Dear Editor,

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) is an immune-mediated demyelinating disorder characterized by a widespread attack of inflammation in the brain and spinal cord that damages myelin [1]. ADEM is life-threatening and among the most frequent demyelinating disorders in childhood [2]. Its incidence in children has been reported as 0.07–0.51 in Europe [3, 4] and 0.2–0.6 in North America [5] per 100,000 children. Apart from Japan, with a reported incidence of 0.4 per 100,000 children [6], data on its incidence are sparse in Asian countries. Furthermore, there is still no nationwide survey for its incidence and mortality in China. Here, we estimated the nationwide population-based incidence and mortality of ADEM in China, a country encompassing 20% of the world’s population and covering vast areas of Eastern Asia.

This study was based on the Hospital Quality Monitoring System (HQMS), which was launched by the China National Health Commission (NHC) in 2011 to monitor the quality of medical services and appraise the performance of tertiary public hospitals [7]. The system is programed to connect to hospital information systems and to upload a common dataset of information from all inpatient medical records. Until 2018, the HQMS covered 98.5% of tertiary public hospitals throughout mainland China (including 22 provinces, 5 autonomous regions, and 4 municipalities and excluding Taiwan region, Hong Kong, and Macao) where the vast majority of ADEM patients are diagnosed and treated. In-patient data from each tertiary hospital is automatically electronically captured and uploaded. The system collects “Medical Record Homepage”, a summary of each patient’s hospitalization information, which includes 346 variables such as demographic characteristics, diagnosis, hospitalization costs, and length of hospital stay. Each medical record uploaded to HQMS is reviewed by a Quality Assurance Physician for the diagnosis and coders for the ICD-10 code. The completeness, consistency, and accuracy of data are guaranteed according to the “Quality Standards for Filling in Data on the Home Page of Hospitalized Medical Records” (ADEM-related protocol were shown in supplementary materials). Given the vast landmass and the enormous population of China, this nationwide inpatient information-collecting system allows information linkage and overcomes the temporal and spatial limitations.

We identified ADEM-related hospitalization records from 1665 tertiary hospitals in the HQMS database from 1 Jan 2016 to 31 Dec 2018. ADEM-related hospitalizations were identified using the ICD-10 code (G04.0) in any of discharge diagnosis fields. The diagnosis of ADEM is confirmed by a neurologist and reviewed by the Quality Assurance Physician in each tertiary hospital based on the consensus definition proposed by the International Pediatric MS Study Group in 2013 [1]. Newly-diagnosed cases were defined as patients that were first recorded in the system during 2011 to 2018 with ADEM as the primary diagnosis. “The same person” label was generated in the database based on name, gender, and Citizen Identification Number (a unique, unchanging legal number) to avoid multiple counting in the study.

Incidence referred to the number of newly-diagnosed ADEM cases occurring during the study period and calculated per 100,000 person-years. The annual incidence of ADEM for each province was estimated by dividing the number of newly-diagnosed cases by the local population. Age groups were classified using 5-year intervals. Annual incidence was stratified by gender during 2016 to 2018. Standardized incidence rates were adjusted by age and gender according to the most recent national census data from 2010 (http://www.stats.gov.cn/). Individuals who were <15 years of age were defined children in this study. We calculated the 95% confidence interval (CI) using the Poisson distribution. Results were presented as the mean and 95% CI, the mean (SD), or the median and interquartile range. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Beijing Tiantan Hospital and was performed as a project study in the China National Clinical Research Center for Neurological Diseases and the China National Center for Quality Control of Neurological Diseases.

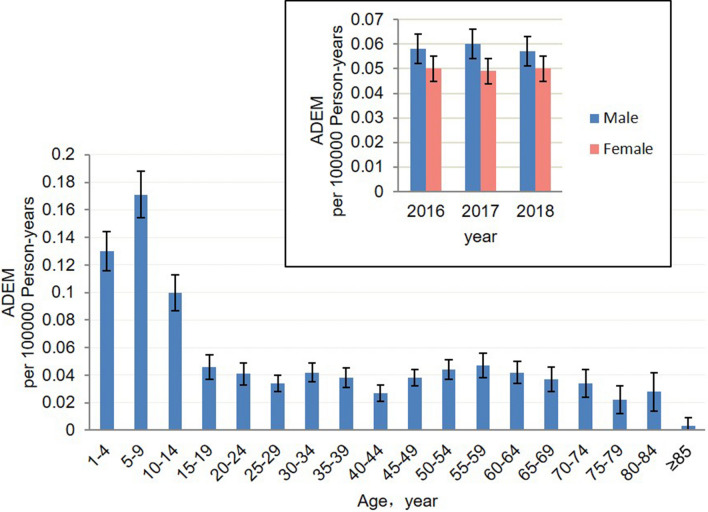

There were 6978 hospitalizations for 3101 ADEM patients, of whom 2265 were newly-diagnosed: 751 in 2016, 760 in 2017, and 753 in 2018. The age- and sex-adjusted incidence of ADEM was 0.054 (95% CI, 0.052–0.056) per 100,000 population-years. The age- and sex-adjusted incidence in children was markedly higher than that of adults: 0.134 (95% CI, 0.126–0.143) in children and 0.038 (95% CI, 0.036–0.04) in adults (P < 0.001). We found no latitude gradient risk in ADEM (Table 1). The incidence of ADEM per 100,000 person-years varied from 0.090 (95% CI, 0.079–0.101) in Shandong to 0.019 (95% CI, 0.011–0.027) in Shaanxi. The peak age of incidence was 5–9 years with an incidence of 0.171 (95% CI, 0.154–0.188) per 100,000 person-years (Fig. 1). A male predominance was found: 0.058 (95% CI, 0.054–0.061) in males and 0.050 (95% CI, 0.047–0.053) in females (P < 0.05). The ratio was 1.16:1.

Table 1.

Hospital distribution and incidence of ADEM in China, 2016–2018.

| Province | Number of tertiary hospitals | Annual incidence rate per 105 person-years (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 51 | 0.066 (0.046–0.086) |

| Tianjin | 30 | 0.064 (0.041–0.087) |

| Hebei | 49 | 0.059 (0.049–0.069) |

| Shanxi | 44 | 0.056 (0.042–0.070) |

| Inner Mongolia | 44 | 0.053 (0.036–0.069) |

| Liaoning | 85 | 0.040 (0.030–0.051) |

| Jilin | 31 | 0.043 (0.029–0.057) |

| Heilongjiang | 60 | 0.027 (0.018–0.037) |

| Shanghai | 35 | 0.029 (0.017–0.041) |

| Jiangsu | 105 | 0.074 (0.063–0.085) |

| Zhejiang | 91 | 0.051 (0.040–0.062) |

| Anhui | 45 | 0.077 (0.064–0.090) |

| Fujian | 47 | 0.049 (0.037–0.062) |

| Jiangxi | 51 | 0.045 (0.034–0.056) |

| Shandong | 95 | 0.090 (0.079–0.101) |

| Henan | 68 | 0.057 (0.048–0.066) |

| Hubei | 74 | 0.034 (0.025–0.043) |

| Hunan | 62 | 0.040 (0.031–0.049) |

| Guangdong | 136 | 0.072 (0.063–0.081) |

| Guangxi | 56 | 0.044 (0.033–0.055) |

| Hainan | 18 | 0.051 (0.024–0.077) |

| Chongqing | 25 | 0.030 (0.019–0.042) |

| Sichuan | 144 | 0.038 (0.031–0.046) |

| Guizhou | 42 | 0.051 (0.038–0.065) |

| Yunnan | 32 | 0.047 (0.035–0.058) |

| Tibet | 7 | 0.020 (-0.008–0.047) |

| Shaanxi | 47 | 0.019 (0.011–0.027) |

| Gansu | 27 | 0.032 (0.019–0.044) |

| Qinghai | 13 | 0.045 (0.014–0.076) |

| Ningxia | 9 | 0.068 (0.033–0.105) |

| Xinjiang | 42 | 0.023 (0.012–0.034) |

| Total | 1665 | 0.054 (0.052–0.057) |

CI confidence interval.

Fig. 1.

Incidence of ADEM in all age groups in China. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Ninety-five patients died during 2016–2018, 75 of whom were adults. The hospital mortality rate for ADEM patients in the study period was 1.7%. The annual mortality rate decreased from 3.0% to 0.8% in children and from 5.2% to 3.4% in adults. In children, lung infection (65%), electrolyte disorders (65%), and cerebral edema (65%) were the three most frequent causes of death in ADEM, while in adults, acute respiratory failure (44.0%) and hypoproteinemia (34.7%) followed lung infection (61.3%) and electrolyte disorders (48.0%). From 2016 to 2018, the average cost of each hospitalization slightly increased from US $3483 (IQR 1737–8095) in 2016 to $3724 (IQR 1915–8558) for adults (Table 2). For children, the average cost of each hospitalization was stable: US $2858 (IQR 1306–4785) in 2016 and US $2870 (IQR 1350–5027) in 2018. The average length of stay modestly increased from 19.9 ± 18.6 days in 2016 to 21.3 ± 19.5 days in 2018 in adults, and a similar trend was found in children, with a slight elevation from 15.7 ±12.9 days in 2016 to 16.6 ± 15.9 days in 2018. On average, the burden of hospitalization was relatively heavier in adults than in children. In terms of medical payment methods, patients with Urban Resident Basic Medical Insurance or New Rural Cooperative Medical Insurance accounted for the highest proportion of total ADEM hospitalizations, about 55.0% in children and 62.3% in adults.

Table 2.

Summary of hospitalization and in-hospital deaths.

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child | Adult | Child | Adult | Child | Adult | |

| Summary of hospitalization | ||||||

| Hospitalization, no. (%) | 365 (35.6) | 659 (64.4) | 435 (41.8) | 605(58.2) | 471 (45.4) | 566 (54.6) |

| Hospitalization cost, median (IQR), USD |

2858 (1306–4785) |

3483 (1737–8095) |

2876 (1392–4671) |

3588 (1828–8792) |

2870 (1350–5027) |

3724 (1915–8558) |

| Length of hospital stay, mean (SD), days | 15.7 (12.9) | 19.9 (18.6) | 15.9 (13.1) | 21.1 (18.5) | 16.6 (15.9) | 21.3 (19.5) |

| Medical payment method, no. (%) | ||||||

| URBMI | 100 (27.4) | 215 (32.6) | 137 (31.5) | 215 (35.5) | 206 (43.7) | 242 (42.8) |

| NRCMI | 86 (23.6) | 205 (31.1) | 90 (20.7) | 153 (25.3) | 85 (18.0) | 111 (19.6) |

| CHI | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.4) |

| Fully self-funded | 85 (23.3) | 152 (23.1) | 111 (25.5) | 141 (23.3) | 111 (23.6) | 124 (21.9) |

| Other | 92 (25.3) | 85 (12.9) | 95 (21.8) | 96 (15.9) | 68 (14.5) | 87 (15.4) |

| In-hospital deaths | ||||||

| Number of deaths, no. (%) | 13(24.4) | 32(75.6) | 4(14.8) | 23(85.2) | 3(17.4) | 20(82.6) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 4.6 (3.8) | 53.0 (21.4) | 6.7 (5.0) | 53.4 (17.0) | 7.0 (2.8) | 40.5 (8.7) |

| Male, no. (%) | 6 (46.2) | 18 (56.3) | 3 (75) | 17 (73.9) | 2 (66.7) | 12 (60) |

| Cause, no. (%) | ||||||

| Lung infection | 6 (46.2) | 20 (62.5) | 4 (100) | 13 (56.5) | 3 (100) | 13 (65) |

| Acute respiratory failure | 5 (38.5) | 15 (46.8) | 0 (0) | 10 (58.8) | 0 (0) | 8 (40) |

| Electrolyte disorder | 8 (61.5) | 21(65.6) | 2 (50) | 20 (87) | 3 (100) | 7 (35) |

| Hypoproteinemia | 1 (7.7) | 10 (31.3) | 1 (25) | 8 (34.8) | 1 (33.3) | 8 (40) |

| Cerebral edema | 6 (46.2) | 5 (15.7) | 4 (100) | 5 (21.7) | 3 (100) | 4 (20) |

Child, age <15 years; adult, age ≥15 years; URBMI Urban Resident Basic Medical Insurance, NRCMI New Rural Cooperative Medical Insurance, CHI Commercial Health Insurance, IQR Inter-quartile range, SD standard deviation.

Given its complete coverage and emphasis on diagnoses, HQMS serves as a unique and unparalleled resource for analyzing the incidence of relatively rare diseases such as ADEM. This study is the first nationwide survey of ADEM incidence, covering the entire population of mainland China. The overall incidence is 0.054 per 100,000 population; 0.134 in children and 0.038 in adults. The nationwide incidence of ADEM in children in our study was higher than that in Germany (0.07/100,000) [4] and comparable with those in Iceland (0.131 per 100,000 children) [8] and Canada (0.2) [5], but was lower than those in Japan (0.4) [6] and the USA (0.5–0.6) [9]. We noted that the incidence of ADEM was < 0.32 in Jiangsu Province [10] and 0.31 in Nanchang City [11]. Adoption of the revised ADEM diagnostic criteria in 2013 [1] and the regional population sample size may have contributed this discrepancy. This variation resulted partly from differences in the definitions used to screen incident cases, size of population, and the study methodology. The median age of ADEM onset was 5–9 years with male predominance, corroborating previous reports [4]. Although ADEM predominantly occurred in children, we note that 78.9% of the ADEM patients who died were adults, suggesting that ADEM has a more severe outcome in adults than in children [4]. Steady mortality reduction is evident throughout 2016-2018, and this decline may be attributed to improvements in patient management and the use of intensive care facilities for the care of ADEM patients, especially those with severe onset. This also accounts for the slightly increasing burden of hospitalization. We noted a worse disease course in adults with multiple systems organ failure. They suffered more from acute respiratory failure (6.6-fold) and hypoproteinemia (7.8-fold), presenting a higher mortality rate (3.75-fold) than in children [12].

A limitation of our study is that MRI and laboratory findings (such as AQP4-Ab and MOG-Ab) were not collected into the HQMS database. However, in HQMS, the diagnoses in each qualified “Medical Record Homepage” were reviewed by three doctors (Doctor-in-charge, Co-chief doctor, and Chief director) and checked by the Quality Assurance Physician. This reduces misdiagnoses of other acute demyelinating syndromes. Second, the drug selection and outcome of the treatment of ADEM patients were not collected. Evaluating the efficacy of drugs was not the purpose of our study, and this requires well-designed prospective studies. In conclusion, Our study provides the incidence and mortality of ADEM for the first time across all age groups in mainland China. Thus, our study fills a gap in the epidemiological data on ADEM in China and enriches the global map of ADEM incidence.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation of China (91949208, 91642205, and 81830038) and the Advanced Innovation Center for Human Brain Protection, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China. We thank the National Center for Quality Control of Neurological Diseases for providing technical and logistic support. We are grateful to Dr. De-Cai Tian for helpful comments.

Conflict of interest

The authors claim that there are no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Yuwen Xiu and Hongqiu Gu have contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Krupp LB, Tardieu M, Amato MP, Banwell B, Chitnis T, Dale RC, et al. International Pediatric Multiple Sclerosis Study Group criteria for pediatric multiple sclerosis and immune-mediated central nervous system demyelinating disorders: revisions to the 2007 definitions. Mult Scler. 2013;19:1261–1267. doi: 10.1177/1352458513484547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pohl D, Alper G, Van Haren K, Kornberg AJ, Lucchinetti CF, Tenembaum S, et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: Updates on an inflammatory CNS syndrome. Neurology. 2016;87:S38–S45. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boesen MS, Magyari M, Koch-Henriksen N, Thygesen LC, Born AP, Uldall PV, et al. Pediatric-onset multiple sclerosis and other acquired demyelinating syndromes of the central nervous system in Denmark during 1977–2015: a nationwide population-based incidence study. Mult Scler. 2018;24:1077–1086. doi: 10.1177/1352458517713669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pohl D, Hennemuth I, von Kries R, Hanefeld F. Paediatric multiple sclerosis and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in Germany: results of a nationwide survey. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166:405–412. doi: 10.1007/s00431-006-0249-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banwell B, Kennedy J, Sadovnick D, Arnold DL, Magalhaes S, Wambera K, et al. Incidence of acquired demyelination of the CNS in Canadian children. Neurology. 2009;72:232–239. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000339482.84392.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamaguchi Y, Torisu H, Kira R, Ishizaki Y, Sakai Y, Sanefuji M, et al. A nationwide survey of pediatric acquired demyelinating syndromes in Japan. Neurology. 2016;87:2006–2015. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu L, Xiong W, Yang X, Ma X, Wang C, Yan B, et al. In-hospital mortality of status epilepticus in China: results from a nationwide survey. Seizure. 2020;75:96–100. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2019.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gudbjornsson BT, Haraldsson A, Einarsdottir H, Thorarensen O. Nationwide incidence of acquired central nervous system demyelination in icelandic children. Pediatr Neurol. 2015;53:503–507. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2015.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhatt P, Bray L, Raju S, Dapaah-Siakwan F, Patel A, Chaudhari R, et al. Temporal trends of pediatric hospitalizations with acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in the united states: an analysis from 2006 to 2014 using national inpatient sample. J Pediatr. 2019;206(26–32):e21. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Y, Ma F, Xu Y, Chu X, Zhang J. Incidence of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in the Jiangsu province of China, 2008–2011. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2015;1:2055217315594831. doi: 10.1177/2055217315594831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiong CH, Yan Y, Liao Z, Peng SH, Wen HR, Zhang YX, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in Nanchang, China: a retrospective study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:111. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwarz S, Mohr A, Knauth M, Wildemann B, Storch-Hagenlocher B. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: a follow-up study of 40 adult patients. Neurology. 2001;56:1313–1318. doi: 10.1212/WNL.56.10.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.