Vaccinations are a crucial tool in controlling the current pandemic. In view of this it is all the more remarkable that, in the fourth quarter of 2020, the willingness of the population to be vaccinated against COVID-19 varied between 55%–71% (representative telephone surveys) and 48%–57% (online surveys) (1). The psychological factors that have a positive influence on vaccine uptake include trust in vaccination, whereas weighing up risks and benefits (“calculation”; “weighing up” in the following article) has a negative effect (2). Earlier representative studies of the German Federal Centre for Health Education (BZgA) have found a more favorable attitude towards vaccination in persons with a higher school-leaving qualification (www.bzga.de/forschung/studien/abgeschlossene-studien/studien-ab-1997/impfen-und-hygiene/). As education level is a key parameter for designing vaccination campaigns (2), we will analyze the role of education level in attitudes to vaccination and their association with the factors “trust” and “weighing up.”

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Birte Twisselmann, PhD.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

Method

In 2012, 2014, 2016, and 2018, the BZgA conducted representative telephone surveys on infection prevention and control in the general population in Germany (4483, 4491, 5012, and 5054 participants; age 16–85 years). All used a dual frame design with multistage random sampling in order to include persons who were reachable exclusively by mobile telephone (www.bzga.de/forschung/studien/abgeschlossene-studien/studien-ab-1997/impfen-und-hygiene/). We used binary logistic multiple regression models to analyze the data sets that were open access in January 2021 (2012–2016; https://www.gesis.org/en/services/finding-and-accessing-data/data-archive-service, search term “infection prevention”, category “research data”) to study associations between “attitude to vaccination” on the one hand, and “trust” and “weighing up” on the other. The models were adjusted for “education level” and “sex/gender,” “age,” “children younger than 16 years in household,” “migration background,” “occupational status,” and “medical occupation,” so as to consider confounding by additional sociodemographic factors. The interaction term attitude to vaccination*education level was integrated, and the analyses were additionally stratified by education level.

Results

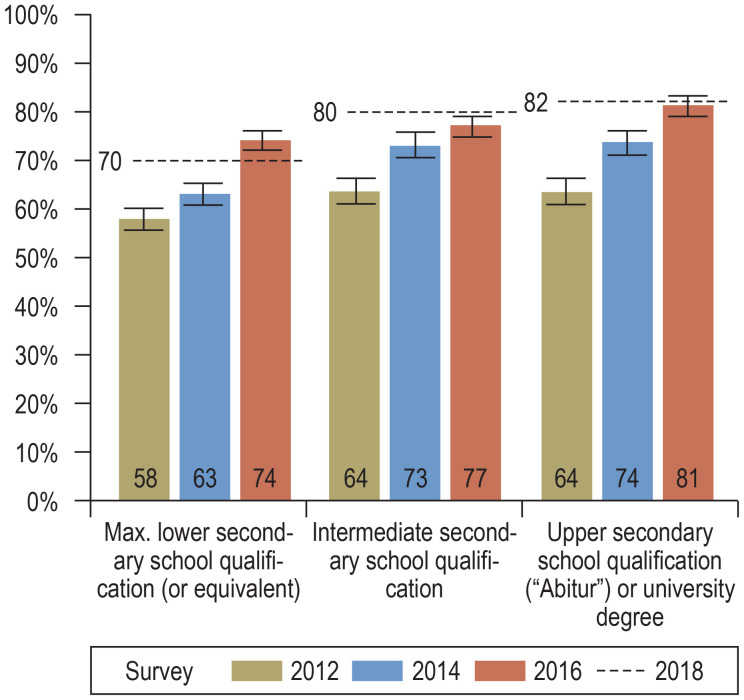

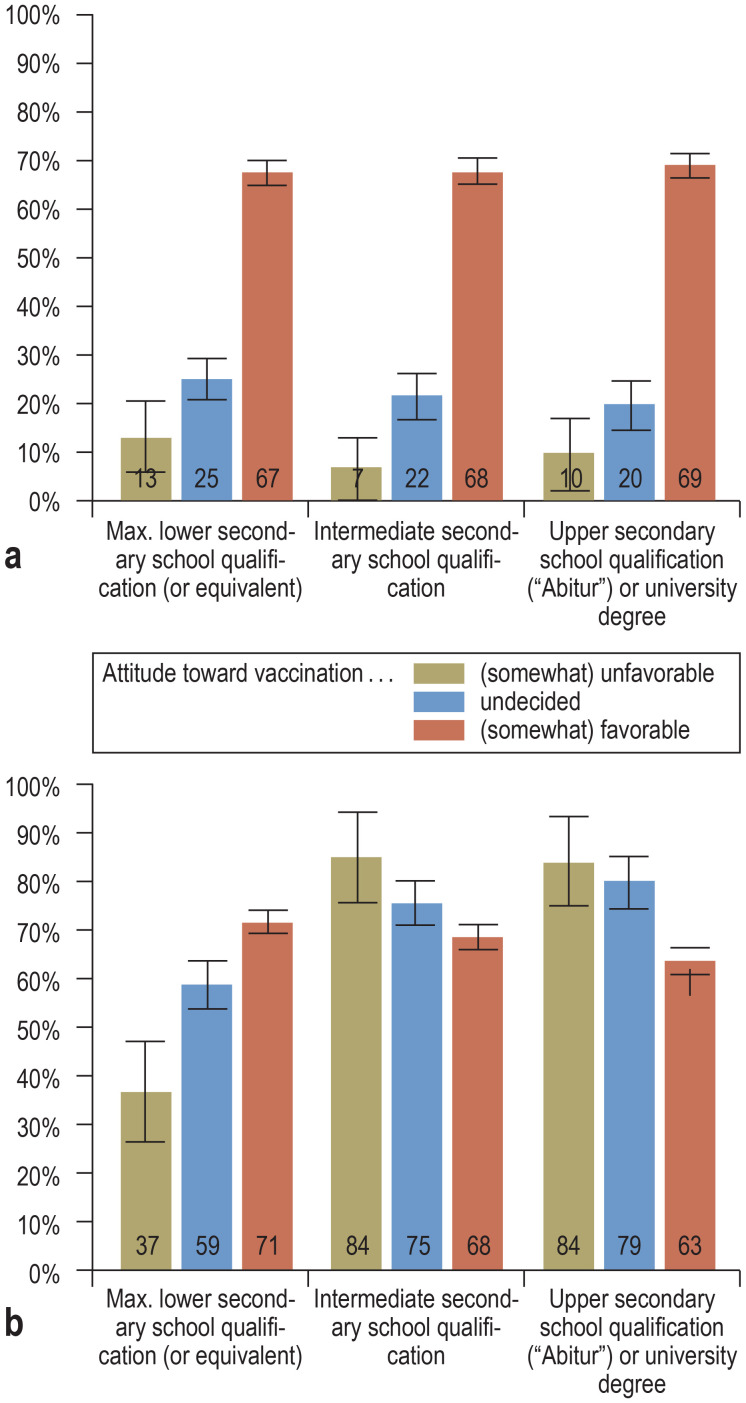

Since 2012 the proportion of persons with a (somewhat) favorable attitude toward vaccination has increased in all groups, stratified by education level. Only since 2018 has it dropped in persons whose highest school leaving qualification was maximally a lower secondary school certificate (or equivalent) (figure 1). Figure 2 shows the rates of agreement with (a) “trust” and (b) “weighing up” in the 2016 survey (not assessed in 2012 and 2014) by education level and attitude to vaccination. The overall existing association between favorable attitude to vaccination and trust in vaccination was found in all groups, regardless of their education level (interaction: Wald = 8.8, p = 0.065). A different pattern emerged for the association between attitude to vaccination and “weighing up”, which was moderated by education level (significant interaction: Wald = 95.7, p <0.001). In the group with a lower secondary school leaving certificate, persons with a favorable or undecided attitude to vaccination were more likely to weigh up than persons who disapproved of vaccinations (ORs = 4.78 and 2.79, 95% confidence interval [2.9; 7.8 and 1.7; 4.7]). In those with a higher education level, an inverse pattern was observed: Persons with a favorable attitude towards vaccination reported weighing up benefits and risks less often than persons objecting to vaccinations (intermediate secondary school leaving certificate: OR = 0.34, [0.2; 0.8; upper secondary school [”Abitur”] or university degree: 0.35, [0.2; 0.7]).

Figure 1.

How would you describe your attitude towards vaccination in general? (Somewhat) Favorable.

(Somewhat) Favorable attitude to vaccination in general in the general population in Germany by education status: trends since 2012

Proportions of (somewhat) favorable responses (in % with 95% confidence intervals); Data: (Source: see Methods section)

Figure 2.

Two determinants of vaccination related behavior—in the general population in Germany in 2016, by education status and attitudes toward vaccination

a) Trust: I have complete trust in the safety of vaccinations.

b) Weighing up: If I consider getting vaccination or not, I carefully weigh up risks and benefits.

Proportion of responses agreeing with the respective item (in % with 95% confidence intervals); Data: (source see Methods section)

Discussion

The analyses show that, up to 2018, rates of positive attitudes towards vaccination in general increased in all groups, whatever their education level. Furthermore, the association of such attitudes with the vaccination determinants “trust” and “weighing up” varied by education level. “Trust” was consistent with the attitude valence in all status groups. The situation is more complex for “weighing up.” In survey participants with a lower secondary school qualification, weighing up was accompanied by a positive attitude towards vaccination, whereas in persons with a higher level certificate it was more likely to be associated with a negative attitude towards vaccination. One reason for this interaction might be that people with a higher education level seek out information more intensely, which increases the probability that they find risk information (including from questionable, not scientifically based sources). It remains to be determined whether this pattern of frequent weighing up in higher education level and negative attitude towards vaccination also exists in the 2018 survey, especially as the proportion of those weighing up while having a negative attitude towards vaccination was higher (72% vs 56% in 2016). The generalizability to the COVID-19 situation requires further research. A study from the United Kingdom showed that the general attitude towards vaccination had an indirect effect on the intention to have the COVID-19 vaccine ([3] and Julius Sim, personal communication, 30 January 2021). Since the latter was also strongly influenced by the uptake of the influenza vaccination before the COVID-19 pandemic (3), habituated vaccination behavior is likely.

The results of our analyses therefore suggest employing target-group adjusted communication strategies for SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations. Especially as its long-term risks are still uncertain, target groups with a higher education level might benefit in particular—in addition to the emphasis on social norms and pro-vaccination models (4)—from evidence-based information about risks and benefits (e.g., fact boxes) (4). This would not only meet the need for informed decisions, which is particularly pronounced in this group, but may also increase trust thanks to the transparency of the communication (4, 5).

Conclusion

In sum, it should be emphasized that transparent communication of benefits and risks should be provided independent of recipients’ education level, especially as no evidence exists that the preference for the communication of uncertainty regarding COVID-19 depends on education level (5). At the same time, such communication is a challenge in persons with a higher education level and a negative attitude toward vaccination, and instruments to support weighing up (e.g., fact boxes [4]) may be effective.

References

- 1.Haug S, Schnell R, Weber K. [Willingness to be vaccinated with a COVID-19 vaccine and influencing factors Results of a CATI population survey]. ResearchGate 348593189. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.23811.53283. doi: 10.1055/a-1538-6069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Betsch C, Schmid P, Korn L, et al. [Psychological antecedents of vaccination: definitions, measurement, and interventions] Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2019;62:400–409. doi: 10.1007/s00103-019-02900-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sherman SM, Smith LE, Sim J, et al. COVID-19 vaccination intention in the UK: results from the COVID-19 vaccination acceptability study (CoVAccS), a nationally representative cross-sectional survey. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2020:1–10. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1846397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Helmer SM, Pischke CR, Wegwarth O, et al. Wissenschaftsbasierte Öffentlichkeitskommunikation und -information im Rahmen einer nationalen COVID19-Impfstrategie: Empfehlungen in Anlehnung an internationale wissenschaftliche Erkenntnisse Bremen: Kompetenznetz Public Health COVID-19 2021. https://www.public-health-covid19.de/images/2021/Ergebnisse/Helmer_et_al_Kommunikation_Impfung_28012021_final_Haarter_Update_3_Januar28_2021.pdf (last accessed on 29 January 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wegwarth O, Wagner GG, Spies C, Hertwig R. Assessment of German public attitudes toward health communications with varying degrees of scientific uncertainty regarding COVID-19. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.32335. e2032335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]