Abstract

Background:

Approximately one in four women veterans accessing the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) engage in unhealthy alcohol use. There is substantial evidence for gender-sensitive screening (AUDIT-C=3) and brief intervention (BI) to reduce risks associated with unhealthy alcohol use in women veterans; however, VA policies and incentives remain gender-neutral (AUDIT-C=5). Women veterans who screen positive at lower-risk-level alcohol use (AUDIT-C=3 or 4) may screen out and therefore not receive BI. This study aimed to examine gaps in implementation of BI practice for women veterans through identifying rates of BI at different alcohol risk levels (AUDIT-C=3–4; =5–7; =8–12), and the role of alcohol risk level and other factors in predicting receipt of BI.

Methods:

From administrative data (2010–2016), we drew a sample of women veterans returning from recent wars who accessed outpatient and/or inpatient care. Of 869 women veterans, 284 screened positive for unhealthy alcohol use at or above a gender-sensitive cut-point (AUDIT-C≥3). We used chart review methods to abstract variables from the medical record and then employed logistic regression comparing women veterans who received BI at varying alcohol risk levels to those who did not.

Results:

While almost 60% of the alcohol positive-risk sample received BI, among the subset of women veterans who screened positive for lower-risk alcohol use (57%; AUDIT-C=3 or 4) only 34% received BI. Other types of clinicians (e.g., physicians, psychologists, social workers) in mental health programs and mixed-gender programs were more likely to deliver BI than nurses in primary care and women’s health programs; further, those women veterans with more medical problems were no more likely to receive BI than those with fewer medical problems.

Conclusions:

Given that women veterans are a rapidly growing veteran population and a VA priority, underuse of BI for women veterans screening positive at a lower-risk level and for those with more medical comorbidities requires attention, as do potential gaps in service delivery of BI in primary care and women’s health programs. Women veterans’ health and well-being may be improved by tailoring screening for a younger cohort of women veterans at high-risk for or with co-occurring disorders and then training providers in best practices for BI implementation.

Keywords: Unhealthy alcohol use, Brief intervention, Women, Veterans, Gender

1. Background

About one in four women veterans (27%) accessing the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system engage in unhealthy alcohol use (Hoggatt, Williams, Der-Martirosian, Yano, Washington, 2015). Without timely identification and intervention, the effects of unhealthy alcohol use in women veterans can lead to adverse outcomes (Ait-Daoud et al., 2017; Chavez et al., 2012; Scoccianti et al., 2014). Brief intervention (BI) includes provider-delivered brief counseling, such as motivational interviewing or brief advice and feedback regarding the effects of unhealthy alcohol use on health and well-being; these practices are effective in reducing alcohol use in women who drink at low to moderate rates (Ballesteros et al., 2004; Gebara et al., 2013; Jonas et al., 2012; Kaner et al., 2018). Congress mandates the VA to deliver one type of BI, motivational interviewing, to veterans who screen positive for unhealthy use (US Congress, 2008). To identify women who may benefit from BI, a gender-sensitive cut-point on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption (AUDIT-C) =3 is recommended for women veterans in the VA’s national clinical substance use disorder guidelines (Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense, 2009, 2015).

While the VA clinical reminder is also gender-sensitive, decision rules (e.g. cut-point for performance measures) that incentivize implementation of BI remain gender-neutral (AUDIT-C ≥ 5; Bradley et al., 2003; Bradley et al., 2006; Grossbard et al., 2013). This gender-neutral cut-point, while higher than optimal for women veterans, was selected due to low population prevalence of women veterans and concern for the potential cost of false positive screens (Bradley et al., 2007; Bradley et al., 2006; Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense, 2009). Conflicting messages about the ideal threshold at which to deliver the BI to women veterans may confuse providers about when to implement the BI for women veterans (e.g., due to discrepancies between definitions of the terms for alcohol drinking patterns, AUDIT-C scores, risk levels, VA guidelines, and performance measures for women veterans; Table 1).

Table 1.

Definitions of the spectrum of unhealthy alcohol use.

| Term | Definition | AUDIT-C score | Risk level | VA SUD guidelines | VA performance measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unhealthy alcohol use | The entire spectrum from risky drinking to alcohol use disorders | 2–12 (female) 3–12 (male) | Lower-risk to hazardous use | ||

| Risky drinking | Drinking above the recommended limits: Men ≥14 drinks/week or ≥4 drinks on one occasion. Women ≥7 drinks/week or ≥3 drinks on one occasion | 2–3 (female) 3 −4 (male) | Lower to moderate-risk | AUDIT-C ≥3 BI female | |

| Problem drinking | Use of alcohol accompanied by alcohol-related consequences but not meeting ICD-10 or DSM-IV criteria; sometimes used to refer to the spectrum of unhealthy use but usually excludes dependence | 4–7 (female) 5–7 (male) | Moderate to high-risk | AUDIT-C ≥4 BI female | AUDIT-C ≥5 BI and/or Referral to Treatment (RT) |

| Alcohol use disorders | A chronic maladaptive pattern of alcohol use that meets diagnostic criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence | 8 or more (female & male) | Severe risk/Hazardous use | AUDIT-C ≥8 BI, and RT | AUDIT-C ≥8 BI and/or RT |

Note. Definitions adapted from “Implementation of Evidence-Based Alcohol Screening in the Veterans Health Administration” by K. Bradley, E. C. Williams, C. E. Achtmeyer, B. Volpp, B. J. Collins, & D. R. Kivlahan, 2006, American Journal of Managed Care, 12(10), p. 598. Copyright 2006 by Managed Care & Healthcare Communications, LLC. Also, adapted from “Unhealthy Alcohol Use” by R. Saitz, 2005, New England Journal of Medicine, 352(6) p. 597. Copyright 2005 by Massachusetts Medical Society.

A gender-sensitive threshold for identifying women drinking at lower risk levels is crucial because such lower-risk alcohol consumption is still associated with substantial harms. In this study, we defined positive risk levels as low-risk, moderate-risk, and high-risk, and we refer to these terms interchangeably as unhealthy alcohol use; for the specific cut-points that we employed see Methods. Low-risk alcohol use among women is associated with a 14% increased risk of developing breast cancer (Rehm et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2007), a 40% increased risk of developing hypertensive disease, and a 34% increased risk of developing diabetes (Rehm et al., 2003), compared to risks for women who abstain from alcohol. Further, for women, the minimum risk of cancer-related mortality is 1–2 drinks once monthly, and for all-cause mortality 1–2 drinks 2.7 times weekly (Hartz et al., 2018); although these amounts are within limits of the guidelines for healthy drinking (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [NIAAA], 2007, 2016). Alcohol disease processes develop differently in women compared to men (e.g., metabolizing of alcohol; Ait-Daoud et al., 2017; Johnson et al., 2014). A consequence of this difference is that women are at higher risk for alcohol-related health problems even when they drink at lower rates than men (McCaul et al., 2019; NIAAA, 2007).

Women who screen positive for unhealthy alcohol use and have had care on an inpatient unit (e.g., medical-surgical, substance use residential, inpatient detoxification, or psychiatric unit) could indicate that the patient has a more acute risk level for a comorbid health or mental health condition (Mee-Lee, 2013) that requires further assessment or a referral to treatment.

Previous research has established that women veterans require differential screening and BI practices than male Veterans (Bradley et al., 2003; Bradley et al., 2006; Chavez et al., 2012; Cucciare et al., 2013; Sanchez-Craig, Wilkinson & Davila, 1995). Williams and colleagues (2017) found that use of a gender-neutral threshold is associated with receipt of BI at a rate that is 3 times higher for men than women. Additionally, when VA providers are incentivized to deliver BI only to those women veterans who meet or exceed a positive screen with an AUDIT-C score of 5, 67% of women veterans who drink at low-risk—scoring positive at a 3 or 4 on the AUDIT-C—do not receive BI (Williams et al., 2017). This lost opportunity to deliver BI for women veterans may challenge the well-being of women veterans because of the health-related risks of low-risk drinking for women. Hoggatt and colleagues (2018) found by lowering the AUDIT-C binge drinking question in the VA clinical reminder for women veterans from ≥ 6 drinks to ≥ 4 drinks on one occasion, the identification rate of screening for women veterans increased by 15%. Further, modifying the cut-point to a gender-sensitive one increased the rate of identification by an additional 3 percentage points (Hoggatt et al., 2018).

Examining predictors of BI at different positive alcohol risk levels is a step towards identifying how to improve the quality of BI implementation for women; most literature to date has addressed largely male veteran samples (Calhoun et al., 2008, Hawkins et al., 2010). There is a small body of literature on person-level predictors of BI delivery in women veterans who access VA care, and no known literature on systems-level predictors (Bradley et al., 2007; Williams et al., 2014). Learning more about what types of programs and providers are delivering BI may guide implementation research. Additionally, evaluating the VA’s response to unhealthy alcohol use in a cohort of women with inpatient and outpatient care may contribute to efforts to support women veterans’ well-being. We, therefore, sought to examine predictors of BI in a sample of women veterans from recent wars who screen positive for unhealthy alcohol use (AUDIT-C ≥3) in both ambulatory care (i.e., mental health, primary care,) and inpatient settings (including medical-surgical units, residential substance use disorder [SUD] treatment, medical detoxification, and residential mental health [MH] programs). Research questions included: 1) What percentage of women veterans with unhealthy alcohol use receive BI? 2) Does the rate of BI differ by severity of the patient’s AUDIT-C score? 3) Does the use of BI with women veterans differ by the patient’s number of medical problems? 4) Does the use of BI with women veterans who screen positive for unhealthy alcohol use differ by provider type? and 5) Does the use of BI differ between primary care programs and other types of programs (i.e., inpatient MH and SUD) or between women veteran-only programs and other programs (i.e., mixed-gender)?

2. Methods

This is a retrospective, cross-sectional study of data from one VA Medical Center that examines patient-, provider-, and program-level variables using administrative data and chart review. The Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) at VA Boston and Brandeis University approved this study.

2.1. Study sample

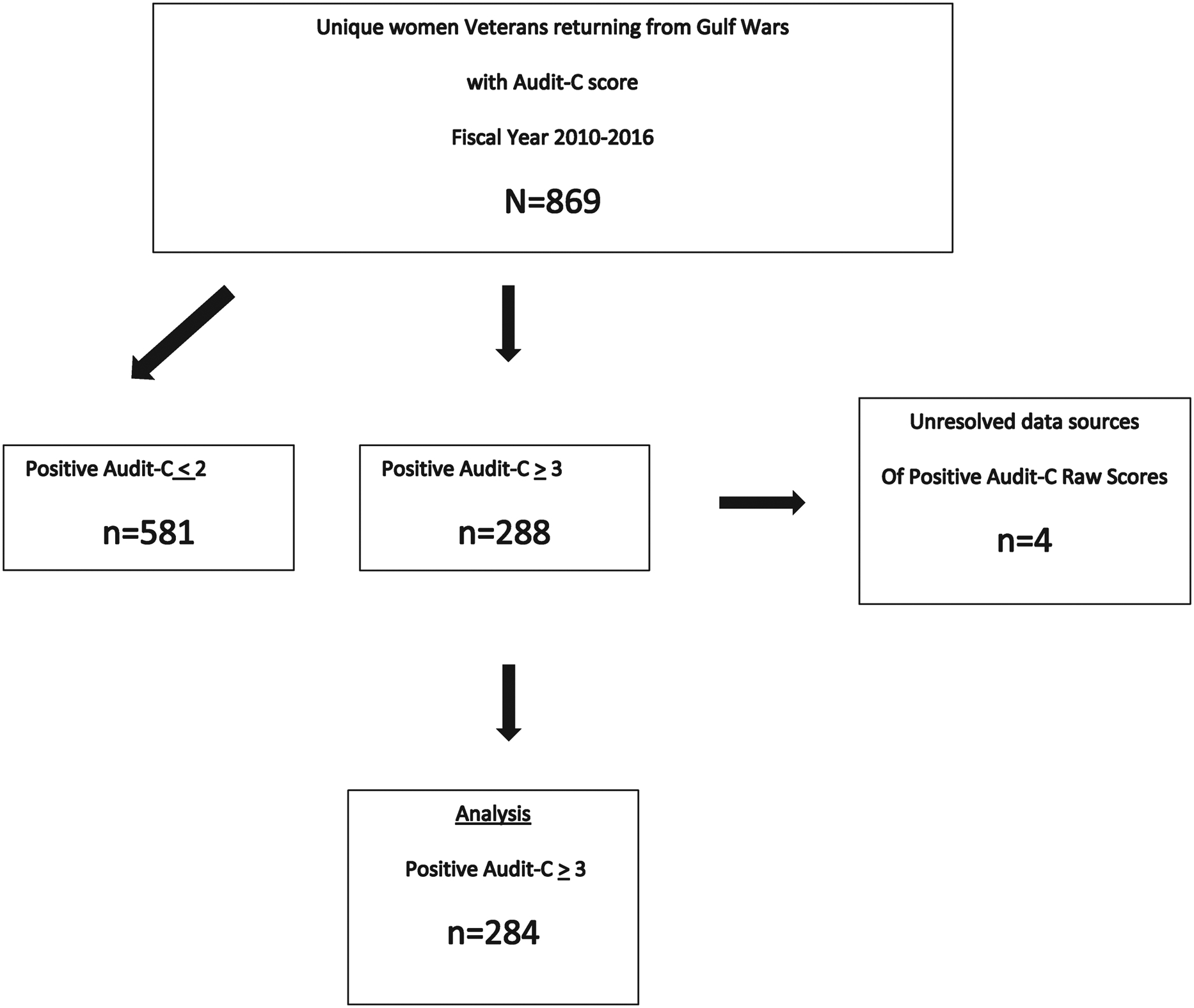

The study drew the sample using VA administrative data and electronic medical records (EMR) from the population of women veterans returning from recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan who received an inpatient or an outpatient service at VA Boston Healthcare System (VA BHS) during the study period (10/1/2010–10/31/2016) and who were screened for unhealthy alcohol use (N=869). The analytic sample was 284 (33%) unique women who screened positive for unhealthy alcohol use with an AUDIT-C score of ≥ 3 (Figure 1). Unique inpatient admissions account for up to 10% of all unique outpatients based on data from the hospital patient database (Fleming, personal communication). We collected data over a seven-year period to have sufficient sample size to examine multi-level predictors of BI. The study temporally tied receipt of BI to the positive screen.

Figure 1:

Consort diagram.

2.2. Data sources and variables

2.2.1. Administrative

We pulled data starting in 2010 from two administrative sources: a) Pyramid Analytics (PA) products and (b) a regional data warehouse (RDW). From the PA product, we accessed Inpatient and Outpatient Pyramid Analytics Products from the Veterans Health Administration Support Service Center (VSCC) web. From the RDW, we exported a total of 2,188 AUDIT-C screening visits of women veterans in the study period, including identifying information and the associated raw AUDIT-C score (ranging from 0 to 12). To study the most current positive AUDIT-C score (ranging from 3 to 12) while maximizing sample size, if a patient had multiple screening visits, we included the highest, most recent AUDIT-C score. The study exported resulting data to a data abstraction tool (Figure 1).

2.2.2. Chart review

All other data collected to characterize the sample of 284 women with positive screens for unhealthy alcohol use came from chart review from the administrative and clinical note sections of VA’s EMR, and study staff manually recorded in the data abstraction tool. We classified data elements from the EMR into categories according to Andersen’s model of health care utilization (Andersen & Davidson, 2007). First, predisposing factors included date of birth, gender, race/ethnicity, and marital status. Second, enabling factors included program and provider type, median household income as measured by patient zip code and later linked to the 2012–2016 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates (United States Census Bureau, 2016), percent service connection (representing at least partial VA health care coverage), and whether at risk of homelessness. Third, need factors included behavioral health diagnoses within thirty days of the index AUDIT-C (e.g., alcohol use disorder; AUD, and post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD]) if recorded as a disorder or a disorder in remission; and lifetime medical diagnoses if noted in the EMR and confirmed in the clinical note on the date of index AUDIT-C. The study abstracted other data elements from the EMR to support the quality of the data (e.g., the study checked the AUDIT-C raw score abstracted from the EMR against the raw score drawn from administrative data). The study abstracted receipt of BI as well as program and provider information on BI from the EMR; chart abstraction enabled linkage of the data on women veterans to the organizational-level variables. We strictly adhered to best practices for chart review methods (Gilbert et al., 1996; Vassar & Holzmann, 2013), except research assistants were not blinded to the study question due to academic training preferences.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Unhealthy alcohol use.

Since 2004, VA has screened veterans annually for unhealthy alcohol use with the AUDIT-C, a valid and reliable screening tool (Bradley et al., 2006; VA Office of Research and Development, 2008). The AUDIT-C is based on three consumption questions, each scored 0–4 points. It yields a total score ranging from 0–12 based on the sum of the participant’s responses. VA clinical guidelines for SUDs has an algorithm with a provider delivered action of BI at each risk level (Table 1). For women, the most balanced cutoff is an AUDIT-C cut-point of 2 with sensitivity and specificity of 0.84/0.85; however, as in other studies (Chavez et al., 2012), to reduce false positives we chose an AUDIT-C ≥3, which has adequate sensitivity and specificity (0.66/0.94; Bradley et al., 2003; Bradley et al., 2007). The VA’s chosen gender-neutral national cut-point of an AUDIT-C score=5 has a sensitivity and specificity for males of 0.68/0.90; while research has not yet reported the sensitivity and specificity of this cutoff for women veterans (Achtmeyer & Bradley, 2011). Unhealthy alcohol use, which the study defined by alcohol risk level, was analyzed by AUDIT-C category defined as low-risk (3–4), moderate-risk (5–7), and high-risk (8–12) alcohol use.

2.3.2. Brief intervention.

In this study, a completed BI performance measure signified the dependent binary variable and included one of two effective BI components as noted by the United States Preventive Services Task Force: brief advice or brief counseling (Final Recommendation Statement, 2018). We did not include feedback in this study as it is not part of the BI performance measure for primary care (Vahey, personal communication). Further, this study operationalized documented BI as provider-delivered BI, as supported by one of the following BI components in the Health Reports tab: (a) advice to drink within normal limits, (b) advice to abstain from alcohol use, or (c) brief alcohol counseling. Prior research on women veterans and unhealthy alcohol use has used brief counseling as a proxy for the delivery of the BI performance measure (Williams et al., 2014). These components were not mutually exclusive categories; more than one component of a brief intervention could be present, and in this study one of the named elements was sufficient to indicate BI was performed. The study team abstracted BI data systematically by searching for evidence of the advice component of the BI. If advice was marked complete within thirty days of the AUDIT-C, then the abstractor noted that the BI was completed. If the abstractor did not find evidence of provider-delivered advice following delivery of the index AUDIT-C, then a designated abstractor who was also clinically trained conducted a keyword search in the veteran’s record within the clinical notes tab one month prior to and one month following the index AUDIT-C seeking for evidence of the following abbreviations: “brief,” “adv,” “couns”, and/or “alc”. If an abstractor found one of these abbreviations in a clinic visit note, then the chart abstractor reviewed the note to ascertain whether this keyword was associated with the veteran’s positive AUDIT-C to ascertain presence or absence of BI.

2.3.3. Covariate measures.

Lifetime number of medical problems was a binary variable with 1 representing more than one medical diagnosis. Participants had up to 8 medical problems with an average of three medical diagnoses. About 14% of the sample had no medical problems. To validate our treatment of this variable as binary, we conducted a sensitivity analysis in which we recoded it into three categories (no medical problems, 1–3 medical problems, 4+ medical problems). Associations with BI (described in the Results section) were unchanged, and so we retained our binary coding of this variable for all subsequent analyses.

Provider and program type were independent variables of key interest. The screening visits were delivered by more than 100 unique providers classified as physician non-psychiatrists, nurses, medical support assistants/health technicians, psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and other professionals. Nurses accounted for delivering the largest share of the visits (53%) while mental health trained providers delivered 37% of visits. There were approximately 30 different programs that we used to create two program variables: a) Program Type A: primary care = 1; mental health = 0 and b) Program Type B: women’s health = 1; mixed-gender = 0. We created the variables by combining provider and program type (“provider-in-program”), and we included only one such variable in a model.

2.3.4. Missing data

Data were rarely missing. If data on BI were missing, study staff assumed the provider did not deliver the BI. Additionally, in the case when provider type or provider gender were missing from the EMR, clinicians on the research team knowledgeable of these factors named them.

2.4. Analyses

Researchers computed descriptive and bivariate statistics by drinking risk level for patient-level and organizational characteristics (Table 2 and 3). Using a correlation matrix, we flagged any independent variables with more than a moderate association (.6 or above) as potentially redundant; however, we determined inclusion using multiple considerations. The study included variables in the model for theoretical reasons, like AUD, which is a proxy for prior alcohol treatment, a need variable (Andersen & Davidson, 2007). The study retained other variables if they study staff identified them as important predictors and/or had clinical justification as a need variable, such as opioid use disorder (OUD).

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study sample by drinking risk level (n=284).

| AUDIT-C Risk level - % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Moderate | High | Total | |

| Age group | ||||

| 21 −24 | 9 | 13 | 8 | 10 |

| 25–29 | 39 | 31 | 27 | 35 |

| 30–38 | 31 | 39 | 49 | 36 |

| 39–54 | 17 | 15 | 16 | 16 |

| 55+ | 4 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 64 | 67 | 73 | 67 |

| African American | 13 | 20 | 11 | 15 |

| Hispanic | 20 | 8 | 3 | 31 |

| Asian | 7 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| American Indian/Native Hawaiian/P.I. | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Declined to Answer/Unknown/Missing | 4 | 2 | 7 | 4 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married/In Partnership | 26 | 26 | 18 | 25 |

| Never Married/Single | 46 | 53 | 41 | 47 |

| Divorced/Separated/Unknown | 28 | 21 | 41 | 28 |

| At-risk for homelessness** | ||||

| Yes | 6 | 17 | 24 | 12 |

| Military branch | ||||

| Army | 66 | 74 | 76 | 70 |

| Air Force | 9 | 11 | 6 | 9 |

| Marine Corps | 13 | 4 | 8 | 10 |

| Navy | 12 | 11 | 10 | 12 |

| Up to 50% Service connection** | 48 | 53 | 73 | 54 |

| Within five years of date of Separation* | 63 | 53 | 45 | 57 |

| Health coverage: at least partial* | 64 | 53 | 55 | 58 |

| Medical health problems: more than 1 | 67 | 68 | 55 | 65 |

| Psychiatric problems/diagnoses | ||||

| Alcohol use disorder (AUD)** | 12 | 38 | 22 | 30 |

| Opioid use disorder (OUD)* | 2 | 4 | 10 | 4 |

| Tobacco use | 38 | 43 | 53 | 42 |

| Any substance use disorder (SUD)** | 43 | 64 | 86 | 56 |

| Any depressive disorder* | 34 | 50 | 53 | 41 |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)** | 34 | 46 | 76 | 44 |

| Military sexual trauma (MST) | 36 | 43 | 55 | 41 |

p≤ .05.

p≤ .01.

p≤ .001

Table 3.

Characteristics of visits by drinking risk level (n=284).

| AUDIT-C Risk level - % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Moderate | High | Total | |

| Provider Type* | ||||

| Physician, Non-Psychiatrist | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Nurse | 61 | 47 | 35 | 53 |

| Medical Support Assistant/Health Tech | 11 | 4 | 8 | 9 |

| Psychiatrist | 4 | 13 | 12 | 8 |

| Psychologist | 16 | 19 | 31 | 19 |

| Social Worker | 6 | 15 | 14 | 10 |

| Other Professional | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Primary Provider Training** | ||||

| Medical | 74 | 53 | 43 | 63 |

| MH | 26 | 47 | 57 | 37 |

| Female Provider | 85 | 89 | 86 | 86 |

| Program Type** | ||||

| Primary Care | 69 | 43 | 24 | 55 |

| Outpatient SUD Treatment | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Outpatient MH | 14 | 29 | 29 | 20 |

| Residential SUD Treatment | 1 | 4 | 29 | 7 |

| Inpatient Medically Managed Detoxification | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| Inpatient MH Treatment | 1 | 6 | 10 | 4 |

| OEF-OIF-OND Case Management | 9 | 14 | 2 | 9 |

| Center for Returning Veterans | 5 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Provider-in-Program - Primary Care** | ||||

| Nurse Visits in Primary Care | 57 | 39 | 20 | 46 |

| Nurse Visits in MH Programs | 4 | 8 | 14 | 7 |

| Other Types of Provider Visits Primary Care | 12 | 4 | 4 | 9 |

| Other Types of Provider Visits in MH | 26 | 49 | 61 | 38 |

| Women’s Health Program | ||||

| Provider-in-Program - Women’s Health** | ||||

| Nurse Visits in WH Programs | 47 | 36 | 14 | 39 |

| Nurse Visits not in WH Programs | 14 | 11 | 20 | 14 |

| Other Types of Provider Visits in WH | 14 | 24 | 45 | 22 |

| Other Types of Provider Visits not in WH | 25 | 29 | 20 | 25 |

| Outpatient Program** | 98 | 90 | 61 | 90 |

| Location of Program (VA medical center - community based outpatient center)** | 82 | 90 | 84 | 84 |

p≤ .05.

p≤ .01.

p≤ .001

Researchers estimated an unadjusted logistic regression model to predict receipt of BI, with a three-category AUDIT-C variable only and then adjusted it in blocks to answer research questions. The first block included the AUDIT-C raw score, provider gender, and the location where the women veterans were screened. Next, we added additional blocks sequentially according to theory (e.g., predisposing factors, enabling factors, and need factors; Andersen & Davidson, 2007). The year that the patient was screened was not significant, and we dropped it from the model to conserve degrees of freedom. For all combinations of independent variables in the models, the variance inflation factor (VIF) scores were < 4, below the standard cut-off of 10 for high correlation among explanatory variables (Wooldridge, 2009), reducing concerns about multicollinearity. We performed all analyses in Stata 11 and Stata 15 (Stata, 2017; StataCorp, 2009). All tables report statistical significance with an alpha level of .05.

3. Results

The women veterans in this study population had a 33% prevalence of unhealthy alcohol use (AUDIT-C ≥3).

3.1. Patient and program characteristics

Table 2 summarizes demographic and clinical characteristics of the 284 women veterans who screened positive for unhealthy alcohol use on the AUDIT-C based on the gender-specific cut-point of 3 by drinking risk level. Of note, 89% of the women veterans were of reproductive age (e.g. 45 years or younger; Center for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2018). Participants had an average of two mental health or substance use diagnoses. Almost 30% of the sample had a diagnosis of AUD, and more than 50% had a type of SUD. The sample also had high rates of PTSD (44%) and depression (42%). Risk level was associated with homelessness status, percent service connection, date of separation, as well as all substance use and psychiatric diagnoses.

Table 3 presents organizational-level characteristics of the sample by AUDIT-C risk level. Of note, a medically trained provider in primary care programs screened more than half of women veterans (63%), including 53% who were screened by nurses; providers with mental health training in primary care as well as substance use or case management programs screened the remaining women veterans. About 61% of the screening visits were completed in women’s health programs (e.g. women’s primary care, outpatient women’s trauma and recovery treatment programs, and residential programs). About 11% of screening visits were completed in residential substance use disorder (SUD) treatment, medical detoxification, and inpatient or residential mental health (MH) programs. In total, 90% were screened in visits that occurred in outpatient programs and of these about 55% were screened in primary care. Provider and program type were both associated with level of drinking risk.

Among the positive screen sample, overall 60% received BI. Of those who received BI, 34% received advice to drink within normal limits, 21% received advice to abstain, and 5% received brief alcohol counseling. Those with moderate- and high-risk alcohol use received a BI at twice the rate of those with low-risk alcohol use (Figure 2). The rate of BI varied by setting. Of those who were screened in outpatient mental health settings, SUD or Center for Returning Veteran settings, 85% received a BI; 94% received a BI when screened on inpatient mental health-related units, and 41% of women veterans received a BI when screened in primary care settings.

Figure 2:

Brief intervention: Receipt by women veterans’ alcohol risk level.

Note: Risk Levels

Lower-risk (AUDIT-C=3–4)

Moderate-Risk (AUDIT-C=5–7)

High-Risk (AUDIT-C=8–12)

Error bars depict 95% confidence intervals

3.2. Predictors of brief intervention

In this next section, we present answers to research questions 2–5 (Table 4). Women veterans who screened positive for moderate as well as severe-risk (AUDIT-C=5–7; =8–12) were more likely to receive a BI than those who screened at low-risk (AUDIT-C=3–4; OR: 10.68, CI 95% (4.40–35.90), p≤.001; OR: 13.03, CI 95% (3.16–53.71), p≤.001). In terms of need and enabling factors, having more than one medical problem did not predict BI. Patients who saw non-nurse providers in mental health programs were significantly more likely to receive BI, (OR: 5.73, CI 95% (2.38–13.82), p≤.001). Women veterans screened in women’s health programs by nurses were no more likely to receive BI than those screened in mixed-gender programs. However, those screened in visits with other types of providers in mixed-gender programs had higher odds of receiving a BI than those screened in visits with nurses in women’s health programs (OR: 2.76, CI 95% (1.21–6.28), p<.05).

Table 4.

Predictors of brief intervention.

| Model 1 3 -category AUDIT-C (n=284) | Model 2 Gender-Specific Program (n=284) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI |

| Provider-in-Program - Primary Care (PC) (Ref = Nurses-in-primary-care) | ||||

| Nurses-in-MH | 1.71 | 0.43–6.80 | ||

| Other-types-of-providers in Primary Care | 0.56 | 0.18–1.71 | ||

| Other-types-of-providers-in-MH | 5.73*** | 2.38–13.82 | ||

| Provider-In-Program Gender-Specific Program (Ref = Nurses-in-Women’s-Health) | ||||

| Nurses-not-in-Women′s Health- | 1.4 | 0.48–4.05 | ||

| Other-Types-of-Providers-in-Women′s Health | 2.05 | 0.78–5.40 | ||

| Other-Types-of-Providers-not-in-Women′s Health | 2.76* | 1.21–6.28 | ||

| 3-Category Audit-C Severity (Ref = 3–4 Mild) | ||||

| 5–7 Moderate | 10.68*** | 4.40–25.90 | 10.41*** | 4.43–24.43 |

| 8–12 Severe | 13.03*** | 3.16–53.71 | 13.52*** | 3.28–54.01 |

| Medical Problems/Diagnoses | ||||

| Yes | 1.02 | 0.86–1.21 | 1.03 | 0.86–1.21 |

| SUD & MH Problems/Diagnoses | ||||

| Alcohol Use disorder AUD | 1.9 | 0.71–5.04 | 2.33 | 0.90–6.04 |

| OUD | 1.64 | 0.14–18.79 | 2.66 | 0.24–30.16 |

| Tobacco Use | 1.26 | 0.62–2.59 | 0.9 | 0.46–1.74 |

| PTSD | 1.29 | 0.64–2.61 | 1.59 | 0.81–3.14 |

| Age Group (Ref 21–24) | ||||

| 25–29 | 1.32 | 0.38–4.5 | 1.08 | 0.34–3.49 |

| 30–38 | 0.61 | 0.17–2.27 | 0.56 | 0.16–1.97 |

| 39–65 | 0.92 | 0.23–3.62 | 0.74 | 0.20–2.76 |

| Race/Ethnicity (Ref=White) | ||||

| Black | 1.25 | 0.45–3.49 | 1.52 | 0.56–4.18 |

| Hispanic | 0.43 | 0.16–1.15 | 0.56 | 0.22–1.41 |

| Asian Am Indian/Nat Hawaiian/Pac Islander | 0.58 | 0.14–2.39 | 0.78 | 0.20–3.01 |

| Marital Status (Ref = Married) | ||||

| Never Married/Single | 0.63 | 0.28–1.41 | 0.63 | 0.29–1.38 |

| Divorced/Separated/Unknown | 0.54 | 0.22–1.34 | 0.6 | 0.25–1.49 |

| Military Branch (Ref=Army) | ||||

| Air Force | 0.48 | 0.15–1.52 | 0.48 | 0.15–1.52 |

| Marine Corps | 1.26 | 0.43–3.69 | 1.26 | 0.43–3.69 |

| Navy | 1.58 | 0.55–4.31 | 1.58 | 0.55–4.31 |

| Household Median Income | ||||

| Above Mean | 1 | 1.00–1.00 | 1 | 1.00–1.00 |

| Health Coverage (Ref=No) | ||||

| Full or Partial | 0.67 | 0.32–1.39 | 0.56 | 0.28–1.14 |

| At-Risk Homeless (Ref=Not At-Risk) | ||||

| Yes | 0.97 | 0.29–3.18 | 1.22 | 0.38–3.93 |

| N | 284 | |||

Note. Ref = Reference Group

p≤ .05.

p≤ .01.

p≤ .001

4. Discussion

In this sample of women veterans who accessed VA inpatient and/or outpatient care, we found BI was delivered to 90% of women veterans returning from recent wars with moderate-to severe-risk drinking (AUDIT-C≥5), but to only 60% if the figure also includes women veterans with low-risk drinking (AUDIT-C ≥3). Of the 57% of women veterans in the sample who screened positive for low-risk alcohol use (AUDIT-C=3–4), 66% did not receive BI, indicating a lost opportunity to improve health and well-being for this younger cohort of women veterans. This service delivery gap for women veterans scoring a 3–4 on the AUDIT-C is similar to that of women veterans missed in a national study using data from 2006–2010 (Williams et al., 2017); both indicate that two thirds of women who screened positive at 3–4 did not receive the intervention.

This study adds to knowledge of person- and system-level predictors of BI by drinking risk level for a young cohort of women veterans from recent wars who accessed the VA. Even though there is mixed evidence for telescoping (e.g., a more rapid progression from alcohol use to dependency among women than men; Keyes et al., 1989; Piazza et al., 1989), a more complicated association remains between alcohol and health that, in part, depends on health condition and rate/frequency of drinking (Chang et al., 2011). While primary care and women’s health programs within the VA have supported the integration of medical and behavioral health care and have implemented policies to address female-specific health issues (Bastian et al., 2014; Caregivers and Veterans Omnibus Health Services Act of 2010, 2010), this study indicates that, on average, nurses in primary care visits were less likely to deliver BI to women veterans than providers with behavioral health training in mental health programs. Nurses in women’s health programs were no more likely to implement BI than other types of providers in mixed-gender programs. Future studies should investigate programs and providers to determine and address the quality of BI that a provider implements for women veterans. Future research should determine what factors contribute to receipt of BI being no more likely for women veterans with more medical problems than for those with fewer medical problems. Additionally, longitudinal studies could demonstrate if women veterans with low-risk alcohol use who receive BI have better health outcomes than those who do not receive BI (Danan et al., 2017).

The 33% prevalence of unhealthy alcohol use in this study’s women veteran population is at the high end of the range that is seen in other studies that reported prevalence in women veterans in ambulatory only settings at 27%, 25% and 24%, respectively (Hoggatt, Williams, Der-Martirosian, Yano, Washington, 2015; Hoggatt et al., 2018; Chavez et al., 2012). However, the prevalence in this study is within the range reported in a systematic review which that from 4%–37% (Hoggatt, Jamison, Lehavot, Cucciare, Timko, Simpson, 2015). The high prevalence of unhealthy alcohol use in this study may reflect the sample’s limitation to include women veterans who had inpatient care. The finding could also be related to changing demographic composition (Chavez et al., 2012; Runnals et al., 2014). Women veterans in this study had similar rates of PTSD and higher rates of AUD and depression than those reported in an outpatient-only sample (Grossbard et al., 2013). Broadly, women veterans in this study had higher frequencies of dual-diagnoses than women veterans in general (Hoggatt, Williams, Der-Martirosian, Yano, Washington, 2015).

Almost 90% of women veterans in this study sample were of reproductive age. Recent research spanning a five-year period indicates that among women veterans of reproductive age from the Gulf War era who accessed the VA’s health care system, 7% had at least one diagnostic code for pregnancy (intended or unintended) in their medical record (Mattocks et al., 2010). The CDC (2018) recommends that all women of reproductive age receive screening and BI for any alcohol use, not only women with moderate-to severe-risk alcohol use. Providing BI to women during pregnancy is associated with reduced risk of alcohol-exposed pregnancy (Floyd et al., 2007). Rates from this study indicate that 57% of women veterans who screen positive at AUDIT-C ≥3 have an AUDIT-C score of 3 or 4, a proportion five percentage points lower than observed in a general sample of women veterans (Grossbard et al., 2013). Since providers are not delivering BI to at least 66% of these women, this lost opportunity to support the well-being of women veterans of reproductive age runs counter to the CDC’s recommendation and may undermine its impact on maternal-child health. Further, this gap in care highlights the potential and concerning impact on those women veterans of reproductive age who screened positive at AUDIT C 3–4 and did not receive a BI.

Utilizing the VA’s robust EMR and a chart review method enabled us to carry out the first examination of organizational predictors of BI for women veterans returning from recent wars who screened positive at a gender-sensitive cut-point. Because the women veteran population is rapidly increasing and the VA has traditionally been oriented toward men’s health care, this study in one VA locality, provides data that inform the VA nationally. Further, the national VA health care system is similar in structure and goals to an accountable care organization; findings in this study may have utility for the implementation of BI for women veterans in the private sector (Nemeth, 2015).

4.4. Limitations

While this study has methodological strengths, including comprehensive chart review, there are several limitations. The study did not validate some variables in this study (e.g., the severity of medical problems tabulated was not assessed like the Charlson Comorbidity Index; Charlson et al., 1987). From our data, we could not determine the number of drinks consumed, and for some women veterans scoring AUDIT-C = 3, the number could have been within normal limits. We may have underestimate the rate of BI, as some providers may have delivered a BI and not recorded it in the EMR (Berger et al., 2018). Alternatively, there was some potential for false positive screens; and therefore we may have overestimated the BI service delivery gap (66%) for women veterans with low-risk alcohol. The prevalence of unhealthy alcohol use and the rates of BI in this study may not generalize to a cohort of women veterans who present without inpatient admissions yet the prevalence and BI rates may generalize to a younger cohort of women veterans who access outpatient or inpatient settings, perhaps reflecting this group’s high rates of unhealthy alcohol use, as well as health and mental health conditions (Cheng et al., 2016; Grucza et al., 2018; Harris et al., 2010; Runnals et al., 2014). The rate of BI in this study examining data from one VA medical center may not generalize nationally; however, the BI service delivery gap for women veterans with low-risk alcohol in this study was within one percentage point of the BI rate reported in a national study (Williams et al., 2017). Further, while study predictors of BI cannot be generalized to current VA practice due to the age of the data, predictors may be useful to improve implementation efforts.

5. Conclusion

Missed opportunities to screen and respond to women veterans with unhealthy alcohol use underscore the importance of accurate and equitable implementation of BI using a VA guideline-adherent alcohol screening score for women veterans (Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defence, 2009, 2015). Without guideline-adherent follow-up care for women veterans who screen positive for unhealthy alcohol use, these women can experience adverse health consequences, including suicide risk (Bohnert et al., 2017; Ilgen, Harris, Moos, Tiet, 2007; Ilgen, Jain, Lucas, Moos, 2007). This study contributes to knowledge through reporting rates and predictors of BI for women veterans with application to potentially inform BI implementation in the VA and the community. Research should study context-specific multi-level facilitators and barriers to uptake of best practices for women veterans who screen positive for unhealthy alcohol use in VA primary care and gender-specific programs. Capitalizing on the organizational-level factors that contribute to the facilitation of BI implementation may support better allocation of resources and identify whether training and/or technical assistance regarding unhealthy alcohol use and addiction is warranted within different settings (e.g., primary care and specialty care; Bauer et al., 2019; Kirchner et al., 2014).

The VA could reduce the gap in service delivery of BI to women veterans who screen positive for unhealthy alcohol. One way to do so is to tailor the binge-drinking question from a threshold of 6 to that of 4 or more drinks on a given occasion (Hoggatt et al., 2018). Alternatively, the VA could train providers to deliver BI to women veterans at a threshold of 3 and incentivize them through modifying the alerts and performance measures for women veterans to use that cut-point. Maintaining the AUDIT-C cut-point at 5 for women veterans as the status quo may no longer be efficient. Women make up approximately 12% (149,919) of all veterans returning from recent wars and access the VA health care system (Department of Veterans Affairs, 2015). Studies suggest that about 25% (37,480; Hoggatt, Williams, Der-Martirosian, Yano, Washington, 2015) of these women veterans would be likely to screen positive for alcohol use at an AUDIT-C ≥3. Even a conservative interpretation of these numbers suggests that, on an annual basis, thousands of women veterans screen positive at an AUDIT-C =3–4 and do not receive BI (Williams et al., 2017; Grossbard et al., 2013). Women veterans are a rapidly increasing population and a VA priority; optimizing BI implementation for this younger cohort of women veterans in primary care and gender-specific programs will likely reduce the burden of disease for women veterans and is timely.

Highlights.

We examine rates and predictors of brief interventions (BI) for women Veterans

Women Veterans with lower-risk alcohol use are less likely to receiveBI

BI is more probable from mental health program clinicians than primary care nurses

BI is more likely from women Veteran program clinicians than mixed-gender program nurses

Women Veterans with more health problems are no more likely to receive BI

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Grant Ritter, PhD, Beth Mohr, MS, Lee Panas, MS and Michelle Gibson, RN, as well as the social work team: Leidy McIntosh, MSW, Samantha Strachoff, MSW, Max Wiener, MSW, Ron Desnoyers, MSW Hannah Simkins, MSW, Alexandra Kruk, MSW and Jotham Busfield, MSW for their generous contributions to this study.

Role of Funding Source This research was primarily supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) of the National Institutes of Health [T32AA007567] and work supported by the Office of Academic Affiliations, United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) with resources and the use of facilities at the Veterans Health Administration Boston Healthcare System. The VA Boston Healthcare System of the United States Department of Veterans Affairs provided access to the data set. Additional support was provided by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) of the National Institutes of Health [T32MH018261]. The funders were not involved in the research methods or writing. The opinions or assertions herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, the United States Government or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data Statement Due to the sensitive nature of the research questions asked and respondent population in this study, the data remains confidential and will not be shared.

References

- Achtmeyer C, & Bradley KA (2011). Using AUDIT_C Alcohol Screening Data in VA Research: Interpretation, Strengths, Limitations & Sources. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/video_archive.cfmSessionID=378

- Ait-Daoud N, Blevins D, Khanna S, Sharma S, & Holstege CP (2017). Women and addiction. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 40(2), 285–297. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2017.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen RM, & Davidson PL (2007). Improving access to care in America. Changing the US health care system: key issues in health services policy and management. 3a. edición. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros J, Gonzalez-Pinto A, Querejeta I, & Arino J (2004). Brief interventions for hazardous drinkers delivered in primary care are equally effective in men and women. Addiction, 99(1), 103–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastian LA, Trentalange M, Murphy TE, Brandt C, Bean-Mayberry B, Maisel NC, … Haskell S (2014). Association between women veterans’ experiences with VA outpatient health care and designation as a women’s health provider in primary care clinics. Womens Health Issues, 24(6), 605–612. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2014.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer MS, Miller CJ, Kim B, Lew R, Stolzmann K, Sullivan J, … Connolly S (2019). Effectiveness of implementing a collaborative chronic care model for clinician teams on patient outcomes and health status in mental health: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Network Open, 2(3), e190230–e190230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger D, Lapham GT, Shortreed SM, Hawkins EJ, Rubinsky AD, Williams EC, . . Bradley KA (2018). Increased Rates of Documented Alcohol Counseling in Primary Care: More Counseling or Just More Documentation? Journal of General Internal Medicine, 33(3), 268–274. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4163-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert KM, Ilgen MA, Louzon S, McCarthy JF, & Katz IR (2017). Substance use disorders and the risk of suicide mortality among men and women in the US Veterans Health Administration. Addiction, 112(7), 1193–1201. doi: 10.1111/add.13774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley KA, Bush KR, Epler AJ, Dobie DJ, Davis TM, Sporleder JL, … Kivlahan DR (2003). Two brief alcohol-screening tests From the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): validation in a female Veterans Affairs patient population. Archives of Internal Medicine, 163(7), 821–829. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.7.821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley KA, DeBenedetti AF, Volk RJ, Williams EC, Frank D, & Kivlahan DR (2007). AUDIT-C as a brief screen for alcohol misuse in primary care. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 31(7), 1208–1217. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00403.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley KA, Williams EC, Achtmeyer CE, Volpp B, Collins BJ, & Kivlahan DR (2006). Implementation of evidence-based alcohol screening in the Veterans Health Administration. American Journal of Managed Care, 12(10), 597–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun PS, Elter JR, Jones ER Jr., Kudler H, & Straits-Troster K (2008). Hazardous alcohol use and receipt of risk-reduction counseling among U.S. veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69(11), 1686–1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caregivers and Veterans Omnibus Health Services Act of 2010, U. S. C (2010). Washington DC: United States Government Printing Office [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). CHOICES: Preventing Alcohol Exposed Prenancies. 2018, from https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/fasd/choices-importance-preventing-alcohol-exposed-pregnancies.html [Google Scholar]

- Chang G, Fisher ND, Hornstein MD, Jones JA, Hauke SH, Niamkey N, … Orav EJ (2011). Brief intervention for women with risky drinking and medical diagnoses: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 41(2), 105–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, & MacKenzie CR (1987). A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. Journal of Chronic Diseases, 40(5), 373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez LJ, Williams EC, Lapham G, & Bradley KA (2012). Association between alcohol screening scores and alcohol-related risks among female veterans affairs patients. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 73(3), 391–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng HG, Cantave MD, & Anthony JC (2016). Taking the first full drink: Epidemiological evidence on male-female differences in the United States. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 40(4), 816–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cucciare MA, Simpson T, Hoggatt KJ, Gifford E, & Timko C (2013). Substance use among women veterans: epidemiology to evidence-based treatment. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 32(2), 119–139. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2013.795465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danan ER, Krebs EE, Ensrud K, Koeller E, MacDonald R, Velasquez T, … Wilt TJ (2017). An Evidence Map of the Women Veterans’ Health Research Literature (2008–2015). Journal of General Internal Medicine, 32(12), 1359–1376. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4152-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Veterans Affairs. (2015). Analysis of VA Health Care Utilization among Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF), Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), and Operation New Dawn (OND) Veterans (Department of Veterans Affairs, Trans.). In Epidemiology Program, Post Deployment Health Group, Office of Public Health & Veterans Health Administration; (). [Google Scholar]

- Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. (2009). Substance use disorders: VA/DoD clinical practice guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. (2015). Substance use disorders: VA/DoD clinical practice guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- Final Recommendation Statement. (2018). Unhealthy Alcohol Use in Adolescents and Adults; Screening and Behavioral Counseling,. Retrieved May 5, 2020, from https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/unhealthy-alcohol-use-in-adolescents-and-adults-screening-and-behavioral-counseling-interventions

- Floyd RL, Sobell M, Velasquez MM, Ingersoll K, Nettleman M, Sobell L, … Nagaraja J (2007). Preventing Alcohol-Exposed Pregnancies: A Randomized Controlled Trial. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 32(1), 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.08.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebara CF, Bhona FM, Ronzani TM, Lourenco LM, & Noto AR (2013). Brief intervention and decrease of alcohol consumption among women: a systematic review. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention and Policy, 8, 31. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-8-31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert EH, Lowenstein SR, Koziol-McLain J, Barta DC, & Steiner J (1996). Chart reviews in emergency medicine research: where are the methods? Annals of Emergency Medicine, 27(3), 305–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossbard JR, Hawkins EJ, Lapham GT, Williams EC, Rubinsky AD, Simpson TL, … Bradley KA (2013). Follow-up care for alcohol misuse among OEF/OIF veterans with and without alcohol use disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 45(5), 409–415. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grucza RA, Sher KJ, Kerr WC, Krauss MJ, Lui CK, McDowell YE, … Bierut LJ (2018). Trends in adult alcohol use and binge drinking in the early 21st-century United States: A meta-analysis of 6 National Survey Series. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 42(10), 1939–1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AH, Bradley KA, Bowe T, Henderson P, & Moos R (2010). Associations between AUDIT-C and mortality vary by age and sex. Population Health Management, 13(5), 263–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartz SM, Oehlert M, Horton A, Grucza RA, Fisher SL, Culverhouse RC, … Regnier P (2018). Daily drinking is associated with increased mortality. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 42(11), 2246–2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins EJ, Lapham GT, Kivlahan DR, & Bradley KA (2010). Recognition and management of alcohol misuse in OEF/OIF and other veterans in the VA: A cross-sectional study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 109(1–3), 147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.12.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoggatt KJ, Jamison AL, Lehavot K, Cucciare MA, Timko C, & Simpson TL (2015). Alcohol and drug misuse, abuse, and dependence in women veterans. Epidemiologic Reviews, 37, 23–37. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxu010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoggatt KJ, Simpson T, Schweizer CA, Drexler K, & Yano EM (2018). Identifying women veterans with unhealthy alcohol use using gender-tailored screening. American Journal on Addiction, 27(2), 97–100. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoggatt KJ, Williams EC, Der-Martirosian C, Yano EM, & Washington DL (2015). National prevalence and correlates of alcohol misuse in women veterans. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 52, 10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilgen MA, Harris AH, Moos RH, & Tiet QQ (2007). Predictors of a suicide attempt one year after entry into substance use disorder treatment. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 31(4), 635–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00348.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilgen MA, Jain A, Lucas E, & Moos RH (2007). Substance use-disorder treatment and a decline in attempted suicide during and after treatment. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 68(4), 503–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson P, Fitzgerald T, Salganlcoff A, Wood S, & Goldstein J (2014). Sex-specific medical research: why women’s health can’t wait. A report of the Mary Horrigan Connors Center for Women’s Health & Gender Biology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Brigham and Women’s Hospital. [Google Scholar]

- Jonas DE, Garbutt JC, Amick HR, Brown JM, Brownley KA, Council CL, … Harris RP (2012). Behavioral counseling after screening for alcohol misuse in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Annals of Internal Medicine, 157(9), 645–654. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-9-201211060-00544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaner EF, Beyer FR, Muirhead C, Campbell F, Pienaar ED, Bertholet N, … Burnand B (2018). Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Systematic Review, 2, Cd004148. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004148.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Martins SS, Blanco C, & Hasin DS (2010). Telescoping and gender differences in alcohol dependence: new evidence from two national surveys. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(8), 969–976. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09081161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner JE, Ritchie MJ, Pitcock JA, Parker LE, Curran GM, & Fortney JC (2014). Outcomes of a partnered facilitation strategy to implement primary care-mental health. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 29(4), 904–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattocks KM, Skanderson M, Goulet JL, Brandt C, Womack J, Krebs E, … Haskell S (2010). Pregnancy and mental health among women veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. Journal of Women’s Health, 19(12), 2159–2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaul ME, Roach D, Hasin DS, Weisner C, Chang G, & Sinha R (2019). Alcohol and women: A brief overview. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 43(5), 774–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mee-Lee D (2013). The ASAM Criteria: Chevy Chase, MD: American Society of Addiction Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2007). Helping patients who drink too much: A clinicians guide (Updated 2005 Edition). Washington DC: National Institutes of Health. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2016). Drinking levels defined: NIAAA; Bethesda, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Nemeth A (2015). How Veterans Affiars Healthcare Services are like accountable care organizations. The Hospitalist, 2015 (10). [Google Scholar]

- Piazza NJ, Vrbka JL, & Yeager RD (1989). Telescoping of alcoholism in women alcoholics. International Journal of Addiction, 24(1), 19–28. doi: 10.3109/10826088909047272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Gmel G, Sempos CT, & Trevisan M (2003). Alcohol-related morbidity and mortality. Alcohol Research and Health, 27(1), 39–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runnals JJ, Garovoy N, McCutcheon SJ, Robbins AT, Mann-Wrobel MC, & Elliott A (2014). Systematic review of women veterans’ mental health. Women’s Health Issues: Official Publication of the Jacobs Institute of Women’s Health, 24(5), 485–502. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2014.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Craig M, Wilkinson DA, & Davila R (1995). Empirically based guidelines for moderate drinking: 1-year results from three studies with problem drinkers. American Journal of Public Health, 85(6), 823–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scoccianti C, Lauby-Secretan B, Bello P-Y, Chajes V, & Romieu I (2014). Female Breast Cancer and Alcohol Consumption: A Review of the Literature. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 46(3, Supplement 1), S16–S25. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stata C (2017). Stata 15. Stata Cooperation, College Station, TX. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp L (2009). Stata 11: StataCorp LP College Station, TX. [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. (2016). American Commuity Survey. 2018, from https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk

- US Congress. (2008). Veterans’ Mental Health and Other Care Improvements Act of 2008. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; Retrieved from https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-110publ387/html/PLAW-110publ387.htm. [Google Scholar]

- VA Office of Research and Development. (2008). QUERI: Fact Sheet. Houston, Texas: Health Services Research and Development Services. [Google Scholar]

- Vassar M, & Holzmann M (2013). The retrospective chart review: important methodological considerations. Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professions, 10, 12. doi: 10.3352/jeehp.2013.10.12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams EC, Lapham GT, Rubinsky AD, Chavez LJ, Berger D, & Bradley KA (2017). Influence of a targeted performance measure for brief intervention on gender differences in receipt of brief intervention among patients with unhealthy alcohol use in the Veterans Health Administration. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 81, 11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams EC, Rubinsky AD, Chavez LJ, Lapham GT, Rittmueller SE, Achtmeyer CE, & Bradley KA (2014). An early evaluation of implementation of brief intervention for unhealthy alcohol use in the US Veterans Health Administration. Addiction, 109(9), 1472–1481. doi: 10.1111/add.12600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge JM (2009). Introductory econometrics: a modern approach. USA: South-Western Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang SM, Lee I-M, Manson JE, Cook NR, Willett WC, & Buring JE (2007). Alcohol consumption and breast cancer risk in the Women’s Health Study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 165(6), 667–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]