The world is still in the grip of a COVID-19 pandemic. The small part of the well-resourced world that I live in (the UK) is now focusing on trying to get back to some semblance of normality. Our thoughts are with those who are at a very different phase of dealing with the ravages of this virus, and in particular those in other parts of the world with far fewer resources.

The UK is one of the wealthiest countries in the world. We have a ‘free at point of care’ NHS or universal health coverage. We had a growing challenge with keeping up with demands for elective major surgery before COVID-19. This seemed to be common to all well-resourced countries and even worse elsewhere, as was well summarised in Ludbrook's editorial in the British Journal of Anaesthesia entitled the ‘Hidden pandemic of postoperative complications …’ published in 2018, well before we had seen the first surge of COVID-19.1 Dobbs and colleagues2 have now quantified the additional backlog of elective surgery in the NHS after the initial outbreak of COVID-19 in England (pre-vaccine era). They used robust national hospital episode statistics (HES) from England and comparable data from Wales to come up with an estimate of 2.3 million additional surgeries that are now added to the waiting lists that were already growing and out of control. To use a coastal analogy, as providers, we had big waves crashing down on us, we could see a tsunami on the horizon and the seas just got bigger. At the same time, we are all exhausted. Tired of stepping up, acting down (or un-retiring for some of us), extra shifts, proning teams, cancelled leave, lockdowns, personal protective equipment challenges, being infected with COVID-19, having long COVID, and so on. So, what now? Sink or swim? Do you want to be an agent of change and recovery? I think most of us do. But first, everyone should get a decent break, take a holiday, and rebuild some energy.

What should we do next? Systems work best when you have a dialogue from top to bottom and bottom to top. The very top usually does want to hear your great ideas, but we need to work via existing structures. You know your line manager. Do you know theirs, and the chain to the top? Who is your chief financial officer? Who sits on the board? Have you been to a board meeting or read the minutes? Learn to speak the lingo. Old adages: ‘Bring solutions not problems’; ‘it's not about the money – it's about the money’; ‘have an outline business case’; ‘know the cost of everything and the value of everything’; ‘own your problems’; ‘have an elevator pitch’ (e.g. ‘Did you know that death after surgery is now the third commonest cause of death in the world after cancer and heart disease and more than HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis together?’).

Then we must look on this as a challenge rather than a problem, and a massive opportunity rather than another crisis. The last global crisis was allegedly the financial crash of 2008–9. The UK was hit pretty badly, and the infamous handover note left for the incoming Minister of the Treasury read: ‘I'm afraid there is no money’.3 Well, there is a lot less now. I was privileged at that time (2008–13) to be a National Clinical Lead (with Alan Horgan, a surgeon from Newcastle, UK) for our NHS Enhanced Recovery Partnership Program.4 We saw the rapid spread and adoption of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) principles and practices throughout the NHS starting with major cancer surgeries (colorectal, urological, and gynaecologic) and primary hip and knee replacements, which resulted in reduced lengths of stay, fewer complications, no increases in readmissions, far greater levels of patient and provider satisfaction, cash savings, and increased bed availability; it was like opening a hospital for free.4 This program was all about quality and value (not cost), it was driven by data and change management experts, it focused on return on investment (ROI) rather than cost cutting. Circa 2010 things seemed to slow down again, and we saw less and less process and outcome data and reverted to more of a cost-cutting culture. Surgery waiting lists were starting to grow again by 2018 and then … COVID-19.2

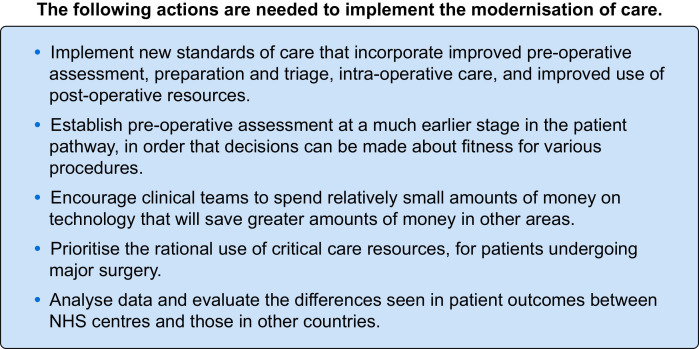

Whatever we come up with as a plan or strategy for the next 5–10 yr, it needs to be achievable and affordable, and rapidly deliver high value healthcare.5 , 6 It has been said that ‘the greatest innovation in modern healthcare would be to do what we know’. Here are six things that I think we know will make a difference. I classify them as ‘things we can't afford not to do’, as opposed to the usual excuse of ‘things we can't afford to do’. Five of the recommendations are the same ones a group of us made in the policy document entitled ‘Modernising Care of Patients Undergoing Major Surgery’ published in 2005 (Fig. 1 ). You may already be doing all of this (well done), but many of our institutions still are not.

Fig 1.

From: Bennett D, Emberton M, Garfield M, Grocott M, Mythen M (2007) Modernising Care for Patients Undergoing Major Surgery. London: The Improving Surgical Outcomes Group 2007, University College Hospital.

New standards of care

ERAS is supposed to have been the new standard of care in the UK since 20124 when a declaration was signed in public by our healthcare leaders. Yet I still go to virtual meetings where colleagues are talking about new ERAS pathways. There are no excuses for anything other than total ERAS and beyond.7, 8, 9 The pathways are all written and open access. For those still struggling to get local engagement with ERAS badged endeavours, I recommend focusing on the immediate postoperative phase using the DRink, EAt, Mobilize (DREAM) approach.10 Loftus and colleagues11 published results of a quality improvement programme in which they just focused on DREAM and delivered all the promises of ERAS. By focusing on this very tangible combined process and outcome, there is a natural adoption of enhanced recovery principles (e.g. less opioids, multimodal pain management, more precise fluid and haemodynamic management).

Re-engineer the surgical pathway

There are numerous working examples of re-engineering surgical pathways now in the NHS.12 13 Getting access to patients as close to the ‘moment of contemplation of surgery’ is key. Telephone or online triage allows RAG rating (Red, Amber, Green). Filtering out lower risk patients allows allocation of resource to the high-risk subset (about one in five), and enables shared decision-making and end-of-life discussions.12, 13, 14, 15 ‘Surgery schools’12 are appearing and there are anecdotal reports of greater patient engagement with ‘virtual surgery school’ since COVID lockdowns. COVID-19 has been a catalyst to many of these changes; there is probably no going back to over-use of the last-minute preoperative clinic. The ‘Fitter, Better, Sooner’ campaign has been promoted by the UK Royal College of Anaesthetists.16

Appropriate adoption of technology

Appropriate adoption of technology improves outcomes, but this has to be imbedded in a system that can evaluate the value proposition.5 , 7 , 12 Avoidance of major complications should be the focus. They are miserable for the patient and reduce the quality and quantity of life. They also consume bed days and reduce patient flows and productivity (opportunity costs). If adoption of novel technology reduces complication rates (e.g. acute kidney injury, lung injury, surgical site infections) then there will be an ROI. There are numerous such technologies to be considered (monitors, drugs, devices, etc.). It would be a false economy is to write them off based on acquisition cost.17 , 18

Lack of critical care beds

Lack of critical care beds in the UK (about 7 per 100 000 of population vs 20 in Germany, 25 in the USA, and an average of 12–14 in the EU) has been very obvious in the pandemic. Surge capacity has been provided by expansion into the operating rooms, recovery areas, and beyond with redeployment of staff. We just about kept up with demand within the acute hospital footprint and did not have to use temporary field hospitals to the extent that was originally predicted. However, this has accelerated the opening of the already proposed or planned Enhanced Postoperative Care or Level 1+ units.19, 20, 21 I recently participated in a Twitter fest of exchanges regarding naming such units (e.g. PERU vs PACU vs ESCU). We must keep the pressure up on this overdue expansion. The Modernising Care of Patients Undergoing Major Surgery policy document was motivated by this shortfall in acute care beds, and it was written in 2005!

Data, data, and more data

Death after surgery is now considered the third most common cause of death in the world after cancer and heart disease, and leads to more deaths than HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis together. Do you know the length of stay and readmission rates for the types of cases that you routinely care for? What about rates of acute kidney injury or wound infection? Gather all your available data and share it. You may already get regular reports that include the data recommended by the Perioperative Quality Initiative (POQI),22 but many of us do not. The minimum data set recommended by POQI should be reported to all of us.22 Benchmark as much as you can. Do an in-house evaluation. For example: ‘I wonder why we have top quartile results here, but bottom there?’ What can we learn from that? All of our hospitals have data. If you're not already, then be more interested in it and pester for it. We are part of the biggest industry in the world. We have to know what we do. And we are now even more highly motivated to do this. We are all providers, payers, and patients. In the UK we can join the Perioperative Quality Improvement Program (PQIP).23 A snap audit of DREAM rates can be done by one person with the back of an envelope and a pencil.10

Finally, not on the original list are research and disruptive innovation. Research active hospitals have better outcomes. Patients in research studies have better outcomes, including the control group.24 In the UK we have a national portfolio of approved studies (National Institute of Health Research [NIHR]) that attract additional research support funds.24 We have an excellent Perioperative Medicine Clinical Trials Network (POMCTN) that provides education, training, and support.25 The aftermath of a crisis is usually an excellent time for disruptive innovation. During the pandemic we have seen plenty of ‘thinking outside the box’ and rapid evaluation of new ways of working. For example I see no reason to go back to physical clinics when ‘virtual’ works well. It has been rather refreshing to be in ‘can do’ mode. Clinical trials, structured evaluation of novel technologies, quality improvement, and disruptive innovation are things we cannot afford not to do. As the cost cutting looms on the horizon, we must defend these activities. The original strap line for our NIHR was ‘for the Health and Wealth of the Nation’.

All of these proposed changes and more are supported by the UK Centre for Perioperative Care (CPOC). ‘CPOC is a cross-specialty centre dedicated to the promotion, advancement, and development of perioperative care, for the benefit of both patients and the healthcare community’.26 There is wealth of open-source materials on their website including many endorsed guidelines and publications.26

In parallel with the challenges and opportunities that are presented by the surgery backlog from the COVID-19 pandemic that is still raging in many parts of the world, we are also coming to terms with yet another silent pandemic: post-acute COVID-19, or ‘long COVID’ syndrome.27 The persistence of symptoms and delayed complications, long-term complications of COVID-19, or both, have been described in millions of patients. The organ-specific sequelae have been codified, and hypothesised pathophysiology is being formulated.27 However, successful management strategies and therapies have not been determined. Evidence-based guidelines on timing and type of surgical management for long COVID patients are, understandably, not yet available. Many long COVID patients have exacerbations triggered by ‘stress’. This is likely to be a major factor in planning surgery for such patients.

Whatever we face, we must stay calm and carry on. If we continue to lead (irrespective of our title) the delivery of safe, effective, patient-centred care, we will deliver the ‘triple aim’ of health, care, and cost.9 , 12 We are the stewards of fiscally responsible healthcare. We know what to do5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27; the greatest innovation would be to do it.4 , 11 I see enormous opportunity, but I think we are still starved of data.4 , 22 I can handle the truth.

Declaration of interest

The author is a member of the board of the British Journal of Anaesthesia. He is a paid Consultant for Edwards Lifesciences and Deltex Medical. He is a Director of Medinspire Ltd; EBPOM; TopMedTalk Ltd; an Ambassador for OBRIZUM; founding editor of Perioperative Medicine; co-president of the International Board of Perioperative Medicine; founding director of Morpheus Consortium; and founding director of the Perioperative Quality Initiative.

Footnotes

This editorial accompanies: Surgical activity in England and Wales during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationwide observational cohort study by Dobbs et al., Br J Anaesth 2021:127:196–204, doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2021.05.001

References

- 1.Ludbrook G. Hidden pandemic of postoperative complications-time to turn our focus to health systems analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2018;121:1190–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2018.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dobbs T.D., Gibson J.A.G, Fowler A.J. Surgical activity in England and Wales during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationwide observational cohort study. Br J Anaesth. 2021;127:196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2021.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.There is no money. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/may/09/liam-byrne-apology-letter-there-is-no-money-labour-general-election (accessed 12 May 2021).

- 4.Mythen M.G. Spread and adoption of enhanced recovery from elective surgery in the English National Health Service. Can J Anaesth. 2015;62:105–109. doi: 10.1007/s12630-014-0260-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ludbrook G., Riedel B., Martin D., Williams H. Improving outcomes after surgery: a roadmap for delivering the value proposition in perioperative care. ANZ J Surg. 2021;91:225–228. doi: 10.1111/ans.16571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peden C.J., Mythen M.G., Vetter T.R. Population health management and perioperative medicine: the expanding role of the anesthesiologist. Anesth Analg. 2018;126:397–399. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ljungqvist O., de Boer H.D., Balfour A. Opportunities and challenges for the next phase of enhanced recovery after surgery: a review. JAMA Surg. 2021 Apr 21 doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0586. [update] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fawcett W.J., Mythen M.G., Scott M.J. Enhanced recovery: joining the dots. Br J Anaesth. 2021;126:751–755. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts G.P., Levy N., Lobo D.N. Patient-centric goal-oriented perioperative care. Br J Anaesth. 2021;126:559–564. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levy N., Mills P., Mythen M. Is the pursuit of DREAMing (drinking, eating and mobilising) the ultimate goal of anaesthesia? Anaesthesia. 2016;71:1008–1012. doi: 10.1111/anae.13495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loftus T.J., Stelton S., Efaw B.W., Bloomstone J. A system-wide enhanced recovery program focusing on two key process steps reduces complications and readmissions in patients undergoing bowel surgery. J Healthc Qual. 2017;39:129–135. doi: 10.1111/jhq.12068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grocott M.P.W., Edwards M., Mythen M.G., Aronson S. Peri-operative care pathways: re-engineering care to achieve the 'triple aim. Anaesthesia. 2019;74(Suppl 1):90–99. doi: 10.1111/anae.14513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.A Teachable Moment. Available from: https://www.rcoa.ac.uk/sites/default/files/documents/2019-07/IntegratedCareSystems2019.pdf (accessed 12 May 2021).

- 14.Blackwood D.H., Vindrola-Padros C., Mythen M.G., Columb M.O., Walker D. A national survey of anaesthetists’ preferences for their own end of life care. Br J Anaesth. 2020;125:1088–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bloomstone J.A., Houseman B.T., Sande E.V. Documentation of individualized preoperative risk assessment: a multi-center study. Perioper Med (Lond) 2020;9:28. doi: 10.1186/s13741-020-00156-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swales H., Bougeard A.M., Moonesinghe R. Fitter, Better, Sooner: helping your patients in general practice recover more quickly from surgery. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70:258–259. doi: 10.3399/bjgp20X709841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fowler A.J., Dobbs T.D., Wan Y.I. Resource requirements for reintroducing elective surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic: modelling study. Br J Surg. 2021;108:97–103. doi: 10.1093/bjs/znaa012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sadique Z., Harrison D.A., Grieve R., Rowan K.M., Pearse R.M., OPTIMISE study group Cost-effectiveness of a cardiac output-guided haemodynamic therapy algorithm in high-risk patients undergoing major gastrointestinal surgery. Perioper Med (Lond) 2015;4:13. doi: 10.1186/s13741-015-0024-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ludbrook G., Lloyd C., Story D. The effect of advanced recovery room care on postoperative outcomes in moderate-risk surgical patients: a multicentre feasibility study. Anaesthesia. 2021;76:480–488. doi: 10.1111/anae.15260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lloyd C., Ludbrook G., Story D., Maddern G. Organisation of delivery of care in operating suite recovery rooms within 48 hours postoperatively and patient outcomes after adult non-cardiac surgery: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2020;10 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Enhanced Perioiperative Care. Available from: https://www.ficm.ac.uk/enhanced-care/enhanced-perioperative-care (accessed 12 May 2021).

- 22.Moonesinghe S.R., Grocott M.P.W., Bennett-Guerrero E. American Society for Enhanced Recovery (ASER) and Perioperative Quality Initiative (POQI) joint consensus statement on measurement to maintain and improve quality of enhanced recovery pathways for elective colorectal surgery. Perioper Med (Lond) 2017;6:6. doi: 10.1186/s13741-017-0062-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perioperative Quality Improvement Program (PQIP). Available from: https://rcoa.ac.uk/research/research-projects/perioperative-quality-improvement-programme-pqip (accessed 12 May 2021).

- 24.Centre for Perioperative Care (CPOC). Available from: https://www.nihr.ac.uk/health-and-care-professionals/engagement-and-participation-in-research/embedding-a-research-culture.htm (accessed 12 May 2021).

- 25.Perioperative Medicine Clinical Trials Network. Available from: https://rcoa.ac.uk/research/research-bodies/perioperative-medicine-clinical-trials-network (accessed 12 May 2021).

- 26.Guidelines and Resources. Available from: https://cpoc.org.uk/guidelines-and-resources (accessed 12 May 2021).

- 27.Nalbandian A., Sehgal K., Gupta A. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med. 2021;27:601–615. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]