Abstract

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are associated with numerous physical and mental health issues in children and adults. The effect of ACEs on development of childhood obesity is less understood. This systematic review was undertaken to synthesize the quantitative research examining the relationship between ACEs and childhood obesity. PubMed, PsycInfo, and Web of Science were searched in July 2020; Rayyan was used to screen studies and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale was used to assess risk of bias. The search resulted in 6,966 studies screened at title/abstract and 168 at full-text level. Twenty-four studies met inclusion criteria. Study quality was moderate, with greatest risk of bias due to method of assessment of ACEs or sample attrition. Findings suggest ACEs are associated with childhood obesity. Girls may be more sensitive to obesity-related effects of ACEs than boys, sexual abuse appears to have a greater effect on childhood obesity than other ACEs, and co-occurrence of multiple ACEs may be associated with greater childhood obesity risk. Further, the effect of ACEs on development of childhood obesity may take 2–5 years to manifest. Considered collectively, findings suggest a need for greater attention to ACEs in the prevention and treatment of childhood obesity.

Keywords: adverse childhood experiences, obesity, pediatric obesity

Introduction

Nearly one-fifth of American children have obesity,1 yet effective solutions for the obesity epidemic are lacking. Prevention efforts from the past two decades have had limited impact on the rise of obesity among children.2 Traditional interventions targeting energy balance and individual health behavior change (e.g., caloric restriction, increased physical activity) have not substantially decreased the prevalence of obesity.3,4 Expert groups such as the National Collaborative for Childhood Obesity Research and National Institutes of Health have called for examining the contributions of a broader range of social and environmental risk factors.5–9 A better understanding of complex risk factors for obesity can inform targeted interventions, clinical practice, policy, and future research.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) are one potential risk factor for childhood obesity. ACEs are traumatic experiences that occur during childhood and have traditionally been defined as: physical, psychological, or sexual abuse; neglect; family member’s substance abuse, mental illness, or criminal behavior; intimate partner violence against female caregiver; and parent divorce/separation or death.10 Alarmingly, nearly half of children have experienced at least one ACE.11–14 ACEs exposure has been associated with cardiovascular disease, cancer, and other poor health outcomes in adulthood.10,15–21 ACEs’ effect on the development of obesity has been studied much less than risk factors related to individual health behavior.

ACEs may increase childhood obesity risk via multiple pathways of chronic or severe stress. Neuroendocrine and physiological effects of ACEs include hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysregulation, alterations in hormonal response to stressors, and appetite modifications with desire for highly palatable “comfort foods.” 22–24 ACEs are also associated with obesity-related behaviors, such poor impulse control,25 inadequate sleep,26,27 binge eating, and depression.22–24 Other co-occurring stressors in the household and neighborhood environment can further hinder a family’s ability to support healthy behaviors.

There have been several reviews on the relationship between ACEs and adult obesity.19,28–38 All have suggested an association. In contrast, the association between ACEs and childhood obesity is less understood, leading to calls for further research.15,16,20,21,28,39 Given that nearly 50% of children experience ACEs11–14,38 and 17% have obesity,40 a clearer understanding of the ACEs-childhood obesity relationship is warranted.

Two prior systematic reviews have examined the association between ACEs and childhood obesity. The first, published in 2014, focused only on maltreatment and included studies of adults and children; the meta-analysis led the authors to conclude that maltreatment was associated with obesity in adults but not children.15 The second, published in 2017, included only studies in which participants were <18 years and had exposure to at least two ACEs. Meta-analytic results suggested a positive association between ACEs and obesity in longitudinal studies, yet significant associations were found only in subsets of cross-sectional and case control studies, including those of youth >6–12 years and considering ACEs exposure occurring greater than two years ago.16 Despite the meaningful contributions of these reviews, results were unequivocal with both calling for more research. An updated review is warranted as several studies have been published since 2017. Further, past reviews were limited in scope, considering only maltreatment and exposure to at least two ACEs.

This systematic review was undertaken to synthesize the quantitative research examining the relationship between ACEs and childhood obesity. The primary aim was to examine whether ACEs are associated with obesity during childhood; an exploratory aim was to elucidate if and how the association differed by study methodology, sample demographics, ACE type, and ACE measurement. The hypothesis was that ACEs would be positively associated with childhood obesity. The overarching goal was to inform a clearer understanding of the ACEs-childhood obesity relationship. Ideally, results would support future research as well as inform clinical practice and policy focused on supporting the physical and psychosocial health of children who experience ACEs and obesity.

Methods

Protocol Registration and Reporting

This systematic review protocol was registered with PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (protocol ID: CRD42020210717).41 Study processes were guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement.42

Eligibility Criteria

Studies that examined the relationship between ACEs (exposure) and childhood obesity (outcome) were sought for inclusion. Inclusion criteria included: quantitative design (including but not limited to prospective cohort, retrospective cohort, cross-sectional, case-control); measure of ACEs (defined as physical, psychological, or sexual abuse; neglect; family member’s substance abuse, mental illness, or criminal behavior; intimate partner violence against female caregiver; and/or parent divorce/separation or death); measure of obesity (including but not limited to body mass index [BMI], BMI z-score, BMI percentile, waist circumference, and/or percent body fat); sample population 18 years or younger; published in peer-reviewed journal; and published in English. Exclusion criteria were qualitative design; no measure of ACEs; no measure of obesity; sample population older than 18 years; not peer-reviewed; or not published in English. Studies that combined ACEs with non-ACE stressors in a single cumulative measure were excluded. For example, a study that examined ACEs in combination with household socio-economic status and maternal stress would be excluded, given the inability to isolate ACEs’ effect from the other variables. Prior systematic reviews15,16 and the studies they included also were excluded, in order to synthesize the large amount of new evidence available.

Search

The search strategy was developed with guidance from a research librarian with expertise in systematic reviews. Search terms focused on ACEs, obesity, and childhood. PubMed, Web of Science, and CINAHL were searched on July 7, 2020. Full search strategies are presented in Supplementary File Figure S1.

Screening

Studies were imported to EndNote X8 for duplicate removal then into Rayyan web application43 for screening. Within Rayyan, each study was screened at each the title, abstract, and full text level by KS based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. If excluded, the reason for exclusion was documented. Reference lists of included studies were searched for potentially relevant studies, and if identified, imported into Rayyan for screening.

Data Extraction and Risk of Bias

Data from each study were extracted, including information on study design (cross-sectional, longitudinal), duration, and setting (city, country), as well as sample size, age, and characteristics (e.g., children attending Head Start, children with open child protective services cases). Measurement data extracted for ACEs included which specific ACEs were assessed, coding (summary score, none versus any, <2 versus ≥2, <4 versus ≥4), source (youth-report, parent-report, child protective services reports, medical chart review), and time points of measurement; for obesity, data extracted included source (youth-report, parent-report, objectively measured) and time points of measurement. Analytic method and results were extracted also. Risk of bias was assessed at the outcome level of each study, using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale.44 Data extraction and risk of bias assessment were performed by KS using Microsoft Excel.

Results

Study Selection

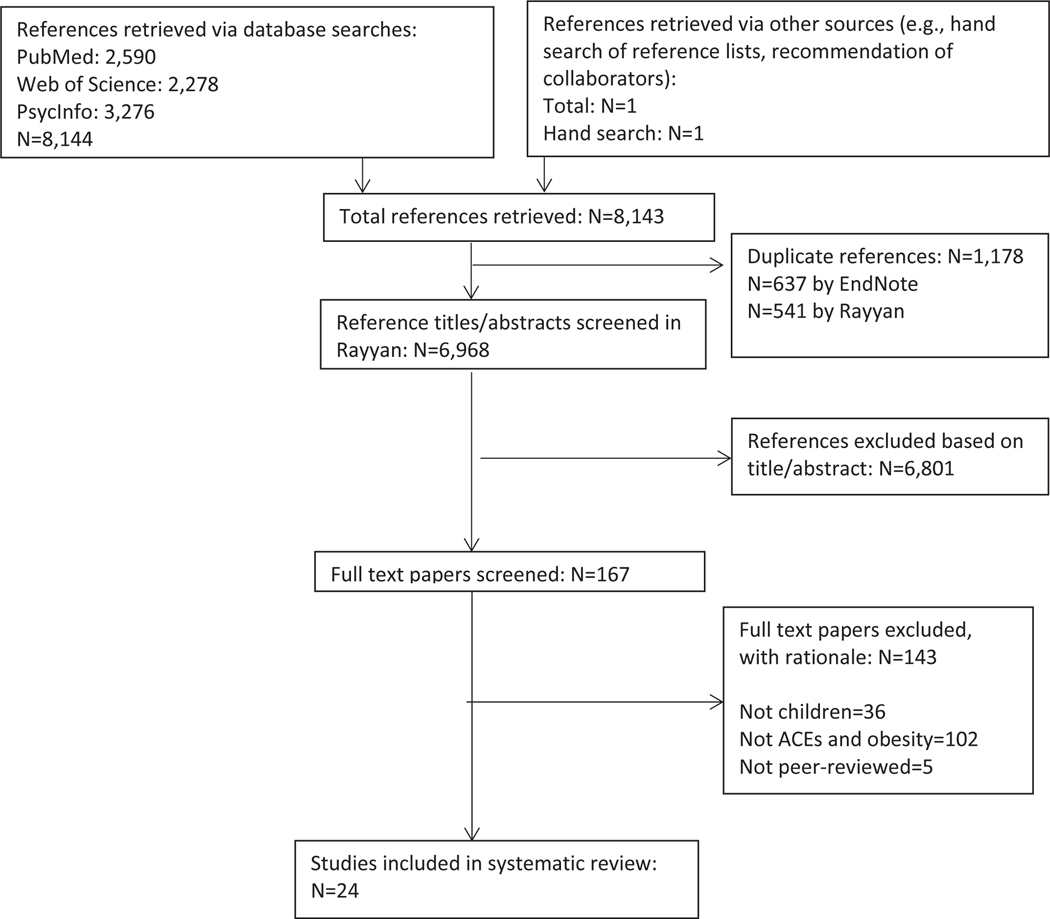

Figure 1 provides a summary of the search and study selection. The search resulted in 8,144 studies. After removal of duplicates, 6,966 studies were screened in Rayyan with 6,801 excluded at the title/abstract level and 143 excluded at the full-text level due to not examining the association between ACEs and obesity (n=102), sample population not children (n=36), or not being peer-reviewed (n=5). Twenty-four studies remained for inclusion, including 12 cross-sectional45–55 and 12 longitudinal.20,22,56–65

Figure 1.

Summary of the search

Risk of Bias

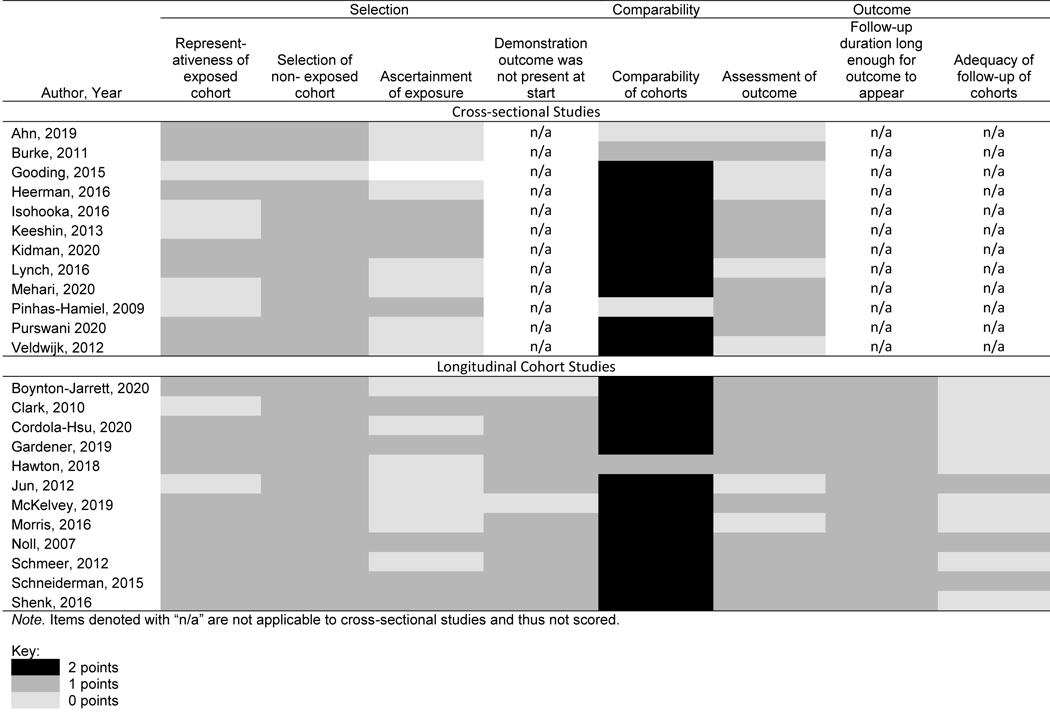

Results of risk of bias assessment by study design are presented in Table 1. Regarding selection of the cohort, most studies15,16,20,22,45–48,51,52,56,58–60,62–66 included individuals who were representative or somewhat representative of the population of interest (defined as youth who are at risk for or have experienced ACEs). Fewer studies22,49–51,54,57,59,64,65 used verifiable records or structured interviews to assess ACE exposure, with most relying on retrospective youth- or parent-report via survey.15,16,20,45–48,52,53,56,58,60–63,66 Most longitudinal studies assessed the outcome (obesity) at baseline.22,57–65 Regarding comparability, almost all studies15,16,20,22,46–53,56–60,62–66 controlled for important factors such as gender, age, race/ethnicity, or socioeconomic indicators during analyses. Pertaining to assessment of obesity, some studies entailed measurement of height and weight by a trained person20,22,46,49–51,53,54,56–60,63–65 whereas others used youth- or parent-report.45,47,48,52,61,62,66 For longitudinal studies, all had adequate follow-up duration to demonstrate change in adiposity (defined as >6 months) though many20,56–60,62,63,65 lost substantial percentages of the sample to follow-up. Considered collectively, study quality was moderate with greatest risk of bias either due to ACE assessment, which was often assessed via retrospective youth- or parent-report, or sample attrition in longitudinal studies.

Table 1.

Risk of bias of included cross-sectional and case-control studies, as assessed using Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. Items are scored with 0 points (greater risk of bias) or 1 point (less risk of bias), except ‘comparability of cohorts’ which is scored with 0 (greatest risk of bias), 1, or 2 points (least risk of bias). See key below.

|

Summary of Study Characteristics

Characteristics and results of individual studies are presented in Table 2a-2b. Twelve were cross-sectional45–55,66 and 12 were longitudinal.20,22,56–65 Although the search was not limited by year, 23 of the 24 were published since 2010, with the exception of two published in 200954 and 2007.22 Most were based in the USA; two were based in England,60,62 one in the Netherlands,66 one in Israel,54 one in Ireland,59 and one in Malawi.51 Sample size ranged from 14554 to 51,856.66 Some were sub-studies of larger investigations, such as the Fragile Families Study56,63 or Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children.60,62 Sample characteristics varied. Most involved a community-based sample, though others involved youth in substance use disorder or psychiatric treatment,57 youth obtaining care at an obesity clinic,54 youth with developmental delays,53 or youth receiving inpatient psychiatric care.49,50 Most included youth across multiple stages of child development, though two56,63 focused on younger youth (i.e., less than five years) and four studies47,60,65,66 focused on teens. Two22,65 included females only.

Table 2a.

Characteristics and results of included cross-sectional studies

| Author, Year | Study and Sample | ACEs Definition | ACEs Measure | Obesity Measure | Analytic Method and Results | Were ACEs Associated with Obesity? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-sectional Studies | ||||||

| Ahn, 2019 | N=42,193 10–17 years 2011/12 National Survey of Children’s Health Subsample USA |

Yes/no for each: 1) Extreme economic hardship 2) Parents divorced or separated 3) Lived with person with an alcohol/drug problem 4) Witnessed/victim of neighborhood violence 5) Lived with someone who was mentally ill/suicidal 6) Witnessed domestic violence 7) Parent incarcerated 8) Treated or judged unfairly due to race/ethnicity 9) Death of parent |

9 ACE summary score Parent-report via phone survey |

Weight category (healthy, obese); BMI Parent-report |

Pearson chi-square, path analysis 1.11±1.54 ACEs for healthy weight, 1.52±1.4 ACEs for obese, p<0.001 ACEs and BMI: β=0.05, p<0.01 |

Yes |

| Burke, 2011 | N=701 0–20 years Patients at urban pediatric clinic USA |

Yes/no for each: 1) Recurrent physical abuse 2) Recurrent emotional abuse 3) Contact sexual abuse 4) An alcohol/drug abuser in household 5) Incarcerated household member 6) Someone chronically depressed, mentally ill, institutionalized, suicidal 7) Mother treated violently 8) One or no parents 9) Emotional or physical neglect |

9 ACE summary score categorized as ≥4 and <4, and ≥1 and <1 Assessment via clinical care |

Weight category (healthy, overweight/ obese) Assessment via clinical care |

Multivariate logistic regression ≥1 ACE and obesity: OR 1.1, p=0.65 ≥4 ACEs and obesity: OR 2.0, p=0.02 |

Yes, but only ≥4 |

| Gooding, 2015 | N=147 13–17 years USA |

Yes/no for each: 1) Physical abuse 2) Sexual abuse 3) Emotional abuse 4) Domestic violence |

Each ACE individually yes/no; abuse severity score based on abuse ACEs only; any abuse yes/no Youth-report for experiencing ever |

BMI z Youth-report |

Multivariate linear regression Physical abuse and BMIz: β=0.52, p=0.01 Sexual abuse and BMIz: β=0.16, p=0.36 Emotional abuse and BMIz: β=0.36, p=0.14 Any abuse and BMIz: β=0.20, p=0.22 Domestic violence and BMIz: β=0.85, p<0.01 Abuse severity and BMIz: β=0.018, p=0.11 |

Yes, but only physical abuse and domestic violence |

| Heerman, 2016 | N=42,239 10–17 years 2011/12 National Survey of Children’s Health Subsample USA |

Yes/no or 4-point Likert for each: 1) Extreme economic hardship 2) Parents divorced or separated 3) Lived with person with an alcohol/drug problem 4) Witnessed/victim of neighborhood violence 5) Lived with someone who was mentally ill/suicidal 6) Witnessed domestic violence 7) Parent incarcerated 8) Treated or judged unfairly due to race/ethnicity 9) Death of parent |

9 ACE summary score categorized as ≥1 or <1, or ≥2 or <2 Parent-report via phone survey |

Weight category (healthy, overweight, obese) Parent-report |

Proportional odds survey regression ≥1 ACE and obesity: OR 1.3, p<0.001 ≥2 ACE and obesity: OR 1.8, p<0.001 |

Yes |

| Isohooka, 2016 | N=449 12–17 years Admitted to inpatient psychiatric unit Finland |

Yes/no for each: 1) Witnessed domestic violence 2) Physical abuse 3) Sexual abuse 4) Parent substance use problem 5) Parent psychiatric problem 6) Parent divorce 7) Parent death |

Each ACE individually yes/no Youth-report via clinical interview |

Weight category (under, healthy, overweight, obese) Objectively measured |

Multivariate logistic regression: Girls: Sexual abuse and obesity: OR 2.6, p=0.038 Boys: NS, data not shown |

Yes, but only for girls and only for sexual abuse |

| Keeshin, 2013 | N=1,434 3–20 years Admitted to inpatient psychiatric unit USA |

Yes/no for each: 1) Physical abuse 2) Sexual abuse |

Each type of abuse yes/no Parent- or youth-reported as documented in chart |

Weight category (healthy, overweight/obese, severe obesity) Objectively measured |

Multinomial Logistic Regression Sexual abuse and overweight/obesity: OR 1.41, 95%CI 1.01–1.98 Physical abuse and overweight/obesity: OR 0.95, 95%CI 0.68–1.33 Severe obesity: NS, data not shown |

Yes, but only sexual abuse |

| Kidman, 2020 | N=2,089 10–16 years Extension of Malawi Longitudinal Study of Families and Health Malawi |

Yes/no for each: 1) Emotional neglect 2) Emotional abuse 3) Physical neglect 4) Physical abuse 5) Sexual abuse 6) Substance abuse by householder 7) Mental health issues in householder 8) Incarcerated household member 9) Domestic violence 10) Parents dead or divorced 11) Peer bullying 12) Community violence 13) Collective violence |

13 ACE summary score Youth-report via in-person interview |

Weight category (obese, non-obese) Objectively measured |

Multivariate logistic regression Boys: NS, data not shown Girls: ACEs and obesity: OR 1.08, 95%CI 1.01–1.15 Top vs bottom quintile of ACE score and obesity: OR 1.94, 95% CI 1.19–3.16 |

Yes, but only for girls |

| Lynch, 2016 | N=43,864 10–17 years 2011/12 National Survey of Children’s Health subsample USA |

Yes/no or 4-point Likert for each: 1) Extreme economic hardship 2) Parents divorced or separated 3) Lived with person with an alcohol/drug problem 4) Witnessed/victim of neighborhood violence 5) Lived with someone who was mentally ill/suicidal 6) Witnessed domestic violence 7) Parent incarcerated 8) Treated or judged unfairly due to race/ethnicity 9) Death of parent |

9 ACE summary score categorized as 0, 1, and ≥2; each ACE individually Parent-report via phone interview |

Weight category (healthy, overweight, obese) Parent-report |

>=2 ACEs and obesity: OR 1.21, 95%CI 1.02–1.44 Parent death and obesity: OR 1.59, 95%CI 1.18–2.15 Other ACEs: NS, data not shown |

Yes, both collectively and individually for parent death |

| Mehari, 2020 | N=180 2–7 years Neurodevelopmental delays USA |

Yes/no for each: 1) Parent divorce/separation 2) Household substance use 3) Incarcerated Family member 4) Witnessing domestic violence 5) Household member w/ mental illness 6) Death of parent 7) Witnessing domestic violence 8) Experiencing discrimination |

Any ACE yes/no Parent-report via survey |

Weight category (under, healthy, overweight, obese) Objectively measured |

Hierarchical linear regression ACEs and obesity: β 0.08, p=0.31 |

No |

| Pinhas-Hamiel, 2009 | N=145 4–18 years Referred to obesity clinic Israel |

Yes/no for each: 1) Penetrative sexual abuse |

Sexual abuse yes/no Youth-report via clinical intake interview |

BMIz Objectively measured |

BMIz for abused versus non-abused: 4.76±1.34 vs. 3.39±1.28, p=0.02 |

Yes |

| Purswani, 2020 | N=948 2–20 years Attending general pediatrics clinic USA |

Yes/no for: 1) “10 ACEs described in the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study” [not listed] 2) Living in a foster care 3) Being bullied 4) Death of a caregiver 5) Deportation or migration 6) Discrimination 7) Experiencing a life-threatening illness or invasive medical procedure 8) Exposure to community or school violence |

18 ACE summary score, categorized as 0 or ≥1, or <2 or ≥2 Parent-report via survey |

Weight category (overweight/obese, healthy) | >=1 ACE and overweight/obesity: OR 1.03, 95%CI 0.68–1.55, p=0.89 >=2 ACEs and obesity: OR 1.01, 95%CI 0.70–1.46, p=0.97 |

No |

| Veldwijk, 2012 | N=51,856 13–16 years Netherlands |

Yes/no for each: 1) Physical abuse 2) Sexual abuse 3) Mental abuse |

Physical abuse yes/no, sexual abuse yes/no, mental abuse yes/no Youth-report via survey |

Weight category (under, healthy, overweight, obese) Youth-report |

Generalized estimating equations Boys: Physical abuse and obesity: OR 1.77, 95% CI 1.29–2.42 Sexual abuse and obesity: OR 2.49, 95% CI 1.82–3.42 Mental abuse and obesity: OR 2.98, 95%CI 2.32–3.83 Girls: Mental abuse and obesity: OR 5.07, 95%CI 3.84–6.70 |

Yes, but physical/sexual/ mental for boys and mental only for girls |

Note. 95%CI=95% confidence interval, ACE=adverse childhood experience, BMI=body mass index, NS=not significant, OR=odds ratio, USA=United States of America

Table 2b.

Characteristics and results of included longitudinal cohort studies

| Author, Year | Study and Sample | ACEs Definition | ACEs Measure | Obesity Measure | Analytic Method and Results | Were ACEs Associated with Obesity? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boynton-Jarrett, 2020 | N=1,595 0 years old at baseline Fragile Families Study subsample 5 year duration USA |

Intimate partner violence (IPV) to mother | 4 IPV summary: no IPV, early IPV (at 0 or 1 years), late IPV (at 3 or 5 years), chronic (both early and late) Maternal-report via survey at age 0, 1, 3, and 5 years |

Weight category (obese, non-obese) at age 3 and 5 Objectively measured |

Multivariate regression Girls: Chronic IPV and obesity: OR 2.21, 95%CI 1.30–3.75 Early and late PIV: NS, data not shown Boys: NS, data not shown |

Yes, but only if chronic IPV and only for girls |

| Clark, 2010 | N=668 12–18 years old at baseline 1 year duration Youth attending hospital-based substance use treatment or residential program, and community sample USA |

7 trauma classes: 1) no trauma 2) non-interpersonal trauma 3) witnessing violence 4) violence victimization 5) physical abuse 6) sexual abuse 7) rape |

7 trauma class summary Youth-report via in-person interview at baseline age |

Weight category (healthy, overweight/obese); BMI percentile at 1 year follow-up Objectively measured |

Multivariate regression Trauma class and overweight/obesity: X2 12.8, p<0.05 at baseline, X2 10.1, p=0.1 at 1 year Trauma class and BMI percentile: F 2.2, p<0.05 at baseline, F 1.2, p=0.30 at 1 year |

Yes, but only at baseline |

| Cordola-Hsu, 2020 | N=844 1 month old at baseline Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development subsample 15 year duration USA |

Mean score of: 1) Maternal depression per Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) |

Mean depression score Maternal-report via survey at age 6, 15, 24, 36, and 54 months, and 1st, 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 6th grade |

BMIz at age 15 Objectively measured |

Mediation analyses Boys: Maternal depression and BMIz: Direct effect=0.21, 95%CI 0.0052–0.037 Girls: Maternal depression and BMIz: Indirect effect=0.0038 (via child depression), 95%CI 0.0008–0.0087 |

Yes, but directly for boys and indirectly for girls |

| Gardener, 2019 | N=6,942 9 years old at baseline Growing Up in Ireland subsample 4 year duration Ireland |

Yes/no for each: 1) Divorce 2) Parent in prison 3) Parent with drug/alcohol abuse 4) Parent with mental health disorder 5) Death of a parent 6) Death of a close family member 7) Death of a close friend 8) Moving house 9) Moving country 10) Stay in foster home 11) Serious illness of child 12) Serious illness of family member 13) Conflict between parents 14) Other disturbing event |

Any ACE (defined as #1–4) yes/no, any adversity (defined as #1–14) yes/no Parent-report via home interview at age 9 years |

Weight category (healthy, overweight, obese); BMIz at age 13 Objectively measured |

Multivariate regression Adversity and obesity: OR 1.74, 95%CI 1.09–2.73 Adversity and obesity incidence: IRR 1.56, 95%CI 1.19–2.05 Adversity and BMIz: 0.101, 95%CI −0.003–0.204) ACEs and BMIz: 0.202, 95%CI 0.100–0.303 |

Yes, but more consistently for the comprehensive adversity measure |

| Hawton, 2018 | N=4,205 13 years old at baseline Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children subsample 3 and 5 years duration England |

Yes/no for each: 1) Physical abuse 2) Sexual abuse 3) Emotional abuse |

Each type of abuse yes/no Parent-report via survey at @ age 18, 30, 42, 57, 69, 81, and 103 months (sexual abuse) and 8, 21, 33, 47, 61, 73, 110, and 134 months (physical and emotional abuse) |

Weight category (non-obese, obese) and BMI at age 13, 16, and 18 Objectively measured |

Multivariate regression, mixed effects growth model Each type of abuse and obesity at 13 or 16 years: NS, data not shown Physical abuse and BMIz at 18 years: β −0.004, 95%CI −0.006 - −0.001 Emotional abuse and BMIz at 18 years: β−0.002, 95%CI −0.004 - −0.001 Sexual abuse and BMIz at 18 years: NS, data not shown |

Yes, but only physical and emotional abuse and only at last follow-up |

| Jun, 2012 | N=10,997 9–14 years at baseline Growing Up Today Study subsample 6–11 year duration USA |

Yes/no for: 1) Domestic violence (DV) |

No DV, early DV (age 0–5), late DV (age 6–11) Maternal-report via survey |

BMI at ages 12–20 Youth-report |

Growth mixture modelling Boys: DV and healthy to obese: NS; data not shown DV and consistently overweight: OR 1.5, 95%CI 1.1–1.9 DV and consistently obese: OR 1.9, 95%CI 1.1–3.4 for early DV, and OR 2.8, 95%CI 1.4–5.9 for late DV Girls: NS, data not shown |

Yes, but only for boys |

| McKelvey, 2019 | N=1,335 1 year at baseline 11 year duration USA |

Yes/no for each: 1) Emotional abuse/neglect 2) Physical abuse/neglect, 3) Sexual abuse 4) Domestic violence 5) Household substance abuse 6) Household mental illness 7) Parent separation or divorce 8) Incarcerated household member |

Summary score, categorized as 0, 1, 2, 3, ≥4 Parent-report via survey at age 1, 2, and 3 years |

Weight category (obese, non-obese) Objectively measured at age 11 |

Multivariate logistic regression 1, 2 or 3 ACEs and obesity: NS, data not shown ≥4 ACEs and obesity: OR 2.65, 95% CI 1.51–4.67 |

Yes, but only if ≥4 |

| Morris, 2016 |

N=7,201 0 years at baseline Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children subsample 17 year duration England |

Yes/no for each: 1) Parent death 2) Parent separation |

Parent death yes/no, parent separation yes/no Parent-report at age 8, 21, 33, and 47 months |

BMI Objectively measured or parent-report at age 4–17 |

Mixed-effects multi-level models Parent separation and BMI: 1.1, 95%CI 0.2–2.0 at age 4, but NS by age 9 |

Yes, but only separation and only before age 4 |

| Noll, 2007 |

N=163 6–16 years at baseline Female 19 year duration *Young adult portion of study not included in the current review USA |

Yes/no for each: 1) Sexual abuse |

Sexual abuse yes/no CPS records at baseline |

Weight category (obese, non-obese) Objectively measured |

Multivariate logistic regression Sexual abuse and obesity: OR 2.03, 95%CI 0.54–4.60 |

No |

| Schmeer, 2012 | N=1,595 3 years old at baseline Fragile Families Study subsample 2 year duration USA |

Yes/no: 1) Parent separation |

Parent separation yes/no Maternal-report at age 3 and 5 years |

Weight category (health, overweight/obese) and BMI at 3 and 5 years Objectively measured |

Multivariate regression Parent separation and BMI: β 0.49±0.19, p<0.05 Parent separation and overweight/obese: OR 1.83±0.55, p<0.05 |

Yes |

| Schneiderman, 2015 | N=454 9–12 years old at baseline 4.5 year duration USA |

Yes/no for each: 1) Sexual abuse 2) Physical abuse 3) Emotional abuse (but no physical or sexual abuse) 4) Neglect (but no physical, sexual or emotional abuse) |

Each type of abuse yes/no CPS records at baseline |

BMI %tile Objectively measured |

Growth models Boys: NS, data not shown Girls: Physical abuse and BMI %tile: NS, data not shown Sexual abuse and BMI %tile: Less favorable BMI trajectory for obesity-risk Neglect and BMI %tile: Less favorable BMI trajectory for obesity-risk |

Yes, but only for girls and only for sexual abuse and neglect |

| Shenk, 2016 | N=514 14–17 years at baseline Female 5 year duration USA |

Yes/no for each: 1) Physical abuse 2) Sexual abuse 3) Neglect |

Any maltreatment yes/no Youth-report via interview at annual study visits; CPS records |

Weight category (obese, non-obese) Objectively measured |

Generalized linear models Abuse and obesity: RR 1.47, 95%CI 1.03–2.08 |

Yes |

Note. 95%CI=95% confidence interval, ACE=adverse childhood experience, BMI=body mass index, CPS = Child Protective Services, NS=not significant, OR=odds ratio, USA=United States of America, %tile=Percentile

Assessment of ACEs and obesity varied across studies. Many considered lists of seven or more ACEs, which were then analyzed in one or more ways including individually yes/no,47,49,52 as a summary score,45,47,51,57 categorized at 0 versus any,20,46–48,52,53,55,59 ≥2,20,48,52,55 and/or ≥4.20,46 Other studies focused on maltreatment-related ACEs (physical, sexual, and/or emotional abuse and neglect), which were examined individually (each type of maltreatment yes/no)50,60,64,66 or collectively (no maltreatment versus any type of maltreatment).65 Some considered only one particular ACE such as sexual abuse,22,54 parent death,62 parent divorce/separation,62,63 mental illness of the parent,58 or intimate partner violence against female caregiver.56,61 Studies also varied in method of ACEs report. Most assessed ACEs via parent-report,20,45,48,50,52,53,56,58–63 though others used youth-report (particularly with adolescents),47,49,51,54,57,66 child protective service records,22,64 or a combination of youth-report and child protective services records.65 Three of 12 longitudinal studies assessed ACEs only once at baseline,57,59,64 with most others assessing ACEs at multiple points throughout the study.20,56,58,60,62,63,65 With respect to obesity, 18 of the 24 studies20,22,46,49–51,53,54,56–65 used objective measurement of height and weight, with the others using youth- or parent-report. Of the longitudinal studies, all except three20,58,59 assessed obesity multiple times throughout the study period.

Study synthesis

Collectively, 11 of 12 longitudinal20,56–65 and 10 of 12 cross-sectional studies45–52,54 found that ACEs were associated with childhood obesity. However, findings were not completely consistent within or across studies. Differences existed by type of ACE, across populations, and by ACE measurement. For example, studies found an association only for physical and emotional abuse (not sexual abuse),60 only for sexual abuse and neglect (not physical or emotional abuse),61 only for sexual abuse (not physical abuse50 or other ACEs),49 only for physical abuse and domestic violence (not sexual or emotional abuse),47 or only for parent divorces/separation.62 Across populations, associations were found only for girls,49,51,56,64 only for boys,58,61 or only with obesity before age 4.62 In terms of measurement, studies found associations only for ACE exposure that occurred between 0–5 years56 or entailed ≥4 ACEs.20,46 One longitudinal study60 found that an association existed only after five years.

Three studies did not identify a relationship between ACEs and childhood obesity. Of the three, one was longitudinal and assessed one ACE (substantiated sexual abuse). Of note, the study included participants through adulthood and although the adult portion of the study was not included in this review, a relationship between sexual abuse and adult obesity was observed.22 The second was a cross-sectional study which focused on 18 ACEs, categorized as 0 versus any and <2 versus ≥2, reported by parents during their child’s general pediatric care.55 The third53 was a cross-sectional study that found a relationship between parent-reported ACEs (any of eight ACEs yes/no) and childhood obesity only when children lived in poverty, with poverty operationalized as whether a child’s home Census block group fell above versus below the Federal Poverty Threshold for a family of four. The study included youth with neurodevelopmental delays presenting for treatment, a population meaningfully different than others studied.

Considered collectively, there were no clear differences between the 21 studies that did and the three that did not find an association between ACEs and obesity in childhood. Yet among the three studies that did not, there were some similarities and differences. All three measured obesity objectively and were based in the United States. No notable differences existed by risk of bias. Two used parent-reported measure of multiple ACEs summarized and categorized dichotomously,53,55 while one assessed only substantiated sexual abuse.22 One involved a unique population of children with neurodevelopment delays53 and one was longitudinal.22 However differences among the three studies mirror differences among the 21 studies that did find an association; thus, no clear conclusions can be drawn about the contrary findings.

Discussion

Results of this systematic review suggest that ACEs increase the risk for the development of obesity in childhood. This conclusion is consistent with one16 of the two15,16 prior reviews focused on childhood obesity published in the past decade as well as all prior reviews focused on adult obesity.19,28–38 Findings align with the theory that ACEs may interfere with psychosocial and neuroendocrine development, leading to obesity because of associated impairment in self-regulation, appetite, psychopathology, and disruptions within family microsystems.22–27,45,46,68

Results of this systematic review support the conclusion that the ACEs-childhood obesity relationship is complex and nuanced. Studies demonstrated conflicting findings for individual ACEs and, at times, found associations only for certain subgroups of individuals. The substantial variation in study design, approach to categorizing ACEs, methods of measuring of ACEs and obesity, and sample characteristics, prohibit drawing definitive conclusions about variability in the association. Considered collectively, however, the evidence suggests that girls may be more sensitive to obesity-related effects of ACEs than boys, sexual abuse may have a greater effect on obesity than other ACEs, and that experiencing multiple ACEs appears to be associated with greater risk for obesity. Further, while ACEs and childhood obesity are associated, obesity-related effects of ACEs may take at least two years to materialize.

Results must be considered within the context of limitations of included studies. Half of studies were cross-sectional, 23 used only one method of assessing ACEs, and six assessed obesity via youth-report rather than objective measurement. Many longitudinal studies experienced substantial attrition. Given that randomized studies of ACEs are not possible, observational studies must be used to explore ACEs’ association with childhood obesity. Rigorous methods used by certain included studies, such as employing multimethod assessment of ACEs,65 examining obesity trends over a long period of time,20,22,58,61,62 or including large samples45,48,52,59–62,66 are particularly well-suited to advancing understanding of how ACEs impact obesity during childhood.

Findings align with the broader literature about potential effects of ACEs on physical health. Apparent gender disparities may by rooted in cognitive and hormonal differences or girls’ relational sensitivity that intensifies the effects of ACEs, although this awaits further study.67 In addition, findings related to sexual abuse may reflect unique aspects of sexual abuse trauma, including shame, disparate perpetration by non-family members, and disproportionate victimization by girls.68–70 However caution is warranted in interpreting differences between types of ACEs, given the small number of studies, countervailing evidence suggesting similar effects of sexual abuse and other ACEs, methodological difficulties in isolating sexual abuse, and longitudinal research suggesting no association between sexual abuse and obesity during childhood.22,71 Dose-response and potential lag effects both lend support for ACEs’ theoretical effects on obesity; taken together they may suggest that obesity is a relatively downstream consequence of ACEs, occurring when exposures and proximal effects accumulate.

Studies included in this systematic review used a variety of definitions of ACEs. Such variation reflects the inherent complexity of ACEs as a phenomena, but also leads to challenges with operationalizing and documenting the effects of ACEs on obesity.38,65,72–76 Diverse ACEs such as sexual abuse, parent divorce/separation, and parent incarceration have similarity in being threating experiences but also have differences in both precipitating factors and sequelae. The common measurement of ACEs by summary score may not accurately account for the fact that different ACEs may lead to a different level of physiological and psychosocial burden.73 Moreover, individual ACEs have significant within-type variability in severity, chronicity, and co-occurrence. Timing (e.g., developmental stage) and duration (e.g., one time versus ongoing) of ACEs may have important implications for ACEs’ effects also. For example, parent mental illness measured is often measured as a dichotomous exposure; yet a one-time bout of paternal depression may not have the same effect on a child as their mother experiencing chronic schizophrenia. Methodological issues such as variation in the use of assessment tools, differences in instrument wording, and lack of psychometric validation of some measures impede understanding of the effect of ACEs on excess body weight in some studies.72,73

Most research has focused on ACEs within the family or home environment. However, experiences in the neighborhood also should be considered ACEs as well. Neighborhood-level ACEs may include individual-level experiences that happen in one’s neighborhood, such as witnessing violent crime when walking home from school, or neighborhood-level characteristics, such as living in a community that is perceived to be unsafe.39,77–79 Similar to family-level ACEs, neighborhood-level ACEs can overwhelm a child’s coping skills, violate their sense of safety, and may be associated with increased risk some chronic health conditions.39 A focus on neighborhood-level factors intersects naturally with the field of obesity, given extensive evidence documenting the potential effects of unhealthy neighborhood conditions (e.g., lack of greenspace, limited fresh foods) on obesity risk.80–84 Research that disentangles how neighborhood factors relates to both ACEs and obesity can inform efforts to reduce obesity risk at higher levels of the ecological model. In particular, studies harnessing large data sets to capture detailed information about household-level ACEs and neighborhood environment would advance understanding of the ACEs-childhood obesity relationship.

ACEs in this review were measured during childhood by youth-report, parent-report, and medical and child protective services records. This differs from much research focused on ACEs and adult obesity, which often rely on an adult’s self-report of ACEs experienced many years prior. Retrospective measurement of ACEs in adults likely does not fully capture childhood adversity; an adult’s memories about ACEs can be hindered by social desirability, current state of physical and mental health, and errors in recall (particularly for highly traumatic events).75,76 Children’s retrospective recall is of course subject to concern also; it is unclear how accuracy of asking an adolescent to report events in early childhood compares to asking an adult to report events in early childhood. The reliability of youth-report likely varies by age, recency, and length of the period studied, and ability to supplement youth-report with other informants/sources.85–88 That said, past studies have generally suggested higher detection of ACEs based on youth-report than parent-report or child protective service records.89

Future research is needed to compare methods of ACEs reporting in children.85–88 Research using multiple methods to verify ACE exposure (such as combining child protective services records with parent-report) can provide more accurate ACE data and, thus, may be particularly promising approaches for future studies.65 Such considerations are particularly important in obesity research when height and weight are self-reported, because retrospectively reported ACEs may be more strongly associated with subjectively-reported health outcomes.75

Findings of this systematic review indicate that childhood obesity reduction efforts would benefit from a greater focus on ACEs. Commonly, ACEs interventions focus on ensuring child safety, implementing trauma-informed practices, and addressing mental health effects of ACEs; in contrast, obesity interventions traditionally focus on nutrition, physical activity, and other health behaviors. Thus there exists untapped potential for integration of ACEs- and obesity-focused interventions. Given the high prevalence of ACEs11–14 and results of this systematic review suggesting that childhood obesity may be rooted in ACEs, treating obesity may require trauma-informed approaches more often that is currently recognized.23,31 Inequities in access to obesity treatment and potential differences in ACEs-obesity associations by SES53 suggest trauma-informed approaches may be particularly necessary in populations with low socio-economic status. Further, ACEs-associated psychopathology may limit ability to effectively participate in obesity interventions and necessitate targeted approaches to engaging youth who experienced ACEs in weight management. For example, access to bariatric surgery may be more challenging for youth who experience ACEs, given the complex and lengthy preoperative assessment process and requirement of psychiatric stability prior to surgery.90 Similarly, efforts to promote the well-being of youth who experience ACEs may benefit from a greater focus on health promotion and obesity-prevention behaviors.23,31 Certain behaviors associated with obesity, such as binge eating, may be rooted in trauma.33 Collaborations amongst teams with expertise in child welfare, trauma-informed practices, health behavior change, and obesity may be particularly fruitful for addressing ACEs-obesity associations. Timely efforts for addressing ACEs’ effects and obesity risk during childhood can help reduce the health disparities that result in adulthood for individuals who experience ACEs.

This systematic review has limitations. Despite best efforts, the search may have missed studies due the use of one screener or the search strategy. More specifically, the search strategy may have been more reliable at identifying studies explicitly using an ACEs framework rather than more focused studies (e.g., studies focused on parent divorce/separation). Relevant studies that were published in a language other than English or that did not go through peer-review may have been omitted. In addition, conclusions of this review are limited by risk of bias in included studies; primarily, ACEs were measured using a single method in all except one study, half of studies were cross-sectional, six studies used non-objective measures of obesity, and many longitudinal studies experienced attrition.

These limitations are mitigated by several strengths. These include adherence to established protocols for rigor, inclusion of studies over several decades, and no limitation on publication year of eligible studies. In addition, the decision to include studies not included in prior meta-analyses, as well as the use of multiple, complementary databases to identify articles considered for inclusion, allow for a high degree of confidence in the conclusions.

The past several years have witnessed growing attention to the role of ACEs in the development of obesity in children. This systematic review of quantitative research suggests that ACEs are associated with obesity during childhood, though the association is not consistent across ACEs or populations. The effect also appears to be delayed over several years, suggesting that maladaptive coping strategies, such as overeating, may be necessary for the development of excess body weight. With greater understanding of the effect of ACEs on childhood obesity, research, clinical practice, and policy can be tailored to support the safety, well-being, and long-term health of youth who experience ACEs and obesity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This research was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K23HD101554; PI: Schroeder) and National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (K01MD015326; PI: Schuler) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the NIH. Dr. Sarwer’s work was supported by grant funding from the National Institutes of Health (National Institute for Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Disease R01 DK108628 and National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research R01 DE026603) as well as PA CURE Funds from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

Abbreviations:

- ACEs

adverse childhood experiences

- BMI

body mass index

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: Dr. Sarwer discloses consulting relationships with Ethicon and NovoNordisk.

References

- 1.Ogden CL. Prevalence of Obesity Among Youths by Household Income and Education Level of Head of Household—United States 2011–2014. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2018;67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown T, Moore THM, Hooper L, et al. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al‐Khudairy L, Loveman E, Colquitt JL, et al. Diet, physical activity and behavioural interventions for the treatment of overweight or obese adolescents aged 12 to 17 years. The Cochrane Library. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mead E, Brown T, Rees K, et al. Diet, physical activity and behavioural interventions for the treatment of overweight or obese children from the age of 6 to 11 years. The Cochrane Library. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.NIH Obesity Research Task Force. Strategic Plan for NIH Obesity Research. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell MK. Biological, environmental, and social influences on childhood obesity. Pediatric research. 2016;79(1–2):205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baranowski T, Motil KJ, Moreno JP. Behavioral Research Agenda in a Multietiological Approach to Child Obesity Prevention. Childhood Obesity. 2019;15(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall KD, Guyenet SJ, Leibel RL. The carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity is difficult to reconcile with current evidence. JAMA internal medicine. 2018;178(8):1103–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McAllister EJ, Dhurandhar NV, Keith SW, et al. Ten putative contributors to the obesity epidemic. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition. 2009;49(10):868–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;14(4):245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bethell C, Davis M, Gombojav N, Stumbo S, Powers K. Issue Brief: A national and across state profile on adverse childhood experiences among children and possibilities to heal and thrive. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health;2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bellis MA, Hughes K, Leckenby N, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and associations with health-harming behaviours in young adults: surveys in eight eastern European countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2014;92:641–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bellis MA, Hughes K, Leckenby N, Perkins C, Lowey H. National household survey of adverse childhood experiences and their relationship with resilience to health-harming behaviors in England. BMC Medicine. 2014;12(1):72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soares ALG, Howe LD, Matijasevich A, Wehrmeister FC, Menezes AMB, Gonçalves H. Adverse childhood experiences: Prevalence and related factors in adolescents of a Brazilian birth cohort. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2016;51:21–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Danese A, Tan M. Childhood maltreatment and obesity: systematic review and meta-analysis. Molecular psychiatry. 2014;19(5):544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elsenburg LK, van Wijk KJE, Liefbroer AC, Smidt N. Accumulation of adverse childhood events and overweight in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity. 2017;25(5):820–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS medicine. 2012;9(11):e1001349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williamson DF, Thompson TJ, Anda RF, Dietz WH, Felitti V. Body weight and obesity in adults and self-reported abuse in childhood. International Journal of Obesity. 2002;26(8):1075–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hughes K, Bellis MA, Hardcastle KA, et al. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(8):e356–e366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKelvey LM, Saccente JE, Swindle TM. Adverse Childhood Experiences in Infancy and Toddlerhood Predict Obesity and Health Outcomes in Middle Childhood. Vol 15 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suglia SF, Koenen KC, Boynton-Jarrett R, et al. Childhood and Adolescent Adversity and Cardiometabolic Outcomes: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137(5):e15–e28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noll JG, Zeller MH, Trickett PK, Putnam FW. Obesity risk for female victims of childhood sexual abuse: a prospective study. Pediatrics. 2007;120(1):e61–e67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mason SM, Austin SB, Bakalar JL, et al. Child maltreatment’s heavy toll: the need for trauma-informed obesity prevention. American journal of preventive medicine. 2016;50(5):646–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peugh J, Reiter-Purtill J, Becnel JN, et al. Child Maltreatment and the Adolescent Patient With Severe Obesity: Implications for Clinical Care. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2015;40(7):640–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shin SH, McDonald SE, Conley D. Profiles of adverse childhood experiences and impulsivity. Child abuse & neglect. 2018;85:118–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kajeepeta S, Gelaye B, Jackson CL, Williams MA. Adverse childhood experiences are associated with adult sleep disorders: a systematic review. Sleep medicine. 2015;16(3):320–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chapman DP, Wheaton AG, Anda RF, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and sleep disturbances in adults. Sleep medicine. 2011;12(8):773–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hemmingsson E, Johansson K, Reynisdottir S. Effects of childhood abuse on adult obesity: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Obesity Reviews. 2014;15(11):882–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herzog JI, Schmahl C. Adverse childhood experiences and the consequences on neurobiological, psychosocial, and somatic conditions across the lifespan. Frontiers in psychiatry. 2018;9:420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kalmakis KA, Chandler GE. Health consequences of adverse childhood experiences: a systematic review. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners. 2015;27(8):457–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McDonnell CJ, Garbers SV. Adverse childhood experiences and obesity: Systematic review of behavioral interventions for women. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2018;10(4):387–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Midei A, Matthews K. Interpersonal violence in childhood as a risk factor for obesity: a systematic review of the literature and proposed pathways. Obesity reviews. 2011;12(5):e159–e172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palmisano GL, Innamorati M, Vanderlinden J. Life adverse experiences in relation with obesity and binge eating disorder: A systematic review. Journal of behavioral addictions. 2016;5(1):11–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ports KA, Holman DM, Guinn AS, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and the presence of cancer risk factors in adulthood: a scoping review of the literature from 2005 to 2015. Journal of pediatric nursing. 2019;44:81–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Su S, Jimenez MP, Roberts CT, Loucks EB. The role of adverse childhood experiences in cardiovascular disease risk: a review with emphasis on plausible mechanisms. Current cardiology reports. 2015;17(10):88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vamosi M, Heitmann B, Kyvik K. The relation between an adverse psychological and social environment in childhood and the development of adult obesity: a systematic literature review. Obesity Reviews. 2010;11(3):177–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiss DA, Brewerton TD. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Adult Obesity: A Systematic Review of Plausible Mechanisms and Meta-Analysis of Cross-Sectional Studies. Physiology & Behavior. 2020:112964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gustafson T, Sarwer D. Childhood sexual abuse and obesity. Obesity reviews. 2004;5(3):129–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cronholm PF, Forke CM, Wade R, et al. Adverse Childhood Experiences: Expanding the Concept of Adversity. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(3):354–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hales C, Seitz AE. Number of Youths Aged 2–19 Years and Adults Aged>= 20 Years with Obesity or Severe Obesity-National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2015–2016. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2018. 0149–2195. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Booth A, Clarke M, Dooley G, et al. The nuts and bolts of PROSPERO: an international prospective register of systematic reviews. Systematic reviews. 2012;1(1):2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS medicine. 2009;6(7):e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic reviews. 2016;5(1):210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2014; http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

- 45.Ahn S, Zhang H, Berlin KS, Levy M, Kabra R. Adverse childhood experiences and childhood obesity: A path analysis approach. Children’s Health Care. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burke NJ, Hellman JL, Scott BG, Weems CF, Carrion VG. The impact of adverse childhood experiences on an urban pediatric population. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2011;35(6):408–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gooding HC, Milliren C, Austin SB, Sheridan MA, McLaughlin KA. Exposure to violence in childhood is associated with higher body mass index in adolescence. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2015;50:151–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heerman WJ, Krishnaswami S, Barkin SL, McPheeters M. Adverse family experiences during childhood and adolescent obesity. Obesity. 2016;24(3):696–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Isohookana R, Marttunen M, Hakko H, Riipinen P, Riala K. The impact of adverse childhood experiences on obesity and unhealthy weight control behaviors among adolescents. Comprehensive psychiatry. 2016;71:17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Keeshin BR, Luebbe AM, Strawn JR, Saldaña SN, Wehry AM, DelBello MP. Sexual Abuse Is Associated with Obese Children and Adolescents Admitted for Psychiatric Hospitalization. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2013;163(1):154–159.e151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kidman R, Piccolo LR, Kohler HP. Adverse Childhood Experiences: Prevalence and Association With Adolescent Health in Malawi. Am J Prev Med. 2020;58(2):285–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lynch BA, Agunwamba A, Wilson PM, et al. Adverse family experiences and obesity in children and adolescents in the United States. Preventive Medicine: An International Journal Devoted to Practice and Theory. 2016;90:148–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mehari K, Iyengar SS, Berg KL, Gonzales JM, Bennett AE. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Obesity Among Young Children with Neurodevelopmental Delays. Matern Child Health J. 2020;24(8):1057–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pinhas-Hamiel O, Modan‐Moses D, Herman‐Raz M, Reichman B. Obesity in girls and penetrative sexual abuse in childhood. Acta paediatrica. 2009;98(1):144–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Purswani P, Marsicek SM, Amankwah EK. Association between cumulative exposure to adverse childhood experiences and childhood obesity. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(9):e0239940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Boynton-Jarrett R, Fargnoli J, Suglia SF, Zuckerman B, Wright RJ. Association between maternal intimate partner violence and incident obesity in preschool-aged children: results from the Fragile Families and Child Well-being Study. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2010;164(6):540–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Clark DB, Thatcher DL, Martin CS. Child abuse and other traumatic experiences, alcohol use disorders, and health problems in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2010;35(5):499–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cordola Hsu AR, Niu Z, Lei X, et al. Adolescents’ Depressive Symptom Experience Mediates the Impact of Long-Term Exposure to Maternal Depression Symptoms on Adolescents’ Body Mass Index. Ann Behav Med. 2020;54(7):510–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gardner R, Feely A, Layte R, Williams J, McGavock J. Adverse childhood experiences are associated with an increased risk of obesity in early adolescence: a population-based prospective cohort study. Pediatr Res. 2019;86(4):522–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hawton K, Norris T, Crawley E, Shield JPH. Is child abuse associated with adolescent obesity? A population cohort study. Childhood Obesity. 2018;14(2):106–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jun H-J, Corliss HL, Boynton-Jarrett R, Spiegelman D, Austin SB, Wright RJ. Growing up in a domestic violence environment: relationship with developmental trajectories of body mass index during adolescence into young adulthood. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2012;66(7):629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Morris TT, Northstone K, Howe LD. Examining the association between early life social adversity and BMI changes in childhood: A life course trajectory analysis. Pediatric Obesity. 2016;11(4):306–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schmeer KK. Family structure and obesity in early childhood. Social Science Research. 2012;41(4):820–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schneiderman JU, Negriff S, Peckins M, Mennen FE, Trickett PK. Body mass index trajectory throughout adolescence: a comparison of maltreated adolescents by maltreatment type to a community sample. Pediatric Obesity. 2015;10(4):296–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shenk CE, Noll JG, Peugh JL, Griffin AM, Bensman HE. Contamination in the prospective study of child maltreatment and female adolescent health. Journal of pediatric psychology. 2016;41(1):37–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Veldwijk J, Proper KI, Hoeven-Mulder HB, Bemelmans WJE. The prevalence of physical, sexual and mental abuse among adolescents and the association with BMI status. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zahn-Waxler C, Shirtcliff EA, Marceau K. Disorders of Childhood and Adolescence: Gender and Psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4(1):275–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Feiring C, Taska LS. The persistence of shame following sexual abuse: A longitudinal look at risk and recovery. Child maltreatment. 2005;10(4):337–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Finkelhor D, Shattuck A, Turner HA, Hamby SL. The lifetime prevalence of child sexual abuse and sexual assault assessed in late adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2014;55(3):329–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Finkelhor D, Vanderminden J, Turner H, Hamby S, Shattuck A. Child maltreatment rates assessed in a national household survey of caregivers and youth. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2014;38(9):1421–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vachon DD, Krueger RF, Rogosch FA, Cicchetti D. Assessment of the Harmful Psychiatric and Behavioral Effects of Different Forms of Child Maltreatment. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(11):1135–1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bethell CD, Carle A, Hudziak J, et al. Methods to Assess Adverse Childhood Experiences of Children and Families: Toward Approaches to Promote Child Well-being in Policy and Practice. Academic pediatrics. 2017;17(7S):S51–S69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McLennan JD, MacMillan HL, Afifi TO. Questioning the use of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) questionnaires. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2020;101:104331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Steptoe A, Marteau T, Fonagy P, Abel K. ACEs: Evidence, Gaps, Evaluation and Future Priorities. Social Policy and Society. 2019;18(3):415–424. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Reuben A, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, et al. Lest we forget: comparing retrospective and prospective assessments of adverse childhood experiences in the prediction of adult health. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2016;57(10):1103–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hardt J, Rutter M. Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: review of the evidence. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry. 2004;45(2):260–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wade R Jr., Cronholm PF, Fein JA, et al. Household and community-level Adverse Childhood Experiences and adult health outcomes in a diverse urban population. Child Abuse Negl. 2016;52:135–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pachter LM, Lieberman L, Bloom SL, Fein JA. Developing a Community-Wide Initiative to Address Childhood Adversity and Toxic Stress: A Case Study of The Philadelphia ACE Task Force. Academic Pediatrics. 2017;17(7):S130–S135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mersky JP, Janczewski CE, Topitzes J. Rethinking the Measurement of Adversity: Moving Toward Second-Generation Research on Adverse Childhood Experiences. Child Maltreatment. 2016;22(1):58–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Carrillo‐Álvarez E, Kawachi I, Riera‐Romaní J. Neighbourhood social capital and obesity: A systematic review of the literature. Obesity reviews. 2019;20(1):119–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cobb LK, Appel LJ, Franco M, Jones‐Smith JC, Nur A, Anderson CA. The relationship of the local food environment with obesity: a systematic review of methods, study quality, and results. Obesity. 2015;23(7):1331–1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gamba RJ, Schuchter J, Rutt C, Seto EY. Measuring the food environment and its effects on obesity in the United States: a systematic review of methods and results. Journal of community health. 2015;40(3):464–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yu E, Lippert AM. Neighborhood crime rate, weight‐related behaviors, and obesity: a systematic review of the literature. Sociology Compass. 2016;10(3):187–207. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bezold CP, Stark JH, Rundle A, et al. Relationship between Recreational Resources in the School Neighborhood and Changes in Fitness in New York City Public School Students. J Urban Health. 2017;94(1):20–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Baldwin JR, Reuben A, Newbury JB, Danese A. Agreement between prospective and retrospective measures of childhood maltreatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA psychiatry. 2019;76(6):584–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Widom CS. Are retrospective self-reports accurate representations or existential recollections? JAMA psychiatry. 2019;76(6):567–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hambrick EP, Tunno AM, Gabrielli J, Jackson Y, Belz C. Using multiple informants to assess child maltreatment: Concordance between case file and youth self-report. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2014;23(7):751–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kobulsky JM, Kepple NJ, Jedwab M. Abuse characteristics and the concordance of child protective service determinations and adolescent self-reports of abuse. Child maltreatment. 2018;23(3):269–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cooley DT, Jackson Y. Informant Discrepancies in Child Maltreatment Reporting: A Systematic Review. Child Maltreatment. 2020:1077559520966387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zeller MH, Noll JG, Sarwer DB, et al. Child maltreatment and the adolescent patient with severe obesity: Implications for clinical care. Journal of pediatric psychology. 2015;40(7):640–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.