People enrolling in hospice expect that they will be supported through the dying process, ideally within the comfort of their own homes. This means that patients and caregivers assume they will receive physical, emotional, logistical, and bereavement support from a coordinated multidisciplinary team of healthcare professionals through their final days and beyond. Yet, as demonstrated in Luth et al.,1 a substantial portion of hospice enrollees with dementia—as many as one in four—will have their hospice experience disrupted by a “live discharge,” which refers to patient- or hospice-initiated disenrollment from hospice while still alive.2,3

Why is it that people are disenrolled from hospice alive? The problem of live discharge is an artifact of the development of the Medicare Hospice Benefit in the early 1980s, which included several cost-saving measures, notably that enrollees have a prognosis of 6 months or less if the disease runs its expected course.4 At the time, hospice recipients were primarily comprised of cancer or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients.5 While prognosis is relatively easy to determine in people with advanced cancer or AIDS, it is notoriously difficult to estimate in people living with dementia (PLWD).6 As a result, PLWD are up to four times more likely to experience hospice-initiated discharge because their “condition stabilizes or improves” (extended prognosis), and they no longer meet the 6-month prognosis requirement.2,3

Live discharge for extended prognosis might sound like a positive outcome and is sometimes referred euphemistically as “graduating” from hospice. But this situation is not like a Hollywood movie where a person is miraculously cured and goes on to live happily ever after. Rather, for a PLWD who may be completely nonverbal, bedbound, and dependent for all basic activities of daily living, it means that they are no longer declining fast enough to remain eligible for hospice. PLWD and their caregivers describe live discharge as getting “kicked out” and more akin to getting expelled than graduating.7 Live discharge is of such high concern that Medicare is currently developing a live discharge quality metric that could eventually be part of hospice care quality ratings.8

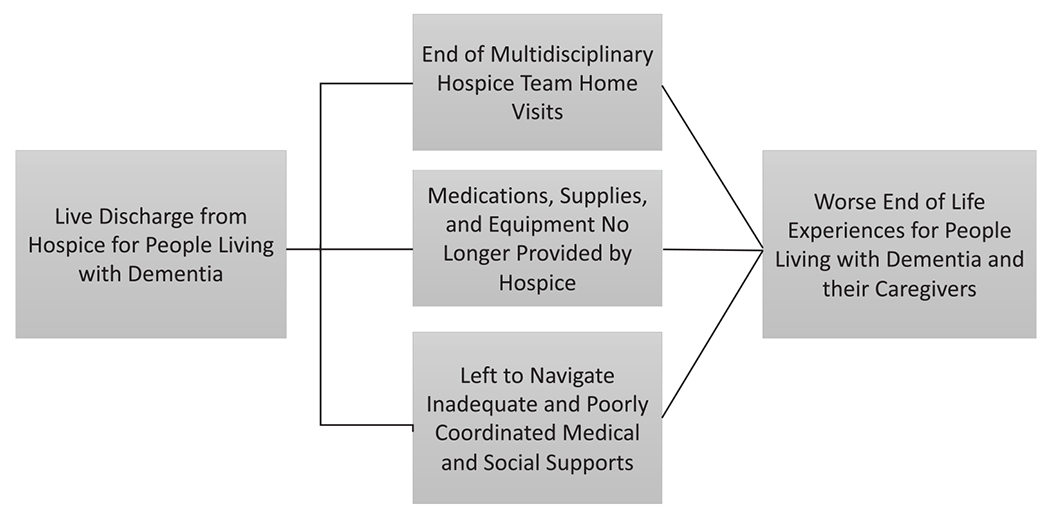

The disruption in the continuity of hospice care is particularly onerous for patients and caregivers because, under the Medicare Hospice Benefit, hospices bear the financial responsibility for providing all aspects of care related to the terminal prognosis. Thus, when hospice ends, the patient not only loses the multidisciplinary healthcare team that includes nurses, social workers, aides and physicians, but they also lose the coordinated provision of durable medical equipment, pharmaceuticals, and other medical supplies. Caregivers must then arrange other sources of support for help with activities of daily living, get prescriptions from different physicians, and replace durable medical equipment—activities that take substantial additional logistical and emotional energy when they are at their most depleted.

These negative consequences of live discharge are especially profound for PLWD and their caregivers (Figure 1). Not only are PLWD at higher risk of live discharge, but they also require much more support and resources from caregivers. Family caregivers of PLWD are three times more likely to experience caregiver burden in the PLWDs’ last year of life compared to caregivers of people dying from other diseases.9 This is unsurprising given the amount of physical labor, as well as financial, emotional, and other resources, involved in caring for PLWD, especially for PLWD cared for at home by family caregivers.10

FIGURE 1.

A person-centered approach to understanding the impacts of live discharge on people living with dementia and their caregivers

The issue of live discharge is closely intertwined with concerns over the appropriate role of hospice for PLWD and how to best serve the many needs of PLWD and their caregivers at the end of life.11,12 There are no equivalent services currently available in the United States that provide the same level of holistic and comprehensive services in the location where the patient resides as hospice does. While PLWD living in assisted living facilities or nursing homes may have some needs met by the facility, there are limited state or federal supports available for caring for seriously ill PLWD in the home. Hospice may fill the role of providing in-home supports and services where a vacuum exists otherwise. Using hospice to fill a gap in services is not an effective or efficient use of resources—it simply has been the only option.

Adding to the complexity, the problem of live discharge is linked with issues surrounding the growth in access to hospice for PLWD, rising hospice costs, and shifts in the hospice marketplace over the past couple of decades. Hospice has seen a threefold increase in utilization in the past two decades, driven primarily by enrollment of patients with noncancer diagnosis, including a high proportion of those with dementia. Compared to 2000 when very few PLWD enrolled in hospice, by 2018, approximately 20% of hospice enrollees had a principal hospice diagnosis of dementia; another 25% had a comorbid dementia diagnosis.13–15 Over the same time period, both the costs of hospice and presence of for-profits in the market skyrocketed. Medicare spending on hospice increased from $2.9 billion to almost $20 billion, and the proportion of for-profit hospices in the marketplace increased from 30 to 70%.16 While being a for-profit or nonprofit does not necessarily imply a different quality of care delivered by a hospice organization, for-profit hospices have an incentive to enroll PLWD whose uncertain prognosis results in much longer and more profitable lengths of stay. Under the per-beneficiary daily payment for hospice, longer stays with lower acuity result in higher margins, which can either be distributed as profit for shareholders or used to offset spending on patients with higher acuity and costs. Evidence shows that for-profit hospices have higher rates of live discharge; they are more likely to discharge patients when they are likely to suffer financial or regulatory consequences of questionably long enrollments.17 This suggests that some hospices may be more aggressively enrolling PLWD to increase margins while failing to adequately consider the impacts of live discharge on their patients.

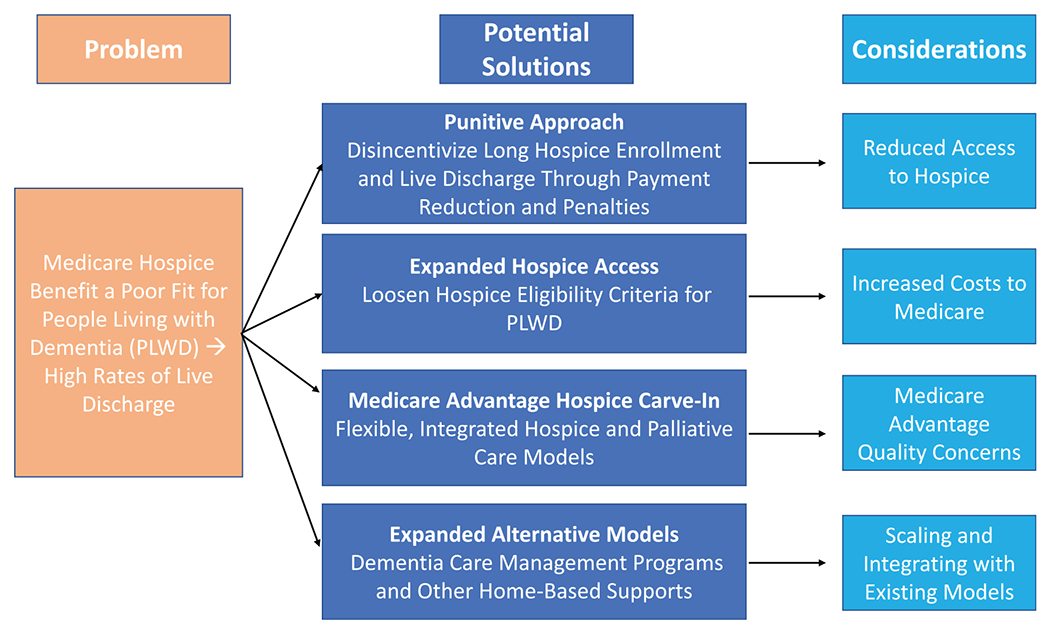

While it is generally acknowledged that the Medicare Hospice Benefit is a poor fit for PLWD as currently structured—with live discharge as one example of this mismatch—the solutions for this problem are up for debate (Figure 2). Medicare’s regulatory and payment responses to date have been to try to disincentivize long enrollments of PWD and maintain hospice as a service for the final weeks and days of life.16 While this may reduce Medicare expenditures on hospice and root out some “bad players” who are trying to profit off the system, it may have the unintended consequence of reducing access to beneficial services for PLWD and their caregivers. This reduction in access to services is especially concerning given that other services to support PLWD approaching end of life are piecemeal, insufficient, and often not available nationwide.

FIGURE 2.

Potential solutions for improving hospice and end-of-life care for people living with dementia

Another approach, as suggested by Luth et al.1 and others, is to loosen the eligibility criteria for PLWD and other noncancer diagnoses. This approach would likely need to be accompanied by either a significant shift in society’ s attitude regarding how much we are willing to spend on end-of-life care for PLWD or substantial changes to the hospice payment mechanisms to contain Medicare hospice spending. Other efforts underway include developing, testing, and implementing a number of innovative care models, such as dementia care management programs and home-based palliative care, which could either be a replacement for hospice or could be integrated with hospice services.18,19

The extension of the Medicare Advantage (MA) Value Based Insurance Design Model for hospice in 2021 may offer another solution. Historically, the Medicare Hospice Benefit had been “carved out” of MA plans, but under the new model, MA will remain responsible for providing and paying for hospice care for their enrollees. This change may give MA plans greater flexibility to negotiate payments with hospice providers and create integrated palliative and hospice care models, which may better fit the trajectory and needs of PLWD. On the other hand, there are important concerns regarding MA care quality. For example, one study found that bereaved caregivers of MA enrollees were more likely to have lower ratings of end-of-life care compared to fee-for-service enrollees.20

High rates of live discharge from hospice among PLWD are a serious problem that makes the end-of-life experience worse for patients and caregivers. PLWD and their caregivers deserve not to be abandoned at the end of life when they are at their most vulnerable and exhausted. As the debate about the role of hospice for PLWD continues to evolve, we must stay focused on meeting the needs of PLWD and their caregivers at end of life in the place and manner they prefer. This effort will require continuous development and testing of different approaches for meeting the needs of PLWD and caregivers through both hospice and alternative models. A one-size-fits-all solution may not work. Ultimately, our goal should be to create systems and models of care that seamlessly integrate care across the continuum for PLWD to ensure that they and their caregivers have the supports they need and deserve.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES

This publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (NIH), through UCSF-CTSI Grant Number KL2 TR001870 (Hunt); a National Center for Palliative Care Research (NPCRC) Kornfield Scholars Career Development Award (Hunt); and NIH NIA K01AG059831 (Harrison); and NIH NIA P01AG066605 (Hunt and Harrison).

SPONSOR’S ROLE

No sponsor had any role in the preparation of this article. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the funders.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Luth EA, Rush KL, Xu JC, et al. Survival in hospice patients with dementia: the effect of home hospice and nurse visits. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021. 10.1111/jgs17066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Russell D, Diamond EL, Lauder B, et al. Frequency and risk factors for live discharge from hospice. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017; 65(8):1726–1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Vleminck A, Morrison RS, Meier DE, Aldridge MD. Hospice care for patients with dementia in the United States: a longitudinal cohort study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19(7): 633–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare and Medicaid programs: Hospice Conditions of Participation, Part 418 subpart 54 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mor V, Teno JM. Regulating and paying for hospice and palliative care: reflections on the medicare hospice benefit. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2016;41(4):697–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitchell SL, Miller SC, Teno JM, Kiely DK, Davis RB, Shaffer ML. Prediction of 6-month survival of nursing home residents with advanced dementia using ADEPT vs hospice eligibility guidelines. Jama. 2010;304(17):1929–1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wladkowski SP. Dementia caregivers and live discharge from hospice: what happens when hospice leaves? J Gerontol Soc Work. 2017;60(2):138–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Draft measure specifications: transitions from hospice care, Followed by Death or Acute Care (2018). Available online at https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/MMS/Downloads/Development-of-Draft-HQRP-Transitions-Measure-Specifications.pdf. Accessed March 9, 2021.

- 9.Vick JB, Ornstein KA, Szanton SL, Dy SM, Wolff JL. Does caregiving strain increase as patients with and without dementia approach the end of life? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;57(2): 199–208.e192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrison KL, Ritchie CS, Patel K, et al. Care settings and clinical characteristics of older adults with moderately severe dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(9):1907–1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aldridge MD, Bradley EH. Epidemiology and patterns of care at the end of life: rising complexity, shifts in care patterns and sites of death. Health Affairs (Project Hope). 2017;36(7):1175–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harrison KL, Hunt LJ, Ritchie CS, Yaffe K. Dying with dementia: underrecognized and stigmatized. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019; 67(8):1548–1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. Hospice Facts and Figures 2020 Edition. Alexandria, VA. Available online at https://www.nhpco.org/wp-content/uploads/NHPCO-Facts-Figures-2020-edition.pdf. Accessed March 9, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris-Kojetin L, Sengupta M, Park-Lee E. Long-term care providers and services users in the United States: data from the National Study of long-term care providers, 2013-2014. Vital Health Stat. 2016;3(38):2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han B, Remsburg RE, McAuley WJ, Keay TJ, Travis SS. National trends in adult hospice use: 1991–1992 to 1999–2000. Health Affairs (Project Hope). 2006;25(3):792–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Medicare Payment Advisory Committee (MEDPAC). Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy 2020: Chapter 12 Hospice Services. Washington, DC. Avaialble online at http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar20_medpac_ch12_sec.pdf. Accessed March 9, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dolin R, Holmes GM, Stearns SC, et al. A positive association between hospice profit margin and the rate at which patients are discharged before death. Health Affairs (Project Hope). 2017;36(7):1291–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Possin KL, Merrilees JJ, Dulaney S, et al. Effect of collaborative dementia care via telephone and internet on quality of life, caregiver well-being, and health care use: the care ecosystem randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jennings LA, Turner M, Keebler C, et al. The effect of a comprehensive dementia care management program on end-of-life care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(3):443–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ankuda CK, Kelley AS, Morrison RS, Freedman VA, Teno JM. Family and friend perceptions of quality of end-of-life care in medicare advantage vs traditional medicare. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2020345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]