Abstract

Biomaterials employed in the articular joint cavity, such as polycarbonate urethane (PCU) for meniscus replacement, lack of lubrication ability, leading to pain and tissue degradation. We present a nanostructured adhesive coating based on dopamine-modified hyaluronan (HADN) and poly-lysine (PLL), which can reestablish boundary lubrication between the cartilage and biomaterial. Lubrication restoration takes place without the need of exogenous lubricious molecules but through a novel strategy of recruitment of native lubricious molecules present in the surrounding milieu. The biomimetic adhesive coating PLL–HADN (78 nm thickness) shows a high adhesive strength (0.51 MPa) to PCU and a high synovial fluid responsiveness. The quartz crystal microbalance with dissipation monitoring shows the formation of a thick and softer layer when these coatings are brought in contact with the synovial fluid. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy and ConA-Alexa staining show clear signs of lubricious protein (PRG4) recruitment on the PLL–HADN surface. Effective recruitment of a lubricious protein by PLL–HADN caused it to dissipate only one-third of the frictional energy as compared to bare PCU when rubbed against the cartilage. Histology shows that this reduction makes the PLL–HADN highly chondroprotective, whereas PLL–HA coatings still show signs of cartilage wear. Shear forces in the range of 0.07–0.1 N were able to remove ∼80% of the PRG4 from the PCU–PLL–HA but only 27% from the PCU–PLL–HADN. Thus, in this study, we have shown that surface recruitment and strong adsorption of biomacromolecules from the surrounding milieu is an effective biomaterial lubrication strategy. This opens up new possibilities for lubrication system reconstruction for medical devices.

Keywords: nanostructured coating, biolubrication system, polymeric, biomacromolecules, glycoprotein

1. Introduction

Biomacromolecules play a vital role in sustaining physiological functions in living systems especially at sliding interfaces where lubricious films composed of adsorbed macromolecules like proteins, glycoproteins, lipids, and polysaccharides support a wide range of normal and shear stresses.1 Salivary lubricious film on oral surfaces,2 tear film on ocular surfaces,3 and lamina splendens on cartilage4 surfaces provide ultralow friction and wear protection. Hydration lubrication4,5 and sacrificial layer6,7 are the mechanisms proposed for this ultralow friction and wear protection, which is enabled by the lubricious film with the capability of water immobilization.4,8 Effective high lubrication is an essential feature of healthy articulating interfaces in the human body. The insertion of biomaterials and medical devices, e.g., silicone hydrogel as contact lenses, polycarbonate urethane (PCU) for meniscus replacement, and so forth, disturbs the highly evolved and natural lubrication system because the biomaterials are often not designed to provide lubrication. This may lead to symptoms like irritation, discomfort, pain, inflammation, and even tissue damage.9,10 PCU, for instance, is a popular biomaterial used for various types of meniscus replacements.11,12 When rubbing against the cartilage during the swing phase of the gait cycle, PCU gives rise to an order of magnitude higher coefficient of friction as compared to the native meniscus due to the inability of PCU to adsorb lubricating molecules from the synovial fluid.9 Surface modification in the form of texture and coatings are often employed to enhance lubrication of engineering systems. Inspired by the native lubrication system of cartilages where glycoproteins (PRG4)13 adsorbed on the surface play an important role in biological lubrication,4,14 bottle brush molecules15 and deblock copolymers16,17 either physisorbed15,16 or grafted17 to the surface has been shown to provide lubrication. These artificial and exogenous lubricants on the biomaterial surface replace the natural lubricant in the fluid phase, which brings their durability in question due to turnover of all biopolymers in vivo. Microtexturing, unfortunately, has been shown to increase friction under physiological conditions.18

In an actual joint cavity, the natural glycoprotein, e.g., PRG4 (lubricin), is present in ample amounts. Instead of using PRG4 as inspirations to produce exogenous molecules, why not utilize them to lubricate the biomaterial surface? In order to utilize PRG4, the biomaterial surface needs to be modified in such a way that the PRG4 are selectively recruited from the synovial fluid (SF) and adsorbed tenaciously on the biomaterial surface despite the presence of albumin, the most abundant and surface active protein.9,19 In the current study, we explore the possibility of such a surface modification in the form of a layer-by-layer (LbL) coating composed of hyaluronic acid (HA), a naturally available polysaccharide in SF, and dopamine-modified HA. HA is abundant in body fluid, shows a high affinity to PRG4, and yields high lubrication at the cartilage surface.20 With the dopamine modification of HA, we expect to impart an even higher adhesive nature toward the PRG4 molecules. Hitherto, surface recruitment of native biomacromolecules has been used to hydrate and lubricate biological tissues, e.g., oral mucosa2 and articular cartilage,21−23 but not used yet to provide lubrication to a biomaterial surface.

Thus, the aim of this study is to create an HA-based layer-by-layer nanostructured coating that tenaciously adheres to the biomaterial (PCU taken as an example) and recruits PRG4 from the SF to provide lubrication against the cartilage. The research question is whether HA is able to recruit PRG4 from SF and provide lubrication or dopamine modification of HA is necessary.

The kinetics of the LbL self-assembly of PLL–HA and PLL–HADN and their ability to recruit biomacromolecules from SF was monitored by a quartz crystal microbalance with dissipation monitoring (QCM-D) in real time. Types of adsorbed macromolecules were identified using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), ATR-FTIR spectroscopy, and fluorescent ConA staining. Adhesion strength of the coatings on PCU was analyzed by using a universal mechanical testing machine. The lubrication properties were evaluated at nanoscale with colloidal probe atom force microscopy (AFM). The cartilage–PCU lubrication system, the most typical part of the body, was then taken as the example to transfer the strategy to a more relative situation at macroscale. Besides lubrication, the wear of cartilage and biocompatibility of coatings were also evaluated in the study.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Synthesis of HADN and QCM-D Monitoring of PLL–HA and PLL–HADN LbL Formation

Dopamine modification of HA to obtain HADN was synthesized via carbodiimide chemistry using the protocol presented in detail in the Supporting Information. A QCM-D device model E4 (Q-sense, Gothenburg, Sweden) was used to monitor the layer-by-layer assembly of cationic poly-l-lysine (PLL) and anionic HA or HADN. The mass adsorption on the golden-coated crystal surface resulted in decrease in resonant frequency (Δf) and increase in dissipation (ΔD). The ratio between ΔD and Δf gives the information about structural softness. Before experiment, the gold-coated quartz crystals with 5 MHz were cleaned by a 10 min UV/ozone treatment to kill live microbes followed by immersion into a 3:1:1 mixture of ultrapure water, ammonium hydroxide, and H2O2 at 75 °C for 15 min and by drying with N2 and then another 10 min UV/ozone treatment. The QCM-D chamber was perfused with a buffer (pH = 7.4) using a peristaltic pump (Ismatec SA, Glattbrugg, Switzerland). When stable base lines for both frequency and dissipation at third harmonics were achieved, 0.5 mg/mL of PLL in a PBS solution (pH = 7.4) was introduced at 25 °C for 10 min with a flow rate of 50 μL/min, corresponding with a shear rate of 3 s–1, after which the chamber was perfused with 0.05% w/v of HA or HA–DN in PBS (pH = 7.4) for 10 min to form a second layer then followed by another 10 min of PLL to form a third layer until eight layers were formed. In between each step, the chamber was perfused with a buffer for 10 min until a stable frequency shift was observed to remove any unabsorbed molecules from the tubing or crystal chamber. Frequency and dissipation were measured in real time during perfusion. After eight-layer formation, some crystals were removed from the QCM-D to characterize the topography of the PLL–HA and PLL–HADN coatings. On the other hand, some crystals containing PLL–HA and PLL–HADN coatings were exposed to bovine synovial fluid for 10 min followed by 10 min of PBS rinsing to remove unabsorbed molecules from the crystal chamber. Crystals exposed to synovial fluid were then placed under the colloidal probe atomic force microscope2,24 to measure the nanoscale friction, and the detailed protocol is presented in the Supporting Information (SI).

2.2. Surface Characterization of PLL–HA and PLL–HADN Coatings

The surface roughness of the samples were measured by an atomic force microscope (Nanoscope IV Dimension 3100, USA) equipped with a dimension hybrid XYZ SPM scanner head (Veeco, New York, USA) on the surface of PLL–HA and PLL–HADN combination layers with a scan area of 5 × 5 μm2 in PBS on the crystal surface, a scanning frequency of 1 Hz, and a scan area of 20 × 20 μm2 on PCU disks in the air condition. Water contact angle measurements were also performed at room temperature using an OCA 15 plus goniometer (DataPhysics Instruments). The values were obtained by the sessile drop method. The used liquid was ultrapure water, the drop volume was 5 μL, and over three measurements were carried out for each sample. The chemical composition after exposure to SF was evaluated by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and the details are presented in the Supporting Information.

2.3. Adhesion Tests

The adhesion strength of PLL–HADN and PLL–HA coatings was investigated by a universal mechanical testing machine, according to the standard procedure ASTM D1002.25,26 Two PCU disks were covered with nanostructured coatings: one with four layers with an outmost layer of HA or HADN, another PCU (3 mm × 3 mm) with four layers with an outmost layer of PLL using the same procedure as for QCM-D. The two PCU disks were then put into contact and maintained at 40 °C for 18 h. The two disks were then pulled apart with a crosshead speed of 5 mm/min. The bonding strength can be determined from the maximum force–deformation curve. The average and standard deviations were obtained from three samples.

2.4. Concanavalin A (ConA) Staining of Glycoproteins27,28

ConA is widely used for staining glycoprotein and mucin. PLL–HA and PLL–HADN coatings after exposure to SF named PLL–HA–SF and PLL–HADN–SF, respectively, were fixed with paraformaldehyde (Sigma, CAS no.30525-89-4) at room temperature for 30 min. After rinsing with PBS, ConA-Alexa (ThermoFisher, catalog no. C11252) with a concentration of 1 μg/mL in PBS was added to the crystal surfaces and incubated at room temperature for 45 min. Fluorescent images were obtained using a confocal laser scanning microscope (TCS SP2, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with an argon ion laser at 488 nm. The crystal was always kept wet and in dark condition during staining and before microscopic examination. The green fluorescent intensity from each fluorescent micrograph was calculated using the Image J program.29,30

2.5. Lubrication Properties on an Ex Vivo Model

The PCU coated with PLL–HA and PLL–HADN immersed in synovial fluid was rubbed against the bovine cartilage in reciprocal sliding on a universal mechanical tester (UMT-3, CETR Inc., USA). The synovial fluid and osteochondral plug from the cartilage were collected according to the protocol described in detail in the Supporting Information. The cartilage and PLL–HA- and PLL–HADN-coated PCU disks were slid in the presence of SF at a normal load of 4 N (0.4 MPa)31 and a sliding speed of 4 mm/s. The sliding distance used was 10 mm per cycle, which gave a total distance of 1.44 m in 60 min of sliding. The PCU without any coating modification was the negative control. All the friction experiments were performed at 35 °C to mimic the physiological environment in the knee joint in a heated reservoir full of synovial fluid.

2.6. Change in the Cartilage and PCU Surface after Sliding

After sliding against coated and uncoated PCU surfaces, the cartilage surfaces were rinsed with PBS, and the roughness was measured with AFM in PBS with a scanning frequency of 1 Hz and a scan area of 50 × 50 μm2. Other cartilage plugs were fixed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 45 min at room temperature followed by rinsing with PBS. Then, cartilages were dehydrated, gold-coated, and observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The PCU after rubbing were fixed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature followed by rinsing with PBS. ConA with a concentration of 1 μg/mL in PBS was added to the PCU surfaces and incubated at room temperature for 45 min. Before taking fluorescent images by confocal laser scanning microscopy, each PCU was rinsed with PBS three times for 5 min. The PCU was always kept in wet and shaded conditions.

2.7. Cartilage Histology

Cartilage plugs after sliding were fixed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 12 h at 4 °C followed by thorough washing with PBS. The plugs were then decalcified in a 10% EDTA solution (pH > 8) for eight weeks followed by dehydration with graded alcohol and wax embedding. The embedded cartilages were sectioned to 5 μm thickness and stained with 1% Alcian blue 8GX (Sigma-Aldrich) in 3% acetic acid (pH = 2.5) for glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) and acetic mucins and 0.1% Fast Red in a 5% aluminum sulfate solution for the nucleus. The collagen was stained by 0.1% picrosirius red.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as means ± SD. Differences between groups by using two-tailed Student’s t analysis, accepting significance at p < 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Dopamine Modification of HA and Its Characterization

Hyaluronic acid–dopamine conjugate (HADN) with an 18.2% conjugation degree was prepared using the well-known carbodiimide chemistry with the active agent of N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC).26,32−34 A detailed description of the result is presented in the Supporting Information.

3.2. Preparation and Characterization of HA- and HADN-Based LbL Self-Assembled Coating onto the PCU Surface

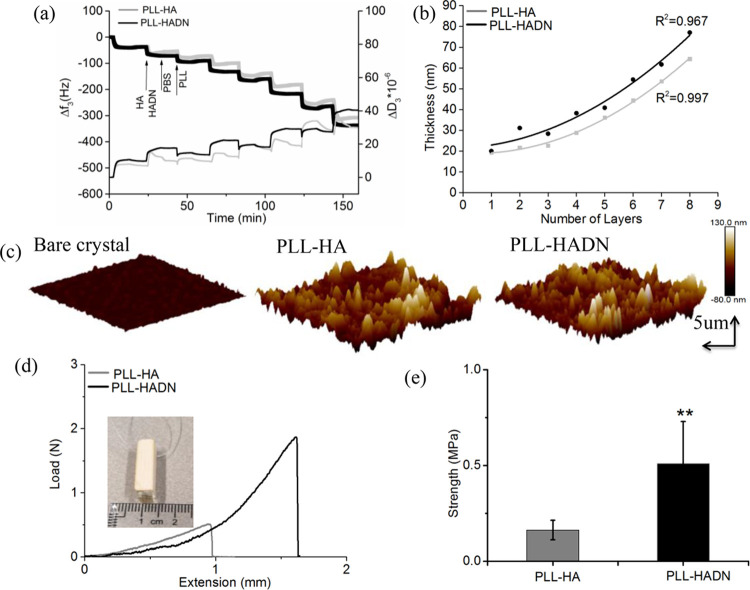

LbL self-assembly requires oppositely charged polyelectrolytes; with HA being an anionic polysaccharide, we used poly-l-lysine (PLL) as the cationic polyelectrolyte. The formation of PLL–HA and PLL–HADN LbL coating was investigated using QCM-D on Au-coated crystals, which is able to detect mass changes and viscoelastic features of a film in real time. PLL (0.5 mg/mL in 10 mM PBS) and HADN (0.5 mg/mL in 10 mM PBS) or PLL and HA (0.5 mg/mL in 10 mM PBS) were repeatedly purged through the QCM-D device one after the other at a flow rate of 50 μL/min for 10 min with intermediate rinsing with PBS. Figure 1a shows of frequency (Δf) and dissipation (ΔD) shifts with time dependence for the third harmonic. It could be seen that the frequency decreases with each PLL and HA or HADN injection. Increasing negative frequency shifts indicated at each step indicates the mass increasing on the crystal surface. PBS rinsing between each step to remove the free polyelectrolyte caused a small change of frequency, indicating that PLL and HADN or HA link to each other very well through electrostatic interactions under physiological pH and ionic strength. After eight-layer deposition (beginning with PLL and ending with HADN or HA), a frequency shift of −317 ± 23 and −306 ± 18 for PLL–HADN and PLL–HA, respectively, was observed.

Figure 1.

Layer-by-layer self-assembly of PLL–HA and PLL–HADN coatings, their thickness, topography, and adhesion strength to PCU. (a) Kinetics of PLL–HADN and PLL–HA coatings monitored using QCM-D with a normalized frequency (Δf) and dissipation (ΔD) shifts at the third overtone as a function of time. (b) Cumulative thickness evolution of PLL–HA and PLL–HADN as a function of deposition layers estimated by fitting a Voigt viscoelastic model to the QCM-D data. (c) AFM images of the bare QCM-D crystal surface and crystal with eight deposition layers of PLL–HA and PLL–HADN. (d) Pull-out experiment of eight deposition layers on PCU disks for adhesive strength measurement presented in terms of force versus displacement. (e) Adhesion strength of PLL–HA and PLL–HADN coatings between PCU disks. Error bars represent the standard deviations over three independent measurements. The statistical differences (two-tailed Student’s t test) correspond to PLL–HA and PLL–HADN coatings, **p < 0.01.

An increasing in ΔD was detected at each step of PLL and HADN or HA injection due to the viscoelastic nature of the adsorbed polymeric layer. The structural softness of the eight layers was calculated by ΔD/Δf in Figure S4 but observed no significant difference between PLL–HA and PLL–HADN, indicating that the two coatings are similar with respect to their structural softness. By fitting a Voigt model25 to the frequency and dissipation shifts and using a coating density and viscosity of 1000 kg.m–3 and 1 mPa·s, respectively, PLL–HA and PLL–HADN coatings showed an exponential growth in thickness (Figure 1b) at each step, leading to thicknesses of 65 and 78 nm after eight-layer deposition, respectively. Silica spheres coated using the same protocol with PLL only, PLL–HA, and PLL-HADN (Figure S3) show zeta potentials of +47 ± 2.04, −23.9 ± 3.78, and – 34.58 ± 2.8 mV, respectively. The result shows that the positive zeta potential from PLL is completely masked by HA and HADN, and both PLL–HA and PLL–HADN coatings will be negatively charged in vivo. Significantly higher negative zeta potential of PLL–HADN as compared to PLL–HA can possibly be due to higher mass adsorption and thickness shown by QCM-D (Figure 1a,b). HADN can form covalent bonds between the catechol group on the HADN and the amine group in PLL by Michael addition or Schiff base in the physiological environment (pH = 7.4),32,34 leading to consolidation and a relatively higher mass adsorption of HADN as compared to HA (Figure 1a).

In the studies of Lee et al.32 and Neto et al.,25 around 100 nm thickness were obtained with chitosan and HADN for a 10-layer coating in an acidic solution (pH = 5), while here we found a slightly lower but of the same order less thickness of PLL–HA and PLL–HADN at a physiological environment (pH 7.4).

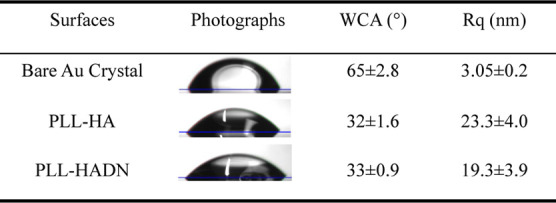

The roughness of the QCM-D crystal surface after the LbL assembly of PLL–HA and PLL–HADN both increased (Figure 1c and Table 1) sixfold as compared to the bare crystal. Other researchers have shown that after hydrophilic compound adsorption on the crystal, it causes an increase in roughness and a decrease in water contact.35 Increase in hydrophilicity is confirmed in our study too (Table 1) where the water contact angle on PLL–HA or PLL–HADN was half that of the bare crystal (65 ± 2.8o). The changes in the water contact angle and topography along with QCM-D results demonstrate the presence of PLL–HA and PLL–HADN coating on the crystal.

Table 1. Static Water Contact Angle (WCA) and Roughness (Rq) on Various Surfaces.

3.3. Adhesion of HA-Based LbL Coatings onto the Biomaterial (PCU)

The adhesion strength of the PLL–HADN coating on the PCU substrate was evaluated by a universal mechanical testing machine, according to the standard procedure ASTM D1002.25,26 The result show (Figure 1d) the adhesive strength for PLL–HADN to be 0.56 ± 0.21 MPa, which is significantly and 3.5-fold higher than 0.16 ± 0.05 MPa for PLL–HA (Figure 1e). The difference is caused by the dopamine modification of HA where the reason would be the same as the formation of a thicker layer, as mentioned above. After the adhesion test, PCU disks with the remaining coating were observed under AFM along with water contact angle measurements shown in Figure S5 and Table S1, respectively. It was shown that the roughness on PCU–PLL–HA (41.6 ± 3.9 nm) and PCU–PLL–HADN (57 ± 10.2 nm) was significantly higher than that of the bare PCU surface (11.6 ± 2.7 nm), while the water contact angle is lower than that of the bare PCU as well. This is an indication that on both detached plates, there are still parts of the polymer left, indicating a cohesive failure of the two LbL coatings and a very strong adhesive bond of the coating with the PCU surface. The obtained adhesive strength was lower than the results reported in other studies of a multilayer with a catechol group involved where an adhesive strength of 2 MPa25,26 was measured. The difference could be caused by the polycation; in the literature, chitosan was selected in an acidified solution, while here, PLL was selected, and all the experiments were performed in a physiological environment; furthermore, the substrates were different as well.

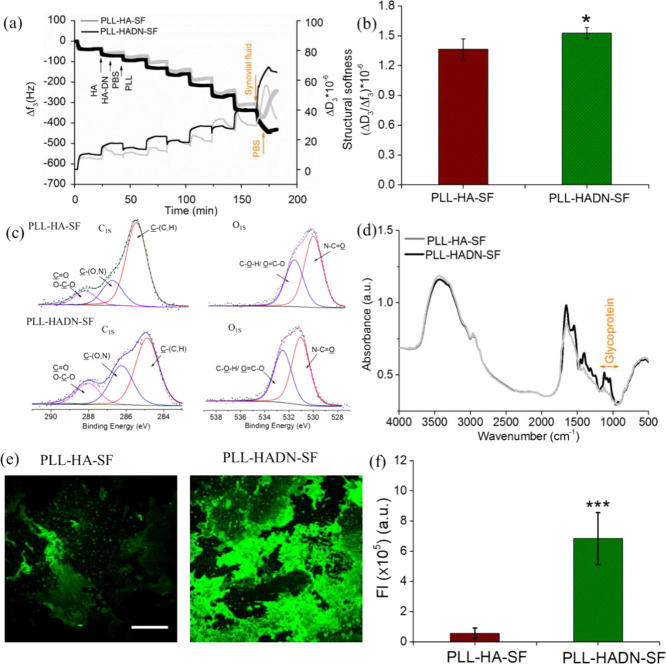

3.4. Response of PLL–HADN and PLL–HA Coatings to Synovial Fluid

HA, glycoproteins (PRG4 or lubricin), and surface active phospholipids (SAPL) working synergistically in forms of lamina splendens are responsible for remarkable boundary lubrication of the cartilage with a reported coefficient of friction of ∼0.005.4,36−38 PRG4 does not adsorb on biomaterials due to the blocking effect of albumin, which is abundantly present in the fluid.9 This lack of adsorption gives rise to a high coefficient of friction between the tissue and biomaterial, especially during the swing phase of the gait cycle.31 Thus, it is interesting to find out how the HA-based nanostructured coatings would interact with the synovial fluid. Figure 2a shows that upon injection of the synovial fluid in the QCM-D after eight-layer deposition of PLL–HA and PLL–HADN, a dramatic frequency shift around −431 ± 26 and – 342 ± 19 Hz of PLL–HADN–SF and PLL–HA–SF, respectively, was observed, indicating a larger amount of molecular adsorption on PLL–HADN as compared to PLL–HA from the synovial fluid. On PLL–HA, the synovial fluid molecules remain in contact while the synovial fluid is in contact; the moment the QCM-D chamber is purged with PBS, most of the adsorbed molecules rinse away with a return in frequency, indicating the weak adsorption of SF molecules on PLL–HA. On the contrary, for PLL–HADN–SF, the Δf and ΔD/Δf remain stable at −421 ± 18 Hz and 1.53 ± 0.05 × 10–6, respectively, suggesting a firm adsorption of synovial fluid constituents on the PLL–HADN surface. Such tight bonding of synovial fluid constituents on the PLL–HADN surface could be caused by the strong adhesive nature of HA–DN. The structure softness of PLL–HA–SF was found to be significantly lower than that of PLL–HADN–SF (Figure 2b), indicating a highly hydrated film of PLL–HADN–SF.

Figure 2.

Exposure of PLL–HADN and PLL–HA coatings to the synovial fluid formed PLL–HADN–SF and PLL–HA–SF coatings, respectively. (a) Adsorption of biomacromolecules on PLL–HADN and PLL–HA from the SF monitored using the QCM-D in terms of frequency (Δf) and dissipation (ΔD) shifts at the third overtone as a function of time. (b) Structural softness of the PLL–HA–SF and PLL–HADN–SF coatings in terms of the ΔD/Δf. (c) Relative contents of C and O on PLL–HA–SF and PLL–HADN–SF analyzed by XPS. (d) Composition of PLL–HA–SF and PLL–HADN–SF analyzed by ATR-FTIR spectroscopy. (e) Glycoprotein on surfaces stained with ConA and (f) their fluorescence intensity calculated with Image J. Scale bars represent 100 μm. Error bars represent the standard deviations over three independent measurements on separately prepared samples. Statistically significant (* = p < 0.05 and *** = p < 0.001 two-tailed Student’s t test).

Despite that fact that the catechol groups on HADN are needed for covalent bond formation with amine groups on PLL by Michael addition or Schiff base and for higher stability of the PLL–HADN coating (Figure 1a), some dopamine groups are still freely available on top of the PLL–HADN coating to manifest a strong interaction with the molecules present in the SF (Figure 2a).

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) in Table S1 and Figure 2c was used to analyze the elemental composition of the coating surface after exposure to synovial fluid. Table 2 shows the relative contents of C, N, and O. Significantly higher nitrogen (N) on PLL–HADN–SF (8.47 ± 0.65) as compared to PLL–HA–SF (6.9 ± 1.4) and the ratio of N/C that increased in PLL–HADN–SF (19.3 ± 1.4) compared to PLL–HA–SF (15.3 ± 2.2) indicate higher protein adsorption on the PLL–HADN surface. C1s spectra of each surface could be deconvoluted into three different curves: C–(C,H), C–N, and C=O, and their percentages for PLL–HADN–SF and PLL–HA–SF are different as shown in Table 3, suggesting different proteins detected on the surface.39 The O1s peak at 532.7 eV is related to the O from the glycoprotein,2,24 and the amount is 12.2 ± 0.43 on PLL–HADN–SF, which is significantly higher than 10.5 ± 0.35 found on PLL–HA–SF (Figure S6 and Table 3), suggesting higher glycoprotein (PRG4) adsorption on the PLL–HADN surface. The glycoprotein adsorption was confirmed by ATR-FTIR spectroscopy where the obvious higher absorption band from 950 to 1200 cm–1, the characterized band of the glycoprotein,40 was detected in PLL–HADN–SF (Figure 2d). For visual confirmation of glycoprotein adsorption, the films were stained with fluorescent conA (concanavalin A, Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate), which is a nonspecific stain for glycoproteins and mucins.41,42 The results in Figure 2e show that much more green fluorescence was visible on the PLL–HADN–SF as compared to the PLL–HA–SF surface and significantly higher than that of PLL–HA–SF in Figure 2f. The results of XPS, ATR-FTIR spectroscopy, and conA staining are in agreement that PLL–HADN can recruit glycoproteins like PRG4 from synovial fluid and immobilize glycoproteins tightly onto the surface. However, a similar phenomenon was not detected on PLL–HA coatings, which could be due to the interference of albumin in the interaction of PRG4 with HA.19 Dopamine modification of HA gives it an ability to interact with PRG4 and overcome the blockage offered by albumin. Most likely, on the PLL–HADN surface, both albumin and PRG4 were adsorbed as shown by the higher N concentration (Table 2).

Table 2. Elemental Composition of the PLL–HA–SF and PLL–HADN–SF Layers in Terms of C, N, and O Measured with XPS.

| atomic

percentages (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| samples | C | N | O | N/C |

| PLL–HA–SF | 45.1 ± 2.7 | 6.9 ± 1.4 | 27.4 ± 2.2 | 15.3 ± 2.2 |

| PLL–HADN–SF | 43.9 ± 0.12 | 8.47 ± 0.65 | 29 ± 3.46 | 19.3 ± 1.4 |

Table 3. Different Chemical Bonds Found in the PLL–HA–SF and PLL–HADN–SF Layers Measured Using ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy.

| C1s BE and relative area (%) |

O1s BE and relative area (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| samples | C–C | C–N | C=O | N–C=O | C–O–H/O=C–O |

| PLL–HA–SF | 66.8 | 21.2 | 12 | 60.2 | 39.8 |

| PLL–HADN–SF | 52.5 | 30.9 | 16.6 | 56.3 | 43.7 |

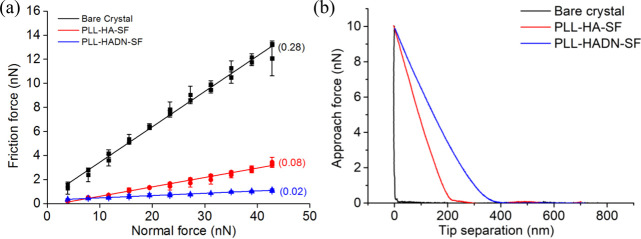

3.5. Nanolubrication Properties of PLL–HADN–SF or PLL–HA–SF Coatings

Colloid probe AFM is widely used in tribology research for its high sensitivity and ability to mimic boundary lubrication conditions at nanoscale.2 In the present study, this technique was used to measure the coefficient of friction of the nanostructured coating after exposure to the SF, i.e., PLL–HADN–SF or PLL–HA–SF. The AFM cantilever decorated with a 22 μm ϕ silica ball was pressed and slid against the coatings with increasing normal force of up to 43 nN in PBS; the protocol is described in vivid detail in the Supporting Information. Figure 3a shows the coefficient of friction (COF) of the bare QCM-D crystal to be 0.28, which is consistent with the literature.2 The COF significantly decreased to 0.08 for PLL–HA–SF and 0.02 for PLL–HADN–SF, respectively. This drop is both because of the nanostructured coatings and the PRG4 recruited from the SF (Figure 2a) for the PLL–HADN–SF, which yielded an extremely low COF (0.02). Contact of the AFM colloidal probe with the crystal (Figure 2b) shows a hard material compared with a softer film due to the long-range repulsive force between the film and approaching probe.2 The PLL–HADN–SF showed the longest range of repulsive force, indicating that it was a softer highly hydrated film. Lubricin (PRG4) and HA working synergistically are able to provide considerable boundary lubrication4,14 and yield a very low COF43 after adsorption on the soft surface. The behavior of lubricin (PRG4) adsorbed on the PLL–HADN coating surface is really interesting when compared to the findings of Majd et al,9 where PRG4 was unable to adsorb on HA due to the blocking effect of albumin. Here, we still found very limited PRG4 on the PLL–HA coating, but on PLL–HADN, a large amount of PRG4 was observed and yielded a low friction.

Figure 3.

Nanofrictional properties measured using colloidal probe AFM on the PLL–HADN–SF and PLL–HA–SF layers formed on the QCM-D crystal surface. (a) Friction force as a function of normal force during increasing and decreasing normal forces on the bare crystal and on the crystal surface with PLL–HA–SF and PLL–HADN–SF layers. (b) Example of the repulsive force measured as a function of tip separation distance from the bare crystal and from the crystal with PLL–HA–SF and PLL–HADN–SF layers. Error bars represent the standard deviations over three independent measurements on separately prepared samples.

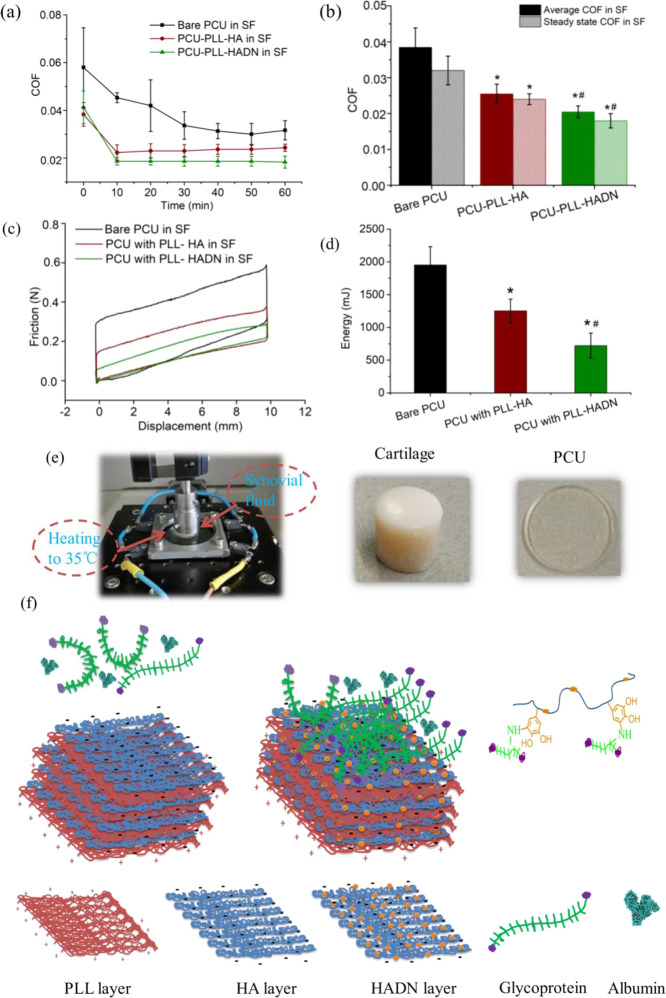

3.6. Ex Vivo Lubrication of Nanostructured PLL–HA and PLL–HADN Coatings on the PCU Surface against the Cartilage in Synovial Fluid

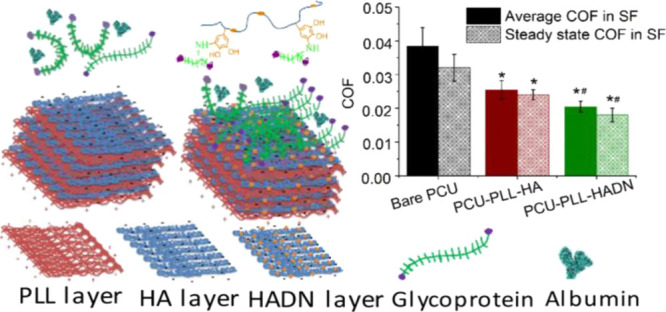

PCU is currently used for making a synthetic meniscus implant to replace a damaged meniscus implant,19,44 while its lubrication properties during the swing phase are suboptimal31 and need improvement. It was shown that in a low load (4 N), i.e., the swing phase of the gait cycle, the friction between PCU and the cartilage is an order of magnitude higher as compared to the natural meniscus and cartilage,31 increasing chances of cartilage wear while rubbing against PCU. Since the PLL–HADN multilayer shows high adhesive strength on the PCU surface and yields a high lubricity when exposed to synovial fluid at nanoscale, it is important to evaluate its lubrication performance at macroscale against the cartilage ex vivo (Figure 4). Cartilages from the bovine femoral head in the form of osteochondral plugs were slid against the PLL–HADN or PLL–HA on the PCU substrate at 4 mm/s under a constant load of 4 N in the presence of synovial fluid at 35°C19 to mimic the swing phase.

Figure 4.

Lubrication performance of the cartilage–PCU friction system in synovial fluid where the cartilage slides against bare PCU and with PLL–HA or PLL–HADN coatings at 35 °C, 4 mm/s, with a normal load of 4 N (giving rise to ∼0.4 MPa contact pressure) for 1 h (1.44 m total sliding distance). (a) Change in COF between the cartilage and different PCU surfaces in synovial fluid. (b) Average and steady state (at the end of 60 min) COF. (c) Typical friction force versus sliding distance curves on different surfaces at 30 min. (d) Frictional energy dissipation after1 h of sliding (720 cycles). (e) Images of the cartilage–PCU friction system and the typical osteochondral plug and PCU disk. (f) Schematic figure showing the layer-by-layer assembly of PLL–HA and PLL–HADN followed by the important role of dopamine-modified HA (HADN) in recruitment of glycoproteins (PRG4) from the synovial fluid despite the presence of albumin molecules. Error bars represent the standard deviations over three independent measurements on separately prepared samples. Statistically significant (p < 0.05, two-tailed Student’s t test) differences in COF (average and steady state) and energy dissipation on PCU–PLL–HA with respect to bare PCU are indicated by *. Significant differences in COF (average and steady state) and energy dissipation on PCU–PLL–HADN with respect to PCU–PLL–HA are indicated by #.

The result in Figure 4a shows that in the beginning, the COF is high, but after a few minutes, the COF decreases and becomes stable with a steady state COF. Respectively, the average and steady state COF (Figure 4b) between the cartilage and bare PCU are 0.037 ± 0.006 and 0.032 ± 0.004, which is significantly higher than that of PCU–PLL–HA (0.026 ± 0.003 and 0.024 ± 0.0015) and PCU–PLL–HADN (0.02 ± 0.002 and 0.018 ± 0.002). The typical friction force versus sliding distance curves on different surfaces at 30 min are shown in Figure 4c; the area value can be calculated by applying the definite integral algorithm.45 A larger area was obtained between the cartilage and bare PCU in Figure 4c, indicating that more energy dissipation and intensive wear46 happened between the cartilage and PCU. Significantly less energy dissipation in 1 h was obtained for PCU–PLL–HADN (722 ± 191 mJ) compared to PCU–PLL–HA (1251 ± 180 mJ) and on bare PCU (1952 ± 278.8 mJ) because of better lubrication obtained due to the PRG4 recruitment allowed by the PLL–HADN coating as shown in Figure 4f. The observation of COF and dissipated friction energy between cartilage–PCU with or without PLL–HA and PLL–HADN coating modification in synovial fluid suggests that the concentration of lubricant in the local environment is not the key factor in lubrication, but the amount of lubricant that are immobilized on the sliding surface plays a dominant role. A similar phenomenon was observed by Singh et al.21 who restored the cartilage lubrication through an HA-binding peptide to immobilize HA to the surface of the degraded cartilage. A similar strategy of HA recruitment was used on the contact lenses to enhance water retention.47 It has been demonstrated that energy loss naturally occurred in viscoelastic nonlinear materials, and the loss of energy in the process of reciprocal sliding friction was positively correlated to the surface injury.46,48

3.7. Surfaces Characterization of PCU–PLL–HA, PCU–PLL–HADN, and Cartilage after Sliding

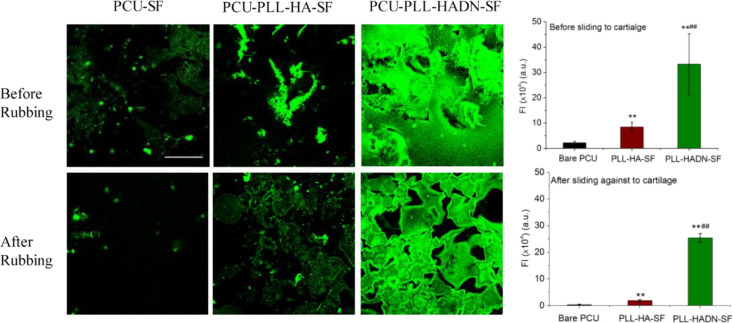

In order to clarify the mechanism and consequence during the tribology behavior before and after sliding, the PCU surfaces were stained with ConA, and the cartilage surfaces was studied using SEM, AFM, and histology. The result in Figure 5 shows very little green fluorescence on the bare PCU after 60 min (1.44 m) of sliding against the cartilage. On PCU–PLL–HA, the fluorescent intensity significantly (p < 0.01) decreased from 8.5 ± 1.8 (×105 a.u.) to 1.9 ± 0.4 (×105 a.u.), which could be caused by the poor adhesive ability of PRG4 on the PLL–HA surface. No significant decreasing of fluorescent intensity in PCU–PLL–HADN was observed before and after rubbing with a fluorescent intensity of 33.3 ± 12 (×105 a.u.) and 24.2 ± 2.5 (×105 a.u.), respectively, indicating that the glycoproteins were tightly immobilized on the PCU–PLL–HADN surface, and PLL–HADN remained tightly attached to PCU.

Figure 5.

ConA-Alexa-labeled glycoprotein (PRG4) recruited by bare and PLL–HA- and PLL–HADN-coated PCU surfaces from the synovial fluid. Error bars represent the standard deviations over three independent measurements on separately prepared samples. Statistically significant (p < 0.01, two-tailed Student’s t test) differences in fluorescence intensity on PCU–PLL–HA with respect to bare PCU are indicated by **. Significant differences in fluorescence intensity on PCU–PLL–HADN with respect to PCU–PLL–HA are indicated by ##.

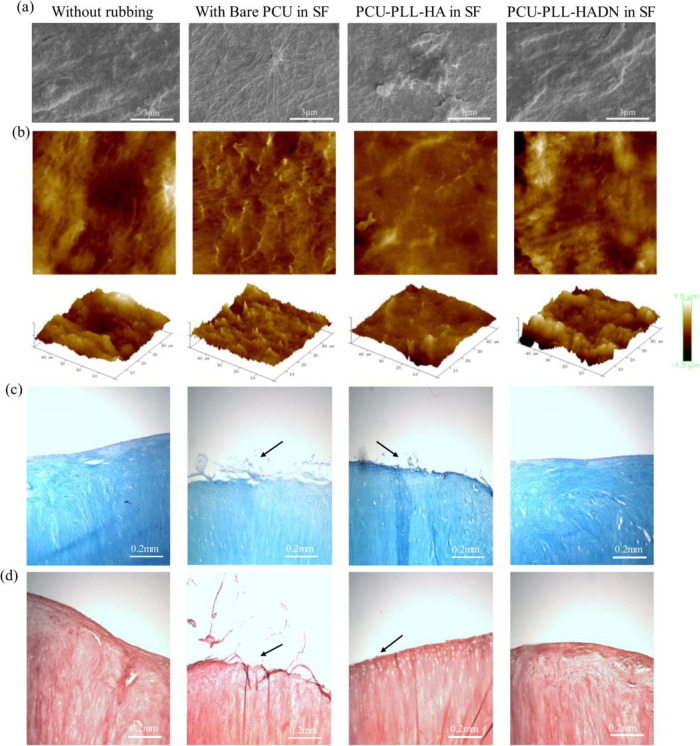

In the SEM images of the native cartilage without rubbing (Figure 6a), the surface was covered with uneven and amorphous protein layers, which could be the lamina splendens composed of various biomacromolecules on top of collagen fibers.19 The Rq-50 measured by AFM of the native cartilage was around 327 ± 23 nm as shown in Figure 6b, which is consistent with the Rq-100 reported in the literature.49,50 After rubbing against bare PCU in SF, the surface was different as shown in SEM images where the collagen fibers appeared on the surface without much change in roughness (335.5 ± 43 nm). It could be caused by the high friction force, leading to loss of the superficial layer from the cartilage surface and exposure of the collagen fibers. The amorphous protein layers were observed on cartilage surfaces after rubbing against PCU–PLL–HA and PCU–PLL–HADN in SF with roughness of 278 ± 63 and 301 ± 57 nm in Figure 6a,b, respectively. Although no significant difference in roughness was observed, the topography was obviously different as observed with AFM and SEM. The results of histological evaluation of the cartilage is shown in Figure 6c.d where cartilages were stained with Alcian blue for GAGs51 and acetic mucins and PR for collagen,51 respectively. In Figure 6c, the smooth margin with a lot of nuclei and GAGs is observed for the native cartilage without rubbing, and a similar phenomenon was found on the cartilage after rubbing against the PCU–PLL–HADN surface. Meanwhile, on the margin of the cartilage especially in the group of rubbing against bare PCU, an obvious damage with a rougher surface and a substantial reduction of GAGs on the top surface were induced. Compared to bare PCU, the cartilage surface rubbing against PCU–PLL–HA showed a rougher surface as well but not that severe. In Figure 6d, all cartilage samples showed a similar staining by PR, but similar rougher margins were observed on the cartilage after rubbing against PCU as indicated by black arrows. Some abrasion (black arrow) was also detected on the PCU–PLL–HA surface but not as severe as compared to bare PCU. Much less abrasion (wear) of the cartilage was visible after rubbing on PCU–PLL–HADN compared to the bare PCU and PCU–PLL–HA due to the higher lubrication and lower energy dissipation(Figure 4). The recruitment of PRG4 and protein synovial fluid on the PCU–PLL–HADN surface not only provides better lubrication (lowers friction) but it is also chondroprotective (lowers cartilage wear).

Figure 6.

Changes in the cartilage surface after 1 h (1.44 m) of sliding against the bare and PLL–HA- and PLL–HADN-coated PCU surface in the presence of synovial fluid. (a) SEM images of the cartilage showing craters in some cases. (b) AFM images of the cartilage surface. (c ,d) Histological section of the cartilage. (c) Cartilages slices stained with Alcian blue and nuclear fast red where Alcian blue stains glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), and nuclear fast red visualizes the nucleus of chondrocyte cells. (d) Collagen stained with Picrosirius red (PR). Panels (c) and (d) together show obvious surface damage (wear) on the cartilage after sliding against bare PCU and PCU–PLL–HA, while the cartilage surface sliding against PCU–PLL–HADN seems to remain unchanged.

The strategy of recruitment of native biomacromolecules from the surrounding milieu on a biomaterial surface to enhance lubrication is novel. Recruitment of HA on a biomaterial with the use of a specific HA-binding protein has been shown to increase the water retention ability of contact lenses21,47 but has not been used to enhance lubrication. Recruitment of PRG4 does not rule out the possibility of protein and lipid adsorption on PLL–HA or PLL–HADN, which may have contributed to lubrication.1

3.8. Cell Behavior on the LbL Assembly of PLL–HA and PLL–HADN Coatings

The nanostructured coating for artificial meniscus will come in static and sliding contact with the cartilage, thus we have tested the safety with the help of human chondrocyte cells cultured on PLL–HA and PLL–HADN coatings. However, integration of the coating with the cartilage tissue is still not necessary; when chondrocytes are seeded on the coating surface, they spread very well, and the overview images (Figure S7a) on each surface clearly display a gradual increase in surface coverage after 3 days compared to the 1 day period. The cell metabolic activity of the spread cells was measured by using an XTT assay (Figure S7b) (Applichem A8088). Cells after being cultured for 1 and 14 days on three kinds of surfaces do not show a significant difference, while in 3 and 7 days, the cell proliferation seems to be greater on the coated PCU surface even when no difference was observed between the PLL–HADN or PLL–HA coating. Differences observed on days 3 and 7 but not on day 14 could be due to the limited space since the number of cells increased after 14 days. The high biocompatibility of the HA-based LbL coating may attribute to the topography (Figure 1) and hydrophilicity (Table 1) of the surface, suggesting no toxicity of the coating in biomedical applications.

4. Conclusions

Nanostructured PLL–HA and PLL–HADN coatings were successfully obtained and were shown to be biocompatible. PLL–HADN showed high adhesion strength on polycarbonate urethane (PCU), a biomaterial used for permanent meniscus implants. The PLL–HA coating was able to adsorb PRG4 from the synovial fluid, but the use of dopamine-modified HA in the PLL–HADN coating was essential to recruit and tenaciously adsorb PRG4 even under high shear forces encountered while sliding against the cartilage surface. This tenacious recruitment of PRG4 on the PLL–HADN coating provided good lubrication and drastically reduced cartilage wear as compared to the bare PCU and PLL–HA coating. A proof of concept was obtained, and the similar locally binding and concentrated lubricious protein mechanism may also be applied to other tissue–medical device interfaces. These findings provide new key insights for the design and fabrication of biomimetic surface decoration, relevant for implantable biological interfaces.

Acknowledgments

The UMT-3 tribometer (Bruker) setup was purchased thanks to the grant no. ZonMW91112026 from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development. We also would like to thank the China Scholarship Council for a four-year scholarship to H.W. to pursue her PhD.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsami.0c04899.

Synthesis and characterization of HADN; zeta potential and structure softness of PLL–HA and PLL–HADN; surface topography, static water contact angle, and roughness after pull-out experiments; relative content of O from the glycoprotein (% O glycoprotein) of PLL–HA–SF and PLL–HADN–SF; and behavior of chondrocyte cells on different surfaces (PDF)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Seror J.; Zhu L.; Goldberg R.; Day A. J.; Klein J. Supramolecular Synergy in the Boundary Lubrication of Synovial Joints. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6497. 10.1038/ncomms7497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veeregowda D. H.; Kolbe A.; Van Der Mei H. C.; Busscher H. J.; Herrmann A.; Sharma P. K. Recombinant Supercharged Polypeptides Restore and Improve Biolubrication. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 3426–3431. 10.1002/adma.201300188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng C. C.; Cerretani C.; Braun R. J.; Radke C. J. Evaporation-Driven Instability of the Precorneal Tear Film. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014, 206, 250–264. 10.1016/j.cis.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn S.; Seror J.; Klein J. Lubrication of Articular Cartilage. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2016, 18, 235–258. 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-081514-123305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L.; Gaisinskaya-Kipnis A.; Kampf N.; Klein J. Origins of Hydration Lubrication. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6060. 10.1038/ncomms7060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan S. M. T.; Neu C. P.; DuRaine G.; Komvopoulos K.; Reddi A. H. Tribological Altruism: A Sacrificial Layer Mechanism of Synovial Joint Lubrication in Articular Cartilage. J. Biomech. 2012, 45, 2426–2431. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M. J.; Zhang Z.; Bott T. R. Effects of Operating Conditions on the Adhesive Strength of Pseudomonas Fluorescens Biofilms in Tubes. Colloids Surf., B 2005, 43, 61–71. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L.; Seror J.; Day A. J.; Kampf N.; Klein J. Ultra-Low Friction between Boundary Layers of Hyaluronan-Phosphatidylcholine Complexes. Acta Biomater. 2017, 59, 283–292. 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majd S. E.; Kuijer R.; Schmidt T. A.; Sharma P. K. Role of Hydrophobicity on the Adsorption of Synovial Fluid Proteins and Biolubrication of Polycarbonate Urethanes: Materials for Permanent Meniscus Implants. Mater. Des. 2015, 83, 514–521. 10.1016/j.matdes.2015.06.075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elsner J. J.; McKeon B. P. Orthopedic Application of Polycarbonate Urethanes: A Review. Tech. Orthop. 2017, 32, 132–140. 10.1097/BTO.0000000000000216. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ATRO Medical. TRAMMPOLIN - Meniscus replacement.

- Vrancken A. C. T.; Buma P.; van Tienen T. G. Synthetic Meniscus Replacement: A Review. Int. Orthop. 2013, 37, 291–299. 10.1007/s00264-012-1682-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.; Spencer N. D. Sweet, Hairy, Soft, and Slippery. Science 2008, 319, 575–576. 10.1126/science.1153273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang D. P.; Abu-Lail N. I.; Coles J. M.; Guilak F.; Jay G. D.; Zauscher S. Friction Force Microscopy of Lubricin and Hyaluronic Acid between Hydrophobic and Hydrophilic Surfaces. Soft Matter 2009, 5, 3438–3445. 10.1039/b907155e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faivre J.; Shrestha B. R.; Burdynska J.; Xie G.; Moldovan F.; Delair T.; Benayoun S.; David L.; Matyjaszewski K.; Banquy X. Wear Protection Without Surface Modification Using a Synergistic Mixture of Molecular Brushes and Linear Polymers. ACS Nano 2017, 1762. 10.1021/acsnano.6b07678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z.; Feeney E.; Guan Y.; Cook S. G.; Gourdon D.; Bonassar L. J.; Putnam D. Boundary Mode Lubrication of Articular Cartilage with a Biomimetic Diblock Copolymer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019, 116, 12437–12441. 10.1073/pnas.1900716116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgese G.; Cavalli E.; Müller M.; Zenobi-Wong M.; Benetti E. M. Nanoassemblies of Tissue-Reactive, Polyoxazoline Graft-Copolymers Restore the Lubrication Properties of Degraded Cartilage. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 2794–2804. 10.1021/acsnano.6b07847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi Y.; Kaper H. J.; Choi C.-H.; Sharma P. K. Tribological Properties of Microporous Polydimethylsiloxane ( PDMS ) Surfaces under Physiological Conditions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 561, 220–230. 10.1016/j.jcis.2019.11.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majd S. E.; Kuijer R.; Köwitsch A.; Groth T.; Schmidt T. A.; Sharma P. K. Both Hyaluronan and Collagen Type II Keep Proteoglycan 4 (Lubricin) at the Cartilage Surface in a Condition That Provides Low Friction during Boundary Lubrication. Langmuir 2014, 30, 14566–14572. 10.1021/la504345c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S.; Banquy X.; Zappone B.; Greene G. W.; Jay G. D.; Israelachvili J. N. Synergistic Interactions between Grafted Hyaluronic Acid and Lubricin Provide Enhanced Wear Protection and Lubrication. Biomacromolecules 2013, 14, 1669–1677. 10.1021/bm400327a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A.; Corvelli M.; Unterman S. A.; Wepasnick K. A.; McDonnell P.; Elisseeff J. H. Enhanced Lubrication on Tissue and Biomaterial Surfaces through Peptide-Mediated Binding of Hyaluronic Acid. Nat. Mater. 2014, 13, 988–995. 10.1038/nmat4048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan H.; Ren K.; Kaper H. J.; Sharma P. K. A Bioinspired Mucoadhesive Restores Lubrication of Degraded Cartilage through Reestablishment of Lamina Splendens. Colloids Surf. B 2020, 110977. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2020.110977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla K.; Ham H. O.; Nguyen T.; Messersmith P. B. Molecular Resurfacing of Cartilage with Proteoglycan 4. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 3388–3394. 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veeregowda D. H.; Busscher H. J.; Vissink A.; Jager D.-J.; Sharma P. K.; van der Mei H. C. Role of Structure and Glycosylation of Adsorbed Protein Films in Biolubrication. PLoS One 2012, 7, e42600 10.1371/journal.pone.0042600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neto A. I.; Cibrão A. C.; Correia C. R.; Carvalho R. R.; Luz G. M.; Ferrer G. G.; Botelho G.; Picart C.; Alves N. M.; Mano J. F. Nanostructured Polymeric Coatings Based on Chitosan and Dopamine-Modified Hyaluronic Acid for Biomedical Applications. Small 2014, 10, 2459–2469. 10.1002/smll.201303568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neto A. I.; Vasconcelos N. L.; Oliveira S. M.; Ruiz-Molina D.; Mano J. F. High-Throughput Topographic, Mechanical, and Biological Screening of Multilayer Films Containing Mussel-Inspired Biopolymers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 2745–2755. 10.1002/adfm.201505047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tatematsu M.; Katsuyama T.; Fukushima S.; Takahashi M.; Shirai T.; Ito N.; Nasu T. Mucin Histochemistry by Paradoxical Concanavalin a Staining in Experimental Gastric Cancers Induced in Wistar Rats by N-Methyl-N’-Nitro-N-Nitrosoguanidine or 4-Nitroquinoline 1-Oxide. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1980, 64, 835–843. 10.1021/acsnano.6b07678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotta K.; Goso K.; Kato Y. Human Gastric Glycoproteins Corresponding to paradoxical concanavalin a staining. Histochemistry 1982, 107–112. 10.1007/BF00493289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermann G. Manual Para Cálculo de Herbivoria. BioTechniques 2007, 43, S25–S30. [Google Scholar]

- NIH. ImageJ Image processing and analysis in java.

- Majd S. E.; Rizqy A. I.; Kaper H. J.; Schmidt T. A.; Kuijer R.; Sharma P. K. An in Vitro Study of Cartilage–Meniscus Tribology to Understand the Changes Caused by a Meniscus Implant. Colloids Surf B 2017, 155, 294–303. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.; Lee Y.; Statz A. R.; Rho J.; Park T. G.; Messersmith P. B. Substrate-Independent Layer-by-Layer Assembly by Using Mussel-Adhesive- Inspired Polymers. Adv. Mater. 2008, 20, 1619–1623. 10.1002/adma.200702378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W.; Qian J.; Hou G.; Suo A.; Wang Y.; Wang J.; Sun T.; Yang M.; Wan X.; Yao Y. Hyaluronic Acid-Functionalized Gold Nanorods with PH/NIR Dual-Responsive Drug Release for Synergetic Targeted Photothermal Chemotherapy of Breast Cancer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 36533–36547. 10.1021/acsami.7b08700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S.; Yang K.; Kang B.; Lee C.; Song I. T.; Byun E.; Park K. I.; Cho S. W.; Lee H. Hyaluronic Acid Catechol: A Biopolymer Exhibiting a PH-Dependent Adhesive or Cohesive Property for Human Neural Stem Cell Engineering. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23, 1774–1780. 10.1002/adfm.201202365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ye H.; Xia Y.; Liu Z.; Huang R.; Su R.; Qi W.; Wang L.; He Z. Dopamine-Assisted Deposition and Zwitteration of Hyaluronic Acid for the Nanoscale Fabrication of Low-Fouling Surfaces. J. Mater. Chem. B 2016, 4, 4084–4091. 10.1039/C6TB01022A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng G.; McNary S. M.; Athanasiou K. A.; Reddi A. H. Superficial Zone Extracellular Matrix Extracts Enhance Boundary Lubrication of Self-Assembled Articular Cartilage. Cartilage 2015, 7, 256–264. 10.1177/1947603515612190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNary S. M.; Athanasiou K. A.; Reddi A. H. Engineering Lubrication in Articular Cartilage. Tissue Eng. Part B 2012, 18, 88–100. 10.1089/ten.teb.2011.0394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seror J.; Sorkin R.; Klein J. Boundary Lubrication by Macromolecular Layers and Its Relevance to Synovial Joints. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2014, 25, 468–477. 10.1002/pat.3295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Chen Z.; Zhou B.; Duan X.; Weng W.; Cheng K.; Wang H.; Lin J. Cell-Sheet-Derived ECM Coatings and Their Effects on BMSCs Responses. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 11508–11518. 10.1021/acsami.7b19718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou J.; Veeregowda D. H.; van de Belt-Gritter B.; Busscher H. J.; van der Mei H. C. Extracellular Polymeric Matrix Production and Relaxation under Fluid Shear and Mechanical Pressure in Staphylococcus Aureus Biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, 1–14. 10.1128/AEM.01516-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-May E.; Hucko S.; Howe K. J.; Zhang S.; Sherwood R. W.; Thannhauser T. W.; Rose J. K. C. A Comparative Study of Lectin Affinity Based Plant N -Glycoproteome Profiling Using Tomato Fruit as a Model. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2014, 13, 566–579. 10.1074/mcp.M113.028969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura N.; Ota H.; Katsuyama T.; Akamatsu T.; Ishihara K.; Kurihara M.; Hotta K. Histochemical Reactivity of Normal, Metaplastic, and Neoplastic Tissues to α-LinkedN-Acetylglucosamine Residue-Specific Monoclonal Antibody HIK1083. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1998, 46, 793–801. 10.1177/002215549804600702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj A.; Wang M.; Liu C.; Ali L.; Karlsson N. G.; Claesson P. M.; Dėdinaitė A. Molecular Synergy in Biolubrication: The Role of Cartilage Oligomeric Matrix Protein (COMP) in Surface-Structuring of Lubricin. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 495, 200–206. 10.1016/j.jcis.2017.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serro A. P.; Degiampietro K.; Colaço R.; Saramago B. Adsorption of Albumin and Sodium Hyaluronate on UHMWPE: A QCM-D and AFM Study. Colloids Surf. B 2010, 78, 1–7. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scoppola E.; Sodo A.; McLain S. E.; Ricci M. A.; Bruni F. Water-Peptide Site-Specific Interactions: A Structural Study on the Hydration of Glutathione. Biophys. J. 2014, 106, 1701–1709. 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W.; Shi L.; Deng H.; Zhou Z. Investigation on Friction Trauma of Small Intestine in Vivo under Reciprocal Sliding Conditions. Tribol. Lett. 2014, 55, 261–270. 10.1007/s11249-014-0356-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A.; Li P.; Beachley V.; McDonnell P.; Elisseeff J. H. A Hyaluronic Acid-Binding Contact Lens with Enhanced Water Retention. Contact Lens Anterior Eye 2015, 38, 79–84. 10.1016/j.clae.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W.; Pang Q.; Lu M.; Liu Y.; Zhou Z. R. Rehabilitation and Adaptation of Lower Limb Skin to Friction Trauma during Friction Contact. Wear 2015, 332-333, 725–733. 10.1016/j.wear.2015.01.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.; Costa K. D.; Ateshian G. A. Microscale Frictional Response of Bovine Articular Cartilage from Atomic Force Microscopy. J. Biomech. 2004, 37, 1679–1687. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moa-anderson B. J.; Costa K. D.; Hung C. T.; Ateshian G. A. Bovine Articular Cartilage Surface Topography and Roughness in Fresh Versus Frozen Tissue Samples Using Atomic Force Microscopy. Nature 2003, 25, 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida H. V.; Cunniffe G. M.; Vinardell T.; Buckley C. T.; O’Brien F. J.; Kelly D. J. Coupling Freshly Isolated CD44+ Infrapatellar Fat Pad-Derived Stromal Cells with a TGF-Β3 Eluting Cartilage ECM-Derived Scaffold as a Single-Stage Strategy for Promoting Chondrogenesis. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2015, 4, 1043–1053. 10.1002/adhm.201400687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.