Abstract

Summary

Guidelines for doctors managing osteoporosis in the Asia-Pacific region vary widely. We compared 18 guidelines for similarities and differences in five key areas. We then used a structured consensus process to develop clinical standards of care for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis and for improving the quality of care.

Purpose

Minimum clinical standards for assessment and management of osteoporosis are needed in the Asia-Pacific (AP) region to inform clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) and to improve osteoporosis care. We present the framework of these clinical standards and describe its development.

Methods

We conducted a structured comparative analysis of existing CPGs in the AP region using a “5IQ” model (identification, investigation, information, intervention, integration, and quality). One-hundred data elements were extracted from each guideline. We then employed a four-round Delphi consensus process to structure the framework, identify key components of guidance, and develop clinical care standards.

Results

Eighteen guidelines were included. The 5IQ analysis demonstrated marked heterogeneity, notably in guidance on risk factors, the use of biochemical markers, self-care information for patients, indications for osteoporosis treatment, use of fracture risk assessment tools, and protocols for monitoring treatment. There was minimal guidance on long-term management plans or on strategies and systems for clinical quality improvement. Twenty-nine APCO members participated in the Delphi process, resulting in consensus on 16 clinical standards, with levels of attainment defined for those on identification and investigation of fragility fractures, vertebral fracture assessment, and inclusion of quality metrics in guidelines.

Conclusion

The 5IQ analysis confirmed previous anecdotal observations of marked heterogeneity of osteoporosis clinical guidelines in the AP region. The Framework provides practical, clear, and feasible recommendations for osteoporosis care and can be adapted for use in other such vastly diverse regions. Implementation of the standards is expected to significantly lessen the global burden of osteoporosis.

Keywords: Asia-Pacific, Consensus, Guidelines, Osteoporosis, Standards of care

Introduction

Osteoporotic hip fractures among people in the Asia-Pacific region are expected to increase dramatically due to population aging, urbanization, and associated sedentary lifestyles [1]. Of these factors, population aging represents the major challenge, with the population of East Asia and the Pacific reported to be aging more rapidly than any other region in history [2]. The number of people who are 60 years and over in the Asia-Pacific region is predicted to triple between 2010 and 2050, reaching an estimated 1.3 billion by 2050 [3]. The old-age dependency ratio (OADR) is defined as the number of persons aged 65 years or over (assumed to be economically inactive) per 100 persons of working age (20 to 64 years). It provides an index of the economic dependency associated with aging populations and is expected to more than double in Eastern and South-Eastern Asia between 2019 and 2050, rising from 18 older persons per 100 workers in 2019 to 43 in 2050. It is predicted that Japan which was reported to have the highest OADR in the world in 2019 will remain in first position in 2050, followed closely by several other countries and regions in Eastern and South-Eastern Asia [4].

The Asia Pacific Consortium on Osteoporosis (APCO), a non-partisan and apolitical organization, is comprised of osteoporosis experts drawn from a diverse range of clinical settings, from low-, middle-, and high-income countries and regions in the Asia-Pacific that have populations ranging between 4.8 million and 1.4 billion people.

APCO aims to develop regionally relevant, pragmatic, and effective strategies for improving osteoporosis management and reducing rates of fragility fractures. Adoption of such strategies would lessen the burden of osteoporosis in this vast region that accounts for more than 60% of the world’s population [5]. We have previously described APCO’s raison d’etre, conception and launch, vision, mission, and priority initiatives [6].

Launched in May 2019, APCO’s first project was to develop clear and concise standards for the screening, diagnosis, and management of osteoporosis that are pan Asia-Pacific in their reach. This decision was based on anecdotal observations that existing guidelines for osteoporosis management within the Asia-Pacific region are heterogeneous and vary widely in scope and recommendations. Access to primary care services and bone mineral density (BMD) assessment varies across jurisdictions and regions, and little is known about adherence to current guidelines in day-to-day clinical practice. APCO therefore determined to (i) conduct a systematic, structured analysis of existing guidelines in the Asia-Pacific region, (ii) identify regionally relevant key guideline elements using a structured consensus process, and (iii) develop, through a structured consensus process, feasible regional clinical care standards that will both support clinical improvement initiatives and provide a framework for the development of new national clinical practice guidelines or the revision of existing ones.

This article describes the process by which, on a background of the existing guidelines in the Asia-Pacific region, APCO members developed and endorsed a new set of minimum standards of care that can be adapted and adopted across the region. We also highlight emerging themes in osteoporosis that have not yet been incorporated into any of the existing guidelines, but have enormous implications and potential to change the landscape of osteoporosis treatment.

Methods

A framework of minimum clinical care standards (the Framework) was developed in two stages: (i) a detailed comparative analysis of osteoporosis clinical practice guidelines in the Asia-Pacific region, and (ii) a structured consensus process to draft the standards.

Comparative analysis of osteoporosis guidelines in the Asia-Pacific region

Existing national or regional clinical practice guidelines and/or standards of care were identified through a survey among APCO members. A structured template was developed to facilitate standardized identification of guideline components. The template was based on the “5IQ” model (Table 1), modifications of which have been used to develop clinical standards for fracture liaison services (FLSs) in Japan [7], New Zealand [8], and in the UK [9].

Table 1.

The 5IQ model for analyzing the content of clinical practice guidelines

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

| Identification | A statement of which individuals should be identified |

| Investigation | A description of the types of investigations that will be undertaken |

| Information | A description of the types of information that will be provided to the individual |

| Intervention | A description of pharmacological interventions and falls prevention |

| Integration | A statement on the need for integration between primary and secondary care |

| Quality | A description of professional development, audit, and peer-review activities |

For each guideline, we identified the format in which the recommendations/information were provided and extracted details of these parameters. One hundred data elements were extracted from each guideline (the template used for extracting data from clinical practice guidelines is provided in Appendix 1):

Background information (8 elements).

Case identification (34 elements). Checklists of risk factors were derived from a recent review examining case-finding strategies from a global perspective [10].

Investigation (21 elements).

Advice and education for patients (5 elements).

Interventions (28 elements), including indications for treatment, treatments, recommendations for follow-up and duration of treatment, and recommendations for falls prevention. Given the complexity of indications, a coding system was created to allow quantitative comparison. Commentary on treatment/supplementation with calcium and/or vitamin D was also coded to compare the proportions of guidelines that recommended these options as active therapy, as distinct from adjunctive therapy alongside osteoporosis-specific treatments.

Strategies for long-term management and integration of osteoporosis care into the health system (2 elements).

Strategies to promote the quality of clinical care (2 elements).

Findings were analyzed separately for guidelines published between 2015 and 2020 (“newer guidelines”) and those published before 2015 (“older guidelines”).

Consensus process for developing the clinical care standards framework

A four-round Delphi process was adopted to develop standards of care for osteoporosis risk assessment, diagnosis, and management that are appropriate for the Asia Pacific region. The Delphi method has been widely used for establishing clinical consensus on other clinical conditions [11]. This structured approach ensures that the opinions of participants are equally considered, and it is particularly useful for geographically diverse groups like APCO. The Delphi process was conducted through online questionnaires.

Round 1

APCO members were invited to determine which aspects of care required clinical standards to be developed, based on a list informed by the findings of the 5IQ comparative analysis. The questionnaire included 32 questions under three domains (Appendix 2):

Domain 1. What are the notable findings from the 5IQ Comparative analysis of osteoporosis clinical guidelines from across the Asia Pacific region? Participants were referred to specific sections within the analysis report and invited to identify important findings.

Domain 2: How should the Framework be structured? Participants were asked to indicate how the Framework should be structured, including whether levels of attainment should be included for clinical standards to serve as potential quality performance indicators.

Domain 3. What clinical standards are required? For each of 21 key elements identified in the 5IQ analysis of Asia-Pacific clinical practice guidelines, participants were asked their opinion on the importance of its inclusion as a clinical standard (5-point scale from “extremely important” to “not at all important,” with optional free text comments). Consensus was defined as a ranking of “extremely important” or “very important” by at least 75% of respondents. Participants were also invited to make any general comments on development of the Framework.

Round 2

Members were asked to express their agreement (or not) with the wording of 16 draft clinical standards, of which several included proposed wording on levels of attainment (5-point scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”). For each draft standard, members were also invited to propose alternative wording or make comments. Consensus was defined as a ranking of “strongly agree” or “agree” by at least 75% of respondents.

Round 3

The wording of clinical standards and levels of attainment was amended, based on the results of Round 2. APCO members were invited to approve amendments (yes/no options). Consensus was defined as a “yes” response to a proposed rewording by at least 75% of respondents.

Round 4

A fourth round was conducted after some of the standards and levels of attainment were again reworded for clarity and precision without changing their intent. The minor amendments to the wording of the standards, with commentary itemizing each change, were sent to the APCO members who had participated in one or more of the previous Delphi rounds. Members were instructed to reply to the Chairperson by a stipulated date if they had any objection to the rewording of the standards.

Results

The analysis included 18 guidelines (Table 2) from the following regions: Australia [12], China (three guidelines) [13–15], Chinese Taipei [16], Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China (SAR) [17], India (two guidelines) [18, 19], Indonesia [20], Japan [21], Malaysia [22], Myanmar [23], New Zealand [24], the Philippines [25], Singapore [26], South Korea [27], Thailand [28], and Vietnam [29]. Of these, 14 (78%) were published between 2015 and 2020. Two-thirds of the guidelines did not specify a date for planned revision. Six stated that an update within 3–5 years was planned.

Table 2.

Osteoporosis management clinical practice guidance documents included in the 5IQ analysis

| Country or region | Organization(s) | Name of guideline |

|---|---|---|

| Australia | Osteoporosis Australia The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners | Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis and management in postmenopausal women and men over 50 years of age |

| China | Osteoporosis and Bone Mineral Disease Branch of Chinese Medical Association | Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of primary osteoporosis |

| China | Osteoporosis Society of China Association of Gerontology and Geriatrics | 2018 China guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of senile osteoporosis |

| China | Osteoporosis Group, Orthopedic Branch, Chinese Medical Association | Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of osteoporotic fractures |

| Hong Kong SAR | The Osteoporosis Society of Hong Kong | OSHK guideline for clinical management of postmenopausal osteoporosis in Hong Kong |

| Chinese Taipei | Taiwanese Osteoporosis Association | Consensus and guidelines for the prevention and treatment of adult osteoporosis in Taiwan |

| India | Indian Menopause Society | Clinical practice guidelines on postmenopausal osteoporosis: An executive summary and recommendations |

| India | Indian Society for Bone and Mineral Research | Indian Society for Bone and Mineral Research guidelines 2020 |

| Indonesia | Indonesian Osteoporosis Association (Perhimpunan Osteoporosis Indonesia) | Summary of the Indonesian guidelines for diagnosis and management of osteoporosis |

| Japan | Japan Osteoporosis Society The Japanese Society for Bone and Mineral Research Japan Osteoporosis Foundation | Japanese 2015 guidelines for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis |

| Malaysia | Malaysian Osteoporosis Society Academy of Medicine Ministry of Health Malaysia | Clinical guidance on management of osteoporosis |

| Myanmar | Myanmar Society of Endocrinology and Metabolism | Myanmar clinical practice guidelines for osteoporosis |

| New Zealand | Osteoporosis New Zealand | Guidance on the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in New Zealand |

| Philippines | Osteoporosis Society of Philippines Foundation Philippine Orthopedic Association | Consensus statements on osteoporosis diagnosis, prevention, and management in the Philippines |

| Singapore | Agency for Care Effectiveness, Ministry of Health Singapore | Appropriate care guide: osteoporosis identification and management in primary care |

| South Korea | Korean Society for Bone and Mineral Research | KSBMR Physician's Guide for Osteoporosis |

| Thailand | Thai Osteoporosis Foundation | Thai Osteoporosis Foundation (TOPF) position statements on management of osteoporosis |

| Vietnam | Vietnam Rheumatology Association | Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis |

Eleven of the guidelines were available in English. A professional medical translation agency was commissioned to translate four guidelines from Chinese, and the Vietnamese guideline was translated by an APCO member. Data extraction for the Japanese guidelines was undertaken by an APCO member and that for the Korean guideline was undertaken by a native speaker who was also an osteoporosis clinician.

Identification

Risk factors/indications for assessment and evaluation

Fifteen of the 18 guidelines cited risk factors separately for men and women, two guidelines for women only, and another did not state the sex to which cited risk factors applied.

The most commonly cited risk factors for osteoporosis (cited in at least half the guidelines) were excessive alcohol consumption (17 guidelines), a family history of osteoporosis and/or fractures (17 guidelines), smoking (17 guidelines), low body mass index (BMI)/weight (16 guidelines), height loss (13 guidelines), age over 70 years (13 guidelines), and early menopause (12 guidelines).

A range of other age thresholds for increased risk was also identified, with several citing one or more of the following: adults (four guidelines), postmenopausal women (three guidelines), 50 years and above (two guidelines), 60 years and above (one guideline), and 65 years and above in men (one guideline).

All 18 guidelines cited a history of fragility fracture as a risk factor for subsequent fracture. Thirteen of 18 guidelines specified the type of fragility fractures, most commonly spine, hip, proximal femur, wrist, forearm, distal radius, humerus, pelvis, and ribs. In the context of case identification, one guideline from China mentioned the importance of FLSs to promote multidisciplinary joint diagnosis and treatment.

While all the guidelines identified glucocorticoid treatment as being associated with bone loss and/or increased fracture risk, the lists of other medicines associated with bone loss varied between guidelines. More than half of the guidelines also identified users of androgen deprivation therapy (11/18 guidelines), anticoagulants (9/18 guidelines), anticonvulsants (10/18 guidelines), and aromatase inhibitors (11/18 guidelines) as at-risk groups. Other medications that were identified included proton pump inhibitors, thiazolidinediones, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

The medical conditions most frequently cited as risk factors were rheumatoid arthritis, malabsorption, hyperthyroidism, and multiple myeloma. Diabetes was noted as a risk factor in 10 of 14 (71%) of the newer guidelines, compared with none of the older guidelines.

Investigation

Biochemical tests

The extent of commentary on assays for bone turnover markers and other biochemical parameters varied considerably between the guidelines. Some guidelines only briefly mentioned biochemical tests in the evaluation of osteoporosis, while others provided detailed guidance. Total procollagen type 1 N-terminal propeptide (P1NP) was the most frequently recommended bone turnover marker (16/18 guidelines). Other laboratory tests that were commonly recommended in the guidelines included calcium, alkaline phosphatase, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, creatinine, urinary N-telopeptide (uNTX), parathyroid hormone (PTH), and osteocalcin.

Risk assessment tools

The FRAX® fracture risk assessment tool [30] was by far the most commonly recommended risk assessment tool (17/18 guidelines), followed by the Osteoporosis Self-Assessment Tool for Asians (OSTA) (11/18 guidelines) [31]. Some newer guidelines also recommended a range of other tools: the Garvan nomogram [32] (three guidelines), IOF Risk Check (“one-minute osteoporosis risk test”)[33] (three guidelines), the Khon Kaen Osteoporosis Study (KKOS) scoring system [34] (one guideline), the Male Osteoporosis Risk Estimation Score (MORES) [35] (1 guideline), QFracture algorithm [36, 37] (one guideline), and Simple Calculated Osteoporosis Risk Estimation (SCORE) [38] (one guideline).

Vertebral fracture assessment

All 18 guidelines mentioned the use of radiography to identify vertebral fractures, with some directly recommending x-ray of the thoracic and lumbar spine, some advising when it should be considered, and one simply noting that bone loss and healing fractures may be evident on radiographs. Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA)–based vertebral fracture assessment (VFA) was mentioned in eight guidelines, with guidance ranging from just statements of its existence or simple advice to consider DXA for identifying fractures, to the inclusion of DXA-identified fractures in treatment indications.

Falls risk assessment

Thirteen of 18 guidelines referred to the importance of falls risk assessment. The degree of detail varied widely with some amount of detail specified in the guidelines from Australia, China, Hong Kong SAR, Chinese Taipei, India, Malaysia, Japan, Thailand, and New Zealand. Some guidelines emphasized that falls risk assessment should be conducted routinely in all older adults (Australia), while others discussed falls risk assessment for patients known to be at risk of fragility fractures or with a history of fracture. One of the Chinese guidelines recommended that attention should be paid to the evaluation of fall-related risk factors in elderly patients with osteoporosis. Some guidelines recommended certain aspects of assessment, such as muscle strength and balance, while the Hong Kong SAR and one of the other Chinese guidelines provided comprehensive guidance on specific medical and environmental risk factors to consider when performing the assessment. Some mentioned strategies or structured tools for performing falls risk assessment (Thailand).

Specialist assessment

Ten of 18 guidelines recommended specialist referral for assessment in certain clinical scenarios. Four recommended that any patient with fragility fractures or osteoporosis should be referred for specialist assessment or care. Other specified scenarios included fracture or persistent loss of BMD despite treatment, complex conditions, problems considered “difficult” or beyond the scope of primary care, secondary osteoporosis, severe or unusual presentation, when first-line treatments were contraindicated or not tolerated, when assessment for specialized treatments is needed (e.g., teriparatide or long-term estrogen therapy), and when bone densitometry is not available.

Information

There was considerable variation in the extent to which the various guidelines recommended that specific information should be provided to patients.

Calcium intake and exercise

All 18 guidelines recommended that information should be provided on calcium intake, and 17 recommended providing information on exercise.

Sun exposure

Ten out of 18 guidelines (including one older guideline) recommended that patients should be provided with information on sun exposure to maintain healthy vitamin D levels.

Fracture risk

Only seven out of 18 guidelines (all newer guidelines) recommended that patients should be given information about the link between osteoporosis and fracture risk.

Intervention

Indications for treatment

All 18 guidelines cited BMD T-score of ≤ − 2.5 standard deviations (SD) as an indication for treatment. The reference database to be used to delineate T-scores was specified in only a minority of the guidelines. A broad range of other indications for treatment were cited in the various guidelines, with each guideline typically featuring three or four of a total of 14 indications identified.

Most guidelines cited hip and vertebral fractures as an indication for treatment. Fifteen of the 17 guidelines that included hip fracture as an indication for treatment, and all 17 guidelines that included vertebral fracture as an indication for treatment, stated that BMD testing was not required to initiate treatment. Of the 15 guidelines that included non-hip, non-vertebral fracture as an indication for treatment initiation, nine suggested that BMD testing was not necessary prior.

Thirteen guidelines mentioned or recommended treatment thresholds based on FRAX® probabilities. Six guidelines cited the threshold recommended by the US National Osteoporosis Foundation guidelines [39] (BMD T-Score in the osteopenic range, in combination with a FRAX® 10-year probability of ≥ 3% for hip fracture risk or ≥ 20% for major osteoporotic fracture risk). Of these, only two (the Malaysian guideline and one of the guidelines from China) explicitly recommended that this threshold should be adopted for their local target population. The Hong Kong SAR guideline stated that the US criteria were provided for clinical guidance only and that treatment decisions should consider individual patient factors. Other guidelines cited the US treatment threshold as an example or in commentary, without further interpretation.

Some guidelines provided guidance on the logistics and limitations of applying FRAX® to local populations. One of the guidelines from China [15] stated that the current prediction results may underestimate fracture risk in the Chinese population. Several others recommended the use of population specific FRAX® algorithms (e.g., Hong Kong SAR, India, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam).

Osteopenia in combination with other criteria (e.g., presence of risk factors, risk scores, ≥ 10 years post menopause) was included in several guidelines.

Pharmacological treatment options

Less than one-third of guidelines classified treatment options as first line, second line, and third line. All guidelines recommended bisphosphonates (oral and intravenous) and raloxifene as treatment options for osteoporosis. Most guidelines also recommended denosumab, teriparatide, and hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Predictably, the recently introduced treatments, abaloparatide and romosozumab, were recommended in only two newer guidelines (India and Korea).

Adjunctive treatments

Calcium and vitamin D were recommended as adjunctive therapies more often than as active treatments. That calcium was not a treatment option was explicitly stated in less than half of the guidelines.

Adverse effects

The volume of commentary on potential adverse effects of osteoporosis treatments varied considerably between guidelines. Eleven of 18 guidelines provided information on adverse effects associated with all or several classes of anti-osteoporosis agents.

Monitoring therapeutic response and long-term follow-up

Almost all the guidelines provided information on the role of repeated measurements of BMD and biochemical markers of bone turnover in monitoring. Some specified intervals for repeating tests (Table 3). Overall, there was limited guidance on making long-term management plans and providing them to the patient or primary care provider. Only two guidelines explicitly stated the need for a long-term plan, while 8 others implied the need for such planning.

Table 3.

Recommendations for timing of bone densitometry in follow-up

| Guideline | Mode | First test (if stated separately) | Intervals for repeat tests (if stated) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | DXA | – |

≥ 2 years when considering efficacy of treatment, risk assessment or decision to change or interrupt treatment Every 1 year in patients at high risk |

| China (Orthopedic) | DXA | 1 year after starting treatment | – |

| China (CSOBMR) | Unspecified (bone density measurement) | 1 year after starting or changing treatment | Every 1–2 years when effect has stabilized |

| China (Geriatrics) | DXA or QCT (if available) | – |

Unspecified (Monitor efficacy) |

| Biochemical markers of bone turnover | – | Every 3–6 months | |

| Chinese Taipei | DXA |

2 years after starting treatment < 2 years after starting treatment in patients with glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis |

– |

| Hong Kong SAR | BMD (not specified) |

1–2 years after starting treatment in patients treated with antiresorptive treatment 1 year after starting treatment in patients treated with bone-forming agents |

2–3 after therapeutic effect established |

| India (IMS) | DXA (use same DXA machine) | – | 2 years |

| India (ISBMR) | DXA (if available) | – | 2 years |

| Indonesia | BMD (not specified) | – | 1–2 to evaluate treatment response (defined as stable over 1 year) |

| Japan | BMD (not specified) | 1 year after starting treatment | > 1 year (unspecified)—after 1 year’s treatment with bisphosphonates, intervals longer than 1 year needed to see change in BMD |

| Malaysia | DXA | Not specified |

Not specified (Monitoring the effect of therapy) |

| New Zealand | BMD (not specified) | 4–5 years after starting treatment to determine whether bisphosphonates treatment should continue | ≥ 3 years (intervals < 3 years not recommended in most patients) |

| Singapore | DXA | 1–2 years after starting treatment to establish clinical effectiveness | Every 2–3 years after clinical effectiveness established |

| South Korea | DXA | – |

Every 1 year until normal BMD (T-score > − 1.0) 2 years after previous normal BMD |

| Thailand | DXA (Use same axial DXA analyzer) | – | > 1 year |

| Vietnam | Not specified | 1–2 years | 1–2 years |

BMD bone mineral density, DXA dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, QCT quantitative computed tomography

Treatment duration

Duration of treatment was specified in 13 guidelines and discussed very generally in two others. Most guidelines advised using bisphosphonates for 3–5 years before reassessing to determine whether to continue or discontinue with observation (“drug holiday”), based on assessment of treatment response and fracture risk. Another guideline recommended continuing bisphosphonate therapy for 5–10 years before reconsideration. Several guidelines gave detailed guidance based on risk assessment. Three guidelines recommended that teriparatide treatment should not exceed 2 years, while one guideline recommended 3 years of treatment with teriparatide. Of the four guidelines that discussed HRT and mentioned initiation of, and duration of therapy with it, one (Australia) recommended that its long-term use is not recommended. The Hong Kong SAR guideline recommended that patients should be adequately counselled on the risks and benefits of long-term use (beyond 3-5 years for combined estrogen-progesterone therapy and beyond 7 years for Estrogen alone therapy). The Indian Menopause Society guideline recommended it as first line therapy for women with menopausal symptoms for up to 10 years after menopause and specifically stated that HRT should not be started solely for bone protection after 10 years of menopause. The guidance from Singapore specified that menopausal hormone therapy can be considered for prevention of osteoporosis and fragility fractures in women who experience early menopause and that it can be continued until the normal age of menopause unless contraindicated. Of the two guidelines that mentioned duration of denosumab therapy, one recommended long-term use and the other recommended reevaluation of fracture risk after 5–10 years.

Adherence

Nine guidelines made specific recommendations on assessing and encouraging adherence.

Falls prevention programs

Five guidelines made specific recommendations for referral to falls prevention programs. A further three guidelines provided detailed commentary on falls risk assessment.

Integration

Overall, there was limited commentary on the need to develop a long-term management plan and provide it to the primary care provider and/or the patient. Only two guidelines explicitly referred to the need for a long-term care plan, while eight others implied that this was needed.

Though not specifically referring to the concept of integration and long-term planning, one guideline (South Korea) recommended the development of a secondary fracture prevention program that would be practical and suitable for their country to reduce re-fracture rates.

Quality

In general, there was limited commentary on audit of practice against standards, or on continuing professional development and learning that is required. One guideline (Chinese Taipei) advocated benchmarking the performance of FLSs against the IOF Capture the Fracture® best-practice framework standards [40]. Another (New Zealand) recommended auditing against national clinical standards for FLSs. One guideline (Malaysia) included an audit question to assess post-hip fracture osteoporosis care. The need for a national hip fracture registry was noted in one guideline (India). Several guidelines identified dissemination of clinical practice guidelines and ongoing continuing professional development as priorities for healthcare professionals involved in the provision of care for people living with osteoporosis.

Conclusions of the comparative analysis of existing guidelines

The 5IQ analysis confirmed previous anecdotal findings of marked heterogeneity among clinical practice guidelines for osteoporosis in the Asia-Pacific region—notably in guidance on risk factors, the use of biochemical bone turnover markers, self-care information for patients, indications for osteoporosis treatment, the use of fracture risk assessment tools, and protocols for monitoring treatment. Minimal guidance was provided on long-term management plans. Few mentioned strategies and systems for ensuring clinical quality improvement.

Outcomes of the Delphi process

The surveys were sent to current APCO members (n = 39), of whom 29 participated in one or more of the four rounds. Respondents were drawn from 18 countries/regions viz Australia (3), Brunei (1), China (1), Hong Kong SAR (2), Chinese Taipei (1), India (3), Japan (1), Korea (1), Malaysia (2), Myanmar (1), Nepal (1), New Zealand (3), Pakistan (1), Philippines (1), Singapore (2), Sri Lanka (1), Thailand (2), and Vietnam (1) and from the International Osteoporosis Foundation (1).

Round 1

Consensus was reached on the inclusion of clinical standards on the following components (i.e., ≥ 75% rated its inclusion as important or extremely important (Table 4)):

Identification of individuals with fragility fractures

Identification of individuals with common risk factors for osteoporosis, such as age 70 years or above, early menopause, excessive alcohol intake, family history, height loss, low body mass index/weight, prolonged immobility, smoking

Identification of individuals who take medicines associated with bone loss and/or increased fracture risk

Identification of individuals with conditions associated with bone loss and/or increased fracture risk

Use of risk assessment tools

Vertebral fracture assessment

Falls risk assessment

Information provided to patients on self-care, such as calcium intake, sun exposure, the relationship between osteoporosis and fracture risk, exercise

Indications for treatment to include hip fracture, vertebral fracture, and non-hip non-vertebral fracture

Recommendations for pharmacological interventions for specific patient subgroups

Recommendations for nonpharmacological interventions

Description of side effects of pharmacological treatments

Monitoring of pharmacological treatment

Duration of pharmacological treatment

Adherence to pharmacological treatment

Provision of long-term management plans to patients and/or primary care providers

Quality metrics for adherence to guideline-based care.

Table 4.

Delphi round 1 responses

| Component | Inclusion of standard on this component | Consensus (% rating as extremely or very important, i.e., ≥ 75%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extremely important | Very important | Somewhat important | Not so important | Not at all important | ||

| Identification | ||||||

| Fragility fracture | 22 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Yes (100%) |

| Risk factors for osteoporosis | 12 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 0 | Yes (92%) |

| Medicines associated with bone loss/fracture risk | 7 | 15 | 3 | 0 | 0 | Yes (88%) |

| Medical conditions associated with bone loss/fracture risk | 5 | 16 | 4 | 0 | 0 | Yes (84%) |

| Investigation | ||||||

| Biochemistry | 5 | 11 | 8 | 1 | 0 | No |

| BMD testing | 8 | 9 | 8 | 0 | 0 | No |

| Risk assessment tools | 12 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 0 | Yes (84%) |

| Vertebral fracture assessment | 14 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 0 | Yes (79%) |

| Falls risk assessment | 9 | 13 | 3 | 0 | 0 | Yes (88%) |

| Specialist referral | 4 | 11 | 8 | 2 | 0 | No |

| Information for patients | 14 | 7 | 4 | 0 | 0 | Yes (84%) |

| Intervention | ||||||

| Indications—see Table 5 | N/A | |||||

| Pharmacological | 10 | 12 | 3 | 0 | 0 | Yes (88%) |

| Non-pharmacological | 4 | 16 | 4 | 1 | 0 | Yes (80%) |

| Side effects | 6 | 15 | 3 | 1 | 0 | Yes (84%) |

| Monitoring effect | 11 | 11 | 3 | 0 | 0 | Yes (88%) |

| Duration | 13 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 0 | Yes (84%) |

| Adherence | 8 | 12 | 3 | 2 | 0 | Yes (80%) |

| Falls programs | 5 | 13 | 6 | 0 | 0 | No |

| Integration | ||||||

| Long-term management plans | 11 | 9 | 4 | 1 | 0 | Yes (80%) |

| Quality | ||||||

| Adherence to guideline-based care | 10 | 12 | 2 | 1 | 0 | Yes (88%) |

Respondents’ priority ratings for each of the key components identified in existing clinical practice guidelines. Consensus was defined as a rating of extremely important or very important by at least 75% of respondents

Sixteen standards were drafted based on this consensus. Although the initial intention was to draft levels of attainment for each standard, only a few standards proved amenable to this approach after collating respondents’ comments on priority rankings and levels of attainment. Levels of attainment were therefore drafted initially for five standards viz for those on (a) identification of fragility fractures, (b) identification of patients with common risk factors, (c) investigation of vertebral fractures, (d) assessment of adherence to pharmacological treatment, and (e) quality metrics to assess clinical adherence to guidelines. Each of these five standards had three levels of attainment, stratified according to degree of difficulty or feasibility of implementation.

Round 2

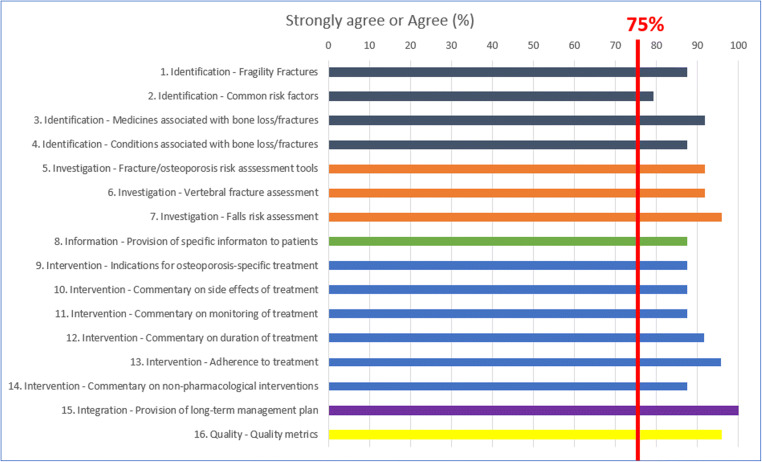

Consensus was reached (i.e., ≥ 75% of respondents strongly agreed or agreed) on the wording of all 16 standards (Fig. 1). Agreement was unanimous or nearly so (> 90% agreement) for the wording of draft standards on:

Proactive case identification based on medicines associated with bone loss/increased fracture risk

The use of country-specific fracture risk assessment tools, vertebral fracture assessment, and falls risk assessment

Duration of pharmacological treatment and adherence to pharmacological treatment

Long-term management plans

Metrics for adherence to guidelines

Fig. 1.

Delphi second-round consensus on wording of standards. The proportion of respondents who voted “strongly agree” or “agree” on the wording of 16 draft clinical practice standards

Diversity of opinion was greatest for the wording of the draft standard on proactive case identification based on common risk factors, although consensus was reached. The volume of comments (excluding minor editing suggestions) was highest for the standards on, medicines associated with risk, assessment of vertebral fractures, intervention thresholds for osteoporosis-specific therapies (Table 5), and assessment of adherence to pharmacological therapies.

Table 5.

Delphi round 1 responses: indications for initiating osteoporosis-specific treatment

| Indications | Selected (n) | Consensus (% rating as extremely or very important, i.e., ≥ 75%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| Hip fracture | 24 | 1 | Yes (96%) |

| Vertebral fracture | 24 | 1 | Yes (96%) |

| Non-hip non-vertebral fracture | 20 | 5 | Yes (80%) |

| BMD T-score ≤ − 2.5 SD | 18 | 7 | No |

| Osteopenia + FRAX® ≥ 3% hip or ≥ 20% MOF | 11 | 14 | No |

| Osteopenia + RFs or eligible by OSTA or SCORE | 7 | 18 | No |

| Osteopenia + ≥ 10 years post menopause | 3 | 23 | No |

| FRAX® or Garvan ≥ 3% hip or ≥ 20% MOF | 9 | 16 | No |

| Eligible by OSTA, MORES, or SCORE | 1 | 24 | No |

| QCT | 2 | 23 | No |

| Height loss > 4 cm | 11 | 14 | No |

| Androgen deprivation therapy | 10 | 6 | No |

| Aromatase inhibitor treatment | 9 | 16 | No |

| Glucocorticoid treatment | 17 | 8 | No |

| Country-specific thresholds | 14 | 11 | No |

BMD bone mineral density, MORES Male Osteoporosis Risk Estimation Score, OSTA Self-Assessment Tool for Asians, SCORE Simple Calculated Osteoporosis Risk Estimation, QCT quantitative computed tomography

The percentage of APCO member respondents who rated each of the proposed indications for initiating osteoporosis treatment identified in existing clinical practice guidelines, as extremely or very important for inclusion in APCO clinical practice standard 9

Draft standards from which levels of attainment were subsequently removed

Of the five standards that had levels of attainment drafted, consensus was reached on the wording of all except those on identification of patients with common risk factors (69.6% voted “strongly agree” or “agree”). For this standard, the proposed levels were as follows: Level 1—identification of individuals with common risk factors to include alcohol intake of ≥ 2 units per day, a family history of osteoporosis or fragility fracture, BMI ≤ 20 kg/m2, or a history of smoking. Level 2—identification of individuals with Level 1 common risk factors plus age ≥ 70 years and/or height loss of ≥ 4 cm compared to maximum height as a young adult. Level 3—identification of individuals with Level 1 and 2 common risk factors plus early menopause (defined as occurring before 45 years) and/or prolonged immobility. Issues noted by respondents for this included the difficulty of implementing these levels of attainment and the omission of particular risk factors (prolonged glucocorticoid use and falls risk). There were also concerns about defining levels according to numbers of risk factors, with suggestions that the levels should instead represent increasing percentages of at-risk patients identified, or be defined by the approach to case-finding, e.g., whether at-risk individuals are identified systematically or otherwise. Given the significant discordance among the participants, it was therefore decided by consensus that this standard would not be amenable to levels of attainment.

The threshold for consensus (75%) was reached on the wording of draft attainment levels for the standard on assessment of adherence to pharmacological therapy, but levels were not retained after several respondents queried the selection of cut-points and the feasibility of implementing the levels.

Thus, out of the five standards that were originally drafted with levels of attainment, we retained the levels in only three of them. These three standards were on (a) identification of fragility fractures, (b) investigation of vertebral fractures, and (c) quality metrics to assess clinical adherence to guidelines.

Members proposed alternative wordings for several standards and levels of attainment, including several of those that reached consensus. The chairperson and project manager analyzed the suggestions and drafted amendments.

Round 3

Consensus was achieved on all the proposed amendments, involving six standards, and levels of attainment for two standards. At the end of this round, consensus had been reached on the final Framework of minimum clinical standards.

Round 4

There were no objections to the minor amendments proposed to improve clarity and precision of the wording of some of the standards.

APCO Framework

Clinical standard 1

Men and women who sustain a fragility fracture should be systematically and proactively identified to undergo assessment of bone health and, where appropriate, falls risk.

Levels of attainment for clinical standard 1:

Level 1: Individuals who sustain hip fractures should be identified.

Level 2: Individuals who sustain hip and/or clinical vertebral fractures should be identified.

Level 3: Individuals who sustain hip, clinical and/or morphometric vertebral, and/or non-hip, non-vertebral major osteoporotic fractures should be identified.

Clinical standard 2

Men and women with common risk factors for osteoporosis should be proactively identified to undergo assessment of bone health and, where appropriate, falls risk. A sex-specific age threshold for assessment should be determined for each country or region and should be included in new or revised osteoporosis clinical guidelines.

Clinical standard 3

Men and women who take medicines that are associated with bone loss and/or increased fracture risk should be proactively identified to undergo assessment of bone health and, where appropriate, falls risk. A commentary should be included in new or revised osteoporosis clinical guidelines to highlight commonly used medicines that are associated with bone loss and/or increased fracture risk.

Clinical standard 4

Men and women who have conditions associated with bone loss and/or increased fracture risk should be proactively identified to undergo assessment of bone health. A commentary should be included in new or revised osteoporosis clinical guidelines to highlight common prevalent conditions in the country or region.

Clinical standard 5

The use of country-specific (if available) fracture risk assessment tools (e.g., FRAX®, Garvan, etc.) or osteoporosis screening tools (e.g., OSTA) should be a standard component of investigation of an individual’s bone health and prediction of future fracture risk and/or osteoporosis risk.

Clinical standard 6

Assessment for presence of vertebral fracture(s) either by X-ray (or other radiological investigations such as CT or MRI), or by DXA-based VFA should be a standard component of investigation of osteoporosis and prediction of future fracture risk.

Levels of attainment for clinical standard 6:

Level 1: Individuals presenting with clinical vertebral fractures should undergo assessment for osteoporosis.

Level 2: Individuals with incidentally detected vertebral fractures on X-ray and/or other radiological investigations should be assessed for osteoporosis.

Level 3: Individuals being assessed for osteoporosis should undergo spinal imaging with X-ray or other appropriate radiological modalities, or with DXA-based VFA.

Clinical standard 7

A falls risk assessment should be a standard component of investigation of an individual’s future fracture risk.

Clinical standard 8

In order to engage individuals in their own care, information should be provided on calcium and vitamin D intake, sun exposure, exercise, and the relationship between osteoporosis and fracture risk.

Clinical standard 9

The decision to treat with osteoporosis-specific therapies and the choice of therapy should be informed as much as possible by country-specific and cost-effective intervention thresholds. Intervention thresholds that can be considered include:

History of fragility fracture

BMD T-score ≤ − 2.5 S.D.

High fracture risk as assessed by country-specific intervention thresholds

Clinical standard 10

New or revised osteoporosis clinical guidelines should include a commentary on the common side effects of pharmacological treatments that are recommended in the guidelines.

Clinical standard 11

New or revised osteoporosis clinical guidelines should provide a commentary on monitoring of pharmacological treatments. This could include, e.g., the role of biochemical markers of bone turnover and bone mineral density measurement.

Clinical standard 12

New or revised osteoporosis clinical guidelines should provide a commentary on the duration of pharmacological treatments that are recommended in the guidelines. This should include a discussion on the appropriate order of sequential treatment with available therapies and the role of “drug holidays.”

Clinical standard 13

Assessment of adherence to pharmacological treatments that are recommended in new or revised osteoporosis clinical guidelines should be undertaken on an ongoing basis after initiation of therapy, and appropriate corrective action be taken if treated individuals have become non-adherent.

Clinical standard 14

New and revised osteoporosis clinical guidelines should provide a commentary on recommended non-pharmacological interventions, such as exercise and nutrition (including dietary calcium intake) and other non-pharmacological interventions (e.g., hip protectors).

Clinical standard 15

In collaboration with the patient, the treating clinician (hospital specialist and/or primary care provider) should develop a long-term management plan that provides recommendations on pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions to improve bone health and, where appropriate, measures to reduce falls risk.

Clinical standard 16

New or revised osteoporosis clinical guidelines should provide a commentary on what quality metrics should be in place to assess adherence with guideline-based care.

Levels of attainment for clinical standard 16:

Level 1: Conduct a local “pathfinder audit” in a hospital or primary care practice to assess adherence to APCO Framework clinical standards 1–9, 13, and 15.

Level 2: Contribute to a local fracture/osteoporosis registry.

Level 3: Contribute to a fracture/osteoporosis registry for your country or region.

The clinical standards are shown in Appendix 3.

Discussion

The 5IQ analysis of the multiple clinical practice guidelines on osteoporosis from Asia-Pacific countries and regions confirmed our understanding, based on previous anecdotal reports, that existing guidelines were markedly heterogeneous in terms of their scope and recommendations. The findings enabled APCO members to prioritize and select elements through the Delphi consensus method. The resulting minimum standards for care for the Asia-Pacific region are relevant, pragmatic, and feasible to implement.

Application of the Framework to clinical practice guidelines

Clinicians need information that is clear and readily accessible. Osteoporosis guidelines should clearly articulate which individuals should be identified for assessment, the investigations that should be offered, appropriate indications for treatment, the pharmacological treatments and other interventions that should be offered to specific patient groups, information on self-management that should be provided to patients, how the levels of healthcare systems should be integrated to ensure seamless care, and how the quality of osteoporosis healthcare services should be monitored and improved.

APCO’s goal is that all new or revised clinical practice guidelines for prevention, diagnosis, and management of osteoporosis in the Asia-Pacific region will:

be consistent with the scope proposed in the Framework,

promote the standards of care recommended in the Framework, and

recommend local benchmarking against the standards recommended in the Framework.

To achieve this, APCO members will identify opportunities in their individual countries and regions to share the Framework with colleagues and organizations involved in clinical practice guideline development. The clinical standards will be distributed in a modular format that should allow easy adoption at the individual health care facility, national or regional level.

Benchmarking and audit activities

Benchmarking against specific clinical standards is already used to measure the performance of osteoporosis care. Benchmarking of care for secondary prevention of fragility fractures is a component of the IOF Capture the Fracture® program [40], and of national fracture liaison service standards based on the 5IQ model [7–9]. Hip fracture registries, that have been established in several countries, also enable benchmarking of acute perioperative care and secondary fracture prevention after hip fracture [41–46].

After the Framework is published and it is disseminated, audit against benchmarks derived from the Framework will be undertaken at various healthcare system levels, ranging from individual healthcare provider or primary care medical practice level to hospital units, groups of hospitals, regions, or nations. The scale of activities can range from audit based on one selected standard to audit against several standards.

Initially, APCO members will be invited to undertake “pathfinder audits” in their hospitals to establish baseline levels of adherence with selected standards, such as BMD testing rates and osteoporosis treatment initiated during the episode of care. Follow-up audits will be conducted 12 months later to measure effects of implementing the standards.

Recently established and emerging themes in osteoporosis care

Several developments that significantly impact strategies for the management of osteoporosis have recently been brought to the forefront of medical management of osteoporosis. Predictably, the 5IQ analysis found that these were either not incorporated into existing guidelines or mentioned only briefly. However, they have enormous implications and potential to change the treatment landscape of osteoporosis and therefore need to be highlighted.

These include but are not limited to:

systematic integration of case identification and management at all levels of health systems, including acute care services, when patients present with fractures (e.g., through FLSs),

stratification of individual fracture risk,

the role of sequential therapies, and

the use of health economics to inform intervention thresholds and indications for specific classes of osteoporosis therapies.

Fracture liaison services

Up to 50% of patients with a hip fracture have already sustained fractures at other skeletal sites during the previous months or years [47, 48]. A prior fracture at any site is associated with a doubling of future fracture [49, 50] and mortality [51] risks. Accordingly, these “signal” or “sentinel” fractures should alert healthcare providers to the opportunity for secondary fracture prevention.

Over the past decade and a half, coordinated post-fracture models of care have been designed to ensure that healthcare providers consistently respond to the first fracture to prevent the second and subsequent fractures [48]. These are generally hospital-based, but involvement of primary care physicians is also important to ensure continuity of care [52, 53]. Components of effective FLSs include multidisciplinary involvement, dedicated case managers and clinician champions, regular assessment and follow-up, multifaceted interventions, and patient education [54].

Fracture liaison service programs significantly increase rates of BMD testing, initiation of osteoporosis treatment, adherence to treatment, and reduce refracture incidence and mortality rates, compared with usual care [54, 55]. They are cost-effective in comparison with usual care or no treatment, regardless of the program intensity or the country [55]. The IOF strongly promotes the concept of FLSs through its global Capture the Fracture® initiative [40]. This initiative has set an international benchmark for FLSs by defining 13 globally endorsed standards for service delivery.

Fracture liaison services in the Asia-Pacific and reference to these in the extant guidelines

The number of FLSs in the Asia-Pacific region is rapidly increasing. Analyses of indigenous fracture liaison programs have been conducted in several countries and regions in the Asia-Pacific region including Australia [56], China [57, 58], Chinese Taipei [59], Hong Kong SAR [60], Singapore [61], Japan [62–64], New Zealand [65], South Korea [66–69], and Thailand [70]. In 2017, the fracture liaison service consensus meeting held in Taipei concluded that the 13 Best Practice Framework Standards of the IOF’s Capture the Fracture® campaign [40] were generally applicable in the Asia-Pacific region (albeit with minor modifications). As of 17 September 2020, 111 FLSs from the Asia-Pacific region are included on the IOF Global Map of Best Practice (https://www.capturethefracture.org/map-of-best-practice). Eighty-four have been fully evaluated, of which 19 have been awarded a Gold star. These include FLSs from Australia, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, Taiwan, and Thailand.

Despite this burgeoning interest, the 5IQ analysis revealed that only four guidelines in the Asia-Pacific region advocated the role of FLSs, suggesting that the crucial role of secondary fracture prevention is still sadly under-recognized among guideline developers and policy makers in the Asia-Pacific [52]. Two recent initiatives are, however, expected to enable more widespread adoption of FLSs in the region: the FLS tool box for Asia-Pacific developed by the Asia-Pacific Bone Academy Fracture Liaison Service Focus Group [71], and the Capture the Fracture® Partnership launched by the IOF (https://www.capturethefracture.org/capture-fracture-partnership), which includes several countries in the Asia Pacific region.

Risk stratification

Upon the knowledge that “fractures beget fractures” [47, 49, 50] has subsequently come the understanding that the risk of a subsequent fragility fracture is particularly acute immediately after the sentinel or the index fracture and that this risk wanes progressively with time [72–78]. This very high fracture risk in the 1 to 2 years after the index fracture has been termed “imminent risk” [79, 80] and appears to be age-dependent, with the transient effect of increased risk being more evident at older ages [76]. The ratio of 10-year fracture probability after a recent fragility fracture to that after a fracture, irrespective of its site or recency, has been termed the probability ratio or adjustment ratio. Probability ratios that provide adjustments to conventional FRAX® estimates for recency of sentinel fractures have now been derived, though how they will be included in the FRAX® algorithm is still being debated [81].

Other factors can also contribute to, or result in, a very high fracture risk. The simultaneous presence of multiple risk factors (e.g., family history of fracture, glucocorticoid use) can additively contribute to fracture probabilities and shift fracture risk categories to higher strata of risk [30]. Individuals have also been somewhat arbitrarily designated as very high risk if they have fractures while on approved osteoporosis therapy, have multiple prevalent fractures or fractures while on drugs causing skeletal harm such as glucocorticoids, have very low T-score (e.g., < − 3.0), have high risk for falls or a history of falls, or have a FRAX® probability for major osteoporosis fracture > 30%, or hip fracture > 4.5% over a 10-year period [82].

This concept of stratification of osteoporotic fracture risk that may enable or guide the choice of therapeutic agent is gaining traction globally. Those at higher risk may require initiation of treatment with more potent therapies such as an anabolic agent. For those at low risk, a decision will need to be made on whether therapy with an anti-osteoporosis agent is even indicated. Updated position papers and guidelines published by the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis (ESCEO) and the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) [80] and by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) [82] provide recommendations for this stratification of risk. The ESCEO/IOF position paper applies age-specific thresholds to define high versus very high risk, while the AACE guidelines suggest an arbitrarily decided fixed threshold as well as the presence of certain pre-defined risk factors as described previously [80, 82].

At a regional and national level, these recommendations will have to be reviewed to determine the relevance to local practices and to see whether they offer tangible benefits to patients. Some challenges to implementation of these guidelines in the Asia-Pacific would need to be considered. The FRAX® thresholds that are recommended in the AACE guidelines are likely only applicable to the USA. While FRAX® has been validated in many Asian countries, most of them have not implemented specific intervention thresholds for use yet. Recommendations also need to consider local reimbursement criteria, which often dictate eligibility criteria for pharmacological treatment options.

Sequential therapies in osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is a chronic condition. Therefore, patients with osteoporosis need a long-term, personalized management plan, with many patients requiring multiple anti-osteoporosis medications during their lifetime. The specific and individualized treatment plan traditionally has involved initiation of therapy with an antiresorptive agent. Most of the extant guidelines in the Asia-Pacific region also favor this approach. However, there is evidence for a stronger anti-fracture efficacy of bone-forming treatments compared to antiresorptive ones from two clinical trials in patients with severe osteoporosis [83, 84] and for a blunted/delayed BMD response to bone-forming treatment, with prior antiresorptive use, though this effect somewhat depends on the potency of the antiresorptive agent [85–87].

In certain scenarios, a deleterious effect on BMD is seen in patients previously treated with antiresorptive agents who are then switched to an anabolic agent [88]. In contrast, sequential therapy with an anabolic agent followed by an antiresorptive agent appears largely to be associated with maintenance or continued increase in BMD [88] and continued reduction in fractures [84, 89].

This has resulted in increasing interest in sequential treatment with an anabolic agent given as first-line treatment in the very-high-risk fracture patient, whose fracture risk needs to be addressed quickly and in whom BMD needs to be improved quickly and as much as possible. However, the fact that this may not always be possible, due to restrictions in reimbursement criteria and limitations imposed by guidelines, should be considered before advocating large-scale adoption of such recommendations.

Health economics

Health economic analysis is playing an increasingly important role to inform the relative value of osteoporosis therapies and to help determine how best to allocate finite health care resources. The development of absolute fracture risk–based assessment and intervention thresholds has led also to the exploration of cost-effectiveness of interventions along the lines of fracture probability. A significant body of evidence now exists to show that anti-osteoporosis therapies are cost-effective in women at high risk of fracture [90].

However, the cost-effectiveness of various pharmacological therapies is determined in part by the costs and benefits of treatment. Intervention thresholds will also vary, since they depend critically on country- and region-specific factors such as reimbursement issues, health economic assessment, willingness to pay for healthcare, and access to DXA scanning. Due to this vast heterogeneity in epidemiologic and economic characteristics between countries, such thresholds should be country-specific. In the USA, a 10-year absolute hip fracture probability of 3% and its equivalent major osteoporotic fracture probability of 20% have been considered as cost-effective intervention thresholds [39]. Various other major osteoporotic fracture risk fixed intervention thresholds ranging from 7 to 15% have been deemed to be cost-effective in other countries [91, 92]. In the UK, age-dependent FRAX®-based intervention thresholds have been shown to provide clinically appropriate access to treatment as well as to be cost-effective [93].

Given the evidence supporting initial treatment of patients at very high risk of fragility fracture with an anabolic agent followed by consolidating the effect of these agents with antiresorptive agents, health economic appraisals exploring the cost-effectiveness of such sequential therapies are also slowly emerging [94].

Health economic evaluation studies in osteoporosis are few in the Asia-Pacific region. Robust studies have been conducted in a few countries including Singapore [95], China [96, 97], Japan [98, 99], and Australia [100]. These studies have employed different modeling strategies and have explored cost-effectiveness of fracture intervention thresholds as well as of various osteoporosis medications. The varying results obtained from these studies highlight the crucial differences in economic, epidemiological, and clinical practice factors between the countries in the vast region that is the Asia-Pacific.

Conclusions

The APCO Framework represents the first consensus minimum standards of osteoporosis care, purpose-developed by clinicians for the whole of the Asia-Pacific region. Developing it through a comparative analysis of extant guidelines in the Asia Pacific region and through the consensus of experts from diverse health care systems enables the recommendations to be practical and relevant to the unique needs of this vast and populous region. However, publishing and disseminating the Framework is only half the battle won. The success of the Framework will be discernible only after the standards have been implemented throughout the region and its efficacy has been systematically measured.

The Framework provides accessible, clear, and feasible recommendations for osteoporosis care in the Asia Pacific region. It is hoped that the Framework will inform national societies, guideline development authorities, and health care policy makers in the development of new guidelines and promote the revision of existing guidelines. The principles and processes behind its development can be translated and adapted to other regions of the world that also face similar socioeconomic diversity and heterogeneity of healthcare resources. The implementation of the Framework, or similar sets of standards of care inspired by it, is thus expected to significantly reduce the burden of osteoporosis, not only in the Asia Pacific region, but also globally.

Emerging concepts in osteoporosis care and technologies should also be keenly followed and should be incorporated into new and revised guidelines after careful deliberation on their applicability to local health care practices.

Acknowledgments

Linguistico (Sydney, Australia) provided English translations of the four Chinese clinical practice guidelines. Dr. David Kim performed data extraction for the South Korean guidelines. Editorial assistance and writing support were provided by Ms Jennifer Harman of Meducation Australia Pty. Ltd., contracted by APCO for the purpose.

APCO executive committee

Dr. Manju Chandran (Chairperson), Singapore General Hospital, Singapore

Dr. Philippe Halbout, International Osteoporosis Foundation, Nyon, Switzerland

Dr. Greg Lyubomirsky, Osteoporosis Australia, Sydney, Australia

Professor Peter Ebeling, Monash Health, Melbourne, Australia

Professor Tuan V. Nguyen, Garvan Institute of Medical Research, Sydney, Australia

Professor Xia Weibo, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Beijing, China

Dr. Cae Tolman, Amgen Asia, Industry Representative, Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR (non-voting member)

Dr. Tiu Kwok Leung, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR

Professor Sanjay K. Bhadada, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER), Chandigarh, India

Mr. Paul Mitchell, APCO Project Manager, Synthesis Medical NZ Limited, Auckland, New Zealand (non-voting member)

Dr. Nigel Gilchrist, Canterbury District Health Board, Christchurch, New Zealand

Dr. Aysha Habib Khan, Aga Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan

Dr. Sarath Lekamwasam, University of Ruhuna, Matara, Sri Lanka

APCO members: Dr. Tanawat Amphansap (Police General Hospital, Thailand), Professor Manoj Chadha (Hinduja Hospital and Research Centre, India), Professor Ding-Chen Chan (National Taiwan University Hospital, Chinese Taipei), Professor Yoon-Sok Chung (Ajou University School of Medicine, Republic of Korea), Dr. Hew Fen Lee (Subang Jaya Medical Centre, Malaysia), Professor Kee Hyung Rhyu (Kyung Hee University, Republic of Korea), Dr. Lan T. Ho-Pham (Pham Ngoc Thach University of Medicine, Vietnam), Professor Tint Swe Latt (Shwe Baho Hospital, Myanmar), Dr. Edith Lau (Hong Kong Orthopaedic and Osteoporosis Center for Treatment and Research, Hong Kong SAR), Dr. Lau Tang Ching (National University Hospital, Singapore), Dr. Dong Ock Lee (National Cancer Center, Republic of Korea), Dr. Lee Joon Kiong (Beacon International Specialist Centre, Malaysia), Professor Liu Jianmin (Shanghai Ruijin Hospital, China), Professor Leilani B. Mercado-Asis (University of Santo Tomas), Professor Ambrish Mithal (Max Healthcare - Pan-Max, India), Dr. Dipendra Pandey (National Trauma Centre, Nepal), Professor Ian R. Reid (University of Auckland, New Zealand), Professor Atsushi Suzuki (Fujita Health University, Japan), Professor Akira Taguchi (Matsumoto Dental University, Japan), Associate Professor Vu Thanh Thuy (Bach Mai Hospital, Vietnam), Dr. Tet Tun Chit (East Yangon General Hospital, Myanmar), Dr. Gunawan Tirtarahardja (Indonesian Osteoporosis Association), Dr. Thanut Valleenukul (Bhumibol Adulyadej Hospital, Thailand), Dr. Yung Chee Kwang (Raja Isteri Pengiran Anak Saleha Hospital, Brunei Darussalam), Dr. Zhao Yanling (Beijing United Family Hospital, China).

Appendix 1 Template for extracting data from clinical practice guidelines (modified 5IQ model)

| Publication information and format | |

|---|---|

| 1. Country/region | |

| 2. Sponsor organization | |

| 3. Year | |

| 4. Number of pages | |

| 5. Review date | |

| 6. Guideline published in English (Yes/No) | |

| 7. Corresponding author (Yes/No) | |

| 8. Does the guideline include a flowchart/algorithm? | |

| Identification | |

| 1. Male, female, both male and female | |

| 2. Individuals who have sustained fragility fractures | a. Age threshold |

| b. Fracture types evaluated | |

| c. Other comments relating to secondary fracture prevention | |

| 3. Individuals taking medicines to manage other conditions which are associated with bone loss and/or increased fracture risk:[10] | a. Androgen deprivation therapy |

| b. Anticoagulants | |

| c. Anticonvulsants | |

| d. Aromatase inhibitors | |

| e. Calcineurin inhibitors | |

| f. Glucocorticoids | |

| g. Medroxyprogesterone acetate | |

| h. Proton pump inhibitors | |

| i. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | |

| j. Thiazolidinediones | |

| k. Other medicines | |

| 4. Conditions associated with bone loss and/or increased fracture risk:[10] | a. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| b. Diabetes | |

| c. Diseases of malabsorption | |

| d. Dementia | |

| e. Rheumatoid arthritis | |

| f. HIV | |

| g. Multiple myeloma | |

| h. Untreated/uncontrolled hyperthyroidism | |

| i. Other conditions | |

| 5. Other risk factors | a. Age 70 years or over |

| b. Early menopause | |

| c. Excessive alcohol intake | |

| e. Family history | |

| f. Height loss | |

| g. Low body mass index/weight | |

| h. Prolonged immobility | |

| i. Smoking | |

| j. Other risk factors | |

| k. Other comments on identification | |

| Investigation | |

| 1. BMD testing, if available | |

| 2. Fracture risk calculators | a. FRAX® |

| b. Garvan | |

| c. IOF 1-minute test | |

| d. KKOS | |

| e. OSTA | |

| f. MORES | |

| g. QFracture | |

| h. SCORE | |

| 3. Vertebral fracture assessment by X-Ray or DXA | |

| 4. Falls risk assessment | |

| 5. Blood biochemistry | a. Alkaline phosphatase |

| b. Calcium | |

| c. Creatinine | |

| d. Osteocalcin | |

| e. uNTX | |

| g. P1NP | |

| h. PTH | |

| i. Vitamin D | |

| j. Other assays | |

| 6. Referral to specialist | |

| Information | |

| 1. Information on calcium intake | |

| 2. Information relating to sun exposure | |

| 3. Information relating to osteoporosis and fracture risk | |

| 4. Information relating to exercise | |

| 5. Other information | |

| Intervention | |

| 1. Which patient groups are indicated for treatment? | a. Hip fracture |

| b. Vertebral fracture | |

| c. Non-hip, non-vertebral fracture | |

| d. BMD T-Score ≤ –2.5 SD | |

| e. Osteopenia + FRAX ≥3% Hip or ≥ 20% MOF | |

| f. Osteopenia + RFs or eligible by OSTA or SCORE | |

| g. Osteopenia + ≥10 years postmenopausal | |

| h. FRAX or Garvan ≥3% Hip or ≥ 20% MOF | |

| i. Eligible by OSTA, MORES or SCORE | |

| j. QCT <80 mg/cm3 | |

| k. Height loss >4 cm | |

| l. Androgen deprivation therapy use | |

| m. Aromatase inhibitor use | |

| n. Glucocorticoid use | |

| 2. Which treatment options are recommended? | a. Bisphosphonates (oral, IV) |

| b. Calcium | |

| c. HRT | |

| d. Monoclonal antibodies (denosumab, romosozumab) | |

| e. Parathyroid hormone analogues (abaloparatide, teriparatide) | |

| f. Selective estrogen receptor modulators (raloxifene. tamoxifen. toremifene) | |

| g. Vitamin D | |

| h. Other treatment options | |

| 3. Are recommendations made on monitoring treatment? | |

| 4. Are recommendations made on treatment duration? | |

| 5. Are recommendations made on checking adherence with treatment? | |

| 6. Comments on side effects | |

| 7. Comments on referral to falls prevention programs | |

| 8. Comments relating to other interventions | |

| Integration | |

| 1. Are recommendations made to provide the patient with a long-term management plan? | |

| 2. Are recommendations made to provide the patient’s primary care provider with a long-term management plan? | |

| Quality | |

| 1. Does the guideline advocate audit of care provision against clinical care standards? | |

| 2. Does the guideline advocate healthcare providers maintain ongoing professional medical education relating to osteoporosis? | |

Appendix 2 Delphi Round 1 questionnaire toward consensus on clinical standards for osteoporosis

|

Domain 1: Notable findings from the 5IQ Comparative analysis of osteoporosis clinical guidelines from across the Asia Pacific region This domain of the questionnaire includes a series of open-ended questions which invite you to share your opinions on the most notable findings of the 5IQ analysis report. | ||

|---|---|---|

| 5IQ item | Question | Options |

| Identification | Considering the groups of individuals that the various guidelines recommend should be identified for bone health assessment, what are the most notable findings in the analysis? (You can indicate more than one) | [Free text] |

| Investigation | Considering the investigations that the various guidelines recommend should be undertaken, what are the most notable findings in the analysis? | [Free text] |

| Information | Considering the types of information that should be imparted to patients to engage them in their care, which are the most notable points identified by the analysis in your view? | [Free text] |

| Intervention | Considering the indications for treatment that are advocated, what are the most notable findings identified by the analysis in your view? | [Free text] |

| Considering the pharmacological treatments for specific patient groups identified by the analysis, what are the most notable findings in your view? | [Free text] | |

| Considering the findings of the analysis related to falls prevention, what are the most notable in your view? | [Free text] | |

| Integration | Considering how integration should occur between primary and secondary care, what are the most notable findings identified by the analysis in your view? | [Free text] |

| Quality | Considering the findings of the 5IQ Comparative analysis related to quality metrics, what are the most notable findings in your view? | [Free text] |

| Domain 2: How should the Framework be structured? | ||

| How do you envisage the Framework being structured? Would you like to have it as a simple list of standards or have several levels of attainment (i.e. Level 1, Level 2, Level 3)? | [Free text] | |

|

Domain 3: What clinical standards are required? This domain seeks your opinions on what specific aspects of care merit having a clinical standard. We invite you to rate the importance or not of having particular standards and invite you to add any comments as free text. | ||

| 5IQ item | Question | Options |

| Identification | How important is it to have a standard relating to identification of individuals with fragility fractures? |

Extremely important Very important Somewhat important Not so important Not at all important |

| How important is it to have a standard relating to identification of individuals with common risk factors for osteoporosis (e.g. age 70 years or over, early menopause, excessive alcohol intake, family history, height loss, low body mass index/weight, prolonged immobility, smoking)? |

Extremely important Very important Somewhat important Not so important Not at all important |

|

| How important is it to have a standard relating to identification of individuals who take medicines associated with bone loss and/or increased fracture risk? |

Extremely important Very important Somewhat important Not so important Not at all important |

|

| How important is it to have a standard relating to identification of individuals with conditions associated with bone loss and/or increased fracture risk? |

Extremely important Very important Somewhat important Not so important Not at all important |

|

| Investigation | How important is it to have a standard relating to biochemical investigations of individuals undergoing assessment? |

Extremely important Very important Somewhat important Not so important Not at all important |

| How important is it to have a standard relating to BMD testing of individuals undergoing assessment? |

Extremely important Very important Somewhat important Not so important Not at all important |

|

| How important is it to have a standard relating to use of risk assessment tools for individuals undergoing assessment? |

Extremely important Very important Somewhat important Not so important Not at all important |

|

| How important is it to have a standard relating to How important is it to have a standard relating to vertebral fracture assessment for individuals undergoing assessment? for individuals undergoing assessment? |