SUMMARY

Contributions of the viral component of the microbiome - the virome - to the development of innate and adaptive immunity are largely unknown. Here, we systematically defined the host response in mice to a panel of eukaryotic enteric viruses representing six different families. Infections with most of these viruses were asymptomatic in the mice, the magnitude and duration of which was dependent on the microbiota. Flow cytometric and transcriptional profiling of mice mono-associated with these viruses unveiled general adaptations by the host, such as lymphocyte differentiation and IL-22 signatures in the intestine, as well as numerous viral strain-specific responses that persisted. Comparison with a dataset derived from analogous bacterial mono-association in mice identified bacterial species that evoke an immune response comparable to the viruses we examined. These results expand an understanding of the immune space occupied by the enteric virome and underscore the importance of viral exposure events.

Graphical Abstract

eTOC Blurb

Comprehensive profiling of immune responses to a panel of eukaryotic viruses reveals widespread capacity for asymptomatic intestinal infection and durable alterations that are both strain-specific and common to multiple viruses. Cross-comparisons highlight overlapping yet distinct immune space occupied by viral and bacterial members of the gut microbiota.

INTRODUCTION

Our symbiotic relationship with the gut microbiota exemplifies host-microbe coadaptation. In addition to the mutually beneficial exchange of nutrients, intestinal colonization by bacteria shapes the development and function of the mammalian immune system (Honda and Littman, 2012; Round and Mazmanian, 2009). The outcome of these reactions can be advantageous, as in colonization-resistance to pathogens, or adverse, as in chronic disorders such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Investigations of the host response to individual bacterial species using gnotobiotic animals have led to important insights into the range of immune processes fine-tuned by the gut microbiota (Geva-Zatorsky et al., 2017; Sefik et al., 2015; Tan et al., 2016). Consequences of intestinal exposure to viruses on the mucosal immune system are less characterized. Enteric eukaryotic viruses are detected in healthy infant fecal specimens as early as a few days after birth and become increasingly prevalent and diverse during development (Liang et al., 2020; Lim et al., 2015). Metagenomics analyses of the viral microbiome (virome) have linked various viruses to immune-mediated diseases (Iliev and Cadwell, 2020) suggesting viral exposure has long-term immune consequences.

Our studies with murine norovirus (MNV) indicate that eukaryotic viruses can establish a symbiotic relationship with the host akin to commensal bacteria. Germ-free (GF) or antibiotic-treated mice display numerous intestinal defects, including reduced numbers of resident T cells and susceptibility to chemical injury (Round and Mazmanian, 2009). Inoculation with the persistent MNV strain, CR6, reverses these defects by inducing type I interferon (IFN-I), indicating an antiviral response can provide developmental cues like those attributed to the bacterial microbiota (Kernbauer et al., 2014). Furthermore, colonization by MNV is protective in models of childhood enteric bacterial infections and hospital-acquired opportunistic infections (Abt et al., 2016; Neil et al., 2019). Like symbiotic bacteria, MNV triggers adverse outcomes when introduced into a susceptible background. Th1 cytokines induced by MNV cause disease in animal models of IBD (Basic et al., 2014; Bolsega et al., 2019; Cadwell et al., 2010; Matsuzawa-Ishimoto et al., 2017), and the inflammatory gene expression induced by MNV exacerbates bacterial sepsis (Kim et al., 2011). Similarly, MNV and orthoreovirus strain type 1 Lang (T1L), which causes asymptomatic or mild gastrointestinal infection in humans, induces a Th1 response triggering loss of tolerance to gluten in a mouse model of celiac disease (Bouziat et al., 2017, 2018). Rhesus rotavirus (RRV) accelerates autoimmunity in non-obese diabetic mice following recognition by plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) (Drescher et al., 2015; Pane and Coulson, 2015). These observations may explain the epidemiological association between related viruses and disease in humans (Axelrad et al., 2018, 2019; Bouziat et al., 2017; Pane and Coulson, 2015).

Despite evidence that eukaryotic viruses in the gut have beneficial and detrimental effects by influencing immune development, a broader characterization of the immune effects of viral exposure is lacking. Administration of antiviral drugs to mice reduces intraepithelial lymphocyte numbers, cytokine levels, and resilience to intestinal injury through IFN-dependent and - independent mechanisms, suggesting that enteric viruses provide a broad range of homeostatic cues to the host (Broggi et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2016). However, the contribution of individual viruses is unclear.

Here, we conducted an exhaustive cross-comparison of the host response and infection dynamics of representative enteric viruses. Almost all viruses we examined evoked responses in the absence of disease manifestations, and many displayed enhanced capacity to persist in GF mice. Mono-association experiments revealed long-lasting and specific effects of individual viruses on immune cell populations and gene expression. Comparisons with bacteria-associated mice and studies defining the host response to individual bacterial species revealed overlapping yet distinct consequences of viral exposure. These results provide an overview of the immune space occupied by the enteric virome and highlight the wide range of responses that can occur following asymptomatic viral infection.

RESULTS

Colonization and bacterial dependence of enteric viruses following a natural route of inoculation

Studies of viral commensalism are hampered by the lack of established animal models. Established models often involve peritoneal or intravenous inoculation of the virus to circumvent local defenses or employ inhibition of antiviral pathways using knockout mice. Another challenge comes from the capacity of segmented filamentous bacterium (SFB) and murine astrovirus, both of which are widespread in institutional vivaria, to inhibit intestinal viral infections (Ingle et al., 2019; Shi et al., 2019). As such, bacterial or viral microbiota may have prevented investigation of certain viruses. These concerns motivated us to perform a side-by-side comparison of viral burden following oral inoculation of conventional, specific-pathogen-free (SPF) and GF mice with different enteric viruses.

We selected a panel of 10 enteric viral strains encompassing six families comprising Groups I, II, III, and IV of the Baltimore classification: two adenoviruses (MAdV1 and 2), an astrovirus (MuAstV), two caliciviruses (MNV CR6 and CW3), a picornavirus (CVB3), two parvoviruses (MVMi and MVMp), and two reoviruses (T1L and RRV). Our current understanding of their tissue tropism is summarized in Table S1. However, a detailed time course of infection and corresponding immune response in wild-type C57BL/6 mice following oral inoculation has not been defined for most. Conventional and GF mice inoculated with each virus were monitored for signs of disease and virus in stool and blood over a 2-month period. We could not recover infectious particles from MNV CW3 at peak of infection and found that the contents of stool inhibited detection of infectious viral particles, which prevented the use of plaque assays in all conditions (Fig. S1A). A related concern is that detection of infectious particles may be prone to false-negative results once neutralizing antibodies are produced, especially for blood samples. Therefore, we used qPCR, which is a sensitive assay to monitor viral clearance and facilitate comparisons between viruses. T1L and RRV were exceptions for which we used plaque assays, as the multi-segmented nature of the Reoviridae genome confounds quantification by qPCR.

Evidence of disease symptoms, such as diarrhea and hunched posture, were absent in almost all mice, and evaluation of intestinal tissues harvested 28 days post-inoculation (dpi) did not yield histological abnormalities (Fig. S1B–C). Mice inoculated with CVB3 were the only animals that displayed disease. Despite administering the lowest dose of virus required for seroconversion, ~ 50% of conventional and GF mice did not survive (Fig. S1D). Considering our focus on commensalism, we excluded CVB3 from subsequent studies. We detected replication of each of the remaining nine viruses in both conventional and GF mice (Fig. 1A–B). Although unable to detect RRV in stool (Fig. S1E), we detected anti-RRV neutralizing antibodies, indicating infection (Fig. 1C). Potential differences in antibody titer between conditions could be due to the role of bacteria in regulating humoral responses to RRV (Uchiyama et al., 2014). MAdV1, MuAstV, and MVMi genomes were detected in blood at two or more timepoints. Generally, the presence of these viruses in blood predicted their long-term detection in stool (30 dpi).

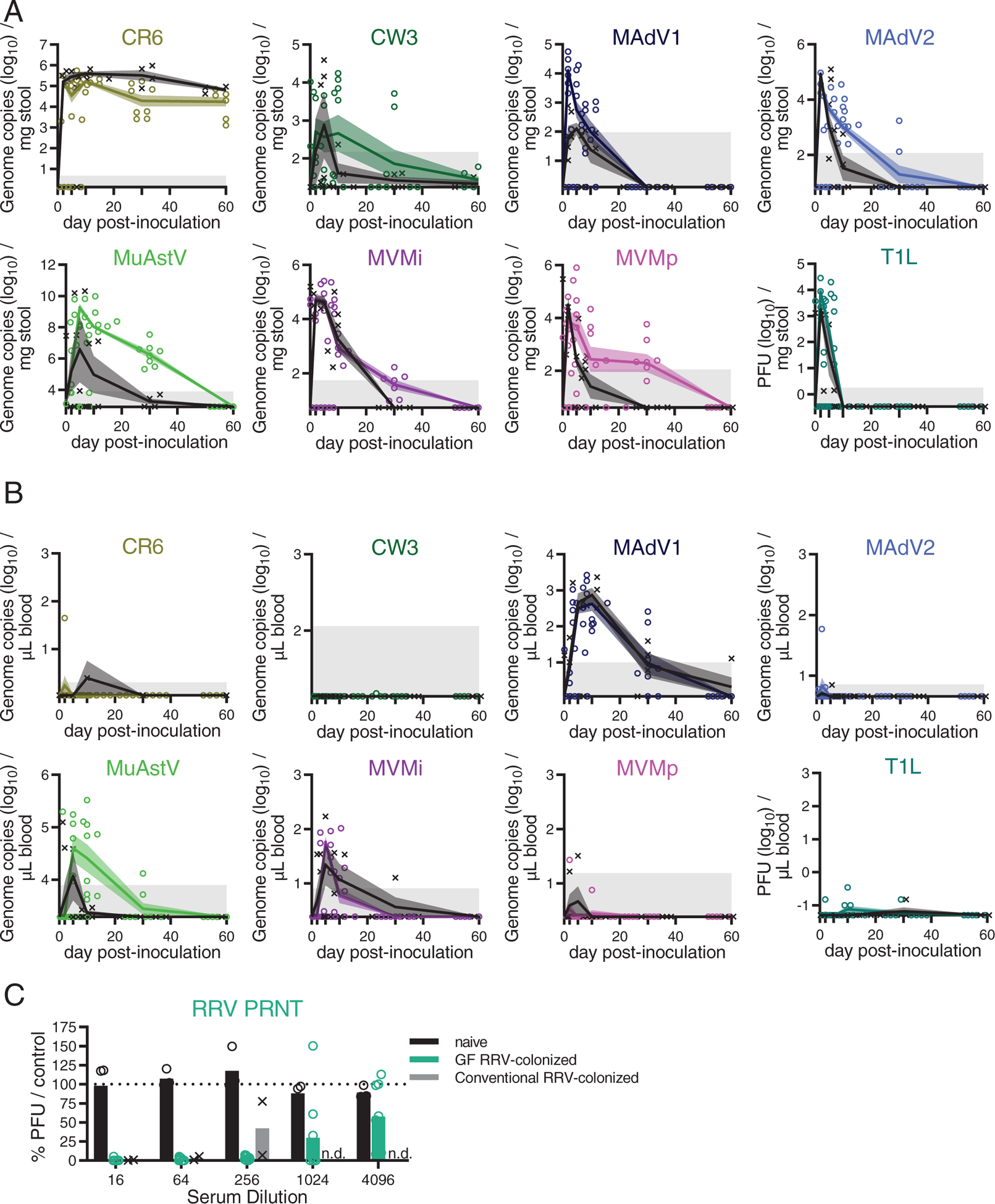

Figure 1. Colonization and Bacterial Dependence of Enteric Viruses Following the Natural Route of Infection.

(A-B) Stool (A) and blood (B) collected over time from conventional (black) and GF mice (colored) inoculated with indicated viruses. Viral titers were quantified by plaque assay or qPCR. Symbols indicate individual samples. Lines pass through the mean at each timepoint. Shadowed areas indicate SEM. Gray areas indicate limit of detection. N = 4–8 mice per condition, combined from two independent experiments.

(C) Neutralizing antibodies in sera of mice 28 days post-inoculation (dpi) with RRV quantified by a plaque-reduction neutralization assay. Reduction in plaque-forming units (PFU) shown as percent relative to control sera from naïve conventional mice. Results are from 3–9 mice from three independent experiments. n.d.: not determined.

Observations made with antibiotic-treated and GF mice indicate the microbiota is required for optimal infection and transmission by certain enteric viruses (Baldridge et al., 2015; Kane et al., 2011; Kernbauer et al., 2014; Kuss et al., 2011), which we confirmed for MNV CR6. Surprisingly, most of the other viruses displayed similar or enhanced infection of GF mice, including the closely related MNV CW3 (Fig. 1A–B and S1F). This finding can be explained by a recent study showing bacterial depletion inhibits MNV CW3 infection in one region of the intestine while promoting viral replication in another (Grau et al., 2020). It also is possible GF mice are more susceptible to viruses because some aminoglycoside antibiotics used to deplete bacteria from mice elicit an antiviral IFN-I response (Gopinath et al., 2018). MadV1 and T1L reached higher peak titers in GF mice, but the microbiota did not affect the time to clearance (Fig. S1F). In contrast, MNV CW3, MAdV2, MVMi, and MVMp produced similar peak titers but displayed prolonged viral shedding in stool of GF mice (Fig. S1F). MuAstV was not uniformly detectable in the stool of conventional mice, perhaps reflecting pre-existing immunity (Yokoyama et al., 2012), but consistently high levels of viral RNA were recovered from GF mice (Fig. 1A–B). Collectively, these data show exposure to enteric viruses can occur without disease, and many of the viruses chosen for study displayed improved colonization in GF mice. These results, summarized in Table 1, were used to design and interpret the subsequent analysis of the immune response.

Table 1: Summary of characteristics of viruses.

Taxonomic classification at family and genus level, Baltimore classification, virus strain names with their abbreviations (Abbr.), and summary of results following inoculation of germ-free (GF) mice from Fig. 1 and S1 for each virus used in this study. Viruses were categorized as persistent if viral nucleic acid was detected in at least 75% of infected mice at 30 dpi in blood or stool. Viremia is defined as presence of viral nucleic acid in the blood of at least 75% infected mice in at least one time point. The ability to cause pathology is based on appearance of histological or macroscopic signs of disease. n.d.: not determined.

| Viral family (-viridae) | Viral genus (-virus) | Baltimore classif. (genome) | Virus | Strain | Abbr. | Persistent | Viremia | Cause pathology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adeno- | Mastadeno- | I (dsDNA) |

Murine Adenovirus | MAdV1 | MAdV1 | Yes | Yes | No |

| MAdV2 | MAdV2 | No | No | No | ||||

| Astro- | Mamastro- | IV (ssRNA+) |

Murine Astrovirus | NYU1 | MuAstV | Yes | Yes | No |

| Calici- | Noro- | IV (ssRNA+) |

Murine Norovirus | CR6 | CR6 | Yes | No | No |

| CW3 | CW3 | No | No | No | ||||

| Picorna- | Entero- | IV (ssRNA+) |

Coxsackie virus B3 | H3 | CVB3 | n.d. | n.d. | Yes, lethal |

| Parvo- | Protoparvo- | II (ssDNA) |

Minute virus of mice | Immunotr opic | MVMi | Yes | Yes | No |

| Prototype | MVMp | Yes | No | No | ||||

| Reo- | Orthoreo- | III (dsRNA) |

Mammalian orthoreovirus 1 | Type 1 Lang | T1L | No | No | No |

| Rota- | Simian rhesus rotavirus | RRV | RRV | No | No | No |

A reductionist approach to evaluate responses to viral exposure

To determine whether asymptomatic viral infections are associated with sustained immunological changes, we conducted immune-profiling of GF mice infected with each virus, a reductionist method similar to that used to define the immunomodulatory activity of individual bacterial species (Geva-Zatorsky et al., 2017; Sefik et al., 2015; Tan et al., 2016). Although single infections potentially exaggerate the effect of an individual virus, this approach circumvents concerns about redundancy between viruses in our panel and viral and bacterial members of the microbiota.

We inoculated GF mice perorally with each virus and confirmed infection at 5 dpi. At 28 dpi, six intestinal and extra-intestinal tissues were harvested for analyses by multicolor flow cytometry: colonic and small intestinal lamina propria (cLP and siLP), small intestinal intraepithelial leukocytes (IELs), mesenteric lymph nodes (mLNs), spleen, and lungs. Each sample was analyzed for 32 immune cell subsets based on cell-surface markers and transcription factors. Lymphocyte subsets and functionality were further defined by intracellular staining of six effector cytokines (GRANZYME-B, IL-4, IL-10, IL-17a, IL-22, and IFN-γ) (Fig. S2). Whole colon and small intestine homogenates were subjected to RNA sequencing. These samples were compared with those prepared in parallel from control GF mice and GF mice colonized with a minimal defined flora (MDF) consisting of a consortium of 15 bacterial strains representing the murine gut microbiota (Brugiroux et al., 2016). These experiments resulted in 462 flow cytometry samples, from which we obtained 21,619 individual immunophenotypes, and 127 transcriptomes.

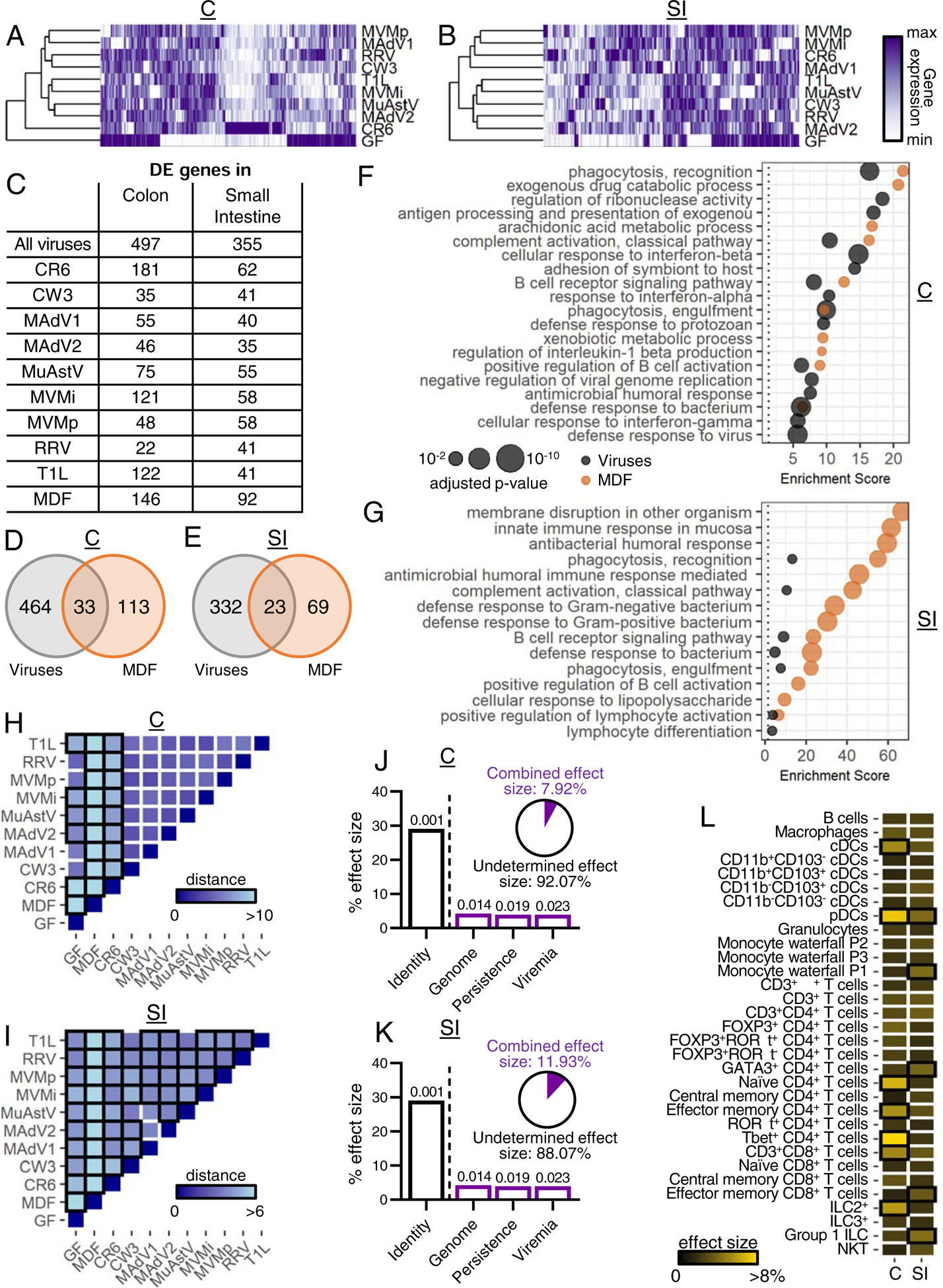

Enteric viruses alter immune cell populations

Fold changes in immune cell populations relative to GF status are shown in Table S2 and heatmaps in Figure 2A (cLP and siLP) and Figure S3A (IELs, mLNs, lung, and spleen). Viral infection promoted expansion or contraction of multiple populations, especially in the cLP and siLP. Generally, viruses tended to induce more changes in immune cell composition in tissues where they preferentially replicate (Fig. S3B). Although each virus had a unique effect, common population changes were altered in a unidirectional manner; we rarely observed a population that increased with one virus and decreased with another. Viruses were observed to modulate as many immune subsets as MDF bacterial microbiota control (Fig. 2A).

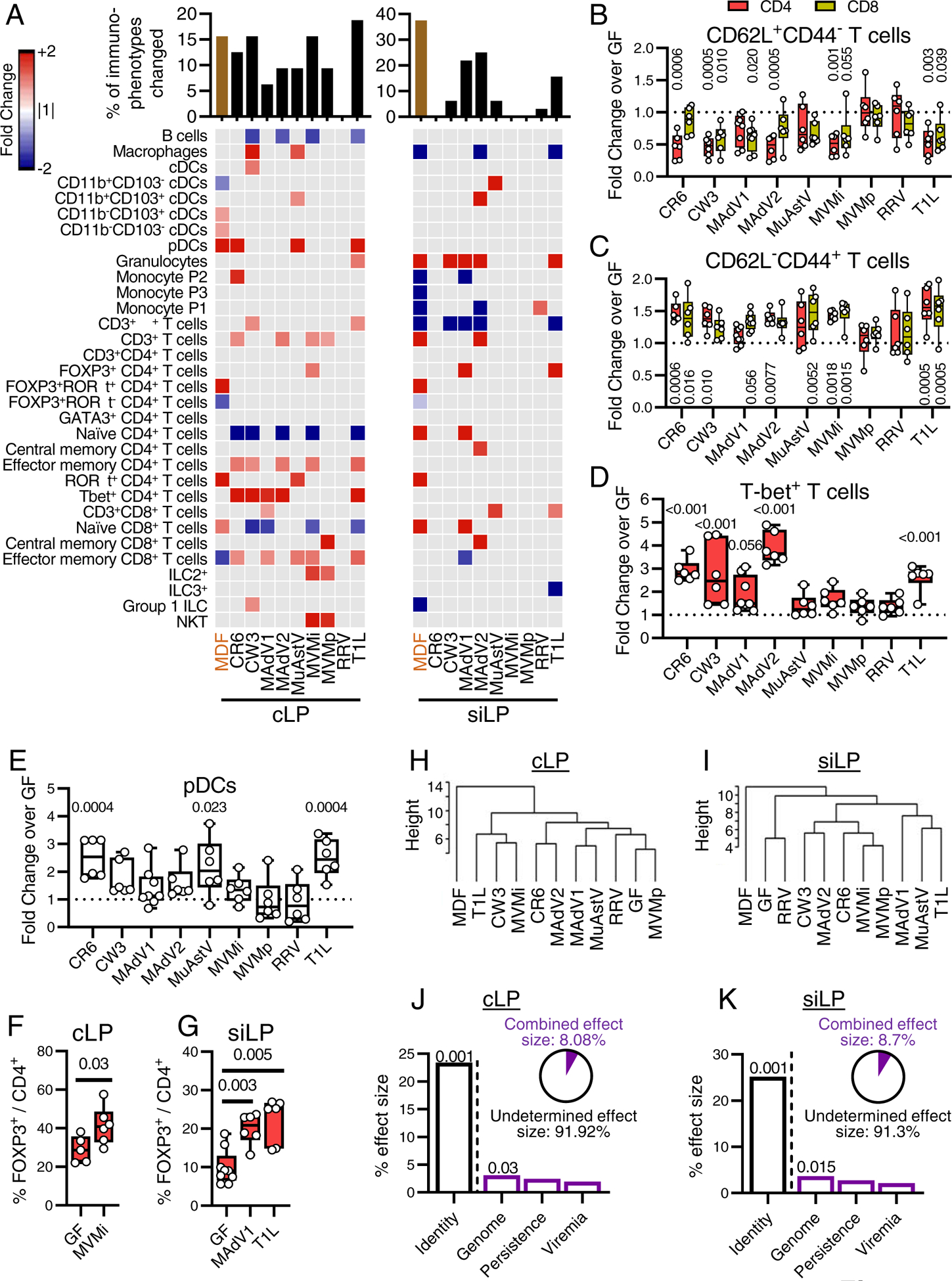

Figure 2. Enteric Viruses Promote Changes in Immune Cell Populations.

(A) Heatmap showing average fold-change for cLP and siLP immune populations identified by flow cytometry (gating strategy in Fig. S2) for mice inoculated with individual viruses or MDF relative to GF controls with an FDR<0.1. Gray: FDR>0.1. Bar graph on top represents the proportion of immune populations with an FDR<0.1 and a fold change>1.5.

(B-E) Fold changes of CD62L+CD44− (B), CD62L−CD44+ (C), T-bet+ (D), and pDCs (E) in the cLP CD4+ (B-D), CD8+ (B-C), or CD45+ (E) populations. Each dot represents a single sample. (F-G) Percentage of Foxp3+ cells in the cLP (F) or siLP (G) CD4+ populations. Each dot represents a single sample.

(H-I) Hierarchical clustering based on cLP (H) and siLP (I) population frequencies.

(J-K) Effect size determined by db-RDA of viral characteristics: identity, genome, persistence, and viremia as explanatory variables of the cLP (J) and siLP (K) population frequency variance. Pie charts represent combined effect size of genome, persistence, and viremia.

Statistical significance was calculated by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunn’s post-hoc analysis and corrected for multiple testing by the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure (A-E) or by non-parametric Mann-Whitney test (F-G).

See also Figures S2–3 and Table S2.

Our results confirmed several anticipated outcomes, validating our approach. We observed a decrease in CD4+ and CD8+ naïve T cells (CD62L+CD44−) and a corresponding increase in CD4+ and CD8+ effector memory T cells (CD62L−CD44+) (Fig. 2B–C). We also detected an increase in T-bet+ T cells, indicative of a Th1 response (Fig. 2D) (Szabo et al., 2000). Macrophages increased in the cLP in response to MNV CW3, consistent with effects in conventional mice inoculated with this virus (Winkle et al., 2018). Furthermore, at least three enteric viruses induced an expansion of colonic pDCs (Fig. 2E), a population strongly modulated by the bacterial microbiota (Geva-Zatorsky et al., 2017). Despite this commonality, the overlap between mice inoculated with viruses and MDF was limited. One of the most prominent effects of MDF was the induction of FOXP3−RORγt+ CD4+ Th17 cells, but the effect of viral exposure on this population was negligible (Fig 2A). Instead, we observed an increase of FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells (Tregs) by MVMi in the cLP (Fig. 2F) and by T1L and MAdV1 in the siLP (Fig. 2G). The absence of RORγt within this population (Fig. 2A) suggests that these Tregs are distinct from bacterial-induced peripheral Tregs (Sefik et al., 2015).

We used hierarchical clustering to define the relative similarity of the overall immune cell composition between conditions (Fig. 2H–I). In both cLP and siLP, MDF was in a clade distinct from individual viruses and the GF control. Viruses did not segregate based on taxonomical relationships, suggesting the immunomodulatory properties observed were marginally intrinsic to a viral family or genus. To quantify how virus-associated variables explain variance between samples, we conducted a distance-based redundancy analysis (db-RDA) based on shared characteristics (Table 1): genome type (DNA versus RNA), capacity to persist, defined as detectable virus 30 dpi in blood or stool (persistence), and detectable virus in blood (viremia). We included the identity of the virus (identity) as a benchmark variable. Indeed, identity was the major explanatory variable, accounting for almost 25% of the variance, supporting the conclusion that individual viruses promote substantially distinct immunomodulatory outcomes (Fig. 2J–K). The second strongest explanatory variable was genome, although the effect size was modest. The combined effect size of the genome, persistence, and viremia variables left much of the variance unexplained.

Among the other tissue compartments examined, mLNs and lungs displayed the greatest changes following viral infection (Fig. S3A). Like the intestinal lamina propria, we observed, to a lesser extent, a decrease in naïve and an increase in effector memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the lungs. Identity was the dominant explanatory variable in these tissues (Fig. S3C). Together, these data indicate that enteric viruses influence the immune cell compositions, much of which is virus strain-specific.

Enteric viruses increase cytokine production by immune cells

Cytokine production was assessed following PMA-ionomycin stimulation of single cell suspensions from each tissue (Fig. 3A, S4A–B, and Table S2). Inoculation with several viruses led to increases in cLP T cells producing the Th1 cytokine, IFN-γ (Fig. 3B), correlating with increases in T-bet+ lymphocytes (Fig. S4C). Increased IL-17+ CD4+ T cells was specific to MDF- colonized mice (Fig. 3A). IL-22 is a tissue regenerative cytokine that mediates the protective effect of MNV in models of intestinal injury and bacterial infection (Abt et al., 2016; Neil et al., 2019). Most viruses enhanced IL-22 production by a variety of cLP and siLP lymphoid cells including CD4+ T cells, γδ+ T cells, and ILCs (Fig. 3A). Six and five of the viruses increased the total proportion of IL-22+ cells in the cLP and siLP, respectively (Fig. 3C–D). IL-22 production correlated with the proportion of granulocytes and mononuclear phagocytes in the cLP (Fig. S4D). The increase in IL-22+ cells was evident in mice inoculated with non-persistent viruses, most notably T1L, indicating alterations in the function of immune cells can be sustained (Fig. 3A).

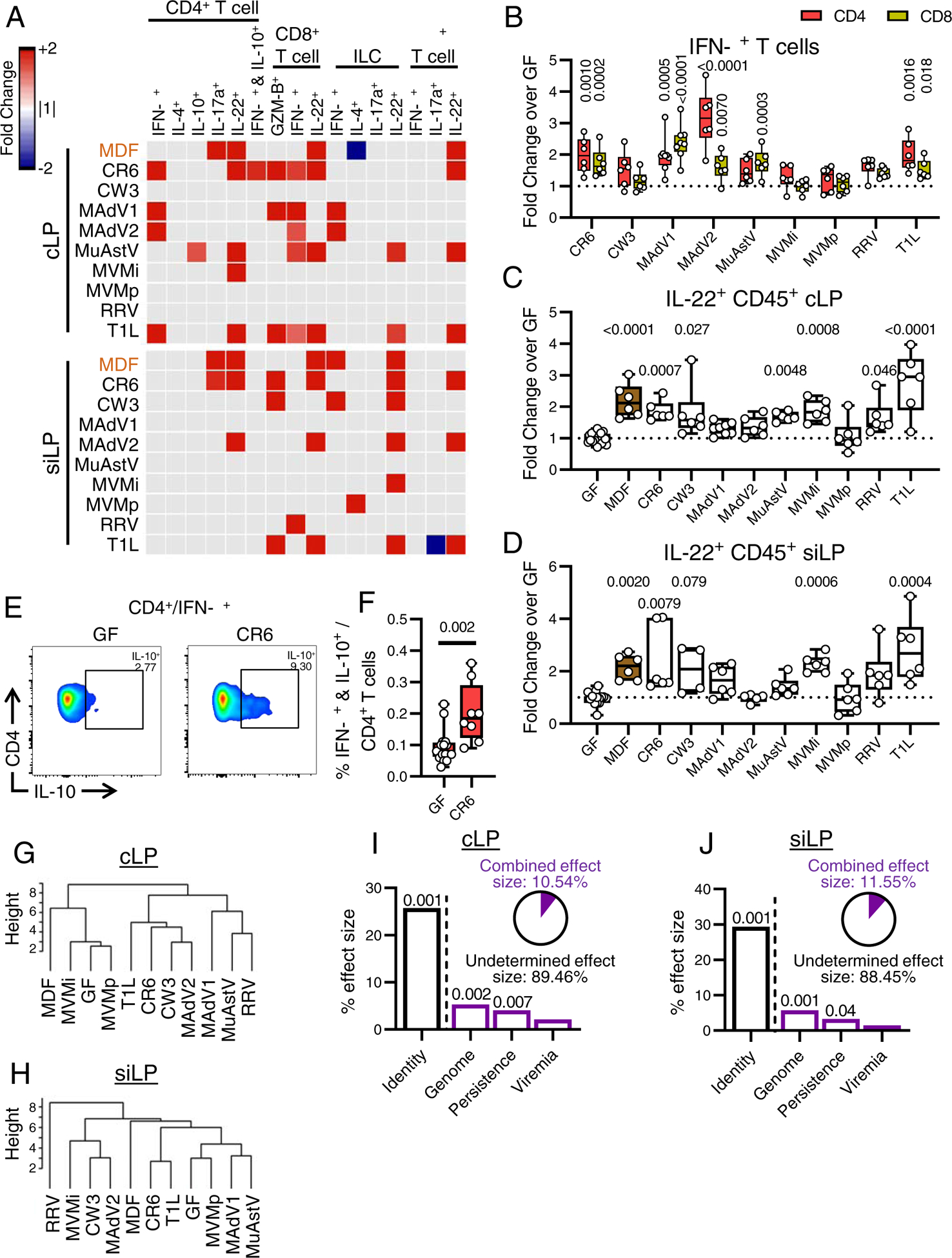

Figure 3. Enteric Viruses Increase Cytokine Production by Immune Cells.

(A) Heatmaps showing average fold-change for cytokine-producing immune cells in cLP and siLP identified by flow cytometry for mice inoculated with the viruses shown or MDF relative to GF controls with an FDR<0.1. Gray: FDR>0.1.

(B-D) Fold-changes of IFN-γ+ (B) and IL-22+ (C-D) cells in the cLP CD4+ and CD8+ (B), cLP CD45+ (C), and siLP CD45+ (D).

(E-F) Representative dot plot (E) and percentage of IFN-γ+IL-10+ cells in the cLP CD4+ T cell population (F).

(G-H) Hierarchical clustering of the different microbial associations based on the cLP (G) and siLP (H) cytokine production frequencies.

(I-J) Effect size determined by db-RDA of viral characteristics: identity, genome, persistence, and viremia as explanatory variables of the cLP (I) and siLP (J) cytokine-producing immune cell frequency variance. Pie charts represent the combined effect size of genome, persistence, and viremia.

Statistical significance was calculated by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunn’s post-hoc analysis and corrected for multiple testing by the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure (A-B), by Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post-hoc analysis (C-D), or by non-parametric Mann-Whitney test (F).

Although we did not observe common changes in cytokine production in other tissue compartments as we observed for IL-22 in the lamina propria, we noted several virus strain-specific changes (Fig. S4A). As an example, IFN-γ+IL-10+ CD4+ T cells (Tr1 cells), a T-helper subset with regulatory functions (Häringer et al., 2009), was increased in mice infected with persistent MNV strain CR6 in cLP and mLN (Fig. 3E–F).

Hierarchical clustering of cytokine production in cLP and siLP cells showed virus-infected mice did not form clades independent of GF and MDF mice as obviously as they did when analyzing immune cell populations based on cell-surface markers and transcription factors (Fig. 3G–H). As with the prior analyses, viruses from the same families did not uniformly cluster together, and the major explanatory variables for cytokine production were identity, followed by genome (Fig. 3I–J, S4E). Thus, these results indicate that virus-infected mice display increases in cytokine-producing immune cells that are both common and virus-strain specific.

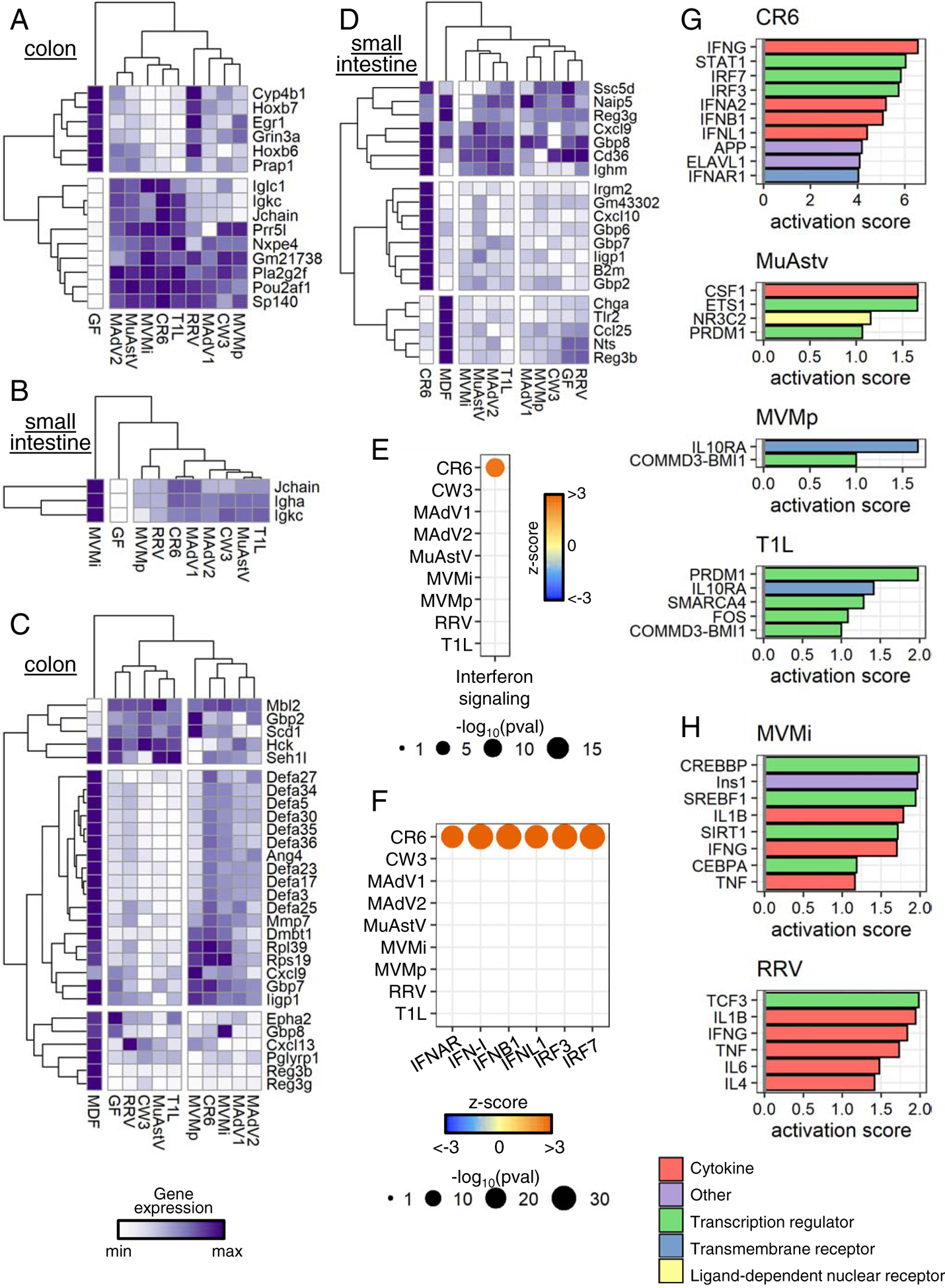

Intestinal transcriptome of virus-infected mice

In the colon and small intestine, 497 and 355 genes, respectively, displayed differential expression (DE) in at least one virus-infection condition compared with GF mice (≥ 2-fold, p value ≤ 0.01) (Fig. 4A–C, Table S3A–D). MNV CR6 and MuAstV1, the two viruses displaying the highest shedding in the stool at this time point (Fig. 1A), were detectable in both the small intestine and colon (Table S3E). 146 and 92 genes in the colon and small intestine displayed DE in MDF-colonized mice and minimally overlapped with the virus-induced expression changes (Fig. 4D–E, Table S3C–D). Similar to immune cell alterations, viruses tended to induce more gene expression changes at the site of preferential replication (Fig. S5A). Gene ontology (GO) analyses showed viral infection influenced a range of immune-related pathways, especially in the colon (Fig. 4F–G). Viral infection was associated with antiviral immunity pathways, such as defense response to virus and cellular response to interferon-beta. Enrichment for genes associated with IFN-γ is consistent with the flow cytometry data identifying a Th1 response. Both MDF and viruses were associated with B cell activation and bacterial response pathways. Enrichment of DE genes involved in metabolic processes was specific to MDF, perhaps reflecting the nutrient exchange between host and bacteria.

Figure 4. Intestinal Transcriptome of Virus-Infected Mice.

(A-B) Heatmaps showing DE genes (|average fold-change over GF|≥2 and unadjusted p- value≤0.01) in the colon (A) and small intestine (B) of virus-infected mice compared with GF mice. C: colon; SI: small intestine.

(C) Number of DE genes in colon and small intestine for each condition compared with GF mice.

(D-E) Venn diagrams depicting the number and overlap of DE genes in all virus-infected and MDF-associated mice in colon (D) and small intestine (E).

(F-G) Top 15 most highly enriched biological process GO terms for DE genes in the colon (F) and small intestine (G) of virus-infected and MDF-associated mice.

(H-I) Heatmaps showing Euclidean distances between group centroids of DE genes in colon (H) and small intestine (I) comparing each condition. Boxes outlined in black indicate significant differences (PERMANOVA<0.05).

(J-K) Effect size determined by db-RDA of virus characteristics as explanatory variables of the DE gene variance in the colon (J) and small intestine (K). Pie charts represent the combined effect size of genome, persistence, and viremia.

(L) Effect size determined by db-RDA of immune population frequencies from Figure 2 on DE gene variance in colon and small intestine. Boxes outlined in black indicate p-value<0.05.

Permutational multivariate analysis of the variance after principal component analysis (PCA) confirmed transcriptional responses to viruses differed significantly from GF and MDF conditions (Fig. 4H–I and S5B–C). Major explanatory variables were again identity followed by genome (Fig. 4J–K). Because much of the transcriptome variance was unexplained, we determined whether immune cell composition and cytokine production (described in Figs. 2 and 3) correlated with differences in gene expression between conditions. DC and T cell subsets were major explanatory variables and included cell types with recognized functions in antiviral responses such as Tbet+ CD4+ T cells and pDCs (Fig. 4L). Among the cytokines tested, only IL-22 was a significant explanatory parameter (Fig. S5D), likely reflecting the role of this cytokine in coordinating antimicrobial gene expression (Keir et al., 2020). Collectively, these results correlate well with our flow cytometry data and reveal responses common to multiple viruses, while also underscoring the importance of investigating the immune effects of individual virus strains.

Intestinal gene expression common and specific to individual viruses

We observed 15 and three DE genes in the colon and small intestine, respectively, that were shared by at least half of the viruses studied, including immunoglobulin genes Igha, Igkc, Iglc1, Jchain, and Pou2af1 (Fig. 5A–B). This finding is consistent with the increased expression of genes associated with B cell activation (Fig. 4F–G) as well as previous findings that MNV CR6 enhances local and systemic antibody production in GF mice and that IgA production is frequently observed during enteric viral infections (Blutt and Conner, 2013; Kernbauer et al., 2014).

Figure 5. Intestinal Gene Expression Common and Specific to Individual Viruses.

(A-B) Heatmaps displaying normalized expression values of DE genes (average fold-change over GF≥2 and unadjusted p-value≤0.01) modulated by at least five viruses in colon (A) and small intestine (B).

(C-D) Heatmaps displaying normalized expression values of DE genes (average fold-change over GF≥1.5 and unadjusted p-value≤0.01) annotated in GO:0050829, GO:0050830, and GO:0061844 in colon (C) and small intestine (D).

(E-F) DE genes from colonic transcriptomes of virus-infected mice analyzed by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Results from Canonical Pathway Analysis (E) and Upstream Regulator Analysis (F) relating to IFN signaling are shown.

(G-H) Colonic (G) and small intestinal (H) DE genes analyzed by IPA for upstream regulators. Top 10 upstream regulators for each virus with an activation score>1 are depicted.

See also Figure S6.

Increased expression of antimicrobial genes is a hallmark of intestinal colonization by symbiotic bacteria (Geva-Zatorsky et al., 2017; Hooper et al., 2001). We examined expression of antimicrobial genes during viral infection by constructing an antimicrobial gene set in which genes annotated in GO:0050829 (defense response to Gram-negative bacterium), GO:0050830 (defense response to Gram-positive bacterium), and GO:0061844 (antimicrobial humoral immune response mediated by antimicrobial peptide) were pooled. Expression of numerous antimicrobial genes was increased in virus-infected mice compared with GF controls (≥ 1.5-fold change, p ≤ 0.01) (Fig. 5C–D). However, the overall response was not as strong as that induced by MDF. Nonetheless, there were transcripts induced exclusively by viruses, including mannose-binding protein C (Mbl2) and the interferon-inducible GTPases, Iigp1, Irgm2, and Gbp2.

MNV CR6 but not MNV CW3 fortifies the intestinal barrier by inducing a local IFN-I response (Kernbauer et al., 2014; Neil et al., 2019). IFN-I (IFN-α and -β) and type III interferon (IFN-λ) are antiviral cytokines produced in response to viral nucleic acid that evoke a similar set of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs), which we collectively term here as an “IFN signature”. Consistent with our previous findings, inoculation with MNV CR6 but not MNV CW3 was associated with an IFN signature (Fig. 5E). Surprisingly, no other virus from our panel yielded an IFN signature, despite high levels of viral nucleic acid produced by some, such as MuAstV. Moreover, only MNV CR6 was associated with increased transcription downstream of ISG regulators (Fig. 5F). We confirmed expression of representative ISGs Isg15, Ifit1, and Oas1a was increased only in mice colonized with MNV CR6 (Fig. S6A).

In contrast to IFN-I, IL-22 should regulate DE genes for multiple viruses based on its effect size on transcriptional variance (Fig. S5D). We used Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) to determine whether transcripts altered in the intestine of Il-22−/− mice (Gronke et al., 2019) were differentially regulated in virus-infected mice. This analysis confirmed that most virus-infected mice produced an IL-22 signature. (Fig. S6B–C).

We used Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) to identify additional regulators in the following categories: cytokine, ligand-dependent nuclear receptor, transmembrane receptor, transcript regulator, and other. In the colon, four viruses were associated with such regulators. IFN-related factors were the main regulators associated with MNV CR6, whereas MuAstV, MVMp, and T1L upregulated other pathways (Fig. 5G). PRDM1, also known as BLIMP1, is a regulator of terminal B-cell differentiation (Shaffer et al., 2002) and influenced transcriptional responses to MuAstV and T1L, supporting a role for viruses in B cell development. The association of MuAstV and macrophage differentiation factor CSF-1 is consistent with the observation that MuAstV-colonized mice displayed an increase in cLP macrophages (Fig. 2A). In the small intestine, genes induced by pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IFN-γ, and TNF-α were enriched in mice infected with either MVMi or RRV (Fig. 5H). Other factors identified by this approach have been implicated in immunity in some settings. For example, insulin (Ins1), which was associated with MVMi infection, is involved with IFN-γ in a feedback loop to promote CD8+ T cell responses to murine cytomegalovirus infection (Šestan et al., 2018).

Lastly, we compared our results with previously published studies examining transcriptional response to MNV CR6, MNV CW3, and T1L in conventional mice (Bouziat et al., 2017, 2018; Lee et al., 2019) Using a previously described GSEA-based approach (Godec et al., 2016), we found that virus-induced gene sets in GF mice were enriched in the transcriptome of conventional mice infected by the same viruses (Fig. S6D–F). Given that there were considerable differences in how the datasets were generated in each study, these results suggest certain aspects of the transcriptional signature are similar across conditions. However, we observed an interesting exception. Our findings with MNV CR6 in GF mice displayed an opposite direction of regulation in the small intestine on 35 dpi with the same strain in conventional mice from Lee et al., a discrepancy potentially explained by the higher viral burden at this time point when comparing conventional and GF mice (Fig. 1A). Such differences in MNV CR6 burden could lead to differential levels or activity of NS1, a secreted viral immunomodulatory protein (Lee et al., 2019).

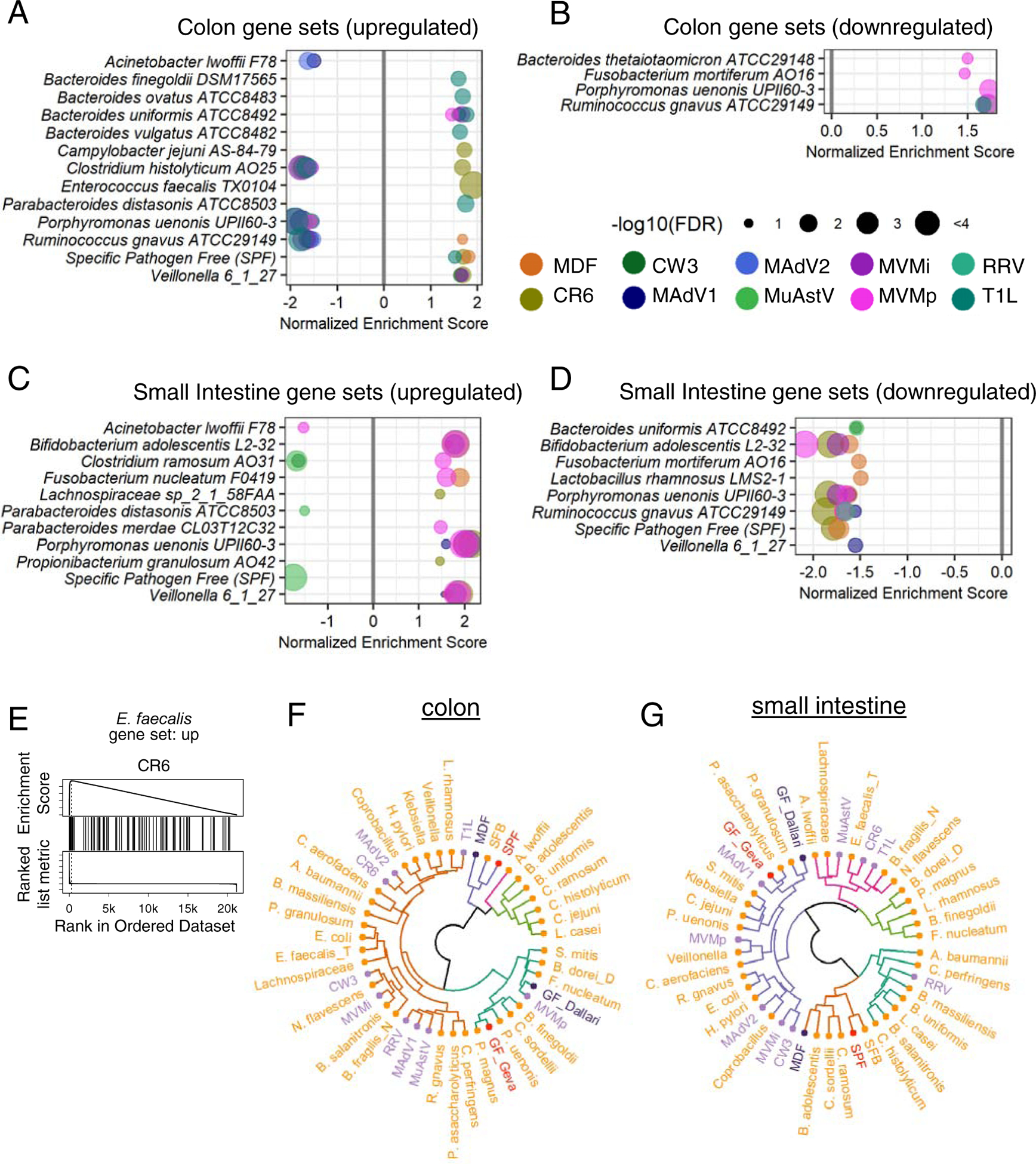

Intestinal transcriptomes of virus-infected mice are enriched for bacterial microbiota gene signatures

We used a GSEA strategy to compare the transcriptome of virus-infected mice with gene-expression signatures of mice monocolonized with 53 individual species of the bacterial microbiota (Geva-Zatorsky et al., 2017) (Fig. 6A–D, Table S4). Colonic transcripts of MDF-colonized mice in our study were positively enriched for genes upregulated in microbiota-replete conditions (conventional SPF mice) (Geva-Zatorsky et al., 2017), indicating concordance in the positive controls (Fig. 6A). Similarly, the small intestinal transcriptome of MDF-colonized mice displayed a negative enrichment score for genes downregulated in conventional SPF mice (Fig. 6D). Twenty of the 53 bacterial species displayed a relationship with one or more viruses using this approach. We identified 91 virus-bacterium pairs, with 60 displaying the same directionality of regulation (i.e., positive enrichment of upregulated bacterial gene sets and negative enrichment of downregulated bacterial gene sets in virus-associated transcripts) (Fig. 6A–D). Certain bacterial gene sets displayed exclusive pairing with one virus, as observed with several Bacteroides and Parabacteroides species and T1L in the colon. This consistent pairing between T1L and the Bacteroidales order suggests this virus induces a similar reaction to colonization by this prototypical group of commensal bacteria. The MNV CR6-induced gene set also was paired with multiple bacterially upregulated gene sets in the colon, including a particularly strong enrichment for the Enterococcus faecalis signature (Fig. 6E).

Figure 6. Intestinal Transcriptomes of Virus-Infected Mice Are Enriched for Bacterial Microbiome Gene Signatures.

(A-D) Colonic (A-B) and small intestinal (C-D) transcriptomes from virus-infected mice compared with gene expression signatures of bacterially colonized mice by GSEA. Gene sets upregulated following colonization by bacteria are depicted in A and C; downregulated gene sets are depicted in B and D.

(E) GSEA plot showing enrichment of the E. faecalis upregulated gene set in the colonic transcriptome of mice infected with MNV CR6.

(F-G) Hierarchical clustering of immune population frequencies described in Table S5. Purple: viruses; dark purple: MDF and GF from this study; orange: bacteria; pink: conventional SPF and GF from Geva-Zatorsky et al.

When comparing flow cytometry data with results gathered using mice monocolonized with bacteria, due to differences in gating strategies and markers used to identify cell types, we restricted our comparison to 16 immune cell subsets that were quantified in a similar manner across the datasets (Table S5). Hierarchical clustering using the z-scores of the two datasets indicated that the GF groups from both datasets clustered together, as did MDF from our study and SPF from Geva-Zatorsky et al (Fig. 6F–G). Most bacteria and viruses clustered together with GF or in neighboring clades distinct from MDF and SPF, suggesting the contribution of a specific bacterium or virus, when present alone, accounts for only a modest fraction of the total microbiota-dependent effects on immune cell composition. Viruses were interspersed among bacteria rather than clustered together in a single clade, indicating virus-induced changes to immune cell frequencies does not reflect a uniform immunological response to viruses distinct from that evoked by bacteria.

DISCUSSION

We investigated whether subclinical intestinal infections by eukaryotic viruses shape the mucosal immune system, as demonstrated for numerous bacterial members of the microbiota (Honda and Littman, 2012; Round and Mazmanian, 2009). Only one of 10 viruses chosen for study led to illness or death, allowing us to define the immune effects of nine viruses in the absence of disease. In the process of establishing virus infection models, we made several observations about the dynamics of infection. First, nucleic acid of several viruses remains detectable for a prolonged interval. Observations with measles virus infections indicate viral antigens and RNA can persist, even for viruses that do not establish latency or integrate DNA copies into the host genome (Griffin, 2020). For some viruses, this type of persistence could be mediated by immune evasion, as proposed for MNV (Lee et al., 2019; Tomov et al., 2017). Also, we found the microbiota had a strong effect on persistence. While antibiotic treatment hinders infection by some enteric viruses (Baldridge et al., 2015; Kernbauer et al., 2014; Kuss et al., 2011), our data showed not all viruses benefit from the presence of bacteria. An important future goal is to identify specific autochthonous viruses and bacteria in the gut that mediate resistance to viral infection in conventional mice (Ingle et al., 2019; Shi et al., 2019).

Our flow cytometric and transcriptional analyses support the hypothesis that asymptomatic infection by enteric viruses is consequential. Although each virus was associated with a unique immune profile, viral infection generally promoted maturation of T cells and Th1 polarization. Changes to lymphocyte populations may be antigen specific, and examination of B and T cell receptor diversity will be informative. Alternatively, bystander effects through cytokines such as IFNγ could mediate heterologous immune responses to unrelated infectious agents and food antigens (Barton et al., 2007; Bouziat et al., 2017). Non-classical lymphocytes with innate-like properties are present in the gastrointestinal tract and could contribute to such responses as well, such as the IL-22 signature we observed following infection by several of the viruses. Induction of IL-22, which is associated with intestinal homeostasis (Gronke et al., 2019; Keir et al., 2020). May offset damage caused by enteric viruses, thereby facilitating a commensal relationship. Laboratory mice display deficiencies in mature lymphocytes due to reduced exposure to microbes (Beura et al., 2016; Lin et al., 2020; Yeung et al., 2020). In this context, it is notable that wild mice and pet-shop mice, which have a more mature lymphocyte compartment, are seropositive for viruses closely related to those in our panel (adenovirus, MNV, parvovirus, reovirus, and rotavirus) (Beura et al., 2016). These common enteric viruses may contribute to immune maturation in the natural environment.

Precise tissue and cell tropism, which is only beginning to be resolved (Wilen et al., 2018), likely contributes to the differential immune responses we observed for taxonomically-related viruses. The nucleic acid composition of the viral genome (DNA versus RNA) contributed modestly but reproducibly to the variance, whereas viral dissemination and persistence did not appear to explain differences. Accordingly, one remarkable finding was that changes to immune cells and gene expression were readily observed in mice in which viral nucleic acid was no longer detectable. If this sustained effect of viruses translates to humans, then cross-sectional studies of patient cohorts would miss potentially meaningful exposures to viruses that occurred prior to disease onset. Longitudinal virome analyses of children genetically susceptible to T1D identified an inverse relationship between early life adenovirus and circovirus exposure with subsequent appearance of serum autoantibodies (Vehik et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2017). Thus, we advocate prospective and longitudinal sampling for virome-association studies when possible.

A comparison between our results and an analogous dataset gathered using bacterial monocolonized mice identified virus-bacterium pairs that stimulate overlapping responses. For example, E. faecalis and MNV CR6 shared a colonic gene expression signature, which increased our confidence in the approach because these two infectious agents also share the capacity to confer protection in the DSS model of intestinal injury (Kernbauer et al., 2014; Neil et al., 2019; Takahashi et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2014). Several of the bacteria that evoke an immune response overlapping with viruses are implicated in disease, such as Ruminococcus gnavus and Bacteroides vulgatus in IBD (Hall et al., 2017; Png et al., 2010; Rath et al., 1999). It will be interesting to test the role of the matching viruses in animal models in which disease is dependent on these bacteria (Bloom et al., 2011; Ramanan et al., 2014, 2016; Yu et al., 2020).

Our survey was restricted to a limited number of viruses and, does not capture the vast diversity of viruses found in humans. Although bacteria isolated from the human gut generally colonize GF mice, many medically important viruses display narrow species tropism or altered virulence when inoculated into mice. A broader survey of viruses will likely identify additional cell types and pathways influenced by viral infection. Another limitation is that we chose a single-infection approach to identify direct responses and avoid missing immune effects that overlap with the existing microbiota. This approach also enabled our in-silico comparison of virus-induced immune responses with those induced in mice monocolonized with bacteria.

We envision two situations in which our results can guide studies investigating how the enteric virome modulates immunity in the presence of bacteria. First, mice associated with defined flora can be used to assess the immune effects of individual bacteria within a complex community (Fischbach, 2018). This synthetic ecology approach could incorporate viruses with immunogenic potential from our panel to better reflect the complexity of the real-world microbiome. Second, we advocate testing the role of these and other viruses in animal models of inflammatory diseases, many of which are thought to be dependent on bacterial members of the microbiota. Although the Th1 response to MNV CR6 is inconsequential in wild-type C57BL/6 mice, mutation of IBD-susceptibility gene ATG16L1 sensitizes the intestinal epithelium to the otherwise subtle effect of viral infection (Cadwell et al., 2010; Matsuzawa-Ishimoto et al., 2017). Observations with MNV-infected mutant mice allowed us to identify homeostatic mechanisms involved in barrier integrity conserved in humans (Cadwell et al., 2008; Matsuzawa-Ishimoto et al., 2020). Thus, incorporating viruses into genetic disease models can reveal vital pathways that promote health.

Our findings indicate that eukaryotic viruses in the gut have unappreciated immunomodulatory capacity in addition to well-recognized roles as causative agents of gastroenteritis. The reaction to viral infection could be beneficial in the appropriate setting, as demonstrated by proof-of-principle experiments showing MNV and MuAstV strains administered prophylactically protect mice from enteropathogenic E. coli (Cortez et al., 2020; Neil et al., 2019). There is precedent for manipulation of the gut virome for therapeutic purposes. Oral poliovirus vaccine provides cross-protection against other pathogens, which has been used as a rationale to administer this attenuated virus instead of inactivated vaccine in polio-endemic regions (Upfill-Brown et al., 2017). Ongoing studies using animal models will enable future safety and efficacy assessments of virome-based interventions.

STAR Methods

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by Lead Contact, Dr. Ken Cadwell (ken.cadwell@nyulangone.org).

Materials Availability

All unique/stable reagents generated in this study are available from the Lead Contact with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement.

Data and Code Availability

The extensive datasets presented in this manuscript are made available in Tables S2–S5. The immunophenotypes are presented in Table S2C as frequencies of cell types and in Table S2B as fold changes relative to uninfected GF mice. Sequencing data are deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under BioProject accession number PRJNA706512, in the European Nucleotide Archive under BioProject accession number PRJEB43445, and in the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE168293.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Mice

GF C57BL/6J were bred in flexible-film isolators at the New York University Grossman School of Medicine Gnotobiotics Animal Facility. Absence of fecal bacteria was confirmed monthly by evaluating the presence of 16S DNA in stool samples by qPCR as previously described (Kernbauer et al., 2014). For experiments, GF mice were housed in Bioexclusion cages (Tecniplast) with access to sterile food and water. Conventional C57BL/6J and Rag1−/− mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Animals were monitored under care of full-time staff, given access to food and water ad libitum and maintained under a 12-hour light/dark cycle, with temperature maintained at 22–25 degrees Celsius. All were of normal health and immune status, and were treatment, procedure, and invasive testing naïve prior to the initiation of our studies. All experiments were conducted with sex and age-matched mice (5 weeks of age). The influence of sex was not assessed. Experiments depicted in Fig. 1 were performed using GF mice from both sexes and conventional male mice. Experiments depicted in Fig. 2–5 were performed using GF female mice. Each independent experiment comprised 8–12 mice and untreated GF mice were included in each round. Each microbial association was evaluated in 5–7 mice from at least 2 independent experiments. Littermates were randomly assigned to the experimental groups and mice were never single-housed. All animal studies were performed according to protocols approved by the NYU Grossman School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Cell Lines

RAW264.7 cells (ATCC), HeLa cells (ATCC), were cultured in DMEM (Corning, Corning, NY, USA) supplemented with 50 U ml−1 penicillin and 50 μg ml−1 streptomycin (Corning), plus 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Cytiva).

CMT93 cells (a gift from Dr. Smith JG, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA), and L929 cells (ATCC) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 50 U ml−1 penicillin and 50 μg ml−1 streptomycin plus 7% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum.

NB324K cells (a gift from Dr. Tattersall P, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 50 U ml−1 penicillin and 50 μg ml−1 streptomycin plus 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum.

MA-104 cells (a gift from Dr. Greenberg HB, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA) were cultured in M199 media (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 50 U ml−1 penicillin and 50 μg ml−1 streptomycin plus 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum.

All cell lines were tested for mycoplasma contamination using LookOut Mycoplasma PCR Detection Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and resulted mycoplasma-free. Cell lines received as gift were not authenticated since they were only used to establish and titer our viral stocks.

Viruses

MNV strains CR6 and CW3 stocks were prepared by transfecting 293T cells (ATCC) with plasmids containing the viral genome (described in Sutherland et al., 2018) using X-tremeGENE™ HP DNA Transfection Reagent (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Supernatants were applied to RAW264.7 cells for two rounds of amplification, followed by ultracentrifugation of the supernatant and resuspension in endotoxin-free PBS (Corning) to generate viral stocks. Concentration of stock was determined by plaque assay (described below) on RAW264.7 cells overlaid with DMEM (Corning) + 1% methylcellulose (Sigma-Aldrich) and evaluated 3 days later using crystal violet.

CVB3 strain H3 stock was prepared by transfecting HeLa cells with plasmids containing the viral genome and the T7 polymerase, both gifts from Dr. Pfeiffer J (UT Southwestern, Dallas, TX, USA), using Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rochester, NY, USA). Cell lysate was applied to HeLa cells for two rounds of amplification. Then, the cell lysate was resuspended in PBS + 1 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM CaCl2, and freeze/thawed, and the supernatant was collected and used as viral stock. Stock titer was determined by plaque assay (described below) on HeLa cells overlaid with MEM (Lonza, Walkersville, MD, USA) + 0.5% agarose (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and evaluated 3 days later using crystal violet. MAdV1, and MAdV2 were a gift from Dr. Smith JG (University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA). Viruses were expanded on CMT93 cells and supernatants were collected and used as viral stocks. Concentration of stocks were determined by focus forming assay (described below) on CMT93 cells.

MuAstV-NYU1 stock was generated from the stool of Rag1−/− mice bred at NYU Grossman School of Medicine. Briefly, stools from 6–10 weeks old mice were harvested and homogenized in PBS. Fecal slurry was pelleted, and supernatant was filtered twice using 0.22 μm Millex-GP syringe-driven filter unit (MilliporeSigma, Burligton, MA, USA). The presence of MuAstV and the absence of MNV in the stock was confirmed by Nanopore sequencing of polyadenylated RNA. Viral titer was determined by qPCR after RNA extraction and retrotranscription.

MVMi and MVMp were a gift from Dr. Pintel D (University of Missouri, Columbia, MO, USA). Viruses were expanded on NB324K cells and either cell lysate (MVMp) or supernatant (MVMi) were used as viral stocks. Concentration of stocks were determined by focus forming assay (described below) on NB324K cells.

RRV was a gift from Dr. Greenberg HB (Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA). Virus was expanded on MA-104 cells and supernatant was collected and used as viral stock. Concentration of stock was determined by plaque assay (described below) on MA-104 cells overlaid with M199 (Sigma-Aldrich) + 0.5% agarose and evaluated 5 days later using neutral red.

Reovirus T1L was prepared as described (Sutherland et al., 2018). T1L was quantified by plaque assay using L929 cells overlaid with DMEM containing 1% agar and evaluated 6 days later following neutral red staining (Sutherland et al., 2018).

Bacteria

The Minimal Defined Flora consisted of the 15 bacteria described in Brugiroux et al., 2016. Akkermansia muciniphila YL44 was a gift from Dr. McCoy K (University of Calgary, Canada) and it was grown in 0.1% mucin (Sigma-Aldrich), anaerobic, 37°C. Bacteroides caecimuris I48 was from DSMZ and it was grown in BHI (Anaerobe Systems,), anaerobic, 37°C. Muribaculum intestinale YL27 (DSMZ) was grown in chopped meat media (Anaerobe Systems), anaerobic, 37°C. Turicimonas muris was a gift from Dr. McCoy K and it was grown in BHI, anaerobic, 37°C. Escherichia coli Mt1B1 (DSMZ) was grown in LB (Sigma-Aldrich), aerobic, 37°C. Bifidobacterium longum subsp. animalis YL2 (DSMZ) was grown in BHI, anaerobic, 37°C. Staphylococcus xylosus 33ERD13C (DSMZ) was grown in TSB-yeast (Sigma Aldrich), aerobic, 37°C. Streptococcus danieliae ERD01G (DSMZ) was grown in TSB-yeast, microaerophilic, 37°C. Enterococcus faecalis KB1 (DMSZ) was grown in TSB-yeast, aerobic, 30°C. Acutalibacter muris KB18 (DSMZ) was grown in BHI, anaerobic, 37°C. Clostridium clostridioforme YL32 (DSMZ) was grown in PYG (Anaerobe Systems), anaerobic, 37°C. Flavinofractor plautii YL31 (DSMZ) was grown in PYG, anaerobic, 37°C. Blautia coccoides YL58 (DSMZ) was grown in chopped meat media, anaerobic, 37°C. Lactobacillus reuteri I49 (DMSZ) was grown in MRS, microaerophilic, 37°C. Clostridium innocuum I46 (DSMZ) was grown in chopped meat media or PYG, anaerobic, 37°C.

Yersinia Pseudotuberculosis was a gift from Dr. Darwin A (NYU), and it was grown overnight in Luria-Bertani broth with shaking at 28°C. In the morning, the bacterial were subcultured in fresh Luria-Bertani broth with shaking at 28°C until OD 0.7–0.9. Bacterial density was confirmed by dilution plating. 9-week-old female GF mice were inoculated by oral gavage with 2×104 CFU resuspended in 200 μl PBS. Severity of disease was quantified through a scoring system in which individual mice received a score of 1 in case of the presence of visible blood in the stool, and between 0 and 2 of the following: hunched posture and diarrhea.

METHOD DETAILS

Viral inoculation

Viruses were administered to mice by oral gavage at about 5 weeks of age. Doses administered were 3×106 PFU/mouse for MNV CR6 and CW3; 1×107 PFU/mouse for CVB3; 1×106 FFU/mouse for MAdV1; 5×104 FFU/mouse for MAdV2; 1×1010 genome copies/mouse for MuAstV; 2×105 FFU/mouse for MVMi; 5×106 FFU/mouse for MVMp; 2×107 PFU/mouse for RRV; 1×108 PFU/mouse for T1L. For experiments depicted in Fig. 1 stool and blood were collected before viral inoculation and at 2, 5, 10, 30 and 60 days after inoculation. For experiments depicted in Fig. 2–5, stool was collected before viral inoculation and at 5 and 28 days after inoculation, whereas blood was collected 28 days after inoculation.

Sample processing and nucleic acid extraction

Stool samples were homogenized in PBS for nucleic acid extraction by mechanical disruption with zircon beads (BioSpec Products, Bartlesville, OK, USA) using a FastPrep-24 machine (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH, USA). Lysate slurry was spun down at 2000 g, 5 min, 4°C and the supernatant was spun down again at 8000 g, 5 min, 4°C to completely remove debris. Colon and small intestine segments were mechanically disrupted in PBS with metal beads (Qiagen) using a FastPrep-24 machine. Subsequently, lysate slurry was spun down at 8000 g, 5 min, 4°C to remove debris and a portion of the supernatant was used for RNA extraction. DNA was purified using DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kits (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA was purified using RNeasy extraction kits (Qiagen) with a DNase (Qiagen) incubation step according to the manufacturer’s protocol. 200 μL of stool PBS homogenate and 50 μL of blood were used for nucleic acid extraction. cDNA was synthesized using ProtoScript First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (NEB) using random primers according to the manufacturer’s protocol. All cDNA products were stored at −20 °C.

Viral quantification

For plaque assays, samples were serially diluted in PBS or DMEM and 500 μL were used to overlay almost confluent cells in 6 well plates (Corning). Cells were incubated at 37°C and gently shaken every 15 minutes. After 1 h, inoculum was removed, and cells were overlaid with the semi-solid media described above. After the number of days indicated above, cells were either fixed by adding PBS + 4% PFA (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h and then stained with crystal violet or incubated ON with PBS + 0.05% Neutral Red (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) and fixed with PBS + 4% PFA for 1 h.

For focus forming assays, samples were serially diluted in PBS or DMEM and 50 μL were used to overlay almost confluent cells in a 96 multi-well clear-bottom black plate (Corning). Cells were incubated at 37°C and gently shaken every 15 minutes. After 1 h, inoculum was removed and cells were overlaid with DMEM + 10% fetal bovine serum (GE Healthcare Life Science, Piscataway, NJ, USA). After 1 day, cells were fixed with HyClone Water (GE Healthcare Life Science) + 2% PFA for 20 min on ice, and then permeabilized with a quench/perm buffer (20 mM glycine, 0.25% TX-100 in PBS) for 20 min on ice. Cells were then stained with a primary antibody for 1 h on ice. Anti-adenovirus antibody clone 8C4 (Fitzgerald Industries) was used to detect MAdV1 and MAdV2, and a non-commercial α-MVM NS protein antibody previously described (Yeung et al., 1991, a gift from Dr. Tattersall P) was used to detect MVM. Then, we stained for 15 min on ice with a secondary α-mouse IgG AF488 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich). Plates were imaged using an EVOS Cell Imaging System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and focus forming units were manually enumerated using ImageJ (NIH). Quantification of viral nucleic acid was performed on DNA and cDNA samples using LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master or LightCycler 480 Probes Master (Roche), and absolute amount was calculated by comparison with in-house linearized plasmid standards.

Plaque reduction neutralization test

Several studies reported that direct methods to assess RRV in adult mice fail to identify 100% of the mice infected, as assessed by antibody titer (Fenaux et al., 2006; Graham et al., 2007; Pane et al., 2014). Serum was recovered from blood collected from the submandibular vein at 20–30 days after viral inoculation. Serum inactivated for 30 min at 56°C was diluted in PBS and the same amount of virus was added to all conditions before 1 h incubation at 37°C. Then, this mix was used as inoculum for plaque assay and focus forming assay, which were performed as previously described.

Organ processing

Colon, small intestine, mesenteric lymph nodes, lungs, and spleen were harvested from untreated GF mice or GF mice 28 days after inoculation with viruses and bacteria.

A segment of the distal colon (4 mm long and 3 cm away from the rectum) and three segments of the midsection of the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum (each 2 mm long) were collected and kept at −80°C until RNA isolation. Additionally, 3 mm from the distal colon and from the ileum were collected and fixed in formalin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for histological analysis.

For single cells suspension, small intestinal and colonic tissues were flushed with PBS, fat and Peyer’s patches were removed, and the tissues were incubated first with 20 mL of HBSS (Gibco) with 2% HEPES (Corning), 1% sodium pyruvate (Corning), 5mM EDTA, and 1 mM dithiothreitol (Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 min at 37°C, and then with new 20 mL of HBSS with 2% HEPES, 1% sodium pyruvate, 5mM EDTA for 10 min at 37°C. Tissue bits were washed in HBSS + 5% FCS, minced, and then enzymatically digested with collagenase D (0.5 mg/mL, Roche) and DNase I (0.01 mg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich) for 30–45 min at 37°C with constant stirring. Digested solutions were passed through 70 μm cell strainers (BD) and cells were subjected to gradient centrifugation using 40% Percoll (Sigma-Aldrich).

IELs were recovered from the liquid phase of the first small intestine incubation, washed with PBS, and subjected to gradient centrifugation using 40% Percoll.

mLNs were collected and passed through 100 μm cell strainers and resuspended in PBS.

Lungs and spleens were grossly minced and enzymatically digested with collagenase D (0.5 mg/mL) and DNase I (0.01 mg/mL) for 20–30 min at 37°C. Digested solutions were passed through 100 μm cell strainers, resuspended in ACK buffer to lyse the red blood cells, and resuspended in PBS.

For the analysis of the cytokine production, cells were plated in RPMI with 10% FBS and treated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (50 ng/mL, MilliporeSigma) and ionomycin (1 μg/mL, MilliporeSigma) in the presence of GolgiStop (BD) and GolgiPlug (BD) for 4 h at 37°C.

Flow Cytometry

Cells were pre-incubated with CD16/CD32 Fc block (BD Pharmingen). Surface and intracellular cytokine staining was performed per manufacturer’s instructions in PBS + 2% FBS for 20 min on ice. Three staining panels were utilized. The first panel included antibodies against BST2, NK1.1, THY1.2, F4/80, CD103, LY6C, CD11b, MHC-II, CD45, CD11c, CD19, CD64, and B220. To stain the spleen samples, we substituted CD103 with CD8a for a better evaluation of the dendritic cell subsets. The second panel included antibodies against GATA3, CD11b, CD11c, GR1, CD19, TER119, Tbet, TCRγδ, FOXP3, CD8, CD4, RORγt, CD62L, CD127, NK1.1, CD44, CD3ε, CD45. The third panel included antibodies against IFN-γ, CD11b, CD11c, GR1, CD19, TER119, Nk1.1, Il-22, TCRγδ, GRANZYME B, IL-17a, CD8, CD4, IL-10, CD127, IL-4, CD3E, CD45. Samples were fixed with either Fixation Buffer (Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA) or eBioscience Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For intracellular staining of transcription factor, cells were permeabilized with the eBioscience Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set at room temperature for 30 min in the presence of antibodies. For intracellular staining of cytokines, cells were permeabilized with Intracellular Staining Permeabilization Wash Buffer (Biolegend) at room temperature for 30 min in the presence of antibodies. Zombie UV Fixable Viability Kit (Biolegend) was used to exclude dead cells. Samples were acquired on a BD LSR II (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software (Treestar, Inc., Ashland, OR, USA).

Immunophenotypes

Flow cytometry fold change values were calculated by dividing the frequency of a given cell type by the average frequency obtained from the GF mice in the same experimental round. Statistical differences between each colonization condition and the GF mice were calculated by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunn’s post-hoc analysis using the R package “stats”. To control for multiple testing, a false discovery rate was calculated according to the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure using the R package “stats” for all the cell type analyzed.

Nanopore sequencing and data processing

The cDNA sequencing library was prepared using the Nanopore cDNA-PCR sequencing methodology (SQK-PCS109) with half of the library sequenced on a flongle for 24 hours.

For astrovirus consensus sequence generation, sequence reads were basecalled using Guppy v3.6, aligned against a known astrovirus genome, and then aligned reads were extracted for de novo assembly using Canu (Koren et al., 2017). The draft genome was polished using four rounds of Racon (Vaser et al., 2017), and a final consensus sequence generated using Medaka (https://nanoporetech.github.io/medaka/).

For metagenomic analysis, all read data were analyzed using the FASTQ WIMP Nanopore Epi2me workflow (https://epi2me.nanoporetech.com/).

RNA deep sequencing

CEL-seq2 was performed on 67 colonic and 60 small intestinal RNA samples. Sequencing was performed on Illumina NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina). All samples from the same organs were sequenced together, thus no correction for batch effect was necessary.

Selection of differentially expressed genes

RNA-Seq results were processed using the R package “DESeq2” to obtain variance stabilized count reads, fold changes relative to GF condition, and statistical p-value. Analysis of the whole tissue transcriptome focused on differentially expressed genes, defined as the genes with an absolute fold change relative to GF >2 and an unadjusted p-value <0.01.

GSEA gene signatures

GSEA was performed using the R package “WebGestaltR”. GSEA gene signatures were generated in a manner similar to Godec et al., 2016 by selecting the top upregulated or downregulated genes, up to 200, with an FDR<0.02 or an unadjusted p-value<0.001. Gene signatures consisting of less than 10 genes were discarded. IL-22 and bacterial signatures were based on the transcriptional data described in Gronke et al., 2019 and Geva-Zatorsky et al., 2017, respectively.

Computational analysis

Hierarchical clustering of the population and cytokine frequencies were performed on the Euclidean distances using the R package “stats”. Distance-based redundancy analysis (db-RDA) was used to determine the contribution of different factors to the variance observed within the immunophenotypes samples or differentially expressed genes using the R package “vegan”. Euclidean distance between colonization conditions according to differentially expressed genes was calculated using the R package “stats”, and permutational multivariate analysis of variance on these distances was calculated using the R package “vegan”. Heatmaps were generated using either the package “ggplot2” or “pheatmap”. Gene ontology analysis was performed using the package “clusterProfiler”. Canonical pathway and upstream regulators analysis were performed by uploading the differentially expressed genes to Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software (Qiagen).

Microscopy on intestinal tissue

Small intestinal and colonic tissues were cut open along the length, pinned on black wax, and fixed in 10% formalin. Tissues were embedded in 3% low melting point agar (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Formalin embedding, cutting, and hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed by the NYU Histopathology core. Sections were imaged either on a Leica SCN400 F microscope (Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA).

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical tests were selected based on appropriate assumptions with respect to data distribution and variance characteristics. Statistical differences were determined as described in figure legend using either R or GraphPad Prism 8 software (La Jolla, CA, USA). No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size.

Supplementary Material

Table S2. Complete immunological dataset. Related to Figures 2 and 3 (A) Description of the gating strategy. (B) Immunophenotypes evaluated in this study as fold changes relative to uninfected GF mice. (C) Immunophenotypes evaluated in this study as frequencies of cell types relative to uninfected GF mice.

Table S3. Fold Change of Colonic and Small-Intestinal Transcripts. Related to Figure 4 (A-B) Fold change of colonic (A) and small intestinal (B) transcripts compared to GF mice.

(C-D) DE common genes between mice colonized with MDF and mice infected with viruses.

(E) Viral titer evaluated in the colonic and small intestinal tissues at 28 dpi.

Table S4. Bacterial gene sets. Related to Figure 6 (A-B) Colonic (A) and small intestinal (B) gene sets for GF mice monocolonized with commensal bacteria.

Table S5. Description of immune populations used for the comparison of the immune modulation induced by virus and bacteria. Related to Figure 6.

(A) Description of the populations compared.

(B-C) Frequencies of the compared populations from Geva-Zatorsky et al (B) and this study (C).

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Alexa Fluor 488 anti-mouse CD317 (BST2, PDCA-1) Antibody | Biolegend | CAT#127012; RRID: AB_1953287 |

| Alexa Fluor 488 anti-mouse GATA3 Antibody | BD | CAT#560163 |

| Alexa Fluor 488 anti-mouse IFN-γ Antibody | Biolegend | CAT#505813; RRID: AB_493312 |

| PerCP/Cyanine5.5 anti-mouse NK-1.1 Antibody | Biolegend | CAT#108728; RRID: AB_2132705 |

| PerCP/Cyanine5.5 anti-mouse CD90.2 (Thy-1.2) Antibody | Biolegend | CAT#140322; RRID: AB_2562696 |

| PerCP/Cyanine5.5 anti-mouse/human CD11b Antibody | Biolegend | CAT#101228; RRID: AB_893232 |

| PerCP/Cyanine5.5 anti-mouse CD11c Antibody | Biolegend | CAT#117328; RRID: AB_2129641 |

| PerCP/Cyanine5.5 anti-mouse Ly-6G/Ly-6C (Gr-1) Antibody | Biolegend | CAT#108428; RRID: AB_893558 |

| PerCP/Cyanine5.5 anti-mouse CD19 | eBioscience | CAT#45-0193-82; RRID: AB_1106999 |

| PerCP/Cyanine5.5 anti-mouse TER-119/Erythroid Cells Antibody | Biolegend | CAT#116228; RRID: AB_893636 |

| PE anti-T-bet Antibody | Biolegend | CAT#644810; RRID: AB_2200542 |

| PE anti-mouse IL-22 Antibody | eBioscience | CAT#12-7221-82; RRID: AB_10597428 |

| PE-CF594 anti-mouse γδ T-Cell Receptor Antibody | BD | CAT#563532. |

| PE/Cyanine7 anti-mouse F4/80 Antibody | Biolegend | CAT#123114; RRID: AB_893478 |

| PE/Cyanine7 anti-mouse Granzyme B Antibody | eBioscience | CAT#25-8898-82; RRID: AB_10853339 |

| APC anti-mouse CD8a Antibody | Biolegend | CAT#100712; RRID: AB_312751 |

| APC anti-mouse CD103 Antibody | Biolegend | CAT#121414; RRID: AB_1227502 |

| APC anti-mouse FOXP3 Antibody | eBioscience | CAT#17-5773-82; RRID: AB_AB_469457 |

| APC anti-mouse IL-17A Antibody | Biolegend | CAT#506916; RRID: AB_536018 |

| Alexa Fluor 700 anti-mouse Ly-6C Antibody | BD | CAT#561237. |

| Alexa Fluor 700 anti-mouse CD8a Antibody | Biolegend | CAT#100730; RRID: AB_493703 |

| APC/Cyanine7 anti-mouse/human CD11b Antibody | Biolegend | CAT#101226; RRID: AB_830642 |

| APC/Cyanine7 anti-mouse CD4 Antibody | Biolegend | CAT#100414; RRID: AB_312699 |

| Pacific Blue anti-mouse I-A/I-E Antibody | Biolegend | CAT#107620; RRID: AB_493527 |

| BV421 anti-mouse RORγt Antibody | BD | CAT#562894. |

| BV421 anti-mouse IL-10 Antibody | BD | CAT#566295. |

| Brilliant Violet 570 anti-mouse CD45 Antibody | Biolegend | CAT#103136; RRID: AB_2562612 |

| Brilliant Violet 570 anti-mouse CD62L Antibody | Biolegend | CAT#104433; RRID: AB_10900262 |

| Brilliant Violet 605 anti-mouse CD11c Antibody | Biolegend | CAT#117334; RRID: AB_2562415 |

| Brilliant Violet 605 anti-mouse CD127 (IL-7Rα) Antibody | Biolegend | CAT#135041; RRID: AB_2572047 |

| Brilliant Violet 650™ anti-mouse NK-1.1 Antibody | Biolegend | CAT#108736; RRID: AB_2563159 |

| Brilliant Violet 711 anti-mouse CD64 (FcγRI) Antibody | Biolegend | CAT#139311; RRID: AB_2563846 |

| Brilliant Violet 711 anti-mouse/human CD44 Antibody | Biolegend | CAT#103057; RRID: AB_2564214 |

| Brilliant Violet 711 anti-mouse IL-4 Antibody | BD | CAT#564005. |

| Brilliant Violet 786 anti-mouse CD3e Antibody | BD | CAT#564379. |

| Super Bright 780 anti-mouse CD19 Antibody | eBioscience | CAT#78-0193-82; RRID: AB_2722936 |

| BUV395 anti-mouse CD45 Antibody | BD | CAT#564279. |

| BUV395 anti-mouse CD45R/B220 Antibody | BD | CAT#563793. |

| Anti-adenovirus antibody, clone 8C4 | Fitzgerald Industries | CAT#10R-A115c |

| Anti-MVM NS protein antibody | Gift from Dr. Tattersall P (Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA) | N/A |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| Coxsackie B3 Virus, strain H3 | Gift from Dr. Pfeiffer J (UT Southwestern, Dallas, TX, USA) | CVB3-H3 |

| Murine Adenovirus, strain 1 | Gift from Dr. Smith JG (University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA) | MAdV1 |

| Murine Adenovirus, strain 2 | Gift from Dr. Smith JG (University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA) | MAdV2 |

| Murine Astrovirus | This paper | NYU1 |

| Minute Virus of Mice, strain i | Gift from Dr. Pintel D (University of Missouri, Columbia, MO, USA) | MVMi |

| Minute Virus of Mice, strain p | Gift from Dr. Pintel D (University of Missouri, Columbia, MO, USA) | MVMp |

| Norovirus MNV-CR6 | Strong et al., 2012 | MNV-CR6 |

| Norovirus MNV-CW3 | Strong et al., 2012 | MNV-CW3 |

| Rhesus Monkey Rotavirus | Gift from Dr. Greenberg HB (Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA) | RRV |

| Reovirus, strain T1L | Sutherland et al., 2018 | T1L |

| Akkermansia muciniphila YL44 | Gift from Dr. McCoy K (University of Calgary, Canada) | YL44 |

| Bacteroides caecimuris I48 | DSMZ | I48 |

| Muribaculum intestinale YL27 | DSMZ | YL27 |

| Turicimonas muris | Gift from Dr. McCoy K (University of Calgary, Canada) | N/A |

| Escherichia coli Mt1B1 | DSMZ | Mt1B1 |

| Bifidobacterium longum subsp. animalis YL2 | DSMZ | YL2 |

| Staphylococcus xylosus 33ERD13C | DSMZ | 33ERD13C |

| Streptococcus danieliae ERD01G | DSMZ | ERD01G |

| Enterococcus faecalis KB1 | DSMZ | KB1 |

| Acutalibacter muris KB18 | DSMZ | KB18 |

| Clostridium clostridioforme YL32 | DSMZ | YL32 |

| Flavinofractor plautii YL31 | DSMZ | YL31 |

| Blautia coccoides YL58 | DSMZ | YL58 |

| Lactobacillus reuteri I49 | DSMZ | I49 |

| Clostridium innocuum I46 | DSMZ | I46 |

| Yersinia Pseudotuberculosis | Gift from Dr. Darwin A (NYU, NY, USA) | N/A |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Collagenase D | Roche | CAT#11088882001 |

| DNAse I | Sigma Aldrich | CAT#11284932001 |

| Percoll | Sigma Aldrich | CAT#P1644-1L |

| Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate MilliporeSigma | Sigma Aldrich | CAT#P1585-1mg |

| Ionomycin | MilliporeSigma | CAT#80056-892 |

| BD GolgiStop | BD | CAT#554724 |

| BD GolgiPlug | BD | CAT#555029 |

| Purified Rat Anti-Mouse CD16/CD32 | BD | CAT#553142 |

| Fixation Buffer | Biolegend | CAT#420801 |

| eBioscience™ Foxp3 / Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set | ThermoFisher Scientific | CAT#00-5523-00 |

| Intracellular Staining Permeabilization Wash Buffer (10X) | Biolegend | CAT#421002 |

| Agarose, Low Melting Point | Promega | CAT#V2111 |

| X-tremeGENE™ HP DNA Transfection Reagent | Roche | CAT#6366546001 |

| Lipofectamine 3000 Reagent | ThermoFisher Scientific | CAT#L3000015 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Zombie UV Fixable Viability Kit | Biolegend | CAT#423108 |

| DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit | Qiagen | CAT#69506 |

| RNeasy extraction kit | Qiagen | CAT#74106 |

| ProtoScript First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit | NEB | CAT#E6300L |

| LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master | Roche | CAT#04887352001 |

| LightCycler 480 Probes Master | Roche | CAT#04887301001 |

| PCR-cDNA Sequencing Kit | Oxford Nanopore Technology | CAT#SQK-PCS109 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| RNA sequencing reads | This paper | PRJNA706512 |

| RNA expression counts | This paper | GSE168293 |

| MuAstV stock sequencing | This paper | PRJEB43445 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| HEK 293T | ATCC | CRL-11268 |

| RAW264.7 cells | ATCC | TIB-71 |

| HeLa cells | ATCC | CCL-2 |

| CMT93 | Gift from Dr. Smith JG (University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA). | N/A |

| NB324K cells | Gift from Dr. Tattersall P (Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA) | N/A |

| MA-104 | Gift from Dr. Greenberg HB (Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA). | N |

| L929 | ATCC | CCL-1 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Conventional C57BL/6J mice | Jackson Laboratory | #000664 |

| Conventional Rag1−/− mice | Jackson Laboratory | #002216 |

| Germ-free C57BL/6J mice | This paper | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| See Table S6 for primers used for this study | ||

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Plasmid CVB3 | Gift from Dr. Pfeiffer J (UT Southwestern, Dallas, TX, USA) | N/A |

| Plasmid T7 | Gift from Dr. Pfeiffer J (UT Southwestern, Dallas, TX, USA) | N/A |

| Plasmid CR6 | Strong et al., 2012 | N/A |

| Plasmid CW3 | Strong et al., 2012 | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Flowjo 10.4.2 | Flowjo, LLC | https://www.flowjo.com/ |

| Illustrator CC | Adobe | https://www.adobe.com/products/illustrator.html |

| Software: R v3.4.1 | R Project | https://www.r-project.org/ |

| Software: Ingenuity Pathway Analysis | QIAGEN | https://digitalinsights.qiagen.com/qiagen-ipa |

| Software: Prism 9 | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/ |

| Algorithm: DESeq2 | DESeq2 v3.12 package | https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DESeq2.html |

Highlights:

Profiles of host response to enteric viruses highlight role of microbiota in infection and persistence

Viruses can induce enduring changes on the immune system in absence of disease

Diverse strain-specific responses occur alongside common IL-22 and Th1mediated immunity

Comparison of viral and bacterial exposure reveals commonalities and differences

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank Drs. Julie Pfeiffer (UT Southwestern), Jason G. Smith (University of Washington), David Pintel (University of Missouri), Peter Tattersall (Yale University), Harry B Greenberg (Stanford University), and Kathy McCoy (University of Calgary) for sharing reagents and culturing techniques, and Dr. P’ng Loke (NIH) for comments on the manuscript, NYU Grossman School of Medicine Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting, Microscopy, Genome Technology, and Histology Cores for use of their instruments and technical assistance (supported by National Institutes of Health [NIH] grants P31CA016087, S10OD01058, and S10OD018338), and Margie Alva, Juan Carrasquillo, and Beatriz Delgado for assistance with gnotobiotics. This research was supported by NIH grants DK093668 (K.C.), AI121244 (K.C.), HL123340 (K.C.), AI130945 (K.C.), AI140754 (K.C.), DK108562 (J.J.B.), HL007751 (J.J.B.), AI038296 (T.S.D.), DK098435 (T.S.D.), and a pilot award from the NYU Cancer Center grant P30CA016087 (K.C.). Additional support was provided by the Faculty Scholar grant from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (K.C.), Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation (K.C.), Merieux Institute (K.C.), Kenneth Rainin Foundation (K.C.), Judith & Stewart Colton Center of Autoimmunity (K.C.), and the Heinz Endowments (T.S.D.). K.C. is a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Investigator in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Diseases. Fig. S2A and graphical abstract were created using BioRender.com.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS