Abstract

BACKGROUND:

After acute ischemic stroke, a higher level of troponin has been considered as an important biomarker for predicting mortality.

AIM AND OBJECTIVES:

The study aimed to quantitatively assess the prognostic significance of the effect of baseline troponin levels on all-cause mortality in patients with acute ischemic stroke using a meta-analysis approach.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

The following electronic databases such as PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, TRIP Database, and ClinicalTrialsgov were used for obtaining the relevant articles from literature. Data were extracted in standardized data collection form by two independent investigators. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus. All the statistical analyses were performed in STATA software (Version 13.1).

RESULTS:

A total of 19 studies were included in the present meta-analysis involving a total of 10,519 patients. The pooled analysis suggested that elevated serum troponin level was associated with inhospital mortality (rate ratios [RR] 2.34, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.30–3.38) and at the end of last follow-up mortality (RR 2.01; 95% CI 1.62–2.40). Sensitivity analysis by removing a single study by turns indicated that there was no obvious impact of any individual study on the pooled risk estimate. No significant publication bias was observed in the beg test (P = 0.39); however, significant publication bias was observed in the egger test (P = 0.046).

CONCLUSION:

Our findings indicated that a higher level of troponin might be an important prognostic biomarker for all cause in hospital and follow-up mortalities in patients with acute ischemic stroke. These study findings offer insight into further investigation in prospective studies to validate this particular association. The study was registered in OSF registries DOI's 10.17605/OSF. IO/D95GN

Keywords: Biomarker, meta-analysis, outcome prediction, stroke, troponin

Introduction

There might be an association between brain damage and cardiac cell death, but it remains poorly understood.[1,2] Cardiac troponin T (cTnT) and cardiac troponin I (cTnI) are currently useful for the detection of myocardial injury.[3] High serum troponin levels in patients with spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage have extensively been documented,[4,5] and current studies observed its association with a stunned myocardium, resulting in pump failure and thereby congestive heart failure.[2,4] A high troponin level is common in the acute phase of ischemic stroke which indicates a close relationship between stroke and cardiac damage.[6] It may be noted that an increase in troponin level may be explained by comorbidities associated with some stroke patients. Recent studies have established a linkage between elevated blood troponin levels and death in patients with ischemic stroke.[7] However, inconsistent evidence is available in the literature on the association of elevated cardiac troponin with mortality in patients with acute ischemic stroke.[8,9] It is essential to determine the prognostic significance of baseline blood cardiac troponin levels in the acute phase in patients with ischemic stroke before its clinical implications. The previous meta-analysis was conducted with a smaller number of studies and could not establish the independent association of acute-phase troponin level with all-cause mortality.[10] Therefore, the prognostic significance of cardiac troponin in patients with acute ischemic stroke remains conflicting. Several studies on the association between troponin level and its prognostic significance in stroke have been published after an earlier published meta-analysis. Therefore, we have conducted an updated meta-analysis to determine the precise association of a higher level of troponin at the acute phase of stroke with all-cause inhospital mortality and follow-up mortality in patients with acute ischemic stroke.

Methods

Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis statement for conducting meta-analysis were followed for reporting meta-analysis findings.

Hypothesis

Elevated levels of troponin at the acute phase of acute ischemic stroke might be an important prognostic biomarker for all-cause mortality.

Population

Studies recruited subjects with acute ischemic stroke.

Indicator

Elevated troponin levels were used as an indicator at the acute phase of the stroke.

Comparison

Comparison was made low baseline acute phase troponin versus high troponin level.

Outcome

The outcome was all-cause inhospital mortality or mortality at follow-up.

Study design

This study was a meta-analysis artcle.

Literature search

The following electronic databases such as PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, TRIP Database, and ClinicalTrials.gov were used for obtaining the relevant articles from literature from the year 2000 onward to May 2020. The following combinations of search keywords were used for obtaining the relevant articles from literature “Troponin” AND “prognosis” OR “outcome” OR “mortality” AND “brain stroke” OR “ischemic stroke” OR “cerebral infarction.” Filters were applied to human studies, clinical trials, and subjects with age 18 above. No language barrier was applied. Manual searches of the references list of the retrieved articles were also conducted. The study was registered in OSF registries DOI's 10.17605/OSF. IO/D95GN. Data were extracted in standardized data collection by two independent investigators. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Ethics committee approval

It was not applicable as this is a meta-analysis article.

Study eligibility

Inclusion Criteria

Studies were included if they fulfill the following inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria:

Study design: Observational studies (prospective or retrospective)

Participants: Studies included subjects with acute ischemic stroke

Exposure: Studies should have reported at least a one-time assay of the blood level of cTnT or cTnI at the time of admission

Outcome measure: Studies reported inhospital mortality or mortality at the last follow-up.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if conducted on patients with hemorrhagic stroke and insufficient data to extract the exposure and outcome data.

Statistical analyses

The random-effects model was used in case of heterogeneity of more than 50%; otherwise, a fixed-effects model was applied to determine the pooled estimate of effect size. To examine the methodological quality, we used the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for included studies in the meta-analysis.[11] Pooled estimates reported as a hazard ratio (HR) with a 95% confidence interval [CI]. I-square was used to measure heterogeneity. All the statistical analyses were conducted using software STATA version 13.0 (StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP).

Results

Search results

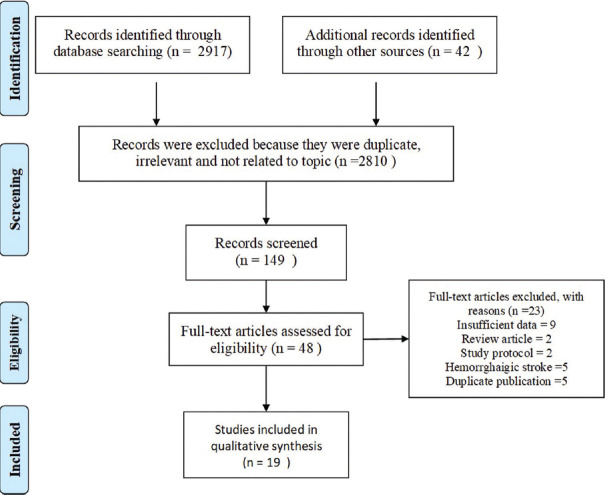

Our initial search identified a total of 2,959 studies using electronic database searching and manual search. After screening titles and abstracts, 2,810 articles were excluded because they were either irrelevant or not related to the topic, resulting in 149 articles for further review. After screening them, 101 articles were further removed, yielding a total of 48 articles. Full text of all these 48 articles was downloaded and reviewed extensively, yielding 19 articles to be included in the present meta-analysis involving a total of 10,519 subjects. The flowchart for the selection of relevant studies is given in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram

Characteristics of included studies

Nineteen studies were included in the final meta-analysis. In the present meta-analysis, two studies were from Norway,[8,12] one from China,[13] two from Denmark,[14,15] two from Germany,[16,17] one from Israel,[18] one from Italy,[7] one from Korea,[19] one from New Zealand,[9] two from Poland,[20,21] one from Slovenia,[22] one from Spain,[23] one from Taiwan,[24] one from the UK,[25] and two from the USA.[26,27] Among all twelve were prospective cohort study[7,9,12,13,14,15,16,20,21,22,25,27] and seven were retrospective cohort study.[8,17,18,19,23,24,26] Studies included a minimum of 40[12] to a maximum of 1,718[27] patients. Baseline characteristics of the included studies considered in the present study are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the included studies in the meta-analysis

| Authors | Country | Study design | Mean age±SD | Patients | Cutoff value | Type of assay | Abnormal cTn (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trooyen et al., 2001[12] | Norway | PCS | - | 40 | >0.4 µg/L | cTnI | - |

| James et al., 2000[9] | New Zealand | PCS | 82 | 181 | >0.1 | cTnT | - |

| Guerrero-peral et al., 2002[23] | Spain | RCS | - | 42 | 0.1 | cTnT | - |

| Maliszewska et al., 2005[21] | Poland | PCS | - | 196 | >0.1 | cTnI | - |

| Di Angelantonio et al., 2005[7] | Italy | PCS | 56.6±12.9 | 330 | 0.1 ng/ml | cTnI | 16.3 |

| Jensen et al., 2007[14] | Denmark | PCS | 68.7±13.1 | 244 | 0.03 µg/L | cTnT | 10 |

| Barber et al., 2007[25] | UK | PCS | 73 | 222 | >0.2 µg/L | cTn1 | |

| Scheitz et al., 2012[17] | Germany | RCS | 66 to 84 | 715 | 0.03 µg/L | cTnT | 14 |

| Hajdinjak et al., 2012[22] | Slovenia | PCS | 70±12.1 | 106 | 0.04 µg/L | cTnT | 15.1 |

| Jensen et al., 2012[15] | Denmark | PCS | 69.4±12.1 | 193 | 14 ng/mL | HS-cTnT | 33.7 |

| Scheitz et al., 2014[16] | Germany | PCS | 61–88 | 1016 | 14 ng/ml | Hs-cTnT | 60 |

| Faiz et al., 2014[8] | Norway | RCS | 65-83 | 287 | 14 ng/ml | HS-cTnT | 54.4 |

| Lasek-Bal et al., 2014[20] | Poland | PCS | 72±11 | 1068 | 0.014 ng/ml | HS-cTnI | 9.7 |

| Maoz et al., 2015[18] | Israel | RCS | 73.9±12.9 | 212 | 0.03 µg/L | HS-cTnT | 16.5 |

| Peddada et al., 2016[26] | USA | RCS | 65±15 | 1145 | 0.12 ng/ml | HS-cTnI | 17.0 |

| Su et al., 2016[24] | Taiwan | RCS | 72.3±13.6 | 871 | 0.01 µg/L | cTnI | 16.8 |

| Batal et al., 2016[27] | USA | PCS | 67±15 | 1718 | 0.10 µg/L | cTnI | 18 |

| Sung et al., 2017[19] | Korea | RCS | 66±12.4 | 1692 | >0.004 ng/ml | cTnI | - |

| Sui et al., 2019 [13] | China | PCS | 76 | 241 | 14 ng/L | HS-cTnT | - |

SD: Standard deviation, cTnI: Cardiac troponin I, cTnT: Cardiac troponin, HS: High-sensitivity, PCS: Prospective cohort study, RCS: Retrospective cohort study

Meta-analysis findings

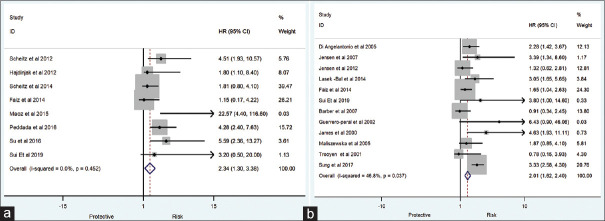

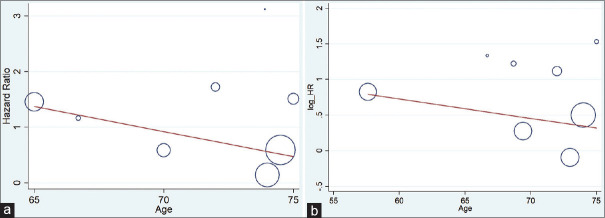

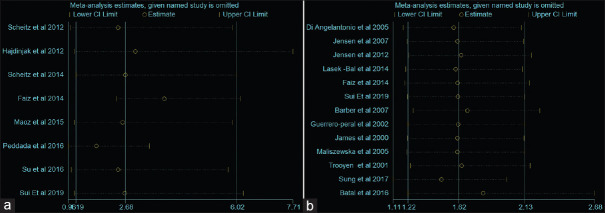

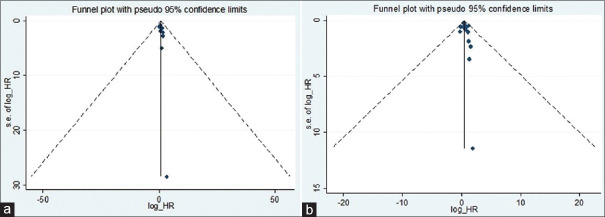

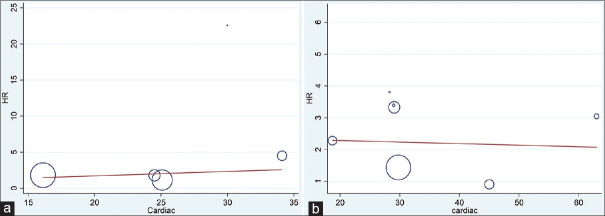

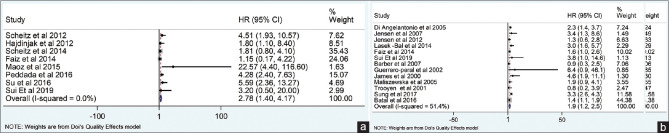

The present meta-analysis findings suggested that the elevated blood troponin levels in acute ischemic stroke are significantly increased the risk of inhospital mortality (HR 2.34, 95% CI 1.30–3.38) [Figure 2a] and also at the last follow-up mortality (HR 2.01; 95% CI 1.62–2.40) [Figure 2b]. Meta-regression analysis did not observe a significant effect of age on the effect size associated with inhospital mortality (P = 0.57) [Figure 3a] and at the end of last follow-up mortality (P = 0.61) [Figure 3b]. Sensitivity analysis by removing a single study by turns indicated that there was no obvious impact of any individual study on the pooled risk estimate in inhospital mortality [Figure 4a] and follow-up mortality [Figure 4b]. No asymmetry was observed in funnel plots in the case of inhospital mortality [Figure 5a] and follow-up mortality [Figure 5b].

Figure 2.

(a) Association of acute-phase troponin level with inhospital mortality. (b) Association of acute-phase troponin level with last follow up mortality

Figure 3.

(a) Meta-regression analysis (effect of age on the effect size associated with inhospital mortality). (b) Meta-regression analysis (effect of age on the effect size associated with last follow up mortality)associated with last follow up mortality)

Figure 4.

(a) Sensitivity analysis for association of high troponin level with inhospital mortality. (b) Sensitivity analysis for association of high troponin level with follow-up mortality

Figure 5.

(a) Funnel plot showing no significant publication bias for outcome inhospital mortality. (b) Funnel plot showing no significant publication bias at the end of follow-up mortalitymortality

The presence of cardiac disease in stroke patients may confound the meta-analysis findings. Hence, we used meta-regression analysis keeping the percentage of cardiac disease as a moderator variable for determining an independent association between high baseline troponin and inhospital or follow-up all-cause mortality. In the meta-regression analysis, we did not observe the significant confounding effect of the presence of cardiac disease on inhospital (P = 0.61) and follow-up mortalities (P = 0.89) [Figure 6a and b].

Figure 6.

(a) Association of acute-phase troponin level with inhospital mortality after adjustment of confounding effect of the presence of cardiac disease. (b) Association of acute-phase troponin level with follow-up mortality after adjustment of confounding effect of the presence of cardiac diseaseacute-phase troponin level with follow-up mortality after adjustment of confounding effect of the presence of cardiac disease

The methodological quality of studies included in the meta-analysis using the Newcastle–Ottawa Methodological Quality Scale score varies from 6 to 8 [Table 2]. We also used the quality-effects model in which we observed no significant effect of methodological quality for the findings observed for both inhospital and follow-up mortalities [Figure 7a and 7b].

Table 2.

Methodological quality of studies included in the meta-analysis using Newcastle–Ottawa Methodological Quality Scale

| Studies | Respersentativive of the exposed cohort | Selection of the non-exposed cohort | Ascertainment of exposure | Demonstration that outcome was not present at study start | Comparability of cohorts based on design or analysis | Assessment of outcome | Enough follow up period (>1 year | Adequacy of follow up | Overall NOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trooyen et al., 2001[12] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||

| James et al., 2000[9] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |

| Guerrero-peral et al., 2002[23] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||

| Maliszewska et al., 2005[21] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |

| Di Angelantonio et al., 2005[7] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Jensen et al., 2007[14] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |

| Barber et al., 2007[25] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |

| Scheitz et al., 2012[17] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |

| Hajdinjak et al., 2012[22] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||

| Jensen et al., 2012[15] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |

| Scheitz et al., 2014[16] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||

| Faiz et al., 2014[8] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||

| Lasek -Bal et al., 2014[20] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||

| Maoz et al., 2015[18] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||

| Peddada et al., 2016[26] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||

| Su et al., 2016[24] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||

| Batal et al., 2016[27] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |

| Sung et al., 2017[19] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Sui et al., 2019[13] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

NOS: Newcastle–Ottawa Scale

Figure 7.

(a) Quality-effects model associated with follow-up mortality. (b) Quality-effects model associated with the last follow-up mortality

Discussion

The findings of the present study demonstrated that elevated troponin levels are statistically significantly associated with inhospital and at the end of last follow-up mortalities.

Several studies have shown elevated levels of troponin enzymes in patients with acute ischemic stroke.[28] Preclinical studies and observations made in the patients with the critical nonneurological illness have led to the theory, this represents cardiac injury due to elevated levels of circulating catecholamine.[29] The available evidence supports the hypothesis that catecholamine causes cardiac injury.[30] Elevated troponin level results in the nonspecific physiologic stress response.[29] An earlier meta-analysis demonstrated that elevated levels of troponin at baseline result in higher inhospital mortality in patients with ischemic stroke.[28] The finding of the current meta-analysis also observed similar findings which suggest that elevated levels of troponin is a predictor for in-mortality and follow-up mortalities.

Previously published studies in literature observed that elevated troponin level is associated with all-cause mortality in all types of stroke.[15,17] A study showed that baseline troponin level was also found to be a predictor of poor outcomes in inhospital and last follow-up,[31] irrespective of the acute coronary syndrome.[32] Higher blood troponin level during the acute phase in the patient with acute spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage was also found to be linked with poor outcome.[33,34] A meta-analysis also demonstrated an increased risk of cerebral ischemia and death in patients with spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage.[35] A recently published meta-analysis involving 12 studies consisting of 7,905 subjects also observed that baseline elevated troponin levels associated with all-cause mortality in patients with acute ischemic stroke.[10] The present updated meta-analysis included 19 studies involving a total of 1,0519 subjects, also supports the finding observed in the previous meta-analysis which indicated the prognostic significance of elevated troponin level at baseline for ischemic stroke patients. Stratified analysis in the present study suggests the risk of mortality is higher in inhospital patients as compared to follow-up mortality. Considering the presence of cardiac disease at the acute stage of stroke may disrupt the association observed in the present study, we adjusted the confounding effects caused due to cardiac disease in the meta-regression analysis. The absence of a significant confounding effect was noted down in the association observed in the present study further strengthen the independent prognostic significance of baseline troponin level for predicting inhospital or follow-up mortality. Our quality-effects model also observed the significant role of higher troponin levels as a prognostic factor at baseline for predicting mortality after acute ischemic stroke.

Our study has clinical relevance in terms of determining the predictive power of baseline troponin in cases with acute ischemic stroke. Higher troponin levels in the acute time of the event can help in the stratification of patients with ischemic stroke for predicting poststroke mortality. Comorbid risk factors may be assessed in case of higher troponin levels at baseline for the management of patients with stroke.

Limitation of the study

The study has several limitations (1) individual patient data were not available to adjust the confounding effect of variables; therefore, the risk may be overestimated in the present study, (2) differences in cutoff values, assay method, and follow-up period in the individual studies may have contributed to heterogeneity in the present study, (3) prognostic significance of troponin value may vary as per different subtypes of ischemic stroke; therefore, the finding of the present study could not be generalized in all ischemic stroke cases, and (4) the other influential factors like the presence of cardiac disease data may disrupt the association noted down in the study, although we adjusted its confounding effects in meta-regression analysis. Although we have used robust methodologies, the differences in ethnicity, race, the severity of the stroke, the intervention performed, and associated comorbidities limit the generalizability of the study findings.

A higher blood level of cardiac troponin during the acute phase of ischemic stroke has the potential to become a useful predictor for inhospital mortality and follow-up mortality. The findings of the current meta-analysis provide a signal that it is worthwhile to conduct further larger prospective studies specifically designed to validate the findings observed in the current meta-analysis.

Conclusion

Our meta-analysis indicates that a higher level of troponin during the acute phase of ischemic stroke might be an important prognostic biomarker for mortality prediction. The study might have clinical implications of using troponin as a prognostic biomarker for patient stratification and early intervention. Knowledge of predictive factors of mortality and functional outcomes after acute ischemic stroke is important for optimal planning of poststroke care. Further, well-designed randomized prospective prognostic studies are needed to validate the findings observed in the present meta-analysis.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors extend their appreciation to College of Medicine Research Center, Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University for funding this research work.

References

- 1.Cheung RT, Hachinski V. The insula and cerebrogenic sudden death. Arch Neurol. 2000;57:1685–8. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.12.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tung P, Kopelnik A, Banki N, Ong K, Ko N, Lawton MT, et al. Predictors of neurocardiogenic injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2004;35:548–51. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000114874.96688.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams JE, 3rd, Bodor GS, Dávila-Román VG, Delmez JA, Apple FS, Ladenson JH, et al. Cardiac troponin I.A marker with high specificity for cardiac injury. Circulation. 1993;88:101–6. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deibert E, Aiyagari V, Diringer MN. Reversible left ventricular dysfunction associated with raised troponin I after subarachnoid haemorrhage does not preclude successful heart transplantation. Heart Br Card Soc. 2000;84:205–7. doi: 10.1136/heart.84.2.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Espiner EA, Leikis R, Ferch RD, MacFarlane MR, Bonkowski JA, Frampton CM, et al. The neuro-cardio-endocrine response to acute subarachnoid haemorrhage. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2002;56:629–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2002.01285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eggers KM, Lindahl B. Application of cardiac troponin in cardiovascular diseases other than acute coronary syndrome. Clin Chem. 2017;63:223–35. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2016.261495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Angelantonio E, Fiorelli M, Toni D, Sacchetti ML, Lorenzano S, Falcou A, et al. Prognostic significance of admission levels of troponin I in patients with acute ischaemic stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:76–81. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.041491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faiz KW, Thommessen B, Einvik G, Brekke PH, Omland T, Rønning OM. Determinants of high sensitivity cardiac troponin T elevation in acute ischemic stroke. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:96. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-14-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.James P. Relation between troponin T concentration and mortality in patients presenting with an acute stroke: Observational study. BMJ. 2000;320:1502–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7248.1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan Y, Jiang M, Gong D, Man C, Chen Y. Cardiac troponin for predicting all-cause mortality in patients with acute ischemic stroke: A meta-analysis. Biosci Rep. 2018;38:BSR20171178. doi: 10.1042/BSR20171178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wells G, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The 31 Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality if Nonrandomized Studies in Meta-analyses, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. [[Last accessed on 2020 Mar 06]]. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp .

- 12.Troøyen M, Indredavik B, Rossvoll O, Slørdahl SA. Myokardskade ved akutte hjerneslag bedømt med troponin I. Tidsskr Den Nor Legeforening. 2001;121:421–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sui Y, Liu T, Luo J, Xu B, Zheng L, Zhao W, et al. Elevation of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T at admission is associated with increased 3-month mortality in acute ischemic stroke patients treated with thrombolysis. Clin Cardiol. 2019;42:881–8. doi: 10.1002/clc.23237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jensen JK, Kristensen SR, Bak S, Atar D, Høilund-Carlsen PF, Mickley H. Frequency and significance of troponin T elevation in acute ischemic stroke. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:108–12. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jensen JK, Ueland T, Aukrust P, Antonsen L, Kristensen SR, Januzzi JL, et al. Highly sensitive troponin T in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Eur Neurol. 2012;68:287–93. doi: 10.1159/000341340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scheitz JF, Mochmann HC, Erdur H, Tütüncü S, Haeusler KG, Grittner U, et al. Prognostic relevance of cardiac troponin T levels and their dynamic changes measured with a high-sensitivity assay in acute ischaemic stroke: Analyses from the TRELAS cohort? Int J Cardiol. 2014;177:886–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.10.036. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scheitz JF, Endres M, Mochmann HC, Audebert HJ, Nolte CH. Frequency, determinants and outcome of elevated troponin in acute ischemic stroke patients. Int J Cardiol. 2012;157:239–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maoz A, Rosenberg S, Leker RR. Increased high-sensitivity troponin-T levels are associated with mortality after ischemic stroke. J Mol Neurosci. 2015;57:160–5. doi: 10.1007/s12031-015-0593-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahn SH, Lee JS, Kim YH, Kim BJ, Kim YJ, Kang DW, et al. Prognostic significance of troponin elevation for long-term mortality after ischemic stroke. J Stroke. 2017;19:312–22. doi: 10.5853/jos.2016.01942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lasek-Bal A, Kowalewska-Twardela T, Gąsior Z, Warsz-Wianecka A, Haberka M, Puz P, et al. The significance of troponin elevation for the clinical course and outcome of first-ever ischaemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis Basel Switz. 2014;38:212–8. doi: 10.1159/000365839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maliszewska M, Fiszer U, Palasik W, Tadeusiak W, Morton M. Prognostic role of troponin I level in ischemic stroke – Preliminary report. Pol Merkur Lek Organ Pol Tow Lek. 2005;19:158–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hajdinjak E, Klemen P, Grmec S. Prognostic value of a single prehospital measurement of N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide and troponin T after acute ischaemic stroke. J Int Med Res. 2012;40:768–76. doi: 10.1177/147323001204000243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.S.L.U. Viguera., editor. Determinación de Marcadores Específicos de Lesión Miocárdica en la Enfermedad Cerebrovascular. Rev Neurol. 2002;35:901–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Su YC, Huang KF, Yang FY, Lin SK. Elevation of troponin I in acute ischemic stroke. Peer J. 2016;4:e1866. doi: 10.7717/peerj.1866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barber M, Morton JJ, Macfarlane PW, Barlow N, Roditi G, Stott DJ. Elevated troponin levels are associated with sympathoadrenal activation in acute ischaemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007;23:260–6. doi: 10.1159/000098325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peddada K, Cruz-Flores S, Goldstein LB, Feen E, Kennedy KF, Heuring T, et al. Ischemic stroke with troponin elevation: Patient characteristics, resource utilization, and in-hospital outcomes. Cerebrovasc Dis Basel Switz. 2016;42:213–23. doi: 10.1159/000445526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Batal O, Jentzer J, Balaney B, Kolia N, Hickey G, Dardari Z, et al. The prognostic significance of troponin I elevation in acute ischemic stroke. J Crit Care. 2016;31:41–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Broersen LH, Stengl H, Nolte CH, Westermann D, Endres M, Siegerink B, et al. Association between high-sensitivity cardiac troponin and risk of stroke in 96 702 individuals: A meta-analysis. Stroke. 2020;51:1085–93. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.028323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen Z, Venkat P, Seyfried D, Chopp M, Yan T, Chen J. Brain-heart interaction: Cardiac complications after stroke. Circ Res. 2017;121:451–68. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wallner M, Duran JM, Mohsin S, Troupes CD, Vanhoutte D, Borghetti G, et al. Acute catecholamine exposure causes reversible myocyte injury without cardiac regeneration. Circ Res. 2016;119:865–79. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hjalmarsson C, Bokemark L, Fredriksson S, Antonsson J, Shadman A, Andersson B. Can prolonged QTc and cTNT level predict the acute and long-term prognosis of stroke? Int J Cardiol. 2012;155:414–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raza F, Alkhouli M, Sandhu P, Bhatt R, Bove AA. Elevated cardiac troponin in acute stroke without acute coronary syndrome predicts long-term adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Stroke Res Treat. 2014;2014:621650. doi: 10.1155/2014/621650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hays A, Diringer MN. Elevated troponin levels are associated with higher mortality following intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 2006;66:1330–4. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000210523.22944.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garrett MC, Komotar RJ, Starke RM, Doshi D, Otten ML, Connolly ES. Elevated troponin levels are predictive of mortality in surgical intracerebral hemorrhage patients. Neurocrit Care. 2010;12:199–203. doi: 10.1007/s12028-009-9245-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang L, Wang Z, Qi S. Cardiac troponin elevation and outcome after subarachnoid hemorrhage: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;24:2375–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]