Abstract

Background.

Long-acting pre-exposure prophylaxis (LA-PrEP) formulated as implants and injections are promising prevention method strategies offering simplicity, discretion, and long dose duration. Men are important end-users of LA-PrEP, and early assessment of their preferences could enhance downstream male engagement in HIV prevention.

Methods.

A discrete-choice experiment (DCE) survey was conducted with 406 men, aged 18-24, in Cape Town, South Africa, to assess preferences for 5 LA-PrEP attributes with 2-4 pictorially-depicted levels: delivery form, duration, insertion location, soreness, and delivery facility. Latent class analysis (LCA) was used to explore heterogeneity of preferences and estimate preference shares.

Results.

Median age was 21 (IQR 19-22) and 47% were MSM. Duration was the most important product attribute. LCA identified three classes: “Duration-dominant decision-makers” (46%) were the largest class, defined by significant preference for a longer-duration product. “Comprehensive decision-makers” (36%) had preferences shaped equally by multiple attributes, and preferred implants. “Injection-dominant decision-makers” (18%) had strong preference for injections (vs. implant) and were significantly more likely to be MSM. When estimating shares for a 2-month injection in the buttocks with mild soreness (HPTN regimen) vs. a 6-month implant (to arm) with moderate soreness (current target), 95% of “injection-dominant” would choose injections, whereas 79% and 63% of “duration-dominant” and “comprehensive”, would choose implant.

Conclusions.

Young South African men indicated acceptability for LA-PrEP. Preferences were shaped mainly by duration, suggesting a sizeable market for implants, and underscoring the importance of product choice. Further research into men’s acceptability of LA PrEP strategies to achieve engagement in these HIV prevention tools constitutes a priority.

INTRODUCTION

Oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is a highly efficacious biomedical HIV prevention method; however, its effectiveness has been challenged by a daily dosing regimen negatively impacting adherence [1]. Long-acting (LA) PrEP delivered by implant or injection addresses user preferences for simplicity, discretion, and longer-dose duration [2]. Currently, there are several PrEP implants in preclinical development, and the first human implant study (with women) presented promising findings in the summer of 2019 [3-5]. Injectable formulations of the integrase inhibitor cabotegravir, used as PrEP, and tested with cisgender men and transgender women (HPTN 083), and cisgender women (HPTN 084) announced superiority over oral PrEP in July and October 2020, respectively.[6, 7] Collectively, these long-acting delivery platforms offer a potential variety of future HIV prevention options for men and women. To date, acceptability for injectables among MSM and women has been high[8], although attitudes of novel long-acting delivery formulations with male non-MSM end-users, has been limited [9].

In sub-Saharan Africa, and South Africa specifically, the primary mode of HIV transmission is through heterosexual sex, however, most HIV prevention efforts do not successfully address heterosexual men’s needs, and their critical role in the cycle of HIV transmission [10]. MSM constitute a key population for HIV prevention efforts [11], and have high HIV incidence in urban areas, and prevalence estimates of 49.5% in greater Johannesburg, 25.5% in Cape Town, and 27.5% in Durban [12-16]. Thus, in South Africa, HIV prevalence among both MSM and non-MSM is high and increases with age, resulting in one-quarter (23.7%) of all men aged 35 to 39 years estimated as HIV-positive [17]. Unlike women of childbearing age, many men do not have regular interaction with the health care system, and are less likely to engage in HIV prevention or care [18]. Stigma and discrimination, particularly for MSM, further inhibit use of HIV prevention services [19]. Long-acting methods present an opportunity to potentially increase men’s engagement in HIV prevention in this setting.

We conducted a discrete choice experiment (DCE) among youth aged 18-24 in Cape Town to explore attitudes towards and preferences for LA injectables and implants for HIV prevention. Using random parameters logit (RPL) modelling, youth were found to have a strong preference for a longer dosing duration, and we identified some differences in preference between male and female subgroups within other attributes presented [20]. In the current paper, we focused on preferences among male youth, and used multiple techniques to understand potential market segments and shifts in preference share simulations for LA-PrEP. These analyses contribute insight into the varying preferences among groups of young men in South Africa for LA- injections and implants, and provide a stepping stone towards further integration of these essential populations of African men into HIV prevention.

METHODS

Study design and setting.

Our DCE was implemented in several communities in and around Cape Town City Centre in 2017-2019. A detailed description of our full study sample, that also included female youth, sampling methods, and results of a conjoint analysis has been published elsewhere [20]. Briefly, we used population-based representative sampling in two townships, Nyanga and Masiphumelele, to recruit youth meeting the eligibility criteria of being aged 18-24, HIV prevention research-naïve and residing in the sampled residential plot and to gather general opinions about long-acting HIV prevention method characteristics. MSM were recruited using a combination of respondent-driven sampling and convenience sampling approaches. During this study PrEP was available only to key population groups, which included MSM, and MSM with PrEP-experience were allowed to enroll.

Procedures.

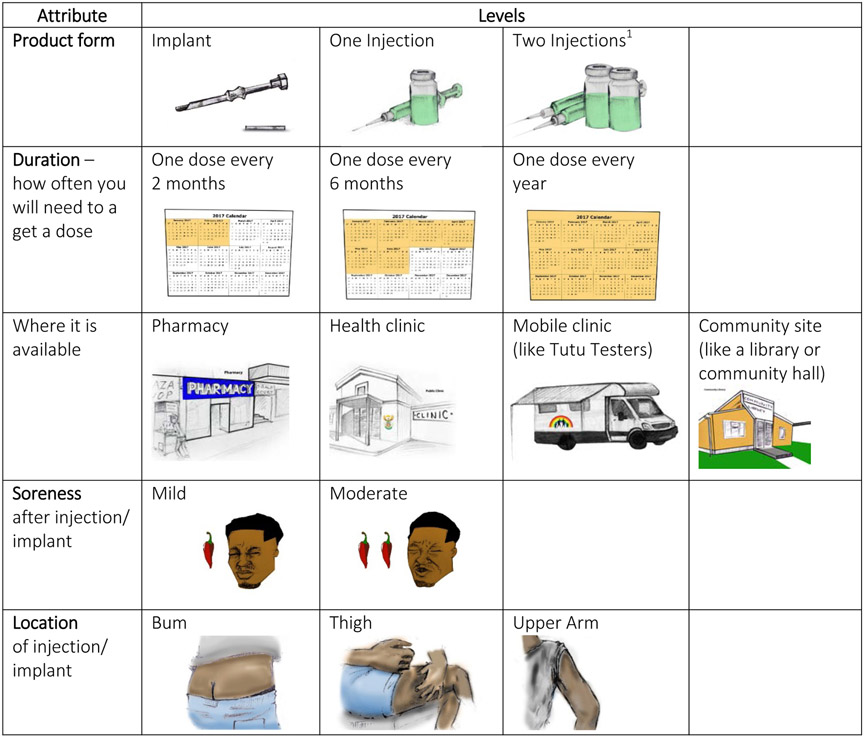

Following recruitment, participants presented at one of the community-based research sites and were shown a 4-minute video about PrEP: (https://vimeo.com/manage/222758306/general). to explain what PrEP was, and to describe the study’s purpose. Following the video, interested participants completed an informed consent process and a tablet-based questionnaire. The questionnaire included nine DCE choice questions, followed by a set of questions which directly assessed preferences, as well as a set of attitudinal, behavioral, and socio-demographic questions. The DCE survey instrument was developed following Good Research Practices for conjoint analysis [21]. Formative research was used to guide selection of five attributes to describe the LA-PrEP products: product formulation, dosing or how long the product lasts, where the product would be available, soreness from procedure, and location on body of injection/implant. Choice sets were made up of two hypothetical products characterized by the five product attributes (Figure 1). Each attribute had between two and four levels of variation, and all attribute levels were described with text and illustration. The DCE began with educational descriptions of the five product characteristics that would be explored during the survey. Following this, participants were handed the tablet to self-administer, with assistance as needed, until the choice set section was completed. A set of behavioral and attitudinal questions, including some that directly elicited product preferences, were subsequently administered by the interviewer in English or Xhosa.

Figure 1. Attributes and levels presented in DCE Survey (reproduced from Minnis et. Al.)[20].

1Two injections was included as an attribute level because it was the regimen used during HPTN 077 when this study was in development, and prior to the testing of a single injection during HPTN 083 and 084

For their time and transport costs, participants received a minor payment ($7) approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) at the University of Cape Town. HREC also reviewed and approved the study protocol and all data collection documents (REF number 751/2015).

Analysis.

Sample characteristics were summarized and compared by sexual orientation subgroup as MSM vs. MSW (only) using Chi-squared tests for categorical or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests for continuous measures. Direct assessments of preference (i.e. importance of individual product characteristics and product use disclosure considerations) were summarized and compared by sexual orientation with Chi-squared tests. We used a latent class model (LCM) to analyze choice data from the DCE to explore potential heterogeneity of preferences among men [22, 23]. The LCM assumes that there are distinct classes (segments of the sample whereby the preferences among members of the same class are identical but different from other classes. The classification for each individual is unknown, but membership probabilities are estimated. The number of classes was determined by best model fit; a series of LCMs were estimated with increasing number of classes (up to 5), and the optimal model was selected based on minimum Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and Akaike information criterion (AIC). All attributes were considered categorical and were effect-coded, meaning zero indicated the average effect across all levels as opposed to the omitted level in dummy variable coding [24]. Coefficients, therefore, represent normalized preference weights where positive weights signify greater preference and negative weights indicate less preference relative to other attribute levels evaluated.

We explored how 10 sociodemographic and behavioral characteristics, informed by previous research, influenced the probability of class membership. All covariates were first modelled together and only those with p≤0.10 were included in the final estimated LCM. The final normalized preference weight coefficients from the LCM were then used to calculate preference shares for hypothetical product profiles created to simulate product development scenarios. The EM algorithm implemented in Stata with the lclogit2 procedure was used for LCMs. To draw statistical inferences, we used the lclogit2 estimates as starting values for the lclogitml2 to obtain the final maximum likelihood output with standard errors [25]. All analyses were performed using Stata 15.0 (Statacorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Study population.

The study enrolled 406 male youth aged 18-24 (mean 20.8, median 21 years). By design, nearly half (47%, n=190) were MSM, the remainder were MSW. The key characteristics of the population are presented in Table 1. MSM differed on several characteristics compared to MSW, including educational achievement, current partner status and condom use at last sexual episode.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and behavioral characteristics of male participants. iPrevent Study, Cape Town, South Africa, 2017-2018.

| MSW | MSM | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | p-value5 | |

| Total | 216 | (100) | 190 | (100) | 406 | (100) | |

| Sociodemographic factors | |||||||

| Age, years - median (IQR) | 21 | (19-22) | 20 | (19-22) | 21 | (19-22) | 0.92 |

| Completed secondary school | 112 | (52) | 133 | (70) | 245 | (60) | <0.001 |

| Currently in school | 85 | (39) | 110 | (58) | 195 | (48) | <0.001 |

| Low educational attainment1 | 59 | (27) | 25 | (13) | 84 | (21) | <0.001 |

| Employed | 84 | (39) | 53 | (28) | 137 | (34) | 0.009 |

| Food insecurity (past month)2 | 50 | (23) | 69 | (36) | 119 | (29) | 0.004 |

| Fathered a child | 35 | (16) | 8 | (4) | 43 | (11) | <0.001 |

| Household crowding3 | 45 | (21) | 10 | (5) | 55 | (14) | <0.001 |

| Behavioral factors | |||||||

| Lifetime number of sex partners - median (IQR) | 6 | (4-10) | 5 | (4-10) | 6 | (4-10) | 0.50 |

| Has primary partner | 161 | (75) | 106 | (56) | 267 | (66) | <0.001 |

| Primary partner has other partners4 | 0.001 | ||||||

| Yes, know or suspect | 40 | (25) | 43 | (41) | 83 | (31) | |

| No | 63 | (39) | 20 | (19) | 83 | (31) | |

| Don’t know | 58 | (36) | 43 | (41) | 101 | (38) | |

| Multiple sex partners in past 3 months | 88 | (41) | 89 | (47) | 177 | (44) | 0.22 |

| Ever used condoms | 199 | (95) | 184 | (98) | 383 | (97) | 0.15 |

| Condom use at last sex | 119 | (55) | 131 | (69) | 250 | (62) | 0.01 |

| HIV testing and status | |||||||

| Ever tested for HIV | 193 | (89) | 180 | (95) | 373 | (92) | 0.05 |

| HIV status | 0.001 | ||||||

| Negative | 175 | (81) | 166 | (87) | 341 | (84) | |

| Positive | 4 | (2) | 11 | (6) | 15 | (4) | |

| Unknown | 37 | (17) | 13 | (7) | 50 | (12) | |

| Worried about getting HIV in next 12 months | 0.44 | ||||||

| Extremely/very | 55 | (26) | 41 | (22) | 96 | (24) | |

| Somewhat/ a little | 86 | (40) | 87 | (46) | 173 | (43) | |

| Not at all | 75 | (35) | 62 | (33) | 137 | (34) | |

| Community of residence | <0.001 | ||||||

| Masiphumelele | 91 | (42) | 6 | (3) | 97 | (24) | |

| Nyanga | 115 | (53) | 40 | (21) | 155 | (38) | |

| Other | 10 | (5) | 144 | (76) | 154 | (38) | |

Less than secondary education and not currently in school

“Sometimes” or “often” worried about not having enough food

More than 2 persons per room

Proportion among those who have a primary partner

P-value from Chi-squared test or two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum test

MSW: Men who have sex with women only; MSM: Men who have sex with men

Direct elicitation of preferences.

Preferences are presented in Table 2. When asked directly about the importance of six select attributes of long-acting PrEP, most men reported several features to be “very important”, including: perceived efficaciousness (94%), where one has to go to get it (88%), how often one has to use it (87%) and a product’s removability if side effects experienced (85%). Product efficacy, which was defined as “how well it works”, was designated as the single most important attribute to over half the men (57%), in particular to MSM vs. MSW (64% vs 52%, p=0.04). Privacy and disclosure were important to all (Table 2), although more MSW thought it was important to be able to use prevention methods without their partner knowing compared to MSM (46% vs. 27%, p<0.001). Most (94%) reported a willingness to pay for a long-acting product, with half willing to pay at least 115 South African Rand (~USD10).

Table 2.

Direct elicitation of preferences for long-acting pre-exposure prophylaxis among male youth in Cape Town, South Africa (N=406).

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Importance of attribute when selecting an HIV prevention product - "very important" | ||

| How well it works to prevent HIV | 380 | (94) |

| Where you have to go to get it | 356 | (88) |

| How often you have to use it | 353 | (87) |

| Removable if you experience side effects | 346 | (85) |

| Where on your body its injected or inserted | 239 | (59) |

| Can be used without your partner knowing | 98 | (24) |

| Most important attribute of six rated (top 3) | ||

| How well it works to prevent HIV | 234 | (58) |

| Removable if you experience side effects | 61 | (15) |

| Where you have to go to get it | 51 | (13) |

| Importance of using HIV prevention without partner knowing | ||

| Very important | 76 | (19) |

| Somewhat important | 76 | (19) |

| Not at all important | 254 | (63) |

| If product could be used secretly, would tell partner anyway | 316 | (78) |

| Importance of using HIV prevention without household knowing | ||

| Very important | 108 | (27) |

| Somewhat important | 88 | (22) |

| Not important | 210 | (52) |

| Cost willing to pay for a long-acting product (South African Rand) – mean, median (IQR) | 202, 115 | (50-200) |

| Not willing to pay | 23 | (6) |

| Implant characteristics | ||

| Most preferred location for implant insertion (top 3) | ||

| Inner upper arm | 196 | (48) |

| Outer upper arm | 94 | (23) |

| Inner thigh | 39 | (10) |

| Least preferred location for implant insertion (top 3) | ||

| Buttocks (“bum”) | 206 | (51) |

| Inner thigh | 60 | (15) |

| Lower back | 36 | (9) |

| Biodegradability preference | ||

| Dissolves over time | 285 | (70) |

| Does not dissolve and would need to be removed | 90 | (22) |

| No preference | 9 | (2) |

| Neither - would not use an implant | 22 | (5) |

| Injection characteristics | ||

| Most preferred location for injection (top 3) | ||

| Outer upper arm | 152 | (37) |

| Buttocks (“bum”) | 122 | (30) |

| Inner upper arm | 63 | (16) |

| Least preferred location for injection (top 3) | ||

| Buttocks (“bum”) | 175 | (43) |

| Inner thigh | 52 | (13) |

| Inner upper arm | 28 | (7) |

Preferences varied for where one would want an implant or injection to be inserted in the body (Table 2). The most popular preference for implant location, chosen by just under half, and more MSM (55%) than MSW (43%), was the inner upper arm. The next two most preferred locations were the outer upper arm (23%) and the inner thigh (10%). The least preferred location for an implant was the buttocks (“bum”) (51%) followed by the inner thigh (15%). The outer upper arm was selected as the most popular location (37%) for an injection, and there were no differences in location preference between MSM and MSW.

Biodegradable implants are under development, and we asked men whether they would prefer a product that dissolved over time or one that would need to be removed. Most (70%) expressed a preference for biodegradability. Of note, a small proportion of men (5%) indicated they would not use an implant.

Discrete choice modelling.

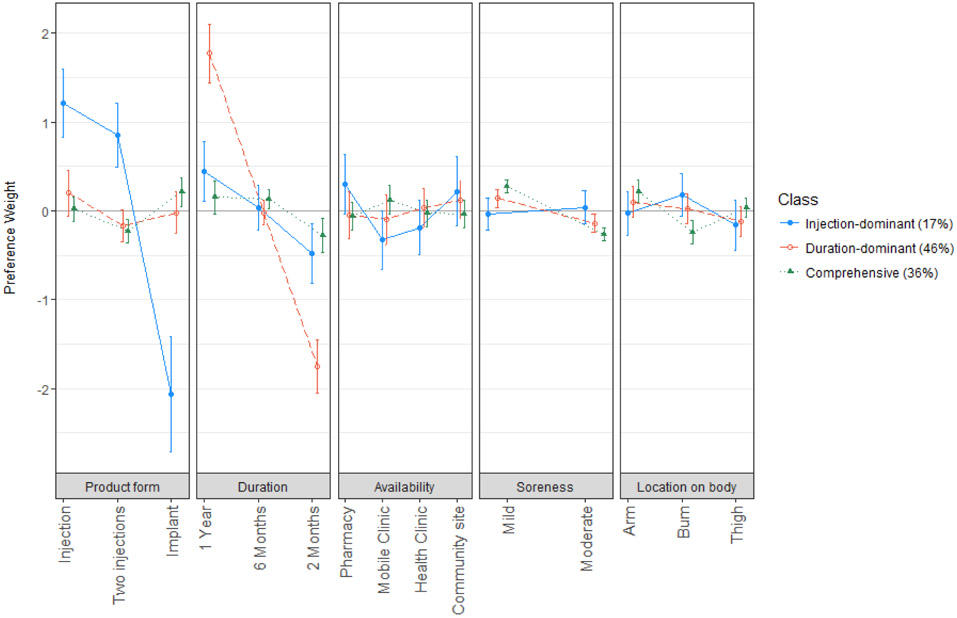

Latent class analysis was used to identify preference segments in the study population. Based on several model fit indices, the 3 class model was considered optimal for these data, and for each class, the model estimated a set of preference weights (Table 3, see also Figure 1, Supplemental Digital Content, preference weight graph) and the average membership probability.

Table 3.

Estimated preference shares, by class, for altering long-acting PrEP scenarios

| SCENARIO | PRODUCT | PRODUCT DESCRIPTION | “DURATION DOMINANT” N = 46% |

“COMPREHENSIVE DECISION- MAKERS” N=36% |

“INJECTION DOMINANT” N=17% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Product A | Implant, 6-month duration, available at a clinic, moderate soreness, administered in the arm | 0.79 | 0.63 | 0.05 |

| Product B | Injection (single), 2-month duration, available at a clinic, mild soreness, administered to the buttocks | 0.21 | 0.37 | 0.95 | |

| 2 | Product A | Implant, 12-month duration, available at a clinic, moderate soreness, administered in the arm | 0.96 | 0.63 | 0.08 |

| Product B | Injection (single), 2-month duration, available at a clinic, mild soreness, administered to the buttocks | 0.04 | 0.37 | 0.92 | |

| 3 | Product A | Implant, 12-month duration, available at a clinic, moderate soreness, administered in the arm | 0.80 | 0.53 | 0.05 |

| Product B | Injection (single), 6-month duration, available at a clinic, mild soreness, administered to the buttocks | 0.20 | 0.47 | 0.95 |

The largest class, with an average membership probability of 46%, was defined predominantly by a significant preference for a longer-acting product, and hence was deemed the “duration-dominant decision-makers” segment. Respondents in this class also preferred mild over moderate soreness during the injection/implant procedure (p=0.005), although duration was 12.5 times more important than the amount of anticipated soreness. The influence of product form on choice of a product was not as well defined, but trends suggested that men in this class most preferred a single injection (p=0.05). Product insertion/injection site on the body and the location where product could be obtained were not influential to choice (p>0.14) for this segment of male youth.

The second largest class membership probability (approximately 36%) were not particularly focused on any specific attribute, attaching similar relative importance to duration, soreness, product form, and location on the body. Hence, this segment was nicknamed “comprehensive decision-makers.” On average, this class preferred mild to moderate soreness (p<0.001), insertion in the arm over buttocks (p<0.001), and disliked 2-month long products, with no difference in preference between products of 6- and 12-month duration (p=0.02). Members also preferred implants over two injections (p=0.001). They did not show significant preference surrounding where the product was available (p=0.16).

The third and smallest class (17%) was associated with preferences overwhelmingly focused on product form. These males disliked implants and preferred injections (p<0.0001), with slight preference for one over two injections (p=0.05). As such, this segment was termed “injection-dominant decision-makers.” This class also had preference for longer duration products and opinions on where the product is available, but these opinions were significantly less important than the product form. Product form was 3.5-times as important as duration and nearly five times as important as the location where a product was made available. Men in this class preferred the product to be available at a pharmacy rather than a mobile clinic (p=0.02) or health clinic (p=0.06). Trends also suggested this class would prefer the product be offered at a community location rather than by a mobile clinic (p=0.08).

To characterize class membership, we included 10 potential covariates in the class membership probability function of our LC model that had been pairwise tested for independent correlation. Three variables were found to be associated with class membership at the p<0.10 level and were included in the final LC model: being <21 years of age, MSM, and having a partner who (potentially) has other partners (when asked if primary partner has other partners responded “yes” or “don’t know”). The “comprehensive decision-makers” class was set as the referent. MSM had higher odds of being associated with the “injection-dominant” (odds ratio [OR] 2.2, 95% CI: 1.1, 4.5; p=0.03) and “duration-dominant” (OR 1.8, 95% CI: 1.0, 3.3; p=0.07) class. Male youth with a primary partner who has or may have other sex partners had lower odds of being associated with the “injection-dominant” class (OR 0.5, 95%CI: 0.2, 0.9; p=0.06), and those under 21 years old had lower odds of being associated with the “duration-dominant” class (OR 0.6, 95% CI: 0.3, 1.0; p=0.06).

Preference Shares.

Preference shares were estimated with the preference weights of the final LCM to demonstrate how preferences for hypothetical product profiles within each class might shift when product attributes were changed (Table 3).

Scenario 1 represented the estimated share for Product A, an implant with a duration of 6 months (the likely minimum target duration for this technology), conferring moderate soreness, and being administered in the arm at a health clinic. This was compared to Product B, an injection-based product that had characteristics representative of the current regimen being tested in human trials: one injection administered to the buttocks at a health clinic every two-months with mild soreness at injection site. Comparing these products, the majority (93%) of “injection-dominant” men favored the injection. By contrast, most in the “duration-dominant” class (84%) and more than two-thirds of the “comprehensive decision-makers” class (66%) were estimated to choose the implant.

In scenario 2, we increased the duration of the implant to 12-months and kept all other product features the same as scenario 1. In response, more “duration-dominant” men were expected to choose the implant (96%). There was no significant shift in the choices of “injection-dominant” or “comprehensive decision-makers.”

For scenario 3, all characteristics were the same as in scenario 2 except the duration of the injections was increased from 2- to 6-months. In this scenario, the preferences among men in the “injection-dominant” and “duration-dominant” classes were similar to those in scenario 1. The “comprehensive decision-makers,” group however, was more divided, with nearly equal shares estimated to choose each product, suggesting that if the injection conferred at least 6 months of protection, this class would be as likely to choose a 12-month implant as a 6-month single injection.

DISCUSSION

Men, both MSM and MSW, in the HIV-endemic setting of South Africa are a critical end-user population for novel forms of long-acting PrEP. In this study we aimed to explore interest in implants and injections, and to understand which attributes of a LA- product were important to different segments of male end-users. We identified several key findings. First, young men expressed strong overall interest in long-acting HIV prevention methods. In the stated preference portion of the survey only 5% said they would never use an implant. Secondly, three broad segments of male end-user preferences were evident and highlighted the attributes of most importance. Product form (implant vs. injection(s)) and product duration (2, 6, 12 months) were the characteristics most important to overall preference for two-thirds of men, whereas for the substantial minority of men in the “comprehensive” group, a more holistic consideration of product characteristics was salient. Finally, when product attributes were altered in simulated scenarios of preference shares, an increase in product duration drove shifts in estimated preferences for other attributes. A sizeable proportion of men were estimated to hypothetically select an implant over an injection if the former offered 4- or 6- months of additional protection – suggesting a preference and potential future demand for this novel technology among male-users.

There is well-established global experience among women for use of implants [26] and injections for contraception [27], however there is extremely limited knowledge of implant use—for any indication—in men globally, and no known knowledge of implant use by men in South Africa. Implant products for a few different indications are available to male-users, including delivery of buprenorphine to treat opioid dependence for a duration of 6 months, and a previously approved, but discontinued, product to treat prostate cancer, breast cancer, and endometriosis [28-32]. Injections are also a new product in HIV prevention, and the concept of being injected is arguably familiar to men. In these data we see evidence that a substantial proportion of men, predominantly represented in the “duration-dominant” and “comprehensive” classes, would choose an implant over the injection regimen being tested in current trials. These estimates offer some evidence to implant developers that their products could be acceptable to future end-users. The external validity of DCE findings – linking hypothetical preferences to actual behavior- is unknown, although DCE reportedly offer fairly good predictions into what end-users will choose to take up [33]. That said, several other factors beyond these attributes will influence behavior, particularly in the context of HIV prevention for youth, and in resource-challenged circumstances [34]. Consequently, these findings are encouraging, but several other product-agnostic social, cultural or structural factors may influence future interest and demand for implants in an African setting.

Not everyone in this study wanted the same features of a long-acting HIV prevention method, highlighting the importance of identifying population segments. Research and utilization statistics with women in the fields of contraception and HIV prevention have demonstrated that users want choice [35, 36], and that when more options are available, coverage is expanded [37]. Here we report evidence that men also favor different options, and while preference shares showing an interest for implants is encouraging, it is likewise encouraging that many men favor injections, particularly in light of recent results demonstrating the superiority of cabotegravir injections (vs. oral PrEP) in men [38]. Although suggestive of a trend, but inconclusive (p>0.05), men who had partners with other partners, or of unknown fidelity were more likely to favor the longer-acting implant – potentially because of enhanced risk perception. Similarly, younger men under 21 were less likely to be driven by product duration, perhaps because they were in sexual relationships of less consistent duration. A study of HIV prevention method preference among South African heterosexual men reported that 48% would favor LA PrEP compared to oral PrEP or condoms [39], suggesting both a demand for and potential future acceptability of LA methods, and also an interest in a diversity of approaches. Also of interest was that a substantial minority felt it was very important that a method could be used secretly, and without the knowledge of a sexual partner or household member.

In this analysis, although almost a third seemed to evaluate multiple elements of a LA product, the product form and duration drove preferences for most. These results echo the findings of our RPL modelling in a separate analysis among male and female youth from this cohort [20], and point to the importance of several structural and socio-behavioral considerations in the lives of young men. This study’s formative research used qualitative methods to explore the context of HIV prevention with youth [40, 41], and reported that dosing duration is important because it is linked to clinic visits, which can be perceived as a burden, stigmatizing, and incongruent with some masculinity norms [42]. As long-acting HIV treatment strategies [43], are being considered for licensure and roll-out, important concomitant implementation issues such as innovative ways to deliver doses, e.g. mobile shot clinics, and meet ongoing testing needs (e.g., through self-testing) require exploration.

In this study preferences among MSM vs. MSW varied somewhat. MSM were more likely to be in the “injection-dominant” class, who more likely to want to avoid implants. MSM may not inherently dislike the option of implants, but may simply be more comfortable and familiar with injections, and familiarity has been shown to drive acceptability preference in other analyses [44]. Similarly, if MSM are already taking oral PrEP, they may be satisfied with their regimen, or less concerned about regular clinic visits. MSM preferences in our RPL modelling similarly highlighted that MSM preferred injections over implants, and that MSM were keen on duration, but duration was most important for MSW [20]. By contrast, in a US-based online study of over 500 MSM’s preferences for prevention, an overall preference for male condoms vs. other PrEP delivery platforms was reported, and within PrEP delivery options, preferences were split between tablets and a non-visible implant, with injections less frequently selected [9].

There are several potential limitations to this study. These data come from a DCE, and DCE’s measure hypothetical preferences for product attributes and levels, rather than acceptability rooted in actual experience. This methodology was necessary for this research since one LA injectable candidate was currently only available in phased trials, and no implant candidates were being tested among humans in Africa. A small systematic review provides some evidence that DCEs have fairly good ability (88%) to predict use of a product that is not currently used (opt-in)[33]. Second, the preferences and trade-offs included in this analysis are limited to those attributes and levels included in our DCE instrument, and how these were understood and cognitively processed by our youth respondents. There may be other important components of LA PrEP that were not included. However, we completed formative research and cognitive interviews with our target population, to determine the most salient attributes and their levels. Finally, the DCE did not compare LA-PrEP formulations to oral PrEP, which may have enabled interesting or important preference comparisons or considerations.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that male youth in South Africa, both MSW and MSM, are interested in LA-PrEP, with preferences defined by three classes of end-users: those driven by dosing duration, those with comprehensive perspectives, and the smallest class driven by an injectable product form. The feasibility of delivery of injectable PrEP to male youth in a South African setting is currently unknown and may pose several complex implementation and policy challenges, nevertheless, end-users are interested, and likely to uptake this technology recently reported to be highly efficacious[38]. The interest in LA-PrEP, and the preferences expressed among these male South African youth, highlight potential demand and market segments that can and should be actively engaged as part of the movement to expand HIV prevention method options [45].

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

Normalized preferences weights for attributes of a long-acting PrEP product, per latent class (N=406). Positive weights indicate greater preference and negative weights indicate less preference relative to other attribute levels evaluated.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest/Sources of Funding: None of the authors have declared conflicts of interest or sources of funding relevant to this research.

References

- 1.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;363(27):2587–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. PubMed PMID: 21091279; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3079639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luecke EH, Cheng H, Woeber K, Nakyanzi T, Mudekunye-Mahaka IC, van der Straten A. Stated product formulation preferences for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among women in the VOICE-D (MTN-003D) study. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2016;19(1):20875. Epub 2016/06/02. doi: 10.7448/ias.19.1.20875. PubMed PMID: 27247202; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4887458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson LM, Krovi SA, Li L, Girouard N, Demkovish ZR, Myers D, et al. Characterization of a reservoir-style implant for sustained release of tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Pharmaceutics. 2019;11(315). doi: doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics11070315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li LA, Krovi SA, Norton C, Luecke E, Demkovich Z, Johnson P, et al. Biodegradable implant for delivery of antiretroviral (ARV) and hormonal contraceptive CROI; Boston, Massachusetts: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matthews R, Barrett S, Patel M, Zhu W, Fillgrove K, Haspeslagh L, et al. First-in-human trial of MK-8591-eluting implants demonstrates concentrations suitable for HIV prophylaxis for at least one year. IAS 2019; Mexico City, Mexico: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 6.HPTN 084 Study Demonstrates Superiority of CAB LA to Oral FTC/TDF for the Prevention of HIV [Internet]. Durham, NC, USA; 2020; November 9, 2020. Available from: https://www.hptn.org/news-and-events/press-releases/hptn-084-study-demonstrates-superiority-of-cab-la-to-oral-ftctdf-for [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landowitz R HPTN 083 FINAL RESULTS: Pre-exposure Prophylaxis containing long-acting injectable cabotegravir is safe and highly effective for cisgender men and transgender women who have sex with men. AIDS 2020; Virtual2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tolley EE, Zangeneh SZ, Chau G, Eron J, Grinsztejn B, Humphries H, et al. Acceptability of Long-Acting Injectable Cabotegravir (CAB LA) in HIV-Uninfected Individuals: HPTN 077. AIDS and behavior. 2020. Epub 2020/02/14. doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-02808-2. PubMed PMID: 32052214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greene GJ, Swann G, Fought AJ, Carballo-Dieguez A, Hope TJ, Kiser PF, et al. Preferences for Long-Acting Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP), Daily Oral PrEP, or Condoms for HIV Prevention Among U.S. Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS and behavior. 2017;21(5):1336–49. Epub 2016/10/23. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1565-9. PubMed PMID: 27770215; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5380480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdool Karim Q, Baxter C, Birx D. Prevention of HIV in adolescent girls and young women: key to an AIDS-free generation. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2017;75(Suppl 1):S17–s26. Epub 2017/04/12. doi: 10.1097/qai.0000000000001316. PubMed PMID: 28398993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.UNAIDS. Fast-Track: ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030 Geneva: UNAIDS, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baral S, Burrell E, Scheibe A, Brown B, Beyrer C, Bekker L-G. HIV risk and associations of HIV infection among men who have sex with men in peri-urban Cape Town, South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:766-. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-766. PubMed PMID: 21975248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lane T, Raymond HF, Dladla S, Rasethe J, Struthers H, McFarland W, et al. High HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men in Soweto, South Africa: results from the Soweto Men's Study. AIDS and behavior. 2011;15(3):626–34. Epub 2009/08/08. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9598-y. PubMed PMID: 19662523; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2888758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.HPTN 075 study demonstrates high rate of HIV infection among African MSM and TGW [Internet]. Durham, NC: HPTN Newsletter; 2018; October 24. Available from: https://www.hptn.org/news-and-events/press-releases/hptn-075-study-demonstrates-high-rate-of-hiv-infection-among-african [Google Scholar]

- 15.President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). South African country operational plan 2017 (COP17) strategic direction summary (SDS). Washington, DC: President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, 2017. March 16. Report No. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lane T, Osmand T, Marr A, Struthers H, McIntyre JA, Shade SB. Brief Report: High HIV Incidence in a South African Community of Men Who Have Sex With Men: Results From the Mpumalanga Men's Study, 2012-2015. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2016;73(5):609–11. Epub 2016/11/17. doi: 10.1097/qai.0000000000001162. PubMed PMID: 27851715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC). The Fifth South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence, Behaviour and Communication Survey. Cape Town: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adeyeye AO, Stirratt MJ, Burns DN. Engaging men in HIV treatment and prevention. Lancet (London, England). 2018;392(10162):2334–5. Epub 2018/12/12. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32994-5. PubMed PMID: 30527600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Risher K, Adams D, Sithole B, Ketende S, Kennedy C, Mnisi Z, et al. Sexual stigma and discrimination as barriers to seeking appropriate healthcare among men who have sex with men in Swaziland. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2013;16(3 Suppl 2):18715-. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.3.18715. PubMed PMID: 24242263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minnis AM, Atujuna M, Browne EN, Ndwayana S, Hartmann M, Sindelo S, et al. Preferences for long-acting Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention among South African youth: results of a discrete choice experiment. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2020;23(6):e25528. Epub 2020/06/17. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25528. PubMed PMID: 32544303; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7297460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bridges JFP, Hauber AB, Marshall D, Lloyd A, Prosser LA, Regier DA, et al. Conjoint Analysis Applications in Health—a Checklist: A Report of the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Conjoint Analysis Task Force. Value in Health. 2011;14(4):403–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boeri M, Saure D, Schacht A, Riedl E, Hauber B. Modeling Heterogeneity in Patients' Preferences for Psoriasis Treatments in a Multicountry Study: A Comparison Between Random-Parameters Logit and Latent Class Approaches. PharmacoEconomics. 2020;38(6):593–606. Epub 2020/03/05. doi: 10.1007/s40273-020-00894-7. PubMed PMID: 32128726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hensher D, Rose J, Greene W. Applied choice analysis: a primer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hauber AGJ, Groothuis-Oudshoorn C. . Statistical methods for the analysis of discrete choice experiments: a report of the ISPOR Conjoint Analysis Good Research Practices Task Force. Value Health. 2016;19(4):300–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoo HI. lclogit2: An Enhanced Module to Estimate Latent Class Conditional Logit Models. In: 10.2139/ssrn.3484429 AaShscao, editor. 2019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mullick S, Chersich MF, Pillay Y, Rees H. Introduction of the contraceptive implant in South Africa: Successes, challenges and the way forward. South African medical journal = Suid-Afrikaanse tydskrif vir geneeskunde. 2017;107(10):812–4. Epub 2018/02/06. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2017.v107i10.12849. PubMed PMID: 29397679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacobstein R Liftoff: The Blossoming of Contraceptive Implant Use in Africa. Global Health: Science and Practice. 2018;6(1):17–39. doi: 10.9745/ghsp-d-17-00396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McLachlan RI, McDonald J, Rushford D, Robertson DM, Garrett C, Baker HWG. Efficacy and acceptability of testosterone implants, alone or in combination with a 5α-reductase inhibitor, for male hormonal contraception. Contraception. 2000;62(2):73–8. doi: 10.1016/S0010-7824(00)00139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Handelsman DJ, Mackey MA, Howe C, Turner L, Conway AJ. An analysis of testosterone implants for androgen replacement therapy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1997;47(3):311–6. Epub 1997/11/28. doi: doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1997.2521050.x. PubMed PMID: 9373452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang C, Swerdloff RS. Hormonal approaches to male contraception. Curr Opin Urol. 2010;20(6):520–4. Epub 2010/09/03. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e32833f1b4a. PubMed PMID: 20808223; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3078035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heinemann K, Saad F, Wiesemes M, White S, Heinemann L. Attitudes toward male fertility control: results of a multinational survey on four continents. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(2):549–56. Epub 2004/12/21. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh574. PubMed PMID: 15608042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neale J, Tompkins CNE, McDonald R, Strang J. Implants and depot injections for treating opioid dependence: qualitative study of people who use or have used heroin. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;189:1–7. Epub 2018/06/02. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.03.057. PubMed PMID: 29857327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quaife M, Terris-Prestholt F, Di Tanna GL, Vickerman P. How well do discrete choice experiments predict health choices? A systematic review and meta-analysis of external validity. The European journal of health economics : HEPAC : health economics in prevention and care. 2018;19(8):1053–66. Epub 2018/01/31. doi: 10.1007/s10198-018-0954-6. PubMed PMID: 29380229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Bekker-Grob EW, Donkers B, Bliemer MCJ, Veldwijk J, Swait JD. Can healthcare choice be predicted using stated preference data? Social science & medicine (1982). 2020;246:112736. Epub 2019/12/31. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112736. PubMed PMID: 31887626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Minnis AM, Montgomery ET, Napierala S, Browne EN, van der Straten A. Insights for Implementation Science From 2 Multiphased Studies With End-Users of Potential Multipurpose Prevention Technology and HIV Prevention Products. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2019;82 Suppl 3:S222–s9. Epub 2019/11/26. doi: 10.1097/qai.0000000000002215. PubMed PMID: 31764258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Montgomery ET, Beksinska M, Mgodi N, Schwartz J, Weinrib R, Browne EN, et al. End-user preference for and choice of four vaginally delivered HIV prevention methods among young women in South Africa and Zimbabwe: the Quatro Clinical Crossover Study. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2019;22(5):e25283. Epub 2019/05/10. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25283. PubMed PMID: 31069957; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6506690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sutherland EG, Otterness C, Janowitz B. What happens to contraceptive use after injectables are introduced? An analysis of 13 countries. International perspectives on sexual and reproductive health. 2011;37(4):202–8. Epub 2012/01/10. doi: 10.1363/3720211. PubMed PMID: 22227627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.HPTN 083 Study Demonstrates Superiority of Cabotegravir for the Prevention of HIV [Internet]. Durham, NC; 2020; July 7, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheng CY, Quaife M, Eakle R, Cabrera Escobar MA, Vickerman P, Terris-Prestholt F. Determinants of heterosexual men's demand for long-acting injectable pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV in urban South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):996. Epub 2019/07/26. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7276-1. PubMed PMID: 31340785; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6657137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Montgomery E, Atujuna M, Krogstad E, Hartmann M, Ndwayana S, O’Rourke S, et al. The Invisible Product: Preferences for sustained-release, long-acting Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis among South African youth. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2018. doi: NIHMS1517492, Publ.ID: QAIV19032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krogstad EA, Atujuna M, Montgomery ET, Minnis A, Ndwayana S, Malapane T, et al. Perspectives of South African youth in the development of an implant for HIV prevention. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2018;21(8):e25170. Epub 2018/08/29. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25170. PubMed PMID: 30152004; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6111144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sileo KM, Fielding-Miller R, Dworkin SL, Fleming PJ. What Role Do Masculine Norms Play in Men's HIV Testing in Sub-Saharan Africa?: A Scoping Review. AIDS and behavior. 2018;22(8):2468–79. Epub 2018/05/20. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2160-z. PubMed PMID: 29777420; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6459015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Margolis DA, Gonzalez-Garcia J, Stellbrink HJ, Eron JJ, Yazdanpanah Y, Podzamczer D, et al. Long-acting intramuscular cabotegravir and rilpivirine in adults with HIV-1 infection (LATTE-2): 96-week results of a randomised, open-label, phase 2b, non-inferiority trial. Lancet (London, England). 2017;390(10101):1499–510. Epub 2017/07/29. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(17)31917-7. PubMed PMID: 28750935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van der Straten A, Shapley-Quinn MK, Reddy K, Cheng H, Etima J, Woeber K, et al. Favoring “Peace of Mind”: A Qualitative Study of African Women's HIV Prevention Product Formulation Preferences from the MTN-020/ASPIRE Trial. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2017;31(7):305–14. doi: 10.1089/apc.2017.0075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grimsrud A, Ameyan W, Ayieko J, Shewchuk T. Shifting the narrative: from "the missing men" to "we are missing the men". Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2020;23 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):e25526. Epub 2020/06/27. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25526. PubMed PMID: 32589325; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7319250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.