Abstract

Mast cells (MCs) are important in intestinal homeostasis and pathogen defense but are also implicated in many of the clinical manifestations in disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome. The utility of specifically staining for MCs in order to quantify and phenotype them in intestinal biopsies in patients with gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms is controversial and is not a widely adopted practice. Whether or not intestinal MCs are increased or have a unique phenotype in individuals with hereditary alpha-tryptasemia (HαT), who have extra copies of the mast cell tryptase gene TPSAB1 and typically elevated baseline serum tryptase levels >8ng/mL is not known. We examined the duodenal biopsies of 17 patients with HαT and compared them to 15 patients with mast cell activation syndrome who had baseline serum tryptases <8ng/mL (MCAS-NT) and 12 GI-controls. We determined that the HαT subjects had increased MCs in the duodenum compared with MCAS-NT and GI-controls (median 30.0 [IQR 20.0 – 40.0] vs median 15.0 [IQR 5.00 – 20.0], p=0.013 and median 15.0 [IQR 13.8 – 20.0], p=0.004 respectively). These MCs were significantly found in clusters (<15 MCs) and were located throughout the mucosa and submucosa including the superficial villi compared with MCAS-NT and GI-control patients. Spindle-shaped MCs were observed in all groups including controls. These data demonstrate that HαT is associated with increased small intestinal MCs that may contribute to the prevalent gastrointestinal manifestations observed among individuals with this genetic trait.

Keywords: mast cells, tryptase, tryptasemia, gastrointestinal, duodenum, mast cell activation

Introduction

Mast cells (MCs) reside in the intestine and serve important functions in host defense, tissue homeostasis and repair (1, 2). However, in various allergic disorders including anaphylaxis and IgE-mediated food allergy, intestinal MCs inappropriately activate, which may lead to various gastrointestinal manifestations (3).

The number of MCs in the intestinal mucosa is thought to be relatively fixed but may be altered by external or local tissue factors such as infections, dietary substances, or inflammation. MCs may home to the mucosal layer in a T cell-dependent process and express only tryptase (4) whereas the constitutive MCs in the submucosal layer express both chymase and tryptase (5).

In subtypes of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) where MCs are thought to have a central pathogenic role, MCs have been found to be increased, although the data in published series are inconsistent (6). In one study, the number of mucosal MCs in the colon of a cohort of IBS patients with diarrhea was increased compared with a control cohort without symptoms but there was substantial overlap in the number of MCs and it was concluded that there was no clinical utility in quantifying colonic MCs in patients with IBS-like symptoms (7).

There have been several reports of cohorts of patients with mast cell disorders and IBS-like patients with atopic comorbidities who had elevated numbers of intestinal mucosal MCs, suggesting that in specific patient endotypes, enumerating MCs in the intestine may be justified (8, 9). In systemic mastocytosis (SM), the prototypic clonal mast cell disorder defined by an activating mutation in the KIT gene that leads to abnormal proliferation of MCs in the tissues including the intestine, assessment of intestinal MCs may help to confirm the diagnosis and to distinguish between various subtypes including indolent and aggressive disease (7). Conversely, intestinal MCs in undifferentiated non-clonal mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS) are thought to be in the normal range with regard to number, size, and appearance (10). Gastrointestinal manifestations in these patients likely result from abnormal activation and/or signaling of MCs similar to IBS (11) although the mechanisms are not known.

Patients have been identified who have an array of clinical manifestations similar to MCAS including various gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain and diarrhea, and an elevated baseline serum tryptase defined by extra-allelic copies of alpha tryptase at the TPSAB1 gene (12). These patients do not have findings of clonal mast cell disease, such as bone marrow mast cell aggregates, but the genetic trait has been shown to modify clinical manifestations of clonal and non-clonal mast cell disorders (13). The mechanisms of symptomatology in this group of patients, termed hereditary alpha tryptasemia (HαT), are an area of active investigation. One study showed that tryptase heterodimers increased cutaneous vibratory responses by selective activation of EGF-like module-containing mucin-like hormone receptor-like 2 (EMR2) (14), and a second study demonstrated selective activation of proteinase activated receptor-2 (PAR2) leading to increased vascular permeability (13). PAR2 is highly expressed on intestinal epithelium and activation by tryptase has been implicated in intestinal paracellular permeability (15). To examine the impact of HαT on gastrointestinal tract MCs, we characterized the number and appearance of MCs in small intestinal biopsies and determined whether these features differ from a clinically similar cohort of patients with MCAS with normal baseline serum tryptase (MCAS-NT) and a control group (GI-control).

Methods

Patient groups

This was a retrospective, multi-center, cohort study. Patients from the clinical databases of the Mastocytosis Center at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) and the Gastroenterology Division of the University of Florida (UF) were included who had been diagnosed with HαT and MCAS-NT. Two additional patients were included from the Laboratory of Allergic Diseases at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Patients with HαT had typical clinical manifestations, a baseline serum tryptase >8 ng/mL, and a confirmatory increased copy number of the TPSAB1 gene based on a DNA test (Gene by Gene, Houston, TX) or on a research basis at the NIH (J.J.L.) (16). Patients with MCAS-NT had signs and symptoms of mast cell activation, response to medications that block MCs or MC mediators, at least one documented elevated mast cell mediator during a period of symptoms, and a normal baseline serum tryptase and that was <8 ng/mL.

Patients had undergone at least one upper endoscopy at the respective institutions with biopsies of the duodenum (4–6 mucosal biopsies). Co-existing inflammatory conditions were allowed but they could not be active at the site of biopsy to be included. GI-control patients did not have evidence of an inflammatory condition or clinical manifestations to suggest mast cell activation syndrome and had the endoscopy for other reasons, such as to evaluate for Barrett’s esophagus or cause of anemia.

From the clinical databases and medical charts, demographic information, highest baseline serum tryptase level, TPSAB1 copy number, medications, mast cell activation symptoms, and associated atopic and inflammatory conditions were collected. From the clinical reports, the appearance of the duodenum at endoscopy and background histology findings from the hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain were recorded.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of BWH (2014P002321), UF (201702274), and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NCT01164241, NCT00852943).

Tissue Staining and Histology Analysis

All biopsies of the duodenum were fixed in paraffin and embedded and stained with hematoxylin and eosin to assess overall morphology, including the presence of inflammatory cells and intestinal architectural changes. Stain for CD117 (DAKO, rabbit polyclonal 1:150 dilution) was used to highlight MCs in the biopsy sections, which were enumerated and recorded as the mean number of MCs across at least five high power fields (HPF). Mast cell morphology (round or spindled) and MC locations (with at least 3 MCs/HPF) within the intestinal mucosa and submucosa were recorded. The MCs were assessed for the presence of clusters, which was defined by at least two but not more than fourteen MCs appearing to touch each other. Additional stains for CD25 (Lifespan Biosciences clone 4C9, 1:50 dilution), a marker of clonal MCs in systemic mastocytosis (17) and CD63 (Sigma Aldrich, rabbit polyclonal 1:500 dilution), a cell surface marker indicating mast cell activation (18), were performed on available tissue specimens and analyzed.

Statistics

Fisher’s Exact Test was used to compare binary variables between 2 groups (HαT vs. MCAS-NT, HαT vs. GI-control, and MCAS-NT vs. GI-control). Shapiro-Wilk’s method was used to assess the normality of continuous variables (data not shown). Based on results of Shapiro-Wilk’s analysis, age showed no significant departure from normality amongst groups, and subsequently, parametric t-test and ANOVA test were performed to assess differences in mean age between 2 groups and 3 groups, respectively. For the remainder of the continuous variables, Wilcoxon and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to assess differences in median values between 2 groups and 3 groups, respectively. P <0.05 was considered significant. All statistical tests were performed in R (version 4.0.2).

Results

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

We included 17 patients with HαT (11 from UF, 4 from BWH, 2 from NIH), 15 with MCAS-NT (13 from BWH, 2 from UF), and 12 GI-controls (all BWH). Demographic and clinical characteristics are detailed in Table 1. There was a high percentage of females in all three groups. In the GI-control group, the working diagnosis was IBS in 7/12 (58%) of the subjects, and esophagitis or gastritis without duodenitis in 5/12 (42%). In keeping with the defining characteristic of HαT, the median baseline serum tryptase was significantly greater than the MCAS-NT group (14.6 ng/mL vs 4.0 ng/mL, p<.001). Each patient with HαT had one extra copy of TPSAB1 encoding alpha-tryptase and there were no cases with two or more extra copies.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics

| HαT (n=17) | MCAS-NT (n=15) | GI-Control (n=12) | P-Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female (%) | 15 (88.2) | 14 (93.3) | 10 (83.3) | NS |

| Mean age ** (SD) | 47.3 (17.7) | 44.9 (13.1) | 45.3 (13.1) | NS |

| Median Serum Tryptase, ng/mL (IQR) | 14.6 x (13.0 – 18.0) |

4.00 x (3.10 – 4.90) |

n/a | x<0.001 |

| Symptoms | ||||

| Constipation (%) | 4 (23.5) | 6 (40) | 1 (8.3) | NS |

| Diarrhea (%) | 6 (35.3) x | 5 (33.3) xx | 0 (0) x xx | x0.028, xx0.047 |

| Abdominal pain (%) | 15 (88.2) | 10 (66.7) | 7 (58.3) | NS |

| Nausea/Vomiting (%) | 6 (35.3) | 7 (46.7) xx | 1 (8.3) x | xx0.043 |

| Flushing (%) | 11 (64.7) x | 13 (86.7) xx | 0 (0) x xx | x<0.001, xx<0.001 |

| Pruritis (%) | 9 (52.9) x | 5 (33.3) xx | 0 (0) x xx | x0.003, xx0.047 |

| Urticaria (%) | 5 (29.4) | 3 (20) | 0 (0) | NS |

| Medications | ||||

| Antihistamines alone (%) | 5 (29.4) | 5 (33.3) xx | 0 (0) xx | xx0.047 |

| Antihistamines and other1 (%) | 9 (52.9) x | 5 (33.3) xx | 0 (0) x xx | x0.003, xx0.047 |

| Proton pump inhibitors (%) | 4 (23.5) + | 10 (67.7) + | 6 (50.0) | +0.031 |

| Immunosuppressants (%) | 3 (17.6) | 2 (13.3) | 0 (0) | NS |

| Associated Conditions | ||||

| Other intestinal inflammatory condition2 (%) | 8 (47.0) x | 2 (13.3) | 0 (0) x | x0.009 |

| Other atopic condition3 (%) | 7 (41.1) | 5 (33.3) | n/a | NS |

| Hypermobile joints (%) | 6 (35.3) | 4 (26.7) | n/a | NS |

Oral cromolyn, ketotifen, leukotriene receptor antagonists

Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, eosinophil esophagitis, celiac

asthma, eczema

For binary variables, P-values are based Fisher’s Exact Test. For continuous variables except age, P-values are based on Wilcoxon test for 2 groups and Kruskal-Wallis test for 3 groups. Age was analyzed as a normal variable with P-values based on T test for 2 groups and ANOVA for 3 groups.

The predominant symptoms and medications directed at MCs or MC mediators at the time of endoscopy were similar between HαT and MCAS-NT patients as well as the number of patients with concomitant atopic conditions. Patients with hypermobile joints were well represented in both groups and consistent with the known association between MCAS and hypermobile Ehlers Danlos Syndrome (19). There were significantly more patients in the HαT group when compared to the GI-controls who had an intestinal inflammatory condition and were taking immunosuppressants including corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and biologics at the time of endoscopy. These conditions included Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, celiac disease, and eosinophilic esophagitis. 35% of the HαT group had an abnormal endoscopic appearance of the duodenum compared to 13% of the MCAS-NT group, though this observation was not statistically significant (Table 2). These findings were erythema and granular appearance. There was no ulceration or nodularity seen in any of the HαT or MCAS-NT subjects. Despite these endoscopic findings, only 23.5% of HαT patients had abnormal background histology findings reported from the routine hematoxylin and eosin stain and labeled most often as “mild” or “focal duodenitis” compared to 20% of the overall included MCAS-NT subjects (not statistically significant).

Table 2.

Duodenum Histology and MC Characteristics

| HαT (n=17) | MCAS-NT (n=15) | GI-Control (n=12) | P-Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endoscopy abnormal (%) | 6 (35.3) x | 2 (13.3) | 0 x | x0.028 |

| Histology abnormal ** (%) | 4 (23.5) | 3 (20) | 1 (8.3) | NS |

| Median number of MCs per HPF (IQR) | 30.0 x + (20.0 – 40.0) |

15.0 + (5.00 – 20.0) |

15.0 (13.8 – 20.0) |

x0.0043, +0.013 |

| Location of MCs | ||||

| Villi/superficial (%) | 10 (58.8) + | 2 (13.3) + | 2 (16.7) | +0.012 |

| Lamina Propria (%) | 17 (100) | 15 (100) | 12 (100) | |

| Muscularis (%) | 15 (88.2) x | 13 (86.7) xx | 3 (25) x xx | x0.001, xx0.002 |

| Submucosa (%) | 15 (88.2) x | 9 (60) | 5 (41.7) x | x0.014 |

| All 4 locations (%) | 9 (52.9) x + | 2 (13.3) + | 0 (0) x | x0.003, +0.028 |

| Presence of spindled MCs (%) | 13 (76.5) | 10 (66.6) | 11 (91.7) | NS |

| Median percentage of spindled MCs (IQR) | 5.00 (5.00 – 7.06) |

5.00 (0.00 – 10.0) |

5.00 (5.00 – 5.00) |

NS |

| CD25+ MCs (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NS |

| CD63+ MCs (%) | 2 (50) | 6 (40) | 3 (25) | NS |

| Presence of MC Clusters (%) | 14 (82.3) x + | 4 (26.7) + | 1 (8.3) x | x<0.001, +0.004 |

| Median number of MCs per cluster (IQR) | 3.00 (2.00 – 3.00) | 3.00 (3.00 – 3.25) | 4.00 (4.00 – 4.00) | NS |

| Median number of MC clusters per HPF (IQR) | 3.00 (2.25 – 4.00) | 2.50 (1.00 – 5.50) | 3.00 (3.00 – 3.00) | NS |

| Lymphocytic aggregates Associated with MC Small Aggregates (%) | 6 (42.8) x | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0) x | x0.028 |

Same statistical analysis as in Table 1

abnormal presence of neutrophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, architectural disturbance, etc.

Intestinal Mast Cell Histology

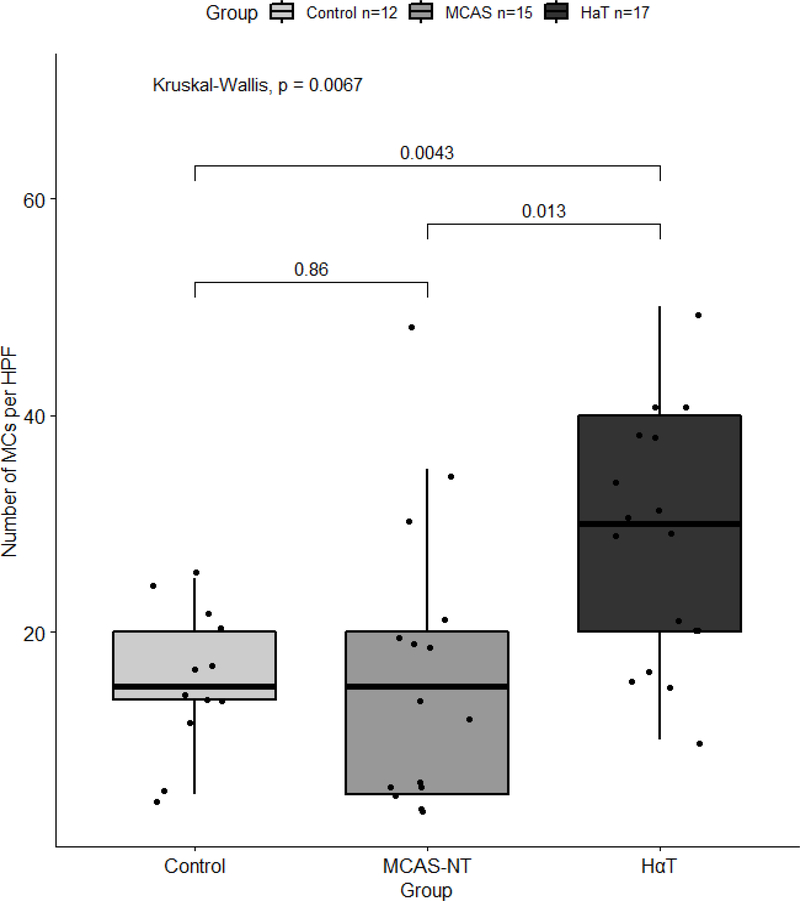

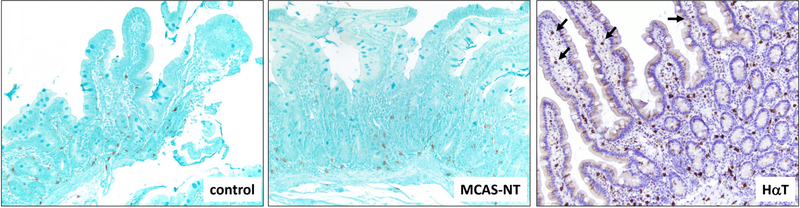

All duodenal biopsies were stained with CD117 to highlight the MCs for enumeration and morphologic analysis. The results are summarized in Table 2. The median number of MCs per HPF were significantly greater in the HαT group compared with the MCAS-NT group (median 30.0 [IQR 20.0 – 40.0] vs median 15.0 [IQR 5.00 – 20.0], p=0.013) and GI-control group (median 15.0 [IQR 13.8 – 20.0], p=0.004). There was no significant difference between the number of MCs per HPF in the MCAS-NT group and GI-controls (Table 2 and Figure 1). MCs were found scattered adjacent to the intestinal crypts in the mucosal lamina propria in all three patient groups (Figure 2). However, we found differences in MC locations throughout the duodenal biopsies, including the villi/superficial lamina propria, lamina propria crypts, muscularis mucosae, and submucosa. Not all duodenal biopsies were deep enough to include all four compartments, however, when present, 52.9% of HαT patients demonstrated MCs in all 4 tissue locations compared to 13.3% of MCAS-NT subjects (p=0.028) and none of the GI-controls (p=0.003). In addition, there was a higher number of HαT patients who had MCs located in the villi/surface epithelium compared to MCAS-NT and GI-control patients (p=0.012 and p=0.053, respectively (Figure 2). The location of MCs in the MCAS-NT group was similar to controls except at the muscularis mucosae location where more MCAS-NT patients were observed to have MCs compared with GI-controls (86.7% vs 25.0%, p=0.001).

Figure 1.

The number of mucosal mast cells per HPF in the duodenum between HαT, MCAS-NT, and GI-controls. Box and whisker plot depicting the medians and interquartile ranges.

Figure 2.

Location of mast cells (stained brown) in duodenal biopsies in control, MCAS-NT, and HαT patients. Patients with HαT have increased numbers of mast cells that are present in lamina propria, muscularis mucosae and submucosa, when compared to control and MCAS-NT patients. In addition, HαT patients demonstrate a greater number of mast cells in the villi/superficial lamina propria (arrows). CD117 stain; 100x magnification

Spindle-shaped MCs in the bone marrow have been previously described to be a feature of clonal MCs in systemic mastocytosis and is a minor criterion for the diagnosis of SM (20). We noted that the majority of patients in all three groups had spindle-shaped MCs in the duodenum. In all three groups spindle-shaped MCs accounted for 5% of the total observed MC population.

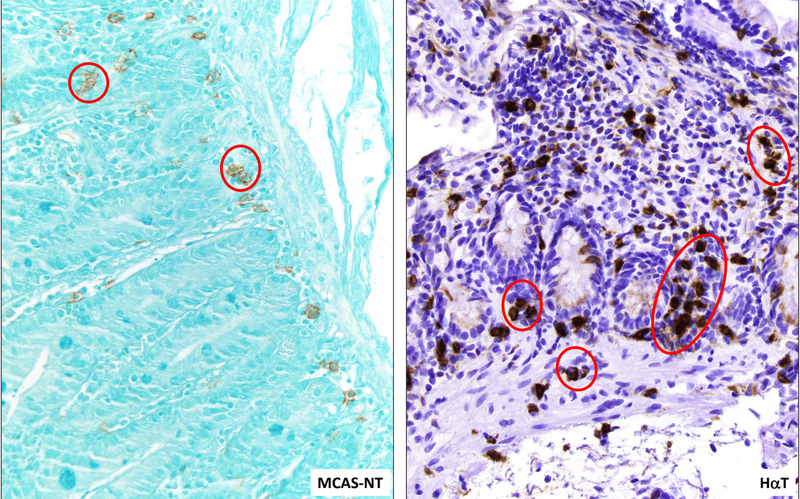

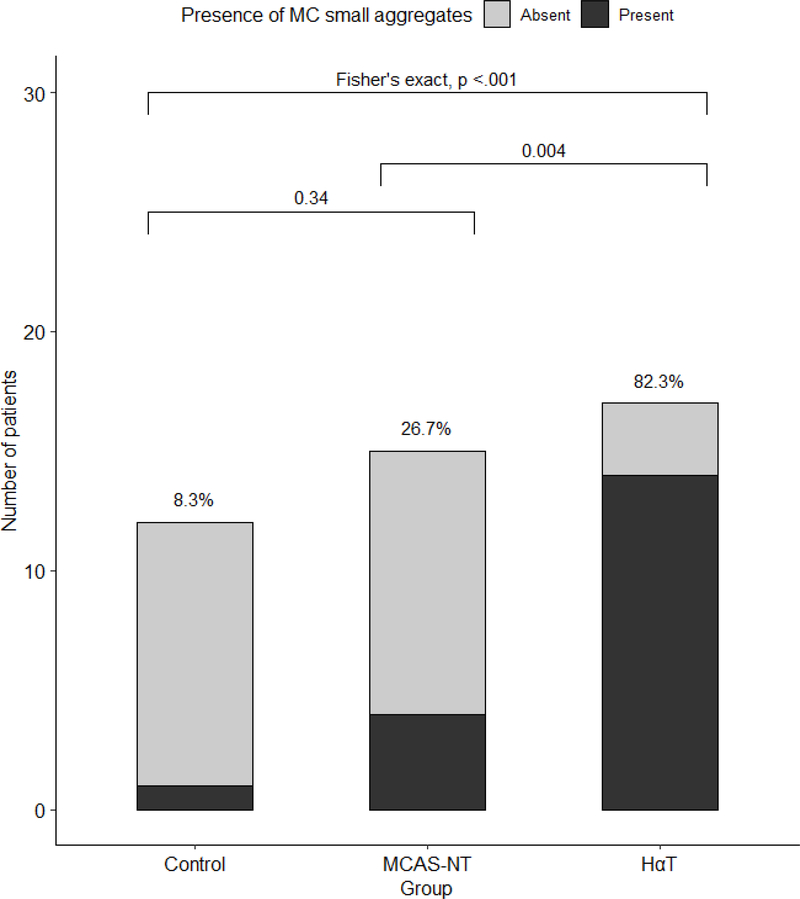

The major criterion for the diagnosis of SM is the presence of aggregates of 15 or more MCs in the involved tissues (20). We found the presence of clusters of MCs (<15 MCs) in the MCAS-NT and HαT groups with a significantly higher percentage observed in the HαT cohort compared to the MCAS-NT cohort (82.3% vs 26.7%, p=0.004) (Figures 3 and 4). There was only one GI-control patient with MC clusters. The number of clusters per HPF and number of MCs per cluster was similar among those individuals with HαT and MCAS-NT who had them (3.0 vs 2.5, p=0.83, and 3.0 vs 3.0, p=0.42, respectively). We also found that the MC clusters were associated with lymphocytic aggregates in 6 (42.8%) of the HαT subjects compared to 1 (6.7%) of the MCAS-NT subjects although this was not statistically significant. In the one GI-control subject with clusters, they were located in the submucosa and were not associated with lymphoid aggregates.

Figure 3.

Patients with HαT demonstrate higher numbers of mast cells, when compared to MCAS-NT. In addition, mast cell clusters (red circles) of at least 2 and no more than 14 cells appearing to touch each other are present in the lamina propria and muscularis mucosae in HαT patients and in the lamina propria in MCAS-NT patients. CD117 stain; 400x magnification

Figure 4.

The proportion of patients with mucosal mast cell clusters in the duodenum between HαT, MCAS-NT, and GI-controls. Bar graph depicts the patients with clusters among the total number of patients for each group.

The finding of MC clusters positively correlated with the number of MCs per HPF in the duodenum. All patients who had 40 or more MCs/HPF were noted to have clusters, including 5 in the HαT group and 2 in the MCAS-NT group. Among the patients in this study, there were 2 in the MCAS-NT group who had multiple endoscopies. One of these patients had three endoscopies in which MC clusters were not seen in any of the biopsies. Another patient had two endoscopies with no clusters seen.

Additional Mast Cell Staining

A feature of clonal intestinal mucosal MCs observed in systemic mastocytosis is aberrant staining for the surface marker CD25 (17). We did not find aberrant CD25 expression on MCs from any sample, including those present in small duodenal MC clusters, from any of the patients. To assess for evidence of MCs in an activated state, we also stained available tissues with CD63, a cell surface marker of activation. The percentages of HαT and MCAS-NT patients with positive CD63 staining were similar (2/4, 50% vs 6/15, 40% respectively) compared with 3/12 (25%) of the GI-controls.

Discussion

Upper endoscopy with duodenal biopsy is a frequently performed diagnostic test in patients with manifestations of mast cell activation including chronic gastrointestinal symptoms. Although other inflammatory intestinal disorders may be ruled out such as celiac disease and eosinophilic disorders, the clinical utility of endoscopy with routine biopsy and stains for MCs in patients with MCAS is not well established. There is no agreed upon value for what represents increased MCs in intestinal tissue. Moreover, were this defined, the clinical significance of an excess number of normal-appearing scattered MCs in the lamina propria remains unknown. In this study, we determined that patients with HαT and symptoms of mast cell activation had significantly more MCs in the duodenum - present in all segments of the mucosa including the superficial villi as well as the submucosa - compared to a group of patients with MCAS-NT and GI-controls. Furthermore, intestinal MCs in the HαT cohort were more frequently found in clusters and with lymphocytic aggregates. The data raise the possibility that the increased number of MCs observed throughout the duodenal mucosa in patients with HαT may account for the various gastrointestinal symptoms these patients experience.

Based on our data, we believe that specific stains to identify mast cells should be considered in patients undergoing upper endoscopy and duodenal biopsies who have clinical manifestations of mast cell activation including intestinal symptoms and a baseline serum tryptase >8 ng/mL. A diagnosis of HαT can be specifically considered if the median number of mucosal MCs/HPF is > 20, if the MCs are located throughout the mucosa including the superficial villi, and if the MCs are often found in small clusters (2–14 MCs appearing to touch each other). If these features are identified, we suggest genetic testing for HαT recognizing that patients may be identified who have >20 MCs/HPF in duodenal biopsies secondary to other intestinal inflammatory or functional disorders.

In patients with systemic mastocytosis, there can be increased clonal MCs in the tissues including the intestine as a consequence of activating mutations in the KIT gene responsible for MC maturation and proliferation (7, 21). The degree of mastocytosis in the tissue may be proportional to the serum tryptase levels and it is not clear if this correlates with mast cell activation symptoms in these patients. In one recent study, mast cell aggregates were incidentally found in colon biopsy specimens but these contained 15 or more MCs and were CD25+ which suggested systemic mastocytosis although no other features of systemic disease were found (22). Unlike SM, increased MCs in gastrointestinal tissues of individuals with HαT is not associated with clonal expansion in most individuals. Tryptase-dependent activation of PAR2 has been shown to lead to proliferation of mast cells (23) and significantly more MCs have been found in the bone marrow of patients with HαT compared to controls (24). How MCs are increased in the intestine of patients with HαT is unknown and it is possible that abnormal trafficking of MCs and other mechanisms may be involved. Furthermore, the mechanism by which the observed increase in intestinal MCs leads to gastrointestinal symptoms in HαT patients will need further study. One possibility is the release of tryptase tetramers from the MC that activate PAR2 at the surface epithelium and that results in altered intestinal permeability (14, 15).

This was a small study performed at institutions with expertise in the treatment of MC disorders and who receive referrals for patients with refractory symptoms, therefore the results may not be generalizable to a community practice. This study was retrospective and upper endoscopy and biopsies were performed on HαT and MCAS-NT subjects with a history of gastrointestinal symptoms. Whether or not the subjects were having active gastrointestinal symptoms at the time of the endoscopy was not recorded although it is presumed that the majority would have been well-compensated with regard to their reactivity in order to safely undergo the procedure. Many of the subjects were on treatment with medications to block mast cell mediators and had received these medications on the morning of the procedure which may have also affected the results such as the degree of mast cell activation as assessed by CD63 expression. There was a wide distribution in the number of duodenal MCs in the HαT and MCAS-NT groups that may suggest fluctuation in the numbers depending on the status of the tissue microenvironment at the particular point in time of the biopsy.

We noted a strong association with atopic conditions in our patients with HαT and MCAS-NT which may be due to overlapping genes and similar environmental modifiers (25). We also observed that about one third of our HαT and MCAS-NT patients had co-morbid joint hypermobility which has been previously described (12, 19). There was incomplete data on the prevalence of co-existing anaphylaxis in the HαT cohort so this was not analyzed in this study but was observed in 1/4 of the BWH HαT patients and 3/15 of the MCAS-NT patients. The prevalence of subjects with autonomic dysfunction was not evaluated in this study but its presence could impact symptoms in addition to those attributed to mast cell activation (26). We also observed that more patients in the HαT group had associated intestinal inflammatory conditions. This finding may have been the result of selection bias as two of the investigators (M.J.H. and S.C.G.) are gastroenterologists who also specialize in these conditions. However, it is also possible that the MCs in HαT prime the local tissue environment to perpetuate and sustain other chronic inflammatory conditions. Although whole exome sequencing of HαT patients has not revealed variants that have been associated with other inflammatory conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease, eosinophilic disorders, and celiac disease, further studies are needed (12).

One patient in the control group was found to have clusters of MCs similar to what was observed in the HαT cohort. Although she had not been worked up for MCAS or HαT and had not had a baseline serum tryptase test, she had described IBS symptoms, heart palpitations, and urinary frequency which are all potential symptoms of mast cell activation syndrome (27). However, it is noteworthy that the MC small aggregates in this GI-control patient were located in the submucosa which differed from what was observed in the HαT and MCAS-NT groups.

In this study, we focused on intestinal MCs in the mucosa that are accessible by endoscopic biopsy. Although it is possible to observe the muscularis mucosae and top portion of the submucosa, it is conceivable that MCs in the deeper submucosa and muscularis layers of the intestine, which would not be included in this study, particularly those in close proximity to nerve endings, are also altered in MCAS and HαT patients relative to controls. These findings are well documented in patients with IBS (28) and could account for some of the gastrointestinal manifestations in patients with MC disorders. However, we noted differences in locations of individual MC and MC clusters among the patient groups. In patients with HαT, the MCs tended to be located in all four observed tissue locations, whereas the majority of MCs and MC clusters in MCAS-NT were located at the bottom of the lamina propria adjacent to or involving the muscularis mucosae. An association between MCs and smooth muscle has long been appreciated and increased numbers of MCs have been observed in the smooth muscle in various inflammatory disorders including the bronchi of asthmatic patients (29). Although we did not observe any differences in symptomology in our MCAS-NT and HαT patients, larger numbers are needed and more detailed clinical scoring systems to determine whether the observed intestinal MC pathology characteristics correlate with symptoms.

Conclusion

In the small intestine of individuals with HαT, we found increased MCs throughout the mucosal layer including the superficial villi and that were frequently found in clusters and with lymphocytic aggregates. These findings were distinct from MCAS-NT patients who had baseline serum tryptase <8 ng/mL and GI-control subjects. It is possible that the increased intestinal MC burden we have identified among individuals with HαT may contribute to the gastrointestinal clinical manifestations observed in patients with this genetic trait. Our data suggest that patients with clinical manifestations of mast cell activation and a baseline serum tryptase >8 ng/mL and who are undergoing upper endoscopy for intestinal symptoms should have specific stains to identify mast cells. A diagnosis of HαT should be considered if more than 20 MCs/HPF and MC clusters are observed throughout the duodenal mucosa including the superficial villi.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: This research was supported in part by a combined grant from the Mastocytosis Society and American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (MJH), the Gatorade Trust through funds distributed by the University of Florida, Department of Medicine (SCG), extramural NIH fund 1R21TR002639-01A1 (MJH and SCG), and the Division of Intramural Research of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH (JJL). The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors do not have any financial disclosures with regards to the content in this manuscript.

References

- 1.Albert-Bayo M, Paracuellos I, Gonzalez-Castro AM, Rodriguez-Urrutia A, Rodriguez-Lagunas MJ, Alonso-Cotoner C, et al. Intestinal Mucosal Mast Cells: Key Modulators of Barrier Function and Homeostasis. Cells. 2019;8(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reber LL, Sibilano R, Mukai K, Galli SJ. Potential effector and immunoregulatory functions of mast cells in mucosal immunity. Mucosal Immunol. 2015;8(3):444–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang L, Song J, Hou X. Mast Cells and Irritable Bowel Syndrome: From the Bench to the Bedside. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2016;22(2):181–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Irani AM, Craig SS, DeBlois G, Elson CO, Schechter NM, Schwartz LB. Deficiency of the tryptase-positive, chymase-negative mast cell type in gastrointestinal mucosa of patients with defective T lymphocyte function. J Immunol 1987;138(12):4381–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Irani AA, Schechter NM, Craig SS, DeBlois G, Schwartz LB. Two types of human mast cells that have distinct neutral protease compositions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83(12):4464–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robles A, Perez Ingles D, Myneedu K, Deoker A, Sarosiek I, Zuckerman MJ, et al. Mast cells are increased in the small intestinal mucosa of patients with irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2019;31(12):e13718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doyle LA, Sepehr GJ, Hamilton MJ, Akin C, Castells MC, Hornick JL. A clinicopathologic study of 24 cases of systemic mastocytosis involving the gastrointestinal tract and assessment of mucosal mast cell density in irritable bowel syndrome and asymptomatic patients. Am J Surg Pathol 2014;38(6):832–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jakate S, Demeo M, John R, Tobin M, Keshavarzian A. Mastocytic enterocolitis: increased mucosal mast cells in chronic intractable diarrhea. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2006;130(3):362–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akhavein MA, Patel NR, Muniyappa PK, Glover SC. Allergic mastocytic gastroenteritis and colitis: an unexplained etiology in chronic abdominal pain and gastrointestinal dysmotility. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2012;2012:950582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamilton MJ, Hornick JL, Akin C, Castells MC, Greenberger NJ. Mast cell activation syndrome: a newly recognized disorder with systemic clinical manifestations. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;128(1):147–52 e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holtmann GJ, Ford AC, Talley NJ. Pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1(2):133–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lyons JJ, Yu X, Hughes JD, Le QT, Jamil A, Bai Y, et al. Elevated basal serum tryptase identifies a multisystem disorder associated with increased TPSAB1 copy number. Nat Genet 2016;48(12):1564–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lyons JJ, Chovanec J, O’Connell MP, Liu Y, Selb J, Zanotti R, et al. Heritable risk for severe anaphylaxis associated with increased alpha-tryptase-encoding germline copy number at TPSAB1. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le QT, Lyons JJ, Naranjo AN, Olivera A, Lazarus RA, Metcalfe DD, et al. Impact of naturally forming human alpha/beta-tryptase heterotetramers in the pathogenesis of hereditary alpha-tryptasemia. J Exp Med 2019;216(10):2348–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cenac N, Chin AC, Garcia-Villar R, Salvador-Cartier C, Ferrier L, Vergnolle N, et al. PAR2 activation alters colonic paracellular permeability in mice via IFN-gamma-dependent and -independent pathways. J Physiol 2004;558(Pt 3):913–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lyons JJ. Hereditary Alpha Tryptasemia: Genotyping and Associated Clinical Features. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2018;38(3):483–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hahn HP, Hornick JL. Immunoreactivity for CD25 in gastrointestinal mucosal mast cells is specific for systemic mastocytosis. Am J Surg Pathol 2007;31(11):1669–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kraft S, Fleming T, Billingsley JM, Lin SY, Jouvin MH, Storz P, et al. Anti-CD63 antibodies suppress IgE-dependent allergic reactions in vitro and in vivo. J Exp Med 2005;201(3):385–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonamichi-Santos R, Yoshimi-Kanamori K, Giavina-Bianchi P, Aun MV. Association of Postural Tachycardia Syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome with Mast Cell Activation Disorders. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2018;38(3):497–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valent P, Akin C, Metcalfe DD. Mastocytosis: 2016 updated WHO classification and novel emerging treatment concepts. Blood. 2017;129(11):1420–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Metcalfe DD, Mekori YA. Pathogenesis and Pathology of Mastocytosis. Annu Rev Pathol 2017;12:487–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johncilla M, Jessurun J, Brown I, Hornick JL, Bellizzi AM, Shia J, et al. Are Enterocolic Mucosal Mast Cell Aggregates Clinically Relevant in Patients Without Suspected or Established Systemic Mastocytosis? Am J Surg Pathol 2018;42(10):1390–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu X, Wang J, Zhang H, Zhan M, Chen H, Fang Z, et al. Induction of Mast Cell Accumulation by Tryptase via a Protease Activated Receptor-2 and ICAM-1 Dependent Mechanism. Mediators Inflamm 2016;2016:6431574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lyons JJ, Sun G, Stone KD, Nelson C, Wisch L, O’Brien M, et al. Mendelian inheritance of elevated serum tryptase associated with atopy and connective tissue abnormalities. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014;133(5):1471–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Portelli MA, Hodge E, Sayers I. Genetic risk factors for the development of allergic disease identified by genome-wide association. Clin Exp Allergy. 2015;45(1):21–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shibao C, Arzubiaga C, Roberts LJ 2nd, Raj S, Black B, Harris P, et al. Hyperadrenergic postural tachycardia syndrome in mast cell activation disorders. Hypertension. 2005;45(3):385–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weiler CR, Austen KF, Akin C, Barkoff MS, Bernstein JA, Bonadonna P, et al. AAAAI Mast Cell Disorders Committee Work Group Report: Mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS) diagnosis and management. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019;144(4):883–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barbara G, Stanghellini V, De Giorgio R, Cremon C, Cottrell GS, Santini D, et al. Activated mast cells in proximity to colonic nerves correlate with abdominal pain in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(3):693–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brightling CE, Bradding P, Symon FA, Holgate ST, Wardlaw AJ, Pavord ID. Mast-cell infiltration of airway smooth muscle in asthma. N Engl J Med 2002;346(22):1699–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]