Introduction to Primary Biliary Cholangitis

Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), previously referred to as primary biliary cirrhosis, is a chronic autoimmune disease of the liver associated with damage to the bile ducts.1 The bile duct damage exhibits a specific pathology, with selective and progressive destruction of intrahepatic ducts. Untreated, PBC can lead to cholestasis and fibrosis of the liver, which triggers both intrahepatic and extrahepatic complications. Ultimately, PBC can result in end-stage liver disease, with potentially fatal results. The disease has a characteristic antimitochondrial antibody serologic signature.2,3

Many patients have a good quality of life. However, in a substantial proportion of patients, quality of life is reduced by symptoms that include pruritus, fatigue, joint aches, abdominal discomfort, and sicca complex (dry eyes/dry mouth).2,4-7 Low bone mass is not infrequently encountered in this patient population, not only because a majority of the patients are postmenopausal women, but also because the disease—particularly when advanced— can be associated with osteoporosis.8 Other symptoms associated with PBC include depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbance. Patients with PBC may coincidentally have other autoimmune conditions, such as primary Sjögren’s syndrome, thyroid disease, celiac disease, and systemic sclerosis.

As a cholestatic disease, PBC can affect lipid metabolism, which may result in xanthoma, xanthelasma, and high cholesterol levels. Compared with low-density lipo-protein cholesterol levels, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol is disproportionately elevated, and therefore the patient’s cardiovascular risk seems not to be increased.9

It is key for clinicians to engage with patients regarding symptoms and to offer help.

The first-line treatment of PBC consists of ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA). Guidelines recommend treatment with oral UDCA administered at 13 to 15 mg/kg per day, either as a single daily dose or in divided doses if tolerability is a concern.3 Second-line therapy consists of the farnesoid X receptor (FXR) agonist obeticholic acid, which is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of PBC in combination with UDCA in adults with an inadequate response to UDCA, or as monotherapy in adults who are unable to tolerate UDCA. Fibrates may be used in the second-line setting, based on their potential ability to decrease bile acid synthesis and bile acid–related hepatic inflammation.

Indexed through the National Library of Medicine (PubMed/Medline), PubMed Central (PMC), and EMBASE.

Disclaimer

Support of this monograph does not imply the supporter’s agreement with the views expressed herein. Every effort has been made to ensure that drug usage and other information are presented accurately; however, the ultimate responsibility rests with the prescribing physician. Gastro-Hep Communications, Inc., the supporter, and the participants shall not be held responsible for errors or for any consequences arising from the use of information contained herein. Readers are strongly urged to consult any relevant primary literature. No claims or endorsements are made for any drug or compound at present under clinical investigation.

©2021 Gastro-Hep Communications, Inc. 611 Broadway, Suite 605, New York, NY 10012. Printed in the USA. All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction, in whole or in part, in any form.

Insights Into the Disease State

PBC is diagnosed by primary care physicians and specialists. Patients tend to be female.10 The average age for disease onset is middle age, although the disease is diagnosed across all age groups.11 Younger patients (<50 years) are less likely to adequately respond to treatment with UDCA. Patients usually present because results from their serum liver tests are cholestatic, and that includes elevations in alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT).2 In most cases, patients are asymptomatic. In many patients, however, abnormal serum liver tests are accompanied by symptoms. These broad-ranging symptoms include fatigue, pruritus, bone aches, and dryness of the eyes and mouth (Figures 1 and 2).2,4-7 Most primary care physicians and community doctors are able to exclude other causes of these signs and symptoms, such as biliary tree obstruction or drug-related adverse events. Persistent serum liver tests showing cholestasis will lead to tests of antimitochondrial antibodies and immunoglobulins (Ig); elevated levels of IgM are often seen in patients with PBC (Table 1).2 Most patients receive a confirmed diagnosis of PBC without a liver biopsy.

Figure 1.

Relative impact of different types of symptoms in patients with primary biliary cholangitis. Scores for the different symptom domains and measures were compared in the UK‐PBC patient cohort. The symptom impact is shown. Adapted from Mells GF et al. Hepatology. 2013;58(1):273-283.4

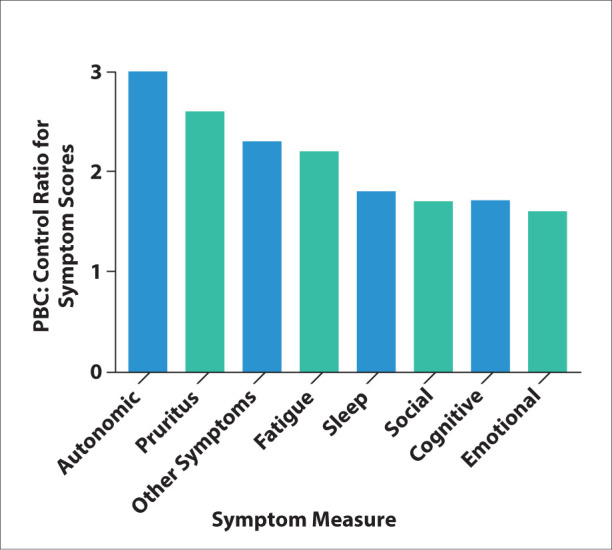

Figure 2.

Relative impact of different types of symptoms in patients with primary biliary cholangitis. Scores for the different symptom domains and measures were compared in the UK‐PBC patient cohort. The ratio of the symptom score is shown. Adapted from Mells GF et al. Hepatology. 2013;58(1):273-283.4

Table 1.

Broad Clinical Utility of Diagnostic and Prognostic Testing in Primary Biliary Cholangitis

| Result | Suspicion | Diagnosis | Prognosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum Liver Tests | ||||

| ALP | Increased | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| GGT | Increased | Yes | No | Yes |

| AST (AspAT) or ALT | Increased | Yes | No | Yes |

| Serum Autoantibody Profile | ||||

| Antimitochondrial antibodies (>1 in 40) | Positive | Yes | Yes | No |

| IgM | Increased | Yes | No | No |

| Anti-gp210 | Positive | No | Yes | Yes |

| Anti-sp100 | Positive | No | Yes | No |

| Anti-centromere | Positive | Yes | No | Yes |

| Liver Function | ||||

| Bilirubin | Increased | No | No | Yes |

| Albumin | Decreased | No | No | Yes |

| International normalized ratio | Increased | No | No | Yes |

| Platelets | Decreased | No | No | Yes |

| Imaging | ||||

| Ultrasound | NA | No | No | Yes |

| Transient elastography | NA | No | No | Yes |

| Histology | ||||

| Liver biopsy | Descriptive | Yes | Yes | Yes |

ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AspAT, aspartate aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GGT, gamma-glutamyltransferase; IgM, immunoglobulin M; NA, not applicable.

Adapted from Lleo A et al. Lancet. 2020;396(10266):1915-1926.2

After a diagnosis of PBC, most clinicians and patients are eager to learn the disease stage, the cause of the disease, and whether treatments are available to manage both the disease and any associated symptom burden. As a starting point, it is helpful to understand whether fibrosis is already present. Fortunately, most patients with PBC now present with early-stage disease, which can be effectively treated to prevent end-stage liver disease. It is necessary to stage the patient, usually according to clinical measures. Hematologic values, particularly the platelet count, should be measured. Ultrasound results and spleen size are also considered. In most regions throughout the world, it is possible to administer some type of noninvasive fibrosis testing, such as elastography or serum fibrosis markers. This information is analyzed in combination to gauge the clinical stage of the patient at presentation. A further analysis is performed a year after the patient begins treatment.

Symptom Management

Symptoms can be prevalent in PBC and are important to patients. Apart from pruritus, these symptoms are not specific to PBC, but nevertheless they should be addressed as part of the overall management plan. In very–late-stage disease, the overall symptom burden corresponds with disease severity. For the majority of patients, however, there is a disconnect between symptom severity and disease stage/ risk (other than for pruritus). The impact of symptoms is dependent on other non–liver-related factors, such as young age and social isolation. Inevitable confounders such as polypharmacy, sleep apnea, fibromyalgia, depression, and thyroid disease impact symptom burden. It is key for clinicians to engage with patients regarding symptoms and to offer help. Successful interventions for pruritus are available, but remain underused. Patient support groups and regular exercise can be helpful.

The TRACE algorithm offers practical ways to help patients with PBC manage fatigue.12 The components of this strategy are:

Treat the treatable: All symptoms that negatively affect the patient should be addressed.

Ameliorate the ameliorable: Depression is common in patients with PBC and can exacerbate fatigue.

Patients who develop depression should be offered appropriate therapy.

Cope: Strategies for coping with fatigue include pacing and planning activities throughout the day, as well as lifestyle adaptation.

Empathize: Symptoms should be managed with a clear approach tailored to each patient.

Acknowledgment

This article was written by a medical writer based on a clinical roundtable discussion.

References

- 1.Beuers U, Gershwin ME, Gish RG et al. Changing nomenclature for PBC: from ‘cirrhosis’ to ‘cholangitis’. Hepatology. 2015;62(5):1620–1622. doi: 10.1002/hep.28140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lleo A, Wang GQ, Gershwin ME, Hirschfield GM. Primary biliary cholangitis. Lancet. 2020;396(10266):1915–1926. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31607-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: the diagnosis and management of patients with primary biliary cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2017;67(1):145–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mells GF, Pells G, Newton JL et al. UK-PBC Consortium. Impact of primary biliary cirrhosis on perceived quality of life: the UK-PBC national study. Hepatology. 2013;58(1):273–283. doi: 10.1002/hep.26365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuo A, Kuo A, Bowlus CL. Management of symptom complexes in primary biliary cholangitis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2016;32(3):204–209. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldblatt J, Taylor PJ, Lipman T et al. The true impact of fatigue in primary biliary cirrhosis: a population study. Gastroenterology. 2002;122(5):1235–1241. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Selmi C, Gershwin ME, Lindor KD et al. USA PBC Epidemiology Group. Quality of life and everyday activities in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46(6):1836–1843. doi: 10.1002/hep.21953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parés A, Guañabens N. Primary biliary cholangitis and bone disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2018. pp. 34–35.pp. 63–70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Longo M, Crosignani A, Battezzati PM et al. Hyperlipidaemic state and cardiovascular risk in primary biliary cirrhosis. Gut. 2002;51(5 suppl 5):265–269. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.2.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gulamhusein AF, Hirschfield GM. Primary biliary cholangitis: pathogenesis and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17(5 suppl 5):93–110. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0226-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boonstra K, Beuers U, Ponsioen CY. Epidemiology of primary sclerosing cholangitis and primary biliary cirrhosis: a systematic review. J Hepatol. 2012;56(5):1181–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swain MG, Jones DEJ. Fatigue in chronic liver disease: new insights and therapeutic approaches. Liver Int. 2019;39(1):6–19. doi: 10.1111/liv.13919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]