, Q35, Q36, Q39, Q41, and Q42 needed be deleted to increase the reliability coefficient in view of “Corrected Item-Total Correlation” (Table 2C).

Validity Analysis of the Questionnaire

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) results of sociocultural adaptation dimension:

KMO and Bartlett’s test were used to verify the validity. Bartlett’s sphericity test revealed χ2=4614.674, df=231, P=0.000, and the KMO value was 0.919 >0.6, indicating that the validity of the research data was very good (Table 3.1.1).

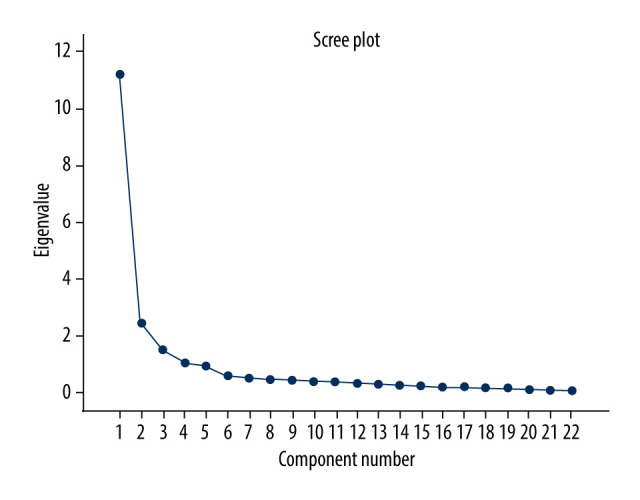

Using the scree test, the EFA identified the 3 dimensions of this questionnaires as demonstrated in the scree plot in Figure 1, explaining 68.831% of the variance.

Figure 1.

Scree test from the sociocultural acculturation questionnaire: the EFA identified the 3 dimensions of this questionnaires as demonstrated in the scree plot explaining 68.831% of the variance.

An overview of the results of the EFA is shown in Table 3.1.2. A total of 3 factors were extracted by factor analysis, and the eigenvalues were all greater than 1. The cumulative variance explanation rate after rotation was 68.831% >50%. Factor 1 accounted for 27.735% of the response variance (eigenvalue 6.102), Factor 2 accounted for 25.910% (eigenvalue 5.700), and Factor 3 accounted for 15.186% (eigenvalue 3.341).

As shown in Table 3.1.3, the corresponding communalities values of sociocultural adaptation items were all higher than 0.4, indicating that the research item information can be extracted effectively and there was a corresponding relationship between items and factors. Factor 1 (10 items), consisted of items Q8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, and 17. Factor 2 (9 items), consisted of items Q18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, and 26. Factor 3 (3 items), consisted of items Q5, 6, and 7.

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) results of psychological adaptation dimension:

In the first exploratory factor analysis results of all psychological adaptation items, KMO value was 0.854 >0.6, and Bartlett’s sphericity test revealed χ2=1947.425, df=190, P=0.000, indicating that the validity of the research data was very good (Table 3.2.1), but the corresponding communalities values of Q28, 32 were less than 0.4, indicating that the research item information could not be effectively expressed (Table 3.2.2). Therefore, these 2 items should be deleted and analyzed again after deletion.

After removing the suggested items, the corresponding communalities values were all higher than 0.4, indicating that the research item information could be extracted effectively and there was a corresponding relationship between items and factors (Table 3.2.3).

Using the scree test, the EFA identified the 4 dimensions of this questionnaires as demonstrated in the scree plot in Figure 2, explaining 61.999% of the variance.

Figure 2.

Scree test from the psychological acculturation questionnaire: the EFA identified the 4 dimensions of this questionnaires as demonstrated in the scree plot explaining 61.999% of the variance.

The KMO value was 0.850 >0.6, and Bartlett’s sphericity test revealed χ2=1840.170, df=153, P=0.000, indicating that the validity of the research data was very good (Table 3.2.4).

An overview of the results of the EFA is shown in Table 3.2.5. A total of 4 factors were extracted by factor analysis, and the eigenvalues were all greater than 1. Factor 1 accounted for 19.000% of the response variance (eigenvalue 3.420), Factor 2 accounted for 18.606% (eigenvalue 3.349), Factor 3 accounted for 12.731% (eigenvalue 2.292), and Factor 4 accounted for 11.661% (eigenvalue 2.099). The cumulative variance explanation rate after rotation was 61.999% >50%. Factor 1 (5 items), consisted of items Q40, 42, 43, 44, and 46. Factor 2 (6 items), consisted of items Q27, 29, 30, 36, 39, and 41. Factor 3 (4 items), consisted of items Q33, 34, 35, and 45. Factor 4 (3 items), consisted of items Q31, 37, and 38.

Overall Level of Transcultural Adaptation

In terms of sociocultural adaptation, the optimal score of the questionnaire was 110, and the higher the score, the better the sociocultural adaptation. The average score of sociocultural adaptability of Tibetan trainee nurses in this study was 85.14±16.60 (Table 4).

In terms of psychological adaptation, the maximum possible score of the questionnaire was 80. The lower the score was, the better the psychological adaptation would be. If the score exceeded 41, there were psychological problems [30]. The average score of Tibetan trainee nurses in this study was 38.70±10.19 (Table 4).

The original scores of all the respondents were converted to Z-scores, which were used as the study variable, with 0 as the average and 1 as the standard deviation.

The sociocultural adaptability of Tibetan trainee nurses was divided into 4 levels from poor to good, which were very poor, poor, good, and very good, corresponding to Z <−1, −1 ≤Z ≤0, and 0 <Z ≤1, Z >1. The number of participants and percentage at each level are shown in the Table 5.

On the contrary, the psychological adaptability of Tibetan trainee nurses was divided into 4 levels from good to poor, which were very good, good, poor, and very bad, respectively corresponding to Z <−1, −1 ≤Z ≤0, 0 <Z ≤1, and Z >1. The number of participants and percentage at each level are shown in the Table 6.

According to the data in Tables 5 and 6, the acculturation level of trainee nurses mainly focuses on the score of −1 ≤Z ≤0 and 0 <Z ≤1, which was at a medium level.

For the convenience of statistical analysis, the 2 groups with “good adaptability” and “very good adaptability” were combined as good adaptability, and the 2 groups with “poor adaptability” and “very poor adaptability” were combined as poor adaptability. According to statistics, the number of trainee nurses with poor sociocultural acculturation was slightly higher than that with good acculturation, with a difference of 5 (1.2%). In terms of the psychological adaptation of trainee nurses, 109 were well adapted, accounting for 46.0%, and 128 were poorly adapted, accounting for 54.0%, a difference of 19 (8%).

In general, the number of Tibetan trainee nurses with poor adaptability was slightly higher than the number with good adaptability. The statistical results of this paper were also consistent with the previous research results of other scholars [4,31].

The overall Situation of Acculturation of Tibetan Trainee Nurses of Different Genders

From the Table 7, it can be seen that the sociocultural adaptation of Tibetan trainee nurses of different genders was P=0.112>0.05, which meant there was no statistically significant differences in sociocultural adaptation between male and female Tibetan trainee nurses. In terms of psychological adaptation, P=0.846>0.05, which means there was no statistically significant differences in psychological adaptation between male and female Tibetan trainee nurses.

The Overall Situation of Transcultural Adaptation of Tibetan Trainee Nurses from Different Student Home Regions

The variance of the data in each group was uniform after the homogeneity of variance test. The data are expressed as mean±standard deviation. According to a one-way analysis of variance, there was no statistically significant difference in the overall level of cultural adaptation of Tibetan trainee nurses from different home regions. The CWWS score of sociocultural adaptation was: F (2234)=1.599, P=0.204, and the CWWS score of psychological adaptation was: F (2234)=2.103, P=0.124 (Table 8).

The Overall Situation of Transcultural Adaptation of Tibetan Trainee Nurses from Single-Child or Multi-child Families

The independent sample t test was used to judge the difference in the overall situation of transcultural adaptation of Tibetan trainee nurses from single-child or multi-child families. The research data had uniform variance. The results showed that the sociocultural adaptation of Tibetan trainee nurses from single-child or multi-child families was P=0.097 >0.05, and psychological adaptation of Tibetan trainee nurses from single-child or multi-child families was P=0.207 >0.05. Therefore, there was no statistically significant differences in psychological adaptation and sociocultural adaptation from single-child or multi-child families (Table 9).

The Overall Situation of Transcultural Adaptation of City Administration Level Where the Internship Hospital Was Located

The variance of each group of data proved by the test of homogeneity of variance was uniform. The data are expressed as mean±standard deviation.

According to the univariate analysis of variance, there was no statistically significant differences in the influence of the city administration level where the internship hospital was located. The CWWS scores of sociocultural adaptation were: F (3, 233)=233)=0.337, P=0.799, and the CWWS scores of psychological adaptation were: F (3, 233)=233)=1.207, P=0.308 (Table 10).

Discussion

There were 237 samples in this study. Through data analysis, in the overall level of transcultural adaptation of Tibetan trainee nurses, the number of people with poor adaptation was higher than those with good adaptation. The number of people with poor sociocultural adaptation was 1.2% higher than those with good adaptation, and the number of people with poor psychological adaptation was 8% higher than those with good adaptation. This showed that the overall level of transcultural adaptation of most Tibetan trainee nurses was in the middle level, and sociocultural adaptability was better than psychological adaptability. We found no statistically significant differences among the 4 grouping variables: gender, student home region, the city where the internship hospital was located, and whether it was a single-child family or not. Such statistical results made the analysis of the reasons that affect the transcultural adaptation level of Tibetan trainee nurses complicated. This may be explained from the perspective of culture shock theory. In the theory of culture shock, individuals who leave their familiar cultural environment and enter an unfamiliar cultural environment are likely to experience temporary doubts, anxiety, and depression [30].

The previously published papers by Zhong suggested that physical and mental health were related to life changes, and life changes in transcultural adaptation had a direct impact on psychological adaptation [32].

Culture shock includes 3 aspects: the subject of culture shock was human, mental state anxiety (psychological and emotional changes) leads to some changes in behavior, and the subject’s environment is changed [33]. As long as there is cultural exchange, culture shock is inevitable. The emergence of culture shock is not only the collision of multiple cultures, but also the influence of individual psychology, which is complex. Because of great changes in the living environment, individuals are far away from the familiar rules of behavior, coupled with language communication barriers, confusion, helplessness, panic, and escape psychology, which intensify psychological discomfort. This requires individuals to gradually adapt to the new environment and new changes, moving from “cultural shock” to “cultural adaptation”.

In the Chinese multi-ethnic cultural environment, Han culture occupies a dominant position compared with the minority cultures [34]. Although the inclusive nature of Han culture means the integration of different ethnic cultures, the differences between Han culture and minority culture still exist due to the more simple and unique nature of minority cultures [35].

Tibetan culture is very different from Han culture in language, diet, clothing, geographical environment, regional economy, and religious belief, and it provides a rich cultural inheritance [36]. Although the economy in Tibet is relatively underdeveloped and mainly relies on agriculture, animal husbandry, and tourism to drive economic development [37], the people in this region have a strong and unique ethnic cultural atmosphere [38].

On the other hand, the economy of inland Chinese cities is based on industry and commerce, with relatively independent personality characteristics, fast-paced life, and Chinese-based language environment [39]. When ethnic minority individuals enter the Chinese cultural environment and leave behind their familiar cultural environment, the impact of cultural differences can cause problems in transcultural adaptation [40].

Individuals of different national cultures would inevitably be influenced by the way of thinking and cognitive habits formed in the cultural environment in which they lived for a long time [41]. The culture is pluralistic, and there must be cultural differences in a pluralistic culture [41]. To a certain extent, cultural differences can deepen the understanding and integration between different ethnicities and enrich national culture, but on the other hand, it can produce obstacles, contradictions, and even conflicts in their exchanges, affecting national unity and the stability and harmony of the whole society [42].

Countermeasures and suggestions on improving the transcultural adaptability

1. Carry out multicultural teaching and training to improve transcultural adaptability

Chinese school education should learn from the training model of cultivating teachers’ transcultural adaptability in the United States, actively carry out multicultural education, and focus on multicultural teaching [43]. Attention should be paid to improving their ability to understand, choose, and adapt to cultural diversity, rather than just imparting to them the established basic educational courses, educational method courses, and educational practice courses [44]. While paying attention to the implementation of these courses, we should integrate some multicultural curriculum and instructional design contents into them to improve their multicultural quality and enhance their ability to adapt to culture [45].

Pre-university education should give full play to their advantages of talents, make full use of the advantages of cultural resources in this region, and develop multicultural courses [46]. The development of multicultural courses is based on a comprehensive and objective understanding of the political traditions, economic development, cultural customs, educational background, and religious beliefs of various ethnic groups, and the study of multicultural courses cannot be evaluated and studied by a single discipline [47]. Minority students should comprehensively use the comprehensive perspectives of pedagogy, psychology, anthropology, ethnology, sociology, statistics, and other disciplines to study, all of which require them to proceed from the reality and actual situation of their own ethnic areas [47]. To explore a multicultural curriculum model that is suitable for the advantages and characteristics of the nation and the region [43]. When developing and designing the curriculum, teachers should fully consider the students from different regions, different nationalities, and different cultural backgrounds, provide them with a variety of curriculum cultural resources, and cultivate students’ transcultural awareness, ability, and way of thinking [48].

2. Pay attention to the training of knowledge, attitude, and ability of transcultural adaptation

On the topic of national culture, it mainly includes the following contents: first, the knowledge about the basic connotation of ethnic education and multicultural education; second, the knowledge about various aspects of ethnic minorities, that is, the knowledge of the history of political development, economic status, religious beliefs and cultural traditions of ethnic minorities; and the third is about national habits and behaviors that are prone to misunderstandings and cultural discrimination and prejudice [49].

In the teaching of national culture, the simple understanding of multicultural curriculum should not only impart the theoretical knowledge of national culture and multicultural theory, but should guide students on the basis of understanding the theoretical knowledge of multiculturalism. Inspire them to think deeply about multiculturalism, and pay attention to students’ emotional experience while learning the theoretical knowledge of national culture. Constantly enhance the internal relationship between cultural learning and the cultivation of national culture, identity, and pride [50].

1. Strengthen self-adjustment and cultural participation.

1) Respect local culture and customs, and enhance the awareness of cultural diversity.

China is a multi-ethnic country, which naturally presents diversity in the cultural field.

Different ethnic groups and regions have their own unique cultural traditions, but they also have their drawbacks. Interns should understand the historical development, clothing characteristics, dietary customs, and other aspects of the place where the hospital is located, so as to understand and respect the local culture.

2) Learn to self-adjust.

For the majority of interns, the process of cultural adaptation is a process of psychological growth and maturity, which can be difficult [51].

In this process, nurses not only have to face the tremendous changes in their living environment, the differences in dietary customs, religious culture, and bear the pressure and challenges from these aspects, they even have to experience doubts about their own identity and thinking.

If growth is divided into 2 parts, then “first growth” is the process of continuous growth under the influence of local culture, then “second growth” occurs during the process of gradually adjusting, adapting, accepting, and integrating into a new culture [52].

If a person can use a proactive attitude to recognize cultural differences, consciously respect cultural differences, and actively and objectively coordinate cultural differences, transcultural adaptability is basically formed [53]. Of course, it also means that they complete the process of “second growth”. However, there are always some problems caused by differences in their own experience that are difficult to solve and eliminate. At this time, only by constantly adjusting their psychological ability to constantly refine their cognitive system to adapt to different cultures with an open mind can they gradually alleviate the various discomforts caused by “conflict” [54].

3) Strengthen cultural integration and cultural participation.

Tibetan trainee nurses should abandon incorrect cultural stereotypes, cultural relativism, and ethnocentrism, and focus on strengthening the integration of their own national culture and local culture [53]. To be specific, while the interns identify with their own national culture, they actively understand and identify with the people’s ideas, values, beliefs, ways of thinking and behavior, folk customs, living habits, and other cultural elements in the place where the hospital is located [48]. If Tibetan students want to better adapt to the local culture, they should try not to judge everything in a local culture by their own cultural standards, nor to deal with all kinds of things in life with their own way of thinking and behavior [7].

Conclusions

In this study, we investigated the transcultural adaptation of Tibetan trainee nurses from the 2 dimensions of sociocultural adaptation and psychological adaptation. The result revealed that there was still transcultural maladjustment among Tibetan nurses in the internship stage, and the psychological maladjustment was more obvious in the sociocultural maladjustment.

Aiming at the problem of cross-cultural adaptation reflected in the study, we put forward some suggestions and strategies. It was hoped that this article can provide more theoretical support and guidance for the cultivation of cross-cultural adaptability of young Tibetans and other ethnic minorities in China.

However, there was still a shortcoming in this study. This paper mainly discussed the transcultural adaptation of Tibetan nurses in the internship stage, but in fact, this group had received theoretical teaching in mainland schools for 2 years before entering the internship stage. In other words, during the period from the original Tibetan cultural circle to the internship stage and full contact with Chinese culture, they had a 2-year buffer adaptation period. As sampled individuals, their own adaptability was different, which will also have had a certain impact on the survey results. In the subsequent similar research design, nursing students of Tibetan origin can be followed up to investigate their intercultural adaptation in the first year, the second year, and the internship stage to establish a dynamic and comparative survey database.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary Table 1.

The questionnaire of transcultural adaptation of Tibetan nursing trainees.

| Serial number | Questions | Answers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Gender | Male | Female | |||

| Q2 | Student source region | Urban | Rural or grazing district | Urban rural fringe area | ||

| Q3 | One-child family | Yes | No | |||

| Q4 | City administration level where the internship hospital was located | Provincial capital city | Prefecture level city | County level city | Rural area | |

| Q5 | Very adaptable to the area where you practice | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q6 | In daily communication, you are not confused about the cultural environment of your internship area | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q7 | Very adaptable to the hospital environment of practice | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q8 | Often interact with students of different ethnic groups who are interning together | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q9 | Have no difficulty in communicating with students of different nationalities | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q10 | Consider the appropriate ways and methods to communicate with students of different nationalities | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q11 | Harmonious relationship with teachers of different nationalities in practice hospitals | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q12 | Often communicate with teachers of different nationalities | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q13 | When encountering difficulties in life and practice, we can get help from teachers of other nationalities | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q14 | There is no difficulty in communicating with the family members of patients of different nationalities | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q15 | Often discuss the condition with patients of different nationalities or their families | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q16 | Be able to understand the patient or the patient’s expression of their condition | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q17 | Teachers of different nationalities can consider students’ cultural background in teaching design | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q18 | Teachers usually try their best to hang educational content close to the life of students in ethnic areas | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q19 | Teachers can pay attention to the differences of national cultural background when arranging internship tasks | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q20 | To be able to use local traditional customs to guide students in cultural integration cognition | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q21 | The students of different nationalities can be reasonably evaluated in terms of internship tasks | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q22 | Can often reflect on their own internship results | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q23 | In the process of practice, our national culture can receive respect | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q24 | In the process of practice, I can also respect the cultural customs of different nationalities | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q25 | Teachers can provide opportunities to learn about the democratic culture and other national cultures | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q26 | Practice hospitals can pay attention to the learning needs of students of different nationalities | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q27 | I feel down-hearted and blue | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q28 | Morning is When I feel the best | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q29 | I have crying spells or feel like it | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q30 | I have trouble sleeping at night | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q31 | I eat as much as I used to | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q32 | I am as happy as ever in close contact with the opposite sex | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q33 | I’ve noticed that I’m losing weight | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q34 | I have trouble with constipation | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q35 | My heart beats faster than usual | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q36 | I feel tired for no reason | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q37 | My mind is as clear as it used to be | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q38 | I find it easy to do the thing I used to | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q39 | I am restless and cannot keep still | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q40 | I feel hopeful about the future | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q41 | I am more irritable than usual | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q42 | I find it easy to make a decision | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q43 | I feel that I’m useful and needed | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q44 | My life is pretty full | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q45 | I feel that others would be better off if I were dead | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q46 | I still enjoy the things I used to do | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

Table 2.

Reliability Statistics.

| (A) Cronbach Alpha. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cronbach’s Alpha | Cronbach’s Alpha Based on Standardized items | N of Items | n | |

| Sociocultural adaptation | 0.951 | 0.952 | 22 (Q5 to Q26) | 237 |

| Psychological adaptation | 0.789 | 0.787 | 20 (Q27 to Q46) | 237 |

| (B) Reliability statistics of sociocultural adaptation. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Items | Corrected item-total correlation (CITC) | Cronbach Alpha if item deleted | Cronbach α |

| Q5 | 0.450 | 0.951 | 0.951 |

| Q6 | 0.337 | 0.952 | |

| Q7 | 0.534 | 0.950 | |

| Q8 | 0.634 | 0.949 | |

| Q9 | 0.738 | 0.947 | |

| Q10 | 0.745 | 0.947 | |

| Q11 | 0.670 | 0.948 | |

| Q12 | 0.651 | 0.949 | |

| Q13 | 0.717 | 0.948 | |

| Q14 | 0.686 | 0.948 | |

| Q15 | 0.608 | 0.950 | |

| Q16 | 0.660 | 0.949 | |

| Q17 | 0.748 | 0.947 | |

| Q18 | 0.724 | 0.948 | |

| Q19 | 0.764 | 0.947 | |

| Q20 | 0.799 | 0.947 | |

| Q21 | 0.825 | 0.947 | |

| Q22 | 0.744 | 0.948 | |

| Q23 | 0.666 | 0.949 | |

| Q24 | 0.639 | 0.949 | |

| Q25 | 0.717 | 0.948 | |

| Q26 | 0.698 | 0.948 | |

Cronbach α (Standardized): 0.952.

| (C) ) Reliability statistics of psychological adaptation. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Items | Corrected item-total correlation (CITC) | Cronbach Alpha if item deleted | Cronbach α |

| Q27 | 0.328 | 0.782 | 0.789 |

| Q28 | 0.335 | 0.781 | |

| Q29 | 0.424 | 0.778 | |

| Q30 | 0.216 | 0.788 | |

| Q31 | 0.439 | 0.774 | |

| Q32 | 0.267 | 0.786 | |

| Q33 | 0.109 | 0.792 | |

| Q34 | 0.136 | 0.792 | |

| Q35 | 0.261 | 0.785 | |

| Q36 | 0.214 | 0.788 | |

| Q37 | 0.464 | 0.772 | |

| Q38 | 0.376 | 0.778 | |

| Q39 | 0.265 | 0.785 | |

| Q40 | 0.523 | 0.767 | |

| Q41 | 0.257 | 0.785 | |

| Q42 | 0.270 | 0.785 | |

| Q43 | 0.578 | 0.764 | |

| Q44 | 0.555 | 0.766 | |

| Q45 | 0.313 | 0.782 | |

| Q46 | 0.585 | 0.762 | |

Cronbach α (Standardized): 0.787.

Table 3.

Validity analysis.

1 Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) results of sociocultural adaptation dimension.

3.1.1.

KMO and Bartlett test of all items.

| KMO | 0.919 | |

| Bartlett test | Approx. Chi-Square | 4614.674 |

| df | 231 | |

| p value | 0.000 | |

3.1.2.

Total variance explained of all items.

| Factor | Eigen values | % of variance (initial) | % of variance (rotated) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eigen | % of Variance | Cum. % of Variance | Eigen | % of Variance | Cum. % of Variance | Eigen | % of Variance | Cum. % of Variance | |

| 1 | 11.184 | 50.837 | 50.837 | 11.184 | 50.837 | 50.837 | 6.102 | 27.735 | 27.735 |

| 2 | 2.444 | 11.109 | 61.946 | 2.444 | 11.109 | 61.946 | 5.700 | 25.910 | 53.645 |

| 3 | 1.515 | 6.885 | 68.831 | 1.515 | 6.885 | 68.831 | 3.341 | 15.186 | 68.831 |

| 4 | 1.058 | 4.810 | 73.640 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 5 | 0.927 | 4.214 | 77.854 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 6 | 0.583 | 2.650 | 80.504 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 7 | 0.506 | 2.301 | 82.805 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 8 | 0.463 | 2.105 | 84.910 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 9 | 0.447 | 2.031 | 86.941 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 10 | 0.401 | 1.822 | 88.763 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 11 | 0.368 | 1.672 | 90.435 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 12 | 0.314 | 1.427 | 91.861 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 13 | 0.298 | 1.355 | 93.217 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 14 | 0.243 | 1.103 | 94.320 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 15 | 0.241 | 1.096 | 95.416 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 16 | 0.207 | 0.942 | 96.358 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 17 | 0.204 | 0.928 | 97.285 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 18 | 0.172 | 0.780 | 98.066 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 19 | 0.150 | 0.681 | 98.747 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 20 | 0.114 | 0.519 | 99.265 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 21 | 0.091 | 0.413 | 99.678 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 22 | 0.071 | 0.322 | 100.000 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

3.1.3.

Factor loading (rotated).

| Items | Factor loading | Communalities | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | ||

| Q5 | 0.088 | 0.201 | 0.799 | 0.686 |

| Q6 | 0.041 | 0.093 | 0.776 | 0.612 |

| Q7 | 0.183 | 0.228 | 0.800 | 0.725 |

| Q8 | 0.677 | 0.096 | 0.394 | 0.623 |

| Q9 | 0.678 | 0.294 | 0.325 | 0.652 |

| Q10 | 0.536 | 0.409 | 0.409 | 0.623 |

| Q11 | 0.577 | 0.311 | 0.316 | 0.530 |

| Q12 | 0.844 | 0.120 | 0.085 | 0.734 |

| Q13 | 0.767 | 0.312 | 0.072 | 0.691 |

| Q14 | 0.788 | 0.260 | 0.037 | 0.690 |

| Q15 | 0.787 | 0.159 | 0.010 | 0.645 |

| Q16 | 0.450 | 0.395 | 0.378 | 0.501 |

| Q17 | 0.717 | 0.432 | 0.041 | 0.702 |

| Q18 | 0.502 | 0.648 | 0.019 | 0.672 |

| Q19 | 0.536 | 0.666 | 0.024 | 0.732 |

| Q20 | 0.502 | 0.725 | 0.081 | 0.785 |

| Q21 | 0.508 | 0.727 | 0.131 | 0.804 |

| Q22 | 0.285 | 0.664 | 0.452 | 0.725 |

| Q23 | 0.092 | 0.757 | 0.451 | 0.784 |

| Q24 | 0.120 | 0.664 | 0.490 | 0.695 |

| Q25 | 0.285 | 0.790 | 0.171 | 0.735 |

| Q26 | 0.162 | 0.834 | 0.273 | 0.796 |

Bold indicates that the absolute value of loading is greater than 0.4, and red indicates that the communality is less than 0.4.

2.

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) results of psychological adaptation dimension.

3.2.1 KMO and Bartlett test of all items.

| KMO | 0.854 | |

| Bartlett test | Approx. Chi-Square | 1947.425 |

| df | 190 | |

| p value | 0.000 | |

3.2.2.

Factor loading (rotated) of all items.

| Items | Factor loading | Communalities | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | ||

| Q27 | −0.032 | 0.784 | 0.135 | 0.094 | 0.643 |

| Q29 | 0.092 | 0.856 | 0.063 | 0.068 | 0.750 |

| Q30 | −0.096 | 0.726 | 0.084 | −0.004 | 0.543 |

| Q31 | 0.353 | 0.084 | −0.017 | 0.669 | 0.579 |

| Q34 | −0.042 | 0.087 | 0.798 | −0.091 | 0.654 |

| Q35 | −0.010 | 0.357 | 0.720 | −0.111 | 0.659 |

| Q36 | 0.130 | 0.506 | 0.355 | −0.424 | 0.578 |

| Q37 | 0.379 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.754 | 0.712 |

| Q38 | 0.379 | −0.093 | −0.112 | 0.750 | 0.727 |

| Q39 | 0.008 | 0.658 | 0.319 | −0.152 | 0.558 |

| Q28 | 0.485 | 0.084 | 0.025 | 0.016 | 0.243 |

| Q32 | 0.436 | −0.162 | −0.016 | 0.275 | 0.292 |

| Q33 | −0.123 | 0.097 | 0.625 | 0.053 | 0.418 |

| Q40 | 0.730 | −0.016 | −0.024 | 0.282 | 0.613 |

| Q41 | 0.045 | 0.556 | 0.408 | −0.222 | 0.527 |

| Q42 | 0.553 | −0.172 | −0.179 | 0.227 | 0.419 |

| Q43 | 0.829 | 0.028 | −0.042 | 0.177 | 0.721 |

| Q44 | 0.834 | 0.078 | −0.048 | 0.065 | 0.708 |

| Q45 | 0.016 | 0.476 | 0.561 | 0.027 | 0.542 |

| Q46 | 0.785 | 0.044 | 0.001 | 0.235 | 0.674 |

Bold indicates that the absolute value of loading is greater than 0.4, and italics indicates that the communality is less than 0.4.

3.2.3.

Factor loading (rotated).

| Items | Factor loading | Communalities | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | ||

| Q27 | −0.044 | 0.773 | 0.143 | 0.116 | 0.633 |

| Q29 | 0.091 | 0.851 | 0.063 | 0.075 | 0.743 |

| Q30 | −0.129 | 0.730 | 0.075 | 0.028 | 0.556 |

| Q31 | 0.324 | 0.089 | −0.024 | 0.682 | 0.578 |

| Q34 | −0.049 | 0.088 | 0.805 | −0.088 | 0.666 |

| Q35 | −0.019 | 0.373 | 0.706 | −0.118 | 0.651 |

| Q36 | 0.112 | 0.531 | 0.331 | −0.423 | 0.583 |

| Q37 | 0.387 | −0.010 | 0.017 | 0.749 | 0.712 |

| Q38 | 0.391 | −0.107 | −0.099 | 0.747 | 0.732 |

| Q39 | 0.026 | 0.670 | 0.301 | −0.173 | 0.569 |

| Q33 | −0.126 | 0.096 | 0.629 | 0.049 | 0.424 |

| Q40 | 0.729 | −0.012 | −0.019 | 0.289 | 0.615 |

| Q41 | 0.034 | 0.572 | 0.390 | −0.217 | 0.527 |

| Q42 | 0.578 | −0.187 | −0.156 | 0.220 | 0.442 |

| Q43 | 0.849 | 0.026 | −0.027 | 0.177 | 0.754 |

| Q44 | 0.841 | 0.080 | −0.037 | 0.073 | 0.721 |

| Q45 | 0.023 | 0.466 | 0.575 | 0.027 | 0.549 |

| Q46 | 0.810 | 0.052 | 0.004 | 0.215 | 0.706 |

Bold indicates that the absolute value of loading is greater than 0.4.

3.2.4.

KMO and Bartlett tes.

| KMO | 0.850 | |

| Bartlett test | Approx. Chi-Square | 1840.170 |

| df | 153 | |

| p value | 0.000 | |

3.2.5.

Total variance explained.

| Factor | Eigen values | % of variance (initial) | % of variance (rotated) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eigen | % of variance | Cum. % of variance | Eigen | % of variance | Cum. % of variance | Eigen | % of variance | Cum. % of variance | |

| 1 | 4.860 | 27.002 | 27.002 | 4.860 | 27.002 | 27.002 | 3.420 | 19.000 | 19.000 |

| 2 | 4.015 | 22.306 | 49.308 | 4.015 | 22.306 | 49.308 | 3.349 | 18.606 | 37.607 |

| 3 | 1.195 | 6.641 | 55.949 | 1.195 | 6.641 | 55.949 | 2.292 | 12.731 | 50.338 |

| 4 | 1.089 | 6.050 | 61.999 | 1.089 | 6.050 | 61.999 | 2.099 | 11.661 | 61.999 |

| 5 | 0.937 | 5.204 | 67.203 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 6 | 0.830 | 4.610 | 71.813 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 7 | 0.704 | 3.911 | 75.724 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 8 | 0.668 | 3.713 | 79.437 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 9 | 0.498 | 2.765 | 82.202 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 10 | 0.487 | 2.707 | 84.909 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 11 | 0.448 | 2.489 | 87.397 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 12 | 0.428 | 2.376 | 89.773 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 13 | 0.380 | 2.113 | 91.887 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 14 | 0.353 | 1.962 | 93.849 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 15 | 0.322 | 1.787 | 95.636 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 16 | 0.304 | 1.688 | 97.324 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 17 | 0.265 | 1.469 | 98.793 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 18 | 0.217 | 1.207 | 100.000 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

Table 4.

Acculturation average score.

| N | Sociocultural adaptability | Psychological adaptability | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average scores | 237 | 85.14±16.60 | 38.70±10.19 |

Table 5.

Statistical table of overall level of sociocultural acculturation.

| Z <−1 | −1 ≤Z ≤0 | 0 <Z ≤1 | Z >1 | Good adaptability | Poor adaptability | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 41 | 80 | 69 | 47 | 116 | 121 | 237 |

| % | 17.3 | 33.8 | 29.1 | 19.8 | 48.9 | 51.1 | 100 |

Table 6.

Statistical table of the overall level of psychological adaptation.

| Z <−1 | −1 ≤Z ≤0 | 0 <Z ≤1 | Z >1 | Good adaptability | Poor adaptability | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 41 | 68 | 96 | 32 | 109 | 128 | 237 |

| % | 17.3 | 28.7 | 40.5 | 13.5 | 46.0 | 54.0 | 100 |

Table 7.

The overall situation of acculturation of trainee nurses of different genders.

| Female (N=222) | Male (N=15) | Levene’s test for equality of variances | t-test for equality of variances | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | P value | t | P value | |||

| Sociocultural adaptability | 85.58±16.36 | 78.53±19.17 | 0.627 | 0.429 | 1.597 | 0.112 |

| Psychological adaptability | 38.73±10.17 | 38.20±10.86 | 0.000 | 0.992 | 1.195 | 0.846 |

Table 8.

The overall situation of transcultural adaptation of Tibetan trainee nurses from different student source region.

| Student source region | Test of homogenity of variances | ANOVA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban (N=197) | Rural or grazing district (N=27) | Urban rural fringe area (N=13) | Levene statistic value | P Value | F Value | P Value | |

| Sociocultural adaptability | 84.52±1.22 | 85.85±2.64 | 92.92±3.16 | 2.159 | 0.118 | 1.599 | 0.204 |

| Psychological adaptability | 39.13±0.75 | 34.96±1.53 | 39.92±2.44 | 0.818 | 0.443 | 2.103 | 0.124 |

Table 9.

The overall situation of transcultural adaptation of Tibetan trainee nurses from single-child or multi-child families.

| One-Child family | Levene’s Test for equality of variances | t-test for equality of variances | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (N=51) | No (N=186) | F | P value | t | P value | |

| Sociocultural adaptability | 88.55±2.34 | 84.20±1.21 | 0.829 | 0.364 | 1.665 | 0.097 |

| Psychological adaptability | 37.10±1.60 | 39.13±0.72 | 2.066 | 0.152 | −1.266 | 0.207 |

Table 10.

The overall situation of transcultural adaptation of city administration level of internship.

| City administration level where the internship hospital was located | Test of homogenity of variances | ANOVA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| provincial capital city (N=36) | Prefecture level city (N=161) | County level City (N=38) | Rural area (N=2) | Levene statistic value | P value | F | P value | |

| Sociocultural adaptability | 87.11±2.56 | 84.41±1.35 | 86.34±2.60 | 85.00±3.00 | 2.146 | 0.095 | 0.337 | 0.799 |

| Psychological adaptability | 36.17±1.79 | 39.21±0.77 | 39.26±1.86 | 32.00±3.00 | 1.325 | 0.267 | 1.207 | 0.308 |

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None.

Source of support: Support for this study was received from the Primary Health Development Research Center of Sichuan Province (Grant Number: SWFZ20-Y-030) and Bureau of Science & Technology Nanchong City (Grant Number: 19SXHZ0352)

References

- 1.Ciren W, Yu W, Nima Q, et al. Social capital and sleep disorders in Tibet, China. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:591. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10626-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Che M. Tibet geo-political and strategic position in South Asia and India Ocean as well as its overall situation of the Chinese nation. Tibet Stud. 2016:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sai D, Lengzhi W, Luo Z. [Poverty situation and developing dilemma of Tibetan areas in Gansu, Qinghai, Sichuan and Tibet – based on family investigation in Daka Village of Banma County, Qinghai]. Natl Res Qinghai. 2017;028:155–59. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ji H. [Study on cultural adaptation and countermeasures of “9+3” students in Tibetan areas of Sichuan province]. J Southwest Univ Natl. 2017:75–80. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hongpei X, Chunhua X. [Thoughts on strengthening the principles, methods and approaches of inspirational education for “9+3” students in Tibetan areas]. J Chengdu Univ Tradit Chinese Med Sci Ed. 2019:20–22. 43. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tao Z, Yang Z, Pu J. [Re-examined of the“9+3” free secondary vocational education Program in Sichuan minority areas after its implementation for ten years]. J Sichuan Norm Univ Sci Ed. 2020:106–12. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yin F, Shen H, He Y, Wei Y, Cao W. Typical dreams of “being chased”: A cross-cultural comparison between Tibetan and Han Chinese dreamers. Dreaming. 2013;23:64–77. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson TL, Kiang L, Witkow MR. J Youth Adolesc [Internet] Vol. 49. Springer; US: 2020. Discrimination, the model minority stereotype, and peer relationships across the high school years; pp. 1884–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Milburn NG, Batterham P, Ayala G, et al. Discrimination and mental health problems among homeless minority young people. Public Health Rep. 2010;125:61–67. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li X, Qin W, Yan Z. [Study on the “9+3” nursing teaching model in Tibetan areas]. Med Inf. 2019:176–77. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Romera EM, Gómez-Ortiz O, Ortega-Ruiz R. The mediating role of psychological adjustment between peer victimization and social adjustment in adolescence. Front Psychol. 2016;7 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swirsky JM, Xie H. J Youth Adolesc [Internet] Vol. 50. Springer; US: 2021. Peer-Related Factors as Moderators between Overt and Social Victimization and Adjustment Outcomes in Early Adolescence; pp. 286–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yufeng Y. [Research on the current situation, characteristics and promotion strategies of “9+3” students’ acculturation-taking a vocational school in Guangyuan, Sichuan province as an example]. West China. 2018:110–16. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Changjiang G. The nurse practicing qualification examination and nursing personnel training. Career Horiz. 2013:84–86. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith ME. From student to practicing nurse. Am J Nurs. 2007;107:72A–72D. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung HC, Hsieh TC, Chen YC, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Chinese Comfort, Afford, Respect, and Expect scale of caring nurse–patient interaction competence. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27:3287–97. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ward C, Kennedy A. Locus of control, mood disturbance, and social difficulty during cross-cultural transitions. Int J Intercult Relations. 1992;16:175–94. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma X, Yin X. [Investigation and countermeasures on cross-cultural adaptation of Africa overseas students in China]. J Hebei Univ Econ Business (Comprehensive Ed) 2019;19:10–15. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun J. [Cultural adaptation: Western theories and models]. J Beijing Norm Univ Sci. 2010:45–52. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qianqian L, Fei S, Tingfa Y, Zheng S. [Bibliometric analysis of the current status of cross-cultural nursing research in China]. J Taishan Med Coll. 2019;40:564–67. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Slethaug GE. Teaching abroad: International education and the cross-cultural classroom. Hong Kong University; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruiqi W, Qin C, Ming X. Bibliometric analysis of multicultural nursing development in China in recent ten years. Heal Vocat Educ. 2020;38:154–57. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Donghong H, Lin C. The application and research status of intercultural nursing theory in various nationalities. J Clin Nursing’s Pract. 2019;4:197–202. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ouarasse OA, Van De Vijver FJR. The role of demographic variables and acculturation attitudes in predicting sociocultural and psychological adaptation in Moroccans in the Netherlands. Int J Intercult Relations. 2005;29:251–72. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Q. [The research on the sociocultural adaptation of RetP students under the background of cross-cultural]. Qinghai Normal University; 2016. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiao-Ling XI, Liu YF. The application of We Chat platform plus questionnaire star in the fall cognitive training of psychiatric nurses,cleaning staff and patients. Nurs Pract Res. 2017;14:114–17. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferreira M, Verloo H, Mabire C, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the French version of the questionnaire attitudes towards morphine use; A cross-sectional study in Valais, Switzerland. BMC Nurs. 2014;13:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6955-13-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang M, Ge L, Rask M. Cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric testing of the Verbal and Social Interaction Questionnaire: A cross-sectional study among nursing students in China. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28:2181–96. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yong AG, Pearce S. A Beginner’s guide to factor analysis: Focusing on exploratory factor analysis. Tutor Quant Methods Psychol. 2013;9:79–94. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zheng J, Jiang XM, Huang XX. [Investigation on depressive mood of nurses in a maternal and child hospital]. Zhonghua Lao Dong Wei Sheng Zhi Ye Bing Za Zhi. 2018;36:618–21. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-9391.2018.08.014. [in Chinese] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yanbin H, Yixuan Xi, Jun Z, Birong Y. [Cross-cultural nuring ability of 384 nuring students and its influence factors]. J Nuring (China) 2019;26:45–49. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhong R, Wang D, Cao Y, Liu X. A Study on interpersonal relationship and psychological adaptation among the influencing factors of international students’ cross-cultural adaptation. Psychology. 2020;11:1757–68. [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Brien K. Beware of culture shock. Am Print. 2010;127:8. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma Y. [Enhancement of the communal consciousness of the Chinese nation for developing ethnic minority cultures in the process of strengthening our national unity]. J Yunnan Natl Univ Sci. 2018:5–11. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hui L. [Regional basis of the formation of chilechuan culture and factors of multi-ethnic integration]. J North Minzu Univ Soc Sci. 2019:37–42. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 36.China Office TSCI. Protection and development of Tibetan culture. Hum Rights. 2008:10–19. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peng D, Chen X. [Empirical study on the coupling relationship between Tibetan industrial competitiveness and regional economic development]. Mod Tradit Chinese Med Mater Medica. 2018:1895–99. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wen-Ke MI, Sheng-Li Y, Philosophy DO. Tibetan culture symols from the perspective of religion culture. Tibet Stud. 2014:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Junsheng LI. [The fiscal base and the pillar for supporting China’s economic reform and opening to the world during the past 40 years: Theoretical review of fiscal function and role]. J Liaoning Univ Soc Sci Ed. 2018:31–44. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu H, Xiang C. [Thoughts on strengthening the principles, methods and approaches of inspirational education for “9+3” students in Tibetan areas]. J Chengdu Univ Tradit Chinese Med Sci Ed. 2019:20–12. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Szydo J, Grze-Bukaho J. Relations between national and organisational culture – case study. Sustainability. 2020;12:1522. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Archbold M, Chami D. Finding common ground: Human rights and cultural difference, a student perspective. Glob Networked Teach Humanit Theor Pract. 2015:169–79. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ishmuradova II, Ishmuradova AM. Multicultural education of students as an important part of education. Int J High Educ. 2019;8:111. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tarhini A, Hone K, Liu X. A cross-cultural examination of the impact of social organisational and individual factors on educational technology acceptance between British and Lebanese university students. Br J Educ Technol. 2016;46:739–55. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Erten EY, Pieter VDB, Weissing FJ. Acculturation orientations affect the evolution of a multicultural society. Nat Commun. 2018;9:58. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02513-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shu Y, Liming Z. J Yunnan Norm Univ Res Chinese as A Foreign Lang. 2007. The training of pre-university students from Southeast Asian countries from the cross-cultural perspective; pp. 75–78. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Samydevan V, Piaralal SK, Othman AK, et al. Impact of psychological traits, entrepreneurial education and culture in determining entrepreneurial intention among pre-university students in Malaysia. Am J Econ. 2015;5:163–67. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Horky S, Andreola J, Black E, Lossius M. Evaluation of a cross cultural curriculum: Changing knowledge, attitudes and skills in pediatric residents. Matern Child Heal J. 2017;21:1537–43. doi: 10.1007/s10995-017-2282-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Uichol K. Psychology, science, and culture: Cross-cultural analysis of national psychologies. Int J Psychol. 1995;30:663–79. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou Z. [On the curriculum objectives and contents of cultural appropriateness in the multicultural context]. Theory Pract Educ. 2014:61–64. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xia Q. Research on the adaptation problems of Tibetan students in Main China under the cross-cultural environment. J Tibet Univ. 2013:78–82. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nahhas E. Multiculturalism and inter-faith understanding at teaching colleges in Israel: Minority vs. majority perspectives. Relig Educ. 2020:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Howard-Hamilton MF, Hinton KG. Using entertainment media to inform student affairs teaching and practice about multiculturalism. New Dir Student Serv. 2004;2004:25–35. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shurui LI. [The effect on the embedded mode of the Qinghai – Tibet plateau of the cultural identity of ethnic minorities]. J Qinghai Norm Univ Soc Sci Ed. 2017:37–41. [in Chinese] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1.

The questionnaire of transcultural adaptation of Tibetan nursing trainees.

| Serial number | Questions | Answers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Gender | Male | Female | |||

| Q2 | Student source region | Urban | Rural or grazing district | Urban rural fringe area | ||

| Q3 | One-child family | Yes | No | |||

| Q4 | City administration level where the internship hospital was located | Provincial capital city | Prefecture level city | County level city | Rural area | |

| Q5 | Very adaptable to the area where you practice | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q6 | In daily communication, you are not confused about the cultural environment of your internship area | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q7 | Very adaptable to the hospital environment of practice | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q8 | Often interact with students of different ethnic groups who are interning together | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q9 | Have no difficulty in communicating with students of different nationalities | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q10 | Consider the appropriate ways and methods to communicate with students of different nationalities | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q11 | Harmonious relationship with teachers of different nationalities in practice hospitals | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q12 | Often communicate with teachers of different nationalities | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q13 | When encountering difficulties in life and practice, we can get help from teachers of other nationalities | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q14 | There is no difficulty in communicating with the family members of patients of different nationalities | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q15 | Often discuss the condition with patients of different nationalities or their families | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q16 | Be able to understand the patient or the patient’s expression of their condition | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q17 | Teachers of different nationalities can consider students’ cultural background in teaching design | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q18 | Teachers usually try their best to hang educational content close to the life of students in ethnic areas | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q19 | Teachers can pay attention to the differences of national cultural background when arranging internship tasks | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q20 | To be able to use local traditional customs to guide students in cultural integration cognition | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q21 | The students of different nationalities can be reasonably evaluated in terms of internship tasks | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q22 | Can often reflect on their own internship results | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q23 | In the process of practice, our national culture can receive respect | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q24 | In the process of practice, I can also respect the cultural customs of different nationalities | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q25 | Teachers can provide opportunities to learn about the democratic culture and other national cultures | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q26 | Practice hospitals can pay attention to the learning needs of students of different nationalities | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Uncertainty | Agree | Strongly agree |

| Q27 | I feel down-hearted and blue | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q28 | Morning is When I feel the best | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q29 | I have crying spells or feel like it | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q30 | I have trouble sleeping at night | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q31 | I eat as much as I used to | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q32 | I am as happy as ever in close contact with the opposite sex | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q33 | I’ve noticed that I’m losing weight | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q34 | I have trouble with constipation | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q35 | My heart beats faster than usual | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q36 | I feel tired for no reason | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q37 | My mind is as clear as it used to be | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q38 | I find it easy to do the thing I used to | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q39 | I am restless and cannot keep still | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q40 | I feel hopeful about the future | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q41 | I am more irritable than usual | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q42 | I find it easy to make a decision | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q43 | I feel that I’m useful and needed | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q44 | My life is pretty full | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q45 | I feel that others would be better off if I were dead | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |

| Q46 | I still enjoy the things I used to do | A little of the time | Some of the time | Good part of the time | Most of the time | |